Key Points

Human pluripotent stem cells provide a novel platform to produce engineered off-the-shelf NK cells with efficient antitumor activity.

Human iPSC-NK cells with high-affinity noncleavable CD16a enable antibodies to more efficiently target NK cells to diverse tumor types.

Abstract

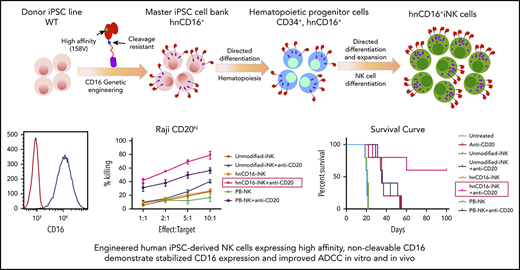

Antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) is a key effector mechanism of natural killer (NK) cells that is mediated by therapeutic monoclonal antibodies (mAbs). This process is facilitated by the Fc receptor CD16a on human NK cells. CD16a appears to be the only activating receptor on NK cells that is cleaved by the metalloprotease a disintegrin and metalloproteinase-17 upon stimulation. We previously demonstrated that a point mutation of CD16a prevents this activation-induced surface cleavage. This noncleavable CD16a variant is now further modified to include the high-affinity noncleavable variant of CD16a (hnCD16) and was engineered into human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) to create a renewable source for human induced pluripotent stem cell–derived NK (hnCD16-iNK) cells. Compared with unmodified iNK cells and peripheral blood–derived NK (PB-NK) cells, hnCD16-iNK cells proved to be highly resistant to activation-induced cleavage of CD16a. We found that hnCD16-iNK cells were functionally mature and exhibited enhanced ADCC against multiple tumor targets. In vivo xenograft studies using a human B-cell lymphoma demonstrated that treatment with hnCD16-iNK cells and anti-CD20 mAb led to significantly improved regression of B-cell lymphoma compared with treatment utilizing anti-CD20 mAb with PB-NK cells or unmodified iNK cells. hnCD16-iNK cells, combined with anti-HER2 mAb, also mediated improved survival in an ovarian cancer xenograft model. Together, these findings show that hnCD16-iNK cells combined with mAbs are highly effective against hematologic malignancies and solid tumors that are typically resistant to NK cell–mediated killing, demonstrating the feasibility of producing a standardized off-the-shelf engineered NK cell therapy with improved ADCC properties to treat malignancies that are otherwise refractory.

Introduction

Cell-based anticancer immunotherapies have experienced great advances in the past few years.1 Although chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)–expressing T cells have garnered the most attention, clinical trials using natural killer (NK) cells have demonstrated that they are safe and effective.2-5 In recent clinical trials, NK cells have been shown to possess potent anti–acute myeloid leukemia effects without eliciting serious adverse effects, such as graft-versus-host disease, neurotoxicity, and cytokine release syndrome.4,6,7 However, the adoptive transfer of NK cells to patients with B-cell lymphoma, ovarian carcinoma, or renal cell carcinoma has demonstrated low efficacy and has lacked specific tumor-targeting receptors8-10 .

NK cell–based clinical trials have used a variety of cell sources, including peripheral blood–derived NK (PB-NK) cells, umbilical cord blood–isolated NK (UCB-NK) cells, umbilical cord blood CD34+ cell–derived NK cells, and the NK cell line NK-92.7,11-14 Although these trials have demonstrated clinical safety, each cell source is confined by limitations.11,12,15 The NK cell yields and subsets from PB-NK cells and UCB-NK cells are extremely donor dependent and are not derived from a single renewable source, making product standardization and multiple-dosing strategies difficult.16,17 Additionally, genetic modification of primary NK cells is challenging and highly variable, making it difficult to develop consistent and reproducible engineered NK cell therapies.18 Lastly, although NK-92 cells are from a single source, they lack many conventional NK cell markers and, as a transformed cell, must be mitotically inactivated before infusion to prevent uncontrolled proliferation.13 This eliminates the ability of NK-92 cell treatment to expand upon infusion, a critical factor for NK cell antitumor activity.2,4,7,19 In contrast, human induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)–derived NK (iNK) cells can be produced in a homogenous and clinically scalable manner, are capable of being genetically edited at the iPSC stage, and have demonstrated in vivo proliferative capacity.20-23 Therefore, iNK cells are an important source of standardized off-the-shelf NK cell therapy to treat refractory malignancies.24

NK cell–mediated antitumor activity is regulated through a repertoire of activating and inhibitory cell surface receptors, including natural cytotoxicity receptors, killer immunoglobulin receptors, and immunoglobulin G (IgG) Fc receptor FcγRIIIa (CD16a).4,5,25 CD16a binds the Fc portion of IgG when attached to a target cell to mediate antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC), a key effector and tumor antigen-targeting mechanism of NK cells.26 The binding affinity of CD16a to IgG varies between its allelic variants. Specifically, CD16a with valine at position 158 (158V) has a higher affinity for IgG than does CD16a with phenylalanine at the same position.27,28 In addition to the clinical observation that NK cells enhance the efficacy of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies (mAbs),29 CD16a has been shown to play an important role in the clinical setting, because patients with high-affinity CD16a with 158V have had greater objective responses and progression-free survival when treated with cetuximab, trastuzumab, or rituximab.30-32 Notably, the CD16a molecule is cleaved from the surface of activated NK cells by a disintegrin and metalloproteinase-17 (ADAM17), which is constitutively expressed on the surface of NK cells,33-36 leading to NK cell dysfunction and reduced ADCC capacity.35 Our group previously identified the ADAM17 cleavage site of CD16 and created a high-affinity noncleavable version of CD16a (hnCD16) by mutating the cleavage site in the 158V variant.33

We hypothesized that engineering iNK cells with hnCD16 would overcome the challenges faced with NK cell therapies. Specifically, we demonstrate that iNK cells uniformly expressing hnCD16 (hnCD16-iNK cells) exhibit potent ADCC against hematological malignancies and solid tumors. Notably, a multidose regimen of hnCD16-iNK cells derived from an engineered clonal human iPSC line administered with anti-CD20 mAb treatment mediated potent activity and improved long-term survival in a mouse xenograft lymphoma model. Therefore, standardized off-the-shelf hnCD16-iNK cells with enhanced ADCC effector function, in combination with readily available anti-tumor mAbs, provide a novel clinical strategy to treat cancer.

Methods

Derivation and expansion of NK cells from hiPSCs

The derivation of NK cells from human iPSCs has been described previously.20,37 iNK cells were expanded using irradiated K562–IL21–4-1BBL cells (details can be found in supplemental Methods, available on the Blood Web site).

Cytotoxicity assays

A CellEvent Caspase-3/7 Green Flow Cytometry Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific; C10427) was used to quantify NK cell cytotoxicity after 4 hours of incubation with target cells. Real-time long-term cytotoxicity was monitored and quantified using an IncuCyte Caspase-3/7 Green Apoptosis Assay (Essen Bioscience; 4440). Details can be found in supplemental Methods.

CD107a expression and IFN-γ staining

CD107a expression was assessed and interferon-γ (IFN-γ) staining was performed as previously described.23 NK cells were cocultured with tumor targets at a 1:1 effector-to-target ratio. Details about the staining procedure are available in supplemental Methods.

Mouse models

NOD/SCID/γc−/− (NSG) mice (The Jackson Laboratory; n = 5 per group) were used for in vivo experiments. Mice were sublethally irradiated (225 cGy) 1 day prior to tumor engraftment. Mice were given 1 × 105 to 2.5 × 105 Luc-expressing tumor cells IV or via intraperitoneal injection. For the intraperitoneal injection tumor models, NK cells (107 cells per mouse) were injected intraperitoneally 4 days after tumor transplant. One day prior to NK cell injection, mice were assayed for tumor burden using bioluminescent imaging (BLI) and then placed into equivalent BLI-expressing groups. For the IV models, NK cells (107 cells per mouse) were injected IV 1 day after tumor cell infusion. NK cells were supported by the injection of interleukin-2 (IL-2) and/or IL-15, as reported previously.22 Tumor burden was determined by BLI using a Xenogen IVIS Imaging system. Mice were euthanized when they lost the ability to ambulate. All mice were housed, treated, and handled in accordance with the guidelines set forth by the University of California, San Diego Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and the National Institutes of Health’s Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Flow cytometry

All antibodies used are listed in supplemental Methods. Flow cytometry was performed on a BD FACSCalibur, a BD LSR II, or a NovoCyte 3000, and data were analyzed using FlowJo or NovoExpress software.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). In vitro data are from 3 independent experiments. Differences between groups were evaluated using 1-way analysis of variance. For the quantification of in vivo image, data are presented as the mean ± SEM, and differences between groups were analyzed using a 2-tailed Student t test. The survival curve was analyzed using the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism. All tests were considered significant at P < .05.

Results

hnCD16-iPSC–derived NK cells are phenotypically mature with stable expression of CD16a

To maintain high levels of stable CD16a expression on mature NK cells, we engineered human iPSCs with a non-ADAM17 cleavable version of the high-affinity CD16a 158V variant (supplemental Figure 1A-B).33 From the transduced hnCD16 pool, clonal iPSC lines were generated and screened to ensure a homogenous population of starting material (supplemental Figure 1C).38 The selected hnCD16-engineered iPSC clonal cell line stably expressed homogenous levels of hnCD16 (>99% CD16+; supplemental Figure 1D). Overexpression of hnCD16 had no significant effect on the morphology or growth rate of hnCD16-engineered iPSCs, which maintained homogenous expression of pluripotency master regulators NANOG and OCT4, as determined by flow cytometry (supplemental Figure 1E), as well as hiPSC surface markers (SSEA4, TRA-1-81, and CD30; supplemental Figure 1F). Moreover, integration site analysis showed that the hnCD16-iPSC clonal line that we selected has 3 copies of hnCD16 inserted. The hnCD16 transgene was inserted into intron regions or an intergenic region that would not lead to any changes in NK cell growth or activity (supplemental Table 1).

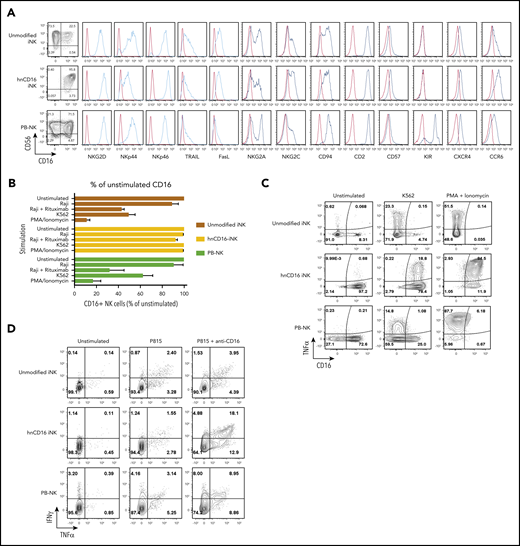

We then generated NK cells from hnCD16-engineered iPSCs using an in vitro differentiation method previously reported by our group (supplemental Figure 1B).20,39 Similar to PB-NK cells, unmodified iNK cells and hnCD16-iNK cells consist of a homogeneous population of CD56+ NK cells that also coexpress typical NK cell surface antigens: NKp44, NKp46, NKG2D, TRAIL, and Fas ligand (Figure 1A). They also expressed NK cell maturation markers (eg, CD94, CD2, NKG2C, and CD57) and homing receptors (eg, CXCR4 and CCR6) (Figure 1A). Expression of CD62L, another receptor that can be cleaved by ADAM17,40,41 was very low in iNK cells compared with PB-NK cells (supplemental Figure 2A). Additional characterization studies demonstrate that iNK cells have a longer telomere length than do PB-NK cells (supplemental Figure 1F).

hnCD16-iPSC–derived NK cells are functionally mature and do not downregulate CD16 expression upon activation. (A) Unmodified iNK cells, hnCD16-iNK cells, and adult PB-NK cells were stained and analyzed by flow cytometry for CD56 and CD16 and the indicated NK cell surface receptors. In each panel, red line: isotype control; blue line: stained sample. Data were repeated independently in 3 separate experiments. (B) hnCD16-iNK cells, unmodified iNK cells, or PB-NK cells were stimulated as indicated for 4 hours, and CD16 expression was determined by flow cytometry (n = 4-6 per group). (C) Representative flow cytometric analysis of CD16 and TNF-α expression on unmodified iNK cells, hnCD16-iNK cells, and PB-NK cells that were left unstimulated or stimulated with K562 cells or PMA/ionomycin. (D) Representative flow cytometric analysis of intracellular TNF-α and IFN-γ production after a 4-hour incubation with culture media only (unstimulated), with P815 cells, or with P815 cells + anti-CD16 antibody. Data in panels C-D were repeated in 3 separate experiments.

hnCD16-iPSC–derived NK cells are functionally mature and do not downregulate CD16 expression upon activation. (A) Unmodified iNK cells, hnCD16-iNK cells, and adult PB-NK cells were stained and analyzed by flow cytometry for CD56 and CD16 and the indicated NK cell surface receptors. In each panel, red line: isotype control; blue line: stained sample. Data were repeated independently in 3 separate experiments. (B) hnCD16-iNK cells, unmodified iNK cells, or PB-NK cells were stimulated as indicated for 4 hours, and CD16 expression was determined by flow cytometry (n = 4-6 per group). (C) Representative flow cytometric analysis of CD16 and TNF-α expression on unmodified iNK cells, hnCD16-iNK cells, and PB-NK cells that were left unstimulated or stimulated with K562 cells or PMA/ionomycin. (D) Representative flow cytometric analysis of intracellular TNF-α and IFN-γ production after a 4-hour incubation with culture media only (unstimulated), with P815 cells, or with P815 cells + anti-CD16 antibody. Data in panels C-D were repeated in 3 separate experiments.

hnCD16-iNK cells were expanded using artificial antigen presenting cells (aAPCs), as previously reported.22,42 Under these culture and expansion conditions, nearly all hnCD16-iNK cells expressed CD16 (99% CD16+; Figure 1A), whereas the endogenous expression of CD16 on unmodified iNK cells and PB-NK cells under the same culture conditions is typically between 20% and 60% (Figure 1A). These results are consistent with previous studies demonstrating that endogenous CD16 is cleaved from the surface of NK cells by ADAM17 upon activation by stimuli, such as cytokines and target cells.33,36 To assess the stability of CD16 expression by hnCD16-iNK cells, we activated unmodified iNK cells, hnCD16-iNK cells, and PB-NK cells with different stimuli, including PMA/ionomycin, K562 cells, the CD20+ Burkitt lymphoma cell line Raji, and Raji cells in the presence of the anti-CD20 mAb rituximab (Figure 1B-C). For example, after stimulation with K562 target cells or PMA/ionomycin, PB-NK cells and unmodified iNK cells lost the majority of their CD16 expression, whereas the majority of hnCD16-iNK cells maintained high levels of CD16 expression (Figure 1C). It is also important to note that unmodified iNK cells are homozygous for low-affinity CD16 (158F), whereas PB-NK cells are heterozygous (supplemental Figure 1G), indicating that low-affinity and high-affinity CD16 can be downregulated on activated NK cells. Importantly, stable CD16 surface expression on hnCD16-iNK cells led to enhanced cytokine production when CD16 was activated directly (Figure 1D). In support of this, the production of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and IFN-γ in response to CD16a stimulation was directly correlated with the level of surface CD16 expression (Figure 1A,C-D).

hnCD16-iNK cells have superior in vitro ADCC against multiple tumor types

Because CD16 is a key activating receptor on NK cells that mediates ADCC, we examined the ability of hnCD16-iNK cells to mediate ADCC against multiple cancer cell lines, including Raji cells, A549 (lung adenocarcinoma) cells, SKOV-3 (ovarian adenocarcinoma) cells, and Cal27 (squamous cell carcinoma) cells. The antibodies that recognize antigens on these tumor cell lines (CD20 on Raji; EGFR on A549, SKOV-3, and Cal27; HER2 on SKOV-3) are all routinely used clinically with proven efficacy.43-45

We first used degranulation (indicated by the cell surface expression of CD107a) and IFN-γ/TNF-α expression as parameters for NK cell activity to evaluate antibody-dependent effector function against different cancer cell populations.21,23 When Raji, SKOV-3, and Cal27 cells were cocultured with unmodified iNK cells or with hnCD16-iNK cells alone, minimal expression of CD107a, IFN-γ (Figure 2A), and TNF-α (supplemental Figure 2B) was detected. However, when target cells were pretreated with their respective antibodies (anti-CD20: rituximab; anti-HER2: trastuzumab; and anti-EGFR: cetuximab), CD107a+ hnCD16-iNK cells were increased 3.9-, 8-, and 4.5-fold for Raji cells + rituximab, SKOV-3 cells + trastuzumab, and Cal27 cells + cetuximab, respectively (Figure 2A-B), and IFNγ+ hnCD16-iNK cells were increased 5.1-, 12-, and 6.5-fold (Figure 2A,C) for Raji cells + rituximab, SKOV-3 cells + trastuzumab, and Cal27 cells + cetuximab, respectively. Production of IFN-γ correlates closely with production of TNF-α in NK cells (supplemental Figure 2). In contrast, stimulation of unmodified iNK cells with target cells and antibodies did not mediate increased CD107a, IFN-γ, (Figure 2A-B) or TNF-α (supplemental Figure 2) expression, suggesting that hnCD16 improved the antibody-dependent cytokine response against these tumor cells. In addition, we systemically evaluated cytokine production by comparing TNF-α and IFN-γ production and CD107a surface expression of unmodified iNK cells, hnCD16-iNK cells, UCB-NK cells, and PB-NK cells upon stimulation with P815 cells (mouse lymphoblast-like mastocytoma cell line),46 P815 cells + anti-CD16 mAb, Raji cells, and Raji cells + anti-CD20 mAb. Similarly, hnCD16-iNK cells showed the greatest TNF-α and IFN-γ production and CD107a surface expression with P815 + anti-CD16 mAb or Raji + anti-CD20 mAb stimulation, suggesting the strongest antibody-mediated response against these tumor targets (Figure 2C).

hnCD16-iNK cells demonstrate improved in vitro ADCC against multiple tumor types. (A) hnCD16-iNK cells and unmodified iNK cells produce CD107α and IFN-γ in response to Raji cells with or without anti-CD20 antibody, in response to SKOV-3 cells with or without anti-HER2, and in response to Cal27 cells with or without anti-EGFR. hnCD16-iNK cells or unmodified iNK cells were left unstimulated or were stimulated with a 1:1 ratio of target cells with or without antibody and stained for CD107a and IFN-γ 4 hours later. (B) Quantification of CD107a (left panel) and IFN-γ (right panel) expression by cells in panel A. An increase in CD107a+ or IFNγ+ positive cells in the antibody group was normalized to the without-antibody group (fold increase: antibody/without antibody). Studies were repeated independently 3 times, and data are mean ± standard deviation. (C) Quantification of flow cytometric analysis of TNF-α and IFN-γ production and CD107a surface expression after a 4-hour incubation with culture media only (unstimulated) or with the indicated stimuli. Heat maps quantify the frequency of NK cells that are positive for IFN-γ, TNF-α, or CD107a and are scaled from 0% (black) to 30% (yellow), with background expression subtracted such that unstimulated = 0. (D) ADCC against Raji cells was analyzed using a caspase-3/7 green flow cytometry assay. Raji cells were incubated with NK cells, with or without anti-CD20 antibody, for 4 hours. (E) ADCC against Raji cells was analyzed over a 24-hour period using an IncuCyte real-time imaging system. Anti-CD20 was titrated from 0.001 μg/mL to 20 μg/mL. (F-G) Long-term (66-hour) ADCC assays using the IncuCyte real-time imaging system. ADCC against the lung cancer cell line A549 with and without anti-EGFR mAb (F) and against the ovarian cancer cell line SKOV-3 with and without anti-HER2 mAb (G). Data in panels F-G are presented as the normalized frequency of target cells remaining, where target cells without NK effectors = 100%. Data in panels D-G were repeated independently in 3 separate experiments. ***P < .001, 2-tailed Student t test.

hnCD16-iNK cells demonstrate improved in vitro ADCC against multiple tumor types. (A) hnCD16-iNK cells and unmodified iNK cells produce CD107α and IFN-γ in response to Raji cells with or without anti-CD20 antibody, in response to SKOV-3 cells with or without anti-HER2, and in response to Cal27 cells with or without anti-EGFR. hnCD16-iNK cells or unmodified iNK cells were left unstimulated or were stimulated with a 1:1 ratio of target cells with or without antibody and stained for CD107a and IFN-γ 4 hours later. (B) Quantification of CD107a (left panel) and IFN-γ (right panel) expression by cells in panel A. An increase in CD107a+ or IFNγ+ positive cells in the antibody group was normalized to the without-antibody group (fold increase: antibody/without antibody). Studies were repeated independently 3 times, and data are mean ± standard deviation. (C) Quantification of flow cytometric analysis of TNF-α and IFN-γ production and CD107a surface expression after a 4-hour incubation with culture media only (unstimulated) or with the indicated stimuli. Heat maps quantify the frequency of NK cells that are positive for IFN-γ, TNF-α, or CD107a and are scaled from 0% (black) to 30% (yellow), with background expression subtracted such that unstimulated = 0. (D) ADCC against Raji cells was analyzed using a caspase-3/7 green flow cytometry assay. Raji cells were incubated with NK cells, with or without anti-CD20 antibody, for 4 hours. (E) ADCC against Raji cells was analyzed over a 24-hour period using an IncuCyte real-time imaging system. Anti-CD20 was titrated from 0.001 μg/mL to 20 μg/mL. (F-G) Long-term (66-hour) ADCC assays using the IncuCyte real-time imaging system. ADCC against the lung cancer cell line A549 with and without anti-EGFR mAb (F) and against the ovarian cancer cell line SKOV-3 with and without anti-HER2 mAb (G). Data in panels F-G are presented as the normalized frequency of target cells remaining, where target cells without NK effectors = 100%. Data in panels D-G were repeated independently in 3 separate experiments. ***P < .001, 2-tailed Student t test.

We then assessed these different NK cell populations for ADCC. Similar to the results for NK cell degranulation and IFN-γ expression, unmodified iNK cells demonstrated relatively limited killing of Raji cells, even with the addition of an anti-CD20 mAb (Figure 2D). In contrast, the addition of an anti-CD20 mAb to hnCD16-iNK cells cocultured with Raji cells led to a marked increase in cell killing (Figure 2D). A prolonged time course analysis using various doses of anti-CD20 mAb further demonstrated the potent ADCC activity of hnCD16-iNK cells, even at antibody concentrations as low as 0.1 μg/mL, which may improve the efficacy of mAb treatment41 (Figure 2E). Studies comparing hnCD16-iNK cells with PB-NK cells using this longer (>60 hours) cytotoxicity assay against SKOV-3 cells (with or without trastuzumab; Figure 2F) and A549 cells (with or without cetuximab; Figure 2G) also demonstrated that hnCD16-iNK cells mediated improved ADCC compared with PB-NK cells. To further investigate the contribution of the noncleavable CD16 variant to the improved ADCC, we compared hnCD16-iNK cells and iNK cells engineered with natural (cleavable) high-affinity CD16 (WTCD16-iNK cells).33 hnCD16-iNK cells and WTCD16-iNK cells exhibit similar expression levels of CD16 (supplemental Figure 3A-B). In line with our previous findings (Figure 1C), CD16 expression in WTCD16-iNK cells was downregulated when cells were activated with PMA/ionomycin, Raji cells + anti-CD20 mAb rituximab, or Cal-27 cells + anti-EGFR mAb cetuximab for 4 hours (supplemental Figure 3C). In contrast, hnCD16-iNK cells maintained uniformly high levels of CD16 expression (supplemental Figure 3C). Notably, hnCD16-iNK cells mediated ADCC better than did WTCD16-iNK cells (supplemental Figure 3D-E). These results demonstrate that noncleavable CD16 contributes to the improved ADCC in hnCD16-iNK cells.

Next, we investigated downstream signaling mediated by CD16 activation. Upon cross-linking by anti-CD16 antibody, all 3 cell populations mediate efficient downstream signaling activation, as shown by phospho-flow staining of CD3ζ, ZAP70, and SLP76, which are downstream targets of CD16 activation47 (supplemental Figure 4A). This was supported by immunoblot analysis that also demonstrates ERK phosphorylation (supplemental Figure 4B). Furthermore, we studied the detachment of NK cells after killing target cells using an IncuCyte real-time imaging system. Again, hnCD16-iNK cells show significantly better killing against Cal27 cells with the addition of cetuximab (supplemental Figure 5A-D). Notably, the number of target cells killed per single hnCD16-iNK cell was significantly higher than that seen with unmodified iNK cells and PB-NK cells (supplemental Figure 5D). The percentage of NK cells detached from targets and the detachment time after killing targets are also similar among hnCD16-iNK cells, unmodified iNK cells, and PB-NK cells (supplemental Figure 5E-F), demonstrating that hnCD16 does not inhibit the detachment of NK cells from targets (see also supplemental Videos 1-3).

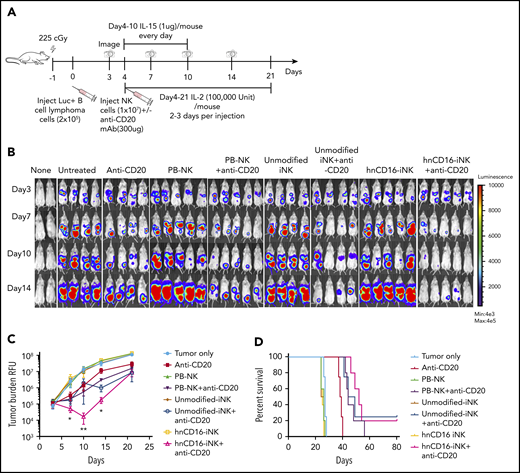

A single dose of hnCD16-iNK cells effectively mediates in vivo ADCC against human B-cell lymphoma

To evaluate the in vivo ADCC activity of the hnCD16-iNK cells, we used a Raji-Luc xenograft mouse model (Figure 3A) to compare 8 treatment groups: tumor alone (untreated), anti-CD20 mAb alone, and PB-NK cells, unmodified iNK cells, or hnCD16-iNK cells alone or in combination with anti-CD20 mAb (Figure 3B). As previously seen with NK cells in this in vivo xenograft model,48 treatment with PB-NK cells, unmodified iNK cells, or hnCD16-iNK cells alone did not inhibit tumor growth, and mice in these 3 groups show tumor burden similar to that seen in the untreated tumor group at all time points (Figure 3B-C). In comparison with anti-CD20 mAb treatment alone, combination treatment with hnCD16-iNK and anti-CD20 mAb was the only one to result in a significant decrease in tumor burden (at day 10 posttreatment, **P < .001) (Figure 3C). Specifically, a single dose of anti-CD20 mAb improved median survival from 27 to 38 days, whereas the combination of PB-NK cells or unmodified iNK cells with anti-CD20 mAb further inhibited tumor progression and resulted in significantly better median survival (43 and 44 days, respectively; Figure 3D). Combination treatment with hnCD16-iNK cells and anti-CD20 mAb led to an additional increase in median survival to 52 days (Figure 3D; anti-CD20 vs hnCD16-iNK cells + anti-CD20; P = .0027). However, survival in the hnCD16-iNK cells + anti-CD20 mAb group was not statistically better than in the PB-NK cells + anti-CD20 mAb group or the unmodified iNK cells + anti-CD20 mAb group (Figure 3D). Therefore, in this single-dose model, any of the 3 NK cell populations combined with anti-CD20 treatment mediated effective antitumor activity in vivo (Figure 3D).

A single dose of hnCD16-iNK cells effectively mediates in vivo ADCC against human B-cell lymphoma. (A) Schema of single-dose NK infusion in vivo study. NSG mice were inoculated intraperitoneally with 2 × 105 Luc-expressing Raji cells, and tumor engraftment was assessed by IVIS imaging 3 days later for a baseline pretreatment reading. On day 4 after transplant, mice were left untreated or were treated with 1 × 107 PB-NK cells, unmodified iNK cells, or hnCD16-iNK cells, alone or in combination with 300 μg of anti-CD20 antibody. Mice were treated with IL-15 for the first week and with IL-2 for 3 weeks, and IVIS imaging was performed to track tumor progression. (B) Tumor burden was determined by BLI. (C) Quantification of IVIS imaging time course. Data are mean ± SEM for the mice in panel B. Data were not significant for anti-CD20 alone vs unmodified iNK cells + anti-CD20 or for PB-NK cells + anti-CD20 at all time points. (D) Kaplan-Meier curve demonstrating survival of the experimental groups. The median survival for the untreated group and the groups treated with anti-CD20, PB-NK cells + anti-CD20, unmodified iNK cells + anti-CD20, and hnCD16-iNK cells + anti-CD20 was 27, 38, 43, 44, and 52 days, respectively. Anti-CD20 vs PB-NK+anti-CD20, P = .0047; anti-CD20 vs unmodified-iNK+anti-CD20, P = .0067; anti-CD20 vs hnCD16-iNK+anti-CD20, P = .0027; PB-NK+anti-CD20 vs hnCD16-iNK+anti-CD20, P = .1098; unmodified-iNK+anti-CD20 vs hnCD16-iNK+anti-CD20, P = .3127; 2-tailed log-rank test. *P < .05, **P < .01, 2-tailed Student t test, anti-CD20 alone vs hnCD16-iNK cells + anti-CD20.

A single dose of hnCD16-iNK cells effectively mediates in vivo ADCC against human B-cell lymphoma. (A) Schema of single-dose NK infusion in vivo study. NSG mice were inoculated intraperitoneally with 2 × 105 Luc-expressing Raji cells, and tumor engraftment was assessed by IVIS imaging 3 days later for a baseline pretreatment reading. On day 4 after transplant, mice were left untreated or were treated with 1 × 107 PB-NK cells, unmodified iNK cells, or hnCD16-iNK cells, alone or in combination with 300 μg of anti-CD20 antibody. Mice were treated with IL-15 for the first week and with IL-2 for 3 weeks, and IVIS imaging was performed to track tumor progression. (B) Tumor burden was determined by BLI. (C) Quantification of IVIS imaging time course. Data are mean ± SEM for the mice in panel B. Data were not significant for anti-CD20 alone vs unmodified iNK cells + anti-CD20 or for PB-NK cells + anti-CD20 at all time points. (D) Kaplan-Meier curve demonstrating survival of the experimental groups. The median survival for the untreated group and the groups treated with anti-CD20, PB-NK cells + anti-CD20, unmodified iNK cells + anti-CD20, and hnCD16-iNK cells + anti-CD20 was 27, 38, 43, 44, and 52 days, respectively. Anti-CD20 vs PB-NK+anti-CD20, P = .0047; anti-CD20 vs unmodified-iNK+anti-CD20, P = .0067; anti-CD20 vs hnCD16-iNK+anti-CD20, P = .0027; PB-NK+anti-CD20 vs hnCD16-iNK+anti-CD20, P = .1098; unmodified-iNK+anti-CD20 vs hnCD16-iNK+anti-CD20, P = .3127; 2-tailed log-rank test. *P < .05, **P < .01, 2-tailed Student t test, anti-CD20 alone vs hnCD16-iNK cells + anti-CD20.

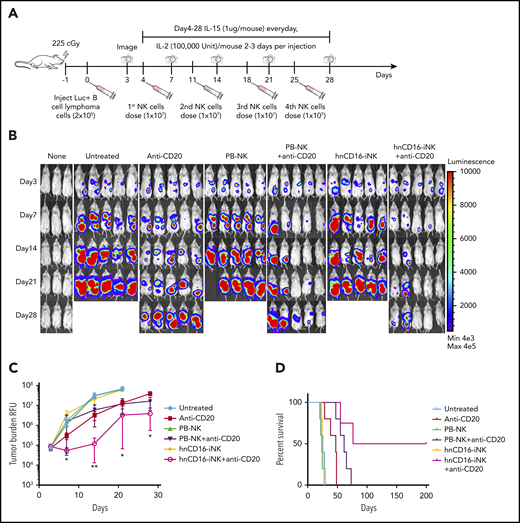

Multiple doses of hnCD16-iNK cells mediate improved survival in an in vivo human lymphoma xenograft model

In the single-dose study, we identified a decrease in tumor burden at day 10 (Figure 3C); however, relapse was observed in most of the treated mice, which may be due to human NK cells having a limited life span after adoptive transfer.2,22,23 We next examined whether multiple doses of NK cells + anti-CD20 mAb would further augment in vivo ADCC. We performed a 1-month dosing study consisting of 4 weekly doses of NK cells, with or without anti-CD20 mAb (Figure 4A). Because unmodified iNK cells and PB-NK cells, in combination with anti-CD20, show similar tumor suppression in the single-dose study, in this study we focused our comparison on hnCD16-iNK cells and PB-NK cells. Similar to the single-dose study, all of the mice in the untreated groups died between day 23 and day 26 (median survival, 25 days; Figure 4). Again, 4 weekly doses of PB-NK cells or hnCD16-iNK cells alone had no effect on tumor progression (Figure 4B). As expected, 4 weekly doses of anti-CD20 mAb alone induced tumor regression (Figure 4B-C) and prolonged the median survival to 47 days (Figure 4D). Notably, median survival was longer with multiple NK cell doses compared with the single-dose study (hnCD16-iNK cells + anti-CD20 mAb), demonstrating significant improvement in antitumor activity, with a mean survival of 76 days (Figure 4D; anti-CD20 vs hnCD16-iNK cells + anti-CD20; P = .0065).

Multiple doses of hnCD16-iNK cells effectively mediate improved ADCC in vivo against B-cell lymphoma. (A) Schema of multiple NK cell dosing study. NSG mice were inoculated intraperitoneally with 2 × 105 Luc-expressing Raji cells, and tumor engraftment was assessed by IVIS imaging 3 days later for a baseline pretreatment reading. On day 4 after transplant, mice were left untreated or were treated with 1 × 107 PB-NK cells or hnCD16-iNK cells, alone or in combination with 300 μg of rituximab weekly for 4 weeks. NK cells were supported by injection of IL-15 for the first week and by injection of IL-2 for 3 weeks. IVIS imaging was done weekly to monitor tumor progression. (B) Tumor burden was determined by BLI over the first 28 days. (C) Time course of IVIS imaging. Data are mean ± SEM for the mice in panel B. Anti-CD20 vs PB-NK+anti-CD20 not significant for all data points, 2-tailed Student t test. (D) Kaplan-Meier curve representing the percent survival of the experimental groups. The median survival for the untreated group and the groups treated with Anti-CD20, PB-NK+anti-CD20, and hnCD16-iNK+anti-CD20 are 25, 47, 61, and 76 days, respectively. Anti-CD20 vs PB-NK+anti-CD20, P = .0185; anti-CD20 vs hnCD16-iNK+anti-CD20, P = .0065; PB-NK+anti-CD20 vs hnCD16-iNK+anti-CD20, P = .0485; 2-tailed log-rank test. *P < .05, **P < .01, anti-CD20 vs hnCD16-iNK+anti-CD20, 2-tailed Student t test.

Multiple doses of hnCD16-iNK cells effectively mediate improved ADCC in vivo against B-cell lymphoma. (A) Schema of multiple NK cell dosing study. NSG mice were inoculated intraperitoneally with 2 × 105 Luc-expressing Raji cells, and tumor engraftment was assessed by IVIS imaging 3 days later for a baseline pretreatment reading. On day 4 after transplant, mice were left untreated or were treated with 1 × 107 PB-NK cells or hnCD16-iNK cells, alone or in combination with 300 μg of rituximab weekly for 4 weeks. NK cells were supported by injection of IL-15 for the first week and by injection of IL-2 for 3 weeks. IVIS imaging was done weekly to monitor tumor progression. (B) Tumor burden was determined by BLI over the first 28 days. (C) Time course of IVIS imaging. Data are mean ± SEM for the mice in panel B. Anti-CD20 vs PB-NK+anti-CD20 not significant for all data points, 2-tailed Student t test. (D) Kaplan-Meier curve representing the percent survival of the experimental groups. The median survival for the untreated group and the groups treated with Anti-CD20, PB-NK+anti-CD20, and hnCD16-iNK+anti-CD20 are 25, 47, 61, and 76 days, respectively. Anti-CD20 vs PB-NK+anti-CD20, P = .0185; anti-CD20 vs hnCD16-iNK+anti-CD20, P = .0065; PB-NK+anti-CD20 vs hnCD16-iNK+anti-CD20, P = .0485; 2-tailed log-rank test. *P < .05, **P < .01, anti-CD20 vs hnCD16-iNK+anti-CD20, 2-tailed Student t test.

Interestingly, of the 3 mice in the PB-NK cells + anti-CD20 mAb group that did not exhibit detectable tumor at day 14, all exhibited tumor relapse by day 28 (Figure 4B). However, only 1 of the 4 mice that had undetectable tumor at day 14 in the hnCD16-iNK cells + anti-CD20 mAb group experienced tumor relapse at day 28 (Figure 4B), and 2 mice maintained complete remission (>200 days), demonstrating a more durable antitumor response (Figure 4D). Furthermore, the survival rate of mice receiving multiple dosing of hnCD16-iNK cells + anti-CD20 mAb treatment was significantly better than for PB-NK cells + anti-CD20 mAb treatment (P = .0485; Figure 4D). These results support the strategy of multidosing of hnCD16-iNK cells to maximize ADCC in vivo to enable long-term survival and possible complete tumor elimination.

hnCD16-iNK cells effectively mediate ADCC in an in vivo human lymphoma systemic tumor model

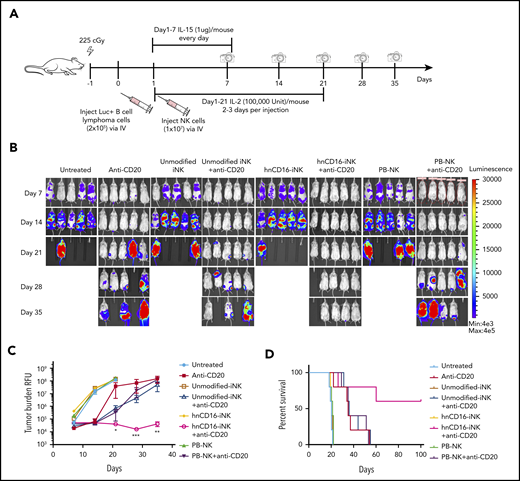

To evaluate the in vivo ADCC activity of hnCD16-iNK cells in a more clinically relevant model, we used an in vivo systemic tumor model in which Raji-Luc tumor cells and NK cells were dosed IV (Figure 5A). In this model, tumor distribution is disseminated, and disease progression is more aggressive than when tumor cells are delivered intraperitoneally. The median survival of mice in untreated groups was 17 days (Figure 5D). Consistent with previous studies, treatment with PB-NK cells, unmodified iNK cells, or hnCD16-iNK cells alone did not inhibit tumor growth (Figure 5B). A single dose of anti-CD20 mAb alone decreased tumor burden (Figure 5B-C) and improved the median survival from 17 to 35 days (Figure 5D; P = .021). Combination treatment using PB-NK cells or unmodified iNK cells + anti-CD20 mAb did not improve tumor control in comparison with anti-CD20 mAb treatment alone (Figure 5B-C). As with the intraperitoneal injection model, combination treatment with hnCD16-iNK cells + anti-CD20 mAb mediated improved antitumor activity with significantly better survival than anti-CD20 mAb alone (P = .0269), PB-NK cells + anti-CD20 mAb (P = .0342), or unmodified iNK cells + anti-CD20 mAb (P = .0350; Figure 5D). Notably, 3 mice in the hnCD16-iNK cells + anti-CD20 mAb group maintained complete remission at 100 days posttumor transplant, whereas no mice in other groups survived beyond 60 days (Figure 5D). These results further confirmed that hnCD16-iNK cells can effectively mediate ADCC and provide a more durable antitumor response against human lymphoma.

hnCD16-iNK cells effectively mediate ADCC in a human lymphoma systemic tumor model. (A) Flow scheme of IV NK cell infusion in vivo study. NSG mice were inoculated IV with 2 × 105 Luc-expressing Raji cells. On day 1 after transplant, mice were left untreated or were treated with 1 × 107 PB-NK cells, unmodified iNK cells, or hnCD16-iNK cells, alone or in combination with 300 μg of anti-CD20 antibody. NK cells were supported by injection of IL-15 for the first week and by injection of IL-2 for 3 weeks; IVIS imaging was performed weekly to track tumor progression. (B) Tumor burden was determined by BLI over the first 35 days. (C) IVIS imaging time course. Data are mean ± SEM for the mice in panel B. (D) Kaplan-Meier curve representing the percent survival of the experimental groups. The median survival was not reached in the hnCD16-iNK + anti-CD20 group. Anti-CD20 vs untreated, P = .0021; anti-CD20 vs hnCD16-iNK+anti-CD20, P = .0269; hnCD16-iNK+anti-CD20 vs PB-NK+anti-CD20, P = .0342; hnCD16-iNK+anti-CD20 vs umnodified-iNK+anti-CD20, P = .0350; 2-tailed log-rank test. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001, hnCD16-iNK+anti-CD20 vs umnodified-iNK+anti-CD20, 2-tailed Student t test.

hnCD16-iNK cells effectively mediate ADCC in a human lymphoma systemic tumor model. (A) Flow scheme of IV NK cell infusion in vivo study. NSG mice were inoculated IV with 2 × 105 Luc-expressing Raji cells. On day 1 after transplant, mice were left untreated or were treated with 1 × 107 PB-NK cells, unmodified iNK cells, or hnCD16-iNK cells, alone or in combination with 300 μg of anti-CD20 antibody. NK cells were supported by injection of IL-15 for the first week and by injection of IL-2 for 3 weeks; IVIS imaging was performed weekly to track tumor progression. (B) Tumor burden was determined by BLI over the first 35 days. (C) IVIS imaging time course. Data are mean ± SEM for the mice in panel B. (D) Kaplan-Meier curve representing the percent survival of the experimental groups. The median survival was not reached in the hnCD16-iNK + anti-CD20 group. Anti-CD20 vs untreated, P = .0021; anti-CD20 vs hnCD16-iNK+anti-CD20, P = .0269; hnCD16-iNK+anti-CD20 vs PB-NK+anti-CD20, P = .0342; hnCD16-iNK+anti-CD20 vs umnodified-iNK+anti-CD20, P = .0350; 2-tailed log-rank test. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001, hnCD16-iNK+anti-CD20 vs umnodified-iNK+anti-CD20, 2-tailed Student t test.

We then investigated the in vivo persistence and homing of NK cells in a separate group of tumor-bearing mice by examining blood, bone marrow, spleen, kidney, liver, and heart for the presence of NK cells over 21 days postinjection. On day 7, human NK cells were detected in all of the organs examined (supplemental Figure 6A-B), although some of the cells seen in organs may be from blood perfusing those organs, because this cannot be distinguished when organs are processed for analysis. The infused NK cells reached a peak at day 7 and persisted for up to 21 days (supplemental Figure 6C). PD-1 expression was not detected on iNK cells before or after adoptive transfer (supplemental Figure 6D). Unmodified iNK cells, hnCD16-iNK cells, and PB-NK cells show similar persistence, and homing was confirmed by immunohistochemistry staining in organs (supplemental Figure 6E), indicating that the improved antitumor effect mediated by hnCD16-iNK cells was due to increased ADCC rather than differences in persistence or homing.

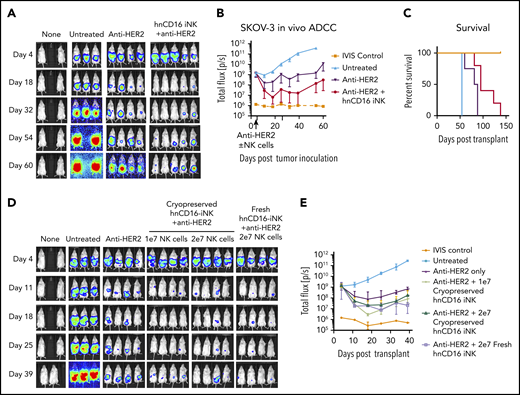

hnCD16-iNK cells + anti-HER2 mAb effectively target ovarian cancer cells in vivo

To test whether hnCD16-iNK cells can also elicit antitumor effects against solid tumors in vivo, we used a mouse xenograft model and SKOV-3 ovarian carcinoma cells (Figure 6). Combination treatment with hnCD16-iNK cells + anti-HER2 mAb led to significantly lower tumor burden at all time points between day 18 and day 60 (Figure 6A-B). Moreover, hnCD16-iNK cells + anti-HER2 mAb significantly improved survival (P = .0040; Figure 6C). These results demonstrate that hnCD16-iNK cells can also mediate an antitumor response in an in vivo ovarian cancer model when combined with anti-HER2.

hnCD16-iNK cells mediate improved ADCC in vivo against ovarian cancer. NSG mice were inoculated intraperitoneally with 1 × 105 Luc-expressing SKOV-3 cells, and tumor engraftment was assessed by IVIS imaging 4 days later. On day 5 after tumor transplant, mice were left untreated or were treated with 100 μg of anti-HER2 alone or in combination with 5 × 106 hnCD16 iNK cells. NK cells were supported by twice weekly injections of IL-2, and IVIS imaging was done weekly to track tumor load. (A) IVIS imaging. (B) Quantification of geometric mean ± standard deviation for the mice in panel A. (C) Kaplan-Meier curve representing the percent survival of the experimental groups. Untreated vs anti-HER2, P = .0140; anti-HER2 vs anti-HER2 + hnCD16 iNK+, P = .004; 2-tailed log-rank test. (D) Mice injected with Luc-expressing SKOV-3 cells were treated with 1 × 107 (1e7) or 2 × 107 (2e7) cryopreserved hnCD16-iNK cells or with 2 × 107 fresh hnCD16-iNK cells + anti-HER2 antibody. (D) IVIS imaging. (E) Quantification of the geometric mean ± standard deviation for the mice in panel D.

hnCD16-iNK cells mediate improved ADCC in vivo against ovarian cancer. NSG mice were inoculated intraperitoneally with 1 × 105 Luc-expressing SKOV-3 cells, and tumor engraftment was assessed by IVIS imaging 4 days later. On day 5 after tumor transplant, mice were left untreated or were treated with 100 μg of anti-HER2 alone or in combination with 5 × 106 hnCD16 iNK cells. NK cells were supported by twice weekly injections of IL-2, and IVIS imaging was done weekly to track tumor load. (A) IVIS imaging. (B) Quantification of geometric mean ± standard deviation for the mice in panel A. (C) Kaplan-Meier curve representing the percent survival of the experimental groups. Untreated vs anti-HER2, P = .0140; anti-HER2 vs anti-HER2 + hnCD16 iNK+, P = .004; 2-tailed log-rank test. (D) Mice injected with Luc-expressing SKOV-3 cells were treated with 1 × 107 (1e7) or 2 × 107 (2e7) cryopreserved hnCD16-iNK cells or with 2 × 107 fresh hnCD16-iNK cells + anti-HER2 antibody. (D) IVIS imaging. (E) Quantification of the geometric mean ± standard deviation for the mice in panel D.

A key challenge in developing off-the-shelf adoptive cell therapies is getting cells from the manufacturing site to the patient without compromising safety or efficacy.49 Cryopreservation provides the best opportunity to deliver multiple doses, which can augment the antitumor effect while maintaining the high levels of killing seen in previous studies,50 provided that the cell viability and function are not negatively impacted upon thawing. To test the anticancer activity of hnCD16-iNK cells after cryopreservation, we compared cryopreserved cells and fresh cells in the SKOV-3 cell ovarian tumor xenograft model (Figure 6D). Notably, one-time dosing of cryopreserved hnCD16-iNK cells demonstrated similar antitumor activity as fresh hnCD16-iNK cells (Figure 6D-E).

Discussion

The ability to improve targeting and specificity are key requirements to better enable NK cell–mediated killing of solid tumors and lymphoid malignancies that are typically more resistant to this therapeutic modality. Here, we demonstrate the ability to use human pluripotent stem cells as a platform to produce engineered NK cells that can be effectively combined with therapeutic mAbs to successfully target and kill typically NK cell–resistant tumors. Specifically, creation and use of a novel CD16 molecule that contains the 158V high-affinity variant, combined with an S197P mutation that confers resistance to ADAM17-mediated cleavage, allows us to produce NK cells with improved ADCC activity in vitro and in vivo. In this model, CD16 engagement and signaling provide an important strategy to make NK cells antigen specific. These engineered iPSC-derived NK cells can now be produced at a clinical scale,20,24,51 as well as cryopreserved (Figure 6), to enable upcoming clinical trials of hnCD16-iNK cells.

NK cell–based adoptive immunotherapy provides a promising therapeutic option for allogeneic cancer therapy, with many clinical trials underway for a variety of hematological malignancies and solid tumors.3-5 Most of these clinical trials use allogeneic PB-NK cells, and significant remissions have been observed when they are used to treat acute myeloid leukemia.2,19 However, as noted, the efficacy of PB-NK cells in the treatment of solid tumors, such as ovarian carcinoma and lung cancer, has been limited,10,15 likely as a result of the poor infiltration, inefficient homing, lack of specificity, and decreased persistence of NK cells in these patients.52 The solid tumor microenvironment can also act to decrease immune cell functions, including the elicitation of CD16 shedding.53 Human pluripotent stem cell-derived NK cells provide a novel option for adoptive immune cell therapy that may avoid some of the limitations of PB-NK cells and UCB-NK cells.20,24 Specifically, iPSCs can be routinely genetically modified on a clonal level to produce a homogeneous population of uniform engineered NK cells, rather than the heterogeneous NK cells that are typically obtained from peripheral blood or umbilical cord blood.21 Additionally, iNK cells can be expanded into a clinically scalable cell population that is suitable to treat hundreds or thousands of patients simultaneously. Indeed, our studies demonstrate that repeat dosing, combined with a targeting mAb, leads to long-term elimination of otherwise refractory tumor cells in these xenograft models (Figures 4 and 5).

Unlike autologous CAR-T cells that persist and remain functional for years posttransplantation,54 allogeneic NK cells normally survive in the host for only a few weeks in the adoptive transfer setting.2,7,10,19 However, considering the toxicities seen with CAR T-cell therapies,55 this property of allogeneic NK cells may be advantageous to enable more precise dosing strategies without significant concern for limiting toxicities. The use of PB-NK cells and UCB-NK cells does not typically allow for repeat dosing, because all of the cells collected or produced are used for the initial treatment, often after a dose of lymphodepleting chemotherapy. Indeed, clinical trials using genetically unmodified iPSC-derived NK cells have been initiated with repeat cell dosing on a weekly basis, for a total of 3 doses (clinicaltrials.gov NCT03841110). Other treatment schedules, such as monthly dosing, possibly combined with chemotherapy to treat solid tumors, can also be envisioned. Because previous trials of allogeneic NK cell–based therapies utilizing PB-NK cells, UCB-NK cells, or NK92 cells did not show complications, such as cytokine release syndrome, neurotoxicity, or graft-versus-host disease, that are seen with CAR T cells, these trials will be essential to demonstrate the safety and suitability of this multidosing strategy.

A recent study demonstrated that ADAM17-mediated CD16a shedding plays a role in the disassembly of the NK cell immune synapse during ADCC and regulates NK cell motility and detachment from target cells, potentially leading to improved NK cell–mediated serial killing of tumor targets.56 However, we did not observe the inhibition of detachment from targets by hnCD16 in hnCD16-iNK cells (supplemental Figure 5). Furthermore, a direct comparison in long-term assays showed superior killing with hnCD16 compared with wild-type CD16. The discrepancy might be caused by different NK cells used in these studies. Srpan et al56 used NK-92 cells, which do not express endogenous CD16 and cannot mediate ADCC. Moreover, those studies did not test the effects of blocking CD16a shedding on NK cell effector functions in vivo and, in particular, in the tumor microenvironment. Notably, NK cells from patients with solid tumors have been shown to have lower CD16 expression and function compared with healthy controls.57 For these studies, we used multiple in vivo tumor models that all demonstrate the benefits of stable high-level noncleavable CD16a expression by NK cells.

In conclusion, this platform therapy provides high impact for immediate translation because it can be combined with essentially any readily available anti-tumor antibody (eg, rituximab, trastuzumab, or cetuximab). This offers several advantages over CAR T-cell therapy and avoids the complexities of developing individualized products with single specificity. Our data demonstrate the advantages of multidosing strategies and the ability to use cryopreserved iNK cell products to provide a new off-the-shelf therapeutic strategy for improved cancer control when used in combination with anti-cancer mAbs that mediate ADCC.

Data sharing requests should be sent to Dan S. Kaufman (dskaufman@ucsd.edu).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute grants R01 CA203348 (D.S.K. and B.W.), U01 CA217885 (D.S.K.), and P01 CA111412 (to J.S.M.), and by Fate Therapeutics (D.S.K. and J.S.M.).

Authorship

Contribution: H.Z. and R.B. designed and implemented studies, acquired and analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; R.H.B. acquired and analyzed data and wrote the manuscript; S.G., P.R., G.B.B., and P.-F.T. acquired data; T.T.L. and R.A. designed and implemented studies and acquired and analyzed data; J.W. designed studies, generated the noncleavable human CD16 construct, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; J.S.M. and B.W. designed studies and reviewed and revised the manuscript; and B.V. and D.S.K. designed studies, analyzed data, and reviewed and revised the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: R.B., S.G., P.R., T.T.L., R.A., G.B.B., P.-F.T., and B.V. are employees of Fate Therapeutics with stock holdings and options. J.S.M. consults for and hold stock options in Fate Therapeutics, a company which may commercially benefit from the results of this research project. These interests have been reviewed and managed by the University of Minnesota in accordance with its conflict of interest policy. B.W. collaborates with Fate Therapuetics with a sponsored research agreement. D.S.K. is a consultant for Fate Therapeutics, has equity and receives income. The terms of this arrangement have been reviewed and approved by the University of California, San Diego in accordance with its conflict of interest policies.The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Dan S. Kaufman, University of California, San Diego, 9500 Gilman Dr, MC 0695, La Jolla, CA 92093; e-mail: dskaufman@ucsd.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal