Abstract

Adult-type lympho-myeloid hematopoietic progenitors are first generated in the aorta-gonad-mesonephros region between days 27 and 40 of human embryonic development, but an elusive blood forming potential is present earlier in the underlying splanchnopleura. In the present study, we show that angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE, also known as CD143), a recently identified cell-surface marker of adult human hematopoietic stem cells, is already expressed in all presumptive and developing blood-forming tissues of the human embryo and fetus: para-aortic splanchnopleura, yolk sac, aorta-gonad-mesonephros, liver, and bone marrow (BM). Fetal liver and BM-derived CD34+ACE+ cells, but not CD34+ACE− cells, are endowed with long-term culture-initiating cell potential and sustain multilineage hematopoietic cell engraftment when transplanted into NOD/SCID mice. Furthermore, from 23-26 days of development, ACE expression characterizes rare CD34−CD45− cells concentrated in the hemogenic portion of the para-aortic splanchnopleura. ACE+ cells sorted from the splanchnopleura generated colonies of hematopoietic cells more than 40 times more frequently than ACE− cells. These data suggest that, in addition to being a marker of adult human hematopoietic stem cells, ACE identifies embryonic mesodermal precursors responsible for definitive hematopoiesis, and we propose that this enzyme is involved in the regulation of human blood formation.

Introduction

The mammalian blood-forming system sustains multiple lineages of short-lived cells throughout life, a process preserved by a small cohort of multipotent hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs). In humans, as in all higher vertebrates, at least 2 different sites participate in the generation of blood during embryonic development: the extraembryonic yolk sac (YS) and the aorta-gonad-mesonephros (AGM) region inside the embryo.1-3 Hematopoietic cells are first generated in human YS blood islands during the third week of development.4 In all species, YS hematopoiesis is ephemeral: hematopoietic progenitors with restricted development ability rapidly differentiate toward erythroid and myeloid lineages.4-7 Once blood circulates, YS-derived blood cells enter the embryo and colonize the hepatic bud, starting from the 23rd day of human gestation.4 Intraembryonic hematopoiesis is initiated during the fourth week as clusters of CD34+CD45+ cells appearing on the ventral wall of the dorsal aorta.8 Even though a recent study suggested the presence of B-lymphoid ability inside the YS in mice,9 it is generally accepted that in the human embryo, adult-type hematopoietic progenitors that also exhibit B- and T-lymphoid potentials are generated only in the AGM region.10 Furthermore, the splanchnopleura (Sp), the presumptive hemogenic aorta, is already hematopoietic at earlier stages of development.10,11 Indeed, the pre-circulation human Sp cultured over a layer of stromal cells initiates long-term hematopoiesis in vitro.10 Because of the close developmental relationship that exists between emerging endothelial and hematopoietic cells, both in the extra-embryonic YS and inside the embryo, a direct ontogenic link between these 2 cell lineages has long been emphasized. However, whereas evidence exists that vitelline hematopoiesis stems from hemangioblasts, the ancestral progenitors giving rise to both vascular endothelium and blood-forming cells in the AGM remain unknown. In the avian, murine, and human embryo, CD45− cells included in the ventral endothelium of the dorsal aorta display hemogenic activity and are able to give rise to hematopoietic progenitors.12-15 Subaortic patches located below the aortic floor of the mouse embryo may also be involved in intraembryonic hematopoietic generation from nonendothelial lineage precursor cells.7,16 Using a mAb (BB9) that was raised initially to human BM stromal cells17 but turned out to recognize the somatic isoform of the angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE), we showed previously that ACE/CD143 is a cell-surface marker of postnatal human HSCs18 and, indeed, ACE/CD143+ HSCs have been found to be present in the umbilical blood.18

In the present study, we addressed the value of ACE in tracing the earliest, pre-AGM stages of human intraembryonic angio-hematopoiesis. We found ACE to be expressed in all blood-forming tissues—the YS, Sp, aorta, fetal liver, and BM—and this expression was tightly correlated with the maintenance of hematopoiesis in these organs. Furthermore, our results indicate that at the earliest stages of human development, hematopoietic potential in the Sp is restricted to emerging CD34−ACE+ precursors. These results suggest the existence of an ACE+CD34−CD45− mesodermal precursor migrating from the Sp toward the ventral aorta to give rise to CD34+ intraaortic hematopoietic clusters.

Methods

Human tissues

Human embryos and fetal tissues were obtained from voluntary or therapeutic abortions performed according to the guidelines and with the approval of the French National Ethics Committee (Table 1). Written consent to the use of the tissues in research was obtained from patients in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Embryos were staged using anatomic criteria and the Carnegie classification as described previously.19 Fetal stages were estimated from menstrual history and confirmed by anatomic criteria.

Number of human embryonic and fetal tissues used in this study and respective type of analysis effectuated

| Age . | . | . | . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Embryo, Carnegie stage | Days | IHC analysis | In vitro analysis |

| 8-9 | 19-21 | 2 | ND |

| 10 | 22-23 | 7 | 3 |

| 11 | 24-25 | 5 | 3 |

| 12 | 26-27 | 9 | 4 |

| 13 | 28-30 | 2 | ND |

| 14 | 31-32 | 2 | ND |

| 15 | 33-36 | 4 | ND |

| 16 | 37-40 | 2 | ND |

| 17 | 41-43 | 1 | ND |

| Liver, wk | IHC analysis | In vitro analysis | In vivo analysis |

| 4-6 | 15 | ND | ND |

| 7-11 | 8 | 7 | ND |

| 14-20 | 3 | 5 | 7 |

| 21-27 | 3 | 2 | ND |

| BM, wk | FACS analysis | In vitro analysis | In vivo analysis |

| 7-11 | 2 | ND | ND |

| 14-20 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| 21-22 | ND | 2 | 1 |

| Age . | . | . | . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Embryo, Carnegie stage | Days | IHC analysis | In vitro analysis |

| 8-9 | 19-21 | 2 | ND |

| 10 | 22-23 | 7 | 3 |

| 11 | 24-25 | 5 | 3 |

| 12 | 26-27 | 9 | 4 |

| 13 | 28-30 | 2 | ND |

| 14 | 31-32 | 2 | ND |

| 15 | 33-36 | 4 | ND |

| 16 | 37-40 | 2 | ND |

| 17 | 41-43 | 1 | ND |

| Liver, wk | IHC analysis | In vitro analysis | In vivo analysis |

| 4-6 | 15 | ND | ND |

| 7-11 | 8 | 7 | ND |

| 14-20 | 3 | 5 | 7 |

| 21-27 | 3 | 2 | ND |

| BM, wk | FACS analysis | In vitro analysis | In vivo analysis |

| 7-11 | 2 | ND | ND |

| 14-20 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| 21-22 | ND | 2 | 1 |

IHC indicates immunohistochemistry; and ND, not done.

Cell preparation

Liver cells (6-27 weeks of development) were dissociated mechanically and passaged through a cell strainer (70 μm; BD Biosciences). Ribs, femurs, tibias, fibulas, humeri, radii, and ulnas harvested at 14-23 weeks were cut into small fragments, then incubated in RPMI 1640 medium containing 0.1% collagenase type I, II, and IV and hyaluronidase type VIII (Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 minutes at 37°C. Cells recovered by flushing bones in PBS containing 5% FCS (HyClone Laboratories) were washed and filtered through the cell strainer. In all cases, mononuclear cells were separated by centrifugation over a Ficoll-Hypaque gradient (Pharmacia Biotech) for 30 minutes at room temperature (RT).

Immunolabeling and sorting of ACE/BB9+ cells

Cells were first labeled with the mAb BB9 (BD Pharmingen), followed by goat anti–mouse IgG1-PE (Southern Biotechnology). For the isolation of the CD34+, CD34+CD45+, or CD34+CD38− subsets, cells were incubated with BB9, followed by anti–mouse IgG1-PE, after which nonbinding mouse IgG1 isotype control (Southern Biotech) was added to block excess sites on the anti–mouse IgG1 PE-conjugated Ab.17 Cells were then labeled with anti-CD34–FITC (581) or a combination of anti-CD34–APC (581) and anti-CD45–FITC (J33) or anti-CD38–FITC (T16; Immunotech-Beckman Coulter). Cells were washed and populations sorted on a Vantage FACS sorter (BD Biosciences); all sorted cells were then re-analyzed. Appropriately conjugated isotype-matched Ab controls from Immunotech were used.

Simultaneous B cell, natural killer cell, and granulomonocytic differentiation in vitro

Cells were cocultured on MS-5 stroma and analyzed by flow cytometry as described previously.10 Briefly, sorted cells were seeded at 1, 10, 100, and 500 cells/well on a 96-well plate over a MS-5 stromal cell layer and cultivated in 10% heat-inactivated human serum (StemCell Technologies), 5% FCS (StemCell Technologies), and the following recombinant human cytokines: 50 ng/mL of SCF, 50 ng/mL of Flt3-ligand, 50 ng/mL of thrombopoietin, 5 ng/mL of IL-2, 10 ng/mL of IL-3, 20 ng/mL of IL-7, and 10 ng/mL of IL-15 (PromoCell). Plates were scored by microscopy over 12 weeks and wells with significant cell proliferation were selected. Cells were collected by pipetting and labeled with CD15-FITC, CD19-PE, CD34-FITC, and CD56-PE–Cy5 mouse Abs (Immunotech) for FACS analysis. A portion of the harvested cells was seeded back over a fresh MS-5 layer. The frequency of long-term culture initiating cells was established by limiting dilution using Poisson distribution (Table 2).

Number of ACE+ and ACE− cells sorted from the human P-Sp ranging from 23-26 days of development, and respective number of colonies grown in methylcellulose after 12 days of culture

| Embryo age . | ACE+ . | ACE− . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carnegie stage . | Days . | Sorted cells . | Colonies . | Sorted cells . | Colonies . |

| 10 | 23 | 148 | 3 | 2143 | 3 |

| 11 | 24.5 | 556 | 4 | 7247 | 2 |

| 12 | 26 | 434 | 16 | 17 675 | 2 |

| 12 | 26 | 45 | 1 | 1174 | 0 |

| Embryo age . | ACE+ . | ACE− . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carnegie stage . | Days . | Sorted cells . | Colonies . | Sorted cells . | Colonies . |

| 10 | 23 | 148 | 3 | 2143 | 3 |

| 11 | 24.5 | 556 | 4 | 7247 | 2 |

| 12 | 26 | 434 | 16 | 17 675 | 2 |

| 12 | 26 | 45 | 1 | 1174 | 0 |

T-cell differentiation in vitro

T-cell differentiation was carried out on a confluent stroma of OP-9 cells (kindly provided by Dr I. André-Schmutz, Inserm Unit 768), which were transduced with the human ligand of Notch Delta-1.20 Culture medium was α medium with GlutaMAX I (Invitrogen) supplemented with 1% antibiotics, 20% defined FCS, and human recombinant SCF (10 ng/mL), Flt3-ligand (5 ng/mL), and IL-7 (2 ng/mL) proteins (PromoCell).

CFC assays

FACS-sorted ACE+ or ACE− cells were plated in 1.1 mL of methylcellulose-based medium (MethoCult H4230; StemCell Technologies) supplemented with 10 ng/mL of IL-3, 10 ng/mL of IL-6, 10 ng/mL of basic FGF, 15 ng/mL of VEGF, 20 ng/mL of thrombopoietin, 50 ng/mL of BMP4, 10 ng/mL of IGF-I, 50 ng/mL of SCF, 50 ng/mL of Flt3-ligand, 3 U/mL of erythropoietin, 20 ng/mL of G-CSF, and 10 ng/mL of GM-CSF (PromoCell) on mitomycin-treated OP-9 stroma. Cultures were incubated at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere, and colonies were counted after 12 days. High proliferative potential colony-forming cell (HPP-CFC)–derived colonies were picked individually from methylcellulose cultures, washed in PBS 2% FCS, and labeled with mouse anti–human CD45-FITC Ab (Immunotech) for FACS analysis, or morphologically analyzed after cytospin centrifugation and May-Grünwald-Giemsa staining.

NOD/SCID mouse repopulation

Sorted CD34+ACE+ or CD34+ACE− cells were transplanted intravenously into 6- to 10-week-old sublethally irradiated (3.2 Gy) female NOD/SCID mice. Human cell engraftment was assessed by FACS analysis of blood cells 8 and 16 weeks later. Mice were killed 24 weeks after transplantation and the BM, spleens, and blood were analyzed. Anti–mouse CD45-PE (30-F11; BD Biosciences), and anti–human HLA-ABC–FITC (B9.12.1), anti–human CD45-FITC (J33) anti–human CD19-PE (J4.119), anti–human CD33-PE (D3HL60), anti–human CD15-FITC (8DH5), and anti–human CD34-PE (581; Immunotech) were used for characterizing host and donor cells. BM cells were re-injected into secondary irradiated NOD/SCID mice and 12 weeks later BM was assessed for engraftment.

Immunohistochemistry

Tissues were fixed in PBS 4% para-formaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich), embedded, and stored at −80°C, as described previously.19 Sections (5 μm) were incubated with uncoupled primary Abs overnight at 4°C, then 1 hour at RT with biotinylated secondary Abs, and finally with fluorochrome or peroxidase-labeled streptavidin (Immunotech). Peroxidase activity was revealed with 0.025% 3,3-diaminobenzidine (Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS containing 0.03% hydrogen peroxide. Tyramide signal amplification (TSA) biotin or TSA plus fluorescence amplification systems were used to detect low amounts of Ags (NEN-Perkin Elmer). For double staining, sections were first stained using the TSA amplification system, then incubated in PBS plus 0.6% hydrogen peroxide for 10 minutes. After 3 washings in PBS, slides were treated with an avidin-biotin blocking kit (Vector), followed by incubation with specific Ab for 1 hour at RT. Fluorescence-labeled secondary Abs were then used. Slides revealed with 3,3-diaminobenzidine were counterstained with Gill's hematoxylin (Sigma-Aldrich), mounted in XAM neutral medium (BDH Laboratory Supplies), and examined and imaged using an Optiphot 2 microscope (Nikon). Stained sections were mounted in Mowiol containing 4′,6-diamino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride. An isotype-matched negative control was performed for each immunostaining. Immunofluorescent staining was observed on a DMR/HCS fluorescence microscope (Leica DMS) and images were acquired using Metavue software (Molecular Devices). Anti–human primary Abs used were: unlabeled CD34 (Qbend-10; Serotec), CD45 (HLe-1; BD Biosciences), SSEA-1 (clone MC-480; Chemicon), Oct-4A (C-10; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), CD41 (kindly provided by Dr E. Rubinstein, Inserm Unit 1004), KDR (KDR-1; Sigma-Aldrich), CXCR4 (12G5; BD Biosciences), and SDF-1 (kindly provided by Dr F. Arenzana, Pasteur Institute, Paris, France). Secondary goat anti–mouse IgG Ab was biotinylated (Immunotech) or coupled to Alexa Fluor 488 (Molecular Probes). Biotinylated secondary goat anti–rabbit IgG Ab (Vector Laboratories) and biotinylated secondary anti–mouse IgM (Southern Biotech) were used.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the Student t test. P < .05 was considered significant.

Results

Previously, we analyzed in detail the incipient human hematopoietic system2,21 and identified a novel site of hematopoietic cell generation, the intraembryonic splanchnopleura, as the origin of definitive hematopoiesis in humans.4,8,10 In the present study, we further document the embryonic emergence of human blood cells using BB9, an mAb that typifies the most primitive HSCs at adult stages17 and human embryonic stem cell (hESC)–derived hemangioblasts,22 and recognizes ACE, a key component of the renin-angiotensin system (RAS).18 This analysis embraces all hemogenic sites that appear sequentially during development: the YS, para-aortic splanchnopleura (P-Sp), aorta, liver, and BM.

ACE/BB9 is expressed in all hematopoietic tissues during human development

YS and embryo.

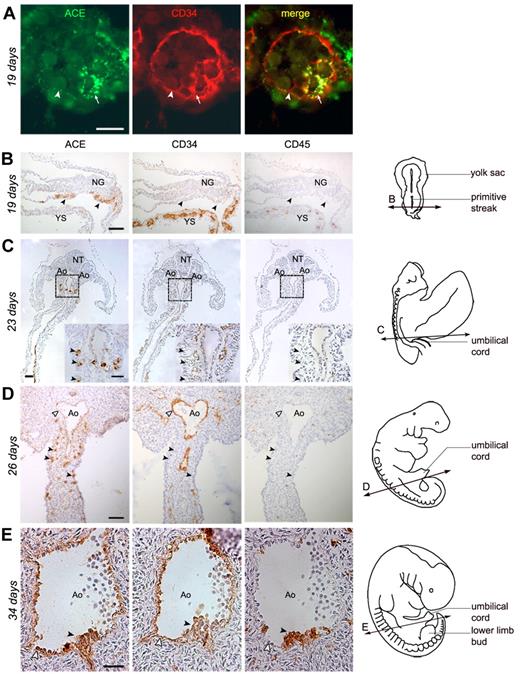

The earliest tissue analyzed was a 19-day pre-somitic embryo (stage 8), in the YS of which ACE/BB9 marks the endoderm and endothelial cells bordering the newly formed blood vessels (Figure 1A). ACE also identifies rare solid blood islands still present in the mesoderm, which express CD34 and are closely associated with the emerging endothelium (Figure 1A). Differentiated erythroid cells present in YS blood vessels were ACE negative (not shown). With ongoing development, the expression of ACE in the YS remained restricted to the endoderm and, to some extent, to the surface of some endothelial cells (not shown). At 19 days of development, the aortae were not yet developed inside of the embryo, as shown by the complete absence of CD34+ endothelial cells (Figure 1B), suggesting that the blood flow between YS and embryo had not yet been established.4 This is also supported by the absence, inside the embryo, of hematopoietic cells expressing the pan-leukocyte Ag CD45 (Figure 1B) and the erythroid cell Ag glycophorin A (not shown). At this same stage of ongoing gastrulation, ACE was also detected at the surface of rare cells concentrated in the caudal portion of the splanchnopleura in contact with the YS. These cells expressed neither CD34 nor CD45 (Figure 1B). From this stage on, ACE was expressed by splanchnopleural cells caudal to the YS localized in the presumptive hindgut. At 23 days of development (11 somite pairs), cells expressing ACE were concentrated in the dorsal mesenteric mesoderm, which surrounds the dorsal aortae, and were always localized in the caudal portion of the embryo (Figure 1C and supplemental Figure 1). ACE+CD34−CD45− cells increased in number with development (Figure 1D 26 days) and, starting from the 27th day, when hematopoiesis occurs inside the embryo, ACE was detected on CD34+CD45+ hematopoietic progenitors emerging on the ventral side of the dorsal aorta, as well as on adjacent endothelial cells (Figure 1E). Endothelial cells of other vessels, such as cardinal veins, never expressed ACE, which remained restricted to the endothelial cells bordering the dorsal aorta (supplemental Figure 2).

Expression of ACE in the human embryo. (A-B) Transverse sections of a 19-day human embryo. (A) In the extraembryonic YS, ACE/BB9 (green) and CD34 (red) are expressed in the hemangioblastic structures, blood islands (arrows), and in some endothelial cells bordering newly formed blood vessels (arrowheads). (B) In the embryo proper, ACE marks rare cells scattered in the caudal portion of the splanchnopleura (arrows). No co-localization of the CD34 or CD45 Ags is observed in these ACE+ cells. (C-D) Cross-sections through 23- and 26-day human embryos. At these stages, ACE expression is limited to some migrating cells concentrated in the mesoderm of the dorsal mesentery, which surrounds the dorsal aorta (Ao), in the caudal portion of the embryo. These ACE+ cells express neither CD34 nor CD45 (arrowheads in the inset on the right, which represents a high magnification of the splanchnopleura dotted in panel C). At 26 days of development, some endothelial CD34+ cells, which border the lumen of the aorta, also express ACE (white arrowheads). (E) Cross-sections through the dorsal aorta in a 34-day embryo. ACE is expressed by hematopoietic CD34+CD45+ cell clusters associated with the endothelium on the ventral side of the aorta (arrowheads), as well as by surrounding endothelial CD34+ cells (white arrowheads). The diagrams on the right in panels B through E indicate the position of the respective sections. Scale bar in panel A represents 20 μm; and panels B through E, 50 μm. NG indicates neural groove; NT, neural tube.

Expression of ACE in the human embryo. (A-B) Transverse sections of a 19-day human embryo. (A) In the extraembryonic YS, ACE/BB9 (green) and CD34 (red) are expressed in the hemangioblastic structures, blood islands (arrows), and in some endothelial cells bordering newly formed blood vessels (arrowheads). (B) In the embryo proper, ACE marks rare cells scattered in the caudal portion of the splanchnopleura (arrows). No co-localization of the CD34 or CD45 Ags is observed in these ACE+ cells. (C-D) Cross-sections through 23- and 26-day human embryos. At these stages, ACE expression is limited to some migrating cells concentrated in the mesoderm of the dorsal mesentery, which surrounds the dorsal aorta (Ao), in the caudal portion of the embryo. These ACE+ cells express neither CD34 nor CD45 (arrowheads in the inset on the right, which represents a high magnification of the splanchnopleura dotted in panel C). At 26 days of development, some endothelial CD34+ cells, which border the lumen of the aorta, also express ACE (white arrowheads). (E) Cross-sections through the dorsal aorta in a 34-day embryo. ACE is expressed by hematopoietic CD34+CD45+ cell clusters associated with the endothelium on the ventral side of the aorta (arrowheads), as well as by surrounding endothelial CD34+ cells (white arrowheads). The diagrams on the right in panels B through E indicate the position of the respective sections. Scale bar in panel A represents 20 μm; and panels B through E, 50 μm. NG indicates neural groove; NT, neural tube.

The liver.

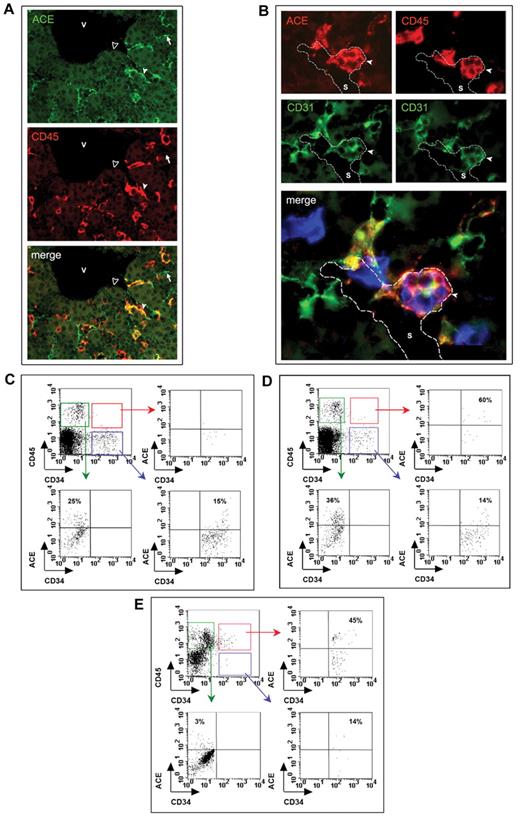

In the hepatic rudiment, ACE was first detected at 30 days in some endothelial cells (supplemental Figure 3). At this stage, the first definitive hematopoietic cells are also found in the liver, as assessed by double expression of CD34 and CD454 (supplemental Figure 3). Starting from 7 weeks, ACE marks hepatic endothelial cells but also rare hematopoietic progenitor cells co-expressing CD34 and CD45 (not shown). Intriguingly, some flattened ACE+ cells bordering the lumen of hepatic sinusoids also express CD45, suggesting their commitment to hematopoiesis (Figure 2A). At this stage, the liver represents the major blood-forming tissue within the embryo and supports the proliferation of hematopoietic progenitors, before the colonization of BM cavities.4 Interestingly, CD34+CD45+ hematopoietic progenitors also expressing ACE develop from 8.5 weeks as cell aggregates adhering to sinusoid endothelial cells (Figure 2B). The number of these structures increases until at least week 11, the earliest fetal liver we analyzed (Table 1), to become more rare from week 15, when numerous CD34+CD45+ hematopoietic progenitors were distributed in the hepatic parenchyma (not shown). At later stages, ACE expression in the liver was limited to endothelial cells bordering the sinusoids and some rare CD34+CD45+ hematopoietic progenitors. No reactivity with the BB9 Ab was detected in endothelial cells bordering larger veins in the portal venous system at any stage (not shown).

Expression of ACE in the human fetal liver and BM. (A) Transverse section through a 7.5-week liver stained by anti-CD45 (red) and ACE (green) Abs. ACE marks numerous endothelial cells of the sinusoidal capillaries (arrows), some of which are also CD45+ (white arrowheads). No expression of ACE is observed in the endothelial cells bordering the larger hepatic veins (black arrowheads). (B) Adjacent sections through an 11-week liver stained for ACE (red) and CD31 (green), and for CD45 (red) and CD31 (green), respectively. Overlap of adjacent sections: ACE in red, CD45 in blue and CD31 in green. Hematopoietic CD45+CD31+ progenitors, also expressing ACE, develop as cell aggregates adhering to sinusoid endothelial cells (arrows). Scale bar in panel A represents 50 μm; and B, 100 μm. V indicates vein; S, sinusoidal capillary. (C-E) FACS analysis of ACE expression during BM development. At 8.5 weeks of development (C), ACE is only expressed by endothelial and hematopoietic CD45+CD34− cells in the BM, as shown by the absence of cells expressing ACE in the CD34+CD45+-gated population. Starting from 9.6 weeks of gestation, when blood cell colonization has taken place in the BM, some CD34+CD45+ progenitors expressing ACE are detected in the medullar cavity (D). This population is also detected at later stages when hematopoiesis is already active inside the BM (E; 14 weeks).

Expression of ACE in the human fetal liver and BM. (A) Transverse section through a 7.5-week liver stained by anti-CD45 (red) and ACE (green) Abs. ACE marks numerous endothelial cells of the sinusoidal capillaries (arrows), some of which are also CD45+ (white arrowheads). No expression of ACE is observed in the endothelial cells bordering the larger hepatic veins (black arrowheads). (B) Adjacent sections through an 11-week liver stained for ACE (red) and CD31 (green), and for CD45 (red) and CD31 (green), respectively. Overlap of adjacent sections: ACE in red, CD45 in blue and CD31 in green. Hematopoietic CD45+CD31+ progenitors, also expressing ACE, develop as cell aggregates adhering to sinusoid endothelial cells (arrows). Scale bar in panel A represents 50 μm; and B, 100 μm. V indicates vein; S, sinusoidal capillary. (C-E) FACS analysis of ACE expression during BM development. At 8.5 weeks of development (C), ACE is only expressed by endothelial and hematopoietic CD45+CD34− cells in the BM, as shown by the absence of cells expressing ACE in the CD34+CD45+-gated population. Starting from 9.6 weeks of gestation, when blood cell colonization has taken place in the BM, some CD34+CD45+ progenitors expressing ACE are detected in the medullar cavity (D). This population is also detected at later stages when hematopoiesis is already active inside the BM (E; 14 weeks).

The BM.

Because of incompatibility between decalcification treatments and immunoreactivity, ACE expression in the BM was studied by flow cytometry. We examined long bones from 5 human embryos and fetuses whose developmental ages ranged from 8.5-15 weeks. At early stages of long-bone endochondral development (8.5 weeks), when chondrolysis has already taken place in cartilaginous rudiments,21 ACE is expressed at the surface of CD34+CD45− cells and of some CD34−CD45+ cells. These cells likely represent the first endothelial and hematopoietic (probably monocyte-macrophage) cells, respectively (Figure 2C), which we have previously shown to invade the forming BM cavity.21 At 9.6 weeks, rare CD34+CD45+ hematopoietic progenitors were detected in BM-cell suspensions, confirming that BM colonization is occurring at this stage.21 Interestingly, the majority of these scattered hematopoietic cells were ACE+ (Figure 2D). At later stages (14 weeks or more), when hematopoiesis is already active inside the medullary cavity, ACE marks CD34+CD45− endothelial cells but also CD45+CD34+ hematopoietic cells (Figure 2E). At these stages, some ACE+ cells express neither CD34 nor CD45 (not shown) and likely represent mesenchymal cells in the microenvironment.18

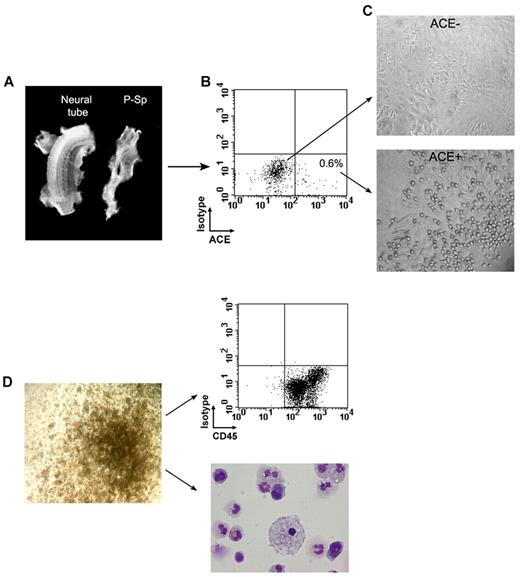

ACE marks CD34−CD45− early hematopoietic precursor cells

To determine whether ACE+ cells present in the early embryo possess hematopoietic potential, we performed coculture experiments in vitro. The P-Sp was microdissected from embryos ranging in age from 23-26 days and dissociated either mechanically or by collagenase digestion and further processed for flow cytometric analysis and sorting (Figure 3A-B). As shown by immunohistochemical staining (Figure 1C-D and supplemental Figure 1), ACE marks CD34−CD45− cells scattered in the caudal splanchnopleura. Although ACE+ cells were identifiable by flow cytometry at these stages, their percentage was very modest, representing less than 1% of all cells in suspension (Figure 3B). ACE+ sorted cells ranged from 30-300 for each P-Sp analyzed. Sorted ACE+ and ACE− cells were seeded at densities of 30-150 cells and 700-3600 cells per well, respectively, over layers of MS-5 stromal cells. Hematopoietic activity was detected in the wells containing ACE+ cells, as indicated by the development of colonies of rounded cells adhering to the stromal cell layer beginning after 3-4 days of culture (Figure 3C). Although these colonies grew rapidly to reach several hundreds of cells at 15 days of culture (not shown), these culture conditions did not allow for their phenotypic characterization by FACS, because they stopped proliferating and differentiated thereafter. To permit a more efficient expansion of ACE+ and ACE− sorted cells, these very primitive precursors issued from early human splanchnopleura were directly plated under conditions that support the development of blast-CFCs derived from mouse embryoid bodies, and also allow for the expansion of HPP-CFCs from the mouse AGM region.23,24 Table 2 shows the numbers of ACE+ and ACE− cells sorted from 4 human P-Sp specimens ranging from 23-26 days of development, and the respective numbers of colonies grown in methylcellulose after 12 days of culture. Several colonies derived from CFU-GM, or even larger colonies of less mature cells derived from HPP-CFCs, developed in the plates seeded with ACE+ cells (Figure 3D). In each experiment, a few colonies were also observed in dishes containing the ACE− cell population (Table 2). However, these colonies were frequently hemoglobinated and therefore were identified as erythroid, indicating that they derived from already committed CFU-E progenitors (not shown). In all experiments, the frequency of colonies stemming from ACE+ progenitors (Table 2) was significantly higher than that obtained with ACE− cells (2.2% ± 1.2% and 0.04% ± 0.06%, respectively, P < .02), making the possibility of a contamination highly unlikely.

Generation in culture of hematopoietic cells from human embryonic splanchnopleura–derived ACE+ and ACE− cells. (A) The P-Sp and the rest of the embryo are shown during dissection of a 24-day human embryo. (B) Sorting of ACE+ and ACE− cells after dissection of a 26-day human splanchnopleura showed that ACE+ cells represent less than 1% of the total population. (C) After 3-4 days of culture, only ACE+ cells gave rise to rounded cells, presumably hematopoietic colonies, adhering to the stromal cell layer. (D) Sorted ACE+ cells contain GM-CFU and more primitive HPP-CFU clonogenic progenitors (left). Fifteen-day colonies contain hematopoietic cells as confirmed by flow cytometric analysis after CD45 staining and by May-Grünwald-Giemsa coloration (right).

Generation in culture of hematopoietic cells from human embryonic splanchnopleura–derived ACE+ and ACE− cells. (A) The P-Sp and the rest of the embryo are shown during dissection of a 24-day human embryo. (B) Sorting of ACE+ and ACE− cells after dissection of a 26-day human splanchnopleura showed that ACE+ cells represent less than 1% of the total population. (C) After 3-4 days of culture, only ACE+ cells gave rise to rounded cells, presumably hematopoietic colonies, adhering to the stromal cell layer. (D) Sorted ACE+ cells contain GM-CFU and more primitive HPP-CFU clonogenic progenitors (left). Fifteen-day colonies contain hematopoietic cells as confirmed by flow cytometric analysis after CD45 staining and by May-Grünwald-Giemsa coloration (right).

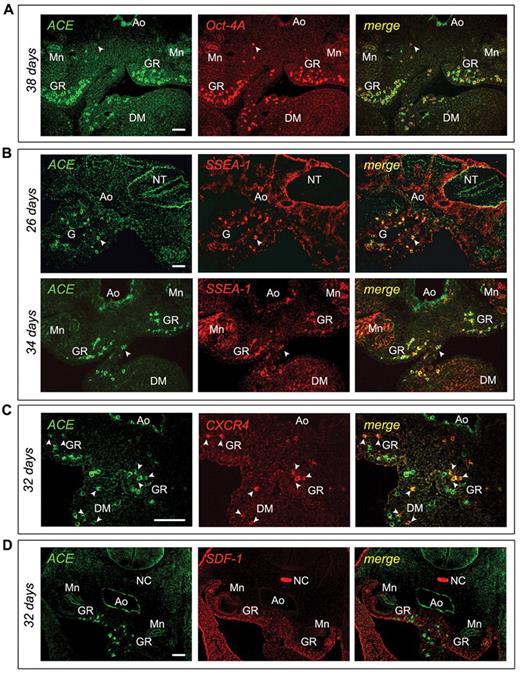

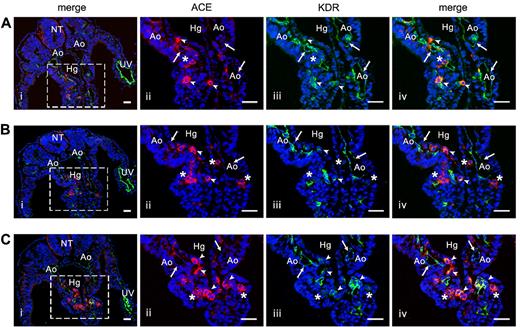

As expected, FACS analysis of dissociated 15-day colonies showed the presence of CD45+ cells that were confirmed to be hematopoietic cells by morphological analysis after May-Grünwald-Giemsa staining (Figure 3D). These results suggested the existence of a hematopoietic splanchnopleural ACE/BB9+ cell subset. We next evaluated the Ag-expression profile of this population by immunohistochemistry. Embryonic ACE+ cells did not express endothelium-specific markers such as CD31 or VE-cadherin,25,26 (Table 3) or CD93, the human equivalent of AA4.1 that characterizes HSCs in the murine subaortic patches.7 In contrast, ACE+ cells in the embryo strongly express the nuclear transcription factor Oct-4A and the surface embryonic Ag SSEA-1 (Figure 4A-B). Some of the ACE+ cells scattered in the mesoderm underneath the dorsal aorta also express the CXCR4 receptor (Figure 4C), which is known to link the SDF-1 chemokine, and in response to stimulate cell migration.27 We indeed found that SDF-1 is expressed abundantly, and with striking polarity, in the human AGM in a region underlying the hemogenic aorta, precisely at the stages when hematopoietic cell clusters emerge (Figure 4D). Interestingly, SDF-1 expression disappears after day 40, when hematopoietic cells are no longer produced in the aorta4 (data not shown). Intriguingly, as shown in Figure 5, some of these ACE+ cells within the splanchnopleura of the early embryo also express the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (KDR), already identified as a marker of hemangioblast-like cells.28

Expression profile of ACE/BB9+ cells inside the human embryo

| Marker . | Splanchnopleural ACE/BB9+ cells . | Aortic hematopoietic cell clusters . | Endothelial cells . |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACE/BB9 | + | + | + |

| SSEA1 | + | +/− | − |

| Oct-4A | + | − | − |

| CXCR4 | +/− | − | − |

| KDR | +/− | + | + |

| CD31 | − | + | + |

| CD34 | − | + | + |

| CD41 | − | − | − |

| CD43 | − | + | − |

| CD45 | − | + | − |

| CD93 | − | + | + |

| VE-Cad | − | + | + |

| Marker . | Splanchnopleural ACE/BB9+ cells . | Aortic hematopoietic cell clusters . | Endothelial cells . |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACE/BB9 | + | + | + |

| SSEA1 | + | +/− | − |

| Oct-4A | + | − | − |

| CXCR4 | +/− | − | − |

| KDR | +/− | + | + |

| CD31 | − | + | + |

| CD34 | − | + | + |

| CD41 | − | − | − |

| CD43 | − | + | − |

| CD45 | − | + | − |

| CD93 | − | + | + |

| VE-Cad | − | + | + |

Phenotype of the ACE+ cells in the P-Sp/AGM of the early human embryo. (A) Cross-sections of a 38-day human embryo immunostained with ACE/BB9 (green) and anti–Oct-4A (red) Abs. The majority of the mesodermal ACE+ cells express the transcription factor Oct-4A, which is also expressed by other ACE− cells dispersed in the AGM region and localized in the ventral wall of the aorta (arrow). (B) Transversal sections of a 26- and a 34-day human embryo were co-stained with ACE/BB9 (green) and anti–SSEA-1 (red) Abs. ACE+ cells dispersed in the paraaortic mesoderm co-express SSEA-1 (arrow). At 34 days, ACE also stained the endothelial cells and the hematopoietic cell clusters associated with the ventral aortic endothelium. Some of these hematopoietic progenitors also express SSEA-1. (C-D) Cross-sections of a 32-day embryo were stained with ACE and CXCR4 Abs (C), and ACE and SDF-1 Abs (D), respectively. Some ACE+ cells dispersed in the paraaortic mesoderm co-express the receptor CXCR4 (arrow, C). At these stages, this region presents a polarized expression of the SDF-1 chemokine (D). Scale bar indicates 50 μm. Ao indicates aorta; G, gut; DM, dorsal mesentery; GR, genital ridges; Mn, mesonephros; NC, notochord; and NT, neural tube.

Phenotype of the ACE+ cells in the P-Sp/AGM of the early human embryo. (A) Cross-sections of a 38-day human embryo immunostained with ACE/BB9 (green) and anti–Oct-4A (red) Abs. The majority of the mesodermal ACE+ cells express the transcription factor Oct-4A, which is also expressed by other ACE− cells dispersed in the AGM region and localized in the ventral wall of the aorta (arrow). (B) Transversal sections of a 26- and a 34-day human embryo were co-stained with ACE/BB9 (green) and anti–SSEA-1 (red) Abs. ACE+ cells dispersed in the paraaortic mesoderm co-express SSEA-1 (arrow). At 34 days, ACE also stained the endothelial cells and the hematopoietic cell clusters associated with the ventral aortic endothelium. Some of these hematopoietic progenitors also express SSEA-1. (C-D) Cross-sections of a 32-day embryo were stained with ACE and CXCR4 Abs (C), and ACE and SDF-1 Abs (D), respectively. Some ACE+ cells dispersed in the paraaortic mesoderm co-express the receptor CXCR4 (arrow, C). At these stages, this region presents a polarized expression of the SDF-1 chemokine (D). Scale bar indicates 50 μm. Ao indicates aorta; G, gut; DM, dorsal mesentery; GR, genital ridges; Mn, mesonephros; NC, notochord; and NT, neural tube.

Colocalization of ACE and KDR in the human embryo. (A-C) Three successive transverse sections in the caudal portion of a 23-day human embryo stained by anti-KDR (green) and ACE/BB9 (red) Abs. Subpanels ii through iv show a higher magnification of the boxed area in subpanel i. All of the endothelial cells in the aorta and umbilical vein are stained by KDR (i,iii; arrows). No colocalization of ACE is observed in these KDR+ endothelial cells (ii-iv). At this stage, ACE (ii) stains some cells scattered in the splanchnopleura (head arrows and asterisks). Only some of these ACE+ cells also express KDR (iii-iv, head arrows). Nuclei were visualized by 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole staining (blue). Scale bar indicates 20 μm in subpanel i and 40 μm in subpanels ii through iv. Ao indicates aorta; UV, umbilical vein; NT, neural tube; Hg, hindgut.

Colocalization of ACE and KDR in the human embryo. (A-C) Three successive transverse sections in the caudal portion of a 23-day human embryo stained by anti-KDR (green) and ACE/BB9 (red) Abs. Subpanels ii through iv show a higher magnification of the boxed area in subpanel i. All of the endothelial cells in the aorta and umbilical vein are stained by KDR (i,iii; arrows). No colocalization of ACE is observed in these KDR+ endothelial cells (ii-iv). At this stage, ACE (ii) stains some cells scattered in the splanchnopleura (head arrows and asterisks). Only some of these ACE+ cells also express KDR (iii-iv, head arrows). Nuclei were visualized by 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole staining (blue). Scale bar indicates 20 μm in subpanel i and 40 μm in subpanels ii through iv. Ao indicates aorta; UV, umbilical vein; NT, neural tube; Hg, hindgut.

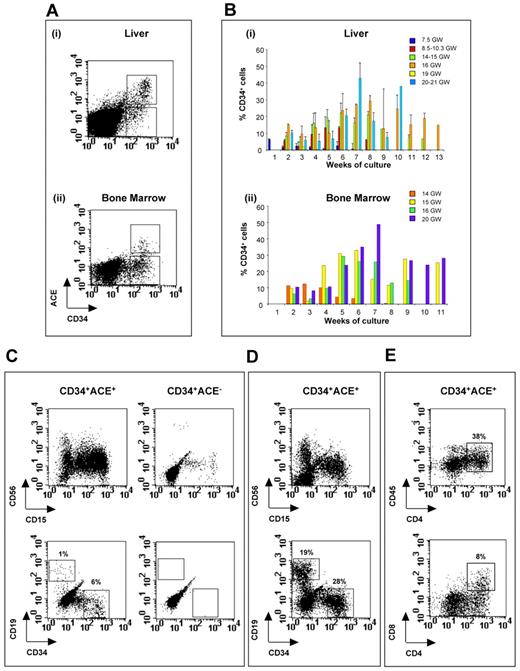

Fetal liver and BM long-term blood-forming cells in culture and in vivo are exclusively CD34+ACE+

CD34+ACE− or CD34+ACE+ cells sorted from liver and BM ranging from 7.5-22 weeks of development were seeded over MS-5 stromal cells at densities of 1, 10, 100, and 500 cells/well in 96-well plates. Wells containing blood cell colonies were counted at the 35th day of culture. Only wells containing subconfluent hematopoietic cells were further processed. Long-term hematopoiesis (more than 35 days) only occurred in wells seeded with ACE+ progenitors, indicating that the ACE/BB9 Ab selects primitive hematopoietic precursor cells (Table 4). In contrast, despite the 10- to 20-fold higher densities of cells seeded (500, 1000, and 2000 cells/well), cultures initiated with ACE− cells showed a rapid exhaustion after 2 weeks of initial growth, and hematopoietic cells had disappeared after a maximum of 20-25 days of culture. Among ACE+ cells the frequency of progenitors initiating long-term hematopoiesis varies in the liver with development, with a peak (1 of 30) at 16 weeks of gestation, when the liver represents the principal hematopoietic organ in the fetus. This frequency decreases at later stages, and is correlated with the decline of hematopoietic competence in the hepatic organs (Figure 6B and Table 4). In contrast, the frequency of long-term hematopoiesis-initiating cells in BM-derived CD34+ACE+ cells remained almost constant in the BM during development (average, 1 of 163), indicating the maintenance of blood-forming competences in this organ throughout human ontogenesis (Figure 6B and Table 4). The average percentage of endothelial cells in the sorted CD34+ACE+ cell population amounted to 6% and 28%, respectively, in the liver and BM. However, hematopoietic CD34+ACE+CD45+ cells, but not endothelial CD34+ACE+CD45− cells, cultured separately exhibited long-term culture-initiating cell potential (not shown).

| Age, wk . | Fetal liver . | BM . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD34+ACE+ . | CD34+ACE− . | CD34+ACE+ . | CD34+ACE− . | |||

| Hematopoiesis* . | Frequency† . | Hematopoiesis* . | Hematopoiesis* . | Frequency† . | Hematopoiesis* . | |

| 7.5 | 2/3 | 1/614 | 0/3 | ND | ND | ND |

| 8.5-9.5 | 3/3 | 1/394 | 0/3 | ND | ND | ND |

| 10.3 | 1/1 | 1/149 | 0/1 | ND | ND | ND |

| 14-15 | 1/1 | 1/18 | 0/1 | 2/2 | 1/131 | 0/2 |

| 16 | 3/3 | 1/37 | 0/3 | 1/1 | 1/226 | 0/1 |

| 18-19 | 1/1 | 1/100 | 0/1 | ND | ND | ND |

| 20-22 | 2/2 | 1/130 | 0/2 | 2/2 | 1/184 | 2/2 |

| Age, wk . | Fetal liver . | BM . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD34+ACE+ . | CD34+ACE− . | CD34+ACE+ . | CD34+ACE− . | |||

| Hematopoiesis* . | Frequency† . | Hematopoiesis* . | Hematopoiesis* . | Frequency† . | Hematopoiesis* . | |

| 7.5 | 2/3 | 1/614 | 0/3 | ND | ND | ND |

| 8.5-9.5 | 3/3 | 1/394 | 0/3 | ND | ND | ND |

| 10.3 | 1/1 | 1/149 | 0/1 | ND | ND | ND |

| 14-15 | 1/1 | 1/18 | 0/1 | 2/2 | 1/131 | 0/2 |

| 16 | 3/3 | 1/37 | 0/3 | 1/1 | 1/226 | 0/1 |

| 18-19 | 1/1 | 1/100 | 0/1 | ND | ND | ND |

| 20-22 | 2/2 | 1/130 | 0/2 | 2/2 | 1/184 | 2/2 |

ND indicates not done.

Ability to give rise to hematopoiesis in culture for at least 35 days.

Frequency of progenitors present in sorted populations able to establish long-term hematopoiesis as estimated by limiting-dilution analysis.

Long-term hematopoietic potential in culture of CD34+ACE+ and CD34+ACE− fetal liver- and BM-derived precursors. Sorted CD34+ACE+ and CD34+ACE− cells were cultivated on MS-5 stromal cells. Proliferating hematopoietic cells were harvested from culture wells, stained with anti–CD19-PE, anti–CD15-FITC, anti–CD56-Cy-PE, and anti–CD34-FITC Abs and analyzed by flow cytometry. (A) Sort regions used for isolation of CD34+ACE+ cells in a 14-week liver (i) and BM (ii). (B) Bar plots indicate the percentages of CD34 progenitors harvested each week from the culture of CD34+ACE+ cells sorted from human fetal liver (i) and BM (ii) at different stages of development. Each bar represents the mean of several wells analyzed at the same time of culture. In panel B, the error bar shows the standard error obtained when more than 1 liver sample at the same stage of development was analyzed after the same time in culture. (C) B-lymphoid CD19+ cells and CD34+ progenitors in the culture of CD34+ACE+ and CD34+ACE− cells sorted from a 14-week fetal liver. Analysis was performed at day 19 of culture. (D) Representative example displaying flow cytometric analysis after 83 days in culture of CD34+ACE+ cells sorted from a 14-week fetal liver. CD34+ cells represent 28% and B cells (CD19+) represent 19% of total harvested cells. (E) T-lymphoid CD4+CD8+ cells generated in the culture of CD34+ACE+ cells sorted from a 14-week fetal liver. Analysis was performed at day 14 of culture. GW indicates gestation weeks.

Long-term hematopoietic potential in culture of CD34+ACE+ and CD34+ACE− fetal liver- and BM-derived precursors. Sorted CD34+ACE+ and CD34+ACE− cells were cultivated on MS-5 stromal cells. Proliferating hematopoietic cells were harvested from culture wells, stained with anti–CD19-PE, anti–CD15-FITC, anti–CD56-Cy-PE, and anti–CD34-FITC Abs and analyzed by flow cytometry. (A) Sort regions used for isolation of CD34+ACE+ cells in a 14-week liver (i) and BM (ii). (B) Bar plots indicate the percentages of CD34 progenitors harvested each week from the culture of CD34+ACE+ cells sorted from human fetal liver (i) and BM (ii) at different stages of development. Each bar represents the mean of several wells analyzed at the same time of culture. In panel B, the error bar shows the standard error obtained when more than 1 liver sample at the same stage of development was analyzed after the same time in culture. (C) B-lymphoid CD19+ cells and CD34+ progenitors in the culture of CD34+ACE+ and CD34+ACE− cells sorted from a 14-week fetal liver. Analysis was performed at day 19 of culture. (D) Representative example displaying flow cytometric analysis after 83 days in culture of CD34+ACE+ cells sorted from a 14-week fetal liver. CD34+ cells represent 28% and B cells (CD19+) represent 19% of total harvested cells. (E) T-lymphoid CD4+CD8+ cells generated in the culture of CD34+ACE+ cells sorted from a 14-week fetal liver. Analysis was performed at day 14 of culture. GW indicates gestation weeks.

Cocultures were analyzed by FACS to evaluate the lineage potential of ACE+ and ACE− hematopoietic progenitors. CD34+ACE+ progenitors generated natural killer (CD56+) and granulo-monocytic (CD15+) cells, as well as B lymphocytes (CD19+). In contrast, CD19+ cells were consistently very rare in the CD34+ ACE− cocultures, and are detected only during the first 2 weeks of culture, indicating the presence in the ACE− cell subset of committed pre-B cells rather than primitive hematopoietic progenitors, the lymphoid differentiation of which usually occurs during the third week of coculture (Figure 6C).10 Furthermore, after 2 weeks of coculture, only wells seeded with ACE+ progenitors contained CD34+ cells that could be maintained over the long term. Figure 6D illustrates the presence of up to 28% CD34+ hematopoietic cells after 83 days of coculture of CD34+ACE+ cells. Culture carried out on OP-9 stromal cells, expressing the Notch ligand Delta1, indicated that CD34+ACE+ cells also exhibit T-cell differentiation potential. Figure 6E illustrates the generation of T-cell precursors up to the (CD4+CD8+) double-positive stage obtained from fetal liver sorted CD34+ACE+ cells after 14 days of coculture. These results suggest the very primitive nature of CD34+ACE+ HSCs sorted from the fetal liver and BM. Conversely, the counterpart CD34+ACE− cell population appears to include principally late, lineage-committed blood-cell progenitors.

To determine whether ACE marks cells with engraftment potential, 0.5-40 × 103 CD34+ACE+ cells or 1.5-94 × 103 CD34+ACE− cells sorted from fetal liver and BM were transplanted into irradiated NOD/SCID mice. Engraftment was examined by flow cytometry analysis at 4 and 6 months after transplantation, and was monitored as the presence of at least 1% human CD45+ cells in the BM of recipient mice. As shown in Table 5, mice that received any number of CD34+ACE+ cells exhibited detectable levels of engraftment (Figure 7A and supplemental Table 1). Conversely, no chimerism was observed in recipients of the CD34+ACE− cell population, even when 3 or 4 times more cells were injected (Table 5). Irrespective of the level of engraftment, all mice that received CD34+ACE+ cells demonstrated multilineage reconstitution as assessed with Abs to myeloid (CD33; mean, 13% of hCD45+cells; range, 9%-19%) and B-lymphoid cells (CD19; mean, 58% of hCD45+ cells; range, 46%-80%). Furthermore, BM cells harvested 4 and 6 months after transplantation of CD34+ACE+ cells contained a significant proportion of CD34-expressing cells (mean, 17.2% of hCD45+cells; range, 11%-30%) and sustained secondary engraftment when transplanted in other irradiated NOD/SCID mice (not shown). A representative example of multilineage engraftment is shown in Figure 7.

In vivo reconstitution capacity of CD34+ACE+ and CD34+ACE− sorted cells and transplantation in secondary NOD/SCID recipients

| Age, wk . | No. of specimens . | Fetal liver . | BM . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD34+ACE+ . | CD34+ACE− . | CD34+ACE+ . | CD34+ACE− . | ||||||||

| No. of injected cells . | Engrafted mice* . | Secondary transplantation . | No. of injected cells . | Engrafted mice* . | No. of injected cells . | Engrafted mice* . | Secondary transplantation . | No. of injected cells . | Engrafted mice* . | ||

| 14 | 1 | 1 × 103 | 2/3 | ND | 1.5 × 103 | 0/2 | ND | ||||

| 2 × 103 | 3/3 | ND | ND | ||||||||

| 5 × 103 | 3/3 | 1/2 | ND | ||||||||

| 10 × 103 | 3/3 | 2/2 | ND | ||||||||

| 16 | 1 | 17 × 103 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 42 × 103 | 0/1 | ND | ||||

| 2 | 40 × 103 | 1/1 | ND | 94 × 103 | 0/1 | ND | |||||

| 3 | 9 × 103 | 1/1 | ND | 6 × 103 | 0/1 | ND | |||||

| 18 | 1 | 0.5 × 103 | 1/2 | ND | 5 × 103 | 0/2 | ND | ||||

| 2 × 103 | 1/2 | ND | ND | ||||||||

| 5 × 103 | 1/2 | ND | ND | ||||||||

| 19 | 1 | ND | 1.7 × 103 | 2/2 | ND | 7 × 103 | 0/2 | ||||

| 20 | 1 | ND | 17 × 103 | 1/1 | 0/2 | 35 × 103 | 0/1 | ||||

| 22 | 1 | ND | 1.4 × 103 | 1/1 | ND | 2.5 × 103 | 0/1 | ||||

| Age, wk . | No. of specimens . | Fetal liver . | BM . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD34+ACE+ . | CD34+ACE− . | CD34+ACE+ . | CD34+ACE− . | ||||||||

| No. of injected cells . | Engrafted mice* . | Secondary transplantation . | No. of injected cells . | Engrafted mice* . | No. of injected cells . | Engrafted mice* . | Secondary transplantation . | No. of injected cells . | Engrafted mice* . | ||

| 14 | 1 | 1 × 103 | 2/3 | ND | 1.5 × 103 | 0/2 | ND | ||||

| 2 × 103 | 3/3 | ND | ND | ||||||||

| 5 × 103 | 3/3 | 1/2 | ND | ||||||||

| 10 × 103 | 3/3 | 2/2 | ND | ||||||||

| 16 | 1 | 17 × 103 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 42 × 103 | 0/1 | ND | ||||

| 2 | 40 × 103 | 1/1 | ND | 94 × 103 | 0/1 | ND | |||||

| 3 | 9 × 103 | 1/1 | ND | 6 × 103 | 0/1 | ND | |||||

| 18 | 1 | 0.5 × 103 | 1/2 | ND | 5 × 103 | 0/2 | ND | ||||

| 2 × 103 | 1/2 | ND | ND | ||||||||

| 5 × 103 | 1/2 | ND | ND | ||||||||

| 19 | 1 | ND | 1.7 × 103 | 2/2 | ND | 7 × 103 | 0/2 | ||||

| 20 | 1 | ND | 17 × 103 | 1/1 | 0/2 | 35 × 103 | 0/1 | ||||

| 22 | 1 | ND | 1.4 × 103 | 1/1 | ND | 2.5 × 103 | 0/1 | ||||

ND indicates not done.

Engraftment is based on flow cytometric analysis of BM cells from recipient mice harvested at 4-6 months after transplantation and is defined as at least 1% of human CD45+ cells.

Human hematopoietic engraftment in NOD/SCID mice by CD34+ACE+ fetal liver cells. Representative examples displaying analysis of BM from NOD/SCID recipients of CD34+ACE+ cells sorted from a 14-week human fetal liver. Analyses were performed 4 months after transplantations. (A) Percentage of human CD45+ cells in individual animals that received a transplantation of 1 × 103, 2 × 103, 5 × 103, and 10 × 103 CD34+ACE+ cells. Horizontal lines represent the average percentage of human CD45+ cells in each group. (B) Representative example of multilineage human hematopoietic engraftment in an animal that received a transplantation of 1 × 103 cells. (C) Four mice that received a transplantation of 1 × 103, 2 × 103, 5 × 103, and 10 × 103 CD34+ACE+ cells. The percentages indicate the significant proportion of human CD45+ cells within the BM represented by CD34-expressing cells.

Human hematopoietic engraftment in NOD/SCID mice by CD34+ACE+ fetal liver cells. Representative examples displaying analysis of BM from NOD/SCID recipients of CD34+ACE+ cells sorted from a 14-week human fetal liver. Analyses were performed 4 months after transplantations. (A) Percentage of human CD45+ cells in individual animals that received a transplantation of 1 × 103, 2 × 103, 5 × 103, and 10 × 103 CD34+ACE+ cells. Horizontal lines represent the average percentage of human CD45+ cells in each group. (B) Representative example of multilineage human hematopoietic engraftment in an animal that received a transplantation of 1 × 103 cells. (C) Four mice that received a transplantation of 1 × 103, 2 × 103, 5 × 103, and 10 × 103 CD34+ACE+ cells. The percentages indicate the significant proportion of human CD45+ cells within the BM represented by CD34-expressing cells.

Discussion

ACE, a key regulator of blood pressure, is also a marker of human HSCs.18 We now extend the validity of this marker to trace the very emergence of blood in the human YS, AGM, liver, and BM. Most importantly, ACE is already expressed by a subset of splanchnopleural mesodermal progenitors endowed with blood-forming potential before the appearance of authentic blood cells in the AGM. ACE/BB9 therefore appears as the first reported marker of pre-hematopoietic mesoderm inside the human embryo.

We have shown previously that definitive hematopoiesis in the human embryo stems from mesodermal precursors already present inside the human splanchnopleura at as early as 19 days of development.10 Because at that point, blood does not yet circulate, a contribution of the YS to this original stock of intraembryonic hematopoietic progenitors is unlikely.10 Cell-sorting and differentiation experiments have shown hemogenic endothelial cells to be at the immediate origin of hematopoietic cell clusters sprouting from the ventral side of the aorta at 28-40 days.14 Vascular endothelial cells sorted from the same territory at an earlier stage (24-26 days) are not yet hematopoietic; blood-forming potential in the human splanchnopleura is associated, at that time, with CD34−, non-endothelial cells (M.T. and B.P., personal observations, April 2007), suggesting the colonization of the ventral wall of the aorta from day 27 by angio-hematopoietic precursors. The results of the present study strongly support this hypothesis and designate ACE/BB9 as the first known marker of these ancestral progenitors (Figure 1 and supplemental Figure 1). Purified splanchnopleural ACE+ cells indeed generate colonies of CD45+ hematopoietic cells at a frequency more than 40 times higher than that observed when plating ACE− cells. Therefore, our data suggest that definitive hematopoiesis arises inside the human embryo from intrinsic mesodermal precursors identifiable by the ACE/BB9 Ab. Accordingly, the mouse hemogenic ventral aortic endothelium is derived from a transient mesenchymal cell population29 that is likely related to the sub-aortic patches16 expressing CD31 and AA4.1 and lacking CD45.7 However, we detected expression of neither CD31 or CD93 at the surface of human splanchnopleural ACE-expressing cells nor of leukosialin (CD43), which normally defines the early hematopoietic commitment of hESCs.30 In contrast, the majority of ACE+ cells express a marker of stem cell pluripotency, Oct-4A,31 which is a variant of the transcription factor Oct-4 and surface Ag SSEA-1 (Figure 4). Oct-4 is expressed in embryonic stem cells and by stem cells from amniotic fluid, neonatal human cord blood, and adult nonhematopoietic organs32-34 ; however, the association of Oct4 and SSEA-1 in humans is assumed to be restricted to primordial germ cells (PGCs).35 PGCs migrate from the posterior part of the embryo to reach the genital ridges that run adjacent to kidney anlagen and therefore are included within the AGM region. PGC migration occurs at the same stage of development as that at which we have detected ACE+ cells in the splanchnopleura before the emergence of aortic hematopoietic cell clusters.36,37 Therefore, the ACE+Oct-4+SSEA-1+ cells we identified within the human embryo represent a phenotype compatible with that of PGC. Although there is a germinal isoform of the ACE protein that is expressed on germ cells after meiosis,38 the presence of ACE at the surface of migrating PGCs had not been described so far and supports the possibility that HSCs and PGCs follow related developmental pathways.39,40 However, our results with KDR expression indicate that the ACE+ cells that we describe here are not exclusively PGCs, but also include a different cell population that might be responsible for hematopoietic activity. Indeed, as shown in Figure 5, only some of ACE+ cells are KDR+, indicating that they are a heterogeneous population. This is consistent with our previous identification of KDR as a marker of a subset of CD34− hemangioblasts within the P-Sp before the emergence of intra-aortic hematopoietic cell clusters.6 Furthermore, at later stages of development, ACE marks hematopoietic progenitors associated with the ventral side of the aorta and subjacent endothelial cells, further supporting an affiliation between the endothelial and hematopoietic cell lineages in the AGM region.12-14 In the embryo, in contrast to the adult, the only endothelial cells expressing ACE are seen in the blood-forming aorta, consistent with the hypothesis that hemangioblasts could develop in this territory. In a parallel study, we have confirmed that ACE is a marker for hemangioblasts derived from hESCs.22 hESC-derived ACE+CD45−CD34+/− cells are common YS-like progenitors for endothelium and both primitive and definitive human lympho-hematopoietic progenitors. Therefore, we speculate that both ACE+ hematopoietic precursors and PGCs would migrate into the dorsal mesentery and give rise to lympho-hematopoietic progenitors in the ventral wall of the aorta and gametes in the gonads, respectively. In support of this view, we have detected the CXCR4 protein at the surface of ACE+ cells and the polarized expression of SDF-1 in the ventral domain of the AGM region, the target of migrating ACE+ cells. Interestingly, the expression of this chemokine is tightly correlated with hematopoietic activity in the human embryo, implying a major role for SDF-1/CXCR4 in the establishment of intra-aortic hematopoiesis.

Finally, ACE expression accompanies the emergence of hematopoiesis in all human blood-forming organs. Indeed, ACE+ cells were detected in both the liver and BM at stages of hematopoiesis incipience. The results of long-term cultures and transplantation into NOD/SCID mice demonstrate that hepatic and medullary CD34+ACE+ cell progenitors, but not CD34+ cells lacking expression of ACE, are endowed with long-term culture-initiating cell potential and sustain multilineage hematopoietic cell engraftment. The frequencies of these progenitors in both liver and BM are clearly correlated with the changing blood-forming potentials of these organs during development.

In conclusion, the findings from the present study support our previous studies on cord blood and adult BM and confirm ACE/BB9 as a marker of HSCs at the fetal and postnatal stages.17,18 What may be the unrecognized role of ACE and/or the RAS in the emerging blood system? Mice in which the gene encoding ACE has been inactivated are anemic41 ; furthermore, angiotensin II (Ang II), the effector element of the RAS, stimulates erythroid-cell proliferation, increasing the effect of erythropoietin or other growth factors in culture.42 Based on these observations, the existence of a local RAS controlling hematopoiesis in the BM was hypothesized, and it has been suggested that the latter could exert effects not only on erythroid progenitors, but also on primitive pluripotent HSCs (for a review, see Haznedaroglu and Ozturk43 ). In the adult BM, the Ang II type 1 receptor is present on CD34+CD38− cells, CD34+CD38+ cells, lymphocytes, and stromal cells, and Ang II may have a positive effect on hematopoiesis by directly activating HSC proliferation or by indirectly activating growth factor synthesis by stromal cells.44 Furthermore, ACE directly favors the recruitment of primitive stem cells into the S-phase by degrading the acetyl-N-Ser-Asp-Lys-Pro tetrapeptide, a reversible negative regulator of HSC proliferation.45 A locally active RAS in YS blood islands also modulates YS primitive erythropoiesis in the chicken embryo.46 Although the existence of a local RAS-like system in mammalian embryos has not yet been described, our studies document for the first time ACE production during early human embryogenesis in all blood-forming sites, hinting at the role of this enzyme in the physiologic regulation of hematopoiesis.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Laure Coulombel, Paul Simmons, Pierre Corvol, and Jean-Marie Gasc for their support and advice; Israël Nisand for providing human embryonic tissues; and Denis Clay for excellent assistance with flow cytometry.

This work was supported by Inserm (Avenir Project) and by grants from the Association pour la Recherche Contre le Cancer (no. 4814) and Ligue Contre le Cancer to M.T. L.S. was the recipient of fellowships from Ministère de l'Education Nationale, de la Recherche et de la Technologie, Association Nouvelle Recherche Biomédicale, and Association pour la Recherche contre le Cancer. K.B. was awarded a fellowship from Inserm-Alsace and from Société Française d'Hématologie.

Authorship

Contribution: L.S. designed and performed the research and analyzed and interpreted the data; K.B. performed the experiments, produced some of the figures, and analyzed and interpreted the data; I.K. performed the experiments; B.P. initiated the project with M.T. and drafted and revised the manuscript; and M.T. designed and performed the research, analyzed and interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation for I.K. is Inserm U1004, Villejuif, France.

Correspondence: Manuela Tavian, Inserm UMR-S 949, EFS-Alsace; 10, rue Spielmann, F-67065 Strasbourg cedex, France; e-mail: manuela.tavian@inserm.fr.

References

Author notes

L.S. and K.B. contributed equally to this work.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal