Abstract

Hyperleukocytosis (HL) per se is a laboratory abnormality, commonly defined by a white blood cell count >100 000/µL, caused by leukemic cell proliferation. Not the high blood count itself, but complications such as leukostasis, tumor lysis syndrome, and disseminated intravascular coagulation put the patient at risk and require therapeutic intervention. The risk of complications is higher in acute than in chronic leukemias, and particularly leukostasis occurs more often in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) for several reasons. Only a small proportion of AML patients present with HL, but these patients have a particularly dismal prognosis because of (1) a higher risk of early death resulting from HL complications; and (2) a higher probability of relapse and death in the long run. Whereas initial high blood counts and high lactate dehydrogenase as an indicator for high proliferation are part of prognostic scores guiding risk-adapted consolidation strategies, HL at initial diagnosis must be considered a hematologic emergency and requires rapid action of the admitting physician in order to prevent early death.

Incidence and pathophysiology

In untreated acute myeloid leukemia (AML), ∼5% to 20% of patients present with hyperleukocytosis (HL).1-10 In a patient with HL, underlying diseases other than AML, such as acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and chronic myeloid leukemia, particularly in acceleration or blast crisis, should be considered as differential diagnosis. In addition to classic cytology and flow-cytometric immunophenotyping, the rapid screening for the bcr-abl transcript by fluorescence in situ hybridization or polymerase chain reaction is of importance for diagnostic certainty. Although commonly defined by white blood cell (WBC) counts >100 000/µL, it should be noted that WBC levels below this arbitrary threshold can also cause HL-related complications (Figures 1).11 Retrospective analyses have revealed an association with monocytic AML subtypes (French-American-British classification M4/5; Figure 2),9,12,13 chromosomal MLL rearrangement 11q23,9,14 and the FLT3-ITD mutation,9,15,16 although only some patients with these characteristics actually develop HL. In a cohort of 3510 newly diagnosed AML patients of the Study Alliance Leukemia study group, 357 patients (10%) had WBCs >100 000/µL at initial diagnosis. Our explorative analyses revealed 28% French-American-British M4/5 in HL patients as opposed to 16% in non-HL patients (comparison by χ2 test, P < .001). Further associations were seen regarding higher lactate dehydrogenase (1158 U/L vs 386 U/L; P < .001), FLT3-ITD (45% vs 16%; P < .001), NPM1 (44% vs 24%; P < .001), but no association with MLL-PTD (2% vs 1%; P = 1.0). The median Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status score at initial diagnosis was higher in HL patients, and fewer patients displayed favorable or adverse cytogenetic aberrations (C.R. and G.E., unpublished data).

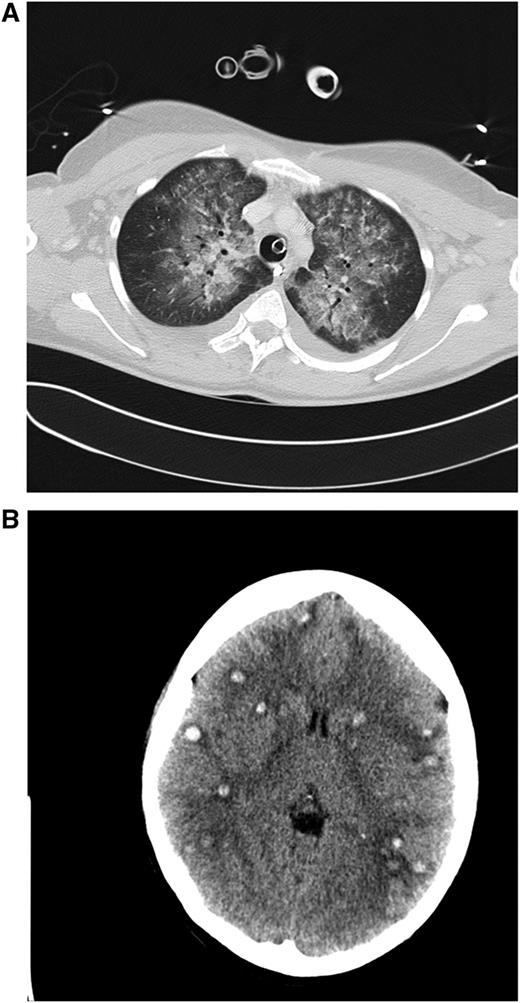

Clinical case 1. A 42-year-old woman presented to her general practitioner with general weakness and tooth pain. Laboratory assessment showed a WBC count of 80 000/µL, hemoglobin of 6.4 mg/dL, and platelet count of 21 000/µL, which led her physician to make an immediate referral to the local hospital, where a differential blood count revealed 56% myeloid blasts. By that time, the patient was in stable clinical condition with a minimally elevated C-reactive protein of 20 mg/L. She was put on 4 g hydroxyurea (HU) and planned for transferal to our hospital the next morning. During the night, she developed dyspnea requiring oxygen supply. We diagnosed an AML M4eo with inv(16) and started induction treatment with cytarabine plus daunorubicin (7 + 3) at a WBC count of 70 000/µL. Immediate leukapheresis was not possible because of the progressive dyspnea and the increasingly deranged coagulation status. By the next day, the WBC count had gone down to 19 000/µL, but the patient developed respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation. The computed tomography (CT) scan result was highly suggestive for leukostasis of the lungs (A), and cranial CT showed multiple focal supratentorial hemorrhages (B). During the next few days, respiratory indices improved, and the patient could be extubated. Early bone marrow response assessment showed a good response with leukemia-free hypoplastic marrow, and after regeneration of peripheral counts, a complete remission (CR) was diagnosed. The patient has currently completed consolidation chemotherapy and is in ongoing CR. The remarkable aspects of this case are (1) the fact that leukostasis developed rapidly even at a WBC count below 100 000/µL, possibly because of the monocytic nature of blasts11 ; (2) cytarabine alone led to a profound and rapid WBC reduction; and (3) the patient recovered from mechanical ventilation because the underlying leukostasis could be treated successfully. (A) Contrast-enhanced CT image (lung window) through the upper fields of the lungs demonstrates parenchymal infiltrates as well as diffuse ground-glass opacities suggestive for leukostasis and myeloblast infiltration. There is sparing of the lung periphery. Note also bilateral pleural effusions. Respiratory failure required mechanical ventilation support as indicated by the endotracheal tube. A central venous catheter in the right brachiocephalic vein and nasogastric tube in the esophagus can be seen. (B) Horizontal plane of native cranial CT scan demonstrating multiple hyperdense lesions in both brain hemispheres indicating hemorrhagic lesions. Accompanying cerebral edema is characterized by loss of gray-white matter differentiation, compression of lateral ventricles, and effacement of sulcal spaces.

Clinical case 1. A 42-year-old woman presented to her general practitioner with general weakness and tooth pain. Laboratory assessment showed a WBC count of 80 000/µL, hemoglobin of 6.4 mg/dL, and platelet count of 21 000/µL, which led her physician to make an immediate referral to the local hospital, where a differential blood count revealed 56% myeloid blasts. By that time, the patient was in stable clinical condition with a minimally elevated C-reactive protein of 20 mg/L. She was put on 4 g hydroxyurea (HU) and planned for transferal to our hospital the next morning. During the night, she developed dyspnea requiring oxygen supply. We diagnosed an AML M4eo with inv(16) and started induction treatment with cytarabine plus daunorubicin (7 + 3) at a WBC count of 70 000/µL. Immediate leukapheresis was not possible because of the progressive dyspnea and the increasingly deranged coagulation status. By the next day, the WBC count had gone down to 19 000/µL, but the patient developed respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation. The computed tomography (CT) scan result was highly suggestive for leukostasis of the lungs (A), and cranial CT showed multiple focal supratentorial hemorrhages (B). During the next few days, respiratory indices improved, and the patient could be extubated. Early bone marrow response assessment showed a good response with leukemia-free hypoplastic marrow, and after regeneration of peripheral counts, a complete remission (CR) was diagnosed. The patient has currently completed consolidation chemotherapy and is in ongoing CR. The remarkable aspects of this case are (1) the fact that leukostasis developed rapidly even at a WBC count below 100 000/µL, possibly because of the monocytic nature of blasts11 ; (2) cytarabine alone led to a profound and rapid WBC reduction; and (3) the patient recovered from mechanical ventilation because the underlying leukostasis could be treated successfully. (A) Contrast-enhanced CT image (lung window) through the upper fields of the lungs demonstrates parenchymal infiltrates as well as diffuse ground-glass opacities suggestive for leukostasis and myeloblast infiltration. There is sparing of the lung periphery. Note also bilateral pleural effusions. Respiratory failure required mechanical ventilation support as indicated by the endotracheal tube. A central venous catheter in the right brachiocephalic vein and nasogastric tube in the esophagus can be seen. (B) Horizontal plane of native cranial CT scan demonstrating multiple hyperdense lesions in both brain hemispheres indicating hemorrhagic lesions. Accompanying cerebral edema is characterized by loss of gray-white matter differentiation, compression of lateral ventricles, and effacement of sulcal spaces.

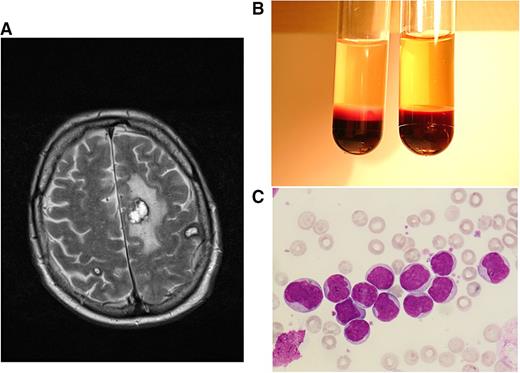

Clinical case 2. A 68-year-old man sought medical help at the emergency unit of his local hospital because of weakness, bone pain, and night sweats over several weeks. He was admitted because of HL of ∼170 000/µL, anemia, and thrombocytopenia. After the diagnosis of AML M4 was made, HU and cytarabine were started, and the patient was transferred to our hospital, presenting with a WBC count 70 000/µL and central neurologic deficits with speech impairment. A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan showed several meningeal lesions, but the cerebrospinal fluid cell count was normal, and infection parameters were negative. In order to avoid cerebrospinal fluid contamination with leukemic blasts, lumbar puncture was postponed until peripheral blast clearance. We continued cytarabine induction and added daunorubicin for 3 days. WBC counts declined rapidly after initiation of cytarabine; the patient’s ability to speak improved gradually, and a control MRI 7 days after admission showed multiple hemorrhagic lesions, most pronounced in the hemispheres, with no signs of extramedullary leukemic lesions or meningeosis (A). In the consecutive aplasia, our patient developed Escherichia coli septicemia and Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (SIRS) requiring epinephrin support. Early response assessment revealed persisting AML in the bone marrow. After having recovered from the sepsis, he developed a rapid relapse with WBCs rising up to 150 000/µL within 1 week (B,C). Intermediate-dose cytarabine plus mitoxantrone was administered as salvage treatment. In the consecutive aplasia, our patient received allogeneic stem cell transplantation from a matched unrelated donor after reduced-intensity conditioning with busulfan and fludarabin, leading to a rapid engraftment and the establishment of a stable donor chimerism. This case is highly suggestive for cerebral manifestations of leukostasis, possibly associated with extravasation and extramedullary infiltration of myeloid blasts. Primary refractory disease could be overcome by higher-dose cytarabine salvage treatment, and sustained response of this high-risk disease could be achieved by allogeneic stem cell transplantation. (A) T2-weighted axial plane of cranial MRI scan showing multiple brain hemorrhages (in correlation with other sequences) at the stage of extracellular methemoglobin with marked perifocal edema. (B) Peripheral-blood sample from patient 2 at hyperleukocytotic relapse (containing EDTA for anticoagulation). Cell settlement revealed a pronounced buffy coat containing excessive numbers of leukemic cells (left tube) as opposed to blood from an age-matched healthy man (right tube). (C) Peripheral-blood smear of patient 2 at hyperleukocytotic relapse (May-Grünwald and Giemsa stain, ×400) showing numerous myeloid blasts with wide cytoplasm and large euchromatin-containing nuclei with 1 or more nucleoli.

Clinical case 2. A 68-year-old man sought medical help at the emergency unit of his local hospital because of weakness, bone pain, and night sweats over several weeks. He was admitted because of HL of ∼170 000/µL, anemia, and thrombocytopenia. After the diagnosis of AML M4 was made, HU and cytarabine were started, and the patient was transferred to our hospital, presenting with a WBC count 70 000/µL and central neurologic deficits with speech impairment. A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan showed several meningeal lesions, but the cerebrospinal fluid cell count was normal, and infection parameters were negative. In order to avoid cerebrospinal fluid contamination with leukemic blasts, lumbar puncture was postponed until peripheral blast clearance. We continued cytarabine induction and added daunorubicin for 3 days. WBC counts declined rapidly after initiation of cytarabine; the patient’s ability to speak improved gradually, and a control MRI 7 days after admission showed multiple hemorrhagic lesions, most pronounced in the hemispheres, with no signs of extramedullary leukemic lesions or meningeosis (A). In the consecutive aplasia, our patient developed Escherichia coli septicemia and Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (SIRS) requiring epinephrin support. Early response assessment revealed persisting AML in the bone marrow. After having recovered from the sepsis, he developed a rapid relapse with WBCs rising up to 150 000/µL within 1 week (B,C). Intermediate-dose cytarabine plus mitoxantrone was administered as salvage treatment. In the consecutive aplasia, our patient received allogeneic stem cell transplantation from a matched unrelated donor after reduced-intensity conditioning with busulfan and fludarabin, leading to a rapid engraftment and the establishment of a stable donor chimerism. This case is highly suggestive for cerebral manifestations of leukostasis, possibly associated with extravasation and extramedullary infiltration of myeloid blasts. Primary refractory disease could be overcome by higher-dose cytarabine salvage treatment, and sustained response of this high-risk disease could be achieved by allogeneic stem cell transplantation. (A) T2-weighted axial plane of cranial MRI scan showing multiple brain hemorrhages (in correlation with other sequences) at the stage of extracellular methemoglobin with marked perifocal edema. (B) Peripheral-blood sample from patient 2 at hyperleukocytotic relapse (containing EDTA for anticoagulation). Cell settlement revealed a pronounced buffy coat containing excessive numbers of leukemic cells (left tube) as opposed to blood from an age-matched healthy man (right tube). (C) Peripheral-blood smear of patient 2 at hyperleukocytotic relapse (May-Grünwald and Giemsa stain, ×400) showing numerous myeloid blasts with wide cytoplasm and large euchromatin-containing nuclei with 1 or more nucleoli.

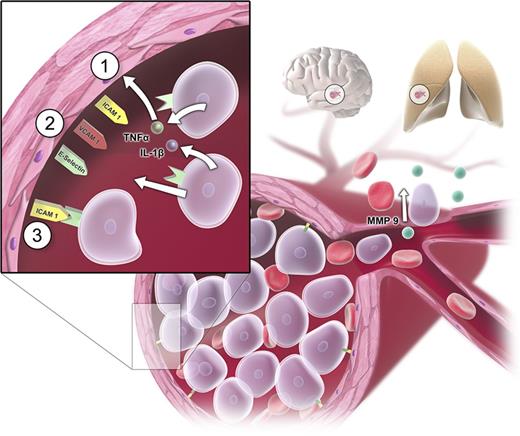

Two main pathogenetic factors are responsible for the development of HL: first, a rapid blast proliferation leading to a high leukemic tumor burden; second, disruption in normal hematopoietic cell adhesion leading to a reduced affinity to the bone marrow.17 The high number of leukocytes may cause 3 main complications: disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), tumor lysis syndrome (TLS), and leukostasis. DIC is caused by high cell turnover and associated high levels of released tissue factor, which then triggers the extrinsic pathway via factor VII.18 TLS may occur as a result of spontaneous or treatment-induced cell death. Leukostasis is explained by 2 main mechanisms. The rheological model is based on a mechanical disturbance in the blood flow by an increase of viscosity in the microcirculation.19,20 The fact that myeloid blasts are larger than immature lymphocytes or mature granulocytes and that leukemic blasts are considerably less deformable than mature leukocytes explains the higher incidence of leukostatic complications in AML as opposed to ALL, chronic myeloid leukemia, or chronic lymphocytic leukemia.8,21-23 However, the observation that there is no clear correlation between the leukocyte count and the severity and frequency of leukostatic complications6,24,25 points toward additional cellular mechanisms involved in the genesis of leukostasis such as interactions between leukemic cells and the endothelium,26,27 mediated by adhesion molecules.28 Bug et al described a significant association between expression of CD11c and a high risk of early death in leukocytosis.29 Stucki and coworkers observed a secretion of tumor necrosis factor-α and interleukin-1β by leukemic myeloblasts leading to change in the makeup of adhesion molecules on the endothelial cells.30 Several molecules such as intracellular adhesion molecule-1, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1, and E-selectin were shown to be upregulated. By this mechanism, leukemic cells can promote their own adhesion to the endothelium and create a self-perpetuating loop in which more and more blast cells migrate and attach to the endothelium.30 Additionally, cytokine-driven endothelial damage, subsequent hemorrhage, hypoxic damage, and AML blast extravasation followed by consecutive tissue damage by matrix metalloproteases might contribute to the pathogenesis of leukostasis.31-34 Important mechanisms of leukostasis are shown in Figure 3.35-37

Pathogenetic mechanisms in leukostasis. Sludging of circulating myeloblasts causes mechanical obstruction of small vessels and consecutive malperfusion in the microvasculature (eg, in organs such as brain and lungs). Apart from the mechanical obstruction, myeloblasts adhere to the endothelium by inducing endothelial cell adhesion receptor expression including E-selectin, P-selectin, intracellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1). Myeloblasts can promote their own adhesion to unactivated vascular endothelium by secreting tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), or additional stimulating factors (sequence of events represented by steps 1 to 3).30 Additional changes after cytokine-driven endothelial cell activation can be a loss of vascular integrity and modification of endothelial phenotype from antithrombotic to prothrombotic phenotype.35,36 Endothelial disintegration allows myeloblast migration and blood extravasation and microhemorrhages. Tissue invasion of myeloblasts is mediated by metalloproteinases (MMPs; particularly MMP-9), which are expressed on the cellular surface and secreted into the extracellular matrix.31,33,34,37

Pathogenetic mechanisms in leukostasis. Sludging of circulating myeloblasts causes mechanical obstruction of small vessels and consecutive malperfusion in the microvasculature (eg, in organs such as brain and lungs). Apart from the mechanical obstruction, myeloblasts adhere to the endothelium by inducing endothelial cell adhesion receptor expression including E-selectin, P-selectin, intracellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1). Myeloblasts can promote their own adhesion to unactivated vascular endothelium by secreting tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), or additional stimulating factors (sequence of events represented by steps 1 to 3).30 Additional changes after cytokine-driven endothelial cell activation can be a loss of vascular integrity and modification of endothelial phenotype from antithrombotic to prothrombotic phenotype.35,36 Endothelial disintegration allows myeloblast migration and blood extravasation and microhemorrhages. Tissue invasion of myeloblasts is mediated by metalloproteinases (MMPs; particularly MMP-9), which are expressed on the cellular surface and secreted into the extracellular matrix.31,33,34,37

Clinical manifestations and treatment options

Leukostasis, DIC, and TLS represent the 3 main clinical manifestations of HL, which can cause life-threatening complications in AML patients. Early mortality in this patient group is higher than in AML without HL and ranges from 8% in the first 24 hours9 to ∼20% during the first week,9,38-40 the main causes of death being bleeding, thromboembolic events, and neurologic and pulmonary complications. In AML without HL, the early death rate is significantly lower, ranging from ∼3% to 9%.41 However, also in long-term follow-up, HL is a negative prognostic factor as indicated by significantly shorter overall survival (OS)1,5,42 In our Study Alliance Leukemia study group database capturing 3510 intensively treated patients with an age range between 15 and 87 years, early death in HL vs all other AMLs was 6% vs 1% (P < .001) after 1 week and 13% vs 7% after 30 days (P < .001). The 5-year OS was 28% vs 31% indicating a small but significant prognostic difference (P = .004). When early death patients were excluded in the analysis of relapse-free survival (RFS), HL was still associated with an unfavorable prognosis as shown in 5-year RFS rates of 30% and 34% (P = .005). In multivariate analyses of OS and RFS accounting for the influence of other established prognostic factors such as age, cytogenetic risk, FLT3, NPM1, secondary AML, lactate dehydrogenase, and ECOG, HL retained its significant impact on prognosis (C.R. and G.E., unpublished data).

Because of excessive early mortality, HL in AML is a medical emergency, and treatment should start immediately.

DIC

DIC is a coagulopathy induced by the formation of small clots consuming coagulation proteins and platelets, resulting in disruption of normal coagulation and severe bleeding tendency.43 Acute DIC is characterized by a decrease in platelet count and fibrinogen, an elevation of d-dimers, and prolongation of prothrombin time and activated partial thromboplastin time and occurs in 30% to 40% of HL-AML.24 Platelet transfusions and standard measures to restore normal coagulation such as substitution of fresh frozen plasma or fibrinogen44 should be initiated immediately in these patients because not only the deranged coagulation itself but also HL and the associated endothelial damage put the patient at a considerable risk for severe and sometimes fatal bleeding events. In patients without central nervous manifestations and no anticoagulation, platelet counts should be ∼20 000 to 30 000/µL; in patients with full heparin anticoagulation, ∼50 000/µL. In the subgroup of acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL), induction of differentiation by administration of all-trans retinoid acid (ATRA) is the causal and most important treatment of DIC and should be started in all suspicious cases even before cytological and cytogenetic or molecular proof.45

TLS

Although TLS is more common in lymphoid malignancies and ALL, it can also occur in AML. In patients with leukostasis, TLS occurs in up to 10% of cases.21 There is no evidence that low-dose cytostatic treatment with a slow and gradual leukocyte reduction decreases the risk of tumor lysis as opposed to standard-dose intensive induction.46 In patients with a curative treatment concept, intensive chemotherapy should therefore start immediately and without a “prephase.” Prevention strategies include hydration and prophylactic allopurinol. Close monitoring during the first days of treatment will reveal tumor lysis characterized by elevation of serum potassium, phosphorus, and uric acid levels and potentially by decline in calcium levels. Hyperuricemia can lead to acute renal damage or even failure and should be treated with allopurinol or rasburicase depending on the uric acid levels. Established TLS is managed similarly, with the addition of aggressive hydration and diuresis, plus allopurinol or rasburicase for hyperuricemia. Additionally, electrolyte imbalances should be corrected. Whereas allopurinol is the less expensive therapy for hyperuricemia, it only prevents the synthesis of new uric acid. In cases with marked hyperuricemia and TLS, rasburicase (urate oxidase) effectively lowers uric acid levels by enzymatic degradation, even after a single and low-dose application.47-51

Leukostasis

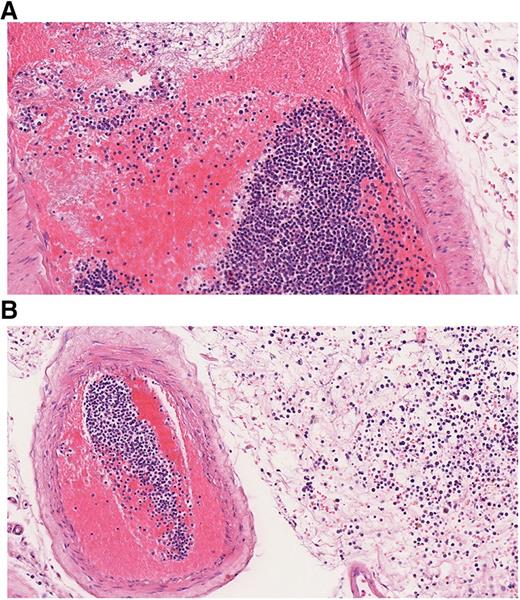

Leukostasis refers to clinical symptoms and complications caused by HL. Whereas pathologically, the definition of leukostasis is clear (Figure 4), the clinical diagnosis is rarely made with high confidence.43 Leukostasis is empirically diagnosed when patients present with acute leukemia, HL, and respiratory or neurologic symptoms. However, the clinical and radiographic manifestations of leukostasis are difficult to distinguish from those of common infections or hemorrhagic complications of acute leukemia.24 Novotny et al39 developed a score for the clinical probability of leukostasis, and Piccirillo et al40 showed a correlation between Novotny’s score and early death in the case of a score of 3 indicating highly probable leukostasis. Approximately 44% to 50% of AML patients with a WBC count >100 000/µL have a high probability of leukostasis based on clinical symptoms. Although less frequently, typical symptoms can also occur in patients with leukocytosis below 100 000/µL.39,40 Organs most frequently affected are lung, brain, and kidneys. In a study by Porcu et al, the proportions of patients with respective symptoms were 39%, 27%, and 14%.6 Similar frequencies were reported by other investigators.9,29,52 CT scan or MRI of the head may reveal intracranial hemorrhage (Figures 1 and 2). A chest radiograph or CT scan often will show bilateral interstitial or alveolar infiltrates (Figure 1).43,53 The typical clinical symptoms of leukostasis are listed in Table 1. Apart from tissue damage caused by stasis and leukocyte infiltration, hemorrhage and thromboembolic events are frequent and relevant complications of leukostasis. 9,19,43

Histopathological finding in leukostasis. Specimen from the leptomeninges of an AML patient postmortem stained with hematoxylin and eosin (×200). (A) Large numbers of immature WBCs in a leptomeningeal capillary artery presumably leading to reduced blood flow and thrombus formation with strands of fibrin, red blood cells (RBCs), and WBCs. (B) Numerous myeloid blasts and some RBCs are present in the extravascular space, infiltrating the leptomeningeal tissue.

Histopathological finding in leukostasis. Specimen from the leptomeninges of an AML patient postmortem stained with hematoxylin and eosin (×200). (A) Large numbers of immature WBCs in a leptomeningeal capillary artery presumably leading to reduced blood flow and thrombus formation with strands of fibrin, red blood cells (RBCs), and WBCs. (B) Numerous myeloid blasts and some RBCs are present in the extravascular space, infiltrating the leptomeningeal tissue.

Symptoms of leukostasis

| Organ . | Symptoms . |

|---|---|

| Lung | Dyspnea, hypoxemia, diffuse alveolar hemorrhage, respiratory failure |

| Central nervous system | Confusion, somnolence, dizziness, headache, delirium, coma, focal neurologic deficits |

| Eye | Impaired vision, retinal hemorrhage |

| Ear | Tinnitus |

| Heart | Myocardial ischemia/infarction |

| Vascular system | Limb ischemia, renal vein thrombosis, priapism |

| Organ . | Symptoms . |

|---|---|

| Lung | Dyspnea, hypoxemia, diffuse alveolar hemorrhage, respiratory failure |

| Central nervous system | Confusion, somnolence, dizziness, headache, delirium, coma, focal neurologic deficits |

| Eye | Impaired vision, retinal hemorrhage |

| Ear | Tinnitus |

| Heart | Myocardial ischemia/infarction |

| Vascular system | Limb ischemia, renal vein thrombosis, priapism |

Immediate initiation of cytoreductive treatment in this chemosensitive disease is mandatory and should not be delayed.43,54 In case a rapid diagnosis cannot be made, the patient should be transferred to a specialized hospital on the same day. Whereas there are widely agreed upon and accepted standards for the treatment of DIC and TLS, the use of leukapheresis in HL and the mode of cytoreduction are still a matter of debate.

Cytoreduction

Hydroxyurea is commonly used before a proper induction regimen is implemented in order to lower the tumor burden and reduce the risk of tumor lysis. However, there are no data indicating that this approach is superior to immediate induction or that tumor lysis can be prevented by a low-dose cytoreduction strategy. Results of a recent systematic review lack evidence for the superiority of this approach over standard-dose induction.46 In all patients eligible for intensive curative treatment, standard-dose or high-dose cytarabine plus anthracyclin or mitoxantrone should be initiated as soon as the HL diagnosis is made.55,56 This applies to all HL patients with AML, both with and without signs of leukostasis. In cases with unclear HL, HU may be used short term as bridging strategy (Figure 1). If respiratory failure develops despite falling WBC counts, pneumonia or cytarabine-induced pulmonary damage57,58 should be considered and treated accordingly. In APL, treatment with ATRA should be initiated immediately, even if APL is only suspected. After APL confirmation, idarubicin or arsenic trioxide should be added for proper cytoreduction treatment.59

Leukapheresis

The term leukapheresis stems from the Greek “to take away” or “to remove.”43 Leukapheresis in HL is based on the principle of rapidly removing excessive leukocytes by mechanical separation. The mechanical removal of leukocytes by leukapheresis has become routinely available in many hematologic treatment centers. If apheresis equipment is not available, judicious phlebotomies with concurrent blood and/or plasma replacement may be used as an alternative strategy to reduce HL.43 In modern apheresis devices (blood cell separators), WBCs and their precursors are separated from patients’ blood by centrifugation. During a single leukapheresis, the WBC count can be reduced by 10% to 70%.60 The efficacy of leukapheresis to reduce the number of WBCs has been shown in several clinical trials. However, there are 2 main reasons why the use of leukapheresis in HL patients is still under debate. First, the majority of the leukemic burden is located in the bone marrow.61 These cells are rapidly mobilized into the peripheral blood shortly after a successful leukapheresis.24 The second and more important reason is that a beneficial clinical effect on early clinical outcomes could not be shown consistently in clinical trials. From what we know from all clinical trials employing leukapheresis in HL patients, long-term prognosis cannot be changed (ie, relapse risk is higher and OS is shorter in AML patients with initial HL). Concerning the prevention of early complications and early death, several clinical trials delivered heterogeneous results. In a systematic review, Oberoi et al46 identified 14 studies using leukapheresis systematically or occasionally in 420 children and adult patients with HL AML. One additional study with 45 patients generally not using leukapheresis was added for comparison. The results of the trials could not be synthesized because of heterogeneity, but there was neither a trend for higher or lower early death in patients with and without leukapheresis nor did the early death rates differ depending on the leukapheresis strategy used (systematically vs occasionally vs not). In a comparison between institutions with leukapheresis in all HL patients and institutions using a “never” or “sometimes” policy, no beneficial effect could be shown. Similarly, the investigators of this comprehensive review did not observe an inverse relationship between the percentage of patients receiving a leukapheresis and the incidence of early death.46 Pastore et al9 analyzed an HL patient population based on a score correcting for disease-related risk factors in order to separate the leukapheresis effect on early death. According to their analysis, leukapheresis had no beneficial effect on early death, irrespective of the individual early death risk.9 All trials were retrospective and not randomized, and it is unlikely that such studies will ever be feasible given the rarity of the condition, urgency for decision making, and strong physician preferences.

As part of a discussion, the efficient reduction of WBCs and the standardized and generally well-tolerated procedure are brought forward as arguments for using leukapheresis, whereas hypercalcemia, the use of anticoagulants, aggravation of preexisting thrombopenia,24 and the potential need for a central venous access43,46,61,62 may put patients at procedural risk on top of their unstable condition. Last but not least, infrastructural requirements and costs linked to leukapheresis have to be taken into account.

In conclusion, leukapheresis may be beneficial in patients presenting with a manifest leukostasis syndrome because leukapheresis represents a causal therapeutic principle. Based on a grading score for the probability of leukostasis in leukemia patients with HL and a validation analysis, patients with distinct symptoms have a high risk of leukostasis-related early death (Table 1).39,40 Contraindications such as cardiovascular comorbidities, hemodynamic instability, and coagulation disturbances should be evaluated carefully in order to avoid an extra procedural risk for the patient. Patients with a manifest leukostasis in relation to HL and without contraindications should receive daily leukapheresis. The blood volume to process should be between 2 and 4 times the patient’s blood volume. Clinical controls for hypocalcemia-induced paresthesia and monitoring of oxygen saturation, blood pressure, and heart rate are recommended during the intervention. If >20% of the patient’s blood volume has been collected, fluid replacement with colloids or human albumin is recommended. Red cell transfusions should be given only if inevitable and only at the end of leukapheresis in order to avoid further increase of blood viscosity.63 Leukapheresis can be repeated daily until symptoms of leukostasis have disappeared or the WBC count is below 100 × 109/µL.60,63 Cytoreductive treatment should start immediately at diagnosis of HL AML and must not be delayed or postponed by the leukapheresis procedure.

There is no evidence for a beneficial effect of leukapheresis in HL patients without clinical symptoms of leukostasis. Prophylactic leukapheresis offers no advantage over intensive induction chemotherapy and supportive care, including those patients with TLS.46,63 Based on the pros and cons of the procedure, a routinely performed prophylactic leukapheresis cannot be recommended. In APL, leukapheresis might worsen the coagulopathy and increase the rate of complications and is therefore not recommended.64

Future research evaluating therapies targeting cytokines and adhesion molecules involved in myeloblast-endothelium interactions may be worth exploring.46

Conclusion: how I treat HL in AML

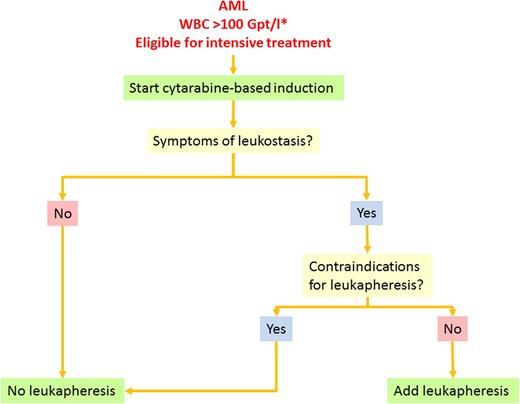

Based on these facts and considerations, we follow the treatment algorithm shown in Figure 5. In patients with AML and HL, we assess eligibility for intensive treatment. Treatment-eligible patients start with standard induction treatment combining standard-dose cytarabine plus daunorubicin (7 + 3). In parallel, we provide intravenous hydration to ensure adequate urine flow, use allopurinol or rasburicase to reduce serum uric acid levels, and check for signs of DIC or tumor lysis twice daily until the WBC count has fallen below upper normal limits. Patients with suspected APL should receive ATRA immediately and additionally idarubicin after cytological or genetic APL confirmation. In addition to idarubicin, the WBC count is further reduced by HU until normal levels have been reached. DIC and TLS are treated with standard supportive measures as mentioned previously. RBC transfusions are withheld whenever possible until the WBC count is reduced. If a transfusion is necessary, it is administered slowly. We give prophylactic platelet transfusions to maintain a count of >20 000 to 30 000/µL or 50 000/µL in case of full heparin anticoagulation until the WBC count has been reduced and the clinical situation has been stabilized. Patients without leukostasis symptoms are not scheduled for leukapheresis. Patients with a clinically high likelihood of leukostasis are checked for contraindications for leukapheresis such as APL, coagulation disorders, cardiovascular comorbidities, or instable circulation. Patients without contraindications are scheduled to receive leukapheresis with a target WBC count below 100 000/µL or the disappearance of clinical symptoms. In patients with contraindications for immediate intensive induction treatment such as severe metabolic disturbances or renal insufficiency, we use HU for cytoreduction.

Treatment algorithm for AML with hyperleukocytosis. Supportive therapy such as hydration, prophylaxis of TLS, and anti-infective treatment is necessary for all patients. The asterisk indicates that the algorithm also applies to patients with leukocytosis <100 Gpt/L who present with symptoms suggestive for leukostasis.

Treatment algorithm for AML with hyperleukocytosis. Supportive therapy such as hydration, prophylaxis of TLS, and anti-infective treatment is necessary for all patients. The asterisk indicates that the algorithm also applies to patients with leukocytosis <100 Gpt/L who present with symptoms suggestive for leukostasis.

Once CR has been achieved, we make a decision on consolidation treatment depending on donor availability and cytogenetic risk. If the standard induction does not lead to CR, we use a salvage regimen based on high-dose cytarabine, possibly including novel investigational drugs. In first CR, we recommend a patient with intermediate or adverse cytogenetic risk and an available matched donor to undergo allogeneic stem cell transplantation in first remission based on the high relapse probability of hyperleukocytotic AML after conventional chemotherapy consolidation. In all other cases including core binding factor leukemias without c-kit mutations, standard chemotherapy with high-dose cytarabine will be used as consolidation. Whenever possible, treatment should be part of a clinical trial or registry in order to gain more knowledge and to improve treatment options in the future.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Michael Laniado (Institut und Poliklinik für Radiologische Diagnostik, Universitätsklinikum der Technischen Universität [TU] Dresden) and Rüdiger von Kummer and Dirk Daubner (Abteilung Neuroradiologie, Universitätsklinikum TU Dresden) for providing radiographic material for Figures 1 and 2A. The authors also thank Gustavo Baretton, Christian Zietz, and Friederike Kuithan (Institut für Pathologie, Universitätsklinikum TU Dresden) for tissue sections and their interpretation in Figure 4, and Christiane Külper and Marika Erler (Medizinische Klinik und Poliklinik I, Universitätsklinikum TU Dresden) for technical assistance on cytological specimens in Figure 2C.

Authorship

Contribution: G.E. and C.R. wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Christoph Röllig, Universitätsklinikum TU Dresden, Fetscherstrasse 74, 01307 Dresden, Germany; e-mail: christoph.roellig@uniklinikum-dresden.de.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal