Abstract

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is not uncommon in cancer patients. Over the past 5 years, treatment of chronic HCV infection in patients with hematologic malignancies has evolved rapidly as safe and effective direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) have become the standard-of-care treatment. Today, chronic HCV infection should not prevent a patient from receiving cancer therapy or participating in clinical trials of chemotherapy because most infected patients can achieve virologic cure. Elimination of HCV from infected cancer patients confers virologic, hepatic, and oncologic advantages. Similar to the optimal therapy for HCV-infected patients without cancer, the optimal therapy for HCV-infected patients with cancer is evolving rapidly. The choice of regimens with DAAs should be individualized after thorough assessment for potential hematologic toxic effects and drug-drug interactions. This study presents clinical scenarios of HCV-infected patients with hematologic malignancies, focusing on diagnosis, clinical and laboratory presentations, complications, and DAA therapy. An up-to-date treatment algorithm is presented.

Introduction

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is the most common bloodborne infection in the United States, where the prevalence of HCV infection is estimated to be 1.0% to 1.5%.1 In patients with cancer, estimates of the prevalence of HCV infection range from 1.5% to 32%.2-6 Chronic HCV infection is mainly associated with hepatocellular carcinoma and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL).7,8

Management of HCV infection is more challenging in patients with hematologic malignancies than in patients without cancer because of a higher rate of progression of fibrosis, more rapid development of cirrhosis, increased viral titers, worse outcome, and exclusion from some cancer and/or antiviral treatments.9-11 Elimination of HCV from infected patients with hematologic malignancies has the potential for virologic, hepatic, and oncologic benefits (Table 1).9,12,13 The Web site http://www.hcvguidelines.org provides continuously updated guidelines for direct-acting antiviral (DAA) treatment of patients with HCV infection.

Benefits of HCV treatment in patients with hematologic malignancies

| Benefits of HCV treatment . |

|---|

| Infectious and hepatic |

| Prevention of long-term complications such as liver cirrhosis and end-stage liver disease |

| Prevention of hepatocellular carcinoma as a primary or secondary cancer in patients with chronic HCV infection |

| Improvement of long-term survival |

| Treatment of extrahepatic manifestations (cryoglobulinemia and fatigue) |

| Oncologic |

| Allowing patients access to multiple clinical trials of cancer chemotherapies, including trials of agents with hepatic metabolism |

| Prevention of some HCV-associated hematologic malignancies (eg, NHL) or decrease of the relapse rate of those malignancies |

| Cure of selected HCV-associated hematologic malignancies without chemotherapy |

| Benefits of HCV treatment . |

|---|

| Infectious and hepatic |

| Prevention of long-term complications such as liver cirrhosis and end-stage liver disease |

| Prevention of hepatocellular carcinoma as a primary or secondary cancer in patients with chronic HCV infection |

| Improvement of long-term survival |

| Treatment of extrahepatic manifestations (cryoglobulinemia and fatigue) |

| Oncologic |

| Allowing patients access to multiple clinical trials of cancer chemotherapies, including trials of agents with hepatic metabolism |

| Prevention of some HCV-associated hematologic malignancies (eg, NHL) or decrease of the relapse rate of those malignancies |

| Cure of selected HCV-associated hematologic malignancies without chemotherapy |

Clinical scenarios

Case 1

A 55-year-old man with a 30-year history of chronic HCV infection (genotype 2) was recently diagnosed with splenic marginal zone lymphoma. His HCV infection had never been treated because there had been no evidence of progressive hepatic fibrosis or portal hypertension. DAA therapy was recommended as first-line therapy before chemotherapy.

Discussion, case 1

This case raises several issues: (1) can some HCV-associated hematologic malignancies be cured with DAA therapy without chemotherapy? (2) after DAA therapy has induced a sustained virologic response (SVR), is there a risk of HCV recurrence following immunosuppressive chemotherapy? and (3) could antiviral therapy years ago have prevented the development of this lymphoma, and is chemoprevention a valid indication for DAA therapy in HCV-infected patients with no evidence of hepatic fibrosis?

Evidence that HCV infection may be causal in the development of lymphoma is based on several cases in which regression of lymphoma followed elimination of HCV.14 Most patients with HCV-associated NHL have mild liver disease at the time of lymphoma diagnosis,15 suggesting that DAA therapy should be initiated as early as possible after diagnosis of HCV infection, regardless of liver disease status, to eradicate HCV infection and thus, prevent extrahepatic manifestations such as NHL. Evidence for this strategy comes from a Japanese study in which the annual incidence of lymphoma was compared between 501 HCV-infected patients who had never received interferon (IFN)-based therapy and 2708 HCV-infected patients who had received IFN. The subsequent risk of lymphoma was ∼7 times higher in patients with persistent HCV infection as in patients with IFN-induced SVR. Among patients whose therapy eliminated HCV, there were no cases of lymphoma development by 15 years.16 Furthermore, several case series have shown regression of indolent lymphoma in HCV-infected patients treated with antiviral drugs.14 Current National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines on splenic marginal zone lymphoma recommend treatment of HCV without chemotherapy as first-line therapy for HCV-infected patients.17 The benefit of giving DAA therapy without chemotherapy as first-line therapy may extend to patients with other types of HCV-associated NHL (eg, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma18 ) or patients with HCV-associated NHL undergoing hematopoietic cell transplant (HCT).19

Some authors have reported detection of HCV RNA in hepatocytes and peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients who had achieved SVRs,20 but little is known about the risk of viral relapse following subsequent chemotherapy. In a study of 30 HCV-infected cancer patients, including 15 with hematologic malignancy, who achieved an SVR before cancer therapy, no patient had viral relapse after cancer therapy.21 The cancer therapies were as follows: rituximab, cyclophosphamide (CY), cisplatin, 5-fluorouracil, doxorubicin, melphalan, bortezomib, fludarabine, paclitaxel, sorafenib, lenalidomide, and vincristine (some patients received combination therapy).21

These findings indicate that HCV infection is curable in cancer patients and the risk of HCV recurrence is low once SVR has been achieved, even after chemotherapy-related immune suppression. These findings also emphasize the importance of identification and treatment of HCV infection before initiation of chemotherapy.21 Patients with evidence of fibrotic and necroinflammatory liver disease require monitoring of liver disease progression even when they have achieved an SVR.

Summary, case 1

HCV infection appears to contribute to some cases of NHL, and some patients with HCV infection and NHL can be cured with DAA therapy alone. Once an SVR has been achieved, the risk that subsequent chemotherapy will lead to recurrent HCV infection is negligible. Treatment of HCV infection may prevent the development of certain types of NHL.

Case 2

A 60-year-old woman was diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and was found to be HCV antibody (anti-HCV) positive with detectable HCV-RNA and evidence of genotype 1a infection. She had a history of unexplained abnormally high serum aminotransferase levels for over 20 years. There were no signs of cirrhosis or portal hypertension. Approximately 6 months after leukemia remission was achieved with chemotherapy, the patient was started on sofosbuvir and ledipasvir. Within 4 weeks of treatment with DAAs, serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels normalized, and HCV-RNA became undetectable. The patient achieved an SVR12 (undetectable HCV-RNA at 12 weeks after completion of therapy). She is undergoing periodic follow-up examinations to check for evidence of relapse while a donor search is underway.

Discussion, case 2

This case raises several important issues: (1) the importance of early diagnosis of HCV infection, (2) the importance of monitoring for virologic complications of HCV infection during chemotherapy, and (3) the optimal sequencing of DAA therapy and chemotherapy.

Among patients infected with HCV, those with hematologic malignancies, and especially patients who have undergone HCT, have a more rapid rate of fibrosis progression and a higher risk of developing cirrhosis than patients without cancer.22 Among patients with cancer, HCV screening and early diagnosis, assessment of liver fibrosis, and elimination of HCV will likely improve long-term outcomes.9 Groups for whom HCV screening is recommended include candidates for HCT,23 patients with hematologic malignancies,24 and other cancer patients as recommended in patients without cancer.1,23,25 HCV screening is recommended before starting selected chemotherapy agents (eg, rituximab and alemtuzumab) and before enrollment on clinical trials with investigational antineoplastic agents. Discovery of HCV infection in a patient newly diagnosed with a hematologic malignancy should prompt virologic tests and fibrosis assessments (Table 2).

Initial evaluation of HCV-infected patients with hematologic malignancies

| History and clinical findings . | Laboratory tests . | Virologic tests . | Imaging/staging studies . |

|---|---|---|---|

| History | Routine | HCV | Imaging |

| Alcohol abuse | Complete blood count, AST, ALT, total bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, albumin, PT/PTT/INR, BUN, creatinine | HCV-RNA quantitation | Abdominal sonography or computed tomography |

| Metabolic risk factors | HCV genotype | ||

| Vaccination status against HAV and HBV | |||

| Physical examination | Others | Coinfections | Noninvasive markers of fibrosis |

| Symptoms/signs of cirrhosis | α-fetoprotein | Anti-HAV | Vibration-controlled transient elastography* |

| GGT | HBsAg | Serum fibrosis panel* | |

| Cryoglobulins | Anti-HBs | ||

| Anti-HBc | |||

| Anti-HIV | |||

| Selected cases | Selected cases | Pathology | |

| Interleukin 28B polymorphism | HCV-resistance testing | Liver biopsy |

| History and clinical findings . | Laboratory tests . | Virologic tests . | Imaging/staging studies . |

|---|---|---|---|

| History | Routine | HCV | Imaging |

| Alcohol abuse | Complete blood count, AST, ALT, total bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, albumin, PT/PTT/INR, BUN, creatinine | HCV-RNA quantitation | Abdominal sonography or computed tomography |

| Metabolic risk factors | HCV genotype | ||

| Vaccination status against HAV and HBV | |||

| Physical examination | Others | Coinfections | Noninvasive markers of fibrosis |

| Symptoms/signs of cirrhosis | α-fetoprotein | Anti-HAV | Vibration-controlled transient elastography* |

| GGT | HBsAg | Serum fibrosis panel* | |

| Cryoglobulins | Anti-HBs | ||

| Anti-HBc | |||

| Anti-HIV | |||

| Selected cases | Selected cases | Pathology | |

| Interleukin 28B polymorphism | HCV-resistance testing | Liver biopsy |

anti-HAV, antibody to hepatitis A virus; anti-HBc, antibody to hepatitis B core antigen; anti-HBs, antibody to hepatitis B surface antigen; anti-HIV, antibody to HIV; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; GGT, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase; HAV, hepatitis A virus; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; HBV, hepatitis B virus; INR, international normalized ratio; PT, prothrombin time; PTT, partial thromboplastin time.

Sonography-based vibration-controlled transient elastography (FibroScan VCTE; Echosens, Paris, France) and serologic marker panels for detection of fibrosis have not been studied in HCV-infected patients with hematologic malignancies; thus, results should be interpreted with caution.

In HCV-infected cancer patients, ALT levels should be monitored during chemotherapy because immunocompromised cancer patients can experience acute exacerbation of chronic HCV infection (also known as hepatitis flare), which is indicated by a significant elevation of serum ALT levels over the baseline level.26 In a retrospective study of 308 HCV-infected patients treated for cancer, 11% developed an acute exacerbation of chronic HCV infection, defined as a threefold or greater increase in serum ALT level from baseline in the absence of infiltration of the liver by cancer, use of hepatotoxic medications, blood transfusion within 1 month of elevation of ALT level, or other hepatic viral infection.26 Acute exacerbation of HCV infection during chemotherapy prompted clinicians to discontinue chemotherapy in nearly half of infected patients.26 The diagnostic work-up to confirm acute exacerbation of HCV infection must consider a range of possibilities and take into account that multiple causes of liver inflammation can be present at the same time. In a patient who has undergone HCT, additional diagnoses to consider include the hepatitic presentation of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), infection with other viruses, drug-induced liver injury, and hypoxic hepatitis.27

HCV-infected cancer patients undergoing immunosuppressive therapy may also experience increased HCV replication (also known as HCV reactivation), which has been defined as an increase in HCV-RNA viral load of at least 1 log10 IU/mL over baseline after chemotherapy or immunosuppressive therapy26 (chronically infected patients have stable HCV-RNA levels that may vary by ∼0.5 log10 IU/mL).28 The increased replication of HCV and the resulting high blood titers of virus appear to be associated with a more indolent course than HBV reactivation11 ; there are only a few reports of deaths associated with increased HCV replication, some of them related to the development of fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis C (see case 5, to follow).29,30

Little is known about acute exacerbation and reactivation of HCV infection in patients with hematologic malignancies and HCT recipients, although some data were published recently.19,31-33 In general, in patients with hematologic malignancies and HCV infection, the ALT level should be evaluated at baseline and periodically during chemotherapy or immunosuppressive therapy to identify unusual cases of more severe hepatocellular injury or fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis C. Routine monitoring of HCV RNA is not recommended; however, HCV RNA should be measured in all patients at entry into care, and viral load should be monitored in patients receiving HCV treatment according to standard-of-care management for patients without cancer.12

Eradication of HCV may normalize liver function, allowing access to drugs that would otherwise be contraindicated, including agents with hepatic metabolism.34 SVR would prevent HCV reactivation and hepatic flare after chemotherapy, thus avoiding discontinuation or dose reduction of chemotherapy and possibly the risk of hepatic decompensation during cancer care.26 Longer-term benefits would include the prevention of progression to cirrhosis, reduction in the risk of second primary cancers (hepatocellular carcinoma and NHL),18,35 and improved survival of patients with these secondary cancers.19,36,37

The advent of DAAs has rendered IFN-containing regimens obsolete for treatment of HCV infection, and the benefits of DAA therapy outweigh the risks in HCV-infected patients with hematologic malignancies (Table 1).9,12,13 Contraindications to treatment with DAAs in HCV-infected patients with hematologic malignancies are shown in Table 3.12,38,39

Subgroups of HCV-infected patients with hematologic malignancies for whom DAA therapy is contraindicated

| The subgroups are as follows: . |

|---|

| Patients with uncontrolled hematologic malignancy or other comorbidities associated with a life expectancy of <12 months due to non–liver-related conditions* |

| Patients with moderate or severe hepatic impairment (Child-Pugh class B or C)† |

| Pregnant women and men whose female partners are pregnant if ribavirin is considered |

| Patients with major drug-drug interactions with chemotherapy or immunosuppressive agents that cannot be temporarily discontinued |

| Patients with known hypersensitivity or intolerance to drugs used to treat HCV |

| The subgroups are as follows: . |

|---|

| Patients with uncontrolled hematologic malignancy or other comorbidities associated with a life expectancy of <12 months due to non–liver-related conditions* |

| Patients with moderate or severe hepatic impairment (Child-Pugh class B or C)† |

| Pregnant women and men whose female partners are pregnant if ribavirin is considered |

| Patients with major drug-drug interactions with chemotherapy or immunosuppressive agents that cannot be temporarily discontinued |

| Patients with known hypersensitivity or intolerance to drugs used to treat HCV |

Extrapolated from recommendations in HCV-infected patients without cancer.12

While waiting for efficacy and safety data in infected patients with hematologic malignancies. Because liver transplantation is the only available treatment of decompensated cirrhosis,12,38 these patients should be managed by providers with expertise in that condition, ideally in a liver transplant center. Of note, incurable extrahepatic malignancies are considered a contraindication to listing for liver transplantation,39 therefore, some patients with hematologic malignancies may not be eligible for this intervention.

To improve the response to HCV therapy and avoid development of viral resistance, DAA therapy should not be interrupted or given intermittently. DAA-based regimens can be completed in 8 to 12 weeks in most patients with selected cases requiring up to 24 weeks of treatment,12,40 enabling eradication of HCV during chemotherapy-free periods. Severe adverse effects and hematologic toxic effects are uncommon (occurring in fewer than 5% of patients) in cancer patients receiving IFN-free or ribavirin-free DAA-containing regimens.19,41

As of 2016, we do not recommend simultaneous administration of chemotherapy and DAAs. However, preliminary data in a small group of cancer patients, including some with hematologic malignancies, showed that concomitant chemotherapy and DAA therapy is feasible.42 Because we have only a limited clinical understanding of drug-drug interactions and chemotherapy tolerability in HCV-infected patients, simultaneous therapies should be used with caution.

Summary, case 2

Elimination of HCV with DAAs, either before or after cancer therapy, has not been studied in randomized trials, but SVR could confer several benefits to patients with hematologic malignancies, particularly if the malignant disorder is driven by an HCV-related chronic inflammatory state. Short-term benefits of HCV eradication include normalization of liver function, prevention of HCV reactivation and hepatic flare after chemotherapy, and possibly better outcomes if an allogeneic transplant was carried out. Longer-term benefits of SVR would include prevention of progression to cirrhosis, reduction in the risk of second primary cancers, and improved survival.

Case 3

A 38-year-old man has AML in first remission. He is being considered for allogeneic HCT. His 44-year-old brother is HLA-matched and has chronic HCV infection but no signs of portal hypertension. An unrelated donor search has identified an HLA-matched 32-year-old woman who is anti-HCV negative.

Discussion, case 3

This case raises 2 questions: (1) can HCV be cleared from the matched sibling donor in a timely way so that the sibling can donate hematopoietic cells without risk of passing HCV to the patient? and (2) if treatment of the infected donor did not clear HCV, who would be the optimal donor, the HCV-infected HLA-matched sibling or an uninfected HLA-matched unrelated donor?

A 2015 report from the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation Task Force extensively covers the diagnosis and management of HCV infection in hematopoietic cell donors, and HCT candidates and recipients.23 Virtually all HCV-infected donors will transmit the virus to recipients.43 Case reports of HCV-infected marrow donors treated with IFN or ribavirin demonstrate that clearance of HCV from the bloodstream prevents passage of virus, an effect that does not require an SVR but just temporary cessation of viremia, during which marrow or peripheral blood is harvested.44,45 DAAs are very effective in clearing HCV and work rapidly; thus, when the best HLA-matched donor is HCV infected, treatment with DAAs should be instituted as early as possible.23,24 Most infected donors will attain undetectable HCV-RNA within 4 weeks of initiation of DAA therapy.46

If no uninfected HLA-matched donor is available and if time does not permit treatment of the infected donor to eliminate HCV from the infusion product, the use of an HCV-infected hematopoietic inoculum into an HCV-uninfected recipient is not contraindicated. The risk of dying from the underlying hematologic malignancy without HCT far outweighs the risk of acquiring potentially curable HCV.23 However, the donor should be assessed for advanced liver disease, extrahepatic manifestations of HCV (eg, NHL), and coinfections (eg, HIV) that might contraindicate donation.23 Using an HCV-infected sibling donor is preferable to an HLA-matched unrelated donor, because the natural history of HCV infection in allografted patients is usually benign in the early years following HCT.47 After transplant, DAA therapy can be given to the recipient. For most patients with early hematologic malignancy, survival after HCT with hematopoietic cells donated by an HLA-matched sibling is superior to survival after an unrelated-donor transplant.48

Summary, case 3

An HCV-infected donor should not be an absolute contraindication for HCT.23 The risk of passage of virus from an infected donor can be greatly reduced by DAA therapy that results in undetectable HCV-RNA. When time does not permit sufficient antiviral treatment of an HLA-matched sibling donor to achieve undetectable HCV-RNA, using an HCV-infected, HLA-matched sibling donor will usually yield better oncologic outcomes than using an HLA-matched uninfected and unrelated donor.

Case 4

A 62-year-old man presented with an abdominal mass. At operation, biopsy revealed a T-cell lymphoma; also noted were ascites and a nodular-appearing liver with chronic hepatitis, fibrosis, and regenerative nodules on histopathologic examination. Laboratory studies revealed the following values: total serum bilirubin, 1.3 mg/dL; serum ALT, 122 U/L; alkaline phosphatase, 87 U/L; albumin, 2.4 mg/L; international normalized ratio, 1.6; platelets, 92 000/mm3; hepatitis B surface antigen, negative; and anti-HCV, positive. The patient’s cirrhosis was classified as Child-Turcotte-Pugh class B.

Discussion, case 4

This case raises 2 issues: (1) the impact of cirrhosis on the disposition of chemotherapy drugs, and (2) the risk of liver failure due to cancer therapy or drugs used in supportive care.

Dosing of drugs (including chemotherapy) in patients with cirrhosis is an inexact science, in part because of the complexity of drug disposition in the liver, which depends on hepatic perfusion, extraction, metabolism, excretion, and differences in protein binding of individual drugs.49,50 No single method allows estimation of the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of a drug in an individual patient with liver dysfunction. Dose adjustments are often necessary in patients with cholestatic liver injury,51,52 but adjustments are usually not necessary in patients with chronic HCV infection, except in the case of certain high-dose myeloablative conditioning regimens for HCT, for which the risk of fatal sinusoidal obstruction syndrome is almost 10 times as high in patients with chronic HCV infection as in patients without HCV infection.53-55 The most accurate method of dose adjustment is therapeutic drug monitoring, in which the dose is personalized in real time according to an individual patient’s clearance of a drug to achieve the target plasma exposure.56-58 In patients for whom HCT is planned, therapeutic monitoring of busulfan (BU) is widely used to avoid graft rejection and relapse of some malignant disorders (low exposure) and toxic effects (high exposure).59,60 For drugs with unpredictable pharmacokinetics (eg, CY61 and melphalan62 ), therapeutic drug monitoring is the only logical approach to dosing, not only in patients with cirrhosis but also in patients with normal liver function. However, clinical use of therapeutic drug monitoring is for the most part limited to specialized centers. Therefore, most patients with cirrhosis or cholestasis must rely on other dose-adjustment methods.

Another method for dose adjustment involves triaging cirrhotic patients into Child-Turcotte-Pugh classes A, B, or C (http://www.hepatitisc.uw.edu/page/clinical-calculators/ctp). For many chemotherapy drugs, pharmacokinetic information for patients with Child-Turcotte-Pugh class A or B cirrhosis is available from the drug manufacturer; such information is based on the US Food and Drug Administration and European Medicines Agency guidance on determining the pharmacokinetics of study drugs in patients with impaired hepatic function.63,64 For patients with class A or B cirrhosis, dose reductions of 50% to 75% are often recommended, depending on whether the drug in question is a high liver-extraction drug (extraction dependent on hepatic perfusion) or a low liver-extraction drug (extraction dependent on hepatocyte metabolism and elimination).49 For high-extraction drugs, dose reductions are needed. For low-extraction drugs, the degree of protein binding affects dose adjustment, with highly bound drugs not needing a dose reduction. Drugs with low protein binding are dose reduced in parallel with the estimated reduction in hepatic functional reserve (based on the Child-Turcotte-Pugh class). Chemotherapy dose-adjustment recommendations have been published that are based on findings of serum liver tests, mostly serum bilirubin levels.51,52,64 The main goals of dose adjustment are to avoid systemic side effects from toxic plasma concentrations and to provide adequate drug concentrations when low exposure is anticipated.

If the patient in this case were scheduled for HCT, the questions would be as follows: what conditioning regimen could this patient with cirrhosis tolerate? Should DAA therapy be attempted before transplant? Is mycophenolate mofetil contraindicated as GVHD prophylaxis?

High-dose myeloablative regimens containing sinusoidal endothelial cell toxins (CY, etoposide, thiotepa, melphalan, gemtuzumab ozogamicin, and total body irradiation >12 Gy) have been largely abandoned in patients with chronic hepatitis (HCV infection, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, or alcoholic hepatitis) in favor of less liver-toxic regimens.53,54 If there is an imperative to use a CY-based regimen in a cirrhotic patient, the dose should be 90 mg/kg to 100 mg/kg (instead of 120 mg/kg), dose-adjusted if possible, and either separated in time from BU or given first in order (eg, CY/targeted BU).61,65,66 Reduced-intensity regimens may avoid sinusoidal injury, but cirrhotic patients remain at risk for liver failure from GVHD, infection-related cholestasis, hypoxic hepatitis, tumor infiltration, and drug-induced liver injury resulting from drugs used in supportive care, including herbal therapies.54,67-70 Ascitic fluid should be drained prior to administration of hydrophilic drugs such as fludarabine and methotrexate,54 and if mycophenolate mofetil is used, it should be dose-adjusted if the serum albumin level is low.71 Supportive care should include ursodiol for prevention of cholestatic liver injury, antibiotics to prevent bacterial translocation during neutropenia, and attention to portal pressures and hepatorenal syndrome.

Drug-induced liver injury resulting from anticancer drugs has been reviewed elsewhere.64,68,72 HCV is a risk factor for drug-induced liver injury from some drugs, and there are case reports of increased viral titers and more severe HCV infection after recovery of immunity following immunosuppressive chemotherapy.30,73,74 A cirrhotic patient would be at greater risk than someone without cirrhosis for worsening HCV-related liver inflammation. Treatment of HCV-infected cirrhotic patients with DAAs can be successful in achieving an SVR, but should probably be deferred until the course of hematologic malignancy is clear.

Summary, case 4

HCV-infected patients with cirrhosis are challenging to treat because of the difficulty of determining proper doses of cytotoxic and immunosuppressive drugs, and the increased risk of liver failure as a result of any number of hepatic insults. Questions about dosing of chemotherapy drugs in cirrhotic patients are best addressed by experienced pharmacologists.

Case 5

A 56-year-old man with AML in first complete remission was treated with a reduced-intensity conditioning regimen, and unrelated cord blood transplant with tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil for GVHD prophylaxis. Before transplant, he was found to be infected with HCV genotype 1a and the rs12979860 genotype (previously known as interleukin-28B) TT. Before transplant, findings on liver tests and imaging were normal. At day 80 after transplant, the patient developed nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, elevated values on liver function tests (ALT, 139 U/L; total serum bilirubin, 3.9 mg/dL), confusion, and coagulopathy. Endoscopic biopsy confirmed gut GVHD, and the patient was started on prednisone 1 mg/kg per day. By day 96 after transplant, the patient was more deeply jaundiced; a liver biopsy showed fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis. Treatment with the combination of ombitasvir, paritaprevir, ritonavir, dasabuvir, and weight-based ribavirin was considered, but the risk of drug-drug interactions was thought to be high (eg, increased level of tacrolimus with resulting central nervous system toxic effects and peripheral neuropathy).

Discussion, case 5

This case raises several important questions: (1) is it safe for an HCV-infected patient to undergo HCT? (2) what serious complications of HCV infection can be expected after HCT? and (3) how important is monitoring for drug-drug interactions in HCV-infected patients receiving DAA therapy?

This patient developed fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis, a rare and potentially fatal complication characterized by periportal fibrosis, ballooning degeneration of hepatocytes, prominent cholestasis, and paucity of inflammation related to a high intracellular load of either HBV or HCV and viral protein.29,75,76 Fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis has been described after HCT, organ transplant, and some chemotherapy regimens.29,77-80 In an HCT recipient, fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis C must be differentiated from other manifestations of cholestatic liver injury (eg, GVHD, drug-induced liver injury, and cholestasis of infection).54

In both the liver transplant and HCT settings, use of mycophenolate mofetil has been linked to development of fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis C; thus, this drug should probably not be used in HCV-infected patients.29,81 In the HCT setting, DAAs against HCV would likely reduce the burden of intracellular virus29 and reduce the mortality rate of fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis C, as has been observed with successful DAA therapy of fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis C in the liver transplant setting.82-84 In a parallel situation, the frequency of fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis B in HCT recipients has plummeted since the introduction of pre-emptive use of lamivudine or entecavir.85

When possible, DAA therapy for HCV-infected HCT candidates should be completed before HCT. If DAA therapy cannot be completed until after HCT, DAA therapy can be deferred until after immune reconstitution except in patients who develop fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis C and probably in cases of severe HCV reactivation post-HCT.33

The drawback of deferring DAA therapy for HCV infection until after HCT is the propensity of DAAs for drug interactions, including altered disposition of several drugs commonly used in HCT patients.23 The drugs most impacted by DAAs are components of conditioning regimens, calcineurin inhibitors, and sirolimus, but review of the isoenzymes responsible for drug metabolism suggests that many of the drugs used in supportive care are similarly affected by DAAs.23 Current databases (http://www.hep-druginteractions.org and Lexicomp Online) should be consulted along with the product prescribing information to ensure the safety of delivering DAAs together with medications such as acid reducers, antidepressants, antihypertensives, phosphodiesterase inhibitors, novel oral anticoagulants, macrolide antibiotics, and HMG Co-A inhibitors. Some experts advocate waiting for 6 months after HCT to start DAA therapy, in order to allow tapering of immunosuppressive agents and GVHD prophylaxis; this practice might result in higher SVR rates and avoid drug-drug interactions with calcineurin inhibitors.23 The majority of HCV-infected HCT recipients do not have an adverse course in the years following HCT, despite greatly increased titers of circulating virus following conditioning therapy.47

It is not currently known whether the high rates of HCV clearance with DAAs in the general population and in organ transplant patients can be replicated in HCT patients in the early post-HCT period, because full immune reconstitution does not occur until more than 1 year after allogeneic HCT, and both immunosuppressive therapy and GVHD will delay the return of immunity.86,87 Preliminary data show that DAAs are safe and effective (SVR rate, 85%) in HCV-infected HCT recipients.19

The choice of DAA regimen should be guided by several factors (eg, the patient’s prior antiviral treatment, HCV genotype, and degree of liver disease) and should be individualized after thorough assessment for potential hematologic toxic effects and drug-drug interactions. Several articles have been recently published on drug interactions with DAAs.88-91 Recommended dosage adjustments for patients with renal impairment are now available.12 For currently approved DAAs in 2016, no dose adjustments are necessary for patients with liver dysfunction, including those with decompensated cirrhosis.12,84 This issue has to be re-visited with each new DAA that is approved; and HCV guidelines and the manufacturer’s package insert should be consulted.

Summary, case 5

Transplant physicians must be aware of the risk of fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis C, especially in patients whose GVHD prophylaxis includes mycophenolate mofetil or enteric-coated mycophenolic acid. The role of DAAs in patients undergoing HCT has yet to be defined, but on the basis of preliminary data, we envision eliminating HCV before transplant or administering DAAs after transplant to prevent development of fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis C and other adverse effects of HCV infection. Patients with a diagnosis of fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis C after HCT should receive DAA therapy. Close attention to drug-drug interactions will be necessary when DAAs are prescribed to allograft recipients.

Conclusion

HCV is now curable by DAAs in most patients, including those with hematologic malignancies. Elimination of HCV from infected patients offers potential virologic, hepatic, and oncologic benefits.

HCV infection should not contraindicate cancer therapy, and patients with chronic HCV infection and hematologic malignancies should not be excluded from clinical trials of chemotherapy or antiviral therapies. However, hepatologists and infectious disease specialists with experience in treating HCV should participate in the diagnostic work-up, monitoring, and treatment of infected patients.

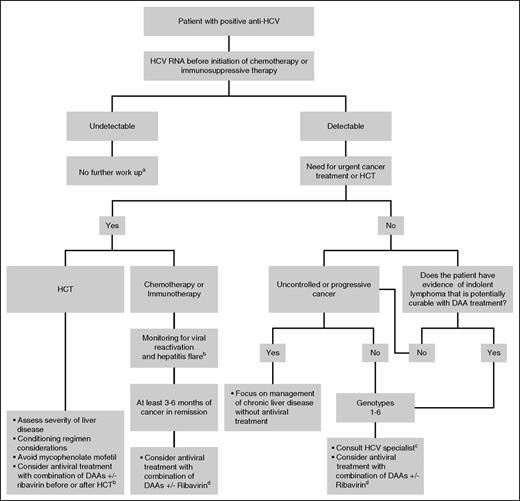

Using a standardized approach since 2009, we demonstrated that HCV therapy is feasible in many cancer patients.92 In general, the DAA combinations recommended for cancer patients mimic those used for patients without cancer.12 DAAs used to treat HCV in 2016 and their most common side effects are shown in Table 4.93-99 Our management algorithm for HCV-infected patients with hematologic malignancies is depicted in Figure 1. The optimal therapy for HCV-infected patients with cancer is evolving rapidly and will continue to evolve as new DAAs are approved and as more studies are reported.

DAAs used to treat HCV in 2016 and their most common side effects

| DAAs and side effects . |

|---|

| Sofosbuvir |

| Fatigue and headaches |

| Simeprevir |

| Fatigue,* headaches,* nausea,*† rash (including photosensitivity),† and pruritus† |

| Daclatasvir* |

| Fatigue, headaches, anemia, and nausea |

| Ombitasvir-paritaprevir-ritonavir, and dasabuvir |

| Fatigue, nausea,‡ pruritus,‡ other skin reactions (eg, rash, erythema, and eczema), insomnia,‡ and asthenia |

| Ledipasvir-sofosbuvir |

| Fatigue, headache, and asthenia |

| Elbasvir-grazoprevir |

| Fatigue, headache, nausea, and anemia‡ |

| Sofosbuvir-velpatasvir |

| Headache, fatigue, anemia,‡ nausea,‡ headache, insomnia,‡ and diarrhea‡ |

| DAAs and side effects . |

|---|

| Sofosbuvir |

| Fatigue and headaches |

| Simeprevir |

| Fatigue,* headaches,* nausea,*† rash (including photosensitivity),† and pruritus† |

| Daclatasvir* |

| Fatigue, headaches, anemia, and nausea |

| Ombitasvir-paritaprevir-ritonavir, and dasabuvir |

| Fatigue, nausea,‡ pruritus,‡ other skin reactions (eg, rash, erythema, and eczema), insomnia,‡ and asthenia |

| Ledipasvir-sofosbuvir |

| Fatigue, headache, and asthenia |

| Elbasvir-grazoprevir |

| Fatigue, headache, nausea, and anemia‡ |

| Sofosbuvir-velpatasvir |

| Headache, fatigue, anemia,‡ nausea,‡ headache, insomnia,‡ and diarrhea‡ |

Most common adverse reactions reported in combination with sofosbuvir and ribavirin.

Most common adverse reactions reported with in combination with pegylated IFN-alfa and ribavirin.

Most common adverse reactions reported in combination with ribavirin.

Treatment algorithm for patients with hematologic malignancies and chronic HCV infection in 2016.aPatient had either spontaneous resolution of acute HCV, false positive anti-HCV, or sustained virologic response posttreatment; bSee text; cSpecialist on infectious diseases, hepatology, or gastroenterology; and dAs recommended in selected cases for patients without cancer as of July 2016.

Treatment algorithm for patients with hematologic malignancies and chronic HCV infection in 2016.aPatient had either spontaneous resolution of acute HCV, false positive anti-HCV, or sustained virologic response posttreatment; bSee text; cSpecialist on infectious diseases, hepatology, or gastroenterology; and dAs recommended in selected cases for patients without cancer as of July 2016.

Authorship

Contribution: H.A.T. and G.B.M. wrote the manuscript, and both authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: H.A.T. is or has been the principal investigator for research grants from Gilead Sciences, Merck & Co., Inc., and Vertex Pharmaceuticals, with all funds paid to MD Anderson Cancer Center. H.A.T. also is or has been a paid scientific advisor for Gilead Sciences, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Merck & Co., Inc., Vertex Pharmaceuticals, Genentech, Novartis, Astellas Pharma, Pfizer Inc., and Theravance Biopharma, Inc.; the terms of these arrangements are being managed by MD Anderson Cancer Center in accordance with its conflict-of-interest policies. G.B.M. declares no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Harrys A. Torres, Department of Infectious Diseases, Infection Control and Employee Health, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, 1515 Holcombe Blvd, Unit 1460, Houston, TX 77030; e-mail: htorres@mdanderson.org.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Stephanie Deming, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, for editorial assistance.