Key Points

T cells genetically targeted to the tumor-promoting antigen CD44v6 are effective against AML and MM.

CD44v6-targeted T cells do not recognize hematopoietic stem cells and keratinocytes but cause reversible monocytopenia.

Abstract

Genetically targeted T cells promise to solve the feasibility and efficacy hurdles of adoptive T-cell therapy for cancer. Selecting a target expressed in multiple-tumor types and that is required for tumor growth would widen disease indications and prevent immune escape caused by the emergence of antigen-loss variants. The adhesive receptor CD44 is broadly expressed in hematologic and epithelial tumors, where it contributes to the cancer stem/initiating phenotype. In this study, silencing of its isoform variant 6 (CD44v6) prevented engraftment of human acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and multiple myeloma (MM) cells in immunocompromised mice. Accordingly, T cells targeted to CD44v6 by means of a chimeric antigen receptor containing a CD28 signaling domain mediated potent antitumor effects against primary AML and MM while sparing normal hematopoietic stem cells and CD44v6-expressing keratinocytes. Importantly, in vitro activation with CD3/CD28 beads and interleukin (IL)-7/IL-15 was required for antitumor efficacy in vivo. Finally, coexpressing a suicide gene enabled fast and efficient pharmacologic ablation of CD44v6-targeted T cells and complete rescue from hyperacute xenogeneic graft-versus-host disease modeling early and generalized toxicity. These results warrant the clinical investigation of suicidal CD44v6-targeted T cells in AML and MM.

Introduction

The adoptive transfer of tumor-reactive T lymphocytes, known as adoptive T-cell therapy (ACT), is a potentially curative form of cancer treatment.1 Akin to passive immunotherapy with monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), ACT is expected to tackle tumors with higher specificity than conventional radiochemotherapy. Adoptively transferred tumor-reactive T cells, however, possess many incremental advantages over mAbs, including direct tumor killing, optimal tissue biodistribution, and the capacity to expand and persist long term after tumor recognition in vivo. Despite its many benefits, the universal application of ACT is challenged by several difficulties associated with personalized medicine. Genetically targeting T cells with clonal T-cell receptors (TCRs)2 or chimeric antigen receptors (CARs)3 is a fast track for effective antigen-specific redirection of T cells against autologous tumors. In particular, CARs are constructed by fusing the single chain variable fragment (scFv) of an mAb specific for a surface antigen with an intracellular signaling domain4 and are therefore major histocompatibility complex-independent. Moreover, different from potentially mispairable TCR heterodimers,5 CARs are monomeric receptors unable to generate unexpected specificities.

After reports that were initially disappointing,6 the most recent clinical results with CAR-redirected T cells containing additional signaling domains from CD28,7-9 4-1BB,10 or both,11 including impressive response rates in the case of CD19 targeting on chronic lymphoid leukemia,12-14 non-Hodgkin lymphoma11,14 and acute lymphoid leukemia,15,16 have fostered renewed enthusiasm in this form of ACT. Even so, translating the results obtained in B-cell malignancies to other tumor types urgently awaits the validation of CAR targets different from B cell–lineage antigens. Clinical programs are currently investigating CAR redirection against already known mAb targets, including CD30 in Hodgkin lymphoma,17 HER2 in solid18 and brain tumors,19 the vascular endothelial growth factor–2 in melanoma and renal cell carcinoma,20 endothelial growth factor in glioma,21 and mesothelin in mesothelioma.22 Despite intense preclinical research on innovative targets,23,24 developing CARs for multiple, rather than single, tumor types would be preferable. Moreover, to avoid immune evasion as a result of antigen-loss variants, it appears imperative to select targets required for tumor growth in vivo.

The hyaluronate receptor CD44 is a class I membrane glycoprotein overexpressed in hematologic and epithelial tumors. CD44 is commonly used as a marker for the prospective identification of cancer stem/initiating cells, possibly playing a crucial role in their phenotype.25 In mice, CD44−/− hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) transduced with the BCR-ABL oncogene fail to initiate leukemia in secondary recipients.26 By analogy, a CD44-specific mAb has been shown to eradicate human acute myeloid leukemia (AML) stem/initiating cells in xenograft models, partially by inhibiting their homing to the bone marrow (BM).27 Although that is appealing, CD44 is expressed ubiquitously, ruling out the opportunity for clinically meaningful CAR redirection. On the contrary, because the expression pattern of its alternatively spliced isoforms is relatively tumor restricted,28 an isoform-specific CAR would have a more acceptable safety profile. In particular, the isoform variant 6 (CD44v6) is expressed in AML29 and multiple myeloma (MM),30 where it correlates with a poor prognosis, and in pancreatic, breast, and head/neck cancers, where it contributes to the metastatic process.31 Importantly, CD44v6 is absent in HSCs32 and displays a low level of expression on normal cells, including activated T cells, monocytes, and keratinocytes.

AML and MM tend to recur after variable periods of remission, induced by conventional radiochemotherapy, indicating that leukemia and putative myeloma stem/initiating cells are relatively resistant to cytotoxic drugs and radiation. On the contrary, the curative results achieved by the graft-versus-leukemia and myeloma effects after allogeneic HSC transplantation33,34 imply that they may be highly sensitive to the attack of T cells. In this work, we show that CD44v6 is required for AML and MM cell growth in vivo, and we demonstrate that T cells targeted to CD44v6 with a newly designed CAR are capable of mediating potent antileukemia and antimyeloma effects without harming HSCs or keratinocytes. Moreover, we validate the co-expression of clinical-grade suicide genes as a tool for controlling the adverse events potentially deriving from predicted monocytopenia.

Material and methods

Patients and donors

All protocols were approved by the institutional review board and samples were collected under written informed consent according to the Declaration of Helsinki. Patient characteristics are listed in supplemental Tables 1 and 2 (available on the Blood Web site). Healthy donor blood was obtained from the blood bank of our institution and cord blood (CB) units were obtained from the Anthony Nolan Institute (London, UK). Mononuclear cells were isolated by density-gradient centrifugation (Lymphoprep; Fresenius).

Retroviral and lentiviral constructs

We constructed the CD44v6-specific short hairpin RNA (shRNA) by replacing the pri-miR223 upper stem with base-paired CD44v6-specific oligonucleotides, maintaining the flanking and loop sequences.35,36 The shRNAs were cloned in a third-generation lentiviral vector (LV), including the mOrange marker gene. We derived the CAR scFv from a mutated sequence (BIWA-8) of the humanized CD44v6-specific mAb bivatuzumab. The scFv was cloned with a CD28 signaling domain and the CD3 ζ chain,9 using the IgG1/CH2CH3 spacer. We expressed the CAR into a SFG-retroviral vector (RV) or into self-inactivating LV with a PGK bidirectional promoter,37 driving the co-expression of the herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase38 or the inducible caspase 939 suicide genes.

Real-time quantitative PCR

First-strand complementary DNA was analyzed from a panel of normal tissues (TissueScan; Origene) and, after reverse transcription, from CB CD34-selected cells, peripheral-blood CD14-selected monocytes, and tumor cells. Amplifications were performed with SyberGreen polymerase chain reaction (PCR) MasterMix (Applied Biosystem) and gene-specific primers.40 CD44v6 expression levels were analyzed in triplicate, normalized to β-actin, and calculated according to the CT method.

Flow cytometry

We used mAbs specific for human CD44v6, CD44, CD4 (e-Bioscience), CD123, CD19, CD14, CD3, CD8, CD45RA, CD62L, CXCR4, interleukin (IL)-7Rα, CD33, CD34, CD38, CD45, and mouse Ly5.1 (BD Biosciences). CAR expression was detected with a mAb specific for the IgG1/CH2CH3 spacer (The Jackson Laboratory). Samples were run through a fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) Canto II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences), and data were analyzed with the FlowJo software (Tree Star, Inc.). Relative fluorescence intensity (RFI) was calculated as follows: mean fluorescence intensity after mAb staining/mean fluorescence intensity after isotype-control staining.

Histology and immunohistochemistry

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections from human normal tissues were stained with hematoxylin and eosin, counterstained with mAbs to human CD68R (PGM1; Dako) and CD44v6 (VFF-18; eBiosciences), and revealed with the avidin-biotin peroxidase complex method. All images were acquired with a Zeiss Axioskop Plus microscope.

Transduction and culture conditions

We activated T cells using beads conjugated to mAbs to CD3 and CD28 (ClinExVivo; Invitrogen) or with plastic-bound OKT3 (30 ng/mL; OrthoBiotec) and anti-CD28 mAb (1 μg/mL; PharMingen). T cells were RV-transduced by 2 rounds of spinoculation or LV-transduced by overnight incubation. T cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 (Gibco-Brl) 10% fetal bovine serum (BioWhittaker) with IL-2 (100 IU/mL; Chiron) or with IL-7 and IL-15 (5 ng/mL; Peprotech). Expansion is expressed as fold increase: T-cell number at day ×/T cell number at day 0. Tumor cells were LV-transduced by overnight incubation and FACS-sorted with mOrange. Tumor cell lines were cultured in RPMI 1640, and primary tumor cells were cultured in X-vivo15 (BioWhittaker) with IL-3 and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (AML, 20 ng/mL each; Peprotech) or IL-6 (MM, 2 ng/mL; Peprotech). Primary keratinocytes were grown in Epi-Life with the human keratinocytes growth supplement (Invitrogen).

In vitro assays of antitumor efficacy and safety

In chromium-release assays, CAR-redirected T cells were incubated with radio-labeled target cells at different effector to target ratios (E:T) for 4 hours. Specific lysis was calculated as follows: 100 × (average experimental cpm − average spontaneous cpm)/(average maximum cpm − average spontaneous cpm). In coculture assays, transduced T cells were cultured with target cells with or without human BM-derived stromal cells HS5. After 4 days, surviving cells were counted and analyzed by FACS. T cells transduced with an irrelevant CAR (CD19 or GD2) were always used as control. The elimination index was calculated as follows: 1 − (number of residual target cells in presence of CD44v6.CAR28z+ T cells)/(number of residual target cells in presence of CTR.CAR28z+ T cells). Coculture supernatants were analyzed for cytokine production with the CBA assay (BD Biosciences). Suicide gene functionality was analyzed after exposing transduced T cells to increasing concentrations of ganciclovir (GCV; Recordati) or the chemical inducer of dimerization (CID) AP1903 (Clontech Laboratories) for 7 days, respectively. Surviving T cells were analyzed by counting and FACS after annexin V/7AAD staining. The survival index was calculated as follows: number of surviving cells after exposure to the drug/number of surviving cells after exposure to vehicle. In colony-forming assays, CB CD34-selected cells were incubated for 4 hours with CAR-redirected T cells at an E:T ratio of 4:1, plated in a methylcellulose-based medium (StemCell Technologies, Inc.), and, after 14 days, quantitatively analyzed for the generation of granulocyte macrophage colony-forming units (GM-CFU) and erythrocyte CFU (E-CFU) by optical microscopy.

In vivo xenograft models of antitumor efficacy and safety

Experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. NSG mice (The Jackson Laboratory) were infused intravenously with wild-type or with LV-transduced tumor cells (1-2 × 106 THP-1 leukemia or MM1.S myeloma cells/mouse, 5 × 106 primary leukemic blasts/mouse). Tumor cells were followed in the peripheral circulation and, after euthanizing the mice, analyzed in the different organs by FACS. For ACT experiments with tumor cell lines, NSG mice were infused with tumor cells and, after 3 days, treated intravenously with 5 × 106 CD44v6.CAR28z+ or CTR.CAR28z+ T cells. For ACT experiments with primary tumor cells, NSG mice were infused with leukemic blasts and after 14 days treated with autologous CAR-redirected T cells. For experiments with HSCs, NSG mice transgenic for human IL-3, granulocyte macrophage–CSF, and stem cell factor (NSG-3GS; The Jackson Laboratory)41 were irradiated sublethally, infused intravenously with 4 × 104 CB CD34-selected cells, and, after 4 weeks, infused with autologous CAR-redirected T cells and monitored for hematopoietic reconstitution. For hyperacute xenogeneic graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) experiments, NSG mice were irradiated sublethally, infused intraperitoneally with 5 × 106 FACS-sorted CAR-redirected T cells expressing iC9, and monitored for weight loss. If they lost >20% of their initial weight, mice were treated with AP1903 (50 μg) and followed for disease progression.

Statistical analysis

When appropriate, we relied on descriptive statistics or compared the data sets by 2-tailed Student t tests, 1- or 2-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), or the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U tests. Differences with a P value < .05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

CD44v6 is required for AML and MM engraftment in NSG mice

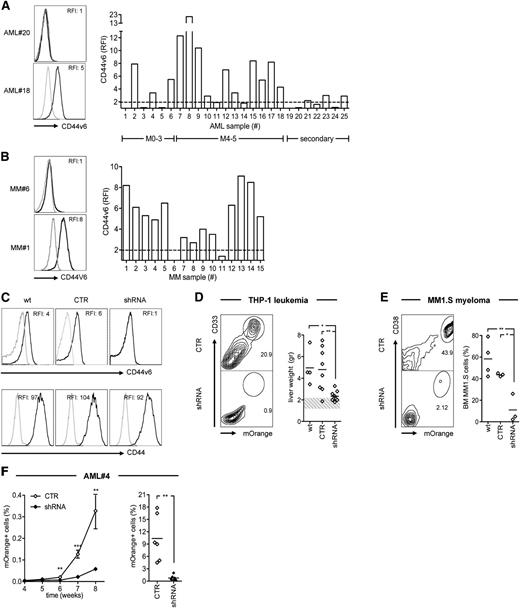

For verifying the clinical relevance of CD44v6 as a target, we analyzed its surface expression on a panel of leukemic blasts isolated from AML patients (supplemental Table 1) and of malignant plasma cells from MM patients (supplemental Table 2). CD44v6 was expressed at variable levels in 16 of 25 (64%) AML cases belonging to different French-American-British subtypes and World Health Organization categories (Figure 1A) and in 13 of 15 (87%) MM cases at different stages according to the Durie-Salmon classification or the International Staging System (Figure 1B). Interestingly, primary circulating leukemic blasts significantly upregulated CD44v6 when cultured ex vivo with BM-derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), whereas primary malignant plasma cells did not (supplemental Figure 1A), suggesting regulated expression by disease-specific signals within the tumor microenvironment. CD44v6 was also widely expressed on AML and MM cell lines (supplemental Figure 1B).

Role of CD44v6 in AML and MM cell growth in vivo. (A) Leukemic blasts from AML patients (n = 25, see supplemental Table 1) and (B) malignant plasma cells from MM patients (n = 15, see supplemental Table 2) were analyzed by FACS. Leukemic blasts were grouped according to their French-American-British subtype (M0-M3, n = 6; M4-M5, n = 12; secondary AML, n = 7). Left: CD44v6 expression from representative cases. Right: CD44v6 RFI (see “Material and methods”) from each case. The dashed line represents the threshold arbitrarily defining CD44v6 positivity (RFI = 2). (C) Tumor cells were transduced with an LV encoding for a CD44v6-specific shRNA sequence (see supplemental Figure 1C) and tested for selective silencing by FACS after gating for the mOrange marker gene (see “Material and methods”). Upper panels: CD44v6 expression on wild-type THP-1 leukemia cells (wt) or on THP-1 cells transduced with the shRNA or with a control vector (CTR). Lower panels: CD44 expression in the same conditions. (D) THP-1 cells and (E) MM1.S myeloma cells were transduced with the shRNA or with the CTR vector and infused intravenously in NSG mice. A group of control mice were infused with wt tumor cells. After 4 weeks, mice were sacrificed and analyzed for engraftment in different organs. Left: percentages of CD33+/mOrange+ THP-1 cells in the liver or of CD38+/mOrange+ MM1.S cells in the BM of representative mice. Right: weights of THP1-infiltrated livers or percentages of BM-engrafted MM1.S cells from each mouse. The dashed band represents the normal range of mouse liver weight. Results from a 1-way ANOVA are shown when statistically significant (*P < .05; **P < .01). (F) Leukemic blasts from patient AML#4 (see supplemental Table 1) were transduced with the shRNA or with the CTR vector, infused intravenously in NSG mice, and followed in the peripheral circulation by FACS. Left: percentages of circulating mOrange+ leukemic blasts (mean ± SD from n = 5 mice per condition) at different time points. Right: percentages of mOrange+ leukemic blasts in the BM from each mouse at 8 weeks. Results from unpaired Student t test are shown for each time point (**P < .01; ***P < .001).

Role of CD44v6 in AML and MM cell growth in vivo. (A) Leukemic blasts from AML patients (n = 25, see supplemental Table 1) and (B) malignant plasma cells from MM patients (n = 15, see supplemental Table 2) were analyzed by FACS. Leukemic blasts were grouped according to their French-American-British subtype (M0-M3, n = 6; M4-M5, n = 12; secondary AML, n = 7). Left: CD44v6 expression from representative cases. Right: CD44v6 RFI (see “Material and methods”) from each case. The dashed line represents the threshold arbitrarily defining CD44v6 positivity (RFI = 2). (C) Tumor cells were transduced with an LV encoding for a CD44v6-specific shRNA sequence (see supplemental Figure 1C) and tested for selective silencing by FACS after gating for the mOrange marker gene (see “Material and methods”). Upper panels: CD44v6 expression on wild-type THP-1 leukemia cells (wt) or on THP-1 cells transduced with the shRNA or with a control vector (CTR). Lower panels: CD44 expression in the same conditions. (D) THP-1 cells and (E) MM1.S myeloma cells were transduced with the shRNA or with the CTR vector and infused intravenously in NSG mice. A group of control mice were infused with wt tumor cells. After 4 weeks, mice were sacrificed and analyzed for engraftment in different organs. Left: percentages of CD33+/mOrange+ THP-1 cells in the liver or of CD38+/mOrange+ MM1.S cells in the BM of representative mice. Right: weights of THP1-infiltrated livers or percentages of BM-engrafted MM1.S cells from each mouse. The dashed band represents the normal range of mouse liver weight. Results from a 1-way ANOVA are shown when statistically significant (*P < .05; **P < .01). (F) Leukemic blasts from patient AML#4 (see supplemental Table 1) were transduced with the shRNA or with the CTR vector, infused intravenously in NSG mice, and followed in the peripheral circulation by FACS. Left: percentages of circulating mOrange+ leukemic blasts (mean ± SD from n = 5 mice per condition) at different time points. Right: percentages of mOrange+ leukemic blasts in the BM from each mouse at 8 weeks. Results from unpaired Student t test are shown for each time point (**P < .01; ***P < .001).

For challenging the role of CD44v6 in tumor growth, we silenced its expression in THP-1 leukemia cells and in MM1.S myeloma cells by shRNA interference with an LV optimized for hematopoietic expression (supplemental Figure 1C). Silencing was selective for CD44v6, because CD44 levels were similar to cells transduced with a control LV (Figure 1C) and did not result in reduced proliferation in vitro (supplemental Figure 1D). In agreement with the tendency of M4 leukemia to form extramedullary tumors, after intravenous infusion in NSG mice, wild-type THP-1 cells formed multiple nodules in the liver. Alternatively, CD44v6-silenced cells had a significantly lower potential to form liver nodules (Figure 1D). By analogy, CD44v6 silencing also interfered with the ability of intravenously-infused MM1.S cells to engraft in the BM of NSG mice (Figure 1E). Finally, we silenced CD44v6 expression in primary leukemic blasts and found a significantly reduced capacity to initiate leukemia in NSG mice (Figure 1F).

T cells activated with CD3/CD28 beads and transduced with a newly designed CD44v6.CAR28z mediate potent and specific antileukemia and antimyeloma effects

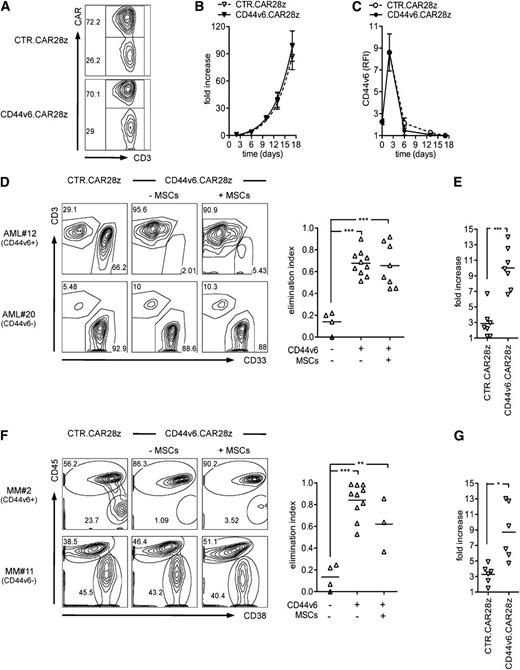

After verifying the role of CD44v6 in tumor growth in vivo, we constructed a CAR using the scFv from a humanized anti-CD44v6 mAb in frame with the TCR-ζ chain and CD28. The CD44v6.CAR28z was cloned into an RV for transducing primary T cells. For transduction, T cells were activated with CD3/CD28-beads plus IL-7/IL-15.42,43 Mean transduction efficiency was 72.0 ± 21.6% standard deviation (SD) (Figure 2A). Importantly, the expansion kinetics of CD44v6.CAR28z+ T cells was similar to that of control CAR-transduced T cells (CTR.CAR28z+, Figure 2B), ruling out potential “fratricide” caused by CD44v6 expression in T cells. CD44v6 was indeed upregulated after activation, but only transiently, and before the CAR was detectable on the T-cell surface (Figure 2C). The resulting population had a preserved CD4/CD8 ratio and was enriched for central-memory T cells expressing IL-7Rα and CXCR4 (supplemental Figure 2), indicating the potential for homing to the BM.44

In vitro antitumor effects by CD44v6-targeted T cells. T cells were activated with CD3/CD28 beads, transduced with an RV encoding for the CD44v6-specific CAR (CD44v6.CAR28z) or a control CAR (CTR.CAR28z), and cultured with IL-7/IL-15. (A) Percentages of CAR+ T cells by FACS in a representative donor at 14 days. (B) Expansion of CAR+ T cells measured as fold increase (see “Material and methods”) at different time points after bead activation (mean ± SD from n = 5 donors). (C) CD44v6 expression (RFI, see “Material and methods”) on T cells at the respective time points (mean ± SD from n = 3 donors). (D) CD44v6.CAR28z+ or CTR.CAR28z+ T cells from healthy donors (n = 2) were cultured with CD44v6+ or CD44v6− leukemic blasts from AML patients (n = 7) in the presence (+) or absence (−) of MSCs (E:T ratio = 1:5/10). After 4 days, residual leukemic blasts (CD33+/CD3–) and T lymphocytes (CD33–/CD3+) were counted and analyzed by FACS. Left: results from a representative experiment. Right: antileukemia effects by CD44v6.CAR28z+ T cells measured as the elimination index (see “Material and methods”) for each combination. (E) Expansion of CD44v6.CAR28z+ or CTR.CAR28z+ T cells in response to CD44v6+ leukemic blasts measured as fold increase (see “Material and methods”) at the end of culturing. (F) The same experimental setting was used for CD44v6+ or CD44v6– malignant plasma cells from MM patients (n = 6). Malignant plasma cells were identified as CD38+/CD45–. Left: results from a representative experiment. Right: antimyeloma effects by CD44v6.CAR28z+ T cells measured as the elimination index for each combination. (G) Expansion of CD44v6.CAR28z+ or CTR.CAR28z+ T cells in response to CD44v6+ malignant plasma cells measured as fold increase at the end of the culture. Results from a paired Student t test or 1-way ANOVA are shown when statistically significant (*P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001).

In vitro antitumor effects by CD44v6-targeted T cells. T cells were activated with CD3/CD28 beads, transduced with an RV encoding for the CD44v6-specific CAR (CD44v6.CAR28z) or a control CAR (CTR.CAR28z), and cultured with IL-7/IL-15. (A) Percentages of CAR+ T cells by FACS in a representative donor at 14 days. (B) Expansion of CAR+ T cells measured as fold increase (see “Material and methods”) at different time points after bead activation (mean ± SD from n = 5 donors). (C) CD44v6 expression (RFI, see “Material and methods”) on T cells at the respective time points (mean ± SD from n = 3 donors). (D) CD44v6.CAR28z+ or CTR.CAR28z+ T cells from healthy donors (n = 2) were cultured with CD44v6+ or CD44v6− leukemic blasts from AML patients (n = 7) in the presence (+) or absence (−) of MSCs (E:T ratio = 1:5/10). After 4 days, residual leukemic blasts (CD33+/CD3–) and T lymphocytes (CD33–/CD3+) were counted and analyzed by FACS. Left: results from a representative experiment. Right: antileukemia effects by CD44v6.CAR28z+ T cells measured as the elimination index (see “Material and methods”) for each combination. (E) Expansion of CD44v6.CAR28z+ or CTR.CAR28z+ T cells in response to CD44v6+ leukemic blasts measured as fold increase (see “Material and methods”) at the end of culturing. (F) The same experimental setting was used for CD44v6+ or CD44v6– malignant plasma cells from MM patients (n = 6). Malignant plasma cells were identified as CD38+/CD45–. Left: results from a representative experiment. Right: antimyeloma effects by CD44v6.CAR28z+ T cells measured as the elimination index for each combination. (G) Expansion of CD44v6.CAR28z+ or CTR.CAR28z+ T cells in response to CD44v6+ malignant plasma cells measured as fold increase at the end of the culture. Results from a paired Student t test or 1-way ANOVA are shown when statistically significant (*P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001).

In chromium-release assays, CD44v6.CAR28z+, but not CTR.CAR28z+, T cells lysed CD44v6+ primary leukemic blasts (supplemental Figure 3A). In a more physiological system, when cocultured with an excess of target cells, CD44v6.CAR28z+ T cells efficiently eliminated CD44v6+, but not CD44v6–, tumor cells (supplemental Figure 3B), notably including primary leukemic blasts (Figure 2D) and malignant plasma cells (Figure 2F). Interestingly, despite their immunosuppressive functions (supplemental Figure 3C), MSCs did not interfere with the antitumor potential of CD44v6.CAR28z+ T cells. Antigen recognition associated with vigorous CD44v6-specific T-cell expansion, ruling out secondary fratricide on execution of effector functions (Figure 2E,G).

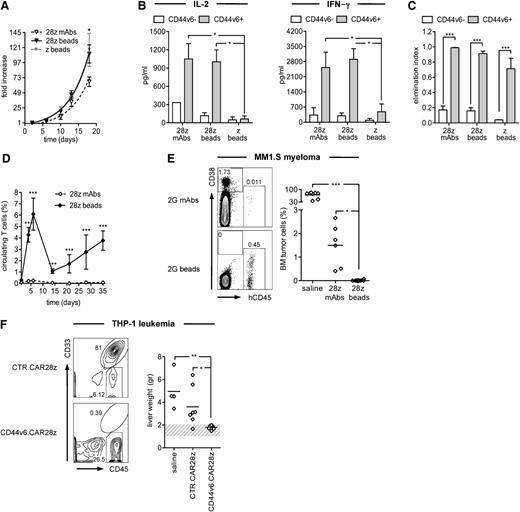

For verifying the influence of the type of in vitro activation on antitumor potential, we compared CD44v6.CAR28z+ T cells activated with beads or soluble mAbs. In vitro, bead activation prompted higher expansion rates than mAbs (Figure 3A) but similar levels of CD44v6-specific cytokine production (Figure 3B) and comparable antitumor effects (Figure 3C). Conversely, regardless of the activation type, T cells carrying a CAR lacking CD28 (CD44v6.CARz) failed to produce cytokines, indicating that the costimulatory domain was absolutely required for cytokine production. In NSG mice challenged with MM1.S cells, bead activation resulted in superior expansion and persistence of CD44v6.CAR28z+ T cells (Figure 3D), which consequently mediated superior antimyeloma effects compared with CD44v6.CAR28z+ T cells activated with mAbs (Figure 3E). On the basis of these results, bead activation was used for all subsequent experiments, including the demonstration of potent and specific antileukemia effects in NSG mice challenged with THP-1 cells and treated with CD44v6.CAR28z+ T cells (Figure 3F).

In vivo antitumor effects by CD44v6-targeted T cells. T cells were RV-transduced with the CD44v6.CAR28z after activation with CD3/CD28 beads (28z beads) or with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 mAbs (28z mAbs). Bead-activated T cells were also transduced with a CD44v6.CARz (z beads). CAR-redirected T cells were compared in vitro in terms of (A) expansion, measured as fold increase at different time points (mean ± SD from n = 5 donors); (B) release of IL-2 and interferon-γ upon recognition of CD44v6+ (n = 4) or CD44v6– (n = 3) primary leukemic blasts (concentration, mean ± SD); (C) antileukemia and antimyeloma activity, measured as the elimination index (see “Material and methods”) of CD44v6+ AML (n = 3) and MM (n = 2) cell lines or CD44v6– AML (n = 2) and MM (n = 2) cell lines. Results from a 2-way ANOVA are shown when statistically significant (*P < .05; ***P < .001). (D) NSG mice were infused with MM1.S myeloma cells and, after 3 days, treated with CD44v6.CAR28z+ T cells activated with beads (n = 14 mice) or mAbs (n = 6). The percentages of circulating T cells were analyzed at different time points by FACS (mean ± SD). Results from an unpaired Student t test are shown for each time point (***P < .001). (E) Left: percentages of MM1.S myeloma cells (CD38+/CD45–) and T cells (CD38dim/CD45+) in the BM of representative mice at 5 weeks. Right: percentages of MM1.S myeloma cells in the BM of each mouse. Results from a 1-way ANOVA are shown when statistically significant (*P < .05; ***P < .001). (F) NSG mice were infused with THP-1 leukemia cells and, after 3 days, treated with bead-activated CD44v6.CAR28z+ T cells (n = 10 mice) or with CTR.CAR28z+ T cells (n = 7). A group of control mice received saline only (n = 4). Left: percentages of THP-1 leukemia cells (CD33+/CD45+) and T cells (CD33–/CD45+) in the liver of representative mice at 4 weeks. Right: weights of THP1-infiltrated livers from each mouse. Results from a 1-way ANOVA are shown when statistically significant (*P < .05; **P < .01).

In vivo antitumor effects by CD44v6-targeted T cells. T cells were RV-transduced with the CD44v6.CAR28z after activation with CD3/CD28 beads (28z beads) or with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 mAbs (28z mAbs). Bead-activated T cells were also transduced with a CD44v6.CARz (z beads). CAR-redirected T cells were compared in vitro in terms of (A) expansion, measured as fold increase at different time points (mean ± SD from n = 5 donors); (B) release of IL-2 and interferon-γ upon recognition of CD44v6+ (n = 4) or CD44v6– (n = 3) primary leukemic blasts (concentration, mean ± SD); (C) antileukemia and antimyeloma activity, measured as the elimination index (see “Material and methods”) of CD44v6+ AML (n = 3) and MM (n = 2) cell lines or CD44v6– AML (n = 2) and MM (n = 2) cell lines. Results from a 2-way ANOVA are shown when statistically significant (*P < .05; ***P < .001). (D) NSG mice were infused with MM1.S myeloma cells and, after 3 days, treated with CD44v6.CAR28z+ T cells activated with beads (n = 14 mice) or mAbs (n = 6). The percentages of circulating T cells were analyzed at different time points by FACS (mean ± SD). Results from an unpaired Student t test are shown for each time point (***P < .001). (E) Left: percentages of MM1.S myeloma cells (CD38+/CD45–) and T cells (CD38dim/CD45+) in the BM of representative mice at 5 weeks. Right: percentages of MM1.S myeloma cells in the BM of each mouse. Results from a 1-way ANOVA are shown when statistically significant (*P < .05; ***P < .001). (F) NSG mice were infused with THP-1 leukemia cells and, after 3 days, treated with bead-activated CD44v6.CAR28z+ T cells (n = 10 mice) or with CTR.CAR28z+ T cells (n = 7). A group of control mice received saline only (n = 4). Left: percentages of THP-1 leukemia cells (CD33+/CD45+) and T cells (CD33–/CD45+) in the liver of representative mice at 4 weeks. Right: weights of THP1-infiltrated livers from each mouse. Results from a 1-way ANOVA are shown when statistically significant (*P < .05; **P < .01).

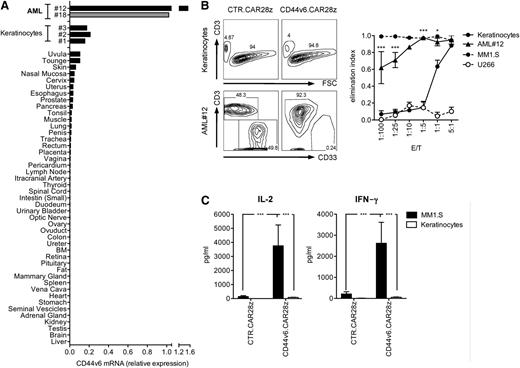

CD44v6.CAR28z+ T cells spare keratinocytes and HSCs but cause selective monocytopenia in vivo

For predicting potential off-tumor toxicities of CD44v6.CAR28z+ T cells, we analyzed CD44v6 expression by real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) on a large panel of normal tissues. Detectable CD44v6 expression was found in only the skin and oral mucosa, albeit at considerably lower levels than in primary leukemic blasts (Figure 4A). Low-level CD44v6 expression by RT-qPCR was confirmed on primary cultured keratinocytes and was evident on basal-layer keratinocytes by skin immunohistochemistry (Figure 5C). We therefore specifically addressed whether primary keratinocytes could be recognized in coculture experiments. Strikingly, at the E:T ratios allowing the potent antitumor effects of CD44v6-targeted T cells, keratinocytes were not killed (Figure 4B) and there was no cytokine production (Figure 4C).

Safety profile of CD44v6-targeted T cells toward nonhematopoietic cells. (A) CD44v6 expression in primary leukemic blasts, cultured primary keratinocytes, and a panel of normal tissues was analyzed by RT-qPCR. CD44v6 expression from a CD44v6+ AML sample was used as a reference (gray). (B) CD44v6.CAR28z+ or CTR.CAR28z+ T cells from healthy donors (n = 3) were cultured with primary keratinocytes (n = 6), primary leukemic blasts from AML#12, CD44v6+ MM1.S, or CD44v6– U266 myeloma cells at different E:T ratios. After 4 days, residual cells were counted and analyzed by FACS. Left: results from a representative experiment. Right: elimination index by CD44v6.CAR28z+ T lymphocytes at each E:T ratio (see “Material and methods”). Results from a 1-way ANOVA test comparing the elimination of leukemic blasts and keratinocytes are shown (*P < .05; ***P < .001). (C) CAR+ T cells were analyzed for IL-2 and interferon-γ production upon coculture with MM1.S or keratinocytes (concentration, mean ± SD). Results from a Student t test are shown when statistically significant (***P < .001).

Safety profile of CD44v6-targeted T cells toward nonhematopoietic cells. (A) CD44v6 expression in primary leukemic blasts, cultured primary keratinocytes, and a panel of normal tissues was analyzed by RT-qPCR. CD44v6 expression from a CD44v6+ AML sample was used as a reference (gray). (B) CD44v6.CAR28z+ or CTR.CAR28z+ T cells from healthy donors (n = 3) were cultured with primary keratinocytes (n = 6), primary leukemic blasts from AML#12, CD44v6+ MM1.S, or CD44v6– U266 myeloma cells at different E:T ratios. After 4 days, residual cells were counted and analyzed by FACS. Left: results from a representative experiment. Right: elimination index by CD44v6.CAR28z+ T lymphocytes at each E:T ratio (see “Material and methods”). Results from a 1-way ANOVA test comparing the elimination of leukemic blasts and keratinocytes are shown (*P < .05; ***P < .001). (C) CAR+ T cells were analyzed for IL-2 and interferon-γ production upon coculture with MM1.S or keratinocytes (concentration, mean ± SD). Results from a Student t test are shown when statistically significant (***P < .001).

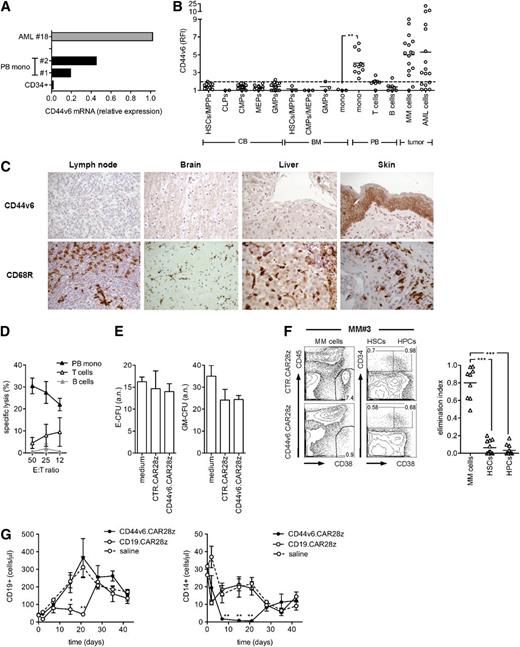

Safety profile of CD44v6-targeted T cells toward hematopoietic cells. (A) CD44v6 messenger RNA (mRNA) expression in primary leukemic blasts, peripheral blood (PB)–derived CD14+ monocytes (mono), and CB-derived CD34+ cells was analyzed by qPCR. (B) CD44v6 expression on CB HSCs and progenitors; BM HSCs, progenitors, and monocytes; and PB monocytes, T cells, and B cells was analyzed by FACS and expressed as RFI. HSCs and progenitors were identified as follows: HSCs/multipotent progenitors (MPPs), CD34+/CD38–/CD45RA–; common lymphoid progenitors (CLPs), CD34+/CD10+; common myeloid progenitors (CMPs), CD34+/CD38+/CD123+/CD45RA–; granulocyte/monocyte progenitors (GMPs), CD34+/CD38+/CD123+/CD45RA+; and myeloid erythroid progenitors (MEPs), CD34+/CD38+/CD123–/CD45RA–. CD44v6 expression on tumor cells from AML and MM patients is shown for comparison. The dashed line represents the threshold arbitrarily defining positive expression (RFI = 2). (C) Human lymph node, brain, liver, and skin sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin were analyzed by immunohistochemistry for expression of CD44v6 and the CD68R macrophage marker. (D) CD44v6.CAR28z+ and CTR.CAR28z+ T cells were tested in chromium-release assays against circulating monocytes, T cells, and B cells. Specific lysis is shown at different E:T ratios (mean ± SD from n = 4 donors). (E) CB CD34-selected cells were incubated for 4 hours with autologous CD44v6.CAR28z+ or CTR.CAR28z+ T cells, or medium alone, before being assayed in a standard colony-forming assay (see “Material and methods”). Absolute numbers (a.n.) of erythroid- (E-CFU) and granulocyte/monocyte-colony forming units (GM-CFU) at 14 days (mean ± SD from n = 3 CB units). (F) CD44v6.CAR28z+ or CTR.CAR28z+ T cells from healthy donors (n = 2) were cultured with whole BM mononuclear fractions from MM patients (n = 6). After 4 days, residual malignant plasma cells (CD38+/CD45–), HSCs (CD34+/CD38–), and hematopoietic progenitor cells (HPCs, CD34+/CD38+) were counted and analyzed by FACS. Left: results from a representative experiment. Right: antimyeloma effects by CD44v6.CAR28z+ T cells measured as the elimination index for each combination (see “Material and methods”). Results from a 1-way ANOVA are shown when statistically significant (***P < .001). (G) After irradiation, NSG-3GS mice were infused with CB CD34-selected cells and, after 4 weeks, treated with autologous CD44v6.CAR28z+ T cells or CD19.CAR28z+ T cells (n = 4 mice/group) or saline (n = 3). Absolute numbers of CD19+ cells (left panel) and CD14+ cells (right panel) in the peripheral blood of mice at different time points after T-cell infusion. Results from a 1-way ANOVA are shown when statistically significant (*P < .05; **P < .01).

Safety profile of CD44v6-targeted T cells toward hematopoietic cells. (A) CD44v6 messenger RNA (mRNA) expression in primary leukemic blasts, peripheral blood (PB)–derived CD14+ monocytes (mono), and CB-derived CD34+ cells was analyzed by qPCR. (B) CD44v6 expression on CB HSCs and progenitors; BM HSCs, progenitors, and monocytes; and PB monocytes, T cells, and B cells was analyzed by FACS and expressed as RFI. HSCs and progenitors were identified as follows: HSCs/multipotent progenitors (MPPs), CD34+/CD38–/CD45RA–; common lymphoid progenitors (CLPs), CD34+/CD10+; common myeloid progenitors (CMPs), CD34+/CD38+/CD123+/CD45RA–; granulocyte/monocyte progenitors (GMPs), CD34+/CD38+/CD123+/CD45RA+; and myeloid erythroid progenitors (MEPs), CD34+/CD38+/CD123–/CD45RA–. CD44v6 expression on tumor cells from AML and MM patients is shown for comparison. The dashed line represents the threshold arbitrarily defining positive expression (RFI = 2). (C) Human lymph node, brain, liver, and skin sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin were analyzed by immunohistochemistry for expression of CD44v6 and the CD68R macrophage marker. (D) CD44v6.CAR28z+ and CTR.CAR28z+ T cells were tested in chromium-release assays against circulating monocytes, T cells, and B cells. Specific lysis is shown at different E:T ratios (mean ± SD from n = 4 donors). (E) CB CD34-selected cells were incubated for 4 hours with autologous CD44v6.CAR28z+ or CTR.CAR28z+ T cells, or medium alone, before being assayed in a standard colony-forming assay (see “Material and methods”). Absolute numbers (a.n.) of erythroid- (E-CFU) and granulocyte/monocyte-colony forming units (GM-CFU) at 14 days (mean ± SD from n = 3 CB units). (F) CD44v6.CAR28z+ or CTR.CAR28z+ T cells from healthy donors (n = 2) were cultured with whole BM mononuclear fractions from MM patients (n = 6). After 4 days, residual malignant plasma cells (CD38+/CD45–), HSCs (CD34+/CD38–), and hematopoietic progenitor cells (HPCs, CD34+/CD38+) were counted and analyzed by FACS. Left: results from a representative experiment. Right: antimyeloma effects by CD44v6.CAR28z+ T cells measured as the elimination index for each combination (see “Material and methods”). Results from a 1-way ANOVA are shown when statistically significant (***P < .001). (G) After irradiation, NSG-3GS mice were infused with CB CD34-selected cells and, after 4 weeks, treated with autologous CD44v6.CAR28z+ T cells or CD19.CAR28z+ T cells (n = 4 mice/group) or saline (n = 3). Absolute numbers of CD19+ cells (left panel) and CD14+ cells (right panel) in the peripheral blood of mice at different time points after T-cell infusion. Results from a 1-way ANOVA are shown when statistically significant (*P < .05; **P < .01).

Focusing on the potential hematologic toxicities of CD44v6.CAR28z+ T cells, we next analyzed CD44v6 expression on cells at different stages of hematopoietic differentiation. CD44v6 was completely absent on HSCs, progenitors, and resting T and B lymphocytes, but it was present on circulating monocytes (Figure 5A-B). Interestingly, both BM monocytes and tissue-resident monocyte-derived cells, like lymph node macrophages, brain microglia, liver Kupffer cells, and skin macrophages, did not express CD44v6, suggesting a low risk for bystander toxicity against these tissues (Figure 5B-C). In agreement with the CD44v6 expression pattern, CD44v6.CAR28z+ T cells readily recognized circulating monocytes (Figure 5D), but not resting T and B cells, or restimulated virus-specific T cells (supplemental Figure 4).

Finally, for excluding that CD44v6.CAR28z+ T cells could damage the hematopoietic potential of HSCs, we ruled out their interference with erythroid and granulocyte/monocyte clonogenicity in vitro (Figure 5E) and successfully challenged their capacity of selectively eliminating tumor cells while sparing HSCs and progenitors in coculture experiments with whole BM from MM patients (Figure 5F). Accordingly, the only hematologic toxicity observed after infusing CD44v6.CAR28z+ T cells in human hematochimeric NSG-3GS mice, which were chosen because of their enhanced monocyte reconstitution compared with NSG mice, was selective monocytopenia. However, this was reversible upon contraction of T cells in vivo (Figure 5G).

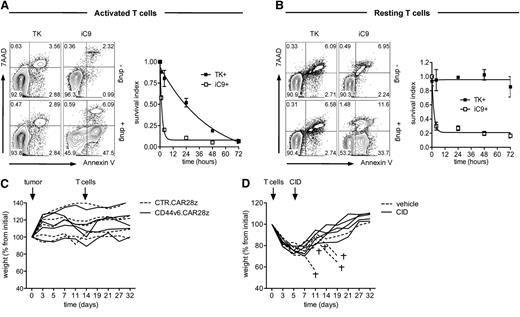

Pharmacologic ablation of CD44v6.CAR28z+ T cells expressing a suicide gene rescues from hyperacute xenogeneic GVHD

For enabling conditional ablation of CD44v6.CAR28z+ T cells, we cloned the CAR in a third-generation LV with a PGK bidirectional promoter driving the coexpression of the suicide gene TK (supplemental Figure 5A). Transduction with the LV conferred selective and dose-dependent susceptibility of CD44v6.CAR8z+ T cells to GCV-induced apoptosis (supplemental Figure 5B). Importantly, selective ablation of T cells was confirmed after CD44v6-specific stimulation (supplemental Figure 5C). To overcome the hurdle of TK immunogenicity, we alternatively explored the nonimmunogenic suicide gene iC9. After transduction with a LV coexpressing iC9 (supplemental Figure 5D), CD44v6.CAR28z+ T cells were efficiently ablated by in vitro exposure to a clinical-grade CID in a dose-dependent manner (supplemental Figure 5E). Interestingly, when comparing the kinetics of the 2 suicide genes, iC9 was significantly faster than TK (Figure 6A) and also ablated resting T cells (Figure 6B). Infusing LV-transduced CD44v6.CAR28z+ T cells into nonirradiated NSG mice bearing a CD44v6+ tumor was well tolerated (Figure 6C). Previous irradiation, however, resulted in hyperacute xenogeneic GVHD characterized by sudden weight loss and precocious death (Figure 6D). Coexpressing iC9 enabled fast and efficient in vivo ablation of CD44v6.CAR28z+ T cells by a single administration of the CID (not shown) and complete rescue of severely sick mice (weight loss >20%).

Pharmacologic ablation of CD44v6.CAR28z+ T cells coexpressing a suicide gene and rescue from hyperacute GVHD. (A) T cells were transduced with a bidirectional LV encoding for the CD44v6.CAR28z and either the thymidine kinase (TK) or the inducible caspase 9 (iC9) suicide genes (see supplemental Figure 5). At different time points after polyclonal activation and exposure to 1 μM GCV or 10 nM AP1903 (see “Material and methods”), CAR+ T cells were analyzed by FACS after annexin V/7AAD staining. Left: results from a representative experiment at 4 hours (annexin V–/7AAD–, living cells; annexin V+/7AAD–, early apoptotic cells; annexin V+/7AAD+, late apoptotic cells). Right: pharmacologic ablation of CAR+ T cells measured as survival index (see “Material and methods,” mean ± SD from n = 3 donors). (B) The same experimental setting was used for resting, bidirectional LV-transduced T cells (mean ± SD from n = 3 donors). (C) NSG mice were infused with leukemic blasts from patient AML#4 (tumor, arrow) and, when leukemic blasts were detectable in the peripheral blood, treated with either bidirectional LV-transduced CD44v6.CAR28z+ or CTR.CAR28z+ T cells (T cells, arrow). The weight of each mouse at different time points is shown as percentage from initial. (D) Irradiated NSG mice were infused with FACS-sorted CD44v6.CAR28z+ T cells co-expressing iC9 (T cells, arrow) and, after losing >20% of their initial weight, received a single dose of the chemical inducer of dimerization (CID, arrow) or vehicle only. The daggers indicate death of mice from hyperacute GVHD.

Pharmacologic ablation of CD44v6.CAR28z+ T cells coexpressing a suicide gene and rescue from hyperacute GVHD. (A) T cells were transduced with a bidirectional LV encoding for the CD44v6.CAR28z and either the thymidine kinase (TK) or the inducible caspase 9 (iC9) suicide genes (see supplemental Figure 5). At different time points after polyclonal activation and exposure to 1 μM GCV or 10 nM AP1903 (see “Material and methods”), CAR+ T cells were analyzed by FACS after annexin V/7AAD staining. Left: results from a representative experiment at 4 hours (annexin V–/7AAD–, living cells; annexin V+/7AAD–, early apoptotic cells; annexin V+/7AAD+, late apoptotic cells). Right: pharmacologic ablation of CAR+ T cells measured as survival index (see “Material and methods,” mean ± SD from n = 3 donors). (B) The same experimental setting was used for resting, bidirectional LV-transduced T cells (mean ± SD from n = 3 donors). (C) NSG mice were infused with leukemic blasts from patient AML#4 (tumor, arrow) and, when leukemic blasts were detectable in the peripheral blood, treated with either bidirectional LV-transduced CD44v6.CAR28z+ or CTR.CAR28z+ T cells (T cells, arrow). The weight of each mouse at different time points is shown as percentage from initial. (D) Irradiated NSG mice were infused with FACS-sorted CD44v6.CAR28z+ T cells co-expressing iC9 (T cells, arrow) and, after losing >20% of their initial weight, received a single dose of the chemical inducer of dimerization (CID, arrow) or vehicle only. The daggers indicate death of mice from hyperacute GVHD.

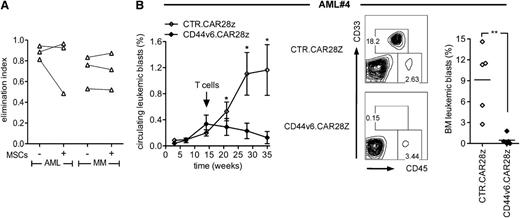

CD44v6.CAR28z+ T cells coexpressing a suicide gene eradicate autologous leukemia in vivo

Finally, for validating our strategy in a clinically relevant setting, we proved the feasibility of generating sufficient numbers of bidirectional LV-transduced T cells for in vivo testing against the autologous tumor (supplemental Figure 6A-C). In vitro, bidirectional LV-transduced CD44v6.CAR28z+ T cells from patients were specifically effective against autologous primary leukemic blasts and malignant plasma cells and were resistant to the immunosuppressive effects of MSCs (Figure 7A). Interestingly, when comparing bidirectional LV-transduced T cells with T cells transduced with the original RV, we found similar levels of transgene expression and equal antitumor potential (supplemental Figure 6D-E), suggesting that, on bead activation, LV may not be intrinsically superior to RV for genetically redirecting T cells. NSG mice previously infused with primary leukemic blasts were therefore treated with a single infusion of bidirectional LV-transduced CD44v6.CAR28z+ or CTR.CAR28z+ T cells from the same patient. Although control mice had increasing percentages of circulating leukemic blasts over time, mice receiving CD44v6.CAR28z+ T cells had progressive leukemia disappearance (Figure 7B) and, at sacrifice, were completely cleared from tumor cells in the BM.

In vivo antileukemia effects by CD44v6.CAR28z+ T cells coexpressing a suicide gene. (A) T cells from AML (n = 3) and MM patients (n = 3) were transduced with the bidirectional LV and cultured with autologous leukemic blasts (left) or malignant plasma cells (right) in the presence (+) or absence (−) of MSCs. After 4 days, residual tumor cells were counted and analyzed by FACS. Antileukemia and antimyeloma effects by CD44v6.CAR28z+ T cells were measured as the elimination index for each case. (B) At the time of AML#4 leukemia appearance in the peripheral blood (arrow), NSG mice were treated with either bidirectional LV-transduced autologous CD44v6.CAR28z+ or with CTR.CAR28z+ T cells (n = 5 mice per group). Left: percentage of circulating CD33+/CD45dim leukemic blasts at different time points by FACS (mean ± SD). Middle: percentages of BM leukemic blasts from representative mice. Right: percentages of BM leukemic blasts from each mouse at 5 weeks. Results from an unpaired Student t test are shown for each time point (**P < .01).

In vivo antileukemia effects by CD44v6.CAR28z+ T cells coexpressing a suicide gene. (A) T cells from AML (n = 3) and MM patients (n = 3) were transduced with the bidirectional LV and cultured with autologous leukemic blasts (left) or malignant plasma cells (right) in the presence (+) or absence (−) of MSCs. After 4 days, residual tumor cells were counted and analyzed by FACS. Antileukemia and antimyeloma effects by CD44v6.CAR28z+ T cells were measured as the elimination index for each case. (B) At the time of AML#4 leukemia appearance in the peripheral blood (arrow), NSG mice were treated with either bidirectional LV-transduced autologous CD44v6.CAR28z+ or with CTR.CAR28z+ T cells (n = 5 mice per group). Left: percentage of circulating CD33+/CD45dim leukemic blasts at different time points by FACS (mean ± SD). Middle: percentages of BM leukemic blasts from representative mice. Right: percentages of BM leukemic blasts from each mouse at 5 weeks. Results from an unpaired Student t test are shown for each time point (**P < .01).

Discussion

In this study, we have preclinically validated a strategy for the safe and effective targeting of the tumor-promoting antigen CD44v6 with CAR-redirected T cells for the combined treatment of AML and MM. There is clinical evidence that immunotherapeutic approaches targeted to antigens that are irrelevant for tumor growth may favor the emergence of antigen loss variants as a result of Darwinian selection, including HLA-less AML clones after HSC transplantation45 and CD19-less ALL clones after CAR T-cell therapy.15 In this work, we have found that despite normal rates of in vitro proliferation, CD44v6-silenced AML and MM cells are severely impaired in their capacity to engraft in immunocompromised mice and, similarly, that CD44v6-silenced primary leukemic blasts fail to initiate leukemia in vivo. These observations extend the findings by John Dick and colleagues on the key role of CD44 in promoting the homing of AML stem and initiating cells to the BM, suggesting that the isoform variant 6 may be selectively implicated. More importantly, they provide a rationale for targeting an AML and MM antigen that can only be lost at the expenses of reduced tumor growth in vivo, therefore circumventing potential immune escape mechanisms.

We previously showed that the type of activation and the culture conditions for in vitro transduction of T cells greatly contribute to their overall fitness. Activation with CD3/CD28 beads42 and culture with IL-7/IL-15,46 instead of activation with OKT3 and IL-2, allow genetically modifying T cells with enhanced persistence and superior antileukemia activity in vivo.43 More recently, we have found that these properties are caused by the preferential transduction of putative stem memory T cells.47 In this work, we have combined bead activation and IL-7/IL-15 for effective CD44v6-specific CAR redirection of T cells from AML and MM patients. In immunocompromised mice, the kinetics of CD44v6-targeted T cells showed an early expansion phase and persistence at low levels until sacrifice. In the most stringent and clinically relevant setting of autologous ACT with CD44v6-targeted T cells, this resulted in impressive antitumor effects, as observed in the xenograft model with primary leukemic blasts. Interestingly, bead activation and IL-7/IL-15 were required for maximal antitumor activity, suggesting that optimal “exocostimulation” is a key determinant of antitumor potency, as observed in recent clinical trials.12,15,16

In clinical trials, tumor responses by CAR-redirected T cells were associated with toxicities deriving from off-tumor expression of the target, including a case of fatal lung toxicity when using HER2-targeted T cells48 and the frequent observation of prolonged B-cell depletion when using CD19-targeted T cells.12-14 Despite promising activity against epithelial tumors, the administration of the CD44v6-specific mAb (bivatuzumab) used for deriving our CAR scFv showed reversible myelosuppression and mucositis when conjugated with radioisotopes,49 and showed skin toxicity, including a fatal case, when conjugated with the potent cytotoxic drug mertansine.50 By using FACS on different cells of hematopoietic origin and by using RT-qPCR on a large panel of normal tissues, we expectedly found restricted CD44v6 expression on monocytes and keratinocytes, albeit at significantly lower levels compared with tumor cells, and we confirmed previous reports32 showing lack of target expression on HSCs and progenitor cells. Accordingly, infusing CD44v6-targeted T cells in human hematochimeric mice caused selective and reversible monocytopenia, indicating preservation of the HSC pool. Most importantly, despite recognizing monocytes and tumor cells in vitro, CD44v6-targeted T cells completely spared keratinocytes. In our opinion, the reasons for this discrepancy are not entirely explained by lower target expression on nonsusceptible keratinocytes, but it is possibly explained by higher expression of accessory/costimulatory molecules on highly susceptible tumor cells (not shown). Nonetheless, these results strongly suggest that CD44v6-targeted T cells may have a significantly higher therapeutic index than drug or radio conjugates or, in other terms, that different from mAb-derived pharmaceuticals, therapeutic doses of CD44v6 might associate with acceptable and/or reversible toxicities.

Finally, because our data predict monocytopenia as the dose-limiting toxicity of CD44v6-targeted T cells, we have explored the coexpression of clinical-grade suicide genes51,52 for controlling the adverse events that may potentially derive from it (eg, immune incompetence). Different from TK, we found that the nonimmunogenic suicide gene iC9 enabled full ablation of CD44v6-targeted T cells within hours of exposure to the activating drug and complete rescue from hyperacute xenogeneic GVHD, suggesting the potential for reverting not only prolonged monocytopenia but also early and generalized toxicity caused by excessive on-target recognition.12,16

In conclusion, given the highly unmet medical need of curative forms of treatment for AML and MM that are otherwise resistant to conventional radiochemotherapy, we believe that the extensive preclinical validation of suicidal CD44v6-targeted T cells presented in our work warrant their investigation in a first-in-man trial to be conducted in the near future.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

There is an Inside Blood commentary on this article in this issue.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Alessandra Forcina for help with patient information, and Annarita Miccio and Alessia Cavazza for kindly providing primary cultured keratinocytes. M.C. conducted this study as partial fulfillment of her PhD in Molecular Biology, Vita-Salute San Raffaele University/Open University (London). B.N.d.R. and P.G. conducted this study as partial fulfillment of their PhD in Molecular Medicine, Vita-Salute San Raffaele University, Milano.

This work was supported by the Italian Association for Cancer Research (My First AIRC Grant) (A.B.); AIRC Special Program Molecular Clinical Oncology 5 per mille Nr. 9965; AIRC Investigator Grant (C. Bordignon); the American National Blood Foundation (Scientific Research Grant) (A.B.); the Umberto Veronesi Foundation (Research Fellowship) (B.N.d.R.), the Italian Ministry of Health (GR07-5 BO) (C. Bonini); and the Italian Ministry of Research and University (FIRB-IDEAS) (C. Bonini).

Authorship

Contribution: M.C. designed experiments, performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; B.N.d.R., P.G., and B.G. designed experiments and performed research; L.F., B.C., M.N., and F.G. performed research; A.S. provided CB units; M.B. and M.M. provided patient material; M.P. analyzed tissue sections by immunohistochemistry; C. Bordignon, B.S., and F.C. assisted with experimental design; L.N. and G.D. assisted with construct design and revised the manuscript; C. Bonini designed experiments and revised the manuscript; and A.B. designed research, analyzed data, wrote the manuscript, and acted as senior author of the study.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: C. Bordignon is an employee of Molmed Spa. C. Bonini is a consultant to MolMed Spa, whose potential product is studied in this work. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Attilio Bondanza, Leukemia Immunotherapy Group, Division of Regenerative Medicine, Stem Cells and Gene Therapy, San Raffaele Scientific Institute, via Olgettina 60, 20132, Milan, Italy; e-mail: bondanza.attilio@hsr.it.