Key Points

cIAPs and XIAP negatively regulate cytokine production, including TNF to disrupt myeloid lineage differentiation.

IAPs prevent RIPK1 and RIPK3 activity to limit cytokine production prior to cell death.

Abstract

Loss of inhibitor of apoptosis proteins (IAPs), particularly cIAP1, can promote production of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and sensitize cancer cell lines to TNF-induced necroptosis by promoting formation of a death-inducing signaling complex containing receptor-interacting serine/threonine-protein kinase (RIPK) 1 and 3. To define the role of IAPs in myelopoiesis, we generated a mouse with cIAP1, cIAP2, and XIAP deleted in the myeloid lineage. Loss of cIAPs and XIAP in the myeloid lineage caused overproduction of many proinflammatory cytokines, resulting in granulocytosis and severe sterile inflammation. In vitro differentiation of macrophages from bone marrow in the absence of cIAPs and XIAP led to detectable levels of TNF and resulted in reduced numbers of mature macrophages. The cytokine production and consequent cell death caused by IAP depletion was attenuated by loss or inhibition of TNF or TNF receptor 1. The loss of RIPK1 or RIPK3, but not the RIPK3 substrate mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein, attenuated TNF secretion and thereby prevented apoptotic cell death and not necrosis. Our results demonstrate that cIAPs and XIAP together restrain RIPK1- and RIPK3-dependent cytokine production in myeloid cells to critically regulate myeloid homeostasis.

Introduction

A well-characterized function of inhibitor of apoptosis proteins (IAPs) is their ability to block cell death. XIAP binds to and inhibits effector caspases and the initiator caspase, caspase-9, and is therefore a direct apoptosis inhibitor.1 Unsurprisingly, compounds that mimic natural inhibitors of IAPs, such as Smac/DIABLO, were developed as antitumor agents. Unlike XIAP, cIAP1 and cIAP2 do not directly inhibit caspases2 but instead promote prosurvival signaling from tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR) 1 complex I and also limit formation of the apoptosis-inducing TNFR1 complex II.3-5 Several Smac mimetics have been developed, and pan-IAP inhibitors were shown to kill tumor cells by causing cIAP1/2 degradation, leading to spontaneous activation of nuclear factor κB and consequent autocrine/paracrine tumor necrosis factor (TNF)/TNFR1-induced cell death signaling.6-9

The observation that Smac mimetics trigger TNF production in certain tumor cells suggests that IAPs regulate cytokines, and in some cell types, this is critical for proper regulation of cell death. Monocytes and macrophages treated with Smac mimetics die in a TNF/TNFR1-dependent manner that requires receptor-interacting serine/threonine-protein kinase (RIPK) 1 signaling.10,11 By contrast, single loss of cIAPs or XIAP has been shown to reduce cytokine production after stimulation of Nucleotide-binding and oligomerization domain 1 (NOD1), NOD2, Toll-like receptors (TLRs), or TNF,12-16 contrary to observations made using Smac mimetics. To add to the confusion, mutations in XIAP have been found in X-linked lymphoproliferative syndrome and in a case study of inflammatory bowel disease symptoms,17,18 suggesting that inactivity or a lack of XIAP triggers chronic inflammation in vivo.

Death domain–containing members of the TNFR superfamily and pattern recognition receptor family members (TLR) can not only induce caspase-dependent apoptosis but also trigger programmed necrosis, also known as necroptosis, in certain contexts.19 Stimulation of death receptors or TLRs normally triggers apoptosis, but in the absence of caspase-8 function, this instead elicits RIPK3-dependent necroptosis. RIPK3-dependent phosphorylation of mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein (MLKL) and phosphoglycerate mutase family member 5 (PGAM5) was reported to be required for necroptosis induction, and although the subsequent molecular necroptotic signaling events remain unclear, increased mitochondrial fission and reactive oxygen species production have been implicated.20-22 Smac mimetic–mediated IAP depletion causes the formation of a RIPK1, caspase-8, and Fas-Associated protein with Death Domain (FADD)-containing complex that has been named the Ripoptosome1,23-26 and is thought to cause necroptotic cell death. Moreover, recent evidence suggests that TNF production triggered by loss of cIAPs or pharmacologic inhibition of caspases is regulated by RIPK1, at least in L929 cells.2,27

We generated gene-targeted mice to determine the role of cIAPs and XIAP in cytokine production in the myeloid lineage. We found that cIAPs and XIAP together suppress the production of multiple cytokines and chemokines, including TNF, thereby regulating the homeostasis and function of mature myeloid cells. In contrast to tumor cells, in which loss of cIAPs alone causes TNF production and TNF/TNFR1-mediated cell killing, combined loss of XIAP and cIAPs was required for TNF induction and TNF/TNFR1-mediated killing of macrophages. TNF messenger RNA (mRNA) production was dependent on RIPK1, and secretion of TNF was dependent on RIPK3. These findings suggest that RIPK1 and RIPK3 regulate cytokine production directly and this function resides upstream of, and distinct from, the role of these 2 kinases in the induction of necroptosis.

Materials and methods

Mice

Mice were maintained in a conventional animal facility, and experiments performed according to the guidelines of La Trobe University Ethics committee (09-41B and 09-57B) and the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research (WEHI) Animal Ethics Committee. loxP and FRT sites were introduced into the adjacent cIap1 and cIap2 genes by sequential gene targeting in C57BL/6-derived embryonic stem (ES) cells.3-5,28 Ubiquitous inactivation of cIAP2 expression was achieved by Flpe transgene (B6;SJL-Tg:F4[ACTFLPe]9205Dym/WEHI) (cIap1fl/flcIap2−/−). These mice were intercrossed with transgenic Cre mice, inserted by homologous recombination into the lysozyme M locus (LysM-Cre: B6.129; CB.20-Tg; F6[LysM-Cre]/WEHI) mice,6-9,29 thus producing animals with myeloid cell–specific inactivation of cIAP1 (cIap1flflcIap2−/−, LysMcre/+= c1LCc2−/−). Animals were further intercrossed with Xiap−/− mice (B6.129:F10-XIAPTm1/WEHI). Ripk1−/−,30 Ripk3−/−,31 TNFR1−/−, and TNFR2−/− mice were originally generated on a 129/SV genetic background and backcrossed to C57Bl/6 mice for at least 8 generations. Tnf−/− and Mlkl−/− mice were generated on a C57BL/6 background.32 Bone marrow reconstitutions of Ripk1−/− fetal liver on the C57BL/6.129 background failed to produce >95% reconstitution efficiency, resulting in the use of fetal livers from timed matings to produce Ripk1−/− macrophages. Wild-type (WT), Ripk3−/−, and Tnf−/− mice were injected with Smac mimetic (Abbott11) at 20 mg/kg single dose or over 2 weeks (5 days on/2 days off), and cell types were assessed. cIap1lysCrecIAP2−/−Xiap−/− mice (c1LCc2−/−X−/−) from 3 weeks of age were injected with anti-TNF (MP6-XT22, 10 mg/kg) for 3 weeks, 3 times per week.

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometry was performed on a FacsCanto (BD Biosciences) with FacsDiva software (BD Biosciences) or LSR1 with Cell Quest software (BD Biosciences), and data processing performed using Weasel (WEHI). Single-cell suspensions were prepared from spleens and bone marrow. Spleen cell suspensions were subjected to erythrocyte depletion using red blood cell lysis buffer. Approximately 2 × 106 cells were stained, and antibodies and gating strategies used are provided in supplemental Materials and methods (see the Blood Web site). Dead cells were excluded from analysis by staining with propidium iodide (PI; 2 µg/mL). In vitro cell survival assays were performed as previously described.9-11

Compounds and antibodies

Smac mimetic compounds/pan-IAP inhibitors Compound A (Comp. A; GT12911), cIAP1/cIAP2 specific inhibitor (TL32711), and Abbott11 were synthesized by TetraLogic Pharmaceuticals. Other compounds used were QVD-OPH (MP Biomedicals) and necrostatin-1 (Nec-1; Biomol). Rat anti-mouse TNF (MP6-XT22) and isotype control (GL113) were purchased from WEHI monoclonal laboratory.

Cell culture

Cell suspensions from bone marrow were cultured for 6 days in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium + 10% fetal bovine serum (volume to volume ratio) + 20% (volume to volume ratio) L929 mouse fibroblast conditioned medium. The resulting bone marrow–derived macrophages (BMDMs) were then replated at 1 × 106 cells per mL and assayed in the presence of L929 conditioned medium. Peritoneal macrophages were obtained 4 days after injection with 1% thioglycollate (weight to volume ratio), sorted for Mac1+Gr1– cells, and assayed for sensitivity to Smac mimetic–induced cell killing. Fetal liver–derived macrophages (FLDMs) were obtained by culturing fetal liver–derived cells from E14.5 fetuses in a manner similar to the bone marrow–derived cells (as described previously).

Cytokine measurement

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) for the measurement of the concentrations of TNF, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), macrophage CSF (M-CSF), granulocyte macrophage CSF (GM-CSF), interleukin (IL) 1β, and IL-6 were performed following the manufacturers’ instructions (R&D Research and eBioscience, respectively). The 23-plex mouse cytokine assays (Bio-Rad) were performed following the manufacturer’s instructions and assayed on a Bio-Rad Bioplex machine.

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

Relative levels of target genes were determined using relative comparative threshold cycle to assess TNF mRNA levels with β2-microglobulin as the housekeeping gene using SYBR Green (Life Technologies). Primer sequences are available upon request. Viia7 was used to perform quantitative PCR (Life Technologies).

Histology

Organs were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, paraffin embedded, and sectioned for hematoxylin and eosin or subjected to heat-induced epitope retrieval with citrate buffer, blocked in 3% goat serum, permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X-100, and stained with cleaved caspase-3 (Cell Signaling Technology). Images were taken using a Widefield Leica DMI 6000 with a digital color camera Leica DFC 420 or Mirax slide scanner with 3CCD color camera, and processed using Panoramic Viewer.

Hematopoietic cell colony assays

Single-cell suspensions from bone marrow or spleens from newborn pups (day 1-4) were resuspended in 0.3% (weight to volume ratio) agar and Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium + 20% fetal bovine serum at a concentration of 2.5 × 104 cells per plate. Cells were incubated with 10 ng/mL recombinant murine (rm) GM-CSF, rm M-CSF, or recombinant human G-CSF alone or in combination, in addition to 25 ng/mL rm IL-3, 2 U/mL erythropoietin, and 100 ng/mL rm stem cell factor for 7 days at 37°C. On day 7, colonies were fixed and stained for counting.

Blood cell analysis

Blood was collected from the retro-orbital plexus into tubes containing potassium ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (Sarstedt) and analyzed in an Advia 2120 automated hematologic analyzer (Bayer).

Statistical analysis

Cytokine measurements were assessed individually by Student t tests for single genotypes. Analysis of variance was performed followed by Bonferroni posttests to compare individual genotypes or conditions.

Results

Combined loss of XIAP and cIAPs in myeloid cells results in inflammation

To determine the effects of selective loss of XIAP and cIAPs in the myeloid lineage in vivo, we generated cIap1fl/flcIap2FRT/FRTXiap−/− mice using a lysozyme M-promoter–driven Cre transgene12-16,29 and a ubiquitously expressed FLPe transgene.17,18,33 In these cIap1lysCrecIAP2−/−Xiap−/− mice (c1LCc2−/−X−/−), XIAP and cIAP2 are deleted in all cell types, whereas cIAP1 is selectively lost in the myeloid lineage: granulocytes, macrophages, and a minor fraction of dendritic cells.19,34 Although c2−/−X−/− mice are phenotypically normal, the c1LCc2−/−X−/− mutant mice were runted compared with littermate controls and had a splayed gait and hunched posture (Figure 1A-B).

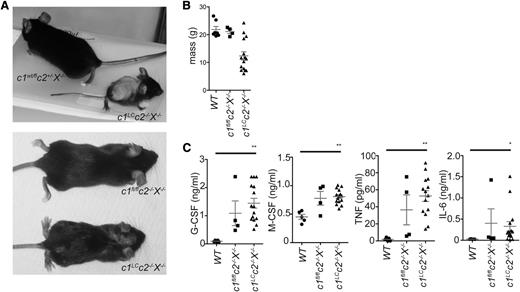

Specific combined loss of cIAPs and XIAP in the myeloid lineage results in chronic inflammation. (A) Image of a c1LCc2−/−X−/− mouse (deficient for cIAP1 only in myeloid cells and deficient for cIAP2 and XIAP in all tissues) and a littermate mouse. (B) Weights of c1LCc2−/−X−/−, c1fl/flc2−/−X−/−, and WT mice. (C) Levels of G-CSF, M-CSF, TNF, and IL-6 in the sera of c1LCc2−/−X−/−, c1fl/flc2−/−X−/−, and WT mice. Each point represents an individual mouse. Mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) are shown. **P < .01; *P < .05.

Specific combined loss of cIAPs and XIAP in the myeloid lineage results in chronic inflammation. (A) Image of a c1LCc2−/−X−/− mouse (deficient for cIAP1 only in myeloid cells and deficient for cIAP2 and XIAP in all tissues) and a littermate mouse. (B) Weights of c1LCc2−/−X−/−, c1fl/flc2−/−X−/−, and WT mice. (C) Levels of G-CSF, M-CSF, TNF, and IL-6 in the sera of c1LCc2−/−X−/−, c1fl/flc2−/−X−/−, and WT mice. Each point represents an individual mouse. Mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) are shown. **P < .01; *P < .05.

Sera from 6- to 12-week-old c1LCc2−/−X−/−, c1fl/flc2−/−X−/−, and WT mice were assayed for cytokines by ELISA or multiplex. G-CSF, M-CSF, TNF, and IL-6 (measured by ELISA) were elevated in c1LCc2−/−X−/− animals compared with WT controls (P < .01, G-CSF, M-CSF, and TNF and P < .01, IL-6; Figure 1C). Of the 23 cytokines assayed in a multiplex format, 10, including IL-12p40, Eotaxin, monocyte chemotactic protein 1 (MCP1), and regulated on activation normal T expressed and secreted, were significantly higher in the c1LCc2−/−X−/− mice compared with the control animals (supplemental Figure 1). Some cytokines and chemokines also appeared to be abnormally elevated in the sera of c2−/−X−/− mice, but the loss of all 3 IAPs caused the greatest increase in the levels of cytokines and chemokines, including IL-1β, G-CSF, M-CSF, and TNF. In contrast, mice deficient in a single IAP, whether it was cIAP1, cIAP2, or XIAP, did not display abnormally increased levels of any of the cytokines or chemokines tested (data not shown).

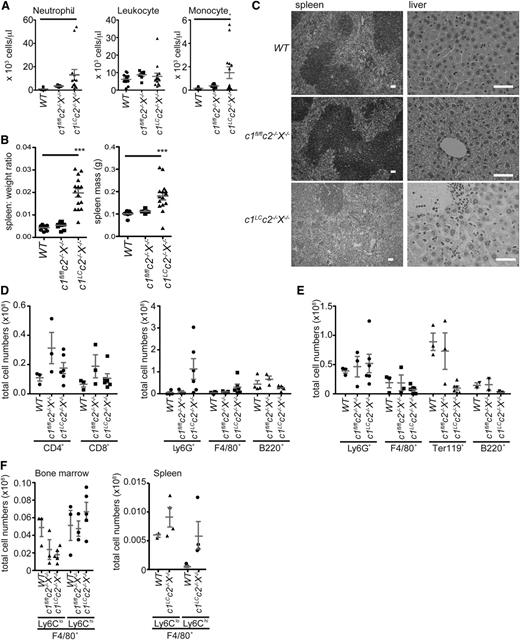

Deletion of cIAPs and XIAP causes granulocytosis and splenomegaly

c1LCc2−/−X−/− mice presented with granulocytosis and splenomegaly, characterized by loss of splenic architecture (Figure 2A-C). In addition to the altered spleen structure, signs of inflammation were observed in liver and lung (Figure 2C and supplemental Figure 2A). The enlarged spleen was the result of an increase in cell numbers, particularly Ly6G+ neutrophils (Figure 2D and supplemental Figure 2). The femur and tibia of c1LCc2−/−X−/− mice were pale, small, and brittle, and analysis of the cellular content showed a slight increase in granulocytes, a decrease in F4/80+ monocytes and B220+ B cells, and a lack of erythroid cells (Ter119+) (Figure 2E). c1LCc2−/−X−/− mice showed a decrease in resident F4/80+Ly6Clo monocytes and an increase in inflammatory F4/80+Ly6Chi monocytes in the bone marrow compared with WT and c1fl/flc2−/−X−/− mice. Skewing toward an inflammatory phenotype in c1LCc2−/−X−/− mice was further highlighted by increased numbers of F4/80+ monocyte/macrophage subsets in the spleen, particularly the inflammatory subset (Figure 2F). Myeloid populations were sorted and assessed for effective deletion of cIAP1 (supplemental Figure 2C). cIAP1 was effectively deleted from granulocytes (Ly6G+ cells) but not from F4/80+Ly6Clo cells, and the effectiveness of cIAP1 deletion varied in c1LCc2−/−X−/− mice (supplemental Figure 2D). This suggests that the variation in phenotype may be attributable to the effectiveness of cIAP1 deletion by lysozyme M cre.

Combined loss of cIAPs and XIAP in the myeloid lineage causes granulocytosis, splenomegaly, and extramedullary hematopoiesis. (A) The numbers of neutrophils, monocytes, and total leukocytes per microliter of blood in c1LCc2−/−X−/−, c1fl/flc2−/−X−/−, and WT mice were determined by using an automated ADVIA blood analyzer. (B) The ratios of the spleen to total body weight, as well as the spleen weights of 6- to 12-week-old c1LCc2−/−X−/− and control (WT, c1fl/flc2−/−X−/−) mice were determined by weighing the mice and their spleens. (C) Splenic architecture and liver histology of WT, c1fl/flc2−/−X−/−, and c1LCc2−/−X−/− mice. The bars represent 50 µm; ×10, numerical aperture (NA) 0.3 and ×40, NA 0.6 magnification, respectively. (D) Total numbers of CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, total B cells (B220+), granulocytes (Ly6G+), and macrophages (F4/80+) in spleens of 6- to 12-week-old c1LCc2−/−X−/− as well as control (WT, c1fl/flc2−/−X−/−) mice were determined by counting total leukocytes in these tissues and multiplying them with the percentages of these cell subsets that were determined by flow cytometric analysis. (E) The numbers of erythroid (TER119+), B lymphoid (B220+), granulocytic (Ly6G+), and macrophage/monocyte (F4/80+) cells in the bone marrow of c1LCc2−/−X−/− and control (WT, c1fl/flc2−/−X−/−) mice were determined as in panel C. (F) The numbers of F4/80+ cells were further assessed as resident (Ly6Clo) or inflammatory (Ly6Chi) in the bone marrow and spleen of c1LCc2−/−X−/−, c1fl/flc2−/−X−/−, and/or WT mice. In panels B-F, each data point represents an individual mouse (6-12 weeks old); the mean ± SEM are also shown. **P < .01; *P < .05.

Combined loss of cIAPs and XIAP in the myeloid lineage causes granulocytosis, splenomegaly, and extramedullary hematopoiesis. (A) The numbers of neutrophils, monocytes, and total leukocytes per microliter of blood in c1LCc2−/−X−/−, c1fl/flc2−/−X−/−, and WT mice were determined by using an automated ADVIA blood analyzer. (B) The ratios of the spleen to total body weight, as well as the spleen weights of 6- to 12-week-old c1LCc2−/−X−/− and control (WT, c1fl/flc2−/−X−/−) mice were determined by weighing the mice and their spleens. (C) Splenic architecture and liver histology of WT, c1fl/flc2−/−X−/−, and c1LCc2−/−X−/− mice. The bars represent 50 µm; ×10, numerical aperture (NA) 0.3 and ×40, NA 0.6 magnification, respectively. (D) Total numbers of CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, total B cells (B220+), granulocytes (Ly6G+), and macrophages (F4/80+) in spleens of 6- to 12-week-old c1LCc2−/−X−/− as well as control (WT, c1fl/flc2−/−X−/−) mice were determined by counting total leukocytes in these tissues and multiplying them with the percentages of these cell subsets that were determined by flow cytometric analysis. (E) The numbers of erythroid (TER119+), B lymphoid (B220+), granulocytic (Ly6G+), and macrophage/monocyte (F4/80+) cells in the bone marrow of c1LCc2−/−X−/− and control (WT, c1fl/flc2−/−X−/−) mice were determined as in panel C. (F) The numbers of F4/80+ cells were further assessed as resident (Ly6Clo) or inflammatory (Ly6Chi) in the bone marrow and spleen of c1LCc2−/−X−/−, c1fl/flc2−/−X−/−, and/or WT mice. In panels B-F, each data point represents an individual mouse (6-12 weeks old); the mean ± SEM are also shown. **P < .01; *P < .05.

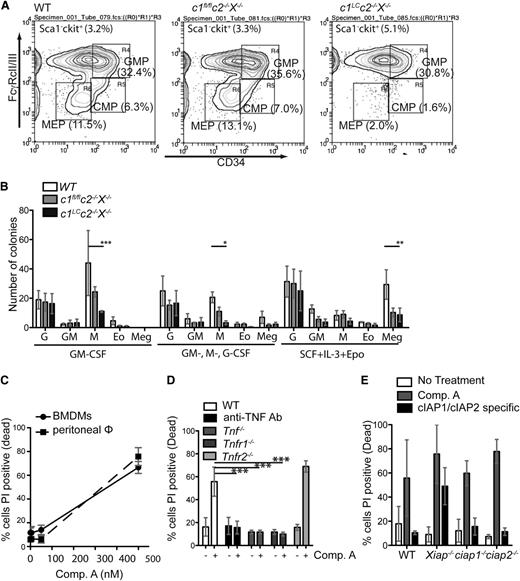

Combined loss of cIAPs and XIAP does not impair myeloid cell differentiation but impairs macrophage survival

To determine the effect of abnormally high cytokine levels on myeloid homeostasis, we examined the numbers of myeloid progenitors in the bone marrow. c1LCc2−/−X−/− mice had substantially reduced numbers of common myeloid and megakaryocyte erythroid progenitors, but not granulocyte macrophage progenitors, in their bone marrow compared with littermate controls (Figure 3A and supplemental Figure 3).

Combined loss of cIAPs and XIAP does not impair myeloid cell differentiation but impairs survival of cells in macrophage colonies. (A) Representative fluorescence-activated cell sorter plots with percentages of surface marker staining to identify myeloid progenitors in the bone marrow of WT, c1fl/flc2−/−X−/−, and c1LCc2−/−X−/− mice. Cells were gated for Sca1–c-kit+ and further gated for FcγRcII/III and CD34 (CMP, common myeloid progenitor; GMP, granulocyte macrophage progenitor; MEP, megakaryocyte erythrocyte progenitor). (B) Spleen cells from newborn WT, c1fl/flc2−/−X−/−, and c1LCc2−/−X−/− mice were plated in agar with either GM-CSF, Multi-CSF (GM-, G-, M-CSF), or stem cell factor (SCF) + IL-3 + Epo, and the numbers and morphologies of the colonies (Eo, eosinophil; G, granulocytes; GM, granulocyte-macrophage; M, macrophage; Meg, megakaryocyte) determined after 7 days. N = 3 biological replicates. (C) BMDMs and peritoneal macrophages were treated with the indicated concentrations of the Smac mimetic Comp. A and assayed 24 hours for cell death by flow cytometry. (D) BMDMs from mice of the indicated genotypes were either left untreated (-) or treated with Comp. A (500 nM, 24 hours; +). The percentages of dead cells were determined by flow cytometric analysis after staining with PI. N = 3 experiments with BMDMs from individual mice. (E) BMDMs from mice of the indicated genotypes were left untreated (open bars) or treated for 24 hours with either 500 nM Comp. A, a Smac mimetic that inhibits all of cIAP1, cIAP2, and XIAP, or with 500 nM of a Smac mimetic that only inhibits cIAP1 and cIAP2. The percentages of dead cells were determined by staining with PI followed by flow cytometric analysis. N = 3 experiments with BMDMs from individual mice of the genotypes indicated. Mean ± SEM are shown. **P < .01; *P < .05.

Combined loss of cIAPs and XIAP does not impair myeloid cell differentiation but impairs survival of cells in macrophage colonies. (A) Representative fluorescence-activated cell sorter plots with percentages of surface marker staining to identify myeloid progenitors in the bone marrow of WT, c1fl/flc2−/−X−/−, and c1LCc2−/−X−/− mice. Cells were gated for Sca1–c-kit+ and further gated for FcγRcII/III and CD34 (CMP, common myeloid progenitor; GMP, granulocyte macrophage progenitor; MEP, megakaryocyte erythrocyte progenitor). (B) Spleen cells from newborn WT, c1fl/flc2−/−X−/−, and c1LCc2−/−X−/− mice were plated in agar with either GM-CSF, Multi-CSF (GM-, G-, M-CSF), or stem cell factor (SCF) + IL-3 + Epo, and the numbers and morphologies of the colonies (Eo, eosinophil; G, granulocytes; GM, granulocyte-macrophage; M, macrophage; Meg, megakaryocyte) determined after 7 days. N = 3 biological replicates. (C) BMDMs and peritoneal macrophages were treated with the indicated concentrations of the Smac mimetic Comp. A and assayed 24 hours for cell death by flow cytometry. (D) BMDMs from mice of the indicated genotypes were either left untreated (-) or treated with Comp. A (500 nM, 24 hours; +). The percentages of dead cells were determined by flow cytometric analysis after staining with PI. N = 3 experiments with BMDMs from individual mice. (E) BMDMs from mice of the indicated genotypes were left untreated (open bars) or treated for 24 hours with either 500 nM Comp. A, a Smac mimetic that inhibits all of cIAP1, cIAP2, and XIAP, or with 500 nM of a Smac mimetic that only inhibits cIAP1 and cIAP2. The percentages of dead cells were determined by staining with PI followed by flow cytometric analysis. N = 3 experiments with BMDMs from individual mice of the genotypes indicated. Mean ± SEM are shown. **P < .01; *P < .05.

To determine whether the loss of cIAP2 and XIAP in all tissues contributed to the severe pathology of the c1LCc2−/−X−/− mice, WT (C57BL/6-Ly5.1) mice were lethally irradiated and reconstituted with bone marrow from WT or c1LCc2−/−X−/− mice (both on a C57BL/6-Ly5.2 background). Mice reconstituted with a c1LCc2−/−X−/− hematopoietic system consistently showed the pathology seen in c1LCc2−/−X−/− mice suggesting that the pathology is attributable to a hematopoietic cell intrinsic defect (supplemental Figure 3).

To examine whether the potential of myeloid progenitors was altered in c1LCc2−/−X−/− mice, we performed colony assays. In response to several cytokines, including G-CSF and Multi-CSF, spleen cells from c1LCc2−/−X−/− mice produced lower numbers of macrophage colonies compared with control (WT and c2−/−X−/− cells), whereas bone marrow cells were able to produce normal numbers of macrophage colonies (Figure 3B, P < .05; supplemental Figure 3). However, macrophage colonies formed from both spleen and bone marrow cells comprised dead or dying cells (data not shown), indicating a defect in macrophage survival. Consistent with the abnormal death of macrophages in colony assays, it proved difficult to generate BMDMs from c1LCc2−/−X−/− mice. Furthermore, TNF was readily detectable in the supernatants of c1LCc2−/−X−/− bone marrow cells cultured for 6 days in M-CSF but not in those from their WT or c1fl/flc2−/−X−/− counterparts (data not shown). Collectively, this demonstrates that combined loss of XIAP and cIAPs in the myeloid lineage affects myeloid cell homeostasis requiring extramedullary hematopoiesis. These results demonstrate that loss of cIAP1, cIAP2, and XIAP causes increased death of myeloid cells that may contribute to the chronic inflammation and granulocytosis that develop in the c1LCc2−/−X−/− mice.

Loss of XIAP and cIAPs kills macrophages by TNF production and activation of TNFR1-mediated cell death

BMDMs derived from c1LCc2−/−X−/− mice were selected for incomplete deletion of cIAP1, consistent with the notion that complete loss of cIAP1, cIAP2, and XIAP kills these cells. Therefore, to further explore the impact of the combined loss of cIAPs and XIAP, we used the bivalent, pan-IAP inhibitory Smac mimetic Comp. A. Treatment with Comp. A efficiently killed BMDMs and freshly isolated peritoneal macrophages from WT mice, as assessed by flow cytometric analysis of PI incorporation (Figure 3C). Consistent with previously published data,10,20-22 treatment with TNF neutralizing antibodies (MP6-XT22) or genetic loss of TNF and TNFR1, but not loss of TNFR2, rendered BMDMs resistant to Smac mimetic–induced killing (Figure 3D, P < .001).

However, in contrast to previously published data, we found that the killing of BMDMs required the loss or inhibition of XIAP in addition to blockade or loss of cIAP1 and cIAP2 because only XIAP-deficient, but not WT, BMDMs were killed by the cIAP1-plus-cIAP2 selective Smac mimetic TL32711 (P < .05, Figure 3E). In addition, although we found that all (27/27) c1LCc2−/−X−/− mice displayed runting, hunched posture and a splayed gait, only a fraction of the cIap1LCcIap2−/− (4/19; c1LCc2−/−) mice exhibited similar pathology (supplemental Table 1). Interestingly, abnormally elevated levels of cytokines and chemokines were found in sera from c1LCc2−/− animals with physical attributes similar to c1LCc2−/−X−/− mice (data not shown). This suggests that although combined loss of cIAP1 plus cIAP2 in myeloid cells is sufficient to cause chronic inflammation, complete loss of all 3 IAPs in the myeloid lineage is required for severe pathology.

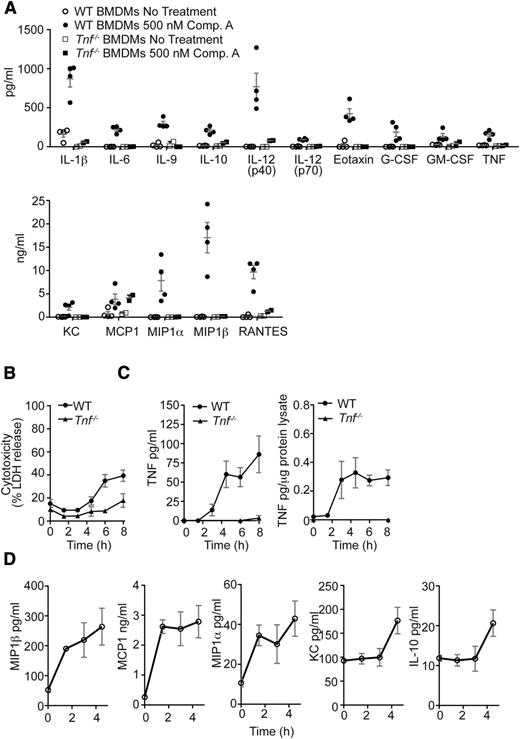

Loss of XIAP and cIAPs triggers production of certain cytokines and chemokines independent of TNF and prior to induction of cell death

To investigate whether the increase in cytokines and chemokines triggered by loss or blockade of cIAPs and XIAP might be a secondary consequence of the increased production of TNF, we treated BMDMs from WT and Tnf−/− mice with Comp. A for 24 hours. With the exception of MCP1, production of several cytokine/chemokines was dampened compared with WT macrophages (Figure 4A). These results show that Smac mimetic treatment is sufficient to directly induce production of several inflammatory cytokines, but that autocrine TNF/TNFR1 signaling is necessary for maximal production of most of these cytokines.

Smac mimetics stimulate cytokine production in macrophages prior to initiation of cell death. (A) WT or Tnf−/− BMDMs were either left untreated or stimulated in culture for 24 hours with the Smac mimetic Comp. A (500 nM). The concentrations of the cytokines indicated were measured by multiplex bead assays. N = 4 experiments with BMDMs from individual WT mice; N = 2 experiments with BMDMs of individual Tnf−/− mice. (B) LDH release was measured in supernatants of WT and Tnf−/− BMDMs after treatment with 500 nM Comp. A over 0-8 hours. N > 6 experiments with BMDMs from individual WT mice. (C) WT BMDMs were stimulated in culture for the times indicated with 500 nM Comp. A, and TNF was measured in cell lysates and supernatants. N > 3 experiments with BMDMs from individual WT mice. (D) WT BMDMs were stimulated in culture for the times indicated with 500 nM Comp. A. Culture supernatants were assayed for various cytokines by multiplex bead assay. N = 3 experiments with BMDMs from individual WT mice. Mean ± SEM are shown. **P < .01; *P < .05.

Smac mimetics stimulate cytokine production in macrophages prior to initiation of cell death. (A) WT or Tnf−/− BMDMs were either left untreated or stimulated in culture for 24 hours with the Smac mimetic Comp. A (500 nM). The concentrations of the cytokines indicated were measured by multiplex bead assays. N = 4 experiments with BMDMs from individual WT mice; N = 2 experiments with BMDMs of individual Tnf−/− mice. (B) LDH release was measured in supernatants of WT and Tnf−/− BMDMs after treatment with 500 nM Comp. A over 0-8 hours. N > 6 experiments with BMDMs from individual WT mice. (C) WT BMDMs were stimulated in culture for the times indicated with 500 nM Comp. A, and TNF was measured in cell lysates and supernatants. N > 3 experiments with BMDMs from individual WT mice. (D) WT BMDMs were stimulated in culture for the times indicated with 500 nM Comp. A. Culture supernatants were assayed for various cytokines by multiplex bead assay. N = 3 experiments with BMDMs from individual WT mice. Mean ± SEM are shown. **P < .01; *P < .05.

To determine which cytokines and chemokines were induced independently of cell death, we measured both cell death and cytokine release over time. Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release was only detectable 4.5 hours after the presence of TNF could be detected in supernatants or cell lysates (Figure 4B-C). Interestingly, LDH release also increased in Tnf−/− BMDMs treated with Smac mimetic at 8 hours, suggesting that LDH release may not fully correlate with macrophage cell death because Tnf−/− BMDMs do not die in response to Smac mimetic treatment. In WT BMDMs, poly(ADP-Ribose) polymerase (PARP) cleavage was detectable within 6 hours of Smac mimetic treatment, and the presence of High mobility group protein 1 or cyclophilin A, known damage-associated molecular pattern molecules, could be detected by 4.5-6 hours but was not limited to WT BMDMs (data not shown). Conversely, secretion of MCP1 and macrophage-inflammatory proteins 1α and 1β could already be detected within 1.5 hours of Smac mimetic treatment, whereas IL-10 and Keratinocyte-derived chemokine were only observed at 4.5 hours (Figure 4D). These results show that Smac mimetic treatment induces production of diverse inflammatory cytokines by macrophages prior to cell death.

Loss of RIPK1 or RIPK3 attenuates Smac mimetic–induced macrophage killing by limiting TNF production

Because IAPs have been shown to inhibit both caspase-dependent apoptosis and RIPK3-mediated necroptosis,25,35,36 we examined the mechanism by which Smac mimetics kill BMDMs. Although the broad-spectrum caspase inhibitor QVD-OPH effectively inhibited Smac mimetic–induced caspase-3 activation and PARP cleavage in BMDMs (data not shown), it did not prevent killing; instead, it increased the percentage of dead cells (Figure 5A). In most cellular systems, the RIPK1 inhibitor Nec-1 only blocks death receptor–induced (eg, TNFR1) cell death when it is combined with caspase inhibitors.22,24,35,37,38 It was therefore surprising that Nec-1 alone completely prevented Smac mimetic killing of BMDMs over a range of 5-50 µM (Figure 5A and data not shown). To ensure specificity of Nec-1, we treated Ripk1+/+ and Ripk1−/− FLDMs with Comp. A and found no increase in LDH release in RIPK1-deficient macrophages compared with WT or increase in percentage of dead cells as measured by PI uptake (Figure 5A and data not shown). These data were consistent with previous reports of Smac mimetics inducing necroptotic cell death,10,11 but inconsistent with our observations that cleaved caspase-3 is detectable in inflamed lung and liver histology of c1LCc2−/−X−/− mice, caspase-3 activity is induced in WT and Ripk3−/− BMDMs treated with Smac mimetic, and PARP cleavage is detected early (6 hours post Comp. A) (Figure 5B-C and data not shown; supplemental Figure 5).

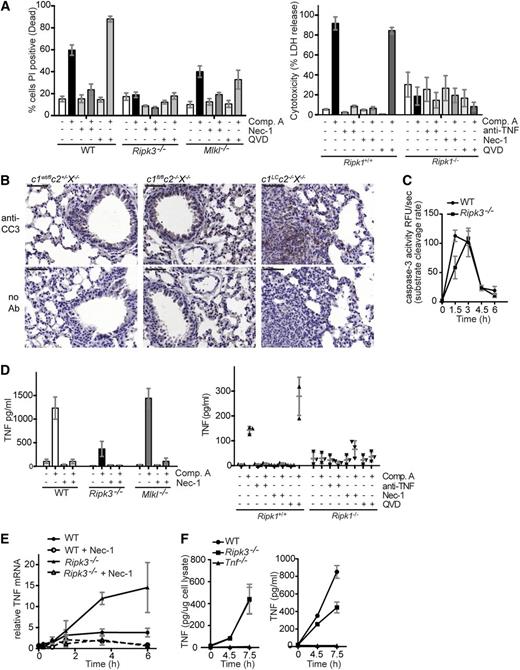

Apoptosis and not necroptosis is triggered by combined loss of cIAPs and XIAP and is dependent on RIPK1, which is critical for tnf transcription, and RIPK3, which is required for TNF secretion. (A) BMDMs of the genotypes indicated were treated for 24 hours with any of the following compounds alone or in combination: the RIPK1 inhibitor Nec-1 (50 μM), the broad-spectrum caspase inhibitor QVD-OPH (10 µM), and the Smac mimetic Comp. A (500 nM). The percentages of dead cells were determined by staining with PI followed by flow cytometric analysis. FLDMs from Ripk1+/+ and Ripk1−/− embyros were similarly treated with the exception of Nec-1 (5 µM). LDH release was measured in supernatants 24 hours after treatment. (B) Cleaved caspase-3 detected in lung histology of c1LCc2−/−X−/− mice but not littermate controls (c1wt/flc2+/−X−/−, c1fl/flc2−/−X−/−). The bars represent 50 µm; ×20 magnification, NA 0.8. (C) WT and Ripk3−/− BMDMs treated with Smac mimetic (Comp. A, 500 nM) for 0-6 hours and lysates assayed for caspase-3 activity. (D) BMDMs of the genotypes indicated were treated with Comp. A (500 nM), anti-TNF (0.1 mg/ml), Nec-1 (5 or 50 µM), and/or QVD-OPH (10 µM) for 24 hours. The levels of TNF in culture supernatants were measured by ELISA. (E) BMDMs of the genotypes indicated were treated for the times indicated with 500 nM Comp. A, either alone or together with 50 µM Nec-1 (as indicated). The levels of TNF mRNA were determined by relative quantitative PCR and expressed relative to WT BMDMs without treatment with Comp. A treatment. (F) WT, Ripk3−/−, and Tnf−/− BMDMs treated with Smac mimetic (Comp. A, 500 nM) for 0-7.5 hours. TNF in cell lysate (left) and supernatant (right) was assessed by ELISA, and the latter normalized to amount of protein. In panels A-F, N ≥ 3 experiments with BMDMs or FLDMs from individual mice or embyros of the genotypes indicated. Mean ± SEM are shown. ***P < .001; **P < .01; *P < .05.

Apoptosis and not necroptosis is triggered by combined loss of cIAPs and XIAP and is dependent on RIPK1, which is critical for tnf transcription, and RIPK3, which is required for TNF secretion. (A) BMDMs of the genotypes indicated were treated for 24 hours with any of the following compounds alone or in combination: the RIPK1 inhibitor Nec-1 (50 μM), the broad-spectrum caspase inhibitor QVD-OPH (10 µM), and the Smac mimetic Comp. A (500 nM). The percentages of dead cells were determined by staining with PI followed by flow cytometric analysis. FLDMs from Ripk1+/+ and Ripk1−/− embyros were similarly treated with the exception of Nec-1 (5 µM). LDH release was measured in supernatants 24 hours after treatment. (B) Cleaved caspase-3 detected in lung histology of c1LCc2−/−X−/− mice but not littermate controls (c1wt/flc2+/−X−/−, c1fl/flc2−/−X−/−). The bars represent 50 µm; ×20 magnification, NA 0.8. (C) WT and Ripk3−/− BMDMs treated with Smac mimetic (Comp. A, 500 nM) for 0-6 hours and lysates assayed for caspase-3 activity. (D) BMDMs of the genotypes indicated were treated with Comp. A (500 nM), anti-TNF (0.1 mg/ml), Nec-1 (5 or 50 µM), and/or QVD-OPH (10 µM) for 24 hours. The levels of TNF in culture supernatants were measured by ELISA. (E) BMDMs of the genotypes indicated were treated for the times indicated with 500 nM Comp. A, either alone or together with 50 µM Nec-1 (as indicated). The levels of TNF mRNA were determined by relative quantitative PCR and expressed relative to WT BMDMs without treatment with Comp. A treatment. (F) WT, Ripk3−/−, and Tnf−/− BMDMs treated with Smac mimetic (Comp. A, 500 nM) for 0-7.5 hours. TNF in cell lysate (left) and supernatant (right) was assessed by ELISA, and the latter normalized to amount of protein. In panels A-F, N ≥ 3 experiments with BMDMs or FLDMs from individual mice or embyros of the genotypes indicated. Mean ± SEM are shown. ***P < .001; **P < .01; *P < .05.

To determine whether Smac mimetic induced a solely necroptotic death in macrophages, we examined BMDMs derived from Ripk3−/− and Mlkl−/− mice. Smac mimetic–induced killing of BMDMs was inhibited by loss of RIPK3; however, it was only partially limited by MLKL loss. Furthermore, Comp. A–induced death of MLKL-deficient BMDMs was further reduced by Nec-1 (Figure 5A). These results strongly suggested that the kinase activity of RIPK1 has a function in addition to activating an RIPK3/MLKL necroptosis-inducing complex. We therefore examined TNF production in Ripk3−/− and Mlkl−/− mice. Surprisingly, Smac mimetic–induced TNF production was markedly reduced in both RIPK1- and RIPK3-deficient BMDMs, whereas Mlkl−/− BMDMs produced similar levels of TNF as WT cells. Cotreatment with Nec-1 and Comp. A blocked Smac mimetic–induced TNF production in WT macrophages and even those lacking RIPK3 or MLKL, suggesting that the kinase activity of RIPK1 is important for TNF production (Figure 5D).

Investigations into TNF induction in WT BMDMs revealed that TNF mRNA levels increased approximately fourfold within 6 hours of Smac mimetic treatment, whereas Nec-1 treatment prevented Smac mimetic–induced TNF mRNA production (Figure 5E). Surprisingly, loss of RIPK3, which significantly limited Comp. A–induced TNF protein production and secretion (Figure 5F), did not reduce induction of TNF mRNA. On the contrary, TNF mRNA levels were approximately threefold higher in Ripk3−/− BMDMs compared with WT BMDMs at 4.5 and 6 hours of Smac mimetic treatment (Figure 5E). The addition of Nec-1 was able to abrogate this increase in TNF mRNA in the RIPK3-deficient BMDMs (Figure 5E). Addition of Nec-1 and loss of RIPK3 similarly affected Smac mimetic–induced production of several other cytokines (supplemental Figure 4).

These observations indicate that RIPK1 and RIPK3, but not MLKL, exert distinct functions in the stimulation of cytokine production that is triggered by the loss or blockade of cIAP1/2 plus XIAP. Furthermore, the data reveal that the roles of RIPK1 and RIPK3 in cytokine production and cell death are distinct processes.

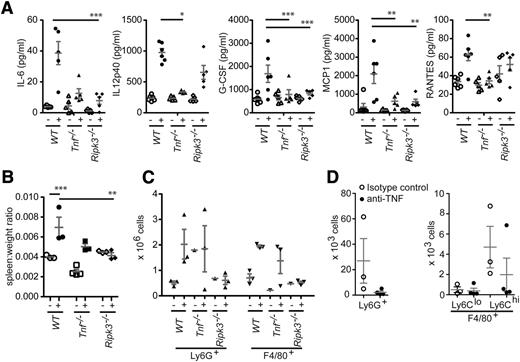

Smac mimetic treatment causes an increase in cytokine levels in vivo, and this can be attenuated by loss of TNF or RIPK3

To investigate whether administration of Smac mimetic in vivo recapitulates the c1LCc2−/−X−/− inflammatory phenotype and how IAPs repress cytokine production, we injected WT, Tnf−/−, and Ripk3−/− mice intraperitoneally with 20 mg/kg of the monovalent pan-IAP Smac mimetic compound Abbott11; this dose was previously shown to inhibit tumor growth in a murine xenograft model.39 In WT mice, the levels of IL-12, G-CSF, MCP1, IL-6, and regulated on activation normal T expressed and secreted all rose within 5 hours (Figure 6A). In agreement with our in vitro studies (Figure 4A and supplemental Figure 4), we found that the induction of these cytokines was greatly attenuated in Ripk3−/− mice and almost absent in Tnf−/− mice (Figure 6A). The detection of fewer cytokines in the serum compared with in vitro (Figure 4A) is likely attributable to the effectiveness of a monovalent vs bivalent pan-IAP Smac mimetic compound to inhibit cIAPs and XIAP.

RIPK3 is essential for the cytokine production and ensuing granulocytosis that are caused by the combined loss of cIAPs and XIAP. (A) WT mice were either left untreated (-) or injected intraperitoneally (+) with the Smac mimetic compound Abbott11 (20 mg/kg body weight). After 5 hours, the levels of the cytokines and chemokines indicated were measured by multiplex. (B-C) Mice of the genotypes indicated were either left untreated (-) or injected intraperitoneally (+) with the Smac mimetic compound Abbott11 (20 mg/kg body weight) for 2 weeks (daily for 5 days, then 2 days of rest). (B) The ratios of the spleen weight to total body weight of the mice after injection of Abbott11 were compared with the ratios from untreated control animals. (C) Increased numbers of granulocytes (Ly6G+) and macrophages (F4/80+) were found in spleens of WT and Tnf−/− mice injected with Abbott11 but not in Abbott11-injected Ripk3−/−mice. (D) c1LCc2−/−X−/− mice were injected with anti-TNF (MP6-XT22, 10 mg/kg) for 3 weeks and assessed for changes in granulocyte (Ly6G+) and monocyte (F4/80+Ly6Clo and F4/80+Ly6Chi) populations in the peripheral blood. Each point represents an individual mouse. Mean ± SEM are shown. ***P < .001; **P < .01; *P < .05.

RIPK3 is essential for the cytokine production and ensuing granulocytosis that are caused by the combined loss of cIAPs and XIAP. (A) WT mice were either left untreated (-) or injected intraperitoneally (+) with the Smac mimetic compound Abbott11 (20 mg/kg body weight). After 5 hours, the levels of the cytokines and chemokines indicated were measured by multiplex. (B-C) Mice of the genotypes indicated were either left untreated (-) or injected intraperitoneally (+) with the Smac mimetic compound Abbott11 (20 mg/kg body weight) for 2 weeks (daily for 5 days, then 2 days of rest). (B) The ratios of the spleen weight to total body weight of the mice after injection of Abbott11 were compared with the ratios from untreated control animals. (C) Increased numbers of granulocytes (Ly6G+) and macrophages (F4/80+) were found in spleens of WT and Tnf−/− mice injected with Abbott11 but not in Abbott11-injected Ripk3−/−mice. (D) c1LCc2−/−X−/− mice were injected with anti-TNF (MP6-XT22, 10 mg/kg) for 3 weeks and assessed for changes in granulocyte (Ly6G+) and monocyte (F4/80+Ly6Clo and F4/80+Ly6Chi) populations in the peripheral blood. Each point represents an individual mouse. Mean ± SEM are shown. ***P < .001; **P < .01; *P < .05.

To determine whether long-term exposure to Smac mimetics could induce pathological abnormalities similar to those seen in c1LCc2−/−X−/− mice, we injected mice intraperitoneally with Abbott11 (20 mg/kg body weight) for 2 weeks, 5 days on/2 days off. Despite the reduced levels of cytokines detected in the serum of Tnf−/− mice, an increase in spleen size was still seen and was caused by increased splenic granulocytes (Ly6G+) and macrophages (F4/80+). In contrast, increased splenic cell numbers and spleen size were not observed in Ripk3−/− mice injected with Abbott11 (Figure 6B-C and data not shown). To determine if TNF/TNFR1-mediated cell death of macrophages in the c1LCc2−/−X−/− mice was the cause of the disrupted myelopoiesis, we intraperitoneally injected anti-TNF (MP6-XT22, 10 mg/kg) for 3 weeks, 3 times per week from 3 weeks of age. After anti-TNF injection, c1LCc2−/−X−/− mice had a decreased number of granulocytes and inflammatory monocytes compared with untreated c1LCc2−/−X−/− mice (Figure 6D). This suggests that production of TNF is a major player in disrupting myelopoeisis, but the splenomegaly seen in c1LCc2−/−X−/− mice may be attributable to additional cytokines either induced by TNF and cell death or directly by the loss of IAPs in the myeloid compartment.

Discussion

Our study demonstrates that cIAPs and XIAP cooperate in vivo to limit production of proinflammatory cytokines by myeloid cells and thereby prevent death of macrophages. Although some c1LCc2−/− mice presented with a phenotype comparable to that of c1LCc2−/−X−/− mice, many were indistinguishable from littermate WT controls based on weight and stature. The combined loss of XIAP, cIAP1, and cIAP2 in the myeloid lineage was required to produce high levels of inflammation, accompanied by granulocytosis and extramedullary hematopoiesis. This suggests either that IAPs have overlapping physiological roles or that they regulate the same pathway(s), but at distinct steps of myeloid differentiation. In addition, it suggests that the most influential physiological role that IAPs play is in regulating cytokine production.

The bivalent pan-IAP Smac mimetic compounds BV6 and SM-164 were shown to efficiently kill human monocytes and BMDMs, respectively.10,11 The BV6-induced death of human monocytes was associated with loss of XIAP and could not be entirely blocked by the RIPK1 inhibitor Nec-1. In this way, BV6-treated human monocytes resembled c1LCc2−/−X−/− BMDMs, which were sensitive to killing by TNF alone, a death process that could only be partially inhibited by Nec-1 (data not shown). Similar to others,10 we found that Smac mimetic–induced killing of macrophages was dependent on autocrine TNF/TNFR1 signaling but determined that this signaling led to an apoptotic, and not necrotic, cell death. Blocking TNF in vivo decreased granulocyte numbers and inflammatory monocytes in c1LCc2−/−X−/− mice suggesting that TNF and the cell death in IAP-depleted myeloid cells is one of the main components to disrupting myeloid homeostasis. The complex phenotype seen by genetic deletion of cIAPs and XIAP may be attributable to the combination of apoptosis and subsequent necrosis attributable to damage-associated molecular pattern molecules and proinflammatory cytokines other than TNF (supplemental Figure 6).

Injection of the monovalent pan-IAP blocking Smac mimetic compound Abbott1139 was well tolerated in the mice at 20 mg/kg for single or multiple injections. An increase in the concentration of proinflammatory cytokines ensued 5 hours post Smac mimetic injection, but after 24 hours, the levels of cytokines returned to baseline (data not shown). In addition, examination of myelopoiesis following repeated injections of Abbott11 revealed splenomegaly (Figure 6B) and abnormalities in hematopoiesis, suggesting that long-term treatment of a pan-IAP Smac mimetic compound may lead to inflammatory consequences akin to that observed in c1LCc2−/−X−/− mice. The IAP selective Smac mimetic TL32711, which targets cIAP1/2, only caused death in BMDMs deficient in XIAP, leaving WT BMDMs viable. Therefore, this suggests that a selective Smac mimetic compound would be better tolerated, but it remains to be seen if these compounds will retain significant antitumor activity in vivo.

Our results show that combined loss of cIAP1/2 and XIAP causes an abnormal increase in cytokine/chemokine production and not all the effects seen in vivo can be rescued by loss of TNF (Figure 6). Our findings agree with Kearney et al16 that cIAPs and XIAP directly regulate other cytokines in addition to TNF. We recently found that in lipopolysaccharide-primed macrophages, cIAP1/2 and XIAP inhibit NOD-like receptor family, pyrin domain containing 3-caspase-1 inflammasome and caspase-8 activation of IL-1β.40 In contrast to the essential role of RIPK1 kinase activity for TNF production upon IAP removal, lipopolysaccharide and Smac mimetic–induced activation of IL-1β was not blocked by Nec-1 or TNF deficiency.40 IL-1β was detected in the sera of c1LCc2−/−X−/− mice and supernatants of Smac mimetic–treated WT BMDMs, but this appears to be a consequence of TNF production and/or macrophage cell death because Smac mimetic–induced IL-1β secretion was severely reduced from TNF-deficient macrophages.

Our data support the model whereby RIPK1 and RIPK3 can facilitate the production of multiple cytokines, independent of their role in necroptosis. This is further emphasized by the observation that upon Smac mimetic treatment, MLKL-deficient BMDMs upregulated TNF comparable to WT BMDMs (Figure 5D). This alternative role of RIPK1 and RIPK3 may be critical for amplifying the necroptotic pathway. Therefore, the ability of genetic loss of RIPK1 or RIPK3 to prevent the embryonic lethality and chronic inflammation caused by systemic or tissue selective deletion of FADD or caspase-841-43 might in part be attributable to loss of a cytokine signaling amplification loop that depends on the RIPKs rather than solely being a consequence of a block in necroptotic signaling.

The survival defect of cIAP- and XIAP-deficient macrophages, production of cytokines and the disruption in myeloid homeostasis caused by loss of cIAPs and XIAP, is reminiscent of the consequences of caspase-8 or cellular FLICE-inhibitory protein (cFLIP) loss in the myeloid lineage. Tissue-specific loss of either caspase-8 or cFLIP in the myeloid compartment (caspase-8LC; cFLIPLC) caused impaired macrophage maturation44-46 and excess granulocytosis in cFLIPLC mice.45 Moreover, cytokines associated with myeloid differentiation, such as G-CSF, GM-CSF, and M-CSF, were elevated in the cFLIPLC mice45 similar to the c1LCc2−/−X−/− mice. Although excess levels of cytokines and chemokines, such as G-CSF, GM-CSF, M-CSF, or TNF, were not reported in the studies of caspase-8LC mice, treatment with the pan-caspase inhibitor zVAD-fmk caused excess TNF production in L929 cells and subsequent cell death,27 suggesting that loss or inhibition of caspase-8 can cause production of cytokines in certain cell types. Loss of RIPK3 rescued the ability of caspase-8–deficient myeloid progenitors to differentiate into macrophages,37 and in our experiments, loss of RIPK3 attenuated cytokine production and exacerbated hematopoiesis caused upon Smac mimetic treatment in vivo. Interestingly, a cytosolic complex consisting of caspase-8, FADD, FLIP, and RIPK1 was found in U937 cells driven to differentiate by M-CSF, and in these cells, cleavage of RIPK1 and FLIP by caspase-8 reduced nuclear factor κB signaling.46 Collectively, these and our results suggest that cIAPs and XIAP negatively regulate the formation of the signaling complex that contains caspase-8, FADD, FLIP, RIPK1, and possibly RIPK3. This complex then signals to regulate cytokine/chemokine production in macrophage differentiation. Thus, in X-linked lymphoproliferative syndrome17,47 or where cIAPs are degraded because of extracellular signals,48-50 IAPs regulate cytokine production through a RIPK1/RIPK3-dependent manner.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is an Inside Blood commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the animal staff at LaTrobe University Central Animal House and the WEHI Animal facility, WEHI Flow cytometric facility and histology, M. Kelliher for Ripk1−/− mice, V. Dixit for Ripk3−/− mice, and H. Korner for Tnfr1−/−, Tnfr2−/−, and Tnf−/− mice. The authors acknowledge J. Corbin, L. DiRago, S. Misfud, and A. Lin for technical support and M. D. Robinson for statistical advice. Stephen Condon synthesized compounds used in these experiments.

This work was supported by grants from National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) (433013, 356256, and 461221) (J.S.), NHMRC Australian Fellowships and Leukemia and Lymphoma Society and NHMRC (461221) grants (D.L.V. and A.S.), Swiss National Science Foundation (310030_138085/1) (W.W.-L.W.), NHMRC grant (1051210) (J.E.V. and K.E.L.), an NHMRC Career Development Fellowship (1052598) (J.E.V.), an Australian Research Council Future Fellowship (FT100100100) and NHMRC grant (637342) (J.M.M.), NHMRC Program grant (1016647) and Research Fellowship (575501) (W.S.A.), the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society and an NHMRC project grant (1009145) (L.O.), the Cancer Council Victoria (D.M.), and the Victorian State Government Operational Infrastructure Support and Australian Government NHMRC Institutional Research Interactive Information System (361646).

Authorship

Contribution: W.W.-L.W. designed, conducted, and analyzed experiments and wrote the manuscript; J.E.V., N.L., and K.E.L. conducted and analyzed experiments and cowrote the manuscript; D.C. and A.B. conducted and analyzed experiments; H.A. bred, observed, and maintained the gene-targeted and completely gene-deficient mice; D.M. contributed to the design of experiments and analyzed data; P.J.J. and L.O. conducted experiments; J.M.M. and W.S.A. bred and characterized the Mlkl−/− mice; A.S. and D.L.V. contributed to the design of experiments and cowrote the manuscript; and J.S. contributed to the design of experiments, analyzed experiments, and cowrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: J.S. and D.L.V. are on the Scientific Advisory Board of TetraLogic Pharmaceuticals. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation for W.W.-L.W. is Institute of Experimental Immunology, University of Zurich, Zurich 8057, Switzerland.

The current affiliation for P.J.J. is III. Medizinische Klinik, Klinikum rechts der Isar, Technische Universität München, 81675 Munich, Germany.

Correspondence: John Silke, Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research, 1G Royal Parade, VIC 3052, Australia; e-mail: silke@wehi.edu.au; and W. Wei-Lynn Wong, Institute of Experimental Immunology, University of Zurich, Winterthurerstrasse 190, Zurich 8057, Switzerland; e-mail: wong@immunology.uzh.ch.

References

Author notes

J.E.V., N.L., and K.E.L. contributed equally to this study.

D.C., A.B., and H.A. contributed equally to this study.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal