TO THE EDITOR:

Retinoic acid receptor γ (RARG) is a member of the nuclear receptor superfamily and shares high homology (90%) with retinoic acid receptor α (RARA) and retinoic acid receptor β (RARB).1 So far, little is known about RARB or RARG fusion. Such et al reported the first case of RARG fusion in a male patient resembling classical acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL).2 The partner gene of RARG was identified as NUP98.2 Recently, Ha et al identified the PML gene as the second partner gene in a female APL patient.3 Here, we present the first recurrent RARG fusions in 2 acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients mimicking APL.

Patient 1, a 48-year-old woman, was admitted because of dizziness, fatigue, and hypermenorrhea. Blood tests showed a hemoglobin level of 42 g/L, a platelet count of 92 × 109/L, and a white blood cell count of 0.81 × 109/L. Fibrinogen and d-dimer levels were 1.67 g/L (reference, 2.00-4.00 g/L) and 56.8 μg/mL (reference, 0.00-0.55 μg/mL), respectively. Prothrombin time and partial thromboplastin time were 13.5 seconds (reference, 10.5-13.0 seconds) and 25.3 seconds (reference, 23-35 seconds), respectively. Bone marrow (BM) smear showed hypercellularity, with 89% hypergranular promyelocytes with Auer rods (Figure 1A). The blasts were positive for CD13, CD33, and myeloperoxidase, partially positive for CD9 and CD64, but negative for HLA-DR, CD117, CD34, CD14 and CD11b by flow cytometry (supplemental Figure 1A, available on the Blood Web site). This patient was diagnosed with suspicion of APL. A BM sample obtained at diagnosis was processed after a short-term culture (24 hours) following standard RHG banding procedures. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis was performed using a PML-RARA dual-color dual-fusion probe (Abbott Molecular, Des Plaines, IL) according to the manufacturer’s protocols (Figure 1B). Multiplex quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was performed to detect 51 fusion transcripts, including PML-RARA, PLZF-RARA, NUMA1-RARA, STAT5B-RARA, PAKARIA-RARA, and NPM1-RARA. However, the t(15;17)(q24;q21) translocation was not detected by karyotyping; instead, a tetraploidy karyotype of 92, XXXX[2] was identified (Figure 1C). Both RT-PCR and FISH failed to detect the PML-RARA fusion transcript (Figure 1B). We performed targeted next-generation sequencing of the entire coding sequences of 382 known or putative mutational gene targets in hematologic malignancies and identified DNMT3A-G587fs mutation in this patient. She was initially treated with all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) (30 mg/d, days 1-35) and arsenic trioxide (10 mg/d, days 1-15) combined with idarubicin (6 mg/m2 per day, days 9, 13, and 14) and showed no response. She then received therapy with a course of idarubicin (6 mg/m2 per day, days 1, 3, and 5), cytosine arabinoside (12 mg/m2, hypodermic injection, every 12 hours, days 1-14), and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, 250 μg, hypodermic injection, daily) combined with ATRA (30 mg/d, days 1-14) and arsenic trioxide (10 mg/d, days 1-14) and failed to achieved remission. Afterward, she received an induction therapy of decitabine (20 mg/m2, days 1-5). Unfortunately, BM smear showed no response. She refused further chemotherapy and died of cerebral hemorrhage in July of 2017.

Molecular characterization of CPSF6-RARG fusions. (A) May-Grünwald-Giemsa staining showing hypergranular promyelocytes with Auer rods in the diagnostic BM aspirate from patient 1. Black arrow points to Auer rods. Original magnification ×1000. (B) Interphase FISH using the PML-RARA dual-color, dual-fusion translocation probe revealed absence of PML-RARA for patient 1. (C) Karyotypic analysis performed on the diagnostic BM revealed tetraploidy karyotype of 92, XXXX[2] for patient 1. (D) May-Grünwald-Giemsa staining showing hypergranular promyelocytes in the diagnostic BM aspirate from patient 2. Black arrow points to Auer rods. Original magnification ×1000. (E) Interphase FISH using the RARA dual-color break-apart probe showing 2 yellow signals corresponding to an intact RARA gene for patient 2. (F) Karyotypic analysis performed on the diagnostic BM revealed del(12)(p12)[2]/46,XX[18] for patient 2. (G) Whole-genome sequencing analysis results revealed that the breakpoint (red arrow) in 12q15 was located at intron 4 of the CPSF6 gene in both patients. There are 2 breakpoints (red arrow) in RARG gene, which are located at intron 3 and the 5′ untranslated region. The 3′ region of the RARG gene (from exon 1 or exon 4 to exon 9) was reversed and fused in-frame with the 5′ region of the CPSF6 gene (from exon 1 to exon 4) in both patients. (H) Electrophoresis of RT-PCR products from 2 patients showed 2 types of CPSF6-RARG fusion transcripts. (I) Partial nucleotide sequences surrounding the junctions of the 2 types of CPSF6-RARG fusion transcripts. The fusion transcript from patient 1 was a fusion between exon 4 of the CPSF6 gene with exon 4 of the RARG gene. The fusion transcript from patient 2 was a fusion between exon 4 of the CPSF6 gene with exon 1 of the RARG gene. (J) Schematic diagram of CPSF6, RARG, CPSF6-RARG-S, and CPSF6-RARG-L fusion proteins. CPSF6-RARG-L harbored a point mutation from 805G to C in patient 2, resulting in a change of glycine to arginine at 269. The breakpoint is indicated by a red line. UTR, untranslated region.

Molecular characterization of CPSF6-RARG fusions. (A) May-Grünwald-Giemsa staining showing hypergranular promyelocytes with Auer rods in the diagnostic BM aspirate from patient 1. Black arrow points to Auer rods. Original magnification ×1000. (B) Interphase FISH using the PML-RARA dual-color, dual-fusion translocation probe revealed absence of PML-RARA for patient 1. (C) Karyotypic analysis performed on the diagnostic BM revealed tetraploidy karyotype of 92, XXXX[2] for patient 1. (D) May-Grünwald-Giemsa staining showing hypergranular promyelocytes in the diagnostic BM aspirate from patient 2. Black arrow points to Auer rods. Original magnification ×1000. (E) Interphase FISH using the RARA dual-color break-apart probe showing 2 yellow signals corresponding to an intact RARA gene for patient 2. (F) Karyotypic analysis performed on the diagnostic BM revealed del(12)(p12)[2]/46,XX[18] for patient 2. (G) Whole-genome sequencing analysis results revealed that the breakpoint (red arrow) in 12q15 was located at intron 4 of the CPSF6 gene in both patients. There are 2 breakpoints (red arrow) in RARG gene, which are located at intron 3 and the 5′ untranslated region. The 3′ region of the RARG gene (from exon 1 or exon 4 to exon 9) was reversed and fused in-frame with the 5′ region of the CPSF6 gene (from exon 1 to exon 4) in both patients. (H) Electrophoresis of RT-PCR products from 2 patients showed 2 types of CPSF6-RARG fusion transcripts. (I) Partial nucleotide sequences surrounding the junctions of the 2 types of CPSF6-RARG fusion transcripts. The fusion transcript from patient 1 was a fusion between exon 4 of the CPSF6 gene with exon 4 of the RARG gene. The fusion transcript from patient 2 was a fusion between exon 4 of the CPSF6 gene with exon 1 of the RARG gene. (J) Schematic diagram of CPSF6, RARG, CPSF6-RARG-S, and CPSF6-RARG-L fusion proteins. CPSF6-RARG-L harbored a point mutation from 805G to C in patient 2, resulting in a change of glycine to arginine at 269. The breakpoint is indicated by a red line. UTR, untranslated region.

Patient 2, a 51-year-old woman, was admitted because of fever, chest pain, and paraphasia. Blood tests showed a hemoglobin level of 65 g/L, a platelet count of 45 × 109/L, and a white blood cell count of 20.15 × 109/L. Fibrinogen, fibrin degradation products, and d-dimer levels were 1.66 g/L (reference, 2.00-4.00 g/L), 341.2 μg/mL (reference, 0.00-5.00 μg/mL), and 189.4 μg/mL (reference, 0.00-0.55μg/mL), respectively. Prothrombin time and partial thromboplastin time were 13 seconds (reference, 10.5-13.0 seconds) and 35.2 seconds (reference, 23-35 seconds) respectively. BM smear showed hypercellularity with 87.5% hypergranular promyelocytes (Figure 1D). The blasts were positive for CD13, CD33, cytoplasmic myeloperoxidase, and CD9, partially positive for CD34, but negative for HLA-DR, CD2, CD7, CD10, CD11c, CD14, and CD38 by flow cytometry (supplemental Figure 1B). Both quantitative RT-PCR and FISH failed to detect the PML-RARA fusion transcript from the BM sample (Figure 1E). The t(15;17)(q24;q21) was not detected by karyotyping; instead, a del(12)(p12)[2]/46,XX[18] was detected (Figure 1F). Targeted next-generation sequencing identified WT1 and K-RAS mutations in this patient. She was initially treated with ATRA (25 mg/m2/ d1-d28, 15 mg/m2, d29-d42) and daunorubicin (60 mg/m2, days 1-3). Although the coagulation function returned to normal, BM aspiration at days 14 and 42 showed no response. She then received a course of daunorubicin and Ara-C chemotherapy (daunorubicin 60 mg/m2, days 1-3, and Ara-C 100 mg/m2, days 1-7) and achieved morphologic remission. The patient received 2 courses of high-dose cytarabine consolidation therapy followed by 2 courses of standard 7+3 chemotherapy. She remained complete remission until the last follow-up in November of 2017.

Cytogenetic, FISH, and RT-PCR analysis demonstrated the absence of t(15;17)(q24;q21) and PML/RARA in both patients. In order to characterize the molecular aberrations, we performed RNA sequencing on the total RNA of BM samples and found a recurrent CPSF6-RARG fusion in both patients (supplemental Figure 2). Whole-genome sequencing analysis results revealed that the breakpoint in 12q15 were located at the intron 4 of CPSF6 in both patients (Figure 1G). There are 2 breakpoints in the intron 3 or 5′ untranslated region and telomeric of exon 9 of RARG (Figure 1G). The 3′ region of RARG (from exon 1 or exon 4 to exon 9) was reversed and fused in-frame with the 5′ region of CPSF6 gene (from exon 1 to exon 4) (Figure 1G). RT-PCR and Sanger sequencing analysis confirmed CPSF6-RARG in-frame fusion in both patients (Figure 1H-J). The longer transcription, named CPSF6-RARG-L, harbored a point mutation from 805G to C in patient 2, resulting in a change from glycine to arginine at 269 (Figure 1J). The CPSF6-RARG fusion protein in both patients combines the RNA recognition motif domain of CPSF6 and the main RARG domains of DBD and LBD (Figure 1J). Compared with NUP98-RARG1 and PML-RARG,2 the breakpoint of RARG in patient 1 is consistent with NUP98-RARG, and the breakpoint of RARG in patient 2 is the same as the PML-RARG transcript.

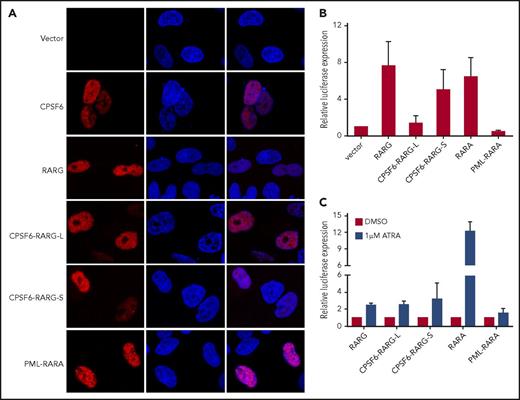

To compare the cellular localization of CPSF6-RARG fusion protein with wild-type RARG and CPSF6, myc-tagged versions of these proteins were expressed in HeLa cells. Immunofluorescence analysis showed that myc-RARG and myc-CPSF6 have a diffused distribution in nucleus, whereas CPSF6-RARG-L and CPSF6-RARG-S exhibit a similar intranuclear distribution (Figure 2A). Furthermore, we examined the transcriptional properties of CPSF6-RARG-L and CPSF6-RARG-S. RARE luciferase reporter experiments were performed. Compared with RARG, CPSF6-RARG-L repressed the expression of luciferase reporter to a level comparable to PML-RARA, whereas CPSF6-RARG-S showed a comparable transcriptional activity with RARA or RARG (Figure 2B). In the presence of ATRA, both CPSF6-RARG fusions and RARG showed weak luciferase induction, which was in marked contrast with the significant luciferase induction by RARA (Figure 2C). These results indicated that both CPSF6-RARG fusions may exert similar transcriptional effects on RARG downstream targets.

Cellular location and transcriptional effects of CPSF6-RARG fusion protein. (A) HeLa cells were transfected with pcDNA3.1 expression plasmids of vehicle (vector), myc-CPSF6, myc-RARG, myc-CPSF6-RARG-L, myc-CPSF6-RARG-S, and myc-PML-RARA, respectively. Immunofluorescence was performed with myc-tag antibody. Both CPSF6-RARG fusions were predominantly expressed in the nucleus. Original magnification ×630. (B) 293T cells were transfected with RARE Cignal reporter and pcDNA3.1 expression plasmids of vehicle (vector), RARG, CPSF6-RARG-L, CPSF6-RARG-S, PML-RARA, and RARA, respectively. Relative firefly luciferase expression of cell lysates was normalized to Renilla luciferase. The expression of vector control was set to 1. (C) 293T cells transfected with RARE Cignal reporter and the indicated constructs were treated with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or 1 μM ATRA for 48 hours. Relative firefly luciferase expression of cell lysates was normalized to Renilla luciferase. Ratios were normalized against the cells treated with DMSO. n = 4 separate experiments (A-C). All data are presented as mean ± SD.

Cellular location and transcriptional effects of CPSF6-RARG fusion protein. (A) HeLa cells were transfected with pcDNA3.1 expression plasmids of vehicle (vector), myc-CPSF6, myc-RARG, myc-CPSF6-RARG-L, myc-CPSF6-RARG-S, and myc-PML-RARA, respectively. Immunofluorescence was performed with myc-tag antibody. Both CPSF6-RARG fusions were predominantly expressed in the nucleus. Original magnification ×630. (B) 293T cells were transfected with RARE Cignal reporter and pcDNA3.1 expression plasmids of vehicle (vector), RARG, CPSF6-RARG-L, CPSF6-RARG-S, PML-RARA, and RARA, respectively. Relative firefly luciferase expression of cell lysates was normalized to Renilla luciferase. The expression of vector control was set to 1. (C) 293T cells transfected with RARE Cignal reporter and the indicated constructs were treated with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or 1 μM ATRA for 48 hours. Relative firefly luciferase expression of cell lysates was normalized to Renilla luciferase. Ratios were normalized against the cells treated with DMSO. n = 4 separate experiments (A-C). All data are presented as mean ± SD.

It was reported that an artificial PML-RARG fusion showed an oncogenic potential comparable to that of PML-RARA.4,5 Therefore, CPSF6-RARG might be assumed to have similar oncogenic functions. The partner gene also plays a crucial role in the biological properties of fusion proteins. CPSF6 is one subunit of a cleavage factor required for 3′ RNA cleavage and polyadenylation processing. CPSF6 and CPSF5 form a protein complex binding to RNA substrates that promotes RNA looping.6 CPSF6 was reported to be fused with PDGFRB in a patient with myeloproliferative neoplasm with eosinophilia7 and FGFR1 in a patient with 8p11 myeloproliferative syndrome.8

In summary, we identified novel CPSF6-RARG fusions in 2 patients with AML resembling APL. This is the first report of a recurrent fusion transcript involving the RARG gene. It will be necessary to conduct further studies to determine the prevalence and leukemogenic mechanisms of CPSF6-RARG fusion in AML mimicking APL.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions, the National Key Natural Science Foundation of China (81730003), the Natural Science Foundation of China (81570139, 81700139, 81700040, and 81400114), the National Key Research and Development Program (2016YFC0902800, 2017YFA0104500), the Innovation Capability Development Project of Jiangsu Province (BM2015004), the Natural Science Fund of Jiangsu Province (BK20170360), and the Jiangsu Province Natural Science Fund (BE2015639).

Authorship

Contribution: S.C. was the principal investigator; T.L., L.W., Y.W., and H.Y. performed most of the experiments; L.Y., Y.X., and J.C. performed clinical analysis; and S.C., D.W., and C.R. wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Suning Chen, Jiangsu Institute of Hematology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University, Shizi St 188, Suzhou 215006, People’s Republic of China; e-mail: chensuning@suda.edu.cn.

References

Author notes

T.L., L.W., H.Y., and Y.W. contributed equally to this study.

![Figure 1. Molecular characterization of CPSF6-RARG fusions. (A) May-Grünwald-Giemsa staining showing hypergranular promyelocytes with Auer rods in the diagnostic BM aspirate from patient 1. Black arrow points to Auer rods. Original magnification ×1000. (B) Interphase FISH using the PML-RARA dual-color, dual-fusion translocation probe revealed absence of PML-RARA for patient 1. (C) Karyotypic analysis performed on the diagnostic BM revealed tetraploidy karyotype of 92, XXXX[2] for patient 1. (D) May-Grünwald-Giemsa staining showing hypergranular promyelocytes in the diagnostic BM aspirate from patient 2. Black arrow points to Auer rods. Original magnification ×1000. (E) Interphase FISH using the RARA dual-color break-apart probe showing 2 yellow signals corresponding to an intact RARA gene for patient 2. (F) Karyotypic analysis performed on the diagnostic BM revealed del(12)(p12)[2]/46,XX[18] for patient 2. (G) Whole-genome sequencing analysis results revealed that the breakpoint (red arrow) in 12q15 was located at intron 4 of the CPSF6 gene in both patients. There are 2 breakpoints (red arrow) in RARG gene, which are located at intron 3 and the 5′ untranslated region. The 3′ region of the RARG gene (from exon 1 or exon 4 to exon 9) was reversed and fused in-frame with the 5′ region of the CPSF6 gene (from exon 1 to exon 4) in both patients. (H) Electrophoresis of RT-PCR products from 2 patients showed 2 types of CPSF6-RARG fusion transcripts. (I) Partial nucleotide sequences surrounding the junctions of the 2 types of CPSF6-RARG fusion transcripts. The fusion transcript from patient 1 was a fusion between exon 4 of the CPSF6 gene with exon 4 of the RARG gene. The fusion transcript from patient 2 was a fusion between exon 4 of the CPSF6 gene with exon 1 of the RARG gene. (J) Schematic diagram of CPSF6, RARG, CPSF6-RARG-S, and CPSF6-RARG-L fusion proteins. CPSF6-RARG-L harbored a point mutation from 805G to C in patient 2, resulting in a change of glycine to arginine at 269. The breakpoint is indicated by a red line. UTR, untranslated region.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/131/16/10.1182_blood-2017-11-818716/5/m_blood818716f1.jpeg?Expires=1769103583&Signature=g8dLvx70s6-gJ-57Me7HYMB8Reqq-ZVQeST9xz4D8bwtKRwrVyzwvAC4FIanuFII0f3orAIbPrhl2wwJHKj~tEWm9Gt6lxmoFQEu4NBGELCPSbJLA8hIQDy-y8ljB-jRUFJMBdsqPY9lcgb~opmu1r2u1G3MEkk70DMRDDMJ55l2OFXHfY9KYlIRzHgGC28JoAjsmteDbrTZbCwP0IssGfNMGftx1Oa5jptw0cJqcSBEIzw~V8CdRgWkgF55GladyDWx4ssZTlrVmET4JiSsxxVl7cgur~Dk5pWboMdC21OchD9zZU8RB4LzuVm1b4sIAS6hddHifqIe1qsL0bgIgw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal