Key Points

The total number of somatic mutations was inversely correlated with survival and risk of leukemic transformation in MPN.

The great majority of somatic mutations were already present at MPN diagnosis, and very few new mutations were detected during follow-up.

Abstract

Myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) are a group of clonal disorders characterized by aberrant hematopoietic proliferation and an increased tendency toward leukemic transformation. We used targeted next-generation sequencing (NGS) of 104 genes to detect somatic mutations in a cohort of 197 MPN patients and followed clonal evolution and the impact on clinical outcome. Mutations in calreticulin (CALR) were detected using a sensitive allele-specific polymerase chain reaction. We observed somatic mutations in 90% of patients, and 37% carried somatic mutations other than JAK2 V617F and CALR. The presence of 2 or more somatic mutations significantly reduced overall survival and increased the risk of transformation into acute myeloid leukemia. In particular, somatic mutations with loss of heterozygosity in TP53 were strongly associated with leukemic transformation. We used NGS to follow and quantitate somatic mutations in serial samples from MPN patients. Surprisingly, the number of mutations between early and late patient samples did not significantly change, and during a total follow-up of 133 patient years, only 2 new mutations appeared, suggesting that the mutation rate in MPN is rather low. Our data show that comprehensive mutational screening at diagnosis and during follow-up has considerable potential to identify patients at high risk of disease progression.

Introduction

Myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) are a group of stem cell disorders characterized by aberrant hematopoietic proliferation and an increased tendency toward leukemic transformation. MPNs comprise 3 major subgroups: polycythemia vera (PV), essential thrombocythemia (ET), and primary myelofibrosis (PMF). An acquired mutation in JAK2 (JAK2 V617F) is present in the majority of MPN patients.1-4 Although JAK2 mutations have been shown to be the phenotypic drivers in MPN, there is evidence of clonality and mutational events preceding the acquisition of JAK2 V617F.5-8 An increasing number of mutations in genes distinct from JAK2 have been identified in patients with MPN. These include mutations in epigenetic modifiers, such as TET2,8 DNMT3A,9 ASXL1,10 and EZH2,11 and genes involved in hematopoietic signaling (reviewed in Vainchenker et al12 ). Very recently, recurrent mutations in the calreticulin gene (CALR) have been reported in ET and PMF by 2 next-generation sequencing (NGS) whole-exome studies.13,14 In addition, novel recurrent mutations occurring at low frequencies have been also found in CHEK2, SCRIB, MIR662, BARD1, TCF12, FAT4, DAP3, and POLG.14,15 Mutations in TP53, TET2, SH2B3, and IDH1 are more frequently observed in leukemic blasts from transformed MPN patients, suggesting a role for these gene mutations in leukemic transformation.16-19 However, so far only mutations in ASXL1 and NRAS have been shown to be of prognostic value in patients with PMF.15,20

Using targeted NGS to search for mutations in 104 cancer-related genes, we have defined the mutational profile of a cohort of 197 MPN patients and dissected the temporal order of acquisition and clonal architecture of mutational events. We further analyzed the impact of the somatic mutations on clinical outcome. We provide evidence that most somatic mutations were present already at MPN diagnosis. In addition, we show that somatic mutations in TP53 and TET2 are associated with decreased overall survival and increased risk for leukemic transformation. Importantly, mutations in TP53 were present for several years in the chronic MPN phase at a low allelic burden, whereas after loss of the wild-type (WT) TP53 allele, the clone rapidly expanded, resulting in leukemic transformation.

Methods

Patient cohort

The collection of blood samples and clinical data was performed at the study center in Basel, Switzerland and approved by the local Ethics Committees (Ethik Kommission Beider Basel). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The diagnosis of MPN was established according to the revised criteria of the World Health Organization.21 Table 1 provides clinical data of the patients included in our study.

Clinical characteristics of the MPN patients at diagnosis

| Diagnosis . | PV . | ET . | PMF . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 94 | 69 | 34 |

| % female | 51 | 67 | 26 |

| Average age at diagnosis (range), y | 58 (18-87) | 51 (21-86) | 61 (21-86) |

| Average time of follow-up, mo | 92 | 56 | 49 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) average (range) | 181 (148-225) | 141 (78-225) | 126 (90-161) |

| Platelets (109/L) average (range) | 554 (90-1487) | 994 (452-1983) | 635 (16-1677) |

| Leukocytes (109/L) average (range) | 12 (4-39) | 9 (5-17) | 11 (5-27) |

| Neutrophils (109/L) average (range) | 9 (2-36) | 6 (3-16) | 8 (3-21) |

| Transformation to secondary myelofibrosis | 4 (4%) | 1 (1%) | NA |

| Transformation to AML | 3 (3%) | 2 (3%) | 2 (6%) |

| Diagnosis . | PV . | ET . | PMF . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 94 | 69 | 34 |

| % female | 51 | 67 | 26 |

| Average age at diagnosis (range), y | 58 (18-87) | 51 (21-86) | 61 (21-86) |

| Average time of follow-up, mo | 92 | 56 | 49 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) average (range) | 181 (148-225) | 141 (78-225) | 126 (90-161) |

| Platelets (109/L) average (range) | 554 (90-1487) | 994 (452-1983) | 635 (16-1677) |

| Leukocytes (109/L) average (range) | 12 (4-39) | 9 (5-17) | 11 (5-27) |

| Neutrophils (109/L) average (range) | 9 (2-36) | 6 (3-16) | 8 (3-21) |

| Transformation to secondary myelofibrosis | 4 (4%) | 1 (1%) | NA |

| Transformation to AML | 3 (3%) | 2 (3%) | 2 (6%) |

NA, not applicable.

Illumina library preparation and target region capture

A total of 500 ng of granulocyte DNA derived from the most recent available follow-up samples of the patients was fragmented using Fragmentase (New England Biolabs), resulting in an average fragment size of ∼250. The fragmented library was purified using Agencourt AMPure XP beads. Following purification, the library was end-repaired and adenylated (both enzymes from Bioo Scientific), and after each of those steps, the library was purified using Agencourt AMPure XP beads. Finally, patient-specific barcoded adapters were ligated (NEXTflex, Bioo Scientific; 48 different ones in total) and divided into duplicate samples. Subsequently, adaptor-ligated DNA from 48 patients, each assigned with a different barcode, was pooled equimolarly in duplicate tubes.

Bait design and target capture

Capture of target regions was performed using an Agilent SureSelect custom design including the targeted exons ±50 bp of flanking regions with a total size of ∼0.44 Mb. Enrichment was performed using the provided Agilent protocol and capture was performed for 72 hours. Postenrichment polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed for 10 cycles.

Illumina sequencing and sequencing analysis

Paired-end 100-bp cycle sequencing of the captured libraries was performed using an Illumina HiSeq2000. Demultiplexed samples were mapped and analyzed using the CLC genomics workbench. Mapping was performed using a mismatch cost of 2 and insertion and deletion cost of 3 with a length fraction 0.7 and similarity fraction of 0.8. For mutational calling, the quality-based variant detection was used, using a neighborhood radius of 5, maximum gap and mismatch count of 2, minimum neighborhood phred quality of 25, and minimum central quality of 30. Minimum coverage of called regions was set at 20, and minimum variant frequency was set to 5%. Only nonsynonymous mutations were further pursued, whereas splice-site mutations were determined using the predict splice-site effect module. Average coverage of targeted regions was performed using the coverage analysis module and including only the targeted exons and not the flanking regions. Targets consistently having no coverage are displayed in supplemental Figure 2H, available on the Blood Web site.

To assess copy number alterations, the RNA-sequencing analysis module was used, and expression value was calculated using reads per kilobase per million. Statistical analysis was performed on proportions, and as references 5 normal controls were pooled. Genes deviating with >30% in expression value and with a P value of <.01 were considered as candidate regions.

Validation of candidate mutations

Candidate mutations observed in the Illumina screen were validated using the Ion Torrent PGM platform. Amplicons covering the regions of interest were designed with an amplicon length of 150 to 250. Sequencing adapters (IonXpress) were ligated to the amplicons using the IonXpress protocol. Final libraries were sequenced with 200-bp read length on a 318 chip. Mutation calling was performed using the torrent suite variant called using the somatic settings. A mutation was called somatic when the mutant allele burden in buccal DNA was <25% of the value observed in granulocytes. In the great majority of somatic mutations (∼90%), no signal was detected in the germline control DNA.

Sanger Sequencing and AS-PCR

For a minority of amplicons, no sequencing coverage was obtained with the Ion Torrent PGM. For these regions, Sanger sequencing for mutation validation was performed according to standard protocols. Allele-specific PCR (AS-PCR) of CALR exon 9 was performed as previously reported.13

Analyses of patient cell colonies

The colony assays were performed using peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients as previously published.7 After 14 days, colonies were picked and analyzed individually for JAK2 V617F using AS-PCR and for the presence of somatic mutations by Sanger sequencing, respectively. On average, 88 colonies per patient were analyzed. To determine the temporal order of mutation acquisition, at least 2 informative colonies were required. In total, we analyzed 33 patients.

Statistical analysis

Mutational status of genes mutated in ≥5 patients in the cohort was correlated with blood counts at diagnosis (hematocrit, platelets, leukocytes, and neutrophils) in generalized linear models adjusting for patient gender, disease (PV vs ET vs PMF), and age. Survival and transformation curves were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier univariate method and compared by the Mantel-Cox log-rank test. Primary end points were overall survival, defined as time between diagnosis and death by any cause, and transformation to acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (version 20) and GraphPad Prism (version 6).

Results

We characterized a cohort of 200 MPN patients from whom paired granulocyte and nonhematopoietic DNA samples were available (Figure 1). Clinical characteristics of the patients at diagnosis of MPN are summarized in Table 1. Serial blood samples were available for 143 of 200 (72%) patients. To detect the maximal number of candidate mutations, granulocyte DNA from the most recent patient sample was used for initial sequencing. The workflow is summarized in Figure 1. We used the Agilent SureSelect method to capture exons and flanking regions of 104 selected genes with known or possible role in MPN (supplemental Figure 1A). To reduce PCR and sequencing artifacts, all DNA samples were processed and sequenced in duplicates and only sequence alterations that were present in both duplicate samples and displayed a mutant allele burden of >5% were further analyzed. The average exon coverage of Illumina sequencing per patient was 370-fold (supplemental Figure 2A), and only 3 patients had to be excluded due to insufficient coverage (Figure 1A). Resequencing of granulocyte DNA confirmed 437 of the 549 candidate mutations (80%) that were detected in the original screening (Figure 1B). Using DNA derived from buccal mucosa or hair follicles, we found that 334 of the 437 mutations were germline (76%) and 103 were somatic (24%) (Figure 1C). Furthermore, we screened our cohort also for mutation in the CALR gene using AS-PCR.13 Overall, 41 of 94 PV patients (44%), 20 of 69 ET patients (29%), and 12 of 34 PMF patients (35%) carried somatic mutations other than JAK2 V617F or CALR.

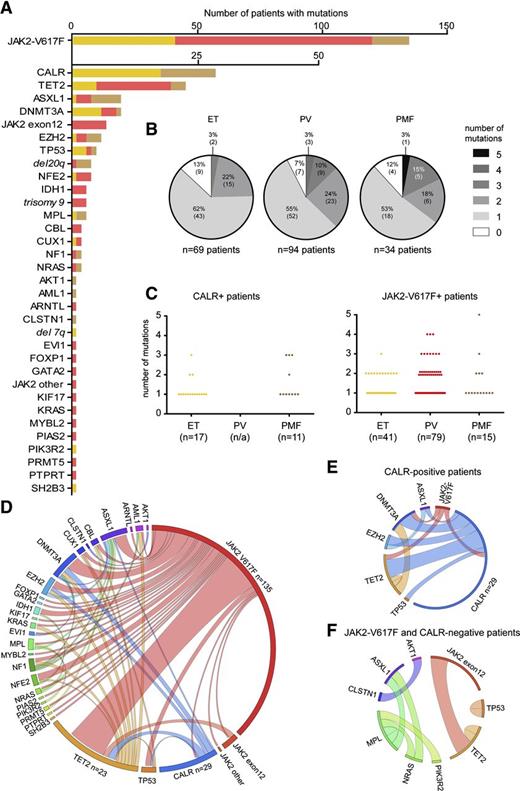

Frequency and distribution of mutations in patients with MPN

By NGS, we found that 28 of 104 (27%) of genes analyzed were mutated in at least 1 of the 197 MPN patients (supplemental Table 1). By AS-PCR, in addition, 17 of 69 (25%) ET patients and 11 of 34 (32%) PMF patients carried mutations in CALR. After JAK2 V617F and CALR, the most frequently observed mutations affected genes implicated in epigenetic regulation (TET2, ASXL1, DNMT3A, EZH2, and IDH1) (Figure 2A). We also identified 2 novel somatic mutations in the tumor suppressor NF1. Furthermore, we found mutations in NFE2, which had only been described in one recent report,22 and CUX1, uncovered previously in an MPN patient transforming to AML.23 Recurrent somatic mutations were also observed in the genes TP53, CBL, MPL, and NRAS. Nonrecurrent mutations were detected in 16 other genes (Figure 2A). By measuring the relative read abundance of targeted regions in patients and normal controls, the NGS approach also detected copy number alterations, for example, deletions on chromosome 20q (Figure 2A and supplemental Figure 3). The distribution of mutations per patient is summarized in Figure 2B and supplemental Figure 2G. Overall, 20 of 197 patients (10%) had no detectable somatic mutation in any of the genes analyzed (9 ET, 7 PV, and 4 PMF). Two or more somatic mutations were found in 65 of 197 (33%) patients. The frequencies of somatic mutations in patients positive for either CALR or JAK2 V617F are depicted in Figure 2C. Circos diagrams show the cooccurrence of all somatic mutations (Figure 2D) and the cooccurrence of events in CALR-positive patients (Figure 2E) and patients negative for mutation in both JAK2 V617F and CALR (Figure 2F). In contrast to the recently published studies that reported JAK2 and CALR mutations to be mutually exclusive,13,14 we observed coexistence of JAK2 V617F and CALR mutations in 1 ET patient (Figure 2E). This coexistence was confirmed in granulocytes from 3 independent time points 1.5 years apart.

Frequency and distribution of mutations in patients with MPN. (A) Number of patients with mutations in the genes is indicated. ET patients are depicted in yellow, PV patients in red, and PMF patients in light brown. Numeric chromosomal aberrations are marked in italic font. (B) Distribution of somatic mutations among the 197 MPN patients according to phenotype. The shades of gray indicate the number of somatic mutations per patient. (C) Average number of somatic mutations per patient in CALR-positive (left panel) and JAK2-V617F–positive individuals (left panel) observed in ET, PV, and PMF patients, respectively. (D) Circos plot illustrating cooccurrence of somatic mutations in the same individual. The length of the arc corresponds to the frequency of the mutation, whereas the width of the ribbon corresponds to the relative frequency of co-occurrence of 2 mutations in the same patient. (E) Circos plot showing cooccurrence of somatic mutations in CALR-positive patients. (F) Circos plot showing co-occurrence of somatic mutations in patients negative for JAK2 V617F and mutations in CALR.

Frequency and distribution of mutations in patients with MPN. (A) Number of patients with mutations in the genes is indicated. ET patients are depicted in yellow, PV patients in red, and PMF patients in light brown. Numeric chromosomal aberrations are marked in italic font. (B) Distribution of somatic mutations among the 197 MPN patients according to phenotype. The shades of gray indicate the number of somatic mutations per patient. (C) Average number of somatic mutations per patient in CALR-positive (left panel) and JAK2-V617F–positive individuals (left panel) observed in ET, PV, and PMF patients, respectively. (D) Circos plot illustrating cooccurrence of somatic mutations in the same individual. The length of the arc corresponds to the frequency of the mutation, whereas the width of the ribbon corresponds to the relative frequency of co-occurrence of 2 mutations in the same patient. (E) Circos plot showing cooccurrence of somatic mutations in CALR-positive patients. (F) Circos plot showing co-occurrence of somatic mutations in patients negative for JAK2 V617F and mutations in CALR.

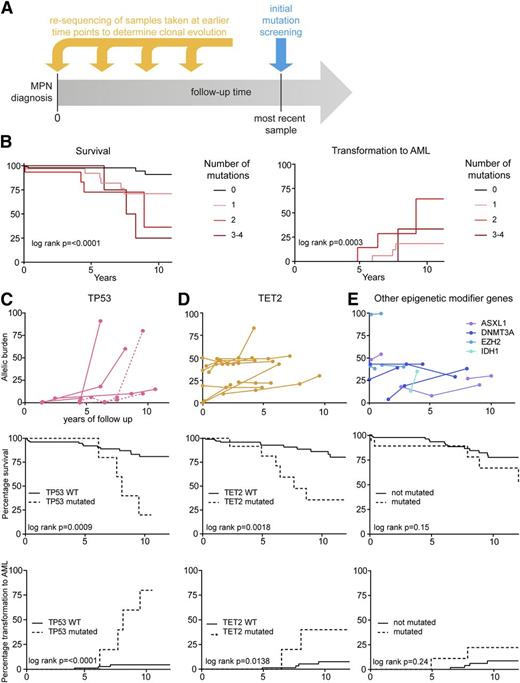

Serial samples were available from 28 of the 73 patients (38%) carrying somatic mutations other than JAK2 V617F or CALR. To estimate the mutation rate, we determined whether 38 somatic mutations found in the most recent sample were already present in the first patient sample that was available (Figure 3A and supplemental Figure 4). We found that the vast majority of mutations (36/38, 95%) were already detectable in the first sample and only 2 somatic mutations were acquired in a total of 133 patient years of follow-up (supplemental Figure 4). Thus, a patient would have to live ∼66 years to acquire 1 mutation in the targeted region.

Analysis of sequential samples: clinical correlations and risk stratification. (A) Scheme of resequencing of mutations in serial samples to determine the time of acquisition and clonal evolution. (B) Kaplan-Meier curves for the probabilities of survival (left panel) and transformation into AML (right panel). Numbers indicate the number of somatic mutations per patient omitting JAK2 V617F and CALR mutations. (C) Time course of the TP53 mutant allele burden in serial follow-up samples of 4 MPN patients with available follow-up samples (upper panel). One patient harbored 2 distinct TP53 mutations (dotted lines), only one of which displayed loss of heterozygosity. Survival (middle panel) and transformation to AML (lower panel) is shown below for 5 patients with mutations in TP53. (D) Time course of the TET2 mutant allele burden in serial follow-up samples of 12 MPN patients (upper panel). Survival (middle panel) and transformation to AML (lower panel) is shown below for 23 patients with mutations in TET2. (E) Time course of the mutant allele burden of epigenetic modifiers (ASXL1, DNMT3A, EZH2, and IDH1) in serial follow-up samples of 11 MPN patients (upper panel). Survival (middle panel) and transformation to AML (lower panel) is shown below for 29 patients with mutations in ASXL1, DNMT3A, EZH2, or IDH1.

Analysis of sequential samples: clinical correlations and risk stratification. (A) Scheme of resequencing of mutations in serial samples to determine the time of acquisition and clonal evolution. (B) Kaplan-Meier curves for the probabilities of survival (left panel) and transformation into AML (right panel). Numbers indicate the number of somatic mutations per patient omitting JAK2 V617F and CALR mutations. (C) Time course of the TP53 mutant allele burden in serial follow-up samples of 4 MPN patients with available follow-up samples (upper panel). One patient harbored 2 distinct TP53 mutations (dotted lines), only one of which displayed loss of heterozygosity. Survival (middle panel) and transformation to AML (lower panel) is shown below for 5 patients with mutations in TP53. (D) Time course of the TET2 mutant allele burden in serial follow-up samples of 12 MPN patients (upper panel). Survival (middle panel) and transformation to AML (lower panel) is shown below for 23 patients with mutations in TET2. (E) Time course of the mutant allele burden of epigenetic modifiers (ASXL1, DNMT3A, EZH2, and IDH1) in serial follow-up samples of 11 MPN patients (upper panel). Survival (middle panel) and transformation to AML (lower panel) is shown below for 29 patients with mutations in ASXL1, DNMT3A, EZH2, or IDH1.

Clinical correlations and risk stratification

We analyzed the impact of the number of mutations other than JAK2 V617F on survival and transformation into AML using the log-rank test for trend. We observed that increased number of somatic mutations lead to a significantly reduced overall survival and increased the risk of transformation into AML (Figure 3B). Patients with mutations in TP53, TET2, or other genes involved in epigenetic regulation (ASXL1, DNMT3A, EZH2, and IDH1) were analyzed separately (Figure 3C-E). We had serial samples from 4 out of 5 patients carrying TP53 mutations. In these 4 patients, the TP53 mutations were detected at a low allele burden in the first available sample and remained low for several years (Figure 3C). After loss of the WT allele through mitotic recombination or deletion, the hemi- or homozygous TP53 clone expanded rapidly in 3 out of 4 patients, and these 3 patients transformed to AML (Figure 3C), whereas 1 patient remained stable at a low allelic burden. The fifth patient with TP53 mutation (from whom serial samples were not available) also transformed to AML. Serial blood samples were also available in 12 out of 23 patients with mutations in TET2, and in 11 of these patients, the TET2 mutation was already present in the initial sample. Patients carrying TET2 mutations had significantly reduced overall survival and an increased risk of leukemic transformation (Figure 3D). The number of individual patients with mutations in DNMT3A, ASXL1, EZH2, or IDH1 was low, and when combined as a group, these patients showed no significant differences in the clinical course (Figure 3E). Thus, only 2 patients acquired a mutation during follow-up. One of these patients was treated with hydroxyurea (TP53 mutation), whereas the second patient was treated with aspirin only (TET2 mutation).

In addition, we observed correlations between mutation status and blood counts at diagnosis. Patients with an increased number of somatic mutations had a significantly higher leukocyte count (supplemental Figure 5A). Moreover, individuals with ASXL1 mutations had significantly lower hemoglobin levels than their WT counterparts (supplemental Figure 5B), whereas patients carrying EZH2 mutations had a significantly increased leukocyte count (supplemental Figure 5C).

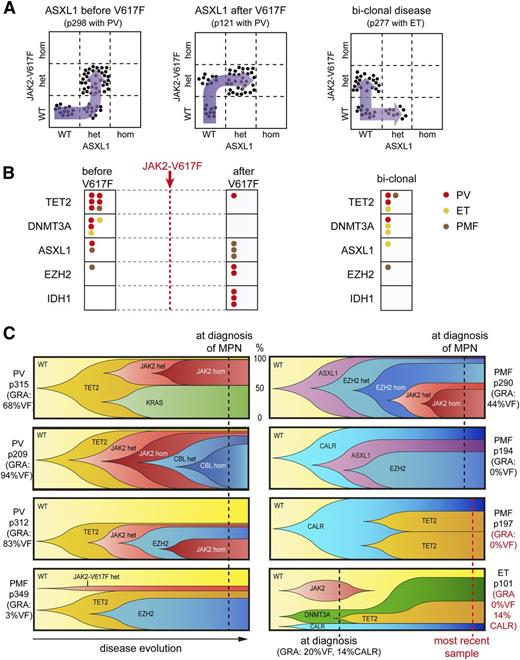

Clonal evolution

For clonal analyses, we focused on patients carrying mutations in epigenetic modifier genes. To address the temporal order of acquisition, we genotyped DNA from single colonies grown in methylcellulose and plotted the results for each of the colonies analyzed (Figure 4A). The mutations could be classified as occurring before, after, or in a clone separate from JAK2 V617F, and 1 example for each of these patterns is shown in Figure 4A. The results from all patients analyzed are summarized in Figure 4B. We found that mutations in TET2 and DNMT3A were predominantly acquired before JAK2 V617F or coexisted as separate clones (biclonal disease). Mutations in ASXL1 and EZH2 occurred before, after, or separate from JAK2 V617F, whereas in 3 patients, IDH1 mutation occurred exclusively after JAK2 V617F (Figure 4B).

Clonal evolution in MPN patients carrying somatic mutations in epigenetic modifier genes. Single erythroid or granulocytic colonies (BFU-Es and CFU-G) grown in methylcellulose were individually picked and analyzed for the presence or absence of JAK2 V617F and other somatic mutations. (A) Examples of 3 patients who acquired an ASXL1 mutation before JAK2 V617F (left panel), after JAK2 V617F (middle panel), or in a clone separate from JAK2 V617F (right panel) are shown. Each dot represents a single colony that was genotyped and placed into the corresponding quadrant. (B) Summary of the temporal order of acquisition of mutations in relation to JAK2 V617F. Each dot represents 1 patient analyzed as shown in panel A and placed into the corresponding quadrant. Events in ET patients are depicted in yellow, PV patients in red, and PMF patients in brown. (C) Patterns of clonal evolution in 8 MPN patients carrying multiple somatic mutations. Dotted lines denote the time of analysis and the y-axis indicates the percentage of the colonies with or without the corresponding somatic mutations. %VF, JAK2-V617F mutant allele burden in purified granulocytes from peripheral blood. Although the order of events depicted can be deduced from the single-clone analysis (dotted line), the exact timing of the acquisition of the individual mutations and the time needed for the clonal expansion remains unknown and is shown only schematically. GRA, granulocytes.

Clonal evolution in MPN patients carrying somatic mutations in epigenetic modifier genes. Single erythroid or granulocytic colonies (BFU-Es and CFU-G) grown in methylcellulose were individually picked and analyzed for the presence or absence of JAK2 V617F and other somatic mutations. (A) Examples of 3 patients who acquired an ASXL1 mutation before JAK2 V617F (left panel), after JAK2 V617F (middle panel), or in a clone separate from JAK2 V617F (right panel) are shown. Each dot represents a single colony that was genotyped and placed into the corresponding quadrant. (B) Summary of the temporal order of acquisition of mutations in relation to JAK2 V617F. Each dot represents 1 patient analyzed as shown in panel A and placed into the corresponding quadrant. Events in ET patients are depicted in yellow, PV patients in red, and PMF patients in brown. (C) Patterns of clonal evolution in 8 MPN patients carrying multiple somatic mutations. Dotted lines denote the time of analysis and the y-axis indicates the percentage of the colonies with or without the corresponding somatic mutations. %VF, JAK2-V617F mutant allele burden in purified granulocytes from peripheral blood. Although the order of events depicted can be deduced from the single-clone analysis (dotted line), the exact timing of the acquisition of the individual mutations and the time needed for the clonal expansion remains unknown and is shown only schematically. GRA, granulocytes.

For patients with 3 or more somatic mutations, the results from single-colony analyses are shown in Figure 4C. In patients carrying mutations in JAK2 V617F and epigenetic modifier genes or mutations in TET2 or DNMT3A were predominately acquired as the first event. In 2 patients, CALR mutations were acquired first and were present in all colonies examined (p194 and p197), whereas 1 patient (p101) displayed a complex pattern with 3 separate clones at diagnosis with disappearance of the JAK2 V617F clone during follow-up (Figure 4C). Interestingly, all 7 patients from whom a sample at diagnosis was available already showed a complex mutational pattern in the single-clone analysis (Figure 4C).

Discussion

We used targeted NGS and AS-PCR to assess mutation profiles of 105 genes in a cohort of 197 MPN patients. Our results provide unique insights into the genomic landscape of MPN, its clonal evolution, and correlation with clinical outcomes.

We found that 90% of all MPN patients carried at least 1 somatic mutation. JAK2 V617F was the most frequent recurrent somatic mutation (69%), followed by CALR (15%), TET2 (12%), ASXL1 (5%), and DNMT3A (5%). These frequencies are similar to those recently reported in an exome study of MPN patients.14 Mutations with a low allelic burden frequently affected genes considered late events in MPN pathogenesis, such as TP53, IDH1, and KRAS/NRAS.

Our study also examined the longitudinal evolution of mutations in serial samples from patients with MPN using a sensitive NGS approach. Based on the comparison of the sequences in the first-available and the most recent patient samples, we estimated the overall mutation rate in the 104 genes examined to be 1 somatic mutation per 66 patient years (supplemental Figure 4). We also did not observe any de novo JAK2 V617F mutations in patients that were JAK2 V617F negative at diagnosis during a follow-up of 116 patient years (supplemental Figure 4). The mutation rate on a cohort basis was then calculated by dividing the age of the patients in years (at the time when the most recent sample was taken) by the number of somatic mutations in the 105 genes found in this sample by NGS. This analysis yielded a mutation rate of 1 somatic mutation per 45 patient years, which is fairly close to the result obtained by the longitudinal analysis (1/66 patient years). These observations do not support the presence of a strong hypermutable state in MPN24,25 and also question the magnitude of the genomic instability caused by expressing JAK2 V617F.26-28 Consistent with the low mutation rate that we observed, a recent exome-based study detected ∼0.2 somatic mutations per Mb in 151 MPN patients, showing that MPN has a low frequency of somatic mutations compared with other malignancies (eg, 0.37 mutations per Mb for AML and ∼1 mutation per Mb for multiple myeloma).14,29

Our analyses illustrate that one of the strongest predictors of outcome is the number of somatic mutations that occur in addition to JAK2, CALR, or MPL (Figure 3B). Interestingly, in our cohort, the group of patients carrying either no detectable somatic mutation or a mutation in JAK2, CALR, or MPL only had a particularly favorable prognosis. None of these patients showed leukemic transformation, suggesting that most genes with prognostic relevance are part of the gene set that we analyzed. In a study with a similar design in MDS patients, an association of time to AML transformation and number of mutations was found.30 We observed that mutations in TP53 and TET2 were associated with particularly poor outcome (Figure 3C and 3D). TET2 mutations were recently reported as negative prognostic markers in patients with intermediate-risk AML,31 and although a previous study in MPN showed no correlation between TET2 mutational status and survival,32 other studies found an increased incidence of TET2 mutation in blasts from patients with leukemic transformation.16 For TP53, we observed that mutations were present in a heterozygous state for an extended period of time during the chronic MPN phase without clonal expansion. However, after loss of the WT allele by either chromosomal deletion or uniparental disomy, the hemi- or homozygous TP53 clone rapidly expanded, ultimately leading to leukemic transformation (Figure 3C). Thus, patients with TP53 mutations represent a high-risk group, and screening for TP53 mutations in MPN patients should be considered. Because in the chronic phase of MPN the allelic burden of TP53 mutation was <15%, sensitive methods such as NGS are needed for reliable detection. The prediction of disease progression by TP53 mutations corresponding to our observations was described previously for patients with low-risk MDS33 and chronic lymphocytic leukemia.34 One recent study reported TP53 mutations to be frequent in leukemic blasts of transformed MPN patients,17 whereas in chronic MPN from the same cohort, 2 out of 65 patients carried monoallelic TP53 mutations.

By dissecting the clonal architecture of patients carrying ≥3 distinct somatic mutations, we found diverse patterns, some compatible with a linear acquisition of mutations, but also several cases with an apparent biclonal structure (Figure 4). Overall, such a biclonal pattern was found in 7 of 33 patients (21%), which illustrates that in many patients, the clonal architecture cannot be imputed using allele burden of mutations alone. In general, mutations in TET2 and DNMT3A were early genetic events acquired before JAK2 V617F, whereas mutations in ASXL1, EZH2, or IDH1 were often acquired after JAK2 V617F. In contrast, mutations in CALR appeared to be an early event in the limited number of patients analyzed, consistent with previous reports.13,14 One patient (p101) showed a complex 3 clonal pattern, and the CALR clone was present only in a minority of the colonies (Figure 4C).

Based on our data and previous studies, a model is presented in Figure 5. With the current methodologies, 10% of MPN patients show no detectable somatic mutations in the 105 genes analyzed (top row). In an additional 54% of patients, JAK2 V617F or CALR were the only detected mutations. These 64% of MPN patients in our cohort displayed the most favorable prognosis and the lowest risk of disease progression. In the remaining 36% of MPN patients, we detected combinations of >1 somatic mutation, and in some patients, we can define the stage and order of acquisition. In the case of JAK2-V617F–positive MPN, often a somatic mutation occurred before the acquisition of JAK2 V617F, compatible with providing a “fertile ground” for MPN disease initiation.35 In contrast, CALR mutations appear to be the initiating event that could be followed by mutations in same set of genes as observed in JAK2-positive MPN. Patients with multiple mutations formed a high-risk category, with increased risk of transformation and reduced survival. Although based on a limited number of patients, the acquisition of TP53 appears to be a particularly unfavorable event, and loss of heterozygosity was invariably associated with progression to AML.

Model of MPN disease evolution and risk stratification in correlation to mutational events.

Model of MPN disease evolution and risk stratification in correlation to mutational events.

There is an Inside Blood commentary on this article in this issue.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ferdinand Martius and Sandrine Meyer for contributing patient samples and clinical data and Jürg Schwaller and Claudia Lengerke for helpful comments on the manuscript.

This work was supported by grants from the Gebert Rüf Foundation, the Swiss National Science Foundation (310000-120724/1 and 32003BB_135712/1), the Else Kröner-Fresenius Foundation, and the Swiss Cancer League (KLS-02398-02-2009) (R.C.S.), by a junior scientist scholarship from the University of Basel (A.K.), and by a grant from the Austrian Science Fund (FWF4702-B20) (R.K.).

Authorship

Contribution: P.L. designed and performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; A.K. and R.N. performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; R.L., H.H.S., I.N., and C.B. performed research; S.G., T.L., J.P., and M.S. provided clinical data and analyzed results; R.K. designed research and analyzed data; and R.C.S. designed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation for T.L. is Kantonsspital St. Gallen, St. Gallen, Switzerland.

Correspondence: Radek C. Skoda, Department of Biomedicine, Experimental Hematology, University Hospital Basel, Hebelstrasse 20, 4031 Basel, Switzerland; e-mail: radek.skoda@unibas.ch.

References

Author notes

P.L. and A.K. contributed equally to this study.