Key Points

The GCB subtype of DLBCL relies exclusively on tonic BCR signaling via CD79A Y188.

PTEN protein expression and BCR surface density determine the contribution of tonic BCR signaling to AKT activity in GCB-DLBCL.

Abstract

We used clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats/Cas9-mediated genomic modification to investigate B-cell receptor (BCR) signaling in cell lines of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). Three manipulations that altered BCR genes without affecting surface BCR levels showed that BCR signaling differs between the germinal center B-cell (GCB) subtype, which is insensitive to Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibition by ibrutinib, and the activated B-cell (ABC) subtype. Replacing antigen-binding BCR regions had no effect on BCR signaling in GCB-DLBCL lines, reflecting this subtype’s exclusive use of tonic BCR signaling. Conversely, Y188F mutation in the immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif of CD79A inhibited tonic BCR signaling in GCB-DLBCL lines but did not affect their calcium flux after BCR cross-linking or the proliferation of otherwise-unmodified ABC-DLBCL lines. CD79A-GFP fusion showed BCR clustering or diffuse distribution, respectively, in lines of ABC and GCB subtypes. Tonic BCR signaling acts principally to activate AKT, and forced activation of AKT rescued GCB-DLBCL lines from knockout (KO) of the BCR or 2 mediators of tonic BCR signaling, SYK and CD19. The magnitude and importance of tonic BCR signaling to proliferation and size of GCB-DLBCL lines, shown by the effect of BCR KO, was highly variable; in contrast, pan-AKT KO was uniformly toxic. This discrepancy was explained by finding that BCR KO–induced changes in AKT activity (measured by gene expression, CXCR4 level, and a fluorescent reporter) correlated with changes in proliferation and with baseline BCR surface density. PTEN protein expression and BCR surface density may influence clinical response to therapeutic inhibition of tonic BCR signaling in DLBCL.

Introduction

Signals generated by the B-cell receptor (BCR), transmitted through cytoplasmic tails of its CD79A and CD79B subunits, govern development, persistence, and function of normal B cells. Binding of cognate antigen by hypervariable regions (HVRs) of BCR immunoglobulin chains initiates one type of BCR signaling, which proceeds through well-characterized mediators and molecular events,1 including phosphorylation by Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK). The BTK inhibitor ibrutinib is clinically effective against several types of B-cell neoplasms, adding to evidence that they use antigen-driven BCR signaling. One of those is diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), whose “activated B-cell” (ABC) subtype was named for its similarity in gene expression to normal B cells activated by BCR cross-linking.2 Cell lines representing ABC-DLBCL depend on BCR signaling with antigen-driven features, and most are sensitive to ibrutinib,3 which was clinically effective in ∼40% of ABC-DLBCL patients.4

Most cell lines of the “germinal center B-cell” (GCB) DLBCL subtype possess a BCR that can be stimulated by cross-linking to mimic antigen-driven signaling; however, most GCB-DLBCL lines and primary tumors are resistant to ibrutinib3,4 and lack NF-κB pathway activity, a consequence of antigen-driven BCR signaling highly characteristic of ABC-DLBCL.5 Because GCB-DLBCL lines depend on SYK6 and its AKT-driven downstream effects,7,8 it has been suggested that GCB-DLBCL utilizes the “tonic,” antigen-independent type of BCR signaling, which is transmitted via SYK and serves principally to activate the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT/MTOR pathway.9 However, single-agent clinical trials of the SYK inhibitor fostamatinib in relapsed/refractory DLBCL patients have shown low response rates, even in the GCB subtype.10,11

We present results from genomic modification studies of DLBCL lines that prove that GCB-DLBCL lines exclusively use tonic BCR signaling and show that its magnitude and importance are proportional to BCR surface density and contingent on PTEN protein expression. We also show that tonic BCR signaling (but not antigen-driven BCR signaling) requires specific phosphorylation of CD79A. These findings have implications for targeted therapy of DLBCL.

Methods

Complete descriptions are provided in the supplemental Methods (available on the Blood Web site).

Genomic modification

Transfection was performed by Neon electroporation (Thermo Fisher). Gene targeting used chimeric plasmids (Addgene) pX330-U6-Chimeric_BB-CBh-hSpCas9 and pX335-U6-Chimeric_BB-CBh-hSpCas9n(D10A) for respective expression of wild-type or D10A “nickase” Cas9. Guide RNA (gRNA) sequences were designed with the online CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats) Design Tool (http://crispr.mit.edu/). For knock-in, 1 or more Cas9/gRNA plasmids was coelectroporated with a homologous recombination donor plasmid containing silent mutations to prevent targeting of the donor plasmid or modified genomic locus. Homology arms and sequences for insertion by homologous recombination were ordered as gBlocks Gene Fragments (Integrated DNA Technologies) and captured via the StrataClone Ultra Blunt PCR Cloning Kit (Agilent) for complete assembly in a plasmid.

Superresolution microscopy

Superresolution images were obtained using a DeltaVision OMX Blaze V4 Microscope (GE Healthcare) with UPLSAPO 100× objective (Olympus), N = 1.514 immersion oil, and a 488-nm laser with 528/48 filter for GFP detection and a 642-nm laser with 683/40 filter for CellMask Deep Red Plasma Membrane Stain detection. Z stack images were taken at the plane of contact between cells and cover glass ± 1.5 µm using sequential structured illumination mode with dual electron multiplied charge-coupled device (EMCCD) cameras at 5 MHz and 170 gain, 512 × 512 image resolution, and 0.125-µm section spacing. Raw images were processed in softWoRx software (GE Healthcare) using the OMX structured illumination reconstruction algorithm. Videos with three-dimensional projections were generated with softWoRx.

Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET)

The FRET-based AKT activity reporter AktAR2 (Addgene)12 was modified by N-terminal addition of the 10 N-terminal amino acids (AA) from Lyn kinase.13 Adjuncts to FRET determination included constructs expressing the following: Cerulean3 alone; cpVenus[E172] alone; C3-cpV (Cerulean3-cpVenus[E172]), fused without a linker, as a maximum FRET control; C3-spacer-cpV, in which the FoxO1 phosphorylation site was replaced with a 230-AA TRAF2-derived spacer, as a low-FRET control14 ; and a “Dead” Lyn-AktAR2, in which the FoxO1 Thr-24 was changed to a similar but unphosphorylatable residue (Val), serving as a baseline FRET control. Cells were stably transfected to express the FRET constructs using Sleeping Beauty transposon plasmids (Addgene).15

Measurement of FRET efficiency (E) on the OMX Blaze V4 microscope used “3-filter cube” methodology16 with a 60× TIRF oil objective (Olympus) in wide-field mixed-FRET mode with EMCCD cameras operated without EMCCD gain. A 445-nm laser with 478/35 filter was used for donor fluorescence with donor excitation (IDD, donor channel); 445-nm laser with 541/22 filter, for acceptor emission with donor excitation (IDA, FRET channel); and 514-nm laser with 541/22 filter, for acceptor emission with acceptor excitation (IAA, acceptor channel). Mean fluorescent intensities for each cell and channel were calculated with softWoRx. cpVenus[E172] and Cerulean3 single-color constructs were used for a and d channel cross-talk coefficients, respectively. The C3-cpV construct was used to calculate the G factor by acceptor photobleaching.16

LSR Fortessa flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) settings for E determination were as follows: 405-nm laser with 450/50 filter for IDD, 405-nm laser with 525/50 filter for IDA, and 488-nm laser with 530/30 filter for IAA. Cells expressing cpVenus[E172] alone were used for a and b coefficients, and cells expressing Cerulean3 alone were used for c and d coefficients; only cells in the higher half of fluorescence intensity were used, and coefficients were calculated by linear regression. Similarly, cells with higher expression of the C3-cpV and C3-spacer-cpV constructs, containing identical fluorophores but differing highly in FRET efficiency, were used to determine average values of sensitized acceptor emissions (Fc) and corrected IDD and IAA intensities for calculation of the G factor.17 All constants were separately measured for each experiment.

Results

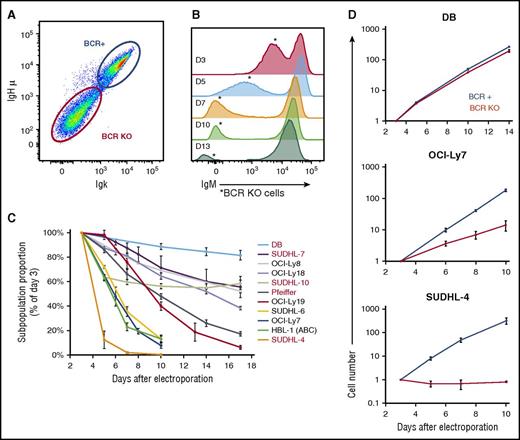

BCR knockout (KO) variably reduces proliferation in GCB-DLBCL lines

To investigate the BCR’s role in GCB-DLBCL, we used CRISPR methods to knock out immunoglobulin genes in GCB-DLBCL lines. Electroporation delivering plasmids expressing Cas9 protein and a gRNA produced a subpopulation of cells with reduced surface BCR levels (Figure 1A) that declined to undetectable within 7 days in all lines (Figure 1B; supplemental Figure 1). Effects were similar between targeting immunoglobulin heavy (IgH) or light (IgL) chain genes, and between targeting an immunoglobulin chain’s cell line–specific HVR or one of its constant exons (data not shown). The proportion of BCR-KO cells in electroporated cultures also declined over time (Figure 1B), but the rate of decline varied greatly between GCB-DLBCL lines (Figure 1C), for both IgH isotypes. Absolute growth curves showed that the relative decline of BCR-KO cells was largely because of slower proliferation (Figure 1D), confirmed by lower proportions of BCR-KO cells in S and G2+M phases (supplemental Figure 2A-B). Some BCR-KO cells in the most sensitive lines also had sub-G1 DNA content, and apoptosis induction was confirmed by increased caspase-3 activity (supplemental Figure 2C).

CRISPR/Cas9 targeting of immunoglobulin genes eliminates BCR surface expression and reduces proliferation of GCB-DLBCL lines. (A) Surface levels of IgM and Igκ of OCI-Ly19 cells, measured by flow cytometry (FCM) 5 days after electroporation with a Cas9/gRNA plasmid targeting their IgH HVR. (B) Histogram of IgM surface levels in OCI-Ly19 cells over time (D = days after electroporation), indicating the proportion and BCR surface level of BCR-KO cells (*). (C) Proportion over time of BCR-KO cells (made by IgH targeting) in DLBCL lines, normalized to the initial value determined 3 days after electroporation. Cell lines with names in black express IgM; those in red, an IgG isotype. (D) Absolute growth curves for BCR-replete and BCR-KO cells of representative GCB-DLBCL lines, relative to the starting point 3 days after electroporation. Panels C and D display the mean of results from 3 biological replicates, each using a different IgH-targeting gRNA, with error bars showing ± standard deviation (SD).

CRISPR/Cas9 targeting of immunoglobulin genes eliminates BCR surface expression and reduces proliferation of GCB-DLBCL lines. (A) Surface levels of IgM and Igκ of OCI-Ly19 cells, measured by flow cytometry (FCM) 5 days after electroporation with a Cas9/gRNA plasmid targeting their IgH HVR. (B) Histogram of IgM surface levels in OCI-Ly19 cells over time (D = days after electroporation), indicating the proportion and BCR surface level of BCR-KO cells (*). (C) Proportion over time of BCR-KO cells (made by IgH targeting) in DLBCL lines, normalized to the initial value determined 3 days after electroporation. Cell lines with names in black express IgM; those in red, an IgG isotype. (D) Absolute growth curves for BCR-replete and BCR-KO cells of representative GCB-DLBCL lines, relative to the starting point 3 days after electroporation. Panels C and D display the mean of results from 3 biological replicates, each using a different IgH-targeting gRNA, with error bars showing ± standard deviation (SD).

As a control, we also targeted CXCR4, another surface receptor in GCB-DLBCL lines that signals in response to specific ligand. CXCR4 KO did not affect the growth of GCB-DLBCL lines, although it did abrogate their chemotaxis to CXCL12 (supplemental Figure 3), showing that the effects of BCR KO were not simply because of loss of a surface receptor and suggesting that the BCR in GCB-DLBCL lines may be signaling in the absence of cognate antigen.

BCR KO reduces AKT activity in GCB-DLBCL lines

We hypothesized that changes in proliferation caused by BCR KO in different GCB-DLBCL lines would be proportional to changes in other factors regulated by BCR signaling. To quantify the BCR KO–induced change in proliferation, independent of differences between GCB-DLBCL lines in baseline growth rates, we calculated “relative proliferation” as the ratio of slopes of absolute growth curves (BCR-KO/BCR replete; supplemental Table 1). Proportionality of effects was confirmed by strong correlation between relative proliferation and BCR KO–induced reduction in cell size, assessed by forward-angle light scatter in FCM or bright-field area in image cytometry (supplemental Figure 4).

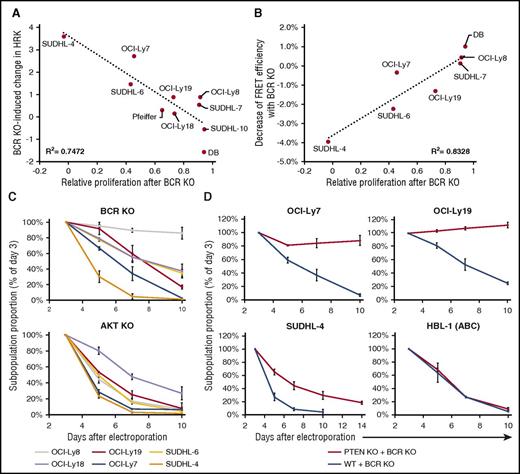

We then sought BCR KO–induced differences in gene expression that correlated with relative proliferation. HRK, previously implicated in apoptosis caused by SYK inhibition and FOXO1 activation in GCB-DLBCL lines,7,8 was upregulated most in lines with the greatest reduction in proliferation by BCR KO (Figure 2A). To discover pathways regulated by BCR signaling in GCB-DLBCL lines, we ranked genes by a metric of correlation between BCR KO–induced changes in expression and relative proliferation. Gene set enrichment analysis of this rank (supplemental Figure 5A-G) found high enrichment for 3 largely nonoverlapping sets of genes upregulated in neoplastic B-cell lines by manipulations inhibiting AKT or 2 of its known consequences: forced expression of PTEN (a negative regulator of AKT activation) in HT, a GCB-DLBCL line lacking PTEN protein18 ; expression of a FOXO1 mutant, able to resist negative regulation by AKT, in the pre-BCR-expressing cell line RCH-ACV19 ; and treatment of Burkitt lymphoma cell lines, in which AKT is believed to be activated by tonic BCR signaling, with rapamycin, an inhibitor of AKT-activated MTOR.20 Genes downregulated by rapamycin in Burkitt lymphoma cell lines were also highly enriched, in the opposite direction, in the rank (supplemental Figure 5H-I). These results indicated strong correlation in GCB-DLBCL lines between BCR KO–induced decreases in proliferation and AKT activity.

Effect of BCR KO on proliferation of GCB-DLBCL lines correlates with reduction in AKT activity. (A) Correlation between relative proliferation after BCR KO in GCB-DLBCL lines, as calculated by the ratio (BCR-KO/BCR replete) of their absolute growth curve slopes, and the BCR KO–induced log2 change in HRK expression. For each cell line, the average value of 2 to 4 biological replicates (each with a different IgH-targeting gRNA) is displayed. (B) Correlation for GCB-DLBCL lines between BCR KO–induced reductions in proliferation and AKT activity, measured by FRET efficiency with the Lyn-AktAR2 reporter. AKT activity reduction value is the average of 3 biological replicates, each with a different IgH-targeting gRNA. (C) Relative decline of KO cells in GCB-DLBCL lines after IgH-targeting KO of BCR (upper panel) or combined KO of all 3 AKT genes (lower panel). Values shown are the mean ± SD from 2 (BCR KO) or 3 (AKT KO) biological replicates. (D) Relative decline of BCR-KO cells in DLBCL lines that are either unmodified or have previously undergone PTEN KO. Values shown are the mean ± SD from 3 biological replicates.

Effect of BCR KO on proliferation of GCB-DLBCL lines correlates with reduction in AKT activity. (A) Correlation between relative proliferation after BCR KO in GCB-DLBCL lines, as calculated by the ratio (BCR-KO/BCR replete) of their absolute growth curve slopes, and the BCR KO–induced log2 change in HRK expression. For each cell line, the average value of 2 to 4 biological replicates (each with a different IgH-targeting gRNA) is displayed. (B) Correlation for GCB-DLBCL lines between BCR KO–induced reductions in proliferation and AKT activity, measured by FRET efficiency with the Lyn-AktAR2 reporter. AKT activity reduction value is the average of 3 biological replicates, each with a different IgH-targeting gRNA. (C) Relative decline of KO cells in GCB-DLBCL lines after IgH-targeting KO of BCR (upper panel) or combined KO of all 3 AKT genes (lower panel). Values shown are the mean ± SD from 2 (BCR KO) or 3 (AKT KO) biological replicates. (D) Relative decline of BCR-KO cells in DLBCL lines that are either unmodified or have previously undergone PTEN KO. Values shown are the mean ± SD from 3 biological replicates.

To support the implication that BCR signaling promotes AKT activity in GCB-DLBCL lines, we used a reporter construct to measure the effect of BCR KO on AKT activity directly. AktAR2 contains variants of cyan fluorescent protein (CFP: Cerulean3) and yellow fluorescent protein (YFP: cpVenus[E172]) separated by a linker containing an AKT phosphorylation target sequence of FOXO1 (supplemental Figure 6A); reporter phosphorylation increases its FRET.12 We used FCM to measure FRET efficiency (E) in thousands of cells expressing membrane-targeted AktAR2 (Lyn-AktAR2),13 to determine precisely the difference in AKT activity between unmodified and BCR-KO cells (supplemental Figure 6B-E). Across a spectrum of GCB-DLBCL lines, spanning the range of dependence on BCR signaling for proliferation, BCR KO–induced reductions in AKT activity correlated well with proliferation reduction by BCR KO (Figure 2B). Fluorescence microscopy confirmed the reduction in E of Lyn-AktAR2 by BCR KO (supplemental Figure 6F-G). BCR KO–induced reductions in AKT activity determined by FCM and Lyn-AktAR2 also correlated generally with the lines’ sensitivity to a clinically tested small-molecule SYK inhibitor (P505-15, PRT062607) or a U.S. Food and Drug Administration–approved inhibitor (idelalisib) of the PI3K p110δ isoform (supplemental Figure 7A-B). These inhibitors also reduced AKT activity in GCB-DLBCL lines in a dose-responsive manner (supplemental Figure 7C-E).

Phosphorylation of AKT Ser473 or pThr308 are commonly used as surrogate measures of AKT activity. By western blotting, BCR KO reduced pSer473 across a spectrum of GCB-DLBCL lines, but the degree of reduction correlated poorly with the lines’ sensitivity to BCR KO (supplemental Figure 8A); this was confirmed by electrochemiluminescence assays for AKT pSer473 or pThr308 in lysates from unmodified and BCR-KO cells (supplemental Figure 8B-C). However, upregulation of CXCR4 surface levels by BCR KO correlated well with relative proliferation in GCB-DLBCL lines (supplemental Figure 9A-B). Because CXCR4 expression is promoted by FOXO1,21 it provides an inverse measure of AKT activity, and its upregulation supports AKT inhibition as a consequence of BCR KO that determines its effect on proliferation. Overall, these findings indicate that BCR signaling makes a variable but important contribution to AKT activity in GCB-DLBCL lines.

AKT activity reduction determines the effect of BCR KO on GCB-DLBCL lines

To address whether the variable response to BCR KO was because of its proportional effect on AKT activity, vs a variable dependence of GCB-DLBCL lines on AKT activity, we performed simultaneous KO of all 3 AKT genes expressed in DLBCL lines.22 This produced a subpopulation of cells with reduced pan-AKT antibody staining and CXCR4 upregulation (supplemental Figure 10A), whose proportion declined rapidly over time in GCB-DLBCL lines, even those little affected by BCR KO (Figure 2C). Specificity of pan-AKT targeting was confirmed by rescuing AKT-KO cells by transient expression of constitutively active (myristoylated) murine AKT1 (MyrAKT; supplemental Figure 10B). These results indicated that GCB-DLBCL lines uniformly depend on AKT activity, to which BCR signaling makes a variable contribution.

To establish the importance of the contribution of BCR signaling to AKT activity in GCB-DLBCL lines, we used KO of PTEN, a negative regulator of AKT activation, to maintain AKT activity after BCR KO. Targeting PTEN (supplemental Figure 10C) yielded GFP+ cells lacking PTEN protein (supplemental Figure 10D), which were viably sorted to purity and expanded. PTEN KO protected GCB-DLBCL lines from proliferation reduction by subsequent BCR KO, completely or partially (Figure 2D), and reduced their sensitivity to P505-15 or idelalisib (supplemental Figure 10E). In contrast, PTEN KO did not protect the ABC-DLBCL line HBL-1 from BCR KO, consistent with PI3K/AKT not being the sole critical pathway activated by the BCR in ABC-DLBCL (Figure 2D). MyrAKT also rescued GCB-DLBCL lines from proliferation reduction by BCR KO (supplemental Figure 10F-G), further implicating AKT activation as the principal consequence of BCR signaling in GCB-DLBCL lines.

BCR signal transmission in GCB-DLBCL lines is consistent with tonic BCR signaling

Because forced AKT activation can rescue normal mouse B cells from conditional BCR deletion,9 we investigated other features of tonic BCR signaling in GCB-DLBCL lines. The response of normal mouse B cells to BCR KO is replicated by inactivation of SYK23,24 or CD19.25,26 Consistent with tonic BCR signaling, SYK phosphorylation at activating (Y352) and autophosphorylation (Y525/Y526) sites was reduced by BCR KO in GCB-DLBCL lines (supplemental Figures 8A and 11). The relative decline in GCB-DLBCL lines caused by KO of SYK or CD19 was generally similar to that produced by BCR KO (supplemental Figure 12A-B) and was rescued by PTEN KO (supplemental Figure 12C).

Transgenic CD79A mutations in mice, deleting its immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM) or mutating ITAM tyrosines, maintain surface BCR levels but affect B cells similarly to IgH interruption.27-29 To determine whether BCR signaling in GCB-DLBCL lines requires CD79A ITAM tyrosines for transmission, we used knock-in to insert Y>F mutations of both ITAM tyrosines, marked by fusion of GFP via a flexible linker30 (Figure 3A). Tyrosine-mutated and unmutated-control CD79A forms equivalently maintained surface BCR expression (Figure 3B) and BCR cross-linking–induced calcium flux (Figure 3C) in GCB-DLBCL lines. However, although the unmutated construct did not affect growth, CD79A mutation had a strong proliferation-reducing effect (Figure 3D). Additional experiments showed that the effect of CD79A ITAM mutations was largely attributable to Y188F alone (Figure 3E; supplemental Figure 13A-B). In contrast, CD79A ITAM mutations did not reduce proliferation in otherwise-unmodified ABC-DLBCL lines (supplemental Figure 13C-D). Similar results were also obtained using FLAG peptide as a marker of CD79A ITAM deletion (supplemental Figure 14).

Mutation of the CD79A ITAM selectively affects tonic BCR signaling in GCB-DLBCL lines. (A) Schematic of the knock-in approach to fuse GFP to the 3′ end of CD79A, along with either mutation of both ITAM tyrosines (YY>FF) or no other change in CD79A (wild type [WT]). The sequence of the CD79A cytoplasmic tail shows the ITAM and its tyrosine residues. (B) BCR surface level and GFP expression in OCI-Ly7 cells 3 days after electroporation to knock in CD79A-GFP constructs. Both constructs yield 3 populations of cells, as marked in the top panel for the YY>FF construct, and GFP and BCR levels are correlated in knock-in cells. The bottom panel shows histograms of surface BCR level for the 3 populations in the top panel, as well as for knock-in cells with the WT construct, indicating that knock-in cells with the different constructs have equivalent BCR surface levels. (C) Calcium flux in response to BCR cross-linking with anti-IgM in CD79A-GFP knock-in OCI-Ly19 cells. (D) Absolute growth curves for BCR KO and CD79A-GFP knock-in cells, relative to the starting point 3 days after electroporation. The YY>FF ITAM mutation has effects similar to BCR KO in GCB-DLBCL lines. (E) Absolute growth curves, from a separate experiment, showing effect of single or dual CD79A ITAM tyrosine mutations in GCB-DLBCL lines. Panels D and E show the mean ± SD from 3 biological replicates.

Mutation of the CD79A ITAM selectively affects tonic BCR signaling in GCB-DLBCL lines. (A) Schematic of the knock-in approach to fuse GFP to the 3′ end of CD79A, along with either mutation of both ITAM tyrosines (YY>FF) or no other change in CD79A (wild type [WT]). The sequence of the CD79A cytoplasmic tail shows the ITAM and its tyrosine residues. (B) BCR surface level and GFP expression in OCI-Ly7 cells 3 days after electroporation to knock in CD79A-GFP constructs. Both constructs yield 3 populations of cells, as marked in the top panel for the YY>FF construct, and GFP and BCR levels are correlated in knock-in cells. The bottom panel shows histograms of surface BCR level for the 3 populations in the top panel, as well as for knock-in cells with the WT construct, indicating that knock-in cells with the different constructs have equivalent BCR surface levels. (C) Calcium flux in response to BCR cross-linking with anti-IgM in CD79A-GFP knock-in OCI-Ly19 cells. (D) Absolute growth curves for BCR KO and CD79A-GFP knock-in cells, relative to the starting point 3 days after electroporation. The YY>FF ITAM mutation has effects similar to BCR KO in GCB-DLBCL lines. (E) Absolute growth curves, from a separate experiment, showing effect of single or dual CD79A ITAM tyrosine mutations in GCB-DLBCL lines. Panels D and E show the mean ± SD from 3 biological replicates.

BCR signaling in GCB-DLBCL lines is antigen independent

Because conditional BCR deletion affects all mouse B cells equally,31 tonic BCR signaling is presumed to be antigen-independent. We investigated the antigen dependence of BCR signaling in GCB-DLBCL lines by making their BCRs specific for tetanus toxoid (TTox), and therefore presumably not antigen–stimulated in standard cultures. To do this, we knocked in the complementary DNA of a fluorescent protein (GFP for IgH, the CFP variant mTurquoise2 for IgL) at the translation start site of the expressed immunoglobulin allele, followed by sequences encoding a 2A peptide, a signal peptide, and an HVR (supplemental Figure 15A). Replacing the IgH HVR (H-HVR) alone suggested a requirement for compatibility between IgH and IgL HVRs (supplemental Figure 15B-C), as reported for early B-cell development32 ; this was confirmed by “mixing studies” using various combinations of IgH and IgL HVRs from other GCB-DLBCL lines (supplemental Figure 16A-C).

Simultaneous replacement with paired IgH and IgL HVRs from the same B-cell source was therefore both feasible and necessary to achieve equivalent BCR levels for different HVR pairs, as shown by gating on GFP+/CFP+/BCR+ cells (supplemental Figure 15D-E) and to fairly evaluate HVR-specific effects on GCB-DLBCL lines. Dual replacement with HVR pairs from isolated TTox-reactive B cells33 produced BCRs that were expressed at levels similar to those of endogenous HVRs (supplemental Figure 17A), functional, and antigen-specific: anti-IgM cross-linking triggered calcium flux in dual HVR-replaced cells, for both endogenous and TTox-reactive HVRs, but TTox triggered calcium flux only in cells with TTox-reactive HVRs (Figure 4A). Similar effects were observed with OVA peptide and OVA-reactive HVRs (supplemental Figure 17B-C).

Dual HVR replacement selectively affects BCR signaling in ABC-DLBCL lines. (A) Calcium flux in response to BCR stimulation in OCI-Ly19 cells with endogenous or TTox-reactive HVRs. BCR cross-linking with anti-IgM triggers calcium flux for both HVR types, but only cells with TTox-reactive HVRs respond to TTox. (B) Absolute growth curves after HVR replacement or BCR KO in GCB-DLBCL lines, relative to the starting point 3 days (SUDHL-6 and OCI-Ly19) or 6 days (OCI-Ly7 and SUDHL-4) after electroporation. Effects of HVR replacement are similar for endogenous (WT) and TTox-reactive HVRs. (C) Absolute growth curves after HVR replacement or BCR KO in PTEN-deficient ABC-DLBCL line U2932. Growth reduction by HVR replacement with TTox-reactive HVRs (upper panel) or U2932 reverted HVRs in a separate experiment (lower panel) is similar to that of BCR KO. (D) Absolute growth curves after HVR replacement or BCR KO in PTEN-expressing ABC-DLBCL line HBL-1. Growth reduction by HVR replacement with TTox-reactive HVRs is less than that of BCR KO (upper panel) in otherwise unmodified HBL-1 cells, but similar to that of BCR KO in HBL-1 cells in which CD79A ITAM tyrosines have been mutated (lower panel). Panels B-D show the mean ± SD from 3 biological replicates.

Dual HVR replacement selectively affects BCR signaling in ABC-DLBCL lines. (A) Calcium flux in response to BCR stimulation in OCI-Ly19 cells with endogenous or TTox-reactive HVRs. BCR cross-linking with anti-IgM triggers calcium flux for both HVR types, but only cells with TTox-reactive HVRs respond to TTox. (B) Absolute growth curves after HVR replacement or BCR KO in GCB-DLBCL lines, relative to the starting point 3 days (SUDHL-6 and OCI-Ly19) or 6 days (OCI-Ly7 and SUDHL-4) after electroporation. Effects of HVR replacement are similar for endogenous (WT) and TTox-reactive HVRs. (C) Absolute growth curves after HVR replacement or BCR KO in PTEN-deficient ABC-DLBCL line U2932. Growth reduction by HVR replacement with TTox-reactive HVRs (upper panel) or U2932 reverted HVRs in a separate experiment (lower panel) is similar to that of BCR KO. (D) Absolute growth curves after HVR replacement or BCR KO in PTEN-expressing ABC-DLBCL line HBL-1. Growth reduction by HVR replacement with TTox-reactive HVRs is less than that of BCR KO (upper panel) in otherwise unmodified HBL-1 cells, but similar to that of BCR KO in HBL-1 cells in which CD79A ITAM tyrosines have been mutated (lower panel). Panels B-D show the mean ± SD from 3 biological replicates.

Absolute growth rates of dual HVR-replaced cells were the same for endogenous and TTox-reactive HVRs in all 4 GCB-DLBCL lines tested (Figure 4B), indicating that BCR signaling in GCB-DLBCL is HVR independent and, therefore, antigen independent. In contrast, dual replacement with TTox-reactive HVRs in the ABC-DLBCL line U2932 (which lacks PTEN protein) caused growth reduction similar to BCR KO (Figure 4C), despite producing surface BCR levels higher than did endogenous HVRs (supplemental Figure 17D). This is consistent with BCR knockdown and complementation experiments in ABC-DLBCL lines that showed a similar dependence on endogenous HVR sequences, indicating that their BCR signaling is driven by self-antigen.34 Similar proliferation reduction was caused by reverting somatic mutations of the predicted V, D, and J exons of the endogenous U2932 HVRs to their predicted postrecombination naive state (Figure 4C). In otherwise unmodified cells of the ABC-DLBCL line HBL-1 (which expresses PTEN protein), TTox-reactive HVR pairs either slowed growth less than did BCR KO or, if expressed more highly than BCRs with endogenous HVRs, supported proliferation equivalent to endogenous HVRs (Figure 4D; supplemental Figure 17E). However, in HBL-1 cells already modified by double- or single-Tyr mutation of the CD79A ITAM, which by itself was not growth retarding (supplemental Figure 13C-D), TTox-reactive HVRs resembled BCR KO in reducing proliferation (Figure 4D; supplemental Figure 13E). These findings confirm that ABC-DLBCL lines use antigen-dependent BCR signaling34 but also show that they may use compensatory tonic BCR signaling to maintain proliferation, depending on BCR level and PTEN status. Furthermore, they add to evidence that the contribution of tonic BCR signaling to AKT activation is only needed when PTEN is present: PTEN-deficient SUDHL-10 is the GCB-DLBCL line least affected by BCR KO, and restoration of BCR expression in the PTEN-deficient, BCR-negative GCB-DLBCL line HT had no effect on growth (supplemental Figure 18).

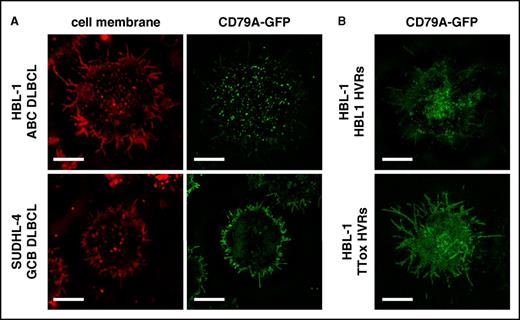

BCR distribution reflects BCR signaling type in DLBCL lines

Previous studies using lipid bilayers, Fab’ anti-BCR staining, and total internal reflectance fluorescence microscopy showed constitutive clustering of BCR units at the cell surface in lines and primary tumor cells of ABC-DLBCL, but not GCB-DLBCL.3 We used structured illumination superresolution microscopy to image BCR units, marked by GFP-fused unmutated CD79A, of live DLBCL lines on poly-l-lysine coated chamber slides. Also using a red lipid dye to define the cell membrane, we confirmed that BCR units were inhomogeneously distributed (clustered) at the cell surface of ABC-DLBCL lines, consistent with antigen binding, but diffusely distributed in the cell membrane of GCB-DLBCL lines, including villous projections (Figure 5A; supplemental Figure 19 and supplemental Videos 1 and 2). BCR units remained clustered after endogenous HVR replacement in the ABC-DLBCL line HBL-1 but were dispersed by TTox-reactive HVRs (Figure 5B), implying that constitutive BCR engagement by cognate self-antigen drives BCR clustering in ABC-DLBCL.

BCR clustering reflects type of BCR signaling in DLBCL lines. (A) Superresolution microscopy of BCR units, labeled by knock-in of CD79A-GFP fusion, in live cells imaged at the point of contact with glass coverslip chamber slides (bars represent 5 µm). Red CellMask dye marks the surface membrane. BCR units are clustered in the ABC-DLBCL line HBL-1, but diffusely distributed in the GCB-DLBCL line SUDHL-4. (B) SRM of BCR units in HBL-1 cells with CD79A-GFP fusion and dual HVR replacement. The BCR with endogenous HVRs remains clustered but is diffusely distributed when replaced with TTox-reactive HVRs.

BCR clustering reflects type of BCR signaling in DLBCL lines. (A) Superresolution microscopy of BCR units, labeled by knock-in of CD79A-GFP fusion, in live cells imaged at the point of contact with glass coverslip chamber slides (bars represent 5 µm). Red CellMask dye marks the surface membrane. BCR units are clustered in the ABC-DLBCL line HBL-1, but diffusely distributed in the GCB-DLBCL line SUDHL-4. (B) SRM of BCR units in HBL-1 cells with CD79A-GFP fusion and dual HVR replacement. The BCR with endogenous HVRs remains clustered but is diffusely distributed when replaced with TTox-reactive HVRs.

BCR surface density determines the magnitude of BCR signaling in GCB-DLBCL lines

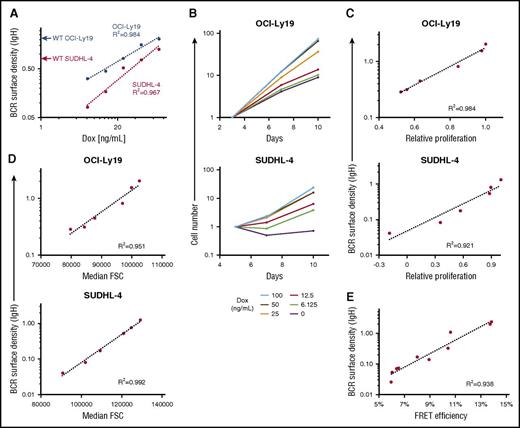

Because BCR signaling in GCB-DLBCL lines is HVR independent (Figure 4B), and its loss (via BCR KO) produces correlated reductions in proliferation and AKT activity (Figure 2B), we hypothesized that the magnitude of tonic BCR signaling in a GCB-DLBCL line would be proportional to the density of BCR units at the cell surface. We tested this by using a doxycycline-inducible expression vector to manipulate IgH levels in 2 GCB-DLBCL lines that had also undergone KO of their endogenous IgH. The surface density of BCR units was estimated by dividing the surface IgH staining intensity by the square of each cell’s forward scatter value, which is proportional to surface area (supplemental Figure 20). For each line, varying the IgH expression level produced a proportional change in BCR surface density (Figure 6A) and absolute growth rates (Figure 6B), and BCR surface density was strongly correlated with proliferation (Figure 6C), size (Figure 6D), and AKT activity (Figure 6E). This system for inducible IgH expression also enabled us to test the effect of IgH isotype in these lines, which naturally expressed either IgG4 (SUDHL-4) or IgM (OCI-Ly19). In each line, maximally induced IgG4 produced a higher BCR level than did IgM, as shown by staining for their common κ IgL isotype, although less than the apparent difference from staining for the respective IgH isotypes (supplemental Figure 21A). The growth rate was higher for IgG4 in both lines (supplemental Figure 21B-C), perhaps partly because of differences in surface BCR level, but there was not an obligate dependence on the naturally expressed isotype.

Effect of BCR surface density on tonic BCR signaling. (A) BCR surface density, measured by anti-IgH isotype antibody staining and FCM, increases with doxycycline (Dox) concentration in cells of OCI-Ly19 and SUDHL-4 GCB-DLBCL lines engineered with both KO of the endogenous IgH locus and expression of its same-isotype IgH by a Dox-inducible expression vector. Red and blue arrows on the y-axis mark the similarly determined BCR surface density of unmodified (WT) cells of the lines. For each line, BCR surface density is based on flow cytometric measurement of fluorescence intensity with an antibody specific for its IgH isotype; therefore, values are not directly comparable between isotypes or to BCR surface density determined with a different antibody (eg, to IgL) or by CD79A-GFP fluorescence. (B) Absolute growth curves for GCB-DLBCL lines with inducible IgH expression, relative to the starting point at the indicated Dox concentration (3 days for OCI-Ly19, 5 days for SUDHL-4), showing that growth rates increase with Dox concentration. (C) Correlation between BCR surface density and relative proliferation, defined here as the ratio of slopes of absolute growth curves at different Dox concentrations to that of the curve for maximal Dox concentration (100 ng/mL), for GCB-DLBCL lines at different levels of induced IgH expression. (D) Correlation between BCR surface density and cell size, estimated by the forward scatter value, for GCB-DLBCL lines at different levels of induced IgH expression. (E) Correlation between BCR surface density and AKT activity, measured by FRET efficiency of an AKT activity reporter, for OCI-Ly19 cells with different levels of induced IgH expression, achieved by different durations (up to 7 days) of Dox withdrawal. Data from 2 independent experiments are displayed.

Effect of BCR surface density on tonic BCR signaling. (A) BCR surface density, measured by anti-IgH isotype antibody staining and FCM, increases with doxycycline (Dox) concentration in cells of OCI-Ly19 and SUDHL-4 GCB-DLBCL lines engineered with both KO of the endogenous IgH locus and expression of its same-isotype IgH by a Dox-inducible expression vector. Red and blue arrows on the y-axis mark the similarly determined BCR surface density of unmodified (WT) cells of the lines. For each line, BCR surface density is based on flow cytometric measurement of fluorescence intensity with an antibody specific for its IgH isotype; therefore, values are not directly comparable between isotypes or to BCR surface density determined with a different antibody (eg, to IgL) or by CD79A-GFP fluorescence. (B) Absolute growth curves for GCB-DLBCL lines with inducible IgH expression, relative to the starting point at the indicated Dox concentration (3 days for OCI-Ly19, 5 days for SUDHL-4), showing that growth rates increase with Dox concentration. (C) Correlation between BCR surface density and relative proliferation, defined here as the ratio of slopes of absolute growth curves at different Dox concentrations to that of the curve for maximal Dox concentration (100 ng/mL), for GCB-DLBCL lines at different levels of induced IgH expression. (D) Correlation between BCR surface density and cell size, estimated by the forward scatter value, for GCB-DLBCL lines at different levels of induced IgH expression. (E) Correlation between BCR surface density and AKT activity, measured by FRET efficiency of an AKT activity reporter, for OCI-Ly19 cells with different levels of induced IgH expression, achieved by different durations (up to 7 days) of Dox withdrawal. Data from 2 independent experiments are displayed.

To determine whether correlation between BCR surface density (at its unmanipulated level) and the magnitude of tonic BCR signaling (as determined from effects of BCR KO) was consistent across GCB-DLBCL lines, we examined cells in which GFP had been fused by knock-in (without mutation) to CD79A, the rate-limiting component of the BCR complex,35 as an isotype- and antibody staining–independent measure of each cell’s surface BCR level. The reliability of this measure was indicated by CD79A-GFP’s localization at the cell membrane (supplemental Videos 1 and 2), colocalization with surface BCR (supplemental Figure 22), clustering according to DLBCL subtype and HVR engagement (Figure 5), and correlation with surface BCR level (Figure 3B). It was also shown with the system for inducible IgH expression in lines that also had knock-in of WT CD79A-GFP; as IgH expression was varied, surface BCR levels and CD79A-GFP fluorescence varied in concert (supplemental Figure 23). Across the spectrum of GCB-DLBCL lines, the unmanipulated level of BCR surface density (calculated from CD79A-GFP fluorescence) correlated highly with BCR KO–induced growth retardation (Figure 7A) or reduction in AKT activity (Figure 7B). BCR surface density also correlated with proliferation reduction caused by P505-15 at a concentration at which its effects were similar to those of BCR KO (supplemental Figure 24).

Effect of BCR surface density on tonic BCR signaling across GCB-DLBCL lines. (A) Correlation between BCR surface density based on CD79A-GFP fusion and reduction in proliferation caused by BCR KO in GCB-DLBCL lines. For reduction in proliferation, averages of 3 biological replicates (each with a different IgH-targeting gRNA) are displayed. (B) Correlation between BCR surface density based on CD79A-GFP fusion and BCR KO–induced reduction in AKT activity, as measured by percentage decrease of AKT activity reporter FRET efficiency, E, determined by FCM. For decrease of E, averages of 3 biological replicates (each with a different IgH-targeting gRNA) are displayed.

Effect of BCR surface density on tonic BCR signaling across GCB-DLBCL lines. (A) Correlation between BCR surface density based on CD79A-GFP fusion and reduction in proliferation caused by BCR KO in GCB-DLBCL lines. For reduction in proliferation, averages of 3 biological replicates (each with a different IgH-targeting gRNA) are displayed. (B) Correlation between BCR surface density based on CD79A-GFP fusion and BCR KO–induced reduction in AKT activity, as measured by percentage decrease of AKT activity reporter FRET efficiency, E, determined by FCM. For decrease of E, averages of 3 biological replicates (each with a different IgH-targeting gRNA) are displayed.

These results imply that BCR surface density, if measured in primary GCB-DLBCL tumor cells via some practical technique, would have potential for development into a biomarker predictive of clinical response to inhibition of tonic BCR signaling. Antibody staining for surface CD79B was an obvious candidate technique, but we found that BCR surface density based on CD79B staining did not correlate uniformly with BCR surface density based on CD79A-GFP fluorescence, or with effects of BCR KO or sensitivity to P505-15, largely because of outliers like the IgG-expressing GCB-DLBCL line DB (supplemental Figure 25). We found that DB had a small amount of residual surface CD79B after IgH KO, and a large amount of residual surface IgH after CD79B KO, as compared with other GCB-DLBCL lines (supplemental Figure 26A-B, top panels). This implied a degree of independence between BCR components in their surface expression in DB, which was supported by per cell measurements (supplemental Figure 26C). We also found that CD79A-GFP accelerated the rate of turnover of surface IgH (supplemental Figure 26D), which we speculate may be related to the reduction of residual surface CD79B or IgH in DB cells with CD79A-GFP (supplemental Figure 26A-B, bottom panels). Together with some surface CD79B being IgH independent, this may cause CD79A-GFP to reflect fully assembled and functional BCR units more consistently than CD79B.

Discussion

The importance of BCR signaling to B-cell lymphomas has been shown by functional studies in cell lines and mouse models,36 and by clinical responses to small-molecule inhibitors of kinases mediating transduction of BCR-generated signals. However, these studies and clinical approaches have generally not addressed variation in the type (antigen driven and/or tonic) and magnitude (or importance) of BCR signaling used by individual B-cell tumors. In this study, we used precise genomic manipulations that modified the BCR without changing its surface expression in DLBCL lines: dual HVR replacement, CD79A ITAM tyrosine mutation, and CD79A-GFP fusion. These revealed the clear distinction between DLBCL subtypes in the type of BCR signaling used constitutively: antigen–driven by ABC-DLBCL; tonic by GCB-DLBCL. Several additional features confirmed that the BCR signaling used by GCB-DLBCL lines corresponds to tonic BCR signaling in normal B cells and contributes to their essential need for AKT activity. Tonic BCR signaling also characterizes Burkitt lymphoma, which lacks NF-κB activity but depends on CD79A and SYK20 ; mutations in ID3 and/or TCF3 are highly frequent, upregulating transcription of immunoglobulin genes and suppressing the BCR signaling-inhibitory phosphatase PTPN6.20

However, we also found large variation between GCB-DLBCL lines in their dependence on BCR signaling and provided mechanistic reasons for this: (1) the magnitude of BCR signaling is determined by BCR surface density, which varies highly; (2) AKT must not be solely dependent for activation on the BCR, whose surface expression is low or absent in some GCB-DLBCL lines; and (3) loss of the negative AKT regulator PTEN can compensate for loss (or low levels) of BCR signaling. The importance of tonic BCR signaling to AKT activation in GCB-DLBCL is therefore heavily influenced by BCR surface density and PTEN protein expression, as shown in the model of supplemental Figure 27. This model provides a potential explanation for why the SYK inhibitor fostamatinib showed low overall efficacy in DLBCL patients, even (and exclusively) in those with the GCB subtype.10,11 The uniform susceptibility of GCB-DLBCL lines to pan-AKT KO suggests that GCB-DLBCL tumors unlikely to respond to inhibitors of tonic BCR signaling may still be responsive to inhibitors of other AKT-activating pathways or to inhibition of AKT at downstream points.

Whether PTEN and BCR surface density can ultimately be biomarkers to predict the clinical response of GCB-DLBCL patients to inhibition of tonic BCR signaling remains to be determined, but those factors do vary significantly in primary GCB-DLBCL tumors, as in GCB-DLBCL cell lines: surface IgH level varies highly in primary GCB-DLBCL tumors,37 with ∼20% of cases lacking BCR surface expression,38 and PTEN protein expression is absent in ∼50% of cases.18 PTEN protein can be assessed by immunohistochemistry of tumor histologic sections,39 but a predictive assay based on BCR surface density, or another biomarker reflecting it, would require development and validation in clinical trials of tonic BCR signaling inhibitors. BCR surface density is a continuous variable, which would require the setting of thresholds, and staining intensity differs between immunoglobulin isotypes, suggesting that perhaps there would need to be isotype-specific assays.

The correlations that we found between BCR surface density and the effects of BCR KO on AKT activity (and proliferation) were based on measuring BCR surface density by CD79A-GFP fluorescence and AKT activity with the Lyn-AktAR2 reporter; both of these techniques are valid but only usable in engineered cell lines. Alternative techniques applicable to primary samples, surface CD79B staining or detection of AKT phosphorylation, unfortunately did not provide similar uniform correlations. Surface CD79B independent of IgH has been observed in normal mouse B cells40 and cell lines41,42 after BCR cross-linking or cognate antigen encounter, and IgG (but not IgM) can be present on the surface of cells lacking the CD79A/B heterodimer.43,44 These precedents raise the possibility that some fraction of surface CD79B in some GCB-DLBCL lines may not be part of a complete BCR unit, and that surface CD79B staining may overestimate the amount of surface BCR that is generating tonic signals. Although phosphorylation of AKT sites Ser473 or Thr308 is widely used as a surrogate for AKT activity, the reliability of pSer473 in particular has been questioned (eg, for discordance with pThr30845 or for being rendered unnecessary by phosphorylation of S477 and T47946 ). Regulation of AKT activity has been reported for several sites of tyrosine phosphorylation,47,48 including at Y315/Y326 by Src family tyrosine kinases (although not previously linked to BCR signaling),49 or by nonphosphorylating factors,50 and AKT phosphorylation may have negative regulatory effects by promoting AKT ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation.51

Factors determining BCR surface density in GCB-DLBCL lines are unknown, although variation after dual-HVR replacement (supplemental Figure 16D) suggests that BCR surface density is affected by both cellular context and HVR sequence. GCB-DLBCL was named for similarity to centroblasts of the germinal center, which functions to select B-cell clones with high BCR affinity to antigen, a process involving upregulation of BCR surface levels.52,53 The type of BCR signaling (tonic, antigen–induced, or both) enhanced by higher BCR levels in centroblasts is unknown, but the 2 types may be somewhat merged in GC B cells, whose response to BCR ligation, as compared with that of non-GC mouse B cells, is less activating of NF-κB.54

Our results from CD79A modification are consistent with those in mouse B cells bearing CD79A-modified complete BCR complexes,27-29 or artificial proteins containing CD79A and/or CD79B cytoplasmic tails (which can drive the development of follicular B cells in BCR-deficient mice),55,56 but differ in identifying Y188 as the ITAM tyrosine most involved in tonic BCR signaling. Our results suggest that inhibiting Y188 phosphorylation may be a specific therapeutic approach to target tonic BCR signaling in GCB-DLBCL. CD79A ITAM mutations also reduced proliferation of the ABC-DLBCL line HBL-1 when combined with HVR replacement; this suggests that inhibition of tonic BCR signaling may enhance the therapeutic effect of inhibiting antigen-driven BCR signaling in ABC-DLBCL, consistent with observations that ibrutinib synergizes with inhibitors of PI3K, AKT, or MTOR in ABC-DLBCL lines.57

Our finding that phosphorylation of the CD79A ITAM has little or no participation in antigen-induced BCR signaling by DLBCL cell lines, as shown by the lack of effect of CD79A modification on proliferation of otherwise-unmodified ABC-DLBCL lines (supplemental Figure 13C-D) or BCR ligation-induced calcium flux in GCB-DLBCL lines (Figure 3C; supplemental Figure 13A), is also consistent with those prior studies.27-29,55,56 However, our results differ strikingly from frequently cited studies using non-BCR chimeric molecules containing CD79A cytoplasmic tails alone, in which tyrosine phosphorylation of the chimeric molecules after cross-linking was predominantly (if not completely) restricted to the proximal ITAM tyrosine, corresponding to human CD79A Y188.58,59 This discordance might be because of the absence of a CD79B cytoplasmic tail in the chimeric molecules, but studies using a complete BCR reconstituted in a mouse myeloma cell line also found that both CD79A ITAM tyrosines were required for normal tyrosine phosphorylation of other proteins after BCR ligation.58 The ability of CRISPR/Cas9 methods to modify genomic alleles of BCR components, notably immunoglobulin HVRs and the ITAM domains of CD79A and CD79B (data not shown), will enable highly physiologic future studies to elucidate molecular events in BCR signaling.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

Gene expression microarrays were scanned at the Quantitative Genomics & Microarray Core Laboratory at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston.

This work was supported by MD Anderson Cancer Center incentive and startup funds, institutional research grants, and Moon Shot in B-Cell Lymphoma funds (R.E.D.); Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas Individual Investigator Research Award RP100695 (R.E.D.); a HOPE Foundation/Southwest Oncology Group Development Award (R.E.D. and J.R.W.); a Leukemia & Lymphoma Society Scholar Award in Clinical Research (J.A.B.); the MD Anderson Cancer Center UTHealth Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences (L.B. and J.H.); and the Cancer Prevention Research Training Program of the MD Anderson Cancer Center (A.F.Y.). Cell sorting and other analyses were done at the MD Anderson Cancer Center Flow Cytometry Core Facility, supported by a National Cancer Institute (NCI), National Institutes of Health Cancer Center Support Grant (CCSG) (NCI P30 CA16672). Short tandem repeat DNA fingerprinting was done by the Characterized Cell Line Core Facility, supported by the CCSG. Sanger sequencing was done by the MD Anderson Cancer Center Sequencing and Microarray Facility, supported by the CCSG. Superresolution and FRET microscopy studies were done at the Immunology Microscopy Core Facility, supported by NCI (grant S10 RR029552).

Authorship

Contribution: O.H. and R.E.D. designed experiments; O.H., J.X., S.K., Z.W., L.B., J.M.C., D.G., N.S., L.S., A.F.Y., J.H., and A.R.K. performed experiments; O.H., Z.W., W.M., and R.E.D. analyzed gene expression data; O.H., J.M.C.M., R.E.D., and T.Z. designed, performed, and interpreted fluorescence microscopy and FRET experiments; J.R.W. and J.A.B. provided input on clinical relevance; and O.H., T.Z., and R.E.D. wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: R. Eric Davis, Department of Lymphoma and Myeloma, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Box 903, SCR1.2015, 7455 Fannin St, Houston, TX 77054; e-mail: redavis1@mdanderson.org.

![Figure 3. Mutation of the CD79A ITAM selectively affects tonic BCR signaling in GCB-DLBCL lines. (A) Schematic of the knock-in approach to fuse GFP to the 3′ end of CD79A, along with either mutation of both ITAM tyrosines (YY>FF) or no other change in CD79A (wild type [WT]). The sequence of the CD79A cytoplasmic tail shows the ITAM and its tyrosine residues. (B) BCR surface level and GFP expression in OCI-Ly7 cells 3 days after electroporation to knock in CD79A-GFP constructs. Both constructs yield 3 populations of cells, as marked in the top panel for the YY>FF construct, and GFP and BCR levels are correlated in knock-in cells. The bottom panel shows histograms of surface BCR level for the 3 populations in the top panel, as well as for knock-in cells with the WT construct, indicating that knock-in cells with the different constructs have equivalent BCR surface levels. (C) Calcium flux in response to BCR cross-linking with anti-IgM in CD79A-GFP knock-in OCI-Ly19 cells. (D) Absolute growth curves for BCR KO and CD79A-GFP knock-in cells, relative to the starting point 3 days after electroporation. The YY>FF ITAM mutation has effects similar to BCR KO in GCB-DLBCL lines. (E) Absolute growth curves, from a separate experiment, showing effect of single or dual CD79A ITAM tyrosine mutations in GCB-DLBCL lines. Panels D and E show the mean ± SD from 3 biological replicates.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/130/8/10.1182_blood-2016-10-747303/4/m_blood747303f3.jpeg?Expires=1769106032&Signature=ViEhjk-7cRP-vdwlxKtFQTq4AujgR-ZalXpSyFCk0gy7-niBcyMLIQdQiE-FNl-KlMa-vzE5P3EItkjoMe2ePr~W3iXw8mkQhDncAojEf8uZkxfQh6GeFkZmFglzzcB65WyIwIqnflZsB5w7DYhinXRKfqaAZO8oL6coViqkDEREXniHvL2~i92ryw~Tn0QWktAn6LjWdOuqUR1JfX20tOe90T1l-ocPxSm~8puc6sag2oVXsORoMqSEQy7YEtvSXZ~K7NSfWWGtIH10X75zU0PQoJDg5GU9JTtKf6wHjzglp-YCopXzgbdY3YsOJv2byEMtcn8GwnX-7AXIkeobaw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal