Key Points

CD25+ CML LICs have high LIC capacity and secrete cytokines that constitute the LIC niche.

Targeting the IL-2/CD25 axis effectively eliminates CML LICs and improves the survival of CML model mice.

Abstract

Just as normal stem cells require niche cells for survival, leukemia-initiating cells (LICs) may also require niche cells for their maintenance. Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) is caused by the activity of BCR-ABL, a constitutively active tyrosine kinase. CML therapy with tyrosine kinase inhibitors is highly effective; however, due to the persistence of residual LICs, it is not curative. Several factors are known to support CML LICs, but purification of LICs and a thorough understanding of their niche signals have not yet been achieved. Using a CML-like mouse model of myeloproliferative disease, we demonstrate that CML LICs can be divided into CD25+FcεRIα− Lineage marker (Lin)− Sca-1+c-Kit+ (F−LSK) cells and CD25−F−LSK cells. The CD25+F−LSK cells had multilineage differentiation capacity, with a preference toward cytokine-producing mast cell commitment. Although cells interconverted between CD25−F−LSK and CD25+F−LSK status, the CD25+F−LSK cells exhibited higher LIC capacity. Our findings suggest that interleukin-2 derived from the microenvironment and CD25 expressed on CML LICs constitute a novel signaling axis. The high levels of CD25 expression in the CD34+CD38− fraction of human CML cells indicate that CD25+ LICs constitute an “LIC-derived niche” that could be preferentially targeted in therapy for CML.

Introduction

Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) is a clonal hematopoietic stem cell disorder characterized by the t(9;22)(q34;q11) reciprocal translocation, called the Philadelphia chromosome.1 The Philadelphia chromosome produces a fusion protein, BCR-ABL, which functions as a constitutively active tyrosine kinase. CML is divided into 3 phases, based on its clinical characteristics. CML initially presents as the chronic phase (CP), characterized by the expansion of functionally normal myeloid lineage cells. Upon acquisition of secondary mutations, CP progresses to the accelerated phase (AP) and ultimately to the blast crisis (BC) phase of acute leukemia. CML therapy with tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) is highly effective, but not curative in a majority of patients, presumably due to the insensitivity of CML leukemia-initiating cells (LICs) to TKIs.2 Although CML CP is now controllable, the cessation of TKI treatment in patients with major molecular remission usually results in early relapse of CML,3 supporting the idea that CML LICs should be targeted separately from the TKI-sensitive differentiated CML fraction.4 The AP and early phase of BC remain intractable.

LICs are analogous to tissue stem cells; both cell types are characterized by slow cell cycling and niche dependency.5,6 Indeed, in a murine model7 and in human samples,8 the surface markers of CML LICs are almost identical to those of normal hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs); however, neither purification of LICs nor a thorough understanding of their niche cells has yet been achieved. In human CML, an increase in basophils is frequently observed; therefore, basophils are candidate niche cells for CML LICs. In this study, we focused our attention on CD25-positive cells, which are related to basophils and neoplastic mast cells.9,10

CD25, the α-chain of the interleukin-2 (IL-2) receptor, is encoded by the IL2RA gene; together with the β- and γ-chains, it constitutes the high-affinity IL-2 receptor.11 CD25 is expressed mainly on lymphocytes, including activated T cells and regulatory T cells; via Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription pathways, it transduces IL-2 signals that regulate cell survival and proliferation.12 Aberrant expression of CD25 in human acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is associated with poor prognosis,13,14 but its pathophysiological significance is unknown.

We found that LICs in a murine CML model, as well as those in human CML, consist of 2 distinct populations distinguished by CD25 expression. Our results show the CD25 ligand IL-2, derived from the microenvironment, is required to maintain distinct CML LICs in the niche. Thus, the IL-2/CD25 axis could represent a novel target for therapy aimed at the eradication of LICs.

Materials and methods

Mice

Eight- to 12-week-old C57BL/6J mice were used in each experiment, unless stated otherwise. C57BL/6-Ly5.1 congenic mice were used for coculture experiments and intracellular analysis of IL-2+ cells by flow cytometry. Il2ra−/− mice15 were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. All procedures were performed in accordance with the guidelines of Keio University School of Medicine.

Reagents

Human thrombopoietin (TPO) (PeproTech), mouse stem cell factor (SCF) (PeproTech), mouse IL-2 (PeproTech), mouse IL-3 (PeproTech), mouse transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1) (Cell Signaling Technology), and mouse TGF-β2 (R&D Systems) were used.

Generation of murine CML model

Normal immature Lin−Sca-1+c-Kit+ hematopoietic cells (LSK cells) from C57BL/6J mice were purified by flow cytometry and cultured in serum-free S-clone SF-O3 medium (Sanko Junyaku) supplemented with 100 ng/mL TPO and 100 ng/mL SCF. To generate CML-like myeloproliferative disease mouse models, normal LSK cells were transduced, using CombiMag (OZ Biosciences), with retrovirus carrying p210 BCR-ABL in a pMY–internal ribosome entry site (ires)–green fluorescent protein (GFP) vector.16-18 Transduced LSK cells (2 × 104 per mouse) were transplanted IV into lethally irradiated (9.5 Gy) C57BL/6J congenic mice along with 5 × 105 bone marrow mononuclear cells from C57BL/6J mice. For serial transplantations, GFP+CD127−LSK cells were collected from the spleens of primary transplanted mice, pooled, and subdivided into CD25+F+LSK, CD25+F−LSK, and CD25−F−LSK fractions. Isolated cells (7.5 × 103) from each fraction were transplanted into a second set of lethally irradiated (10.5 Gy) congenic recipients with 5 × 105 normal bone marrow mononuclear cells from C57BL/6J mice. For limiting-dilution transplants, lethally irradiated (9.5 Gy) mice received transplants of a various number of cells from the CD25+ LSK or CD25− LSK group along with 5 × 105 normal bone marrow mononuclear cells from C57BL/6J mice. For homing analysis, transduced CD25+LSK or CD25−LSK cells (2 × 104 per mouse) were transplanted IV into lethally irradiated (9.5 Gy) C57BL/6J congenic mice and analyzed 16 hours after bone marrow transplantation (BMT). For the IL-2 injection experiment, CML mice were injected intraperitoneally with 10 000 U of murine IL-2 or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) on days 1, 2, and 3 after BMT.

Treatment with mAbs

CML mice were injected intraperitoneally with 1 mg of anti-CD25 monoclonal antibody (mAb) (PC61; BioXCell) or anti–IL-2 antibody (JES6-1; BioXCell) dissolved in PBS. The same amounts of anti-isotype antibodies (HRPN or 2A3) were administered to the control groups. For TKI combination experiment, nilotinib (kind gift from Novartis) (1 mg per day) or vehicle were orally administrated to mice on days 6, 8, and 10 after BMT.

Flow cytometry

Analyses of various HSC fractions were performed essentially as previously described19 using a SORP FACSAria (BD Biosciences). Data were analyzed using FlowJo software (TreeStar). The following mAbs were used: rat mAbs against c-Kit (2B8), Sca-1 (E13-161.7), CD4 (L3T4), CD8a (53-6.72), B220 (RA3-6B2), TER-119, Gr-1 (RB6-8C5), CD34 (RAM34), Mac-1 (M1/70), CD3 (500A2), Flt-3 (A2F10.1), FcεRIα (MAR-1), CD25 (3C7), CD45.2 (104), CD45.1 (A20), CD16/32 (93), and CD127 (SB/199). All rat mAbs were purchased from BD Biosciences, eBioscience, or Biolegend. A mixture of mAbs against CD4, CD8, B220, TER-119, Mac-1, and Gr-1 served as a lineage marker (Lineage). For intracellular staining of IL-2, spleen cells from CML mice (donor: Ly5.2, recipient/competitor: Ly5.1) were stimulated with ConA (3 μg/mL) for 48 hours. Cells were washed and restimulated with Dynabeads Mouse T-Activator CD3/CD28 (Gibco), and secretion of IL-2 was blocked with Brefeldin A (eBioscience). Before being subjected to flow cytometry, restimulated cells were stained for surface markers, fixed, permeabilized, and stained with phycoerythrin–conjugated anti–IL-2 antibody or isotype control.

Surface marker screening

Bone marrow cells from CML model mice were subdivided into GFP+LSK, GFP+c-Kit+Lin−Sca-1− (LKS−), and GFP−LSK fractions. Staining patterns of candidate antigens in these 3 cell types were analyzed using a SORP FACSAria.

Gene expression analysis

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) was performed as described previously.20 The complementary DNA (cDNA) equivalent of 1000 cells was used as the template for each reaction. PCR primers for each gene were purchased from TaKaRa Bio. For microarray analysis, total RNA was extracted from CD25+LSK, CD25−LSK, LKS−, and Gra-1+Mac-1+ cells obtained from GFP+ splenic cells of CML model mice. Total RNA was purified using an RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN). Microarray (3D-Gene Mouse Oligo chip 24k) processing was performed by Toray Industries, Inc.

In vitro culture

For colony-forming assays, CD25+F+LSK, CD25+F−LSK, and CD25−F−LSK cells were plated (500 cells per 35-mm dish) in a semisolid methylcellulose medium-containing cytokines (MethoCult GF M3434; Stem Cell Technologies). Colony numbers were assessed at day 7. For liquid culture, cells were cultured in serum-free S-clone SF-O3 medium, unless stated otherwise. All cell cultures were incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere.

Immunohistochemistry of bone marrow

Frozen bone marrow sections were fixed using dry ice/ethanol. Fixed sections were washed and stained using primary antibodies against IL-2, lineage markers, GFP, and CD25, followed by staining with secondary antibodies. Immunofluorescence data were obtained and analyzed using a confocal laser-scanning microscope (FV1000; Olympus). UPlanApo 20×/0.70 objective lens (Olympus) and FV10-ASW2.0 viewer (Olympus).

Human CML samples

Bone marrow cells were collected from untreated CML CP patients and lymphoma patients without bone marrow involvement, and the surface markers of these cells were analyzed on a FACSAria II cell sorter (Becton Dickinson). Fluorophore-conjugated mAbs against human CD34 (QBEnd10; Beckman Coulter), human CD38 (HB7; BD Biosciences), and human CD25 (M-A251; BD Biosciences) were used to label surface markers. The protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the University of Tokyo Hospital. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. For colony-forming assays performed on human CML samples, frozen bone marrow cells derived from untreated CML patients were thawed, 5 × 104 live cells were plated in semisolid methylcellulose medium-containing cytokines (MethoCult GF H4434; STEMCELL Technologies) and cultured for 1 week; then, the colonies on each dish were counted.

Microarray analysis of human CML samples

Gene expression profiles of CML patient samples, described previously,21 were obtained from a public repository (Gene Expression Omnibus, accession: GSE4170). Normalized expression levels of IL2RA were obtained (ID_REF 10012686352, from GSE4170_seriese_matrix.txt). Samples were classified into 3 groups, CP (n = 57), AP (n = 9), and BC (n = 33), as described in the original data set, and then sorted by IL2RA expression level. Gene expression profiles of B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL) patient samples, described previously,22 were obtained from a public repository (Gene Expression Omnibus, Accession: GSE34861), and gene set enrichment analysis was performed as described next.

Gene set enrichment analysis

Normalized expression data were assessed using Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) v2.0.13 software (Broad Institute). Gene sets used are listed in supplemental Table 2 (available on the Blood Web site), which were obtained from the Molecular Signatures Database v4.0 distributed at the GSEA Web site (http://www.broadinstitute.org/gsea/msigdb/index.jsp). The number of permutations was set as 1000. For gene expression data from CML patients (accession: GSE4170), patients with CP (n = 57) and BC (n = 33) were compared. For gene expression data from B-ALL patients (accession: GSE34861), patients with >50% CD25-positive cells (n = 43) were compared with patients with <50% CD25+ cells (n = 151). Gene sets with nominal P value < .05 and the false discovery rate q-value < 0.25 was considered to be statistically significant.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as means ± SD unless stated otherwise. Statistical significance was determined by the Tukey multiple comparison test. For comparisons between the 2 groups, the 2-tailed Student t test was used. The log-rank test was used for survival data.

Results

CD25 expression marks distinct subsets of cells in the CML LIC population

To purify CML LICs, we searched for surface markers that were differentially expressed in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) in the CML mouse model. In these mice, CD25 was expressed specifically on BCR-ABL+LSK cells (Figure 1A-B; supplemental Table 1). We also confirmed that CD25 was highly expressed in the BCR-ABL+CD34−Flt3−LSK fraction, in which long-term HSCs have been reported to exist (supplemental Figure 1A-C). CD25 was expressed in normal bone marrow CD4+ lymphocytes (which include CD25+ regulatory T cells) but not in LSK cells or granulocyte-macrophage progenitors (GMPs) (Figure 1C).

CD25 expression marks distinct subsets of cells in the CML LIC population. (A) Screening strategy for antigens differentially expressed on CML LSK cells. LSK cells were transduced with BCR-ABL retroviral vector and transplanted into recipient mice. Bone marrow cells were collected 10 to 12 days after transplantation, and staining patterns of candidate antigens in 3 types of cells (BCR-ABL+LSK, LKS−, and BCR-ABL−LSK) were analyzed by flow cytometry. (B) CD25+ cells in the 3 cell types in panel A (%) (means ± standard deviation [SD], n = 3). (C) Flow cytometric analysis of CD25 expression in normal bone marrow fractions, including LSK, GMP (Lin−c-Kit+Sca-1−CD34+FcγRII/III+), and CD4+ cells (orange histograms). Gray histograms indicate isotype control staining. Numbers indicate the CD25-positive fraction (means ± SD, n = 3). (D) Flow cytometric analysis of BCR-ABL+LSK cells from CML model mice costained with CD25 and FcεRIα. Giemsa-stained cytospin specimens of the 3 fractions (CD25+F+LSK, CD25+F−LSK, and CD25−F−LSK cells) are shown. Images were obtained and analyzed using a microscope (IX70; Olympus). UPlanApo 40×/0.85 objective lens (Olympus) and DP Controller (Olympus). (E) qPCR analysis of mast cell–related genes in the indicated fractions from CML model mice (means ± SD, n = 4). *P < .05; **P < .01.

CD25 expression marks distinct subsets of cells in the CML LIC population. (A) Screening strategy for antigens differentially expressed on CML LSK cells. LSK cells were transduced with BCR-ABL retroviral vector and transplanted into recipient mice. Bone marrow cells were collected 10 to 12 days after transplantation, and staining patterns of candidate antigens in 3 types of cells (BCR-ABL+LSK, LKS−, and BCR-ABL−LSK) were analyzed by flow cytometry. (B) CD25+ cells in the 3 cell types in panel A (%) (means ± standard deviation [SD], n = 3). (C) Flow cytometric analysis of CD25 expression in normal bone marrow fractions, including LSK, GMP (Lin−c-Kit+Sca-1−CD34+FcγRII/III+), and CD4+ cells (orange histograms). Gray histograms indicate isotype control staining. Numbers indicate the CD25-positive fraction (means ± SD, n = 3). (D) Flow cytometric analysis of BCR-ABL+LSK cells from CML model mice costained with CD25 and FcεRIα. Giemsa-stained cytospin specimens of the 3 fractions (CD25+F+LSK, CD25+F−LSK, and CD25−F−LSK cells) are shown. Images were obtained and analyzed using a microscope (IX70; Olympus). UPlanApo 40×/0.85 objective lens (Olympus) and DP Controller (Olympus). (E) qPCR analysis of mast cell–related genes in the indicated fractions from CML model mice (means ± SD, n = 4). *P < .05; **P < .01.

To characterize CML CD25+LSK and CD25−LSK cells, we performed microarray analysis, which revealed that CML CD25+LSK cells expressed high levels of mast cell–related genes (supplemental Figure 2). Mast cells are FcεRIα+ granulated hematopoietic cells, derived from HSPCs, that produce a wide repertoire of cytokines.23 In parallel with the mast cell gene signature, CML CD25+LSK cells could be classified into FcεRIα+ and FcεRIα− subpopulations. CML CD25−LSK cells were FcεRIα− (Figure 1D); we confirmed the mast cell signature in the CD25+LSK fractions by quantitative PCR (qPCR) analysis (Figure 1E). We then evaluated the morphology of cells from each of these fractions (Figure 1D). Based on the morphological assessment, CD25+FcεRIα+LSK (F+LSK) cells were mast cells, CD25−F−LSK cells were immature stem cells, and the CD25+F−LSK fraction contained a mixture of both. Because Sca-1 expression has not been previously reported in mast cells, we compared the staining of 2 anti–Sca-1 mAb clones (E13-161.7 and D7). Using both clones, we observed equivalent frequencies of LSK, CD25−F−LSK, CD25+F−LSK, and CD25+F+LSK cells (supplemental Figure 3). Isolated CD25+F−LSK and CD25−F−LSK cells generated a comparable number of multilineage colonies in semisolid culture medium containing a cytokine cocktail (supplemental Figure 4A). CD25+F+LSK cells did not generate any colonies, indicating overall that CD25+F−LSK and CD25−F−LSK cells, but not CD25+F+LSK cells, have progenitor capacity. In addition, single CD25+F−LSK cells generated mast cell-containing colonies (supplemental Figure 4B), whereas CD25−F−LSK cells did not. This analysis suggests that CD25+F−LSK cells possess multilineage differentiation capacity, with a preference for differentiation into mast cells.

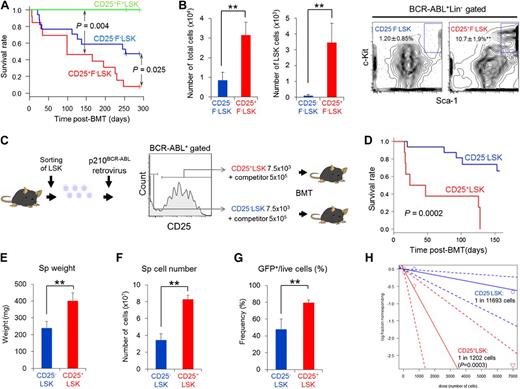

The CD25+ fraction has a higher LIC capacity and maintains CD25− LICs

Next, we performed an in vivo serial BMT assay to assess the LIC capacities of the CD25+F−LSK, CD25−F−LSK, and CD25+F+LSK fractions. Following secondary transplantation into recipient mice, both CD25+F−LSK and CD25−F−LSK cells promoted CML development, although CD25+F−LSK cells exhibited poorer survival (Figure 2A). In support of this observation, cultured CD25+F−LSK cells had a higher proliferative capacity than CD25−F−LSK cells (Figure 2B). Because CD25 expression is induced rapidly in cultured LSK cells within 2 days of BCR-ABL transduction in the absence of FcεRIα expression (Figure 2C; data not shown), we tested the LIC capacity of newly transduced BCR-ABL+CD25+ or CD25−LSK cells. Notably, BCR-ABL+CD25+LSK cells exhibited accelerated CML development (Figure 2D), and the CD25+LSK transplant group exhibited more aggressive CML phenotypes (Figure 2E-G). This observation was confirmed by limiting-dilution transplants, using 3 dose concentrations of newly transduced BCR-ABL+CD25+ or CD25−LSK cells (Figure 2H). These data prompted us to evaluate the possibility of a hierarchy of CD25+F−LSK and CD25−F−LSK cells with regard to differentiation. When we examined CD25 and FcεRIα expression in the cultured LSK fraction, we found that CD25+F−LSK and CD25−F−LSK cells interconverted ex vivo (Figure 3A-C). Furthermore, following transplantation of newly transduced BCR-ABL+CD25+ or CD25−LSK cells (Figure 2D), these cell types also interconverted in vivo (Figure 3D-E), indicating that CD25 expression can be switched on and off through an unknown mechanism, and arguing against a hierarchical order in differentiation. Notably, newly transduced BCR-ABL+CD25+LSK cells produced larger LSK subpopulations ex vivo and in vivo (Figure 3C,E).

CD25+F−LSK cells retain higher LIC capacity than CD25−F−LSK cells. (A) Survival curves of secondary recipients injected with BCR-ABL+CD25+F+LSK (n = 4), CD25+F−LSK (n = 13), and CD25−F−LSK cells (n = 17). (B) Expansion capacity of CD25+F−LSK or CD25−F−LSK cells ex vivo. Left, Cell numbers of indicated fractions; right, representative profiles (means ± SD, n = 4). (C) Experimental design. BCR-ABL+CD25+LSK or BCR-ABL+CD25−LSK cells were transplanted into lethally irradiated recipient mice. (D) Survival curves of the CD25+LSK (n = 8) and CD25−LSK (n = 16) groups after transplantation. (E-G) Spleen weight (E), spleen cell number (F), and percentage of BCR-ABL+ cells in spleens (G) of the CD25+LSK (n = 4) and CD25−LSK groups (n = 11) created in panel C were examined 11 days after transplantation (means ± SD). (H) Limiting-dilution analysis of the leukemia-initiating ability of the CML LIC population. Seven mice in each group (CD25+LSK or CD25−LSK) received transplants with each dosage of cells (70, 700, or 7000). **P < .01.

CD25+F−LSK cells retain higher LIC capacity than CD25−F−LSK cells. (A) Survival curves of secondary recipients injected with BCR-ABL+CD25+F+LSK (n = 4), CD25+F−LSK (n = 13), and CD25−F−LSK cells (n = 17). (B) Expansion capacity of CD25+F−LSK or CD25−F−LSK cells ex vivo. Left, Cell numbers of indicated fractions; right, representative profiles (means ± SD, n = 4). (C) Experimental design. BCR-ABL+CD25+LSK or BCR-ABL+CD25−LSK cells were transplanted into lethally irradiated recipient mice. (D) Survival curves of the CD25+LSK (n = 8) and CD25−LSK (n = 16) groups after transplantation. (E-G) Spleen weight (E), spleen cell number (F), and percentage of BCR-ABL+ cells in spleens (G) of the CD25+LSK (n = 4) and CD25−LSK groups (n = 11) created in panel C were examined 11 days after transplantation (means ± SD). (H) Limiting-dilution analysis of the leukemia-initiating ability of the CML LIC population. Seven mice in each group (CD25+LSK or CD25−LSK) received transplants with each dosage of cells (70, 700, or 7000). **P < .01.

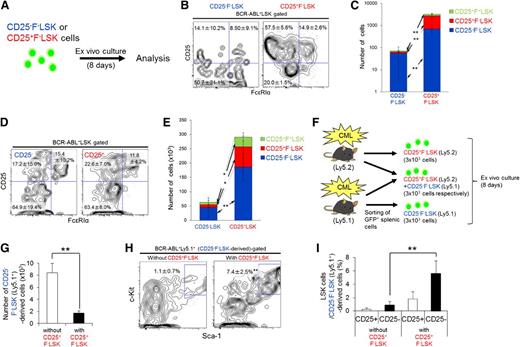

CD25+ LICs and CD25− LICs interconvert, and CD25+ LICs maintain CD25− LICs. (A) CD25+F−LSK or CD25−F−LSK cells from CML model mice (3 × 103 cells per sample) were cultured for 8 days. (B-C) Representative profiles (B) and calculated cell number (C; mean ± SD) are shown (n = 4). (D-E) BCR-ABL–transduced CD25+LSK or CD25−LSK cells (7.5 × 103 per sample) were transplanted into recipient mice, and splenic cells were analyzed 11 days later. Representative profiles of the LSK fraction (D) and cell numbers (E) are shown as mean frequencies and cell numbers ± SD (CD25+LSK, n = 4; CD25−LSK, n = 11). (F) Design of coculture study. Ly5.2+CD25+F−LSK cells alone, a mixture of Ly5.2+CD25+F−LSK cells and Ly5.1+CD25−F−LSK cells, and Ly5.1+CD25−F−LSK cells alone (3 × 103 of each cell type) were cultured for 8 days. (G) Cell number in CD25−F−LSK-derived fractions without or with CD25+F−LSK cells in panel F (means ± SD, n = 4). (H-I) LSK cells in GFP+Ly5.1+ cells were analyzed (means ± SD, n = 4); representative profiles (H), and the frequency of CD25− or CD25+ LSK cells (I) are shown. *P < .05; **P < .01.

CD25+ LICs and CD25− LICs interconvert, and CD25+ LICs maintain CD25− LICs. (A) CD25+F−LSK or CD25−F−LSK cells from CML model mice (3 × 103 cells per sample) were cultured for 8 days. (B-C) Representative profiles (B) and calculated cell number (C; mean ± SD) are shown (n = 4). (D-E) BCR-ABL–transduced CD25+LSK or CD25−LSK cells (7.5 × 103 per sample) were transplanted into recipient mice, and splenic cells were analyzed 11 days later. Representative profiles of the LSK fraction (D) and cell numbers (E) are shown as mean frequencies and cell numbers ± SD (CD25+LSK, n = 4; CD25−LSK, n = 11). (F) Design of coculture study. Ly5.2+CD25+F−LSK cells alone, a mixture of Ly5.2+CD25+F−LSK cells and Ly5.1+CD25−F−LSK cells, and Ly5.1+CD25−F−LSK cells alone (3 × 103 of each cell type) were cultured for 8 days. (G) Cell number in CD25−F−LSK-derived fractions without or with CD25+F−LSK cells in panel F (means ± SD, n = 4). (H-I) LSK cells in GFP+Ly5.1+ cells were analyzed (means ± SD, n = 4); representative profiles (H), and the frequency of CD25− or CD25+ LSK cells (I) are shown. *P < .05; **P < .01.

We then sought to determine the biological differences that explain the higher LIC capacity of the BCR-ABL+CD25+F−LSK fraction. Initially, we analyzed the apoptosis and homing capacities of LSK subpopulations, but no significant difference was observed (supplemental Figure 5A-C). Next, we analyzed the cell-cycle status of normal LSK, BCR-ABL+CD25−F−LSK, CD25+F−LSK, and CD25+F+LSK cells. The population of G0 cells was significantly lower in CD25+F−LSK cells, suggesting that these cells proliferate more actively than CD25−F−LSK cells (supplemental Figure 5D).

To investigate the possibility of reciprocal regulation by CD25+F−LSK and CD25−F−LSK cells, we performed coculture analysis (Figure 3F). When cultured with CD25+F−LSK cells, the total number of CD25−F−LSK–derived cells decreased. At the same time, however, the LSK fraction in CD25−F−LSK–derived cells increased in number and frequency (Figure 3G-I). These data indicate that the presence of CD25+F−LSK cells promotes a more primitive phenotype in CD25−F−LSK cells. To investigate the molecular basis for these changes, we performed qPCR analysis on CML LSK cells; the results revealed high expression of TGF-β2 and its receptor TGF-βR1 (supplemental Figure 6A), components of a signaling pathway that plays an important role in CML LIC maintenance.16 Upon TGF-β treatment, the CD25+F−LSK and CD25−F−LSK fractions both increased in frequency and number (supplemental Figure 6B), phenocopying the effect of CD25+F−LSK cells on CD25−F−LSK cells (Figure 3H-I). Thus, because CD25+F−LSK cells secrete higher levels of TGF-β, these cells may support the primitive phenotypes exhibited by CD25+F−LSK and CD25−F−LSK cells more effectively than CD25−F−LSK cells do.

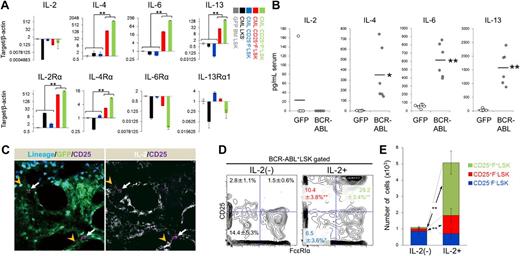

IL-2 from the microenvironment maintains Th2 cytokine–producing CD25+ CML LICs

We also assessed expression of cytokines and their receptors in CML LSK cells and found that Th2 cytokines (IL-4, -6, -13) were highly expressed in CD25+LSK fractions (Figure 4A). The trophic effects of IL-4 and IL-6 on CML LICs have been described previously.7,8 Based on the observation that serum Th2 cytokine levels were elevated in CML model mice (Figure 4B), it is possible that these cytokines modulate disease progression. On the other hand, serum IL-2 level was not elevated in these mice, suggesting that IL-2 instead exerts a local effect on the CD25+LSK cell microenvironment. CML CD25+LSK fractions, but not normal HSPCs, also expressed other IL-2 receptor components, for example, CD122/IL-2R β-chain and CD132/common γ-chain (Figure 4A; supplemental Figure 7), suggesting a direct effect of IL-2 on CD25+F−LSK cells. In support of this, CML CD25+F−Lin− cells colocalized closely with IL-2+Lin+ cells in bone marrow (Figure 4C). Intracellular flow cytometric analysis revealed that IL-2+ cells were positive for multiple hematopoietic differentiation markers, including CD8a, B220, and Gr-1 (supplemental Figure 8). Injection of IL-2 into CML mice accelerated their deaths (supplemental Figure 9A). In addition, supplementation of BCR-ABL–transduced LSK cells with IL-2 maintained the size (ie, frequency and cell number) of the BCR-ABL+LSK fraction relative to controls, and increased the sizes of the CD25+ fractions (Figure 4D-E). Also, supplementation of BCR-ABL–transduced CD25+F−LSK cells with IL-2 maintained the size of the BCR-ABL+LSK fraction (supplemental Figure 9B). Finally, addition of human IL-2 increased the colony formation capacity of human CML samples (supplemental Figure 9C). These findings suggest that microenvironment-derived IL-2 functions as a niche signal to generate more aggressive LICs in CML.

IL-2 from the microenvironment maintains Th2 cytokine-producing CD25+ CML LICs. (A) qPCR analysis of Th2 cytokine ligands and receptors in the indicated fractions from CML model mice (means ± SD, n = 4). (B) Serum cytokine levels in CML model mice and the control group were examined 11 days after transplantation (mean ± SD; CML, n = 6; GFP, n = 7). (C) Immunohistochemistry of bone marrow from CML model mice (white arrow: CD25+Lin− LIC, orange arrowhead: Lin+IL-2+ cell). Blue: Lineage marker; green, GFP (ie, BCR-ABL+); magenta, CD25; white, IL-2. (D-E) BCR-ABL–transduced LSK cells were cultured in SF-O3 medium supplemented with 100 ng/mL TPO plus 100 ng/mL SCF; 100 ng/mL IL-2 or vehicle was added 4 days later. Cells were analyzed 16 days later. Representative profiles of the LSK fraction (D) and cell number (E) are shown as mean frequencies and cell numbers ± SD (n = 5). *P < .05; **P < .01.

IL-2 from the microenvironment maintains Th2 cytokine-producing CD25+ CML LICs. (A) qPCR analysis of Th2 cytokine ligands and receptors in the indicated fractions from CML model mice (means ± SD, n = 4). (B) Serum cytokine levels in CML model mice and the control group were examined 11 days after transplantation (mean ± SD; CML, n = 6; GFP, n = 7). (C) Immunohistochemistry of bone marrow from CML model mice (white arrow: CD25+Lin− LIC, orange arrowhead: Lin+IL-2+ cell). Blue: Lineage marker; green, GFP (ie, BCR-ABL+); magenta, CD25; white, IL-2. (D-E) BCR-ABL–transduced LSK cells were cultured in SF-O3 medium supplemented with 100 ng/mL TPO plus 100 ng/mL SCF; 100 ng/mL IL-2 or vehicle was added 4 days later. Cells were analyzed 16 days later. Representative profiles of the LSK fraction (D) and cell number (E) are shown as mean frequencies and cell numbers ± SD (n = 5). *P < .05; **P < .01.

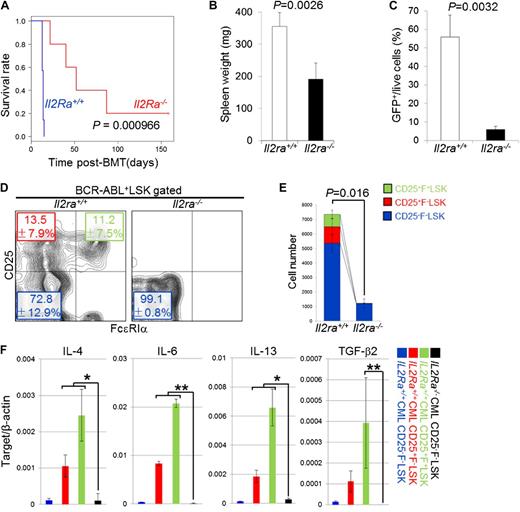

Targeting the IL-2/CD25 axis in CML LICs

As shown in Figure 2, the CD25+LSK fraction possesses the ability to propagate CML. This finding motivated us to assess the importance of the IL-2/CD25 axis in the pathogenesis of CML. To do so, we generated Il2ra+/+ or Il2ra−/− LSK-derived CML mice. The survival curves of these animals differed significantly as a function of Il2ra genotype (Figure 5A). Spleen weight, BCR-ABL+ splenic cell frequency, and peripheral blood abnormality were all lower in Il2ra−/− LSK–derived CML mice, relative to mice with CML harboring wild-type Il2ra (Figure 5B-C; supplemental Figures 10 and 11). The frequency and number of bone marrow and spleen BCR-ABL+ myeloid and LSK cells were also lower in Il2ra−/− LSK–derived CML mice (Figure 5D-E; supplemental Figure 11A-C). In addition to losing CD25 expression, the FcεRIα+ mast cell–like fraction of CML LSK cells disappeared in the absence of Il2ra, suggesting that CD25 is required for the generation or maintenance of this fraction (Figure 5D-E). The frequencies of LSK cells and LT-HSCs were not significantly different between Il2ra+/+ or Il2ra−/− mice (supplemental Figure 11D; data not shown); therefore, generation/maintenance of CML LSK cells, but not that of normal LSK cells, is dependent on CD25 expression. Furthermore, expression of Th2 cytokines and TGF-β2 in Il2ra−/− CML CD25−F−LSK cells was lower than that in CD25+F−LSK or CD25+F+LSK cells from Il2ra+/+ CML mice (Figure 5F). Thus, loss of CD25 ameliorates abnormal cytokine expression in the CML niche.

Genetic ablation of CD25 prevents pathogenesis of CML. (A) Survival of Il2ra+/+ (n = 11) or Il2ra−/− (n = 10) LSK-derived CML mice. (B-C) Spleen weight (B) and percentage of BCR-ABL+ cells in the spleen (C) of Il2ra+/+ or Il2ra−/− LSK–derived CML mice were examined 11 days after transplantation (n = 4; means ± SD). (D-E) Flow cytometric analysis of the frequency (D; means ± SD) and number (E; means ± standard error of the mean) of bone marrow LSK cells in Il2ra+/+ or Il2ra−/−LSK–derived CML mice (n = 4). (F) qPCR analysis of IL-4, IL-6, IL-13, and TGF-β2 mRNA in the indicated fractions from Il2ra+/+ or Il2ra−/− LSK–derived CML mice (means ± SD, n = 4). *P < .05; **P < .01. mRNA, messenger RNA.

Genetic ablation of CD25 prevents pathogenesis of CML. (A) Survival of Il2ra+/+ (n = 11) or Il2ra−/− (n = 10) LSK-derived CML mice. (B-C) Spleen weight (B) and percentage of BCR-ABL+ cells in the spleen (C) of Il2ra+/+ or Il2ra−/− LSK–derived CML mice were examined 11 days after transplantation (n = 4; means ± SD). (D-E) Flow cytometric analysis of the frequency (D; means ± SD) and number (E; means ± standard error of the mean) of bone marrow LSK cells in Il2ra+/+ or Il2ra−/−LSK–derived CML mice (n = 4). (F) qPCR analysis of IL-4, IL-6, IL-13, and TGF-β2 mRNA in the indicated fractions from Il2ra+/+ or Il2ra−/− LSK–derived CML mice (means ± SD, n = 4). *P < .05; **P < .01. mRNA, messenger RNA.

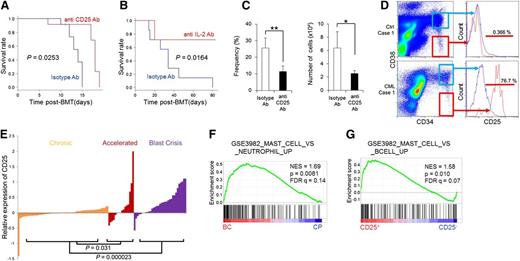

Next, we tested the potential effectiveness of targeting the IL-2/CD25 axis in CML. Administration of anti-CD25 mAb to CML model mice improved their survival and reduced the number and frequency of CD25+F−LSK cells (Figure 6A,C). Anti–IL-2 mAb administration also improved the survival of CML model mice and reduced the number and frequency of differentiated and LSK cells (Figure 6B; supplemental Figure 12), suggesting that activation of the IL-2/CD25 axis promotes CML. Furthermore, we investigated the potential effect of combined therapy, using anti-CD25 antibody and a conventional TKI, in CML mice. In these trials, CML model mice were treated with a TKI (nilotinib), with or without anti-CD25 mAb, and analyzed 11 days after transplantation. Nilotinib treatment alone effectively reduced the spleen size (supplemental Figure 13A), but the combination of nilotinib and anti-CD25 mAb reduced the numbers of leukemic and LSK cells in bone marrow and spleen (supplemental Figure 13B-E), suggesting a beneficial effect of combining TKI plus CD25 targeting in CML mice.

The IL-2/CD25 axis is a potential target for therapy directed against CML LICs. (A) Survival of CML model mice injected intraperitoneally with an anti-CD25 mAb (n = 12) or isotype IgG (n = 12) every other day from day 1 to day 15 after transplantation. (B) Survival of CML model mice treated with anti–IL-2 mAb (n = 7) or isotype IgG (n = 7) every other day from day 1 to day 15 after transplantation. (C) Frequency and number of CD25+F−LSK cells in panel A (11 days after transplantation) (means ± SD, n = 7). (D) Representative profiles for CD25 expression in the CD34+CD38− (red histogram) and CD34+CD38+ (blue histogram) fractions of freshly isolated bone marrow from untreated CML CP patients (n = 2) or lymphoma patients without bone marrow involvement (n = 3). (E) CD25 expression in bone marrow or peripheral blood of patients at various stages of CML, based on microarray data derived from the public database. (F-G) GSEA was applied to human leukemia samples. Genes upregulated in mast cells compared with neutrophils were significantly enriched in CML BC (n = 33) relative to CML CP (n = 57) (F), and genes upregulated in mast cells compared with B cells were significantly enriched in CD25+ B-ALL (n = 43) relative to CD25-low or -negative B-ALL (n = 151) (G) *P < .05; **P < .01. IgG, immunoglobulin G.

The IL-2/CD25 axis is a potential target for therapy directed against CML LICs. (A) Survival of CML model mice injected intraperitoneally with an anti-CD25 mAb (n = 12) or isotype IgG (n = 12) every other day from day 1 to day 15 after transplantation. (B) Survival of CML model mice treated with anti–IL-2 mAb (n = 7) or isotype IgG (n = 7) every other day from day 1 to day 15 after transplantation. (C) Frequency and number of CD25+F−LSK cells in panel A (11 days after transplantation) (means ± SD, n = 7). (D) Representative profiles for CD25 expression in the CD34+CD38− (red histogram) and CD34+CD38+ (blue histogram) fractions of freshly isolated bone marrow from untreated CML CP patients (n = 2) or lymphoma patients without bone marrow involvement (n = 3). (E) CD25 expression in bone marrow or peripheral blood of patients at various stages of CML, based on microarray data derived from the public database. (F-G) GSEA was applied to human leukemia samples. Genes upregulated in mast cells compared with neutrophils were significantly enriched in CML BC (n = 33) relative to CML CP (n = 57) (F), and genes upregulated in mast cells compared with B cells were significantly enriched in CD25+ B-ALL (n = 43) relative to CD25-low or -negative B-ALL (n = 151) (G) *P < .05; **P < .01. IgG, immunoglobulin G.

CD25 expression in human leukemias

We next asked whether CD25 is upregulated in human CML. CD25 was predominantly expressed in the CD34+CD38− hematopoietic stem cell fraction, but not in the CD34+CD38+ progenitor fraction of freshly isolated bone marrow from untreated CML patients or in the undiseased CD34+CD38− fraction of bone marrow (Figure 6D; supplemental Figure 14A). Flow cytometric profiles of CD25 expression in the CD34+CD38− and CD34+CD38+ fractions varied among samples (supplemental Figure 14B); this could potentially be attributed to the limited numbers of samples, or to the negative effects of freezing procedures on CD25 expression. We also tested whether CD25 expression is correlated with disease progression status, using gene expression data of CML patients available on the public repository. Notably, a comparison of CD25 expression in CML CP and BC patients indicated that CD25 expression rose during progression from CP to BC, suggesting involvement of CD25+ CML cells in CML pathology (Figure 6E).

We finally examined whether human CML or CD25-expressing leukemia is associated with a mast cell signature, as we demonstrated above in the murine model. Indeed, leukemic cells from CML BC patients, which are believed to arise from a minor LIC population, exhibited a mast cell–like gene expression profile (Figure 6F). In addition, these cells also exhibited a basophil signature (supplemental Figure 15A) relative to blood cells from CML CP patients. To confirm the relationship between CD25 expression and mast cell signature, we tested another gene expression data set from B-ALL patients.22 The CD25+ B-ALL group, in which >50% of cells were positive for CD25 (43 samples of 194), exhibited mast cell– (Figure 6G) and basophil-related signatures (supplemental Figure 15B) relative to the rest of the sample. Importantly, 38 of 43 samples of CD25+ B-ALL were BCR-ABL+ ALL in this data set, underscoring the tight association of BCR-ABL with CD25 expression and a mast cell signature.

Discussion

CML LICs form 2 distinct populations distinguished by CD25 expression

Our study demonstrates that CML LICs are clearly divided into CD25+F−LSK and CD25−F−LSK subpopulations, both in a mouse model and in patient samples. In addition, our results suggest a revised model of CML pathogenesis in which CD25+F−LSK cells maintain the leukemia-initiating capacity of CML LICs (supplemental Figure 16). CD25+F−LSK and CD25−F−LSK cells are interconvertible populations of CML LICs. CD25+F−LSK cells are maintained by IL-2 from the microenvironment.

Given that CD25 is detectable neither in the normal murine LSK fraction nor in the human CD34+ fraction from undiseased bone marrow, CD25 must be expressed in a CML-specific fraction. In a transplantation model, CD25+F−LSK cells exhibited a higher capacity to propagate CML; primary transplant recipients of these cells exhibited shorter survival, and secondary recipients exhibited a higher rate of disease onset. Notably, CD25+F−LSK and CD25−F−LSK cells interconverted both ex vivo and in vivo, contradicting a widely accepted conception of LICs that implies a differentiation hierarchy and a defined stem cell fraction. To increase our understanding of the pathogenesis of CML, the “on-off” mechanism of CD25 expression should be further elucidated. Considering that CD25 is upregulated as early as 2 days following BCR-ABL transduction, it is possible that CD25 expression is regulated cell-autonomously, rather than through interactions with the microenvironment.

We demonstrated that CD25+F−LSK cells preferentially generated mast cell–like CD25+F+LSK cells, and that both CD25+F−LSK and CD25+F+LSK cells produced various cytokines, some of which were present at elevated levels in the serum (Figure 4B). Among the cytokines tested, several have been previously reported to exert trophic effects on CML LICs: IL-4, IL-6, and TGF-β.7,8 Indeed, we demonstrated that CD25+F−LSK cells facilitated maintenance of the immature phenotype of CD25−F−LSK cells, which recapitulates the effect of TGF-β on CML LSK cells. Accordingly, CD25+F−LSK cells may modulate disease progression, not only through their higher proliferative capacity, but also through the secretion of these cytokines, thus constituting an LIC niche for themselves.

The counterparts of CD25+F+LSK (mast cell–like) cells in human CML are unknown. Basophil levels increase in CML patients, but the significance of this increase remains unclear. Mast cells and basophils are functionally, developmentally, and also evolutionarily similar cell types; both are associated with anti-parasitic reactions and allergic responses24,25 and display overlapping gene expression profiles. The GSEA that we applied to human CML and B-ALL data sets revealed that both CML BC and CD25-positive B-ALL, most cases of which are positive for BCR-ABL, exhibited mast cell– and basophil-related gene expression profiles. In addition, a previously reported CML stem cell marker, IL-1 receptor accessory protein (IL1RAP),26 is essential for activation of mast cells.27 Thus, BCR-ABL may control the common genetic programming of both mast cells and basophils in human leukemia. Because peripheral basophilia is associated with poor prognosis in CML,28 it is possible that cytokines secreted from basophils modulate disease progression in human CML, just as we showed in the murine CML model.

The IL-2/CD25 axis is a potential target for therapy directed against CML LICs

We demonstrated by 2 independent means (antibodies directed against CD25 and its ligand IL-2, as well as genetic ablation of IL2ra) that targeting IL-2/CD25 is an effective strategy for treating CML. In addition, supplementation of BCR-ABL–transduced LSK cells with IL-2 maintained the BCR-ABL+LSK or CD25+F−LSK fraction and increased the size of the CD25+ fraction (Figure 4D-E; supplemental Figure 9B); likewise, IL-2 injection accelerated leukemia in CML model mice (supplemental Figure 9A). These findings are supported by the observation that IL-2 increased the colony-forming ability of human CML cells (supplemental Figure 9C). Thus, CD25 is not merely an aberrantly expressed marker, but is instead functionally essential for maintaining CML LICs.

Given that the serum IL-2 level was not elevated in murine CML samples, the underlying mechanism of how CD25 transduces its signal and enhances disease progression remains uncertain. One possibility is that IL-2 produced by cells in the microenvironment is transmitted to CML cells. Indeed, some CML CD25+F−Lin− cells colocalized closely with IL-2+Lin+ cells in bone marrow (Figure 4C), consistent with the idea that microenvironment-derived IL-2 functions as a supportive signal to generate more aggressive LICs in CML.

Targeting CD25 could have dual effects on LIC eradication: (1) elimination of CD25+F−LSK cells with higher LIC capacity, thereby directly inhibiting disease progression; and (2) reduction of the secretion of various cytokines from CD25+F−LSK cells, and possibly mast cell–like CD25+F+LSK cells, thereby halting the signaling circuit that explains LICs. This dual effect might explain the reason why targeting only the CD25+ fraction, but not CD25−LSK cells, was effective. In support of this idea, we observed a beneficial effect of combination therapy using TKI and anti-CD25 mAb (supplemental Figure 13).

We showed that CD25 is expressed in human CML LICs, and its expression positively correlates with CML disease progression. The high expression level of CD25 in CML BC, in which a massive expansion of the LIC fraction occurs, indicates the significance of CD25 in CML disease progression. Therefore, targeting the IL-2/CD25 axis may be effective in BC. In fact, CD25 expression predicts adverse outcomes of AML and B-ALL patients,13,14,22,29,30 underscoring the relevance of the IL-2/CD25 axis in leukemogenesis. Our results suggest that the addition of anti-CD25 agents to the current standard therapy would be a promising strategy for achieving complete eradication of CML LICs.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is an Inside Blood commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank T. Kitamura for providing PlatE cells, A. Hirao and K. Naka for the CML model, M. Suematsu for fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis, and T. Muraki, K. Endo, and T. Hirose for technical support and laboratory management.

K.T. was supported by the Tenure-Track Program at the Sakaguchi Laboratory, and in part by a MEXT Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (A). T. Suda and K.T. were supported in part by a MEXT Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (A) and a MEXT Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas.

H.K., C.I.K., and A.N.-I. were research fellows of Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

Authorship

Contribution: C.I.K. and K.T. performed experiments, analyzed data, and cowrote the manuscript; H.K., A.N.-I., H.H., H.A., and T. Sudo performed experiments and analyzed data; K. Kataoka, K. Kumano, and M.K. supported the human cell experiments; T. Suda cowrote the manuscript; and K.T. and T. Suda designed and supervised the project.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: M.K. received research funding, lecture fees, and advisory fees from Novartis Pharmaceuticals, and research funding, lecture fees, and advisory fees from Bristol-Myers. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Keiyo Takubo, Department of Cell Differentiation, The Sakaguchi Laboratory of Developmental Biology, Keio University School of Medicine, 35 Shinano-machi, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo 160-8582, Japan; e-mail: keiyot@gmail.com; and Toshio Suda, Department of Cell Differentiation, The Sakaguchi Laboratory of Developmental Biology, Keio University School of Medicine, 35 Shinano-machi, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo 160-8582, Japan; e-mail: sudato@z3.keio.jp.

References

Author notes

C.I.K. and K.T. contributed equally to this work.

![Figure 1. CD25 expression marks distinct subsets of cells in the CML LIC population. (A) Screening strategy for antigens differentially expressed on CML LSK cells. LSK cells were transduced with BCR-ABL retroviral vector and transplanted into recipient mice. Bone marrow cells were collected 10 to 12 days after transplantation, and staining patterns of candidate antigens in 3 types of cells (BCR-ABL+LSK, LKS−, and BCR-ABL−LSK) were analyzed by flow cytometry. (B) CD25+ cells in the 3 cell types in panel A (%) (means ± standard deviation [SD], n = 3). (C) Flow cytometric analysis of CD25 expression in normal bone marrow fractions, including LSK, GMP (Lin−c-Kit+Sca-1−CD34+FcγRII/III+), and CD4+ cells (orange histograms). Gray histograms indicate isotype control staining. Numbers indicate the CD25-positive fraction (means ± SD, n = 3). (D) Flow cytometric analysis of BCR-ABL+LSK cells from CML model mice costained with CD25 and FcεRIα. Giemsa-stained cytospin specimens of the 3 fractions (CD25+F+LSK, CD25+F−LSK, and CD25−F−LSK cells) are shown. Images were obtained and analyzed using a microscope (IX70; Olympus). UPlanApo 40×/0.85 objective lens (Olympus) and DP Controller (Olympus). (E) qPCR analysis of mast cell–related genes in the indicated fractions from CML model mice (means ± SD, n = 4). *P < .05; **P < .01.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/123/16/10.1182_blood-2013-07-517847/4/m_2540f1.jpeg?Expires=1769090040&Signature=n69cW7dQShAjho2qdRkuo9ztC3NOuHKPxR4pB0hT9xG0i4QtbtmKVyinHGQms77wo0BuHaeCMBwbd2Uz4x8M5RfpJqrFcj5Eyl3OUX3AU7lhiVDCaFwWGBLpUNEWQVozjZ9fiTNdTi4D0--TOetBZ6XKJMGtcFk-C8N88E6AbYXAnDKhEHHDNLjMhvpnOjGq-hGmtkCAZZ6QILqEGD2YFNkrhTONmlYmrt3TvuPOC8DC-yw~sEyMR4rc7sagZ4zMEAKOUhhiUtslyeH1BtTb6P0S6D9F5oAjj6eJR3Hq~J21OXbdlmql2p8gudPRJUYMGDTQSPwqEjOJasWQ5Yi-YQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal