Key Points

Identification and prospective isolation of EEP and LEP from human bone marrow (BM) facilitates the study of erythropoiesis.

Quantitative and qualitative defects in EP underpinning erythropoietic failure in DBA are restored in steroid-responsive (SR) patients.

Abstract

Diamond-Blackfan anemia (DBA) is a disorder characterized by a selective defect in erythropoiesis. Delineation of the precise defect is hampered by a lack of markers that define cells giving rise to erythroid burst- and erythroid colony-forming unit (BFU-E and CFU-E) colonies, the clonogenic assays that quantify early and late erythroid progenitor (EEP and LEP) potential, respectively. By combining flow cytometry, cell-sorting, and single-cell clonogenic assays, we identified Lin−CD34+CD38+CD45RA−CD123−CD71+CD41a−CD105−CD36− bone marrow cells as EEP giving rise to BFU-E, and Lin−CD34+/−CD38+CD45RA−CD123−CD71+CD41a−CD105+CD36+ cells as LEP giving rise to CFU-E, in a hierarchical fashion. We then applied these definitions to DBA and identified that, compared with controls, frequency, and clonogenicity of DBA, EEP and LEP are significantly decreased in transfusion-dependent but restored in corticosteroid-responsive patients. Thus, both quantitative and qualitative defects in erythroid progenitor (EP) contribute to defective erythropoiesis in DBA. Prospective isolation of defined EPs will facilitate more incisive study of normal and aberrant erythropoiesis.

Introduction

Diamond-Blackfan anemia (DBA) is a rare inherited bone marrow (BM) failure syndrome caused by monoallelic mutations in ribosomal protein genes.1-3 Normochromic, macrocytic anemia, and reticulocytopenia, the hematologic hallmarks of DBA, stem from a selective paucity of erythroid precursors in the BM.4

Animal models of DBA and in vitro studies of human unfractionated BM or total CD34+ cells have suggested that red cell aplasia in DBA arises from a defect in erythroid progenitors (EPs).5,6 This defect has been defined functionally by a reduced ability of DBA BM to generate erythroid burst-forming unit (BFU-E) and erythroid colony-forming unit (CFU-E) colonies.7,8 Since DBA EP have also been reported to have qualitative abnormalities, such as relative erythropoietin insensitivity,9,10 elucidation of the relative roles of these qualitative and quantitative defects in DBA erythropoiesis and determination of the mechanism of steroid responsiveness in 40% patients,4 require knowledge of the markers that define the BM cells giving rise to CFU-E and BFU-E.

Although in mice the immunophenotypes of such cells have been described in fetal liver,11,12 facilitating important insights into erythropoiesis,12,13 in humans, definitions of corresponding EPs are limited, thus precluding their direct study in normal and aberrant erythropoiesis.

In this study, we sought to dissect the erythropoietic defect in DBA by prospective isolation and characterization of human EP.

Study design

BM samples

BM samples were obtained from patients with DBA and healthy BM donors (see supplemental Table 1, available on the Blood Web site) under approval by the National Research Ethics Service, following written informed consent. Ribosomal protein gene mutations were identified as previously described.1

Methods

Flow cytometry, cell sorting, clonogenic assays, liquid cultures, and quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) are described in supplemental Materials and methods. Antibodies and TaqMan quantitative PCR probes are listed in supplemental Tables 2 and 3.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics show mean ± SEM. The unpaired Student t test or Mann-Whitney U test were used as appropriate (GraphPad Prism, version 6).

Results and discussion

Established models of human hematopoiesis suggest that common myeloid progenitors (CMPs) generate granulocyte-monocyte progenitors (GMPs) and megakaryocyte-EPs (MEPs) (Lin−CD34+CD38+CD45RA−CD123− cells).14 The latter overlap with a CD45RA−CD123− population enriched in committed EPs.8,15,16 To study the erythropoietic defect in DBA, we examined the frequency and function of CMP, MEP, and GMP in BM. In transfusion-dependent (TD) DBA patients, these progenitor frequencies were similar to age-matched controls (supplemental Figure 1A). However, DBA MEP gave rise to significantly fewer BFU-E and CFU-E (P < .05) and generated small, poorly hemoglobinized erythroid cell clusters, which failed to develop into fully formed BFU-E (Figure 1A).

Prospective isolation of human BM populations highly enriched in BFU-E and CFU-E activity. (A) Left: Clonogenic capacity of flow-sorted CMP, MEP, and GMP from purified, BM-derived CD34+ cells from TD DBA patients (n = 5) and age-matched controls (CON, n = 4). Right: Abnormal erythroid colonies, which we termed erythroid clusters, are observed exclusively in DBA cultures. (B) EP populations arising downstream of MEP (defined by flow cytometry as Lin−CD34+CD38+CD45RA−CD123−) were characterized by their expression of CD71, CD41a, CD36, and CD105. (C) CD71+CD41a−CD105−CD36− (n = 6) and CD71+CD41a−CD105+CD36+ (n = 5) subpopulations were sorted into complete methylcellulose containing cytokines supportive of erythroid and myeloid development. GMPs were sorted concurrently as a control. Hematopoietic colonies were identified and scored as described in supplemental Materials and methods. (D) Single-cell clonogenic assays of Lin−CD34+CD38+CD45RA−CD123−CD71+CD41a−CD105−CD36− cells (EEP; n = 5) and Lin−CD34+CD38+CD45RA−CD123−CD71+CD41a−CD105+CD36+ cells (LEP; n = 3). The percentage single-cell clonogenicity is defined as % of wells in which a colony grew following flow sorting of 1 cell per well. (E) May-Grünwald Giemsa staining of flow-sorted EEP and LEP from control adult BM. (F) Proliferative capacity of flow-sorted EEP and LEP in a longitudinal liquid culture (Protocol B; supplemental Materials and methods) assessed by cell counting (n = 4). Cells on day 11 were erythroblasts (ie, CD34−CD71+GlyA+CD14−CD11b−CD41a−). (G) Concurrent cell-cycle analysis on day 11 shows a higher number of erythroblasts derived from EEP in S phase with fewer in G0/1 compared with erythroblasts derived from LEP (P < .05). (H) Flow-sorted EEP and LEP derived from control adult BM were cultured in the presence of erythropoietin, IL-3, IL-6, and stem cell factor (Protocol A; supplemental Materials and methods). Three days later, flow-cytometric analysis showed that EEP acquired expression of CD105 and CD36, whereas LEP gained higher expression of CD105 and CD36 (blue dots = day 0; green dots = day 3). Plots shown are representative of 2 independent experiments. (I) Messenger RNA expression levels of CD36, GATA-1, and GATA-2 determined by quantitative real-time PCR in purified GMP, MEP, EEP, LEP, and erythroblasts (Lin−CD34−CD36hiCD71+GlyA+ erythroblasts [EB]), derived from 3 control BM samples. Transcript levels are normalized to GAPDH and expressed relative to the corresponding gene expression in MEP. As expected, GMPs do not express CD36 and GATA-1 but express a low level of GATA-2. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. *P < .05. CON, controls; NS, not significant.

Prospective isolation of human BM populations highly enriched in BFU-E and CFU-E activity. (A) Left: Clonogenic capacity of flow-sorted CMP, MEP, and GMP from purified, BM-derived CD34+ cells from TD DBA patients (n = 5) and age-matched controls (CON, n = 4). Right: Abnormal erythroid colonies, which we termed erythroid clusters, are observed exclusively in DBA cultures. (B) EP populations arising downstream of MEP (defined by flow cytometry as Lin−CD34+CD38+CD45RA−CD123−) were characterized by their expression of CD71, CD41a, CD36, and CD105. (C) CD71+CD41a−CD105−CD36− (n = 6) and CD71+CD41a−CD105+CD36+ (n = 5) subpopulations were sorted into complete methylcellulose containing cytokines supportive of erythroid and myeloid development. GMPs were sorted concurrently as a control. Hematopoietic colonies were identified and scored as described in supplemental Materials and methods. (D) Single-cell clonogenic assays of Lin−CD34+CD38+CD45RA−CD123−CD71+CD41a−CD105−CD36− cells (EEP; n = 5) and Lin−CD34+CD38+CD45RA−CD123−CD71+CD41a−CD105+CD36+ cells (LEP; n = 3). The percentage single-cell clonogenicity is defined as % of wells in which a colony grew following flow sorting of 1 cell per well. (E) May-Grünwald Giemsa staining of flow-sorted EEP and LEP from control adult BM. (F) Proliferative capacity of flow-sorted EEP and LEP in a longitudinal liquid culture (Protocol B; supplemental Materials and methods) assessed by cell counting (n = 4). Cells on day 11 were erythroblasts (ie, CD34−CD71+GlyA+CD14−CD11b−CD41a−). (G) Concurrent cell-cycle analysis on day 11 shows a higher number of erythroblasts derived from EEP in S phase with fewer in G0/1 compared with erythroblasts derived from LEP (P < .05). (H) Flow-sorted EEP and LEP derived from control adult BM were cultured in the presence of erythropoietin, IL-3, IL-6, and stem cell factor (Protocol A; supplemental Materials and methods). Three days later, flow-cytometric analysis showed that EEP acquired expression of CD105 and CD36, whereas LEP gained higher expression of CD105 and CD36 (blue dots = day 0; green dots = day 3). Plots shown are representative of 2 independent experiments. (I) Messenger RNA expression levels of CD36, GATA-1, and GATA-2 determined by quantitative real-time PCR in purified GMP, MEP, EEP, LEP, and erythroblasts (Lin−CD34−CD36hiCD71+GlyA+ erythroblasts [EB]), derived from 3 control BM samples. Transcript levels are normalized to GAPDH and expressed relative to the corresponding gene expression in MEP. As expected, GMPs do not express CD36 and GATA-1 but express a low level of GATA-2. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. *P < .05. CON, controls; NS, not significant.

Next, we aimed to purify normal BM EP populations using a novel gating strategy. Specifically, we aimed to define surface markers relevant to murine and/or human erythropoiesis11,17-19 on the CD123−CD45RA− fraction of Lin−CD34+CD38+ BM cells (Figure 1B). Sorting into methylcellulose medium revealed that both CD105−CD36− and CD105+CD36+ subpopulations of CD71+CD41a− MEP (both of which, as recently described for CD34+ cord blood-derived BFU-E/ CFU-E,20 express CD45; supplemental Figure 1B), generated erythroid but not myeloid colonies (Figure 1C). Moreover, CD105−CD36− cells generated almost exclusively large and small BFU-E (Figure 1C and supplemental Figure 1C) with a purity of 96% and clonogenicity of 66.8% in single-cell assays (Figure 1D). We termed this early EP (EEP). In contrast, CD105+CD36+ cells, termed late EP (LEP), generated CFU-E but not BFU-E colonies with a purity of 97% and clonogenicity of 72.3% (Figure 1C-D). Notably, the frequencies of BFU-E and CFU-E derived from EEP and LEP (corrected for their clonogenicity at a single-cell level) were similar to BFU-E and CFU-E frequencies derived from age-matched, total BM-derived CD34+ cells (supplemental Figure 1D-E), suggesting that our sorting strategy captures the majority of EP activity in CD34+ cells. Further, consistent with previous work,21,22 CFU-E activity in flow-sorted populations showed a fourfold enrichment in CD34+CD71+CD41a−CD105+CD36+ vs CD34−CD71+CD41a−CD105+CD36+ cells (supplemental Figure 1F), suggesting that CFU-E activity is contained in both CD34+ and CD34− fractions.

Consistent with EEP and LEP being distinct progenitor populations, we found that ex vivo sorted EEP are small and blast-like with a higher nuclear-cytoplasmic ratio than the larger LEP (Figure 1E), similar to murine fetal EP.11 Furthermore, under liquid culture conditions, EEP had a higher proliferative capacity than LEP (P < .05; Figure 1F) and a higher fraction of erythroid precursors, ie, erythroblasts derived from EEP were in S phase (P < .05; Figure 1G) consistent with LEP arising downstream of EEP in the erythropoietic hierarchy. Whereas flow-purified EEP generated LEP in short-term liquid cultures, LEP were unable to generate EEP (Figure 1H). Additionally, although both populations generated purely erythroblasts (ie, CD34−CD71+GlyA+CD14−CD11b−CD41a−), LEP differentiated more rapidly as shown by a higher fraction of GlyA+ (glycophorin A) cells lacking CD10519 on day 11 (supplemental Figure 1G). Finally, these populations exhibited distinct gene expression patterns: (1) in line with their immunophenotypes (Figure 1B) expression of CD36 progressively increased from EEP to erythroblasts, and (2) consistent with findings in murine23 and human20 EP, expression of the megakaryocyte-erythroid transcription factor GATA-124 increased from EEP to erythroblasts, whereas GATA-2 was downregulated at the LEP stage (Figure 1I).

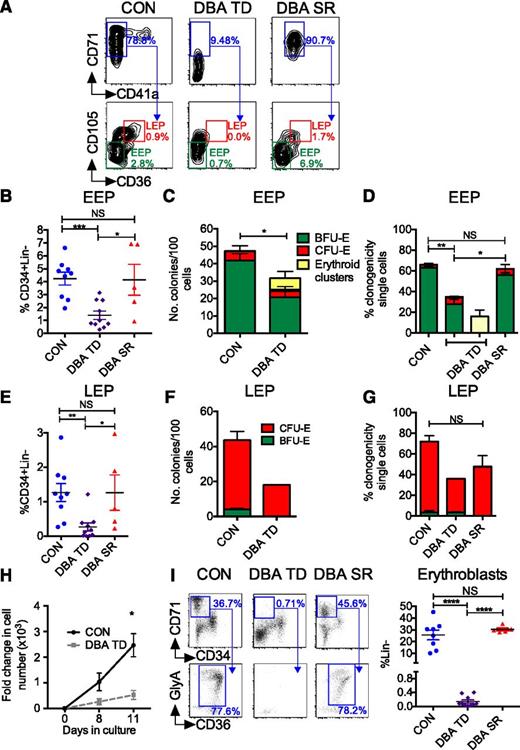

Next, we sought to elucidate the EP defect in DBA BM using our novel EP definitions. The frequency of EEP was reduced in TD DBA BM (P < .001; Figure 2A-B), which was mainly attributable to the decreased frequency of CD71+CD41a− cells (Figure 2A). In clonogenic assays, TD DBA EEP generated fewer colonies than controls (P < .05; Figure 2C), consistent with quantitative and qualitative defects in DBA EEP, which were even more pronounced when EEP frequency and their clonogenic output were considered together (supplemental Figure 2A). Single-cell assays confirmed the reduced clonogenicity of TD DBA EEP (P < .01; Figure 2D) and revealed heterogeneity within EEP in individual patients; whereas some EEP formed BFU-E of normal size and morphology, others produced abnormal, poorly hemoglobinized erythroid clusters (supplemental Figure 2B). Similar abnormalities were found in the frequency and clonogenicity of DBA LEP (Figure 2E-G). Consistent with these findings, DBA EEP generated fewer erythroblasts than controls in an erythroid liquid culture system (P < .05; Figure 2H). Notably, in steroid-responsive (SR) patients (supplemental Table 1), both frequency and clonogenicity of EEP were significantly higher than in TD patients (Figure 2A-B,D). Similarly, LEP frequency was higher in SR than in TD patients, although the impact on LEP clonogenicity was variable (Figure 2E,G).

Specific EEP and LEP defects in DBA. (A) EEP and LEP were quantified by flow cytometry. Representative plots from a patient with TD DBA, SR DBA, and an age-matched control are shown. Values refer to frequency of CD71+CD41a− cells as a % of MEP, and frequency of EEP and LEP as a % of CD34+Lin− population. (B) Frequency of BM EEP in TD DBA (n = 10), SR DBA (n = 5), and control BM (n = 9) as assessed by flow cytometry. (C) Frequency of BFU-E colonies generated from 100 flow-sorted DBA and control EEP (n = 4). (D) Clonogenicity of TD DBA (n = 4), SR DBA (n = 3), and control EEP (n = 6) flow-sorted as single cells. (E) Frequency of LEP in TD DBA (n = 10), SR DBA (n = 5), and control BM (n = 9) as assessed by flow cytometry. (F) Clonogenicity of DBA TD (n = 2; due to insufficient LEPs in TD DBA BM for sorting) and control (n = 4) LEP after sorting and plating of 100 cells. (G) Clonogenicity of TD DBA (n = 2), SR DBA (n = 3), and control LEP (n = 5) flow-sorted as single cells. (H) Proliferative capacity of flow-sorted DBA and control EEP in a longitudinal liquid culture (Protocol B; supplemental Materials and methods) assessed by cell counting (n = 4). Cells on day 11 were a pure population of erythroblasts (ie, CD34−CD71+GlyA+CD14−CD11b−CD41a−). (I) Left: BM erythroblasts arising downstream of EPs were identified as Lin− (not shown) CD34−CD71+ BM mononuclear cells (top panel) co-expressing CD36 and GlyA (bottom panel). Representative flow cytometry plots from a control, a TD patient with DBA, and a DBA patient successfully treated with steroids are shown. Right: Cumulative data from controls (n = 8), TD (n = 10), and steroid-treated (n = 5) DBA patients. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001; ****P < .0001.

Specific EEP and LEP defects in DBA. (A) EEP and LEP were quantified by flow cytometry. Representative plots from a patient with TD DBA, SR DBA, and an age-matched control are shown. Values refer to frequency of CD71+CD41a− cells as a % of MEP, and frequency of EEP and LEP as a % of CD34+Lin− population. (B) Frequency of BM EEP in TD DBA (n = 10), SR DBA (n = 5), and control BM (n = 9) as assessed by flow cytometry. (C) Frequency of BFU-E colonies generated from 100 flow-sorted DBA and control EEP (n = 4). (D) Clonogenicity of TD DBA (n = 4), SR DBA (n = 3), and control EEP (n = 6) flow-sorted as single cells. (E) Frequency of LEP in TD DBA (n = 10), SR DBA (n = 5), and control BM (n = 9) as assessed by flow cytometry. (F) Clonogenicity of DBA TD (n = 2; due to insufficient LEPs in TD DBA BM for sorting) and control (n = 4) LEP after sorting and plating of 100 cells. (G) Clonogenicity of TD DBA (n = 2), SR DBA (n = 3), and control LEP (n = 5) flow-sorted as single cells. (H) Proliferative capacity of flow-sorted DBA and control EEP in a longitudinal liquid culture (Protocol B; supplemental Materials and methods) assessed by cell counting (n = 4). Cells on day 11 were a pure population of erythroblasts (ie, CD34−CD71+GlyA+CD14−CD11b−CD41a−). (I) Left: BM erythroblasts arising downstream of EPs were identified as Lin− (not shown) CD34−CD71+ BM mononuclear cells (top panel) co-expressing CD36 and GlyA (bottom panel). Representative flow cytometry plots from a control, a TD patient with DBA, and a DBA patient successfully treated with steroids are shown. Right: Cumulative data from controls (n = 8), TD (n = 10), and steroid-treated (n = 5) DBA patients. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001; ****P < .0001.

To investigate whether the reduced frequency of EEP and LEP in TD DBA is associated with a reduced frequency of erythroblasts in vivo, we examined this population in fresh BM samples from the same patients studied above. To define erythroblasts, we sorted BM cells into five Lin− populations (supplemental Figure 2C). Consistent with previous immunophenotypic descriptions of erythroblasts,18 Lin−CD34−CD36hiCD71+GlyA−/+ cells (population 3) had negligible colony-forming capacity (supplemental Figure 2C-D) and comprised proerythroblasts to normoblasts with occasional reticulocytes (supplemental Figure 2E). Compared with controls, population 3 was virtually absent in TD DBA (Figure 2I) but rescued in SR patients. Taken together, these data demonstrate that in DBA, as previously shown in normal erythropoiesis,11,13,25 corticosteroids act predominantly at the level of BFU-E progenitors, in turn increasing downstream EP and precursor frequencies.

In conclusion, we present a novel approach allowing the prospective identification, enumeration, and isolation of human BM EP that give rise directly and selectively to BFU-E (Lin−CD34+CD38+CD45RA−CD123−CD105−CD36− EEP) and CFU-E (Lin−CD34+/−CD38+CD45RA−CD123−CD105+CD36+ LEP). Moreover, using this approach, we demonstrate that in DBA, cumulative defects in the frequency and function of EEP and LEP culminate in a striking paucity of erythroblasts, a defect that is restored in SR patients.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the patients, donors, and their families for generously donating samples. The authors also thank the hematology laboratories, nursing, and medical staff at St. Mary’s and Hammersmith Hospitals for their valuable contributions.

This work was supported by the Imperial College Healthcare National Health Service Trust, the CHAMPS charity, and the National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre at Imperial College London. D.I. is a recipient of a Leukaemia and Lymphoma Research Clinical Research Fellowship.

Authorship

Contribution: D.I., B.P., G.G., A.C., and H.E.F. performed experiments and interpreted data; J.d.l.F., Y.H., and L.C.K. provided BM samples and clinical details; A.K. and I.R. conceived and supervised the work; and A.K., I.R., and D.I. wrote the paper with input from all authors.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Anastasios Karadimitris, Centre for Haematology, Department of Medicine, Imperial College London, Hammersmith Hospital, Du Cane Road, London W12 0NN, United Kingdom; e-mail: a.karadimitris@imperial.ac.uk.

![Figure 1. Prospective isolation of human BM populations highly enriched in BFU-E and CFU-E activity. (A) Left: Clonogenic capacity of flow-sorted CMP, MEP, and GMP from purified, BM-derived CD34+ cells from TD DBA patients (n = 5) and age-matched controls (CON, n = 4). Right: Abnormal erythroid colonies, which we termed erythroid clusters, are observed exclusively in DBA cultures. (B) EP populations arising downstream of MEP (defined by flow cytometry as Lin−CD34+CD38+CD45RA−CD123−) were characterized by their expression of CD71, CD41a, CD36, and CD105. (C) CD71+CD41a−CD105−CD36− (n = 6) and CD71+CD41a−CD105+CD36+ (n = 5) subpopulations were sorted into complete methylcellulose containing cytokines supportive of erythroid and myeloid development. GMPs were sorted concurrently as a control. Hematopoietic colonies were identified and scored as described in supplemental Materials and methods. (D) Single-cell clonogenic assays of Lin−CD34+CD38+CD45RA−CD123−CD71+CD41a−CD105−CD36− cells (EEP; n = 5) and Lin−CD34+CD38+CD45RA−CD123−CD71+CD41a−CD105+CD36+ cells (LEP; n = 3). The percentage single-cell clonogenicity is defined as % of wells in which a colony grew following flow sorting of 1 cell per well. (E) May-Grünwald Giemsa staining of flow-sorted EEP and LEP from control adult BM. (F) Proliferative capacity of flow-sorted EEP and LEP in a longitudinal liquid culture (Protocol B; supplemental Materials and methods) assessed by cell counting (n = 4). Cells on day 11 were erythroblasts (ie, CD34−CD71+GlyA+CD14−CD11b−CD41a−). (G) Concurrent cell-cycle analysis on day 11 shows a higher number of erythroblasts derived from EEP in S phase with fewer in G0/1 compared with erythroblasts derived from LEP (P < .05). (H) Flow-sorted EEP and LEP derived from control adult BM were cultured in the presence of erythropoietin, IL-3, IL-6, and stem cell factor (Protocol A; supplemental Materials and methods). Three days later, flow-cytometric analysis showed that EEP acquired expression of CD105 and CD36, whereas LEP gained higher expression of CD105 and CD36 (blue dots = day 0; green dots = day 3). Plots shown are representative of 2 independent experiments. (I) Messenger RNA expression levels of CD36, GATA-1, and GATA-2 determined by quantitative real-time PCR in purified GMP, MEP, EEP, LEP, and erythroblasts (Lin−CD34−CD36hiCD71+GlyA+ erythroblasts [EB]), derived from 3 control BM samples. Transcript levels are normalized to GAPDH and expressed relative to the corresponding gene expression in MEP. As expected, GMPs do not express CD36 and GATA-1 but express a low level of GATA-2. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. *P < .05. CON, controls; NS, not significant.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/125/16/10.1182_blood-2014-10-608042/4/m_2553f1.jpeg?Expires=1769301753&Signature=dlRR3xS~8f~AjScLmQLGrraxv2GOyTLST1eOxteghAr~QE0ONnq59IDD0yoBG7hIWTDT~ZVPPYOqq~Z5lv~UfRJ3WCtzPhg06HcHxxAC8G-3GMxXD2zOBiJ6ceEThHp87x012zBmtzwN0hbtb~lq-HUvtOymQkCdvPgXwXXaGHuN8pICoLjRiPa-Ak1YNBehoPx1596ous8FvffUXxQFNQQEGTQFO08NTvBX3~1qihyN8gJwVltez6cZhQq8KfOq5JKf9hX5dbbdahKrsPUuZ6xugdqziDANFM49j1ZWELQnASl924eDu0-hTZGpkBboVZPjmeFmYYLZAfh5O5aadw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal