To the editor:

Most B-cell malignancies are dependent upon signaling by the B-cell receptor (BCR) and other growth and survival signals provided by the tumor microenvironment. Two recently US Food and Drug Administration–approved drugs that target the BCR signalosome, the Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor ibrutinib, and the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase δ (PI3Kδ) inhibitor idelalisib, show unprecedented clinical activity, in particular in mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).1-5 In these malignancies, both drugs result in a rapid and sustained reduction of lymphadenopathy, which is unexpectedly accompanied by transient lymphocytosis.1,4,6-8 We have previously demonstrated that ibrutinib targets BCR- and chemokine-controlled integrin-mediated adhesion (retention) and migration (homing) of the malignant cells in their growth- and survival-supporting lymphoid organ microenvironment, resulting in their mobilization from these protective niches into the circulation; this deprives the malignant cells of critical growth and survival factors, resulting in CLL and MCL regression.6-8

Unfortunately, approximately 30% of MCL and CLL patients show primary resistance against ibrutinib.1,2 Furthermore, a subset of patients that do respond and receive prolonged treatment with ibrutinib relapse1,2 because of recurrent mutations of BTK and its substrate phospholipase Cγ2 (PLCγ2).9 Combination therapy may be more effective and prevent or overcome this therapy resistance. Because targeting BCR-controlled integrin-mediated adhesion is of major relevance for the clinical efficacy of ibrutinib,6-8 and because BTK and PI3K differentially regulate BCR signaling,8 we investigated the effect of idelalisib, either alone or in combination with ibrutinib, on this pathway.

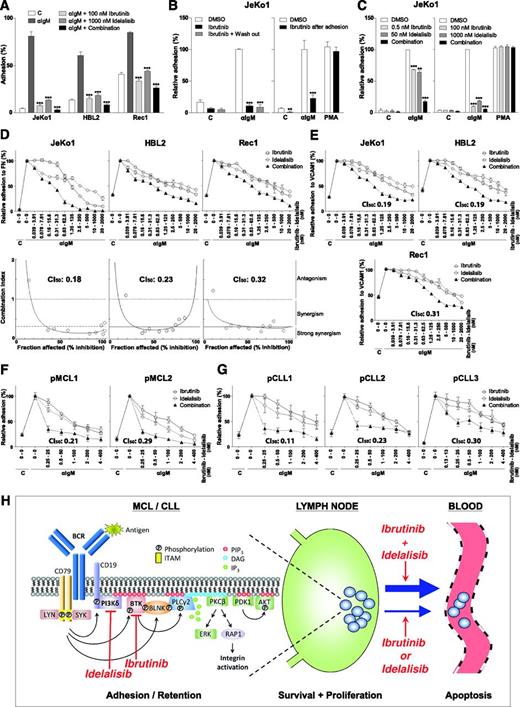

In the MCL cell lines JeKo1, HBL2, and Rec1, BCR stimulation strongly induced integrin-mediated adhesion to fibronectin, which was severely impaired upon treatment with selective and clinically relevant concentrations of ibrutinib (100 nM) and idelalisib (1 µM) (Figure 1A). The BTK dependence and specificity of the ibrutinib effect is strongly supported by wash-out experiments that exploit the irreversible interaction between ibrutinib and BTK (Figure 1B). Furthermore, BCR-controlled adhesion was not only prevented, but also reversed by ibrutinib (Figure 1B); this is of major importance because cell detachment underlies/precedes the clinically observed egress of the malignant cells from lymphoid organs (lymphocytosis). Interestingly, the combination of ibrutinib and idelalisib displayed stronger inhibition of adhesion compared with either drug alone (Figure 1A), which became more evident at suboptimal concentrations of ibrutinib (0.5 nM) and idelalisib (50 nM) (Figure 1C).

Ibrutinib and idelalisib inhibit BCR-controlled integrin-mediated adhesion of MCL and CLL cells in a strongly synergistic manner. (A) JeKo1, HBL2, and Rec1 cells, pretreated with 100 nM ibrutinib and/or 1 µM idelalisib for 1 hour, were stimulated with α immunoglobulin M (αIgM) and allowed to adhere to fibronectin-coated surfaces for 30 minutes. Nonadherent cells were removed by extensive washing, and adherent cells were quantified. (B) Left panel: JeKo1 cells, pretreated for 1 hour with 100 nM ibrutinib, were washed to remove unbound ibrutinib, stimulated with αIgM, and allowed to adhere to fibronectin-coated surfaces. Right panel: JeKo1 cells were stimulated with αIgM and allowed to adhere to fibronectin-coated surfaces. After 30 minutes, cells were treated with 100 nM ibrutinib for 2 hours. DMSO, dimethylsulfoxide. (C) Left panel: JeKo1 cells, pretreated with suboptimal concentrations of ibrutinib (0.5 nM) and/or idelalisib (50 nM), were stimulated with αIgM and allowed to adhere to fibronectin-coated surfaces (n = 3 independent experiments). Right panel: JeKo1 cells, pretreated with 100 nM ibrutinib and/or 1 µM idelalisib, were stimulated with αIgM or PMA and allowed to adhere to fibronectin-coated surfaces (n = 3 independent experiments). (D,E) JeKo1, HBL2, and Rec1 cells, pretreated with different concentrations of ibrutinib and/or idelalisib were stimulated with αIgM and allowed to adhere to fibronectin (FN)-coated (D) or vascular cell adhesion molecule-1(VCAM1)–coated (E) surfaces. Upper panel: adhesion plots. Lower panel: FaCI (Chou-Talalay) plots. (F,G) Primary MCL cells (F) and CLL cells (G), pretreated with different concentrations of ibrutinib and/or idelalisib, were stimulated with αIgM and allowed to adhere to fibronectin-coated surfaces. All graphs are presented as normalized means ± standard error of the mean (100% = stimulated cells without inhibitors). C, control (absence of stimulus); CI50, combination index at 50% inhibition/inhibitory concentration. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001, significantly different from DMSO controls (1-way analysis of variance followed by Dunnett t test). Details regarding materials, MCL cell lines, primary MCL and CLL cell isolation, adhesion assays, and synergy calculations are described in the supplemental Methods section on the Blood Web site. Approval was obtained from the Academic Medical Center Institutional Review Board for these studies, and informed consent was provided according to the Declaration of Helsinki. (H) Ibrutinib and idelalisib synergistically target BCR-controlled integrin-mediated retention of MCL and CLL cells in lymphoid organs. (Left panel) Antigen-stimulated BCR signaling activates PI3Kδ, which produces PIP3, resulting in the membrane recruitment of BTK, PLCγ2, and PDK1/AKT through their PH domains. LYN/SYK-mediated phosphorylation of the adaptor protein BLNK brings BTK and PLCγ2 in close proximity of each other. BTK is activated by LYN/SYK-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation, and subsequently BTK phosphorylates and activates PLCγ2. PLCγ2 produces DAG, a recruitment signal for PKC, and inositol-1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3), which causes the release of calcium from intracellular stores, resulting in PKC activation. PKC activates the RAS/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) pathway and RAP1, a switch for integrin activation. Targeting of PI3Kδ by idelalisib inhibits membrane recruitment of BTK, PLCγ2, and PDK1/AKT, and targeting of BTK by ibrutinib inhibits activation of PLCγ2. Furthermore, ibrutinib and idelalisib both inhibit BCR-controlled integrin-mediated adhesion. Moreover, the combination of ibrutinib and idelalisib results in strongly synergistic inhibition of integrin-mediated adhesion. The point of synergy between ibrutinib and idelalisib appears to lie upstream of PKC, because neither ibrutinib nor idelalisib alone nor their combination affects PMA-controlled adhesion (see panel C). Indeed, ibrutinib inhibits BTK activity, but ibrutinib-bound BTK can still bind (and block) PIP3, the product of PI3K, and idelalisib inhibits PIP3 formation, which is required for translocation and activation of BTK and its substrate PLCγ2. (Right panel) Ibrutinib and idelalisib overcome retention of MCL and CLL cells in their growth- and survival-supporting lymph node and bone marrow microenvironment, resulting in their egress from these protective niches into the circulation (lymphocytosis) and in lymphoma regression. The strongly synergistic targeting of BCR-controlled adhesion, which will result in more efficient mobilization of MCL and CLL cells, provides a strong rationale for clinical studies on combination therapy with ibrutinib and idelalisib, both from the perspective of therapy efficacy as well as drug resistance (see text for further details). DAG, diacylglycerol; ITAM, immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif. Adapted with permission from de Rooij et al6 and Spaargaren et al.8

Ibrutinib and idelalisib inhibit BCR-controlled integrin-mediated adhesion of MCL and CLL cells in a strongly synergistic manner. (A) JeKo1, HBL2, and Rec1 cells, pretreated with 100 nM ibrutinib and/or 1 µM idelalisib for 1 hour, were stimulated with α immunoglobulin M (αIgM) and allowed to adhere to fibronectin-coated surfaces for 30 minutes. Nonadherent cells were removed by extensive washing, and adherent cells were quantified. (B) Left panel: JeKo1 cells, pretreated for 1 hour with 100 nM ibrutinib, were washed to remove unbound ibrutinib, stimulated with αIgM, and allowed to adhere to fibronectin-coated surfaces. Right panel: JeKo1 cells were stimulated with αIgM and allowed to adhere to fibronectin-coated surfaces. After 30 minutes, cells were treated with 100 nM ibrutinib for 2 hours. DMSO, dimethylsulfoxide. (C) Left panel: JeKo1 cells, pretreated with suboptimal concentrations of ibrutinib (0.5 nM) and/or idelalisib (50 nM), were stimulated with αIgM and allowed to adhere to fibronectin-coated surfaces (n = 3 independent experiments). Right panel: JeKo1 cells, pretreated with 100 nM ibrutinib and/or 1 µM idelalisib, were stimulated with αIgM or PMA and allowed to adhere to fibronectin-coated surfaces (n = 3 independent experiments). (D,E) JeKo1, HBL2, and Rec1 cells, pretreated with different concentrations of ibrutinib and/or idelalisib were stimulated with αIgM and allowed to adhere to fibronectin (FN)-coated (D) or vascular cell adhesion molecule-1(VCAM1)–coated (E) surfaces. Upper panel: adhesion plots. Lower panel: FaCI (Chou-Talalay) plots. (F,G) Primary MCL cells (F) and CLL cells (G), pretreated with different concentrations of ibrutinib and/or idelalisib, were stimulated with αIgM and allowed to adhere to fibronectin-coated surfaces. All graphs are presented as normalized means ± standard error of the mean (100% = stimulated cells without inhibitors). C, control (absence of stimulus); CI50, combination index at 50% inhibition/inhibitory concentration. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001, significantly different from DMSO controls (1-way analysis of variance followed by Dunnett t test). Details regarding materials, MCL cell lines, primary MCL and CLL cell isolation, adhesion assays, and synergy calculations are described in the supplemental Methods section on the Blood Web site. Approval was obtained from the Academic Medical Center Institutional Review Board for these studies, and informed consent was provided according to the Declaration of Helsinki. (H) Ibrutinib and idelalisib synergistically target BCR-controlled integrin-mediated retention of MCL and CLL cells in lymphoid organs. (Left panel) Antigen-stimulated BCR signaling activates PI3Kδ, which produces PIP3, resulting in the membrane recruitment of BTK, PLCγ2, and PDK1/AKT through their PH domains. LYN/SYK-mediated phosphorylation of the adaptor protein BLNK brings BTK and PLCγ2 in close proximity of each other. BTK is activated by LYN/SYK-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation, and subsequently BTK phosphorylates and activates PLCγ2. PLCγ2 produces DAG, a recruitment signal for PKC, and inositol-1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3), which causes the release of calcium from intracellular stores, resulting in PKC activation. PKC activates the RAS/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) pathway and RAP1, a switch for integrin activation. Targeting of PI3Kδ by idelalisib inhibits membrane recruitment of BTK, PLCγ2, and PDK1/AKT, and targeting of BTK by ibrutinib inhibits activation of PLCγ2. Furthermore, ibrutinib and idelalisib both inhibit BCR-controlled integrin-mediated adhesion. Moreover, the combination of ibrutinib and idelalisib results in strongly synergistic inhibition of integrin-mediated adhesion. The point of synergy between ibrutinib and idelalisib appears to lie upstream of PKC, because neither ibrutinib nor idelalisib alone nor their combination affects PMA-controlled adhesion (see panel C). Indeed, ibrutinib inhibits BTK activity, but ibrutinib-bound BTK can still bind (and block) PIP3, the product of PI3K, and idelalisib inhibits PIP3 formation, which is required for translocation and activation of BTK and its substrate PLCγ2. (Right panel) Ibrutinib and idelalisib overcome retention of MCL and CLL cells in their growth- and survival-supporting lymph node and bone marrow microenvironment, resulting in their egress from these protective niches into the circulation (lymphocytosis) and in lymphoma regression. The strongly synergistic targeting of BCR-controlled adhesion, which will result in more efficient mobilization of MCL and CLL cells, provides a strong rationale for clinical studies on combination therapy with ibrutinib and idelalisib, both from the perspective of therapy efficacy as well as drug resistance (see text for further details). DAG, diacylglycerol; ITAM, immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif. Adapted with permission from de Rooij et al6 and Spaargaren et al.8

To establish if the combination of ibrutinib and idelalisib is synergistic, we employed the quantitative combination index (CI) theorem of Chou-Talalay (CI <1.0 = synergy; <0.3 strong synergy). The concentration range was centered around the determined 50% inhibition/inhibitory concentration of ibrutinib (∼1 nM) and idelalisib (∼100 nM), using the corresponding constant molar ratio (1:100). Ibrutinib and idelalisib inhibited BCR-controlled adhesion of all 3 MCL cell lines to fibronectin and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 in a strongly synergistic manner, with CI50 values typically below 0.3 (Figure 1D-E). This effect is specific for proximal BCR signaling because stimulation of integrin-mediated adhesion with the protein kinase C (PKC) activator phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), which circumvents BTK and PI3Kδ activation, was not affected (Figure 1C). Moreover, also in primary MCL and CLL, ibrutinib and idelalisib inhibit BCR-stimulated integrin-mediated adhesion in a strongly synergistic manner (Figure 1F-G).

Apparently, because ibrutinib and idelalisib target BCR signaling by different means, they enforce each other’s effect. Consequently, combination therapy is expected to result in a more prominent mobilization of malignant MCL and CLL cells from their growth and survival promoting niches (Figure 1H). From the perspective of drug clearance and protein turnover, the effect may also be stronger and prolonged because BTK and PI3Kδ do not have to be fully occupied when the combination is used. Furthermore, lower doses can be given, which might be beneficial for the efficacy/toxicity ratio. Of major importance, however, targeting more than 1 key component of a pathway may overcome innate and overcome or prevent acquired (mono)therapy resistance. For example, ibrutinib may still be beneficial in (relapsed) MCL patients that aberrantly express the PI3Kδ-redundant PI3Kα,10 and idelalisib may still be beneficial in the ibrutinib-treated patients that relapse from mutations in BTK and/or PLCγ2,9 because phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-triphosphate (PIP3) association is required for both BTK and PLCγ2 activity. Moreover, if applied simultaneously, to develop therapy resistance by the previously mentioned mechanisms, a cell would have to contain or concurrently acquire 2 independent mutations: a highly unlikely event.

Taken together, from the perspective of therapeutic efficacy and drug resistance, our preclinical observations provide a rationale for (sequential or) combination therapy with ibrutinib and idelalisib in the treatment of MCL and CLL, but also of other B-cell malignancies that depend upon active BCR signaling and/or the tumor microenvironment.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

Authorship

Acknowledgments. The authors thank Eric Eldering and Rachel Thijssen for providing CLL patient samples. This study was supported by a grant from the Dutch Cancer Society (KWF).

Contribution: M.F.M.d.R. designed the research, performed experiments, analyzed the data, designed the figure, and wrote the manuscript; A.K. performed experiments; A.P.K. and M.J.K. provided patient material and reviewed the manuscript; S.T.P. cosupervised the study and reviewed the manuscript; and M.S. designed the research, supervised the study, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: M.S. has previously received research support from Pharmacyclics Inc. and Johnson & Johnson. M.J.K. has previously received honoraria from Janssen Pharmaceuticals. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interest.

Correspondence: Marcel Spaargaren, Department of Pathology, Academic Medical Center, University of Amsterdam, Meibergdreef 9, 1105 AZ Amsterdam, The Netherlands; e-mail: marcel.spaargaren@amc.uva.nl.

References

Author notes

S.T.P. and M.S. contributed equally to this study.