Key Points

Circulating tumor DNA can monitor disease and predict treatment failure by tracking driver mutations and karyotypic abnormalities in MDS.

Abstract

The diagnosis and monitoring of myelodysplastic syndromes (MDSs) are highly reliant on bone marrow morphology, which is associated with substantial interobserver variability. Although azacitidine is the mainstay of treatment in MDS, only half of all patients respond. Therefore, there is an urgent need for improved modalities for the diagnosis and monitoring of MDSs. The majority of MDS patients have either clonal somatic karyotypic abnormalities and/or gene mutations that aid in the diagnosis and can be used to monitor treatment response. Circulating cell-free DNA is primarily derived from hematopoietic cells, and we surmised that the malignant MDS genome would be a major contributor to cell-free DNA levels in MDS patients as a result of ineffective hematopoiesis. Through analysis of serial bone marrow and matched plasma samples (n = 75), we demonstrate that cell-free circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) is directly comparable to bone marrow biopsy in representing the genomic heterogeneity of malignant clones in MDS. Remarkably, we demonstrate that serial monitoring of ctDNA allows concurrent tracking of both mutations and karyotypic abnormalities throughout therapy and is able to anticipate treatment failure. These data highlight the role of ctDNA as a minimally invasive molecular disease monitoring strategy in MDS.

Introduction

Current diagnostic and prognostic algorithms in myelodysplastic syndromes (MDSs) rely heavily on peripheral blood (PB) counts and bone marrow (BM) morphology,1-3 which often have interobserver variability.4 Recurrent chromosomal aberrations have helped refine current MDS prognostic models,1,2,5 and more recently, the sequencing of MDS cancer genomes has also identified several recurrent mutations6-12 that give prognostic insights at diagnosis.7,8,11-15 However, there is little evidence of how the clonal and subclonal architecture is influenced by therapy.

Hypomethylating agents such as azacitidine and decitabine remain the mainstay of MDS treatment.16,17 However, response may take months to achieve, and only half of patients respond to therapy.18 Repeated BM biopsies to monitor response can be invasive, resource-demanding, and associated with procedure-related complications. These limitations have, in part, compromised our ability to more regularly assess response to therapy and study clonal evolution in MDS. In this regard, we assessed the role of cell-free circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) as a novel and minimally invasive biomarker to monitor therapeutic response and clonal evolution in MDSs.

Study design

Serial BM (n = 89) and plasma samples (n = 83) were collected from 12 patients with MDS who received azacitidine and eltrombopag as part of a phase 1 clinical trial (Table 1). Targeted deep sequencing (TS) was performed on DNA derived from BM and plasma using a customized panel of 55 genes known to be recurrently mutated in MDS and acute myeloid leukemia (see supplemental Table 1, available on the Blood Web site). Sequencing of BM samples identified putative driver mutations in 10 of 12 patients (Figure 1A). Digital polymerase chain reaction (dPCR) was performed to validate the TS results. Quantification of mutant allele fraction (MAF) showed excellent correlation (supplemental Figure 1A) between TS and dPCR.

Baseline clinical and molecular characteristics of the patient cohort

| Patient information . | Genomic information . | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient . | Age (y) . | Sex . | MDS subtype (WHO 2008 classification) . | . | Duration of azacitidine therapy (d) . | Best response (IWG criteria) . | Outcome at last follow-up (IWG criteria) . | Karyotype . | Mutations detected at baseline . | BM MAF at baseline (%) . | Detected in plasma . | ||

| R-IPSS (score/category) . | Gene . | AA change . | COSMIC ID . | ||||||||||

| AZA001 | 72 | M | RAEB-1 | 3.5 /intermediate | 160 | SD | SD | Normal | IDH2 | R140Q | COSM41590 | 40.5 | Yes |

| AZA003 | 68 | M | RAEB-2 | 6.5/very high | 311 | CR-M | PD | t(11,17) | SRSF2 | P95_R102del(#) | COSM146289 | 87.4 | Yes |

| RUNX1 | Y196Nfs17(#) | 29.7 | Yes | ||||||||||

| AZA004 | 71 | M | RAEB-2 | 6.5/very high | 456 | CR-M | CR-M | Normal | TET2 | D1376V | 9.4 | Yes | |

| TET2 | N1890I | 30.8 | Yes | ||||||||||

| AZA005 | 67 | M | RCMD | 3/low | 543 | HI-P | HI-P | Normal | TET2 | Q323*(#) | COSM132895 | 23.7 | Yes |

| TET2 | V1718L | COSM41742 | 18 | No | |||||||||

| SRSF2 | P95H | COSM211504 | 23.8 | Yes | |||||||||

| AZA006 | 82 | M | RAEB-2 | 4/intermediate | 358 | CR-M | CR-M | Del Y | |||||

| AZA007 | 73 | M | RCUD | 2/low | 701 | HI-P | PD | Normal | SRSF2 | P95H | COSM211504 | 39.4 | Yes |

| KRAS | A59G* | COSM28518 | 6.2 | Yes | |||||||||

| AZA008 | 81 | M | RAEB-2 | 6/high | 683 | CR-M | PD | Trisomy 8 | ASXL1 | K1034Efs12(#) | 9.2 | Yes | |

| AZA009 | 70 | F | RAEB-1 | 5/high | 407 | SD | PD | Trisomy 8 | NRAS | G13D | COSM573 | 2.2 | Yes |

| AZA011 | 67 | M | RCMD | 2.5/low | 1492 | CR-P | CR-P | Del 9q | TET2 | P761Lfs52 | COSM211689 | 46.5 | Yes |

| U2AF1 | S34F | COSM166866 | 50.4 | Yes | |||||||||

| CBL | H398Y | COSM34075 | 43.1 | Yes | |||||||||

| AZA013 | 67 | M | Hypoplastic MDS (RCMD) | 3.5 /intermediate | 105 | SD | PD | Normal | |||||

| AZA014 | 75 | M | RAEB-1 | 7/very high | 424 | HI-N | PD | Trisomy 8 | RUNX1 | R166Q(#) | COSM36055 | 59.8 | Yes |

| Trisomy 21 | U2AF1 | S34Y | COSM146287 | 60.5 | Yes | ||||||||

| KRAS | G12S | COSM517 | 12.4 | Yes | |||||||||

| AZA015 | 74 | M | RAEB-2 | 6.5/very high | 347 | CR-M | PD | Normal | U2AF1 | Q157P(#) | COSM211534 | ND | Yes |

| Patient information . | Genomic information . | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient . | Age (y) . | Sex . | MDS subtype (WHO 2008 classification) . | . | Duration of azacitidine therapy (d) . | Best response (IWG criteria) . | Outcome at last follow-up (IWG criteria) . | Karyotype . | Mutations detected at baseline . | BM MAF at baseline (%) . | Detected in plasma . | ||

| R-IPSS (score/category) . | Gene . | AA change . | COSMIC ID . | ||||||||||

| AZA001 | 72 | M | RAEB-1 | 3.5 /intermediate | 160 | SD | SD | Normal | IDH2 | R140Q | COSM41590 | 40.5 | Yes |

| AZA003 | 68 | M | RAEB-2 | 6.5/very high | 311 | CR-M | PD | t(11,17) | SRSF2 | P95_R102del(#) | COSM146289 | 87.4 | Yes |

| RUNX1 | Y196Nfs17(#) | 29.7 | Yes | ||||||||||

| AZA004 | 71 | M | RAEB-2 | 6.5/very high | 456 | CR-M | CR-M | Normal | TET2 | D1376V | 9.4 | Yes | |

| TET2 | N1890I | 30.8 | Yes | ||||||||||

| AZA005 | 67 | M | RCMD | 3/low | 543 | HI-P | HI-P | Normal | TET2 | Q323*(#) | COSM132895 | 23.7 | Yes |

| TET2 | V1718L | COSM41742 | 18 | No | |||||||||

| SRSF2 | P95H | COSM211504 | 23.8 | Yes | |||||||||

| AZA006 | 82 | M | RAEB-2 | 4/intermediate | 358 | CR-M | CR-M | Del Y | |||||

| AZA007 | 73 | M | RCUD | 2/low | 701 | HI-P | PD | Normal | SRSF2 | P95H | COSM211504 | 39.4 | Yes |

| KRAS | A59G* | COSM28518 | 6.2 | Yes | |||||||||

| AZA008 | 81 | M | RAEB-2 | 6/high | 683 | CR-M | PD | Trisomy 8 | ASXL1 | K1034Efs12(#) | 9.2 | Yes | |

| AZA009 | 70 | F | RAEB-1 | 5/high | 407 | SD | PD | Trisomy 8 | NRAS | G13D | COSM573 | 2.2 | Yes |

| AZA011 | 67 | M | RCMD | 2.5/low | 1492 | CR-P | CR-P | Del 9q | TET2 | P761Lfs52 | COSM211689 | 46.5 | Yes |

| U2AF1 | S34F | COSM166866 | 50.4 | Yes | |||||||||

| CBL | H398Y | COSM34075 | 43.1 | Yes | |||||||||

| AZA013 | 67 | M | Hypoplastic MDS (RCMD) | 3.5 /intermediate | 105 | SD | PD | Normal | |||||

| AZA014 | 75 | M | RAEB-1 | 7/very high | 424 | HI-N | PD | Trisomy 8 | RUNX1 | R166Q(#) | COSM36055 | 59.8 | Yes |

| Trisomy 21 | U2AF1 | S34Y | COSM146287 | 60.5 | Yes | ||||||||

| KRAS | G12S | COSM517 | 12.4 | Yes | |||||||||

| AZA015 | 74 | M | RAEB-2 | 6.5/very high | 347 | CR-M | PD | Normal | U2AF1 | Q157P(#) | COSM211534 | ND | Yes |

MAF based on dPCR. MAF based on TS are marked with (#).

CR-M, complete response, marrow; CR-P, complete response, PB; d, days; Del, deletion; F, female; HI-N, hematological improvement, neutrophils; HI-P, hematological improvement, platelets; IWG, International Working Group; M, male; ND, not determined; PD, progressive disease; RAEB, refractory anemia with excess blasts; RCMD, refractory cytopenia with multilineage dysplasia; R-IPSS, Revised International Prognostic Scoring System; SD, stable disease; WHO, World Health Organization; y, years.

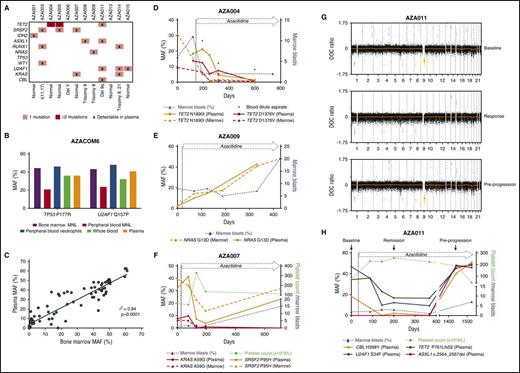

ctDNA as a disease monitoring strategy in MDS. (A) Mutations and cytogenetic abnormalities present among all patients recruited to the azacitidine + eltrombopag study. (B) MAF measured dPCR of a TP53 P177R and U2AF1 Q157P gene mutation in BM MNL, PB MNL, PB neutrophils, plasma ctDNA, and whole-blood DNA from a patient with high-grade MDS. The patient had no circulating blasts in the PB detected by morphology. BM morphology revealed multilineage dysplasia with an excess of myeloblasts (11% of nucleated cells). (C) Correlation between MAF measured by dPCR between BM and plasma ctDNA across 75 matched time points (r2 = 0.84; P < .0001). (D) Case AZA004. Serial comparison of the MAF of TET2 N1890I and TET2 D1376V mutation by dPCR between BM and plasma ctDNA. The patient had MDS with a classification of RAEB-2, which responded to azacitidine and eltrombopag therapy by a reduction in BM myeloblast percentage. At various time points (day 193, day 318, and day 599), poor-quality blood-dilute aspirate samples were obtained (denoted by *). At these times, plasma ctDNA MAF was higher than BM MAF of the TET2 N1890I and TET2 D1376V mutation. There was also severe neutropenia at these time points (neutrophils = 0.13, 0.15, and 0.16 × 109/L, respectively). (E) Case AZA009. Serial MAF of a NRAS G13D mutation by dPCR of BM and plasma ctDNA. The patient had RAEB-1 and stable disease after azacitidine and eltrombopag therapy represented by a persistent but stable excess of BM blasts. There was eventual progression at day 407 of therapy to acute myeloid leukemia. (F) Case AZA007. Serial MAF of a KRAS A59G and SRSF2 P95H mutation by TS of BM and plasma ctDNA, respectively. The patent had refractory cytopenia with unilineage dysplasia with severe thrombocytopenia, which responded initially to azacitidine and eltrombopag therapy. The patient eventually progressed with an increase in BM myeloblast percentage. Of note, the SRSF2 mutation, despite being reduced, still remained detectable in ctDNA at all time points sampled. At the time of disease progression, the MAF of the SRSF2 mutation in plasma had clearly increased, while the KRAS mutation remained undetectable. (G) Depth of coverage (DOC) log2 ratio plots from low-coverage whole-genome sequencing (LC-WGS) of plasma in patient AZA011. At “baseline” (top), the plot shows the presence of a loss of copy number at chromosome 9 (yellow) prior to azacitidine therapy. At “response” on day 167 (middle), there is near resolution of the copy-number alteration at chromosome 9. At day 1441, while still on therapy, at “pre-progression” (bottom) there is reemergence of the loss of copy number at chromosome 9 (yellow). (H) Serial MAF of a CBL, U2AF1, TET2, and an ASXL1 mutation of patient AZA011 throughout azacitidine and eltrombopag therapy. Response to therapy was achieved by an improvement in platelet count. The MAF of the CBL, U2AF1, and TET2 mutations reduced accordingly. At day 1441, all 3 of these MAFs increased alongside emergence of a new ASXL1 mutation. The patient subsequently progressed on day 1525 with thrombocytopenia and an increase in BM myeloblasts.

ctDNA as a disease monitoring strategy in MDS. (A) Mutations and cytogenetic abnormalities present among all patients recruited to the azacitidine + eltrombopag study. (B) MAF measured dPCR of a TP53 P177R and U2AF1 Q157P gene mutation in BM MNL, PB MNL, PB neutrophils, plasma ctDNA, and whole-blood DNA from a patient with high-grade MDS. The patient had no circulating blasts in the PB detected by morphology. BM morphology revealed multilineage dysplasia with an excess of myeloblasts (11% of nucleated cells). (C) Correlation between MAF measured by dPCR between BM and plasma ctDNA across 75 matched time points (r2 = 0.84; P < .0001). (D) Case AZA004. Serial comparison of the MAF of TET2 N1890I and TET2 D1376V mutation by dPCR between BM and plasma ctDNA. The patient had MDS with a classification of RAEB-2, which responded to azacitidine and eltrombopag therapy by a reduction in BM myeloblast percentage. At various time points (day 193, day 318, and day 599), poor-quality blood-dilute aspirate samples were obtained (denoted by *). At these times, plasma ctDNA MAF was higher than BM MAF of the TET2 N1890I and TET2 D1376V mutation. There was also severe neutropenia at these time points (neutrophils = 0.13, 0.15, and 0.16 × 109/L, respectively). (E) Case AZA009. Serial MAF of a NRAS G13D mutation by dPCR of BM and plasma ctDNA. The patient had RAEB-1 and stable disease after azacitidine and eltrombopag therapy represented by a persistent but stable excess of BM blasts. There was eventual progression at day 407 of therapy to acute myeloid leukemia. (F) Case AZA007. Serial MAF of a KRAS A59G and SRSF2 P95H mutation by TS of BM and plasma ctDNA, respectively. The patent had refractory cytopenia with unilineage dysplasia with severe thrombocytopenia, which responded initially to azacitidine and eltrombopag therapy. The patient eventually progressed with an increase in BM myeloblast percentage. Of note, the SRSF2 mutation, despite being reduced, still remained detectable in ctDNA at all time points sampled. At the time of disease progression, the MAF of the SRSF2 mutation in plasma had clearly increased, while the KRAS mutation remained undetectable. (G) Depth of coverage (DOC) log2 ratio plots from low-coverage whole-genome sequencing (LC-WGS) of plasma in patient AZA011. At “baseline” (top), the plot shows the presence of a loss of copy number at chromosome 9 (yellow) prior to azacitidine therapy. At “response” on day 167 (middle), there is near resolution of the copy-number alteration at chromosome 9. At day 1441, while still on therapy, at “pre-progression” (bottom) there is reemergence of the loss of copy number at chromosome 9 (yellow). (H) Serial MAF of a CBL, U2AF1, TET2, and an ASXL1 mutation of patient AZA011 throughout azacitidine and eltrombopag therapy. Response to therapy was achieved by an improvement in platelet count. The MAF of the CBL, U2AF1, and TET2 mutations reduced accordingly. At day 1441, all 3 of these MAFs increased alongside emergence of a new ASXL1 mutation. The patient subsequently progressed on day 1525 with thrombocytopenia and an increase in BM myeloblasts.

Further methods are detailed in supplemental Methods.

Results and discussion

ctDNA accurately reflects the fractional abundance of somatic mutations detected in BM

The majority of cell-free DNA is derived from hematopoietic cells.19 As MDS is a clonal disorder characterized by ineffective hematopoiesis, we postulated that the malignant MDS genome would be well represented in circulating cell-free DNA. We first sought to understand how mutation detection in ctDNA compared with other hematopoietic compartments in a patient with MDS without significant cytopenia (Figure 1B). Here, the MAF of a TP53 and U2AF1 mutation from plasma ctDNA was comparable to DNA from PB neutrophils, whole blood, and BM aspirate mononuclear (MNL) cells. The lower MAF in the PB MNL cells most likely reflects the fact that many circulating lymphocytes may not be derived from the malignant MDS clones. These data are representative of our findings with several pathogenic mutations in patients with MDS (data not shown).

PB cytopenias are common in MDS; as such, molecular assessment of neutrophils and other PB cells is not always feasible. Therefore, the current “gold standard” for molecular testing in MDS is from BM aspirate DNA. Indeed, much of our understanding of the MDS genomic landscape has been through sequencing this compartment.6 In all cases (n = 10), the main driver mutations were detected in both BM and ctDNA (Table 1). Importantly, there was an excellent correlation (r2 = 0.84; P < .0001) between the MAF of these mutations in BM and ctDNA across multiple matched time points (n = 75) (Figure 1C). This is the highest correlation reported between a tumor compartment and ctDNA. Importantly, this correlation was preserved even when the patients were leukopenic (supplemental Figure 1C-D), and there was no correlation between ctDNA MAF and PB white cell count (supplemental Figure 1E). Together, these data confirm the fact that ctDNA accurately reflects the genomic architecture of BM blasts in MDS regardless of the PB white cell count. Not infrequently, BM biopsies provide poor-quality specimens due to technical difficulties such as BM fibrosis or hypoplasia. In situations where a suboptimal, blood-dilute BM aspirate was obtained, ctDNA analysis provided molecular information that was equal, and in some cases superior, to BM sampling (Figure 1D; supplemental Figure 2).

ctDNA dynamics reflect tumor burden during therapy for MDS

Overall assessment of therapeutic response in MDS is measured using standard criteria.20 However, these criteria fail to appreciate the tumor heterogeneity in MDS and do not capture the clonal dynamics and evolutionary changes observed with therapeutic pressure. Therefore, to better understand this, serial TS and/or dPCR analysis was performed on BM and ctDNA in the 10 patients with detected mutations (Figure 1; supplemental Figure 2). In each case, ctDNA dynamics closely followed that of BM DNA.

Studies have shown that TET2 mutations predict response to azacitidine,21,22 although benefit appears confined to patients with a MAF >10%. Furthermore, not all clones that harbor TET2 mutations show sensitivity to azacitidine.21 In case AZA004, there were 2 TET2 mutations present at baseline with a MAF >10%. Consistent with the findings of Bejar et al,21 a response to therapy was achieved, which was paralleled by a reduction in the MAF of both TET2 mutations in plasma ctDNA (Figure 1D). Importantly, we also found cases with distinct TET2 mutations where the TET2 mutant clones were not suppressed by azacitidine therapy (supplemental Figure 2E).

Despite initial response to azacitidine-based therapies, progression invariably occurs. In case AZA009, despite initial clinical stability during treatment, ctDNA demonstrated an expanding malignant subclone containing the NRAS mutation, which ultimately resulted in the patient’s progression to acute myeloid leukemia (Figure 1E). Importantly, in several patients who progressed after an initial response to therapy, ctDNA reflected dynamic changes in tumor burden (Figure 1F,H; supplemental Figure 2B-F).

Together, these findings highlight the ability of ctDNA analysis to mirror the genomic changes observed in the BM and track multiple driver mutations throughout therapy. Importantly, ctDNA shows the differential response of the malignant subclones during therapy and can be used to identify and preempt disease progression.

Serial ctDNA analysis can monitor karyotypic abnormalities in plasma

Although used in MDS prognostic models,2 the difficulty in using karyotypic abnormalities as a monitoring tool is that they are present in <50% of cases.17,23 This may be further compounded by lack of sensitivity of metaphase cytogenetics. To address this, we used LC-WGS to monitor chromosomal aberrations in plasma from 3 MDS patients throughout therapy (Figure 1; supplemental Figure 3).

Case AZA011 highlights a patient who had a del9q alteration detected in the BM by conventional cytogenetics (28/30 metaphase cells) (Table 1). Prior to treatment, this del9q was clearly identifiable in plasma ctDNA (Figure 1G). Notably, following clinical response to therapy, the copy-number alteration was markedly reduced in plasma, suggesting that azacitidine was able to suppress the malignant clone and allow hematopoiesis to be restored from other hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells.24 The patient achieved a prolonged response (>4 years) but eventually progressed in the BM with an increasing myeloblast count (day 1492). Interestingly, progression was associated with a re-emergence of the del9q clone, which ctDNA detected almost 3 months before confirmation by BM cytogenetic analysis (Figure 1G). Importantly, while no cytogenetic evolution was noted at progression, TS clearly showed clonal evolution with the emergence of a new ASXL1 mutation in ctDNA at this time (Figure 1H). ASXL1 mutations confer a poor outcome in the myeloid malignancies, potentially negating the positive influence of TET2 mutations in mediating response to azacitidine therapy.21,22 It is currently unclear if azacitidine primarily acts by suppressing or differentiating the dominant malignant clone.11,25,26 Although the data in this case would suggest the former, it remains entirely possible that in other cases, azacitidine results in a restoration of blood counts by differentiating the malignant clone.

There is growing evidence supporting the importance of molecular assessment in MDS. Here, we show that ctDNA mirrors the genomic information from BM, accurately reflects the dynamic clonal changes seen in response to therapy, and can predict treatment failure. Together, these data support the use of ctDNA analysis as a noninvasive biomarker to compliment existing monitoring strategies for MDS.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Gisela Mir Arnau, Timothy Semple, Sreeja Gadipally, and Timothy Holloway for assistance with LC-WGS; Michelle McBean for assistance with sample retrieval; and Meaghan Wall for providing cytogenetic information on patients.

This work was funded by a Senior Leukaemia Foundation Australia Fellowship and VESKI Innovation Fellowship (M.A.D.), a National Breast Cancer Foundation and Victorian Cancer Agency Fellowship (S.-J.D.). National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia grants 1128984, 1106444, and 1106447 (M.A.D.) and 1107126 and 1104549 (S.-J.D.) partly funded this research. This work was also supported by the Klempfner Epigenetics Fellowship administered by the Snowdome Foundation and the Haematology Society of Australia and New Zealand young investigator grant (P.Y.). The clinical study patient recruitment was funded by the Victorian Cancer Agency, Celgene, and GlaxoSmithKline.

Authorship

Contribution: P.Y., S.-J.D., and M.A.D. designed the project, interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript; M.D. recruited study participants; M.D., P.Y., D.W., and P.B. provided patient samples and clinicopathological data; S.-J.D., M.A.D., P.Y., and R.A. developed the targeted gene panel with helpful input from P.B. and D.W.; P.Y., S.F., D.S., R.V., S.Q.W., and C.Y.F. performed the experimental work; P.Y. and T.H. analyzed data with input from K.D.; and all authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Sarah-Jane Dawson, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, 305 Grattan St, Melbourne, VIC 3000, Australia; e-mail: sarah-jane.dawson@petermac.org; and Mark A. Dawson, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, 305 Grattan St, Melbourne, VIC 3000, Australia; e-mail: mark.dawson@petermac.org.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal