Abstract

Dysfunction of AML1/Runx1, a transcription factor, plays a crucial role in the development of many types of leukemia. Additional events are often required for AML1 dysfunction to induce full-blown leukemia; however, a mechanistic basis of their cooperation is still elusive. Here, we investigated the effect of AML1 deficiency on the development of MLL-ENL leukemia in mice. Aml1 excised bone marrow cells lead to MLL-ENL leukemia with shorter duration than Aml1 intact cells in vivo. Although the number of MLL-ENL leukemia-initiating cells is not affected by loss of AML1, the proliferation of leukemic cells is enhanced in Aml1-excised MLL-ENL leukemic mice. We found that the enhanced proliferation is the result of repression of p19ARF that is directly regulated by AML1 in MLL-ENL leukemic cells. We also found that down-regulation of p19ARF induces the accelerated onset of MLL-ENL leukemia, suggesting that p19ARF is a major target of AML1 in MLL-ENL leukemia. These results provide a new insight into a role for AML1 in the progression of leukemia.

Introduction

AML1, also called RUNX1, CBFA2, or PEBP2αB, was found at the breakpoint on chromosome 21 from acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients with t(8;21)(q22;q22).1 AML1 is a transcription factor that belongs to RUNX family proteins. It heterodimerizes with CBFβ and binds to the specific DNA sequence (TGT/CGGT), called the PEBP2 binding site.2-4 AML1 regulates transcription of various genes related to normal hematopoiesis, and targeted disruption of AML1 in mice revealed that it is essential for definitive hematopoiesis during embryogenesis.5 Conventional knockout mice are embryonic lethal because of hemorrhage in the central nervous system. We generated conditional knockout mice of AML1 to study a role of AML1 in adult hematopoiesis after birth.6 These mice showed thrombocytopenia because of maturation block of megakaryocytes, perturbed lymphocyte development, and increase in the number of hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells.

The disruption of AML1 functions is highly related to occurrence of myeloid malignancies through chromosomal translocation or point mutation.7-9 Although introduction of AML1-ETO, the fusion protein generated in AML with t(8;21) chromosomal translocation, into mouse bone marrow (BM) cells leads to proliferation of myeloid cells, it is not sufficient to induce leukemia without providing alkylating agents for the mice.10-14 AML1-ETO acts as a dominant negative effector for wild-type AML1, and it is supposed that function of AML1 is lost in AML1-ETO–expressing cells. These results suggest that the other genetic change in addition to the loss of AML1 function is necessary for the development of full-blown leukemia. In mice, c-Kit and FLT3-ITD mutations are reported to collaborate with gene alteration of AML1 in leukemogenesis.15,16 Furthermore, positive correlation between c-Kit mutations and AML1-ETO is reported in human cases.17,18 However, precise molecular mechanisms that underlie the development of AML1-related leukemia are still to be elucidated.

We previously demonstrated that hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells are expanded in Aml1-deficient mice.19 Expansion of the hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells is also observed in the mouse models of AML with t(8;21), in which the chimeric protein AML1-ETO suppresses the normal function of AML1. Expansion of the hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells is supposed to predispose the animals to full-blown leukemia when additional mutations occur in the proliferating cells.

Mixed lineage leukemia (MLL) is located on band q23 of the chromosome 11 and is frequently translocated in human leukemias. In addition to formation of fusion genes with > 50 partners, partial tandem duplication of MLL (MLL-PTD) is also found in human leukemias. Interestingly, in human leukemias without 11q23 chromosomal translocation, point mutations of AML1 and MLL-PTD are frequently observed in the same patients.17 This prompted us to speculate that AML1 loss and MLL mutations may cooperate in the development of human leukemia. To test this, we evaluated the effect of AML1 loss on MLL-related leukemia using a mouse model and found that loss of AML1 significantly accelerated the development of MLL-leukemia. We also found that p19ARF, a known target of AML1 and AML1-ETO,20 plays a critical role in the leukemia acceleration caused by AML1 loss. These findings provide a novel mechanistic basis of cooperation between impaired AML1 function and other leukemia-related gene alteration.

Methods

Mouse strains

Aml1flox/flox Mx-Cre (+) mice and Aml1flox/flox Mx-Cre (−) mice were previously described.6 To induce Aml1 deletion in vivo, mice were intraperitoneally injected with 250 μg of polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid (pIpC; Sigma-Aldrich) 3 times every other day and were used for the experiments after 4 to 8 weeks.6 The genotypes of the loxP-flanked Aml1 (Aml1f) and excised Aml1 (Aml1Δ) loci were analyzed, using primers as described previously.6 Eight- to 10-week-old female C57BL/6J mice were used as recipients in transplantation. Mice were kept at the Center for Disease Biology and Integrative Medicine, University of Tokyo, according to institutional guidelines. All animal experiments were approved by the University of Tokyo Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Retrovirus infection

The cDNA of MLL-ENL (generous gift from Toshio Kitamura) was subcloned into the EcoRI site of pMSCV-neo (Clontech).21 To produce MLL-ENL–expressing retrovirus, Plat-E packaging cells (generous gift from Toshio Kitamura) or Ecopack2-293 cells (Clontech) were transiently transfected with retroviral constructs, as described previously.22,23 To produce green fluorescent protein (GFP)– or AML1-GFP–expressing retrovirus, we used cMP34 packaging cells.24 Two retrovirus vectors expressing small hairpin RNAs were constructed for p19ARF.25 After transfection, puromycin-resistant cells were selected in medium (RPMI with 20% FCS, 10 ng/mL IL-3) containing 2 μg/mL puromycin for 3 days.

Colony replating assay

The cells infected with retrovirus were washed by PBS and resuspended in IMDM (with 2% FCS), and 1 × 105 cells were plated in the 35-mm plate with Methocult M3434 (StemCell Technologies) containing 10 ng/mL of murine GM-CSF and 0.8 mg/mL of G418. After 7 days, the cells were collected and washed by PBS twice. A total of 1 × 104 cells were plated in the same semisolid culture medium without G418. Colony counting and replating were performed every 7 days.

Transplantation assay

A total of 1 × 106 of cells infected with retrovirus were injected into sublethally irradiated (x-ray, 7.5 Gy) recipient mice via the tail vein. To transplant leukemic cells into recipient mice, mononuclear cells isolated from the spleen of leukemic mice were infected with retrovirus and injected into sublethally irradiated (7.5 Gy) recipient mice via the tail vein.

In vitro liquid culture

Leukemic or immortalized cells were cultured in RPMI medium containing 20% FCS and 10 ng/mL of IL-3. In apoptotic cell analyses, liquid culture medium without IL-3 was also used.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Quantitative real-time PCR was performed as described previously.26 mRNA expression levels of all genes, relative to those of normal BM mononuclear cells, were normalized to Gapdh. The primers used are as follows: Aml1: TaqMan Gene Expression Assay (Applied Biosystems; Assay ID Mm00486762_m1); Gapdh: forward, TGGTGAAGCAGGCATCTGAG; reverse, TGCTGTTGAAGTCGCAGGAG; p19ARF: forward, CATGTTGTTGAGGCTAGAGAGG; reverse, TCGAATCTGCACCGTAGTTG; p21CIP1: forward, CTGTTCCGCACAGGAGCAA; reverse, ACGGCGCAACTGCTCACT/TaqMan probe TGTGCCGTTGTCTCTTCGGTCCC (Applied Biosystems); p53: forward, CACAGCGTGGTGGTACCTTATG; reverse, TTCCAGTGTGATGATGGTAAGGA/TaqMan probe CCACCCGAGGCCGGCTCTG (Applied Biosystems); p27KIP1: forward, GGCCCGGTCAATCATGAA; reverse, TTGCGCTGACTCGCTTCTTC; p15INK4B: forward, TCAGAGACCAGGCTGTAGCAA; reverse, CCCCGGTCTG; Bax: forward, AAAATGGCCAGTGAAGAGCA; reverse, GTGAGCGGCTGCTTGTCT/TaqMan probe (Roche Universal Probe Library #83); p16INK4A: forward, CCCAACGCCCCGAACT; reverse, GTGAACGTTGCCCATCATCA; PU.1: forward, GGAGAAGCTGATGGCTTGG; reverse, CAGGCGAATCTTTTTCTTGC TaqMan probe (Roche Universal Probe Library #94); Bmi1: forward, AAACCAGACCACTCCTGAACA; reverse, TCTTCTTCTCTTCATCTCATTTTTGA/TaqMan probe (Roche Universal Probe Library #20); Hoxa5: forward, GCAAGCTGCACATTAGTCAC; reverse, GCATGAGCTATTTCGATCCT; Hoxa7: forward, CTCTTTCTTCCACTTCATGCGCCGA; reverse, TGCGCCTCCTACGACCAAAACATC; Hoxa9: forward, TCCCTGACTGACTATGCTTGTG; reverse, GTTGGCAGCCGGGTTATT/TaqMan probe (Roche Universal Probe Library #25); Hoxa10: forward, GGAAGGAGCGAGTCCTAGA; reverse, TTCACTTGTCTGTCCGTGAG; Meis1: forward, TTGTAATGGACGGTCAGCAG; reverse, GCTACATACTCCCCTGGCATA/TaqMan probe (Roche Universal Probe Library #105); Gapdh promoter: forward, CACAAACAGGACCCAACATT; reverse, ATGAAGTGTCCCTCCTTGTC; p19ARF AML1 binding site (distal): forward, AGTTAACCGGAGCGAAAGCC; reverse, CACCCATCGCGGTGACAG; p19ARF AML1 binding site (proximal): forward, GGATTACAACTTACACCTGCGGTC; reverse, CCACAGATTCTATTTTTCACGCAC.

Flow cytometric analysis

Cells were sorted with FACSAria, and analysis was performed on an LSRII (BD Biosciences). To analyze the cell surface antigen, anti–Mac-1 (phycoerythrin-conjugated), Gr-1 (allophycocyanin), CD117 (allophycocyanin), and Sca-1 (phycoerythrin; BD Biosciences) were used. To analyze the cell-cycle status, cells were stained with propidium iodide (BD Biosciences) at room temperature for 30 minutes. Apoptosis was assayed by annexin V and propidium iodide staining. To analyze the intracellular protein levels, cells were fixed and permeabilized with fixation/permeabilization solution (BD Cytofix/Cytoperm Fixation/Permeabilization kit) following the manufacturer's protocol, before incubation with antibodies. Fixed cells were incubated with either anti-p53 (1C12) mouse monoclonal antibody (AlexaFluor-647–conjugated) or mouse (MOPC-21) monoclonal antibody IgG1 isotype control (AlexaFluor-647–conjugated; Cell Signaling Technology) at room temperature for 60 minutes. The geometric mean fluorescence intensity was calculated by the subtraction of that of the cells stained with isotype control IgG1 from that of the cells stained with anti-p53 antibodies.

ChIP assay

ChIP assays were performed as described earlier,27 with minor modifications. A total of 1 × 107 of splenocytes from leukemic mice were crosslinked with 1% formaldehyde. Subsequently, chromatin was fragmented by sonication to obtain an average fragment length of 200-900 bp (Bronson Sonifier 250). After the chromatin fraction was incubated with normal rabbit IgG (Abcam) or polyclonal rabbit AML1/Runx1 antibody (Active Motif), immune complexes were bound to Dynabeads protein G (Invitrogen). Eluted DNA samples were then analyzed by quantitative real-time PCR using specific primer pairs listed in the primers for quantitative real-time PCR. PCR results were calculated validly using the ΔΔCt method.

Luciferase reporter assay

The mouse p19ARF promoter region was obtained by PCR with the following primers: forward, GCCGGTACCGTACCGCTAAGGGTTCAAAACGCCC; reverse, GCGAGATCTCTCACAGTGACCAAGAACCTGCGAC. This fragment was subcloned into luciferase reporter vector, pGL4.10. Mutations of the PEBP2 sites in the p19ARF promoter construct were introduced by QuickChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) using the following primers: forward, CCGCGGCGCTGGCTGTCAAAAAAATGGGTGGCGAGCGAAGC; reverse, GCTTCGCTCGCCACCCATTTTTTTGACAGCCAGCGCCGCGG. For reporter assays, COS-7 cells were seeded in 12-well culture plates at a density of 1 × 105 cells per well. At 6 hours after seeding, the cells were transfected with 200 ng of each luciferase reporter construct, together with 200 ng of each appropriate expression plasmid (eg, pME18S vector [Mock], pME18S-AML1) using FuGENE 6 (Roche Diagnostics). The cells were harvested 40 hours after transfection, and luciferase activities were analyzed. CMV β-gal expression vector was also cotransfected for normalization of transfection efficiency. Results are expressed as fold activation with SD.

Statistical analysis

To compare data between groups, unpaired Student t test was used when equal variance was met by the F test. When unequal variances were detected, the Welch t test was used. Differences were considered statistically significant at a P value < .05. Statistical analyses were performed using the statistical software package R Version 2.13.0.

Results

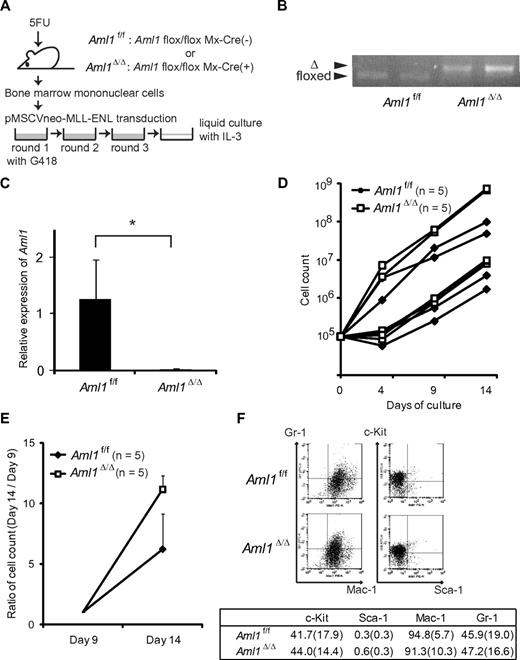

Proliferation of MLL-ENL–transduced hematopoietic precursors is enhanced on AML1 deletion

To examine the effect of AML1 deletion on proliferation of MLL leukemic cells, we retrovirally transduced BM progenitors from Aml1flox/flox; Mx-Cre(−; Aml1f/f) or Aml1flox/flox; Mx-Cre (+) mice that had been injected with pIpC (Aml1Δ/Δ), with MLL-ENL vector (Figure 1A). As shown in the previous study, MLL-ENL-infected BM progenitors were immortalized and proliferated in the methylcellulose culture.21 Cre-mediated recombination was confirmed by genomic PCR in the BM cells harvested from the pIpC-treated Aml1flox/flox; Mx-Cre (+) mice (Figure 1B). The absence of AML1 mRNA was additionally confirmed by quantitative reverse-transcribed PCR of Aml1-excised immortalized cells (Figure 1C). We transferred these immortalized cells into liquid cultures in the presence of IL-3. Although growth of the cells differed immediately after the initiation of liquid cultures, each type of cells showed exponential growth after several days (Figure 1D-E). After day 9, Aml1-excised immortalized cells proliferated significantly faster than the Aml1 intact controls (P < .001, Figure 1E). These results indicate that the proliferation of MLL-ENL-transformed cells is enhanced in the absence of AML1. Aml1-excised transformed cells were Gr-1+, Mac-1+, Sca1−, and c-Kitlow/−, which was not significantly different from control cells (Figure 1F). Morphologic changes were neither observed (data not shown).

Proliferation of Aml1-excised immortalized BM cells is enhanced in vitro. (A) MLL-ENL was retrovirally transduced into Aml1 intact (Aml1f/f) and excised (Aml1Δ/Δ) BM cells, and replating assay was performed using these cells. (B) Genotyping of Aml1 floxed and Δ alleles by PCR from Aml1f/f and Aml1Δ/Δ immortalized cells. Each lane indicates the PCR products of an independent case. (C) mRNA levels of Aml1 in Aml1f/f and Aml1Δ/Δ immortalized cells were measured. *P < .05. (D) Growth of Aml1f/f (n = 5; ♦) or Aml1Δ/Δ (n = 5; □) immortalized cells in liquid medium. Data are on a semilogarithmic plot of cell counts versus time. (E) Growth of the immortalized cells as in Figure 1D after day 9. Cell counts at day 14 relative to those at day 9 are shown as mean ± SD on a linear plot (n = 5 from each group). Day 14 proliferation was significantly different between groups (t test, P < .001). (F) Flow cytometric analyses of the colony-forming cells after 3 rounds of replating. (Top) Representative fluorescence-activated cell sorter plots. (Bottom) Percentages of cells expressing indicated surface markers in each group (mean ± SD).

Proliferation of Aml1-excised immortalized BM cells is enhanced in vitro. (A) MLL-ENL was retrovirally transduced into Aml1 intact (Aml1f/f) and excised (Aml1Δ/Δ) BM cells, and replating assay was performed using these cells. (B) Genotyping of Aml1 floxed and Δ alleles by PCR from Aml1f/f and Aml1Δ/Δ immortalized cells. Each lane indicates the PCR products of an independent case. (C) mRNA levels of Aml1 in Aml1f/f and Aml1Δ/Δ immortalized cells were measured. *P < .05. (D) Growth of Aml1f/f (n = 5; ♦) or Aml1Δ/Δ (n = 5; □) immortalized cells in liquid medium. Data are on a semilogarithmic plot of cell counts versus time. (E) Growth of the immortalized cells as in Figure 1D after day 9. Cell counts at day 14 relative to those at day 9 are shown as mean ± SD on a linear plot (n = 5 from each group). Day 14 proliferation was significantly different between groups (t test, P < .001). (F) Flow cytometric analyses of the colony-forming cells after 3 rounds of replating. (Top) Representative fluorescence-activated cell sorter plots. (Bottom) Percentages of cells expressing indicated surface markers in each group (mean ± SD).

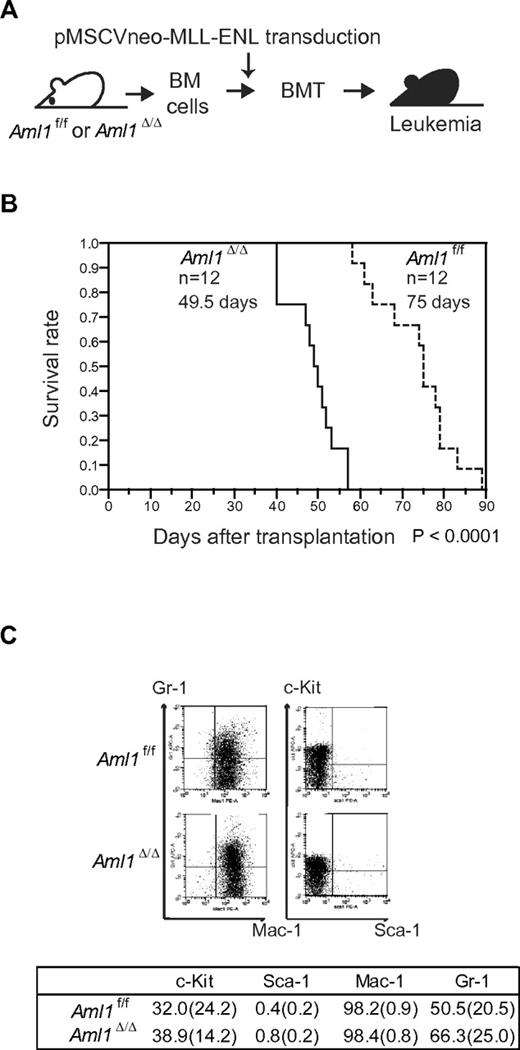

Loss of AML1 accelerates leukemia onset in MLL-ENL mice

Our in vitro studies showed that loss of AML1 enhances the proliferation of MLL-ENL–transformed cells. These results suggest that loss of AML1 accelerates the onset of MLL-ENL leukemia. To test this, we retrovirally transduced MLL-ENL into Aml1-intact or -excised BM progenitors. Those cells were transplanted into sublethally irradiated recipient mice (Figure 2A). Mice transplanted with control MLL-ENL cells died of leukemia within 90 days, as is consistent with the previous report (Figure 2B).24 Remarkably, leukemia onset was significantly earlier in mice transplanted with Aml1-excised MLL-ENL cells (Aml1Δ/Δ; 49.5 ± 6 days vs Aml1f/f; 75 ± 9 days, P < .01). Immunophenotyping of leukemic cells revealed infiltration of Mac-1+/Sca-1− cells, and Wright-Giemsa–stained peripheral blood smears showed immature blasts in both types of leukemia (Figure 2C; and data not shown). Surface marker expression, including c-Kit, Sca-1, Mac-1, and Gr-1, was not significantly changed regardless of Aml1 status (Figure 2C).

Earlier onset of Aml1-excised MLL-ENL leukemia. (A) BM cells from Aml1f/f and Aml1Δ/Δ mice were transduced with MLL-ENL and transplanted into congenic mice. (B) Survival curves of the mice transplanted with Aml1f/f and Aml1Δ/Δ cells transduced with MLL-ENL. Data from 12 mice for each group are shown. Comparison of survival curve was performed using log-rank test. (C) Flow cytometric analyses of the leukemic cells from transplanted mice. (Top) Representative fluorescence-activated cell sorter plots. (Bottom) Percentages of cells expressing indicated surface markers in each group (mean ± SD).

Earlier onset of Aml1-excised MLL-ENL leukemia. (A) BM cells from Aml1f/f and Aml1Δ/Δ mice were transduced with MLL-ENL and transplanted into congenic mice. (B) Survival curves of the mice transplanted with Aml1f/f and Aml1Δ/Δ cells transduced with MLL-ENL. Data from 12 mice for each group are shown. Comparison of survival curve was performed using log-rank test. (C) Flow cytometric analyses of the leukemic cells from transplanted mice. (Top) Representative fluorescence-activated cell sorter plots. (Bottom) Percentages of cells expressing indicated surface markers in each group (mean ± SD).

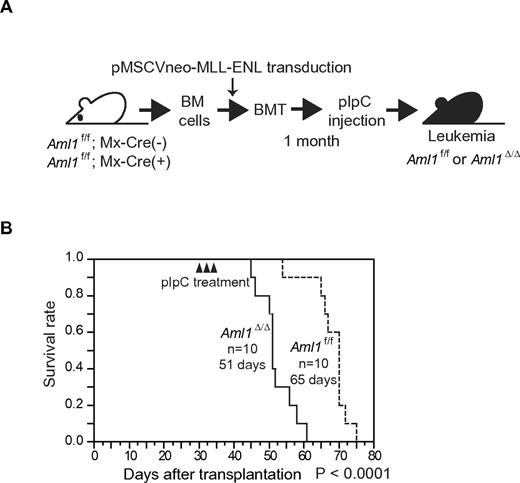

Induction of MLL-ENL leukemia after conditional deletion of AML1

A previous study shows that MLL-ENL leukemia can arise from hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), common myeloid progenitors (CMPs), and granulocyte-macrophage progenitors (GMPs), whereas transformation efficiency is higher in HSCs than in CMPs and GMPs.28 In our previous experiment of MLL-ENL leukemia, we retrovirally introduced MLL-ENL into Aml1-excised BM cells. On the other hand, we have already reported that the number of HSCs is increased in Aml1-excised mice.19 Because HSCs are increased in the Aml1-excised BM, there is one possibility that earlier onset of MLL-ENL leukemia from Aml1-excised BM cells is just the result of an increased number of MLL-ENL–transduced HSCs in the Aml1-excised BM. To explore this possibility, we transduced MLL-ENL into the BM cells from Aml1flox/flox; Mx-Cre (−) or Aml1flox/flox; Mx-Cre (+) before injection of pIpC. We transplanted those cells into sublethally irradiated recipient mice and injected pIpC one month after transplantation to delete Aml1 in Aml1flox/flox; Mx-Cre (+) cells (Figure 3A). We found that the onset of leukemia from Aml1-excised cells (Aml1Δ/Δ) was earlier than that of control cells (Aml1f/f; Figure 3B), indicating that loss of AML1 accelerates the development of leukemia even after introduction of MLL-ENL. These results suggest that the earlier onset of MLL-ENL leukemia from Aml1-excised hematopoietic progenitors is not simply the result of an increase in immature cells that can be efficiently transformed by MLL-ENL but potentially caused by an enhanced leukemogenic potential of MLL-ENL–transduced cells.

Deletion of the AML1 gene after MLL-ENL induction accelerates the onset of leukemia in transplanted mice. (A) BM cells from Aml1f/f; Mx-Cre (+) or Aml1f/f; Mx-Cre (−) were transduced with MLL-ENL and transplanted into congenic mice. Injection with pIpC was performed 3 to 4 weeks after transplantation, so that the Aml1 gene was excised in transplanted Aml1f/f; Mx-Cre (+) cells (Aml1Δ/Δ). (B) Survival curves of the recipient mice. Data from 10 mice for each group are shown. Arrowheads indicate pIpC injection. Comparison of survival curve was performed using log-rank test.

Deletion of the AML1 gene after MLL-ENL induction accelerates the onset of leukemia in transplanted mice. (A) BM cells from Aml1f/f; Mx-Cre (+) or Aml1f/f; Mx-Cre (−) were transduced with MLL-ENL and transplanted into congenic mice. Injection with pIpC was performed 3 to 4 weeks after transplantation, so that the Aml1 gene was excised in transplanted Aml1f/f; Mx-Cre (+) cells (Aml1Δ/Δ). (B) Survival curves of the recipient mice. Data from 10 mice for each group are shown. Arrowheads indicate pIpC injection. Comparison of survival curve was performed using log-rank test.

AML1 deletion in MLL-ENL mice does not increase leukemia-initiating cells

Next, we performed limiting dilution analysis to estimate the frequency of leukemia-initiating cells (LICs) of MLL-ENL leukemia in these murine models. Twenty to 500 000 MLL-ENL leukemic cells harvested from recipient mice were transplanted into sublethally irradiated secondary recipient mice (Figure 2A). As shown in Table 1, 500 leukemic cells were sufficient to induce leukemia in all secondary recipient mice, regardless of the status of Aml1. Moreover, the incidence of leukemia in the recipient mice injected with 20 Aml1-excised leukemic cells was not significantly changed. These results indicate that the frequency of LICs is not altered in Aml1-excised MLL-ENL leukemic cells and that the early onset of MLL-ENL leukemia is not the result of an increased number of LICs.

Quantification of leukemia initiating cells

| No. of transplanted cells . | No. of leukemic mice/no. of transplanted mice . | |

|---|---|---|

| Aml1f/f MLL-ENL cells . | Aml1Δ/Δ MLL-ENL cells . | |

| 500 000 | 8/8 | 8/8 |

| 50 000 | 8/8 | 8/8 |

| 5000 | 8/8 | 8/8 |

| 500 | 8/8 | 8/8 |

| 20 | 5/8 | 4/8 |

| No. of transplanted cells . | No. of leukemic mice/no. of transplanted mice . | |

|---|---|---|

| Aml1f/f MLL-ENL cells . | Aml1Δ/Δ MLL-ENL cells . | |

| 500 000 | 8/8 | 8/8 |

| 50 000 | 8/8 | 8/8 |

| 5000 | 8/8 | 8/8 |

| 500 | 8/8 | 8/8 |

| 20 | 5/8 | 4/8 |

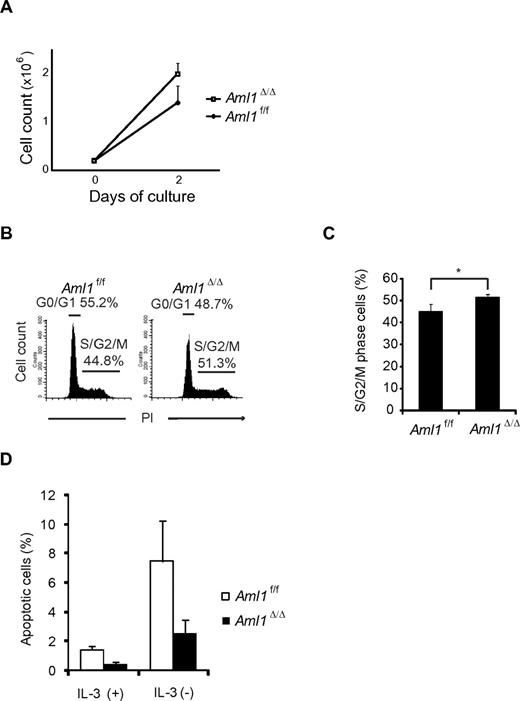

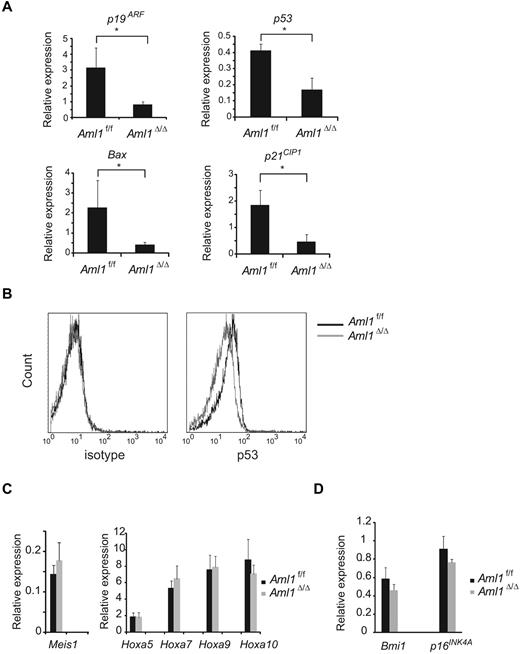

Decreased expression of cell cycle– and apoptosis-related genes in Aml1-excised leukemic cells

Given that the number of LICs is not significantly altered in Aml1-excised MLL-ENL leukemic cells, we evaluated the correlation between Aml1 status and proliferative potentials of MLL-ENL leukemic cells. As shown in Figure 4A, the growth rate of Aml1-excised MLL-ENL cells obtained from the leukemic mice culture was enhanced in liquid compared with that of Aml1-intact MLL-ENL cells, as is consistent with the proliferation of the in vitro transformed cells (Figure 1E). To explore the mechanism of the growth advantage of MLL-ENL leukemic cells in the absence of AML1, we analyzed cell-cycle status and apoptotic rate of Aml1-excised MLL-ENL leukemic cells. Cell-cycle analyses revealed a significant increase of S/G2/M phase cells in Aml1-excised MLL-ENL leukemic cells (Figure 4B-C). Moreover, the rate of annexin V-positive apoptotic cells was reduced in Aml1-excised MLL-ENL leukemic cells in liquid culture with and without IL-3 (Figure 4D). These results suggest that growth advantage of Aml1-excised MLL-ENL leukemic cells depends on both acceleration of cell-cycle progression and inhibition of apoptosis. Consistently, expression of cell cycle–regulating genes, such as p19ARF and p21CIP1, decreased in Aml1-excised leukemic cells (Figure 5A). Expression of apoptosis-related genes, such as p53 and Bax, also decreased in those cells (Figure 5A). On flow cytometric analysis, we observed that Aml1-excised leukemic cells expressed lesser amount of p53 protein (Figure 5B). The geometric mean fluorescence intensity and SD of p53–AlexaFluor-647 was 9.7 ± 1.3 for Aml1-excised cells and 14.2 ± 2.0 for controls (P = .030). In contrast, expression of Meis1 and Hoxa (Hoxa5, Hoxa7, Hoxa9, and Hoxa10), which are direct target genes of MLL-ENL,29 was not changed in Aml1-excised MLL-ENL cells compared with controls (Figure 5C).

Aml1-excised MLL-ENL leukemic cells revealed accelerated growth rate because of enhanced cell-cycle progression and inhibition of apoptosis. (A) Growth rate of Aml1-excised leukemic cells in liquid medium was compared with controls. Data are mean ± SD. (B-C) Cell-cycle analyses of leukemic cells by PI. (B) Representative histograms are shown. (C) Percentages of cells in S/G2/M phase (mean ± SD). (D) Percentages of apoptotic cells in each liquid medium (mean ± SD). *P < .05. We performed 3 independent experiments and confirmed that similar results were reproduced. Statistical significance was evaluated by unpaired t test.

Aml1-excised MLL-ENL leukemic cells revealed accelerated growth rate because of enhanced cell-cycle progression and inhibition of apoptosis. (A) Growth rate of Aml1-excised leukemic cells in liquid medium was compared with controls. Data are mean ± SD. (B-C) Cell-cycle analyses of leukemic cells by PI. (B) Representative histograms are shown. (C) Percentages of cells in S/G2/M phase (mean ± SD). (D) Percentages of apoptotic cells in each liquid medium (mean ± SD). *P < .05. We performed 3 independent experiments and confirmed that similar results were reproduced. Statistical significance was evaluated by unpaired t test.

Decreased expression of cell cycle– and apoptosis-related genes in Aml1-excised leukemia cell. (A) Expression analyses of p19ARF, p53, Bax, and p21CIP1 by quantitative real-time PCR. The expression of each mRNA, normalized to that of Gapdh, is shown as the ratio to that of the normal BM mononuclear cells. (B) Intracellular staining of p53 in MLL-ENL leukemic cells was detected by flow cytometry. Representative histograms are shown. (Left) Staining with AlexaFluor-647–conjugated IgG1 isotype control antibodies. (Right) Staining with AlexaFluor-647–conjugated anti-p53 antibodies. Expression analyses of (C) Meis1 and Hoxa genes and (D) Bmi1 and p16INK4A by quantitative real-time PCR. Error bars represent SD. *P < .05. We performed 3 independent experiments and confirmed that similar results were reproduced. Statistical significance was evaluated by unpaired t test.

Decreased expression of cell cycle– and apoptosis-related genes in Aml1-excised leukemia cell. (A) Expression analyses of p19ARF, p53, Bax, and p21CIP1 by quantitative real-time PCR. The expression of each mRNA, normalized to that of Gapdh, is shown as the ratio to that of the normal BM mononuclear cells. (B) Intracellular staining of p53 in MLL-ENL leukemic cells was detected by flow cytometry. Representative histograms are shown. (Left) Staining with AlexaFluor-647–conjugated IgG1 isotype control antibodies. (Right) Staining with AlexaFluor-647–conjugated anti-p53 antibodies. Expression analyses of (C) Meis1 and Hoxa genes and (D) Bmi1 and p16INK4A by quantitative real-time PCR. Error bars represent SD. *P < .05. We performed 3 independent experiments and confirmed that similar results were reproduced. Statistical significance was evaluated by unpaired t test.

It was reported that loss of AML1 in mouse BM cells induces the enhanced expression of the Polycomb gene Bmi-1 and an increase in the stem/progenitor cells because of suppression of apoptosis.30 Bmi-1, which is highly expressed in HSCs, critically suppresses the expression of p19ARF and p16Ink4a in the regulation of hematopoietic cell proliferation.31 Therefore, down-regulation of p19ARF may be a consequence of Bmi-1 up-regulation by loss of AML1. To explore this possibility, we determined the expression of Bmi-1 in Aml1-excised MLL-ENL–transduced cells and found that there was no significant change in Bmi-1 expression, suggesting that p19ARF down-regulation is independent of Bmi-1. Consistently, the expression of p16Ink4a, another target gene of Bmi-1, is also unaffected by loss of AML1 (Figure 5D).

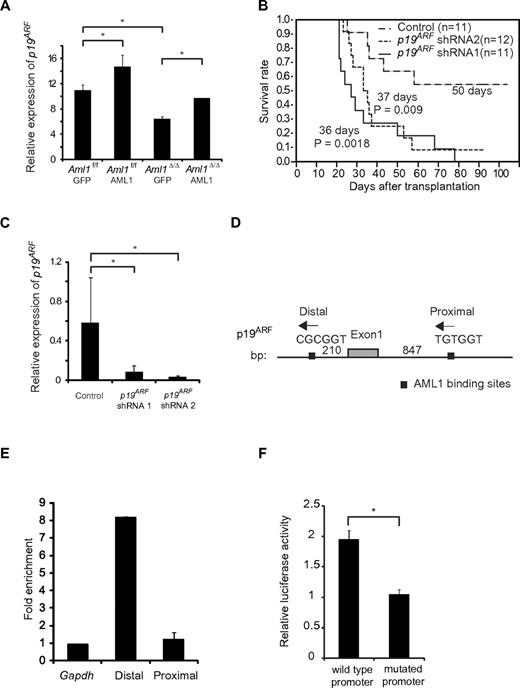

Transcriptional regulation of p19ARF by AML1 in MLL-ENL leukemic cells

It has been reported that overexpression of AML1 up-regulates the expression of P14ARF (human homolog of murine p19ARF), whereas AML1-ETO, a chimeric protein that exerts a dominant-negative effect over normal AML1, down-regulates its expression by directly binding to the promoter.20 Because p19ARF affects cell cycle and apoptosis by regulating p53, Bax, and p21CIP1, we hypothesized that p19ARF is a critical effector in the AML1-mediated regulation of MLL-ENL leukemia. To test this, we expressed AML1 in Aml1-excised MLL-ENL leukemic cells and evaluated whether p19ARF is expressed in an AML1 dose-dependent manner. We collected MLL-ENL leukemic cells and transduced them with AML1. Forty-eight hours after transduction, we assessed the expression of p19ARF in these cells by real-time reverse-transcribed PCR. As shown in Figure 6A, overexpression of AML1 enhanced p19ARF expression in Aml1 intact MLL-ENL–transformed cells. Expression of p19ARF in Aml1-excised MLL-ENL cells is decreased compared with controls, and this reduction was rescued by restoration of AML1 to the level observed in Aml1 intact cells transduced with GFP (Figure 6A). p19ARF expression levels in this setting were higher than the results of primary leukemic cells (Figure 5A), probably because of additional retroviral transduction and in vitro culture. These results are consistent with the hypothesis that AML1 up-regulates the expression of p19ARF also in MLL-ENL leukemia.

Expression of p19ARF is regulated by AML1 in MLL-ENL leukemia. (A) Expression analyses of p19ARF in MLL-ENL leukemic cells. Aml1 intact or Aml1-excised MLL-ENL leukemic cells harvested from each spleen were transduced with GFP or AML1-GFP. Forty-eight hours later, expression levels of p19ARF were measured by quantitative real-time PCR. (B) Aml1 intact MLL-ENL leukemic cells were transduced with p19ARF shRNA or control shRNA and transplanted into secondary recipient mice. Survival curves of 12 mice from each group are shown. Comparison of survival curve was performed using log-rank test. (C) Expression levels of p19ARF in leukemic cells from secondary recipient mice were measured by quantitative real-time PCR. (D) Two AML1 binding sites located in the promoter of p19ARF are shown as indicated. (E) Chromatin immunoprecipitation analyses of AML1 for p19 ARF promoter region in MLL-ENL leukemic cells. Fold enrichment normalized to the control locus Gapdh was shown. (F) COS7 cells were cotransfected with expression vector for AML1 and wild-type or PEBP2-site mutated p19ARF promoter vector. The relative luciferase activity was calculated as the ratio of luciferase activity with AML1 expression to that without AML1 expression. All luciferase reporter assays were performed in duplicate in 2 independent experiments. Values and error bars represent the mean and the SD, respectively. *P < .05. We performed 3 independent experiments and confirmed that similar results were reproduced, except for panel B. Statistical significance was evaluated by unpaired t test.

Expression of p19ARF is regulated by AML1 in MLL-ENL leukemia. (A) Expression analyses of p19ARF in MLL-ENL leukemic cells. Aml1 intact or Aml1-excised MLL-ENL leukemic cells harvested from each spleen were transduced with GFP or AML1-GFP. Forty-eight hours later, expression levels of p19ARF were measured by quantitative real-time PCR. (B) Aml1 intact MLL-ENL leukemic cells were transduced with p19ARF shRNA or control shRNA and transplanted into secondary recipient mice. Survival curves of 12 mice from each group are shown. Comparison of survival curve was performed using log-rank test. (C) Expression levels of p19ARF in leukemic cells from secondary recipient mice were measured by quantitative real-time PCR. (D) Two AML1 binding sites located in the promoter of p19ARF are shown as indicated. (E) Chromatin immunoprecipitation analyses of AML1 for p19 ARF promoter region in MLL-ENL leukemic cells. Fold enrichment normalized to the control locus Gapdh was shown. (F) COS7 cells were cotransfected with expression vector for AML1 and wild-type or PEBP2-site mutated p19ARF promoter vector. The relative luciferase activity was calculated as the ratio of luciferase activity with AML1 expression to that without AML1 expression. All luciferase reporter assays were performed in duplicate in 2 independent experiments. Values and error bars represent the mean and the SD, respectively. *P < .05. We performed 3 independent experiments and confirmed that similar results were reproduced, except for panel B. Statistical significance was evaluated by unpaired t test.

To determine a role of p19ARF in MLL-ENL leukemia in vivo, we tested whether down-regulation of p19ARF can accelerate the onset of MLL-ENL leukemia. We used short hairpin RNA (shRNA) to knock down the expression of p19ARF.25 We retrovirally transduced 3000 MLL-ENL leukemic cells with 2 types of p19ARF-directed shRNAs and injected them into sublethally irradiated secondary recipient mice. As shown in Figure 6B, only 42% of mice injected with leukemic cells transduced with control shRNAs developed leukemia. On the other hand, nearly all mice injected with leukemic cells transduced with p19ARF shRNAs developed leukemia in shorter latencies. p19ARF expression levels in cells of secondary leukemic mice were lower than those in primary leukemic mice (Figures 5A, 6C), possibly because of the development of secondary leukemia in vivo. We confirmed that expression of p19ARF was efficiently suppressed in leukemic cells obtained from p19ARF shRNAs-transduced MLL-ENL mice (Figure 6C). These results indicate that p19ARF down-regulation promotes the development of MLL-ENL leukemia, which supports the notion that p19ARF plays a critical role in the acceleration of MLL-ENL leukemia induced by loss of AML1.

To examine the direct binding of AML1 to the p19ARF promoter, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation assays. Two consensus AML1 binding sites (PEBP2 sites) were found in the p19ARF promoter (Figure 6D). The splenocytes from MLL-ENL leukemic mice were lysed after crosslinking by formaldehyde and eluted DNA was broken by sonication. Protein-DNA complexes were immunoprecipitated by the anti-AML1 antibody or normal rabbit IgG. Then we amplified the genomic DNA from this solution using the primers for the sequence containing the PEBP2 sites and found that the distal PEBP2 site of p19ARF promoter was significantly coprecipitated with AML1, suggesting that AML1 binds to the p19ARF promoter (Figure 6E). To ascertain whether the distal PEBP2 site contributes to AML1-dependent transactivation of the p19ARF promoter, we performed a luciferase reporter assay. We constructed a luciferase reporter containing the 0.6-kb fragment of the p19ARF promoter, and a mutant reporter containing the same promoter fragment in which the distal PEBP2 site (CGCGGT) was mutated (TTTTTT). COS-7 cells were cotransfected with an AML1 expression plasmid and these luciferase reporter plasmids. As shown in Figure 6F, AML1 activated the p19ARF promoter > 2-fold, whereas p19ARF-mutated promoter was not activated by AML1. These results indicate that AML1 regulates p19ARF transcription through binding to the distal PEBP2 site.

Discussion

The results presented here provide direct evidence that loss of AML1 induces the accelerated onset of MLL-ENL leukemia in mice because of enhanced proliferation of leukemic cells. Because additional mutations are required for the development of full-blown leukemia along with loss of AML1 function, their cooperation in leukemogenesis is of interest in understanding the molecular mechanisms of human leukemia. Recently, coexistence of MLL-PTD mutation and AML1 point mutation in AML with normal karyotype was reported,17 and the significance of this correlation in leukemogenesis is to be elucidated. In this regard, to understand the interaction between AML1 mutation and MLL leukemia, we explored accelerated leukemogenesis in Aml1-excised cells in vitro and in vivo using MLL-ENL fusion-induced mouse AML model. Our results indicate that AML1 acts as a tumor suppressor against the MLL-ENL oncogene, and loss of AML1 supports the development of leukemia via down-regulation of the genes related to the cell-cycle inhibition and apoptosis. Among them is p19ARF, which acts as a negative regulator of cellular proliferation upstream of the cascade, including p53 and p21CIP1. We found that AML1 activates transcription of p19ARF in MLL-ENL leukemic cells mainly through binding to distal consensus AML1 binding site (PEBP2 site) in the p19ARF promoter (Figure 6D) and that down-regulation of p19ARF induces the early onset of MLL-ENL leukemia, suggesting that p19ARF is a major target of AML1 in MLL-ENL leukemia (Figure 6A-B). These results suggest the function of AML1 as a tumor suppressor. Supporting our observation with the mouse model, down-regulation of p14ARF, a human homolog of mouse p19ARF, has also been reported in patients with human AML1-ETO leukemia.20 Several other mutations, such as ASXL132 and FLT333 mutations, are reported in AML with point mutations of AML1, and our results suggest a novel mechanistic basis also for these leukemias.

Motoda et al reported that loss of AML1 in mouse BM cells induces the enhanced expression of Bmi-1 and an increase in hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells because of suppression of apoptosis.30 They demonstrated that p19ARF expression was decreased in AML1-deficient BM cells and that the enhanced expression of p19ARF by N-Ras mutation was also decreased by loss of AML1. In their study, it is suggested that N-Ras mutation directly activates p19ARF and that AML1 indirectly induces the expression of p19ARF via down-regulation of Bmi-1. However, we found that the expression level of Bmi-1 is not changed by loss of AML1 in MLL-ENL leukemic cells and that p19ARF is directly regulated by AML1 (Figures 5D, 6E-F). Therefore, different molecular mechanisms that cooperate with loss of AML1 may exist in MLL-ENL and N-Ras leukemias, which remain to be elucidated.

In our study, we found that the expression level of p53 gene is also decreased in Aml1-excised MLL-ENL leukemic cells (Figure 5A). These cells expressed significantly less amount of p53 protein (Figure 5B). Therefore, loss of p53 is probably involved in the enhanced proliferation of AML1-deficient MLL-ENL leukemic cells, supporting our notion that the p19ARF-MDM2-p53 pathway may play a critical role in the acceleration of MLL-ENL leukemia induced by loss of AML1. However, it is well known that p19ARF blocks p53 degradation by binding to MDM2,34,35 and regulation of p53 transcription by p19ARF has not been reported. We confirmed that the expression levels of p53 did not increase in MLL-ENL leukemic cells by overexpression of p19ARF (data not shown). Therefore, it remains to be elucidated which of transcriptional regulation and posttranslational regulation is more important than the other for the reduction of p53 protein.

HSCs and LICs share several biologic properties, such as self-renewal capacities and an ability to differentiate into more differentiated cells. These similarities have led us to hypothesize that the number of LICs may be increased in Aml1-excised MLL-ENL leukemic cells as a consequence of HSC expansion by loss of AML1.36-42 However, the number of LICs was not affected by loss of AML1 in MLL-ENL mice, suggesting that promotion of MLL-related leukemia by loss of AML1 is not the result of the expansion of target population for leukemic transformation but mainly derived from the enhanced proliferation of MLL-ENL leukemic cells (Table 1). Given that MLL-ENL provides self-renewal capacities to the myeloid progenitors, including CMPs and GMPs, which are normally incapable of self-renewal,28 HSC expansion caused by loss of AML1 may not influence MLL-related leukemogenesis.

Aml1-excised transformed cells developed MLL-ENL leukemia earlier than Aml1 intact cells (Figures 2B, 3B). When Aml1 was excised from the MLL-ENL–transduced cells after engraftment in the individual mice, transplanted mice developed leukemia in as early as 21 days (Figure 3B); in contrast, the mice transplanted with MLL-ENL–transduced, Aml1-excised cells developed leukemia in 49.5 days after transplantation (Figure 2B). This may be because the transplanted cells in Figure 3B had already expanded and progressed to the leukemic or preleukemic state by MLL-ENL at the time of Aml1 excision and the Aml1 excision caused enhanced proliferation of the leukemic cells to shorten the latency to develop leukemia (Figure 3B).

Our study is the first report to reveal the molecular mechanism of leukemia acceleration caused by loss of AML1. Our results demonstrate that p19ARF is a key molecule for the proliferation of leukemic cells in AML1-related leukemia. Targeted therapy for aberrant p19ARF signaling pathway may be a novel therapeutic strategy against AML1-related leukemia.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr S. W. Hiebert (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN), Dr H. Nakauchi (IMS, Tokyo University, Tokyo, Japan), Dr T. Kitamura (IMS, Tokyo University, Tokyo, Japan), and Dr T. Nosaka (Mie University, Mie, Japan) for providing essential materials and instruments and M. Kobayashi, Y. Sawamoto, and Y. Shimamura for expert technical assistance.

This work was supported in part by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (grant KAKENHI 20790670).

Authorship

Contribution: N.N., Y.I., M.N., M.I., and M.K. designed the experiments and the study; N.N., S.A., Y.I., M.N., S.G., K.K., T.T., Y.K., M.I., and M.K. wrote the manuscript; N.N., S.A., Y.I., M.N., and M.I. performed experiments and collected and analyzed data; S.G., K.K., and T.T. provided technical advice and support; and M.K. supervised all of the experiments and data interpretation.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Mineo Kurokawa, Department of Hematology and Oncology, Graduate School of Medicine, University of Tokyo, 7-3-1 Hongo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo, Japan 113-8655; e-mail: kurokawa-tky@umin.ac.jp.

References

Author notes

N.N. and S.A. contributed equally to this study.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal