In this issue of Blood, Zhang et al1 have performed a genetic interrogation of neutrophilic myeloid neoplasms, revealing a distinct combination of genetic events and suggesting that the current use of clinicopathologic features to distinguish some individual entities may not be biologically relevant.

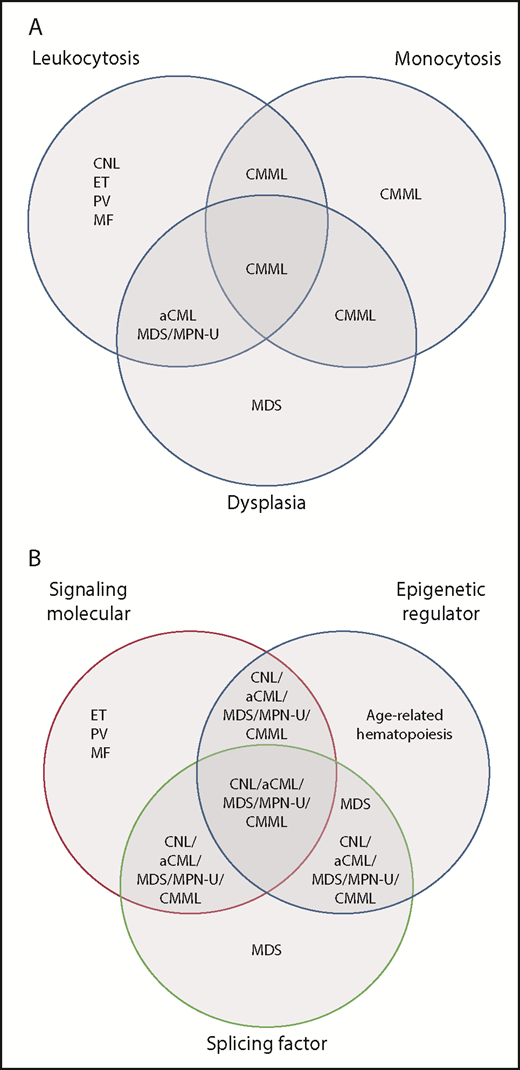

Distribution of myeloid neoplasms discussed in Zheng et al based on the current classification vs genetic pathway alterations revealed in the study. (A) Venn diagram of current (2016) WHO classification reflecting associations with leukocytosis, dysplasia, or monocytosis. Currently, monocytosis supersedes other features in determining a diagnosis of CMML, whereas granulocytic dysplasia (with left-shift) is the main feature distinguishing atypical CML (aCML), BCR-ABL1 negative from CNL. (B) A proposed Venn diagram showing the association of these disease subtypes with pathway mutations. There is significant overlap between entities that are considered distinct in the WHO classification, yet CNL and the MDS/MPN diseases remain largely separate from MDS and from the other “pure” MPN: essential thrombocythemia (ET), polycythemia vera (PV), and primary myelofibrosis (MF). MDS/MPN-U, MDS/MPN, unclassifiable. Panel B has been adapted from Figure 2D in the article by Zhang et al that begins on page 867.

Distribution of myeloid neoplasms discussed in Zheng et al based on the current classification vs genetic pathway alterations revealed in the study. (A) Venn diagram of current (2016) WHO classification reflecting associations with leukocytosis, dysplasia, or monocytosis. Currently, monocytosis supersedes other features in determining a diagnosis of CMML, whereas granulocytic dysplasia (with left-shift) is the main feature distinguishing atypical CML (aCML), BCR-ABL1 negative from CNL. (B) A proposed Venn diagram showing the association of these disease subtypes with pathway mutations. There is significant overlap between entities that are considered distinct in the WHO classification, yet CNL and the MDS/MPN diseases remain largely separate from MDS and from the other “pure” MPN: essential thrombocythemia (ET), polycythemia vera (PV), and primary myelofibrosis (MF). MDS/MPN-U, MDS/MPN, unclassifiable. Panel B has been adapted from Figure 2D in the article by Zhang et al that begins on page 867.

Myeloid neoplasms presenting predominantly with neutrophilia include the myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPN) chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) and chronic neutrophilic leukemia (CNL) as well as diseases considered within World Health Organization (WHO)-defined group of myelodysplastic/myeloproliferative neoplasms (MDS/MPN). Aside from the common feature of leukocytosis and presence or absence of BCR-ABL1 rearrangement (which defines CML), these diseases traditionally have been distinguished from one another by a host of clinicopathologic features, such as monocytosis, left-shifted granulocytes in the peripheral blood, and morphologic dysplasia of hematopoietic elements. These diseases can be challenging to treat, because the patient’s symptoms may be related to marked leukocytosis and splenomegaly, ineffective hematopoiesis with anemia and/or thrombocytopenia, or a combination of both. Moreover, determining the optimal treatment has been difficult: aside from CML, these rare diseases have been subjected to few clinical trials or have been included in clinical trials for myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS).

Zhang et al perform a detailed genetic analysis of a large number of CNL and MDS/MPN in order to determine their genomic landscape and relationship to other myeloid neoplasms, such as MDS. These neoplasms usually display mutations in 3 or 4 major pathways: ASXL1/ASXL2, TET2, or GATA2, and a signaling and/or splicing pathway mutation. This pattern of comutation had been recognized for chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML),2 but until now its prevalence among other MDS/MPN and CNL had not been clearly delineated. Importantly, this comutation pattern is uncommon in age-related hematopoiesis, MDS, and the JAK2/MPL/CALR-associated MPN. It is also rare in another MDS/MPN, juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia (JMML), which typically bears only RAS pathway mutations. These data raise the question as to the clinical relevance of separating neutrophilic myeloid neoplasms into subtypes distinguished by their morphology (see figure). Once CML, JMML, and the JAK2/MPL/CALR-associated MPN are excluded, these diseases appear to have common genetic features and may be best considered together in terms of prognostic modeling, optimal clinical approach, and inclusion in clinical trials.

What does determine biologic heterogeneity within this disease group? Not surprisingly, the authors find complex mutation associations, including comutations of genes in the same pathway. Certain mutation patterns are associated with clinicopathologic parameters, such as monocyte percentage, degree of leukocytosis, and degree of dysplasia. In addition, certain mutation patterns are overrepresented in particular disease subtypes, such as comutation of SRSF2 and TET2 in CMML, as has been shown in prior studies.2,3 However, the mutation patterns do not clearly segregate with the specific disease types recognized by the WHO classification. Gene expression profiling identifies 3 major clusters with variable representations of mutation frequencies and also does not segregate specific disease subtypes. Presumably, the varied clinical presentations among these diseases are influenced by the specific portfolio of mutations and their interactions, variant allele frequencies and mutational hierarchies of individual genes, and epigenetic factors influencing gene expression. The pattern of mutation hierarchy suggests sequential linear mutation acquisition, which differs from the more complex pattern of mutation acquisition in acute myeloid leukemia. The predicted order of mutation acquisition is heterogeneous, a factor that may also influence the clinical disease presentation, as has also been shown for other myeloid neoplasms such as polycythemia vera.4

This study also challenges the important tenet in the WHO classification that in MDS/MPN, the dysplastic and proliferative features must be present at the time of the initial diagnosis, with the exception of MDS/MPN with ring sideroblasts and thrombocytosis, in which the JAK2 mutation driving the thrombocytosis is acquired after the SF3B1 mutation driving the anemia and ring sideroblasts.5 Patients with other MDS/MPN may also present in earlier phases in which the full disease phenotype is not yet realized: should these diseases be arbitrarily classified differently from patients who present with fully evolved MDS/MPN? Indeed, a recent publication has proposed broadening the category of CMML to encompass variants in which monocytosis develops after a prior diagnosis of a myeloid neoplasm (currently excluded from this category) or patients presenting with monocyte counts below the current threshold.6 The current study supports this notion, given the mutational ontogeny of CMML and its overlap with other related myeloid neoplasms.

Do the results of this study imply that morphology is no longer relevant in the diagnostic approach to neutrophilic myeloid neoplasms? In fact, the authors do find significant associations of dysplasia with certain mutations (SRSF2 and TET2) and also correlate disease subtypes with clinical parameters such as red blood cell transfusion dependence. Another study found that circulating left-shifted granulocytic precursors and bone marrow blast percentages (but not dysgranulopoiesis) predicted inferior outcome in a group of MDS/MPN patients.7 The data from the Zhang et al study, together with prior work, suggest that parameters such as blood counts and morphologic findings are optimally used in combination with the mutational data to help predict the disease course.

Accurate disease classification is critical not only to determine the prognosis of individual patients but also to establish effective treatment paradigms. All effective disease classifications are built upon historical precedent; this precedent ensures consistency over time, but also creates an inertia that may impede the integration of new information. The rapid incorporation of molecular sequencing data into diagnostic hematopathology requires us to reexamine current concepts of disease categorization. The study by Zhang et al challenges current boundaries that separate CNL (currently classified as a “pure” MPN) from closely related MDS/MPN diseases and questions the relevance of using arbitrary morphologic features, such as monocyte counts or granulocytic dysplasia, to define distinct disease categories within MDS/MPN. On the other hand, they suggest that the MDS/MPN disease group is unique in its cascade of genetic events involving multiple pathways. Future classifications of myeloid neoplasms should take into account the genetic ontogeny in defining the borders of both large disease groupings (MDS, MPN, and MDS/MPN) and specific diseases within these broad categories.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author reports receiving consulting income from Promedior, Inc.