Key Points

In cerebral malaria, IEs cause loss of protein C receptors and a highly localized microvascular coagulopathy.

Low cerebral constitutive expression of these receptors, EPCR and TM, may explain the brain's vulnerability to IE-dependent pathology.

Abstract

Cerebral malaria (CM) is a major cause of mortality in African children and the mechanisms underlying its development, namely how malaria-infected erythrocytes (IEs) cause disease and why the brain is preferentially affected, remain unclear. Brain microhemorrhages in CM suggest a clotting disorder, but whether this phenomenon is important in pathogenesis is debated. We hypothesized that localized cerebral microvascular thrombosis in CM is caused by a decreased expression of the anticoagulant and protective receptors thrombomodulin (TM) and endothelial protein C receptor (EPCR) and that low constitutive expression of these regulatory molecules in the brain make it particularly vulnerable. Autopsies from Malawian children with CM showed cerebral fibrin clots and loss of EPCR, colocalized with sequestered IEs. Using a novel assay to examine endothelial phenotype ex vivo using subcutaneous microvessels, we demonstrated that loss of EPCR and TM at sites of IE cytoadherence is detectible in nonfatal CM. In contrast, although clotting factor activation was seen in the blood of CM patients, this was compensated and did not disseminate. Because of the pleiotropic nature of EPCR and TM, these data implicate disruption of the endothelial protective properties at vulnerable sites and particularly in the brain, linking coagulation and inflammation with IE sequestration.

Introduction

Plasmodium falciparum malaria causes nearly one-quarter of all childhood deaths in sub-Saharan Africa.1 Cerebral malaria (CM), a major cause of malaria-associated mortality and morbidity, is characterized by parasitemia and unrousable coma where other causes of encephalopathy have been excluded.2 Although highly effective antimalarial drugs are widely available, CM case fatality remains 15% to 20% and among those who survive, one-third develop neurological disability, epilepsy, or behavioral problems.3 Although implementation of insecticide-treated bed nets, indoor residual spraying, artemisinin-based chemotherapy, and recent developments in vaccines have been important breakthroughs, it is likely that severe malaria will remain a considerable burden in many African countries for the foreseeable future.1

Sequestration of P falciparum-infected erythrocytes (IEs) in the cerebral microvasculature is a hallmark of CM,2 yet this process also occurs in other tissues without obvious dysfunction.4 Numerous studies have implicated inflammation and endothelial dysfunction in the pathogenesis of CM (for review, see Grau and Craig5 ), but it remains unclear why the brain is preferentially affected. A feature specific to the brain and the neuroendothelium of the retina are the small hemorrhages seen postmortem.2,6-8 In some studies, these have been shown to be associated with platelets9 or fibrin thrombi,8,10,11 but their specificity and the role of coagulation in CM remain controversial.12,13 In his Chairman’s address to the Southern Medical Association in 1944, R.H. Rigdon observed: “…there is insufficient evidence at this time to support the opinion that petechiae develop in the brain in malaria as the result of the formation of either emboli or thrombi.”7 Despite considerable research efforts, this uncertainty has persisted. In nonimmune adults with CM, overt disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) occurs in ∼5% of cases14 and the presence of a coagulopathy in P falciparum infection is suggested by increased circulating thrombin-antithrombin III complexes (TAT), fibrinopeptide A, and soluble thrombomodulin (TM) concentrations and by decreased levels of antithrombin and proteins S and C.14-16 Data on coagulation in pediatric CM are lacking and clinical evidence of DIC is rare12 and therefore adult data cannot be directly extrapolated. Fibrin degradation products are raised in pediatric CM,17 indicating a procoagulant state, and indeed TF is upregulated in the brain postmortem in pediatric CM.18 However, tissue factor is also observed in postmortem samples from parasitemic children who have died of nonmalarial causes,18 and the single study measuring functional coagulation tests in African children with CM indicated that they are no different from children with uncomplicated malaria.19 Thus, it remains unclear whether the dysregulation of coagulation observed in African children with CM is induced by falciparum parasitemia or whether it is an active component of disease pathogenesis influencing the organ specificity of CM.

The repertoire of expressed surface receptors is an important determinant of endothelial function, which differs markedly between organs.20 A specific profile of receptors expressed on cerebral endothelium may therefore explain a different response to IE sequestration in CM. Endothelial protein C receptor (EPCR) and TM are essential components of the anticoagulant protein C pathway, an endothelial homeostatic signal critical in regulating coagulation, inflammation, endothelial barrier function, and neuroprotection.21-23 Dysfunction of this pathway is implicated in bacterial sepsis,24 dengue hemorrhagic fever,25 Crohn’s disease26 and multiple sclerosis27 and the receptors EPCR and TM are expressed at lower constitutive levels in the brain compared with other organs.28,29 In addition, a hypercoagulable mouse model with a partial TM knockout resulted in fibrin deposits within the brain30 and Factor V Leiden, a genetic defect in the protein C pathway, is a risk factor for pediatric stroke.31 We therefore hypothesized that in patients with CM, IE cytoadherence may interfere with EPCR and/or TM expression and that the low constitutive expression of endothelial TM and EPCR in the cerebral microvasculature makes the brain particularly vulnerable to decompensation, leading to thrombin production, microvascular fibrin deposition, and microhemorrhages.

Materials and methods

Also see supplemental Appendix (on the Blood website).

Study participants

Patients and controls aged 1 to 12 years were recruited at Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital, Blantyre, Malawi between January 2008 and July 2011. Five clinical groups were prospectively defined: retinopathy-positive CM, retinopathy-negative CM, uncomplicated malaria, mild aparasitemic febrile illness, and healthy controls. CM was defined by clinical criteria2 and retinopathy-positive and retinopathy-negative CM by the presence or absence of retinal whitening, vessel changes, and/or microhemorrhages.10 This retinopathy is a sensitive and specific indicator of associated sequestration in cerebral vessels and serves to distinguish definitive retinopathy-positive CM from retinopathy-negative parasitemic encephalopathies with another etiology for coma.2 Uncomplicated malaria and mild aparasitemic febrile illness cases were recruited from children with acute febrile illness without signs of organ compromise.12 Healthy controls were children attending elective surgery. The study was approved by the ethical boards at the College of Medicine in Malawi (no. P.02/10/860) and Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine in the United Kingdom (no. 09.74). Informed consent was obtained from the parents or legal guardians of all the children enrolled in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Postmortem samples

Postmortem samples were obtained between January 2000 and May 2006 from full autopsy examinations, performed within hours of death, on children who fulfilled the WHO clinical definition of CM.2 Two groups were defined: CM characterized by IE sequestration in cerebral vessels and non-CM coma characterized by absence of IE sequestration in cerebral vessels.6 Although the non-CM group fulfilled criteria for CM during life, a nonmalarial cause of coma and death was found in each case at autopsy.2 The 4-μm–thick, formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded samples of cerebral cortex were stained for fibrin accumulation using the trichromic method,32 and samples of cerebral cortex and subcutaneous tissue were stained for endothelial receptors using the avidin-biotin method.29 The samples were incubated with primary antibodies (TM clone 1009, 7.6 μg/mL; EPCR clone 1489,29 92 μg/mL brain, 15 μg/mL subcutaneous tissue) for 1 hour. High-pressure heat-induced antigen retrieval in citrate buffer (pH 6.0) was performed prior to incubation with EPCR antibody. Bound primary antibody was detected with an immunoperoxidase kit (EnVision Plus; Dako). Negative controls without primary antibody were routinely used to confirm specificity.

The degree of fibrin accumulation and the staining intensity of EPCR were scored in comparison with reference micrographs by one of the authors (C.A.M.) and 2 independent medical pathologists who were unaware of the study aims and were blinded to diagnosis. Each scorer scored 50 vessels per case and the results were combined, giving 150 vessels scored for each case for each stain. Statistical analysis was conducted on the combined scores.

Blood and ex vivo tissue samples

Plasma, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and subcutaneous tissue samples were obtained from patients and controls between January 2008 and June 2011 (Table 1). Blood was obtained by venipuncture and citrate and benzamidine citrate plasma prepared as previously described.33 Samples were immediately frozen at −80°C. Coagulation tests were determined on an MDA180 analyzer (Stago, France) and activated protein C (aPC) levels by enzyme-capture.33 Plasma and CSF antigens were determined using commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits: intracellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1, DY720; R&D), TM (DY3947; R&D), EPCR (0264; Stago, France), albumin (E80-129; Bethyl Laboratories), F1+2 (Enzygnost F1+2; Dade Behring, Germany), and TATs (Enzygnost TAT micro; Dade Behring).

Clinical characteristics of the children

| . | Healthy controls . | Mild febrile illness . | Uncomplicated malaria . | Febrile controls (CSF samples) . | Nonmalarial coma . | Retinopathy-negative CM . | Retinopathy-positive CM . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 30) . | (n = 32) . | (n = 31) . | (n = 14) . | (n = 16) . | (n = 41) . | (n = 161) . | |

| Age, median years (IQR) | 4.8 (2.7-8) | 3.1 (1.8-5.4)* | 5.4 (3.1-6.8) | 4.0 (2.3-5.5) | 4.4 (2.6-5.2) | 3.8 (2.5-5.2) | 4.2 (2.7-5.2) |

| Female sex, n (%) | 12 (40) | 13 (41) | 15 (48) | 3 (21) | 8 (50) | 19 (45) | 89 (55) |

| HIV-positive, n (%)† | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 2 (14) | 0 (0) | 4 (9.5) | 11 (6.7) |

| Findings at presentation, median (IQR) | |||||||

| Axillary temperature | 36.6 (36.2-37) | 38.5 (38-38.9)*** | 38.7 (38.1-39.5)*** | 39.2 (38.4-40.0)*** | 38.8 (38.2-39.6)*** | 39 (38.1-39.8)*** | 38.8 (38-39.5)*** |

| Pulse rate, beats/min | 108 (102-119) | 132 (105-156)* | 128 (107-152)* | 108 (95-151) | 147 (122-160)** | 153 (133.5-166)*** | 152 (138-171)*** |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 105 (97-116) | 113 (106-122) | 108 (102-120) | 116 (111-126)* | 98 (91-108) | 99 (90-107)* | 98 (89-109)* |

| Respiratory rate, breaths/min | 28 (26-36) | 32 (28-36) | 29 (26-32) | 32 (28-37) | 40 (36-59)*** | 43 (38-52)*** | 44 (36-52)*** |

| Blood glucose, mmol/L | 4.9 (4.6-5.6) | 4.8 (4.3-5.4) | 5.5 (4.6-6.3) | 5.4 (5-5.9)* | 6.4 (5.1-7.5)* | 6.5 (5.7-10.5)*** | 6.4 (5.1-7.9)*** |

| Blood lactate, mmol/L | 1.8 (1.4-2) | 1.4 (1.1-2.1)* | 2 (1.3-3) | 1.9 (1.6-2.3) | 3.5 (2.8-5.5)** | 4.2 (2.7-7.3)*** | 6.2 (3.7-10.5)*** |

| Hb, g/dL | 10.2 (9.0-10.8) | 11.6 (11.0-12.3)** | 10.2 (9.1-11.6) | 10.4 (9.8-11.7) | 9.2 (7.6-9.9) | 8.9 (7.5-10.5)* | 6.5 (5.5-7.8)*** |

| Platelets, ×109/L | 435 (309-476) | 327 (237-387)** | 112 (75-144)*** | 270 (157-309)** | 254 (119-680)* | 138 (56-290)*** | 57 (28-92)*** |

| Parasitemia, parasites ×103/μL | 0 | 0 | 37 (2.9-201)*** | 0 | 0 | 52 (11-254)*** | 73 (14-280)*** |

| . | Healthy controls . | Mild febrile illness . | Uncomplicated malaria . | Febrile controls (CSF samples) . | Nonmalarial coma . | Retinopathy-negative CM . | Retinopathy-positive CM . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 30) . | (n = 32) . | (n = 31) . | (n = 14) . | (n = 16) . | (n = 41) . | (n = 161) . | |

| Age, median years (IQR) | 4.8 (2.7-8) | 3.1 (1.8-5.4)* | 5.4 (3.1-6.8) | 4.0 (2.3-5.5) | 4.4 (2.6-5.2) | 3.8 (2.5-5.2) | 4.2 (2.7-5.2) |

| Female sex, n (%) | 12 (40) | 13 (41) | 15 (48) | 3 (21) | 8 (50) | 19 (45) | 89 (55) |

| HIV-positive, n (%)† | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 2 (14) | 0 (0) | 4 (9.5) | 11 (6.7) |

| Findings at presentation, median (IQR) | |||||||

| Axillary temperature | 36.6 (36.2-37) | 38.5 (38-38.9)*** | 38.7 (38.1-39.5)*** | 39.2 (38.4-40.0)*** | 38.8 (38.2-39.6)*** | 39 (38.1-39.8)*** | 38.8 (38-39.5)*** |

| Pulse rate, beats/min | 108 (102-119) | 132 (105-156)* | 128 (107-152)* | 108 (95-151) | 147 (122-160)** | 153 (133.5-166)*** | 152 (138-171)*** |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 105 (97-116) | 113 (106-122) | 108 (102-120) | 116 (111-126)* | 98 (91-108) | 99 (90-107)* | 98 (89-109)* |

| Respiratory rate, breaths/min | 28 (26-36) | 32 (28-36) | 29 (26-32) | 32 (28-37) | 40 (36-59)*** | 43 (38-52)*** | 44 (36-52)*** |

| Blood glucose, mmol/L | 4.9 (4.6-5.6) | 4.8 (4.3-5.4) | 5.5 (4.6-6.3) | 5.4 (5-5.9)* | 6.4 (5.1-7.5)* | 6.5 (5.7-10.5)*** | 6.4 (5.1-7.9)*** |

| Blood lactate, mmol/L | 1.8 (1.4-2) | 1.4 (1.1-2.1)* | 2 (1.3-3) | 1.9 (1.6-2.3) | 3.5 (2.8-5.5)** | 4.2 (2.7-7.3)*** | 6.2 (3.7-10.5)*** |

| Hb, g/dL | 10.2 (9.0-10.8) | 11.6 (11.0-12.3)** | 10.2 (9.1-11.6) | 10.4 (9.8-11.7) | 9.2 (7.6-9.9) | 8.9 (7.5-10.5)* | 6.5 (5.5-7.8)*** |

| Platelets, ×109/L | 435 (309-476) | 327 (237-387)** | 112 (75-144)*** | 270 (157-309)** | 254 (119-680)* | 138 (56-290)*** | 57 (28-92)*** |

| Parasitemia, parasites ×103/μL | 0 | 0 | 37 (2.9-201)*** | 0 | 0 | 52 (11-254)*** | 73 (14-280)*** |

IQR, interquartile range; Hb, hemoglobin.

For each variable differences between healthy controls and other patient groups were examined using a Mann-Whitney U test (continuous variables) or Fisher’s exact test (categorical variables). *P ≤ .05; **P ≤ .01; ***P ≤ .001.

HIV was tested for using rapid testing (Determine; Inverness Medical).

Samples of subcutaneous tissue were obtained by percutaneous needle aspiration biopsy8 from comatose CM patients and anesthetized healthy surgical controls. Immunofluorescence staining was performed on methanol-fixed slide smears by 1-hour incubation with mouse monoclonal primary antibodies: CD31 (clone 5.6E; Immunotech), ICAM-1 (clone 84H10; Immunotech), TM (clone 1009), or EPCR (clone 146229 ) followed by 30-minute incubation with Alexafluor 488 goat anti-mouse (Invitrogen). For flow cytometry analysis, a single cell suspension was prepared by collagenase digestion (35 minutes at 37°C, 3 mg/mL type II; Gibco), and a gentleMACS dissociator (Miltenyi Biotec). Cell surface staining was performed for 30 minutes at 4°C using the following conjugated monoclonal antibodies: EPCR-phycoerythrin (clone RCR252; BD Biosciences CD45-allophycocyanin-cynanine 7 (clone 2D1; BD); TM-allophycocyanin (clone 501733; R&D); ICAM-1- phycoerythrin- cynanine 5 (clone HCD54; Biolegend); CD31- phycoerythrin dynomics 590 (MEM-05; Exbio Praha); and live dead yellow fixable viability marker (Invitrogen). Isotype controls were used to set the limit of detection.

Statistical methods

Statistical analysis was performed using Stata (version 11) and Prism (version 5.0) software. Continuous variables were assumed to have normal or log normal distribution depending on their level of skewness; differences between groups for these variables were compared using simple linear regression models, with the Tukey honestly significant difference test to adjust for multiple comparisons. For ordered categorical slide scoring data, differences between groups were compared using ordinal logistic regression models, controlling for clustering within cases and adjusting for any differences between scorers; results are presented as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and as correlation coefficients. All tests were 2-tailed with a conventional 5% α-level.

Results

Marked fibrin deposition in the microvasculature of the brain in CM is associated with IE sequestration and reduced expression of EPCR

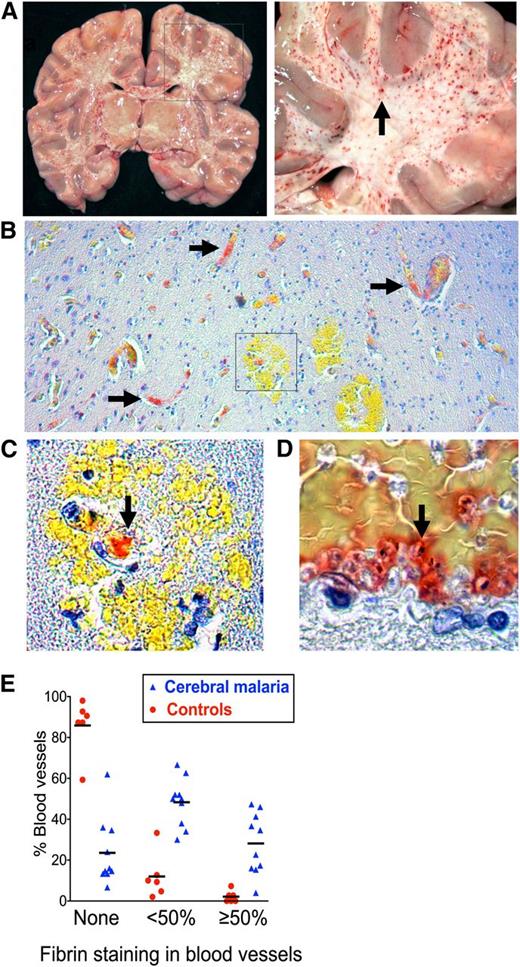

To determine whether characteristic petechial lesions in the brain in fatal CM (Figure 1A) are associated with thrombosis and whether this process is specific to CM, we stained postmortem brain samples for fibrin (trichromic method32 ). Samples were obtained from 10 Malawian children with autopsy-confirmed CM and 6 contemporaneous non-CM controls with fatal encephalopathy and parasitemia but no cerebral IE sequestration and a clear alternative cause of death (supplemental Table 1). Fibrin deposition was significantly more common in CM cases than in non-CM controls (Figure 1B-E; OR: 19.96; 95% CI: 7.05-56.55; P ≤ .001) and was associated with IE sequestration (Figure 1D; correlation coefficient = 0.60; P ≤ .001). Microvascular hemorrhage was much less common than fibrin deposition (2.6% of vessels in CM cases and 0.2% of vessels in controls) and was associated with small vessels that contained fibrin (Figure 1C).

Microvascular thrombosis in association with IE sequestration in CM. (A) Coronal section of the brain from a child with fatal CM (right image detail of box in left) shows typical hemorrhagic lesions (arrow). (B) Low-power view (10× lens) shows fibrin deposition in microvessels in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue from CM case stained for fibrin using trichromic staining (fibrin stains red and red blood cells stain yellow) (C) Detail of box in 1B (40× lens) shows fibrin at the center of a ring hemorrhage (arrow). (D) Colocalization of fibrin and IE cells as indicated by malaria pigment (black dots, arrow). (E) Fibrin deposition was significantly higher in CM cases than in non-CM encephalopathic illness controls. The extent of the vessel lumen containing fibrin was scored as none, <50%, or ≥50 in 10 CM cases and 6 non-CM controls. Scoring was performed by the author and 2 blinded medical pathologists who each scored 50 vessels per case. Datapoints are a combination of the data from all 3 scorers and indicate the percentage of vessels scored at each level in individual cases and bars the mean percentage of vessels scored at each level for the CM or non-CM group as a whole. Micrographs were taken using a Leica DM1L microscope (Leica Microsystems) and a Micropublisher 3.3 RTV (QImaging) camera using Image ProPlus version 6.2 software (Media Cybernetics).

Microvascular thrombosis in association with IE sequestration in CM. (A) Coronal section of the brain from a child with fatal CM (right image detail of box in left) shows typical hemorrhagic lesions (arrow). (B) Low-power view (10× lens) shows fibrin deposition in microvessels in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue from CM case stained for fibrin using trichromic staining (fibrin stains red and red blood cells stain yellow) (C) Detail of box in 1B (40× lens) shows fibrin at the center of a ring hemorrhage (arrow). (D) Colocalization of fibrin and IE cells as indicated by malaria pigment (black dots, arrow). (E) Fibrin deposition was significantly higher in CM cases than in non-CM encephalopathic illness controls. The extent of the vessel lumen containing fibrin was scored as none, <50%, or ≥50 in 10 CM cases and 6 non-CM controls. Scoring was performed by the author and 2 blinded medical pathologists who each scored 50 vessels per case. Datapoints are a combination of the data from all 3 scorers and indicate the percentage of vessels scored at each level in individual cases and bars the mean percentage of vessels scored at each level for the CM or non-CM group as a whole. Micrographs were taken using a Leica DM1L microscope (Leica Microsystems) and a Micropublisher 3.3 RTV (QImaging) camera using Image ProPlus version 6.2 software (Media Cybernetics).

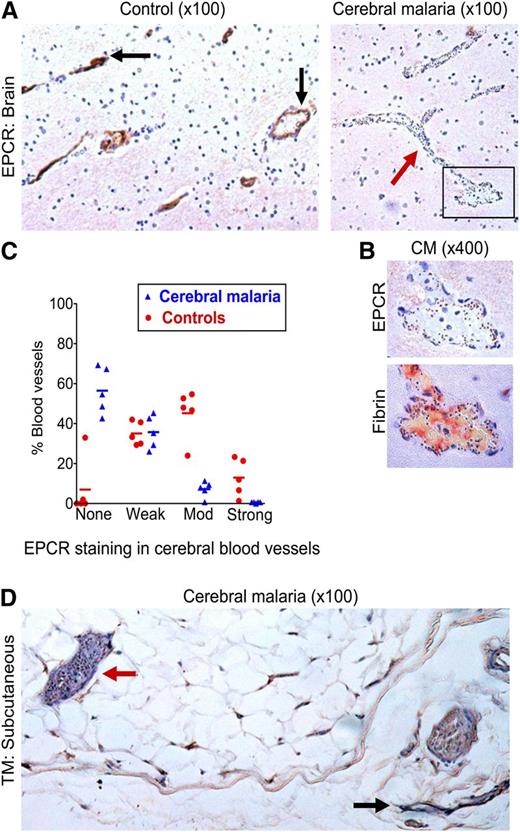

To then assess whether the microvascular coagulopathy identified is associated with underlying loss of the anticoagulant endothelial receptors critical to the protein C pathway, we performed avidin-biotin immunostaining for EPCR and TM on the same series of postmortem samples. Tissue was available for 7 CM cases and 6 non-CM cases, but 2 CM cases and 1 non-CM cases were excluded because of tissue damage following antigen retrieval. EPCR staining in cerebral microvessels was decreased in the 5 CM cases compared with the 5 non-CM controls (OR: 0.048; 95% CI: 0.012-0.20; P ≤ .001) (Figure 2A-C). EPCR staining in CM cases was generally patchy with decreased or absent staining in vessels with high IE sequestration (Figure 2B; supplemental Figure 1) and there was a negative association between EPCR staining and IE sequestration (correlation coefficient = −0.57; P ≤ .001).

Loss of EPCR in the brain in CM and of TM in subcutaneous tissue. (A) Low-power (10× lens) view of postmortem brain samples shows vessels with moderate-to-strong staining for EPCR (immunoperoxidase method, arrows) in a non-CM control brain sample (left) and absence of EPCR staining in a vessel containing many sequestered IEs (arrow) in a CM case (right). (B) Association between IE sequestration, loss of EPCR, and fibrin deposition; upper image is a detail (40× lens) of the box in the bottom right of 2A and the lower image shows fibrin deposition (trichromic staining) in a consecutive tissue section. (C) EPCR staining is significantly reduced in CM compared with non-CM encephalopathic controls. The intensity of staining for EPCR was scored as none, weak, moderate (mod), or strong in 5 CM cases and 5 controls compared with reference images by the author and 2 independent pathologists. Datapoints are a combination of the data from all 3 scorers and indicate the percentage of vessels scored at each level in individual cases and bars the mean percentage of vessels scored at each level for the CM or non-CM group as a whole. (D) Subcutaneous tissue section in a fatal CM case. The red arrow indicates a vessel with high IE sequestration and minimal TM staining and the black arrow indicates a vessel with minimal IE sequestration and strong TM staining.

Loss of EPCR in the brain in CM and of TM in subcutaneous tissue. (A) Low-power (10× lens) view of postmortem brain samples shows vessels with moderate-to-strong staining for EPCR (immunoperoxidase method, arrows) in a non-CM control brain sample (left) and absence of EPCR staining in a vessel containing many sequestered IEs (arrow) in a CM case (right). (B) Association between IE sequestration, loss of EPCR, and fibrin deposition; upper image is a detail (40× lens) of the box in the bottom right of 2A and the lower image shows fibrin deposition (trichromic staining) in a consecutive tissue section. (C) EPCR staining is significantly reduced in CM compared with non-CM encephalopathic controls. The intensity of staining for EPCR was scored as none, weak, moderate (mod), or strong in 5 CM cases and 5 controls compared with reference images by the author and 2 independent pathologists. Datapoints are a combination of the data from all 3 scorers and indicate the percentage of vessels scored at each level in individual cases and bars the mean percentage of vessels scored at each level for the CM or non-CM group as a whole. (D) Subcutaneous tissue section in a fatal CM case. The red arrow indicates a vessel with high IE sequestration and minimal TM staining and the black arrow indicates a vessel with minimal IE sequestration and strong TM staining.

As previously reported,29,34 we did not detect TM in cerebral vessels using immunoperoxidase staining in cases or controls. To explore the pattern of TM staining in another tissue where there is marked IE sequestration, we used postmortem subcutaneous tissue. Microvessels in the 5 non-CM cases consistently showed moderate or strong staining for TM, but staining in CM was patchy with IE sequestration frequently associated with absence of TM staining (Figure 2; supplemental Table 1) and often with moderate to strong staining in adjacent vessels lacking sequestered parasites (Figure 2). We therefore propose that the already very low levels of TM expressed in the brain are likely to be further reduced at sites of IE sequestration in CM.

Reduced endothelial TM and EPCR in the subcutaneous microvasculature of comatose children with CM

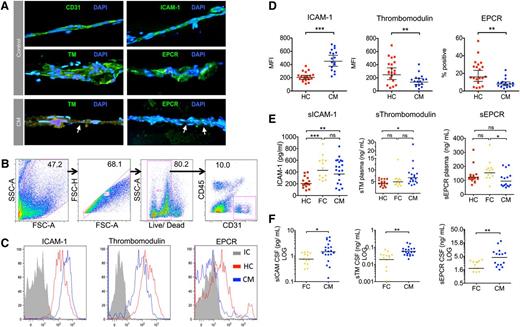

To determine whether EPCR and TM are reduced in CM at the time of presentation and not only in fatal or end-stage disease, we developed a novel approach to examine endothelial phenotype ex vivo, using flow cytometry analysis of digested subcutaneous fat tissue samples. Subcutaneous tissue microvessels were used because: 1) they are accessible and have substantive IE sequestration in CM4,35 ; 2) they are similar to cerebral microvessels in expression of a number of endothelial receptors, including principle receptors for IE binding36; and 3) they have a similar pattern of endothelial IE-associated protein C receptor loss as cerebral microvessels in postmortem tissue (Figure 2).

Samples were recruited from Malawian children with retinopathy-positive CM on admission and from healthy children under general anesthetic prior to elective surgery. The presence of microvessels in the subcutaneous samples was confirmed in smears from healthy controls and CM cases by cell morphology and immunofluorescence staining for the endothelial receptors CD31, ICAM-1, TM, and EPCR (Figure 3A). In CM cases, IE sequestration was associated with reduced TM and EPCR staining (Figure 3A). Analysis of collagenase dissociated tissue biopsies from 20 CM cases and 17 healthy controls by flow cytometry identified subpopulations of single live CD31+CD45− endothelial cells (Figure 3B; range, 282-5214 events). Mean cell viability was similar between the 2 groups: healthy controls: 80.8% (95% CI: 77.6%-84%); CM: 74.6% (95% CI: 70.6-78.6). Endothelial ICAM-1 expression was increased in CM compared with healthy controls (Figure 3C; P ≤ .001). In contrast, endothelial TM and EPCR were decreased in CM compared with healthy controls (Figure 3C; P = .01 and P = .004).

Endothelial activation and decreased EPCR and TM ex vivo in biopsies from children with CM. (A) Immunofluorescence-labeled needle biopsies samples of subcutaneous tissue from healthy children and children with CM. Nuclei appear blue (DAPI) and endothelial receptors green (Alexafluor 488). Micrographs (40× lens) show microvessels from healthy children as indicated by morphology, elliptical endothelial nuclei, and bright staining for CD31, ICAM-1, TM, and EPCR. Vessels from a CM case show IE sequestration (arrows) associated with low TM and EPCR staining. Needle biopsy samples were digested, labeled, and then analyzed by flow cytometer to examine the receptor expression of endothelial cells from microvessels in the sample. (B) Flow cytometry gating strategy for samples to distinguish endothelial cells as single, live, CD31+CD45− cells. (C) Histograms for 3 different endothelial receptors: ICAM-1, TM, and EPCR; representative plots from a single case for CM (blue), healthy children (HC; red), and antibody isotype control (IC, gray). ICAM-1 and TM staining show low overlap with the isotype control and receptor expression was determined by mean fluorescence intensity (MFI), whereas EPCR staining overlapped considerably with the isotype and expression was determined by percentage positive events. (D) Scatterplots for the endothelial expression levels of ICAM-1, TM, and EPCR as determined by flow cytometry in 17 CM cases and 20 HCs. (E) Scatterplots for levels of soluble ICAM-1, soluble TM, and soluble EPCR as determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay in plasma samples in HC, CM, and aparasitemic febrile controls (FC) who were noncomatose patients that had a lumbar puncture taken because of clinical suspicion of meningitis. (F) Scatterplots for levels of soluble ICAM-1, soluble TM, and soluble EPCR in paired CSF samples in FC and CM; CSF samples were not taken from healthy children. Horizontal lines indicate geometric means and bars 95% CIs. Significance determined by one-way analysis of variance with the Tukey honestly significant difference test to adjust for multiple comparisons in E. * P < .05, ** P < .01, *** P < .001. Fluorescence micrographs were taken using a Leica DM1L microscope and a Leica DFC300FX camera using Leica Application Suite version 2.6.0 software.

Endothelial activation and decreased EPCR and TM ex vivo in biopsies from children with CM. (A) Immunofluorescence-labeled needle biopsies samples of subcutaneous tissue from healthy children and children with CM. Nuclei appear blue (DAPI) and endothelial receptors green (Alexafluor 488). Micrographs (40× lens) show microvessels from healthy children as indicated by morphology, elliptical endothelial nuclei, and bright staining for CD31, ICAM-1, TM, and EPCR. Vessels from a CM case show IE sequestration (arrows) associated with low TM and EPCR staining. Needle biopsy samples were digested, labeled, and then analyzed by flow cytometer to examine the receptor expression of endothelial cells from microvessels in the sample. (B) Flow cytometry gating strategy for samples to distinguish endothelial cells as single, live, CD31+CD45− cells. (C) Histograms for 3 different endothelial receptors: ICAM-1, TM, and EPCR; representative plots from a single case for CM (blue), healthy children (HC; red), and antibody isotype control (IC, gray). ICAM-1 and TM staining show low overlap with the isotype control and receptor expression was determined by mean fluorescence intensity (MFI), whereas EPCR staining overlapped considerably with the isotype and expression was determined by percentage positive events. (D) Scatterplots for the endothelial expression levels of ICAM-1, TM, and EPCR as determined by flow cytometry in 17 CM cases and 20 HCs. (E) Scatterplots for levels of soluble ICAM-1, soluble TM, and soluble EPCR as determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay in plasma samples in HC, CM, and aparasitemic febrile controls (FC) who were noncomatose patients that had a lumbar puncture taken because of clinical suspicion of meningitis. (F) Scatterplots for levels of soluble ICAM-1, soluble TM, and soluble EPCR in paired CSF samples in FC and CM; CSF samples were not taken from healthy children. Horizontal lines indicate geometric means and bars 95% CIs. Significance determined by one-way analysis of variance with the Tukey honestly significant difference test to adjust for multiple comparisons in E. * P < .05, ** P < .01, *** P < .001. Fluorescence micrographs were taken using a Leica DM1L microscope and a Leica DFC300FX camera using Leica Application Suite version 2.6.0 software.

Increased levels of soluble EPCR and TM in the CSF in CM

To assess whether altered levels of endothelial receptors in the brain and subcutaneous tissue were associated with increased receptor shedding, we measured soluble receptor levels in the blood. In addition, to give an indication of receptor shedding specifically from the cerebral vasculature, we measured soluble receptor levels in the CSF. Because it is not ethical to take CSF from healthy children, the control group for CSF samples was noncomatose aparasitemic children with fever, who had CSF taken to rule out a diagnosis of meningitis. In the blood, soluble ICAM-1 and soluble TM levels were increased compared with levels in healthy control children (Figure 3E). In contrast, soluble EPCR levels were not significantly different from levels in healthy children and were decreased compared with the febrile controls (Figure 3E). In the CSF, there were significantly higher levels of all 3 receptors compared with the febrile controls (Figure 3F), and these remained significantly increased when expressed as a ratio of plasma concentration (supplemental Figure 2A-C). This was not due to increased permeability of the blood-CSF barrier in CM, as CSF/plasma albumin ratios were similar between cases and controls (supplemental Figure 2D).

Compensated activation of coagulation in the blood in CM

To investigate whether the absence of protein C pathway endothelial receptors observed at sites of IE sequestration is associated with a more generalized coagulopathy, we measured plasma coagulation factors in Malawian children with CM and in comatose and non-comatose controls (Table 1). TATs, a sensitive indicator of thrombin generation, were raised in 66 children with retinopathy-positive CM compared with 19 healthy children (P ≤ .001) (Figure 4A; Table 1), 30 children with nonmalarial mild febrile illness (P ≤ .01), and 30 children with uncomplicated malaria (P ≤ .01). TAT levels were also higher in 18 children with retinopathy-negative CM than in the 19 healthy controls (P ≤ .05). Among retinopathy-positive CM cases, admission TAT levels were higher in the 16 children who eventually died than in those children who survived (P = .02) (Figure 4B). In contrast, prothrombin time was prolonged in retinopathy-positive CM (P ≤ .01) (Table 1; Figure 4C) and retinopathy-negative CM (P ≤ .01) compared with 30 healthy children but not when compared with 21 children with uncomplicated malaria or 24 children with mild aparasitemic febrile illness. Activated partial thromboplastin times were similar to the controls (Table 1; Figure 4D). This is in keeping with prior data indicating activation of coagulation through tissue factor activation15,18 rather than increased factor XII.14

Compensated activation of coagulation in CM. (A) Plasma TAT levels taken on admission in children with (right to left) retinopathy-positive CM (Ret Pos CM, n = 67), retinopathy-negative CM (Ret Neg CM, n = 19), nonmalarial coma (n = 11), uncomplicated malaria (n = 30), mild nonmalarial febrile illness (n = 30), and healthy controls (n = 19). (B) Plasma TAT levels taken on admission in patients with retinopathy-positive CM grouped according to outcome: those who eventually died (fatal [n = 16] and those who survived [nonfatal, n = 51]). (C) Prothrombin time and aPPT (D) in children with (from right to left) Ret Pos CM (n = 69), Ret Neg CM (n = 23), nonmalarial coma (n = 11), uncomplicated malaria (n = 21), mild nonmalarial febrile illness (n = 24), and healthy controls (n = 30). (E) aPC levels in plasma taken on admission in children with (from right to left): Ret Pos CM (n = 92), Ret Neg CM (n = 22), nonmalarial coma (n = 6), uncomplicated malaria (n = 24), mild nonmalarial febrile illness (n = 25), and healthy controls (n = 21). (F) Plasma aPC levels in retinopathy-positive children who eventually died (fatal, n = 16) and those who survived (nonfatal, n = 76). (G) Prothrombin fragment (F1+2)/aPC ratio in the same patients as 4E. (H) Prothrombin fragment levels in fatal and nonfatal retinopathy-positive CM. Horizontal lines indicate geometric means. Significance determined by ANOVA with the Tukey honestly significant difference test test on log-transformed data to adjust for multiple comparison. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.

Compensated activation of coagulation in CM. (A) Plasma TAT levels taken on admission in children with (right to left) retinopathy-positive CM (Ret Pos CM, n = 67), retinopathy-negative CM (Ret Neg CM, n = 19), nonmalarial coma (n = 11), uncomplicated malaria (n = 30), mild nonmalarial febrile illness (n = 30), and healthy controls (n = 19). (B) Plasma TAT levels taken on admission in patients with retinopathy-positive CM grouped according to outcome: those who eventually died (fatal [n = 16] and those who survived [nonfatal, n = 51]). (C) Prothrombin time and aPPT (D) in children with (from right to left) Ret Pos CM (n = 69), Ret Neg CM (n = 23), nonmalarial coma (n = 11), uncomplicated malaria (n = 21), mild nonmalarial febrile illness (n = 24), and healthy controls (n = 30). (E) aPC levels in plasma taken on admission in children with (from right to left): Ret Pos CM (n = 92), Ret Neg CM (n = 22), nonmalarial coma (n = 6), uncomplicated malaria (n = 24), mild nonmalarial febrile illness (n = 25), and healthy controls (n = 21). (F) Plasma aPC levels in retinopathy-positive children who eventually died (fatal, n = 16) and those who survived (nonfatal, n = 76). (G) Prothrombin fragment (F1+2)/aPC ratio in the same patients as 4E. (H) Prothrombin fragment levels in fatal and nonfatal retinopathy-positive CM. Horizontal lines indicate geometric means. Significance determined by ANOVA with the Tukey honestly significant difference test test on log-transformed data to adjust for multiple comparison. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.

Because activation of protein C is initiated by the presence of thrombin, if the protein C pathway is intact, then the increased thrombin generation demonstrated should be accompanied by increased protein C activation. However, protein C activation is dependent on both TM and EPCR. Although the loss of protein C receptors in CM appeared to be localized to areas of IE sequestration, it remained possible that this was more widespread and might impair protein C activation in the systemic circulation. Systemic aPC was measured in plasma with an enzyme capture method.33 Plasma aPC levels were raised in 87 children with retinopathy-positive CM compared with 21 healthy children (P ≤ .001) (Figure 4E), 25 children with mild febrile illness (P ≤ .05), and 24 children with uncomplicated malaria (P ≤ .05). aPC levels in 23 children with retinopathy-negative CM and 6 children with nonmalarial coma were similar to those with retinopathy-positive CM (Figure 4F). The F1+2/aPC ratio, an indicator of the balance between thrombin production and aPC production, was not different between CM and the other clinical groups (Figure 4G). There was also no statistical difference in aPC levels or the F1+2/aPC ratio at admission between children with retinopathy-positive CM who survived and those who eventually died (Figure 4F).

Given the range of ages in our study among children with retinopathy-positive CM, we examined the affect of age on the different factors measured, comparing levels in children younger than 5 years old with children 5 to 12 years old. aPC levels were significantly higher in children 1 to 4 years old (median 2.55, interquartile range: 1.65-3.48) than in children 5 to 12 years old (median: 1.48; interquartile range: 0.99-2.65; P = .02); however, this did not affect the thrombin-aPC balance, as F1+2/aPC ratios were similar in the 2 age groups (supplemental Table 2). TAT, prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time, and levels of TM and EPCR receptors in ex vivo samples were similar between the 2 age groups (supplemental Table 2).

Discussion

The observation of petechial lesions in fatal cases of CM has led several authors to propose an involvement of coagulation in CM pathogenesis.10,11,13 However, the rarity of overt DIC,12,14 prominent in other conditions in which coagulation is critical to pathogenesis, is puzzling. One explanation is that the postmortem cerebral lesions occur as a nonspecific byproduct of end-stage disease and that coagulation does not play a role in the development of CM. An alternative is that the coagulopathy of CM is caused by localized rather than systemic mechanism. Here in postmortem brain samples, we demonstrate that the coagulopathy of CM is specific, with fibrin deposition occurring significantly more commonly in CM than in fatal encephalopathic controls and with loss of the anticoagulant receptor EPCR in CM localized to sites of cytoadherent IE. In ex vivo biopsies, we demonstrate that loss of EPCR and TM occurs in nonfatal disease and is present at the time children present to hospital with CM, indicating that the shift to a procoagulant endothelial phenotype is not an end-stage event. Further, in contrast to previously proposed models of severe malaria,18 we show that in the systemic circulation coagulation is compensated. These data strongly implicate the protein C pathway in CM pathogenesis and address longstanding uncertainties around the importance of a clotting disorder in the disease. Further, they indicate that the coagulopathy of malaria is different from conditions with systemic activation of coagulation such as bacterial sepsis and that it does not disseminate because it is restricted to the microvessels where IE sequester.

Because IE cytoadherence and sequestration do not occur significantly in animal models of CM, investigation of associations between IE sequestration and disease development can be examined only in human CM.37 Postmortem samples allowed us to identify a previously unrecognized defect in the protein C pathway associated with a brain-specific pathology. Because it is not possible to access brain endothelium in life, to demonstrate the relevance of this IE-associated endothelial pathology in vivo, a surrogate tissue was required. Previous severe malaria studies have employed immunostaining on dermal38 or muscle39 biopsies, but these tissues lacked either endothelial activation38 or IE sequestration39 even in severe disease. We used subcutaneous biopsies, which exhibited both endothelial activation and IE sequestration, to demonstrate that EPCR and TM are reduced in CM in vivo. Increased CSF levels and blood/CSF ratio of cleaved EPCR and TM imply that receptor loss also occurs in vivo from the brain. Although subcutaneous endothelium has important differences from neuroendothelium, including higher TM and EPCR and a lack of tight junctions, it has a similar profile to other key endothelial receptors, including those implicated in IE binding,36 and the data presented here imply its validity as an ex vivo surrogate to indicate endothelial events in the inaccessible endothelium of the brain. Further, the flow cytometry approach developed allows simultaneous measurement of multiple parameters and, because it is objective, facilitates inter-patient or intra-patient comparison. We therefore suggest that the approach may have broader applicability to study vascular biology in malaria and in other diseases.

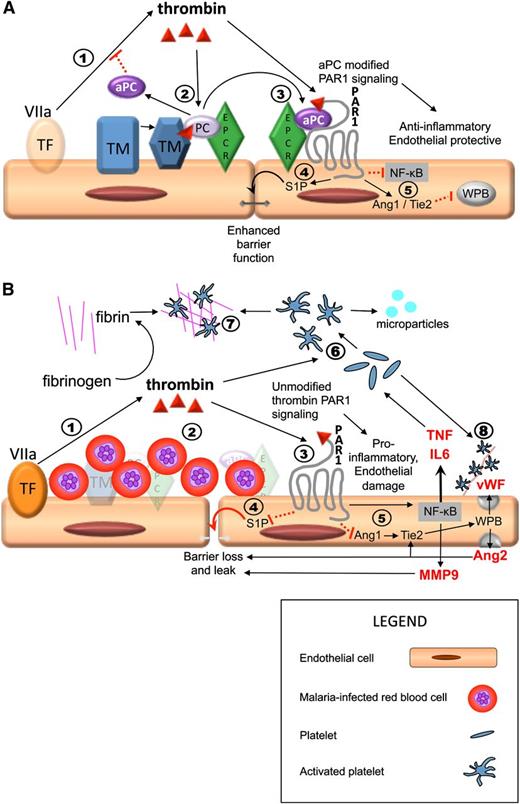

Previous studies on CM pathogenesis have suggested various mechanisms, including metabolic disturbance by proinflammatory cytokines5 or microparticles40 ; biomechanical obstruction of the circulation by sequestered IE,41 platelets,42 and/or thrombi10 ; and endothelial dysfunction and increased endothelial permeability.43 There is ample evidence that all of these processes contribute to the development of CM, and as previously postulated by Clark et al44 and Francescheti et al,18 the pleotropic properties of the protein C pathway represent a compelling link between these pathogenic mechanisms (Figure 5), with the low constitutive expression of EPCR and TM providing an explanation for the vulnerability of the brain.

Sequestration-induced loss of protein C receptors links coagulation, inflammation, and endothelial permeability. PAR1 activation by thrombin acts as a molecular switch, inhibiting or promoting inflammation and leakage, depending on whether there is a modifying signal from the protein C pathway. Thrombin is produced by the interaction between circulating activated factor VII (VIIa) in the plasma and tissue factor on monocytes and from endothelial tissue factor induced by IE (step 1 in both A and B). (A) Thrombin/PAR1 signaling when the protein C system is intact; 2) thrombin initiates the TM/EPCR-facilitated activation of protein C, which inhibits thrombin production upstream; 3) aPC modifies the effect of PAR1 through EPCR; 4) aPC/EPCR-modified PAR1 signaling decreases endothelial permeability via S1P1 signaling (not shown) and production of S1P, which leads to enhancement of tight junctions; 5) in the presence of EPCR has pleotropic antiinflammatory and endothelial protective properties, including downregulation of Nuclear Factor κ-B (NFKB) and increased Angiopoetin-1 (Ang1) production. Ang1 decreases Weibel Palade body (WPB) exocytosis by occupancy of Tie2. (B) Thrombin/PAR1 signaling in a vessel with high level of sequestered malaria-IEs when there is complete loss of protein C receptors, such as in microvessels in the brain, and therefore no modification of PAR1 signaling. 2) IE sequestration is associated with loss of TM and EPCR; protein C is therefore not activated; 3) thrombin signals through PAR1 without modification by EPCR signaling; 4) unmodified PAR1 signaling inhibits S1P release with resultant loss of tight junctions, loss of endothelial barrier function, and localized vascular leak; and 5) thrombin signaling in the absence of modification by aPC/EPCR has strong proinflammatory effects, including upregulation of NFKB with increased tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and interleukin (IL)-6 production and reduction of Ang1 production, leading to increased Weibel Palade body (WPB) exocytosis with production of Von Willebrand Factor (vWF) and Ang2. Ang2 further increases WPB exocytosis by occupancy of Tie2 and also contributes to loss of endothelial barrier integrity and leak. 6) Thrombin and inflammatory cytokines cause activation of platelets, leading to the production of platelet microparticles. 7) In the absence of inhibition from aPC, thrombin triggers the production of fibrin from fibrinogen and fibrin and activated platelets coalesce to form thrombi. 8) Activated platelets adhere to vWF strings. Both thrombi and these platelet-vWF complexes impair cerebral circulation. Solid black arrows indicate stimulation of a pathway and dotted red lines indicate inhibition.

Sequestration-induced loss of protein C receptors links coagulation, inflammation, and endothelial permeability. PAR1 activation by thrombin acts as a molecular switch, inhibiting or promoting inflammation and leakage, depending on whether there is a modifying signal from the protein C pathway. Thrombin is produced by the interaction between circulating activated factor VII (VIIa) in the plasma and tissue factor on monocytes and from endothelial tissue factor induced by IE (step 1 in both A and B). (A) Thrombin/PAR1 signaling when the protein C system is intact; 2) thrombin initiates the TM/EPCR-facilitated activation of protein C, which inhibits thrombin production upstream; 3) aPC modifies the effect of PAR1 through EPCR; 4) aPC/EPCR-modified PAR1 signaling decreases endothelial permeability via S1P1 signaling (not shown) and production of S1P, which leads to enhancement of tight junctions; 5) in the presence of EPCR has pleotropic antiinflammatory and endothelial protective properties, including downregulation of Nuclear Factor κ-B (NFKB) and increased Angiopoetin-1 (Ang1) production. Ang1 decreases Weibel Palade body (WPB) exocytosis by occupancy of Tie2. (B) Thrombin/PAR1 signaling in a vessel with high level of sequestered malaria-IEs when there is complete loss of protein C receptors, such as in microvessels in the brain, and therefore no modification of PAR1 signaling. 2) IE sequestration is associated with loss of TM and EPCR; protein C is therefore not activated; 3) thrombin signals through PAR1 without modification by EPCR signaling; 4) unmodified PAR1 signaling inhibits S1P release with resultant loss of tight junctions, loss of endothelial barrier function, and localized vascular leak; and 5) thrombin signaling in the absence of modification by aPC/EPCR has strong proinflammatory effects, including upregulation of NFKB with increased tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and interleukin (IL)-6 production and reduction of Ang1 production, leading to increased Weibel Palade body (WPB) exocytosis with production of Von Willebrand Factor (vWF) and Ang2. Ang2 further increases WPB exocytosis by occupancy of Tie2 and also contributes to loss of endothelial barrier integrity and leak. 6) Thrombin and inflammatory cytokines cause activation of platelets, leading to the production of platelet microparticles. 7) In the absence of inhibition from aPC, thrombin triggers the production of fibrin from fibrinogen and fibrin and activated platelets coalesce to form thrombi. 8) Activated platelets adhere to vWF strings. Both thrombi and these platelet-vWF complexes impair cerebral circulation. Solid black arrows indicate stimulation of a pathway and dotted red lines indicate inhibition.

Our findings confirm that coagulation is activated through increased thrombin production, presumably by the tissue factor pathway in pediatric patients with P falciparum parasitemia,18 a phenomenon that leads to increased thrombin levels in children with both uncomplicated and CM (Figure 4). We propose that the extent and effect of this thrombin production is determined by the function of the regulatory protein C pathway (Figure 5). In patients with high IE sequestration, we suggest that interactions between IE and the endothelium induce cleavage of EPCR and TM. By diminishing the capacity to activate and respond to protein C (Figure 5B), there is a shift in the balance of the thrombin-protein C axis toward a proinflammatory and procoagulant state. In most tissues, there is sufficient reserve of surface-expressed EPCR and TM to maintain protein C activation and function, as indicated by raised aPC and a retained F1+2/aPC ratio in venous blood in CM. But in the brain, where constitutive levels of these receptors are low,28,29 the reduction in EPCR and TM may lead to functional loss and localized decompensation. This results in fibrin deposition, platelet activation, inflammation, and fluid leak around cerebral vessels that have high levels of IE sequestration. Such thrombin-induced effects might therefore be responsible for the IE-associated perivascular pathology seen in CM postmortem.6 The determinants of whether the protein C pathway decompensates and thereby contributes to the development of CM is likely to be related to a combination of host endothelial response36 and parasite binding phenotypes.45

The microvascular-specific coagulopathy described here in CM with retained TM and EPCR in vessels devoid of IE and a normal plasma aPC/F1+2 ratio contrasts with the wide-ranging coagulation abnormalities associated with bacterial sepsis. In bacterial sepsis, loss of protein C receptors occurs in small- and medium-sized vessels24 and is accompanied by global impairment in aPC production, as indicated by a reduced plasma aPC/F1+2 ratio.33 This difference between localized endothelial dysfunction in CM and widespread dysfunction in sepsis is consistent with their respective clinical phenotypes. Bacterial sepsis in children is frequently complicated by gross tissue edema, hypotension, multi-organ failure and global coagulation abnormalities, including purpura fulminans.24 In contrast, while CM in African children is characterized by microvascular thrombosis, tissue swelling and organ compromise of the brain,6 multi-organ involvement such as hypotension or renal failure is rare.12

Like other groups,29,34 we were unable to detect by histology TM in brain samples from our cohort and therefore are uncertain whether it is lost in the brain alongside EPCR. Low levels of TM expression have been demonstrated in cerebral microvessels in other studies on unfixed samples28 and immunostaining.46 Concurrent loss of TM and EPCR in IE-containing cerebral vessels in CM is suggested by increased soluble TM shedding into the CSF, loss of both receptors in subcutaneous tissue, and the simultaneous loss of both receptors in other diseases.24-26 Yet because EPCR is required for aPC-mediated modification of PAR1,22 the pathway dysfunction we suggest would occur irrespective of the presence or absence of cerebral TM.

Our data indicate potential therapeutic targets at the coagulation-inflammation interface for African children with CM. These include reducing thrombin generation with specific thrombin or prothrombinase antagonists, augmenting the protein C pathway with recombinant aPC or TM, and modifying the PAR1/Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor (S1P1) response. Recombinant aPC, strongly advocated as an adjunctive treatment of severe sepsis, has recently been withdrawn due to lack of benefit in follow-up trials.47 Although it remains possible that therapeutic aPC is effective for other pathologies such as CM, loss of endothelial EPCR and the potential for intracranial bleeding are likely to limit efficacy. Downstream therapies directed at PAR1/S1P1 may be preferable. Blockade of PAR1 has been shown to reduce mortality in a murine sepsis model even after the development of severe clinical signs.48 The S1P1 agonist FTY720 decreased mortality and vascular leak in murine CM49 and has been shown to be safe in humans in trials of multiple sclerosis50 in which dysfunction of the protein C pathway in the brain is also implicated.27

In conclusion, we have shown disruption of key endothelial functions in African children with CM, linking several prominent pathogenic features and explaining the cerebral vulnerability of this disease. Although it will be important to discover whether a similar mechanism is implicated in CM in nonimmune adults, targeting the imbalance in this regulatory pathway may lead to the development of effective adjunctive treatments to improve CM outcome.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

For assistance with the clinical study, we thank Steve Kamiza (College of Medicine, Blantyre, Malawi), Eric Borgstein (Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Blantyre, Malawi), Grace Matimati, Patricia Phula, Simon Ewing and the Pediatric Research Ward clinical team (Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Programme and Blantyre Malaria Project), the Department of Paediatrics and Child Health (Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Blantyre, Malawi), and Shakti Ramkissoon, Cheryl Adackapara, and Benjamin Chen (Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA). For technical advice and assistance, we thank Matthew Colin, Muzlifah Haniffa, and Ian Dimmick (Newcastle University, United Kingdom), Gary Ferrell (Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation, Oklahoma City, OK), Dyann Wirth, and Clarissa Valim (Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, MA), David Lalloo (Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, United Kingdom), and Michael Levin (Imperial College, London, United Kingdom).

This work was supported by a Clinical Fellowship from The Wellcome Trust, United Kingdom (C.A.M. and by grants from the NIH (T.E.T., 5R01AI034969-14, and D.A.M.). The Malawi-Liverpool-Wellcome Clinical Research Programme is supported by core funding from The Wellcome Trust.

Authorship

Contribution: C.A.M. designed and performed the research, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper; S.C.W. designed the research and wrote the paper; D.A.M. designed the research and provided technical advice; T.E.T. and M.E.M. designed the clinical study and T.E.T., M.E.M., and K.B.S. supervised its conduct; N.V.C. performed the research; B.F. provided statistical advice and analyzed the data; C.-H.T., C.T.E., and C.D. provided technical advice and C.D. performed the research; R.S.H. and A.G.C. designed the research and wrote the manuscript; and all authors contributed to critical revision of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation has patents granted to C.T.E. and licenses for the isolation of protein C and the use of aPC in the treatment of sepsis and dysfunctional endothelium. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Christopher Moxon, Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, Pembroke Pl, Liverpool L3 5QA United Kingdom; e-mail: cmoxon@liverpool.ac.uk.

![Figure 4. Compensated activation of coagulation in CM. (A) Plasma TAT levels taken on admission in children with (right to left) retinopathy-positive CM (Ret Pos CM, n = 67), retinopathy-negative CM (Ret Neg CM, n = 19), nonmalarial coma (n = 11), uncomplicated malaria (n = 30), mild nonmalarial febrile illness (n = 30), and healthy controls (n = 19). (B) Plasma TAT levels taken on admission in patients with retinopathy-positive CM grouped according to outcome: those who eventually died (fatal [n = 16] and those who survived [nonfatal, n = 51]). (C) Prothrombin time and aPPT (D) in children with (from right to left) Ret Pos CM (n = 69), Ret Neg CM (n = 23), nonmalarial coma (n = 11), uncomplicated malaria (n = 21), mild nonmalarial febrile illness (n = 24), and healthy controls (n = 30). (E) aPC levels in plasma taken on admission in children with (from right to left): Ret Pos CM (n = 92), Ret Neg CM (n = 22), nonmalarial coma (n = 6), uncomplicated malaria (n = 24), mild nonmalarial febrile illness (n = 25), and healthy controls (n = 21). (F) Plasma aPC levels in retinopathy-positive children who eventually died (fatal, n = 16) and those who survived (nonfatal, n = 76). (G) Prothrombin fragment (F1+2)/aPC ratio in the same patients as 4E. (H) Prothrombin fragment levels in fatal and nonfatal retinopathy-positive CM. Horizontal lines indicate geometric means. Significance determined by ANOVA with the Tukey honestly significant difference test test on log-transformed data to adjust for multiple comparison. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/122/5/10.1182_blood-2013-03-490219/4/m_842f4.jpeg?Expires=1765898269&Signature=dUGEOVTEx4W3kGxYX0ZtZCIcHZx0SJ~m1bKhn4LvQBuDibALroOlQ44ihwXOoZ~a1yguUUbtkXCZF0EIh0esEP4pEzwd-Vt5yKMI8fcQt7ByWtY2E2zkwcTnN1pYEVEtkWq69tlhqN3qaZvQl2kAsrvUyMMAHHC5OR9aDXulQCMBAwOpZhrraWHFd~BR9pNJr7xjPNMPDYL-6RwejLmEv05iehSJ1gNtrAFnnsjnppX1uMoDRkh6KW6JW~otQHhSSXX4Mi8yzYBnrEZy8Bhb~cay85o8ZWzQTtCEyyRoT6P9oWoBbaId5s-9xYNX70Lo0BG~J58O5Rw1l9BYSkfTSQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal