Abstract

Platelet GPIb-IX receptor complex has 3 subunits GPIbα, GPIbβ, and GPIX, which assemble with a ratio of 1:2:1. Dysfunction in surface expression of the complex leads to Bernard-Soulier syndrome. We have crystallized the GPIbβ ectodomain (GPIbβE) and determined the structure to show a single leucine-rich repeat with N- and C-terminal disulphide-bonded capping regions. The structure of a chimera of GPIbβE and 3 loops (a,b,c) taken from the GPIX ectodomain sequence was also determined. The chimera (GPIbβEabc), but not GPIbβE, forms a tetramer in the crystal, showing a quaternary interface between GPIbβ and GPIX. Central to this interface is residue Tyr106 from GPIbβ, which inserts into a pocket generated by 2 loops (b,c) from GPIX. Mutagenesis studies confirmed this interface as a valid representation of interactions between GPIbβ and GPIX in the full-length complex. Eight GPIbβ missense mutations identified from patients with Bernard-Soulier syndrome were examined for changes to GPIb-IX complex surface expression. Two mutations, A108P and P74R, were found to maintain normal secretion/folding of GPIbβE but were unable to support GPIX surface expression. The close structural proximity of these mutations to Tyr106 and the GPIbβE interface with GPIX indicates they disrupt the quaternary organization of the GPIb-IX complex.

Introduction

GPIb-IX-V complex is an abundant membrane receptor complex on the platelet surface that plays a critical role in mediating platelet adhesion to the damaged vessel wall under conditions of high shear stress.1 Platelets adhere, and integrins are subsequently activated by interactions of GPIb-IX-V with VWF bound to the subendothelium. How GPIb-IX-V transmits the VWF-binding signal across the membrane is not clear, partly because the structure and organization of this complex receptor remain to be elucidated. Because GPV is only weakly associated with the receptor complex and is not essential for complex expression, assembly, VWF binding, or signal transduction,2,3 we focus on the GPIb-IX complex here.

The GPIb-IX complex contains 3 subunits, GPIbα, GPIbβ, and GPIX, with a 1:2:1 stoichiometry.4 Each subunit is a type I transmembrane (TM) protein, containing an ectodomain with leucine-rich repeats (LRRs),5 a single TM helix, and a relatively short cytoplasmic tail. The GPIbα ectodomain contains binding sites for a growing list of hemostatically important ligands, including VWF and thrombin.6-8 Covalent and noncovalent interactions are important to the quaternary stabilization of the receptor. GPIbα links to 2 GPIbβ subunits through membrane-proximal disulfide bonds to constitute the GPIb complex.4 GPIX tightly associates with GPIb through noncovalent interactions.9 Assembly of these subunits into a tightly integrated complex is also supported by genetic evidence. Bernard-Soulier syndrome (BSS) is a hereditary bleeding disorder that is characterized in most cases by giant platelets, low platelet counts, and little or no expression of GPIb-IX on the platelet surface.10,11 More than 30 mutations have been identified from patients with BSS and mapped to GPIbα, GPIbβ, and GPIX,12,13 indicating that all 3 subunits are required for proper surface expression of the complex.

Consistent with genetic evidence, efficient surface expression of GPIb-IX also requires all 3 subunits in transfected mammalian cells.14 For instance, GPIX alone cannot be expressed on the surface of transfected Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells. Only when coexpressed with GPIbβ can it be detected on the cell surface, indicating that GPIbβ interacts with and stabilizes GPIX.15,16 Coexpression with GPIbβ and GPIbα produces even higher surface expression levels of GPIX.14 Thus, the surface expression level of individual subunits can be used as an indicator for the assembly of GPIb-IX and, implicitly, quaternary interactions among the subunits. Using this approach, we had previously shown that TM domains of GPIb-IX are essential for complex assembly.17,18 Biophysical characterization of recombinant GPIb-IX–derived TM peptides in detergent micelles indicated that they form a parallel 4-helical bundle and that their association leads to formation of membrane-proximal disulfide bonds between GPIbα and GPIbβ, further stabilizing the complex.4,19

In addition to TM domains, GPIbβ and GPIX ectodomains, termed GPIbβE and GPIXE in this study, respectively, are required for proper assembly and efficient surface expression of GPIb-IX, because numerous BSS-causing mutations have been mapped to these domains. However, GPIXE is intrinsically unstable, impeding structural and biochemical investigation. Taking advantage of the high sequence homology between GPIbβE and GPIXE (Figure 1A), we had earlier identified a GPIbβE/GPIXE chimera (abbreviated to GPIbβEabc) that interacts with GPIbβ in a manner that mimics the GPIX ectodomain.16 Here, we report X-ray crystal structures of human GPIbβE and GPIbβEabc. These structures, in combination with assays to probe inter-subunit interactions in the context of full-length subunits, give insight into GPIb-IX quaternary assembly and provide greater understanding of the molecular mechanism of BSS.

Methods

Expression and purification of recombinant GPIbβE and GPIbβEabc

To produce recombinant GPIbβE and GPIbβEabc, a gene fragment encoding human GPIbβ and GPIbβEabc residues Cys1-Leu121, respectively, was cloned into a pBlueBac4.5-derived baculovirus expression vector (Invitrogen) that appended the signal sequence of baculovirus envelope gp67 (amplified from pAcGP67A vector; BD Biosciences) and a Ser-Ser-hexahistidine tag to the N-terminus and C-terminus of GPIbβE, respectively. The chimeric GPIbβEabc contains 3 stretches of GPIX sequences: Ala29-Arg36, Ser49-Gln60, and Ser76-Arg87 (Figure 1A). The mature protein with the hexahistidine tag was secreted from the infected insect cells into the culture media. After 40%-85% ammonium sulfate fractionation of the collected culture media, the protein was dissolved in 50mM Tris·HCl, 20mM imidazole, 4mM EGTA, pH 7.6, at 4°C overnight; loaded onto the Ni-sepharose column (QIAGEN); and subsequently eluted with 50mM Tris·HCl, 300mM NaCl, 100mM imidazole, and 4mM EGTA, pH 7.6. The eluent was concentrated and further purified by gel filtration chromatography (Superdex 75; GE Healthcare) in 20mM Tris·HCl and 100mM NaCl, pH 7.0 (supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). N-terminal sequencing analysis of the purified protein confirmed the proper removal of the signal sequence.

Crystallization and structural determination

Purified GPIbβE with the hexahistidine tag was dialyzed into 20mM Tris·HCl, and 100mM NaCl, pH 7.0, and concentrated to 18 mg/mL for crystallization at 19°C. Sparse matrix screens (QIAGEN) obtained initial conditions and refinement resulted in the crystallization condition of 1.6M (NH4)2SO4, 0.4M LiCl, and 0.1M MES, pH 6.5. For GPIbβEabc the sample was concentrated to 1.5 mg/mL, and sparse matrix screens (PACT; Molecular Dimensions) identified initial conditions at 10°C from D2 (form 1) and A9 (form 2). The D2 condition is 0.1M MMT buffer pH 5 (MMT buffer is a mixture of DL-malic acid, MES, and Tris base in the molar ratios 1:2:2, DL-malic acid/MES/Tris base), 25% (w/v) polyethylene glycol 1500 and A9 is 0.2M lithium chloride, 0.1M sodium acetate, pH 5, and 20% polyethylene glycol 6000. Single crystals were transferred to the same solution containing 25% and 10% glycerol, respectively, and flash cooled in liquid nitrogen. Diffraction data were collected with beam line ID23-2, ID29-1, and ID23-2, respectively, for GPIbβE, GPIbβEabc (form 1), and GPIbβEabc (form 2) at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility. The GPIbβE structure was determined by molecular replacement with the use of the structure for C-terminal 133 residues of the Nogo-66 ectodomain (PDB code, 1P8T)20 and programs MrBUMP21 and PHASER.22 Initial electron density maps were improved with 2-fold noncrystallographic symmetry and solvent flattening with the use of the CCP4 program suite. Model rebuilding was performed with COOT23 and crystallographic refinement was performed in REFMAC.24 Crystallographic statistics are listed in Table 1. A Ramachandran plot shows 115 residues in preferred regions, 2 in allowed regions, and none in outlier regions. The GPIbβEabc form 1 structure was determined by molecular replacement with the use of the GPIbβE structure. The model was built with COOT and refined with REFMAC. A Ramachandran plot shows 116 of residues in favored regions and 3 in allowed regions with none in outlier regions. The form 2 structure was determined by molecular replacement with the use of the form 1 structure and is identical with the exception of side chains involved in crystal packing.

GPIbβ and GPIX constructs

Vectors expressing hemagglutinin (HA)–GPIbβ (full-length GPIbβ with N-terminal HA epitope tag, YPYDVPDYA), HA-GPIbβE (GPIbβ extracellular residues Cys1-Leu121 with N-terminal HA tag), HA-GPIbβEabc-GPIXTC (HA-tagged GPIbβEabc fused to GPIX TM and cytoplasmic domains), HA-GPIbβEabc (HA-tagged GPIbβEabc), GPIX, and GPIbα had been described.16,17,25 Site-directed mutagenesis was performed by the overlap extension PCR procedure with the use of the above-mentioned vectors as the template. Each PCR fragment was digested by appropriate restriction enzymes and subcloned into its target vector as described earlier.17 All constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Transient transfection of CHO cells

CHO K1 cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS at 37°C and 5% CO2. Transient transfection of vectors encoding GPIbα, GPIbβ, and GPIX-derived constructs, in desired combinations, into CHO K1 cells was performed with lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) as described earlier.17 Key parameters of the transfection, such as cell density and DNA amount, were kept the same as previously described to allow proper comparison among various constructs.17 After transfection, the cells were grown for an additional 48 hours before being analyzed.

Characterization of effects of GPIbβ or GPIX mutations

The secretion and folding of mutant HA-GPIbβE and HA-GPIbβEabc proteins were characterized as previously described.16 Briefly, the N-terminally HA-tagged protein secreted into the culture medium was collected by coimmunoprecipitation with the use of the anti-HA Ab, resolved in 12% Bis-Tris SDS gel in the presence or absence of reducing agents, and immunoblotted by HRP-conjugated anti-HA Ab. The cellular expression and assembly of the GPIb-IX complex was assessed by Western blot of each subunit as previously described.17,18 The surface expression levels of GPIbα, HA-tagged GPIbβ, and GPIX in transiently transfected cells were measured with WM23, anti-HA, and FMC25 Abs, respectively, on a Beckman-Coulter Gallios flow cytometer as described.17,25 To assess the mutational effect, the measured mean fluorescence value of the entire cell population (10 000 cells) is normalized with the value of CHO cells expressing wild-type GPIb-IX complex (GPIbα/HA-GPIbβ/GPIX) being 100% and that of empty vector-transfected cells 0%.17 Groups were compared with the 2-tailed Student t test.

Results

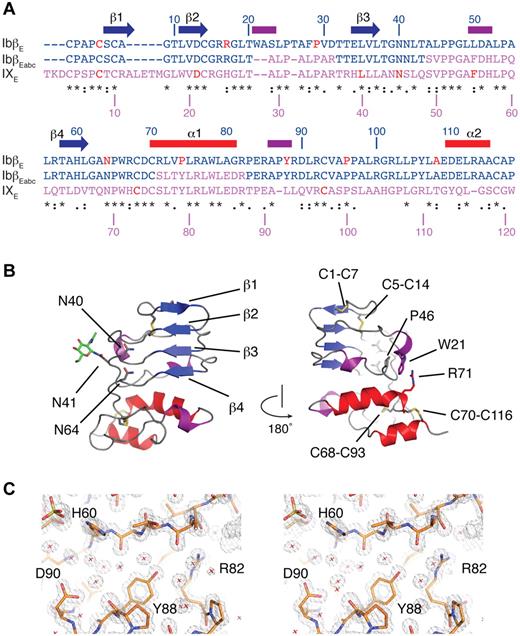

Crystal structure of GPIbβE

To explore the architecture of the GPIb-IX receptor complex we crystallized recombinant GPIbβE and solved the crystal structure to 1.25-Å resolution (Table 1). The topology of GPIbβE spanning residues 1-118 is shown in Figure 1B, showing the first structure with only a single LRR repeat. A typical example of the refined electron density is shown in stereo in Figure 1C and supplemental Video 1. As seen in other LRR proteins, GPIbβE assumes a right-handed coiled structure with a parallel β-sheet on one side (the concave face) and connecting loops containing β-turns and short 310 helices on the opposite (convex) face. The central LRR is covered on both ends by N- and C-terminal capping regions that contain several short α- and 310-helices. Four disulfide bonds are observed in the GPIbβE structure: 2 (Cys1-Cys7 and Cys5-Cys14) are located in the N-terminal cap and the other 2 (Cys68-Cys93 and Cys70-Cys116) in the C-terminal cap, which are topologically equivalent to those in the Nogo-66 and SLIT receptor.20,26 With only a single LRR it assumes a compact rectangular shape with a relatively flat, rather than a curved concave, face commonly observed in multi-LRR structures. Moreover, the single LRR accommodates a unique feature in GPIbβE that has not been observed in previously reported LRR structures; interactions of side chains bridging N- and C-terminal capping regions. Extending over the convex face, the aromatic ring in Trp21 is locked between the amino group of Pro46 and the guanidinium group of Arg71 by cation-π interactions (Figure 1B). These interactions exemplify numerous interloop interactions on the convex face, which probably add stability to the structure in a manner similar to the buried GPIbβ Asn residues, Asn40 and Asn64, on the concave face.27

Crystallographic data collection and refinement statistics

| Sample . | GPIbβE . | GPIbβEabc (form 1) . | GPIbβEabc (form 2) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection | |||

| Space group | P2(1) | P3(1)21 | C2(1) |

| Cell dimensions | |||

| a, b, c, Å | 61.60, 34.83, 71.77 | 72.01, 72.01, 171.73 | 124.27, 72.72, 72.57 |

| α, β, γ, degree | 90, 90.31, 90 | 90, 90, 120 | 90, 107.06, 90 |

| Resolution, Å* | 31.54-1.25 (1.28-1.25) | 42.17-2.35 (2.48-2.35) | 36.36-3.2 (3.82-3.20) |

| Rsym*† | 0.145 (0.400) | 0.131 (0.517) | 0.136 (0.630) |

| I/sigI* | 9.8 (3.8) | 14.4 (5.0) | 7.6 (1.9) |

| Completeness, %* | 93.4 (92.2) | 100.0 (100.0) | 95.2 (95.0) |

| Redundancy* | 4.6 (4.0) | 10.9 (11.1) | 2.4 (2.4) |

| Refinement | |||

| No. of reflections | 78 922 | 19 565 | 9796 |

| Rwork/Rfree‡ | 0.203/0.223 | 0.211/0.259 | 0.246/0.284 |

| B-factors, Å2 | |||

| Protein | 12.5 | 8.8 | 25.2 |

| Ligands | 21.0 | 39.3 | 61.3 |

| Solvent | 28.1 | 13.1 | 18.7 |

| Rms deviations | |||

| Bond lengths, Å | 0.0188 | 0.189 | 0.008 |

| Bond angles, degree | 1.889 | 1.301 | 1.435 |

| Sample . | GPIbβE . | GPIbβEabc (form 1) . | GPIbβEabc (form 2) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection | |||

| Space group | P2(1) | P3(1)21 | C2(1) |

| Cell dimensions | |||

| a, b, c, Å | 61.60, 34.83, 71.77 | 72.01, 72.01, 171.73 | 124.27, 72.72, 72.57 |

| α, β, γ, degree | 90, 90.31, 90 | 90, 90, 120 | 90, 107.06, 90 |

| Resolution, Å* | 31.54-1.25 (1.28-1.25) | 42.17-2.35 (2.48-2.35) | 36.36-3.2 (3.82-3.20) |

| Rsym*† | 0.145 (0.400) | 0.131 (0.517) | 0.136 (0.630) |

| I/sigI* | 9.8 (3.8) | 14.4 (5.0) | 7.6 (1.9) |

| Completeness, %* | 93.4 (92.2) | 100.0 (100.0) | 95.2 (95.0) |

| Redundancy* | 4.6 (4.0) | 10.9 (11.1) | 2.4 (2.4) |

| Refinement | |||

| No. of reflections | 78 922 | 19 565 | 9796 |

| Rwork/Rfree‡ | 0.203/0.223 | 0.211/0.259 | 0.246/0.284 |

| B-factors, Å2 | |||

| Protein | 12.5 | 8.8 | 25.2 |

| Ligands | 21.0 | 39.3 | 61.3 |

| Solvent | 28.1 | 13.1 | 18.7 |

| Rms deviations | |||

| Bond lengths, Å | 0.0188 | 0.189 | 0.008 |

| Bond angles, degree | 1.889 | 1.301 | 1.435 |

Values in parentheses are for highest-resolution shell.

Rsym = Sum(h) [Sum(j) [I(hj) − <Ih>]/Sum(hj) <Ih> where I is the observed intensity and < Ih > is the average intensity of multiple observations from symmetry-related reflections calculated with SCALA.

Rwork = Sum(h) ||Fo|h − |Fc|h|/Sum(h)|Fo|h, where Fo and Fc are the observed and calculated structure factors, respectively. Rfree was computed as in Rwork, but only for (5%) randomly selected reflections, which were omitted in refinement, calculated with REFMAC.

The crystal structure of GPIbβ ectodomain (GPIbβE). (A) Sequence alignment of GPIbβE (blue), GPIXE (purple), and GPIbβEabc (blue and purple) with respective residue numbers for GPIbβE and GPIX marked on the top and bottom. Elements of secondary structure in GPIbβE are shown on top and colored as in panel B. Residues affected by BSS missense mutations are in red. Three stretches of the GPIXE sequence that are included in GPIbβEabc are shown in purple. (B) Two orientations are shown of a ribbon diagram of the GPIbβE structure viewed from the concave face (left), with β-strands labeled in blue, α-helices in red, 310 helices in purple, and loop regions in gray. Asn residues 40, 41, and 64 are shown as stick, and a single residue from the N-linked oligosaccharide attached to Asn41 is also shown in green. The diagram on the right is rotated 180 degrees with side chains in the inter-LRR cap cation-π interaction shown as stick. (C) Refined 1.25-Å electron density, calculated with 2Fo-Fc coefficients and contoured at 1.5 rms.

The crystal structure of GPIbβ ectodomain (GPIbβE). (A) Sequence alignment of GPIbβE (blue), GPIXE (purple), and GPIbβEabc (blue and purple) with respective residue numbers for GPIbβE and GPIX marked on the top and bottom. Elements of secondary structure in GPIbβE are shown on top and colored as in panel B. Residues affected by BSS missense mutations are in red. Three stretches of the GPIXE sequence that are included in GPIbβEabc are shown in purple. (B) Two orientations are shown of a ribbon diagram of the GPIbβE structure viewed from the concave face (left), with β-strands labeled in blue, α-helices in red, 310 helices in purple, and loop regions in gray. Asn residues 40, 41, and 64 are shown as stick, and a single residue from the N-linked oligosaccharide attached to Asn41 is also shown in green. The diagram on the right is rotated 180 degrees with side chains in the inter-LRR cap cation-π interaction shown as stick. (C) Refined 1.25-Å electron density, calculated with 2Fo-Fc coefficients and contoured at 1.5 rms.

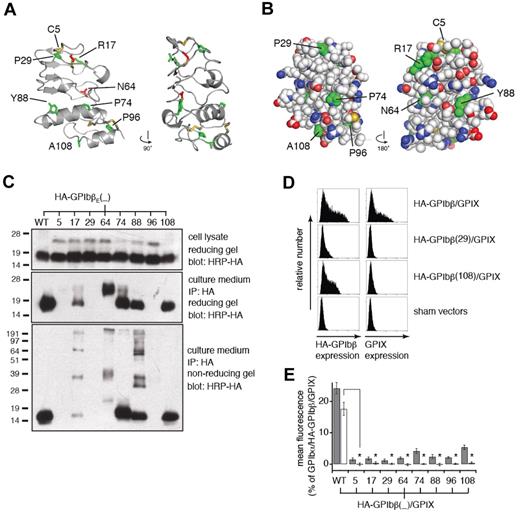

Different pathways in the pathogenesis of GPIbβ BSS mutations

Eight missense mutations in GPIbβE (C5Y,28 R17C,29 P29L,30 N64T,31 P74R,32 Y88C,33,34 P96S,35 and A108P34 ) have been identified in patients with BSS. We have examined the context of these 8 mutations with the use of the GPIbβE structure. Residues affected are shown in a ribbon diagram of the structure in Figure 2A and also in supplemental Video 2. Information on surface localization and conservation of each affected residue is summarized in supplemental Table 1. Cys5 and Cys14 form a disulfide bond. Substitution of Cys5 with a tyrosine would result in loss of the disulfide bond and leave an unpaired Cys14. Asn64 is fully buried in the structure and bridges the C-terminal cap and the LRR with 2 hydrogen bonds, both of which would be lost if substituted by a smaller Thr residue. The other GPbβE residues (Arg17, Pro29, Pro74, Tyr88, Pro96, and Ala108) are present on the protein surface, although Arg17, Tyr88, and Pro96 are partially buried by surrounding side chains (Figure 2B). Both R17C and Y88C would introduce an additional Cys residue to the domain, which will probably interfere with formation of the 4 native disulfide bonds. The other 4 mutations involve either removal or addition of a Pro residue, which can affect local conformation or global stability.

BSS mutations in GPIbβE disrupt expression and assembly of GPIb-IX complex by different mechanisms. (A) Two views of the GPIbβE structure are shown as a ribbon diagram related by a 90-degree rotation. Residues affected by BSS missense mutations are highlighted as stick and colored green for being solvent accessible and red for buried. (B) Space-filling representation of the GPIbβE structure, showing the concave (left) and convex (right) faces. Main chain atoms are colored white, and residues affected by BSS mutations are colored green. (C) SDS gels showing differential effects of BSS mutations on expression (top), secretion (middle), and folding (bottom) of GPIbβE expressed from transfected CHO cells. Each mutation is identified by the residue number. The HA epitope tag was appended to the N-terminal end of GPIbβE for easy detection. Immunoprecipitation was performed with anti-HA monoclonal Ab and immunoblotting with HRP-conjugated anti-HA monoclonal Ab (HRP-HA). Molecular weight markers are marked on the left of each gel. (D) Sample flow cytometric histograms showing the effects of selected BSS mutations on surface expression levels of HA-tagged full-length GPIbβ (HA-GPIbβ) and GPIX (GPIX) that are coexpressed transiently in CHO cells. (E) Relative surface expression levels of HA-GPIbβ (gray column) and GPIX (white column) in transfected CHO cells. The surface expression levels were measured by flow cytometry and quantified as mean fluorescence intensity, which were normalized with expression levels in cells transfected with wild-type GPIb-IX (GPIbα/HA-GPIbβ/GPIX) being 100% and those in cells transfected with sham vectors 0%.17 The data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). *P < .001.

BSS mutations in GPIbβE disrupt expression and assembly of GPIb-IX complex by different mechanisms. (A) Two views of the GPIbβE structure are shown as a ribbon diagram related by a 90-degree rotation. Residues affected by BSS missense mutations are highlighted as stick and colored green for being solvent accessible and red for buried. (B) Space-filling representation of the GPIbβE structure, showing the concave (left) and convex (right) faces. Main chain atoms are colored white, and residues affected by BSS mutations are colored green. (C) SDS gels showing differential effects of BSS mutations on expression (top), secretion (middle), and folding (bottom) of GPIbβE expressed from transfected CHO cells. Each mutation is identified by the residue number. The HA epitope tag was appended to the N-terminal end of GPIbβE for easy detection. Immunoprecipitation was performed with anti-HA monoclonal Ab and immunoblotting with HRP-conjugated anti-HA monoclonal Ab (HRP-HA). Molecular weight markers are marked on the left of each gel. (D) Sample flow cytometric histograms showing the effects of selected BSS mutations on surface expression levels of HA-tagged full-length GPIbβ (HA-GPIbβ) and GPIX (GPIX) that are coexpressed transiently in CHO cells. (E) Relative surface expression levels of HA-GPIbβ (gray column) and GPIX (white column) in transfected CHO cells. The surface expression levels were measured by flow cytometry and quantified as mean fluorescence intensity, which were normalized with expression levels in cells transfected with wild-type GPIb-IX (GPIbα/HA-GPIbβ/GPIX) being 100% and those in cells transfected with sham vectors 0%.17 The data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). *P < .001.

To elucidate the molecular pathogenesis of these BSS mutations, we have characterized systematically the mutational effects on GPIb-IX expression and assembly in transiently transfected CHO cells. Key parameters of transient transfection were kept constant to ensure proper comparison of protein expression levels among different experiments.17 CHO cells largely recapitulated the reported clinical observations that all 8 mutations led to a significant decrease in surface expression of the GPIb-IX complex, albeit to various degrees (supplemental Figure 2). To test whether these BSS mutations are detrimental to the structural integrity of GPIbβE, each mutation was introduced to the HA-tagged GPIbβE (with the native signal sequence), and the resulting gene was transfected transiently into CHO cells. Western blot analysis of the cell lysate indicated that translation of the HA-GPIbβE gene was not affected by any of the mutations (Figure 2C). However, C5Y, P29L, and P96S mutant proteins failed to secrete from the cells because no HA-tagged protein was detected in the culture media. The secretion of R17C was significantly decreased. In N64T-expressing cells, only the ectodomain with a higher molecular mass was detected in the culture media. The other mutants, P74R, Y88C, and A108P, were secreted similar to the wild type. Of the mutants that were secreted, R17C, N64T, and Y88C exhibited significant formation of intermolecular disulfide bonds as detected in SDS-PAGE under nonreducing conditions. Because GPIbβE contains 4 intramolecular disulfide bonds and no intermolecular ones (Figure 1B), the existence of the latter indicated misfolding of these mutant proteins. In contrast, P74R and A108P GPIbβE mutant proteins, like the wild-type, contained only intramolecular disulfide bonds and should therefore be well folded.

The effects of mutations on the interaction between GPIbβ and GPIX were analyzed next. GPIX does not express on the cell surface in isolation but becomes detectable when coexpressed with GPIbβ.14 GPIbβ is thought to interact with and stabilize GPIX, which involves the ectodomain and TM domain of both proteins.15,16 As shown in Figure 2D, when HA-tagged GPIbβ (HA-GPIbβ) and GPIX were cotransfected into CHO cells, both HA-GPIbβ and GPIX were detected on the cell surface. Mutations that disrupt secretion or folding of GPIbβE, such as P29L, resulted in little cell surface expression of HA-GPIbβ and, as a consequence, GPIX as detected by flow cytometry. By contrast, a distinctive feature of P74R and A108P was that HA-GPIbβ was present on the cell surface but GPIX was not. Overall, these results showed that BSS missense mutations disrupt assembly and surface expression of the GPIb-IX complex via different mechanisms.

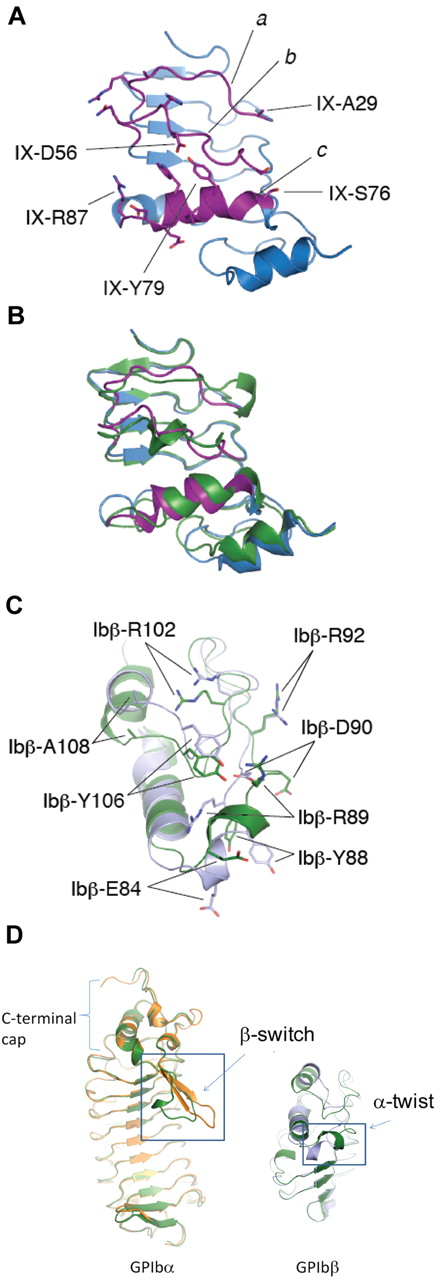

Crystal structure of GPIbβEabc and conformational change in the Tyr88 loop

Despite high sequence similarity between GPIbβE and GPIXE, attempts to express recombinant GPIXE have not been successful.16 However, sequence analysis did allow the engineering of GPIbβEabc, a chimera of GPIbβE and GPIXE, as a stable protein that is readily secreted.16 Built on the GPIbβE scaffold, GPIbβEabc incorporates 3 discontinuous stretches of GPIXE that correspond to the 3 convex loops, including the α1 helix (termed loops a, b, c; spanning GPIX residues Ala29-Arg36, Ser49-Gln60, and Ser76-Arg87 as shown in Figure 1A). GPIbβEabc was purified from insect cells and crystallized, and the structure was solved to 2.35-Å resolution, using the GPIbβE crystal structure for a molecular replacement calculation identifying 4 molecules in the asymmetric unit (Figure 3A; Table 1). To avoid confusion, residues of GPIbβEabc are labeled in this study by their residue numbers in respective source domains (eg, GPIX-Asp56 in loop b) rather than by GPIbβEabc's own.

The crystal structure of GPIbβEabc and its comparison with GPIbβE. (A) A ribbon diagram of the GPIbβEabc structure, showing the grafted GPIX convex loops (magenta) in front. Residues derived from GPIbβE are colored in blue. Side chains of several residues are shown in stick and labeled. GPIX-Ala29 and GPIX-Ser76 correspond to GPIbβ-Trp21 and GPIbβ-Arg71, respectively. (B) Superposition of GPIbβE (green) and GPIbβEabc (blue/magenta) structures. (C) A close-up view of the conformational difference in the C-terminal cap region between GPIbβE (green) and GPIbβEabc (blue) structures. The locations of several side chains in both structures are marked. (D) Topology diagrams of ligand-free (green) and ligand-bound structures in orange for GPIbα and blue for GPIbβ. The observed conformational change occurs in a topologically equivalent loop (boxed) and in each case involves unwinding of a helix for GPIbα (R-loop) and GPIbβ (loop containing residue Trp88) on engaging ligand; VWF-A1 or GPIX, respectively.

The crystal structure of GPIbβEabc and its comparison with GPIbβE. (A) A ribbon diagram of the GPIbβEabc structure, showing the grafted GPIX convex loops (magenta) in front. Residues derived from GPIbβE are colored in blue. Side chains of several residues are shown in stick and labeled. GPIX-Ala29 and GPIX-Ser76 correspond to GPIbβ-Trp21 and GPIbβ-Arg71, respectively. (B) Superposition of GPIbβE (green) and GPIbβEabc (blue/magenta) structures. (C) A close-up view of the conformational difference in the C-terminal cap region between GPIbβE (green) and GPIbβEabc (blue) structures. The locations of several side chains in both structures are marked. (D) Topology diagrams of ligand-free (green) and ligand-bound structures in orange for GPIbα and blue for GPIbβ. The observed conformational change occurs in a topologically equivalent loop (boxed) and in each case involves unwinding of a helix for GPIbα (R-loop) and GPIbβ (loop containing residue Trp88) on engaging ligand; VWF-A1 or GPIX, respectively.

The GPIbβEabc structure shares the same topology as GPIbβE, but it has 3 changes in the structure (Figure 3B). The first, as expected, is in the convex loops. Because of the substantial sequence difference, the 310 helix in loop a and the cation-π interloop interaction between Trp21 and Arg71 in GPIbβE are not present in the GPIbβEabc structure (Figure 3A). Second, in helix α1 of loop c GPIX-Tyr79 replaces GPIbβ-Pro74, which surprisingly does not affect the kinked main chain conformation but instead forms a substantial new interaction with loop b (Figure 3A). Here, the GPIX-Tyr79 side chain is buried under the main chain of GPIX-Gly53 and the Tyr OH group forms a hydrogen bond to the main chain nitrogen of adjacent GPIX-Phe55 (Figure 3A). The extensive interactions observed in these convex loops substantiate our earlier observation that only when all 3 convex loops are grafted together onto the GPIbβE scaffold did the GPIbβEabc chimeric protein become stable and well folded.16 A third difference occurs in the C-terminal cap, despite GPIbβE and GPIbβEabc sharing the same amino acid sequence in this region. Residues 86-89 that form the 310 helix in loop c of GPIbβE unravel, and residues 80-86 coil up to form a novel turn of helix in GPIbβEabc with GPIbβ-Glu84 forming a new salt bridge to GPIbβ-Arg57. In addition, the C-terminal helix α2 makes a rigid body movement of 3 Å away from helix α1. Compared with GPIbβE, the angle between helices α1 and α2 in GPIbβEabc is widened (Figure 3C).

The re-coiling conformational change in the loop containing residue Tyr88 is in a topologically equivalent region of the LRR fold to the β-switch loop in GPIbα known to alter conformation when binding to VWF-A1 domain or peptide inhibitor.6,36 In GPIbα the conformational change involves unraveling of a short α-helix to form an extended β-hairpin, whereas in GPIbβ the α-helix unravels and a second stretch is formed, displaced toward the C-terminus in a twisting helical motion (Figure 3D).

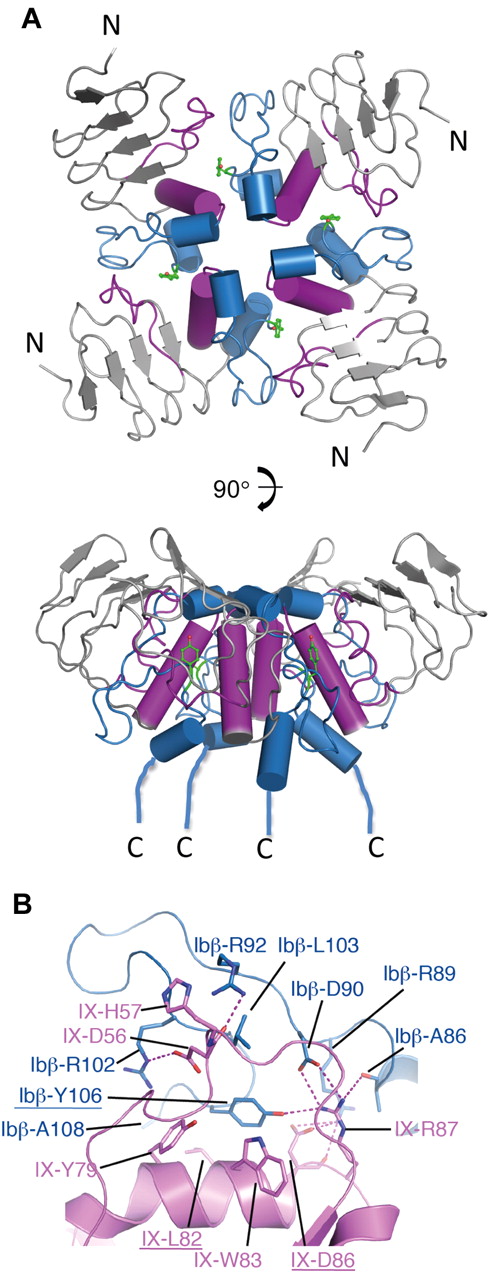

Tetrameric structure of GPIbβEabc shows a GPIbβ-GPIX interface

Previous studies with the GPIbβEabc construct have shown that the 3 loops (a, b, c) from GPIX form ectodomain interactions with GPIbβ and that this is required for surface expression of the GPIb-IX complex.16 The side chains from GPIbβ involved in this interaction with GPIX were unknown. In the crystal structure we observe 4 GPIbβEabc molecules in the asymmetric unit form a tetrameric ring structure. Here, the C-terminal cap region of one subunit packs against the convex loops (b, c) of another placing the α-helices toward the center of the ring where they are partially buried (Figure 4A). At this interface the side chain of GPIbβ-Tyr106 from one subunit lies at the center of a shallow pocket created between loop b and helix α1 (loop c) from a second subunit that is rotated by 90 degrees. Each interface buries a surface area of ∼ 1100 Å,2 which is significantly greater than values typical for crystal contacts37 or the contacts found in the GPIbβE structure. A second monoclinic crystal form (space group C21) of GPIbβEabc grown under different conditions has an identical structure and tetrameric arrangement (labeled form 2 in Table 1).

The tetramer structure of GPIbβEabc shows a binding interface between GPIbβE-derived C-terminal cap region and GPIXE-derived convex loops. (A) Cartoon diagram showing 2 views of the GPIbβEabc tetramer structure related by a 90-degree rotation. The N-termini (N) of the molecules are at the peripheral of the tetramer, and the C-termini (C) are all located in proximity at the bottom of the lower panel. Sequences derived from GPIbβE are colored in blue and those derived from GPIXE in magenta. The side chain of GPIbβ-Tyr106 at each interface is shown in green as stick. (B) A close-up view of the interface between 2 GPIbβEabc molecules (GPIbβE-derived residues in blue and GPIXE-derived residues in magenta). Interacting side chains are labeled and colored accordingly, and underlined residues were subject to mutagenesis.

The tetramer structure of GPIbβEabc shows a binding interface between GPIbβE-derived C-terminal cap region and GPIXE-derived convex loops. (A) Cartoon diagram showing 2 views of the GPIbβEabc tetramer structure related by a 90-degree rotation. The N-termini (N) of the molecules are at the peripheral of the tetramer, and the C-termini (C) are all located in proximity at the bottom of the lower panel. Sequences derived from GPIbβE are colored in blue and those derived from GPIXE in magenta. The side chain of GPIbβ-Tyr106 at each interface is shown in green as stick. (B) A close-up view of the interface between 2 GPIbβEabc molecules (GPIbβE-derived residues in blue and GPIXE-derived residues in magenta). Interacting side chains are labeled and colored accordingly, and underlined residues were subject to mutagenesis.

Figure 4B shows hydrophobic contacts contribute to the GPIX pocket, including GPIX-Tyr79, GPIX-Leu82, and GPIX-Trp83, and more peripheral contacts to the interface come from GPIbβ-Ala108 and GPIX-His57. The OH group of GPIbβ-Tyr106 forms a hydrogen bond to the guanidinium of GPIX-Arg87. GPIbβ-Tyr106 is further surrounded by 3 salt bridges between GPIbβ residues Arg102, Asp90, and Arg89 and GPIX residues Asp56, Arg87, and Asp86, respectively. GPIbβ-Arg92 and GPIX-Arg87 side chains form hydrogen bonds to the main chain carbonyls GPIX-Asp56 and GPIbβ-Ala86, respectively.

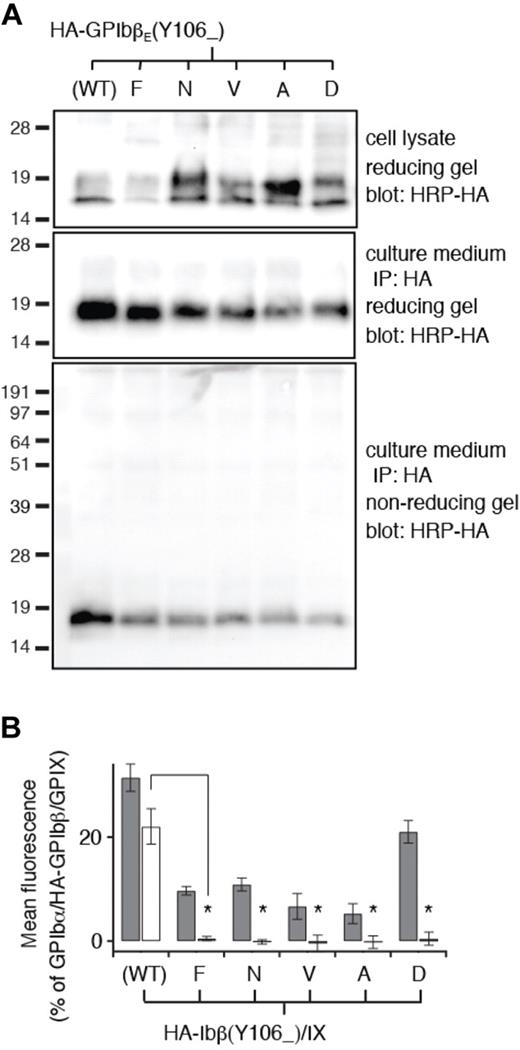

The interface between GPIbβEabc molecules is composed of the GPIbβE-derived C-terminal region and GPIXE-derived convex loops. To test whether this interface is a valid representation of full-length GPIbβ and GPIX in the whole complex, 3 residues were selected for mutagenesis. GPIbβ-Tyr106 lies at the center of the interface, and GPIX-Leu82 and GPIX-Asp86 are examples of residues that contribute hydrophobic and electrostatic contacts to the interface, respectively (shown as underlined in Figure 4B). In the GPIbβE crystal structure, the side chain of Tyr106 is exposed to the solvent and flanked by Arg85 and Arg89. Mutating Tyr106 to Phe, Asn, Asp, Ala, or Val largely preserved proper secretion and folding of HA-GPIbβE that were expressed transiently from CHO cells (Figure 5A). However, when expressed as a full-length subunit on the surface of cells, all Tyr106 mutations resulted in the loss of the ability of HA-GPIbβ to enhance surface expression of GPIX in transfected CHO cells (Figure 5B). Thus, as predicted by the GPIbβEabc crystal structure, these results pinpoint GPIbβ-Tyr106 as a critical part of a GPIXE binding site.

Tyr106 mutations do not disrupt secretion and folding of GPIbβE but disrupt its interaction with GPIXE. (A) SDS gels showing the lack of disruptive effects of Tyr106 mutations on expression, secretion, and folding of GPIbβE expressed from transfected CHO cells. The identity of each Tyr106 mutation is marked on top of the gels. The other annotations follow those of Figure 2C. (B) Relative surface expression levels of HA-GPIbβ (gray column) and GPIX (white column) in transfected CHO cells measured by flow cytometry. The annotations follow those of Figure 2E. Note that none of the Tyr106 mutations retain the ability of wild-type HA-GPIbβ to enhance surface expression of GPIX. The data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). *P < .001.

Tyr106 mutations do not disrupt secretion and folding of GPIbβE but disrupt its interaction with GPIXE. (A) SDS gels showing the lack of disruptive effects of Tyr106 mutations on expression, secretion, and folding of GPIbβE expressed from transfected CHO cells. The identity of each Tyr106 mutation is marked on top of the gels. The other annotations follow those of Figure 2C. (B) Relative surface expression levels of HA-GPIbβ (gray column) and GPIX (white column) in transfected CHO cells measured by flow cytometry. The annotations follow those of Figure 2E. Note that none of the Tyr106 mutations retain the ability of wild-type HA-GPIbβ to enhance surface expression of GPIX. The data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). *P < .001.

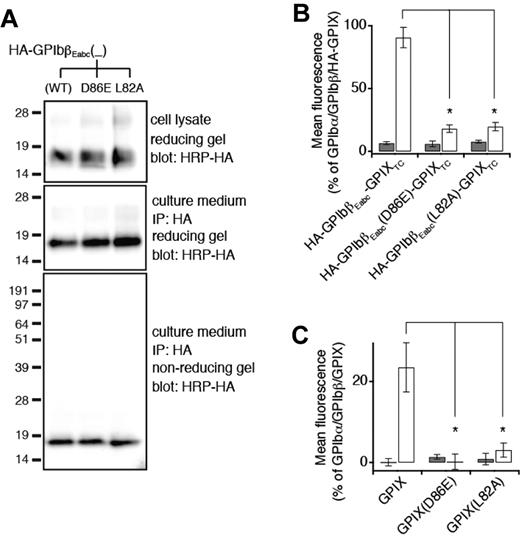

Similarly, HA-GPIbβEabc protein containing a GPIX-L82A or GPIX-D86E mutation was able to secrete to the culture media and fold well (Figure 6A). However, both mutations failed to retain the GPIbβ-binding ability of GPIbβEabc in the context of the full-length subunit (Figure 6B). Because GPIXE alone cannot express as a well-folded form,16 it would be difficult to assess the effect of either mutation on its folding and secretion. Nonetheless, full-length GPIX bearing either mutation could not be expressed on the cell surface even in the presence of GPIbβ (Figure 6C), which is consistent with the GPIbβEabc crystal structure that both GPIX-Leu82 and GPIX-Asp86 participate directly in the interaction between GPIbβE and GPIXE.

GPIXE convex loops participate in direct interaction with GPIbβE in the full-length complex. (A) SDS gels showing the lack of disruptive effects of the L82A or D86E mutation on expression, secretion, and folding of HA-GPIbβEabc. Residue numbers of both mutations are in the context of GPIX. The other annotations follow those of Figure 2C. (B) Relative surface expression levels of HA-GPIbβEabc-GPIXTC, either wild-type or containing the indicated mutation, in the absence (gray column) or presence (white column) of coexpressing GPIbβ in transfected CHO cells. HA-GPIbβEabc-GPIXTC is a protein that contains N-terminally HA-tagged GPIbβEabc and GPIX TM and cytoplasmic domains.16 The expression level was measured by flow cytometry with the use of anti-HA mAb and quantified as mean fluorescence intensity, which was normalized with that in cells transfected with wild-type GPIb-IX (GPIbα/GPIbβ/HA-GPIX) being 100% and those in cells transfected with sham vectors 0%.16 Note that the enhancement of HA-GPIbβEabc-GPIXTC surface expression by GPIbβ is significantly diminished by both mutations. The data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 4). *P < .01. (C) Relative surface expression levels of GPIX, either wild-type or containing the indicated mutation, in the absence (gray column) or presence (white column) of coexpressing GPIbβ in transfected CHO cells. GPIX surface expression level was measured by flow cytometry with the use of anti-GPIX mAb FMC25 and analyzed as described above (n = 3).

GPIXE convex loops participate in direct interaction with GPIbβE in the full-length complex. (A) SDS gels showing the lack of disruptive effects of the L82A or D86E mutation on expression, secretion, and folding of HA-GPIbβEabc. Residue numbers of both mutations are in the context of GPIX. The other annotations follow those of Figure 2C. (B) Relative surface expression levels of HA-GPIbβEabc-GPIXTC, either wild-type or containing the indicated mutation, in the absence (gray column) or presence (white column) of coexpressing GPIbβ in transfected CHO cells. HA-GPIbβEabc-GPIXTC is a protein that contains N-terminally HA-tagged GPIbβEabc and GPIX TM and cytoplasmic domains.16 The expression level was measured by flow cytometry with the use of anti-HA mAb and quantified as mean fluorescence intensity, which was normalized with that in cells transfected with wild-type GPIb-IX (GPIbα/GPIbβ/HA-GPIX) being 100% and those in cells transfected with sham vectors 0%.16 Note that the enhancement of HA-GPIbβEabc-GPIXTC surface expression by GPIbβ is significantly diminished by both mutations. The data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 4). *P < .01. (C) Relative surface expression levels of GPIX, either wild-type or containing the indicated mutation, in the absence (gray column) or presence (white column) of coexpressing GPIbβ in transfected CHO cells. GPIX surface expression level was measured by flow cytometry with the use of anti-GPIX mAb FMC25 and analyzed as described above (n = 3).

Discussion

One of the fundamental but unanswered questions about the GPIb-IX complex is how the subunits organize and assemble. Earlier studies have shown that TM helices of the GPIb-IX complex interact with one another to form a parallel tetrameric α-helical bundle.4,18,19 The GPIX TM helix bridges the 2 GPIbβ TM helices, and GPIbα performs a similar function providing noncovalent and covalent quaternary interactions and stability by formation of the 2 interchain disulfide bonds bridging 2 GPIbβs. Previously, it has also been shown that the LRR-containing ectodomains form an interface involving the convex loops of GPIX interacting with GPIbβ.16 Overall protein-protein interactions mediated by LRR domains use a diverse range of scaffolds with different numbers of LRRs (ranging from 1 to > 15) mediating homotypic and heterotypic interactions.5 These interactions are principally mediated by the LRR concave face that typically has a curved or horseshoe shape as observed in GPIbα.6 GPIbβ and GPIX are unusual in that they have only a single LRR. The GPIbβE structure is the first description of this fold and shows a compact shape with little LRR curvature.

A crystal structure for the SLIT receptor LRR ectodomain domain 4 (pdb code 2WFH) shows a homodimer with a concave face-to-face interaction of the LRRs. We initially speculated that the 2 copies of GPIbβE may also interact in a similar way to form a dimer; however, in the crystal structure we only observe a monomer. By contrast the structure of a chimeric GPIbβEabc, where 3 loops from GPIX are added, shows a heterodimeric GPIbβ-GPIX interface. Because of the positioning of the 2 subunits in the dimer at right angles, this structure is then able to cyclize with a second dimer to form a ringlike tetramer where the same interface is observed 4 times. Rather than using the LRR concave face, this structure shows that interactions occur through the C-terminal cap of GPIbβE and convex face loops of GPIXE. Here, a central side chain Tyr106 from the GPIbβE cap inserts into a pocket created by 2 loops from GPIX on the convex face. This is more familiar to the interfaces observed in Toll-like receptors in which heterodimeric interactions form between the C-terminal cap and one side of the LRRs.38

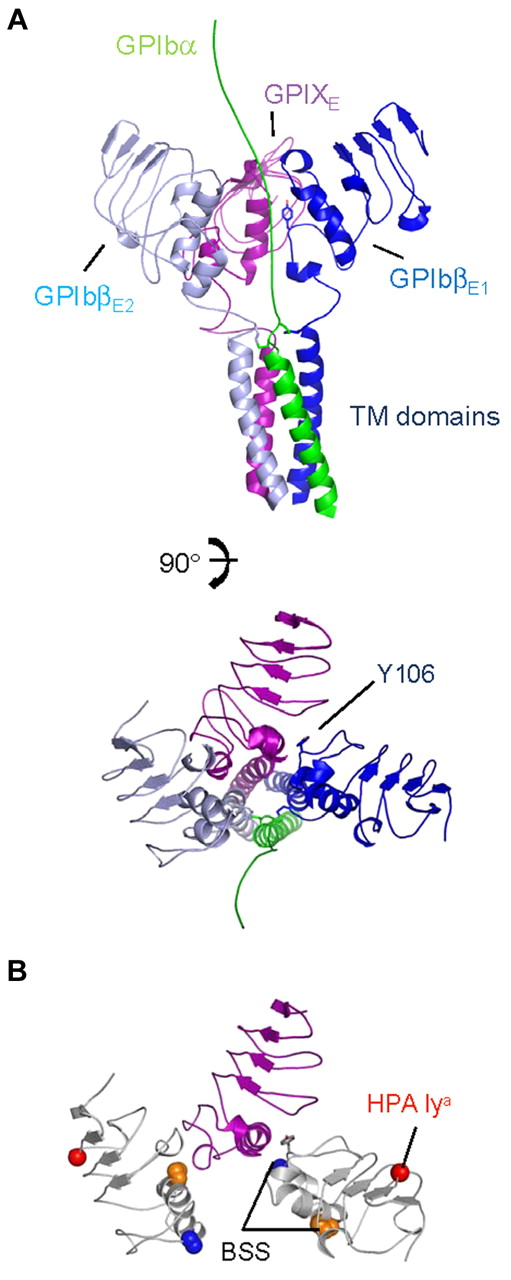

An important spatial constraint for the GPIb-IX complex lies in the uniform topology of its subunits. Because GPIbα, GPIbβ, and GPIX are all type I TM proteins, the C-termini of all 4 ectodomains in the GPIb-IX complex should remain in close proximity to one another to enable formation of the adjacent parallel TM helix bundle. We noticed that in the GPIbβEabc crystal structure, the C-termini of all 4 GPIbβEabc molecules are located on the same side of the tetramer (Figure 4A; supplemental Video 3). If the GPIbβ1-GPIX-GPIbβ2 trimer has a similar cyclic arrangement positioned above the TM helices, then a schematic model of this trimer is shown in Figure 7A with the GPIbα TM helix added (shown in green) extending toward the N-terminal ligand binding domain. A second observation from the GPIbβEabc structure is that GPIX can only bind one GPIbβE through its b,c loop pocket; thus, further studies will be required to define what the context and conformation of a second GPIbβE (GPIbβE2) is. Because we observe no interaction between 2 GPIbβE molecules in the crystal structure, the model in Figure 7A shows GPIbβE2 on the opposite side of GPIX to GPIbβE1.

A schematic model for the membrane-proximal portion of the GPIb-IX complex. (A) Cartoon diagrams related by a 90-degree rotation showing the GPIbα chain TM domain (in green) extending toward the N-terminus (top), GPIbβ ectodomain and TM domain (in sky blue and dark blue), and GPIX ectodomain and TM domain (in purple). Tyr106 from GPIbβ1 is shown as stick along with interchain disulphides. (B) Same view as panel A, except without TM domains. GPIbβ is colored white, showing residues affected by BSS and human platelet-specific alloantigen (HPA) mutations. Side chains of GPIbβ residues Ala108 (blue), Pro74 (orange), and Gly15 (red) are shown in space-filling mode; Tyr106 is shown as stick (gray).

A schematic model for the membrane-proximal portion of the GPIb-IX complex. (A) Cartoon diagrams related by a 90-degree rotation showing the GPIbα chain TM domain (in green) extending toward the N-terminus (top), GPIbβ ectodomain and TM domain (in sky blue and dark blue), and GPIX ectodomain and TM domain (in purple). Tyr106 from GPIbβ1 is shown as stick along with interchain disulphides. (B) Same view as panel A, except without TM domains. GPIbβ is colored white, showing residues affected by BSS and human platelet-specific alloantigen (HPA) mutations. Side chains of GPIbβ residues Ala108 (blue), Pro74 (orange), and Gly15 (red) are shown in space-filling mode; Tyr106 is shown as stick (gray).

Different pathways to BSS

The genetic basis for BSS was established 3 decades ago.11 More than 30 mutations have since been identified from patients with BSS, and the number will probably grow.39 As we showed in this study, several novel mutations could produce BSS-like phenotypes in transfected cells (Figures 5–6). Some BSS mutations are located in the promoter region and are presumed to decrease gene transcription.40 Some are frameshifting or nonsense mutations, resulting in a typically truncated and nonfunctional protein product.41-43 In this study, we have for the first time systematically characterized all the reported missense BSS mutations in GPIbβ and observed distinct mechanisms that underlie the pathogenesis of the disease (Figure 2). Six of the 8 missense mutations are detrimental to proper tertiary folding or secretion of GPIbβE. However, the other 2 mutations A108P and P74R maintain the native disulphide bonds and probably fold normally.

The clinical data on the A108P mutation describe a patient who is compound heterozygous with mutation Y88C.34 In these platelets GPIb-IX receptor complex is present on the surface at a reduced level and does bind VWF. Antibody SZ1 (binds GPIbβ/GPIX subunits in complex but not in isolation) recognizes the GPIb-IX present. As a compound heterozygote of GPIbβ, the mutations could form different combinations of the chains, that is, A108P/A108P, A108P/Y88C, and Y88C/Y88C. A separate family that is homozygous for Y88C has classic BSS giant platelets with no receptor present at the platelet surface.33 As shown in Figure 4B, Ala108 is adjacent to Tyr106 which is central to the GPIbβEabc interface. We showed mutating Tyr106 abolishes GPIX expression in the same way as A108P. Mutating Ala108 to Pro at the periphery of the interface may produce a less-stable subunit association that, in turn, gives rise to the reduction in surface expression of the whole complex, which is what we observe in CHO cells. The P74R mutation shows classic BBS platelets in homozygous patients with no receptor complex detected at the surface.32 This mutation is more severe than A108P in our cell-based assays and does not support any GPIX expression at the cell surface even in the presence of GPIbα (supplemental Figure 2). Pro74 does not contribute directly to the Tyr106 interface but is located close by in helix α1, which does contribute through side chains from residues Ala86, Arg89, and Asp90 (Figure 4B). Proline residues are commonly found at the N-termini of helices where the special main chain properties influence the secondary structure formation. A change here could disrupt the orientation of the helix and thus its contributions to the interface.

Finally, not all mutations characterized in GPIbβ result in loss or reduction of receptor complex at the platelet surface. The polymorphism G15E is associated with the human platelet-specific alloantigen Iya and does not adversely affect the expression level of GPIb-IX.44 Gly15 is exposed on the protein surface and located in the N-terminal cap. Figure 7B shows the locality of these mutations in the same model as Figure 7A and shows how 2 copies of GPIbβ in this arrangement present mutations in different contexts (supplemental Video 4). Overall these studies provide valuable insights on the assembly of GPIb-IX complex and will prove a scaffold for further investigation of this important platelet receptor.

An Inside Blood analysis of this article appears at the front of this issue.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility for provision of synchrotron radiation source and thank David Flot and Gordon Leonard for assistance in using the beamline ID23-2.

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (grant HL082808, R.L.) and Cancer Research UK (grant C21418/A8573), British Heart Foundation (grant RG/07/002/23 132, J.E.).

Coordinates and structure factors deposited with the Protein Data Bank are 3RFE for GPIbβE and 3REZ for GPIbβEabc.

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: P.A.M. and K.H.C. crystallized and determined the structures of GPIbβE and GPIbβEabc, respectively; W.Y. produced recombinant proteins for crystallization, characterized and analyzed mutational effects on GPIb-IX expression and assembly, and wrote the paper; X.M. and X.Z. cloned many constructs and established the baculovirus protein expression system; R.L. initiated and designed research, analyzed results, and wrote the paper; and J.E. analyzed results and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation for R.L. is Division of Hematology, Oncology, and Bone Marrow Transplant, Department of Pediatrics, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA.

Correspondence: Jonas Emsley, Centre for Biomolecular Sciences, School of Pharmacy, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, NG7 2RD, United Kingdom; e-mail: jonas.emsley@nottingham.ac.uk; and Renhao Li, Division of Hem/Onc/BMT, Department of Pediatrics, Emory University School of Medicine, 2015 Uppergate Dr, Rm 464, Atlanta, GA 30322; e-mail: renhao.li@emory.edu.

References

Author notes

P.A.M., W.Y., and K.H.C. contributed equally to this study.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal