Key Points

Ik−/− mice overproduce basophils and their precursors in the absence of extrinsic inflammatory signals.

Ikaros restrains development of basophils by regulating histone modifications at lineage-specifying genes, including Cebpa and Hes1.

Abstract

The Ikaros gene (Ikzf1) encodes a family of zinc-finger transcription factors implicated in hematopoietic cell differentiation. Here we show that Ikaros suppresses the development of basophils, which are proinflammatory cells of the myeloid lineage. In the absence of extrinsic basophil-inducing signals, Ikaros−/− (Ik−/−) mice exhibit increases in basophil numbers in blood and bone marrow and in their direct precursors in bone marrow and the spleen, as well as decreased numbers of intestinal mast cells. In vitro culture of Ik−/− bone marrow under mast cell differentiation conditions also results in predominance of basophils. Basophil expansion is associated with an increase in basophil progenitors, increased expression of Cebpa and decreased expression of mast cell-specifying genes Hes1 and microphthalmia-associated transcription factor (Mitf). Ikaros directly associates with regulatory sites within Cebpa and Hes1 and regulates the acquisition of permissive H3K4 tri-methylation marks at the Cebpa locus and reduces H3K4 tri-methylation at the Hes1 promoter. Ikaros blockade in cultured cells or transfer of Ik−/− bone marrow into irradiated Ik+/+ recipients also results in increased basophils confirming a cell-intrinsic effect of Ikaros on basophil development. We conclude that Ikaros is a suppressor of basophil differentiation under steady-state conditions and that it acts by regulating permissive chromatin modifications of Cebpa.

Introduction

Mast cells and basophils are related proinflammatory myeloid cells.1-4 Both express the αβγ2 form of the high-affinity immunoglobulin E (IgE) receptor FcεRI and, with crosslinking, release a similar spectrum of mediators that contribute to allergic responses and antiparasite immunity. Although basophils were once considered circulating equivalents of tissue mast cells, it is now appreciated that these cell types exert unique roles in health and disease.3,5-7

In contrast to long-lived tissue-resident mast cells, basophils have a short lifespan, expanding in response to specialized inflammatory cues including interleukin-3 (IL-3) and thymic stromal lymphopoietin.8,9 As with mast cells, basophils participate in IgE-mediated allergic inflammation, but exert more profound effects on chronic- and late-phase inflammation10 and contribute to IgG-dependent systemic anaphylaxis.11 Basophils produce high levels of IL-4 and may present antigen.12,13

Mast cells and basophils can be derived from the multipotent, lineage-restricted granulocyte-monocyte progenitor (GMP).14,15 A bipotent basophil mast cell precursor (BMCP), likely derived from the GMP, has also been identified in the spleen,1 demonstrating that the pathways regulating the differentiation of these cells are interconnected. However, a mast cell-specific developmental pathway arising from earlier myeloid precursors has also been identified.16,17

Microphthalmia-associated transcription factor (MITF), GATA-1, 2 and 3, PU.1, Hes1, and STAT5a/b are among the transcription factors expressed early in developing mast cells, acting in concert to promote differentiation.18-20 Basophils also express STAT5a/b, GATA-1, and GATA-2, but CCAAT/enhancer binding protein (C/EBP-α) is uniquely important in the development of this lineage. Although widely expressed in the myeloid lineage, the timing of C/EBP-α expression is critical to its function. Notably, enforced overexpression of C/EBP-α in BMCPs results in exclusive differentiation into basophils, whereas conditional deletion of C/EBP-α in these same cells promotes mast cell differentiation,1 suggesting that C/EBP-α is an essential “switch factor” for basophil lineage choice.

The fate of a multipotent precursor cell results in part from chromatin alterations allowing activation of select subsets of lineage-specific genes and silencing of others. Ikaros, a DNA-binding factor, is well-suited to mediate such alternative fate decisions.21 Ikaros comprises a family of DNA-binding and nonbinding isoforms generated by alternative splicing (as reviewed in Georgopoulos22 and in John and Ward23 ). Ikaros can associate with activating or suppressive chromatin-remodeling complexes, providing the potential to exert both positive and negative effects on transcription. Ikaros−/− (Ik−/−) mice, which contain a targeted disruption of Ikzf1, lack B cells, natural killer cells, and fetal T cells, although T cells populate the periphery after birth.24-27 Ikaros also affects dendritic cells, and erythroid and neutrophil development.28-30

We previously demonstrated that Ikaros is expressed in bone marrow-derived mast cells, where it regulates the expression of a subset of mast cell genes, including Il4.31 Here, we initially examined the effect of Ikaros on mast cell development. Mast cells and mast cell precursor (MCp) are reduced in the gut, but Ik−/− mice have normal numbers of mast cells in other tissues, indicating that Ikaros is not essential for mast cell development. Surprisingly, basophil numbers are strikingly increased, as are their direct progenitors (basophil precursor [BaP] and BMCP) in bone marrow and the spleen, respectively.

This unsolicited basophil expansion is associated with an increase in Cebpa expression and a decreased expression of the mast cell-specifying genes Hes1 and Mitf, as well as Stat5, Gata1, and Gata2, both in vivo and in vitro. Although the absence of Ikaros prompts basophil expansion, wild-type basophils and their precursors do not downregulate Ikzf1 messenger RNA. Ikaros associates with regulatory sites within the Cebpa and Hes1 loci, and its absence results in the acquisition of permissive marks at the Cebpa locus and reduced marks at the Hes1 promoter. Thus, Ikaros is a suppressor of basophil differentiation under steady-state conditions, acting in part through epigenetic control of Cebpa and Hes1.

Methods

Mice

The (C57BL/6:SV129) Ik−/− mice27 and Ik+/+ littermates were bred and housed in the specific pathogen-free animal care facilities of Northwestern University. Genotyping was performed by tandem polymerase chain reaction to detect the presence of Ik− neo cassette or the intact Ik+ exon 7 using Terra reagent (Clontech, Mountain View, CA). The (WB × C57BL/6) F1-KitW/Wv mice and Kit+/+ littermates were purchased from Jackson Laboratories. These studies were approved by the Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use committee.

Antibodies and primers

Specific antibodies and primers used in these experiments are listed in supplemental Data (available on the Blood Web site).

Cell culture

Bone marrow was harvested from the femurs of 3- to 5-week-old mice and cultured with 5 ng/mL recombinant murine IL-3 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) alone or with 12.5 ng/mL recombinant murine stem cell factor (SCF) (Invitrogen) in complete RPMI 1640/15% fetal calf serum (Corning Cellgro, Manassas, VA).

Cytometry and cell sorting

Single cell suspensions were prepared from spleens and livers by mechanical dispersion through 70 μm filters (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), and the bone marrow was needle-aspirated. Erythrocytes were lysed with ammonium-chloride-potassium buffer. Cells were blocked with anti-CD16/32 for 10 minutes; in some experiments, fluorescent anti-CD16/32 was substituted. Cells were incubated for 30 to 90 minutes with antibody, washed twice, and analyzed or sorted immediately. For precursor analysis experiments, viability was assessed with SYTOX Blue (Invitrogen). Flow cytometry was performed using a FacsCanto II or LSR II (BD Biosciences). Sorting was performed by core facility staff on a FacsAria III (BD Biosciences); cells were sorted directly into RNA lysis buffer. FlowJo 9 (TreeStar, Ashland, OR) was used for analysis. “Lineage” is a mixture of anti-CD3, CD4, CD8, CD19, CD45R, Ter119, and Gr-1 antibodies. Absolute cell numbers were determined with TruCount tubes (BD Biosciences) or direct counting.

Mast cell degranulation assay

Degranulation was assessed by β-hexosaminidase release.32 Briefly, bone marrow-derived mast cells were sensitized with 0.5 μg/mL anti-dinitrophenol (DNP) IgE (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) for 3 hours in RPMI 1640 with IL-3 and SCF. Cells were stimulated with DNP-human serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 minutes in Tyrode’s buffer before supernatant collection and lysis of the cell pellet with 0.5% Triton X-100. β-Hexosamindase activity was measured in the supernatant and in the lysed pellet by incubation with poly-N-acetylglucosamine (Sigma-Aldrich) at 405 nm absorbance.

Analysis of mast cell phenotype

Bone marrow mast cells were sensitized as previously described in this article and cross-linked by the addition of DNP-human serum albumin. Surface markers were assessed 10 to 12 hours later by flow cytometry. Supernatant cytokine release was measured by LiquiChip multiplex immunoassays (Qiagen, Valencia, CA).

Limiting dilution MCp assay

The frequency of MCps was assessed as previously described.33 Briefly, small intestines were removed from mice and digested with 10 U collagenase type IV (Worthington Biochemical Corp., Lakewood, NJ) in 25 mL RPMI 1640 and agitated at 37°C for 20 minutes. Cells were separated on a Percoll gradient (47% to 67%) and interphase mononuclear cells were isolated. Mononuclear cells were serially diluted in RPMI 1640 with IL-3 and SCF from 105 cells/well in 96-well plates. Then 105 irradiated splenocytes (3000 rad) were added to each well to 100 μL final volume. Mast cell colonies were identified by toluidine blue staining after 10 to 15 days of culture.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated using an RNeasy kit (Promega, Madison, WI) and Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). Reactions consisted of 0.5 μL complementary DNA or genomic DNA, PerfecTA SYBR Green SuperMix (Quanta BioSciences, Gaithersburg, MD) and 300 nM each of forward and reverse primers. Complementary DNA was quantified using an iCycler iQ5 (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Relative template levels were calculated using the 2–ΔCt method, with Hprt1 as reference gene.

Retroviral transduction

To generate retrovirus, Phoenix-Eco packaging cells were transfected using lipofectamine (Invitrogen) with murine stem cell virus plasmids (pMSCV) plasmids.34 pMSCV-Ik7-IRES-H-2Kk or pMSCV-IRES-H2Kk supernatants were adsorbed onto plates pre-coated with 20 μg/mL Retronectin (Clontech) for 3 hours. After washing the plates, bone marrow cells prestimulated for 12 hours, and IL-3 and SCF were added. Cells were cultured for 2 additional weeks in media with IL-3 alone. Infected cells were purified using anti–H-2Kk MACS beads (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA) for RNA preparation or stained with anti–H-2Kk antibody for cytometry.

IL-3 complex induction and isolation of basophils

Mouse basophils were isolated ex vivo, as previously described.35 In brief, mice were subcutaneously implanted with a mini-osmotic pump (Alzet, Cupertino, CA) containing 5 μg IL-3 (Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ). FcεRI+ CD49b+ basophils were isolated from bone marrow and liver cells by using a fluorescence-activated cell sorter. Purity after sorting was >99%.

ChIP assays

Histone modification and Ikaros-binding assays were performed with 4 × 106 bone marrow-derived mast cells using chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay kits (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA). For Ikaros ChIP, negative control primers amplify a region distant from consensus Ikaros-binding sites. For histone 3, lysine 4 trimethylation (H3K4me3) ChIP, an isotype control was used.

Bone marrow chimeras

Male WBB6-KitW/Wv recipient mice were lethally irradiated (900 cGy) 1 day prior to intravenous injection of 107 wild-type or Ik−/− bone marrow cells. Mice were euthanized either 2 or 4 weeks later for analysis.

Statistics

Except where noted, statistical comparisons were performed using Student unpaired t test. Analyses were performed using Prism 6 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

Results

Ik−/− mice lack intestinal mast cells

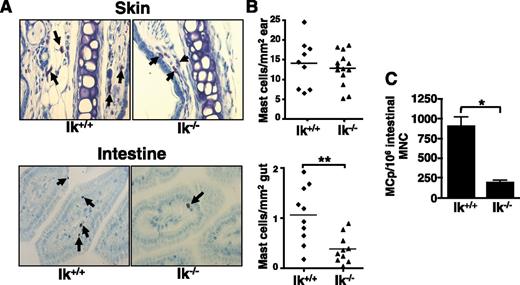

Ikaros is expressed in bone marrow-derived mast cells and regulates Il4 expression,31 prompting us to ask if Ikaros impacts mast cell development in vivo. Mast cell distribution was assessed in Ik−/− mice by toluidine blue staining of tissues. Although mast cell numbers in the skin (Figure 1A), spleen, heart, and dura mater (data not shown) are normal, Ik−/− mice have significantly reduced numbers of intestinal mast cells (Figure 1B). Reduced numbers of MCps are also observed in the small intestines of Ik−/− mice (Figure 1C).

Ik−/− mice exhibit reduced intestinal mast cell numbers. (A) Mast cells (arrows) were identified in Ik−/− mice and their wild-type littermates by toluidine blue staining of sections from ear skin and intestine (original magnification ×40; Zeiss Primo Star with ImagingSource digital camera attachment). (B) Quantification of mast cell numbers in skin and intestine tissue samples. Each data point represents the average number of mast cells observed in an individual mouse counting 4 sections and 5 fields/section. (C) Numbers of MCps in Ik+/+ and Ik−/− mice were assessed by limiting dilution analysis of intestinal mononuclear cells (MNC) in medium containing IL-3 and SCF. Data represents mean MCps from 4 individual mice/group ± standard error of the mean and are representative of 2 independent experiments. *P < .05; ** P < .01.

Ik−/− mice exhibit reduced intestinal mast cell numbers. (A) Mast cells (arrows) were identified in Ik−/− mice and their wild-type littermates by toluidine blue staining of sections from ear skin and intestine (original magnification ×40; Zeiss Primo Star with ImagingSource digital camera attachment). (B) Quantification of mast cell numbers in skin and intestine tissue samples. Each data point represents the average number of mast cells observed in an individual mouse counting 4 sections and 5 fields/section. (C) Numbers of MCps in Ik+/+ and Ik−/− mice were assessed by limiting dilution analysis of intestinal mononuclear cells (MNC) in medium containing IL-3 and SCF. Data represents mean MCps from 4 individual mice/group ± standard error of the mean and are representative of 2 independent experiments. *P < .05; ** P < .01.

Ik−/− bone marrow cells cultured under mast cell differentiation conditions (IL-3 and SCF) exhibit developmental and functional alterations

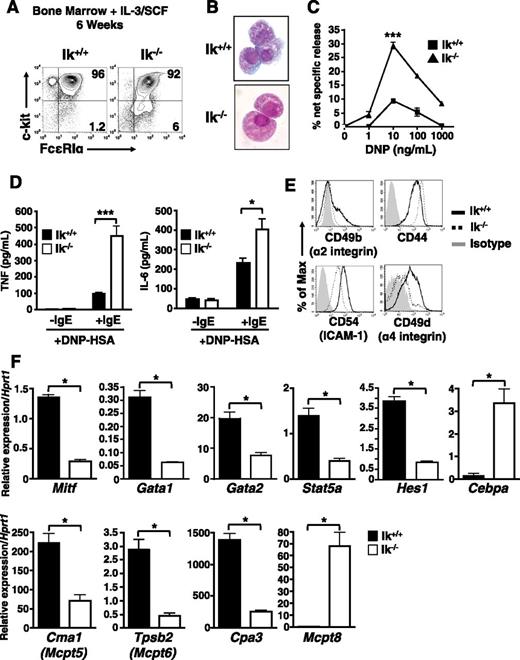

Next, we asked if Ikaros deficiency affects mast cell differentiation or function in vitro. Culture of wild-type bone marrow cells in IL-3 and SCF generates a virtually pure population of c-kithi FcεRI+ mast cells within 4 to 8 weeks.36 In both Ik+/+ and Ik−/− cultures, c-kithi FcεRI+ cells predominate after 6 weeks (Figure 2A). However, subtle differences in cell morphology were observed after staining with Wright-Giemsa (Figure 2B). Ik−/− cells appear less densely granulated with a smoother cell surface than wild-type mast cells.

c-kit+ FcεRI+ cells derived from Ik−/− bone marrow cultured under mast cell differentiation conditions exhibit developmental abnormalities. Ik+/+ and Ik−/− bone marrow was cultured in IL-3 and SCF for 6 weeks. (A) Analysis of c-kit and FcεRI expression by flow cytometry. (B) Ik+/+ and Ik−/− cultures stained with Wright-Giemsa (original magnification ×100). (C) β-hexosaminidase release was determined 30 minutes after FcεRI crosslinking of pre-loaded anti–DNP-IgE and indicated concentrations of DNP-human serum albumin. The percentage of β-hexosaminidase release was calculated as release (%) = supernatant/(supernatant + cell lysate) × 100. Data represents mean of triplicate experiments ± standard error of the mean. ***P < .001 in 10 ng/mL DNP-human serum albumin-treated cultures. (D) Cytokine release at 16 hours postactivation with anti–DNP-IgE and DNP (10 ng/mL) determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Data represents mean of replicates from 3 independent cultures ± standard error of the mean. (E) Basal expression of cell-surface adhesion and activation molecules after 6 weeks in culture. (F) Quantitative reverse transcription PCR analysis of mast cell and basophil lineage-specifying genes in Ik+/+ and Ik−/− cultures. Data are expressed as the mean of 3 separate quantitative RT-PCR analyses ± standard deviation using RNA isolated from same bone marrow culture. *P < .05. Results in panels A-E are representative of 3 independent experiments, and results in panel F are representative of 2 independent experiments.

c-kit+ FcεRI+ cells derived from Ik−/− bone marrow cultured under mast cell differentiation conditions exhibit developmental abnormalities. Ik+/+ and Ik−/− bone marrow was cultured in IL-3 and SCF for 6 weeks. (A) Analysis of c-kit and FcεRI expression by flow cytometry. (B) Ik+/+ and Ik−/− cultures stained with Wright-Giemsa (original magnification ×100). (C) β-hexosaminidase release was determined 30 minutes after FcεRI crosslinking of pre-loaded anti–DNP-IgE and indicated concentrations of DNP-human serum albumin. The percentage of β-hexosaminidase release was calculated as release (%) = supernatant/(supernatant + cell lysate) × 100. Data represents mean of triplicate experiments ± standard error of the mean. ***P < .001 in 10 ng/mL DNP-human serum albumin-treated cultures. (D) Cytokine release at 16 hours postactivation with anti–DNP-IgE and DNP (10 ng/mL) determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Data represents mean of replicates from 3 independent cultures ± standard error of the mean. (E) Basal expression of cell-surface adhesion and activation molecules after 6 weeks in culture. (F) Quantitative reverse transcription PCR analysis of mast cell and basophil lineage-specifying genes in Ik+/+ and Ik−/− cultures. Data are expressed as the mean of 3 separate quantitative RT-PCR analyses ± standard deviation using RNA isolated from same bone marrow culture. *P < .05. Results in panels A-E are representative of 3 independent experiments, and results in panel F are representative of 2 independent experiments.

Differentiated Ik−/− cells exhibit a hyper-responsive phenotype with FcεRI crosslinking, releasing more granule-associated β-hexosaminidase (Figure 2C) and proinflammatory IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor (Figure 2D). There are marked differences in the basal expression of cell surface molecules, including CD49b (integrin α2), CD44, CD54 (intercellular adhesion molecule-1), and, notably, CD49d (integrin α4), required for mast cell gut homing33 (Figure 2E). We also observed increased basal and activation-dependent increases in expression of the costimulatory molecules 4-1BB, CD153 (CD40L), OX40L, and PD-L2 (supplemental Figure 1).

The gene expression profile of Ik−/− cells reflects aberrant mast cell differentiation. Genes associated with mast cell development and function, including Mitf, Gata1, Gata2, Stat5a, Hes1, Cpa3 (carboxypeptidase A3), Cma1 (Mcpt5, mouse mast cell protease-5/chymase), and Tpsb2 (Mcpt6, mouse mast cell protease-6/tryptase)18-20,37 show reduced expression (Figure 2F). These reductions coincide with elevated expression of Cebpa, and of Mcpt8, which encodes a basophil-specific protease.38 Thus, under the influence of IL-3 and SCF, granulated, IgE-responsive mast cells develop with an altered phenotype, including decreased adhesion molecule expression and some features of basophils.

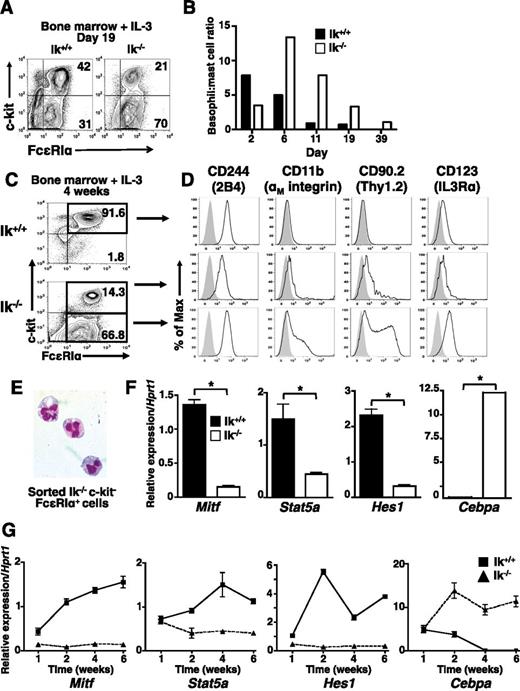

Culture of Ik−/− bone marrow in IL-3 alone results in preferential basophil differentiation

IL-3 alone can support mast cell differentiation, but without SCF, which induces basophil apoptosis,39 IL-3 promotes increased basophil proliferation and survival. To further assess the role of Ikaros in basophil differentiation, wild-type and Ik−/− bone marrow was cultured in IL-3. At day 19 (Figure 3A), as well as at most other time points analyzed (Figure 3B), c-kithi FcεRI+ cells comprise a larger proportion of cells in wild-type IL-3 cultures, whereas c-kit− FcεRI+ cells are more prevalent in Ik−/− cultures.

Basophil-like c-kit− FcεRI+ cells predominate in Ik−/− IL-3 bone marrow cultures. Bone marrow cells from Ik+/+ and Ik−/− mice were cultured in IL-3 (5 ng/mL). (A) The c-kit and FcεRI expression assessed at day 19 of culture. (B) Ratio of percentage of mast cells (c-kithi FcεRI+) to basophils (c-kit− FcεRI+) over time in wild-type and Ik−/− cultures. Results are representative of 8 experiments with independent bone marrow cultures. (C) c-kit and FcεRI expression in cultured bone marrow cells at day 28 of culture. (D) Ik+/+ c-kithi FcεRI+ cells (top panel), Ik−/− c-kit+ FcεRI+ (middle panel), and Ik−/− c-kit– FcεRI+ cells (bottom panel) were analyzed for expression of markers that define the basophil phenotype (2B4+ CD11b+ Thy1.2+ IL3Rαhi, solid lines). Shaded peaks: isotype control antibody. (A-D) Representative of 3 experiments with independent bone marrow cultures. (E) Wright-Giemsa staining of fluorescence-activated cell sorted Ik−/− c-kit– FcεRI+ cells (original magnification ×100), representative of 2 experiments. (F) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of mast cell and basophil lineage-specifying genes in whole Ik+/+ and Ik−/− cultures. Data are the mean of 3 separate quantitative RT-PCR analyses ± standard deviation using RNA isolated from the same bone marrow culture. *P < .05. (G) Kinetics of lineage-determining gene expression assessed by quantitative RT-PCR analysis in IL-3 only Ik+/+ and Ik−/− cultures. Data represents mean of quadruplicates at each time point ± standard error of the mean, representative of 2 experiments.

Basophil-like c-kit− FcεRI+ cells predominate in Ik−/− IL-3 bone marrow cultures. Bone marrow cells from Ik+/+ and Ik−/− mice were cultured in IL-3 (5 ng/mL). (A) The c-kit and FcεRI expression assessed at day 19 of culture. (B) Ratio of percentage of mast cells (c-kithi FcεRI+) to basophils (c-kit− FcεRI+) over time in wild-type and Ik−/− cultures. Results are representative of 8 experiments with independent bone marrow cultures. (C) c-kit and FcεRI expression in cultured bone marrow cells at day 28 of culture. (D) Ik+/+ c-kithi FcεRI+ cells (top panel), Ik−/− c-kit+ FcεRI+ (middle panel), and Ik−/− c-kit– FcεRI+ cells (bottom panel) were analyzed for expression of markers that define the basophil phenotype (2B4+ CD11b+ Thy1.2+ IL3Rαhi, solid lines). Shaded peaks: isotype control antibody. (A-D) Representative of 3 experiments with independent bone marrow cultures. (E) Wright-Giemsa staining of fluorescence-activated cell sorted Ik−/− c-kit– FcεRI+ cells (original magnification ×100), representative of 2 experiments. (F) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of mast cell and basophil lineage-specifying genes in whole Ik+/+ and Ik−/− cultures. Data are the mean of 3 separate quantitative RT-PCR analyses ± standard deviation using RNA isolated from the same bone marrow culture. *P < .05. (G) Kinetics of lineage-determining gene expression assessed by quantitative RT-PCR analysis in IL-3 only Ik+/+ and Ik−/− cultures. Data represents mean of quadruplicates at each time point ± standard error of the mean, representative of 2 experiments.

To confirm the lineage of IL-3-differentiated Ik−/− cells, we evaluated the expression of basophil markers8,40,41 at day 28 (Figures 3C-D). Consistent with a mast cell phenotype, wild-type c-kithi FcεRI+ cells are 2B4+, IL-3Rαlo, CD11b−, and Thy1.2− (Figure 3D, top panel). Ik−/− c-kit− FcεRI+ cells show the 2B4+, CD11b+, Thy1.2+, and IL-3Rαhi phenotype characteristic of basophils (Figure 3D, bottom panel). Ik−/− c-kit+ FcεRI+ cells exhibit an intermediate phenotype with reduced expression of 2B4, CD11b, Thy1.2, and IL-3R compared with wild-type cells (Figure 3D, middle panel). Fluorescence-activated cell sorted Ik−/− c-kit– FcεRI+ cells exhibit the hallmark bi-lobed nucleus of basophils (Figure 3E). As in IL-3 and SCF cultures, Cebpa expression predominates in Ik−/− IL-3 cultures and there is a corresponding reduction in Mitf, Stat5a, and Hes1 expression (Figure 3E). Thus, culture with IL-3 alone in the absence of Ikaros enhances basophil lineage development from bone marrow.

We also investigated the effects of Ikaros deficiency on the kinetics of mast cell and basophil lineage-determining gene expression under IL-3 culture conditions. There is an inducible and steady increase in the expression of Mitf, Stat5, and Hes1 in wild-type, but not Ik−/− cultures through week 6 (Figure 2G). Although Cebpa transcript levels are similar at the beginning of culture, expression declines in wild-type cultures correlating with the normal decline of basophil numbers. In contrast, robust induction of Cebpa is maintained in Ik−/− cultures over time, correlating with basophil persistence. Expression of Gata1, Gata2, and Pu1 is similar in both wild-type and Ik−/− cells at early time points, although some disparities are observed at later times (data not shown). Therefore, Ikaros acts early in response to IL-3 signals to induce expression of mast cell-specifying genes and suppress basophil-specifying genes.

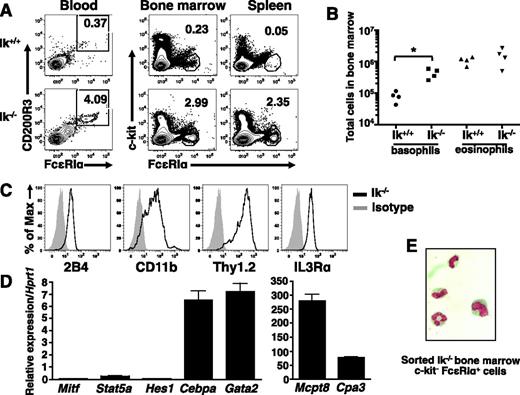

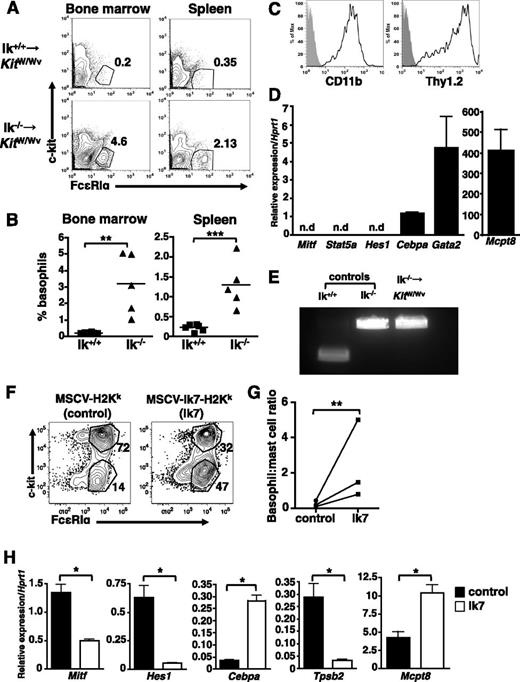

Ik−/− mice exhibit basophilia in the absence of infection

Next, we examined basophils in vivo. There is an increase in the frequency of c-kit− FcεRI+ cells in the blood, bone marrow, and spleen (Figure 4A), as well as liver (not shown) of Ik−/− mice relative to wild-type animals. The absolute numbers of basophils are also increased in the bone marrow (Figure 4B) and spleen (not shown), whereas eosinophil numbers are similar. Isolated Ik−/− c-kit− FcεRI+ bone marrow cells are 2B4+, CD11b+, Thy1.2+, and IL3Rαhi (Figure 4C), and express Cebpa, Gata2, and Mcpt8 transcripts. Cpa3 is expressed at low levels in these cells, and Mitf, Stat5a, and Hes1 transcripts are virtually undetectable (Figure 4D). Staining of sorted cells reveals a segmented granulocytic nucleus (Figure 4E). We conclude that the expanded populations of c-kit− FcεRI+ cells in Ik−/− mice are basophils.

Ik−/− mice exhibit increased basophils in the absence of infection. (A) Proportion of c-kit− FcεRI+ cells in indicated tissues of naive Ik+/+ and Ik−/− mice assessed by flow cytometry. Blood basophils were evaluated for the expression of FcεRI and CD200R3 after gating on c-kit− cells. Numbers denote percentage of basophils. (B) Quantification of basophil (c-kit− FcεRI+ CD200R3+) and eosinophil (c-kit− Ly6G− Siglec-F+) numbers in bone marrow of wild-type and Ik−/− mice by TruCount bead assay. P < .05 (C) Cell surface expression of basophil markers in c-kit– FcεRI+ cells from Ik−/− bone marrow determined by flow cytometry. (D) Fluorescence-activated cell sorted Ik−/− c-kit– FcεRI+ bone marrow cells were subject to quantitative RT-PCR analysis to assess expression of lineage-specific transcription factors and proteases. Data represents mean of triplicates ± standard error of the mean. (E) Fluorescence-activated cell sorted Ik−/− c-kit– FcεRI+ cells bone marrow cells were Wright-Giemsa stained (original magnification, ×100). Results shown in panels A-B are representative of 4 (blood) and 6 (bone marrow, spleen, and liver) of mice of each genotype. (C-D) Representative of 4 mice. (E) Representative of 3 mice.

Ik−/− mice exhibit increased basophils in the absence of infection. (A) Proportion of c-kit− FcεRI+ cells in indicated tissues of naive Ik+/+ and Ik−/− mice assessed by flow cytometry. Blood basophils were evaluated for the expression of FcεRI and CD200R3 after gating on c-kit− cells. Numbers denote percentage of basophils. (B) Quantification of basophil (c-kit− FcεRI+ CD200R3+) and eosinophil (c-kit− Ly6G− Siglec-F+) numbers in bone marrow of wild-type and Ik−/− mice by TruCount bead assay. P < .05 (C) Cell surface expression of basophil markers in c-kit– FcεRI+ cells from Ik−/− bone marrow determined by flow cytometry. (D) Fluorescence-activated cell sorted Ik−/− c-kit– FcεRI+ bone marrow cells were subject to quantitative RT-PCR analysis to assess expression of lineage-specific transcription factors and proteases. Data represents mean of triplicates ± standard error of the mean. (E) Fluorescence-activated cell sorted Ik−/− c-kit– FcεRI+ cells bone marrow cells were Wright-Giemsa stained (original magnification, ×100). Results shown in panels A-B are representative of 4 (blood) and 6 (bone marrow, spleen, and liver) of mice of each genotype. (C-D) Representative of 4 mice. (E) Representative of 3 mice.

Ikaros exerts cell-intrinsic effects on basophil lineage choice in vivo and in vitro

Bone marrow chimeras were generated to assess the potential cell-intrinsic effects of Ikaros on basophil development in vivo. Because mast cells are radiation-resistant, we reasoned that mast cell-deficient KitW/Wv mice would be suitable recipients, allowing us to assess restoration of both mast cell and basophil populations.42,43 However, Ik−/−-transplanted animals had poor survival beyond 1 month, insufficient time for mast cells to repopulate tissues.

Basophils were assessed 2 to 4 weeks after bone marrow transfer. Recipients of Ik−/− bone marrow showed increased c-kit− FcεRI+ CD11b+ Thy1.2+ cells in the bone marrow, spleen (Figures 5A-B), and liver (not shown) relative to wild-type bone marrow recipients, with basophil frequencies comparable to that of naive Ik−/− mice (compare Figure 5A-B with Figure 4A-B). These cells are CD11bhi and Thy1.1+ (Figure 5C). Sorted c-kit− FcεRI+ bone marrow cells express Cebpa, Gata2, and Mcpt8, but not Mitf, Stat5, or Hes1 (Figure 5D). Genotyping confirmed that these cells were Ik−/− and thus transplant-derived (Figure 5E).

Cell-intrinsic actions of Ikaros drive basophil differentiation. Bone marrow chimeras were generated by transferring either wild-type or Ik−/− bone marrow into lethally irradiated KitW/Wv recipients. (A) Flow cytometry of c-kit– FcεRI+ basophils in indicated tissues at 4 weeks. (B) Percentage c-kit– FcεRI+ basophils in the indicated tissues of individual chimeric mice. (C) Basophil lineage marker expression on Ik−/− c-kit– FcεRI+ bone marrow cells. Representative of 4 animals. (D) Fluorescence-activated cell sorted c-kit– FcεRI+ bone marrow cells from Ik−/− - KitW/Wv chimeras express basophil lineage genes, as determined by quantitative RT-PCR. Representative of 4 mice. n.d., not detected. (E) Genotyping of bone marrow basophils sorted from Ik−/− chimeras. Results represent analyses of 2 recipients of Ik−/− bone marrow. (F) Bone marrow cells from Ik+/+ mice were infected with a dominant-negative Ikaros retrovirus (Ik7; MSCV-Ik7-IRES-H-2Kk) or control retrovirus (MSCV-IRES-H-2Kk) prior to culture with IL-3 (5 ng/mL) for 2 weeks. Infected (H-2Kk+) c-kit+ FcεRIα+ and c-kit− FcεRIα+ cells were identified by flow cytometry and (G) basophil:mast cell ratios calculated. (H) H-2Kk+ cells from control and dominant-negative infections were isolated using anti−H-2Kk MACS beads and the expression of lineage-associated genes assessed by quantitative RT-PCR. Data are expressed as the mean of 3 separate analyses ± standard deviation using RNA isolated from same bone marrow culture. Each complementary DNA primer set was run in triplicate. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001.

Cell-intrinsic actions of Ikaros drive basophil differentiation. Bone marrow chimeras were generated by transferring either wild-type or Ik−/− bone marrow into lethally irradiated KitW/Wv recipients. (A) Flow cytometry of c-kit– FcεRI+ basophils in indicated tissues at 4 weeks. (B) Percentage c-kit– FcεRI+ basophils in the indicated tissues of individual chimeric mice. (C) Basophil lineage marker expression on Ik−/− c-kit– FcεRI+ bone marrow cells. Representative of 4 animals. (D) Fluorescence-activated cell sorted c-kit– FcεRI+ bone marrow cells from Ik−/− - KitW/Wv chimeras express basophil lineage genes, as determined by quantitative RT-PCR. Representative of 4 mice. n.d., not detected. (E) Genotyping of bone marrow basophils sorted from Ik−/− chimeras. Results represent analyses of 2 recipients of Ik−/− bone marrow. (F) Bone marrow cells from Ik+/+ mice were infected with a dominant-negative Ikaros retrovirus (Ik7; MSCV-Ik7-IRES-H-2Kk) or control retrovirus (MSCV-IRES-H-2Kk) prior to culture with IL-3 (5 ng/mL) for 2 weeks. Infected (H-2Kk+) c-kit+ FcεRIα+ and c-kit− FcεRIα+ cells were identified by flow cytometry and (G) basophil:mast cell ratios calculated. (H) H-2Kk+ cells from control and dominant-negative infections were isolated using anti−H-2Kk MACS beads and the expression of lineage-associated genes assessed by quantitative RT-PCR. Data are expressed as the mean of 3 separate analyses ± standard deviation using RNA isolated from same bone marrow culture. Each complementary DNA primer set was run in triplicate. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001.

To further validate the cell-intrinsic actions of Ikaros, wild-type bone marrow was infected with MSCV-Ik7-IRES-H2Kk, a retrovirus that expresses a dominant-negative Ik isoform (Ik7) or control MSCV-IRES-H2Kk.44 After culture for 2 weeks with IL-3, c-kit+ FcεRIα+, and c-kit− FcεRIα+ cells were identified within the infected (H-2Kk+) populations. The proportion of c-kit− FcεRIα+ cells is substantially higher in Ik7-transduced cultures than in cultures infected with control virus (Figure 5F). Purified H-2Kk+, Ik7-transduced cells show reduced expression of Mitf, Hes1, and Tpsb2 (Mcpt6), and increased Cebpa and Mcpt8 expression compared with control cells (Figure 5G). We examined the phenotype of uninfected (H-2Kk−) cells in control- and Ik7-infected cultures (supplemental Figure 2) and saw no difference in the mast cell to basophil ratios. Together, these findings support the idea that Ikaros acts intrinsically in response to IL-3 signaling to suppress basophil differentiation.

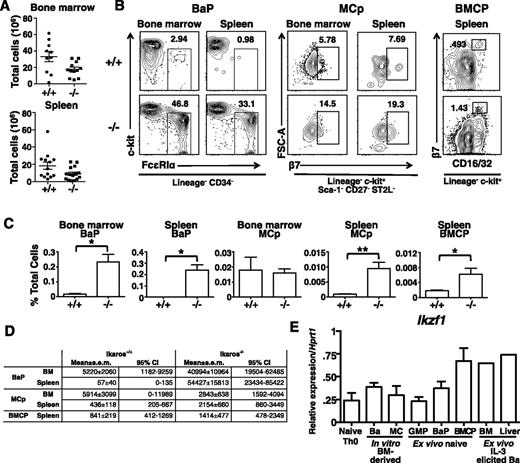

BaPs are increased in Ik−/− mice

To determine if basophil expansion was a result of earlier Ikaros-driven changes in precursors, we compared the distribution of basophil-associated myeloid progenitors in the bone marrow and spleen of wild-type and Ik−/− mice. As previously reported,45,46 Ik−/− bone marrow has reduced numbers of lymphocytes, whereas in the spleen, total numbers are similar to that of wild-type mice (Figure 6A). The Lin− Sca-1+ c-kit+, but not the Lin− Sca-1− c-kit+ compartment in the bone marrow is expanded in Ik−/− mice. Within the Lin− Sca-1+ c-kit+ compartment, there is a complete loss of CD34+ CD135+ lymphomyeloid primed progenitors, whereas within the Lin− Sca-1− c-kit+ compartment, CD34+ CD16/32+ granulocyte-monocyte progenitors are reduced (supplemental Figure 3).

Direct progenitors of basophils express Ik and are increased in Ik−/−mice. Bone marrow and spleen leukocytes were isolated from Ik+/+ (+/+) and Ik−/− (−/−) mice. (A) Total leukocytes in bone marrow (bilateral femoral/tibial) and spleen of +/+ and −/− animals. Mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) (n = 10 for +/+, n = 11 for −/−). (B) Representative plots of Lin− CD34+ FceRIa+ c-kit− BaPs and Lin− Sca-1− c-kit+ CD27− ST2L+ β7 integrin+ mast cell progenitors in bone marrow and the spleen and Lin− c-kit+ CD16/32+ β7 integrinhi BMCP in the spleen of Ik+/+ and Ik−/− mice. Numbers represent percentage of parent gate indicated below plots. (C) Quantification of frequencies of indicated cell types as a percentage of total SYTOX− (live) cells in flow sample. Bone marrow and spleen BaP (n = 5 for +/+ and −/−); bone marrow and spleen MCp (n = 5 for +/+ and n = 6 for −/−); BMCP (n = 10 for +/+ and 11 for −/−). (D) Estimated mean absolute cell numbers per organ and 95% confidence interval of mean for indicated cell types, derived from means and SEM of frequency and total cell data in panels A,C. Independence was assumed and SEM were combined by the formula:  . (E) Expression of Ikzf1 (all Ik isoforms) in indicated cell populations assessed by quantitative RT-PCR. CD4+ T cells were isolated from naive mice. In vitro bone marrow (BM)-derived basophil cells are isolated from 9-day cultures and mast cells, from 6-week cultures with IL-3 alone. GMPs, BaPs were sorted from bone marrow while purified BMCPs were isolated from spleen. Ex vivo–elicited basophils were derived from the bone marrow and livers of mice after treatment with IL-3 complexes (n = 1 for ex vivo IL-3–elicited complex basophils; n = 3 for other samples). *P < .05; **P < .01.

. (E) Expression of Ikzf1 (all Ik isoforms) in indicated cell populations assessed by quantitative RT-PCR. CD4+ T cells were isolated from naive mice. In vitro bone marrow (BM)-derived basophil cells are isolated from 9-day cultures and mast cells, from 6-week cultures with IL-3 alone. GMPs, BaPs were sorted from bone marrow while purified BMCPs were isolated from spleen. Ex vivo–elicited basophils were derived from the bone marrow and livers of mice after treatment with IL-3 complexes (n = 1 for ex vivo IL-3–elicited complex basophils; n = 3 for other samples). *P < .05; **P < .01.

Direct progenitors of basophils express Ik and are increased in Ik−/−mice. Bone marrow and spleen leukocytes were isolated from Ik+/+ (+/+) and Ik−/− (−/−) mice. (A) Total leukocytes in bone marrow (bilateral femoral/tibial) and spleen of +/+ and −/− animals. Mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) (n = 10 for +/+, n = 11 for −/−). (B) Representative plots of Lin− CD34+ FceRIa+ c-kit− BaPs and Lin− Sca-1− c-kit+ CD27− ST2L+ β7 integrin+ mast cell progenitors in bone marrow and the spleen and Lin− c-kit+ CD16/32+ β7 integrinhi BMCP in the spleen of Ik+/+ and Ik−/− mice. Numbers represent percentage of parent gate indicated below plots. (C) Quantification of frequencies of indicated cell types as a percentage of total SYTOX− (live) cells in flow sample. Bone marrow and spleen BaP (n = 5 for +/+ and −/−); bone marrow and spleen MCp (n = 5 for +/+ and n = 6 for −/−); BMCP (n = 10 for +/+ and 11 for −/−). (D) Estimated mean absolute cell numbers per organ and 95% confidence interval of mean for indicated cell types, derived from means and SEM of frequency and total cell data in panels A,C. Independence was assumed and SEM were combined by the formula:  . (E) Expression of Ikzf1 (all Ik isoforms) in indicated cell populations assessed by quantitative RT-PCR. CD4+ T cells were isolated from naive mice. In vitro bone marrow (BM)-derived basophil cells are isolated from 9-day cultures and mast cells, from 6-week cultures with IL-3 alone. GMPs, BaPs were sorted from bone marrow while purified BMCPs were isolated from spleen. Ex vivo–elicited basophils were derived from the bone marrow and livers of mice after treatment with IL-3 complexes (n = 1 for ex vivo IL-3–elicited complex basophils; n = 3 for other samples). *P < .05; **P < .01.

. (E) Expression of Ikzf1 (all Ik isoforms) in indicated cell populations assessed by quantitative RT-PCR. CD4+ T cells were isolated from naive mice. In vitro bone marrow (BM)-derived basophil cells are isolated from 9-day cultures and mast cells, from 6-week cultures with IL-3 alone. GMPs, BaPs were sorted from bone marrow while purified BMCPs were isolated from spleen. Ex vivo–elicited basophils were derived from the bone marrow and livers of mice after treatment with IL-3 complexes (n = 1 for ex vivo IL-3–elicited complex basophils; n = 3 for other samples). *P < .05; **P < .01.

Next, we examined direct precursors of mast cells and basophils. Although Lin− c-kit+ CD34+ FcεRIα− CD27− ST2L+ MCp16 are present in similar proportions, Lin− CD34+ c-kit− FcεRIα+ BaP and splenic Lin− c-kit+ CD34+ CD16/32+ β7hi BMCP1 are expanded as a proportion of all cells analyzed, with BaP increased approximately 10-fold. Similarly, BMCP formed a formed a larger proportion of total cells in Ik−/− spleen (Figures 6B-C). Calculated absolute cell numbers recapitulated the changes seen in proportional analyses (Figure 6D).

We observed a population of β7mid-lo cells in the Lin− c-kit+ gate in Ik−/− spleens that is not present in Ik+/+ mice. Thus, we measured levels of other splenic myeloid progenitors and observed increases in progenitors normally restricted to bone marrow, including GMP, BaP, and MCp (supplemental Figure 4). The absolute numbers of these cells were also increased (supplemental Table 2). We conclude that basophilia in Ik−/− mice is a consequence of expansion of direct progenitors, and that splenic myelopoiesis may also supply basophils in these animals.

The preferential expansion of basophils in Ik-deficient mice indicates that Ik normally suppresses basophil development. Thus it was predicted that Ikaros expression is extinguished during normal basophil differentiation. To assess this possibility, we measured Ikzf1 transcript levels in wild type cells by quantitative RT-PCR using primers complementary to sequences within exons 1 and 7. Surprisingly, Ikaros transcripts were detected in sorted IL3-cultured bone marrow basophils, in basophils isolated directly from IL-3 complex-stimulated mice, and in sorted GMP, BMCP, and BaP (Figure 6E). The relative levels of expression were similar to those in mast cells and naive T cells. Thus, normal basophil differentiation is not associated with a downregulation or complete loss of Ikzf1 gene expression.

Ikaros binds directly to Cepba and Hes1, and loss of Ikaros alters H3K4me3 status

Loss of Ikaros activity results in altered expression of multiple genes that contribute to mast cell-basophil lineage choice and function. Reciprocal expression of Hes1 and Cebpa is particularly notable, as Hes1, a notch target, which is necessary for mast cell development and directly inhibits Cebpa expression.47 Similar cross-repression between C/EBP-α and MITF, another critical mast cell factor, has recently been demonstrated.48 RVista/MultiTF analyses revealed that both Hes1 and Cebpa have multiple consensus Ikaros-binding sites that are often clustered with consensus STAT and GATA sites, as previously observed within the Il4 locus49 (Figure 7A), while Mitf lacked these clusters (data not shown). ChIP assays were performed with wild-type bone marrow-derived mast cells after 4 weeks of IL-3 culture to evaluate Ikaros-binding at clustered sites. Ikaros associates with multiple regions flanking the Cebpa coding region as well as the Hes1 promoter region (Figure 7B). These regions were assessed for H3K4 trimethylation (H3K4me3), a stable chromatin modification most often associated with poised or actively transcribed chromatin50,51 in week 4 wild-type and Ik−/− cultures. Wild-type cells exhibit decreased H3K4me3 at the Cepba locus and increased H3K4me3 at the Hes1 promoter when compared with Ik−/− cells (Figure 7C).

Ikaros binds to the Cebpa and Hes1 genes, and loss of Ik results in altered histone modifications. (A) RVista/MultiTF analysis of consensus Ikzf1 (Ik), Stat5a- and Gata-binding sites (tick marks) in the flanking regions (transcriptional start site and 3′ CNS regions [II-IV]) of the Cebpa gene and upstream region of the Hes1 gene (promoter [Hes1p]). BLUE peaks and boxes denote exons and YELLOW, PINK and RED peaks designate intergenic or flanking regions exhibiting interspecies homology. (B) ChIP assays detect Ikaros-binding to the Cebpa and Hes1 genes in wild-type bone marrow derived mast cells. Primers flanking indicated regions (green boxes) were used. Data are expressed as percent of total input DNA. Negative controls (n.c.) include quantitative RT-PCR amplification with primers for a sequence distant from any known Ikaros-binding site. (C) H3K4me3 histone modifications at consensus Ikaros-binding sites, assessed by ChIP. Data are expressed as percent of total input DNA after subtraction of IgG control values. Results shown in panels B-C are representative of 4 experiments using 2 independent bone marrow cultures derived from wild-type and Ik−/− mice.

Ikaros binds to the Cebpa and Hes1 genes, and loss of Ik results in altered histone modifications. (A) RVista/MultiTF analysis of consensus Ikzf1 (Ik), Stat5a- and Gata-binding sites (tick marks) in the flanking regions (transcriptional start site and 3′ CNS regions [II-IV]) of the Cebpa gene and upstream region of the Hes1 gene (promoter [Hes1p]). BLUE peaks and boxes denote exons and YELLOW, PINK and RED peaks designate intergenic or flanking regions exhibiting interspecies homology. (B) ChIP assays detect Ikaros-binding to the Cebpa and Hes1 genes in wild-type bone marrow derived mast cells. Primers flanking indicated regions (green boxes) were used. Data are expressed as percent of total input DNA. Negative controls (n.c.) include quantitative RT-PCR amplification with primers for a sequence distant from any known Ikaros-binding site. (C) H3K4me3 histone modifications at consensus Ikaros-binding sites, assessed by ChIP. Data are expressed as percent of total input DNA after subtraction of IgG control values. Results shown in panels B-C are representative of 4 experiments using 2 independent bone marrow cultures derived from wild-type and Ik−/− mice.

Discussion

These studies establish a critical and cell-intrinsic role for Ikaros in basophil development in vitro and in vivo, although we cannot exclude the possibility that Ikaros also has extrinsic influences. Ikaros affects the expression of multiple lineage-specifying genes, including Cebpa,1,48 Mitf,4,48 and Hes1.47 At least two of these, Cebpa, required for basophil differentiation, and Hes1, a mast-cell specifying factor,47 appear to be direct targets of Ikaros in differentiated cells as Ikaros-binding is detected at regulatory sequences within these gene loci. In IL-3–differentiated Ik−/− cells, changes in H3K4me3 modifications are observed at these loci as well, reflecting aberrant increased (Cebpa) or decreased (Hes1) gene expression. In view of the central role that C/EBP-α plays in basophil development, loss of Ikaros-mediated suppression of Cebpa coupled with decreased expression of Hes1 and Mitf in BaPs provides a molecular explanation for basophil expansion in Ik−/− mice.

It is still unclear where Ikaros acts during the transition from a multipotent precursor to a committed basophil. In addition to previously reported increases in GMPs,45 we observe dramatic increases in the proportion and total numbers of BaPs and BMCPs in both the bone marrow and the spleen. However, there does not appear to be a corresponding net reduction in MCps when total numbers in the bone marrow and spleen are considered together. Thus, we speculate that the loss of Ikaros results in preferential GMP to BaP differentiation, a possibility we intend to investigate in the future.

Our data does not support a role for Ikaros in mast cell-basophil lineage choice in vivo. Despite profound alterations in mast cell development in vitro, there are no overall deficits in MCps, and only intestinal mast cell populations are reduced in Ik−/− mice. Therefore, basophil expansion does not occur at the expense of mast cell development, and Ikaros-independent pathways of mast cell differentiation must exist. Although Ikaros can affect mast cell differentiation in vitro, the major effects are observed in cultures with IL-3 and no SCF. The addition of SCF, which drives basal mast cell differentiation, can induce mast cell development in vitro in the absence of Ikaros, albeit with an altered phenotype, suggesting that SCF/c-kit signals may be partially Ikaros-independent.

If mast cell development is relatively normal in Ik−/− mice, how can the selective loss of intestinal mast cells and MCp in Ik−/− mice be explained? The pronounced reduction in the expression of CD49d, the α4 integrin subunit that pairs with β7, may provide a clue. The α4β7 integrin is required for directing mast cell precursors to the gut,33 and we speculate that deficits in α4β7 expression result in impaired homing of MCps in Ik−/− mice, and thus reduced intestinal mast cell numbers. It remains to be determined whether Ikaros affects mast cell function. Unfortunately, the lack of most lymphoid cells and early mortality of Ik−/− mice preclude in vivo assessment of mast cell function in most disease models.

Ikaros regulates fate decisions in several multipotent precursor cells, including naive CD4+ T cells.24,49,52 Still, how Ikaros integrates the unique differentiation signals that yield these distinct effector cells is unknown. Basophil differentiation and expansion can normally occur in infection settings where high levels of IL-3 are produced by CD4+ T cells.53-55 We initially considered a model in which Ikaros expression is extinguished in BaPs in response to IL-3 or other basophil-inducing signals leading to de-repression of Cebpa and repression of Hes1 and Mitf. However, basophils and their precursors express Ikaros messenger RNA at levels similar to mast cells and T cells, indicating an alternative hypothesis. That is, Ikaros function is altered through post-translational modifications or alternate isoform usage in response to differentiation signals, such as IL-3. There is evidence to support this contention. Ikaros comprises a family of dimerizing isoforms, which can differ in DNA-binding capacity.56,57 Interaction of non-DNA-binding isoforms with DNA-binding isoforms has been shown to prevent the association of Ikaros with target genes,44 indicating that selective isoform expression can modulate Ikaros function. DNA-binding isoforms undergo changes as a result of RNA splicing as lymphoid lineage commitment proceeds.58 Similarly, a decrease in the expression of Ik1 and Ik2 isoforms is observed in activated Th1, but not Th2 cells.59 Within the myeloid lineage, early myeloid/neutrophil precursors have unique patterns of isoform expression,58,60,61 and expression of dominant-negative Ikaros isoforms is often observed in some leukemia subtypes.62

In summary, our results show that Ikaros restricts basophil expansion under steady-state conditions. Basophils are normally scarce, comprising less than 0.5% of total leukocytes in blood, bone marrow, and the spleen.2 We propose that in the steady state, where basal levels of SCF and IL-3 are present, Ikaros activity is sustained, promoting expression of Mitf and Hes1 and repression of Cebpa in progenitor populations. Subsequently, Hes1 and MITF may directly contribute to Cebpa repression. When IL-3 is abundant, basophil differentiation is favored due to a reduction of Ikaros activity, perhaps via altered isoform expression, releasing Cebpa suppression. Given the profound influence that basophils exert on inflammation in allergic disease, autoimmunity, cancer, and infection, our data provide strong rationale for future studies aimed at more detailed dissection of the mechanisms underlying the control of the development of these cells by Ikaros.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Susan Winandy, Boston University, for the Ik−/− mice.

This work was supported by funding from the Northwestern University Flow Cytometry Facility and by a grant from the National Institutes of Health National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support (P30CA060553, R21AI88299) (M.A.B.), (NRSA F30ES017378) (C.S.), and an American Heart Association postdoctoral fellowship to K.N.R.

Authorship

Contributions: K.N.R., C.S., and G.D.G. designed and performed experiments, analyzed results, and made figures; K.N.R., C.S., and M.A.B. designed the research and wrote the manuscript; and B.M. prepared and provided essential experimental samples.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Melissa Ann Brown, Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, 303 E Chicago Ave, Tarry 6-701, Chicago, IL 60611; e-mail: m-brown12@northwestern.edu.

References

Author notes

K.N.R. and C.S. contributed equally to this work.

![Figure 7. Ikaros binds to the Cebpa and Hes1 genes, and loss of Ik results in altered histone modifications. (A) RVista/MultiTF analysis of consensus Ikzf1 (Ik), Stat5a- and Gata-binding sites (tick marks) in the flanking regions (transcriptional start site and 3′ CNS regions [II-IV]) of the Cebpa gene and upstream region of the Hes1 gene (promoter [Hes1p]). BLUE peaks and boxes denote exons and YELLOW, PINK and RED peaks designate intergenic or flanking regions exhibiting interspecies homology. (B) ChIP assays detect Ikaros-binding to the Cebpa and Hes1 genes in wild-type bone marrow derived mast cells. Primers flanking indicated regions (green boxes) were used. Data are expressed as percent of total input DNA. Negative controls (n.c.) include quantitative RT-PCR amplification with primers for a sequence distant from any known Ikaros-binding site. (C) H3K4me3 histone modifications at consensus Ikaros-binding sites, assessed by ChIP. Data are expressed as percent of total input DNA after subtraction of IgG control values. Results shown in panels B-C are representative of 4 experiments using 2 independent bone marrow cultures derived from wild-type and Ik−/− mice.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/122/15/10.1182_blood-2013-04-494625/4/m_2572f7.jpeg?Expires=1767781839&Signature=nihAujm7qWhR~5KjSQ7FpVPVeme-Fccd1KXHIHUNGm~tulzin0oibYJR2lS6Y8dBIT7PYx~q1C7p9uAUBGJayKZ501gcYPwMx8sxPwu93wMH7ESf5wR1XujeDOxWp4oXzrvqMONXe-cXJSidXWaQ595ukNaDW8niE9MAgcYVflxLOGepNy3~2hqK-VJEvOQ99RfAMgC0gpIW6gR0xCgEBn1EYYOv-gAUjy~7XQCi~eeuNus7QQXlZrAxHzku5tPMgSTbtJMhPVfPwyAbH5y9wTNnpMaYONrAICUPjEQv4zPpW7HUYUXMqn2oWcRuP4Him3KBta~gcDC7WOlv1JGQTA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)