In this issue of Blood, Rossi et al show that certain predictive biomarkers are able to identify a subgroup of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) who have an exceptionally good outcome following front-line therapy with the combination of fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab (FCR).1

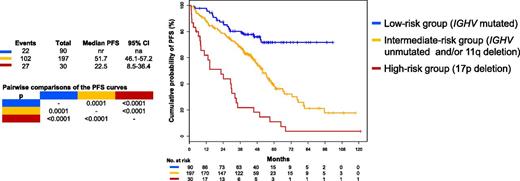

Estimates of PFS for a group of 404 patients with CLL divided into 3 risk groups: high risk (in red), 17pdel; intermediate risk (in yellow), unmutated IGHV and/or 11qdel but not 17pdel; low risk (in blue), mutated IGHV and no 11q or 17pdel. See Figure 1A in the article by Rossi et al that begins on page 1921.

Estimates of PFS for a group of 404 patients with CLL divided into 3 risk groups: high risk (in red), 17pdel; intermediate risk (in yellow), unmutated IGHV and/or 11qdel but not 17pdel; low risk (in blue), mutated IGHV and no 11q or 17pdel. See Figure 1A in the article by Rossi et al that begins on page 1921.

Fifty years ago, there was only one therapy, chlorambucil, that was commonly used to treat CLL. The treatment landscape has undergone dramatic change since then, particularly in the last 3 years, and there is now a bewildering array of available agents, both chemotherapy and targeted nonchemotherapy drugs, used alone and in various combinations. A number of retrospective studies and prospective clinical trials over the last 15 years have sought to determine clinical and biological parameters that can identify those patients who will respond well to a particular treatment and conversely those patients who will have a worse outcome. There has been some success in this endeavor to “personalize” the approach to treatment. Döhner et al2 first described the hierarchical model of cytogenetic aberrations highlighting the poor outcome for patients with deletions of 17p and 11q. Hamblin et al3 demonstrated the difference in survival between patients with mutated vs unmutated immunoglobulin heavy chain genes (IGHV). These parameters have now been studied prospectively in several clinical trials, confirming the predictive value of these tests, which are readily available for patients who are embarking on their first treatment of CLL. Indeed, the strong prediction for poor response to conventional treatment in those patients whose CLL cells harbor abnormal TP53 (deletion or mutation) on chromosome 17 has led to the introduction of novel tailored approaches for these individuals, including early stem cell transplantation. There also continue to be concerns related to the immediate and delayed toxicities associated with the use of conventional myelo-suppressive and DNA-damaging chemotherapy. The advent of newer targeted nonchemotherapy drugs is attractive in this regard and may have application across a much wider range of CLL patients, including those with adverse cytogenetics and those not fit enough to receive more intensive chemotherapy. It is therefore of paramount importance that robust data are available to aid decision-making related to the choice of initial therapy for patients with CLL.

Since the initial reports from the MD Anderson Cancer Center on the efficacy of FCR,4 this has been adopted internationally as the “gold standard” treatment of younger fit patients with CLL. With extended follow-up from this initial study, together with data from the German CLL study group trial (CLL8) of FCR vs FC, it has become clear that a subset of patients can be identified who are likely to have an exceptionally good outcome.5-7 This subgroup is defined by the presence of mutated IGHV genes together with a lack of adverse cytogenetic features, notably deletions of 17p and 11q.

Rossi et al retrospectively studied a large cohort of 404 Italian patients who received front-line treatment with FCR and had biological parameters assessed at baseline.1 They confirm the finding that the 28% of patients in this cohort with mutated IGHV and no 17p or 11q deletions have very prolonged progression-free survival (PFS; median not reached, 71% at 5 years) and overall survival (OS; 91% at 5 years). As with the other studies from MD Anderson Cancer Center and CLL8, the risk of relapse appears to decline significantly after 4 years, with a plateau possibly emerging on the curve (see figure). A small number of the patients were tested for minimal residual disease (MRD) in peripheral blood after more than 6 years in remission and found to be MRD negative. Importantly, they show that this group of patients has a survival similar to that of an age-matched general Italian population without CLL, suggesting that neither the CLL itself nor the treatment received affected survival in this good-risk group of patients. However, it is important to note that in the study by Rossi et al, the follow-up remains relatively short, with little data beyond 5 years. More extended follow-up of this patient cohort is therefore needed to confirm the findings.

Published data on front-line therapy with novel agents such as ibrutinib and idelalisib are still limited to very small numbers of patients with relatively short follow-up.8 Despite the extraordinarily good results (96% PFS at 30 months for front-line ibrutinib), there remain issues around duration of and compliance with treatment, short- and long-term tolerability, emergence of resistance, and cost. It would be naïve to imagine that all patients with CLL will benefit equally from novel therapies in the long term without any complications or progression. It is therefore crucial that the necessary clinical trials are undertaken to establish exactly which patient is likely to benefit most from the different therapeutic approaches to allow selection of a tailored patient-specific treatment plan. Unlike the trials in relapsed/refractory CLL, these studies will take time to conduct and to reach end points such as PFS and OS. It will thus be many years before there are answers to these important questions. In the meantime, there is now evidence from 3 large patient cohorts including more than 1000 patients treated with first-line FCR, some with long follow-up, that those patients with mutated IGHV, no adverse cytogenetics, and of the right age and fitness to receive combination chemo-immunotherapy can expect to achieve very durable remissions and near-normal survival. The small number of patients who fall into this category may thus be able to return to normal life and work after a single 6-month, cost-effective treatment without the need for ongoing medication and with less uncertainty about their longer-term prospects.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests.