In recent years, monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) able to reinvigorate antitumor T-cell immunity have heralded a paradigm shift in cancer treatment. The most high profile of these mAbs block the inhibitory checkpoint receptors PD-1 and CTLA-4 and have improved life expectancy for patients across a range of tumor types. However, it is becoming increasingly clear that failure of some patients to respond to checkpoint inhibition is attributable to inadequate T-cell priming. For full T-cell activation, 2 signals must be received, and ligands providing the second of these signals, termed costimulation, are often lacking in tumors. Members of the TNF receptor superfamily (TNFRSF) are key costimulators of T cells during infection, and there has been an increasing interest in harnessing these receptors to augment tumor immunity. We here review the immunobiology of 2 particularly promising TNFRSF target receptors, CD27 and OX40, and their respective ligands, CD70 and OX40L, focusing on their role within a tumor setting. We describe the influence of CD27 and OX40 on human T cells based on in vitro studies and on the phenotypes of several recently described individuals exhibiting natural deficiencies in CD27/CD70 and OX40. Finally, we review key literature describing progress in elucidating the efficacy and mode of action of OX40- and CD27-targeting mAbs in preclinical models and provide an overview of current clinical trials targeting these promising receptor/ligand pairings in cancer.

Introduction

The concept of a 2-signal model of T-cell activation was initially proposed by Laffery and colleagues based on earlier work on the regulation of B-cell activation by Bretscher and Cohn.1 Subsequently, Jenkins, Schwartz, and others demonstrated that full T-cell activation required not only T-cell receptor (TCR) occupancy by major histocompatibility complex–anchored peptide, but also short-range costimulatory signals provided by non-T accessory cells.2 The identity of the first costimulatory receptor, CD28, was revealed using anti-CD28 monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) which when added to T-cell cultures provided the second signal necessary for T-cell proliferation and interleukin-2 (IL-2) secretion.3 Identification of additional costimulatory receptors came about in the 1980s with the discovery of T-cell determinants recognized by newly isolated mAbs. A number of these mAbs were found to enhance T-cell proliferation, but only when combined with reagents that induced TCR triggering, thus fulfilling the true definition of a costimulatory signal. With the advent of expression cloning in the late 1980s and early 1990s many costimulatory receptors and their natural ligands were molecularly cloned,4,5 thus paving the way to detailed analysis of their roles in immunity. Based on structural features, costimulatory receptors can be grouped primarily into those that belong to either the immunoglobulin superfamily (eg, CD28, ICOS, and CD226) or the tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily (TNFRSF), including CD27, OX40, 4-1BB, glucocorticoid-induced TNF receptor-related protein, death receptor 3, and CD30.3,6,-8 In addition, T cells express inhibitory receptors (eg, CTLA-4, PD-1, TIGIT, and B and T lymphocyte–associated, all of which are also members of the immunoglobulin superfamily) that negatively regulate T-cell responses through cell-intrinsic as well as cell-extrinsic mechanisms with CTLA-4 and PD-1 partly mediating their effects by countering the costimulatory activity of CD28.9,,,-13 The discovery that costimulatory signals can boost the magnitude of the T-cell response and the generation of effector and memory T cells, led to the notion that targeting these pathways may promote cellular immune responses against tumors or those elicited by vaccination. Conversely, blockade of costimulatory signaling has the potential to ameliorate overt T-cell responses in autoimmune and graft-versus-host disease as well as prevent rejection after allogeneic transplantation. Currently, 2 drugs (abatacept and belatacept) based on a CTLA-4-Ig fusion protein, a CD28 antagonist, are in clinical use. Although not broadly efficacious, CTLA-4-Ig is effective in ameliorating symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, and common variable immunodeficiency syndrome when caused by haploinsufficiency in CTLA-4 or dysregulated CTLA-4 trafficking, and in preventing rejection of renal transplants.3,14,15 Despite impressive results in these conditions, treatment with CTLA-4-Ig is not fully protective, and therefore, current efforts are focused on combining CTLA-4-Ig with blockade of additional costimulatory receptors.16 The choice of the targeted costimulatory receptor will be influenced by a number of factors, including the dynamics of receptor and ligand expression, the presence of the receptor on a disease-relevant cell population, and the extent of functional diversity and redundancy between the various receptors. Therefore, a thorough understanding of the biology of costimulatory receptors and knowledge of their relevance to human disease are critical for selecting appropriate receptors for therapeutic intervention.

In this review, we summarize recent advances in the understanding of the immunobiology of OX40 and CD27 focusing on their role in human immune responses and their potential as targets for promoting antitumor immunity.

Structure of OX40, CD27, and their ligands

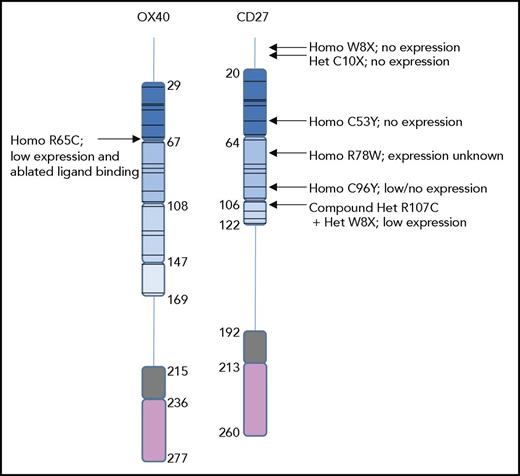

In common with other members of the TNFRSF, OX40 (also known as TNFRSF4 or CD134) and CD27 (TNFRSF7) are type I transmembrane glycoproteins characterized by the presence of cysteine-rich domains (CRDs), which typically incorporate 3 disulfide bridges.17 Although human OX40 and CD27 are similar in length (277 and 260 residues, respectively) and exhibit some homology at the protein level, OX40 contains 4 CRDs, whereas CD27 contains only 317 (see Figure 1). Both mature proteins are larger than predicted (∼30 kDa) at 50 to 55 kDa, because of N-linked and O-linked glycosylation.18,,,-22

Structures of human OX40 and CD27 and locations of clinically described mutations. Schematic of full-length human OX40 and CD27 (including the signal peptides), showing CRDs 1, 2, 3, and in the case of OX40 also CRD 4 in progressively lighter shades of blue with positions of the CRDs shown as defined from crystallographic studies. Residues within the extracellular region of the receptor but that do not fall within a CRD are indicated by a vertical line, the transmembrane regions are shown in gray, and cytoplasmic residues are represented in pink. Amino acid numbers are indicated, and positions of cysteine residues within the CRDs are shown by a horizontal line. Positions of mutations described in patients and their impact on receptor expression where known are also shown. Why a heterozygous C10X mutation should result in absent CD27 expression is unclear; the C10X heterozygous mutation in the patient’s father resulted in only partial loss of CD27. It is likely that the patient’s mother, who also exhibited defects in CD27 expression, carries an unidentified mutation elsewhere in the genome (no mutations could be identified in the CD27 locus) that causes suboptimal CD27 expression. Thus, in reality the patient is likely to be a compound heterozygote having inherited the C10X mutation from her father and an unknown mutation from her mother (see Alkhairy et al35 ).

Structures of human OX40 and CD27 and locations of clinically described mutations. Schematic of full-length human OX40 and CD27 (including the signal peptides), showing CRDs 1, 2, 3, and in the case of OX40 also CRD 4 in progressively lighter shades of blue with positions of the CRDs shown as defined from crystallographic studies. Residues within the extracellular region of the receptor but that do not fall within a CRD are indicated by a vertical line, the transmembrane regions are shown in gray, and cytoplasmic residues are represented in pink. Amino acid numbers are indicated, and positions of cysteine residues within the CRDs are shown by a horizontal line. Positions of mutations described in patients and their impact on receptor expression where known are also shown. Why a heterozygous C10X mutation should result in absent CD27 expression is unclear; the C10X heterozygous mutation in the patient’s father resulted in only partial loss of CD27. It is likely that the patient’s mother, who also exhibited defects in CD27 expression, carries an unidentified mutation elsewhere in the genome (no mutations could be identified in the CD27 locus) that causes suboptimal CD27 expression. Thus, in reality the patient is likely to be a compound heterozygote having inherited the C10X mutation from her father and an unknown mutation from her mother (see Alkhairy et al35 ).

Unlike OX40, and indeed all other members of the TNFRSF, membrane-bound CD27 is a disulfide-linked homodimer because of interactions in cis between cysteine residues at position 165 of the mature protein,18,22 although monomeric CD27 can be detected in serum under inflammatory conditions.23 Soluble CD27, at 32 kDa, is smaller than the membrane-bound form from which it is processed in activated T cells.24,-26 Interestingly, the 32 kDa form can also be detected on the surface of activated T cells likely as part of a heterodimeric complex between processed 32 kDa and mature 50 kDa protomers.24,27 Although soluble OX40 has also been detected in human serum, levels are at least 30-fold lower than reported concentrations of serum CD27.28,-30

The only known ligands for OX40 and CD27 are OX40L (TNFSF4) and CD70 (TNFSF7), respectively. Both are type II transmembrane proteins and contain the conserved tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–homology domain that enables trimerization.17 Many TNFRSF ligands can be cleaved to generate a soluble form,17 and although the details of its generation are not clear, soluble OX40L, but not CD70 to our knowledge, can be detected in serum at ng/mL levels.28 The crystal structure of trimeric human OX40L reveals a splayed pyramidal-type form with a relatively small area of interaction between protomers.20 On activation, 3 OX40 molecules bind to the OX40L trimer, which is typical for ligand-receptor pairings in the TNFRSF31 ; in the case of OX40, CRDs 1, 2, and 3 all interact with OX40L.20 Although the crystal structure of the hCD27/CD70 complex has not been solved, modeling based on the crystal structures of a CD27 extracellular region/antibody complex and the homologous CD40/CD40L complex suggests that a similar 3:3 binding configuration occurs with CRD2 of CD27 interacting with CD70.21 However, higher-order oligomers, possibly dimers of trimers, are more effective ligands for both OX40 and CD27 activation.32,33

Naturally arising mutations that impair immunity have been identified in both human OX40 and CD27. For OX40, introduction of an additional cysteine residue within CRD1 (R65C; numbering includes the signal sequence) results in a substantial reduction in surface OX40 on activated human T cells and intracellular accumulation of a misfolded form of the protein.34 Furthermore, the residual surface-expressed R65C OX40 protein is incapable of binding to OX40L.34 Similarly for CD27, mutations C53Y, C96Y, and R107C, which fall in CRDs 1, 2, and 3, respectively, all contribute to reduced expression of CD2722,35 (see Figure 1). In contrast, although a patient with a mutation at R78W (in CRD2) showed defects in immunity consistent with impaired CD27 function, crystallographic studies suggest this is likely because of impaired interactions between CD27 and CD70 rather than a defect in CD27 expression.22,35

Expression patterns

OX40 and CD27

Both OX40 and CD27 are expressed predominantly by T cells, although expression patterns differ according to T-cell subset and differentiation/activation status. OX40 is transiently expressed by both human CD4+ and CD8+ T cells following TCR stimulation and is expressed more highly on CD4+ compared with CD8+ T cells in vitro and at tumor sites.36,,-39 Thus, both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells are potential targets of OX40-directed immunotherapeutic agents in cancer. Furthermore, studies have shown regulatory T cells (Tregs) to express more OX40 compared with conventional CD4+ T cells in multiple human tumors,38,,-41 raising the additional possibility of preferentially targeting the OX40hi population with depleting mAbs. Finally, OX40 has also been reported on human neutrophils (in which signaling supports survival) and murine, but not human to our knowledge, natural killer (NK) and NK T cells.42,43

CD27 is expressed on resting αβ CD4+ (Treg and conventional T cells) and CD8+ T cells and also a population of innate-like Vγ9Vδ2-expressing T cells with antitumor function.44 That CD27 is expressed constitutively on naïve T cells whereas OX40 requires TCR stimulation for expression suggests that CD27 may act earlier during priming than OX40. On human T cells, CD27 is downregulated on effector cells but is expressed at reasonable levels by stem-cell memory cells and central-memory-like cells.45 In contrast, terminally differentiated effector-memory RA T cells and effector-memory cells comprise mixed populations of both CD27+ and CD27− subsets; while CD27+ cells predominate in the effector-memory population, the effector-memory RA T cells subset is largely CD27−.46,47 For NK cells, loss of CD27 is similarly associated with the more effector-like CD56dim population, and even within the CD56bright subpopulation loss of CD27 is associated with greater lytic activity.48 CD27 has also been described on human B cells, including germinal center, memory, and plasma cells, but not naive or transitional B cells49,50 ; the function of CD27 on human B cells is poorly understood, although stimulation with CD70-transfected cells augments immunoglobulin G (IgG) production from human B cells in vitro.51 Importantly, and similarly to OX40, CD27 is expressed by both effector and regulatory T-cell populations at sites of immune pathology and cancer making both populations potential targets for CD27-targeting treatments.52,53

OX40L and CD70

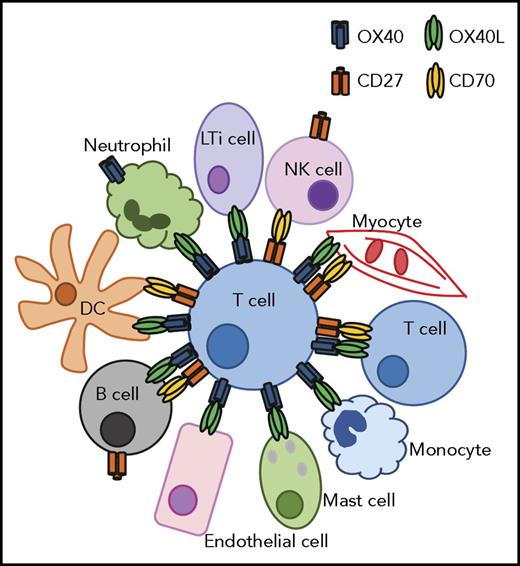

Expression of OX40L and CD70 is tightly controlled, and the influence of OX40 and CD27 in a given context is dependent on their availability. OX40L is induced on human dendritic cells (DCs) upon exposure to thymic stromal lymphopoietin, CD40L or Toll-like receptor (TLR) agonists, although the ability of CD40L and TLR agonists alone to induce OX40L varies between studies.54,-56 In addition, human monocytes, neutrophils, mast cells, lymphoid tissue inducer cells, smooth muscle cells, endothelial cells, and in vitro activated B cells can all express OX40L under appropriate conditions.34,57,,,,-62 Furthermore, human CD4+ and CD8+ T cells treated with anti-CD3/CD28-coated beads in the presence of IL-2 and transforming growth factor β1, or exposed to mature DCs, upregulate OX40L in vitro suggesting potential T-T costimulatory effects under inflammatory conditions.55,63 With regard to autoimmunity, expression of OX40L by monocytes has been shown to promote T follicular-helper cell polarization and pathogenesis in human lupus64 consistent with an association between TNFSF4 polymorphism and susceptibility to systemic lupus erythematosus and other autoimmune diseases.65 A similar mechanism may also contribute to the pathogenesis of sepsis given the enhanced OX40L expression by blood monocytes in septic patients and the requirement for macrophages for sepsis induction in mice.57 Patterns of CD70 expression are similar with CD70 absent on peripheral human DCs but upregulated following exposure to TNF-α, irradiation, or TLR agonists.55,66,-68 Like OX40L, other cell types can express CD70, including B and NK cells, myocytes, and CD4+ and CD8+ T cells.55,66,69,70 In mice, an antigen-presenting cell population of nonhematopoietic origin that constitutively expresses CD70 persists in the lamina propria, which likely supports local T-cell effector responses71 ; it is not known whether this same cell type exists in humans. Some of the interactions that may occur in vivo between CD27/CD70- and OX40/OX40L-expressing cells in humans are indicated in Figure 2.

Diagrammatic representation of potential interactions between OX40/OX40L- and CD27/CD70-expressing human cells in an inflamed environment. For simplicity, tumor cells are not shown here, although some tumor types may additionally express CD27 and CD70 (see the accompanying text for details).

Diagrammatic representation of potential interactions between OX40/OX40L- and CD27/CD70-expressing human cells in an inflamed environment. For simplicity, tumor cells are not shown here, although some tumor types may additionally express CD27 and CD70 (see the accompanying text for details).

Signaling by OX40 and CD27

OX40

For both OX40 and CD27, and in common with other members of the TNFRSF, transmembrane signaling is largely mediated through members of the TNF receptor associated factor (TRAF) family. TRAFs are trimeric proteins that interact with short motifs found in the cytoplasmic tails of ligand-bound trimeric TNFRSF receptors.72,-74 For OX40, initial interactions between the receptor and ligand stimulate movement of OX40 and TRAF2 into lipid rafts, an essential step for subsequent activation of NF-κB.75 OX40 also binds to TRAFs 1, 3, and 5 with all 4 TRAF-binding sites largely overlapping at sequence GGSFRTPIQEE in the human protein76,-78 ; it is not known whether TRAFs other than TRAF2 also colocalize with OX40 in rafts, nor what governs the likelihood of any given TRAF interacting with OX40. For CD40 a hierarchy of binding affinity exists in which TRAF2 binds more strongly than TRAFs 1, 3, or 6, and a similar hierarchy likely dictates patterns of TRAF binding to other members of the TNFRSF.72 Although both TRAF2 and TRAF5 can activate NF-κB signals downstream of OX40,76 knockdown of TRAF2 ablates canonical NF-κB activation and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and Akt recruitment in vitro,75,79 suggesting that TRAF2 engagement is a nonredundant event for some aspects of OX40-induced signaling. Interestingly, others have reported that OX40L-driven activation of the alternative NF-κB pathway at late time points is dependent on TRAF6,78 and it may be that different TRAF proteins confer distinct signaling events. Further downstream, the group of M. Croft has characterized an OX40-activated signalosome complex that includes TRAF2; IκB kinase α (IKKα), β, and γ; PKCθ; RIP1; CARMA1; BCL1; MALT1; the p85 subunit of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; and also Akt. Interestingly, this complex forms and drives NF-κB activation independent of antigen, although OX40-driven Akt phosphorylation is antigen dependent.79

CD27

CD27 similarly binds to TRAFs 2, 3, and 5, and binding of all 3 TRAFs is through the REEEGSTIPIQEDYR region of CD27.80,81 NF-κB activation by CD27 is also driven by TRAF2, and to a lesser extent TRAF5, and these same TRAFs are responsible for triggering JNK activation following CD27 engagement.81 Like OX40, CD27 triggers both the alternative and canonical NF-κB pathways, and activation of the alternative pathway by both OX40 and CD27 is inhibited by TRAF3.82

Although the canonical and alternative NF-κB signaling pathways are usually considered distinct,83 downstream of CD27 these pathways are tightly linked. Simplistically canonical NF-κB activation relies on activation of an IKKβ-containing complex leading to release of an active p65/relA transcriptional unit, whereas the alternative pathway is dependent on NF-κB–inducing kinase (NIK) stabilization, downstream IKKα activation, and release of a RelB/p52 dimer.83 Downstream of CD27, however, NIK is recruited to the receptor within minutes and is required for activation of both NF-κB pathways.84 For OX40, signaling is more conventional with alternative, but not canonical, NF-κB activation being dependent on NIK.85

Receptor engagement can also effect reverse signaling through CD70 and OX40L. For instance, OX40L signals induce c-jun and c-fos transcription in human endothelial cells, promote immunoglobulin secretion from human B cells, and augment human DC activation in vitro,60,86 although it should be pointed out that absence of OX40/OX40L signaling does not detectably hinder humoral responses in humans or mice.34,87 Similarly, reverse signaling by CD70 enhances aspects of human B-cell activation and NK cell survival and function in an allogeneic tumor setting.88,89 These data support the concept that reverse signaling via CD70 might be a potential target for cancer therapy, although this assertion is tempered with some caution given that CD70 is also aberrantly expressed by malignant B-cell tumors, in which it confers a proproliferative signal to tumor cells.90 Another point to consider is that agents designed to target OX40 or CD27 may conceivably exert additional biological effects through reducing the availability of OX40 and CD27, and thereby preventing reverse signaling through OX40L or CD70.

Functions of OX40 and CD27: insights from the clinic

OX40

In vitro studies have shown that stimulation with OX40L enhances proliferation and expression of effector molecules and cytokines by human T cells, although the effects on CD8+ T cells are largely indirect, being attributable to enhanced T-cell help provided by the CD4+ population.91,92 Further insights into the role of OX40 in human cells have been provided by the recent characterization of a 19-year-old patient with an R65C mutation in OX40 CRD1 that precludes OX40-OX40L signaling.34 This patient presented with Kaposi sarcoma (KS), a rare tumor of endothelial cell origin that arises secondary to chronic human herpes virus 8 infection. KS is often associated with underlying HIV infection, and endothelial cells taken from KS sites in HIV patients express abundant OX40L,34 suggesting that enhanced susceptibility to KS as a result of OX40 deficiency may result from locally defective endothelial-driven costimulation. This patient also presented with a history of susceptibility to the macrophage-infecting parasite Leishmania, potentially indicating a further requirement for OX40 in T cell-mediated activation of macrophages.34

Although overall immune cell frequencies and antibody responses were normal in this patient, a skewed lymphocyte repertoire was apparent with increased frequencies of naïve B and CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and a corresponding decrease in memory B and T cells notably in the effector-memory T cell compartment. Further analysis showed Treg frequencies (defined as CD4+CD25hiCD127lo) to be substantially diminished, whereas follicular T helper cell numbers (CD4+CD45RA−CXCR5+; important for supporting B-cell function) were unaltered. Although CD4+ T-cell recall responses to a number of different antigens were significantly decreased, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)–reactive CD8+ T cells were detected at normal frequencies confirming that OX40 is redundant for at least some CD8+ T-cell responses and perhaps providing some explanation for the lack of overt susceptibility to standard childhood infections in this patient.34

CD27

Similarly, CD27 agonists (either CD70 or agonist anti-CD27 mAb) costimulate human αβ as well as γδ T cells to undergo proliferation and cytokine production in vitro,44,67,93 although CD27-driven CD8+ T-cell activation can occur directly without a requirement for CD4+ T cells.67 The capacity of CD27 to directly stimulate CD8+ T cells, coupled with its constitutive expression on naïve T cells, may make it essential for the clearance of EBV infection because patients which lack functional CD27 or CD70 typically present with EBV infection in childhood and associated Hodgkin lymphoma,35,94,-96 whereas OX40 deficiencies had no apparent effect on the EBV-reactive CD8+ T-cell population (see “OX40” in “Functions of OX40 and CD27: insights from the clinic”). Furthermore, patients with defects in CD27 (see also Figure 1) or CD70 report a history of persistent infections throughout childhood95,96 suggesting a more severe phenotype compared with OX40 deficiency. Investigation of the lymphocyte compartment in CD27/CD70-deficient patients revealed a paucity of memory B and CD4+ and CD8+ T cells to varying extents and hypogammaglobulinemia (consistent with CD27 signals supporting IgG production in vitro51 ), although the frequency of Tregs was unchanged.95,96 Interestingly, and despite the clear lack of EBV immunity in these patients, T-cell proliferative responses to other mitogens were largely normal95,96 suggesting that CD70, which is upregulated on B cells in response to EBV infection,95 is important for T cell–mediated immunosurveillance of B cells when a robust immune response is required to counter massive B-cell proliferation as is the case during EBV infection. In contrast, the ability of these patients to mount successful T-cell responses to other common pathogens and childhood vaccines suggests that in situations where antigen is presented by DCs, the absence of CD27-CD70 may not be limiting.95

Manipulating OX40 and CD27 signals in cancer

OX40

A number of preclinical studies support that mAbs targeting OX40 and CD27 can promote T-cell activation and antitumor immunity (reviewed in Aspeslagh et al97 and Croft43 ). For agonistic anti-mouse OX40 mAb (clone OX86; rat IgG1) antitumor activity was shown to be attributable, first, to restored local DC function as a consequence of Treg inhibition and, second, to direct agonist activity toward the effector population.98,99 A study in 2014 further identified that OX86 depletes tumor-resident Tregs but not CD8+ T cells, likely because of the preferential expression of OX40 on Tregs compared with effector T cells in the tumor100 ; a version of this antibody optimized to bind activatory Fc receptors (FcRs), which have been associated with mAb-mediated cell depletion in other settings, similarly caused tumor rejection and a higher local CD8+/Treg ratio largely as a result of Treg loss.100 Given the higher expression of OX40 on Tregs compared with effector T cells in human tumors (see “OX40 and CD27” in “Expression patterns”), anti-OX40 mAbs with depleting activity may be similarly effective in the clinic. However, purely agonistic mAbs with no depleting activity may also be of benefit. In the clinic, anti-OX40 clone 9B12 has been shown to induce expression of the proliferation marker Ki-67 on effector CD4+ and CD8+ T cells yet does not do so on Tregs, and Treg depletion was not noted.101 Nonetheless, augmented tumor-specific immune responses have been observed with this antibody in 2 melanoma patients.101

The effects of OX40 agonists on human Tregs remain unclear. OX40 is required for local Treg maintenance in a murine model of colitis, and enforced OX40 stimulation has been reported to enhance human Treg (and effector T cell) proliferation.102,103 However, others have shown that brief exposure of Tregs to agonist anti-OX40 mAbs directly inhibits their suppressive activity, and that Tregs are more sensitive than other T-cell subsets to apoptosis induced by prolonged exposure to high-dose anti-OX40 mAbs.104 It is therefore possible that agonistic anti-OX40 mAbs may promote expansion of Tregs (although for 9B12 this appears not to be the case101 ), suppress their function, or induce their apoptosis.

CD27

Enforced CD27 signals similarly prevent tumor growth. For instance, CD70 overexpressing mice, and mice constitutively expressing CD70 on CD11c-positive cells, mount greater tumor-specific CD8+ T-cell responses and reject tumor cells more effectively than their wild-type counterparts.105,106 Furthermore, approximately a third of patients with germ line deficiencies in CD27 or CD70 present with Hodgkin lymphoma or diffuse large B-cell lymphoma,35,95,96 and somatic mutations or deletions in CD70 are frequently observed in diffuse large B-cell and Burkitt lymphomas,107,108 confirming that CD27/CD70 signals also contribute to antitumor immunity in humans. We and others have shown that agonist mAbs targeting CD27 bypass the requirement for CD40 signaling and CD4+ T-cell help to promote CD8+ T-cell–dependent tumor rejection in mice,109,-111 consistent with the dependency of CD40-mediated DC licensing and subsequent CD8+ T-cell priming on CD70.112,,-115 Within the tumor environment, an agonist anti-mouse CD27 mAb promotes the local accumulation of tumor-specific and interferon-γ (IFN-γ) producing CD8+ T cells,111 and varlilumab, an anti-human CD27 mAb, similarly causes CD8+ T-cell–dependent tumor rejection in human-CD27 transgenic mice and enhances the expansion of human T cells in vitro.93,116 As is becoming increasingly apparent for mAb therapies, the efficacy of varlilumab is dependent on its interaction with FcRs in the host.116

With regard to the effects of CD27 stimulation on Tregs, varlilumab only moderately increased the proliferation of human Tregs, although this was likely secondary to increased availability of IL-2 in this in vitro mixed culture assay.93 In vivo, enforced stimulation with agonist anti-CD27 mAbs reduces Treg frequency in a murine tumor,111 and varlilumab similarly reduces the frequency of Tregs in the peripheral blood of cancer patients.117 Of note, the most suppressive human Tregs express the highest levels of CD27,118,119 and it seems likely that these would therefore be preferentially depleted by appropriate anti-CD27 mAbs, although this remains conjecture.

Intriguingly, varlilumab acts as a direct T-cell agonist and also depletes human lymphoma cells in immune-deficient mice93,120 ; whether the mechanism of action is linked to the relative expression levels of CD27 on the target cell population and/or the local FcR milieu remains to be clarified. Clinically, early indications are that varlilumab is well tolerated and exhibits biological activity consistent with activation of the CD27 pathway, including chemokine induction, particularly IP-10 (CXCL10), and expansion of activated and effector T cells.117 Importantly, this first-in-human trial shows that varlilumab is clinically active, achieving responses similar to those observed with anti-OX40.101

CD70

Also of relevance here, CD70 is aberrantly expressed by some tumor types including renal-cell carcinoma, in which CD70 drives terminal differentiation of responding T cells,121 and in chronic lymphocytic leukemia, in which CD70 confers proliferative signals to the tumor.90 In addition, human chronic myeloid leukemia stem cells receive proliferative signals via the Wnt pathway following CD27 engagement,122 and acute myeloid leukemia stem cells were recently shown to express both CD27 and CD70, an interaction that promotes their survival.123 Encouragingly, a blocking anti-CD70 mAb prevented the growth of acute myeloid leukemia blast cells in a xenotransplantation model.123 These studies suggest that mAbs that either block CD70 signals or deplete CD70+ tumor cells would be an appropriate therapeutic strategy for some tumors. To date, an anti-CD70 mAb (MDX-1203; Table 1) is well tolerated in renal carcinoma and NHL patients with some evidence for improved stabilization of disease at higher doses.124

Ongoing clinical trials targeting OX40, CD27, and CD70 in cancer

| Target . | Agent . | Delivered with . | Trial number . | Tumor type . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OX40 | MEDI6469 (9B12) | Vaccine or adjuvant | NCT01644968 | Various advanced |

| Surgical resection | NCT02274155 | Head and neck | ||

| Surgical resection | NCT02559024 | Colorectal | ||

| Radiation | NCT01862900 | Breast | ||

| Radiotherapy and cyclophosphamide | NCT01303705 | Prostate | ||

| MEDI0562 | Monotherapy | NCT02318394 | Solid tumors | |

| Anti-CTLA-4 or anti-PD-L1 | NCT02705482 | Solid tumors | ||

| PF-04518600 | Alone or with anti-4-1BB | NCT02315066 | Solid tumors | |

| Anti-PD-L1 +/− anti-4-1BB | NCT02554812 | Solid tumors | ||

| Tyrosine-kinase inhibitor | NCT03092856 | Renal | ||

| INCAGN01949 | Alone | NCT02923349 | Solid tumors | |

| BMS-986178 | Alone or with anti-PD-1/anti-CTLA-4 | NCT02737475 | Solid tumors | |

| MOXR0916 (RG7888) | Alone | NCT02219724 | Solid tumors | |

| Anti-PD-L1 | NCT03029832 | Urothelial | ||

| Anti-PD-L1 +/− anti-VEGF | NCT02410512 | Solid tumors | ||

| GSK3174998 | Alone or with anti-PD-1 | NCT02528357 | Solid tumors | |

| MEDI6383 | Alone or with anti-PD-L1 | NCT02221960 | Solid tumors | |

| CD27 | Varlilumab (CDX-1127) | Alone | NCT01460134 | Hematologic or solid |

| Peptide vaccine and adjuvant | NCT02924038 | Glioma | ||

| Peptide vaccine | NCT02270372 | Ovarian and breast | ||

| Anti-PD-1 | NCT02335918 | Refractory | ||

| Anti-PD-1 | NCT03038672 | B-cell lymphoma | ||

| Antitumor mAb-drug conjugate | NCT02302339 | Melanoma | ||

| CD70 | SGN-CD70A | Alone | NCT02216890 | CD70+ renal or lymphoma |

| SGN-75 | Alone | NCT01015911 | CD70+ renal or NHL | |

| ARGX-110 | Alone | NCT01813539 | CD70+ advanced tumors | |

| Alone or with chemotherapy | NCT02759250 | Nasopharyngeal | ||

| MDX-1203 | Alone | NCT00944905 | CD70+ renal or NHL |

| Target . | Agent . | Delivered with . | Trial number . | Tumor type . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OX40 | MEDI6469 (9B12) | Vaccine or adjuvant | NCT01644968 | Various advanced |

| Surgical resection | NCT02274155 | Head and neck | ||

| Surgical resection | NCT02559024 | Colorectal | ||

| Radiation | NCT01862900 | Breast | ||

| Radiotherapy and cyclophosphamide | NCT01303705 | Prostate | ||

| MEDI0562 | Monotherapy | NCT02318394 | Solid tumors | |

| Anti-CTLA-4 or anti-PD-L1 | NCT02705482 | Solid tumors | ||

| PF-04518600 | Alone or with anti-4-1BB | NCT02315066 | Solid tumors | |

| Anti-PD-L1 +/− anti-4-1BB | NCT02554812 | Solid tumors | ||

| Tyrosine-kinase inhibitor | NCT03092856 | Renal | ||

| INCAGN01949 | Alone | NCT02923349 | Solid tumors | |

| BMS-986178 | Alone or with anti-PD-1/anti-CTLA-4 | NCT02737475 | Solid tumors | |

| MOXR0916 (RG7888) | Alone | NCT02219724 | Solid tumors | |

| Anti-PD-L1 | NCT03029832 | Urothelial | ||

| Anti-PD-L1 +/− anti-VEGF | NCT02410512 | Solid tumors | ||

| GSK3174998 | Alone or with anti-PD-1 | NCT02528357 | Solid tumors | |

| MEDI6383 | Alone or with anti-PD-L1 | NCT02221960 | Solid tumors | |

| CD27 | Varlilumab (CDX-1127) | Alone | NCT01460134 | Hematologic or solid |

| Peptide vaccine and adjuvant | NCT02924038 | Glioma | ||

| Peptide vaccine | NCT02270372 | Ovarian and breast | ||

| Anti-PD-1 | NCT02335918 | Refractory | ||

| Anti-PD-1 | NCT03038672 | B-cell lymphoma | ||

| Antitumor mAb-drug conjugate | NCT02302339 | Melanoma | ||

| CD70 | SGN-CD70A | Alone | NCT02216890 | CD70+ renal or lymphoma |

| SGN-75 | Alone | NCT01015911 | CD70+ renal or NHL | |

| ARGX-110 | Alone | NCT01813539 | CD70+ advanced tumors | |

| Alone or with chemotherapy | NCT02759250 | Nasopharyngeal | ||

| MDX-1203 | Alone | NCT00944905 | CD70+ renal or NHL |

NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

A summary of current clinical trials targeting OX40 and CD27/CD70 can be found in Table 1.

Combining OX40 and CD27 mAbs with other agents

Although agonist mAbs targeting OX40 and CD27 can impart tumor protection in mice, these have limited effects in poorly immunogenic settings.110,125 There is therefore increasing interest in combining these mAbs with additional strategies to, for example, enhance antigen availability, augment inflammation, or inhibit immunosuppressive signals. Thus, cotargeting TLRs, or the addition of IFN-α, profoundly enhances the effects of agonist CD27 mAb for expansion of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells in mice dependent on the direct effects of type I IFN on CD8+ T cells.126 In addition, agonist anti-OX40 and anti-CD27 mAbs synergize with PD-L1 blockade to enhance the proliferation and function of exhausted CD8+ T cells.127 Finally, given the preferential activation of human CD4+ T cells by OX40 yet the ability of CD27 agonists to directly promote CD8+ T-cell responses,67,92 it may be that coincident OX40 and CD27 activation would also synergize to promote stronger T-cell immunity compared with activation achieved through either of the individual receptors. In these exciting times for cancer immunotherapy, combining mAbs targeting CD27, OX40, and/or checkpoint-blocking mAbs thus represents a particularly promising approach to achieve even greater therapeutic success in a variety of cancers.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to apologize to those whose work we have been unable to cite because of space limitations.

Authorship

Contribution: S.L.B., A.R., and A.A.-S. wrote and edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: A.A.-S. receives funding from Celldex Therapeutics Inc. S.L.B. is supported by Celldex Therapeutics Inc. A.R. declares no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Sarah L. Buchan, Cancer Sciences Unit, Faculty of Medicine, University of Southampton, Southampton SO16 6YD, United Kingdom; e-mail: slb@soton.ac.uk; and Aymen Al-Shamkhani, Cancer Sciences Unit, Faculty of Medicine, University of Southampton, Southampton SO16 6YD, United Kingdom; e-mail: aymen@soton.ac.uk.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal