Abstract

The low incidence of CFU-F significantly complicates the isolation of homogeneous populations of mouse bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs), a common problem being contamination with hematopoietic cells. Taking advantage of burgeoning evidence demonstrating the perivascular location of stromal cell stem/progenitors, we hypothesized that a potential reason for the low yield of mouse BMSCs is the flushing of the marrow used to remove single-cell suspensions and the consequent destruction of the marrow vasculature, which may adversely affect recovery of BMSCs physically associated with the abluminal surface of blood vessels. Herein, we describe a simple methodology based on preparation and enzymatic disaggregation of intact marrow plugs, which yields distinct populations of both stromal and endothelial cells. The recovery of CFU-F obtained by pooling the product of each digestion (1631.8 + 199) reproducibly exceeds that obtained using the standard BM flushing technique (14.32 + 1.9) by at least 2 orders of magnitude (P < .001; N = 8) with an accompanying 113.95-fold enrichment of CFU-F frequency when plated at low oxygen (5%). Purified BMSC populations devoid of hematopoietic contamination are readily obtained by FACS at P0 and from freshly prepared single-cell suspensions. Furthermore, this population demonstrates robust multilineage differentiation using standard in vivo and in vitro bioassays.

Introduction

Within adult bone marrow, nonhematopoietic stromal cells (bone marrow stromal cells [BMSCs]) are known to contain a subpopulation of multipotent progenitor cells variously referred to as “skeletal” or “mesenchymal” stem cells.1-6 The differentiation potential of BMSCs and their capacity to contribute to tissue repair and regeneration, coupled with their unique immunosuppressive properties, have engendered considerable interest in the application of these cells to a rapidly burgeoning range of cellular therapies.7-11 Originally identified in the BM of rodents by Friedenstein et al,12 BMSCs have subsequently been isolated from many mammalian species, including human, rat, rhesus monkeys, dog, and pig through their preferential attachment to tissue culture plastic.13-17 Although the majority of published reports are based on studies using human BMSCs, it is notable that relatively few publications focus specifically on BMSCs derived from mouse BM. This has hindered progress not only in addressing fundamental questions regarding BMSCs biology through the use of genetic mouse models but also the preclinical testing of proposed therapeutic applications of BMSCs in the mouse.

Murine BMSCs have so far proven much more difficult to isolate from BM and to expand ex vivo than their counterparts from human BM.18-21 CFU-F are a rare population in the marrow of all mammalian species so far examined, but this is particularly so in the case of the mouse. Reported incidences of CFU-F are typically in the range of 0.3 to 2 per 1 000 00013,18,22 BM cells in C57BL/6 mice. Significant increases in the frequency of CFU-F (range, 35-115 of 1 000 000) have been demonstrated either by the use of irradiated feeder cells23 or after mechanical dissociation of the BM followed by trypsin digestion of remaining clumps, as described by Freidenstein et al.24 These methodologic improvements notwithstanding, the low incidence of CFU-F is a significant impediment to the isolation of murine BMSC populations using the standard method of plastic adherence, a common problem being contamination with hematopoietic cells, particularly macrophages. Although the contaminating hematopoietic cells are reduced by frequent and prolonged subculturing, this strategy comes with the attendant risk of proliferative exhaustion of the low numbers of founding progenitors typically used to initiate BMSC cultures from mouse BM, together with the possibility of altered differentiation or, at the other extreme, spontaneous transformation, which has been reported after long-term in vitro culture of mouse BMSCs.25

Although several methodologies have been described for isolating more homogeneous populations of murine BMSCs, including positive or negative selection and low plating densities,18-21,24,26,27,31 as well as crushing and digesting compact bone,28-30 the protocols are not readily standardized and as a consequence have not been widely adopted. Seeking to develop an improved methodology to harvest BMSCs from mice, we took advantage of burgeoning evidence demonstrating the perivascular localization of tissue-specific stem/progenitor cells in multiple tissues,32,33 in particular in BM.32 We hypothesized that a potential reason for the low yield of mouse BMSCs is the flushing of the marrow used to prepare single-cell suspensions, which, in destroying the marrow vasculature, may adversely affect recovery of stem/progenitor cells physically associated with the abluminal surface of blood vessels. In accord with this hypothesis, we describe a methodology based on preparation of BM “plugs” that maintains the integrity of the marrow vasculature. Subsequent sequential enzymatic digestion of BM plugs reproducibly yields CFU-F numbers more than 2 orders of magnitude higher than those achieved using the standard marrow flushing technique and simultaneously allows for the isolation of both stromal and endothelial cellular components of the BM.

Methods

Animals

Eight- to 12-week-old C57BL/6, BalbC, and NOD-SCID mice purchased from The Jackson Laboratory were bred in our animal facility and used as the source of BM tissue and transplant recipient animals. Animals were caged under standard conditions and fed a laboratory diet and acidified water ad libitum. Care and use of the laboratory animals was according to approved animal protocols/guidelines established by the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston Animal Welfare Committee.

Isolation of murine BM cells

Mice were killed by CO2 asphyxiation and cervical dislocation, femora and tibiae were excised, cleaned of attached muscle tissue, and stored on ice in harvest medium (PBS supplemented with 2% volume/volume FBS). To prepare BM cells by flushing, a 23-gauge needle (BD Biosciences) was inserted into the growth plate of femora or tibiae from which the epiphyses had been removed at the metaphysis below the marrow cavity and the BM removed by flushing in 5 mL of PFE (PBS supplemented with 2% FCS and 2mM EDTA). The resulting suspension was then triturated several times to break up clumps, drawn through a 20-gauge needle, and filtered through a 70-μm cell strainer (BD Biosciences).

To isolate BM plugs, the ends of the tibiae and femora were removed as in the previous paragraph, and a 1-mL syringe fitted with 23-gauge needle (BD Biosciences) containing ice-cold PFE was inserted into the growth plate and the BM plug gently expelled from the cut ends of the bones in 1 mL of PFE. BM plugs were transferred to 15-mL conical tubes (Falcon) containing a mixture of Collagenase Type I (3 mg/mL; Worthington) and Dispase (neutral protease, grade 2; 4 mg/mL; Roche Diagnostics) in PBS and incubated for 15 minutes at 37°C. After a brief vortex for 10 to 20 seconds on low setting, undigested BM was allowed to settle and BM cells in suspension transferred to a new tube containing 10 mL of PFE and placed on ice. This fraction is referred to as fraction 1. To the undigested BM tissue remaining after the first incubation was added additional collagenase/dispase solution and the process repeated an additional 2 times yielding fractions 2 and 3, respectively. Each fraction was then either filtered separately through a 70-μm cell strainer (BD Biosciences) or the 3 fractions were pooled before filtration (DBM). The cells were washed twice by centrifugation in PFE before plating under various conditions, as described in “CFU-assays.”

CFU-F assays

For assay of clonogenic fibroblast colony-forming cells (CFU-F), single-cell suspensions of BM cells prepared by the standard flushing methodology or DBM were plated in triplicate over a range of plating densities in 6-well plates (BD Biosciences) in 2 mL of complete growth medium composing α-MEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 20% (volume/volume) lot-selected FBS (Hyclone, Thermo Scientific), sodium pyruvate (1mM/mL, MP Biomedicals), gluta-MAX (2mM/mL), penicillin (100 U/mL), and streptomycin (100 μg/mL, all from Invitrogen). Cultures were incubated at 37°C in a humidified incubator at 5% CO2 and 5% O2 (low oxygen) for 72 hours washed with medium and refed with complete growth medium for an additional 11 days. On day 14, wells were briefly rinsed with PBS and then stained with 0.1% Toluidine blue in 4% formalin (both from Sigma-Aldrich) to allow enumeration of colonies. Only colonies containing more than 50 stromal cells were scored. In addition, for CFU-F assays from prospectively isolated BMSCs, clusters containing 10 to 50 cells were scored.

Establishment and characterization of primary cultures of DBM (P0 culture)

DBM from digestions 1 to 3 was also plated at nonclonal densities (1 × 106/cm2) to allow growth of both stromal cells and of vascular endothelial cells. Cells were plated on dishes or chamber slides (LabTek, Nunc) coated with fibronectin (Sigma-Aldrich) at 5 μg/cm2 in either α-MEM supplemented with 20% FBS or in EGM2-MV (Lonza Switzerland). Cultures were placed in a 37°C humidified incubator at 5% CO2 and 5% O2, washed at 72 hours, and maintained under these conditions with media changes every 3 days until attaining confluence and were designated P0 cultures.

Characterization of the cellular composition of P0 cultures

In situ staining.

P0 cultures established in chamber slides were placed on ice for 30 minutes and washed 3 times in ice-cold basal α-MEM (Invitrogen). Cultures were first incubated with purified rat mAbs, washed and revealed with donkey anti–rat Cy3 (1:500; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). After washing, Fc block was added for 20 minutes before the addition of flurochrome-conjugated rat mAb (supplemental Table 1, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article) for 30 minutes on ice. After mAb staining, cells were fixed in 4% PFA (Electron Microscopy Sciences) for 15 minutes at room temperature, washed 3 times in PBS, and then coverslipped in Prolong Gold containing 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Invitrogen). Imaging was performed on an inverted fluorescence microscope (Olympus BX51) and captured with an Olympus DP71 camera.

Flow cytometric analysis.

P0 cultures or cells at subsequent passages were detached at day 7 of culture by addition of 0.05% trypsin-EDTA (Invitrogen), washed in PFE, and filtered through a 40-μm cell strainer to obtain a single-cell suspension. Cells were resuspended in 100 μL of PFE and blocked in Fc block for 20 minutes on ice, followed by staining with fluorochrome-conjugated or isotype control antibodies on ice for 20 minutes. Before analysis, cells were resuspended in PFE containing 0.6 μg/mL DAPI (Invitrogen) and either analyzed on an LSR II (BD Biosciences) or subjected to FACS using a FACSAria II (BD Biosciences) fitted with a 100-μm nozzle and Blue Diode 488, HeNe 633, and UV 355 lasers to isolate stromal cells and/or vascular endothelial cells. For a complete list of antibodies used for FACS, see supplemental Table 1.

Prospective isolation of CFU-F from fresh BM

BM cells freshly prepared from DBM plugs as described in “Isolation of murine BM cells” were labeled with the biotinylated hematopoietic lineage antibody cocktail (supplemental Table 1) on ice for 20 minutes, washed, filtered, and then incubated with sheep anti–rat Dynal beads (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. After removal of bead bound lineage-positive cells, the unbound fraction was incubated in Fc block for 20 minutes on ice and stained with monoclonal antibodies as described in “Flow cytometric analysis.”

Marrow stromal cell differentiation assays

In vitro.

In vivo.

To determine their capacity to form bone in vivo, Lin−PDGFRα/β+ cells at P3 were collected by brief trypsinization, and 1.5 × 106 cells were resuspended in 50 μL α-MEM-20% growth media, loaded onto Gelfoam sponges (Baxter), and covered in a fibrin clot (Sigma-Aldrich) at 37°C. Scaffolds were then subcutaneously transplanted into 2- to 3-month-old NOD-SCID mice as described.37 At 12 weeks, mice were killed, scaffolds were recovered, fixed overnight in 10% buffered formalin at 4°C, and decalcified for 1 week in 10% EDTA, embedded in paraffin, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin or Masson trichrome according to standard procedures. Additional scaffolds were not decalcified and embedded in methyl methacrylate resin (Lawrence Bone Disease Program of Texas Bone Core, MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX) and sections stained using the von Kossa reaction and with Goldner trichrome.

Whole-mount immunofluorescence staining of BM plugs

Intact BM plugs prepared as in “Isolation of murine BM cells” were fixed in freshly prepared 2% paraformaldehyde for 10 minutes at room temperature and then washed 3 times in DPBS for 15 minutes. Using a scalpel, each plug was cut in 2, and each half transferred to a single well of a 96-well round bottom plate (BD Biosciences) for antibody staining. BM plugs were first incubated overnight at 4°C in blocking buffer composing DPBS with 3% BSA (Sigma-Aldrich), 2% FCS, 2% horse serum, and 2% normal donkey serum (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). BM plugs were then incubated overnight with gentle rocking at 4°C with purified anti-PDGFRα and anti-PDGFRβ antibodies or isotype controls. BM plugs were then washed throughout the following day at 4°C and incubated overnight with donkey anti–rat Cy3 diluted 1:500 in blocking buffer. Next, the samples were washed throughout the day in DBPS supplemented with 2% normal rat serum (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) and then incubated overnight with MECA32–Alexa 488 and VE-Cadherin–Alexa 488 or with rat IgG1 and IgG2a–Alexa 488 isotype controls. After washing, the BM plugs were counterstained with DRAQ5 (1:1000; Biostatus Limited) for 30 minutes at room temperature, transferred onto coverslips, and surrounded by several layers of 120-μm SecureSeal imaging spacers (Grace Biolabs) to provide a depth of approximately 300 to 500 μm and then immersed in prolong gold anti-fade mounting medium (Invitrogen). After applying a coverslip, specimens were inverted and allowed to cure overnight in the dark at room temperature before confocal imaging.

Characterization of vascular endothelial cells

Purified Lin−CD105brightPDGFRα/β− cells were cultured on fibronectin-coated wells in EGM2-MV. At passage 3, cells were plated into (LabTek) slides coated with fibronectin and cultures were analyzed for the presence of endothelial markers by in situ staining described in “In situ staining.” In addition, cells were plated at 70% confluency and the following day incubated with 10 μg/mL DiI-Ac-LDL (Biomedical Technologies) for 4 hours at 37°C. Cultures were washed 3 times in PBS and imaged on an inverted microscope for the presence of Ac-LDL uptake.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with SigmaStat Version 3.5 with significance being assigned to P < .05.

Results

Removal of an intact BM “plug” maintains structural integrity of the marrow vasculature

We hypothesized that the flushing of bones using a syringe and consequent mechanical destruction of the marrow vasculature, would lead to a diminution of the yield of BMSCs associated with these blood vessels. To test this hypothesis, we developed a procedure to expel intact “plugs” of BM from femora and tibiae by gentle flushing of the bones with media (Figure 1A). This methodology results in a near-complete removal of the marrow tissue leaving only a thin cortical rim in association with the endosteum (Figure 1B-C). Histologic analysis of the plugs revealed a conservation of marrow structure comparable with that of BM in situ with a well-preserved vasculature, both arterioles and sinusoids (Figure 1B,D). This was further demonstrated by whole-mount staining of BM plugs (see “Whole-mount immurofluorescence staining of BM plugs”) with a combination of the endothelial cell-reactive antibodies MECA32 and VE-Cadherin, which revealed a well-organized vascular network throughout the marrow (Figure 1E).

BM plug isolation and histologic assessment of intact vascular structures in BM plugs. (A) Representative images of denuded bones, removal of metaphysis, and isolated intact BM plug. (B-D) Resin-embedded sections of BM plugs (B,D) and remaining bone tissue (mid-diaphysis; C) after removal of marrow plug were sectioned as 5-μm-thick longitudinal sections and stained with hematoxylin and eosin, demonstrating intact vascular structures. (E) Whole-mount image of BM plug stained with a combination of the endothelial cell-reactive antibodies MECA32 and VE-Cadherin reveals a well-organized vascular reticulum throughout the marrow. BM plugs were stained with DRAQ5 to provide a nuclear counterstain and then immersed in prolong gold anti-fade mounting medium (Invitrogen). After applying a glass coverslip and sealing with nail hardener, specimens were inverted and allowed to cure overnight in the dark at room temperature before confocal imaging. Images were collected using 63× oil immersion objective of a Leica TCS SP5 confocal microscope and processed with the Leica LAS AF lite Version 2.6.7266 software. Z-stacked images were collected in 0.2-μm slices at depths of 15 to 25 μm with a pinhole of 1 (×63).

BM plug isolation and histologic assessment of intact vascular structures in BM plugs. (A) Representative images of denuded bones, removal of metaphysis, and isolated intact BM plug. (B-D) Resin-embedded sections of BM plugs (B,D) and remaining bone tissue (mid-diaphysis; C) after removal of marrow plug were sectioned as 5-μm-thick longitudinal sections and stained with hematoxylin and eosin, demonstrating intact vascular structures. (E) Whole-mount image of BM plug stained with a combination of the endothelial cell-reactive antibodies MECA32 and VE-Cadherin reveals a well-organized vascular reticulum throughout the marrow. BM plugs were stained with DRAQ5 to provide a nuclear counterstain and then immersed in prolong gold anti-fade mounting medium (Invitrogen). After applying a glass coverslip and sealing with nail hardener, specimens were inverted and allowed to cure overnight in the dark at room temperature before confocal imaging. Images were collected using 63× oil immersion objective of a Leica TCS SP5 confocal microscope and processed with the Leica LAS AF lite Version 2.6.7266 software. Z-stacked images were collected in 0.2-μm slices at depths of 15 to 25 μm with a pinhole of 1 (×63).

We next attempted to reduce the marrow plug to a single-cell suspension in a manner that avoided mechanical dissociation, thereby preserving the integrity and viability of cells composing the marrow stromal-vascular fraction. We determined that 3 sequential digestions each of 15-minute duration in a combination of collagenase/dispase, each followed by brief vortexing, was sufficient to completely render the BM plug into a single-cell suspension. After the third incubation, only an acellular matrix remained from which no cells grew out in when explanted in culture (data not shown). As shown in Figure 2A, the total number of nucleated BM cells recovered by this sequential enzymatic dissociation of BM plugs was not significantly different from that obtained by the standard flushing technique.

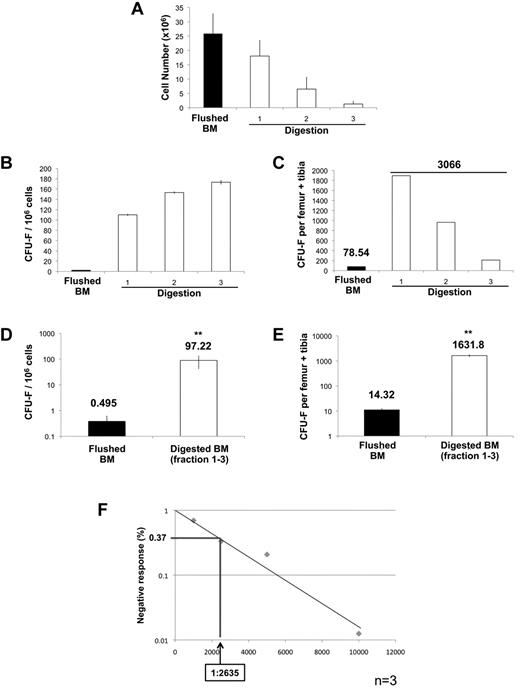

Evaluation of clonogenic stromal progenitor cells (CFU-F) recovered from sequential enzymatic disaggregation of BM plugs. (A) Average mononucleated cell yields obtained from either standard flushing methods or from each successive digestion (n = 4). (B) Incidence of CFU-F obtained from either standard flushing technique (5 × 106 mononuclear cells/well) or from each fraction of digested marrow plugs (2.5 × 105 mononuclear cells/well) plated in triplicate. (C) Recovery of CFU-F from flushed BM and each fraction of DBM calculated per femur-tibia pair. (D) Incidence of CFU-F obtained from flushed BM versus the pool of DBM fractions (1-3; n = 8). (E) Recovery of CFU-F from flushed BM and the pool of DBM fractions (1-3) calculated per femur-tibia pair. Only colonies containing more than 50 stromal cells are scored. CFU-F data are presented both as incidence of clonogenic cells (CFU-F/1 × 106 mononuclear cells) and as the total number of CFU-F recovered from a given number of bones (CFU-F per total nucleated cells). (F) CFU-F incidence quantified by limit dilution analysis. Limit dilution assays were performed by plating BM mononuclear cells at various doses (500, 1000, 2500, 5000, and 10 000 cells/well in 24-well plates) with 24 replicates per dilution (n = 3). Plates were scored and negative wells enumerated. Data were analyzed with L-Calc 1.1.1 software (StemCell Technologies) and plotted as a negative linear relationship to identify the frequency of colony-forming cells. Data are mean ± SD. Statistical analysis of CFU-F incidence was performed with SigmaStat Version 3.5.

Evaluation of clonogenic stromal progenitor cells (CFU-F) recovered from sequential enzymatic disaggregation of BM plugs. (A) Average mononucleated cell yields obtained from either standard flushing methods or from each successive digestion (n = 4). (B) Incidence of CFU-F obtained from either standard flushing technique (5 × 106 mononuclear cells/well) or from each fraction of digested marrow plugs (2.5 × 105 mononuclear cells/well) plated in triplicate. (C) Recovery of CFU-F from flushed BM and each fraction of DBM calculated per femur-tibia pair. (D) Incidence of CFU-F obtained from flushed BM versus the pool of DBM fractions (1-3; n = 8). (E) Recovery of CFU-F from flushed BM and the pool of DBM fractions (1-3) calculated per femur-tibia pair. Only colonies containing more than 50 stromal cells are scored. CFU-F data are presented both as incidence of clonogenic cells (CFU-F/1 × 106 mononuclear cells) and as the total number of CFU-F recovered from a given number of bones (CFU-F per total nucleated cells). (F) CFU-F incidence quantified by limit dilution analysis. Limit dilution assays were performed by plating BM mononuclear cells at various doses (500, 1000, 2500, 5000, and 10 000 cells/well in 24-well plates) with 24 replicates per dilution (n = 3). Plates were scored and negative wells enumerated. Data were analyzed with L-Calc 1.1.1 software (StemCell Technologies) and plotted as a negative linear relationship to identify the frequency of colony-forming cells. Data are mean ± SD. Statistical analysis of CFU-F incidence was performed with SigmaStat Version 3.5.

Sequential enzymatic disaggregation of BM plugs markedly enhances the recovery of CFU-F

Comparison of the content of CFU-F in BM cell preparations obtained by flushing of bones versus that obtained using sequential enzymatic disaggregation of BM plugs (DBM) demonstrated recovery of CFU-F in all 3 of the sequential digests with slightly higher colony-forming efficiency (CFE) in fractions 2 and 3 than in the first fraction (Figure 2B). Of note, the CFE of CFU-F was between 25- and 40-fold higher (depending on the fraction) than that detected in the equivalent number of BM cells obtained by flushing. When normalized to the total number of BM cells recovered in each sequential digest, approximately two-thirds of CFU-F (62%) were isolated in the first digest with progressively fewer in digests 2 (31.4%) and 3 (6.9%), respectively (Figure 2C). In subsequent experiments, we opted to pool the BM cells obtained from each of the 3 sequential digests based on the pool being representative of the stromal progenitor population of the marrow as a whole. Data from 8 independent experiments demonstrate a CFE in the pooled DBM of approximately 1/104, representing a 196.4-fold increase in the incidence of CFU-F compared with that in flushed BM (Figure 2D). This was reflected in a corresponding 113.95-fold enhancement in the recovery of CFU-F yielded by the new technique compared with the standard flushing methodology (Figure 2E). In 3 of these experiments, we also measured CFU-F frequency by limit dilution assay (Figure 2F). These analyses yielded a frequency of CFU-F in the pooled digests 1 to 3 of 1/2635 BM cells, which, based on the sum of the number of cells isolated, corresponds to a total of 9087.7 + 2996 CFU-F per femur/tibia pair, a recovery approximately 634-fold higher than obtained through flushing of the same 2 bones. It should be noted that all of these assays were performed at reduced oxygen concentration (5% O2) based on the approximately 30-fold higher CFE of CFU-F under hypoxia compared with normoxia (20% O2; supplemental Figure 1). Collectively, these data demonstrate that the methodology described herein significantly enhances both the incidence and recovery of CFU-F compared with that afforded by assay of flushed BM.

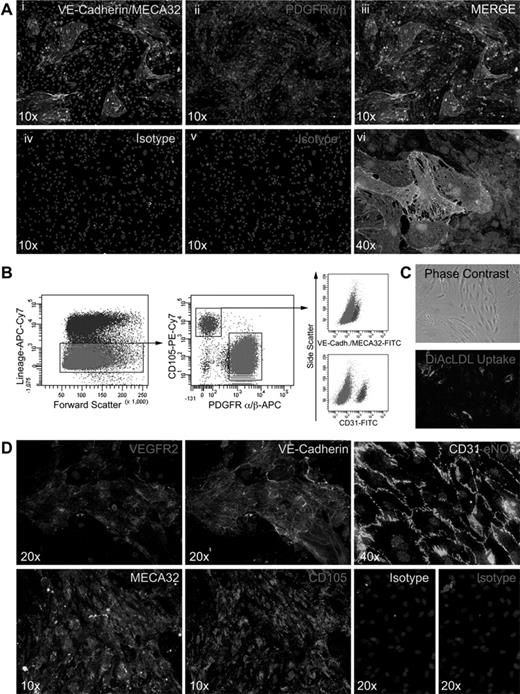

Primary cultures derived from enzymatically dissociated BM plugs contain the marrow stromal-vascular fraction

Because the preparation of BM plugs preserves the structural integrity of the marrow vasculature (Figure 1E), we reasoned that primary BM cultures established from DBM should contain populations of both stromal cells and vascular endothelial cells. For these experiments, DBM was plated at high cell density (1 × 106 nucleated cells/cm2) in α-MEM supplemented with FCS or EGM2-MV medium to promote growth of stromal and endothelial cell constituents, respectively. Such primary (P0) cultures typically reached confluence in 5 to 7 days at which time in situ immunofluorescent staining was performed using antibodies to PDGFRα and PDGFRβ to identify stromal cells and a combination of antibodies to pan-endothelial markers, CD31, VE-Cadherin, and MECA32. This staining demonstrated what appeared to be islands of endothelial cells dispersed among a monolayer of PDGFRαβ+ stromal cells (Figure 3A). The number and size of endothelial islands appeared substantially greater in EGM2-MV medium than in α-MEM/FCS (data not shown). Notably, a corresponding analysis of P0 cultures established under identical conditions from BM cells isolated by flushing failed to identify CD31/VE-Cadherin/MECA32+ endothelial cells and, as anticipated, revealed colonies (CFU-F) of PDGFRαβ+ stromal cells (data not shown).

Immunostaining of P0 cultures and isolation and characterization of BM vascular endothelial cells. (Ai-vi) In situ staining of P0 cultures plated on fibronectin-coated chamber slides (LabTek; Nunc), cultured in EGM-2MV for 5 to 7 days. Vascular endothelial cells were identified by staining with a combination of VE-Cadherin–Alexa 488 and MECA32–Alexa 488 antibodies, and stromal cells were stained with rat anti–mouse PDGFRα/β (purified) antibodies and revealed with donkey anti–rat Cy3 and counterstained with DAPI. IgG2a and IgG1 isotypes were used for controls (Aiv-v). (B) Gating strategy for FACS purification of vascular endothelial cells from P0 cultures plated on fibronectin-coated 10-cm2 dishes at 1 × 106 mononuclear cells/cm2 and cultured in EGM-2MV for 5 to 7 days and stained as described in “In situ staining.” (C) Phase-contrast images of Lin−CD105BRIGHTPDGFRαβ− cells at passage 3 and functional analysis of DiI-Ac-LDL uptake. (D) In situ staining of Lin−CD105BRIGHTPDGFRαβ− cells at passage 3 for endothelial markers, including VEGFR2 (Di), VE-Cadherin (Dii), CD31 and eNOS (Diii), MECA32 (Div), CD105 (Dv), and isotype controls (Dvi-vii). Nuclei were counterstained DAPI. Imaging was performed on an inverted fluorescence microscope (Olympus BX51) at both ×10 and ×40 (original magnification) and captured with an Olympus DP71 camera.

Immunostaining of P0 cultures and isolation and characterization of BM vascular endothelial cells. (Ai-vi) In situ staining of P0 cultures plated on fibronectin-coated chamber slides (LabTek; Nunc), cultured in EGM-2MV for 5 to 7 days. Vascular endothelial cells were identified by staining with a combination of VE-Cadherin–Alexa 488 and MECA32–Alexa 488 antibodies, and stromal cells were stained with rat anti–mouse PDGFRα/β (purified) antibodies and revealed with donkey anti–rat Cy3 and counterstained with DAPI. IgG2a and IgG1 isotypes were used for controls (Aiv-v). (B) Gating strategy for FACS purification of vascular endothelial cells from P0 cultures plated on fibronectin-coated 10-cm2 dishes at 1 × 106 mononuclear cells/cm2 and cultured in EGM-2MV for 5 to 7 days and stained as described in “In situ staining.” (C) Phase-contrast images of Lin−CD105BRIGHTPDGFRαβ− cells at passage 3 and functional analysis of DiI-Ac-LDL uptake. (D) In situ staining of Lin−CD105BRIGHTPDGFRαβ− cells at passage 3 for endothelial markers, including VEGFR2 (Di), VE-Cadherin (Dii), CD31 and eNOS (Diii), MECA32 (Div), CD105 (Dv), and isotype controls (Dvi-vii). Nuclei were counterstained DAPI. Imaging was performed on an inverted fluorescence microscope (Olympus BX51) at both ×10 and ×40 (original magnification) and captured with an Olympus DP71 camera.

To quantify the incidence of both stromal-vascular components, flow cytometric analysis was performed on trypsin-detached cells from P0 cultures established in EGM2-MV. Hematopoietic lineage-negative cells represented (51.38% + 16.4%; n = 5) of the adherent population of which 64.68% + 15.4% demonstrated staining with the combination of antibodies to PDGFRα and PDGFRβ and exhibited a bimodal expression for CD105+ (45.2% + 2.7%) and CD105low/− (43.5% + 3.6%), thereby identifying them as stromal cells. An additional 15.66% + 10.6% exhibited the phenotypic properties of vascular endothelial cells, lacking expression of PDGFRαβ, demonstrating high levels of expression of CD105 and uniform staining for CD31, VE-Cadherin, and MECA32 (Figure 3B). The remaining 20% of hematopoietic lineage negative cells within P0 cultures did not attach to tissue culture plastic and appeared to be erythroid precursor cells based on morphology (data not shown). After isolation of Lin−PDGFRαβ−CD105bright cells by FACS and serial passaging in EGM2-MV, the population demonstrated uniform uptake of DiI-Ac-LDL (Figure 3C) and continued to express the aforementioned vascular endothelial markers in addition to eNOS (Figure 3Di-v).

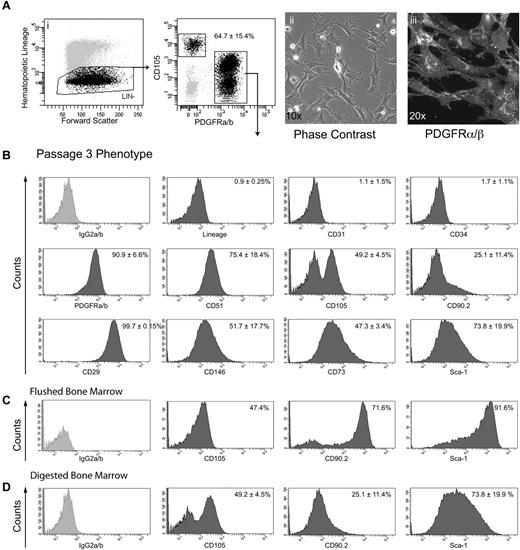

Lin−/PDGFRαβ+ cells exhibit the phenotypic and functional properties of BMSCs

To further characterize the stromal cells derived from DBM, FACS was used to isolate Lin−PDGFRαβ+ cells from P0 cultures (Figure 4Ai). After plating in α-MEM supplemented with 20% FBS, these cells exhibited a typical polygonal stromal morphology at low cell density (Figure 4Aii) and homogeneously expressed PDGFRαβ, both by in situ staining (Figure 4Aiii) and by flow cytometric analysis at passage 3 (Figure 4B). A broad range of cell surface markers previously used to characterize stem/progenitor cells in a variety of connective tissues, including BM, in vitro were also exhibited, including CD29, CD51, CD73, CD105, CD146, and Sca-1 (Figure 4B). Notably, when the cell surface phenotype of stromal cells obtained by the current sequential digestion methodology (Figure 4D) was compared with that displayed by cells generated from flushed BM (Figure 4C) at the same passage history, marked differences were observed in the expression of CD90, Sca-1, and CD105 (Figure 4C-D).

Isolation and phenotypic analysis of long-term cultured Lin−PDGFRαβ+ BMSCs. (Ai-ii) Representative gating strategy of viable cells for FACS isolation of Lin−PDGFRαβ+ cells from P0 cultures. (Aii-iii) Phase-contrast image and PDGFRβ immunostaining at passage 3. (B) FACS analysis of MSC markers in cultures of passage 3 Lin−PDGFRαβ+ cells (n = 3). FACS analysis demonstrating phenotypic differences between flushed BM (C) and DBM cells (D). FACS data were collected on BD LSR II, and postacquisition analysis was performed with BD FACS Diva Version 6.1.3. Data are mean ± SD.

Isolation and phenotypic analysis of long-term cultured Lin−PDGFRαβ+ BMSCs. (Ai-ii) Representative gating strategy of viable cells for FACS isolation of Lin−PDGFRαβ+ cells from P0 cultures. (Aii-iii) Phase-contrast image and PDGFRβ immunostaining at passage 3. (B) FACS analysis of MSC markers in cultures of passage 3 Lin−PDGFRαβ+ cells (n = 3). FACS analysis demonstrating phenotypic differences between flushed BM (C) and DBM cells (D). FACS data were collected on BD LSR II, and postacquisition analysis was performed with BD FACS Diva Version 6.1.3. Data are mean ± SD.

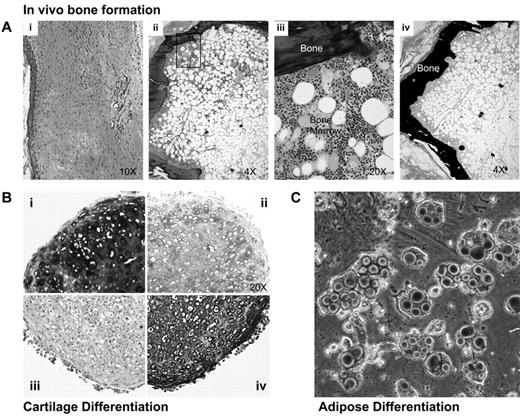

The multilineage differentiation potential of Lin−PDGFRαβ+ cells at passage 3 was analyzed using both in vivo and in vitro differentiation assays. To test their capacity to form bone in vivo, cells were loaded onto Gelfoam scaffolds and implanted subcutaneously by blunt dissection into NOD-SCID mice. Histologic analysis at 12 weeks after implant revealed an outer core of mineralized bone tissue surrounding an adipose cell-rich BM tissue containing small clustered areas of active hematopoiesis (Figure 5Aii-iv), whereas only fibrous connective tissue was observed in mice transplanted with empty scaffolds (Figures 5Ai). Standard micromass pellet cultures demonstrated robust chondrogenic activity of Lin−PDGFRαβ+ cells as evidenced by collagen type II expression and the deposition of a sulphated proteoglycan-rich ECM revealed by staining with Toluidine blue and Alcian blue (Figure 5B). Finally, after culture in the presence of PPARγ agonists, Lin−PDGFRαβ+ cells exhibited prominent adipogenic differentiation as revealed by Oil Red O staining (Figure 5C).

Multilineage differentiation capacity of Lin−PDGFRαβ+ BMSCs. (Ai-iv) Histology of subcutaneous transplants of either empty scaffolds (Ai) or Lin−PDGFRαβ+ MSC (Aii-iv). Gelfoam scaffolds loaded with Lin−PDGFRαβ+ MSCs were either decalcified and embedded in paraffin for hematoxylin and eosin staining (Aii-iii) or nondecalcified and embedded in methylmethacrylate resin for Von Kossa staining (Aiv). (B) Three-dimensional pellet cultures of Lin−PDGFRαβ+ MSCs embedded in paraffin and stained with Toluidine blue (0.1% weight/volume; Bi), Alcian blue (Bii), collagen type II (Biv), and mouse IgG1 isotpe (Biii). (C) Oil red O staining of Lin−PDGFRαβ+ MSCs after adipogenic differentiation for 14 days.

Multilineage differentiation capacity of Lin−PDGFRαβ+ BMSCs. (Ai-iv) Histology of subcutaneous transplants of either empty scaffolds (Ai) or Lin−PDGFRαβ+ MSC (Aii-iv). Gelfoam scaffolds loaded with Lin−PDGFRαβ+ MSCs were either decalcified and embedded in paraffin for hematoxylin and eosin staining (Aii-iii) or nondecalcified and embedded in methylmethacrylate resin for Von Kossa staining (Aiv). (B) Three-dimensional pellet cultures of Lin−PDGFRαβ+ MSCs embedded in paraffin and stained with Toluidine blue (0.1% weight/volume; Bi), Alcian blue (Bii), collagen type II (Biv), and mouse IgG1 isotpe (Biii). (C) Oil red O staining of Lin−PDGFRαβ+ MSCs after adipogenic differentiation for 14 days.

Prospective isolation of stromal cell precursors from freshly prepared enzymatically dissagregated BM tissue

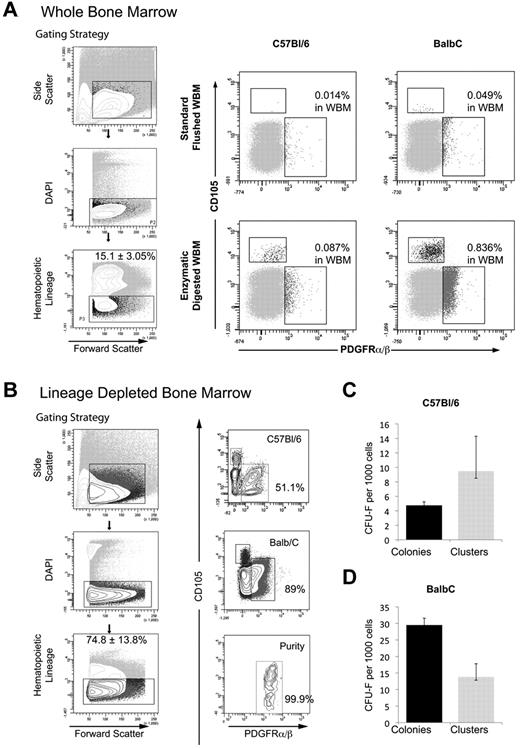

Collectively, the data in Figure 5 demonstrates the utility of sequential enzymatic digestion of BM as a means to isolate with high yield, a phenotypically defined population of marrow stromal cells with the functional properties of stem/progenitor cells in vitro and in vivo. Given that this population of Lin−PDGFRαβ+ cells is identified after a period of in vitro culture, we investigated whether enzymatic dissagregation would also facilitate isolation of cells with the same phenotype from fresh BM. DBM was prepared as described in “Isolation of murine BM cells,” depleted of hematopoietic lineage-expressing cells using Dynalbeads, and the resulting Lin-depleted DBM stained with a combination of anti-PDGFRα and PDGFRβ together with antibody to CD105. Flow cytometric analysis of C57Bl/6 DBM before depletion revealed a discrete population of Lin−PDGFRα/β+ cells representing 0.087% + 0.014% of cells in whole BM (Figure 6A) that increased to 51.5% of Lin− cells in lineage-depleted DBM (Figure 6B). A corresponding analysis performed on DBM from BALB/c mice, a strain reported to contain a significantly higher content of CFU-F,18 demonstrated a significant increase in the incidence of Lin−PDGFRα/β+ cells (0.84% + 0.64%) in whole BM (Figure 6A), rising to 89% in Lin− BM after immunomagnetic bead depletion (Figure 6B). The Lin−PDGFRα/β+ population isolated by FACS from C57Bl/6 and BALB/c DBM demonstrated a CFE for CFU-F of 0.475% and 2.95%, respectively (Figure 6C-D), whereas Lin−PDGFRα/β− cells from both mouse strains were devoid of CFU-F (data not shown).

Prospective isolation of Lin−PDGFRαβ+ clonogenic progenitors from DBM. (A) Gating strategy (left panel) and FACS analysis of whole BM from C57Bl/6 and BALB/c mice demonstrating the frequency of Lin−PDGFRαβ+ BMSCs obtained from either standard flushing or sequential enzymatic disaggregation of BM plugs. (B) Gating strategy (left panel) for prospective isolation of Lin−PDGFRαβ+ population from C57Bl/6 and BALB/c inbred mouse strains. (C-D) Incidence of CFU-F from prospective isolation of Lin−PDGFRαβ+ BMSCs from C57Bl/6 and BALB/c mice. Colonies > 50 stromal cells; clusters represent 10 to 49 stromal cells.

Prospective isolation of Lin−PDGFRαβ+ clonogenic progenitors from DBM. (A) Gating strategy (left panel) and FACS analysis of whole BM from C57Bl/6 and BALB/c mice demonstrating the frequency of Lin−PDGFRαβ+ BMSCs obtained from either standard flushing or sequential enzymatic disaggregation of BM plugs. (B) Gating strategy (left panel) for prospective isolation of Lin−PDGFRαβ+ population from C57Bl/6 and BALB/c inbred mouse strains. (C-D) Incidence of CFU-F from prospective isolation of Lin−PDGFRαβ+ BMSCs from C57Bl/6 and BALB/c mice. Colonies > 50 stromal cells; clusters represent 10 to 49 stromal cells.

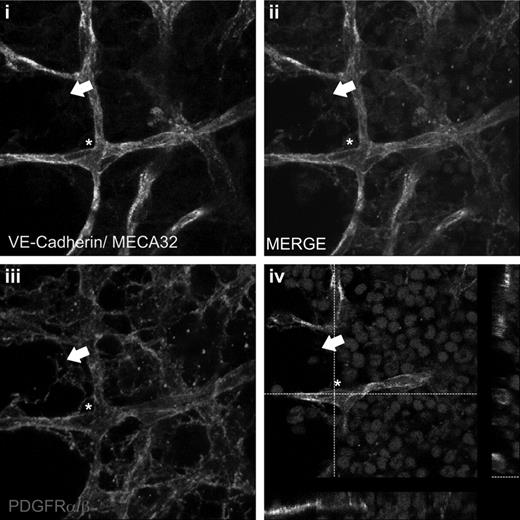

Finally, having identified a cell surface phenotype that allows prospective isolation of CFU-F, we next attempted to use this same combination of markers to define their anatomic distribution within the BM. Whole-mount staining of intact BM plugs revealed an extensive network of PDGFRα/β+ cells, some of which were directly apposed to the abluminal surface of the VE-Cadherin+MECA32+ blood vessels, whereas others formed a complex reticulum within the intersinusoidal areas of the BM (Figure 7).

PDGFRαβ+ stromal cells are localized to perivascular and intersinusoidal regions in vivo. Whole-mount staining of BM plugs. Vascular endothelial cells were identified with VE-Cadherin–Alexa 488 and MECA32–Alexa 488 antibodies (A), and stromal cells were identified with PDGFRα/β antibodies and revealed with donkey anti–rat Cy3 (C). Nuclei were counterstained with DRAQ5. Z-stack merged image (B) and single-step merged image identifying perivascular (white asterisk) and intersinusoidal (white arrow) localization. Images were collected using a 63× oil immersion objective on zoom factor of 3 with a Leica TCS SP5 confocal microscope and processed with the Leica LAS AF lite Version 2.6.7266 software. Z-stacked images were collected in 0.2-μm slices at depths of 15 to 25 μm with a pinhole of 1.

PDGFRαβ+ stromal cells are localized to perivascular and intersinusoidal regions in vivo. Whole-mount staining of BM plugs. Vascular endothelial cells were identified with VE-Cadherin–Alexa 488 and MECA32–Alexa 488 antibodies (A), and stromal cells were identified with PDGFRα/β antibodies and revealed with donkey anti–rat Cy3 (C). Nuclei were counterstained with DRAQ5. Z-stack merged image (B) and single-step merged image identifying perivascular (white asterisk) and intersinusoidal (white arrow) localization. Images were collected using a 63× oil immersion objective on zoom factor of 3 with a Leica TCS SP5 confocal microscope and processed with the Leica LAS AF lite Version 2.6.7266 software. Z-stacked images were collected in 0.2-μm slices at depths of 15 to 25 μm with a pinhole of 1.

Discussion

The derivation of murine BMSCs continues to represent a challenge to those investigators who seek to exploit the power of mouse genetic models to answer questions regarding the basic biology of BMSCs or who wish to conduct preclinical studies in the mouse as a means to test newly developed stromal stem/progenitor-based cellular therapies. The present study was designed to address one of the major factors contributing to the difficulty in establishing homogeneous cultures of murine BMSCs, namely, the low incidence of CFU-F in the BM, which varies between 0.3 and 2 CFU-F/ million BM cells (C57Bl/6) up to approximately 3 CFU-F per million (BALB/c) across various mouse strains.13,18,38 In accord with these data, in the current study, C57Bl/6 BM prepared by flushing and assayed under the conditions described in these previous reports contains 0.22-2.33 CFU-F per million cells. However, when BM cells were isolated by enzymatic disaggregation of BM plugs the frequency of CFU-F was increased to approximately 380 CFU-F per million cells. This dramatic improvement in the incidence and recovery of CFU-F was a consequence of several methodologic improvements, the first and most significant being the means by which BM cell suspensions were prepared before CFU-F assay. We demonstrate that the generation of plugs of marrow with a preserved microvasculature followed by sequential enzymatic disaggregation of the plugs consistently yielded CFU-F numbers at least 2 orders of magnitude greater than those obtained by the standard flushing technique. It will be noted that this approach is somewhat analogous to that used to isolate stem/progenitor cells from adipose tissue in which enzymatic digestion of the stromal-vascular fraction is required to release stem/progenitor cells from their association with blood vessels.39 The importance of the means by which BM is rendered into a single-cell suspension on the recovery of CFU-F was also recognized by Freidenstein et al who reported enhanced CFE when BM was prepared by mechanical dissociation followed by trypsin digestion of remaining clumps.24

Also contributing to the improved recovery of CFU-F in the current report is the establishment of the assays at low oxygen tension. CFU-F cultures initiated at 5% O2 demonstrated a 30-fold increase in CFE compared with those established under normoxia, findings in keeping with previous studies.40 Aside from their perivascular location,32,33,41 little is currently known about the molecular composition of the niche occupied by CFU-F in the BM in vivo, but these findings would suggest that stromal progenitors, like hematopoietic stem cells,42 occupy a hypoxic microenvironment. It should also be noted that the high plating efficiency of CFU-F demonstrated in these studies is occurring in the absence of exogenous mitogenic growth factors, such as FGF2 or feeder cells shown in previous reports,13,23,24 to be necessary for optimal CFE of CFU-F from mouse BM. Our data in no way exclude a role for accessory cells and their products in promoting the growth of CFU-F, and it will be of interest to determine whether the CFE reported here can be further improved after addition of feeder cells and/or growth factors and, moreover, to define the requirements of CFU-F isolated using the new methodology for growth in serum-free conditions.

Growth of the DBM cells at high cell density resulted in adherent cell layers containing both stromal cells and vascular endothelial cells, in addition to hematopoietic cells, thereby demonstrating the ability of this new methodology to facilitate isolation of the BM stromal-vascular fraction. From these primary cultures, we successfully isolated by FACS vascular endothelial cells and were able to serially passage these cells in vitro as a pure population. To our knowledge, this represents the first report demonstrating successful isolation and propagation of vascular endothelial cells from mouse BM, and we anticipate this finding will significantly advance studies of these relatively poorly characterized cells.

In the same primary cultures, Lin−/PDGFRα/β+ cells were shown to compose approximately 30% of adherent cells and on FACS, generated cultures of polygonal fibroblast-like cells, which expressed a range of cell surface markers previously ascribed19,20,26,30,43 to murine BMSCs, demonstrated robust multilineage differentiation in vitro, and gave rise to bone ossicles containing BM after ectopic transplantation. From the femora and tibiae of 5 mice prepared using the new methodology, we typically isolate by FACS between 1 million and 2 million stromal cells at P0 and up to 20 million by P3 over a 3-week time period. This compares with less than 1 million cells generated using the standard flush methodology at P3. Such cultures were difficult to passage beyond P3 in contrast to those cultures initiated from DBM, probably a consequence of senescence because of exhaustion of the proliferative capacity of the markedly lower numbers of CFU-F recovered in flushed BM.

Further, to these differences in cell generative potential, flow cytometric analysis of Lin−/PDGFRα/β+ cells prepared from flushed and DBM-derived cultures also revealed phenotypic differences. MSCs derived from flushed BM exhibited high levels of Sca-1 and abundant expression of Thy-1 on the majority of cells as described previously, whereas DBM-derived cells demonstrated 10-fold lower levels of Sca-1 and low level Thy-1 on only 25% of the population. In addition, CD105 demonstrated biomodal expression on DBM stem/progenitor cells with distinct CD105+ and CD105LOW/− populations in contrast to the flushed BMSCs in which only the CD105+ population was evident. Although the significance of this observation is as yet unclear, it is noteworthy that, in freshly prepared DBM, the Lin−/PDGFRα/β+ population also exhibits the same biomodal expression of CD105 (Figure 6). One interpretation, therefore, is that, although DBM allows isolation of both subpopulations of BMSCs, BM prepared by the standard flushing technique may bias toward the CD105+ subpopulation perhaps as a consequence of their selective survival during BM isolation or preferential outgrowth in vitro. Further studies will be required to explore the disparity in cell populations elicited by the 2 BM cell isolation methodologies.

An important advance described in the current studies was the successful prospective isolation of CFU-F from BM of adult wild-type mice. Previous reports used either fetal mice44 or were reliant on transgenic mice strains expressing stromal cell reporters.41,45 Lin−/PDGFRα/β+ cells were shown to contain the CFU-F activity in both C57Bl/6 and BALB/c mice, the increased frequency of this population in BALB/c mice correlating with a significant increase in CFU-F incidence in this strain, in agreement with previous studies.18 These data highlight the utility of this methodology and suggest its broad applicability to the isolation and quantitation of stromal progenitors across different strains of inbred mice. Finally, in accord with our hypothesis that the low yield of BMSCs achieved by flushing of BM reflects the loss of these cells associated with the marrow vasculature, whole-mount staining of BM plugs demonstrated Lin−/PDGFRα/β+ cells both in perivascular locations and as a network of BMSCs in intersinusoidal regions (Figure 7).

In conclusion, the novel approach to the isolation of CFU-F using DBM described herein markedly enhances, quantitatively and qualitatively, the isolation of cells composing the stromal tissue of murine BM. It is to be hoped these studies will ultimately contribute to a greater understanding of the role of stromal cell subpopulations in regulation of hematopoiesis, and will complement efforts currently underway in other laboratories based on the use of mouse models.41,45-47

This article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank David Haviland for assistance with FACS sorting, Sarah Amra for histology services, Michael Starbuck from the Lawrence Bone Disease Program of Texas Bone Core, MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX for the assistance with nondecalcified resin-embedded sections, and Zhengmei Mao for assistance with confocal microscopy.

Authorship

Contribution: C.S. designed the study, performed all experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; N.B. prepared the figures; and K.H. and P.J.S. designed the study, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Paul J. Simmons, Centre for Stem Cell Research, Institute of Molecular Medicine, University of Texas School of Medicine, 1825 Pressler, Houston, TX 77030; e-mail: paul.j.simmons@uth.tmc.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal