Key Points

miR-181a regulates the NF-κB signaling pathway by targeting CARD11, NFKBIA, NFKB1, RELA/P65, and REL.

miR-181a represses NF-κB signaling and decreases cell proliferation and survival most potently in the NF-κB dependent ABC-DLBCL subgroup.

Abstract

Distinct subgroups of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) genetically resemble specific mature B-cell populations that are blocked at different stages of the immune response in germinal centers (GCs). The activated B-cell (ABC)–like subgroup resembles post-GC plasmablasts undergoing constitutive survival signaling, yet knowledge of the mechanisms that negatively regulate this oncogenic signaling remains incomplete. In this study, we report that microRNA (miR)-181a is a negative regulator of nuclear factor κ–light-chain enhancer of activated B-cells (NF-κB) signaling. miR-181a overexpression significantly decreases the expression and activity of key NF-κB signaling components. Moreover, miR-181a decreases DLBCL tumor cell proliferation and survival, and anti–miR-181a abrogates these effects. Remarkably, these effects are augmented in the NF-κB dependent ABC-like subgroup compared with the GC B-cell (GCB)–like DLBCL subgroup. Concordantly, in vivo analyses of miR-181a induction in xenografts results in slower tumor growth rate and prolonged survival in the ABC-like DLBCL xenografts compared with the GCB-like DLBCL. We link these outcomes to relatively lower endogenous miR-181a expression and to NF-κB signaling dependency in the ABC-like DLBCL subgroup. Our findings indicate that miR-181a inhibits NF-κB activity, and that manipulation of miR-181a expression in the ABC-like DLBCL genetic background may result in a significant change in the proliferation and survival phenotype of this malignancy.

Introduction

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. The standard therapy of rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone cures only about half of the patients,1,2 highlighting the need for better understanding DLBCL oncogenic mechanisms, which will ultimately lead to the identification of new molecular targets and therapeutic approaches. A major breakthrough in our understanding of DLBCL mechanism was facilitated by gene expression profiling analyses that delineated DLBCL into two main subgroups, the germinal center B-cell (GCB)–like and the activated B-cell (ABC)–like, named for the gene expression profiles similarity with the normal B-cell counterparts.3 These subgroups are distinct in that the ABC-like DLBCL is characterized by a more aggressive clinical course, shorter patient survival, and constitutive nuclear factor κ–light-chain enhancer of activated B-cells (NF-κB) signaling activity compared with the GCB-like DLBCL.4,5

Normal B cells activate NF-κB signaling in response to antigen encounter via the B-cell receptor (BCR) or other extracellular stimuli, commonly leading to growth and survival signaling. In normal B cells, this activity is transient, but in lymphoid malignancies such as ABC-like DLBCL, constitutive NF-κB signaling is maintained and contributes to sustained tumor cell survival.6 One well documented source of deregulated NF-κB activity in the ABC-like DLBCL subgroup has been attributed to higher mutation frequency in genes (CD79A/B, MYD88, CARD11, and A20) that act to propagate the BCR response and downstream NF-κB signaling effectors.7-9 These studies demonstrated that aberrant NF-κB signaling plays a critical role in DLBCL lymphomagenesis.6 Here we elucidated an NF-κB signaling repression mechanism that is mediated by a B-cell lineage-specific microRNA (miR).10

miRs are short noncoding RNAs that negatively regulate gene expression at the translational level through sequence-guided interaction with cognate messenger RNAs (mRNAs). miRs often serve as diagnostic and/or prognostic markers in disease classification, and recently they were also implicated in the lymphomagenesis process through their ability to modulate the expression of critical gene sets and signaling networks.11-14 miR-181a is an intronic miR that belongs to a family of four members, miR-181a-d (see supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood Web site). miR-181a/b are transcribed from two genomic loci (Ch.1q32.1 and Ch.9q33.3) and are predominantly expressed in the lymphoid system,15 whereas miR-181c/d are not detected in DLBCL tumors16 or in the normal counterparts.17 We previously demonstrated that miR-181a has a prognostic value in DLBCL, by establishing a positive correlation between high endogenous miR-181a expression in tumor biopsies and longer survival in patients undergoing rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone therapy.18 Beyond this prognostic value, we asked whether distinct miR-181a expression contributes to different DLBCL patient survival. Indeed, several studies demonstrated that miR-181a regulates key cell-survival proteins and oncogenic signaling pathways.19-21 We hypothesized that miR-181a downregulates the expression of critical genes and/or signaling pathways that maintain the neoplastic state. We found that miR-181a is a master regulator of NF-κB signaling. Moreover, the sustained miR-181a expression leads to proliferation arrest and cell death that is significantly more pronounced in the ABC-like DLBCL subgroup compared with the GCB-like DLBCL. These data feature the potent role of miR-181a as an NF-κB signaling inhibitor, and provide the molecular and cellular mechanism of miR-181a–mediated NF-κB signaling suppression.

Materials and methods

Cell lines

DLBCL cell lines were cultured in RPMI (Cellgro) with 10% fetal bovine serum (HyClone), or in Iscove modified Dulbecco medium (Cellgro) with 10% human plasma (the OCILY cell lines). HEK-293 and HeLa were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium with 10% fetal bovine serum, and all media contained 1% penicillin/streptomycine/l-glutamine (Cellgro). To induce the stable cell lines, cells were treated with doxycycline (DOX) (0.5 μg/mL). The authenticity tests of the cell lines were carried out with Genetica DNA Laboratories. Lymphocytes purification is described in supplemental Materials and methods.

miRNA overexpression

The miR oligonucleotides (oligos), plasmids, and generation of the inducible cell lines are described in supplemental Materials and methods.

miRNA target predictions

See supplemental Tables 1 and 2.

RNA isolation and real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

Previously described,22 and detailed in supplemental Materials and methods and supplemental Table 6 (assays on demand).

Luciferase reporter assays

Construction of the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) reporter plasmids is described in supplemental Materials and methods. For NF-κB reporter assay, we used the κB-TATA plasmid (a generous gift of Dr Edward Harhaj) and the Cignal NF-κB Reporter Assay Kit (QIAGEN).

Protein analysis

DNA binding

The electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) is detailed in supplemental Materials and methods as previously described.24 The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)–based NF-κB binding assay (Active Motif) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Cell viability and proliferation by fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS)

Cell viability was analyzed with the Annexin V and 7-aminoactinomycin D Apoptosis Detection Kit (BD Pharmingen), and cell proliferation by [3H]-thymidine incorporation as previously described.25

DLBCL xenografts

The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Miami approved all animal procedures. Six- to 8-week-old female nonobese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficiency mice were subcutaneously inoculated in the posterior flank with cells, which enabled the expression of miR-181a or control in response to DOX. The drinking water for the mice was supplemented with 1 mg/mL DOX (2.5 mg/day per mouse) and sucrose (2.5%).26 Additional details are provided in supplemental Materials and methods.

Ex vivo tumor analyses

Assays are described in detail in supplemental Materials and methods.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance was determined by Student t test or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). P < .05 were considered significant (*P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001; ****P < .0001). Survival was estimated with the Kaplan–Meier survival curve method and differences in survival were calculated by long-rank test (GraphPad Prism 6.0).

Results

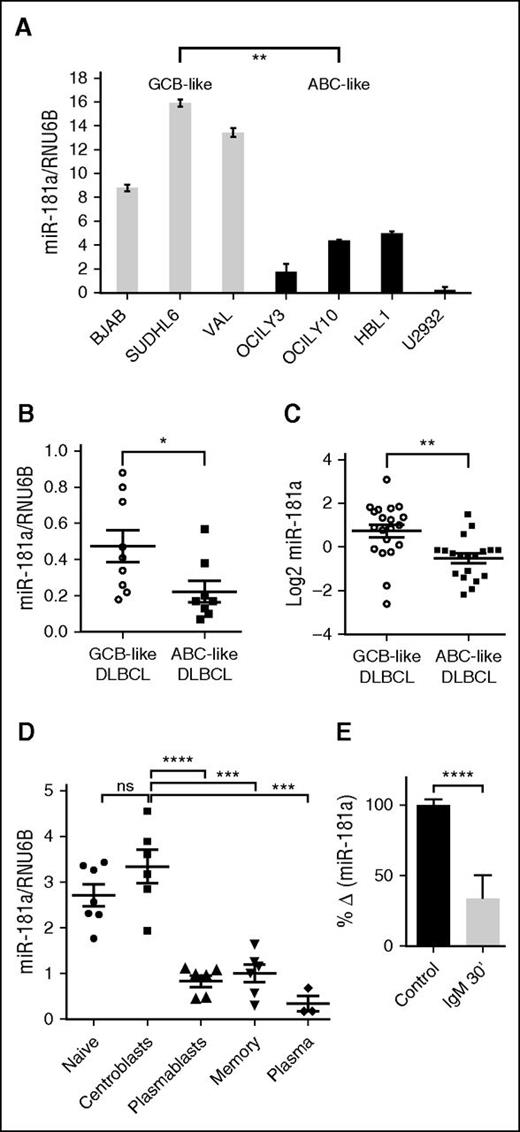

miR-181a expression is significantly decreased in ABCs

To elucidate the potential mechanisms that underlie the prognostic value of miR-181a in DLBCL, we analyzed the expression of miR-181a in GCB- and ABC-like DLBCL cell lines and primary tumors. We detected significantly lower miR-181a levels in the ABC-like subgroup compared with the GCB-like subgroup by quantitative real-time–PCR (Figure 1A-B). Concordantly, in a publicly available miRNA microarray data set of ABC- and GCB-like DLBCL patient cohort,16 miR-181a expression was significantly lower in the ABC-like DLBCL tumors compared with the GCB-like DLBCL tumors (Figure 1C). Because the DLBCL subgroups are closely related to distinct stages of mature B-cell differentiation,3 we assessed the miR-181a expression pattern in stages of mature B-cell ontology (from tonsils) that correspond to the DLBCL subgroups.27 miR-181a is dynamically regulated during this development process, exhibiting significantly higher levels in GC centroblasts (GCB cell-of-origin) compared with the plasmablasts (ABC cell-of-origin) (Figure 1D).

miR-181a expression is significantly decreased in ABC populations. miR-181a expression in (A) DLBCL cell lines that are classified as GCB-like or ABC-like (2 independent experiments in triplicates per cell line). (B) De novo primary DLBCL tumors (GCB-like, n = 9; ABC-like, n = 8). (C) ABC-like (n = 19) and GCB-like (n = 20) DLBCL tumors (P = .0015) from miRNA microarray data set, GSE 15250.16 (D) Different stages of mature B-cell differentiation subsets enriched from human tonsils by multiple purification steps that are described in supplemental Materials and methods (naïve, n = 7; centroblasts, n = 6; plasmablasts, n = 6; memory, n = 6; and plasma cells, n = 3). Lymphocytes were gated on CD19. Centroblasts (CD77+IgD−CD38+) and plasmablasts (IgD−CD38++CD27+CD20+) were distinguished based on the noted surface molecules expression. (E) Quantitative real-time–PCR miRNA assay analyses in human B cells purified from the blood of healthy donors and in vitro activated with anti-human IgM F (ab’)2 (10 μg/mL) for 30 minutes (n = 3; 2 independent experiments). Total RNAs extracted from the noted B-cell populations were analyzed for the expression of miR-181a. The expression was corrected for RNU6B levels. Shown is the change in mean normalized miR-181a expression ± standard error of the mean (SEM) upon stimulation. Statistical significance was determined by Student t test. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001; ****P < .0001. ns, not significant.

miR-181a expression is significantly decreased in ABC populations. miR-181a expression in (A) DLBCL cell lines that are classified as GCB-like or ABC-like (2 independent experiments in triplicates per cell line). (B) De novo primary DLBCL tumors (GCB-like, n = 9; ABC-like, n = 8). (C) ABC-like (n = 19) and GCB-like (n = 20) DLBCL tumors (P = .0015) from miRNA microarray data set, GSE 15250.16 (D) Different stages of mature B-cell differentiation subsets enriched from human tonsils by multiple purification steps that are described in supplemental Materials and methods (naïve, n = 7; centroblasts, n = 6; plasmablasts, n = 6; memory, n = 6; and plasma cells, n = 3). Lymphocytes were gated on CD19. Centroblasts (CD77+IgD−CD38+) and plasmablasts (IgD−CD38++CD27+CD20+) were distinguished based on the noted surface molecules expression. (E) Quantitative real-time–PCR miRNA assay analyses in human B cells purified from the blood of healthy donors and in vitro activated with anti-human IgM F (ab’)2 (10 μg/mL) for 30 minutes (n = 3; 2 independent experiments). Total RNAs extracted from the noted B-cell populations were analyzed for the expression of miR-181a. The expression was corrected for RNU6B levels. Shown is the change in mean normalized miR-181a expression ± standard error of the mean (SEM) upon stimulation. Statistical significance was determined by Student t test. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001; ****P < .0001. ns, not significant.

To examine if miR-181a expression is regulated by B-cell activation, we mimicked BCR stimulation with anti–immunoglobulin M (IgM) and examined the effect on miR-181a expression. BCR stimulation induced a decrease in miR-181a expression (Figure 1E). Interestingly, NF-κB signaling activity is also dynamically regulated in mature B-cell developmental stages and in the corresponding malignant cells of origin, yet display an inverse correlation with that of basal miR-181a levels (in early GC centroblasts and in GCB-like DLBCL, NF-κB activity is absent or weak compared with post-GC and ABC-like DLBCL where NF-κB activity is increased).8,9,28 This observation led to the hypothesis that miR-181a may function as a negative regulator of NF-κB signaling. In support of this idea, studies showed that miR-181a directly regulates the transcription factor FOXP1,18 which promotes DLBCL tumor survival by cooperating with the NF-κB signaling pathway.29 In addition, altered expression of miR-181a is reported in several hematologic malignancies that exhibit aberrant NF-κB activity.30-33

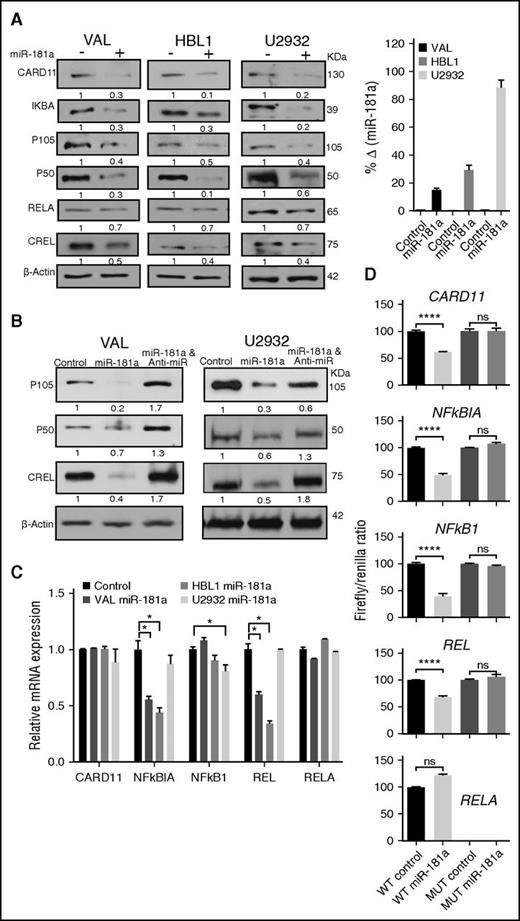

miR-181a targets several NF-κB signaling components directly

The ABC-like DLBCL subgroup expresses a profile of genes that are induced during a normal in vitro activation of peripheral blood B cells with anti-IgM antibody, interleukin-4, and/or CD403 stimuli that activate the survival signaling-pathway NF-κB. Indeed, the ABC-like DLBCL subgroup is most consistently associated with constitutive NF-κB signaling,4,5 which can also antagonize the apoptotic action of chemotherapy treatment.34 We searched for putative miR-181a target genes in four miRNA target prediction algorithms (supplemental Figure 1). The prediction of potential targets by at least one of the algorithms was sufficient for selection for further experimental examination. We identified a putative miR-181a binding site in the 3′UTRs in the following NF-κB signaling regulators35 : CARD11, NFKBIA (IKBΑ), NFKB1 (P105/P50), RELA/P65 (RELA), and REL (CREL) (supplemental Tables 1 and 2; supplemental Figures 2 and 3). Using gain-of-function analyses in DLBCL cell lines HBL1 and U2932 (ABC-like) or VAL (GCB-like), we explored the effect of miR-181a overexpression on these putative targets. In western blot analyses, we observed a significant decrease in the protein levels of these targets in the miR-181a transfected cells compared with the controls as noted by the band density values (Figure 2A; supplemental Figure 4). The transfection efficacy was confirmed by a quantitative real-time–PCR miR-181a assay indicating a robust increase in miR-181a expression (Figure 2A, right panel). Concordantly, in loss-of-function analyses with anti–miR-181a transfection, P105/P50 and CREL protein levels increased (Figure 2B; supplemental Figure 4). To differentiate between the effect of miR-181a on protein translation and mRNA stability, we examined changes in the mRNA transcripts. The results revealed a heterogeneous effect on the expression of the different gene transcripts in these cell lines (Figure 2C). To test whether miR-181a directly targets these genes, we cloned the 3′UTR with the miR-181a putative binding site or the mutated (MUT) binding site into luciferase reporter plasmids and assayed for reporter activity (Figure 2D). Compared with the control, miR-181a significantly repressed the luciferase activity of plasmids harboring the 3′UTR of CARD11, NFKBIA, NFKB1, and REL (P < .0001), but not that of RELA/P65 in reproducible trials (n = 6), indicating that the effect on RELA/P65 is indirect. The mutations in the seed-match sequences completely restored the luciferase activity (Figure 2D), suggesting that miR-181a regulates CARD11, NFKBIA, NFKB1, and REL directly. Together, the data indicate that miR-181a directly regulates several components of the NF-κB signaling pathway.

miR-181a directly targets several NF-κB signaling components. (A-B) Representative western blot analyses in DLBCL cell lines transfected with 2 μg precursor control (−), miR-181a (+), or miR-181a and anti–miR-181a by electroporation, and analyzed after 24 hours. Densitometry analyses of the protein bands were normalized to the loading control β-actin (NIH software; ImageJ). The relative band density values in (+) or anti-miR samples were compared with the controls (set as 1) and are noted below each blot. (A, right panel) Quantitative real-time–PCR miR-181a assay indicating the fold change in miR-181a expression between the control and miR-181a transfected samples as an assessment of transfection efficacy (2 independent experiments in triplicates). (C) Quantitative real-time–PCR analyses of NF-κB gene expression in cells transfected with control or miR-181a green fluorescent protein (GFP) plasmids for 24 hours. To enrich for transfected cells, the GFP+ cells were sorted and RNA prepared. Shown are the relative changes in gene expression from 2 independent experiments in triplicates. Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical significance was determined by Student t test. *P < .05. (D) Dual luciferase reporter assay in HeLa cells co-transfected with plasmids containing the noted WT or MUT 3′UTR sequence harboring putative miR-181a binding sites, and control or miR-181a plasmids. The firefly signals were normalized with the internal control renilla luciferase. Shown are the firefly/renilla ratios for each 3′UTR construct. The experiments were repeated 3 to 6 times in triplicates (mean ± SEM), and statistical significance analyzed by Student t test. ****P < .0001. ns, not significant; WT, wild-type.

miR-181a directly targets several NF-κB signaling components. (A-B) Representative western blot analyses in DLBCL cell lines transfected with 2 μg precursor control (−), miR-181a (+), or miR-181a and anti–miR-181a by electroporation, and analyzed after 24 hours. Densitometry analyses of the protein bands were normalized to the loading control β-actin (NIH software; ImageJ). The relative band density values in (+) or anti-miR samples were compared with the controls (set as 1) and are noted below each blot. (A, right panel) Quantitative real-time–PCR miR-181a assay indicating the fold change in miR-181a expression between the control and miR-181a transfected samples as an assessment of transfection efficacy (2 independent experiments in triplicates). (C) Quantitative real-time–PCR analyses of NF-κB gene expression in cells transfected with control or miR-181a green fluorescent protein (GFP) plasmids for 24 hours. To enrich for transfected cells, the GFP+ cells were sorted and RNA prepared. Shown are the relative changes in gene expression from 2 independent experiments in triplicates. Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical significance was determined by Student t test. *P < .05. (D) Dual luciferase reporter assay in HeLa cells co-transfected with plasmids containing the noted WT or MUT 3′UTR sequence harboring putative miR-181a binding sites, and control or miR-181a plasmids. The firefly signals were normalized with the internal control renilla luciferase. Shown are the firefly/renilla ratios for each 3′UTR construct. The experiments were repeated 3 to 6 times in triplicates (mean ± SEM), and statistical significance analyzed by Student t test. ****P < .0001. ns, not significant; WT, wild-type.

miR-181a represses NF-κB signaling activity

To determine whether the miR-181a–mediated repression of NF-κB proteins also leads to a net decrease in NF-κB signaling activity, we used several NF-κB activity assays. NF-κB luciferase reporter assay in a panel of ABC-like and GCB-like DLBCL cell lines co-transfected with miR-181a and NF-κB reporter showed a significant decrease in NF-κB activity (P < .0001) (Figure 3A), irrespective of the presence of NF-κB activating mutations in the DLBCL cell lines (supplemental Table 3). Concordantly, anti–miR-181a transfection in VAL and U2932 cells increased the NF-κB luciferase reporter activity (Figure 3B). miR-181a overexpression also decreased the level of poly ubiquitinated IκB kinase γ (IKKγ), a posttranslation modification event signifying the IKK complex activity (Figure 3C).36 Overall, these results indicate that miR-181a inhibits NF-κB activity.

miR-181a represses the NF-κB signaling activity. (A) Dual luciferase NF-κB reporter activity assay. DLBCL cell lines were co-transfected with the NF-κB luciferase reporter plasmid κB-TATA, renilla vector, and miR-181a, or control plasmids (24 hours). Three independent experiments in triplicates were analyzed per cell line. A nontargeting miRNA control (miR-29c) transfection in VAL cells is noted in gray. Results are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined by Student t test. (B) Dual luciferase NF-κB reporter activity assay in DLBCL cell lines. Cells were transfected with control or miR-181a. Twenty-four hours post-transfection, cells were counted and transfected again with either control or anti–miR-181a oligos (Ambion). At the 48-hour time point, the luciferase signal was analyzed. Three independent experiments in triplicates per cell line. (C) Anti-IKKγ immunoprecipitation. HEK-2932 or HBL1 cells were transfected with either miR-181a or control (24 hours), and immunoprecipitated from cellular protein extract with anti-IKKγ antibody or control IgG. Shown are the immunoblots with anti-ubiquitin antibody. The noted arrows indicate the poly ubiquitinated IKKγ bands (>50 kilodalton [kDa]). The IKKγ input controls are shown below. On the far right, a graphic representation of the relative ubiquitin bands density normalized to the IKKγ input from 3 independent experiments in the HEK-293 cells is shown. Statistical significance was determined by Student t test. Results are presented as mean ± SD. *P < .05; ***P < .001; ****P < .0001. ns, not significant.

miR-181a represses the NF-κB signaling activity. (A) Dual luciferase NF-κB reporter activity assay. DLBCL cell lines were co-transfected with the NF-κB luciferase reporter plasmid κB-TATA, renilla vector, and miR-181a, or control plasmids (24 hours). Three independent experiments in triplicates were analyzed per cell line. A nontargeting miRNA control (miR-29c) transfection in VAL cells is noted in gray. Results are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined by Student t test. (B) Dual luciferase NF-κB reporter activity assay in DLBCL cell lines. Cells were transfected with control or miR-181a. Twenty-four hours post-transfection, cells were counted and transfected again with either control or anti–miR-181a oligos (Ambion). At the 48-hour time point, the luciferase signal was analyzed. Three independent experiments in triplicates per cell line. (C) Anti-IKKγ immunoprecipitation. HEK-2932 or HBL1 cells were transfected with either miR-181a or control (24 hours), and immunoprecipitated from cellular protein extract with anti-IKKγ antibody or control IgG. Shown are the immunoblots with anti-ubiquitin antibody. The noted arrows indicate the poly ubiquitinated IKKγ bands (>50 kilodalton [kDa]). The IKKγ input controls are shown below. On the far right, a graphic representation of the relative ubiquitin bands density normalized to the IKKγ input from 3 independent experiments in the HEK-293 cells is shown. Statistical significance was determined by Student t test. Results are presented as mean ± SD. *P < .05; ***P < .001; ****P < .0001. ns, not significant.

The REL/NF-κB heterodimers that drive canonical NF-κB signaling (RELA/P50 and CREL/P50) are regulated primarily by IKBΑ-mediated retention of the REL/NF-κB dimers in the cytoplasm by masking the nuclear localization signal of REL proteins.37-40 We therefore examined the effect of miR-181a induction on the localization of the NF-κB proteins in nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions. We observed an overall decrease in both cellular compartments in the CREL and P50 immunoblots, yet in the analyses of RELA, an indirect target of miR-181a, a decrease was observed only in the cytoplasmic fraction (Figure 4A). This data suggests that miR-181a–mediated downregulation of IKBΑ may differentially affect the localization of nondirect targets of miR-181a (RELA), as compared with direct miR-181a targets (CREL and P50).

miR-181a decreases NF-κB binding to DNA-κB motif. (A) Western blot of cytoplasmic (Cyto.) or nuclear (Nuc.) fractions. The protein bands (NIH software; ImageJ) were normalized to β-actin or SP1, cytoplasmic and nuclear fraction markers, respectively (left). Graphical representations in U2932 cells (3 independent experiments) (right). Statistical significance was determined by Student t test and the results are presented as mean ± SD. (B) Quantitative ELISA-based assay of NF-κB transcription factors binding activity. Nuclear extracts (10 μg) were prepared as in panel A from the control or miR-181a inducible cell lines and incubated with the noted NF-κB antibodies. Standard curve was prepared with recombinant NF-κB P50 protein. WT consensus oligos or MUT oligos were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. Shown are cumulative results from 3 independent experiments; mean ± SEM. (C) EMSA as previously described.24 Briefly, double-stranded NF-κB consensus oligos were end-labeled with [32P]-adenosine triphosphate and incubated with U2932 nuclear extracts. For the super shift analyses, extracts were incubated with anti-P50 or anti-CREL antibodies. The DNA-protein complexes were resolved by electrophoresis, the gels were dried, and analyzed by autoradiography. The arrows indicate the super shift bands. See also insert (top right) for lanes 5 and 6 CREL super shift. Densitometry-based analysis of protein bands normalized to the loading control Oct-1 is shown. (D) Quantitative real-time–PCR analyses of NF-κB target genes in HBL1 cells transfected with GFP control or GFP–miR-181a plasmids (24 hours), and GFP sorted by FACS. Values are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3; 2 independent experiments). Shown are P50/CREL transcription complex specific NF-κB target genes that either contain (i) or lack (ii) putative miR-181a binding sites (Probability of Interaction by Target Accessibility algorithms). (E) Ratios of NF-κB P50 activity (as in [B] above) and quantitative real-time–PCR levels of miR-181a expression in primary GCB and non-GCB tumor samples. (F) Schematic diagram of study results showing the effect of differential miR-181a expression (low [i] and high [ii]) on the regulation of NF-κB signaling pathway. Red shadings indicate experimentally validated targets of miR-181a. In panels A and B, the Student t test statistical significance is as follows: *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001; ****P < .0001. WT, wild-type.

miR-181a decreases NF-κB binding to DNA-κB motif. (A) Western blot of cytoplasmic (Cyto.) or nuclear (Nuc.) fractions. The protein bands (NIH software; ImageJ) were normalized to β-actin or SP1, cytoplasmic and nuclear fraction markers, respectively (left). Graphical representations in U2932 cells (3 independent experiments) (right). Statistical significance was determined by Student t test and the results are presented as mean ± SD. (B) Quantitative ELISA-based assay of NF-κB transcription factors binding activity. Nuclear extracts (10 μg) were prepared as in panel A from the control or miR-181a inducible cell lines and incubated with the noted NF-κB antibodies. Standard curve was prepared with recombinant NF-κB P50 protein. WT consensus oligos or MUT oligos were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. Shown are cumulative results from 3 independent experiments; mean ± SEM. (C) EMSA as previously described.24 Briefly, double-stranded NF-κB consensus oligos were end-labeled with [32P]-adenosine triphosphate and incubated with U2932 nuclear extracts. For the super shift analyses, extracts were incubated with anti-P50 or anti-CREL antibodies. The DNA-protein complexes were resolved by electrophoresis, the gels were dried, and analyzed by autoradiography. The arrows indicate the super shift bands. See also insert (top right) for lanes 5 and 6 CREL super shift. Densitometry-based analysis of protein bands normalized to the loading control Oct-1 is shown. (D) Quantitative real-time–PCR analyses of NF-κB target genes in HBL1 cells transfected with GFP control or GFP–miR-181a plasmids (24 hours), and GFP sorted by FACS. Values are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3; 2 independent experiments). Shown are P50/CREL transcription complex specific NF-κB target genes that either contain (i) or lack (ii) putative miR-181a binding sites (Probability of Interaction by Target Accessibility algorithms). (E) Ratios of NF-κB P50 activity (as in [B] above) and quantitative real-time–PCR levels of miR-181a expression in primary GCB and non-GCB tumor samples. (F) Schematic diagram of study results showing the effect of differential miR-181a expression (low [i] and high [ii]) on the regulation of NF-κB signaling pathway. Red shadings indicate experimentally validated targets of miR-181a. In panels A and B, the Student t test statistical significance is as follows: *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001; ****P < .0001. WT, wild-type.

To assess the effect of miR-181a on binding to the DNA κB motif, we used a quantitative ELISA-based DNA binding assay with P50, CREL, and RELA antibodies. Concordant with the lower nuclear levels of CREL and P50 proteins, we observed a significant decrease in these protein bindings to DNA in the miR-181a samples compared with controls, but no significant decrease in RELA binding (Figure 4B). Similarly, EMSA analyses indicated a decrease in binding as reflected by decreased NF-κB/REL band intensity (Figure 4C, lane 1 vs 2). In addition, in super shift analyses with specific antibodies, we observed decreased band intensity in P50 (lane 3 vs 4) and CREL (lane 5 vs 6) with miR-181a overexpression. The effect of miR-181a on NF-κB activity was further evaluated by changes in the mRNA level of genes that are regulated by NF-κB transcription (Figure 4D). The panel included (1) NF-κB genes that either contain or (2) lack putative miR-181a binding sites in their respective 3′UTRs. The quantitative real-time–PCR analyses showed an overall decrease in these gene transcription levels in the miR-181a overexpressing cells compared with controls.

To test whether NF-κB activity in DLBCL primary samples may be correlated with relative miR-181a expression, we compared the ratio of P50 binding activity to miR-181a expression in GCB and non-GCB DLBCLs. The data in Figure 4E indicate higher ratios in the non-GCB samples. Our model in Figure 4F depicts that increased miR-181a expression negatively regulates the NF-κB signaling pathway via direct targeting of the transcription factors CREL/P50 and other NF-κB genes (red shading). Decreased cytoplasmic and nuclear CREL/P50 levels in turn results in a net NF-κB signaling repression (Figure 4Fii vs i).

miR-181a decreases cell proliferation and viability more potently in the ABC-like DLBCL cell lines compared with GCB-like DLBCL cell lines

The ABC-like DLBCL subgroup has constitutive NF-κB activity, which acts to sustain the tumor viability,4 an observation that is directly linked to DLBCL prognosis. In light of the miR-181a regulatory role on NF-κB activity, we tested the effects of miR-181a overexpression on cell proliferation and viability. In the [3H] thymidine incorporation assay, we observed a decreased proliferation in the miR-181a–expressing cells compared with the controls (Figure 5A). Interestingly, the effect was significantly more pronounced in the ABC-like DLBCL cell lines compared with the GCB-like DLBCL (P < .0001). Anti–miR-181a transfections completely rescued the proliferation effect of miR-181a in both DLBCL subgroups (Figure 5B). Moreover, in a cell viability FACS analysis, miR-181a overexpression significantly decreased the percent of live cells in the ABC-like DLBCL compared with the GCB-like DLBCL cell lines (Figure 5C-D; supplemental Figure 5). Together, the data indicate that the ABC-like DLBCL cell lines are more sensitive to miR-181a overexpression than the GCB-like DLBCL as measured by cell proliferation and viability.

miR-181a decreases cell proliferation and cell viability more potently in the ABC-like DLBCL compared with the GCB DLBCL cell lines. (A) Cell proliferation analyses. Cells were transfected with control or miR-181a plasmids, and at the noted time points post-transfection, 105 cells were counted and labeled with [3H] thymidine (2 Ci/mL) for 4 hours. Cells were transferred onto fiberglass filters and the radioactivity was read by a scintillation counter. Shown are the [3H] thymidine incorporation ratios of miR-181a to control from 3 independent experiments in triplicates per cell line. ABC-like DLBCL cell lines are noted in blue and GCB-like DLBCL cell lines in red. Statistical significance was determined by Student t test (****P < .0001) and the results are presented as mean ± SEM. (B) Anti–miR-181a cell proliferation rescue analyses. GCB-like (OCILY7 and OCILY19) and ABC-like (HBL1 and U2932) DLBCL cell lines were transfected with control or miR-181a plasmids. Twenty-four hours post-transfection, cells were counted and transfected again with either control or anti–miR-181a oligos. At 48 hours, cells were counted, labeled with [3H], and read as in panel A. Results are from 3 independent experiments in triplicates per cell line. Student t test (*P < .05) and the results are presented as mean ± SEM. (C) Cell viability FACS analyses in GCB-like (red) and ABC-like (blue) DLBCL cell lines. Three million cells per sample were transfected with control or miR-181a GFP plasmids. Four days post-transfection, the cells were stained with Annexin V–phycoerythrin (PE) and 7- aminoactinomycin D. The FACS analysis was performed on LSRFortessa-HTS, and the collected data were analyzed by FloJo software (Tree Star). The graphs depict cumulative results from 3 independent experiments showing the percent difference in live cells between the GFP+ miR-181a and GFP+ control transfected cells. Statistical significance was determined using two-way ANOVA (**P < .01) and the results are presented as mean ± SD. (D) Cell viability analyses in miR-181a inducible GCB-like and ABC-like DLBCL cell lines analyzed as in panel C. See also supplemental Figure 5.

miR-181a decreases cell proliferation and cell viability more potently in the ABC-like DLBCL compared with the GCB DLBCL cell lines. (A) Cell proliferation analyses. Cells were transfected with control or miR-181a plasmids, and at the noted time points post-transfection, 105 cells were counted and labeled with [3H] thymidine (2 Ci/mL) for 4 hours. Cells were transferred onto fiberglass filters and the radioactivity was read by a scintillation counter. Shown are the [3H] thymidine incorporation ratios of miR-181a to control from 3 independent experiments in triplicates per cell line. ABC-like DLBCL cell lines are noted in blue and GCB-like DLBCL cell lines in red. Statistical significance was determined by Student t test (****P < .0001) and the results are presented as mean ± SEM. (B) Anti–miR-181a cell proliferation rescue analyses. GCB-like (OCILY7 and OCILY19) and ABC-like (HBL1 and U2932) DLBCL cell lines were transfected with control or miR-181a plasmids. Twenty-four hours post-transfection, cells were counted and transfected again with either control or anti–miR-181a oligos. At 48 hours, cells were counted, labeled with [3H], and read as in panel A. Results are from 3 independent experiments in triplicates per cell line. Student t test (*P < .05) and the results are presented as mean ± SEM. (C) Cell viability FACS analyses in GCB-like (red) and ABC-like (blue) DLBCL cell lines. Three million cells per sample were transfected with control or miR-181a GFP plasmids. Four days post-transfection, the cells were stained with Annexin V–phycoerythrin (PE) and 7- aminoactinomycin D. The FACS analysis was performed on LSRFortessa-HTS, and the collected data were analyzed by FloJo software (Tree Star). The graphs depict cumulative results from 3 independent experiments showing the percent difference in live cells between the GFP+ miR-181a and GFP+ control transfected cells. Statistical significance was determined using two-way ANOVA (**P < .01) and the results are presented as mean ± SD. (D) Cell viability analyses in miR-181a inducible GCB-like and ABC-like DLBCL cell lines analyzed as in panel C. See also supplemental Figure 5.

Previous reports on miR-181a targets in nonlymphoid cells attributed the tumor suppressor-like properties of miR-181a to direct targeting of the anti-apoptotic protein BCL2.41,42 To this end, we performed rescue experiments utilizing transfections of BCL2 plasmid lacking the 3′UTR. As previously reported, we observed a decrease in the BCL2 protein and mRNA levels (Figures 6A and 4Di); however, in a rescue experiment, BCL2 transfection did not alleviate the effect of miR-181a on either cell proliferation or cell viability (Figure 6A-B; supplemental Figure 6).

CREL rescues the miR-181a–mediated cell death. (A) BCL2 cell proliferation rescue experiment. DOX-inducible U2932 cells were transfected with control empty vector or BCL2 plasmid lacking the 3′UTR (24 hours), and then induced to express control or miR-181a with DOX for 48 hours. At 72 hours post-transfection, 105 cells were counted and labeled with [3H] thymidine (2 Ci/mL) for 4 hours. The cells were then transferred onto fiberglass filters and the radioactivity was read by a scintillation counter. Shown are the [3H] thymidine incorporation ratios of miR-181a to control from 3 independent experiments in triplicates. Statistical significance was determined by Student t test (***P < .001) and the results are presented as mean ± SEM. Shown below is a western blot control for BCL2 overexpression in U2932 transfected cells (48 hours). Densitometry analyses of the protein bands were normalized to the loading control β-actin (NIH software; ImageJ), and the relative band density values in miR-181a (+) or BCL2 samples were compared with the control (set as 1) and are noted below the blot. (B) BCL2 cell viability rescue analysis in inducible U2932 cells transfected as in panel A above. The cells were washed and stained with Annexin V–FITC and with an irreversible dead-cells labeling dye, allophycocyanin-Cy7, and gated on the PE Texas Red+ populations. The graph depicts cumulative results from 3 independent experiments, showing the percent difference in live cells between the induced miR-181a and the control cells. Statistical significance was determined by Student t test (***P < .001) and the results are presented as mean ± SD. (C) NF-κB transcription factors cell viability rescue analysis as in panel B above. Shown is a representative FACS analysis (i). The graph depicts cumulative results from 3 independent experiments (ii), and a western blot control for the protein overexpression in U2932 cells at 48 hours (iii). See also supplemental Figure 6. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; ns, not significant; pcDNA, plasmid cytomegalovirus promoter DNA.

CREL rescues the miR-181a–mediated cell death. (A) BCL2 cell proliferation rescue experiment. DOX-inducible U2932 cells were transfected with control empty vector or BCL2 plasmid lacking the 3′UTR (24 hours), and then induced to express control or miR-181a with DOX for 48 hours. At 72 hours post-transfection, 105 cells were counted and labeled with [3H] thymidine (2 Ci/mL) for 4 hours. The cells were then transferred onto fiberglass filters and the radioactivity was read by a scintillation counter. Shown are the [3H] thymidine incorporation ratios of miR-181a to control from 3 independent experiments in triplicates. Statistical significance was determined by Student t test (***P < .001) and the results are presented as mean ± SEM. Shown below is a western blot control for BCL2 overexpression in U2932 transfected cells (48 hours). Densitometry analyses of the protein bands were normalized to the loading control β-actin (NIH software; ImageJ), and the relative band density values in miR-181a (+) or BCL2 samples were compared with the control (set as 1) and are noted below the blot. (B) BCL2 cell viability rescue analysis in inducible U2932 cells transfected as in panel A above. The cells were washed and stained with Annexin V–FITC and with an irreversible dead-cells labeling dye, allophycocyanin-Cy7, and gated on the PE Texas Red+ populations. The graph depicts cumulative results from 3 independent experiments, showing the percent difference in live cells between the induced miR-181a and the control cells. Statistical significance was determined by Student t test (***P < .001) and the results are presented as mean ± SD. (C) NF-κB transcription factors cell viability rescue analysis as in panel B above. Shown is a representative FACS analysis (i). The graph depicts cumulative results from 3 independent experiments (ii), and a western blot control for the protein overexpression in U2932 cells at 48 hours (iii). See also supplemental Figure 6. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; ns, not significant; pcDNA, plasmid cytomegalovirus promoter DNA.

Our analyses of miR-181a targets suggest that the NF-κB transcription factors P50 and CREL are critical components in the miR-181a–mediated NF-κB repression. We therefore performed similar rescue experiments with plasmids encoding P50 or CREL, lacking the respective 3′UTRs. In a cell viability assay, the transcription factor P50 did not rescue the miR-181a effect on cell death; however, we observed a partial but significant rescue with CREL (Figure 6C), highlighting that CREL may be a critical factor in the miR-181a–mediated NF-κB repression.

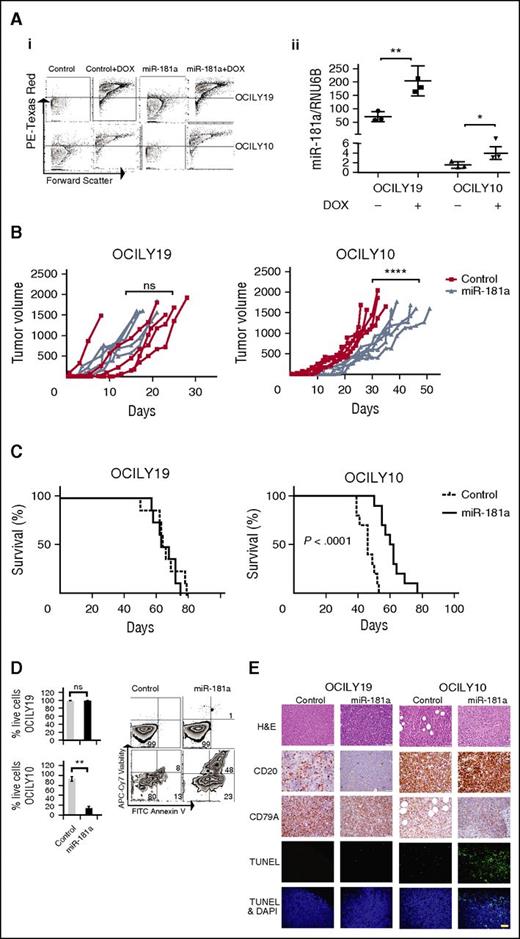

miR-181a slows the tumor growth rate and prolongs the animal survival in an ABC-like DLBCL xenograft model

To examine if the effect of miR-181a on cell viability can also be observed in vivo, we used DLBCL xenograft models. Groups (n = 10) of nonobese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficiency mice were subcutaneously inoculated with inducible OCILY10 (ABC-like) or low CD20 expressing OCILY19 (GCB-like)43 cells stably expressing pTet-On control or pTet-On miR-181a vectors, enabling miR-181a and mCherry expression in the tumor cells in response to DOX. miR-181a or control cells were induced in the mice tumors by supplementing the drinking water with DOX. Assessment of the induction efficacy by FACS revealed a similar increase in mCherry expression levels in all the groups (>90%) and a robust increase in miR-181a expression in the miR-181a groups (Figure 7A). Measurements of changes in the mice tumor volume over time indicate that the tumor growth rate in the pTet-On miR-181a OCILY10 (ABC-like) xenografts is significantly slower compared with the control group (Figure 7B), and in turn results in a significantly longer animal survival (Figure 7C). In contrast, we did not observe significant changes in tumor growth rate or survival in the OCILY19 miR-181a xenografts compared with controls (Figure 7B-C). The ex vivo analyses of the effect of miR-181a on cell viability indicate a significant decrease in the ABC-like (P = .0023) but not in the GCB-like–derived tumors (Figure 7D). This observation was validated by terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay analyses showing an increased number of fluorescein-labeled cells in the ABC-derived tumors (Figure 7E) compared with the GCB-like DLBCL. Overall, the in vivo data indicate that the effect of miR-181a on ABC-like DBLCL cell viability can be similarly observed in DLBCL xenograft models, and suggest that the reason that miR-181a is a marker of better prognosis is linked to its regulatory function as NF-κB signaling inhibitor.

miR-181a slows tumor growth rate and prolongs animal survival in the ABC-like DLBCL xenograft model. Xenografts were generated with OCILY19 (GCB-like DLBCL) or OCILY10 (ABC-like DLBCL) cells (5 × 106), induced to express control or miR-181a by supplementing the mice drinking water with DOX (1 mg/mL). (A) Ex vivo assessment of efficient DOX induction in the animals. FACS analyses of RFP+ signal from control and miR-181a–induced OCILY19 and OCILY10 cells extracted from the mice tumors (i), and quantitative real-time–PCR analysis of miR-181a expression (ii) corrected for RNU6B levels, mean ± SE (n = 3; 2 independent experiments), Student t test (*P < .05; **P < .01). (B) Tumor growth curves. The tumor volume was assessed 3 times a week with calipers, 10 mice per cell line (n = 5 control; n = 5 miR-181a). Statistical significance two-way ANOVA tests (****P < .0001) from 2 independent experiments. (C) Kaplan–Meier plots: OCILY19 (n = 8 per group) and OCILY10 (n = 10 per group). Mice where euthanized when the tumor volume reached 1500 mm3 in accordance with the institutional guidelines. Statistical significance by log-rank test from 2 independent experiments. (D) Ex vivo analyses of the tumors. The xenografts were generated as described in panel A but the DOX treatment (8 days) was initiated when the tumors were palpable (∼2 weeks). Shown are representative FACS analyses of PE Texas Red+ cells evaluated for cell viability. The cells were stained with Annexin V–FITC and allophycocyanin-Cy7. The graph below depicts cumulative results (n = 4 mice per group), showing the percent difference in live cells between the induced miR-181a and the control cells. Statistical significance by Student t test (**P < .01; ns, not significant) presented as mean ± SD. (E) Immunohistochemistry and TUNEL assay in paraffin embedded xenograft tumors slides. Thin histologic sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), and analyzed for the expression of the B-cell markers CD20 (low expression in OCILY19 cell line43 ) or CD79A. The TUNEL assays were performed with the In Situ Cell Death Detection Fluorescein Kit following the manufacturer’s instructions. Nuclei were labeled with DAPI, and images were acquired on a Zeiss LSM 700 confocal microscope at ×400 magnification. Bar, 40 μm. One representative mouse out of 3 per group is shown. DAPI, 4,6 diamidino-2-phenylindole.

miR-181a slows tumor growth rate and prolongs animal survival in the ABC-like DLBCL xenograft model. Xenografts were generated with OCILY19 (GCB-like DLBCL) or OCILY10 (ABC-like DLBCL) cells (5 × 106), induced to express control or miR-181a by supplementing the mice drinking water with DOX (1 mg/mL). (A) Ex vivo assessment of efficient DOX induction in the animals. FACS analyses of RFP+ signal from control and miR-181a–induced OCILY19 and OCILY10 cells extracted from the mice tumors (i), and quantitative real-time–PCR analysis of miR-181a expression (ii) corrected for RNU6B levels, mean ± SE (n = 3; 2 independent experiments), Student t test (*P < .05; **P < .01). (B) Tumor growth curves. The tumor volume was assessed 3 times a week with calipers, 10 mice per cell line (n = 5 control; n = 5 miR-181a). Statistical significance two-way ANOVA tests (****P < .0001) from 2 independent experiments. (C) Kaplan–Meier plots: OCILY19 (n = 8 per group) and OCILY10 (n = 10 per group). Mice where euthanized when the tumor volume reached 1500 mm3 in accordance with the institutional guidelines. Statistical significance by log-rank test from 2 independent experiments. (D) Ex vivo analyses of the tumors. The xenografts were generated as described in panel A but the DOX treatment (8 days) was initiated when the tumors were palpable (∼2 weeks). Shown are representative FACS analyses of PE Texas Red+ cells evaluated for cell viability. The cells were stained with Annexin V–FITC and allophycocyanin-Cy7. The graph below depicts cumulative results (n = 4 mice per group), showing the percent difference in live cells between the induced miR-181a and the control cells. Statistical significance by Student t test (**P < .01; ns, not significant) presented as mean ± SD. (E) Immunohistochemistry and TUNEL assay in paraffin embedded xenograft tumors slides. Thin histologic sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), and analyzed for the expression of the B-cell markers CD20 (low expression in OCILY19 cell line43 ) or CD79A. The TUNEL assays were performed with the In Situ Cell Death Detection Fluorescein Kit following the manufacturer’s instructions. Nuclei were labeled with DAPI, and images were acquired on a Zeiss LSM 700 confocal microscope at ×400 magnification. Bar, 40 μm. One representative mouse out of 3 per group is shown. DAPI, 4,6 diamidino-2-phenylindole.

Discussion

Sustained NF-κB signaling activity contributes to the pathogenesis of DLBCL. Herein, we provide evidence that miR-181a negatively regulates NF-κB signaling activity, and acts as a master regulator to fine-tune NF-κB signaling and oppose tumor-cell proliferation and viability. Our results have implications for the role of miR-181a in the survival of ABC-like DLBCLs.

DLBCL is a lymphoid malignancy that represents a medical challenge because current therapy cures only about 50% of patients. Concerted efforts to delineate this histologically indistinguishable disease into genetically distinct subgroups increased our knowledge of unique pathogenic mechanisms that characterize each subgroup, ultimately leading to the identification of new molecular targets and therapeutic approaches. In this study, we investigated how relatively high miR-181a expression positively correlates with improved survival in patients undergoing therapy. We found that distinct miR-181a expression can delineate the ABC-like and GCB-like DLBCL subgroups, and functionally link miR-181a with oncogenic mechanisms.

In systematic analyses of basal miR-181a levels in ABC-like and GCB-like DLBCL cell lines, patient tumors, and in the normal putative cell-of-origin of these subgroups, we observed significantly lower miR-181a levels in ABC-like DLBCL compared with GCB-like DLBCL. This data suggests that the miR-181a expression signature is an integral component in the expression profile of these subgroups. In addition, because the ABC-like DLBCLs survival outcome is significantly worse than that of GCB-like DLBCLs, we hypothesized that miR-181a may downregulate critical genes and/or signaling pathways that affect ABC-like DLBCL survival. Indeed, the ABC-like DLBCL subgroup is most consistently associated with constitutive NF-κB signaling,4,5 a cascade that promotes survival signaling and antagonizes the apoptotic action of chemotherapy treatment.34

Accordingly, we identified and validated that miR-181a targets five NF-κB signaling components and decreases NF-κB signaling activity. Among these targets, the signaling adapter CARD11 has been established in genetic studies as a DLBCL oncogene.8,9,44 RELA, CREL, and P50 are transcription factors that drive canonical NF-κB signaling commonly as the RELA/P50 or CREL/P50 heterodimers, and IKBΑ negatively regulates the nuclear localization of NF-κB transcription factors. miR-181a overexpression decreased the protein level of these targets in DLBCL cell lines and anti–miR-181a increased the protein levels. Concordantly, the miR-181a–mediated targeting of NF-κB signaling components led to decreased NF-κB signaling activity as measured by NF-κB luciferase reporter assay, EMSA, or by IKKγ ubiquitination, whereas anti–miR-181a expression increased NF-κB activity.

In vitro studies that used NF-κB inhibitors previously demonstrated that compared with the GCB-like, the ABC-like DLBCL is significantly more sensitive to NF-κB inhibition where increased tumor cell death is observed. These findings helped establish NF-κB activity dependence in the pathogenesis of the ABC-like DLBCL subgroup.5 Our results show that miR-181a overexpression phenocopied NF-κB inhibition in DLBCL cell lines. We observed a significant sensitivity to miR-181a overexpression in cell proliferation and survival in the ABC-like DLBCL compared with the GCB-like DLBCL. These findings further support the role of miR-181a as a negative regulator of NF-κB signaling. Concordantly, in vivo analyses in DLBCL xenograft models inoculated with ABC-like or GCB-like DLBCL cell lines showed that the ABC-like DLBCL xenografts are more sensitive to sustained miR-181a expression than the GCB-like DLBCL xenografts, and display significantly slower tumor growth rate and prolonged survival. Our model (Figure 4F) suggests that a shift in miR-181a expression could significantly change the level of nuclear CREL and P50, and in turn NF-κB activity on which the ABC-like DLBCLs depend.

Our analyses further indicate that the effect on cell death is not due to miR-181a targeting of BCL2, because BCL2 overexpression does not rescue the miR-181a effect. Instead, the miR-181a–mediated cell death depends on the expression of CREL as established in cell viability rescue analyses. In support of these findings, the NF-κB transcription factor CREL is a known regulator of B-cell survival.45,46 In addition, the REL locus is amplified in certain human B-cell lymphomas, and as a canonical NF-κB transcription factor, CREL is implicated as an oncogene in human lymphomas that are characterized with constitutive NF-κB activity. Moreover, our findings are in agreement with a recent study on the role of canonical NF-κB transcription factors in GC development. In analyses of conditionally deleted rel in GCBs, Heise et al determined that CREL is specifically associated with failure to activate a metabolic program that promotes cell growth after the formation of dark and light zones in the GC reaction.47 Because metabolic programs that promote cell growth present an important criteria to cell division, and inhibition of these programs arrest cell growth and lead to cell death, our results on CREL are in agreement with their findings. Furthermore, the temporal dependence on CREL activity coincides with a post-centroblasts GC development stage that is associated with the ABC-like DLBCL cell-of-origin developmental stage and with a significant decrease in basal miR-181a expression. We conclude that the miR-181a–mediated cell death in the ABC-like DLBCL subgroup is primarily due to direct targeting of CREL.

We noted however that the CREL rescue is incomplete, an observation that suggests a miR-181a effect on additional components or signaling pathways that are implicated in the survival of DLBCL. Indeed, miR-181a was shown to target components in the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathways, which are capable of providing critical survival signaling to mature B cells downstream of the BCR in the absence of NF-κB.6,48 Additional studies are required to identify these targets and/or signaling pathways, which will in turn enhance our understanding of DLBCL pathogenesis and help identify new therapeutic approaches.

Other miRs that are implicated in B-cell lymphoma were shown to regulate NF-κB signaling.30 For example, miR-146 targets the tumor necrosis factor receptor associated factor 6 and interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase 1,49 miR-155 targets IKKβ and IKKε, and miR-181b was shown to repress NF-κB signaling in endothelial cells through an indirect targeting of RELA.50 Although several studies have established the nonredundant function of the miR-181 family members miR181a-d,51-53 the noted study on miR-181b prompted us to test the role of miR-181b on NF-κB regulation in the DLBCL genetic background. Our results indicate that the basal miR-181b expression pattern in DLBCL is similar to that of miR-181a (supplemental Figure 1B-D), yet miR-181b overexpression failed to inhibit NF-κB signaling in DLBCL cell lines (supplemental Figure 1E). Similarly, miR-181c overexpression also failed to inhibit NF-κB signaling in DLBCL cell lines (supplemental Figure 1F). These findings support a specific role for miR-181a in NF-κB inhibition. Mechanistically, differences in the secondary structures of the precursor miR moiety and/or the variable sequence in the mature miR may account for these functional differences (supplemental Figure 1A). We demonstrate that miR-181a is a new NF-κB signaling modulator that directly targets four key NF-κB signaling proteins and fine-tunes NF-κB signaling activity in DLBCL.

Our findings raise the possibility that distinct miR-181a expression may play a role in DLBCL patient survival. Because we demonstrate that miR-181a expression prolongs the survival of animals bearing ABC-like DLBCL xenograft tumors, it is attractive to entertain the possibility that miR-181a may be used as a novel therapeutic tool for this DLBCL subgroup. Indeed, there is widespread interest in targeting the NF-κB signaling pathway in lymphomas and in using miRs as a novel class of drugs. An miRNA replacement therapy phase I study is underway with miR-34.54,55 Because lymphoma is perceived as a “pathway disease,” miR-based therapies may be beneficial. However, further studies to examine usage of miR-181a as a therapeutic tool in lymphoma are needed.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Toomey Ngoc from the laboratory of Juan Carlos Ramos (University of Miami) for assisting with the EMSA experiments; Edward Harhaj (John Hopkins University) for the NF-κB luciferase reporter plasmid κB-TATA, and for the pcDNA CREL, P50, and RELA; Khaled Tolba (University of Miami) for the BCL2 and IKKγ-pcDNA plasmids; the flow cytometry core facility members at the University of Miami for their help in designing the FACS analyses; Gabriel Gaidosh (University of Miami imaging facility) for his help with the immunofluorescence image acquisition; Zhang Yu (Dana) for advice on lymphocyte purification; Kranthi Kunkalla from the laboratory of Francisco Vega at the University of Miami for assisting with the immunohistochemistry (IHC) samples; and finally, the members of the Lossos laboratory for helpful discussions.

This research was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Lymphoma Research Foundation (M1200495) (G.A.K.). I.S.L. is supported by the Lymphoma Research Foundation, as well as the Dwoskin, Recio, Greg Olsen, and Anthony Rizzo Family Foundations.

Authorship

Contribution: G.A.K. designed and performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper; X.J. performed cloning experiments; S.B. performed animal experiments; J.R. provided the tonsils and performed experiments; F.V. performed IHC experiments and analyzed the data; R.S. and A.M. performed experiments and analyzed the data; and I.S.L. conceptualized, designed, supervised the project, and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Izidore S. Lossos, Batchelor Children’s Institute, 1580 NW 10th Ave, Room 415, Miami, FL 33136; e-mail: ilossos@med.miami.edu; and Goldi A. Kozloski, Batchelor Children’s Institute, 1580 NW 10th Ave, Room 416, Miami, FL 33136; e-mail:gkozlosk@med.miami.edu.

![Figure 3. miR-181a represses the NF-κB signaling activity. (A) Dual luciferase NF-κB reporter activity assay. DLBCL cell lines were co-transfected with the NF-κB luciferase reporter plasmid κB-TATA, renilla vector, and miR-181a, or control plasmids (24 hours). Three independent experiments in triplicates were analyzed per cell line. A nontargeting miRNA control (miR-29c) transfection in VAL cells is noted in gray. Results are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined by Student t test. (B) Dual luciferase NF-κB reporter activity assay in DLBCL cell lines. Cells were transfected with control or miR-181a. Twenty-four hours post-transfection, cells were counted and transfected again with either control or anti–miR-181a oligos (Ambion). At the 48-hour time point, the luciferase signal was analyzed. Three independent experiments in triplicates per cell line. (C) Anti-IKKγ immunoprecipitation. HEK-2932 or HBL1 cells were transfected with either miR-181a or control (24 hours), and immunoprecipitated from cellular protein extract with anti-IKKγ antibody or control IgG. Shown are the immunoblots with anti-ubiquitin antibody. The noted arrows indicate the poly ubiquitinated IKKγ bands (>50 kilodalton [kDa]). The IKKγ input controls are shown below. On the far right, a graphic representation of the relative ubiquitin bands density normalized to the IKKγ input from 3 independent experiments in the HEK-293 cells is shown. Statistical significance was determined by Student t test. Results are presented as mean ± SD. *P < .05; ***P < .001; ****P < .0001. ns, not significant.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/127/23/10.1182_blood-2015-11-680462/4/m_2856f3.jpeg?Expires=1767761747&Signature=AnuXNMWtJkFi2ywsG4JLqxfN-Y0t1swq1p-PfHYdShjh6W8LlShhvX4vG189wI1GDiCg477AgDO1zwqhcEXuq5X-ZmZdxAp3dqEOOb327bhjHi1rWqyCT7TB4zboeVCCyEro2Le7ArbW4stgWII398pS~WnI0~yIkDo0GPhyKET~pZhGTZmOfpBb3ctnLdLjSgITAqHHFNl14eIZsZjLCROd~K4yBPtFMtr~aeygRzXecm9Z~7cfy6a~bb5FbHXL7LHvyykp7WK~xIv7SURGU7uAfoicDqPNhb8CUrdrmDiNvgDQfQrzS5SRTVc4LtE2FYGztUBDClInlz4ii70dFg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 4. miR-181a decreases NF-κB binding to DNA-κB motif. (A) Western blot of cytoplasmic (Cyto.) or nuclear (Nuc.) fractions. The protein bands (NIH software; ImageJ) were normalized to β-actin or SP1, cytoplasmic and nuclear fraction markers, respectively (left). Graphical representations in U2932 cells (3 independent experiments) (right). Statistical significance was determined by Student t test and the results are presented as mean ± SD. (B) Quantitative ELISA-based assay of NF-κB transcription factors binding activity. Nuclear extracts (10 μg) were prepared as in panel A from the control or miR-181a inducible cell lines and incubated with the noted NF-κB antibodies. Standard curve was prepared with recombinant NF-κB P50 protein. WT consensus oligos or MUT oligos were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. Shown are cumulative results from 3 independent experiments; mean ± SEM. (C) EMSA as previously described.24 Briefly, double-stranded NF-κB consensus oligos were end-labeled with [32P]-adenosine triphosphate and incubated with U2932 nuclear extracts. For the super shift analyses, extracts were incubated with anti-P50 or anti-CREL antibodies. The DNA-protein complexes were resolved by electrophoresis, the gels were dried, and analyzed by autoradiography. The arrows indicate the super shift bands. See also insert (top right) for lanes 5 and 6 CREL super shift. Densitometry-based analysis of protein bands normalized to the loading control Oct-1 is shown. (D) Quantitative real-time–PCR analyses of NF-κB target genes in HBL1 cells transfected with GFP control or GFP–miR-181a plasmids (24 hours), and GFP sorted by FACS. Values are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3; 2 independent experiments). Shown are P50/CREL transcription complex specific NF-κB target genes that either contain (i) or lack (ii) putative miR-181a binding sites (Probability of Interaction by Target Accessibility algorithms). (E) Ratios of NF-κB P50 activity (as in [B] above) and quantitative real-time–PCR levels of miR-181a expression in primary GCB and non-GCB tumor samples. (F) Schematic diagram of study results showing the effect of differential miR-181a expression (low [i] and high [ii]) on the regulation of NF-κB signaling pathway. Red shadings indicate experimentally validated targets of miR-181a. In panels A and B, the Student t test statistical significance is as follows: *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001; ****P < .0001. WT, wild-type.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/127/23/10.1182_blood-2015-11-680462/4/m_2856f4.jpeg?Expires=1767761748&Signature=yy-JsRlLM0vaoFujTpv7OxFEf4g4xpaGH9g6JZxZUmqO2wshZUUKaFNPtd-ksg6dzmXy~62IrD~09HZqL7OlNxPja47938iWLVnhxSV4OzFKl9ZgTpgXnj8PniR~2KG~bpuEO85D22iKO1CLDtQhQOuxC3HUKFadKNC~gPhrbxN-Yig99oSmidAe6-vtEy4gk7HGjGVUO4TZR32QSN~Mc-W7thg4VMYnOStFfKLjA5GtkqUkX17mayevxkuN7GpE23iNmdDABv-h-vmXKJSCEWumUj8nmvmnV~0z58xspLZeXbx1fHTKYuylQqnA71gUnFambFwdV-YoOxpX6ZDsyw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 5. miR-181a decreases cell proliferation and cell viability more potently in the ABC-like DLBCL compared with the GCB DLBCL cell lines. (A) Cell proliferation analyses. Cells were transfected with control or miR-181a plasmids, and at the noted time points post-transfection, 105 cells were counted and labeled with [3H] thymidine (2 Ci/mL) for 4 hours. Cells were transferred onto fiberglass filters and the radioactivity was read by a scintillation counter. Shown are the [3H] thymidine incorporation ratios of miR-181a to control from 3 independent experiments in triplicates per cell line. ABC-like DLBCL cell lines are noted in blue and GCB-like DLBCL cell lines in red. Statistical significance was determined by Student t test (****P < .0001) and the results are presented as mean ± SEM. (B) Anti–miR-181a cell proliferation rescue analyses. GCB-like (OCILY7 and OCILY19) and ABC-like (HBL1 and U2932) DLBCL cell lines were transfected with control or miR-181a plasmids. Twenty-four hours post-transfection, cells were counted and transfected again with either control or anti–miR-181a oligos. At 48 hours, cells were counted, labeled with [3H], and read as in panel A. Results are from 3 independent experiments in triplicates per cell line. Student t test (*P < .05) and the results are presented as mean ± SEM. (C) Cell viability FACS analyses in GCB-like (red) and ABC-like (blue) DLBCL cell lines. Three million cells per sample were transfected with control or miR-181a GFP plasmids. Four days post-transfection, the cells were stained with Annexin V–phycoerythrin (PE) and 7- aminoactinomycin D. The FACS analysis was performed on LSRFortessa-HTS, and the collected data were analyzed by FloJo software (Tree Star). The graphs depict cumulative results from 3 independent experiments showing the percent difference in live cells between the GFP+ miR-181a and GFP+ control transfected cells. Statistical significance was determined using two-way ANOVA (**P < .01) and the results are presented as mean ± SD. (D) Cell viability analyses in miR-181a inducible GCB-like and ABC-like DLBCL cell lines analyzed as in panel C. See also supplemental Figure 5.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/127/23/10.1182_blood-2015-11-680462/4/m_2856f5.jpeg?Expires=1767761748&Signature=NGTc3Yjd2cuFBmvCL0LS8LNcOiG97I6teEeEJIetPfznFFwOVH0e4zR8lPEejJ8lrBAEQxvsPPOlC~FIGqt7KvvEny0F0qGRcHpyuT1KkKkOO8hffCZsVrm3WLMSGWVitpaINVoKrn1PuA4njA-c56GCuRgbXRzAxl11Kf2lus5KXjnbn-PqbMKnr5WI319RUBOnB73irZvsmr3i7njh2smBoVgbk0KNEadAZgwlo3-L9RrxajD4fc0GIFlru1PQwD8RUpV3xqIE7qG-VFX2V0ffllnVV0I1CRvs4Nz9LugThvDywcta4ZluFmiufYjidu4ePBR51x36y3JDceOTpw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 6. CREL rescues the miR-181a–mediated cell death. (A) BCL2 cell proliferation rescue experiment. DOX-inducible U2932 cells were transfected with control empty vector or BCL2 plasmid lacking the 3′UTR (24 hours), and then induced to express control or miR-181a with DOX for 48 hours. At 72 hours post-transfection, 105 cells were counted and labeled with [3H] thymidine (2 Ci/mL) for 4 hours. The cells were then transferred onto fiberglass filters and the radioactivity was read by a scintillation counter. Shown are the [3H] thymidine incorporation ratios of miR-181a to control from 3 independent experiments in triplicates. Statistical significance was determined by Student t test (***P < .001) and the results are presented as mean ± SEM. Shown below is a western blot control for BCL2 overexpression in U2932 transfected cells (48 hours). Densitometry analyses of the protein bands were normalized to the loading control β-actin (NIH software; ImageJ), and the relative band density values in miR-181a (+) or BCL2 samples were compared with the control (set as 1) and are noted below the blot. (B) BCL2 cell viability rescue analysis in inducible U2932 cells transfected as in panel A above. The cells were washed and stained with Annexin V–FITC and with an irreversible dead-cells labeling dye, allophycocyanin-Cy7, and gated on the PE Texas Red+ populations. The graph depicts cumulative results from 3 independent experiments, showing the percent difference in live cells between the induced miR-181a and the control cells. Statistical significance was determined by Student t test (***P < .001) and the results are presented as mean ± SD. (C) NF-κB transcription factors cell viability rescue analysis as in panel B above. Shown is a representative FACS analysis (i). The graph depicts cumulative results from 3 independent experiments (ii), and a western blot control for the protein overexpression in U2932 cells at 48 hours (iii). See also supplemental Figure 6. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; ns, not significant; pcDNA, plasmid cytomegalovirus promoter DNA.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/127/23/10.1182_blood-2015-11-680462/4/m_2856f6.jpeg?Expires=1767761748&Signature=IUFlukIqEwLgggg0ZKHTqk-n85NgBt~JMX~Jq2riSEXsSXjeDNGUe5oKSyeeIEl5-iIrqDcZK8kOGphqaCge7d0jjEAW7xkkw8iFt6umlAfCD295~jWVRt2PzMH09rKSne7PCs3BnqIBApxHeZ2Jl4mvSg5hwjZ9EXLeSVn~YlLjEeGWhZ190BHII4nUY2ve6SwB~oGjterfY8iprVeL8ZuJsFg2YM3FDyN4gOxmhBN9DIgTcBCGAXD0RmKMYgtgQlg8wWTkk1zELDD-OGciLEgSXVxJK4~nILaY~bCrEIj0GQsMJ1h1pmD5seTQqDpiVG78YTgkFZZEn9yJFc19Fg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal