Key Points

Notch1 induction promotes specification of hemogenic endothelial cells during embryonic stem cell differentiation.

Foxc2 functions downstream of Notch in specification of hemogenic endothelium in mouse and zebrafish embryos.

Abstract

Hematopoietic and vascular development share many common features, including cell surface markers and sites of origin. Recent lineage-tracing studies have established that definitive hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells arise from vascular endothelial–cadherin+ hemogenic endothelial cells of the aorta-gonad-mesonephros region, but the genetic programs underlying the specification of hemogenic endothelial cells remain poorly defined. Here, we discovered that Notch induction enhances hematopoietic potential and promotes the specification of hemogenic endothelium in differentiating cultures of mouse embryonic stem cells, and we identified Foxc2 as a highly upregulated transcript in the hemogenic endothelial population. Studies in zebrafish and mouse embryos revealed that Foxc2 and its orthologs are required for the proper development of definitive hematopoiesis and function downstream of Notch signaling in the hemogenic endothelium. These data establish a pathway linking Notch signaling to Foxc2 in hemogenic endothelial cells to promote definitive hematopoiesis.

Introduction

Generating hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) from embryonic stem cells (ESCs) remains challenging despite considerable efforts. Although genetic modification with HoxB4 and Cdx4 enables hematopoietic progenitors derived from murine embryoid bodies (EBs) to reconstitute multilineage hematopoiesis in primary and secondary mice, these ESC-derived HSCs remain distinct from bone marrow–derived HSCs.1,2 Live imaging of hematopoietic differentiation from ESCs has shown that CD41+ cells arise from hemogenic endothelial cells that express vascular endothelial (VE)–cadherin or tyrosine kinase with Ig and EGF homology domains-2 and later express the hematopoietic marker CD45.3,4 In vivo lineage tracing in mice using a tamoxifen-inducible VE-cadherin Cre transgene has shown that pulse induction during the aorta-gonad-mesonephros (AGM) stage of hemogenesis abundantly labels fetal liver, bone marrow, and thymic hematopoietic cells, and constitutive induction marks the vast majority of adult blood cells. These reports strongly indicate that definitive hematopoietic cells, which replace transient primitive hematopoietic cells during embryo development, arise from hemogenic endothelium.5-8

Notch signaling has been implicated in cell-fate decisions and differentiation of various cell types, including endothelial cells and blood cells.9-11 Upon ligand activation, the intracellular domain of Notch (ICN or NICD) is cleaved at the plasma membrane and translocates to the nucleus where it binds to the transcription factor CSL (for CBF1/Su(H)/Lag-1, also known as Rpbsuh or RBP-jκ) to activate expression of downstream targets such as Hes and Hey genes.12 Organ culture of the Notch1 null E9.5 para-aortic splanchnopleura, which later develops into the AGM, has revealed marked impairment of vascular network formation and hematopoietic cell development, whereas colony-forming cell (CFC) activity was preserved in the yolk sac.13-15 In situ hybridization of para-aortic splanchnopleura/AGM from E9.5 and E10.5 wild-type embryos showed that Notch1 expression was restricted to the ventral wall of the dorsal aorta.15 These studies suggest that Notch1 is a key regulator of hemogenic endothelial cells.

The forkhead box (Fox) family of transcription factors is an evolutionarily ancient gene family that has expanded to more than 40 members in mammals.16 In mice, Foxc1 and Foxc2 are essential for arterial specification before the onset of circulation by directly inducing transcription of a Notch ligand, Delta-like 4.17-19 A recent study has also shown that Foxc2 binds to the VE-cadherin enhancer and directly activates its transcription.20 Although the roles of Foxc genes are well established in angiogenic remodeling, there is currently no link between Fox genes and HSC emergence.

In this study, we generated ESCs with a doxycycline (Dox)–inducible intracellular domain of Notch1 (ICN1) and analyzed the effect of induction during EB differentiation. ICN1 induction expanded VE-cadherin+ hemogenic endothelial cells and enhanced hematopoietic potential. Expression analysis of the ICN1-induced VE-cadherin+ population showed the upregulation of Foxc2, which we discovered using genetic analyses in both zebrafish and mice functions downstream of Notch signaling in hemogenic endothelium. Thus, we demonstrate that the Notch pathway promotes the maturation of hemogenic endothelium via Foxc2, establishing Foxc2 as a key factor in promoting definitive hematopoiesis.

Materials and methods

ESC culture, cloning, and EB differentiation

Ainv15 murine ESCs were maintained on mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium with 15% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (IFS) (HyClone Laboratories, Logan, UT), 1000 U/mL leukemia inhibitory factor, 0.1 mM nonessential amino acids, 2 mM penicillin/streptomycin/glutamate, and 100 μM β-mercaptoethanol at 37°C/5% CO2. Dox-inducible ICN1 embryonic stem cell line was generated after subcloning ICN1 complementary DNA (cDNA; generously provided by David Scadden21 ) into plox vector (MluI and XbaI sites with blunt ligation) and targeting Ainv15 ESCs with pSALK-Cre.22

Murine Foxc2 cDNA with a flag tag at the 3′ terminus was cloned downstream of the tetO minimal promoter of pBS31’ vector and coelectroporated with pCAGGS FLPε plasmid into murine KH2 embryonic stem cell line at 500 V and 25 μF using Gene PulserII.23 The colonies were selected in hygromycin at 140 μg/mL for 10 days, and the resistant clones were subjected to Foxc2 screening by Immunoblotting.

ESCs were differentiated into EBs after removing MEFs and cultured in Iscove modified Dulbecco medium (IMDM) with 15% fetal calf serum (Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, BC), 200 μg/mL holo-transferrin, 50 μg/mL ascorbic acid, 2 mM penicillin/streptomycin/glutamate, and 450 μM monothioglycerol as described previously.24

Immunoblotting

Immunoblotting was performed with sodium dodecyl sulfate– polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transfer system (Bio-Rad). ICN1 was detected with anti-Notch1 antibody (sc-6014; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibodies and developed using the Enhanced Chemiluminescence kit.

Methylcellulose CFC, OP9 colony, and HE culture

Day 6 EBs were dissociated by treatment of collagenase IV (2 mg/mL), hyaluronidase (10 mg/mL), DNase (160 U/mL), and trituration with enzyme-free dissociation buffer (Invitrogen). Cells were mixed into methycellulose media (M3434, StemCell Technologies) and put in nonadherent 30-mm2 nontreated dishes (StemCell Technologies). Colonies were counted at day 4 (EryP) and day 8 (others) or day 10. OP9 cells were maintained in α-minimum essential medium with 20% IFS and 2 mM penicillin/streptomycin/glutamine. Day 6 EB-derived cells were cultured on OP9 cells in IMDM with 10% IFS, 100 ng/mL human fms-related tyrosine kinase 3 ligand, 100 ng/mL human stem cell factor, 40 ng/mL human thyroid peroxidase, and 40 ng/mL murine vascular endothelial growth factor (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ), and 2 mM penicillin/streptomycin/glutamine, and colonies were counted 4 to 6 days later. For hematopoietic and endothelial (HE) culture, day 6 EB-derived cells were cultured in IMDM containing 10% fetal calf serum, 10% equine serum, 5 ng/mL murine vascular endothelial growth factor, 10 ng/mL insulin-like growth factor 1, 2 U/mL erythropoietin, 10 ng/mL basic fibroblast growth factor, 50 ng/mL interleukin 11, 100 ng/mL murine stem cell factor, 100 μg/mL endothelial cell growth supplement, 2 mM penicillin/streptomycin/glutamate, and 450 μM monothioglycerol on matrigel-coated plates.25

Fluorescence-activated cell sorter, sorting, and real-time RT-PCR

Day 6 EB-derived cells were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate anti-CD41, purified rat anti-mouse CD144, phycoerythrin mouse anti-rat IgG2a, allophycocyanin anti-CD45, phycoerythrin-Cy7 anti-CD49d (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), and 7AAD (Sigma-Aldrich). Cells were analyzed by using FACSCalibur/Canto or sorted by Aria. For real-time reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), cells were harvested into TRIzol (Invitrogen) and total RNA was isolated with treatment of DNase I (Ambion, Austin, TX). After preparing cDNA (Superscript II, Invitrogen), quantitative PCR was performed using SYBR Green (Strategene, La Jolla, CA) on MX3000P with indicated primers,24,26 and the expression was normalized to β-actin (ICN1, forward: ATGCTGGAGGACCTCATCAACTCA, reverse: TGAACAATGTGGATGCCGCAGTTG; Foxc2, forward: AACCCAACAGCAAACTTTCCC, reverse: GCGTAGCTCGATAGGGCAG, PrimerBank ID 8850213a1).

Further experimental procedures are described in supplemental Experimental Methods (available on the Blood Web site).

Results

Promotion of hematopoiesis with ICN1 induction during mouse EB differentiation

Notch signaling is involved in multiple steps of tissue specification and progenitor cell maturation during embryo development.9,27 To test the effect of Notch1 signaling on early blood lineage development, we cloned the ICN1 into the plox vector, and targeted Ainv15 ESCs to generate the Dox-inducible ICN1 line (iICN1).21,22 After confirming ICN1 induction with Dox (Figure 1A), we differentiated ESCs into EBs and observed the effects of ICN1 induction over specific time periods on the number of hematopoietic CFCs at day 6 (Figure 1B). ICN1 induction on single days from days 3 to 5 resulted in increased colony numbers, and a 2-day induction (ICN 3-5) resulted in higher colony numbers than either single-day or 3-day induction; a similar pattern was observed for hematopoietic colonies that form on OP9 stroma (Figure 1C). These results show that timed induction of Notch signaling promotes hematopoietic development of EBs.

ICN1 induction during EB differentiation enhances hematopoietic development. (A) Induction of ICN1 24 hours after adding Dox (0.5 μg/mL) during ESC culture is shown by real-time RT-PCR (left) and immunoblotting (right). (B) Methylcellulose (M3434) CFC counts from day 6 iICN1 EB-derived cells with indicated day(s) of ICN1 induction by Dox (0.5 μg/mL) are shown. A representative of 3 independent experiments is shown. (C) OP9 stromal cell colony counts from day 6 iICN1 EB-derived cells with indicated day(s) of ICN1 induction with Dox (0.5 μg/mL) are shown. n = 3; *P < .05 by Student t test in comparison with noninduced control.

ICN1 induction during EB differentiation enhances hematopoietic development. (A) Induction of ICN1 24 hours after adding Dox (0.5 μg/mL) during ESC culture is shown by real-time RT-PCR (left) and immunoblotting (right). (B) Methylcellulose (M3434) CFC counts from day 6 iICN1 EB-derived cells with indicated day(s) of ICN1 induction by Dox (0.5 μg/mL) are shown. A representative of 3 independent experiments is shown. (C) OP9 stromal cell colony counts from day 6 iICN1 EB-derived cells with indicated day(s) of ICN1 induction with Dox (0.5 μg/mL) are shown. n = 3; *P < .05 by Student t test in comparison with noninduced control.

Promotion of hemogenic endothelial cells with ICN1 induction

Recent lineage-tracing experiments in the mouse have shown that definitive hematopoietic populations arise from hemogenic endothelial cells that express VE-cadherin and can be detected in the AGM region.5,6,28 CD41 has been reported to mark embryonic hematopoietic precursors prior to CD45 expression.29,30 Continuous single-cell imaging has shown that the VE-cadherin+ population derived from fetal liver kinase 1 (Flk1)+ cells can give rise to CD41+ and eventually CD45+ cells.3 When day 6 EB cells were analyzed for CD41 and VE-cadherin expression by flow cytometry, ICN1 induction from days 3 to 5 (ICN 3-5) increased the VE-cadherin single positive (VE SP) population up to twofold (Figure 2A) compared with uninduced control (ICN 0). The majority of the VE SP population (60% to 75%) was also positive for α4-integrin, another marker of hemogenic endothelial cells required for proliferation and differentiation of multilineage hematopoietic progenitors in the embryo.31 In day 6 EBs, there was little change in Flk1, CD45, tyrosin-protein kinase kit, stem cell antigen-1, or CD41 positive populations following ICN1 induction (data not shown). When we induced ICN1 during blast colony development, in which the hemogenic endothelial core first develops and hematopoietic blast colony cells bud off from the core, development stopped at the core level with a dramatic decrease in core colony formation (supplemental Figure 1A). However, the cells harvested from the ICN1-induced blast colony assay generated more hematopoietic colonies compared with the same number of cells from the control (supplemental Figure 1B). These results suggest that ICN1 induction promotes hematopoietic development through the promotion of hemogenic endothelium.

ICN1 induction promotes VE-cadherin+ hemogenic endothelial cell specification. (A) Flow cytometric analysis of day 6 iICN1 EBs with (ICN 3-5) or without (ICN 0) Dox induction (0.5 μg/mL) from days 3 to 5 is shown. (B) CD45− VE SP cells were sorted from day 6 iICN1 EBs with (ICN 3-5) or without (ICN 0) Dox induction (0.5 μg/mL) from days 3 to 5, and the same number of sorted cells was subjected to HE culture. Flow cytometric analysis of day 4 HE culture is shown. (C) The cumulative average of CD45+ cells of days 2, 4, and 6 HE culture is shown. n = 3; *P < .05 by Student t test in comparison with noninduced control. (D) Cytospins of day 10 HE culture of CD45− CD41 SP, VE SP, and DP cells from day 6 iICN1 EBs with (ICN 3-5) or without (ICN 0) Dox induction (0.5 μg/mL) from days 3 to 5 are shown. ICN1 was not induced in HE culture. Representatives of 3 independent experiments are shown.

ICN1 induction promotes VE-cadherin+ hemogenic endothelial cell specification. (A) Flow cytometric analysis of day 6 iICN1 EBs with (ICN 3-5) or without (ICN 0) Dox induction (0.5 μg/mL) from days 3 to 5 is shown. (B) CD45− VE SP cells were sorted from day 6 iICN1 EBs with (ICN 3-5) or without (ICN 0) Dox induction (0.5 μg/mL) from days 3 to 5, and the same number of sorted cells was subjected to HE culture. Flow cytometric analysis of day 4 HE culture is shown. (C) The cumulative average of CD45+ cells of days 2, 4, and 6 HE culture is shown. n = 3; *P < .05 by Student t test in comparison with noninduced control. (D) Cytospins of day 10 HE culture of CD45− CD41 SP, VE SP, and DP cells from day 6 iICN1 EBs with (ICN 3-5) or without (ICN 0) Dox induction (0.5 μg/mL) from days 3 to 5 are shown. ICN1 was not induced in HE culture. Representatives of 3 independent experiments are shown.

When VE SP cells were sorted from day 6 EBs and put into HE culture, CD45+ cells were generated after 4 days of culture. From the same number of VE SP cells, more CD45+ cells were produced from ICN1-induced EBs (ICN 3-5) than controls (Figure 2B). The absolute numbers of CD45+ cells produced from the same number of VE SP cells in days 2, 4, and 6 HE culture showed 42% to 46% increase in cultures of ICN1-induced cells (Figure 2C; supplemental Table 1). With an assumption that a single VE SP cell generates a single CD45+ cell and proliferation rates of cells in HE culture are not different, we estimated the frequency of HE cells as 1/5.446 × 104 from control VE SP cells and 1/2.589 × 104 from ICN1-induced VE SP cells by limiting dilution analysis (supplemental Figure 2). Cytospin of day 10 HE culture showed a significant increase in hematopoietic cells from ICN1-induced VE SP cells, whereas no differences were seen between control and ICN1-induced CD41 single positive (CD41 SP) or double positive (DP) cells (Figure 2D). Moreover, day 10 HE culture of VE SP cells exhibited tube-forming ability (data not shown). When we analyzed the cell cycle in day 4 EBs following ICN1 induction from day 3, we observed an approximately twofold increase of BrdU+ VE-cadherin+ cells in ICN1-induced EBs (20.3% to 38.3%), which suggests that the increase in VE-cadherin+ cells in day 6 EBs following ICN1 induction could have been contributed by an increase in cell proliferation (supplemental Figure 3). Taken together, our data suggest that inducing Notch1 signaling during EB differentiation promotes proliferation and hematopoietic specification of hemogenic endothelial cells.

To understand whether ICN1 induction impacts hematopoietic differentiation in a cell-autonomous manner, we mixed murine ROSA-GFP ESCs, which constitutively express green fluorescent protein (GFP),32 with iICN1 ESCs, which are GFP−, to form EBs, and analyzed day 6 EBs with or without ICN1 induction from days 3 to 5. Flow cytometric analysis of day 6 EBs showed that GFP− cells showed the increase of VE SP population with ICN1 induction but GFP+ cells showed no change (supplemental Figure 4A-B). EBs made from iICN1 ESCs alone or ROSA-GFP ESCs alone showed the same results. When colony-forming activity was measured with sorted GFP+ or GFP− cells from mixed EBs, we observed an increase of colony-forming activity with ICN1 induction in GFP− cells but not in GFP+ cells (supplemental Figure 4C). Moreover, we observed the same patterns with EBs made from iICN1 ESCs alone or ROSA-GFP ESCs alone. These results indicate that ICN1 works in a cell-autonomous manner in promoting hematopoietic differentiation.

Upregulation of Foxc2 with ICN1 induction in hemogenic endothelial cells

Despite the long history of detecting hemogenic endothelial cells by surface marker expression, relatively little is known regarding the global gene expression profiles of these cells.7,33-38 To identify changes in the molecular signature of hemogenic endothelial cells following Notch induction, we isolated RNA from CD41 SP, VE SP, DP, and double negative populations of day 6 EBs and performed microarray analyses. Hierarchical clustering of global gene expression patterns showed that the relationship among these populations was unchanged by ICN1 induction (ICN 3-5) (Figure 3A). When genes whose expression levels were equal or higher than the twofold of the average gene expression level were plotted, the VE SP population showed the greatest number of genes upregulated by ICN1 induction (Figure 3B). Among upregulated genes in the VE SP population, Gata3 drew our attention because of its known roles in both endothelial and hematopoietic development.39,40 We then searched for genes with a similar expression pattern to Gata3 across different populations with or without ICN1 induction, and we identified Foxc2, along with C230093N12Rik, Lhfp, Timp2, and Fbn1. The increase of Foxc2 expression after ICN1 induction in the VE SP population was higher than that of Gata3 (Figure 3C). These results suggest that Foxc2, previously known to be involved in endothelial development, may have a role in the specification of hemogenic endothelium.

Foxc2 expression is upregulated in VE SP population after ICN1 induction. (A) CD45− CD41 SP, VE SP, DP, and double negative (DN) populations were sorted from day 6 iICN1 EBs with or without Dox induction (0.5 μg/mL) from days 3 to 5 during EB differentiation and subjected to microarray analysis for gene expression. Hierarchical clustering of populations is shown (Euclidean metric). The numbers, which are applied afterward, represent the corresponding sorted populations. (B) Genes with a similar expression pattern to Gata3 are indicated (Spearmann metric with cutoff 0.95 followed by Pearson metric with cutoff 0.9). Expression levels relative to average gene expression are plotted. (C) Genes with an increase in expression by twofold or higher after ICN1 induction in CD41 SP, VE SP, and DP population are listed from high to low expression. Genes showing an expression pattern similar to Gata3 are marked by a rectangular shade. Data were collected from 3 independent experiments.

Foxc2 expression is upregulated in VE SP population after ICN1 induction. (A) CD45− CD41 SP, VE SP, DP, and double negative (DN) populations were sorted from day 6 iICN1 EBs with or without Dox induction (0.5 μg/mL) from days 3 to 5 during EB differentiation and subjected to microarray analysis for gene expression. Hierarchical clustering of populations is shown (Euclidean metric). The numbers, which are applied afterward, represent the corresponding sorted populations. (B) Genes with a similar expression pattern to Gata3 are indicated (Spearmann metric with cutoff 0.95 followed by Pearson metric with cutoff 0.9). Expression levels relative to average gene expression are plotted. (C) Genes with an increase in expression by twofold or higher after ICN1 induction in CD41 SP, VE SP, and DP population are listed from high to low expression. Genes showing an expression pattern similar to Gata3 are marked by a rectangular shade. Data were collected from 3 independent experiments.

Defective definitive hematopoiesis in Foxc2 null mouse embryos

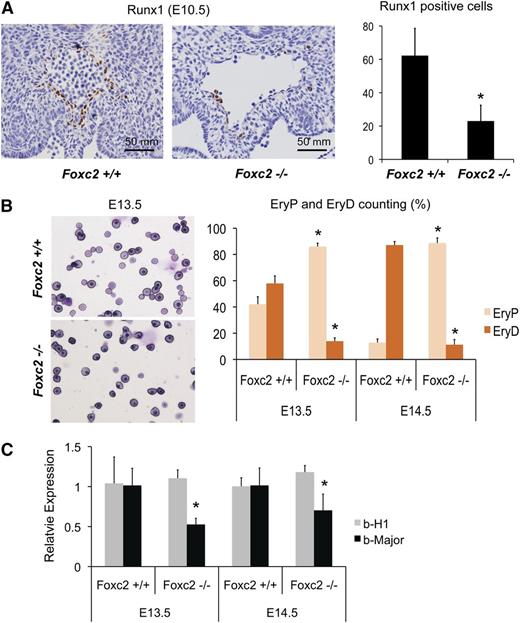

To test whether Foxc2 is involved in the specification of definitive hematopoiesis during embryo development, we analyzed Foxc2 null mouse embryos for hematopoietic phenotypes in comparison with wild-type littermates. Foxc2 null mouse embryos die perinatally or prenatally between E12 and E17 and display abnormal aorta morphology.41,42 When we measured the expression of Gata1, Gata2, and Gata3 in the liver of E13.5/E14.5 embryos, Gata3, but not Gata1 or Gata2, showed a decrease in E14.5 Foxc2−/− embryos compared with the control embryos (supplemental Figure 5). When the AGM of E10.5 Foxc2−/− embryos was stained with runt-related transcription factor 1 (Runx1), a definitive hematopoietic marker,43 we noted a significant decrease of Runx1-positive cells compared with control littermates (Figure 4A). Peripheral blood analysis showed a decrease in the ratio of definitive, enucleated erythrocytes (EryD) to primitive, nucleated erythroblasts (EryP) in E13.5 and E14.5 Foxc2−/− embryos (Figure 4B), and quantitative RT-PCR of peripheral blood showed a decrease in the β-major to β-H1 ratio (∼52% in E13.5 and ∼40% in E14.5, Figure 4C). These results suggest that Foxc2 is an important factor in definitive hematopoietic development.

Foxc2−/− mouse embryos show defective definitive hematopoiesis. (A) Representative AGM sections of E10.5 Foxc2−/− mouse embryos and wild-type littermates with anti-Runx1 antibody staining are shown (left panel). The dorsal aorta region is shown. Quantification of Runx1-positive cells are shown on the right (3 sections per embryo; Foxc2+/+, n = 4; Foxc2−/−, n = 5; Volocity version 5.1.0, Improvision Ltd.). (B) Peripheral blood smears of a representative E13.5 Foxc2−/− embryo and a wild-type littermate are shown on the left, and the percentages of primitive, nucleated erythroblast and definitive, enucleated erythrocytes are shown on the right. (C) Real time RT-PCR of peripheral blood is shown. Gene expressions relative to wild-type controls are plotted. *P < .05 by Student t test in comparison with Foxc2+/+.

Foxc2−/− mouse embryos show defective definitive hematopoiesis. (A) Representative AGM sections of E10.5 Foxc2−/− mouse embryos and wild-type littermates with anti-Runx1 antibody staining are shown (left panel). The dorsal aorta region is shown. Quantification of Runx1-positive cells are shown on the right (3 sections per embryo; Foxc2+/+, n = 4; Foxc2−/−, n = 5; Volocity version 5.1.0, Improvision Ltd.). (B) Peripheral blood smears of a representative E13.5 Foxc2−/− embryo and a wild-type littermate are shown on the left, and the percentages of primitive, nucleated erythroblast and definitive, enucleated erythrocytes are shown on the right. (C) Real time RT-PCR of peripheral blood is shown. Gene expressions relative to wild-type controls are plotted. *P < .05 by Student t test in comparison with Foxc2+/+.

Defective definitive hematopoiesis in foxc1a/b morphant zebrafish

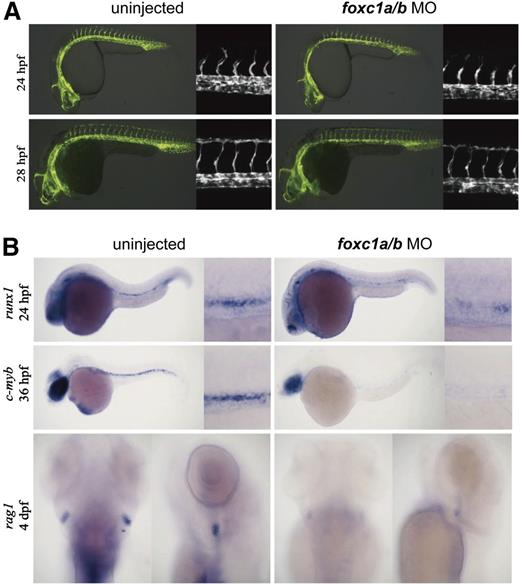

To confirm the involvement of Foxc2 in definitive hematopoiesis, we further investigated foxc1a and foxc1b, the Foxc2 orthologs in zebrafish. In zebrafish embryos, foxc1a expression was detected in both artery and vein, whereas foxc1b expression was detected in artery at 24 hours postfertilization (hpf). At 36 hpf, foxc1a and foxc1b are expressed in both the artery and vein (data not shown). The foxc1a and foxc1b morpholinos were injected into 1-cell–stage fertilized eggs. Although injection of high doses of foxc1a and foxc1b morpholinos results in defective intersomitic vessel sprouts and axial vessel formation, low-dose knockdown did not significantly affect artery or vein development.20 We confirmed that low-dose knockdown had little effect on the vascular development by injecting foxc1a and foxc1b morpholinos into fertilized eggs of transgenic (Tg) (flk1:GFP) zebrafish (Figure 5A). Low-dose knockdown of foxc1a and foxc1b in wild-type zebrafish embryos did not significantly alter the artery (ephB2a, notch3, and deltaC) or vein (ephB4a) marker expression (supplemental Figure 6). In zebrafish embryos, runx1 and c-myb mark hemogenic endothelial cells where definitive hematopoiesis originates.44 When foxc1a and foxc1b morpholinos were injected into fertilized eggs of wild-type zebrafish, runx1 staining (24 hpf) and c-myb staining (36 hpf) in arteries significantly decreased (Figure 5B). In addition, at 4 dpf, foxc1a/b morphant zebrafish showed the decrease of rag1 staining, which is a definitive hematopoiesis marker, in thymi (Figure 5B). These results suggest that Foxc2 and its orthologs are required for the development of hemogenic endothelium and definitive hematopoiesis.

foxc1a and foxc1b are required for definitive hematopoiesis in zebrafish. (A) Low-dose foxc1a/b (4/4 ng) morpholinos were injected into fertilized eggs of Tg(flk1:GFP) zebrafish. Fluorescence images of uninjected control and injected zebrafish are shown; (flk1:GFP) at 24 hpf, 66/75 intact; (flk1:GFP) at 28 hpf, 49/54 intact. (B) Low-dose foxc1a/b (4/4 ng) morpholinos were injected into fertilized eggs of wild-type zebrafish. In situ hybridization images with runx1, c-myb, and rag1 probes at indicated time points are shown. runx1, 17/35 decreased; c-myb, 11/26 decreased; rag1, 17/28 decreased.

foxc1a and foxc1b are required for definitive hematopoiesis in zebrafish. (A) Low-dose foxc1a/b (4/4 ng) morpholinos were injected into fertilized eggs of Tg(flk1:GFP) zebrafish. Fluorescence images of uninjected control and injected zebrafish are shown; (flk1:GFP) at 24 hpf, 66/75 intact; (flk1:GFP) at 28 hpf, 49/54 intact. (B) Low-dose foxc1a/b (4/4 ng) morpholinos were injected into fertilized eggs of wild-type zebrafish. In situ hybridization images with runx1, c-myb, and rag1 probes at indicated time points are shown. runx1, 17/35 decreased; c-myb, 11/26 decreased; rag1, 17/28 decreased.

Promotion of hemogenic endothelial cells with Foxc2 induction

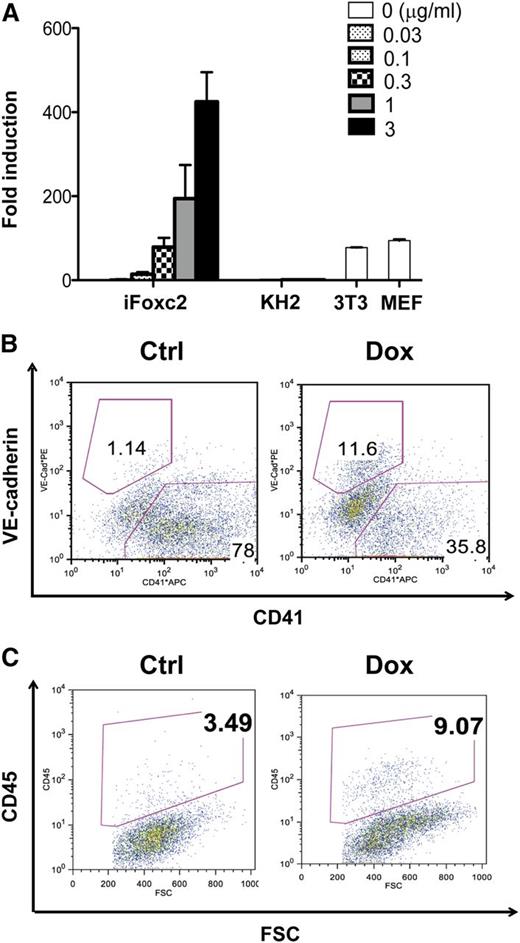

To investigate the effect of Foxc2 signaling on the specification of hemogenic endothelial cells, we generated a Dox-inducible iFoxc2 embryonic stem cell lines using the flippase recognition target-mediated targeting in KH2 ESCs.23 Foxc2 induction after 48 hours of Dox treatment was confirmed by real-time RT-PCR and immunoblotting in comparison with KH2 ESCs, 3T3 cells, and MEFs (Figure 6A, data not shown). Similar to ICN1 induction, Foxc2 induction from days 3 to 5 during EB differentiation increased the VE SP population when day 6 EBs were subjected to flow cytometric analysis (Figure 6B). When the same number of VE SP cells was sorted and subjected to subsequent HE culture, cells that had experienced Foxc2 induction during EB differentiation showed increased CD45+ cell generation, which is consistent with the effects of ICN1 induction, whereas the noninduced control cells showed no change (Figure 6C). Differences in the basal frequency of the VE-cadherin+ population in the iICN, Rosa-GFP, and iFoxc2 cell lines could in part be because of the leaky expression of the transgene or the different cellular background.45 The absolute numbers of CD45+ cells from VE SP cells with Foxc2 induction are summarized in supplemental Table 1 (160% increase with Foxc2 induction). These results suggest that Foxc2 induction promotes the hematopoietic specification of hemogenic endothelial cells during EB differentiation.

Foxc2 induction during EB differentiation increases VE-cadherin+CD41− population and enhances CD45+ cell generation from VE-cadherin+CD41− cells. (A) Real-time RT-PCR analysis for Foxc2 expression in iFoxc2 cells 48 hours after Dox induction in comparison with KH2, 3T3, and MEF cells is shown. (B) Flow cytometric analysis of day 6 iFoxc2 EBs with or without Dox induction (0.5 μg/mL) from days 3 to 5 is shown. (C) VE-cadherin+CD41− cells were sorted from day 6 iFoxc2 EBs with or without Dox induction (0.5 μg/mL) from days 3 to 5, and the same number of VE-cadherin+CD41− cells was subjected to HE culture. Flow cytometric analysis of day 4 HE culture is shown. Foxc2 was not induced in HE culture. The absolute numbers of CD45+ cells are summarized in supplemental Table 1.

Foxc2 induction during EB differentiation increases VE-cadherin+CD41− population and enhances CD45+ cell generation from VE-cadherin+CD41− cells. (A) Real-time RT-PCR analysis for Foxc2 expression in iFoxc2 cells 48 hours after Dox induction in comparison with KH2, 3T3, and MEF cells is shown. (B) Flow cytometric analysis of day 6 iFoxc2 EBs with or without Dox induction (0.5 μg/mL) from days 3 to 5 is shown. (C) VE-cadherin+CD41− cells were sorted from day 6 iFoxc2 EBs with or without Dox induction (0.5 μg/mL) from days 3 to 5, and the same number of VE-cadherin+CD41− cells was subjected to HE culture. Flow cytometric analysis of day 4 HE culture is shown. Foxc2 was not induced in HE culture. The absolute numbers of CD45+ cells are summarized in supplemental Table 1.

Foxc2 acts downstream of Notch in hemogenic endothelium

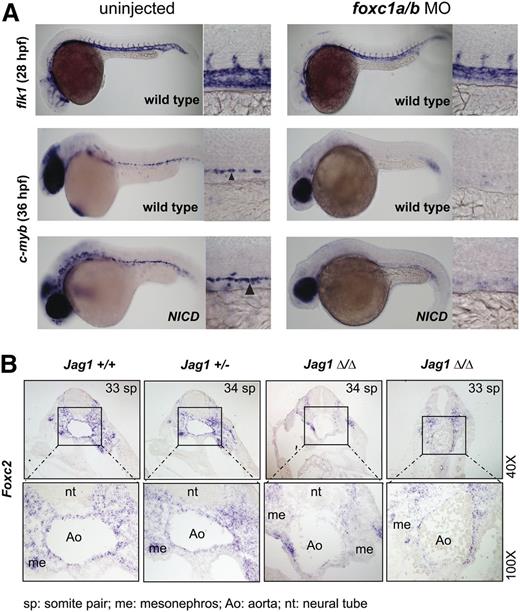

To further investigate the relationship between Notch signaling and Foxc2 in specification of hemogenic endothelium, we analyzed zebrafish embryos following Notch and foxc1a/b pathway perturbation. Prior studies showed that constitutive Notch activation using a heat-inducible bitransgenic system resulted in expansion of c-myb+ definitive hematopoietic progenitors.44 To test whether foxc1a/b are required to mediate this Notch gain-of-function phenotype, we injected low-dose foxc1a/b morpholinos into Tg(hsp70:gal4); Tg(uas:NICD) embryos and performed heat induction as previously described. The foxc1a/b morphants showed relatively intact vascular development and significant decrease of c-myb expression at 36 hpf in wild-type embryos as shown previously. Heat-induction of NICD expanded c-myb expression in uninjected controls but did not restore c-myb expression in foxc1a/b morphants, which suggests that foxc1a/b activity is necessary to mediate Notch signaling (Figure 7A; supplemental Figure 7A). However, we were unable to robustly rescue the mind bomb (mib) mutant zebrafish, which has defective Notch signaling and hemogenic endothelium, by injecting Foxc2 messenger RNA (supplemental Figure 8), indicating that Foxc2 is not the sole mediator of Notch signaling. Taken together, the results in zebrafish suggest that foxc1a/b are necessary but not sufficient to act downstream of Notch signaling for hemogenic endothelial specification.

Foxc2 is a downstream mediator of Notch signaling in AGM hematopoiesis. (A) Low-dose foxc1a/b morpholinos (4/4 ng) were injected into fertilized zebrafish eggs from a wild-type cross or from a cross of hsp70:gal4 and uas:NICD. Heat shock was performed on embryos from hsp70:gal4 and uas:NICD cross between 8 and 12 somite stages at 37°C for 30 minutes to induce NICD expression. Embryos were incubated at 28°C. Wild-type crosses were harvested at 28 hpf and 36 hpf, and hsp70:gal4 and uas:NICD crosses were harvested at 36 hpf. In situ hybridization with flk1 (wild-type at 28 hpf) or c-myb (wild-type and NICD at 36 hpf) is shown. Arrowhead indicates positive c-myb staining. Morpholino injection decreased (7 partial + 23 complete/30) c-myb expression, and NICD induction did not rescue the decrease (1 partial + 6 complete/7). (B) Jagged1 null mouse embryos and littermates (E10.5) were subjected to in situ hybridization with Foxc2 probe. Transverse sections of dorsal aorta in the AGM region are shown in a dorsal to ventral orientation. Two representative Jagged1 null embryos are shown (n = 4).

Foxc2 is a downstream mediator of Notch signaling in AGM hematopoiesis. (A) Low-dose foxc1a/b morpholinos (4/4 ng) were injected into fertilized zebrafish eggs from a wild-type cross or from a cross of hsp70:gal4 and uas:NICD. Heat shock was performed on embryos from hsp70:gal4 and uas:NICD cross between 8 and 12 somite stages at 37°C for 30 minutes to induce NICD expression. Embryos were incubated at 28°C. Wild-type crosses were harvested at 28 hpf and 36 hpf, and hsp70:gal4 and uas:NICD crosses were harvested at 36 hpf. In situ hybridization with flk1 (wild-type at 28 hpf) or c-myb (wild-type and NICD at 36 hpf) is shown. Arrowhead indicates positive c-myb staining. Morpholino injection decreased (7 partial + 23 complete/30) c-myb expression, and NICD induction did not rescue the decrease (1 partial + 6 complete/7). (B) Jagged1 null mouse embryos and littermates (E10.5) were subjected to in situ hybridization with Foxc2 probe. Transverse sections of dorsal aorta in the AGM region are shown in a dorsal to ventral orientation. Two representative Jagged1 null embryos are shown (n = 4).

To confirm that Foxc2 functions as a downstream effector of Notch signaling, we analyzed mouse embryos deficient in the Notch ligand Jagged1. These embryos have impaired hematopoiesis in the AGM but normal artery identity.46 Jagged1 null embryos showed decreased Runx1 expression, as previously reported (supplemental Figure 7B). Foxc2 expression was detected along the endothelium in the AGM of wild-type and heterozygous littermates, whereas Jagged1 null embryos showed significant decrease of Foxc2 expression in the endothelium and the ventral mesenchyme in the AGM (Figure 7B). Given that the ventral side of the AGM is hemogenic and originates from the lateral plate mesoderm, the decrease of Foxc2 expression in the ventral side of the AGM of Jagged1 null embryos correlates with the observation in zebrafish in which Foxc2 orthologs function downstream of Notch for specification of hemogenic endothelium. Taken together, the results from differentiating EBs and embryos of mouse and zebrafish suggest that Foxc2 plays a key role in definitive hematopoiesis by regulating hemogenic endothelial cell development downstream of Notch signaling.

Discussion

The emergence of definitive hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells from hemogenic endothelium has been well documented in the developing murine embryo, but little is known about the molecular pathways that mediate this critical developmental specification.5,6,47,48 Our study shows that Notch1 induction increases the VE-cadherin+ hemogenic endothelial population in differentiating murine ESCs, and that Foxc2 is a downstream mediator of Notch signaling in definitive hematopoiesis in both zebrafish and mouse embryos.

Definitive hematopoietic precursors first appear in the aorta and are also detected in vitelline and umbilical arteries, but not in veins, which suggests that HSC generation is associated with artery specification.7 Notch and Foxc genes are known to play critical roles in determining arterial cell fate during embryo development.17 In this study, we demonstrated that induction of Notch1 signaling increased the hemogenic endothelial population within differentiating cultures of ESCs and also enhanced their hematopoietic potential. We then identified the Foxc2 transcription factor as a chief candidate for mediating Notch1 signaling, as it showed the highest increase after Notch1 induction in a similarity search with Gata3, a master hematopoietic regulatory gene for the hemogenic endothelial population. Induction of Notch signaling has been shown to enhance development of c-myb-positive hematopoietic progenitors in the zebrafish.44 In this study, we show that in the setting of Notch induction, morpholino knockdown of the zebrafish orthologs foxc1a and foxc1b markedly reduced detection of c-myb-positive hematopoietic progenitors without disrupting vascular integrity, thereby implicating FoxC genes as downstream targets in the Notch pathway. Moreover, mouse embryos deficient in the Notch ligand Jagged1 showed markedly reduced levels of Foxc2 staining in the aortic endothelium, and Foxc2 null embryos showed reduced levels of Runx1-positive hematopoietic elements, thereby demonstrating that Notch signaling promotes hematopoietic specification through the Foxc2 transcription factor.

HSCs can be derived from ESCs (ESC-HSCs) by ectopic expression of HoxB4 and Cdx4, but ESC-HSCs do not faithfully recapitulate adult HSCs in their function or surface phenotype.2 According to transcriptome analysis of hematopoietic stem and progenitors from developing embryos, differentiating ESCs, and adult mice, ESC-HSCs cluster most closely with fetal liver and adult bone marrow HSCs but reveal the absence of a transcriptional response to Notch signaling.1 Weighted Gene Coexpression Network Analysis clustering algorithm assigns Foxc2 to a “HSC-specifying” module (module 19) (http://hsc.hms.harvard.edu). A recent report in which hematoendothelial cells were generated from human ESCs showed that Foxc2 was enriched in hemogenic endothelial cells compared with nonhemogenic endothelial cells.49 In addition, Etv2, which cooperates with Foxc2 in regulating endothelial genes, was shown to cooperate with Gata2, a well-known Notch1 downstream target, to regulate endothelial and hematopoietic lineage development.20,50 Thus, the Notch-Foxc2 axis may be important in the emergence of not only definitive hematopoietic progenitors but also definitive HSCs. However, when the VE-cadherin+ population of day 6 EBs with Notch1 induction was transplanted into mouse neonates, no meaningful long-term engraftment was detected (data not shown). Even with enhanced hematopoietic potential following Notch1 induction, the day 6 EB-derived VE-cadherin+ population needs additional developmental maturation to achieve engraftment in the mouse. Further investigation of Notch1 signaling and Foxc2 in hematopoietic development may help identify essential differences between ESC-HSCs and adult HSCs.

Hemogenic sites in early embryo development overlap with vasculogenic sites, including the yolk sac, allantois, vitelline, and umbilical vessels, and the emergence of definitive hematopoiesis appears to correlate with angiogenic remodeling of the primitive vascular plexus.51-55 Inside the embryo, vasculogenic sites include the aorta, lung, spleen, and pancreas, but among them, only the aorta is known to have hemogenic activity. It will be of high interest to analyze the molecular and cellular mechanisms of this anatomic distinction and to look further into the transient character of hemogenic endothelial cells. Clonogenic analysis of hemogenic endothelial cells in the culture condition that supports outgrowth of endothelial and hematopoietic cells will facilitate more accurate estimation of hemogenic endothelial cell frequency.56 In the era of reprogramming, it may be possible to convert nonhemogenic endothelial cells to hemogenic endothelial cells via ectopic expression of transcription factors like Foxc2, which may give us a new strategy for generating autologous HSCs.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Jonghwan Kim (Stem Cell Program and Division of Hematology/Oncology, Children's Hospital Boston and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Harvard Medical School for guiding us in analyzing microarray data, Elizabeth Paik and Michelle Lin (Stem Cell Program and Division of Hematology/Oncology, Children's Hospital Boston and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Harvard Medical School) for sharing their zebrafish and experimental protocols, and Tom Gridley (Jackson Labs, Bar Harbor, ME) for providing the Jagged1 mutant mice.

This work was supported by grants from the Boston Children's Hospital (PLE1009-0111 and SAF2010-15450); the National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Progenitor Cell Biology Consortium (grant UO1-HL100001); the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (grant R24DK092760); and the Doris Duke Medical Foundation. G.Q.D. is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and the Manton Center for Orphan Disease Research.

Authorship

Contribution: I.H.J. and Y.-F.L. designed the research and performed experiments; L.Z., P.L.W., S.M.D., N.A., J.G., M.L., P.G.K., and E.K.D. performed experiments; J.H.K., T.K., T.M.S., L.I.Z., A.B., C.E.B., and G.Q.D. provided resources and comments; and I.J. and G.Q.D. wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: George Q. Daley, Stem Cell Program and Division of Hematology/Oncology, Children's Hospital Boston and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115; e-mail: george.daley@childrens.harvard.edu; and Caroline E. Burns, Cardiovascular Research Center, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Charlestown, MA 02129; e-mail: cburns6@partners.org.

References

Author notes

I.H.J. and Y.-F.L. contributed equally to this study.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal