Abstract

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) carries a poor prognosis across age groups. In children, AML has become the leading cause of leukemia mortality, with only 60% of cases securing long-term remission. In adults, outcomes are far worse, with 5 year survival approaching 24%. The mutational and transcriptional characterization of AML1has not yet translated into improved outcomes for most patients.

The TARGET AML project is an effort of Children's Oncology Group (COG) and the National Cancer Institute to characterize molecular abnormalities in pediatric AML. 197 cases were selected for whole genome sequencing (WGS) of diagnostic specimens, 284 cases for mRNA sequencing, 289 cases for DNA methylation arrays, and 721 cases for targeted sequencing (182 assayed by WGS). Most patients (93%) were uniformly treated on COG study AAML0531 or AAML03P1. The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) AML project1characterized 177 comparable adult AMLs with identical assays.

DNA methylation changes radically during differentiation of blood cells2, and recurrent pre-leukemic mutations in adult AML3affect DNA methylation and chromatin modifiers. We thus investigated whether differences in cell-of-origin, immune signalling, and regulatory aberrations were captured by focal or regional differences in DNA methylation, within or between adult and pediatric AML patients.

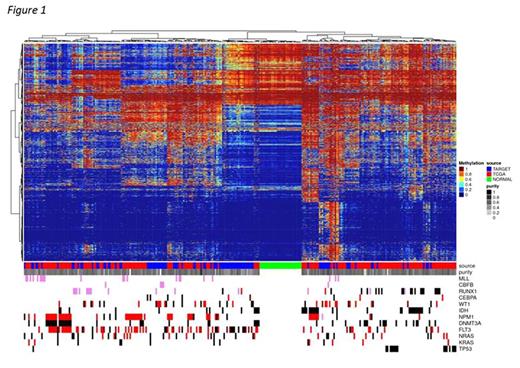

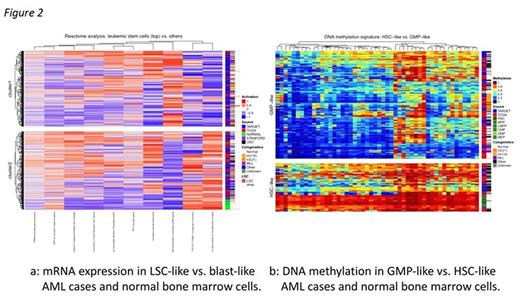

In cytogenetically similar TARGET and TCGA AML cases, striking differences in DNA methylation emerge (fig. 1). Pediatric FLT3-mutant AMLs dominate a cluster with normal-progenitor-like DNA methylation. Mutant DNMT3A, RUNX1, and TP53, which selectively favor preleukemic hematopoietic stem cells3,4,5 (HSCs), are common in adult AML, rare in pediatric AML, and tend towards HSC-like hypermethylation. Transcriptional & epigenetic signatures of the cell of origin persist even after leukemic transformation6. Thus we sought to identify the most likely cell of origin for each case. Previous studies of mRNA7 and DNA methylation8 differences in HSCs and progenitor cells (HSPCs), leukemic stem cells (LSCs), and AML blasts allowed us to model these differences in TCGA and TARGET AMLs. RNAseq results revealed many LSC-like cases with aberrant β-catenin signaling and TP53 regulation, distinct from blasts and normal HSPCs (fig. 2a). DNA methylation segregated cases resembling granulocyte/monocyte progenitors (GMPs) from those resembling other HSPC subsets (fig. 2b). DNMT3A mutants strongly associated with HSC/LSC-like mRNA expression, as did most MLL-rearranged AMLs. Nearly all TP53 and RUNX1 mutants presented LSC-like mRNA expression and retained HSC-like methylomes. These results suggest that decades of selective HSC attrition enable cooperating adult-specific mutations to initiate leukemia, while the timescales in pediatric AML favor fusion genes capable of transforming progenitors as well as HSCs.

With matched mRNA expression & DNA methylation data from 256 TARGET cases and 156 TCGA cases, we found over 100 genes where DNA methylation accompanied loss of transcription (silencing) in AML but not in normal HSPCs (fig. 3a). Many such genes lie in regions affected by recurrent copy number aberrations, most notably chromosome arms 5q and 19q. Recurrently mutated or deleted genes such as DNMT3A, TET2, SPRY4, and CDKN2A/B are silenced, some mutually exclusively with mutations or CNV. Functional enrichment analyses of silenced genes with DAVID9revealed 4 clusters: NK-cell signaling, innate immune response regulation, transcriptional regulation, and (on chromosome 19q) zinc finger genes involved in Toll-like receptor signaling. Some silencing co-occurs with specific molecular features, but no event was perfectly predicted by any molecular or cytogenetic feature (fig. 3b).

Drug-gene interaction mining with DGIDb10 suggests silencing may inform treatment. Silencing of the mitotic checkpoint gene CHFR may confer sensitivity to microtubule inhibitors11, silencing of MGMT suggests greater benefit from alkylating agents12, and demethylating agents may benefit cases with silenced immune response13. Biomarker driven clinical trials will be needed to evaluate these and other markers in pediatric and adult AML, but evidence of independent genetic and epigenetic evolution in AML14supports their continued investigation.

This work is dedicated to the late Robert J. Arceci, without whom none of this would have been possible.

No relevant conflicts of interest to declare.

Author notes

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal