Abstract

Injury induces the recruitment of bone marrow-derived cells (BMDCs) that contribute to the repair and regeneration process. The behavior of BMDCs in injured tissue has a profound effect on repair, but the regulation of BMDC behavior is poorly understood. Aberrant recruitment/retention of these cells in wounds of diabetic patients and animal models is associated with chronic inflammation and impaired healing. BMD Gr-1+CD11b+ cells function as immune suppressor cells and contribute significantly to tumor-induced neovascularization. Here we report that Gr-1+CD11b+ cells also contribute to injury-induced neovascularization, but show altered recruitment/retention kinetics in the diabetic environment. Moreover, diabetic-derived Gr-1+CD11b+ cells fail to stimulate neovascularization in vivo and have aberrant proliferative, chemotaxis, adhesion, and differentiation potential. Previously we demonstrated that gene transfer of HOXA3 to wounds of diabetic mice is taken up by and expressed by recruited BMDCs. This is associated with a suppressed inflammatory response, enhanced neovascularization, and accelerated wound healing. Here we show that sustained expression of Hoxa3 in diabetic-derived BMD Gr-1+CD11b+ cells reverses their diabetic phenotype. These findings demonstrate that manipulation of adult stem/progenitor cells ex vivo could be used as a potential therapy in patients with impaired wound healing.

Introduction

Bone marrow contains a pool of stem cells that reconstitute the hematopoietic system throughout the life of the organism. Bone marrow-derived cells (BMDCs) also migrate to and participate in homeostasis of tissues such as muscle, intestines, and skin (reviewed in1,2 ). During tumorigenesis this process is accelerated, and BMDCs have been shown to significantly promote angiogenesis and tumor metastases.1-5 Similarly, after cutaneous injury, a heterogeneous population of BMDCs are recruited to the site of injury and contribute directly to the repair process by differentiating into skin cell types, such as fibroblasts, keratinocytes, and endothelial cells.4-6 They can also indirectly modulate repair and regeneration by producing cytokines and growth factors that promote re-epithelialization, neovascularization, and wound closure at the site of injury (reviewed in7 ). However, it has become clear that BMDCs do not always play a positive role in wound healing. In patients and animal models with diabetes, BMDCs contribute to an impaired healing/chronic wound environment by prolonging the inflammatory response and/or failing to promote the regenerative phase of wound healing.8-10

Gr-1+CD11b+ cells are a subset of BMD myeloid cells that are recruited to tumors in vivo and can function as immune suppressor cells with proangiogenic capacity in the tumor microenvironment.11-16 They consist of a heterogeneous population containing monocytic and granulocytic myeloid progenitors and committed cells.15 Therefore, we wanted to know whether these cells are similarly recruited to wounds and contribute to injury-induced neovascularization. We also wanted to test whether the diabetic environment has any effect on their behavior, and if so, whether this could be reversed by transcription factor reprogramming.

How cell-intrinsic factors control the differentiation of BMD stem/progenitor cells recruited to peripheral tissues in response to injury is poorly understood, although Hox transcription factors have been shown to extensively modulate BMDCs. HOXA7 and HOXB3 are up-regulated during the differentiation of human BMD mesenchymal stem cells into endothelial cells, while HOXA3 and HOXB13 are down-regulated during differentiation.17 In murine mesenchymal stem cells, Hoxb2, Hoxb5, Hoxb7, and Hoxc4 have been reported to regulate self-renewal.18 Hox genes also regulate self-renewal/differentiation of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs). During hematopoiesis, cells in distinct stages of differentiation have specific Hox gene expression profiles, and overexpression of Hox genes, such as Hoxb4, can reprogram cells to maintain a stem/progenitor state. Prolonged expression of some Hox genes such as Hoxa10, Hoxb3, and Hoxb6 is associated with myeloproliferative disorders and leukemias (reviewed in19 ).

We have previously shown that sustained expression of HOXA3 in vivo can modulate BMD cell behavior in the wound microenvironment by changing the balance of endothelial progenitor and inflammatory cell recruitment/retention.10 This is associated with dramatically improved angiogenesis and accelerated wound closure in diabetic wounds.20 Here we show for the first time that Gr-1+CD11b+ cells are recruited to injured tissue, but that their recruitment/retention kinetics are aberrant in the diabetic environment. Gr-1+CD11b+ cells from the nondiabetic environment significantly increase the number of cluster of differentiation (CD)34+ microvessels when transplanted to diabetic wounds, but equivalent cells isolated from the diabetic environment do not. Diabetic-derived Gr-1+CD11b+ myeloid cells display aberrant proliferation, differentiation, chemotaxis, and adhesion potential compared with nondiabetic-derived Gr-1+CD11b+ cells. Transcription factor reprogramming of hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells (HSC/Ps), using proangiogenic Hoxa3, induces their proliferation and differentiation into granulocytic Gr-1+CD11b+ cells. In addition, Hoxa3 overexpression in Gr-1+CD11b+ cells isolated from the diabetic environment can reverse the defects induced by the diabetic environment, suggesting that these cells can be reprogrammed toward a more proangiogenic fate.

Methods

Animals

Animals used in this study were housed at the University of Manchester animal care facility. All procedures were approved by the University of Manchester ethical review committee and the Home Office. 129S2/SvHsd mice were purchased from Harlan, and the diabetic mouse model B6.Cg-m +/+ Leprdb/J (stock #000697) and their nondiabetic controls were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory.

Wounding model

Mice (female) were 8-12 weeks of age at the time of wounding. Diabetic and nondiabetic littermate controls of the B6.Cg-m +/+ Leprdb/J were anesthetized and the dorsum shaved and sterilized with antiseptic wipes. A 6-mm–diameter full-thickness wound was excised including the panniculus carnosus layer. Animals received buprenorphine at the time of surgery and were housed in separate cages until tissue was harvested at the described time points by removing the entire wound area, including a 2-mm perimeter.

Flow cytometry

BMDCs were obtained from the femora and tibiae. Cardiac puncture under anesthesia was used to collect blood from mice for further analyses. Red blood cells were lysed with ACK lysis buffer. Samples were washed (phosphate-buffered saline [PBS] plus 5% fetal bovine serum [FBS]), and antibody staining was performed following the manufacturer's recommended dilutions using the following antibodies: fluorescein isothiocyanate-anti–Sca-1 (ab25031; Abcam), PE-Cy5-anti–c-Kit (ab25495; Abcam), PE-Cy7-anti–Gr-1 (552985; BD Biosciences), Alexa 647–anti-CD11b (557686; BD Biosciences), and PE–anti-CD34 (12-0341; eBioscience). Samples were analyzed or sorted using flow cytometry (BD FACSAria; BD Biosciences). Skin or wound tissue dispersion was performed essentially as described by Wilson et al21 with modifications. In brief, freshly harvested skin or wound tissue was weighed and cut into 2-mm pieces followed by overnight incubation at 4°C in 5 mL/g Hank buffered salt solution containing 1 mg/mL dispase I (Sigma-Aldrich), 3% FBS, and 10 mg/mL G418 (Sigma-Aldrich). Tissue was then transferred to Hank buffered salt solution (20 mL/g tissue) containing 1 mg/mL collagenase D (Roche), 150 U/mL DNase I (QIAGEN), and 5 mg/mL G418 for 2 hours at 37°C in a shaking incubator. After 2 hours, the cell suspensions from both steps were mixed and passed through a 70-μm cell strainer (BD Biosciences), centrifuged, and washed 3 times with PBS plus 5% FBS, then resuspended in PBS plus 5% FBS for antibody staining.

Administration of Gr-1+CD11b+ cells

Three diabetic and 3 nondiabetic groups were used (6 animals/group). Gr-1+CD11b+ cells were isolated using fluorescence-activated cell sorting from bone marrow of diabetic and nondiabetic animals. Two days after wounding, 2.5 × 105 freshly isolated cells in 50 μL PBS were injected under each wound of the experimental groups. Controls received 50 μL PBS. Wounds were harvested at day 7 (following wounding). Half of the wound was formalin-fixed, embedded in paraffin, and analyzed for new microvessels in the granulation tissue using anti-CD34 immunohistochemistry (described below). The other half was enzymatically digested (as described above in the Flow Cytometry section), and the single-cell suspension was labeled with PE–anti-CD34 (eBiosciences) and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Immunohistochemistry

Tissue samples were fixed in zinc formalin for 24 to 48 hours and embedded in paraffin. Serial 5-μm sections were obtained (rotary microtome HM355s; Rankin Biomedical), and hematoxylin and eosin staining was performed using Thermo Shandon Varistain 24-4. Paraffin sections were cleared, dehydrated, and rehydrated. Antigen retrieval was performed by microwaving slides for 20 minutes in sodium citrate buffer. Rabbit anti-GFP (Abcam) was used (1/1000) to detect GFP+Gr-1+CD11b+ cells. Anti-murine CD34 (SC-7045; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was used (1/200) for staining the microvessels. Blocking and antibody detection was performed using the Vectastain ABC kit (Vector Labs) according to manufacturer's instructions. CD34+ vessel lumens in granulation tissue were counted for each animal using 400× magnification.

Migration assays

Transwell migration assays were performed using collagen I inserts (BD Biosciences) with 3-μm pore-sized membranes. Transfection of Hoxa3-mCherry or mCherry in Gr-1+CD11b+ cells was performed using the Amaxa Nucleofector-I device (Amaxa) and mouse macrophage nucleofector kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. Gr-1+CD11b+ cells were serum-starved for 4 hours before the experiment. Inserts were rehydrated using RPMI medium without serum for 30 minutes, then placed into the wells of companion plates containing 500 μL RPMI supplemented with 50 ng/mL recombinant human vascular endothelial growth factor (rhVEGF; Invitrogen), 10 ng/mL macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)–2 (R&D Systems), or 10 ng/mL monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP)–1 (R&D Systems). The upper well was filled with 104 cells in 500 μL RPMI without serum and incubated 4 hours at 37°C. Membranes were fixed and stained with Giemsa (Sigma-Aldrich) and microscopically analyzed. Cell migration was measured by counting cells that had migrated through the membrane. Experiments were performed in 3 biological and 3 experimental replicates.

Adhesion assays

Mouse hemangioendothelioma endothelial cells (EOMAs; LGC Standards) were cultured in 24-well plates 48 hours before each assay and pretreated for 12 hours with Dulbecco modified Eagle medium containing 1 ng/mL tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α). Diabetic or nondiabetic-derived Gr-1+CD11b+ cells (untransfected or transfected with Hoxa3-mCherry or mCherry control) from 3 biological replicates were stained with PKH26 lipophilic dye (Sigma-Aldrich), cocultured with endothelial cells in triplicate (103/well), and incubated for 3 hours at 37°C. Each well was then gently washed 3 times with PBS to remove nonadherent cells. The attached Gr-1+CD11b+ cells labeled with PKH26 were counted using fluorescent microscopy (at 200× using an inverted Olympus IX70 and Sony DXC-950p power HAD 3CCD color video camera at room temperature).

Gene expression analyses

Quantitative analyses of gene expression profiles of macrophage polarization (M1 and M2 markers), angiogenic factors, Hoxa3, and a representative Hoxa3 target gene Cdc42, in diabetic and nondiabetic-derived Gr-1+CD11b+ cells were performed using TaqMan gene expression assays (Applied Biosystems): interferon gamma (Ifng), Mm01168134_m1; interleukin 6 (Il-6), Mm00446191_m1; tumor necrosis factor α (Tnf-α), Mm00443258_m1; arginase-1 (Arg-1), Mm00475988_m1; interleukin 10 (Il-10), Mm00439614_m1; transforming growth factor β-1 (Tgfβ), Mm01178820__m1; vascular endothelial growth factor A (Vegf), Mm00437304_m1; matrix metalloproteinase 9 (Mmp-9), Mm00442991_m1; prokineticin 2 (Bv-8), Mm00450080_m1; homeobox A3 (Hoxa3), Mm01326402_m1; and cell division cycle 42 (Cdc42), Mm01194005_g1. Histone 2A, Mm00501974_s1, and Hsp90ab1, Mm00833431_g1, were used as reference genes.

Construction of the Hoxa3-mCherry and mCherry expression plasmids

The Hoxa3 open reading frame was polymerase chain reaction (PCR)–amplified from a full-length cDNA clone (Geneservice), and fused to mCherry (Clontech) via PCR using the following primers: Hoxa3-5′, AAC-ATC-GCG-ATG-CAA-AAA-GCG-A, Hoxa3/mCherry fusion-3′, GCT-CAC-CAG-GTG-GGT-GAG, Hoxa3/mCherry fusion-5′, CAC-CTG-GTG-AGC-AAG-GGC, mCherry-3′, TTA-CTT-GTA-CAG-CTC-GTC-CAT-G. The mCherry open reading frame was amplified with the following primers: mCherry-5′, GTC-GCC-ACC-ATG-GTG-AGC-A, and mCherry-3′, TTA-CTT-GTA-CAG-CTC-GTC-CAT-G. Both PCR products (Hoxa3-mCherry or mCherry alone) were cloned into the pCRII-TOPO vector (Invitrogen) and then subcloned into the BamHI/XhoI restriction sites in-frame with the immunoglobulin κ-chain leader sequence signal peptide (SP) in the pSecTag2 vector (Invitrogen) or pcDNA3.1 (Invitrogen). All constructs were sequence-verified by the University of Manchester sequencing facility.

Feeder layer cells, culture conditions, and transfections

Immortalized murine fetal liver stromal cells AFT024 (LGC Standards) were used as a feeder layer to maintain HSCs in culture.22-24 Cells were grown in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with 0.05mM 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich), 10% FBS (Lonza), 1.5 g/L sodium pyruvate (Lonza), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 0.1 mg/mL streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich) at 33°C. At 50% confluency, cells were transfected with SP-Hoxa3-mCherry or SP-mCherry alone (FuGENE HD; Roche). Gene expression was monitored via observation of mCherry fluorescent protein expression. Before coculture, confluent AFT024 cells were transferred to 37°C to inactivate the temperature-sensitive simian virus 40 T antigen and treated with mitomycin C (Sigma-Aldrich) to arrest cell division.

HSC/Ps and long-term coculture conditions

Bone marrow from the femora and tibiae of 3 129S2/SvHsd male mice was pooled and enriched for HSC/Ps using an antibody cocktail and magnetic depletion system according to the manufacturer's instructions (StemSep; Stem Cell Technologies). After enrichment, HSC/Ps were cocultured in triplicate with feeder layer cells expressing SP-Hoxa3-mCherry or SP-mCherry in Iscove modified Dulbecco medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 30% FBS (Invitrogen), 100μM 2-mercaptoethanol, 1μM hydrocortisone, 50 U/mL penicillin/streptomycin, 2mM l-glutamine (Lonza), 10 ng/mL IL-3, 50 U/mL IL-6, and 50 ng/mL stem cell factor (R&D Systems).25,26 Transfection of feeder layer cells with SP-Hoxa3-mCherry or SP-mCherry control plasmid results in secretion of the protein products encoded by these genes. Hoxa3-mCherry in the media enters HSC/Ps via passive translocation (as previously described in27 ). Long-term coculture was conducted for 4 weeks. Each week a subsample of the cells was harvested for further analysis.

Detection of Hoxa3-mCherry in hematopoietic cells

AFT024 cells were transfected with the indicated constructs and examined weekly using fluorescent microscopy (Inverted, Olympus IX70 and Sony DXC-950p power HAD 3CCD color video camera) for mCherry protein expression. A subsample of hematopoietic cells was purified from coculture with AFT024 each week for 4 weeks. Nuclear and cytoplasmic protein extract was obtained using cell lysis buffer (10mM HEPES [N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid], 10mM KCl, 0.1mM EDTA [ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid], 0.4% NP40) and nuclear extraction buffer (20mM HEPES, 400mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA) plus protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) and 10μM lactacystin (Sigma-Aldrich). Lysates were loaded on a 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gel and transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (Millipore). Rabbit anti-dsRed (Clontech) was used to detect Hoxa3-mCherry or mCherry control protein. In addition, hematopoietic cells were harvested after 7 days of coculture with AFT024 cells secreting SP-mCherry or SP-Hoxa3-mCherry protein and transferred onto Cytospin slides using a Shandon Cytospin device (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Hematopoietic cells were fixed on slides using 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 minutes and stained with anti-dsRed antibody (1/400) to detect Hoxa3-mCherry or mCherry control protein. Staining was visualized using Alexa-555 secondary antibody (1/500) and counterstained with DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) to label nuclei (Olympus FluoView FV 1000 inverted confocal microscope, 60× objective, and FluoView image acquisition software).

Analysis of hematopoietic cells from coculture

Hematopoietic cells were purified from coculture, stained with trypan blue (Sigma-Aldrich), and viable cells counted using a hemocytometer. Colony assays were performed to check the proliferation and differentiation potential of hematopoietic cells each week. Cells were cultured in methylcellulose containing cytokines according to the manufacturer's instructions (MethoCult; StemCell Technologies). After 12 days, the number and types of colonies were counted. In addition, quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) was used to analyze expression of hematopoietic lineage markers using TaqMan assays (Applied Biosystems): Itgam/CD11b, Mm00434455_m1; Ly-6g/Gr-1: custom assay; CD19, Mm00515420_m1; and CD5, Mm00432417_m1. Histone 2A, Mm00501974_s1, and Hsp90ab1, Mm00833431_g1, were used as reference genes.

Statistical analysis

All results are presented as mean ± SEM. After verifying that the data to be analyzed showed a normal distribution, a Student t test or 2-way analysis of variance and post hoc t tests were used to assess differences, with probability values of P ≤ .05 denoting statistical significance unless otherwise noted. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 5 or Microsoft Excel 11.2.

Results

The role of Gr-1+CD11b+ cells in injury-induced neovascularization

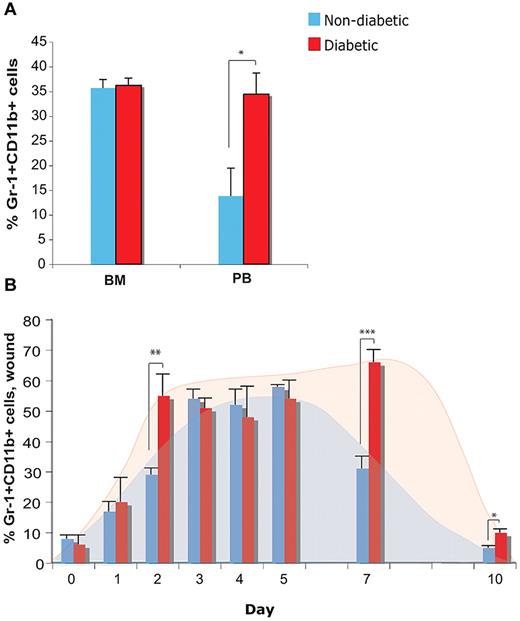

Because Gr-1+CD11b+ cells have been demonstrated to play a key role in tumor-induced neovascularization, we hypothesized Gr-1+CD11b+ cells may contribute to injury-induced neovascularization. We also hypothesized that the diabetic environment may impair recruitment, retention, or function of Gr-1+CD11b+ cells, as diabetic patients and animal models display impaired neovascularization. To this end, we used the Leptin receptor deficient mouse (db/db) model of diabetes mellitus type 2, which displays severely impaired wound healing and neovascularization.8,28,29 We first analyzed the Gr-1+CD11b+ cell population in the bone marrow and blood of nondiabetic (db/+) and diabetic (db/db) animals using flow cytometry. Although there is no difference in the percentage of Gr1+CD11b+ cells in the bone marrow between nondiabetic and diabetic animals, diabetic animals have significantly more Gr-1+CD11b+ cells in circulation (Figure 1A). We then analyzed the percentage of Gr-1+CD11b+ cells in wounds of nondiabetic and diabetic animals each day before and following injury for 7 days, as well as day 10. Although there is no difference in the percentage of Gr-1+CD11b+ cells present in unwounded skin, there are significantly more Gr-1+CD11b+ cells in wounds of diabetic mice at early and late time points, compared with nondiabetic mice, while percentages are similar at middle time points (Figure 1B). These results indicate that the diabetic wound environment results in a faster and larger accumulation of these cells, compared with the nondiabetic environment, and contributes to their sustained presence in the wound at day 7, when their numbers are declining in the nondiabetic wound. The similarity in percentages of these cells retained in the wounds of both groups at middle time points reflects an intersection point in the kinetics of the trafficking of these cells. However, these results also raised the question of whether these cells function to promote neovascularization in the diabetic environment during wound repair as they do during tumorigenesis, or whether the diabetic environment impairs their proangiogenic function.

Trafficking of Gr-1+CD11b+ cells in diabetic animals. (A) Quantification of percentage of Gr-1+CD11b+ cells in the bone marrow (BM) and peripheral blood (PB), and (B) in skin before (day 0) and following injury at the indicated time points, in diabetic and nondiabetic mice using flow cytometry. Error bars represent SEM, *P ≤ .05, **P ≤ .01, ***P ≤ .001.

Trafficking of Gr-1+CD11b+ cells in diabetic animals. (A) Quantification of percentage of Gr-1+CD11b+ cells in the bone marrow (BM) and peripheral blood (PB), and (B) in skin before (day 0) and following injury at the indicated time points, in diabetic and nondiabetic mice using flow cytometry. Error bars represent SEM, *P ≤ .05, **P ≤ .01, ***P ≤ .001.

Nondiabetic Gr-1+ CD11b+ cells can promote neovascularization in the diabetic environment

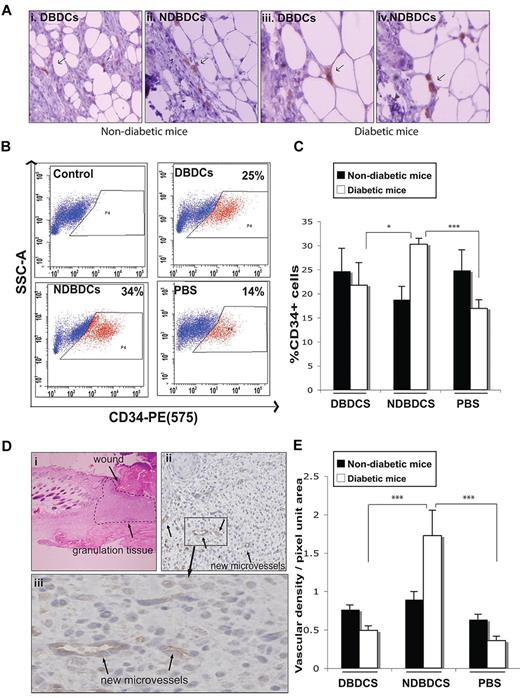

Because we observed more Gr-1+CD11b+ cells in wounds of diabetic mice, which are characterized by impaired neovascularization, we hypothesized that they might have different effects on neovascularization in vivo compared with Gr-1+CD11b+ cells from nondiabetic mice. Therefore, we assayed the effect of adding Gr-1+CD11b+ cells from diabetic versus nondiabetic mice on wound neovascularization in both diabetic and nondiabetic animals. Animals were divided into 4 experimental and 2 control groups (6 animals per group), consisting of nondiabetic and diabetic animals receiving nondiabetic or diabetic-derived Gr-1+CD11b+ cells, or PBS (control groups). Each pair-wise interaction was tested (eg, diabetic mice receiving nondiabetic-derived cells). Cells were injected into wounds at day 2 following wounding, as described in the Methods, and the presence of labeled Gr-1+CD11b+ cells remaining in the wound at day 7 was verified by immunohistochemistry (Figure 2A).

Nondiabetic-derived Gr-1+CD11b+ cells promote injury-induced neovascularization. (A) Detection of GFP+ Gr-1+CD11b+ cells (arrows) 5 days after injection into wounds. (B) Representative plots from flow cytometric analysis of CD34+ cells (red) and CD34− cells (blue) in wounds following injection of Gr-1+CD11b+ cells into wounds. (C) Quantification of flow cytometric analysis data (as in panel B) of CD34+ cells from digested wound tissue from each treatment group at day 7 after wounding. (Di) A representative hematoxylin and eosin staining of 5-μm sections of day 7 wounds showing area used for analysis of neovascularization (granulation tissue). Image shown is original magnification ×40. (ii-iii) Representative images of immunohistochemistry of 5-μm wound sections labeled with anti-CD34 antibody (brown), and counterstained with hematoxylin (blue). Arrows show new microvessels. Images shown are original magnification ×400 (ii) and ×1000 (iii). (E) Quantification of CD34+ microvessels in wound tissue sections as shown in panel D. DBDCs, diabetic-derived Gr-1+CD11b+ cells; NDBDCs, nondiabetic-derived Gr-1+CD11b+ cells; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline. Error bars represent SEM, *P ≤ .05, ***P ≤ .001.

Nondiabetic-derived Gr-1+CD11b+ cells promote injury-induced neovascularization. (A) Detection of GFP+ Gr-1+CD11b+ cells (arrows) 5 days after injection into wounds. (B) Representative plots from flow cytometric analysis of CD34+ cells (red) and CD34− cells (blue) in wounds following injection of Gr-1+CD11b+ cells into wounds. (C) Quantification of flow cytometric analysis data (as in panel B) of CD34+ cells from digested wound tissue from each treatment group at day 7 after wounding. (Di) A representative hematoxylin and eosin staining of 5-μm sections of day 7 wounds showing area used for analysis of neovascularization (granulation tissue). Image shown is original magnification ×40. (ii-iii) Representative images of immunohistochemistry of 5-μm wound sections labeled with anti-CD34 antibody (brown), and counterstained with hematoxylin (blue). Arrows show new microvessels. Images shown are original magnification ×400 (ii) and ×1000 (iii). (E) Quantification of CD34+ microvessels in wound tissue sections as shown in panel D. DBDCs, diabetic-derived Gr-1+CD11b+ cells; NDBDCs, nondiabetic-derived Gr-1+CD11b+ cells; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline. Error bars represent SEM, *P ≤ .05, ***P ≤ .001.

Neovascularization following addition of Gr-1+CD11b+ cells was assessed at day 7 (ie, 5 days after treatment) by 2 methods. CD34 was used as a marker of endothelial progenitor cells and endothelial cells in wound tissue, as opposed to CD31/PECAM-1, as CD31 is also highly expressed by platelets and leukocytes, which are present in large numbers in wounds and would therefore lead to ambiguity between inflammatory cell and endothelial cell detection.30 Flow cytometric analysis of enzymatically digested wound tissue showed a significant increase in the number of CD34+ cells in diabetic wounds treated with nondiabetic Gr-1+CD11b+ cells compared with diabetic wounds treated with diabetic-derived Gr-1+CD11b+ cells or PBS (Figure 2B-C). However, in addition to endothelial cells and endothelial progenitor cells, this marker is also expressed by hair follicle bulge stem/progenitor cells, of which there may be a small fraction (at the wound margins) contributing to this analysis. Therefore we also analyzed CD34+ microvessel density in granulation tissue (Figure 2D-E). Immunohistological analyses confirmed that treatment of diabetic wounds with nondiabetic-derived Gr-1+CD11b+ cells significantly increased the density of CD34+ microvessels in the granulation tissue compared with diabetic wounds treated with diabetic-derived Gr-1+CD11b+ cells or PBS control (Figure 2E). In contrast, diabetic-derived Gr-1+CD11b+ cells had no effect on CD34+ vessel density compared with the PBS-injected control group (Figure 2E). Interestingly, treatment of nondiabetic wounds with Gr-1+CD11b+ cells showed no significant effect on CD34+ vessel density compared with PBS (Figure 2E). This result is reminiscent of our observation that sustained expression of proangiogenic factors, such as HOXA3, improves wound healing only in the diabetic environment.20

Effect of the diabetic environment on Gr-1+CD11b+ cell behavior

Previous investigations of Gr-1+CD11b+ cells have shown that they are a heterogeneous population, most frequently characterized as immature myeloid cells that can differentiate along the granulocytic (granulocytic progenitor cell; CFU-G) or monocytic (monocytic progenitor cell; CFU-M) lineages, as well as more mature myeloid cells, providing immunosuppressive and proangiogenic functions in vivo (recently reviewed in15 ). Because diabetic-derived Gr-1+CD11b+ cells failed to stimulate injury-induced neovascularization, we hypothesized that the diabetic environment was altering the behavior of these cells. We tested this hypothesis by analyzing their potential with respect to proliferation, differentiation, chemotaxis, adhesion, and angiogenesis-related gene expression relative to nondiabetic-derived Gr-1+CD11b+ cells.

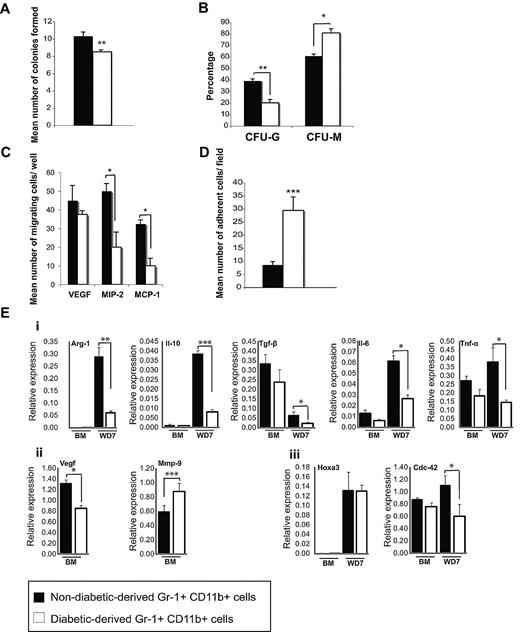

Gr-1+CD11b+ cell proliferation and differentiation

To analyze the proliferation and differentiation potential of Gr-1+CD11b+ cells isolated from diabetic and nondiabetic animals, colony assays were performed. The total colony number of Gr-1+CD11b+ cells from diabetic mice was significantly less than Gr-1+CD11b+ cells from nondiabetic mice (Figure 3A), suggesting these cells have reduced proliferation potential. Furthermore, Gr-1+CD11b+ cells from diabetic animals formed significantly fewer CFU-G and significantly more CFU-M compared with Gr-1+CD11b+ cells from nondiabetic animals (Figure 3B). These results indicate that the diabetic environment affects the lineage commitment of these progenitor cells, inhibiting granulotcytic differentiation while promoting monocytic differentiation.

Functional assays of Gr-1+CD11b+cells from diabetic animals. (A) In vitro colony assays of nondiabetic and diabetic-derived Gr-1+CD11b+ cells indicating the total number of colonies formed (B), the percentage of colonies formed that were granulocytes, G, versus monocytes, M, for each sample. (C) Migration assays of nondiabetic and diabetic-derived Gr-1+CD11b+ cells toward VEGF, MIP-2, and MCP-1. (D) Adhesion assay of nondiabetic and diabetic-derived Gr-1+CD11b+ cells on TNF-α activated endothelial cells. (E) Gene expression profile of Gr-1+CD11b+ cells assessed by qRT-PCR. (i) Expression of M1 and M2 macrophage markers by diabetic and nondiabetic-derived Gr-1+CD11b+ cells. (ii) Expression of angiogenic factors Vegf and Mmp-9 in diabetic and nondiabetic-derived Gr-1+CD11b+ cells. (iii) Expression of endogenous Hoxa3 and a representative Hoxa3 target gene Cdc42 in diabetic and nondiabetic-derived Gr-1+CD11b+ cells. Error bars represent SEM, *P ≤ .05, **P ≤ .01, ***P ≤ .001. BM, bone marrow; WD7, wound day 7.

Functional assays of Gr-1+CD11b+cells from diabetic animals. (A) In vitro colony assays of nondiabetic and diabetic-derived Gr-1+CD11b+ cells indicating the total number of colonies formed (B), the percentage of colonies formed that were granulocytes, G, versus monocytes, M, for each sample. (C) Migration assays of nondiabetic and diabetic-derived Gr-1+CD11b+ cells toward VEGF, MIP-2, and MCP-1. (D) Adhesion assay of nondiabetic and diabetic-derived Gr-1+CD11b+ cells on TNF-α activated endothelial cells. (E) Gene expression profile of Gr-1+CD11b+ cells assessed by qRT-PCR. (i) Expression of M1 and M2 macrophage markers by diabetic and nondiabetic-derived Gr-1+CD11b+ cells. (ii) Expression of angiogenic factors Vegf and Mmp-9 in diabetic and nondiabetic-derived Gr-1+CD11b+ cells. (iii) Expression of endogenous Hoxa3 and a representative Hoxa3 target gene Cdc42 in diabetic and nondiabetic-derived Gr-1+CD11b+ cells. Error bars represent SEM, *P ≤ .05, **P ≤ .01, ***P ≤ .001. BM, bone marrow; WD7, wound day 7.

Gr-1+CD11b+ cell chemotaxis and adhesion

To determine whether the diabetic environment had any effect on Gr-1+CD11b+ cell chemotaxis, their migration toward 3 injury-induced chemoattractants (VEGF, MIP-2, and MCP-1) was analyzed. Gr-1+CD11b+ cells from diabetic mice have significantly reduced migration toward MCP-1 and MIP-2 compared with cells from nondiabetic mice, although their migration toward VEGF is not significantly affected (Figure 3C). We also assessed the adhesion of Gr-1+CD11b+ cells from nondiabetic and diabetic mice onto endothelial cells. Diabetic-derived Gr-1+CD11b+ cells showed significantly increased adhesion onto TNF-α–activated endothelial cells, which mimic wound-resident endothelial cells, compared with nondiabetic-derived Gr-1+CD11b+ cells (Figure 3D). These results indicate that both migratory and adhesive functions of Gr-1+CD11b+ cells are intrinsically altered by the diabetic environment.

Gr-1+CD11b+ cell gene expression profile

Because diabetic-derived Gr-1+CD11b+ cells showed impaired proangiogenic capacity, we analyzed the expression profile of proangiogenic and proinflammatory genes in diabetic-derived Gr-1+CD11b+ cells versus nondiabetic equivalent cells. M1/M2 macrophage markers and angiogenic factors such as Vegf, Mmp-9, and Bv-8 were selected, as these genes have been previously shown to correlate with Gr-1+CD11b+ cell-mediated tumor-induced angiogenesis.12,16 As shown in Figure 3E, nondiabetic and diabetic-derived Gr-1+CD11b+ cells isolated from bone marrow (unstimulated by injury signals), express similar levels of M1/M2 markers. Interferon γ (M1 marker) was undetectable in Gr-1+CD11b+ cells obtained from bone marrow from both samples (data not shown). However, diabetic-derived Gr-1+CD11b+ cells showed lower levels of Vegf expression, and higher levels of Mmp-9 expression (Figure 3Eii). The expression of Bv-8 was undetectable in both samples (not shown). Interestingly, in response to injury, diabetic-derived Gr-1+CD11b+ cells expressed significantly lower levels of both M1 and M2 macrophage markers (Figure 3Ei), many of which are also considered proangiogenic (Tgf-β, Il-6, and Tnf-α), providing a possible mechanism for the failure of these cells to induce angiogenesis. Finally, we also examined expression of endogenous Hoxa3 and a previously identified Hoxa3 target gene, Cdc42,20 to evaluate Hoxa3 protein function. Although Hoxa3 mRNA levels were similar in both diabetic and nondiabetic-derived Gr-1+CD11b+ cells, Hoxa3 target gene activation was significantly decreased in diabetic-derived cells, suggesting Hoxa3 protein is dysfunctional in these cells (Figure 3Eiii).

Hoxa3 promotes HSC/Ps proliferation and myeloid-restricted progenitor differentiation

Gene transfer of HOXA3 to wounds of diabetic mice promotes neovascularization and is readily taken up and expressed by recruited BMD cells.10,20 This results in a suppression of the exacerbated inflammatory response characteristic of diabetic wounds and accelerates wound repair. We therefore wanted to test whether overexpression of Hoxa3 could alter proliferation, differentiation, chemotaxis, or adhesion of BMD stem/progenitor cells.

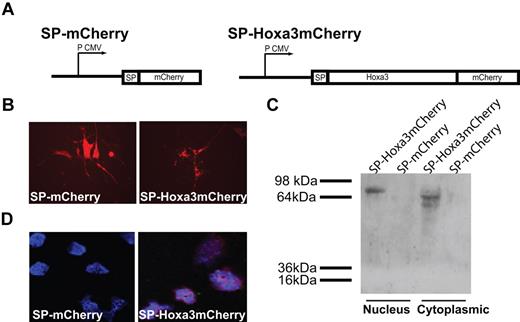

BMD HSC/Ps are activated in response to injury, mobilize from the bone marrow, home to injured tissue via circulation, and once there, promote neovascularization.31 To determine the effect of Hoxa3 function on HSC/Ps, we utilized direct protein delivery of Hoxa3 protein to HSC/Ps as described previously for Hoxb4.27 Hoxa3-mCherry fusion protein or mCherry control (Figure 4A) was continually delivered to HSC/Ps via long-term coculture with feeder layer cells expressing SP-Hoxa3-mCherry protein (or mCherry control) containing a SP. The signal peptide (SP) targets proteins to the secretory pathway and is cleaved before secretion.32 After secretion, the third α helix of the homeodomain directs internalization of Hoxa3-mCherry via receptor-independent passive translocation into HSC/Ps in coculture.27,33 Cells were cocultured for 4 weeks. Feeder layer cells were monitored for mCherry expression (Figure 4B), and samples of the hematopoietic cells were harvested for further analysis weekly. Uptake of the secreted Hoxa3-mCherry by HSC/Ps was verified by Western blot and confocal analyses (Figure 4C-D). Hoxa3-mCherry translocates into the cytoplasm and nucleus of HSC/Ps, while mCherry, which lacks the homeodomain, does not. Interestingly, nuclear Hoxa3-mCherry protein migrates more slowly than cytoplasmic Hoxa3-mCherry, which may be due to modifications, such as phosphorylation, that have been shown to be associated with regulation of Hox proteins.34

Design of Hoxa3-mCherry and mCherry plasmids and expression in HSC/Ps. (A) Schematic of signal peptide (SP)–Hoxa3-mCherry and SP-mCherry constructs, driven by the cytomegalovirus promoter (P CMV). (B) SP-mCherry, and SP-Hoxa3-mCherry, protein expression in AFT024 feeder layer cells, shown at original magnification × 200. (C) Western blot detection of mCherry in nuclear and cytoplasmic protein extraction of HSC/Ps cocultured with AFT024 cells secreting SP-Hoxa3-mCherry protein (predicted size = 73.17 kDa) or SP-mCherry control (predicted size = 26.73 kDa). (D) Immunofluorescent detection of mCherry in hematopoietic progenitor cells purified from coculture with AFT024/SP-mCherry feeder layer or AFT024/SP-Hoxa3-mCherry feeder layer. DAPI was used to label nuclei. Image is original magnification ×600.

Design of Hoxa3-mCherry and mCherry plasmids and expression in HSC/Ps. (A) Schematic of signal peptide (SP)–Hoxa3-mCherry and SP-mCherry constructs, driven by the cytomegalovirus promoter (P CMV). (B) SP-mCherry, and SP-Hoxa3-mCherry, protein expression in AFT024 feeder layer cells, shown at original magnification × 200. (C) Western blot detection of mCherry in nuclear and cytoplasmic protein extraction of HSC/Ps cocultured with AFT024 cells secreting SP-Hoxa3-mCherry protein (predicted size = 73.17 kDa) or SP-mCherry control (predicted size = 26.73 kDa). (D) Immunofluorescent detection of mCherry in hematopoietic progenitor cells purified from coculture with AFT024/SP-mCherry feeder layer or AFT024/SP-Hoxa3-mCherry feeder layer. DAPI was used to label nuclei. Image is original magnification ×600.

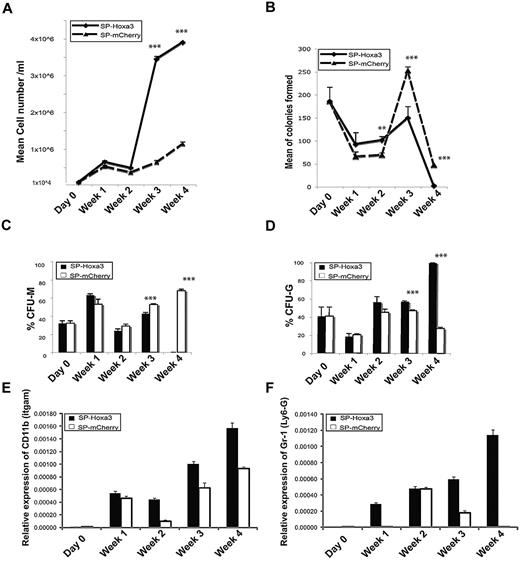

Hoxa3 significantly increased the number of viable hematopoietic cells after 3 weeks of coculture (Figure 5A), suggesting Hoxa3 enhances the proliferation rate or reduces cell death of HSC/Ps. To determine whether Hoxa3 promotes self-renewal of HSC/Ps or the proliferation of more mature hematopoietic cells, we performed colony assay analyses on samples removed from coculture. The total colony number from HSC/Ps receiving Hoxa3-mCherry was significantly less than the control HSC/Ps (Figure 5B), suggesting Hoxa3 does not promote self-renewal of HSC/Ps, but instead promotes the proliferation and differentiation of more mature hematopoietic cells.

Hoxa3 promotes proliferation and differentiation of HSC/Ps into Gr-1+CD11b+ myeloid cells. (A) Viable cell number at weekly time points following Hoxa3-mCherry or mCherry protein delivery to HSC/Ps. (B) Total colony forming units (CFU) at weekly time points following Hoxa3-mCherry or mCherry protein delivery to HSC/Ps. (C-D) The percentage of CFU-monocytic (C), and CFU-granulocytic (D), at weekly time points following Hoxa3-mCherry or mCherry protein delivery to HSC/Ps (error bars represent SEM, *P ≤ .05, **P ≤ .01, ***P ≤ .001). (E-F) qRT-PCR analyses of lineage-specific gene expression at weekly time points following Hoxa3-mCherry or mCherry protein delivery to HSC/Ps. Gr-1/Ly6g is a granulocytic marker, and CD11b/Itgam is a pan-myeloid marker.

Hoxa3 promotes proliferation and differentiation of HSC/Ps into Gr-1+CD11b+ myeloid cells. (A) Viable cell number at weekly time points following Hoxa3-mCherry or mCherry protein delivery to HSC/Ps. (B) Total colony forming units (CFU) at weekly time points following Hoxa3-mCherry or mCherry protein delivery to HSC/Ps. (C-D) The percentage of CFU-monocytic (C), and CFU-granulocytic (D), at weekly time points following Hoxa3-mCherry or mCherry protein delivery to HSC/Ps (error bars represent SEM, *P ≤ .05, **P ≤ .01, ***P ≤ .001). (E-F) qRT-PCR analyses of lineage-specific gene expression at weekly time points following Hoxa3-mCherry or mCherry protein delivery to HSC/Ps. Gr-1/Ly6g is a granulocytic marker, and CD11b/Itgam is a pan-myeloid marker.

Colony assays were also used to assess the differentiation potential of HSC/Ps during long-term coculture. HSC/Ps receiving Hoxa3-mCherry showed reduced multipotency compared with control HSC/Ps. After 3 weeks, Hoxa3 significantly increased the number of CFU-Gs and reduced the number of CFU-Ms. After 4 weeks, Hoxa3-treated cells had the capability to make only a few granulocytic colonies (Figure 5B-D), suggesting most cells were fully differentiated.

The effect of Hoxa3 protein expression on HSC/P differentiation was further investigated by gene expression analyses of lineage markers by qRT-PCR at weekly time points. After 3 weeks, Gr-1/Ly6g (polymorphonuclear cells/granulocytes marker) and CD11b/Itgam (myeloid lineage marker) expression was markedly increased in HSC/Ps receiving Hoxa3-mCherry compared with control cells. In contrast, CD19 (B lymphocyte marker) and CD5 (T lymphocyte marker) were undetectable in both cultures (data not shown). These results demonstrate that Hoxa3 can promote lineage commitment of HSC/Ps to the granulocytic Gr-1+CD11b+ cell fate.

The effect of Hoxa3 on the function of Gr-1+CD11b+ cells from the diabetic environment

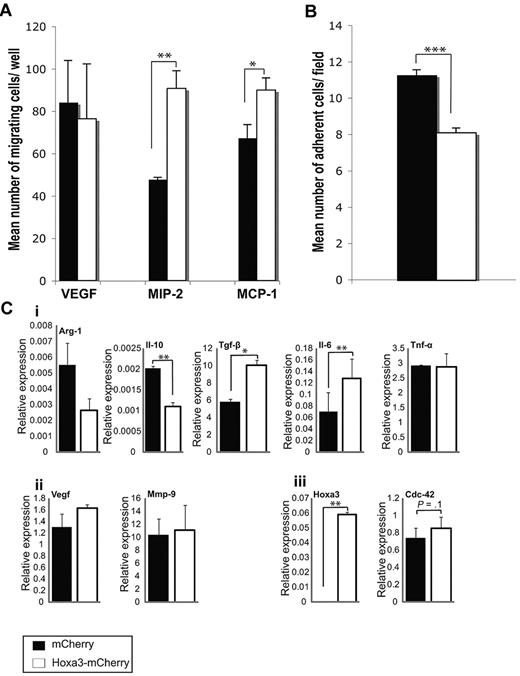

To assess if overexpression of Hoxa3 could rescue the altered adhesive and chemotactic phenotype of diabetic Gr-1+CD11b+ cells, Hoxa3-mCherry or control plasmid was nucleoporated into diabetic BMD Gr-1+CD11b+ cells. Cells were analyzed 24 hours after gene expression. Hoxa3-mCherry expression significantly increased the migration of diabetic-derived Gr-1+CD11b+ cells toward MIP-2 and MCP-1 chemoattractants, but did not have a significant effect on migration potential toward VEGF (Figure 6A). Expression of Hoxa3-mCherry also resulted in reduced adhesion of diabetic-derived Gr-1+CD11b+ cells onto TNF-α–activated endothelial cells (Figure 6B). These results indicate that overexpression of Hoxa3 in Gr-1+CD11b+ cells can rescue at least some of the altered behaviors induced by the diabetic environment. Rescue of behavioral changes by Hoxa3 was accompanied by changes in the gene expression profiles of diabetic-derived Gr-1+CD11b+ cells. Although M2 macrophage markers Arg-1 and Il-10 were repressed by Hoxa3, Tgf-β and Il-6 were significantly activated by Hoxa3. There was no change, however, in Tnf-α, Vegf, or Mmp-9 expression. Expression of Cdc42, a known Hoxa3 target gene,20 was completely restored, demonstrating that Hoxa3 function was rescued by overexpression (Figure 6C). Taken together, these data suggest that transcription factor reprogramming of myeloid cells ex vivo may revert them to a nondiabetic phenotype.

Effect of Hoxa3 on diabetic-derived Gr-1+CD11b+ cell function. (A) Migration assays of diabetic-derived Gr-1+CD11b+ cells transfected with mCherry or Hoxa3-mCherry toward VEGF, MIP-2, and MCP-1. (B) Adhesion assays of diabetic-derived Gr-1+CD11b+ cells (overexpressing Hoxa3-mCherry or mCherry alone) on TNF-α–activated endothelial cells. (C) Gene expression profile of diabetic Gr-1+CD11b+ cells overexpressing Hoxa3-mCherry or mCherry alone assessed by qRT-PCR. (i) Expression of M1 and M2 macrophage markers. (ii) Expression of angiogenic factors Vegf and Mmp-9. (iii) Expression of Hoxa3 and a representative Hoxa3 target gene, Cdc42. Error bars represent SEM, *P ≤ .05, **P ≤ .01, ***P ≤ .001.

Effect of Hoxa3 on diabetic-derived Gr-1+CD11b+ cell function. (A) Migration assays of diabetic-derived Gr-1+CD11b+ cells transfected with mCherry or Hoxa3-mCherry toward VEGF, MIP-2, and MCP-1. (B) Adhesion assays of diabetic-derived Gr-1+CD11b+ cells (overexpressing Hoxa3-mCherry or mCherry alone) on TNF-α–activated endothelial cells. (C) Gene expression profile of diabetic Gr-1+CD11b+ cells overexpressing Hoxa3-mCherry or mCherry alone assessed by qRT-PCR. (i) Expression of M1 and M2 macrophage markers. (ii) Expression of angiogenic factors Vegf and Mmp-9. (iii) Expression of Hoxa3 and a representative Hoxa3 target gene, Cdc42. Error bars represent SEM, *P ≤ .05, **P ≤ .01, ***P ≤ .001.

Discussion

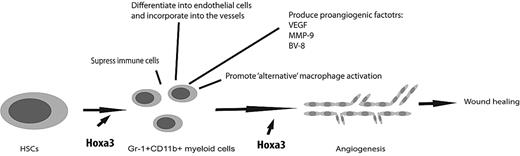

Aberrant mobilization, migration, recruitment, and/or retention, as well as differentiation of BMDCs are associated with impaired wound healing. The diabetic environment dramatically alters the composition of BMDCs in the wound, which consists predominantly of inflammatory cells,10,35 contributing to the development of chronic wounds in patients and animal models of diabetes.10,36 Gene transfer of HOXA3 to wounds of diabetic mice partially rescues this phenotype, as more endothelial progenitor cells are mobilized and accumulate in wound tissue, while inflammatory cell accumulation is suppressed.10,20 Here we report for the first time that overexpression of Hoxa3 protein in HSC/Ps promotes their proliferation and differentiation into granulocytic Gr-1+CD11b+ myeloid cells, which significantly promote CD34+ neovessels in diabetic wounds (Figure 7). Overexpression of other Hox-3 family members in HSC/Ps, such as Hoxb3, has also been reported to result in progressive myeloproliferation and increased granulopoiesis, suggesting that this may be a function common to Hox-3 group homeodomain proteins.37

Mechanism of Hoxa3 induction of proangiogenic Gr-1+CD11b+ myeloid cells and their contribution to injury-induced neovascularization and wound healing. Injury results in mobilization and recruitment of BMD stem/progenitor cells to the site of injury. Overexpression of Hoxa3 at the site of injury promotes the differentiation of BMD stem/progenitor cells into granulocytic Gr-1+CD11b+ cells, which promote neovascularization through the various mechanisms shown. Hoxa3 also rescues at least some of the aberrant phenotypes, such as defective migratory and adhesive properties, of Gr-1+CD11b+ cells in pathological conditions such as diabetes.

Mechanism of Hoxa3 induction of proangiogenic Gr-1+CD11b+ myeloid cells and their contribution to injury-induced neovascularization and wound healing. Injury results in mobilization and recruitment of BMD stem/progenitor cells to the site of injury. Overexpression of Hoxa3 at the site of injury promotes the differentiation of BMD stem/progenitor cells into granulocytic Gr-1+CD11b+ cells, which promote neovascularization through the various mechanisms shown. Hoxa3 also rescues at least some of the aberrant phenotypes, such as defective migratory and adhesive properties, of Gr-1+CD11b+ cells in pathological conditions such as diabetes.

Gr-1+CD11b+ cells have been characterized as immature myeloid cells with the potential to differentiate into granulocytes, monocytes, and dendritic cells depending on environmental cues.13-15,38 They have also been shown to differentiate in endothelial-like cells at the site of trauma and during tumorigenesis.13,16 In the present study, we show that diabetic mice have a higher percentage of Gr-1+CD11b+ cells in circulation and at sites of injury, but that these cells have impaired functions. The proliferation potential of diabetic-derived Gr-1+CD11b+ cells is reduced, they show impaired chemotaxis toward MIP-2 and MCP-1, and display increased adhesion onto activated endothelial cells. Although the in vivo consequences of these phenotypes are presently unclear, these properties likely affect their responsiveness to injury-induced signals and retention at the site of injury, and are associated with an increase in Gr-1+CD11b+ cells in the diabetic wound. Moreover, their differentiation potential is altered, as they have a decreased capability to differentiate along the granulocytic lineage and an increased capability to differentiate along the monocytic lineage compared with nondiabetic Gr-1+CD11b+ cells. This raises the question of whether monocytic versus granulocytic Gr-1+CD11b+ cells have differential effects on neovascularization. Identification of distinct monocytic and granulocytic Gr-1+CD11b+ cell marker expression will facilitate the sorting of these 2 subpopulations of cells and will allow this hypothesis to be tested.

Importantly, diabetic-derived Gr-1+CD11b+ cells fail to promote neovascularization in vivo, while Gr-1+CD11b+ cells isolated from nondiabetic mice significantly improve neovascularization in wounds of diabetic mice. Clues as to the important factors produced by these cells, such as Vegf and Tgf-β, come from studies in a variety of tumors. In the present study we compared the expression levels of these and other angiogenesis-related genes between diabetic-derived and nondiabetic-derived Gr-1+CD11b+ cells. Diabetic-derived cells express significantly lower levels of Vegf, one of the most potent proangiogenic factors known to date. However, Gr-1+CD11b+ cells can significantly promote tumor-associated angiogenesis independent of Vegf.11,12,16,39 Moreover, although diabetic-derived cells express higher levels of Mmp-9, it has been previously shown that excessive metalloproteinase activity in diabetic wounds destabilizes wound extracellular matrix, resulting in the loss of regulating cues for migrating angiogenic cells.40-42

Gr-1+CD11b+ cells can function as immune suppressor cells, causing CD8+ T-cell suppression by producing arginase and inducible nitric oxide synthase as well as other mechanisms.13,14,38,43 Depletion of CD8+ T cells at the wound site improves wound healing,44 although the relationship to the effect of Gr-1+CD11b+ cells on T cells and increased neovascularization is not clear. Moreover, polymorphonuclear type II (Gr-1+CD11b+) cells have been shown to alternatively activate macrophages.45 Although polymorphonuclear type II cells represent only a subset of Gr-1+CD11b+ cells, induction of M2 macrophages may be a mechanism by which Gr-1+CD11b+ cells promote angiogenesis. Gr-1+CD11b+ cells can also differentiate into macrophages, but cannot be classified with specific macrophages subtypes, as our analyses, consistent with previous studies (reviewed in38 ), show they express both M1 and M2 markers. Gr-1+CD11b+ cells derived from diabetic wounds, however, show significantly decreased expression of both M1 and M2 markers compared with nondiabetic-derived cells. As expression of these genes signify activation of these cells, significantly reduced expression of M1/M2 markers may point to a failure of these cells to mature appropriately in the diabetic wound environment.

Finally, overexpression of Hoxa3 in diabetic-derived Gr-1+CD11b+ cells rescues chemotaxis, adhesion, and gene expression defects intrinsic to these cells. In particular, Tgf-β was markedly up-regulated by 24 hours after Hoxa3 overexpression in Gr-1+CD11b+ cells. Tgf-β has recently been shown to have a potent anti-inflammatory, proangiogenic effect on Gr-1+CD11b+ cells, polarizing them to the “N2” tumor-associated neutrophil state.46 N2 tumor-associated neutrophils promote tumor growth by up-regulating proangiogenic factors and chemokines, and by suppressing the antitumor immune response. We propose that wound-associated neutrophils (WANs) may function in a parallel manner, with N1 WAN polarization characterized by a proinflammatory, cytotoxic state, and N2 WAN polarization characterized by a proangiogenic, prorepair state. Previous studies demonstrating that gene transfer of HOXA3 to wounds directly modulates recruited BMD cell behavior suggest that overexpression of Hoxa3 can reprogram BMD progenitor cell fate in vivo during tissue repair and regeneration, promoting neovascularization and wound repair (Figure 7). This may be due, at least in part, to promoting N2 polarization of WANs. Future studies will be focused on addressing this question, as well as understanding additional regulatory mechanisms governing Gr-1+CD11b+ myeloid cell behavior during tissue repair and regeneration.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Michal Smiga for excellent technical assistance, Mike Jackson for help with flow cytometry, Anne Warhurst for assistance with histology, Toki Takahashi for expertise in colony assay analysis, Richard Preziosi for advice on statistical analyses, and Ray Boot-Handford, Cay Kielty, Matt Ronshaugen, Tom Millard, Nancy Boudreau, and Mat Hardman for useful comments and discussion on the manuscript.

This work was supported by the Iranian Ministry of Health and Medical Education (to E.M.), and the Healing Foundation (to J.C.C. and K.A.M.).

Authorship

Contribution: E.M. designed and performed experiments, analyzed results, made the figures, and wrote the paper; J.C.C. performed experiments; and K.A.M. designed and performed experiments, analyzed results, and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Kimberly Mace, The Healing Foundation Centre, Faculty of Life Sciences, University of Manchester, Oxford Rd, Manchester M13 9PT, United Kingdom; e-mail: kimberly.mace@manchester.ac.uk.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal