Key Points

In pediatric AML, patterns of Stat3 activation by G-CSF and IL-6 can be identified that are associated with survival.

Such functional information may be useful for risk assessment and for determining which patients may benefit from alternative therapies.

Abstract

Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (Stat3) and Stat5 are critical signaling intermediates that promote survival in myeloid leukemias. We examined Stat3 and Stat5 activation patterns in resting and ligand-stimulated primary samples from pediatric patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Phosphorylated Stats were measured by FACS before and after stimulation with increasing doses of granulocyte-colony stimulating factor or IL-6. We also measured positive and negative regulators of Stat signaling, and we compared the variation in multiple parameters to identify biologic relationships. Levels of constitutively phosphorylated Stats were variable and did not correlate with survival. In terms of induced phospho-Stats, 15 of 139 specimens (11%) phosphorylated Stat3 in response to moderate doses of both granulocyte-colony stimulating factor and IL-6. Compared with groups that were resistant to 1 or both ligands, this pattern of dual sensitivity was associated with a superior outcome, with a 5-year event-free survival of 79% (P = .049) and 5-year overall survival of 100% (P = .006). This study provides important and novel insights into the biology of Stat3 and Stat5 signaling in acute myeloid leukemia. Patterns of ligand sensitivity may be valuable for improving risk identification, and for developing new agents for individualized therapy.

Introduction

Changes in gene expression, in both normal and malignant cells, are mediated by signal transduction pathways carrying information from the cell's environment to the nucleus. In cancer cells, signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (Stat3) is among the most critical of the signal transducers regulating oncogenic gene expression. In response to cytokine or growth factor stimulation, Stat3 is phosphorylated on tyrosine 705 (pY-Stat3), resulting in dimerization, nuclear translocation, and binding to DNA regulatory elements. Stat3 also is phosphorylated on serine 727 (pS-Stat3), which may augment transactivation.1 Stat3 targets include anti-apoptosis genes, cell-cycle regulators, and angiogenesis factors. Increased Stat3 activity in leukemia cells contributes to therapy resistance.2,3 Thus, it is no surprise that aberrant Stat3 activity is associated with more aggressive disease across a variety of malignancies.4-6

In acute myeloid leukemia (AML), increased constitutive pY-Stat3, as detected by Western blot or electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA), has been reported in 21% to 76% of adult patients4,7-10 and was associated with shorter time to relapse.4 Likewise, increased constitutive pY-Stat5, as is reported with the FLT3 internal tandem duplication (FLT3/ITD), is associated with poor outcome.11,12 More recently, we and others have measured phosphorylated Stat proteins in AML samples by intracellular flow cytometry (phospho-flow).13-17 This highly sensitive method yields quantitative information at the single-cell level.

We undertook a comprehensive analysis of Stat3 and Stat5 signaling patterns in a large cohort of primary pediatric AML samples from the Children's Oncology Group (COG). We measured both constitutive and ligand-induced pY-Stat3, pS-Stat3, and pY-Stat5. We further identified specific patterns of constitutive and ligand-induced Stat3/5 activation, and correlated these patterns with the expression of various upstream and downstream regulators of Stat3/5 activity, including pY418-Src, surface granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) receptor and gp130, and Suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 (SOCS3) and Src homology phosphatase-1 (SHP1) expression. Among all the signaling parameters measured, we found that the sensitivity of the pY-Stat3 response to G-CSF and IL-6 stimulation correlated with event-free and overall survival. Thus, while much information exists regarding gene expression and mutation profiles and AML prognosis, this is the first comprehensive analysis of functional signaling activities in pediatric AML and their potential roles in clinical outcome.

Methods

Cells

Cryopreserved bone marrow samples from 175 pediatric patients with de novo AML were obtained from the Children's Oncology Group (COG) AML Reference Laboratory. All were enrolled on the treatment protocol CCG 2961 and gave written informed consent, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, for banking of bone marrow for future research. The treatment regimen and outcomes for this study have been reported.18 Consecutive samples with multiple vials in the Reference Bank were selected. Bone marrow samples were enriched for mononuclear cells by density centrifugation and cryopreserved.

Normal bone marrow (NBM) was obtained from healthy individuals donating bone marrow for patients at Texas Children's Hospital, under an institutional review board–approved protocol for the use of anonymized remainder tissue. No identifying information or clinical data were collected for these donors. Leftover bone marrow cells were obtained by rinsing the collection filter after the marrow had been removed for clinical processing. Mononuclear cells were enriched by density centrifugation and cryopreserved.

The human AML cell line Kasumi-1 was used as the positive control for all flow cytometry studies, and as the interblot reference for the immunoblot studies. Kasumi-1 cells were obtained from ATCC, and grown in RPMI (ATCC) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Invitrogen), and 100 units/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (pen/strep; Invitrogen). Kasumi-1 cells were grown in a humidified 37°C incubator with 5% CO2. These studies were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Baylor College of Medicine.

Flow cytometry

Samples were thawed into Iscove modified Dulbecco medium (IMDM; HyClone) with 10% FBS, washed once in IMDM + 10% FBS to remove residual DMSO, then resuspended in serum-free StemSpan H3000 (StemCell Technologies) and rested for 2 hours. Cell viability after the rest period was determined by Trypan Blue dye exclusion. Twenty-six samples with viability < 75% were not processed further, and 10 samples were excluded for insufficient cell number or other technical reasons. Ultimately, 139 samples were suitable for analysis. Age of the sample was not found to be a factor in cell viability. Cells were distributed at 2-3 × 105 cells/well in 10 aliquots. Four aliquots remained unstimulated; 3 were stimulated with G-CSF (Filgrastim; Amgen) at 1, 10, and 100 ng/mL, and 3 were stimulated with interleukin-6 (IL-6; BD Pharmingen) + soluble IL-6 receptorα (sIL-6R; R&D Systems) at 0.5 + 1, 5 + 10, and 50 + 100 ng/mL, respectively. When sufficient, remaining cells were used for Western blots.

After G-CSF or IL-6/sIL-6R stimulation at 37° for 15 minutes, cells were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized in 100% ice-cold methanol, as described.14 Cells were washed twice in staining buffer (DPBS pH 7.2 with 0.2% BSA and 0.09% sodium azide) and labeled for flow cytometry. All intracellular flow cytometry antibodies were purchased from BD Biosciences and included pY-Stat3-PE (clone 4/P-Stat3), pS-Stat3-Alexa Fluor 488, pY-Stat5–Alexa Fluor 647, pY418-Src–Alexa Fluor 488 (clone K98-37), and total Stat3-PE (clone M59-50) antibodies, as well as fluorochrome-conjugated isotype control antibodies. G-CSF receptor (CD114)–PE was from BD Biosciences and gp130 (CD130)–FITC (clone B-R3) was from Abcam. Fifty-five samples were additionally labeled with CD45-APC-H7 (clone 2D1) and CD33-PerCP-Cy5.5 (clone P67.6; BD Biosciences). Cells were stained for 30 minutes at room temperature, washed, and analyzed by flow cytometry (LSRII; BD Biosciences). Samples were gated on intact cells by forward light scatter (FSC) vs right-angle light scatter (SSC), and residual lymphocytes were excluded when this population was apparent by FSC vs SSC. For samples labeled for CD45, a second gating step on the blasts, based on CD45 vs SSC, was used. NBM sample gates were set similarly. Data were acquired with Diva (BD Biosciences) and analyzed with FlowJo software (TreeStar). Up to 4 patient samples were processed and analyzed at a time.

Kasumi-1 cells were used as positive controls for G-CSF and IL-6 activity. They were removed from serum-containing medium and rested in serum-free StemSpan H3000 for 2 hours, then processed simultaneously with the patient samples. Cells were divided into 4 aliquots for the isotype control, unstimulated pStats, G-CSF–induced pStats, and IL-6–induced pStats. Only the highest doses (dose level 3) were tested for the Kasumi-1 cells. Results of these control assays are presented in supplemental Figure 1 (available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

Western blot

Whole cell lysates were prepared and immunoblots were performed as described.14 Primary antibodies against human SOCS3 and SHP1 were purchased from Abcam. Bands were directly detected on an Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR Biosciences). Densitometry analysis was done with NIH Image J. Each densitometric value was normalized to the corresponding β-actin value. To account for differences in exposures between blots, each normalized value from an AML sample was divided by the normalized value from Kasumi-1 lysate run on the same gel.

Statistics

Median values of signaling parameters between AML and NBM samples were compared by the Mann-Whitney U test. Spearman rank correlations were used to assess relationships between 2 continuous variables (SPSS Version 19). Given a sample size of 139 and 2-sided α error of 0.05, this study had 80% power to detect a correlation of R = 0.234 or higher. The significance of observed differences in proportions was tested using the χ2 test and the Fisher exact test when data were sparse. Data were analyzed through November 6, 2009 for patients enrolled on CCG 2961. Estimates of the distributions of event-free (EFS) and overall survival (OS) from study entry were calculated by the Kaplan-Meier method. Estimates are reported with 95% confidence intervals (CI) that were computed using a log (−log) transformation. OS is defined as time from study entry to death from any cause. EFS is defined as time from study entry to induction failure, relapse, or death from any cause. EFS and OS were compared for significant differences by the log-rank test. The Cox proportional hazards model was used to estimate hazard ratios (HR) and to determine the prognostic value of the ligand response categories. Given a sample size of 139 and 2-sided α error of 0.05, this study had 80% power to detect EFS hazard ratios (HR) of 0.25 and 0.46 between 2 groups where the proportion of patients in one group is 10% and 50%, respectively. This study also had 80% power to detect OS HR of 0.28 and 0.49 between 2 groups where the proportion of patients in one group is 10% and 50%, respectively.

Results

Unstimulated Stat3/5 pathway parameters

One hundred thirty-nine primary samples from patients enrolled on the Children's Cancer Group CCG 2961 study were analyzed. The characteristics of this cohort, relative to the other patients enrolled on the study, are shown in Table 1. The inclusion of a higher number of older patients and patients with higher presenting WBC, compared with the unstudied patients, likely reflects the selection of samples with multiple vials in the COG AML Reference Bank, and has been reported previously.19 There were no significant differences in remission or survival rates between patients included in this study and those who were not. Unstimulated AML cells were examined by FACS for baseline levels of pY-Stat3, pS-Stat3, and pY-Stat5. Constitutive pY418-Src, total Stat3, G-CSF receptor (G-CSFR), and IL-6 receptor (gp130) also were measured by FACS. All samples were gated on the blast population. After establishing the negative region with isotype control antibodies, the percentage of positive events was measured for each sample and antigen (Figure 1A). We measured the same parameters, with similar gates, in 9 NBM mononuclear cell samples for comparison.

Patient characteristics

| . | FACS study (n = 139) . | Not studied (n = 762) . | P* . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N . | % . | N . | % . | ||

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 73 | 53 | 395 | 52 | .883 |

| Female | 66 | 47 | 367 | 48 | |

| Age, y | |||||

| Median (range) | 11.4 | (0.16-19.7) | 9.1 | (0.01-20.9) | .003 |

| 0-2 y | 21 | 15 | 229 | 30 | < .001 |

| 3-10 y | 45 | 32 | 215 | 28 | .320 |

| > 11 y | 73 | 53 | 318 | 42 | .018 |

| Race | |||||

| White | 93 | 69 | 490 | 65 | .434 |

| Black | 11 | 8 | 73 | 10 | .560 |

| Hispanic | 23 | 17 | 134 | 18 | .811 |

| Asian | 3 | 2 | 23 | 3 | .785 |

| Other | 5 | 4 | 29 | 4 | .926 |

| Unknown | 4 | 13 | |||

| WBC, ×103/μL | |||||

| Median (range) | 29.9 | (1.1-860) | 17.4 | (0.5-684) | < .001 |

| < 100 000 | 110 | 79 | 647 | 85 | .081 |

| ≥ 100 000 | 29 | 21 | 114 | 15 | |

| Bone marrow blast % | |||||

| Median (range) | 72 | (2-100) | 70 | (0-100) | .424 |

| FAB classification | |||||

| M0 | 7 | 5 | 48 | 6 | .545 |

| M1 | 23 | 17 | 127 | 17 | .923 |

| M2 | 39 | 28 | 210 | 28 | .972 |

| M4 | 47 | 34 | 159 | 21 | .001 |

| M5 | 19 | 14 | 139 | 19 | .173 |

| M6 | 1 | 1 | 19 | 3 | .344 |

| M7 | 2 | 1 | 45 | 6 | .028 |

| De novo (NOS) | 1 | 15 | |||

| Cytogenetics | |||||

| Normal | 16 | 17 | 109 | 23 | .225 |

| t(8;21) | 13 | 14 | 76 | 16 | .630 |

| Inv(16) | 17 | 18 | 32 | 7 | < .001 |

| Abnormal 11 | 27 | 29 | 105 | 22 | .144 |

| −7, −7q, −5, −5q | 4 | 4 | 24 | 5 | 1.000 |

| Other | 15 | 16 | 124 | 28 | .041 |

| Missing | 47 | 291 | |||

| FLT3/ITD | |||||

| No | 113 | 88 | 403 | 87 | |

| Unknown | 11 | 300 | |||

| CEBPα mutation | |||||

| Yes | 4 | 3 | 19 | 4 | .504 |

| No | 124 | 97 | 406 | 96 | |

| Unknown | 11 | 337 | |||

| NPM1 mutation | |||||

| Yes | 9 | 9 | 36 | 9 | .957 |

| No | 93 | 91 | 380 | 91 | |

| Unknown | 37 | 346 | |||

| Risk group† | |||||

| Favorable | 42 | 40 | 158 | 31 | .075 |

| Standard | 48 | 46 | 286 | 56 | .050 |

| High | 15 | 14 | 65 | 13 | .674 |

| Unknown | 34 | 253 | |||

| Treatment arm | |||||

| FLU-IDA | 54 | 48 | 317 | 51 | .636 |

| IDA-DCTR | 58 | 52 | 309 | 49 | |

| Did not participate | 27 | 136 | |||

| Course 1 response | |||||

| Complete remission | 105 | 76 | 597 | 80 | .253 |

| Not in remission | 33 | 24 | 146 | 20 | |

| . | FACS study (n = 139) . | Not studied (n = 762) . | P* . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N . | % . | N . | % . | ||

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 73 | 53 | 395 | 52 | .883 |

| Female | 66 | 47 | 367 | 48 | |

| Age, y | |||||

| Median (range) | 11.4 | (0.16-19.7) | 9.1 | (0.01-20.9) | .003 |

| 0-2 y | 21 | 15 | 229 | 30 | < .001 |

| 3-10 y | 45 | 32 | 215 | 28 | .320 |

| > 11 y | 73 | 53 | 318 | 42 | .018 |

| Race | |||||

| White | 93 | 69 | 490 | 65 | .434 |

| Black | 11 | 8 | 73 | 10 | .560 |

| Hispanic | 23 | 17 | 134 | 18 | .811 |

| Asian | 3 | 2 | 23 | 3 | .785 |

| Other | 5 | 4 | 29 | 4 | .926 |

| Unknown | 4 | 13 | |||

| WBC, ×103/μL | |||||

| Median (range) | 29.9 | (1.1-860) | 17.4 | (0.5-684) | < .001 |

| < 100 000 | 110 | 79 | 647 | 85 | .081 |

| ≥ 100 000 | 29 | 21 | 114 | 15 | |

| Bone marrow blast % | |||||

| Median (range) | 72 | (2-100) | 70 | (0-100) | .424 |

| FAB classification | |||||

| M0 | 7 | 5 | 48 | 6 | .545 |

| M1 | 23 | 17 | 127 | 17 | .923 |

| M2 | 39 | 28 | 210 | 28 | .972 |

| M4 | 47 | 34 | 159 | 21 | .001 |

| M5 | 19 | 14 | 139 | 19 | .173 |

| M6 | 1 | 1 | 19 | 3 | .344 |

| M7 | 2 | 1 | 45 | 6 | .028 |

| De novo (NOS) | 1 | 15 | |||

| Cytogenetics | |||||

| Normal | 16 | 17 | 109 | 23 | .225 |

| t(8;21) | 13 | 14 | 76 | 16 | .630 |

| Inv(16) | 17 | 18 | 32 | 7 | < .001 |

| Abnormal 11 | 27 | 29 | 105 | 22 | .144 |

| −7, −7q, −5, −5q | 4 | 4 | 24 | 5 | 1.000 |

| Other | 15 | 16 | 124 | 28 | .041 |

| Missing | 47 | 291 | |||

| FLT3/ITD | |||||

| No | 113 | 88 | 403 | 87 | |

| Unknown | 11 | 300 | |||

| CEBPα mutation | |||||

| Yes | 4 | 3 | 19 | 4 | .504 |

| No | 124 | 97 | 406 | 96 | |

| Unknown | 11 | 337 | |||

| NPM1 mutation | |||||

| Yes | 9 | 9 | 36 | 9 | .957 |

| No | 93 | 91 | 380 | 91 | |

| Unknown | 37 | 346 | |||

| Risk group† | |||||

| Favorable | 42 | 40 | 158 | 31 | .075 |

| Standard | 48 | 46 | 286 | 56 | .050 |

| High | 15 | 14 | 65 | 13 | .674 |

| Unknown | 34 | 253 | |||

| Treatment arm | |||||

| FLU-IDA | 54 | 48 | 317 | 51 | .636 |

| IDA-DCTR | 58 | 52 | 309 | 49 | |

| Did not participate | 27 | 136 | |||

| Course 1 response | |||||

| Complete remission | 105 | 76 | 597 | 80 | .253 |

| Not in remission | 33 | 24 | 146 | 20 | |

χ2 or Fisher exact test for comparisons with small numbers.

Risk group is determined by cytogenetics and presence or absence of FLT3/ITD, CEBPα, or NPM1 mutation. P values < .05 are shown in bold.

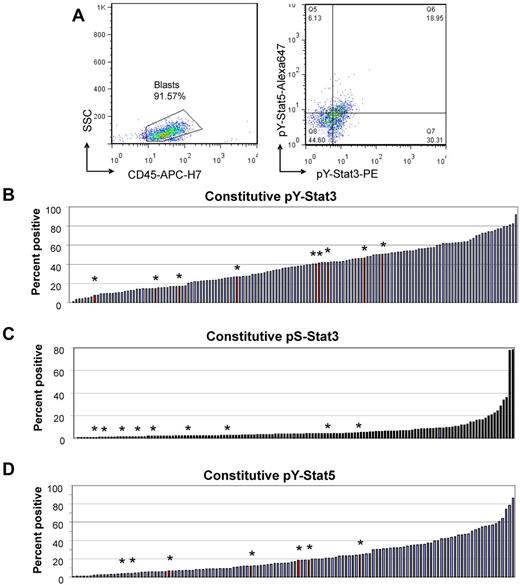

FACS analysis of Stat3 and Stat5 activity in unstimulated primary AML cells. (A) Representative example of data analysis. (Left) Fifty-five samples were additionally stained for CD45, allowing estimation of the blast percentage and exclusion of residual lymphocytes. (Right) Unstimulated cells had variable percentages of events in the pY-Stat3+ regions (top and bottom right quadrants) and pY-Stat5+ regions (top left and right quadrants). (B-D) Waterfall plots illustrate the distributions of values for baseline phosphorylated Stat3 and Stat5. The red bars with asterisks indicate the values for 9 normal bone marrow samples that were analyzed similarly. Values represent the percentage of events in the positive region.

FACS analysis of Stat3 and Stat5 activity in unstimulated primary AML cells. (A) Representative example of data analysis. (Left) Fifty-five samples were additionally stained for CD45, allowing estimation of the blast percentage and exclusion of residual lymphocytes. (Right) Unstimulated cells had variable percentages of events in the pY-Stat3+ regions (top and bottom right quadrants) and pY-Stat5+ regions (top left and right quadrants). (B-D) Waterfall plots illustrate the distributions of values for baseline phosphorylated Stat3 and Stat5. The red bars with asterisks indicate the values for 9 normal bone marrow samples that were analyzed similarly. Values represent the percentage of events in the positive region.

We found that constitutive pY-Stat3 and pY-Stat5 are common, and in some cases quite elevated, whereas constitutive pS-Stat3 is rare. Table 2 shows the medians and ranges of values for all parameters measured in unstimulated blasts and NBM. Waterfall plots illustrating the distribution of values for each parameter are presented in Figure 1B through D. Both pY-Stat3 and pY-Stat5 were detectable in AML and NBM samples, and there was no statistical difference in either parameter between AML and NBM. Although pS-Stat3 values were generally much lower than pY-Stat values, pS-Stat3 was significantly increased in AML compared with NBM (P = .01). Most AML samples had low levels of constitutive Src activation, but there was a distinct population of samples with increased basal pY418-Src, up to 40% (supplemental Figure 2A). Constitutive pY418-Src was generally low in NBM samples; 8 of the 9 samples had levels ≤ 5%. AML samples overexpressed total Stat3 relative to NBM samples (P = .002; supplemental Figure 2B).

Basal Stat3 and Stat5 signaling parameters in AML samples and normal bone marrow

| Parameter . | AML . | NBM . | P* . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N . | Median . | Range . | N . | Median . | Range . | ||

| Constitutive pY-Stat3, % positive | 139 | 37.19 | 0.11-91.84 | 9 | 40.51 | 7.69-50.57 | .490 |

| Constitutive pS-Stat3, % positive | 136 | 3.60 | 0.12-78.17 | 9 | 1.42 | 0.53-4.42 | .01 |

| Constitutive pY-Stat5, % positive | 123 | 16.78 | 0.5-86.54 | 7 | 11.94 | 3.79-24.22 | .21 |

| Constitutive pY-Src, % positive | 139 | 4.15 | 0.11-40.6 | 9 | 1.61 | 0.23-12.46 | .058 |

| Total Stat3, % positive | 139 | 84.3 | 12.6-99.63 | 9 | 64.39 | 46.51-78.65 | .002 |

| G-CSF receptor, % positive | 139 | 58.38 | 5.8-96.18 | 9 | 50.77 | 45.62-57.34 | .208 |

| gp130, IL-6 receptor; % positive | 139 | 26.56 | 1.72-99.9 | 9 | 43.58 | 9.5-61.47 | .432 |

| SOCS3, relative densitometry | 98 | 0.096 | ND 1.79 | 10 | 0.038 | ND 0.35 | .527 |

| SHP1, relative densitometry | 98 | 6.61 | ND 87.18 | 10 | 0.75 | 0.04-6.14 | .001 |

| Parameter . | AML . | NBM . | P* . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N . | Median . | Range . | N . | Median . | Range . | ||

| Constitutive pY-Stat3, % positive | 139 | 37.19 | 0.11-91.84 | 9 | 40.51 | 7.69-50.57 | .490 |

| Constitutive pS-Stat3, % positive | 136 | 3.60 | 0.12-78.17 | 9 | 1.42 | 0.53-4.42 | .01 |

| Constitutive pY-Stat5, % positive | 123 | 16.78 | 0.5-86.54 | 7 | 11.94 | 3.79-24.22 | .21 |

| Constitutive pY-Src, % positive | 139 | 4.15 | 0.11-40.6 | 9 | 1.61 | 0.23-12.46 | .058 |

| Total Stat3, % positive | 139 | 84.3 | 12.6-99.63 | 9 | 64.39 | 46.51-78.65 | .002 |

| G-CSF receptor, % positive | 139 | 58.38 | 5.8-96.18 | 9 | 50.77 | 45.62-57.34 | .208 |

| gp130, IL-6 receptor; % positive | 139 | 26.56 | 1.72-99.9 | 9 | 43.58 | 9.5-61.47 | .432 |

| SOCS3, relative densitometry | 98 | 0.096 | ND 1.79 | 10 | 0.038 | ND 0.35 | .527 |

| SHP1, relative densitometry | 98 | 6.61 | ND 87.18 | 10 | 0.75 | 0.04-6.14 | .001 |

AML indicates acute myeloid leukemia; NBM, normal bone marrow; and ND, not detected.

Mann-Whitney U test. P values < .05 are shown in bold.

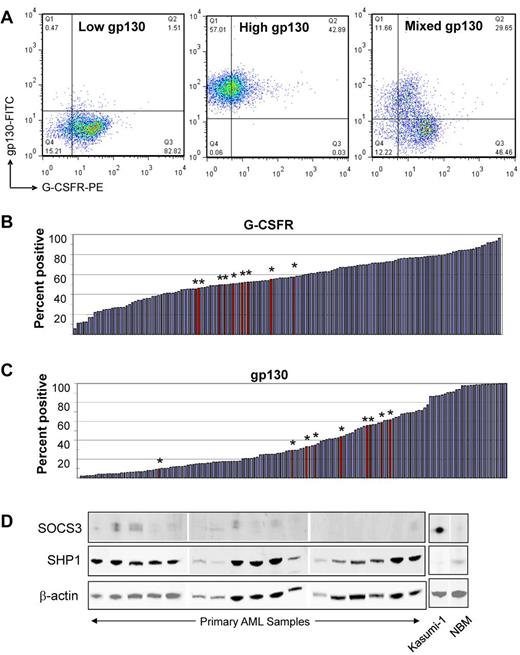

G-CSFR expression tended to be homogeneous in any given sample. In contrast, gp130 expression was either uniformly low, uniformly high, or 2 distinct subpopulations with low and high expression were noted, as shown in Figure 2A. Normal bone marrow cells had homogeneous G-CSFR expression, and all showed 2 distinct subpopulations of high and low gp130 expression. There was no difference between receptor expression values for AML and NBM samples (Table 2, Figure 2B-C).

Ligand receptor and negative regulator expression in AML and NBM samples. (A) Representative dot plots illustrate 3 patterns of gp130 expression: (left) uniformly low, (center) uniformly high, or (right) distinct high and low gp130 subpopulations. (B) Waterfall plot demonstrates the range of expression of G-CSFR. (C) Waterfall plot demonstrates the range of expression of gp130. The red bars with asterisks indicate the values for 9 normal bone marrow samples that were analyzed similarly. Bar values represent the percentage of events in the positive region. (D) Representative immunoblots illustrate SOCS3 and SHP1 expression levels in AML samples, NBM, and the internal control AML cell line Kasumi-1.

Ligand receptor and negative regulator expression in AML and NBM samples. (A) Representative dot plots illustrate 3 patterns of gp130 expression: (left) uniformly low, (center) uniformly high, or (right) distinct high and low gp130 subpopulations. (B) Waterfall plot demonstrates the range of expression of G-CSFR. (C) Waterfall plot demonstrates the range of expression of gp130. The red bars with asterisks indicate the values for 9 normal bone marrow samples that were analyzed similarly. Bar values represent the percentage of events in the positive region. (D) Representative immunoblots illustrate SOCS3 and SHP1 expression levels in AML samples, NBM, and the internal control AML cell line Kasumi-1.

For the 98 samples with sufficient remaining material, we performed Western blotting to determine the levels of 2 important negative regulators of Stat3/5 signaling in hematopoietic cells—the Jak inhibitor SOCS3 and the tyrosine phosphatase SHP1. We found that SOCS3 expression was quite low in most AML and NBM samples (Figure 2D). In contrast, SHP1 was significantly overexpressed in AML compared with NBM (P = .001). Waterfall plots demonstrating the range of densitometry values for these parameters, for AML and NBM samples, are shown in supplemental Figure 3A and B.

Inducible pStats

To test the potential for activation of the Stat3 and Stat5 pathways by exogenous stimuli, we treated AML cells with 2 factors that regulate normal myelopoiesis and signal through Stat3: G-CSF and IL-6. To determine the sensitivity of the pathways to each ligand, we tested 3 dose levels: 1, 10, and 100 ng/mL G-CSF, and 0.5 + 1, 5 + 10, and 50 + 100 ng/mL IL-6 + sIL-6R, respectively. We calculated the fold change in the mean fluorescence intensity (ΔMFI) between the unstimulated and stimulated conditions, and defined a response as a ΔMFI of at least 2 (log2(ΔMFI) ≥ 1).

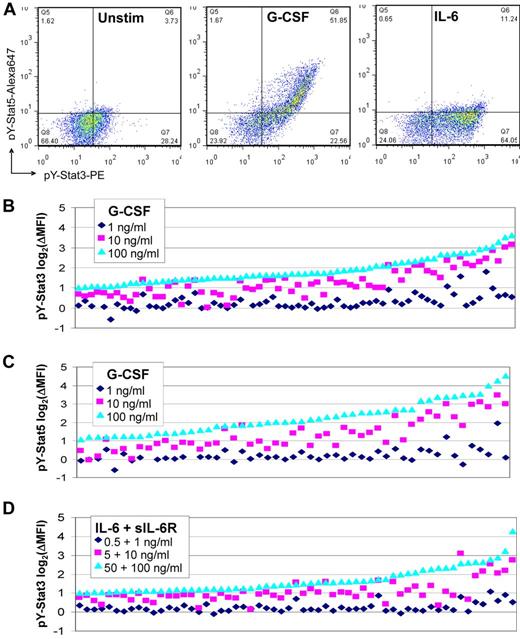

Seventy of 132 (53%) primary samples responded to G-CSF with increased pY-Stat3, and 52 of 116 (45%) responded with increased pY-Stat5 (Figure 3A). Forty-seven percent and 55% of samples failed to respond with increased pY-Stat3 or pY-Stat5, respectively, even at the highest dose of G-CSF (Table 3). Failure to respond was not associated with the age of the sample, the percent viability (75%-100%), or the percentage of blasts (before mononuclear cell enrichment). Only 3 or fewer samples had a log2(ΔMFI) ≥ 1 in response to the lowest dose of ligand (Figure 3B-C). The pY-Stat3 log2(ΔMFI) ranged from 0 (no change) to 3.62, and the maximum log2(ΔMFI) for pY-Stat5 was 4.54. Stat3 serine phosphorylation was less frequent and less robust; the maximum log2(ΔMFI) for pS-Stat3 was 2.2. Compared with G-CSF stimulation, activation of pY-Stat3 by IL-6 was generally similar (Figure 3A,D, Table 3). Response log2(ΔMFI)s ranged from 0-4.23, though most were less than 2. The majority of samples did not activate pS-Stat3 or pY-Stat5 downstream of IL-6, as expected.

FACS analysis of Stat3 and Stat5 activity in ligand-stimulated primary AML cells. (A) Representative dot plots for a sample that responded to G-CSF (10 ng/mL; center) with increased pY-Stat3 and pY-Stat5, and to IL-6 + sIL-6R (5 + 10 ng/mL; right) with pY-Stat3 only. The unstimulated condition is shown for comparison (left). Waterfall plots illustrate the (B) pY-Stat3 responses to G-CSF, (C) pY-Stat5 responses to G-CSF, and (D) pY-Stat3 responses to IL-6 + sIL-6R, at the 3 doses tested. Data are expressed as the log2(ΔMFI) of the stimulated condition over the unstimulated condition. Samples are arranged in ascending order by the log2(ΔMFI) for dose level 3, and only those samples with a log2(ΔMFI) ≥ 1 for at least 1 dose level are shown.

FACS analysis of Stat3 and Stat5 activity in ligand-stimulated primary AML cells. (A) Representative dot plots for a sample that responded to G-CSF (10 ng/mL; center) with increased pY-Stat3 and pY-Stat5, and to IL-6 + sIL-6R (5 + 10 ng/mL; right) with pY-Stat3 only. The unstimulated condition is shown for comparison (left). Waterfall plots illustrate the (B) pY-Stat3 responses to G-CSF, (C) pY-Stat5 responses to G-CSF, and (D) pY-Stat3 responses to IL-6 + sIL-6R, at the 3 doses tested. Data are expressed as the log2(ΔMFI) of the stimulated condition over the unstimulated condition. Samples are arranged in ascending order by the log2(ΔMFI) for dose level 3, and only those samples with a log2(ΔMFI) ≥ 1 for at least 1 dose level are shown.

Ligand response categorization for AML samples

| Ligand parameter (N) . | Response* at dose 1/2 (%) . | Response† at dose 3 (%) . | No response (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| G-CSF | |||

| pY-Stat3 (132) | 44 (33) | 26 (20) | 62 (47) |

| pS-Stat3 (128) | 7 (5.5) | 18 (14) | 103 (80.5) |

| pY-Stat5 (116) | 28 (24) | 24 (21) | 64 (55) |

| IL-6 | |||

| pY-Stat3 (138) | 23 (16.5) | 37 (27) | 78 (56.5) |

| pS-Stat3 (135) | 2 (1.5) | 6 (4.5) | 127 (94) |

| pY-Stat5 (122) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 120 (98) |

| Ligand parameter (N) . | Response* at dose 1/2 (%) . | Response† at dose 3 (%) . | No response (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| G-CSF | |||

| pY-Stat3 (132) | 44 (33) | 26 (20) | 62 (47) |

| pS-Stat3 (128) | 7 (5.5) | 18 (14) | 103 (80.5) |

| pY-Stat5 (116) | 28 (24) | 24 (21) | 64 (55) |

| IL-6 | |||

| pY-Stat3 (138) | 23 (16.5) | 37 (27) | 78 (56.5) |

| pS-Stat3 (135) | 2 (1.5) | 6 (4.5) | 127 (94) |

| pY-Stat5 (122) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 120 (98) |

Samples in this category demonstrated a log2(ΔMFI) ≥ 2 at the intermediate and high ligand doses, and in a few cases even at the lowest ligand dose.

Samples in this category demonstrated a log2 (ΔMFI) ≥ 2 at the highest ligand doses only.

We also determined ligand responses of 8 NBM samples to G-CSF and IL-6. In contrast to the variable responses in the AML samples, the responses in the normal samples were quite consistent. In 7 of 8 cases, we noted a subpopulation, comprising 6% to 40% of the nonlymphocyte mononuclear cells, that showed several-fold increases in all 3 pStats in response to G-CSF, and in pY- and pS-Stat3 in response to IL-6, at the intermediate and high doses (data not shown). This robust response within a subset of the myeloid precursor population is consistent with other recent studies.20,21

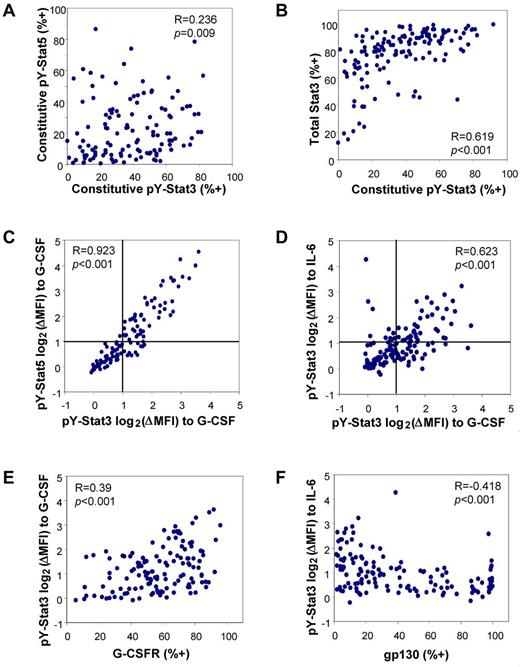

Relationships between signaling parameters

To identify patterns of relationship between the various parameters, we performed Spearman correlations. Figure 4A shows a slight, though significant, correlation between constitutive pY-Stat3 and pY-Stat5 (R = 0.236; P = .009). Bivariate analyses of pSrc vs pY-Stat3 and pY-Stat5 showed a positive relationship for pY-Stat5 (R = 0.394, P < .001; supplemental Figure 4A), as has been reported previously.22 The bivariate plot of pY-Stat3 vs total Stat3 revealed another positive correlation (R = 0.61; P < .001; Figure 4B). A feed-forward relationship is expected because the STAT3 gene is transcriptionally induced by Stat3 activation. Neither SOCS3 nor SHP1 expression were correlated with constitutive Stat phosphorylation (not shown).

Bivariate correlations reveal relationships between Stat pathway parameters. (A) In unstimulated cells, pY-Stat3 and pY-Stat5 levels were weakly related. (B) Basal pY-Stat3 was positively correlated with the total amount of Stat3 available. (C) The levels of pY-Stat3 and pY-Stat5 were tightly correlated in G-CSF–stimulated cells. (D) The levels of G-CSF–induced pY-Stat3 and IL-6–induced pY-Stat3 were positively correlated, as well. Lines at log2(ΔMFI) of 1 indicate the threshold for considering a sample “responsive” at these doses. (E) The magnitude of the pY-Stat3 response to G-CSF was significantly correlated with the level of G-CSFR expression. (F) The magnitude of the pY-Stat3 response to IL-6 + sIL-6R was inversely correlated with gp130 expression. G-CSF stimulation: 100 ng/mL; IL-6 + sIL-6R stimulation: 50 + 100 ng/mL. R = Spearman correlation coefficient.

Bivariate correlations reveal relationships between Stat pathway parameters. (A) In unstimulated cells, pY-Stat3 and pY-Stat5 levels were weakly related. (B) Basal pY-Stat3 was positively correlated with the total amount of Stat3 available. (C) The levels of pY-Stat3 and pY-Stat5 were tightly correlated in G-CSF–stimulated cells. (D) The levels of G-CSF–induced pY-Stat3 and IL-6–induced pY-Stat3 were positively correlated, as well. Lines at log2(ΔMFI) of 1 indicate the threshold for considering a sample “responsive” at these doses. (E) The magnitude of the pY-Stat3 response to G-CSF was significantly correlated with the level of G-CSFR expression. (F) The magnitude of the pY-Stat3 response to IL-6 + sIL-6R was inversely correlated with gp130 expression. G-CSF stimulation: 100 ng/mL; IL-6 + sIL-6R stimulation: 50 + 100 ng/mL. R = Spearman correlation coefficient.

To determine whether the pathways from the G-CSF receptor to the 3 pStat endpoints were overlapping or independent, we performed bivariate analyses for the log2(ΔMFI) values for the highest dose of G-CSF. Indeed, we found a very robust correlation between pY-Stat3 and pS-Stat3 (R = 0.919; P < .001; data not shown) and between pY-Stat3 and pY-Stat5 (R = 0.923; P < .001), as shown in Figure 4C. Thus, while constitutive activation of pY-Stat3 may occur in the absence of constitutive pY-Stat5, and vice versa, discordance in G-CSF–induced pY-Stat3 and pY-Stat5 is rare, indicating that the pathways to each Stat downstream of the G-CSF receptor greatly overlap. Similar analysis demonstrated a positive relationship between pY-Stat3 log2(ΔMFI)s in response to G-CSF and IL-6 (Figure 4D; R = 0.623, P < .001), suggesting that, in responsive samples, the signaling pathways from the G-CSFR and gp130 to pY-Stat3 are likely to partially overlap, as expected.

We also asked whether there was a relationship between the level of basal pY-Stat3 and the inducibility of pY-Stat3, reasoning that samples with high constitutive activation may be less able to further activate Stat3 in response to ligand stimulation. We did not see a significant correlation for either ligand, suggesting that the constitutive and ligand-induced pathways leading to pY-Stat3 are distinct. In the case of pY-Stat5, there was a weak negative correlation between constitutive pY-Stat5 and G-CSF–induced log2(ΔMFI) (R = −0.295, P = .001; supplemental Figure 4B), supporting the notion that high basal pY-Stat5 may limit the ability of cells to further activate Stat5 in response to ligand stimulation.

The level of G-CSFR expression positively correlated with the magnitude of the G-CSF–induced response for pY-Stat3 (R = 0.39, P < .001; Figure 4E). Indeed, the samples with the most robust inducible G-CSF responses had high levels of G-CSFR. Surprisingly, no such relationship was apparent with gp130 levels and IL-6–induced responses. In this case, the correlation was negative, such that the most responsive samples tended to have low gp130 expression (Figure 4F; R = −0.418, P < .001). The explanation for an inverse relationship is not clear, but it is possible that highly responsive samples have low receptor expression because of increased receptor internalization, and/or samples with high receptor expression are not responsive because receptors are mislocalized or in some other way nonfunctional. G-CSFR and gp130 levels were completely independent of one another (not shown).

For 55 samples, we also measured surface CD33 expression, as a marker of differentiation. Previous work has demonstrated that the CD33+ and CD33− fractions of CD34+ AML progenitors have distinct phenotypes and relationships with prognosis.23 Overall, we found no correlation between CD33 expression and constitutive pY-Stat3 or pS-Stat3, but a positive correlation between CD33 expression and constitutive pY-Stat5 (R = 0.430, P < .001) and pY418-Src (R = 0.479, P < .001), as shown in supplemental Figure 4C and D. In other words, more mature samples tended to have higher resting Stat5 and Src activation. CD33 levels were not significantly correlated with G-CSFR expression, but were strongly correlated with gp130 expression (R = 0.537, P < .001, supplemental Figure 4E). In terms of ligand responses, CD33 expression was negatively correlated with the magnitude of the pY-Stat3 response to IL-6 (R = −0.310, P = .021, supplemental Figure 4F) and the pY-Stat5 response to G-CSF (R = −0.298, P = .027, not shown) but not the pY-Stat3 response to G-CSF (R = −0.107, P = .437, not shown). Taken together, these analyses suggest that the relatively more mature samples have a distinct signaling phenotype, characterized by increased basal Src activation, increased constitutive pY-Stat5, and increased gp130 expression with paradoxically decreased responsiveness to IL-6.

Correlations of signaling parameters with clinical parameters

For the basal pStat parameters, total Stat3, pY418-Src, and receptor levels, we performed cut-point analyses using all values between the 10th and 90th percentiles, to determine whether a threshold separating favorable outcome and poor outcome could be identified. No such threshold was found for pY-Stat3 (supplemental Figure 5A), total Stat3 (supplemental Figure 5B), or any of the other basal parameters. Cut-point analyses also were applied to the magnitude of the ligand-induced pStat responses (ie maximum log2(ΔMFI)), and similarly, no prognostic response magnitude was identified. Thus, in this study, neither constitutive nor induced pStat levels correlated with survival.

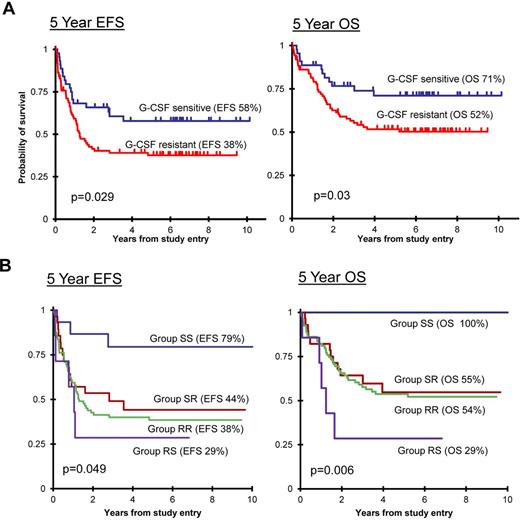

In contrast, evaluation of G-CSF–induced pY-Stat3 activation showed a significant association of ligand sensitivity with clinical outcome (Figure 5A). Patients whose blasts had a pY-Stat3 response (ie, log2(ΔMFI) ≥ 1) to G-CSF at dose level 2 (10 ng/mL; n = 44, 33%) had a 5-year EFS of 57.8% (95% CI, 41.5%-71.1%) and 5-year OS of 71.1% (95% CI, 54.5%-82.5%), whereas patients whose samples did not respond at this dose (n = 88, 67%) had a 5-year EFS of 37.6% (95% CI, 27.4%-47.8%) and 5-year OS of 51.7% (95% CI, 40.6%-61.7%), with P = .029 and P = .03, respectively. Patients with a response to G-CSF at dose level 3, but not dose level 2, had outcomes equal to patients with no response to G-CSF, confirming dose level 2 as the clinically relevant threshold (supplemental Figure 6). A similar trend was observed for pY-Stat3 sensitivity to IL-6 at dose level 2 (not shown, P = .114 for EFS and P = .058 for OS). Despite the strong correlation between the magnitudes of G-CSF–induced pY-Stat3 and pY-Stat5, we did not find a significant relationship between the pY-Stat5 sensitivity to G-CSF and outcome. Of the 44 samples with a pY-Stat3 response to G-CSF at dose level 2, 12 did not meet the “response” threshold at this dose for pY-Stat5, and 5 others were not analyzed for pY-Stat5.

Ligand sensitivity was associated with outcome. (A) Kaplan-Meier survival curves demonstrate that patients whose blasts were sensitive to G-CSF (log2(ΔMFI) ≥ 1 at 1 or 10 ng/mL dose) had a superior EFS (left) and OS (right) compared with patients whose blasts did not respond at the lower dose levels (G-CSF resistant). (B) The sensitivity of blasts to both G-CSF and IL-6 also significantly predicted EFS (left) and OS (right). Group SS indicates G-CSF sensitive and IL-6 sensitive (log2(ΔMFI) ≥ 1 at dose level 2); group SR indicates G-CSF sensitive and IL-6 resistant; group RR indicates G-CSF resistant and IL-6 resistant; and group RS indicates G-CSF resistant and IL-6 sensitive.

Ligand sensitivity was associated with outcome. (A) Kaplan-Meier survival curves demonstrate that patients whose blasts were sensitive to G-CSF (log2(ΔMFI) ≥ 1 at 1 or 10 ng/mL dose) had a superior EFS (left) and OS (right) compared with patients whose blasts did not respond at the lower dose levels (G-CSF resistant). (B) The sensitivity of blasts to both G-CSF and IL-6 also significantly predicted EFS (left) and OS (right). Group SS indicates G-CSF sensitive and IL-6 sensitive (log2(ΔMFI) ≥ 1 at dose level 2); group SR indicates G-CSF sensitive and IL-6 resistant; group RR indicates G-CSF resistant and IL-6 resistant; and group RS indicates G-CSF resistant and IL-6 sensitive.

Next, we asked whether combining G-CSF and IL-6 sensitivities correlated with survival. To do so, we classified samples into 4 groups. Group SS (n = 15, 11%) samples were sensitive to both G-CSF and IL-6, meaning they achieved ΔMFI ≥ 2 (log2(ΔMFI)≥ 1) for pY-Stat3 at dose level 2 for both ligands. Group SR (n = 28, 21%) samples were sensitive to G-CSF but resistant to IL-6, and group RS (n = 7, 5%) included samples that were resistant to G-CSF but sensitive to IL-6. The majority of samples were resistant to both ligands and thus were classified as group RR (n = 81, 61%). Figure 5B shows the EFS and OS for each group. Group SS patients had a significantly superior outcome, with 79.4% (95% CI, 48.8%-92.9%) EFS and 100% OS (P = .049 and P = .006, respectively). The survival rates of patients in groups SR and RR, in the range of 40% EFS and 50% OS, were similar to the survival rates for the CCG 2961 study as a whole.18 Morphologically, group SS included 1 M0, 4 M1, 7 M2, 1 M4, 1 M5, and 1 M7 sample. There were no differences in age or race between the response groups. Interestingly, there was a trend toward a higher WBC in group RS (median, 168.5 × 103/μL) compared with the other response groups (medians, 23.9-34.9 × 103/μL; P = .082). This observation suggests that the unusual response pattern of IL-6 sensitivity with G-CSF resistance identifies a small group of patients with a distinct, aggressive biology.

In univariate analysis (Table 4), the SS response was associated with a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.24 for EFS (P = .016). Other significant factors in univariate analyses included FLT3/ITD and WBC ≥ 100 000/μL. In multivariate analyses of EFS, group SS retained independent significance with WBC (P = .026) and with FLT3/ITD (P = .036). Group SS also retained significance in multivariate analysis with treatment arm (FLU-IDA vs IDA-DCTR; P = .041). These results support the conclusion that the SS response pattern was a true favorable prognostic factor in this study.

Univariate analyses of novel and known prognostic factors

| Prognostic factor . | N . | Event-free survival . | Overall survival . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR . | 95% CI . | P . | HR . | 95% CI . | P . | ||

| Response group | |||||||

| RR | 81 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| SS | 15 | 0.24 | 0.07-0.77 | .016 | No convergence† | ||

| SR | 28 | 0.83 | 0.47-1.48 | .530 | 0.89 | 0.48-1.75 | .785 |

| RS | 7 | 1.37 | 0.55-3.45 | .501 | 2.16 | 0.85-5.52 | .107 |

| Cytogenetics risk | |||||||

| Not low* | 62 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Low* | 30 | 0.64 | 0.36-1.17 | .148 | 0.69 | 0.34-1.36 | .281 |

| FLT3/ITD | |||||||

| Negative | 113 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Positive | 15 | 2.27 | 1.21-4.23 | .010 | 3.11 | 1.63-5.92 | < .001 |

| CEBPα | |||||||

| Wild type | 124 | No convergence‡ | No convergence‡ | ||||

| Mutated | 4 | ||||||

| NPM1 | |||||||

| Wild type | 93 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Mutated | 9 | 0.71 | 0.26-1.95 | .502 | 0.67 | 0.21-2.18 | .510 |

| WBC | |||||||

| < 100 000 | 110 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥ 100 000 | 29 | 1.67 | 1.00-2.80 | .049 | 1.85 | 1.05-3.27 | .034 |

| Prognostic factor . | N . | Event-free survival . | Overall survival . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR . | 95% CI . | P . | HR . | 95% CI . | P . | ||

| Response group | |||||||

| RR | 81 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| SS | 15 | 0.24 | 0.07-0.77 | .016 | No convergence† | ||

| SR | 28 | 0.83 | 0.47-1.48 | .530 | 0.89 | 0.48-1.75 | .785 |

| RS | 7 | 1.37 | 0.55-3.45 | .501 | 2.16 | 0.85-5.52 | .107 |

| Cytogenetics risk | |||||||

| Not low* | 62 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Low* | 30 | 0.64 | 0.36-1.17 | .148 | 0.69 | 0.34-1.36 | .281 |

| FLT3/ITD | |||||||

| Negative | 113 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Positive | 15 | 2.27 | 1.21-4.23 | .010 | 3.11 | 1.63-5.92 | < .001 |

| CEBPα | |||||||

| Wild type | 124 | No convergence‡ | No convergence‡ | ||||

| Mutated | 4 | ||||||

| NPM1 | |||||||

| Wild type | 93 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Mutated | 9 | 0.71 | 0.26-1.95 | .502 | 0.67 | 0.21-2.18 | .510 |

| WBC | |||||||

| < 100 000 | 110 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥ 100 000 | 29 | 1.67 | 1.00-2.80 | .049 | 1.85 | 1.05-3.27 | .034 |

HR indicates hazard ratio; and CI, confidence interval.

Low-risk cytogenetics: t(8;21) and inv(16).

SS group has 100% survival; therefore, RR, SR, RS groups are compared.

CEBPα mutated group has 100% event-free and overall survival.

Current risk stratification schemes for pediatric AML rely heavily on cytogenetic findings and the presence or absence of FLT3/ITD, CEBPα, and NPM1 mutations. Therefore, we asked whether there were any associations between the pY-Stat3 response groups and these parameters. Cytogenetic results are available for 92 of 139 (66%) of the patients in this cohort. FLT3/ITD and CEBPα mutation results are known for 92% of patients, and NPM1 mutation status is known for 73%. Table 5 shows that the G-CSF–sensitive group included a significantly higher proportion of patients with core-binding factor translocations, compared with the G-CSF–resistant group (P = .043). The distributions of FLT3/ITD, CEBPα, and NPM1 mutations were not significantly different across the pY-Stat3 response groups.

Distribution of cytogenetic and mutation categories within ligand response groups

| Conventional prognostic factor . | Percent in entire cohort* (n) . | Percent in G-CSF sensitive* (n) . | Percent in G-CSF resistant* (n) . | P sensitive vs resistant . | Percent in response group SS* (n) . | Percent in response group RS* (n) . | Percent in response group SR* (n) . | Percent in response group RR* (n) . | P all groups . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-risk cytogenetics† | 32.6 (30) | 50 (11) | 26.6 (17) | .043 | 66.7 (4) | 42.9 (3) | 40 (6) | 24.6 (14) | .114 |

| Standard-risk cytogenetics‡ | 64.1 (59) | 50 (11) | 68.8 (44) | .114 | 33.3 (2) | 57.1 (4) | 60 (9) | 70.2 (40) | .300 |

| High-risk cytogenetics§ | 3.3 (3) | 0 | 4.7 (3) | .567 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5.3 (3) | 1.000 |

| FLT3/ITD+ | 11.7 (15) | 5.1 (2) | 14.6 (12) | .222 | 0 | 14.3 (1) | 8.3 (2) | 14.7 (11) | .436 |

| FLT3/ITD− | 88.3 (113) | 94.9 (37) | 85.4 (70) | 100 (14) | 85.7 (6) | 91.7 (22) | 85.3 (64) | ||

| CEBPα mutated | 3.1 (4) | 7.7 (3) | 1.2 (1) | .098 | 0 | 0 | 12 (3) | 1.3 (1) | .119 |

| CEBPα WT | 96.9 (124) | 92.3 (36) | 98.8 (81) | 100 (13) | 100 (7) | 88 (22) | 98.7 (74) | ||

| NPM1 mutated | 8.8 (9) | 3.3 (1) | 12.1 (8) | .265 | 9.1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 13.1 (8) | .413 |

| NPM1 WT | 91.32 (93) | 96.7 (29) | 87.9 (58) | 90.9 (10) | 100 (5) | 100 (18) | 86.9 (53) |

| Conventional prognostic factor . | Percent in entire cohort* (n) . | Percent in G-CSF sensitive* (n) . | Percent in G-CSF resistant* (n) . | P sensitive vs resistant . | Percent in response group SS* (n) . | Percent in response group RS* (n) . | Percent in response group SR* (n) . | Percent in response group RR* (n) . | P all groups . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-risk cytogenetics† | 32.6 (30) | 50 (11) | 26.6 (17) | .043 | 66.7 (4) | 42.9 (3) | 40 (6) | 24.6 (14) | .114 |

| Standard-risk cytogenetics‡ | 64.1 (59) | 50 (11) | 68.8 (44) | .114 | 33.3 (2) | 57.1 (4) | 60 (9) | 70.2 (40) | .300 |

| High-risk cytogenetics§ | 3.3 (3) | 0 | 4.7 (3) | .567 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5.3 (3) | 1.000 |

| FLT3/ITD+ | 11.7 (15) | 5.1 (2) | 14.6 (12) | .222 | 0 | 14.3 (1) | 8.3 (2) | 14.7 (11) | .436 |

| FLT3/ITD− | 88.3 (113) | 94.9 (37) | 85.4 (70) | 100 (14) | 85.7 (6) | 91.7 (22) | 85.3 (64) | ||

| CEBPα mutated | 3.1 (4) | 7.7 (3) | 1.2 (1) | .098 | 0 | 0 | 12 (3) | 1.3 (1) | .119 |

| CEBPα WT | 96.9 (124) | 92.3 (36) | 98.8 (81) | 100 (13) | 100 (7) | 88 (22) | 98.7 (74) | ||

| NPM1 mutated | 8.8 (9) | 3.3 (1) | 12.1 (8) | .265 | 9.1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 13.1 (8) | .413 |

| NPM1 WT | 91.32 (93) | 96.7 (29) | 87.9 (58) | 90.9 (10) | 100 (5) | 100 (18) | 86.9 (53) |

Percent of samples with specified cytogenetics within given category, among those samples with known cytogenetics. P values < .05 are shown in bold.

Low-risk cytogenetics: t(8;21) and inv(16).

Standard-risk cytogenetics: neither low nor high risk.

High-risk cytogenetics: monosomy 7, monosomy 5, del(5q).

Discussion

Phospho-flow methodology is emerging as a powerful tool for studying signaling activity in clinical samples. We measured Stat3/5 activation in primary AML cells before and after stimulation with G-CSF or IL-6. We demonstrated a wide range of constitutive activation of Stat3 and Stat5, although neither parameter was associated with outcome. Previous studies of constitutive Stat3 in AML, in which pY-Stat3 was measured in cell lysate by immunoblotting or EMSA,4,7-10 suggested that increased basal pY-Stat3 correlated with poor survival. Whereas these studies defined the percentage of samples with or without constitutive pY-Stat3, our phospho-flow study revealed a continuum of pY-Stat3 levels. As reported by Gibbs et al,20 we also noted basal Stat activation in normal myeloid precursors. The differences between our results and previous studies are likely because of the fact that phospho-flow is a much more sensitive method that uses intact cells rather than lysate. Stat3 is rapidly degraded by proteases in myeloid cell granules on lysis, and measures beyond routine protease inhibitors can be required.24 Thus, by phospho-flow, we did not find a significant difference in constitutive pY-Stat3 or pY-Stat5 between AML and NBM cells, nor were these parameters associated with survival.

Flow cytometry also allows multiple parameters to be measured in each patient sample. Bivariate correlations identified relationships between parameters that provided new insights into Stat3/5 signaling in AML. For example, we found only a weak relationship between constitutive pY-Stat3 and pY-Stat5, but an extremely tight correlation between these parameters after G-CSF stimulation. These results suggest that the mechanisms leading to constitutive activation are likely to be relatively random, as opposed to the highly organized pathway from the G-CSF receptor to Stat3 and Stat5. Moreover, high basal pY-Stat3 did not prevent further increase with ligand, but when basal pY-Stat5 was already high, a ligand-induced increase was unlikely.

Correlations between surface markers and pStats also yielded interesting results. While the relationship between G-CSFR expression and G-CSF–induced pY-Stat3 was a positive one, we did identify several samples with high G-CSFR expression that failed to induce pY-Stat3. Even more striking, the relationship between gp130 expression and IL-6–induced pY-Stat3 was inverse. The disconnect between the receptor at the surface and the pY-Stat3 target could occur at several levels. For example, mislocalization of receptors, for example, outside lipid raft domains, could explain the high level of nonfunctioning receptors we see in some cases. Alternatively, an element in the pathway between the receptor and Stat3, such as a Jak or Src kinase, could be dysfunctional. Bivariate correlations also allowed us to define a signaling pattern that was associated with CD33 expression, and possibly therefore, with the degree of myeloid maturation. That is, samples with higher CD33 expression had higher constitutive pY-Stat5 levels, higher gp130 expression, and lower IL-6 responsiveness.

Our study is the first to identify an association between the sensitivity of a signaling pathway and patient survival in AML. Recent phospho-flow studies using adult AML samples have found an association between increased basal and induced pY-Stat3 and decreased likelihood of achieving remission.13,15 We did not find an association between the magnitude of basal or induced pStats and clinical outcome. Our data instead revealed a significant association between the sensitivity of the ligand response and outcome, with increased sensitivity being significantly associated with better survival. These observed differences may be due in part to the different study populations. It is well recognized that pediatric AML is biologically different from its adult counterpart with distinct cytogenetic and molecular characteristics. Our data further suggest there may be fundamental biologic differences.

While the pY-Stat3 response to G-CSF alone was prognostic, even more definitive stratification was obtained when both ligands were taken into account. The response pattern of group SS, associated with a significantly better outcome, was similar to that of normal immature myeloid cells.20,21 We speculate that leukemia cells that are more sensitive to normal stimuli may also be more sensitive to chemotherapy. Conversely, leukemia cells in which the responses to normal stimuli are blunted may be more chemoresistant. Because endogenous ligands like G-CSF and IL-6 stimulate proliferation, responsive cells would be more vulnerable to chemotherapy agents that target cycling cells, such as cytarabine. The connection also could relate to the stage of differentiation,20 and in this regard it is notable that 11 of the 15 group SS samples had M1 or M2 morphology. Further studies are under way to specifically investigate the link between ligand sensitivity and chemosensitivity.

It is important to note that patients with a favorable response pattern were more likely to also have low-risk cytogenetics, and the limited availability of cytogenetic data in the CCG 2961 study precluded meaningful multivariate analysis. Interestingly, however, low-risk cytogenetics did not emerge as a significant favorable predictor by univariate analysis in this cohort, while the group SS response pattern was significant. It remains to be determined whether ligand responsiveness will become a useful criterion for risk assessment, but our data do suggest that it may be of value, at least in cases that lack other strong predictors such as FLT3/ITD or CEBPα mutations.

The RS pattern suggests that signaling pathways in general may be intact, but that these samples may have a specific defect within or proximal to the G-CSFR. In support of this idea, Ehlers et al25 reported that the expression level of the truncated, differentiation-defective G-CSF receptor isoform IV, known to be overexpressed in some AML patients,26 was associated with worse outcome in patients who received G-CSF. Our results also have implications for the use of G-CSF “priming” in AML. The theory is that G-CSF pretreatment sensitizes blasts to chemotherapy. Our finding that nearly half of the samples failed to respond to G-CSF may be one explanation for the variable results with this approach, and evaluation of G-CSF–induced pY-Stat3 may be one way to identify patients who are likely to benefit from a priming strategy. Indeed, erythropoietin-induced Stat5 phosphorylation correlates with clinical erythropoietin response in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes, and it has been suggested that this assay could be used as a screening test to predict whether a patient is likely to benefit from treatment.27

Ligand-response information also could be used to identify patients who are, and are not, likely to benefit from new agents targeting signaling pathways, such as Stat3 inhibitors or Akt inhibitors. Of course, before phospho-flow data can be used to direct clinical decisions, studies like ours must be extensively validated in multiple cohorts, and clinical assays must be standardized.28 Further studies are planned to confirm these findings in a second cohort, and to determine whether the sensitivity of other non-STAT signaling endpoints might have similar clinical association. Overall, our study has yielded critical insights into AML biology, and has demonstrated the potential importance of taking into account dynamic functional patterns for determining risk and individualizing existing and emerging therapies.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health (NHLBI K08 HL085018; M.S.R.), a Research Fellowship Award from the National Childhood Cancer Foundation/CureSearch (M.S.R.), and an Individual Investigator Award from the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (RP100421; D.J.T. and M.S.R.).

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: M.S.R. designed the study, performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript; M.J.R. performed the experiments and analyzed the data; R.B.G. and T.A.A. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript; B.J.L. chaired the CCG 2961 study and provided the samples; D.J.T. designed the study and wrote the manuscript; and S.M. provided the samples, designed the study, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Michele S. Redell, MD, PhD, Texas Children's Cancer and Hematology Centers, 1102 Bates, Suite 750, Houston, TX 77030; e-mail: mlredell@txch.org.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal