Key Points

FGF 2 promotes IM resistance in vitro and in vivo and is overcome by ponatinib, an FGF receptor and ABL kinase inhibitor.

Abstract

Development of resistance to kinase inhibitors remains a clinical challenge. Kinase domain mutations are a common mechanism of resistance in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), yet the mechanism of resistance in the absence of mutations remains unclear. We tested proteins from the bone marrow microenvironment and found that FGF2 promotes resistance to imatinib in vitro. Fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2) was uniquely capable of promoting growth in both short- and long-term assays through the FGF receptor 3/RAS/c-RAF/mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Resistance could be overcome with ponatinib, a multikinase inhibitor that targets BCR-ABL and FGF receptor. Clinically, we identified CML patients without kinase domain mutations who were resistant to multiple ABL kinase inhibitors and responded to ponatinib treatment. In comparison to CML patients with kinase domain mutations, these patients had increased FGF2 in their bone marrow when analyzed by immunohistochemistry. Moreover, FGF2 in the marrow decreased concurrently with response to ponatinib, further suggesting that FGF2-mediated resistance is interrupted by FGF receptor inhibition. These results illustrate the clinical importance of ligand-induced resistance to kinase inhibitors and support an approach of developing rational inhibitor combinations to circumvent resistance.

Introduction

Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) is caused by BCR-ABL, a constitutively active tyrosine kinase derived from the t(9;22) chromosomal translocation. Imatinib (IM) was the first drug designed to inhibit BCR-ABL kinase activity and was initially found to have significant activity in preclinical models.1 Shortly thereafter, it was established as first-line treatment of CML.2 Despite this initial success, it soon became clear that many CML patients developed resistance to IM, frequently as a result of point mutations in BCR-ABL that reduce IM’s ability to bind to its target.3 This suggested that resistant CML continued to be dependent on BCR-ABL activity. Indeed, the more potent second-generation inhibitors nilotinib (NIL) and dasatinib (DAS) were able to overcome IM resistance in many patients,4,5 with the notable exception of the gatekeeper T315I mutation, which blocks access of IM, DAS, and NIL.6 The inhibitor ponatinib was rationally designed to bypass the steric restrictions of the T315I mutation, allowing it to fit in the binding pocket of BCR-ABL,7 and has shown impressive clinical activity in patients with mutated BCR-ABL kinase domain (KD).8,9

In contrast, a subset of CML patients are resistant to IM, DAS, and NIL and do not have mutations of the KD. In these patients, the mechanism of resistance is unclear, and thus there have been no clear strategies to develop novel therapies for these patients. Recent evidence suggests that the bone marrow microenvironment provides a sanctuary for leukemia cells and may provide important survival cues for leukemia cells.10 The bone marrow microenvironment comprises soluble proteins, extracellular matrix, and specialized cells, including fibroblasts, osteoblasts, and endothelial cells, that promote the survival of hematopoietic cells within specialized niches.11 We hypothesized that the marrow microenvironment may be involved in mediating resistance to IM—particularly in the absence of mutations of the BCR-ABL KD—so we tested cytokines, growth factors, and soluble proteins that are expressed by cells in the bone marrow microenvironment for their ability to protect CML cells from IM.

Methods

Cell lines

The human CML cell line K562 was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) and maintained in RPMI1640 media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/mL penicillin/100 µg/mL streptomycin, and 2 mM l-glutamine at 37°C in 5% CO2.

Viability assays

K562 cells were incubated in media supplemented with recombinant cytokines and growth factors obtained from Peprotech (Rocky Hill, NJ) at indicated concentrations. IM was added at 1 μM concentration, unless otherwise specified, and the cells were incubated for 48 hours. Viability was assessed with 3-(4,5 dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium (MTS) reagent: CellTiter 96 AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay from Promega Corporation (Madison, WI).

Long-term resistant cultures

K562 cells were initially resuspended in 10 mL of fresh media at a concentration of 1 × 106 cells/mL. Media was supplemented with fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2), interferon-γ (IFN-γ), granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) at 10 ng/mL as indicated, and 1 μM IM. Media, recombinant protein, and IM were replaced every 2-3 days. Cell viability was evaluated every 2-3 days using Gauva ViaCount reagent and cytometer (Millipore, Billerica, MA).

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors

IM, DAS, NIL, and ponatinib were purchased from LC Laboratories (Woburn, MA). PD173074 and AZD1480 were purchased from Selleck (Houston, TX).

siRNA and kinase inhibitors

The RAPID small interfering RNA (siRNA) library was previously described.12,13 All siRNAs were from Thermo Fisher Scientific Dharmacon RNAi Technologies (Waltham, MA). K562 cells were washed in phosphate-buffered saline, resuspended in siPORT (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) at 1:6 dilution, and electroporated using a square wave protocol (250V, 1.5 seconds, 2 pulses, 0.1-second interval) in a BioRad Gene Pulser XCell (Hercules, CA). After 72 hours, cells were subjected to the MTS assay to assess cell viability and proliferation.

Blocking antibodies

FGF2 was diluted in media at 10 ng/mL and then blocking antibody (Ab) clone bFM-1 (Millipore) was added and incubated for 30 minutes at 37°C before addition of K562 cells and IM. Viability was assessed as described.

Immunoblot analysis

K562 cells were treated as described, washed in phosphate-buffered saline, and lysed in lysis buffer (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) supplemented with Complete protease inhibitor (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail-2 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Equal amounts of protein were fractionated on 4% to 15% Tris-glycine polyacrylamide gels (Criterion gels, Bio-Rad), transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes, and probed with antibodies against pABL, ABL, FGFR3, p FGF receptor (FGFR), p signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3), STAT3, pSTAT5, STAT5, p mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 1/2 (MEK1/2), MEK1/2, pERK1/2, ERK1/2, pS6, and S6 (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA). Antibodies to actin were from Millipore (MAB1501). RAS-guanosine triphosphate (GTP) was evaluated using RAS Activation Assay Kit from Millipore.

Immunohistochemistry

All patient specimens were obtained with informed consent of the patients on protocols approved by the Institutional Review Board of Oregon Health & Science University. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Antigen retrieval was performed by boiling samples in Dako Citrate buffer (10 mM sodium citrate, pH 6.0) for 30 minutes (Dako, Carpinteria, CA). Rabbit polyclonal anti-FGF2 Ab (SC-79) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX) was diluted 1:500 in Dako Ab Diluent with Background Reducing Reagents and incubated overnight at 4°C. The following day, secondary biotinylated anti-rabbit Ab (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA) was added at 1:500 dilution and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature. Secondary Ab was detected using an avidin/biotinylated enzyme conjugate kit (Vectastain ABC kit;Vector Labs) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. The slides were dehydrated and mounted with Permount (VWR, Radnor, PA). Slides were scanned with an Aperio ScanScope AT microscope using ×20 objective (Vista, CA). The FGF2 staining was then quantitated with Aperio ImageScope software using a macro kindly provided by Dr Brian Ruffell in Dr Lisa Coussens’ laboratory at Oregon Health & Science University.

Colony assays

All studies using human cells were approved by the Oregon Health & Science University Institutional Review Board and patients provided written informed consent before study participation. Previously isolated CD34+ cells (immunomagnetic beads; Miltenyi Biotech, Bergisch-Gladbach, Germany) were thawed and cultured overnight in Iscove modified Dulbecco media (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) with 10% BIT9500 (Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, Canada), 10−4 M β-mercaptoethanol, 1 ng/mL G-CSF, 50 pg/mL leukemia inhibitory factor, 0.2 ng/mL granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor, 0.2 ng/mL stem cell factor, 0.2 ng/mL macrophage inflammatory protein 1α, 1 ng/mL interleukin-6 (Stem Cell Technologies), and 100 U/mL penicillin/100 µg/mL streptomycin (Invitrogen). The cells were then plated in Methocult H4534 (Stem Cell Technologies) in triplicate with IM and FGF2 as indicated. Colony forming units–granulocyte macrophage (CFU-GM) colonies were counted after 2 weeks of incubation at 37°C in 5% CO2.

Statistical methods

Graphical and statistical data were generated using either Microsoft Excel or GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). Continuous variables were compared by Student t test for 2 independent samples using Microsoft Excel. Growth curves of K562 cells grown in FGF2 supplemented media and normal media were compared with GraphPad Prism using a 2-way analysis of variance. P < .05 was considered significant.

Results

FGF2 protects CML cells from IM

Selected proteins present in the microenvironment (Agarwal et al, manuscript in preparation) were plated at 3 concentrations: 100 ng/mL, 10 ng/mL, and 1 ng/mL with the CML cell line K562 in the presence of 1 μM IM. Viability was assessed with an MTS assay and the results were ranked according to greatest viability at 100 ng/mL (Figure 1A; supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood Web site). The 2 most protective proteins in this initial assay were FGF2 and FGF1. To confirm these findings, we repeated the assay at lower doses comparing some of the most protective proteins (FGF2, FGF1, and IFN-γ) along with proteins previously reported to be important in mediating resistance in CML including interleukin-6,14 G-CSF,15 granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor,16 and placental-derived growth factor (data not shown).17 We confirmed that FGF2 was the most protective protein in 48-hour culture (Figure 1B).

Microenvironmental screen identifies FGF2 as a protective molecule for K562 cells in the presence of IM; FGF2 promotes long-term K562 outgrowth and IM resistance. (A) K562 cells were added to a 384-well plate containing cytokines, chemokines, growth factors, and small proteins to screen for factors that would promote growth in the presence of 1 μM IM. Viability was measured using MTS reagent and the results sorted according to viability at 100 ng/mL concentration. The highest 2% of values are indicated in red and lowest 2% in white, with gradients indicating subsequent highest and lowest values, respectively. (B) K562 cells were cultured in 10, 1, and 0.1 ng/mL of recombinant proteins plus 1 μM IM. Viability was assessed after 48 hours with MTS reagent and data plotted as percent of the respective untreated control. All wells were plated in triplicate with standard deviation (stdev) indicated in error bars. The red line represents 2 standard deviations of IM-treated K562 cells (11.8%, n = 9). (C) K562 cells were cultured in 1 μM IM alone and with FGF2, IFN-γ, or G-CSF as indicated. Fresh media, IM, and cytokine were replaced every 2-3 days over the indicated time. Viable cells were analyzed using Guava ViaCount. EGF, epidermal growth factor; GM-CSF, granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor; IGF, insulin-like growth factor; IL, interleukin; Neg, negative control; OSM, oncostatin M.

Microenvironmental screen identifies FGF2 as a protective molecule for K562 cells in the presence of IM; FGF2 promotes long-term K562 outgrowth and IM resistance. (A) K562 cells were added to a 384-well plate containing cytokines, chemokines, growth factors, and small proteins to screen for factors that would promote growth in the presence of 1 μM IM. Viability was measured using MTS reagent and the results sorted according to viability at 100 ng/mL concentration. The highest 2% of values are indicated in red and lowest 2% in white, with gradients indicating subsequent highest and lowest values, respectively. (B) K562 cells were cultured in 10, 1, and 0.1 ng/mL of recombinant proteins plus 1 μM IM. Viability was assessed after 48 hours with MTS reagent and data plotted as percent of the respective untreated control. All wells were plated in triplicate with standard deviation (stdev) indicated in error bars. The red line represents 2 standard deviations of IM-treated K562 cells (11.8%, n = 9). (C) K562 cells were cultured in 1 μM IM alone and with FGF2, IFN-γ, or G-CSF as indicated. Fresh media, IM, and cytokine were replaced every 2-3 days over the indicated time. Viable cells were analyzed using Guava ViaCount. EGF, epidermal growth factor; GM-CSF, granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor; IGF, insulin-like growth factor; IL, interleukin; Neg, negative control; OSM, oncostatin M.

We reasoned that short-term improvement in viability may be overcome by longer IM exposure, so we tested the effects of FGF2 in long-term cell culture. K562 cells were cultured with 1 μM IM in media alone or supplemented with 10 ng/mL FGF2. We also tested IFN-γ because it was protective in our short-term assay and G-CSF for comparison. Media, IM, and growth factors were replaced every 2-3 days. After a few weeks, only FGF2-supplemented K562 cells were able to slowly resume growth and expansion, indicating an acquired IM resistance (Figure 1C). Notably, this resistance did not occur immediately but on average took about 3-4 weeks. FGF2-mediated growth was highly significant by 2-way analysis of variance, and resistant cells continued to grow indefinitely in FGF2-supplemented culture.

FGF2 exerts its protective effect via FGFR3

To evaluate the mechanism of FGF2-mediated resistance, we examined the effect of FGFR inhibitors in combination with FGF2 and IM. K562 cells were grown in media alone or with 10 ng/mL FGF2 and exposed to increasing gradients of the selective FGFR inhibitor PD173074 or the JAK/FGFR inhibitor AZD1480. Both inhibitors were able to block FGF2-mediated protection from IM in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 2A-B). There was a modest increase of K562 viability with FGF2 in the absence of IM that was blocked by FGFR inhibition, but PD173074 itself had no adverse effect on K562 viability in the absence of FGF2 (Figures 2 and 3). Similarly, preincubation of FGF2 with blocking antibodies prevented binding and subsequent activation of FGFR, and thus protection from IM (Figure 2C).

FGF2 protection of K562 cells is mediated by FGFR3. K562 cells were cultured in media without and with 10 ng/mL FGF2 and exposed to a titration of FGFR inhibitors. (A) PD173074: 25, 50, or 100 nM or (B) AZD1480: 0.5, 1, or 2 μM and in combination with 1 μM IM as indicated. Viability was measured by MTS assay after 48 hours. Cells not exposed to IM were normalized to untreated K562 cells. IM-treated cells were compared with their respective untreated control (eg, media alone, FGF2, 25 nM PD173074). (C) Blocking FGF2 Ab (Millipore bFM-1) at 100 μg/mL, 10 μg/mL, or 1 μg/mL was added to media with or without 10 ng/mL FGF2 and preincubated for 1 hour at 37°C. K562 cells were then added with or without 1 μM IM and viability measured by MTS. Viability is presented as the percent of untreated control for each condition. (D) K562 cells were electroporated with siRNAs targeting FGFR1, FGFR2, FGFR3, FGFR4, and a nonspecific (NS) control. After 48 hours, the cells the cells were pelleted and resuspended in media with or without FGF2 ± 1 μM IM and viability assessed by MTS after 48 hours. At 48 hours, a portion of the cells were lysed and analyzed by western blot for FGFR3 to evaluate protein expression (lower panel and supplemental Figure 2 for quantitative polymerase chain reaction). *Indicates P < .01 by Student t test. (E) K562 cells were electroporated with pools of siRNAs targeting the tyrosine kinome as described previously12,13 and incubated with 10 ng/mL FGF2 and 1 μM IM. Viability was assessed after 72 hours by MTS; the dark gray horizontal line indicates 2 standard deviations below the mean for all siRNAs. ABL1 and FGFR3 siRNA are denoted as the only 2 siRNA pools that reduced viability below 2 standard deviations.

FGF2 protection of K562 cells is mediated by FGFR3. K562 cells were cultured in media without and with 10 ng/mL FGF2 and exposed to a titration of FGFR inhibitors. (A) PD173074: 25, 50, or 100 nM or (B) AZD1480: 0.5, 1, or 2 μM and in combination with 1 μM IM as indicated. Viability was measured by MTS assay after 48 hours. Cells not exposed to IM were normalized to untreated K562 cells. IM-treated cells were compared with their respective untreated control (eg, media alone, FGF2, 25 nM PD173074). (C) Blocking FGF2 Ab (Millipore bFM-1) at 100 μg/mL, 10 μg/mL, or 1 μg/mL was added to media with or without 10 ng/mL FGF2 and preincubated for 1 hour at 37°C. K562 cells were then added with or without 1 μM IM and viability measured by MTS. Viability is presented as the percent of untreated control for each condition. (D) K562 cells were electroporated with siRNAs targeting FGFR1, FGFR2, FGFR3, FGFR4, and a nonspecific (NS) control. After 48 hours, the cells the cells were pelleted and resuspended in media with or without FGF2 ± 1 μM IM and viability assessed by MTS after 48 hours. At 48 hours, a portion of the cells were lysed and analyzed by western blot for FGFR3 to evaluate protein expression (lower panel and supplemental Figure 2 for quantitative polymerase chain reaction). *Indicates P < .01 by Student t test. (E) K562 cells were electroporated with pools of siRNAs targeting the tyrosine kinome as described previously12,13 and incubated with 10 ng/mL FGF2 and 1 μM IM. Viability was assessed after 72 hours by MTS; the dark gray horizontal line indicates 2 standard deviations below the mean for all siRNAs. ABL1 and FGFR3 siRNA are denoted as the only 2 siRNA pools that reduced viability below 2 standard deviations.

Long-term IM resistance occurs via FGF2-dependent or -independent mechanisms, and FGF2-dependent resistance can be overcome by FGFR inhibition. (A-D) K562 cells with and without 10 ng/mL FGF2 and 2 long-term IM-resistant K562 outgrowths in 10 ng/mL FGF2 (Figure 1, denoted as K1 and K2) were exposed to a matrix of an IM gradient (0, 0.01, 0.04, 0.1, 0.4, 1.1, 3.3, 10 μM) combined with the FGFR inhibitor PD173074 (PD; 0, 0.001, 0.004, 0.01, 0.04, 0.11, 0.33, 1 μM). Viability was measured after 48 hours and average viability graphed as a surface plots using untreated as reference with colors denoting 20% increments. (E-H) Viability from surface plots indicating drug curves to IM (IM) alone, PD173074 alone, and combination to highlight synergy. Calculation of the combination index for relevant drug concentrations is included in supplemental Table 1. (I-L) K562 cells with and without 10 mg/mL FGF2, K1, and K2 in 10 mg/mL FGF2 were exposed to indicated concentrations of IM, DAS, NIL, and ponatinib (PON). Viability was measured after 48 hours. All experiments were done in triplicate with average viability scaled to untreated condition (100%). Error bars represent standard deviation.

Long-term IM resistance occurs via FGF2-dependent or -independent mechanisms, and FGF2-dependent resistance can be overcome by FGFR inhibition. (A-D) K562 cells with and without 10 ng/mL FGF2 and 2 long-term IM-resistant K562 outgrowths in 10 ng/mL FGF2 (Figure 1, denoted as K1 and K2) were exposed to a matrix of an IM gradient (0, 0.01, 0.04, 0.1, 0.4, 1.1, 3.3, 10 μM) combined with the FGFR inhibitor PD173074 (PD; 0, 0.001, 0.004, 0.01, 0.04, 0.11, 0.33, 1 μM). Viability was measured after 48 hours and average viability graphed as a surface plots using untreated as reference with colors denoting 20% increments. (E-H) Viability from surface plots indicating drug curves to IM (IM) alone, PD173074 alone, and combination to highlight synergy. Calculation of the combination index for relevant drug concentrations is included in supplemental Table 1. (I-L) K562 cells with and without 10 mg/mL FGF2, K1, and K2 in 10 mg/mL FGF2 were exposed to indicated concentrations of IM, DAS, NIL, and ponatinib (PON). Viability was measured after 48 hours. All experiments were done in triplicate with average viability scaled to untreated condition (100%). Error bars represent standard deviation.

Because multiple FGFRs are expressed on K562 cells—and were even initially cloned from K562 cells18,19 —we used siRNA pools targeting FGFR1-4 to knockdown expression of each receptor and then treated cells with IM in the presence or absence of FGF2. FGF2 protected K562 cells from IM in the context of FGFR1, FGFR2, and FGFR4 silencing; however, K562 cells treated with siRNA targeting FGFR3 did not exhibit FGF2-mediated protection, indicating that FGF2 binds FGFR3 to mediate this protective effect (Figure 2D; supplemental Figure 2). Further confirmation that FGFR3 was specifically activated and responsible for protection was obtained by using siRNAs targeting the tyrosine kinome.12,13 In the presence of FGF2 and IM, siRNAs targeting both ABL1 and FGFR3 significantly decreased viability (Figure 2E), providing genetic evidence that BCR-ABL and FGFR3 are critical survival pathways in the presence of IM and FGF2. As expected, in the absence of FGF2 and IM, siRNA targeting ABL1 was the only siRNA that significantly reduced viability of K562 cells (supplemental Figure 2).

Long-term resistance to IM is overcome by inhibition of both FGFR and ABL

We next turned our attention to the long-term resistant cultures depicted in Figure 1C, henceforth denoted as K1-K5. Because the resistant cells were grown in continuous 1 μM IM concentration, we wanted to evaluate a range of both IM and PD173074 concentrations to test for synergy of these inhibitors. We created a 64-well matrix with an IM gradient on 1 axis overlaid with a PD173074 gradient on the other, and then evaluated viability in triplicate after 48 hours of treatment. Viability of long-term cultures was assessed 48 hours after fresh media, FGF2, and IM were replaced. The results are depicted as surface plots (Figure 3A-D), and the data are presented again in linear form to highlight the response to each drug individually and in fixed combination (Figure 3E-H).

As anticipated, unmanipulated K562 cells respond uniformly to increasing doses of IM, and PD173074 had no effect on their growth (Figure 3A,E). When K562 cells were cultured with FGF2 and IM for 48 hours, there was an expected increase in viability at lower concentrations of IM (∼1 μM), which was attenuated by FGFR inhibitor (Figure 3B,F). Of the long-term cultures, 4 of 5 developed dependence on FGF2 signaling (K1 shown, similar data for K3 and K4 in supplemental Figure 3) and became sensitive to PD173074, yet profoundly insensitive to IM, even at high concentrations (Figure 3C,G). The combination of IM and PD173074 was highly synergistic in these long-term cultures (supplemental Table 1), indicating that both BCR-ABL and FGFR3 are important for survival when FGF2 is present. This was also confirmed genetically with siRNA (supplemental Figure 2). In contrast, a single long-term culture, K2, remained sensitive to IM, but only at higher doses than the parental K562 cells (Figure 3D,H). K2 was far less sensitive to FGFR inhibition alone but there was synergy between the 2 compounds at higher doses of IM (supplemental Table 1).

Ponatinib is a recent ABL inhibitor that was rationally designed to circumvent the gatekeeper T315I mutation,7 yet ponatinib is also a multikinase inhibitor with activity against FGFR.20,21 Therefore, we predicted that ponatinib would be uniquely effective against FGF2-dependent long-term cultures (K1, K3-K5). We compared the ABL inhibitors IM, DAS, NIL, and ponatinib (Figure 3I-L) and found that ponatinib was indeed the only drug effective against FGF2-dependent cultures (K1 shown, K3 and K4 in supplemental Figure 3). Notably, ponatinib only became effective around 10 nM, which is near the reported half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of ponatinib against cell lines with FGFR overexpression.20 In contrast, the IC50 of ponatinib for BCR-ABL is much lower and comparable to DAS.7 Thus, ponatinib efficacy cannot be rationalized solely by its inhibition of BCR-ABL, which occurs at least 10-fold lower (Figure 3I) than the doses of efficacy noted here (between 10 and 100 nM).

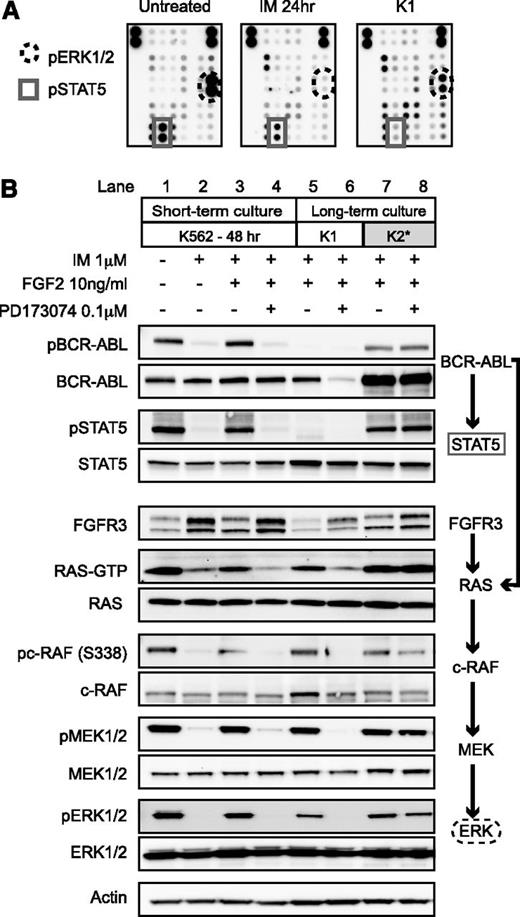

FGF2 reactivates the RAS/c-RAF/mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway

We then analyzed potential downstream signaling pathways using a phospho-kinase array to determine the mechanism of survival in these long-term cultures. In parental K562 cells, IM decreased both phospho-STAT5 and phospho-ERK1/2 signal (Figure 4A) consistent with the known regulation of these pathways by BCR-ABL.22 In FGF2-dependent cultures, phospho-STAT5 remained suppressed—consistent with inhibition of BCR-ABL by IM—yet phospho-ERK1/2 was partially restored. This suggested that activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway was important for survival. We did not identify activation of any other signaling pathways using the phospho array.

FGF2-dependent resistance is mediated by activation of FGFR-RAS-RAF-MEK-ERK pathway, whereas FGF2-independent resistance is mediated by reactivation of BCR-ABL. (A) Untreated K562 cells, K562 cells treated for 24 hours with 1 μM IM, and K1 cells after 1 month of culture in 10 ng/mL FGF2 and 1 μM IM were lysed and used to probe a human phospho-kinase array (Proteome Profiler, RnD). The dots corresponding to pERK1/2 and pSTAT5 are indicated. (B) K562 cells were treated for 48 hours in the indicated conditions under short-term culture conditions. The long-term cultured cells were grown continuously in IM and FGF2 as described in Figure 1. Cell lysates were collected 48 hours after replacement of media, FGF2, and inhibitor (IM and PD173074). The cells were then lysed as described with western blot analysis as in “Methods.” RAS-GTP was evaluated at 24 hours using immunoprecipitation.

FGF2-dependent resistance is mediated by activation of FGFR-RAS-RAF-MEK-ERK pathway, whereas FGF2-independent resistance is mediated by reactivation of BCR-ABL. (A) Untreated K562 cells, K562 cells treated for 24 hours with 1 μM IM, and K1 cells after 1 month of culture in 10 ng/mL FGF2 and 1 μM IM were lysed and used to probe a human phospho-kinase array (Proteome Profiler, RnD). The dots corresponding to pERK1/2 and pSTAT5 are indicated. (B) K562 cells were treated for 48 hours in the indicated conditions under short-term culture conditions. The long-term cultured cells were grown continuously in IM and FGF2 as described in Figure 1. Cell lysates were collected 48 hours after replacement of media, FGF2, and inhibitor (IM and PD173074). The cells were then lysed as described with western blot analysis as in “Methods.” RAS-GTP was evaluated at 24 hours using immunoprecipitation.

FGFR3 and downstream signaling pathways were analyzed by western blot. As expected, K562 cells treated with IM have reduced phospho-BCR-ABL, phospho-STAT5, RAS-GTP, phospho-c-RAF, phospho-MEK, and phospho-ERK (Figure 4B, lane 2 compared with lane 1). Surprisingly, the addition of FGF2 in short-term culture was able to restore some phosphorylation of BCR-ABL and STAT5. Inhibition by PD173074 reversed this effect (Figure 4B, lanes 3 and 4). In contrast, phosphorylation of BCR-ABL and STAT5 were absent in long-term FGF2-dependent culture K1 (Figure 4B, lane 5), whereas RAS-GTP and downstream kinases were phosphorylated. The amount of total FGFR3 protein was also reduced, consistent with proteolysis and internalization of the FGFR3 receptor after binding by FGF2.23 Addition of PD173074 specifically inhibited RAS/c-RAF/MEK/ERK, indicating dependence of this pathway on FGF2-FGFR3 stimulation (Figure 4B, lane 6 compared with lane 5).

In contrast, in the single K2 culture, there was restoration of phospho-BCR-ABL and downstream phospho-STAT5 signaling despite 1 μM IM (Figure 4B, lane 7). RAS and downstream pathways were reactivated, but this did not occur downstream of FGFR3 because there was no relation to PD173074 treatment (Figure 4B, lane 8). Because KD mutations are a well-described mechanism of resistance in CML,3,24 we sequenced the ABL KD but found no mutations in K2 or any of the long-term cultures (data not shown). We also sequenced the FGFR3 receptor and found no activating mutations to explain the development of resistance. Of note, the total amount of BCR-ABL protein also increased in K2, yet messenger RNA levels did not dramatically increase in these cells by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (data not shown).

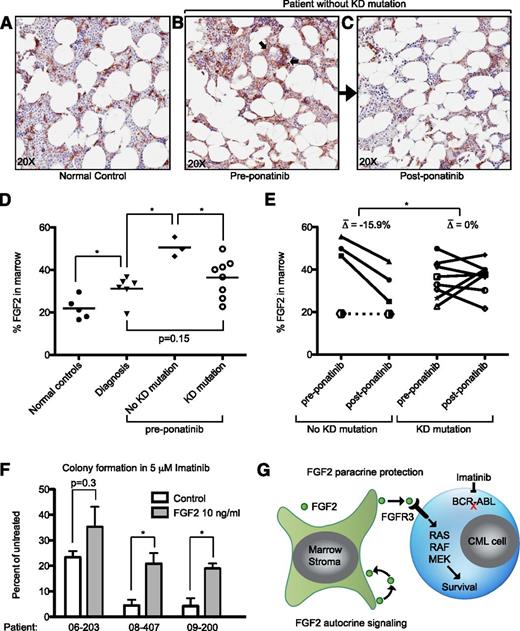

FGF2 is increased in resistant patients without KD mutations and decreases concurrently with response to ponatinib

Ponatinib was recently evaluated in a phase I clinical trial and found to be surprisingly effective in patients without KD mutations.8,9 We suspected that if FGF2 promoted resistance in these patients, it would be relatively increased in bone marrow samples compared with ponatinib-responsive patients with KD mutations. We collected available bone marrow biopsies from patients on the ponatinib clinical trial at our institution and evaluated FGF2 expression by immunohistochemistry (IHC). Most patients were previously treated with multiple ABL inhibitors and the majority responded to ponatinib treatment, with the exception of 1 patient who only had a transient response to ponatinib and is presented separately (Table 1). Bone marrow samples from patients undergoing joint replacement surgery were used as normal controls. The FGF2 staining was quantified using Aperio ImageScope software (supplemental Figure 5).

Patient characteristics studied by IHC

| Age . | Gender . | KD mutation . | Previous TKIs . | Prior years of therapy . | %FGF2 preponatinib . | %FGF2 postponatinib . | Δ . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 56 | M | None | IM, DAS | 3 | 49.8 | 35.1 | −14.7 |

| 67 | M | None | IM, DAS, NIL | 2 | 46.4 | 24.9 | −21.5 |

| 31 | M | None | IM, DAS | 3 | 55.4 | 43.8 | −11.7 |

| 54 | M | L248V | IM, DAS, NIL | 2 | 26.6 | 40.0 | 13.4 |

| 68 | M | F317L/F359V | IM, DAS, NIL | 2 | 43.0 | 46.9 | 3.9 |

| 62 | M | F359V/M244V | IM, DAS, NIL, BOS | 2 | 36.6 | 30.2 | −6.5 |

| 70 | F | F359C | IM, NIL | 4 | 40.1 | 37.6 | −2.5 |

| 47 | M | T315I | IM, DAS | 3 | 22.7 | 37.6 | 15.0 |

| 53 | M | T315I | IM, DAS | 4 | 41.3 | 36.8 | −4.5 |

| 45 | M | T315I | IM, DAS | 3 | 30.6 | 21.6 | −9.1 |

| 59 | F | T315I | IM, DAS | 4 | 49.8 | 40.0 | −9.8 |

| Nonresponder | |||||||

| 37 | F | None | IM, DAS, NIL | 4 | 19.2 | 19 | 0.2 |

| Age . | Gender . | KD mutation . | Previous TKIs . | Prior years of therapy . | %FGF2 preponatinib . | %FGF2 postponatinib . | Δ . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 56 | M | None | IM, DAS | 3 | 49.8 | 35.1 | −14.7 |

| 67 | M | None | IM, DAS, NIL | 2 | 46.4 | 24.9 | −21.5 |

| 31 | M | None | IM, DAS | 3 | 55.4 | 43.8 | −11.7 |

| 54 | M | L248V | IM, DAS, NIL | 2 | 26.6 | 40.0 | 13.4 |

| 68 | M | F317L/F359V | IM, DAS, NIL | 2 | 43.0 | 46.9 | 3.9 |

| 62 | M | F359V/M244V | IM, DAS, NIL, BOS | 2 | 36.6 | 30.2 | −6.5 |

| 70 | F | F359C | IM, NIL | 4 | 40.1 | 37.6 | −2.5 |

| 47 | M | T315I | IM, DAS | 3 | 22.7 | 37.6 | 15.0 |

| 53 | M | T315I | IM, DAS | 4 | 41.3 | 36.8 | −4.5 |

| 45 | M | T315I | IM, DAS | 3 | 30.6 | 21.6 | −9.1 |

| 59 | F | T315I | IM, DAS | 4 | 49.8 | 40.0 | −9.8 |

| Nonresponder | |||||||

| 37 | F | None | IM, DAS, NIL | 4 | 19.2 | 19 | 0.2 |

BOS, bosutinib; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

Bone marrow biopsies from patients who responded to ponatinib were evaluated both before therapy and after response to ponatinib. A single patient who developed resistance to ponatinib within 6 months of therapy is shown for comparison. The clinical characteristics are listed as well as the quantitation of the FGF2 present in the marrow by Aperio ImageScope software (supplemental Figure 5).

Consistent with previous reports, we found that FGF2 in normal marrow is expressed primarily in the supportive marrow stromal cells (Figure 5A).25,26 Bone marrow samples from CML patients at diagnosis had a modest but statistically significant increase in FGF2 staining compared with normal controls (Figure 5D). Ponatinib-responsive patients without KD mutations had increased FGF2 in their marrow compared with patients with mutations (P = .033). Qualitatively, FGF2 was increased in supportive stromal cells, but also present in hematopoietic progenitors (arrows, Figure 5B). The presence of FGF2 in some CD45+ hematopoietic cells was confirmed with immunofluorescence (supplemental Figure 7). Interestingly, ponatinib treatment decreased marrow FGF2 staining concurrently with clinical response to ponatinib (Figure 5B-C as representative examples), and FGF2 returned to a predominantly stromal localization, similar to normal controls. This decrease was statistically significant in comparison with ponatinib-responsive patients with KD mutations (Figure 5E). To further analyze the protective effects of FGF2 in primary cells, we plated CML CD34+ cells in methocult in the presence of FGF2 and IM. We found that at 5 μM IM, FGF2 10 ng/mL was able to increase CFU-GM colony number in all samples tested. To normalize for the variable response to IM between patient samples, we evaluated the average increase in colony number promoted by FGF2, which was statistically significant (P = .016).

FGF2 is increased in the bone marrow of patients without KD mutations and decreases with ponatinib treatment. Bone marrow core biopsies obtained from normal controls (surgical joint replacement patients), CML patients at diagnosis, tyrosine kinase inhibitor resistant patients before ponatinib therapy (pre-ponatinib), and responsive patients post-ponatinib were collected and evaluated for FGF2 by IHC as described in “Methods.” Representative images of (A) normal control, (B) pre-ponatinib marrow of a patient without KD mutation, and (C) the same patient post-ponatinib. FGF2 is normally expressed in marrow stroma (A); arrows indicate nonstromal areas of increased FGF2 in resistant patients (B). (D) IHC images from normal controls, patients at diagnosis, and pre-ponatinib patients who responded to ponatinib (with and without KD mutations) were analyzed with Aperio ImageScope software to quantify FGF2 staining. The line indicates the median value. Statistically significant differences were evaluated using a 2-tailed Student t test. (E) Paired IHC analysis of pre- and post-ponatinib bone marrow of patients treated with ponatinib (same as D). Patients without KD mutations had an average decrease of 15.9% in FGF2 staining, whereas patients with KD mutations were more variable. The differences pre- and post-ponatinib were analyzed by the 2-tailed Student t test for significance. A single patient without KD mutations who failed IM, DAS, NIL, and ponatinib is plotted with a dotted line for comparison (see Table 1). (F) CD34+ cells from newly diagnosed CML patients were resuspended in methocult H4534 ± FGF2 10 ng/mL and ± 5 μM IM. Cells were plated in triplicate, cultured for 14 days, and then CFU-GM colonies were counted. The data are presented as the percent of untreated control (control or FGF2). The differences between control and FGF2 were analyzed by 2-tailed Student t test for significance. *P < .05. (G) Model of FGF2 paracrine protection of CML cells based upon data in this article and previous publications regarding FGF2 autocrine/paracrine stromal cell signaling.44,45

FGF2 is increased in the bone marrow of patients without KD mutations and decreases with ponatinib treatment. Bone marrow core biopsies obtained from normal controls (surgical joint replacement patients), CML patients at diagnosis, tyrosine kinase inhibitor resistant patients before ponatinib therapy (pre-ponatinib), and responsive patients post-ponatinib were collected and evaluated for FGF2 by IHC as described in “Methods.” Representative images of (A) normal control, (B) pre-ponatinib marrow of a patient without KD mutation, and (C) the same patient post-ponatinib. FGF2 is normally expressed in marrow stroma (A); arrows indicate nonstromal areas of increased FGF2 in resistant patients (B). (D) IHC images from normal controls, patients at diagnosis, and pre-ponatinib patients who responded to ponatinib (with and without KD mutations) were analyzed with Aperio ImageScope software to quantify FGF2 staining. The line indicates the median value. Statistically significant differences were evaluated using a 2-tailed Student t test. (E) Paired IHC analysis of pre- and post-ponatinib bone marrow of patients treated with ponatinib (same as D). Patients without KD mutations had an average decrease of 15.9% in FGF2 staining, whereas patients with KD mutations were more variable. The differences pre- and post-ponatinib were analyzed by the 2-tailed Student t test for significance. A single patient without KD mutations who failed IM, DAS, NIL, and ponatinib is plotted with a dotted line for comparison (see Table 1). (F) CD34+ cells from newly diagnosed CML patients were resuspended in methocult H4534 ± FGF2 10 ng/mL and ± 5 μM IM. Cells were plated in triplicate, cultured for 14 days, and then CFU-GM colonies were counted. The data are presented as the percent of untreated control (control or FGF2). The differences between control and FGF2 were analyzed by 2-tailed Student t test for significance. *P < .05. (G) Model of FGF2 paracrine protection of CML cells based upon data in this article and previous publications regarding FGF2 autocrine/paracrine stromal cell signaling.44,45

Discussion

Activation of FGFRs is known to be a driver in numerous malignancies, including FGFR1 fusions in 8p myeloproliferative neoplasms,27,28 t(4;14) translocation with FGFR3 upregulation in multiple myeloma,29,30 FGFR3 mutations in bladder carcinoma,31 and most recently FGFR1/FGFR3 fusions in glioblastoma.32 However, it is becoming more apparent that ligand activation of FGFR is also an important mechanism of resistance to kinase inhibitors. Autocrine secretion of FGF2 and activation of FGFR1 was recently reported to promote resistance to gefitinib in lung cancer cell lines,33,34 and activation of FGFR3 by either exogenous FGF2 or FGFR3 activating mutations in melanoma cell lines was shown to promote resistance to B-RAF inhibitors.35 A recent screen tested the ability of secreted ligands to promote resistance to kinase inhibitors in multiple cell lines and found that FGF2, hepatocyte growth factor, and neuregulin 1 were the most “broadly active” ligands,36 defining a class of ligands that can drive resistance to kinase inhibitors.

FGF2 was not just protective in short-term culture, but, more importantly, FGF2 effectively promoted IM resistance in long-term culture as well (Figure 1). The development of IM resistance took about 1 month, suggesting that either a small subpopulation of cells was capable of using FGF2 as a growth molecule and/or a genetic/epigenetic event was required to resume growth in the presence of FGF2. Most of the long-term cultures (K1, K3-K5) became dependent on FGF2-FGFR3 signaling, and as a result were very sensitive to PD173074 treatment (Figure 3) or removal of FGF2 ligand (data not shown). However, a single long-term culture, K2, was able to restore BCR-ABL signaling in the presence of FGF2 and 1 μM IM, and had increased BCR-ABL protein (Figure 4). Of note, the K2 long-term culture was sensitive to FGFR inhibitors at earlier time points during outgrowth (data not shown), suggesting that FGF2 can also act indirectly as a bridge to reactivation of BCR-ABL, although notably this did not occur through mutation of BCR-ABL itself.

FGF2 is produced by bone marrow stromal cells (Figure 5) and plays an active role in hematopoiesis in vitro.37-40 FGF2 is thought to be secreted from stromal cells into the extracellular matrix where it binds to proteoglycans and promotes hematopoiesis.41 We found that FGF2 was significantly increased in the bone marrow of patients without KD mutations who subsequently responded to ponatinib treatment (Figure 5). Most of the increased FGF2 in these patients was localized in stromal cells and thus it is likely that FGF2 acts in a paracrine manner, similar to other reported models of ligand-induced resistance.42 In support of the paracrine model, we did not find any increased production of FGF2 in long-term resistant K562 cultures. However, by immunofluorescence, there was some detectable FGF2 in some hematopoietic cells themselves (Figure 5B; supplemental Figure 7), which could either be internalized FGF2 from adjacent stroma or produced by the cells themselves, so we cannot formally exclude an autocrine mechanism in patients.

The events that trigger increased expression of FGF2 in the marrow are not yet clear, but recent studies suggest a potential mechanism. FGF2 knockout mice were initially described to have a mild phenotype with respect to normal hematopoiesis,43 but recent studies have identified FGF2-FGFR signaling as critical for stress hematopoiesis.44-46 In stress hematopoiesis, FGF2 stimulates expansion of both supportive marrow stromal cells and hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells to regenerate the marrow. There is evidence that stress hematopoiesis is a frequent event in CML, because up to 35% of CML patients treated with IM (and newer agents) develop transient cytopenias.47 In contrast, cytopenias are far less prominent in IM-treated patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumors,48 suggesting that this is not purely a drug effect. We examined FGF2 in the marrow of newly diagnosed CML patients treated with IM and found a highly variable, but consistent increase in FGF2 from marrow biopsies taken 6-18 months after initiation of IM (supplemental Figure 6). We suspect that FGF2 likely decreases in most patients as they return to normal marrow homeostasis and has no clinical impact. However, we propose that in some patients a sustained feed-forward FGF2 expression can promote FGF2 expression in stromal cells in an autocrine manner and survival of CML cells in a paracrine manner (the CML cells themselves may induce FGF2 expression), eventually leading to overt IM resistance (Figure 5G). In this proposed model, the normal regeneration of the marrow after IM treatment is hijacked by CML cells, similar to what has been described in other malignancies.49 Ponatinib overcomes FGF2-mediated resistance and also interrupts the feed-forward FGF2 loop in the stroma, leading to a normalization of FGF2 expression (Figure 5C,E).

Of the 4 CML patients without KD mutations that we evaluated, 3 had a major cytogenetic response to ponatinib and 1 developed resistance within 6 months. Notably, the patient who did not respond to ponatinib did not have increased marrow FGF2, and there was no change in FGF2 with ponatinib treatment (Table 1), suggesting that additional mechanisms can drive resistance that are not targeted by ponatinib, potentially even other molecules from the microenvironment.14-17,50 In the recent phase I and II ponatinib trials, an impressive 62% and 49% of patients without detectable KD mutations achieved a major cytogenetic response.8,9 Taken together with our data, this suggests that FGF2-mediated resistance potentially accounts for a substantial number of resistant patients. Although ponatinib is clinically effective for these patients, the recent discovery of serious arterial thrombotic events in 11.8% of patients9 prompted the US Food and Drug Administration to suspend sales of ponatinib, and clinical trials were put on hold. The mechanism of increased thrombotic events remains unclear; however, this makes rational combinations of selective kinase inhibitors (such as ABL and FGFR inhibitors) an attractive option to treat patients without T315I mutations and avoid toxicity of multikinase inhibitors.

Our results also provide a strong rationale to define the critical ligand-RTK pathways of resistance in other kinase-driven malignancies. This is of particular clinical relevance in the case of protective ligands such as FGF2 and hepatocyte growth factor, because effective inhibitors51,52 are available to interrupt these survival signals, and many more are in development. In comparison with CML, malignancies driven by activated kinases such as FLT3, HER2, B-RAF, and epidermal growth factor receptor tend to have an initial response to kinase inhibitors, but the majority of patients develop resistance.53-58 Compared with CML, mutations of the KD tends to be a less frequent mechanism of resistance in other malignancies, and ligand-RTK pathways are thus more likely to mediate resistance. Identification of critical ligand-RTK pathways of resistance has the potential to rationally develop combinations of kinase inhibitors that circumvent resistance. This is critical if we are to achieve durable responses, akin to that of CML, in malignancies that routinely develop resistance to kinase inhibitors.

The online version of the article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank C. Tognon and members of the B.J.D. laboratory for helpful discussions and A. Agarwal for the cytokine plate.

This publication was supported by grants from the Oregon Clinical and Translational Research Institute (KL2TR000152) (E.T.) from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences at the National Institutes of Health, the American Society of Hematology Research Training Award for Fellows (E.T.), and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (B.J.D.).

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Authorship

Contribution: E.T. designed experiments, conducted experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript; N.J.-S. helped design experiments and analyzed data; A.A. analyzed data; J.D. obtained biopsy samples and interpreted results; I.E. performed experiments; J.M. performed IHC; J.W.T., M.W., and B.J.D. analyzed data; and all authors discussed results and reviewed the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Brian J. Druker, Division of Hematology & Medical Oncology, Knight Cancer Institute, Oregon Health & Science University, 3181 SW Sam Jackson Park Rd, Portland, OR 97239; e-mail: drukerb@ohsu.edu.