Key Points

Overall, no benefit of granulocyte transfusion therapy was observed, but the power of the study was reduced due to low accrual.

Post hoc secondary analysis suggested that patients receiving higher doses tended to have better outcomes than those receiving lower ones.

Abstract

High-dose granulocyte transfusion therapy has been available for 20 years, yet its clinical efficacy has never been conclusively demonstrated. We report here the results of RING (Resolving Infection in Neutropenia with Granulocytes), a multicenter randomized controlled trial designed to address this question. Eligible subjects were those with neutropenia (absolute neutrophil count <500/μL) and proven/probable/presumed infection. Subjects were randomized to receive either (1) standard antimicrobial therapy or (2) standard antimicrobial therapy plus daily granulocyte transfusions from donors stimulated with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) and dexamethasone. The primary end point was a composite of survival plus microbial response, at 42 days after randomization. Microbial response was determined by a blinded adjudication panel. Fifty-six subjects were randomized to the granulocyte arm and 58 to the control arm. Transfused subjects received a median of 5 transfusions. Mean transfusion dose was 54.9 × 109 granulocytes. Overall success rates were 42% and 43% for the granulocyte and control groups, respectively (P > .99), and 49% and 41%, respectively, for subjects who received their assigned treatments (P = .64). Success rates for granulocyte and control arms did not differ within any infection type. In a post hoc analysis, subjects who received an average dose per transfusion of ≥0.6 × 109 granulocytes per kilogram tended to have better outcomes than those receiving a lower dose. In conclusion, there was no overall effect of granulocyte transfusion on the primary outcome, but because enrollment was half that planned, power to detect a true beneficial effect was low. RING was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as #NCT00627393.

Introduction

Bacterial and fungal infections continue to be a major clinical problem in patients with prolonged severe neutropenia.1-8 Granulocyte transfusions are a logical therapeutic approach to this problem and have been used for over 50 years. The early experience used various collection techniques resulting in widely disparate cell doses and cells of varying functional capabilities. Controlled trials in the 1970s and 1980s provided mixed results but, in aggregate, indicated that the therapy was modestly efficacious.9 In spite of an initial period of enthusiasm, granulocyte transfusion therapy then fell out of favor and was rarely used. There were several reasons for this. First, improvements in antimicrobial therapy reduced the perceived need. Second, there were reports of adverse effects, particularly pulmonary events and transmission of cytomegalovirus (CMV).10-14 Finally, many physicians were not convinced that their patients experienced meaningful clinical improvements after receiving granulocyte transfusions, which has been attributed, at least in part, to the likelihood that the doses of granulocytes administered, typically 20 to 30 × 109, were inadequate. Evidence for the importance of dose came from early uncontrolled trials in humans,15,16 from retrospective analysis of the early controlled trials,9,17,18 from animal studies using sepsis and meningitis models,19,20 and from human kinetic studies showing that normal daily neutrophil production in the uninfected subject was ∼1 × 109/kg.21 Renewed interest in this therapy arose with the introduction of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) and the possibility of greatly increasing the dose of granulocytes transfused by administering G-CSF to healthy granulocyte donors. Studies over the last 20 years have shown that 3 to 4 times as many granulocytes can be collected from donors stimulated with G-CSF (with or without the addition of corticosteroids),22-34 that these collected cells circulate in neutropenic recipients,23,26,28 and that the cells appear to function normally as judged by both in vitro and in vivo testing.28,35,36

The evidence for clinical efficacy of high-dose granulocyte transfusion therapy has been elusive. Over 25 descriptive studies have been reported, but no clear answer has resulted from these uncontrolled trials.23,27,28,30,31,33,34,37,38 In a retrospective case-controlled study, Hübel et al examined the effect of high-dose granulocyte transfusions on the course of infection and on survival in patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and found no difference between the transfused and untransfused groups.39 Safdar et al, in another case-controlled study in patients with candidemia, showed no effect of granulocyte transfusion on survival but concluded that the transfusions were likely efficacious because the transfused group was sicker.32 The only published randomized controlled trial showed no effect of granulocyte transfusions on 28-day survival, but there were several difficulties with the trial, pointed out by the authors, that prevented the study from being definitive. These included a low accrual (45% of desired), a significant amount of crossover between the arms, a very high success rate in the control arm suggesting that the sickest patients were not enrolled, and the fact that the transfused patients received very few transfusions (<3 for 44% of patients).40

We report here the results of the RING Study (Resolving Infection in Neutropenia with Granulocytes), a recently completed randomized controlled clinical trial conducted as part of the NHLBI Transfusion Medicine/Hemostasis (TMH) Clinical Trials Network, undertaken to evaluate the efficacy of this therapy.

Methods

Study subjects

Subjects were recruited from 14 Transfusion Medicine/Hemostasis Clinical Trials Network and non-Network sites. At the onset of the study, eligible patients were those of any age with (1) neutropenia, defined as absolute neutrophil count (ANC) <500 cells per µL, due to aggressive chemotherapy or hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and (2) proven or probable bacterial or fungal infection. Criteria for the categorization of fungal infections were that of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Invasive Fungal Infections Cooperative Group and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycosis Study Group (EORTC/MSG) Consensus Group.41 These criteria, as well as those for bacterial infection, are provided in supplemental Tables 1-3 (see supplemental Data available at the Blood Web site). Subjects were to be randomized within 24 hours of eligibility.

After 31 months of enrollment, the eligibility criteria were liberalized to include patients with presumed infection (identical host and clinical criteria, but identification of organism not necessary), and to include patients with neutropenia due to underlying marrow disease (eg, aplastic anemia). The allowed time to randomization was extended to 1 week from first meeting eligibility criteria.

Subjects were excluded from the study if they were unlikely to survive 5 days, if there was evidence that the patient was unlikely to be neutropenic for at least 5 days, or if they had previously enrolled in this study. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects and donors. The protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of all the participating clinical sites and granulocyte collection facilities, and by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI)-appointed Data Safety Monitoring Committee, which also monitored the trial throughout the study.

Study design

This was a randomized 2-arm, open-label, phase 3 study. Subjects were randomized with equal allocation to receive either (1) standard antimicrobial therapy or (2) standard antimicrobial therapy plus daily granulocyte transfusions from normal donors stimulated with subcutaneous G-CSF (480 µg) and oral dexamethasone (8 mg). Randomization was performed using randomly permuted blocks within strata. Subjects were stratified according to risk status (high risk = stem cell transplant or relapsed leukemia; low risk = other) and type of infection (invasive mold versus other), and allocation was also balanced within each clinical site using dynamic balancing.42 Standard antimicrobial therapy was determined by the individual clinical sites, although recommended therapies for specific types of infections were provided in the protocol. For subjects in the transfusion arm, daily transfusions were continued for up to 42 days but were discontinued if 1 or more of the following occurred: (1) neutrophil recovery, (2) resolution or improvement of the underlying infection (at the discretion of the patient’s physician) provided the subject received at least 5 granulocyte transfusions over at least a 7-day period, or (3) life-threatening toxicity. Neutrophil recovery was defined as the first of 2 consecutive days with ANC >1000 cells per µL without granulocyte support. For patients receiving granulocyte transfusions, transfusions were discontinued when the morning ANC exceeded 3000 cells per µL for 2 successive days. If the ANC remained above 1000 cells per µL for another 2 days, it was considered to indicate neutrophil recovery. Alternatively, if the count fell below 1000 cells per µL, granulocytes were resumed.

Information was collected on all serious adverse events, unexpected adverse events at least possibly related to granulocyte transfusion, and a list of specific events that occurred during or within 6 hours following a granulocyte transfusion.

Primary end point

The primary end point was clinical success of the treatment regimen. To be considered a success, the subject had to meet 2 criteria: survival for 42 days after randomization and clinical response of the study-qualifying infection, also evaluated at 42 days. Response for bloodstream infections was defined as a negative blood culture. For invasive bacterial or fungal infections, response was defined as resolution or improvement of clinical evidence of infection. A stable infection was considered to be a failure. Evaluation of response was performed by an independent adjudication panel blinded to the subject’s treatment arm. For all subjects, the panel confirmed the subject’s eligibility for the study and evaluated the appropriateness of the antimicrobial therapy. For subjects alive at day 42, the panel also determined whether or not the subject’s infection resolved or improved. These decisions were based on clinical summaries, laboratory results, cultures, reports of imaging studies, and data from the standard case report forms. The panel was composed of 3 infectious disease specialists and 1 radiologist, none of whom were affiliated with any of the participating clinical sites.

Secondary objectives

Additional objectives were to document (1) primary outcome within each infection subgroup, (2) the frequency and nature of granulocyte transfusion reactions, (3) the overall incidence of adverse effects, and (4) mortality through 3 months.

Granulocyte procurement/transfusion

Granulocyte concentrates were collected by the participating clinical sites or by their blood collection institutions. Granulocyte donors were either volunteer community donors or friends or relatives of the patient. All donors met standard blood donor criteria established by the local blood center, the AABB, and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Donors were not selected on the basis of HLA or granulocyte compatibility. If the patient was CMV seronegative, only CMV-seronegative donors were selected.

Donors received 480 µg of G-CSF subcutaneously and 8 mg of dexamethasone orally 8 to 16 hours prior to donation. Donation was by a standard continuous flow apheresis procedure, processing 7 to 10 L of blood, using hydroxyethyl starch as a sedimenting agent. The goal for the collection centers was to achieve a dose of at least 40 × 109 granulocytes per transfusion, equivalent to ∼0.6 × 109 cells per kilogram for an average 70-kg patient. The cell dose was proportionally reduced for patients weighing <30 kg. All granulocyte concentrates were γ/x-ray irradiated prior to transfusion. Granulocytes were transfused as soon as possible after collection, every attempt being made to transfuse within 6 hours. Transfusions were separated from the administration of amphotericin B by at least 2 hours. ANC was determined prior to and within 2.5 hours after each transfusion. Vital signs and oxygen saturations were measured before, during, and after each transfusion.

Study measurements

Vital signs were obtained daily until discharge or day 42, whichever came first. ANCs were obtained daily until engraftment, hospital discharge, or day 42, whichever came first, and then weekly after engraftment until discharge or day 42. Serum samples were obtained at baseline and again at 2 and 6 weeks after randomization for central laboratory leukocyte antibody studies (which will be the subject of a future report). For patients with bloodstream infections, daily blood cultures were obtained until 2 consecutive blood cultures were negative, and again at 42 days. For invasive infections, clinical and radiographic evaluations were performed as clinically indicated and again at 42 days. For subjects who withdrew from the study before day 90, public records were searched to determine whether the subject was alive by day 90, and, if not, to determine the date of death.

Statistical considerations

The target sample size of 118 subjects per arm would provide 80% power to detect a treatment difference if the true success rate with antimicrobial therapy alone was 50% (based on studies by Hübel et al39 and Nichols et al38 ), and the true success rate with the granulocyte treatment arm was 70%.

Unless otherwise specified, all analyses were carried out using a modified intention-to-treat principle (MITT; excluding subjects for whom a primary outcome could not be determined due to study withdrawal or inadequate information for adjudication of response) with subjects analyzed in the treatment group to which they were randomly assigned, whether or not they adhered to the assigned treatment, and whether or not the adjudication panel confirmed that they met eligibility requirements and received appropriate antimicrobial therapy. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize baseline characteristics of subjects in the 2 treatment arms. The proportion of subjects who met the criteria for success for the primary end point was compared using the Fisher exact test following the MITT principle. A secondary per-protocol (PP) analysis also excluded patients who did not adhere to the assigned treatment. The analyses were repeated, adjusting for the stratification variable and selected baseline characteristics using exact logistic regression, using both MITT and PP approaches. The association analyses between dose group and primary outcome were performed using exact logistic regression.

Serious adverse events, granulocyte transfusion characteristics, and evaluation of granulocyte yield were summarized using descriptive statistics. Analyses of the primary end point in specific subsets of patients were performed using the Fisher exact test. Survival through 3 months was compared between treatments using Kaplan-Meier curves and log-rank test statistics. The association between granulocyte transfusion dose and posttransfusion ANC increment was tested with a general linear model accounting for within-subject correlation. The effect of granulocyte transfusion dose on the presence of transfusion-related events was analyzed with a logistic regression model controlling for within-patient correlation. An exact logistic regression was performed to test the association between average posttransfusion ANC and primary outcome.

Results

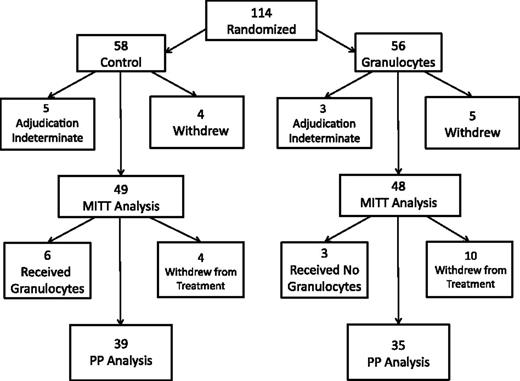

One hundred fourteen subjects were enrolled and randomized, 58 to the control arm and 56 to the granulocyte transfusion arm (Figure 1). The study was terminated short of the desired enrollment because of time limits on the funding of the TMH Clinical Trials Network. Nine subjects withdrew from the study before day 42, and the primary end point could not be determined (adjudication indeterminate) for another 8 subjects, leaving 97 subjects evaluable for the MITT analysis of the primary outcome. The PP analysis was limited to the 74 subjects who adhered to the assigned treatment, excluding an additional 14 subjects who withdrew from the assigned treatment, 6 subjects in the control arm who received non-G-CSF–stimulated granulocytes off protocol, and 3 subjects in the granulocyte arm who did not withdraw but never received granulocytes. Approximately 70% of subjects who withdrew from either the study or the assigned treatment did so because of a decision to convert to hospice/comfort care only.

Flow diagram of the study. A total of 114 patients were randomized, 56 to the granulocytes group and 58 to the control group. Nine subjects withdrew from the study, and an additional 14 subjects withdrew from treatment.

Flow diagram of the study. A total of 114 patients were randomized, 56 to the granulocytes group and 58 to the control group. Nine subjects withdrew from the study, and an additional 14 subjects withdrew from treatment.

The baseline characteristics of the 97 patients subject to MITT analysis are indicated in Table 1. Except for a slightly higher age in the granulocyte group and a slightly higher respiratory rate in the control group, subjects in both arms were well matched in terms of demographics, degree and cause of neutropenia, underlying disorders, types of infections and responsible organisms, and relevant signs and symptoms. In particular, there was no significant difference in indicators of disease severity such as the Zubrod scores43 or the fraction of subjects on ventilators.

Baseline characteristics for modified intention-to-treat subjects (N = 97)

| . | Treatment arm . | P* . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control, n = 49 . | Granulocytes, n = 48 . | ||

| Age, y | 46.9 + 20.2 | 54.9 + 17.1 | .04 |

| <18, n (%) | 6 (12) | 4 (8) | .24 |

| 18-64, n (%) | 33 (67) | 27 (56) | |

| >65, n (%) | 10 (20) | 17 (35) | |

| Male sex, n (%) | 27 (55) | 28 (58) | .84 |

| Race, n (%) | .18 | ||

| White | 31(63) | 37 (77) | |

| Asian | 4 (8) | 1 (2) | |

| Black/African American | 1 (2) | 3 (6) | |

| Other/unknown | 13 (27) | 7 (15) | |

| ANC at randomization, cells/μL | 43 ± 88 | 59 ± 100 | .38 |

| Cause of neutropenia, n (%) | .83 | ||

| HSC transplantation | 8 (16) | 8 (17) | |

| Chemotherapy | 36 (73) | 37 (77) | |

| Other | 5 (10) | 3 (6) | |

| Underlying disorder, n (%) | .73 | ||

| Acute lymphocytic leukemia | 6 (12) | 6 (13) | |

| Acute nonlymphocytic leukemia | 31 (63) | 32 (67) | |

| Chronic myelogenous leukemia | 2 (4) | 0 (0) | |

| Chronic lymphocytic leukemia | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 3 (6) | 4 (8) | |

| Myelodysplasia | 1 (2) | 2 (4) | |

| Myeloma | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | |

| Aplastic anemia | 2 (4) | 0 (0) | |

| Other malignancy | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | |

| Other | 2 (4) | 3 (6) | |

| Infection at enrollment, n (%) | .48† | ||

| Proven fungal | 15 (31) | 11 (23) | |

| Bloodstream | |||

| Candida | 6 (12) | 3 (6) | |

| Zygomycetes | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | |

| Mold not specified | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | |

| Pulmonary | |||

| Aspergillus | 1 (2) | 2 (4) | |

| Zygomycetes | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | |

| Facial/sinus | |||

| Aspergillus | 0 (0) | 2 (4) | |

| Zygomycetes | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | |

| Skin/soft tissue | |||

| Aspergillus | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | |

| Fusarium | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | |

| Disseminated | |||

| Candida | 1 (2) | 2 (4) | |

| Fusarium | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | |

| Other | |||

| Aspergillus | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | |

| Mold not specified | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | |

| Probable/presumptive pulmonary fungal | 9 (18) | 11 (23) | |

| Typhlitis | 2 (4) | 5 (10) | |

| Invasive bacterial | 13 (27) | 8 (17) | |

| Bacteremia alone | 10 (20) | 13 (27) | |

| Signs/symptoms | |||

| Fever | 46 (94) | 41 (85) | .20 |

| Pulmonary Sx/signs, n (%) | 30 (61) | 30 (63) | >.99 |

| Dyspnea, n (%) | 10 (20) | 10 (21) | >.99 |

| Respiratory rate, per min | 23.4 ± 6.1 | 20.6 ± 4.6 | .03 |

| FIO2 | 0.42 ± .23 | 0.40 ± .24 | .76 |

| Arterial O2 saturation, % | 96.0 ± 3.5 | 95.4 ± 5.5 | .83 |

| Ventilator, n (%) | 10 (20) | 9 (19) | >.99 |

| Nasal/sinus Sx/signs, n (%) | 4 (8) | 9 (19) | .15 |

| CNS Sx/signs, n (%) | 11 (22) | 7 (15) | .31 |

| Skin nodules/papules, n (%) | 5 (10) | 7 (15) | .76 |

| Zubrod score,‡ >2, n (%) | 34 (69) | 36 (75) | .65 |

| . | Treatment arm . | P* . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control, n = 49 . | Granulocytes, n = 48 . | ||

| Age, y | 46.9 + 20.2 | 54.9 + 17.1 | .04 |

| <18, n (%) | 6 (12) | 4 (8) | .24 |

| 18-64, n (%) | 33 (67) | 27 (56) | |

| >65, n (%) | 10 (20) | 17 (35) | |

| Male sex, n (%) | 27 (55) | 28 (58) | .84 |

| Race, n (%) | .18 | ||

| White | 31(63) | 37 (77) | |

| Asian | 4 (8) | 1 (2) | |

| Black/African American | 1 (2) | 3 (6) | |

| Other/unknown | 13 (27) | 7 (15) | |

| ANC at randomization, cells/μL | 43 ± 88 | 59 ± 100 | .38 |

| Cause of neutropenia, n (%) | .83 | ||

| HSC transplantation | 8 (16) | 8 (17) | |

| Chemotherapy | 36 (73) | 37 (77) | |

| Other | 5 (10) | 3 (6) | |

| Underlying disorder, n (%) | .73 | ||

| Acute lymphocytic leukemia | 6 (12) | 6 (13) | |

| Acute nonlymphocytic leukemia | 31 (63) | 32 (67) | |

| Chronic myelogenous leukemia | 2 (4) | 0 (0) | |

| Chronic lymphocytic leukemia | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 3 (6) | 4 (8) | |

| Myelodysplasia | 1 (2) | 2 (4) | |

| Myeloma | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | |

| Aplastic anemia | 2 (4) | 0 (0) | |

| Other malignancy | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | |

| Other | 2 (4) | 3 (6) | |

| Infection at enrollment, n (%) | .48† | ||

| Proven fungal | 15 (31) | 11 (23) | |

| Bloodstream | |||

| Candida | 6 (12) | 3 (6) | |

| Zygomycetes | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | |

| Mold not specified | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | |

| Pulmonary | |||

| Aspergillus | 1 (2) | 2 (4) | |

| Zygomycetes | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | |

| Facial/sinus | |||

| Aspergillus | 0 (0) | 2 (4) | |

| Zygomycetes | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | |

| Skin/soft tissue | |||

| Aspergillus | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | |

| Fusarium | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | |

| Disseminated | |||

| Candida | 1 (2) | 2 (4) | |

| Fusarium | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | |

| Other | |||

| Aspergillus | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | |

| Mold not specified | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | |

| Probable/presumptive pulmonary fungal | 9 (18) | 11 (23) | |

| Typhlitis | 2 (4) | 5 (10) | |

| Invasive bacterial | 13 (27) | 8 (17) | |

| Bacteremia alone | 10 (20) | 13 (27) | |

| Signs/symptoms | |||

| Fever | 46 (94) | 41 (85) | .20 |

| Pulmonary Sx/signs, n (%) | 30 (61) | 30 (63) | >.99 |

| Dyspnea, n (%) | 10 (20) | 10 (21) | >.99 |

| Respiratory rate, per min | 23.4 ± 6.1 | 20.6 ± 4.6 | .03 |

| FIO2 | 0.42 ± .23 | 0.40 ± .24 | .76 |

| Arterial O2 saturation, % | 96.0 ± 3.5 | 95.4 ± 5.5 | .83 |

| Ventilator, n (%) | 10 (20) | 9 (19) | >.99 |

| Nasal/sinus Sx/signs, n (%) | 4 (8) | 9 (19) | .15 |

| CNS Sx/signs, n (%) | 11 (22) | 7 (15) | .31 |

| Skin nodules/papules, n (%) | 5 (10) | 7 (15) | .76 |

| Zubrod score,‡ >2, n (%) | 34 (69) | 36 (75) | .65 |

Continuous variables are displayed as mean ± standard deviation, and categorical variables are displayed as n (%).

CNS, central nervous system; HSC, hematopoietic stem cell; Sx, symptoms.

P values: Fisher exact test for categorical variables and Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables.

P value for 5 infection groups: proven fungal, probable/presumptive pulmonary fungal, typhlitis, invasive bacterial, bacteremia alone.

Zubrod score defined as: 0, asymptomatic; 1, symptomatic, fully ambulatory; 2, symptomatic, in bed <50% of the day but not bedridden; 3, symptomatic, in bed >50% of the day but not bedridden; 4, bedridden; 5, death.

Granulocyte transfusion

Fifty-one of the 56 subjects randomized to the granulocyte arm received at least 1 granulocyte transfusion. The time from eligibility to the first transfusion for these subjects was 2.3 ± 1.2 days. The median number of transfusions administered was 5 (quartiles 3, 9, range 1-20) over the course of 6 days (quartiles 4, 11). The mean time from granulocyte collection to administration was 6.8 ± 2.4 hours. The median granulocyte dose per transfusion was 54.9 × 109 (quartiles 26.1 × 109, 72.5 × 109), and 213 of the 307 transfusions with available dose information (of a total of 316 transfusions) included at least 40 × 109 granulocytes. The mean number of granulocytes administered per transfusion varied from subject to subject (Figure 2). Most subjects received on average ≥0.6 × 109 granulocytes per kilogram per transfusion (the equivalent of 42 × 109 granulocytes for a 70-kg subject) whereas a substantial minority (30%) of subjects received a lower dose, as low as 0.09 × 109 granulocytes per kilogram (the equivalent of 6 × 109 cells for a 70-kg subject). Whether or not subjects received high-dose or low-dose transfusions was not a random occurrence but was largely site-specific. These differences were not due to differences in the dose or timing of G-CSF or dexamethasone, the timing of the leukapheresis, the donor’s neutrophil count at the time of collection, or the amount of blood processed during the collection (data not shown).

Distribution of the average number of granulocytes per transfusion per kilogram (×109). Forty-nine subjects received at least 1 G-CSF–stimulated granulocyte transfusion with sufficient information to calculate dose.

Distribution of the average number of granulocytes per transfusion per kilogram (×109). Forty-nine subjects received at least 1 G-CSF–stimulated granulocyte transfusion with sufficient information to calculate dose.

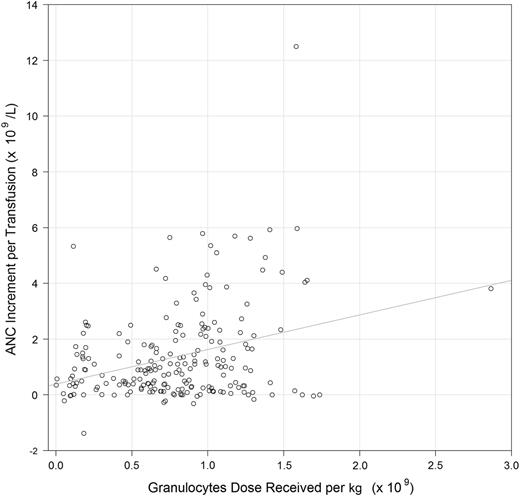

Two hundred nine of the 316 (66%) granulocyte transfusions had sufficient dose information and ANC values recorded within the proper timeframes to assess the relationship between dose and posttransfusion increment. In a generalized linear model for posttransfusion ANC increment, including both granulocyte dose per kilogram and time from product collection to administration, each additional 109 cells per kilogram administered was associated with an additional 1.75 × 109/L ANC increment (P < .001) (Figure 3), and each additional hour from collection to transfusion was associated with a 0.08 × 109/L lower increment (P = .056).

Scatterplot of posttransfusion ANC increments (×109/L) and granulocyte dose per kilogram (×109). The 209 of the 316 G-CSF–stimulated granulocyte transfusions (66%) that had sufficient dose information and ANC values recorded within proper timeframes were included.

Scatterplot of posttransfusion ANC increments (×109/L) and granulocyte dose per kilogram (×109). The 209 of the 316 G-CSF–stimulated granulocyte transfusions (66%) that had sufficient dose information and ANC values recorded within proper timeframes were included.

Transfusion reactions were defined as events from a prespecified list that occurred during or within 6 hours after the transfusion. When analyzed by subject, mild to moderate (grade 1-2) transfusion reactions were seen after 1 or more transfusions in 41% of subjects. These were most commonly fever, chills, and/or modest changes in blood pressure. More severe (grade 3-4) reactions were seen after at least 1 transfusion in 20% of subjects (n = 10). These included hypoxia (n = 7), tachycardia (n = 1), hypotension (n = 1), and an allergic reaction (n = 1). One subject experienced a grade 4 reaction (hypoxia) requiring temporary ventilatory support. When analyzed by transfusion, mild to moderate reactions were seen in 28% of the transfusions. More severe reactions (grade 3-4) were seen in <5% of transfusions, and the grade 4 reaction mentioned above was seen after 1 transfusion (<1%). No deaths were attributed to transfusion reactions. Of 307 transfusions with sufficient dose information, transfusion reactions occurred in 32 of 116 (27.6%) low-dose transfusions and 68 of 191 (35.6%) high-dose transfusions. There was no significant association between granulocyte dose (cells per kilogram) administered and presence of a transfusion reaction in a model adjusting for within-subject correlation (odds ratio [OR] = 1.07, 95% confidence interval [0.58, 1.95], P = .837).

Primary outcome

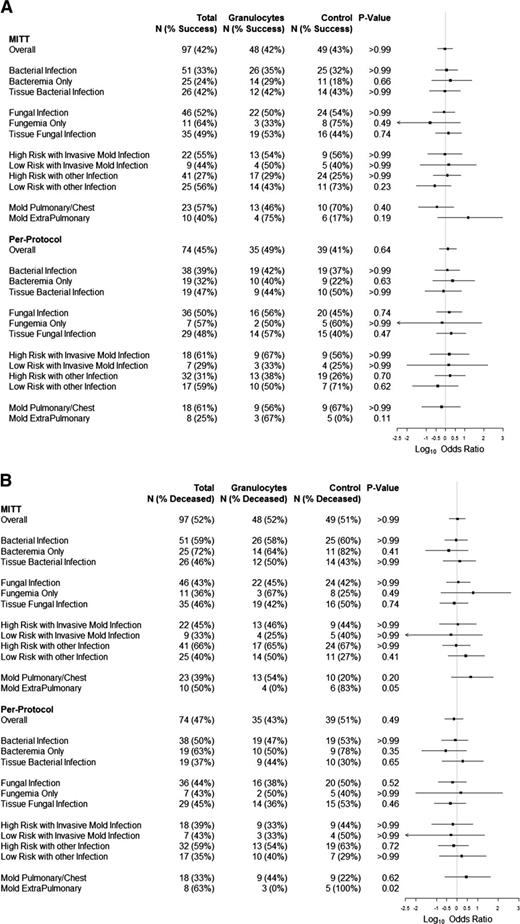

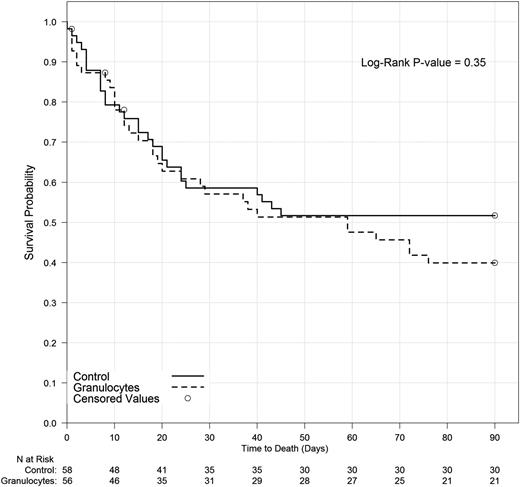

Success rates were 42% (20 of 48) and 43% (21 of 49) for the granulocyte and control groups, respectively (P > .99) on MITT analysis, and 49% (17 of 35) and 41% (16 of 39), respectively, for subjects who adhered to their assigned treatments (PP analysis; P = .64) (Figure 4). There was also no significant difference between treatment groups in a MITT model of the primary outcome that adjusted for baseline prognostic factors (ie, age, risk stratum, underlying disease, ventilator use, and high Zubrod score). Neither primary end point success rates nor survival to 42 days for granulocyte and control arms differed significantly within subgroups defined by infection type, infection location, or risk stratum whether analyzed by MITT or PP (Figure 4). Outcomes for patients who received the first transfusion within 2 days of eligibility were no different than outcomes for patients whose first transfusion was later. There was no significant association between the average posttransfusion ANC and the primary outcome (data not shown). Survival curves were similar for both treatment groups: hazard ratio, 1.29 for granulocyte vs control; 95% confidence interval (0.78, 2.15; P = .32) (Figure 5).

Forest plots. (A) Forest plot of primary outcome success stratified by infection. The percentage of subjects considered a success and the total number of subjects within each infection subgroup for both MITT and PP analyses are provided. Log10 ORs comparing success in the granulocyte arm to the control arm are displayed on the right; values >0 favor the granulocyte arm. (B) Forest plot of day 42 survival status stratified by infection. The percentage of subjects deceased at day 42 and the total number of subjects within each infection subgroup for both MITT and PP analyses are provided. Log10 ORs comparing day 42 death status in the granulocyte arm to the control arm are displayed on the right; values >0 indicate a higher rate of death at day 42 in the granulocyte arm.

Forest plots. (A) Forest plot of primary outcome success stratified by infection. The percentage of subjects considered a success and the total number of subjects within each infection subgroup for both MITT and PP analyses are provided. Log10 ORs comparing success in the granulocyte arm to the control arm are displayed on the right; values >0 favor the granulocyte arm. (B) Forest plot of day 42 survival status stratified by infection. The percentage of subjects deceased at day 42 and the total number of subjects within each infection subgroup for both MITT and PP analyses are provided. Log10 ORs comparing day 42 death status in the granulocyte arm to the control arm are displayed on the right; values >0 indicate a higher rate of death at day 42 in the granulocyte arm.

Survival to 90 days by treatment arm. Analyzed using Kaplan-Meier methodology. Three subjects were censored prior to day 90 due to missing information.

Survival to 90 days by treatment arm. Analyzed using Kaplan-Meier methodology. Three subjects were censored prior to day 90 due to missing information.

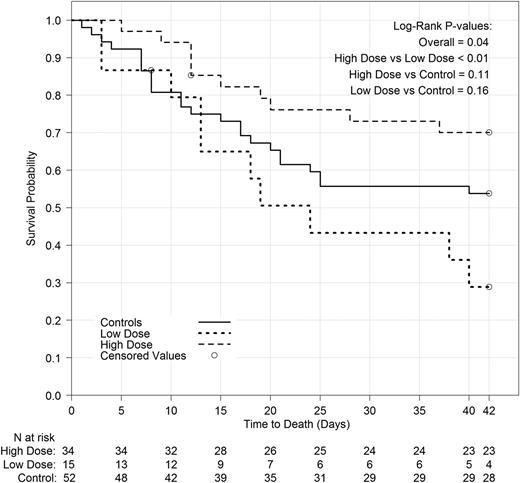

Because the study goal was to assess the effect of high-dose granulocyte therapy on the primary outcome, and because some patients did not receive high doses, in a post hoc analysis, we examined the relationship between the mean dose actually received by each patient (measured in cells per kilogram) and his/her primary outcome. The high-dose group (n = 29) included all subjects in the transfusion arm who received a mean dose of ≥0.6 × 109 granulocytes per kilogram per transfusion and had data available on the primary outcome; the low-dose group (n = 13) included all subjects in the transfusion arm who received a mean dose of <0.6 × 109/kg and had data on the primary outcome; the control group for this comparison (n = 43) included subjects in the control arm who received no transfusions and had data on the primary outcome. Subjects in the granulocyte arm who had no transfusions or had missing dose data and subjects in the control arm who received any granulocyte transfusions were excluded from this analysis. Primary outcome success was 59%, 15%, and 37% for the high-dose, low-dose, and control groups, respectively. Survival differences are shown in Figure 6. Subjects who received the higher granulocyte dose fared substantially and statistically significantly better than those receiving the lower dose, both in terms of primary outcome and survival (P < .01 and P = .02, respectively). Subjects in the control group did better than subjects in the low-dose group, and worse than subjects in the high-dose group, but these differences were not statistically significant.

Survival to 42 days by dose group. Analyzed using Kaplan-Meier methodology. Two subjects were censored prior to day 42 due to missing information.

Survival to 42 days by dose group. Analyzed using Kaplan-Meier methodology. Two subjects were censored prior to day 42 due to missing information.

Discussion

Overall, granulocyte transfusion therapy had no effect on the primary outcome, whether analyzed by MITT or PP. There was no significant difference between treatment groups in a model of the primary outcome that adjusted for baseline prognostic factors such as ventilator use or Zubrod score. There were also no significant differences between the granulocyte and control arms in the primary end point success rates for any infection type or patient risk category, whether analyzed by MITT or PP. In addition, survival through 90 days was not affected by the randomized treatment group.

These negative results may reflect the true state of affairs, that is, that granulocyte transfusions in this setting are not effective in clearing infection and prolonging survival. However, because of limitations in this study, one cannot interpret these results as proof that granulocyte transfusions are ineffective.

The first limitation is the low accrual rate. The study was designed to include 236 subjects, to provide 80% power if the true success rates in the control and transfused groups were 50% and 70%, respectively. The enrollment achieved was only 114, resulting in ∼47% power to detect that difference. Thus, it is possible that a clinically positive effect was missed by chance. There was even lower power to detect subgroups of patients that might have benefited more than others. There were several challenges in accrual for this study: first, the number of eligible patients at the clinical sites was lower than expected. Several years elapsed between the data collection used to estimate the number of available subjects and the time the study was completed, and fungal prophylaxis and diagnostic testing had improved during the interval.4,44-46 Second, several eligible patients were not enrolled in the study because their clinicians, the patients themselves, and/or family members did not accept the state of clinical equipoise. Some were convinced that granulocytes were efficacious and did not want to risk randomization to the control group. This was particularly a problem if granulocytes were available off-study at the site, even though these off-study transfusions were very low dose because they were from donors stimulated only with dexamethasone. Others were convinced that granulocytes were too dangerous and likely to be detrimental to the patient. Third, patients eligible for the study may not have been those for whom the clinician would normally consider granulocyte transfusions; in most instances, these patients were not deemed severely ill and were treated with antimicrobials alone. Finally, some subjects were lost to competing studies.

Another limitation concerned the dose of granulocytes actually received by the subjects. The purpose of the study was to evaluate the efficacy of high-dose granulocyte transfusions. The goal specified in the original protocol was to achieve a dose of at least 40 × 109 granulocytes per transfusion (0.6 × 109 cells per kilogram for a 70-kg subject). Unfortunately, more than one-quarter of the subjects received a mean dose less than this goal, often substantially less. When we compared results for subjects receiving a mean dose of ≥0.6 × 109 granulocytes per kilogram per transfusion to that for subjects receiving fewer granulocytes, the success rate was substantially higher (59%) in the high-dose group than it was in the low-dose group (15%), a difference that was highly significant, suggesting that the high-dose granulocytes were effective. However, caution in this interpretation is warranted because success in the control group was intermediate between that of the low-dose group and that of the high-dose group, although these differences were not statistically significant at the P < .05 level. Although it is theoretically possible that low doses of granulocytes are detrimental, it seems more likely that there is in fact no real difference between the success rates of the control and low-dose groups.

In conclusion, this study failed to provide the definitive answer on the efficacy of high-dose granulocyte transfusion therapy, although secondary analyses do provide suggestive evidence that there may be efficacy if higher doses are actually delivered to the patient. Another randomized trial would be needed to test the hypothesis that high-dose granulocytes are beneficial, but such a trial seems unlikely in the foreseeable future. Alternatively, a prospective registry to analyze the effect of delivered granulocyte dose on outcome could be pursued. Meanwhile, clinicians must base therapy decisions on these data and other existing evidence. If the decision is made to provide granulocyte transfusion therapy, it is important that clinicians determine that procedures at the collection facilities are adequate to ensure that high doses of granulocytes are actually delivered.

Presented in abstract form at the 56th annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, San Francisco, CA, December 8, 2014.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the trial staff, the physicians, and the patients and their families at the clinical trial sites for participating in the trial.

This work was supported by grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health to the Data Coordinating Center at the New England Research Institutes (HL072268), Boston Children’s Hospital (HL072291), Cornell University (HL072196), Johns Hopkins Hospital (HL072191), Puget Sound Blood Center (Bloodworks Northwest) (HL072305), University of Iowa (HL072028), University of Minnesota (HL072072), University of Oklahoma (HL072283), University of Pennsylvania (HL072346), University of Pittsburgh (HL072321), and BloodCenter of Wisconsin (HL072290).

Authorship

Contribution: T.H.P., J. McCullough, P.M.N., R.G.S., W.G.N., M.B., and J.-A.H.Y. designed the protocol; T.H.P., J. McCullough, P.M.N., R.G.S., M.B., R.W.H., T.H.H., and S.F.A. wrote the paper; R.W.H., T.H.H., and S.F.A. provided statistical analysis; T.H.P., M.B., J. McCullough, P.M.N., R.G.S., M.M.C., K.E.K., E.W., J. McFarland, J.H.C., S.R.S., D.F., S.P., B.S.S., and J.E.K. enrolled and cared for subjects and provided the data; and all authors reviewed the data, provided comments, and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: P.M.N. is a consultant to TerumoBCT (Lakewood, CO). J. McCullough is a member of the scientific advisory board of the Fenwal division of Fresenius Kabi and receives consulting fees for this service. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Thomas H. Price, University of Washington, 5201 NE 43rd St, Seattle, WA 98105; e-mail: thprice2@comcast.net.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal