Abstract

Complement alternative pathway plays an important, but not clearly understood, role in neutrophil-mediated diseases. We here show that neutrophils themselves activate complement when stimulated by cytokines or coagulation-derived factors. In whole blood, tumor necrosis factor/formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine or phorbol myristate acetate resulted in C3 fragments binding on neutrophils and monocytes, but not on T cells. Neutrophils, stimulated by tumor necrosis factor, triggered the alternative pathway on their surface in normal and C2-depleted, but not in factor B-depleted serum and on incubation with purified C3, factors B and D. This occurred independently of neutrophil proteases, oxidants, or apoptosis. Neutrophil-secreted properdin was detected on the cell surface and could focus “in situ” the alternative pathway activation. Importantly, complement, in turn, led to further activation of neutrophils, with enhanced CD11b expression and oxidative burst. Complement-induced neutrophil activation involved mostly C5a and possibly C5b-9 complexes, detected on tumor necrosis factor- and serum-activated neutrophils. In conclusion, neutrophil stimulation by cytokines results in an unusual activation of autologous complement by healthy cells. This triggers a new amplification loop in physiologic innate immunity: Neutrophils activate the alternative complement pathway and release C5 fragments, which further amplify neutrophil proinflammatory responses. This mechanism, possibly required for effective host defense, may be relevant to complement involvement in neutrophil-mediated diseases.

Introduction

Neutrophils and the complement alternative pathway (AP) are major effectors of cell-mediated and humoral innate immunity. The analysis of complement knockout mice, in experimental inflammatory diseases, shed new light on the participation of complement AP in neutrophil-mediated diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis,1 membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis,2 ischemia-reperfusion injury,3 and, more recently, antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody (ANCA)-associated small-vessel vasculitis.4 In an experimental model of ANCA-associated small-vessel vasculitis, the unexpected observation that factor B-deficient mice were protected from the disease, whereas C4-deficient mice were not,4 revealed the alternative complement pathway as a new partner of this neutrophil-mediated disease. It was thus reasonable to propose that neutrophils could participate in the activation of complement AP.

If the activation of neutrophils by complement fragments, such as C3a or C5a, is well known, data on complement triggering by neutrophils are scarce. Neutrophil proteases and oxidants have been reported to activate complement in cell-free systems,5-7 and supernatants of ANCA-activated neutrophils were shown to release unknown complement activating factors.4 We investigated the ability of the neutrophil surface to activate complement and deposit active complement fragments on their plasma membrane.

Complement activation on blood cells is kept under control by fluid phase regulators (ie, plasma factor H and C4b-binding protein) and by cell membrane regulators (ie, decay accelerating factor DAF [CD55] and membrane cofactor protein MCP [CD46]). These regulators prevent the formation and accelerate the decay of C3bBb and C4b2a alternative and classic C3-convertases and act as cofactors for factor I-mediated C3b and C4b proteolysis. Neutrophils also express CR1 (CD35), which is the only cofactor allowing factor I to fully degrade C3 from iC3b into C3d and C3g. Finally, membrane CD59 restricts the formation of the C5b-9 membrane attack complex.

We here show that proinflammatory and coagulation-induced stimuli allow neutrophils to activate autologous complement despite these strict controls.

Methods

Antibodies and reagents

Anticomplement components, complement-depleted sera, purified C3 factor B, and properdin were from Quidel, P- or C3-depleted sera, factor D from CompTech, and the C5-depleted serum from Calbiochem. Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–labeled anti-CD11b and anti-CD35, IgG1 isotypic control, phycoerythrin (PE)–labeled goat anti–mouse IgG, streptavidin were from Beckman Coulter, anti–CD46-PE, anti-CD88 (clone S5/1) from AbD Serotec, anti–CD55-PE, anti–CD59-PE, IgG1 isotypic control, annexin-FITC from BD Biosciences. Anti–C5b-9 (B7) monoclonal antibody (mAb) was a kind gift from Paul Morgan. Goat IgG, formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine (fMLP), phorbol myristate acetate (PMA), 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescin diacetate (DCFHDA), diphenyleneiodonium chloride (DPI), and propidium iodide were from Sigma-Aldrich, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) from PeproTech, lepirudin (Refludan) from Bayer, corn trypsin inhibitor (CTI) from Haematologic Technologies, human tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI) from American Diagnostica, and the C5a receptor and the C3a receptor antagonists, W-54011 and SB290157, respectively, from Calbiochem. PolymorphPrep was from Axis-Shield. AB blood group normal human serum was obtained from the Etablissement Français du Sang, with agreement for studies on healthy volunteers.

Whole blood and neutrophils

Blood from healthy volunteers was collected in ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), lepirudin (50 μg/mL), without or with 5 U/mL CTI and 30nM TFPI, or in 12.5mM ethyleneglycoltetraacetic acid (EGTA) and 3mM Mg2+. Platelet-free polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs) were prepared from ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid anticoagulated blood on PolymorphPrep as described,8 without lysing contaminant erythrocytes to avoid leukocyte activation. PMNs (2 × 106/mL) were suspended in Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS, Invitrogen) containing 1mM Ca2+/Mg2+ (HBSS2+) in bovine serum albumin (BSA)–coated tubes. Protocols used for whole blood or PMNs activation are given in the corresponding figure legends. After neutrophil activation, AB normal human serum, autologous serum, or plasma was added, to a final one-third dilution, for a further 30-minute incubation at 37°C.

Immunolabeling and flow cytometry

Plasma was extensively washed off whole blood or PMN samples with PBS, 1% BSA, 0.1% sodium azide (PBA) before labeling. Washed samples were preincubated 20 minutes at 4°C with heat-aggregated goat IgG, to block Fc-gamma receptors, before labeling with specific mAbs. Erythrocytes were lysed from whole blood samples with FACS lysis solution (BD Biosciences), according to the manufacturer's instructions, before adding the PE-labeled secondary antibody. When antineutrophil antibodies were present during cell activation, labeling was then performed with biotinylated anti-C3d and PE-streptavidin.

Cells were analyzed by flow cytometry on a FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences). Results are given as mean fluorescence intensity (MFI).

Apoptosis evaluation and measure of oxidative burst

Annexin V binding and propidium iodide labeling were used to analyze the apoptotic and necrotic state of neutrophils by flow cytometry. Intracellular oxidants were measured after PMN preincubation with the fluorescent probe DCFHDA (5μM) for 10 minutes at 37°C as described.9

Properdin ELISA

Properdin was measured in neutrophil supernatant using a homemade specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), in which wells were coated with a polyclonal antiproperdin antibody and revealed with the same biotinylated antibody.

Microparticle recovery and labeling

Microparticles were isolated from neutrophil supernatant and analyzed as described.10 Briefly, after neutrophil activation, samples were centrifuged for 20 minutes at 4°C at 350g to remove entire cells. Supernatants were further cleared from cell debris by a 20-minute centrifugation at 800g. Microparticles were pelleted by a 30-minute centrifugation at 15 000g.

Statistical analysis

MFI was compared using a paired t test analysis when 2 conditions were compared or analysis of variance when 3 or more conditions were compared.

Results

Complement activation in whole blood and C3 deposition on leucocytes

Complement activation by neutrophils was first investigated by in vitro incubation, for 30 minutes at 37°C, of whole blood treated with lepirudin, a specific thrombin inhibitor that prevents clotting but not complement activation11 (Figure 1A). Cell-bound C3 fragments were analyzed by flow cytometry using an anti-C3d mAb. They were detected on neutrophils and monocytes (Figure 1B-C), and their levels of cell-bound C3d increased in the presence of leukocyte agonists (TNF with fMLP or PMA). No C3 fragment whatsoever was detected on lymphocytes (Figure 1D), except for a small subpopulation (∼ 5%), which appeared as strongly C3-positive. Further analysis of this subpopulation revealed that it included neither T cells (CD3-negative) nor NK cells (CD16a-negative), but that approximately 55% were B cells (CD20-positive). Activation of the complement AP by B lymphocytes has, indeed, been previously reported.12 Leukocyte-bound C3 deposits were not observed in control blood drawn in EDTA (data not shown) or in EGTA (Figure 1E), preventing both coagulation and complement, whether blood was incubated or not with leukocyte agonists.

Complement activation by leukocytes in whole blood. Samples (100 μL) of whole blood with lepirudin were incubated at 37°C without or with PMA 10 ng/mL for 30 minutes or with TNF-α 10 ng/mL for 15 minutes, followed by a 15-minute incubation with fMLP 10−6M. After several washes, they were labeled with anti-C3d (“Immunolabeling and flow cytometry”). (A) FACSScan FSC/SSC dot blot analysis of all leukocytes. (B-D) Anti-C3d fluorescence histograms of cells restricted to the neutrophil (B), monocyte (C), or lymphocyte (D) FSC/SSC gate, from unstimulated blood (bold line) or blood stimulated with TNF/fMLP or PMA (thin lines). The shaded peak represents the isotypic IgG1control labeling. (E) Anti-C3d MFI measured on neutrophils from blood drawn in 20mM EDTA 12.5mM EGTA, without or with 3mM Mg2+, or in lepirudin, activated or not with TNF 10 ng/mL 30 minutes, fMLP 10−6M 15 minutes, or TNF/fMLP as in panel B (mean ± SD, n = 3 experiments).

Complement activation by leukocytes in whole blood. Samples (100 μL) of whole blood with lepirudin were incubated at 37°C without or with PMA 10 ng/mL for 30 minutes or with TNF-α 10 ng/mL for 15 minutes, followed by a 15-minute incubation with fMLP 10−6M. After several washes, they were labeled with anti-C3d (“Immunolabeling and flow cytometry”). (A) FACSScan FSC/SSC dot blot analysis of all leukocytes. (B-D) Anti-C3d fluorescence histograms of cells restricted to the neutrophil (B), monocyte (C), or lymphocyte (D) FSC/SSC gate, from unstimulated blood (bold line) or blood stimulated with TNF/fMLP or PMA (thin lines). The shaded peak represents the isotypic IgG1control labeling. (E) Anti-C3d MFI measured on neutrophils from blood drawn in 20mM EDTA 12.5mM EGTA, without or with 3mM Mg2+, or in lepirudin, activated or not with TNF 10 ng/mL 30 minutes, fMLP 10−6M 15 minutes, or TNF/fMLP as in panel B (mean ± SD, n = 3 experiments).

Blood was then drawn in EGTA/Mg13 to prevent coagulation and complement classic and lectin pathways while allowing the complement AP. No C3 fragments were then observed on resting neutrophils (Figure 1E, black bars), which implies that the complement activation previously observed in lepirudin-blood was the result of in vitro activation of calcium-dependent coagulation enzymes upstream of the lepirudin-blocked thrombin. Our attempts to prevent coagulation by blocking both intrinsic and extrinsic pathways with CTI and human TFPI, which inhibit FXIa and FVIIa, respectively, were unsuccessful, presumably because these inhibitors delay but do not completely prevent coagulation. Indeed, clotting was delayed but appeared, together with cell-bound C3, after a 20-minute incubation at 37°C, despite the presence of up to 150 μg/mL CTI and 0.35 μg/mL TFPI (data not shown).

The addition of neutrophil stimuli, TNF, fMLP, or fMLP after TNF priming (TNF/fMLP), in EGTA/Mg whole blood, led to significant C3d deposits on neutrophils (Figure 1E, gray bars), demonstrating that cytokine- or chemoattractant-stimulated leucocytes activate the AP in whole blood, resulting in membrane-bound C3. The levels of C3d deposits were higher in lepirudin-blood because of calcium-dependent coagulation enzymes. Moreover, neutrophil stimulation was limited in the EGTA-Mg2+ situation by the calcium requirement for fMLP- and TNF-induced efficient activation.

Activated neutrophils trigger the AP, leading to cell-bound C3 fragments and an amplification of neutrophil responses

Similarly, isolated neutrophils incubated in autologous lepirudin-plasma (Figure 2A) resulted in cell-bound C3 deposits, which increased when cells were preactivated with TNF-α with fMLP or with PMA, in parallel with neutrophil CD11b up-regulation (data not shown).

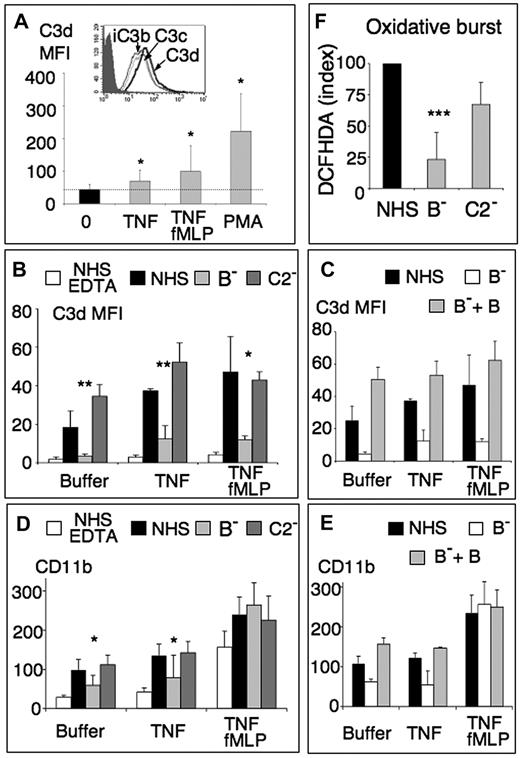

Neutrophils activate the complement AP and vice-versa. (A) Anti-C3d MFI of isolated PMNs labeled after a 30-minute incubation (2 × 106/mL) at 37°C in HBSS2+ in BSA-coated tubes, without (0) or with 10 ng/mL TNF-α ± 10−6M fMLP for the last 15 minutes of incubation, or with 10 ng/mL PMA, followed by a 30-minute incubation with one-third vol/vol autologous lepirudin-plasma (mean ± SD, n = 6). (Inset) Fluorescence histograms of TNF/fMLP activated PMNs labeled with anti-C3c, anti-C3d, and anti-iC3b mAbs or with the IgG1 control (shaded peak). (B-D) Anti-C3d (B-C) and anti-CD11b (D-E) MFI, measured by flow cytometry, on PMNs preincubated in HBSS2+ (buffer), 30 minutes with TNF-α 2 ng/mL (TNF), or TNF/fMLP (TNF/fMLP) as defined in “Results,” followed by a 30-minute incubation with one-third AB-serum without (NHS) or with 10mM EDTA (NHS-EDTA), with one-third factor B-depleted serum without (B−) or with added 100 μg/mL purified factor B (B− + B) or with one-third C2-depleted (C2−) serum (mean ± SD, n = 4 for B, D; n = 3 for C, E). Statistical analysis comparisons were performed between samples with B− serum and the corresponding NHS control. *P < .05. **P < .01. ***P < .001. (F) Oxidative response of PMNs pretreated for 10 minutes with 5μM DCFHDA before stimulation by TNF-α and incubation in one-third normal or depleted sera. DCFHDA index of PMNx submitted to stimulus x in serum x = (MFIx − MFI resting PMNs in NHS) × 100/MFI x-stimulated PMN in NHS − MFI resting PMN in NHS).

