Women survive many acute infections better than men. In this issue of Blood, Scotland et al demonstrate that sex differences in tissue resident immune cells make female innate immunity more efficient at dealing with streptococcal infection.1

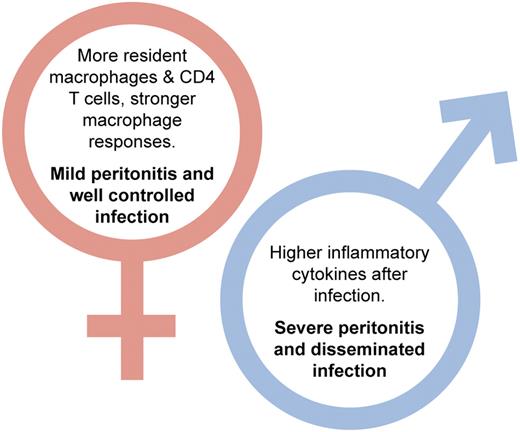

Differences between male and female responses to streptococcal peritonitis reported in Scotland et al.1 Professional illustration by Kenneth X. Probst.

Differences between male and female responses to streptococcal peritonitis reported in Scotland et al.1 Professional illustration by Kenneth X. Probst.

In an ideal host response to infection the innate immune system would inactivate and clear pathogen with the minimum of tissue-damaging inflammation. Given the myriad ways in which pathogens have developed strategies for avoiding innate immune responses this does not always happen. Second best is that the innate response controls local infection with minimum inflammation until the acquired response kicks in to clear it. The degree of inflammation and the efficiency of pathogen clearance accompanying acute innate responses primarily depend on activation of tissue-resident macrophages via pathogen recognition receptors such as the Toll-like receptors.

Sex differences in immunity have been widely recognized for many years,2,3 but the underlying mechanisms have not been well understood. Sex steroid hormones have been shown to have a role,4 and in the 1960s estrogen was shown to have effects on macrophage behavior.5 However, it was recently demonstrated in a large cohort of patients suffering severe trauma that both pre- and postmenopausal women have reduced incidence of nosocomial infection.6 This indicates that ovarian hormones do not account for all the differences between male and female responses to infection. The article by Scotland et al demonstrates that female mice and rats have tissue cytokine–dependent higher numbers of mononuclear leukocytes in both the pleural and peritoneal cavities.1

They further show that female macrophages have increased phagocytic capacity. Translating these results in vivo in a model of streptococcal peritonitis, they demonstrate that female mice showed fewer signs of disease with less proinflammatory cytokine secretion, reduced local neutrophil recruitment, and lower disseminated infection. This is despite having increased macrophage cell-surface TLR2 and TLR4. Critically, their paper shows levels of resident T cells are twice as high in females than in males. Of these resident T cells, the CD4+ cells limit proinflammatory cytokine production by macrophages but do not affect their phagocytic capacity (see figure). Using ovariectomy as a model of menopause, the authors show that this only induced a partial transition to a more “male” immune response. Numbers of resident macrophages decreased as did their phagocytic activity and levels of TLR2 and TLR4 but critically numbers of T cells were not affected by ovariectomy. In the streptococcal peritonitis model, ovariectomised animals still did better than male mice. As Scotland and colleagues point out, this has implications for treatment and strengthens the case for the development of sex-specific therapies.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests. ■

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal