Abstract

The inv(16)(p13q22)/t(16;16)(p13;q22) in acute myeloid leukemia results in multiple CBFB-MYH11 fusion transcripts, with type A being most frequent. The biologic and prognostic implications of different fusions are unclear. We analyzed CBFB-MYH11 fusion types in 208 inv(16)/t(16;16) patients with de novo disease, and compared clinical and cytogenetic features and the KIT mutation status between type A (n = 182; 87%) and non–type A (n = 26; 13%) patients. At diagnosis, non–type A patients had lower white blood counts (P = .007), and more often trisomies of chromosomes 8 (P = .01) and 21 (P < .001) and less often trisomy 22 (P = .02). No patient with non–type A fusion carried a KIT mutation, whereas 27% of type A patients did (P = .002). Among the latter, KIT mutations conferred adverse prognosis; clinical outcomes of non–type A and type A patients with wild-type KIT were similar. We also derived a fusion-type–associated global gene-expression profile. Gene Ontology analysis of the differentially expressed genes revealed—among others—an enrichment of up-regulated genes involved in activation of caspase activity, cell differentiation and cell cycle control in non–type A patients. We conclude that non–type A fusions associate with distinctclinical and genetic features, including lack of KIT mutations, and a unique gene-expression profile.

Key Points

Patients with inv(16) non–type A CBFB-MYH11 fusions lack KIT mutations and have distinct clinical and cytogenetic features.

inv(16) non–type A fusions have a distinct gene-expression profile with upregulation of genes associated with apoptosis, differentiation, and cell cycle.

Introduction

Approximately 5%-7% of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients have an inv(16)(p13q22) or t(16;16)(p13;q22) [hereafter referred to as inv(16)/t(16;16)].1-3 This cytogenetic group is usually associated with high complete remission (CR) rates and a relatively favorable outcome, especially when treated with repetitive cycles of high-dose cytarabine as consolidation therapy.4,5 However, 30%-40% of these patients experience relapse.6-10 We and others reported that the presence of a KIT mutation confers worse outcome in inv(16)/t(16;16) patients.10-12

Molecularly, inv(16)/t(16;16) results in the juxtaposition of the myosin, heavy chain 11, smooth muscle gene (MYH11) at 16p13 and the core-binding factor, β subunit gene (CBFB) at 16q22, and creation of the CBFB-MYH11 fusion gene.13,14 Because of the variability of the genomic breakpoints within CBFB and MYH11, more than 10 differently sized CBFB-MYH11 fusion transcript variants have been reported.15,16 More than 85% of fusions are type A, and 5%-10% each are type D and type E fusions.15-20 Fusion types B, C, and F-K have been reported mostly in single cases.15-20

To our knowledge, only one study examined the biologic and clinical significance of different CBFB-MYH11 fusions, but did not characterize the KIT mutation status.18 Here, we report the frequency of CBFB-MYH11 fusion transcripts, their associations with cytogenetic and clinical characteristics, KIT mutation status, and the fusion transcripts impact on prognosis in a relatively large cohort of patients with de novo inv(16)/t(16;16) AML. Furthermore, to gain insights into the biologic and functional differences of the distinct fusion types, we derived a fusion-type specific genome-wide gene-expression profile.

Methods

Patients and treatment

Two hundred eight patients aged 17-74 years with inv(16)/t(16;16) de novo AML, who were enrolled on Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB; n = 206) or Southwest Oncology Group (SWOG; n = 2) frontline treatment protocols (for details please see supplemental Methods, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article) and had pretreatment material available, were analyzed for the CBFB-MYH11 fusion type. Of these patients 147 patients enrolled on CALGB protocols that required ≥ 3 cycles of high-dose cytarabine-based consolidation treatment were eligible for outcome analyses. All patients provided written Institutional Review Board–approved informed consent for participation in these studies in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Cytogenetics, determination of fusion type, and KIT mutation status

For all 208 patients, pretreatment cytogenetic analyses of bone marrow (BM) or blood were performed by CALGB-approved institutional cytogenetic laboratories as part of CALGB 8461, and the results were reviewed centrally.21 Three patients did not have mitoses on karyotype analysis, but were RT-PCR positive for CBFB-MYH11, and thus included in this study.

The CBFB-MYH11 fusion types were determined for all 208 patients centrally in the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments–certified Molecular Pathology Laboratory at The Ohio State University, as previously described.22 The presence of mutations in KIT exons 8 and 17 was also determined centrally in pretreatment BM or blood, as previously described.11

Gene-expression profiling

For gene-expression profiling, total RNA was extracted from pretreatment BM or blood mononuclear cells. Gene-expression profiling was performed using the Affymetrix U133 plus 2.0 microarray (Affymetrix; ArrayExpress accession: E-MTAB-1356) as previously reported.23,24 Briefly, summary measures of gene expression were computed for each probe-set using the robust multichip average method, which incorporates quantile normalization of arrays. Expression values were logged (base 2) before analysis. A filtering step was performed to remove probe-sets that did not display significant variation in expression across arrays. In this procedure, a χ2 test was used to test whether the observed variance in expression of a gene was significantly larger than the median observed variance in expression for all genes, using α = .01 as the significance level. A total of 6747 genes passed the filtering criterion.

Normalized expression values were compared between type A and non–type A fusion inv(16)/t(16;16) patients and a univariable significance level of .001 was used to identify differentially expressed genes (all genes had false detection rate ≤ 0.05).

Gene Ontology (GO) analysis to assess enrichment of genes associated with distinct biologic processes for up- and down-regulated genes in non–type A inv(16)/t(16;16) patients compared with type A inv(16)/t(16;16) patients was conducted using a hypergeometric test and Cytoscape.25 P values were corrected for multiple testing using the false detection rate according to Benjamini-Hochberg.

Definition of clinical end points and statistical analysis

The main objective of this study was to evaluate the frequency of distinct CBFB-MYH11 fusion transcripts (we applied the nomenclature of fusion transcripts according to van Dongen et al17 ), their associations with cytogenetic and clinical characteristics, and KIT mutation status, and their prognostic impact in a relatively large set of patients with de novo AML and inv(16)/t(16;16). The differences among patients in their baseline cytogenetics, KIT mutation status, demographic and clinical features according to their fusion transcript type were tested using the Fisher exact and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for categorical and continuous variables, respectively.

A subset of 147 patients who were enrolled on protocols requiring at least 3 cycles of high-dose cytarabine-based postremission treatment, were eligible for outcome analyses. These patients had similar pretreatment characteristics to the total set of 208 patients studied (supplemental Table 1). Material to determine the pretreatment KIT mutation status was available for 141 of these 147 patients. CR was defined as recovery of morphologically normal BM and blood counts (ie, neutrophils ≥ 1.5 × 109/L and platelets > 100 × 109/L), and no circulating leukemic blasts or evidence of extramedullary leukemia for more than one month. CR rates were compared using the Fisher exact test. Cumulative incidence of relapse (CIR) was measured from the date of CR until relapse. Patients alive without relapse were censored, whereas those who died without relapse were counted as a competing cause of failure. Overall survival (OS) was measured from the date of study entry until date of death. Patients alive at last follow-up were censored for OS. Event-free survival (EFS) was measured from the date of study entry until induction failure, relapse or death, regardless of cause; patients alive and in CR were censored at last follow-up. Estimates of CIR were calculated, and the Gray k-samples test26 was used to evaluate differences in relapse rates. Estimated probabilities of OS and EFS were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and the log-rank test evaluated differences between survival distributions. The Holm step-down procedure and Sidak adjustment were used to adjust P values for the multiple comparisons analyses of fusion type by KIT status for CR and survival analyses, respectively.27 The dataset was locked on September 24, 2012.

For the gene-expression profiling, summary measures of gene expression were computed, normalized, and filtered. The inv(16)/t(16;16) fusion-type-associated signature was derived by comparing gene expression between type A and non–type A patients with wild-type KIT. Univariable significance levels of .001 for gene-expression profiling were used to determine the probe-sets that constituted the signature.

All analyses were performed by the Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology Statistics and Data Center.

Results

Frequency and associations of inv(16)/t(16;16) fusion types with clinical characteristics and KIT mutation status in de novo inv(16)/t(16;16) AML patients

In our study, 182 (87%) patients with inv(16)/t(16;16) AML had a type A fusion, whereas 26 (13%) harbored a non–type A fusion. Eighteen (9%) patients harbored a type E fusion, 6 (3%) a type D fusion, and 2 (1%) harbored other fusion types (Table 1; supplemental Figure 1). There was no significant difference in non–type A fusion frequencies between patients with inv(16) and those with t(16;16) (13% vs 6%; P = .70).

Frequencies of CBFB-MYH11 fusion types among 208 patients with inv(16)/t(16;16) AML in our study and 162 patients reported by Schnittger et al18

| Fusion type . | This study (n = 208)* . | Schnittger et al18 (n = 162)† . | P‡ . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. . | % . | No. . | % . | ||

| Type A | 182 | 87 | 128 | 79 | .03 |

| Type E | 18 | 9 | 8 | 5 | .22 |

| Type D | 6 | 3 | 16 | 10 | .007 |

| Other types | 2§ | 1 | 10‖ | 6 | .006 |

| Fusion type . | This study (n = 208)* . | Schnittger et al18 (n = 162)† . | P‡ . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. . | % . | No. . | % . | ||

| Type A | 182 | 87 | 128 | 79 | .03 |

| Type E | 18 | 9 | 8 | 5 | .22 |

| Type D | 6 | 3 | 16 | 10 | .007 |

| Other types | 2§ | 1 | 10‖ | 6 | .006 |

AML indicates acute myeloid leukemia.

All patients were diagnosed with de novo AML.

One hundred thirty-eight patients were diagnosed with de novo AML and 24 patients with treatment-related AML. Within the de novo AML cohort, 83% had type A fusions; frequencies for other fusion types within this cohort were not provided.

P values are from the Fisher exact test.

Both fusions were type I (n = 2).

These were the following fusion types: Avar (n = 1), Bvar (n = 1), F (n = 1), G (n = 2), H (n = 1), J (n = 2), and S/L (n = 2).

Pretreatment characteristics of our patients are presented in Table 2. Non–type A patients had lower white blood counts (WBC; P = .007) at diagnosis. Most patients, 60% (n = 124), had inv(16) or t(16;16) as a sole chromosome abnormality, whereas 40% (n = 81) had ≥ 1 secondary abnormality. Non–type A patients more often had a secondary abnormality than type A patients (58% vs 37%; P = .07; Table 2). Non–type A patients more frequently had +8 (P = .01) and +21 (P < .001) than type A patients. However, none of the non–type A patients had +22, whereas 19% of the type A patients did (P = .02, Table 2). Forty-eight (24%) of inv(16)/t(16;16) patients harbored KIT mutations. Interestingly, they were detected exclusively in type A patients, with none of the non–type A patients carrying a KIT mutation (27% vs 0%; P = .002, Table 2).

Clinical and cytogenetic characteristics and KIT mutation status according to CBFB-MYH11 fusion type in 208 patients with de novo AML and inv(16)/t(16;16)

| Characteristic . | Non–type A fusion* (n = 26) . | Type A fusion (n = 182) . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | .75 | ||

| Median | 41 | 41 | |

| Range | 22-62 | 17-74 | |

| Sex, no. of males (%) | 14 (54) | 113 (62) | .52 |

| Race, no. (%) | .56 | ||

| White | 20 (77) | 149 (82) | |

| Nonwhite | 6 (23) | 33 (18) | |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | .42 | ||

| Median | 8.9 | 8.8 | |

| Range | 6.6-13.0 | 3.1-14.8 | |

| Platelet count, × 109/L | .33 | ||

| Median | 46 | 42 | |

| Range | 15-208 | 7-272 | |

| WBC, × 109/L | .007 | ||

| Median | 21.9 | 33.8 | |

| Range | 1.4-87.2 | 0.4-500.0 | |

| Percentage of blood blasts | .26 | ||

| Median | 43 | 52 | |

| Range | 3-93 | 0-97 | |

| Percentage of BM blasts | .59 | ||

| Median | 53 | 58 | |

| Range | 22-93 | 2-89 | |

| FAB (centrally reviewed), no. (%) | .04 | ||

| M1 | 3 (14) | 2 (1) | |

| M2 | 0 (0) | 8 (5) | |

| M4 | 4 (19) | 21 (14) | |

| M4Eo | 14 (67) | 121 (78) | |

| M5 | 0 (0) | 3 (2) | |

| Cytogenetic characteristics‡ | |||

| sole inv(16)/t(16;16), no. (%) | 10 (42) | 114 (63) | .07 |

| +8, no. (%) | 7 (29) | 18 (10) | .01 |

| +13, no. (%) | 2 (8) | 3 (2) | .11 |

| +21, no. (%) | 6 (25) | 1 (1) | < .001 |

| +22, no. (%) | 0 (0) | 35 (19) | .02 |

| KIT, no. (%)§ | .002 | ||

| Mutated | 0 (0) | 48 (27) | |

| Wild-type | 24 (100) | 130 (73) |

| Characteristic . | Non–type A fusion* (n = 26) . | Type A fusion (n = 182) . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | .75 | ||

| Median | 41 | 41 | |

| Range | 22-62 | 17-74 | |

| Sex, no. of males (%) | 14 (54) | 113 (62) | .52 |

| Race, no. (%) | .56 | ||

| White | 20 (77) | 149 (82) | |

| Nonwhite | 6 (23) | 33 (18) | |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | .42 | ||

| Median | 8.9 | 8.8 | |

| Range | 6.6-13.0 | 3.1-14.8 | |

| Platelet count, × 109/L | .33 | ||

| Median | 46 | 42 | |

| Range | 15-208 | 7-272 | |

| WBC, × 109/L | .007 | ||

| Median | 21.9 | 33.8 | |

| Range | 1.4-87.2 | 0.4-500.0 | |

| Percentage of blood blasts | .26 | ||

| Median | 43 | 52 | |

| Range | 3-93 | 0-97 | |

| Percentage of BM blasts | .59 | ||

| Median | 53 | 58 | |

| Range | 22-93 | 2-89 | |

| FAB (centrally reviewed), no. (%) | .04 | ||

| M1 | 3 (14) | 2 (1) | |

| M2 | 0 (0) | 8 (5) | |

| M4 | 4 (19) | 21 (14) | |

| M4Eo | 14 (67) | 121 (78) | |

| M5 | 0 (0) | 3 (2) | |

| Cytogenetic characteristics‡ | |||

| sole inv(16)/t(16;16), no. (%) | 10 (42) | 114 (63) | .07 |

| +8, no. (%) | 7 (29) | 18 (10) | .01 |

| +13, no. (%) | 2 (8) | 3 (2) | .11 |

| +21, no. (%) | 6 (25) | 1 (1) | < .001 |

| +22, no. (%) | 0 (0) | 35 (19) | .02 |

| KIT, no. (%)§ | .002 | ||

| Mutated | 0 (0) | 48 (27) | |

| Wild-type | 24 (100) | 130 (73) |

FAB indicates French-American-British classification; and WBC, white blood count.

Type E (n = 18), type D (n = 6), type I (n = 2).

Patients may have multiple secondary abnormalities and thus can be classified in more than 1 category; 3 patient samples had no mitoses.

Six patients (2 with non–type A and 4 with type A fusions) had no material available to study KIT mutations and thus have an unknown KIT mutation status.

Genome-wide gene-expression profiling

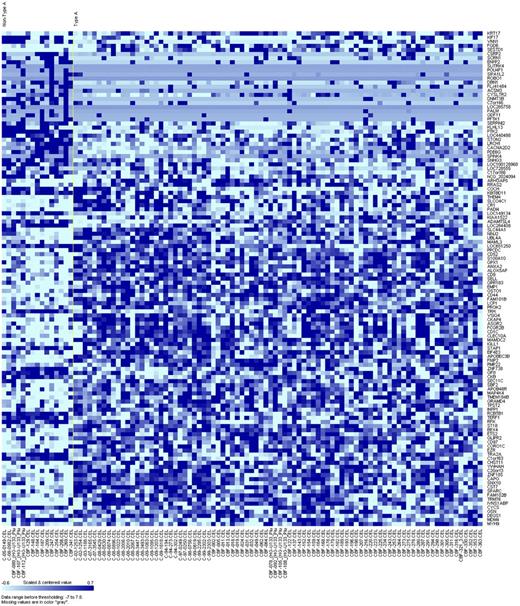

To gain further insights into the biology of inv(16)/t(16;16) AML with different fusion types, we derived a genome-wide gene-expression signature. To avoid bias associated with the unequal distribution of KIT mutations between type A and non–type A fusion inv(16)/t(16;16) patients, and because KIT mutations have been shown to be associated with a distinct gene-expression profile,28 we compared non–type A patients (n = 15) with those with type A fusion and wild-type KIT (n = 86). We observed the differential expression of 121 genes between non–type A and type A inv(16)/t(16;16) patients (Figure 1). Of these genes, 51 were up-regulated in non–type A patients (supplemental Table 2) and 70 were down-regulated (supplemental Table 3).

Heat map of the derived gene-expression signature associated with the CBFB-MYH11 fusion type (non–type A vs type A with wild-type KIT) in patients with de novo AML and inv(16)/t(16;16). Rows represent gene names and columns represent patients. Genes are ordered by hierarchical cluster analysis. Expression values of the genes are represented by color, with dark blue indicating higher expression and light blue indicating lower expression.

Heat map of the derived gene-expression signature associated with the CBFB-MYH11 fusion type (non–type A vs type A with wild-type KIT) in patients with de novo AML and inv(16)/t(16;16). Rows represent gene names and columns represent patients. Genes are ordered by hierarchical cluster analysis. Expression values of the genes are represented by color, with dark blue indicating higher expression and light blue indicating lower expression.

Among the up-regulated genes in non–type A inv(16)/t(16;16) patients, we found genes involved in differentiation, eg, GFI1 that encodes a transcriptional repressor contributing to myeloid differentiation29,30 ; epigenetics, eg, DNMT3B that encodes one of the isoforms of DNA methyltransferases mediating DNA methylation and gene silencing31 ; and apoptosis, eg, CYCS that encodes the small heme protein cytochrome C that is associated with cellular apoptosis.32,33 Among the down-regulated genes in non–type A inv(16)/t(16;16) patients, we found genes involved in kinase pathways, eg, CD9 that encodes a member of the transmembrane 4 superfamily that has been shown to physically interact with the aforementioned tyrosine kinase receptor KIT,34 and CD52, that encodes a surface protein with not fully elucidated function, but that is expressed on neutrophils and hematologic stem cells and targeted by alemtuzumab.35 We also observed lower expression of MYH9, a gene frequently linked to inheritable thrombocytopenia,36 and of SPARC, a gene found to be also down-regulated in AML with MLL-rearrangements.37

To focus on the functional differences of the different inv(16)/t(16;16) fusion types, we performed a Gene Ontology (GO) analysis and found an enrichment of genes involved in activation of caspase activity, positive regulation of cell differentiation, G0/G1 transition and G2/M transition in the up-regulated genes of non–type A inv(16)/t(16;16) patients (supplemental Table 4). Among the genes down-regulated in non–type A fusion inv(16)/t(16;16) patients, the GO analysis revealed enrichment of biologic processes related to actin cytoskeleton, ruffles, uropod, phosphoinositide binding, barbed-end actin filament capping, blood vessel endothelial cell migration, syncitium formation by plasma membrane fusion and tissue regeneration (supplemental Table 5). These results suggest a potentially less aggressive phenotype of non–type A inv(16)/t(16;16) AML.

Prognostic impact of the inv(16)/t(16;16) fusion type on clinical outcome

A subset (n = 147) of the 208 patients received high-dose cytarabine-based treatment and thus was eligible for outcome analyses. The CR rates (P = 1.00), CIR (P = .14), and OS (P = .36; supplemental Figure 2A) of non–type A patients (n = 19) and type A patients (n = 128) did not differ significantly (supplemental Table 6). However, non–type A patients tended to have longer EFS than type A patients (P = .05; 72% vs 50% at 5 years; supplemental Figure 2B).

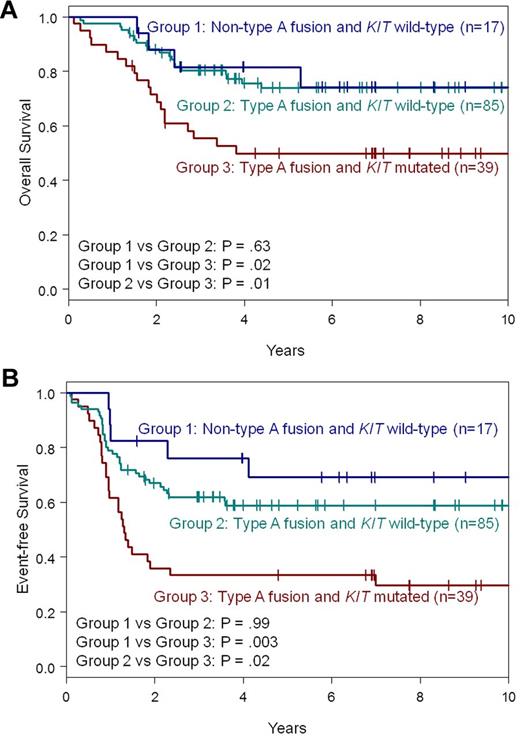

Because non–type A fusions and KIT mutations were mutually exclusive, we wondered whether the difference in EFS could be attributed to the different distribution of KIT mutations. Therefore, we compared the outcome of patients with non–type A fusions with that of type A fusion patients who had wild-type KIT (n = 85). In this analysis, non–type A patients behaved similarly to type A patients with wild-type KIT (Figure 2; supplemental Table 7). We did not find significant differences in CR rates (P = 1.00), CIR (P = .60), OS (P = .63; Figure 2A) or EFS (P = .99; Figure 2B), suggesting it was the presence or absence of KIT mutations that affected clinical outcome rather than the type of fusion transcript. Indeed, type A patients with mutated KIT had a shorter OS (P = .01; 50% vs 74% at 5 years; Figure 2A) and EFS (P = .02; 33% vs 59% at 5 years; Figure 2B) than type A patients with wild-type KIT. Likewise, both OS (P = .02; 50% vs 82% at 5 years; Figure 2A) and EFS were shorter (P = .003; 33% vs 69% at 5 years; Figure 2B) for KIT-mutated type A patients compared with non–type A patients. Thus, KIT mutations remain an important prognosticator in type A inv(16)/t(16;16) patients.

Survival of patients with de novo AML and inv(16)/t(16;16) according to CBFB-MYH11 fusion type (non–type A vs type A) and KIT mutation status. (A) OS. (B) EFS. All P-values from pairwise comparisons are adjusted for multiple comparisons.

Survival of patients with de novo AML and inv(16)/t(16;16) according to CBFB-MYH11 fusion type (non–type A vs type A) and KIT mutation status. (A) OS. (B) EFS. All P-values from pairwise comparisons are adjusted for multiple comparisons.

Discussion

AML patients with inv(16)/t(16;16) usually have favorable outcome. The resulting CBFB-MYH11 fusion gene results in various transcripts.15,16 However, the biologic and clinical significance of these different fusion types require further evaluation. In the presented study, 87% of de novo inv(16)/t(16;16) patients had a type A fusion, 13% harbored a non–type A fusion (18 had type E, 6 type D and 2 type I; Table 1, supplemental Figure 1). Schnittger et al, who also included treatment-related AML (t-AML) cases, reported a lower type A frequency of 79%18 (P = .03; Table 1). Since in the study by Schnittger et al treatment-related inv(16)/t(16;16) less often have type A fusions,18 we compared only de novo cases and found no significant difference in type A frequency between the 2 studies (87% vs 83%; P = .28). Although type E frequencies were similar (9% vs 5%; P = .22), type D (3% vs 10%; P = .007) and all other types combined (1% vs 6%; P = .006; Table 1) were more frequent in the Schnittger et al study.18 This finding may also be related to the inclusion of t-AML cases by Schnittger et al, who did not report on the individual non–type A frequencies in their de novo cases.18

Consistent with the study by Schnittger et al,18 non–type A patients in our study also had lower WBC. With respect to additional cytogenetic aberrations, in our study non–type A patients more often had a secondary abnormality than type A patients. While non–type A patients more frequently had +8 and +21 than type A patients, none of the non–type A patients had +22. Schnittger et al found that non–type A patients harbored +8, +21 and +22 less frequently,18 although a comparison of the individual trisomy frequencies with our data was not possible because they combined all trisomies into 1 subset. Because KIT mutations have been associated with inferior outcome in inv(16)/t(16;16) AML we analyzed the frequency of KIT mutations, and found that KIT mutations could not be detected in non–type A patients. This unexpected finding may have implications for treatment and risk-stratification of inv(16)/t(16;16) patients. Recently, mutated KIT was found to cooperate with the CBFB-MYH11 fusion toward leukemogenesis in mice.38 Our data suggest that this cooperation might be limited to type A fusion transcripts and that other cooperative events occur in inv(16)/t(16;16) AML with non–type A fusions.

To gain further biologic insights into the biology of inv(16)/t(16;16) AML with different fusion types, we performed a microarray analysis to assess differences in the genome-wide gene expression between patients with non–type A and type A fusion transcripts with wild-type KIT. We observed that patients with non–type A fusion showed an up-regulation of genes involved in the activation of caspase activity, cell differentiation and cell cycle control in addition to increased expression of other genes that have been previously linked to myeloid leukemogenesis, including GFI1 or DNMT3B.29-31 In addition, we observed that non–type A patients presented with down-regulation of CD9, a gene involved in mechanisms of activation of the receptor tyrosine kinase KIT, which is often found mutated or aberrantly expressed in inv(16)/t(16;16) AML,34 and MYH9 that has been previously linked with inheritable thrombocytopenia.36 How the differential expression of these genes ultimately impact on the leukemia phenotype, clinical characteristics and outcome of non–type A inv(16)/t(16;16)–patients remains unknown and should be studied in preclinical models to test the hypothesis that novel treatment strategies can be tailored to the type of fusion transcript in inv(16)/t(16;16) AML. It is interesting, however, that the GO analysis suggested a less aggressive phenotype for non–type A inv(16)/t(16;16)–leukemia, given the activation of genes involved in cell differentiation, cell cycle regulation and apoptosis and conversely the down-regulation of genes potentially involved in angiogenesis and cell migration.

In conclusion, non–type A CBFB-MYH11 fusion transcripts occur in a subset (13%) of inv(16)/t(16;16) patients. Although the fusion type does not impact on outcome of inv(16)/t(16;16) patients, the presence of non–type A fusions is associated with distinct clinical and genetic characteristics, as well as a distinct global gene-expression profile. KIT mutations, not found in non–type A patients but occurring in more than one-fourth of type A patients, conferred adverse prognosis among the latter. The biologic and therapeutic implications of these findings remain to be investigated, especially in the context of tyrosine kinase inhibitors targeting KIT being used in current clinical trials for inv(16)/t(16;16) patients (eg, NCT01238211 and NCT00416598).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

Presented in part at the 53rd Annual Meeting of the American Society of Hematology, San Diego, CA, December 11, 2011, and published in abstract form.39

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Donna Bucci of the CALGB Leukemia Tissue Bank at The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center, Columbus, OH, for sample processing and storage services, and Lisa Sterling and Christine Finks for data management.

This work was supported in part by National Cancer Institute grants CA101140, CA114725, CA140158, CA31946, CA33601, CA16058, CA77658, and CA129657, and by the Coleman Leukemia Research Foundation. A.-K.E. was supported by the Pelotonia Fellowship Program, and H.B. by the Deutsche Krebshilfe–Dr Mildred Scheel Cancer Foundation. S.V. was supported by the Associazione Italiana Ricerca sul Cancro.

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: S.S., C.G.E., G.M., and C.D.B. designed the study; S.S., C.G.E., K. Mrózek, G.M., and C.D.B analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript; S.S., Y.-Z.W., P.P., A.-K.E., P.H., H.B., K.H.M., J.C., and T.W.P performed the laboratory-based research; D.N., S.V., K. Maharry, and J.K. performed the statistical analyses; J.E.K., W.B., M.J.P., P.D.C., A.J.C., M.A.C., R.A.L., G.M., and C.D.B. were involved directly or indirectly in the care of patients and/or sample procurement; and all authors read and agreed on the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Clara D. Bloomfield, MD, The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center, 1216 James Cancer Hospital, 300 West 10th Ave, Columbus, OH 43210; e-mail: clara.bloomfield@osumc.edu; or Guido Marcucci, MD, The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center, 410 Biomedical Research Tower, 460 West 12th Ave, Columbus, OH 43210; e-mail: guido.marcucci@osumc.edu.

References

Author notes

S.S. and C.G.E. contributed equally to this work.

G.M. and C.D.B. are co–senior authors and contributed equally to this work.