Neutrophils activate the complement AP and vice-versa. (A) Anti-C3d MFI of isolated PMNs labeled after a 30-minute incubation (2 × 106/mL) at 37°C in HBSS2+ in BSA-coated tubes, without (0) or with 10 ng/mL TNF-α ± 10−6M fMLP for the last 15 minutes of incubation, or with 10 ng/mL PMA, followed by a 30-minute incubation with one-third vol/vol autologous lepirudin-plasma (mean ± SD, n = 6). (Inset) Fluorescence histograms of TNF/fMLP activated PMNs labeled with anti-C3c, anti-C3d, and anti-iC3b mAbs or with the IgG1 control (shaded peak). (B-D) Anti-C3d (B-C) and anti-CD11b (D-E) MFI, measured by flow cytometry, on PMNs preincubated in HBSS2+ (buffer), 30 minutes with TNF-α 2 ng/mL (TNF), or TNF/fMLP (TNF/fMLP) as defined in “Results,” followed by a 30-minute incubation with one-third AB-serum without (NHS) or with 10mM EDTA (NHS-EDTA), with one-third factor B-depleted serum without (B−) or with added 100 μg/mL purified factor B (B− + B) or with one-third C2-depleted (C2−) serum (mean ± SD, n = 4 for B, D; n = 3 for C, E). Statistical analysis comparisons were performed between samples with B− serum and the corresponding NHS control. *P < .05. **P < .01. ***P < .001. (F) Oxidative response of PMNs pretreated for 10 minutes with 5μM DCFHDA before stimulation by TNF-α and incubation in one-third normal or depleted sera. DCFHDA index of PMNx submitted to stimulus x in serum x = (MFIx − MFI resting PMNs in NHS) × 100/MFI x-stimulated PMN in NHS − MFI resting PMN in NHS).

C3 is covalently bound to surfaces via its C3d portion, and the anti-C3d mAb thus reacts with all cell-bound fragments of C3 (ie, C3b, iC3b, C3d,g, and C3d). The anti-C3c mAb does not recognize the latter 2 fragments, which have lost their C3c portion. The anti-C3d/anti-C3c labeling ratio of PMNs incubated with serum or lepirudin plasma (Figure 2A inset) allowed to estimate that approximately 75% of deposited fragments are C3d,g or C3d, whereas 25% still contain C3c and thus represent iC3b, as shown by the specific anti-iC3b labeling or C3b molecules.

Neutrophils were then preincubated either in HBSS (buffer), with TNF 2 ng/mL (TNF) or with fMLP 1μM after a priming step with TNF 10 ng/mL (T/fMLP) and then treated with AB group normal human serum (NHS), as a complement source. This defines 3 conditions of increasing neutrophil stimulation: (1) stimulation by serum coagulation-derived compounds only (buffer), (2) moderate preactivation by TNF before the incubation in serum (TNF), and (3) intense neutrophil preactivation (TNF/fMLP). They resulted in increasing levels of neutrophil-bound C3 fragments (Figure 2B), which were prevented by EDTA (NHS-EDTA) but still occurred in EGTA/Mg (data not shown), showing that the AP was involved. This was further confirmed by incubating neutrophils in sera immunochemically depleted of factor B, with no functional AP, or depleted of C2, to prevent both classical and lectin pathways. As shown in Figure 2B, membrane C3 deposits were similar on neutrophil incubation in normal or C2-depleted (C2−) serum, whereas they were mostly prevented in the absence of factor B (B−). The addition of purified factor B to the B-depleted serum (B− + B) restored the serum ability to deposit C3 on the surface of neutrophils (Figure 2C). Neutrophils thus trigger the AP, with no detectable activation of the classical and lectin pathways.

Importantly, the incubation in serum of buffer- or TNF-treated neutrophils resulted in increased levels of CD11b expression (Figure 2D), which paralleled those of cell-bound C3, shown in Figure 2B. This CD11b up-regulation was similar in normal or C2-depleted serum but was inhibited in factor B-depleted serum and restored by the addition of purified factor B (Figure 2E). By contrast, the intense neutrophil preactivation by TNF/fMLP resulted in maximal CD11b membrane expression, which was not significantly enhanced by the incubation in serum and not prevented in factor B-depleted serum.

This complement-induced amplification of neutrophil responses was confirmed by the analysis of the oxidative burst. The incubation of TNF-preactivated neutrophils in normal or C2-depleted human serum resulted in an increase of intracellular oxidation of the fluorescent probe DCFHDA (Figure 2F), which was significantly prevented in factor B-depleted serum, showing the participation of the complement AP. There again, neutrophil preactivation with TNF/fMLP induced a maximal response, which was identical in normal or B-depleted serum (data not shown).

Complement activation is triggered on the membrane of neutrophils and is not related to a decreased expression of complement control proteins or apoptosis

To test whether complement was triggered by neutrophil secreted fluid phase activators, cells were activated with TNF/fMLP and then extensively washed before the incubation with serum (Figure 3A). This washing step did not decrease the resulting levels of neutrophil-bound C3d, thus showing that the neutrophil surface itself activates complement.

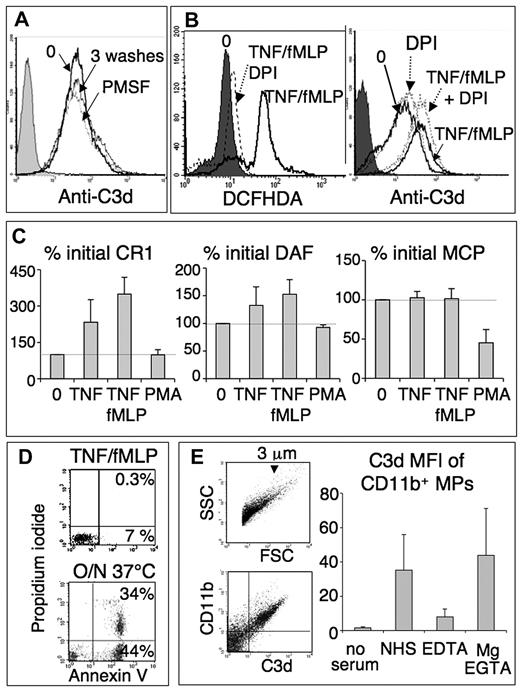

Complement activation by neutrophils is not related to apoptosis, serine proteases, oxidants, or a down-regulation of complement control proteins. (A) Anti-C3d histogram of TNF/fMLP-activated PMNs, unwashed (0), washed 3 times, or treated with 1mM phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride for 10 minutes and washed, before the incubation with serum one-third as in Figure 2A. (B) DCFHDA and anti-C3d histograms of a representative experiment (of 3), in which 2 × 106/mL PMNs were preincubated for 1 hour with shaking and in HBSS+BSA without Mg, to avoid cell adhesion, without or with 10μM DPI (dotted lines). Mg (1mM) was then added, and cells were activated, incubated in serum, and labeled with anti-C3d as in Figure 2A. To measure the oxidative response, PMNs with or without DPI were treated for 10 minutes with 5μM DCFHDA before cell activation and immediately analyzed, without addition of serum. The shaded peaks represent nonactivated PMNs (0) in the left panel and the control IgG1 isotype in the right panel. (C) Neutrophils, activated as in Figure 2A, were labeled, without addition of plasma, with FITC- or PE-labeled anti-CR1, -DAF, and -MPC mAbs and analyzed by flow cytometry. Results are mean plus or minus SD of MFI normalized with the expression of unactivated PMNs (100%, dotted line). (D) FL1/FL2 dot blots of PMNs activated as in Figure 2A, washed and incubated for 10 minutes in annexin-binding buffer with annexin-FITC and 10 μg/mL propidium iodide, and analyzed by flow cytometry. Apoptotic neutrophils, resulting from a 20-hour incubation at 37°C, were used as positive control. (E) Neutrophil-derived microparticles activate the complement AP. Neutrophils were activated with TNF/fMLP as in Figure 2A and microparticles collected from their supernatant (“Microparticle recovery and labeling”). They were incubated in AB-serum (NHS) one-third, without or with 20mM EDTA or 16.7mM EGTA and 1.6mM Mg and double labeled with anti-CD11b-FITC and biotinylated anti-C3d, followed by streptavidin-PE. The FSC/SSC dot blot shows microparticles (left panel), which are mostly less than or equal to 3 μm.8 Fluorescent dot-blots obtained with microparticles in NHS show that most neutrophil-derived, CD11b-positive microparticles are strongly C3d-positive (middle panel, upper right quadrant). The right panel shows the mean plus or minus SD of C3d MFI of CD11b/C3d-positive microparticles released in the various conditions (n = 3).

Complement activation by neutrophils is not related to apoptosis, serine proteases, oxidants, or a down-regulation of complement control proteins. (A) Anti-C3d histogram of TNF/fMLP-activated PMNs, unwashed (0), washed 3 times, or treated with 1mM phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride for 10 minutes and washed, before the incubation with serum one-third as in Figure 2A. (B) DCFHDA and anti-C3d histograms of a representative experiment (of 3), in which 2 × 106/mL PMNs were preincubated for 1 hour with shaking and in HBSS+BSA without Mg, to avoid cell adhesion, without or with 10μM DPI (dotted lines). Mg (1mM) was then added, and cells were activated, incubated in serum, and labeled with anti-C3d as in Figure 2A. To measure the oxidative response, PMNs with or without DPI were treated for 10 minutes with 5μM DCFHDA before cell activation and immediately analyzed, without addition of serum. The shaded peaks represent nonactivated PMNs (0) in the left panel and the control IgG1 isotype in the right panel. (C) Neutrophils, activated as in Figure 2A, were labeled, without addition of plasma, with FITC- or PE-labeled anti-CR1, -DAF, and -MPC mAbs and analyzed by flow cytometry. Results are mean plus or minus SD of MFI normalized with the expression of unactivated PMNs (100%, dotted line). (D) FL1/FL2 dot blots of PMNs activated as in Figure 2A, washed and incubated for 10 minutes in annexin-binding buffer with annexin-FITC and 10 μg/mL propidium iodide, and analyzed by flow cytometry. Apoptotic neutrophils, resulting from a 20-hour incubation at 37°C, were used as positive control. (E) Neutrophil-derived microparticles activate the complement AP. Neutrophils were activated with TNF/fMLP as in Figure 2A and microparticles collected from their supernatant (“Microparticle recovery and labeling”). They were incubated in AB-serum (NHS) one-third, without or with 20mM EDTA or 16.7mM EGTA and 1.6mM Mg and double labeled with anti-CD11b-FITC and biotinylated anti-C3d, followed by streptavidin-PE. The FSC/SSC dot blot shows microparticles (left panel), which are mostly less than or equal to 3 μm.8 Fluorescent dot-blots obtained with microparticles in NHS show that most neutrophil-derived, CD11b-positive microparticles are strongly C3d-positive (middle panel, upper right quadrant). The right panel shows the mean plus or minus SD of C3d MFI of CD11b/C3d-positive microparticles released in the various conditions (n = 3).

The participation of neutrophil cationic proteases, which could bind to the cell surface and activate complement components,5 was excluded by treating neutrophils with the broad irreversible serine-protease inhibitor phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride before the incubation with serum. This antiprotease treatment did not decrease the level of cell-bound C3 (Figure 3A).

Similarly, the participation of neutrophil oxidants was analyzed using the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate-oxidase inhibitor diphenyliodonium (DPI). DPI efficiently prevented the neutrophil oxidative burst triggered by TNF/fMLP, as measured by DCFHDA fluorescence (Figure 3B left panel) but had no effect on the levels of neutrophil-bound C3 (Figure 3B right panel).

Complement activation could result from a defective membrane control. We thus measured the expression of membrane control proteins CD35 (CR1), CD55 (DAF), CD46 (MCP), and CD59, before and after neutrophil stimulation by TNF, TNF/fMLP, or PMA. As shown in Figure 3C, neutrophil activation by TNF and TNF/fMLP resulted in a 3-fold increase of CR1 expression, consistent with the exocytosis of CR1 storage pools in secretory vesicles. On azurophil granule mobilization by PMA, CR1 up-regulation was most probably balanced by its shedding by elastase,14 the net effect being an absence of modulation. The results with DAF (CD55) expression were similar (ie, a slight up-regulation with TNF and TNF/fMLP) and no effect with PMA. The expression of MCP (CD46) was not modified by TNF and fMLP but was significantly down-regulated by PMA. Finally, CD59 was only slightly up-regulated by TNF/fMLP and PMA (data not shown). In summary, the levels of membrane control proteins were either unchanged or up-regulated and thus cannot explain the ability of neutrophils to trigger the AP.

Because the membrane of apoptotic cells is known to activate complement, we tested whether in vitro activated neutrophils showed an apoptotic phenotype. After a 30-minute incubation with TNF/fMLP (Figure 3D) or PMA (data not shown), 80% to 95% of neutrophils remained annexin/propidium iodide negative, compared with spontaneously apoptotic cells observed after overnight incubation (Figure 3D, 37°C).

Neutrophil-derived microparticles activate the complement AP

If, as shown by the washing step described in Figure 3A, the plasma membrane of neutrophils is able to activate complement, this could also be the case of membrane microparticles released by activated neutrophils. Microparticles, isolated by ultracentrifugation from the supernatant of TNF/fMLP-activated neutrophils, were incubated in normal serum and labeled with anti-CD11b, to identify neutrophil-derived microparticles and with anti-C3d to detect particle-bound C3 fragments. As shown in Figure 3E, C3 fragments were detected on all CD11b-positive microparticles. This was the result of the complement AP because similar C3d levels were observed on incubation in NHS/EGTA/Mg2+, but not in EDTA. The comparison of forward scatter/side scatter (FSC/SSC) dot plots showed that the mean size of microparticles was 1/45th the mean size of neutrophils, whereas the mean level of microparticle-bound C3d (MFI) was 1.4-fold the neutrophil-bound C3d level (data not shown). We can thus calculate that the density of membrane-bound C3d molecules was, as a mean, 60-fold higher on microparticles than on entire neutrophils.

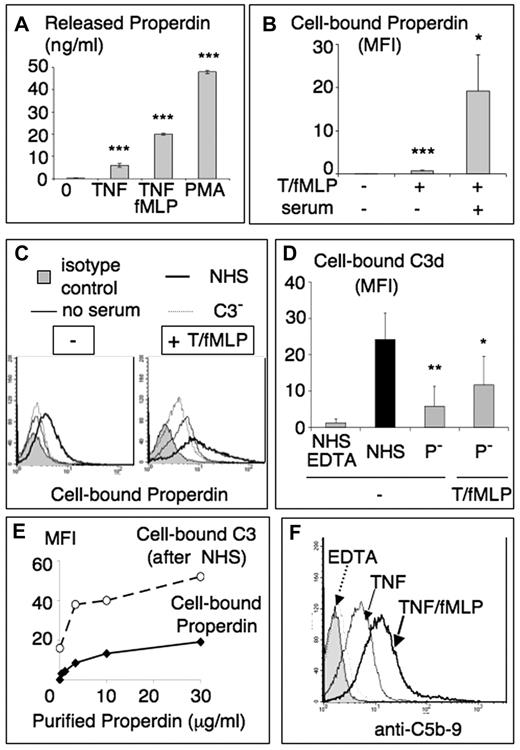

Complement activation by neutrophils results in cell-bound properdin and the formation of a C5-convertase

Neutrophils contain intracellular pools of properdin,15 which are released on stimulation by TNF, TNF/fMLP or PMA, as measured by a specific properdin enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Figure 4A). Slight but significant levels of cell-bound properdin, assessed by flow cytometry (Figure 4B), were observed on neutrophils activated with TNF/fMLP or PMA in the absence of exogenous complement, with no detectable membrane-bound C3 (data not shown). When serum was added, a 10- to 50-fold increase of cell-bound properdin was measured (Figure 4B) presumably via C3b deposits able to bind properdin. Indeed, as shown in Figure 4C, the level of cell-bound properdin increased on neutrophil incubation in NHS but not in C3-depleted serum. When neutrophils were incubated in properdin-depleted serum (P−), the level of deposited C3d was strikingly decreased, compared with normal human serum (Figure 4D), confirming the importance of serum properdin in stabilizing the AP C3 convertase. Neutrophil preactivation by TNF/fMLP, to promote properdin secretion, enhanced the amount of deposited C3 in P-depleted serum, suggesting a participation of neutrophil properdin.

Properdin is secreted by cytokine-activated neutrophils, binds to cells, and promotes the formation of C3/C5 convertases. PMNs were activated as in Figure 2A without the addition of plasma. (A) Supernatants were collected and centrifuged twice at 400g to remove all intact cells. The presence of properdin in these supernatants was measured using a specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay described in “Properdin ELISA.” Results are mean properdin concentration plus or minus SD of triplicates from 3 different experiments. (B) Neutrophils, activated as in Figure 2A, without or with incubation with serum one-third, were washed and labeled with a specific antiproperdin mAb. Results are mean plus or minus SD of MFI (n = 4). (C) Cells preactivated or not with TNF/fMLP, as in Figure 2, were incubated in HBSS (no serum, thin line) or in one-third diluted normal (NHS, dark line) or C3-depleted (C3−, dotted line) serum. Cell bound properdin was measured by flow cytometry as in panel B with an antiproperdin mAb, compared with an isotype control (gray peak). Representative experiment from 3 similar ones. (D) TNF/fMLP activated PMNs were incubated with AB-serum (NHS) one-third, with or without 10mM EDTA, or with one-third properdin-depleted serum (P−). They were then labeled with anti-C3d mAb. Results are mean plus or minus SD of MFI (n = 3). (E) Nonactivated neutrophils (2 × 106/mL in HBSS2+) were incubated with increasing concentrations of purified properdin for 20 minutes at 37°C, then either labeled with an antiproperdin mAb (plain line) as in panel B or further incubated with one-third NHS and labeled for cell bound C3d (dotted line). Results are expressed as MFI. (F) Anti-C5b-9 fluorescence histogram of PMNs activated with TNF with or without fMLP and incubated in serum one-third, as in Figure 2A, and labeled with anti-CD5b-9 mAb. Neutrophils incubated in serum with 10mM EDTA represent the negative control (dotted line), whereas the shaded peak was labeled with the IgG1 isotype control. *P < .05. **P < .01. ***P < .001.

Properdin is secreted by cytokine-activated neutrophils, binds to cells, and promotes the formation of C3/C5 convertases. PMNs were activated as in Figure 2A without the addition of plasma. (A) Supernatants were collected and centrifuged twice at 400g to remove all intact cells. The presence of properdin in these supernatants was measured using a specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay described in “Properdin ELISA.” Results are mean properdin concentration plus or minus SD of triplicates from 3 different experiments. (B) Neutrophils, activated as in Figure 2A, without or with incubation with serum one-third, were washed and labeled with a specific antiproperdin mAb. Results are mean plus or minus SD of MFI (n = 4). (C) Cells preactivated or not with TNF/fMLP, as in Figure 2, were incubated in HBSS (no serum, thin line) or in one-third diluted normal (NHS, dark line) or C3-depleted (C3−, dotted line) serum. Cell bound properdin was measured by flow cytometry as in panel B with an antiproperdin mAb, compared with an isotype control (gray peak). Representative experiment from 3 similar ones. (D) TNF/fMLP activated PMNs were incubated with AB-serum (NHS) one-third, with or without 10mM EDTA, or with one-third properdin-depleted serum (P−). They were then labeled with anti-C3d mAb. Results are mean plus or minus SD of MFI (n = 3). (E) Nonactivated neutrophils (2 × 106/mL in HBSS2+) were incubated with increasing concentrations of purified properdin for 20 minutes at 37°C, then either labeled with an antiproperdin mAb (plain line) as in panel B or further incubated with one-third NHS and labeled for cell bound C3d (dotted line). Results are expressed as MFI. (F) Anti-C5b-9 fluorescence histogram of PMNs activated with TNF with or without fMLP and incubated in serum one-third, as in Figure 2A, and labeled with anti-CD5b-9 mAb. Neutrophils incubated in serum with 10mM EDTA represent the negative control (dotted line), whereas the shaded peak was labeled with the IgG1 isotype control. *P < .05. **P < .01. ***P < .001.

Unlike serum properdin, purified properdin preparations are known to bind various cells or microorganisms, resulting from high-order properdin oligomers and properdin aggregates. As shown in Figure 4E, purified properdin was indeed able to bind resting neutrophils, in a dose-related manner. This binding triggered an efficient complement activation, as shown by cell-bound C3 deposits on nonstimulated neutrophils, incubated with purified properdin and washed before the addition of serum (NHS).

Properdin allows the formation of the C3bBbC3bP C5-convertase, and C5 was indeed activated because C5b-9 MAC complexes were detected on neutrophils incubated in serum (Figure 4F), their levels increasing together with neutrophil activation state and being absent on neutrophils incubated in serum EDTA.

Role of C5-derived fragments in complement-mediated neutrophil activation

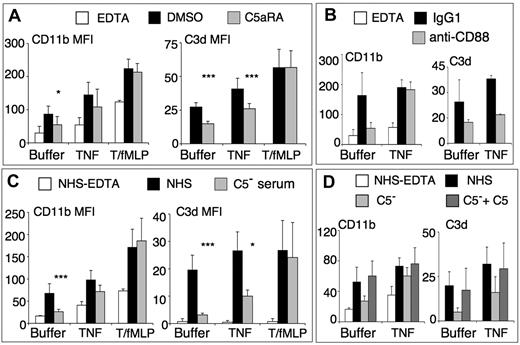

Because C5a and sublytic amounts of C5b-9 are known to activate neutrophils, we tested the role of C5 participation, by pretreating neutrophils with the nonpeptide antagonist of the C5a receptor, W-5401,16 before stimulation with “buffer,“ “TNF,” or “TNF/fMLP” (as in Figure 2) and final incubation in normal serum (Figure 5A). The C5aR-antagonist partially inhibited C3d deposits and CD11b up-regulation on serum-activated or TNF-activated cells. By contrast, it had no effect on C3d deposits and CD11b up-regulation on TNF/fMLP-preactivated cells. Similar results were obtained by pretreating neutrophils with a blocking anti-C5aR (anti-CD88) mAb, compared with an IgG1 isotype control (Figure 5B). In this experimental setting, neutrophils were incubated in serum with EGTA/Mg, to prevent the activation of the complement classical pathway by the anti-C5aR mAb.

Role of C5-derived fragments in complement-dependent neutrophil activation. (A) PMNs (2 × 106/mL in HBSS2+) were preincubated with DMSO 1/104 or 10μM C5aR-antagonist W-54011 for 5 minutes, then preactivated with different conditions as in Figure 2, and finally incubated with one-third NHS. The control was buffer-treated PMNs incubated in NHS-EDTA (white bars). CD11b (left) and cell-bound C3d (right) were measured by flow cytometry and expressed as mean plus or minus SD of MFI (n = 3 or 4) and statistical analysis comparison performed between samples with C5aRA and the corresponding DMSO control. *P < .05. ***P < .001. The EDTA control is not shown in the C3d panel because it is close to zero. (B) Similar analysis, where concentrated PMNs were pretreated with anti-CD88 or the IgG1 control, for 15 minutes at room temperature, then diluted to 2 × 106/mL in HBSS2+ and preactivated as in Figure 2, then incubated with one-third of the volume of NHS with EGTA/Mg. (C-D) PMNs were preactivated as in Figure 2, then incubated with one-third vol/vol NHS, C5-depleted serum, or with C5-depleted serum supplemented with 100 μg/mL final concentration of purified C5 (D). Results are mean plus or minus SD MFI (n = 3 or 4) and statistical analysis comparison performed between samples with C5− serum and the corresponding NHS control. *P < .05. ***P < .001.

Role of C5-derived fragments in complement-dependent neutrophil activation. (A) PMNs (2 × 106/mL in HBSS2+) were preincubated with DMSO 1/104 or 10μM C5aR-antagonist W-54011 for 5 minutes, then preactivated with different conditions as in Figure 2, and finally incubated with one-third NHS. The control was buffer-treated PMNs incubated in NHS-EDTA (white bars). CD11b (left) and cell-bound C3d (right) were measured by flow cytometry and expressed as mean plus or minus SD of MFI (n = 3 or 4) and statistical analysis comparison performed between samples with C5aRA and the corresponding DMSO control. *P < .05. ***P < .001. The EDTA control is not shown in the C3d panel because it is close to zero. (B) Similar analysis, where concentrated PMNs were pretreated with anti-CD88 or the IgG1 control, for 15 minutes at room temperature, then diluted to 2 × 106/mL in HBSS2+ and preactivated as in Figure 2, then incubated with one-third of the volume of NHS with EGTA/Mg. (C-D) PMNs were preactivated as in Figure 2, then incubated with one-third vol/vol NHS, C5-depleted serum, or with C5-depleted serum supplemented with 100 μg/mL final concentration of purified C5 (D). Results are mean plus or minus SD MFI (n = 3 or 4) and statistical analysis comparison performed between samples with C5− serum and the corresponding NHS control. *P < .05. ***P < .001.

Similar experiments were performed with the C3a receptor antagonist SB 290157, which had no effect on C3d deposits or CD11b up-regulation in any condition (data not shown).

The role of C5-derived fragments was further investigated using a C5-depleted serum (Figure 5C). Intense activation of neutrophils by TNF/fMLP resulted in maximal CD11b membrane expression and cell-bound C3d levels, which were similar in C5-depleted serum and in normal serum. By contrast, serum-induced CD11b up-regulation and C3d deposits, observed in TNF preactivated and, particularly, in “buffer” neutrophils submitted to serum stimulation only, were mostly prevented in C5-depleted serum. Altogether, these results demonstrate that the AP activation, resulting in C3 deposits and CD11b up-regulation, becomes C5-independent when neutrophils are fully activated by TNF/fMLP. By contrast, C5 fragments, mostly C5a, are required when neutrophils are weakly activated after serum incubation without or with TNF preactivation.

It was thus important to add purified C5 to the C5-depleted serum to ensure that the absence of effect of this serum was indeed only the result of the lack of C5 and not another missing neutrophil activating stimulus. As shown in Figure 5D, the addition of purified C5 completely restored the ability of the C5-depleted serum to up-regulate CD11b and to deposit C3d on neutrophils, in both “buffer” and “TNF” condition.

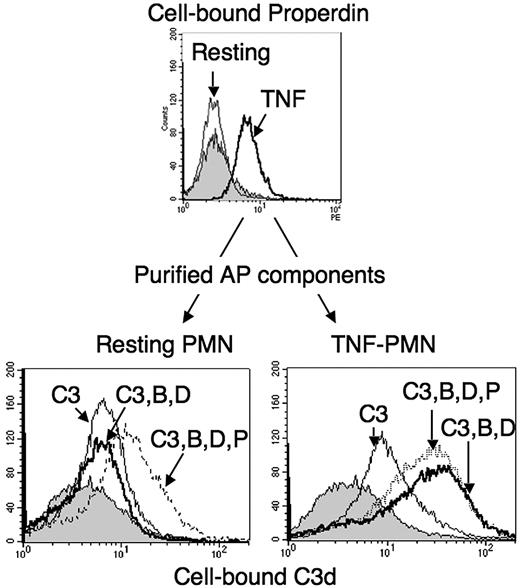

Formation an AP C3-convertase on neutrophils, with purified AP factors

To directly demonstrate that neutrophils are able to activate the AP, TNF preactivated cells, expressing properdin on their surface (Figure 6 upper panel), were washed and further incubated with a mixture of purified C3, factor B and factor D, with or without added purified properdin. Cell-bound C3 fragments were then measured on TNF-activated neutrophils (Figure 6 lower right panel), compared with resting neutrophils incubated with the same AP factors (Figure 6 lower left panel). The results showed a 3- to 4-fold increase of cell-bound C3 on TNF-activated PMNs incubated with C3, factor B and factor D, compared with those incubated with C3 alone. This was not observed on resting neutrophils. Most importantly, when purified properdin was added to resting neutrophils, they became able to support activation with purified C3, B and D, resulting in enhanced C3 deposits. Purified properdin did not increase C3 deposition on TNF-activated cells, suggesting that the endogenous neutrophil-secreted properdin was sufficient to stabilize the C3 convertase.

C3-convertase formation from purified AP components, on the surface of neutrophils. PMNs (2 × 106/mL in HBSS2+) in BSA-coated tubes were either kept in buffer (resting) or activated for 30 minutes with 10 ng/mL TNF-α at 37°C (TNF) and a sample used to measure cell-bound properdin by flow cytometry (upper panel). PMNs were then washed with HBSS− and resuspended at 2 × 106/mL in HBSS, with a final 2mM concentration of Ca2+ and Mg2+, containing 330 μg/mL pure C3 either alone (C3, thin line) or with factor B 100 μg/mL and factor D 1 μg/mL (C3,B,D dark line) or with factors B and D and properdin 2 μg/mL (C3,B,D,P dotted line), for 30 minutes at 37°C. The negative control was given by a sample of PMNs incubated for 30 minutes in one-third NHS-ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (gray peak). Cells were then washed and cell-bound C3 measured by flow cytometry. The right shifts from the gray peak background position represent the binding of C3 to neutrophils in each sample. Flow cytometry histograms of one representative experiment, of 3 similar ones, are shown.

C3-convertase formation from purified AP components, on the surface of neutrophils. PMNs (2 × 106/mL in HBSS2+) in BSA-coated tubes were either kept in buffer (resting) or activated for 30 minutes with 10 ng/mL TNF-α at 37°C (TNF) and a sample used to measure cell-bound properdin by flow cytometry (upper panel). PMNs were then washed with HBSS− and resuspended at 2 × 106/mL in HBSS, with a final 2mM concentration of Ca2+ and Mg2+, containing 330 μg/mL pure C3 either alone (C3, thin line) or with factor B 100 μg/mL and factor D 1 μg/mL (C3,B,D dark line) or with factors B and D and properdin 2 μg/mL (C3,B,D,P dotted line), for 30 minutes at 37°C. The negative control was given by a sample of PMNs incubated for 30 minutes in one-third NHS-ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (gray peak). Cells were then washed and cell-bound C3 measured by flow cytometry. The right shifts from the gray peak background position represent the binding of C3 to neutrophils in each sample. Flow cytometry histograms of one representative experiment, of 3 similar ones, are shown.

Some C3 fragments were able to bind TNF-activated, but not resting, neutrophils in the absence of factors B and D (compared with the NHS-EDTA–negative control, shown by the gray peak). This probably represents C3(H20) molecules, present in purified C3 preparations and presumably binding properdin on the surface of TNF-activated neutrophils. We indeed observed that a C3 preparation, frozen and thawed several times and presumably containing mainly C3(H2O), bound more efficiently TNF-activated neutrophils than the fresh C3 preparation (data not shown). However, this binding was not enhanced in the presence of factors B and D, showing that hemolytically active C3 is required to form a C3-convertase.

Discussion

The novel description of an activation of alternative complement pathway on the surface of neutrophils, minimally stimulated with inflammatory cytokines or chemoattractants, sheds light on the pathogenesis of inflammatory disorders involving neutrophils, complement, and possibly coagulation.

To our knowledge, it is the first observation that complement is activated in whole blood by neutrophils and monocytes, stimulated by cytokines or by coagulation-derived factors. A major difficulty for such type of studies is to obtain a source of functional complement without clotting activity. Coagulation-derived factors directly or indirectly activate neutrophils and complement, whereas most anticoagulants inhibit complement. In the presence of lepirudin, which inhibits thrombin and clotting without modifying complement,11 C3 was still deposited on unstimulated neutrophils, suggesting a triggering by coagulation factors upstream of thrombin. Indeed, factor XIa and factor Xa are known to cleave and activate C3 and C5,17 whereas factor XIa and the tissue factor/factor VIIa complex could potentially activate neutrophils via the PAR-2 receptor.18 Our data showing that the activation of coagulation-derived factors is sufficient to trigger neutrophil and complement activation may be relevant to in vivo thrombotic events and, in particular, those reported in neutrophil-mediated diseases, such as ANCA vasculitis.19,20

Results obtained with whole blood drawn in EGTA/Mg show that resting neutrophils do not activate complement, when calcium-dependent coagulation and complement pathways are blocked. They become able to activate the AP when stimulated by inflammation cytokines or chemoattractants. Indeed, isolated neutrophils activated complement in normal serum with EGTA/Mg2+ and in C2-depleted serum, but not in factor B-depleted serum. Purified factor B restored the ability of factor B-depleted serum to deposit C3 fragments on neutrophils, thus showing that no other factor was missing in the immunodepleted B− serum. Our results obtained with purified C3 and factors B and D further demonstrate that neutrophils are able to support the activation of an AP C3-convertas, when activated by TNF, in the absence of serum coagulation-derived stimuli.

Neutrophil-secreted factors, such as serine proteases or oxidants, have been reported to activate complement in the fluid phase.5-7 Here we describe a complement activation trigger distinct from serine proteases or oxidants because it was not inhibited by phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride or DPI. Moreover, this trigger is clearly present on the surface of neutrophils because it was not removed by cell washing.

Intact neutrophils have been shown to release small amounts of fluid phase C3bBbP in lepirudin-plasma.21 Similarly, ANCA-activated neutrophils have been reported to release unknown complement activating factors in their supernatants.4 We propose that these “fluid phase” activators would be membrane microparticles, or ectosomes, which are released by stimulated neutrophils in vitro and in vivo,10,22 and were previously reported to activate the classic pathway.23 The results obtained in this study demonstrate an activation of the AP by neutrophil-released microparticles incubated in serum or EGTA/Mg-plasma, leading to high levels of microparticle-bound C3d.

Various mechanisms are proposed for the activation of complement by a cell surface: (1) Cell membranes changes occurring during apoptosis or necrosis transform cells into AP activators but neutrophils, in our experimental settings, showed no sign of apoptosis. (2) Decreased levels of membrane-inserted complement regulators could result in complement activation, as has been proposed for apoptotic cells.24 In the conditions described here, CR1 and DAF expressions were either up-regulated or stable, confirming previous reports.25,26 PMA slightly decreased MCP expression, presumably via proteolytic shedding,27 but TNF/fMLP had no effect. Thus, complement activation by stimulated neutrophils is not related to a defect of membrane expression of control proteins. (3) The most probable hypothesis is that neutrophil-secreted properdin results in local complement activation, as has been proposed by several authors.28,29 We here confirm that neutrophils secrete properdin on degranulation stimuli and show that it results in low but significant amounts of cell-bound properdin. On activation by TNF/fMLP, which leads to maximal properdin secretion by neutrophils, significant levels of cell-bound C3 were observed in properdin-depleted serum. This illustrates the participation of neutrophil properdin to complement AP activation on neutrophils. By triggering the AP, this properdin would focus complement activation on the neutrophil surface, as has been described on bacteria, yeast, apoptotic cells,30,31 and normal proximal tubular epithelial cells.32 Plasma properdin is, however, required for an efficient C3b feedback loop, to amplify complement activation. Indeed, lower levels of C3d deposits were observed on neutrophils incubated in properdin-depleted serum, compared with normal human serum. The major role of properdin (ie, to target complement activation on properdin-positive cells) would explain the absence of complement deposition on lymphocytes, which do not secrete properdin, when whole blood was stimulated with the pan-leukocyte activator PMA. We observed that neutrophil-derived and purified serum properdin bind to native or stimulated neutrophils, whereas serum native properdin is unable to do so in the absence of C3. It has been proposed that neutrophil-secreted properdin could be somehow similar to purified properdin, which binds various surfaces, resulting from high-order properdin oligomers and properdin aggregates.31,33,34 The low but significant levels of cell-bound properdin, resulting from the secretion of nanograms of properdin per milliliter, suggest a high affinity of this secreted properdin for the neutrophil membrane, although the local concentration, at the membrane level during degranulation, may be much higher. Alternatively, we cannot exclude that some of the properdin, stored in secondary granules, is already bound to the intragranular membrane and thus appears on the plasma membrane on degranulation without being secreted. It is tempting to speculate that properdin itself triggers complement activation on the neutrophil surface. We, indeed, observed that the addition of purified properdin to resting neutrophils is sufficient to activate complement in whole serum or in a mixture of purified AP factors, resulting in neutrophil-bound C3. However, we cannot exclude that complement activation on cytokine-activated neutrophils also results from membrane changes, such as a desialylation, which is known to transform cell surfaces from complement AP nonactivating to activating surfaces, by lowering the control by serum factor H.35 Desialylation is known to occur during neutrophil stimulation, resulting from the release of endogeneous sialidases.36

The activation of complement on neutrophil surface might have several consequences: (1) Neutrophil-bound C3b and iC3b fragments may be recognized by complement receptors CR1 or CR3 on erythrocytes and leukocytes and by P-selectin on platelets.37 This could participate in leukocyte, platelet, and red cell interactions with neutrophils adherent to microvessel walls, leading to vascular occlusion and endothelial injury as in various thromboinflammatory diseases.38 Moreover, neutrophil-bound iC3b reacting with CR3 on bystander phagocytes could be added as new partners to the proposed model of vascular injury and thrombosis emphasizing the central role of iC3b/CR3 interactions, based on the analysis of CR3- or C3-deficient mice.39 (2) The local release of active complement fragments in the close proximity of neutrophils may participate in the opsonization and killing of microorganisms, in contact with phagocytes before their ingestion. Similarly, released C5b-9 and C5a fragments could locally induce or amplify the proinflammatory phenotype of endothelial cells in close contact with adherent neutrophils 40-42 (3) C3 opsonized neutrophils may finally be cleared by macrophages, which express C3 receptors, in the same way as stressed, infected, or apoptotic cells, which activate complement.43 (4) Most importantly, we here describe a new consequence (ie, an increase of neutrophil degranulation and oxidative burst) when complement AP is activated on their surface. Complement opsonization of “healthy” cells involved in natural defense against infection, such as neutrophils, would thus result in an amplification of cell responses instead of, or before, cell clearance. This may also be true for thrombin- or shear-activated platelets, which trigger complement activation37,44 and are, in turn, further activated by complement.45 Finally, complement-induced stimulation of neutrophil responses was observed after neutrophil preactivation by coagulation-derived factors or by limiting amounts of TNF, but not after intense activation by TNF/fMLP. This result implies that the amplification of neutrophil stimulation by complement, activated on their surface, may be important when concentrations of cytokines or neutrophil stimuli are suboptimal, as would occur at early inflammation or thrombosis stages. The effect of complement would become negligible in the face of intense neutrophil activation by high cytokine concentrations and by bacterial-derived compounds, such as fMLP.

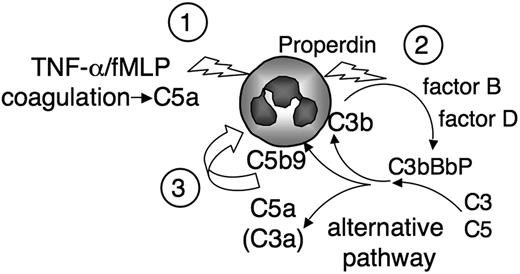

C5a is a pivotal component of our model, schematized in Figure 7, and we observed that the C5aR-antagonist, the blocking anti-C5aR mAb, or the absence of C5 prevented most of cell-bound C3 deposits and complement-induced neutrophil activation. C5a may act at 2 levels: Coagulation factors release C5a, which could be a sufficient trigger (Figure 7, “1”) because C3 deposits were observed on neutrophils, in the absence of cytokine, on incubation in normal human serum but not in C5-depleted serum. The formation, on the neutrophil surface, of a properdin-stabilized C5 convertase (Figure 7, “2”) releases C5a and C5b-9 complexes (Figure 7, “3”), which are potent neutrophil activators and most probably mediate the amplification of neutrophil response.46 We indeed observed that the activation of neutrophils by complement was not exclusively the result of the direct effect of C5a occurring in serum during clotting. The alternative complement pathway was also involved because the serum-induced CD11b up-regulation or oxidative burst was, at least in part, prevented in factor B-depleted serum and not in factor B-depleted serum restored with purified factor B. The participation of C5-derived fragments in the amplification of neutrophil responses by complement AP suggests that the anti-C5 blocking therapeutic antibody eculizumab, described as highly beneficial in complement-mediated hemolytic and uremic syndrome, could be extended to neutrophil-mediated inflammatory diseases.47

Schematic view of complement neutrophil activation amplification loop. Neutrophils stimulated by suboptimal doses of cytokine or coagulation-derived factors, possibly via the release of C5a, (1) secrete properdin, which triggers the complement AP on the neutrophil membrane. (2) This further activates neutrophils and enhances cell responses, possibly via the juxtamembranous release of complement-derived active fragments. (3)

Schematic view of complement neutrophil activation amplification loop. Neutrophils stimulated by suboptimal doses of cytokine or coagulation-derived factors, possibly via the release of C5a, (1) secrete properdin, which triggers the complement AP on the neutrophil membrane. (2) This further activates neutrophils and enhances cell responses, possibly via the juxtamembranous release of complement-derived active fragments. (3)

In conclusion, our results highlight a novel role of the AP, which not only amplifies complement activation by other pathways via the C3b-feedback loop but also magnifies cell responses involved in inflammation, thrombosis, and immunity. This mechanism could be central in all innate immune reactions and would be involved in a wide spectrum of diseases.48 We propose that the central role of complement AP in inflammatory tissue damages would be the result of a new amplification loop (summarized in Figure 7), where an initial stimulus activates neutrophils, which trigger the complement AP, which in turn further enhances neutrophil responses, such as degranulation and oxidative burst.

Presented in abstract form at the 14th International Vasculitis and ANCA Workshop, Lund, June 2009 and at the 12th European Meeting on Complement in Human Disease, Visegrad, September 2009.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Professor Paul Morgan, Cardiff University, United Kingdom, for the gift of the anti-C5b-9 monoclonal antibody.

This work was supported by Association pour l'Utilization du Rein Artificiel AURA, Amgen, and Baxter. L.R. was a recipient of an EMBO Long Term Fellowship ALTF 444-2007.

Authorship

Contribution: L.C. designed and performed research; L.R. designed research, performed research, and analyzed data; S. Bigot performed research; S. Brachemi designed research; V.F.-B. and P.L. designed research and analyzed data; and L.H.-M. designed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Lise Halbwachs-Mecarelli, Inserm U 845, Hôpital Necker, 161 rue de Sèvres, 75015 Paris, France; e-mail: lise.halbwachs@inserm.fr.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal