Abstract

Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) is increased in the lungs of patients with pulmonary fibrosis, and animal studies have shown that experimental manipulations of PAI-1 levels directly influence the extent of scarring that follows lung injury. PAI-1 has 2 known properties that could potentiate fibrosis, namely an antiprotease activity that inhibits the generation of plasmin, and a vitronectin-binding function that interferes with cell adhesion to this extracellular matrix protein. To determine the relative importance of each PAI-1 function in lung fibrogenesis, we administered mutant PAI-1 proteins that possessed either intact antiprotease or vitronectin-binding activity to bleomycin-injured mice genetically deficient in PAI-1. We found that the vitronectin-binding capacity of PAI-1 was the primary determinant required for its ability to exacerbate lung scarring induced by intratracheal bleomycin administration. The critical role of the vitronectin-binding function of PAI-1 in fibrosis was confirmed in the bleomycin model using mice genetically modified to express the mutant PAI-1 proteins. We conclude that the vitronectin-binding function of PAI-1 is necessary and sufficient in its ability to exacerbate fibrotic processes in the lung.

Introduction

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a common interstitial lung disease that is associated with an insidious progression of shortness of breath and cough. Unfortunately, no treatment definitively modulates the severe course of this disorder and 60%-70% of individuals afflicted with IPF will die within 5 years of their diagnosis.1,2 Therefore, it is imperative that we better understand the pathogenic mechanisms underlying fibrosis of the lung to define new treatment strategies.

Perturbations of the plasminogen activator pathway are common in conditions associated with pulmonary fibrosis. Specifically, the expression of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) relative to the plasminogen activators is increased in both human fibrotic disorders and in the bleomycin model of pulmonary fibrosis.3 A causal relationship between PAI-1 and the extent of scarring following lung injury has been demonstrated conclusively in animal studies.4-6 However, the mechanism by which PAI-1 exacerbates this collagen accumulation remains unclear. PAI-1 possesses 2 distinct functions that could (alone or in combination) potentially mediate its profibrotic effects: (1) an antiprotease activity that inhibits the generation of plasmin, and (2) a vitronectin-binding function that interferes with cell adhesion to this extracellular matrix protein.7 By impeding the activation of plasminogen to plasmin, PAI-1's antiprotease activity could limit timely removal of provisional matrix molecules, for example, fibrin or fibronectin,5,8-11 or reduce plasmin-mediated activation of matrix metalloproteinases that are capable of degrading multiple matrix proteins including collagen.12,13 Excess PAI-1 can also limit plasmin-mediated activation of anti-fibrotic growth factors such as hepatocyte growth factor.14-18

The binding of PAI-1 to the provisional matrix protein vitronectin could also be important in the pathogenesis of fibrosis. When bound to vitronectin, the antiprotease activity of PAI-1 is significantly stabilized.7 As mentioned, the binding of PAI-1 to vitronectin also impedes cell attachment to this matrix molecule.19 Our laboratory demonstrated that PAI-1, through its vitronectin-binding function, significantly delayed in vitro alveolar epithelial wound closure, a process that may be important to limit collagen accumulation afterlung injury.20 The vitronectin-binding function of PAI-1 might also induce a profibrotic phenotype in mesenchymal cells and induce EMT in epithelial cells by modulating their interaction with the extracellular matrix.6,21,22

To better understand the mechanisms by which PAI-1 exacerbates pulmonary fibrosis, we used 2 experimental approaches to independently alter the antiprotease and vitronectin properties of PAI-1 in an in vivo model of pulmonary fibrosis. The results of these studies show that the vitronectin binding property of PAI-1 is critical in its ability to exacerbate lung scarring.

Methods

Animals

All animal experiments were performed in accordance with institutional guidelines set forth by the University Committee on the Use and Care of Animals (UCUCA) and were approved by the University of Michigan ACUC. Mice were housed in a specific pathogen-free environment at a constant temperature and a 12:12 hour light-dark cycle. Animals had free access to food and water. Mice transgenically deficient in PAI-1 (PAI-1−/−) were originally generated by Dr Peter Carmeliet (University of Leuven, Belgium) and have been backcrossed with C57BL/6 mice for at least 8 generations.23 Wild-type (WT) C57BL/6 mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory.

PAI-1 mutant proteins

All PAI-1 mutant proteins were base on human PAI-1 and were constructed and isolated as described in collaboration with Molecular Innovations.24 PAI-1(V+P+), also designated as PAI-114-1b, retains both antiprotease and vitronectin binding properties and contains 4 amino acid substitutions (N150H, K154T, Q319L and M354I) that delay its spontaneous conversion to the inactive, latent form by 75-fold compared with wild-type human PAI-1 (half-life of 145 hours at 37°C).25 PAI-1(V-P+), also designated PAI-1AK, contains the same 4 stabilizing mutations present in PAI-114-1b along with 2 additional mutations (Arg101→Ala and Lys123→Glu). These alterations completely abolish PAI-1's ability to bind to vitronectin, but do not affect its antiprotease activity.26 Finally, PAI-1(V+P-), also designated PAI-1RR, contains a 2 amino acid substitutions (Thr333→Arg and Ala335→Arg) within the reactive center loop. These mutations do not influence PAI-1's vitronectin-binding capability but completely block its antiprotease activity.24 The amino acid changes in PAI-1RR also resulted in an extended half-life compared with native PAI-1 with this mutant showing no measurable conversion to the latent form.

PAI-1 mutant expressing mice

Mutant PAI-1 expressing mice were a generous gift from Dr Doug Vaughan (Northwestern University).27 These mice express mutant human PAI-1 proteins off of the preproendothelin promoter. PAI-1(V+P+) mice express a protein with the same 4 amino acid substitutions described above that delay its spontaneous conversion to the latent form. PAI-1(V+P-) mice express a protein that possesses these same stabilizing mutations but also contains an additional reactive center loop amino acid substitution (R346A). This latter mutation impairs PAI-1's ability to inhibit plasminogen activation but has no effect on vitronectin-binding. PAI-1(V-P+) mice express a protein that contains the stabilizing mutations and possesses an additional substitution (Q123K) that decreases PAI-1's affinity for vitronectin nearly 300-fold. This alteration does not alter PAI-1's antiprotease activity. These 3 separate PAI-1 mutant expressing murine lines were bred into a PAI-1 deficient background and then backcrossed for at least 7 generations with C57BL/6 mice.

Bleomycin treatment

Weight- and age-matched (18-22 g at 6-8 weeks of age) PAI-1−/−, WT, and PAI-1 mutant transgenic mice were intratracheally administered bleomycin (1.15 u/kg in 50 μL of sterile PBS) as previously described.5

PAI-1 mutant protein dosing regimen

Bleomycin-treated PAI-1−/− mice were intraperitoneally administered PAI-1 mutant proteins beginning at day 8 postinjury. This time point was chosen to correspond with the beginning of the fibroproliferative phase of the bleomycin model. Based on previous studies, the PAI-1 mutant proteins were injected at a dose of 100 μg in 100 μL of PBS every 12 hours until euthanasia.28 Plasma and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid were collected 60 minutes after the injected dose of each mutant on day 9 postbleomycin.

Bronchoalveolar lavage

Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid was collected by instilling 1.0 mL of sterile PBS into the trachea. The aliquot was allowed to dwell for 10 seconds before aspiration. Recovery of the fluid was consistently 70%-80% of the total. The recovered fluid was centrifuged at 4000g for 10 minutes, and the supernatant was immediately stored at −80°C.

BAL fluid and plasma PAI-1 concentration measurements

Endogenous murine and human mutant PAI-1 concentrations were measured in plasma and BAL fluid using a carboxylated microsphere-based ELISA (Luminex). Briefly, 50 μg of protein was coupled to SeroMAP beads (Luminex) using a carbodiimide coupling protocol (Luminex). Murine anti–rodent PAI-1 (Molecular Innovations) was used as the capture antibody for total murine PAI-1. Rabbit anti–human PAI-1 (Molecular Innovations) was used as the capture antibody for the total concentration of the PAI-1 mutants. To measure active PAI-1 concentrations in WT and PAI-1−/− samples, human uPA was used for capture. The concentration of PAI-1 in each sample was calculated using specific standard curves generated with murine PAI-1 or the mutant PAI-1 proteins. The assay was performed by adding 10 μL of standards or samples to a 96 well filter plate (Millipore). Each well then received 2500 beads in 25 μL of PBS-1%BSA, and the wells were incubated overnight in the dark at 4°C. After washing, 25 μL of 4 μg/mL biotin-labeled rabbit anti–mouse PAI-1 or rabbit anti–human PAI-1 (Molecular Innovations) were added to the beads, and the plate was incubated with continuous shaking in the dark at room temperature for 1 hour. Twenty-five microliters of 10 μg/mL streptavidin-R-phycoerythrin (Molecular Probes) was added to each well and the mixture was incubated in the dark with continuous agitation at room temperature for 30 minutes. Finally, the beads were washed, and 100 μL of sheath fluid were added for 5-10 minutes. The plate was read with the Luminex (median setting, 50 μL sample size, 50 events/bead). Mean fluorescence intensities of unknown samples were converted to pg/mL based on the standard curves using a 5-parameter regression formula (Masterplex QT Version 4.0; Miraibio).

Vitronectin plasma concentration

Murine plasma vitronectin levels were measured by ELISA (Molecular Innovations) following the manufacturer's protocol. Plasma samples were diluted to 1:500.

BAL fluid fibrinolytic activity

Fibrinolytic activity of BAL fluid was measured by a clot lysis assay as previously described.29 The rate of fibrinolysis recorded as the t½ which represented the number of minutes required for 50% of turbidity to be lost. For samples with minimal or no plasminogen activator activity, the absorbance never returned to baseline and thus the t½ could not be determined. For these samples, a t½ value of 660 minutes was which represents the duration of the assay.

Hydroxyproline assay

Hydroxyproline content of the lungs was measured using the technique of Woessner and colleagues with modifications as recently described.30 Because results were pooled from different studies, the hydroxyproline from the experimental mice were normalized to bleomycin treated wild-type mice using the following formula: (Hydroxyprolineexperimental – Hydroxyprolinebasal/HydroxyprolineWT – Hydroxyprolinebasal) × 100. Hydroxyprolineexperimental represents the lung collagen for each experimental animal whereas Hydroxyprolinebasal is the mean lung collagen from the untreated WT control animals and HydroxyprolineWT is the mean lung collagen from the bleomycin treated WT group.

Lung histology

The left lungs of bleomycin-treated WT and PAI-1−/− mice were inflation-fixed at 25 cm H2O pressure with 10% neutral-buffered formalin, removed en bloc, further fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin overnight, and then paraffin embedded. Five micron sections were stained using the Masson trichrome method and immunohistochemistry. To detect α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), sections were stained with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-smooth muscle actin antibody (Sigma-Aldrich) using a protocol adapted from Cattoretti and colleagues.31 Lung sections were developed using Vector Red Alkaline Phosphatase Substrate Kit I (Vector Laboratories) and counterstained with Mayer Hematoxylin (Thermo Scientific) before mounting. To detect the macrophage antigen F4/80, sections were stained with an anti-F4/80 antibody (eBioscience) followed by a biotinylated mouse adsorbed anti–rat IgG and avidin D horseradish peroxidase (Vector Laboratories). Sections were then developed using the Vector AEC kit.

Statistical analysis

The data are presented as means ± SEM. Statistics were performed using GraphPad Prism software. With the exception of the analysis of lavage fluid fibrinolytic activity, mean values from the different groups were compared using 1-way ANOVA with post hoc pairwise comparisons using the Newman-Kuels Multiple Comparison Test. For the lavage fluid fibrinolytic activity, the mean values of the different groups were compared using the Kruskal-Wallis test with post hoc group comparison using the Dunn Multiple Comparison Test.

Results

Plasma and BAL fluid PAI-1 concentrations

To generate a mouse model with PAI-1 activity limited to either the antiprotease or vitronectin-binding function, we administered mutant proteins to PAI-1−/− mice. Our goal was to approximate the levels of PAI-1 seen in the alveolar compartment of WT animals after bleomycin injury. To accomplish this, we first measured the plasma and BAL levels of PAI-1 in WT mice before bleomycin instillation and on days 9 and 19 posttreatment. The mean plasma level of total PAI-1 ranged between 25-80 pg/mL over the 3 time points with no induction by bleomycin administration (Figure 1A). Less than 50% of the plasma PAI-1 retained its antiprotease activity at each of these time points (Figure 1B). The pre-bleomycin levels of PAI-1 in the BAL fluid were similar to that measured in plasma (∼ 75 pg/mL; Figure 1C) leading us to conclude that the PAI-1 concentration in alveolar lining fluid is likely to be higher than plasma because of the dilutional effect that occurs during the lavage procedure. In contrast to the plasma, the amount of PAI-1 in the BAL fluid of WT mice increased significantly (∼ 6-fold) on day 9 postbleomycin and remained stably increased on day 19. This increase in lavage fluid levels without an increase in plasma concentration is indicative of local production. Again, < 50% of the measured total PAI-1 in the alveolar compartment was in the active form (Figure 1D).

PAI-1 protein concentrations in bleomycin-injured WT mice. WT mice were given intratracheal bleomycin (1.15 μg/kg in 50 μL of sterile PBS) on day 0. On day 9 or day 19, animals were killed and plasma and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid were collected. The concentrations of total and active PAI-1 were measured with a bead-based ELISA. (A) Total PAI-1 concentration in plasma. (B) Active PAI-1 concentration in plasma. (C) Total PAI-1 concentration in BAL fluid. (D) Active PAI-1 concentration in BAL fluid. Results are reported as the mean concentration in pg/mL ± SEM. N = 6-8 mice per time point.

PAI-1 protein concentrations in bleomycin-injured WT mice. WT mice were given intratracheal bleomycin (1.15 μg/kg in 50 μL of sterile PBS) on day 0. On day 9 or day 19, animals were killed and plasma and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid were collected. The concentrations of total and active PAI-1 were measured with a bead-based ELISA. (A) Total PAI-1 concentration in plasma. (B) Active PAI-1 concentration in plasma. (C) Total PAI-1 concentration in BAL fluid. (D) Active PAI-1 concentration in BAL fluid. Results are reported as the mean concentration in pg/mL ± SEM. N = 6-8 mice per time point.

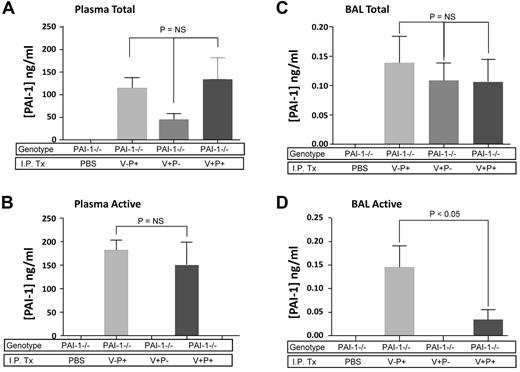

After quantifying the level of PAI-1 in WT mice, we sought to establish an intraperitoneal dosing regimen of mutant PAI-1 proteins in PAI-1−/− animals that would achieve a comparable postinjury alveolar compartment concentration. Three separate mutant constructs were administered intraperitoneally: PAI-1(V+P+) with intact vitronectin-binding and antiprotease functions; PAI-1(V+P-) with intact vitronectin-binding function, absent antiprotease activity; and PAI-1(V-P+) with intact antiprotease activity, absent vitronectin-binding function. An initial dosing schedule of 100 μg/injection every 12 hours was chosen based on a published study.28 We elected to use human PAI-1 mutants for several reasons: (1) accessibility of the proteins, (2) availability of assays to measure their concentrations, and (3) equivalency to murine PAI-1 in their ability to bind murine vitronectin and to inhibit murine uPA and t-PA (data not shown). The intraperitoneal administration of the mutant proteins was initiated on day 8 postbleomycin (corresponding to the transition between the inflammatory and fibroproliferative phases).32 Both total and active levels were measured in the plasma and BAL fluid 60 minutes after the injection on day 9. As expected, PAI-1−/− mice that received no PAI-1 treatment had no detectable PAI-1 at any time point (Figure 2A). In contrast, the injections of the mutant proteins at 100 μg/injection produced plasma levels of total PAI-1 between ∼ 50-200 ng/mL. The plasma levels of PAI-1 that retained antiprotease activity on day 9 in the mice injected with PAI-1(V+P+) and PAI-1(V-P+) were very similar to the total levels. This was expected because the mutations contained in these proteins substantially impede latency of the antiprotease function. We detected no antiprotease activity in the plasma of mice receiving PAI-1(V+P-), consistent with this protein's mutated reactive center loop (Figure 2B).

Day 9 mutant PAI-1 protein concentrations in bleomycin-injured PAI-1−/− mice. PAI-1−/− mice were given intratracheal bleomycin (1.15 μg/kg in 50 μL of sterile PBS) on day 0. On day 8, subgroups of mice were treated with either intraperitoneal injections of PBS or 100 μg/injection every 12 hours of PAI-1(V+P+), PAI-1(V+P-) or PAI-1(V-P+). On day 9, 1 hour after the last injection, plasma and BAL fluid were collected from each animal and the concentrations of total and active PAI-1 were measured with a bead-based ELISA. (A) Total PAI-1 concentration in plasma. (B) Active PAI-1 concentration in plasma. (C) Total PAI-1 concentration in BAL fluid. (D) Active PAI-1 concentration in BAL fluid. Results are reported as the mean concentration in ng/mL ± SEM. N = 5 mice per group. Groups are compared with a 1-way ANOVA with Newman-Kuels posthoc multiple comparison test.

Day 9 mutant PAI-1 protein concentrations in bleomycin-injured PAI-1−/− mice. PAI-1−/− mice were given intratracheal bleomycin (1.15 μg/kg in 50 μL of sterile PBS) on day 0. On day 8, subgroups of mice were treated with either intraperitoneal injections of PBS or 100 μg/injection every 12 hours of PAI-1(V+P+), PAI-1(V+P-) or PAI-1(V-P+). On day 9, 1 hour after the last injection, plasma and BAL fluid were collected from each animal and the concentrations of total and active PAI-1 were measured with a bead-based ELISA. (A) Total PAI-1 concentration in plasma. (B) Active PAI-1 concentration in plasma. (C) Total PAI-1 concentration in BAL fluid. (D) Active PAI-1 concentration in BAL fluid. Results are reported as the mean concentration in ng/mL ± SEM. N = 5 mice per group. Groups are compared with a 1-way ANOVA with Newman-Kuels posthoc multiple comparison test.

With respect to BAL fluid, the intraperitoneal injections of the different mutant proteins resulted in detectable levels of PAI-1 on day 9 postbleomycin. The total concentrations of each mutant protein were similar and ranged between 0.10 and 0.15 ng/mL (Figure 2C). These levels were approximately 4-fold lower than the concentration of PAI-1 measured in lavage fluid from wild-type mice on day 9. Nevertheless, the amount of antiprotease activity in the lavage fluid of mice treated with PAI-1(V-P+) was in the same range as the wild-type group (∼ 0.15 ng/mL). The concentration of active PAI-1(V+P+) was approximately 1/4 that of PAI-1(V-P+). As anticipated, treatment with PAI-1(V+P-) generated no detectable antiprotease activity in the alveolar compartment. We did not specifically measure the vitronectin-binding activity of PAI-1(V+P+) and PAI-1(V+P-) in the plasma or alveolar compartment because previous studies have confirmed stability of this function in these mutants.24,25 Therefore, the total concentration was deemed to accurately reflect the amount of vitronectin-binding protein.

In summary, our intraperitoneal dosing regimen of the PAI-1 mutant proteins resulted in plasma levels 60 minutes after injection that were sufficient to generate BAL fluid concentrations of active PAI-1 that approximated those measured in the postbleomycin BAL fluid of wild-type mice.

BAL fluid fibrinolytic activity

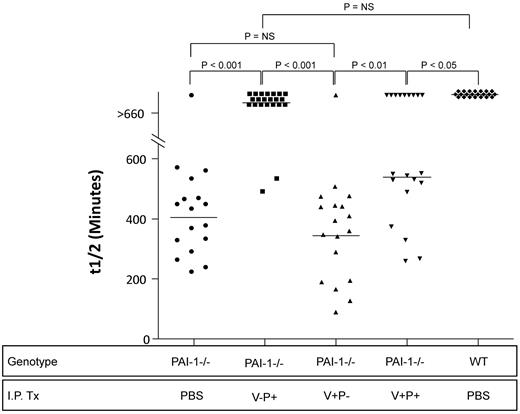

To determine the ability of intraperitoneally administered PAI-1 to functionally influence the intraalveolar environment, we measured the fibrinolytic activity of BAL fluid using a clot lysis assay that assesses the net balance between plasminogen activators and inhibitors. The 3 mutant proteins were administered beginning on day 8, and BAL fluid was collected 60 minutes after the last intraperitoneal treatment on day 9. Fibrinolytic activity is reported as the time required for 50% clot lysis (t½). Samples that induced < 50% clot lysis at the end of the 660 minute incubation were assigned a value of 660 minutes. Consistent with our previous report, bleomycin-induced lung injury resulted in the complete inhibition of lavage fluid-mediated clot lysis in WT animals (Figure 3).29 In contrast, the lavage fluid of the PAI-1−/− group that received no exogenously administered PAI-1 demonstrated rapid clot lysis with the majority of mice having t½ values of < 400 minutes. The administration of the PAI-1 mutants with intact antiprotease activity significantly impeded clot lysis with the majority of mice demonstrating t½ values > 550 minutes. In contrast, the PAI-1−/− mice administered the mutant lacking antiprotease activity had clot lysis times that completely overlapped those of the untreated group of bleomycin-injured PAI-1−/− mice.

Day 9 bronchoalveolar lavage fluid fibrinolytic activity. PAI-1−/− and WT mice were treated with intratracheal bleomycin (1.15 μg/kg in 50 μL of sterile PBS) on day 0. On day 8, subgroups of PAI-1−/− animals were treated with either intraperitoneal injections of PBS or 100 μg/injection every 12 hours of PAI-1(V+P+), PAI-1(V+P-) or PAI-1(V-P+). WT mice received the same dosing regimen of intraperitoneal PBS. On day 9, 1 hour after the last injection, BAL fluid was collected from each animal and the amount of fibrinolytic activity was measured using a clot lysis assay. Results are reported as a scatter plot of t1/2, which represents the time in minutes required for 50% of the clot to be degraded (as assessed by absorbance at 405nm). N = 17-22 mice. Groups are statistically compared with a Kruskal-Wallis test with post hoc group comparison using the Dunn Multiple Comparison Test.

Day 9 bronchoalveolar lavage fluid fibrinolytic activity. PAI-1−/− and WT mice were treated with intratracheal bleomycin (1.15 μg/kg in 50 μL of sterile PBS) on day 0. On day 8, subgroups of PAI-1−/− animals were treated with either intraperitoneal injections of PBS or 100 μg/injection every 12 hours of PAI-1(V+P+), PAI-1(V+P-) or PAI-1(V-P+). WT mice received the same dosing regimen of intraperitoneal PBS. On day 9, 1 hour after the last injection, BAL fluid was collected from each animal and the amount of fibrinolytic activity was measured using a clot lysis assay. Results are reported as a scatter plot of t1/2, which represents the time in minutes required for 50% of the clot to be degraded (as assessed by absorbance at 405nm). N = 17-22 mice. Groups are statistically compared with a Kruskal-Wallis test with post hoc group comparison using the Dunn Multiple Comparison Test.

Plasma vitronectin levels

We measured plasma vitronectin levels to assess whether injections of the mutant proteins with intact vitronectin-binding had an effect on the circulating concentration. We found similar levels of vitronectin in all of the treatment groups with mean concentrations ranging between 16-24 μg/mL, and there was no statistically significant difference in the vitronectin levels of the PAI-1−/− mice that were treated with the vitronectin-binding mutants (ie, PAI-1[V+P+] and PAI-1[V+P-] versus PAI-1[V-P+]; data not shown).

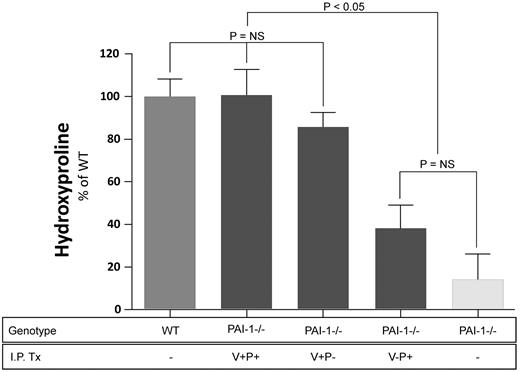

Lung collagen content

After establishing a dosing regimen that produced PAI-1 levels in the alveolar compartment comparable to WT mice, the effect of the PAI-1 mutant proteins on lung fibrosis was assessed. We measured lung hydroxyproline concentration as a quantitative assessment of lung collagen accumulation. These experiments were designed to compare the effects of the different mutant PAI-1 proteins in a pair-wise fashion because the logistical challenges of handling larger numbers of mice in a single experiment to compare all 3 proteins simultaneously were prohibitive. Figure 4 represents the pooled results of the 3 separate experiments. Because accumulation of hydroxyproline in bleomycin-treated wild-type mice varies from experiment to experiment, the hydroxyproline results for each experiment were expressed on a relative scale with 0% being the level of hydroxyproline in lungs of wild type mice receiving no bleomycin and 100% being that measured in the lungs of wild type mice receiving bleomycin. As anticipated from our prior studies, PAI-1−/− mice receiving no exogenous PAI-1 protein were significantly protected from bleomycin-induced scarring (< 20% increase). When the fully functional PAI-1(V+P+) was administered to PAI-1−/− mice, the resultant level of bleomycin-induced fibrosis was not different from that of the WT animals. Moreover, treatment with PAI-1(V+P-) induced a similar increase in fibrosis, and lung hydroxyproline content in this group was not statistically different from either the bleomycin-treated WT mice or the bleomycin-treated PAI-1−/− animals that received the fully functional protein (ie. PAI-1[V+P+]). In contrast, bleomycin administration to PAI-1−/− mice receiving PAI-1(V-P+) was associated with a modest, statistically insignificant, increase in hydroxyproline compared with bleomycin-treated PAI-1−/− mice that received no exogenous protein. This failure of PAI-1(V-P+) to reconstitute the effect of fully functional PAI-1 occurred despite similar levels of PAI-1 activity present in the BAL fluid (wild-type PAI-1: 0.148 ng/mL; PAI-1[V-P+]: 0.145 ng/mL).

Lung hydroxyproline concentration after bleomycin injury. PAI-1−/− and WT mice were treated with intratracheal bleomycin (1.15 μg/kg in 50 μL of sterile PBS) on day 0. PAI-1(V+P+), PAI-1(V+P-), and PAI-1(V-P+) were administered to subgroups of injured PAI-1−/− animals at 100 μg/injection every 12 hours beginning on day 8 and continuing through day 19. Control groups in each of the 3 studies included bleomycin-injured PAI-1−/− mice that received intraperitoneal PBS, bleomycin-injured WT mice that received intraperitoneal PBS, and untreated WT mice. On day 19, lung hydroxyproline levels were measured as an indicator of collagen content. Hydroxyproline results from the 3 studies were pooled and are normalized to the extent of fibrosis measured in the bleomycin treated WT group which is set at a 100% increase in lung collagen above baseline ± SEM. N = 14-26 mice per group in each study. Groups are compared with a 1-way ANOVA with Newman-Kuels posthoc multiple comparison test.

Lung hydroxyproline concentration after bleomycin injury. PAI-1−/− and WT mice were treated with intratracheal bleomycin (1.15 μg/kg in 50 μL of sterile PBS) on day 0. PAI-1(V+P+), PAI-1(V+P-), and PAI-1(V-P+) were administered to subgroups of injured PAI-1−/− animals at 100 μg/injection every 12 hours beginning on day 8 and continuing through day 19. Control groups in each of the 3 studies included bleomycin-injured PAI-1−/− mice that received intraperitoneal PBS, bleomycin-injured WT mice that received intraperitoneal PBS, and untreated WT mice. On day 19, lung hydroxyproline levels were measured as an indicator of collagen content. Hydroxyproline results from the 3 studies were pooled and are normalized to the extent of fibrosis measured in the bleomycin treated WT group which is set at a 100% increase in lung collagen above baseline ± SEM. N = 14-26 mice per group in each study. Groups are compared with a 1-way ANOVA with Newman-Kuels posthoc multiple comparison test.

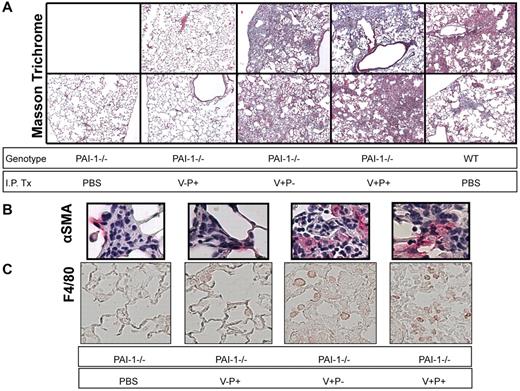

Lung histology

To complement the quantitative hydroxyproline data on which statistical analyses were carried out, we performed an additional bleomycin experiment in which we examined the lung histology of WT mice and PAI-1−/− mice treated with or without the mutant proteins. On day 19 after bleomycin, Masson trichrome-stained tissue sections of the left lung from 2 mice in each treatment group were photographed under light microscopy (Figure 5A). The bleomycin-injured PAI-1−/− mice that received only intraperitoneal PBS had very limited areas of collagen staining consistent with both the low levels of measured hydroxyproline and with prior studies. The PAI-1−/− mice treated with PAI-1(V-P+) also had minimal staining and were indistinguishable from the bleomycin-injured PAI-1−/− group that received intraperitoneal PBS. Conversely, the mice treated with the PAI-1 mutants that possessed intact vitronectin binding (ie PAI-1[V+P+] and PAI-1[V+P-]) had evidence of significant fibrosis with broad areas of dense collagen staining and hypercellularity. The extent of abnormality in these 2 groups was similar to each other and to the bleomycin-treated WT animals, and the degree of abnormality correlated with the hydroxyproline results.

Lung histology after bleomycin injury. PAI-1−/− and WT mice were treated with intratracheal bleomycin (1.15 μg/kg in 50 μL of sterile PBS) on day 0. Subgroups of PAI-1−/− mice were administered PAI-1(V+P+), PAI-1(V+P-), and PAI-1(V-P+) at 100 μg/injection every 12 hours beginning on day 8 and continuing through day 19. For comparison, groups of bleomycin-injured PAI-1−/− mice and WT mice received twice-daily intraperitoneal injections of PBS. On day 19, the left lung was fixed, and 5 micron sections were stained using Masson's trichrome (A) or immunostained with antibodies to α-SMA (B) and F4/80 (C). Images of representative sections from 2 mice (Masson trichrome) or a single mouse (immunostaining) in each treatment group are shown. Micrographs for panels A and B were obtained with a Nikon Eclipse E400 microscope (Melville, NY) and a Nikon 10×/0.25 lens (A) and a Nikon 40×/0.65 lens (B) and captured with a Diagnostic Instruments camera and SPOT Basic Version 4.0.8 acquisition software. Micrographs for panel C were obtained with a Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope and a Nikon 20× lens and captured with a Nikon DS-Qi1Mc camera and Nikon NIS-Elements BR 3.10 software.

Lung histology after bleomycin injury. PAI-1−/− and WT mice were treated with intratracheal bleomycin (1.15 μg/kg in 50 μL of sterile PBS) on day 0. Subgroups of PAI-1−/− mice were administered PAI-1(V+P+), PAI-1(V+P-), and PAI-1(V-P+) at 100 μg/injection every 12 hours beginning on day 8 and continuing through day 19. For comparison, groups of bleomycin-injured PAI-1−/− mice and WT mice received twice-daily intraperitoneal injections of PBS. On day 19, the left lung was fixed, and 5 micron sections were stained using Masson's trichrome (A) or immunostained with antibodies to α-SMA (B) and F4/80 (C). Images of representative sections from 2 mice (Masson trichrome) or a single mouse (immunostaining) in each treatment group are shown. Micrographs for panels A and B were obtained with a Nikon Eclipse E400 microscope (Melville, NY) and a Nikon 10×/0.25 lens (A) and a Nikon 40×/0.65 lens (B) and captured with a Diagnostic Instruments camera and SPOT Basic Version 4.0.8 acquisition software. Micrographs for panel C were obtained with a Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope and a Nikon 20× lens and captured with a Nikon DS-Qi1Mc camera and Nikon NIS-Elements BR 3.10 software.

We further characterized the fibrogenic effects of the different PAI-1 mutant proteins by immunostaining lung sections for α-SMA to identify myofibroblasts and F4/80 to identify macrophages. We found multiple foci of α-SMA staining scattered throughout the fibrotic areas of lung in the PAI-1(V+P+) and PAI-1(V+P-)–treated mice as well as in bleomycin-injured WT animals. Representative lesions from the PAI-1(V+P+) and PAI-1(V+P-) treated groups are demonstrated in Figure 5B. Bleomycin-injuredPAI-1−/− mice that received PAI-1(V-P+) or no exogenous protein had fewer and more confined fibrotic lesions throughout their lungs. Although we could identify α-SMA positive cells in these lesions, they were fewer in number (Figure 5B). A similar pattern was seen with F4/80 staining. The groups with extensive fibrosis had an increased number of immunopositive cells compared with the mice with limited bleomycin-induced scarring (Figure 5C).

PAI-1 BAL levels in PAI-1−/− mice that transgenically express mutant PAI-1 proteins

To substantiate the results of the mutant protein administration experiments, we developed a second model of restricted PAI-1 function by sequentially breeding mice that transgenically express the 3 different PAI-1 mutant proteins (ie, V+P+, V+P-, and V-P+) onto a PAI-1−/− and C57BL/6 background. Although the specific PAI-1 mutations in these mice are slightly different from those contained in the intraperitoneally administered proteins, the resulting functional changes are very similar. To assess alveolar compartment PAI-1 expression in these transgenic mice after bleomycin injury, we collected lavage fluid on day 21 posttreatment. We found the concentrations of PAI-1 in BAL from the 3 transgenic groups to be lower than that measured in WT mice (Figure 6). Comparing the total PAI-1 levels in the transgenic mice to each other, there was no difference in the concentration of PAI-1(V+P-) and PAI-1(V-P+) while the level of fully functional PAI-1(V+P+) was approximately 5-fold higher. Measurement of lavage fluid PAI-1 antiprotease activity revealed no difference between the WT group and the PAI-1(V+P+) transgenic mice. As was the case with the total levels, the concentration of active PAI-1(V-P+) was lower with a difference between this group and the WT and PAI-1(V+P+) mice of approximately 2-fold. A greater proportion of the total PAI-1 retained its activity in the transgenic mice compared with the WT group, and this again likely reflects the stabilizing mutations incorporated into the mutant proteins. Finally, we found no PAI-1 antiprotease activity in the PAI-1(V+P-)–expressing mice as anticipated.

Day 21 mutant PAI-1 protein concentrations in bleomycin-injured transgenic mice. PAI-1−/− mice that transgenically express PAI-1(V+P+), PAI-1(V+P-) or PAI-1(V-P+) off of the preproendothelin promoter were treated with intratracheal bleomycin (1.15μg/kg in 50 μL of sterile PBS) on day 0. Groups of WT and PAI-1−/− mice were also treated with bleomycin. A control group of WT mice was left uninjured. On day 21, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BAL) was collected from each animal and the concentrations of total (A) and active (B) PAI-1 were measured with a bead-based ELISA. Results are reported as the mean concentration in pg/mL ± SEM. N = 6-8 mice per time point. Groups are compared with a 1-way ANOVA with Newman-Kuels posthoc multiple comparison test.

Day 21 mutant PAI-1 protein concentrations in bleomycin-injured transgenic mice. PAI-1−/− mice that transgenically express PAI-1(V+P+), PAI-1(V+P-) or PAI-1(V-P+) off of the preproendothelin promoter were treated with intratracheal bleomycin (1.15μg/kg in 50 μL of sterile PBS) on day 0. Groups of WT and PAI-1−/− mice were also treated with bleomycin. A control group of WT mice was left uninjured. On day 21, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BAL) was collected from each animal and the concentrations of total (A) and active (B) PAI-1 were measured with a bead-based ELISA. Results are reported as the mean concentration in pg/mL ± SEM. N = 6-8 mice per time point. Groups are compared with a 1-way ANOVA with Newman-Kuels posthoc multiple comparison test.

Lung hydroxyproline in PAI-1−/− mice that transgenically express mutant PAI-1 proteins

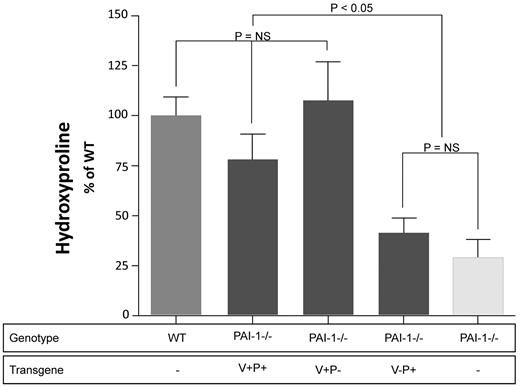

We next compared the extent of bleomycin-induced fibrosis in the mutant PAI-1–expressing transgenic mice. Control groups included bleomycin-injured WT and PAI-1−/− animals as well as untreated wild-type mice. Lung collagen content was measured at day 21 again by quantifying the concentration of hydroxyproline. Figure 7 represents the pooled results of 2 separate bleomycin studies, and again the hydroxyproline measurements are normalized to the bleomycin-treated wild-type group (n = 7-18). As anticipated, PAI-1−/− animals were protected from collagen accumulation compared with WT animals. Furthermore, transgenic mice expressing fully functional PAI-1 (ie, PAI-1([+P+]) had an increase in fibrosis that was very similar to that measured in the WT group. Consistent with our injection model, the transgenic expression of mutant PAI-1 with intact vitronectin-binding exacerbated fibrosis to a comparable degree as that measured in WT animals and those expressing PAI-1(V+P+). Also consistent with our injection model, expression of PAI-1(V-P+) had a minimal effect on fibrogenesis, and the lung hydroxyproline content of this group was not statistically different from the PBS-treated PAI-1−/− group.

Day 21 lung hydroxyproline concentrations in bleomycin-injured transgenic mice. PAI-1−/− mice that transgenically express PAI-1(V+P+), PAI-1(V+P-) or PAI-1(V-P+) off of the preproendothelin promoter were treated with intratracheal bleomycin (1.15 μg/kg in 50 μL of sterile PBS) on day 0. Groups of WT and PAI-1−/− mice were also treated with bleomycin. A control group of WT mice was left uninjured and was used to establish a baseline level of lung collagen. On day 21, lungs were harvested from each animal and the concentration of hydroxyproline was measured. Hydroxyproline results from the 2 separate studies were pooled and are normalized to the extent of fibrosis measured in the bleomycin treated WT which is set at a 100% increase in lung collagen above baseline ± SEM. N = 6-8 mice per time point. Groups are compared with a 1-way ANOVA with Newman-Kuels posthoc multiple comparison test.

Day 21 lung hydroxyproline concentrations in bleomycin-injured transgenic mice. PAI-1−/− mice that transgenically express PAI-1(V+P+), PAI-1(V+P-) or PAI-1(V-P+) off of the preproendothelin promoter were treated with intratracheal bleomycin (1.15 μg/kg in 50 μL of sterile PBS) on day 0. Groups of WT and PAI-1−/− mice were also treated with bleomycin. A control group of WT mice was left uninjured and was used to establish a baseline level of lung collagen. On day 21, lungs were harvested from each animal and the concentration of hydroxyproline was measured. Hydroxyproline results from the 2 separate studies were pooled and are normalized to the extent of fibrosis measured in the bleomycin treated WT which is set at a 100% increase in lung collagen above baseline ± SEM. N = 6-8 mice per time point. Groups are compared with a 1-way ANOVA with Newman-Kuels posthoc multiple comparison test.

Discussion

The ability of PAI-1 to worsen fibrosis has been known for over a decade, but the mechanisms for this PAI-1 effect remain uncertain. We have speculated that the antiprotease property of PAI-1 may be important by inhibiting plasminogen activators and other proteases involved in the removal of extracellular matrix proteins that accumulate at sites of tissue injury. This function also may block the proteolysis needed for activation of growth factors involved in reparative pathways. We have also hypothesized that the binding of PAI-1 to vitronectin might result in profibrotic consequences. In particular, in vitro studies reveal that PAI-1 can disrupt epithelial cell adherence to vitronectin by blocking interactions between cell surface integrins and/or the urokinase receptor and this matrix protein.19 This interference with vitronectin-integrin interactions delays alveolar epithelial cell wound closure in a cell culture model, and efficient resurfacing of the denuded alveolar surface is hypothesized to be important in limiting fibrosis. Disrupting matrix-integrin interactions might also cause epithelial cells and fibroblasts to adopt a more fibrotic phenotype.6,20,21,33 To determine how each PAI-1 function influences in vivo fibrogenesis, we used 2 different approaches to reconstitute PAI-1 with defective antiprotease or vitronectin binding properties. Our study provides the first evidence that the vitronectin binding function of PAI-1 can worsen fibrosis independently of any antiprotease activity. In particular, reconstituting PAI-1−/− mice with PAI-1 lacking antiprotease activity but with retained vitronectin binding function (PAI-1[V+P-]) generated as much fibrosis after bleomycin injury as PAI-1 possessing both antiprotease and vitronectin binding properties. Future studies are required to determine whether the profibrotic effect of PAI-1's vitronectin binding function is unique to bleomycin-induced injury or whether it will promote fibrosis in other lung injury models. Future studies are also required to define the mechanism by which PAI-1's vitronectin adherence drives fibrosis and whether it might be related to increased myofibroblast or macrophage accumulation as demonstrated in the immunostained sections or via altered profibrotic/antifibrotic factor expression.

Although our results demonstrate that PAI-1 lacking antiprotease function had a significant profibrotic effect, it does not exclude the possibility that the antiprotease activity of PAI-1 may contribute in a minor way to the fibrotic process. In fact, our laboratory previously reported that an inhibitor of plasmin's proteolytic activity, tranexamic acid, caused worsening of bleomycin induced fibrosis.5 Similarly, it has been shown that preventing plasmin formation by deleting the plasminogen gene caused increased collagen accumulation in mice afterbleomycin administration.34 Our current data show that reconstitution of PAI-1−/− mice with PAI-1 having intact antiprotease function but no vitronectin binding capacity did cause a small increase in mean lung hydroxyproline, and the extent of increase in this group was of a similar magnitude to that achieved with tranexamic acid treatment in our prior study (∼ 15%). However, this modest increase in postbleomycin lung collagen content between the groups that expressed or were administered PAI-1(V-P+) and the PAI-1−/− mice that received no exogenous PAI-1 did not reach statistical significance, although our power to exclude a significant difference at P < .05 from our data are low. On the other hand, if the difference in mean hydroxyproline that we detected is true, it would require a sample size of ∼ 50 animals per group to achieve statistical significance at a P < .05 and a power of 80%. Similarly, the trend toward worse fibrosis in the PAI-1(V-P+) group in the experiments using transgenic mice would require ∼ 90 mice per group to achieve a power of 80%.

A profibrotic role for PAI-1 is not unique to the bleomycin lung model, but has been demonstrated in several pathologic conditions that occur in different organs in a variety of animal models.3 It is quite possible that the relative importance of the different mechanisms by which PAI-1 influences fibrosis may vary in the different situations. Our finding that vitronectin binding of PAI-1 accentuates lung fibrosis even in the absence of its antiprotease activity has not been previously reported. The only other fibrotic condition that has been intensively studied to separate the antiprotease and vitronectin binding functions of PAI-1 involves the induction of glomerulonephritis in rats by administrating anti–thy-1 antibody. Huang and colleagues intravenously infused a PAI-1 mutant lacking antiprotease activity but retaining vitronectin binding capability and found it protected the rats from glomerular injury and fibrosis.35 In contradistinction, the analogous experiments in our study showed worsening of lung fibrosis. However, there is a critical difference between the studies. We completely controlled the type of PAI-1 in our in vivo experiments by using mice genetically deficient in PAI-1−/−. The study by Huang and colleagues involved infusing mutant PAI-1 proteins into normal animals that produced their own native PAI-1 in response to glomerular injury. They concluded that the protection they observed from mutant PAI-1 lacking antiprotease activity but retaining vitronectin binding was because of the displacement of native PAI-1 from the provisional matrix, thus removing the antiprotease activity of native PAI-1.35,36 Their experimental design could not have detected a protease-independent but vitronectin dependent effect of PAI-1 on fibrosis because of the continual presence of native PAI-1 with its vitronectin binding properties.

Because of the complexities of our experimental model, we were not able to achieve identical levels of PAI-1 across the various mutants. However, firm conclusions can be reached regarding the relative fibrotic effects of PAI-1(V-P+) and PAI-1(V+P-). In the experiments using exogenously administered PAI-1 protein, both plasma and BAL fluid concentrations of PAI-1(V-P+) were higher than that of PAI-1(V+P-). Yet, the profibrotic effect of PAI-1(V-P+) was substantially less than that of PAI-1(V-P+). A similar pattern was seen in the mice expressing mutant PAI-1 transgenes.

Our results also provide important information regarding the temporal effects of PAI-1 on bleomycin induced fibrosis. We found that despite an 8-day delay between bleomycin administration and the start of PAI-1 injections, the profibrotic effect of PAI-1 was quite evident. Thus, PAI-1 is not required during the early inflammatory phase but rather can have its full effect when present during the later fibroproliferative period when interstitial collagens are accumulating. This observation conforms nicely to our prior finding that PAI-1 deficiency has no effect on the initial inflammatory phase of bleomycin-induced lung injury. In particular, we found no difference between wild type and PAI-1−/− mice in the inflammatory cell influx or increased alveolar permeability that occurred 7 days after bleomycin treatment.5

In summary, our studies have elucidated important mechanisms by which PAI-1 drives pulmonary fibrosis. We found using 2 different approaches that the vitronectin-binding property of PAI-1 was critical for the profibrotic effect of PAI-1 independent of its antiprotease properties. Furthermore, the results from our experiments using PAI-1 protein injections demonstrate that PAI-1 has a profibrotic effect when present during the late fibroproliferative phase of bleomycin induced fibrosis and that PAI-1 does not need to be present during the early acute lung injury/inflammatory phase. This observation is particularly noteworthy because it suggests that a PAI-1 focused therapy may be effective in diseases such as idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis where progressive fibroproliferation even in the absence of active inflammation leads to organ failure.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Bi Yu for his work on preliminary studies.

The authors also acknowledge their funding sources which include the National Institutes of Health, 1 R01 HL078871 (T.H.S.), the Quest For Breath Foundation (T.H.S.), P01 HL089407 and R01 HL55374 (D.A.L.), K08 HL085290 (K.K.K.), and K08 HL081059 (J.C.H.).

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution A.C. participated in experimental design, performed animal experiments, and contributed to data analysis and manuscript preparation; J.C.H. participated in data analysis and manuscript preparation; K.K.K. performed immunostaining for α-SMA and participated in data analysis; T.J.K. performed immunostaining for F4/80 and participated in data analysis; M.L.N. performed immunostaining for F4/80; N.S. performed animal experiments including bleomycin injections and tissue collections and hydroxyproline studies; M.W. performed PAI-1 concentration measurements; A.C. participated in animal experiments including bleomycin injections and transgenic mouse breeding; B.X. participated in animal experiments including bleomycin injections and measurement of PAI-1 levels in lavage fluid samples; Y.L. participated in animal experiments including bleomycin injections and transgenic mouse breeding; M.P.G. participated in animal experimentsincluding bleomycin injections and dosing studies of the PAI-1 mutant proteins; R.H.S. participated in experimental design, data analysis, and manuscript preparation; D.A.L. participated in experimental design, data analysis, and manuscript preparation and provided PAI-1 mutant proteins; and T.H.S. was responsible for hypothesis generation, experimental design, performing animal experiments, data analysis, and manuscript preparation.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Thomas H. Sisson, MD, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, University of Michigan Medical Center, 1150 W Medical Center Dr, 6301 MSRB III, Ann Arbor, MI; e-mail: tsisson@umich.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal