Key Points

Patients with cancer are at high risk of clinically relevant bleeding, regardless of anticoagulation use.

The occurrence of clinically relevant bleeding is associated with an increased all-cause mortality.

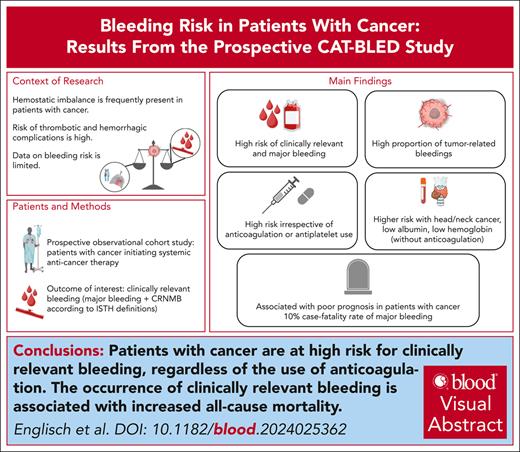

Visual Abstract

Hemostatic imbalances are frequent in patients with cancer. Although cancer-associated thrombotic complications have been well characterized, data on bleeding events in patients with cancer are sparse. Therefore, we aimed to investigate the incidence, risk factors, and impact on prognosis of bleeding events in patients with cancer initiating systemic anticancer therapies in a prospective cohort study, the Vienna Cancer, Thrombosis, and Bleeding Study. The primary study outcome was defined as clinically relevant bleeding (CRB), comprising major bleeding (MB) and clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding. In total, 791 patients (48% female), with median age of 63 years (interquartile range [IQR], 54-70), with various cancer types, 65.5% stage IV, were included. Over a median follow-up of 19 months (IQR, 8.7-24.0), we observed 194 CRB events in 139 (17.6%) patients, of which 42 (30.0%) were tumor related, 64 (46.0%) gastrointestinal, and 7 (5.0%) intracerebral. The 12-month cumulative incidence of first CRB and MB was 16.6% (95% confidence interval [CI], 13.7-19.6) and 9.1% (95% CI, 6.8-11.3), respectively, in the whole cohort, and 14.4% (95% CI, 11.2-17.5) and 7.0% (95% CI, 4.7-9.2), respectively, in those without anticoagulation. Patients with head and neck cancer had the highest risk of CRB. Lower baseline hemoglobin and albumin were associated with bleeding in patients without anticoagulation. Seven (5.0%) bleeding events were fatal, of which 6 occurred in patients without anticoagulation. Patients with CRB were at an increased risk of all-cause mortality (multivariable transition hazard ratio, 5.80; 95% CI, 4.53-7.43). In patients with cancer, bleeding events represent a frequent complication and are associated with increased mortality.

Introduction

Hemostatic dysregulation is frequently observed in patients with cancer and can result either in a prothrombotic state, a bleeding tendency, or both.1 Although the risk of cancer-associated venous thromboembolism (VTE) has been well characterized, little data are available regarding bleeding risk in patients with cancer.2 However, data on baseline bleeding risk in patients with cancer would be extremely valuable for several reasons.

Based on the high risk of VTE in patients with cancer,3,4 individual risk assessment and primary thromboprophylaxis is suggested in recent guidelines.5,6 However, prophylactic anticoagulation for primary prevention may come at an increased bleeding risk, challenging the application in an unselected cancer patient population.7,8 Consequently, it is highly relevant to assess both thrombotic and bleeding risk for clinical decision-making.

Furthermore, therapeutic anticoagulation is used in the treatment of cancer-associated VTE and in a relevant proportion of patients because of coprevalent conditions including atrial fibrillation.4,5,9 Patients with cancer receiving anticoagulation have a higher bleeding risk than patients with VTE without cancer.8 However, data on bleeding risk in patients with cancer with and without anticoagulation mostly stem from clinical trials (treatment arms of cancer-associated VTE therapy or placebo arms of primary VTE prevention), encompassing selected patient populations without significant comorbidities or poor performance status, which complicates the generalizability for routine clinical practice.10,11

Furthermore, risk factors for bleeding events specifically in patients with cancer are insufficiently characterized, and existing risk assessment tools derived primarily in noncancer populations performed poorly in patients with cancer.12 Lastly, the clinical consequences of cancer-associated bleeding events are currently not well described. Although the case-fatality rate of major bleeding (MB) in patients with cancer receiving anticoagulation is high at almost 10%,13 to our knowledge, to date, no studies have investigated the outcomes of bleeding in patients with cancer without anticoagulant therapy.

Therefore, our aim was to comprehensively characterize the clinical patterns of bleeding events and to determine their incidence, risk factors, and impact on prognosis in a prospective cohort including patients with cancer initiating systemic anticancer therapies. These aims represent the underlying objective to enable improved personalized clinical decision-making in patients with cancer.

Methods

Study design and patient population

This study was performed in the framework of an ongoing, prospective observational cohort study at the Medical University of Vienna, Austria, the Vienna Cancer, Thrombosis, and Bleeding Study (CAT-BLED Study), initiating patient recruitment in July 2019.

Consecutive patients referred to the oncological day clinic (a clinic that patients attend to receive their systemic anticancer therapy) with histologically confirmed cancer initiating systemic anticancer therapy; both patients with newly diagnosed and those with recurrent/progressive cancer after previous anticancer therapies were eligible for inclusion. Written informed consent for study participation was obtained from all included individuals. Exclusion criteria included incapacity or refusal of informed consent and age <18 years. Biobanking was conducted within the Translational Research Unit Biobanking Program for Personalized Immunotherapy of the Division of Oncology at the Medical University of Vienna. For this study, patients recruited between July 2019 and December 2022 were included. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Medical University of Vienna (approval numbers: EK 1533/2019 and EK 1164/2019) and has been conducted in full conformity with the International Conference of Harmonization guidelines on good clinical practice and the Declaration of Helsinki by the World Medical Association.

Study follow-up

At study inclusion, patients underwent a clinical interview and data on baseline clinical risk profiles and therapies were gathered. During routine visits at the oncology outpatient clinic for the receipt of their anticancer therapies, patients were followed-up in person for a maximum of 2 years and were asked to fill out a questionnaire (or conduct a personal interview when filling out questionnaires was refused) about any occurrences of thrombotic or bleeding events. The questions regarding bleeding included inquiries about: (1) occurrence of a bleeding event, (2) type of bleeding event (examples were provided in the distributed questionnaires), (3) date of the bleeding event, and (4) necessity to seek medical care because of the bleeding event. All events were also reviewed through electronic medical records to gather comprehensive medical data to allow for objective and independent adjudication. Additionally, in case of patients no longer showing up for routine follow-up visits, additional efforts were made to gather information, such as contacting patients, their relatives, or their treating physicians by letter or phone additionally to collecting information via electronic medical records screening. Patients were censored at the date on which they were last seen alive without event. Key secondary outcomes of the CAT-BLED study include any type of bleeding, progression free survival, and overall survival. The focus of this analysis was to analyze the incidence, risk factors, and impact on prognosis of bleeding events.

Outcomes of interest

Bleeding events were classified according to the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis definition of MB, clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding (CRNMB), and minor bleeding.14 A detailed description is provided in supplemental Material, available on the Blood website. The composite of MB and CRNMB was defined as clinically relevant bleeding (CRB). For this analysis, CRB was the primary outcome of interest, whereas MB and CRNMB were key secondary outcomes.

All bleeding events were adjudicated by an independent committee, consisting of experts in the field of hemostasis who were not involved in the conduction of the study. The members of the adjudication committee confirmed the diagnosis, the clinical significance, and the definition of these events.

A detailed definition of thrombocytopenia and therapeutic anticoagulation is included in supplemental Material.

Statistical analysis

Standard summary statistics were used to report patient baseline characteristics (absolute frequency, percentage, median, and interquartile range [IQR]). Median follow-up time was calculated with a reverse Kaplan-Meier analysis.

The cumulative incidence of a first bleeding event was calculated separately for CRB, MB, and CRNMB (eg, a first MB was not necessarily also a first CRB). Thus, time to first CRB, MB, or CRNMB was used for all time-to-event analyses. Based on the anticipated high risk of underlying mortality, competing risk analysis was conducted, accounting for all-cause mortality as competing outcome event.15 Univariable and multivariable modeling of time to event were performed with a proportional subdistribution hazards regression model according to Fine and Gray.16 Accordingly, subdistribution hazard ratios (HRs) describe the association of covariates with CRB, MB, or CRNMB. The 6-, 12-, and 24-month cumulative incidences of CRB, MB, or CRNMB were computed using competing risk cumulative incidence functions. Selection of baseline characteristics was based on previous data and domain knowledge. The Gray test was used to compare the cumulative incidence functions of ≥2 subgroups.17 When evaluating incidence according to laboratory values, low hemoglobin was defined as ≤10 g/dL (Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events grade 2 anemia) and low albumin as ≤35 g/L (lower normal limit of the central routine laboratory of the Medical University of Vienna). All-cause mortality was investigated in Kaplan-Meier analysis. To assess the association of CRB events with mortality, CRB was used as a time-dependent covariable in a Cox regression model for overall survival, calculating the transition HR (THR) in a multistate model.18 The analysis was adjusted for patient age, sex, stage, and tumor type. Furthermore, we performed a landmark analysis comparing the overall survival of patients with and without CRB, with the landmark set at 3 months after study inclusion. In patients without anticoagulants, we performed subgroup analyses. For these analyses, patients with anticoagulation at study inclusion were excluded and those starting any anticoagulation at a therapeutic dose during the follow-up period were censored at the start date of the anticoagulation treatment.

Statistical analyses were performed with STATA 17 (Stata Corp, Houston, TX), SPSS 28.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics, Chicago, IL), and R Statistical Software (version 4.2.0; R Core Team 2022, Vienna, Austria). The α level was set at 0.05.

Results

Patient cohort

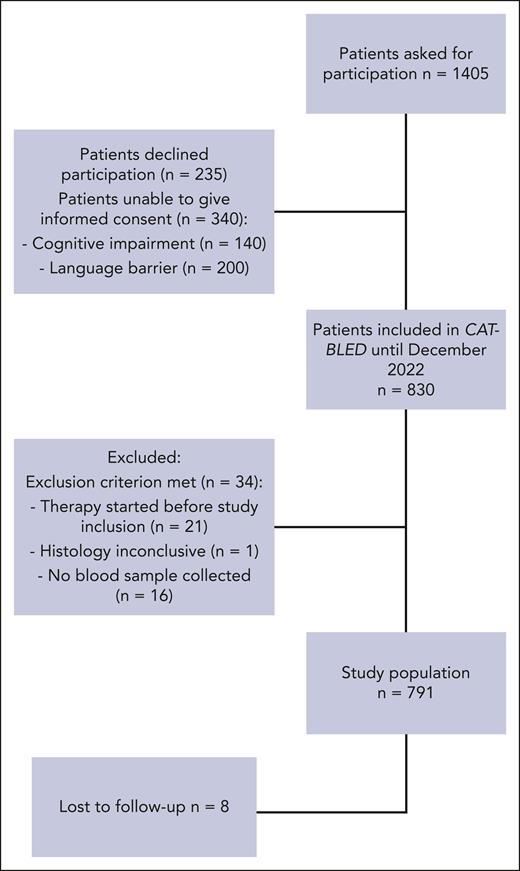

In total, 791 patients were included (median age: 63 years [IQR, 54-70]; 47.7% female, study flowchart as Figure 1). Of those, 403 (50.9%) had newly diagnosed cancer at study inclusion, whereas 388 (49.1%) had progressive or recurrent cancer after previous anticancer therapies. The most frequent cancer types were lung (23.6%), head and neck (11.1%), and pancreas (10.4%). A total of 518 patients (65.5%) had metastatic disease at study inclusion.

At the time of study inclusion, 120 patients (15.2%) were receiving therapeutic anticoagulation, and 124 (15.7%) patients were receiving antiplatelet therapy. During a median follow-up time of 19 months (IQR, 8.7-24.0), 366 (46.3%) patients died (6- and 12-month cumulative all-cause mortality, 21.7%; [95% confidence interval, CI, 18.5-24.7]; and 39.5% [95% CI, 35.5-43.4], respectively). Detailed patient characteristics at study inclusion are presented in Table 1.

Characteristics at study inclusion of all patients, stratified according to the occurrence of a first bleeding event in the follow-up period

| . | Total study population (n = 791) . | Patients who developed CRB (n = 139) . | Patients who developed MB (n = 70) . | Patients who developed CRNMB (n = 87) . | Patients without bleeding (n = 652) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 377 (47.7) | 73 (52.5) | 27 (38.6) | 46 (52.9) | 312 (47.9) |

| Age, y | 63 (54-70) | 63 (55-70) | 64 (56-70) | 62 (53-70) | 63 (54-70) |

| BMI | 23.8 (20.8-26.9) | 23.3 (21.0-25.8) | 23.3 (21.1-26.0) | 22.9 (20.5-25.3) | 24.0 (20.8-27.1) |

| Tumor type | |||||

| Lung | 187 (23.6) | 34 (24.5) | 11 (15.7) | 25 (28.7) | 153 (23.5) |

| Head and neck | 88 (11.1) | 25 (18.0) | 14 (20.0) | 15 (17.2) | 63 (9.7) |

| Urinary | 15 (1.9) | 2 (1.4) | 0 | 2 (2.3) | 13 (2.0) |

| Breast | 74 (9.4) | 10 (7.2) | 4 (5.7) | 7 (8.0) | 64 (9.8) |

| Colorectal | 58 (7.3) | 7 (5.0) | 4 (5.7) | 3 (3.4) | 51 (7.8) |

| Pancreas | 82 (10.4) | 21 (15.1) | 17 (24.3) | 8 (9.2) | 61 (9.4) |

| Esophageal | 27 (3.4) | 6 (4.3) | 4 (5.7) | 3 (3.4) | 21 (3.2) |

| Stomach | 35 (4.4) | 8 (5.8) | 3 (4.3) | 7 (8.0) | 27 (4.1) |

| Brain | 52 (6.6) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (1.4) | 0 | 51 (7.8) |

| Liver | 38 (4.8) | 8 (5.8) | 4 (5.7) | 6 (6.9) | 30 (4.6) |

| Prostate | 6 (0.8) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 (0.9) |

| Sarcoma | 59 (7.5) | 5 (3.6) | 1 (1.4) | 4 (4.6) | 54 (8.3) |

| Lymphoma | 11 (1.4) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 (1.7) |

| Gynecological | 2 (0.3) | 1 (50.0) | 0 | 1 (1.1) | 1 (0.2) |

| Other | 57 (7.2) | 12 (8.6) | 7 (10) | 6 (6.9) | 45 (6.9) |

| Newly diagnosed cancer | 403 (51.0) | 72 (51.8) | 34 (48.6) | 47 (54.0) | 331 (50.8) |

| Recurrent or progressive cancer | 388 (49.0) | 68 (48.2) | 36 (51.4) | 40 (46.0) | 320 (49.2) |

| Stage of cancer | |||||

| Localized | 84 (10.6) | 12 (8.6) | 6 (8.6) | 7 (8.0) | 72 (11.1) |

| Lymph nodes | 136 (17.2) | 36 (25.9) | 16 (22.9) | 25 (28.7) | 100 (15.4) |

| Distant metastatic | 518 (65.5) | 90 (64.7) | 46 (65.7) | 55 (63.2) | 428 (65.7) |

| Systemic therapy after study inclusion | |||||

| Chemotherapy | 361 (45.6) | 64 (46.0) | 35 (50.0) | 34 (39.1) | 297 (45.6) |

| Immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy | 136 (17.2) | 26 (18.7) | 10 (14.3) | 20 (23.0) | 110 (16.9) |

| Chemotherapy and immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy | 128 (16.2) | 31 (22.3) | 12 (17.1) | 22 (25.3) | 97 (14.9) |

| Targeted therapy and chemotherapy | 90 (11.4) | 13 (9.4) | 8 (11.4) | 9 (10.3) | 77 (11.8) |

| Targeted | 38 (4.8) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (1.4) | 0 | 37 (5.7) |

| No systemic therapy | 27 (3.3) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (1.4) | 0 | 26 (4.0) |

| Targeted and immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy | 10 (1.3) | 4 (2.9) | 3 (4.3) | 2 (2.3) | 6 (0.9) |

| Tyrosine kinase inhibitors | 1 (0.1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.2) |

| History of any bleeding | 117 (14.8) | 21 (15.1) | 7 (10.0) | 15 (17.2) | 96 (14.7) |

| History of VTE | 98 (12.4) | 14 (10.1) | 7 (10.0) | 8 (9.2) | 84 (12.9) |

| History of ATE | 70 (8.8) | 12 (8.6) | 4 (5.7) | 8 (9.2) | 58 (8.9) |

| Arterial hypertension | 279 (35.3) | 57 (41.0) | 23 (32.9) | 38 (43.7) | 222 (34.0) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 49 (6.2) | 15 (10.8) | 8 (11.4) | 9 (10.3) | 34 (5.2) |

| Therapeutic anticoagulation∗ | 120 (15.2) | 23 (16.5) | 13 (18.6) | 12 (13.8) | 97 (14.9) |

| Antiplatelet therapy | 124 (15.7) | 26 (18.7) | 12 (17.1) | 18 (20.7) | 98 (15.0) |

| ECOG PS score | |||||

| 0 | 497 (62.8) | 83 (59.7) | 36 (51.4) | 53 (60.9) | 414 (63.6) |

| 1 | 206 (26.0) | 42 (30.2) | 22 (31.4) | 28 (32.2) | 164 (25.5) |

| 2 | 48 (6.1) | 11 (7.9) | 10 (14.3) | 3 (3.4) | 37 (5.7) |

| 3 | 3 (0.4) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (0.5) |

| . | Total study population (n = 791) . | Patients who developed CRB (n = 139) . | Patients who developed MB (n = 70) . | Patients who developed CRNMB (n = 87) . | Patients without bleeding (n = 652) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 377 (47.7) | 73 (52.5) | 27 (38.6) | 46 (52.9) | 312 (47.9) |

| Age, y | 63 (54-70) | 63 (55-70) | 64 (56-70) | 62 (53-70) | 63 (54-70) |

| BMI | 23.8 (20.8-26.9) | 23.3 (21.0-25.8) | 23.3 (21.1-26.0) | 22.9 (20.5-25.3) | 24.0 (20.8-27.1) |

| Tumor type | |||||

| Lung | 187 (23.6) | 34 (24.5) | 11 (15.7) | 25 (28.7) | 153 (23.5) |

| Head and neck | 88 (11.1) | 25 (18.0) | 14 (20.0) | 15 (17.2) | 63 (9.7) |

| Urinary | 15 (1.9) | 2 (1.4) | 0 | 2 (2.3) | 13 (2.0) |

| Breast | 74 (9.4) | 10 (7.2) | 4 (5.7) | 7 (8.0) | 64 (9.8) |

| Colorectal | 58 (7.3) | 7 (5.0) | 4 (5.7) | 3 (3.4) | 51 (7.8) |

| Pancreas | 82 (10.4) | 21 (15.1) | 17 (24.3) | 8 (9.2) | 61 (9.4) |

| Esophageal | 27 (3.4) | 6 (4.3) | 4 (5.7) | 3 (3.4) | 21 (3.2) |

| Stomach | 35 (4.4) | 8 (5.8) | 3 (4.3) | 7 (8.0) | 27 (4.1) |

| Brain | 52 (6.6) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (1.4) | 0 | 51 (7.8) |

| Liver | 38 (4.8) | 8 (5.8) | 4 (5.7) | 6 (6.9) | 30 (4.6) |

| Prostate | 6 (0.8) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 (0.9) |

| Sarcoma | 59 (7.5) | 5 (3.6) | 1 (1.4) | 4 (4.6) | 54 (8.3) |

| Lymphoma | 11 (1.4) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 (1.7) |

| Gynecological | 2 (0.3) | 1 (50.0) | 0 | 1 (1.1) | 1 (0.2) |

| Other | 57 (7.2) | 12 (8.6) | 7 (10) | 6 (6.9) | 45 (6.9) |

| Newly diagnosed cancer | 403 (51.0) | 72 (51.8) | 34 (48.6) | 47 (54.0) | 331 (50.8) |

| Recurrent or progressive cancer | 388 (49.0) | 68 (48.2) | 36 (51.4) | 40 (46.0) | 320 (49.2) |

| Stage of cancer | |||||

| Localized | 84 (10.6) | 12 (8.6) | 6 (8.6) | 7 (8.0) | 72 (11.1) |

| Lymph nodes | 136 (17.2) | 36 (25.9) | 16 (22.9) | 25 (28.7) | 100 (15.4) |

| Distant metastatic | 518 (65.5) | 90 (64.7) | 46 (65.7) | 55 (63.2) | 428 (65.7) |

| Systemic therapy after study inclusion | |||||

| Chemotherapy | 361 (45.6) | 64 (46.0) | 35 (50.0) | 34 (39.1) | 297 (45.6) |

| Immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy | 136 (17.2) | 26 (18.7) | 10 (14.3) | 20 (23.0) | 110 (16.9) |

| Chemotherapy and immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy | 128 (16.2) | 31 (22.3) | 12 (17.1) | 22 (25.3) | 97 (14.9) |

| Targeted therapy and chemotherapy | 90 (11.4) | 13 (9.4) | 8 (11.4) | 9 (10.3) | 77 (11.8) |

| Targeted | 38 (4.8) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (1.4) | 0 | 37 (5.7) |

| No systemic therapy | 27 (3.3) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (1.4) | 0 | 26 (4.0) |

| Targeted and immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy | 10 (1.3) | 4 (2.9) | 3 (4.3) | 2 (2.3) | 6 (0.9) |

| Tyrosine kinase inhibitors | 1 (0.1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.2) |

| History of any bleeding | 117 (14.8) | 21 (15.1) | 7 (10.0) | 15 (17.2) | 96 (14.7) |

| History of VTE | 98 (12.4) | 14 (10.1) | 7 (10.0) | 8 (9.2) | 84 (12.9) |

| History of ATE | 70 (8.8) | 12 (8.6) | 4 (5.7) | 8 (9.2) | 58 (8.9) |

| Arterial hypertension | 279 (35.3) | 57 (41.0) | 23 (32.9) | 38 (43.7) | 222 (34.0) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 49 (6.2) | 15 (10.8) | 8 (11.4) | 9 (10.3) | 34 (5.2) |

| Therapeutic anticoagulation∗ | 120 (15.2) | 23 (16.5) | 13 (18.6) | 12 (13.8) | 97 (14.9) |

| Antiplatelet therapy | 124 (15.7) | 26 (18.7) | 12 (17.1) | 18 (20.7) | 98 (15.0) |

| ECOG PS score | |||||

| 0 | 497 (62.8) | 83 (59.7) | 36 (51.4) | 53 (60.9) | 414 (63.6) |

| 1 | 206 (26.0) | 42 (30.2) | 22 (31.4) | 28 (32.2) | 164 (25.5) |

| 2 | 48 (6.1) | 11 (7.9) | 10 (14.3) | 3 (3.4) | 37 (5.7) |

| 3 | 3 (0.4) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (0.5) |

Values are presented as absolute numbers (percentages) or median (IQR). Percentages are calculated per column.

ATE, arterial thromboembolism; BMI, body mass index; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status.

Defined as anticoagulation for VTE treatment or anticoagulation for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation or anticoagulation in patients with mechanical heart valves or vascular grafts.

Overall risk of bleeding

During follow-up, 139 (17.6%) patients experienced 194 CRB events; 87 patients (11.0%) experienced 110 CRNMB, and 70 patients (8.8%) experienced 84 MB events.

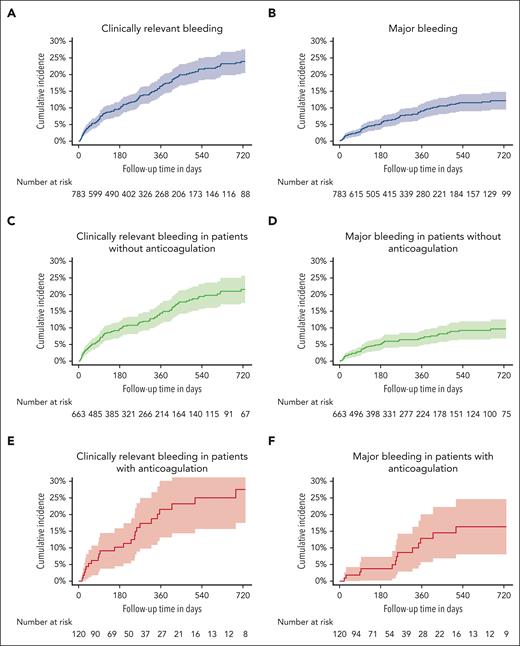

The 6-, 12-, and 24-month cumulative incidences of CRB were 9.8% (95% CI, 7.6-12.1), 16.6% (95% CI, 13.7-19.6), and 23.9% (95% CI, 20.3-27.6), respectively (Figure 2A). The 6-, 12-, and 24-month cumulative incidences of MB were 5.1% (95% CI, 3.4-6.7), 9.1% (95% CI, 6.8-11.3), and 12.1% (95% CI, 9.4-14.9; Figure 2B), respectively. The 6-, 12-, and 24-month cumulative incidences of CRNMB were 5.9% (95% CI, 4.2-7.7), 10.0% (95% CI, 7.6-12.3), and 14.7% (95% CI, 11.6-17.7), respectively (supplemental Figure 1).

Cumulative bleeding incidences. Cumulative incidence of CRB and MB in the full study cohort (n = 791, A-B), in patients without anticoagulation (n = 671, C-D), and patients with anticoagulation at study inclusion (n = 120, E-F).

Cumulative bleeding incidences. Cumulative incidence of CRB and MB in the full study cohort (n = 791, A-B), in patients without anticoagulation (n = 671, C-D), and patients with anticoagulation at study inclusion (n = 120, E-F).

Clinical characteristics of bleeding events

Of 139 first CRB events, 62 (44.6%) were MB, whereas 77 (55.4%) were CRNMB events. Overall, 42 (30.0%) bleeding events were considered tumor-related bleedings (ie, the bleeding location was the tumor site; supplemental Table 2) of which most were oropharyngeal (33.3%) or pulmonary (21.4%) CRB. Furthermore, 64 (46.0%) events were gastrointestinal (GI), 16 (11.5%) urogenital, and 7 (5.0%) intracerebral bleedings. At the time of CRB, 43 (30.7%) patients were receiving therapeutic anticoagulation and 17 (12.1%) prophylactic anticoagulation, and 15 (10.7%) had thrombocytopenia. Detailed information about clinical characteristics of bleeding events are summarized in Table 2, with detailed patient characteristics at the time of bleeding in supplemental Table 1.

Detailed bleeding characteristics of first MB or first CRB in the full cohort (overall), and in those with and those without therapeutic anticoagulation

| . | Overall . | Therapeutic anticoagulation . | No therapeutic anticoagulation . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MB (n = 70) . | CRB (n = 139) . | MB (n = 27) . | CRB (n = 43) . | MB (n = 43) . | CRB (n = 96) . | |

| Site of bleeding | ||||||

| Cutaneous | 1 (1.4) | 9 (6.5) | 0 | 3 (7.0) | 1 (2.3) | 6 (6.3) |

| Epistaxis | 2 (2.9) | 12 (8.6) | 1 (3.7) | 5 (11.6) | 1 (2.3) | 7 (7.3) |

| Intracranial | 8 (11.4) | 7 (5.0) | 4 (14.8) | 4 (9.3) | 4 (9.3) | 3 (3.1) |

| GI | 42 (60.0) | 64 (46.0) | 19 (70.4) | 22 (51.2) | 23 (53.5) | 42 (43.8) |

| Lower GI | 15 (21.4) | 30 (21.6) | 7 (25.9) | 8 (18.6) | 8 (18.6) | 22 (22.9) |

| Upper GI | 27 (38.6) | 34 (24.4) | 12 (44.4) | 14 (32.6) | 15 (34.9) | 20 (20.8) |

| Oropharyngeal | 8 (11.4) | 15 (10.8) | 0 | 1 (2.3) | 8 (18.6) | 13 (13.5) |

| Other | 3 (3.3) | 5 (3.6) | 1 (3.7) | 1 (2.3) | 2 (4.7) | 4 (4.2) |

| Pulmonary | 2 (2.9) | 11 (7.9) | 1 (3.7) | 3 (7.0) | 1 (2.3) | 8 (8.3) |

| Urinary tract | 4 (5.7) | 12 (8.6) | 1 (3.7) | 3 (7.0) | 3 (7.0) | 9 (9.4) |

| Vaginal | 0 | 4 (2.9) | 0 | 1 (2.3) | 0 | 3 (3.1) |

| Tumor bleeding∗ | 23 (32.9) | 42 (30.2) | 9 (33.3) | 11 (25.6) | 14 (32.6) | 30 (31.3) |

| Recent history of surgery or invasive procedure | 3 (4.3) | 5 (3.6) | 1 (3.7) | 1 (2.3) | 2 (4.7) | 4 (4.2) |

| Traumatic | 6 (8.6) | 7 (5.0) | 1 (3.7) | 3 (7.0) | 3 (7.0) | 4 (4.2) |

| Incidental† | 0 | 1 (0.7) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.0) |

| Fatal | 7 (10.0) | 7 (5.0) | 1 (3.7) | 1 (2.3) | 6 (13.9) | 6 (6.3) |

| . | Overall . | Therapeutic anticoagulation . | No therapeutic anticoagulation . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MB (n = 70) . | CRB (n = 139) . | MB (n = 27) . | CRB (n = 43) . | MB (n = 43) . | CRB (n = 96) . | |

| Site of bleeding | ||||||

| Cutaneous | 1 (1.4) | 9 (6.5) | 0 | 3 (7.0) | 1 (2.3) | 6 (6.3) |

| Epistaxis | 2 (2.9) | 12 (8.6) | 1 (3.7) | 5 (11.6) | 1 (2.3) | 7 (7.3) |

| Intracranial | 8 (11.4) | 7 (5.0) | 4 (14.8) | 4 (9.3) | 4 (9.3) | 3 (3.1) |

| GI | 42 (60.0) | 64 (46.0) | 19 (70.4) | 22 (51.2) | 23 (53.5) | 42 (43.8) |

| Lower GI | 15 (21.4) | 30 (21.6) | 7 (25.9) | 8 (18.6) | 8 (18.6) | 22 (22.9) |

| Upper GI | 27 (38.6) | 34 (24.4) | 12 (44.4) | 14 (32.6) | 15 (34.9) | 20 (20.8) |

| Oropharyngeal | 8 (11.4) | 15 (10.8) | 0 | 1 (2.3) | 8 (18.6) | 13 (13.5) |

| Other | 3 (3.3) | 5 (3.6) | 1 (3.7) | 1 (2.3) | 2 (4.7) | 4 (4.2) |

| Pulmonary | 2 (2.9) | 11 (7.9) | 1 (3.7) | 3 (7.0) | 1 (2.3) | 8 (8.3) |

| Urinary tract | 4 (5.7) | 12 (8.6) | 1 (3.7) | 3 (7.0) | 3 (7.0) | 9 (9.4) |

| Vaginal | 0 | 4 (2.9) | 0 | 1 (2.3) | 0 | 3 (3.1) |

| Tumor bleeding∗ | 23 (32.9) | 42 (30.2) | 9 (33.3) | 11 (25.6) | 14 (32.6) | 30 (31.3) |

| Recent history of surgery or invasive procedure | 3 (4.3) | 5 (3.6) | 1 (3.7) | 1 (2.3) | 2 (4.7) | 4 (4.2) |

| Traumatic | 6 (8.6) | 7 (5.0) | 1 (3.7) | 3 (7.0) | 3 (7.0) | 4 (4.2) |

| Incidental† | 0 | 1 (0.7) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.0) |

| Fatal | 7 (10.0) | 7 (5.0) | 1 (3.7) | 1 (2.3) | 6 (13.9) | 6 (6.3) |

Values are presented as absolute numbers (percentages). Percentages are calculated per column.

That is, the bleeding location was the tumor site

That is, imaging was performed due to other reasons (eg, staging) and a bleeding into tumor tissue was detected

Bleeding risk in patients receiving therapeutic anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy

Overall, 120 patients received anticoagulation at study inclusion. In those, the subdistribution HR (SHR) for CRB was 1.16 (95% CI, 0.82-1.65); for MB 1.19 (95% CI, 0.94-1.50); and for CRNMB 1.24 (95% CI, 0.98-1.57). Furthermore, in patients receiving antiplatelet therapy at study baseline, the SHR for CRB was 1.11 (95% CI, 0.74-1.66), for MB was 1.06 (95% CI, 0.81-1.40), and for CRNMB was 1.00 (95% CI, 0.76-1.32); and was 1.64 (95% CI, 0.76-3.52), 1.14 (95% CI, 0.69-1.90), and 0.66 (95% CI, 0.35-1.24), respectively, in patients receiving both anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy.

Details on cumulative bleeding incidences in patients with anticoagulation (n = 120, 15.2% of study cohort; Figure 2E-F), with antiplatelet therapy (n = 124; supplemental Figure 2A-B), with both anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy (n = 26; supplemental Figure 2C-D), and without both anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy (n = 559) are provided in supplemental Table 3.

Risk factors for bleeding events in patients without anticoagulation

Next, we evaluated the bleeding risk and association of clinicopathologic characteristics of patients at study inclusion with future bleeding risk in patients without anticoagulation therapy.

The 6-, 12-, and 24-month cumulative incidences of CRB in patients receiving no anticoagulation (n = 671, 84.8% of study cohort) were 9.6% (95% CI, 7.2-12.1), 14.4% (95% CI, 11.2-17.5), and 21.5% (95% CI, 17.4-25.6), respectively (Figure 2C), with incidences of MB of 5.0% (95% CI, 3.2-6.9), 7.0% (95% CI, 4.7-9.2), and 9.7% (95% CI, 6.8-12.5), respectively (Figure 2D). The 6-, 12-, and 24-month cumulative incidences of CRNMB were 3.7% (95% CI, 1.4-7.2), 12.8% (95% CI, 5.6-20.0), and 16.3% (95% CI, 8.0-24.6), respectively.

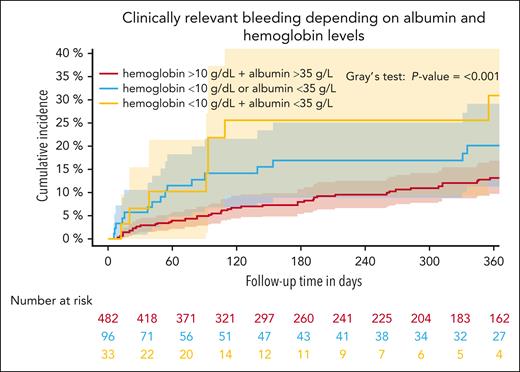

An increased CRB risk was observed in patients with head and neck cancer compared with the remainder of patients (SHR, 2.38; 95% CI, 1.46-3.88), whereas the risk of CRB was similar among other tumor type subgroups (Table 3). Accordingly, we observed the highest cumulative incidence of CRB in patients with head and neck cancer (supplemental Table 4; supplemental Figure 3). Stage IV (compared with stage I, II, and III) was associated with a lower bleeding risk, whereas history of any bleeding was not associated with bleeding risk (Table 3). Regarding baseline biomarker profiles, we observed higher CRB in patients with lower hemoglobin (SHR per increase of 1, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.79-0.98) and decreased albumin levels (SHR per increase of 1, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.92-0.99; Table 3). Patients with low hemoglobin levels at study inclusion (<10 g/dL) had a 6-month cumulative CRB incidence of 22.4% (95% CI, 11.6-33.2) compared with 8.2% (95% CI, 5.7-10.6) in those with higher hemoglobin levels (>10 g/dL; Gray test: P < .001). Furthermore, the 6-month cumulative incidence of CRB in patients with albumin levels of <35.0 g/L was 18.0% (95% CI, 10.4-25.5) compared with 8.5% (95% CI, 5.8-11.2) in those with higher levels (Gray test: P < .001). In patients with both parameters below the cutoff, the 6-month cumulative incidence was 25.5% (95% CI, 9.2-41.9) compared with 16.9% (95% CI, 8.8-25.0) when 1 parameter was below the cutoff and 7.9% (95% CI, 5.3-10.6) when no parameter was below the cutoff (Gray test: P = .001; Figure 3). Furthermore, higher platelet counts and aspartate transaminase levels were weakly associated with increased CRB risk (Table 3). Similar observations were made regarding the association with MB (Table 3; supplemental Figure 4). The association of other covariates of interest and CRB is depicted in Table 3.

Risk factors for CRB and MB at study inclusion in patients without anticoagulation

| . | CRB . | MB . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SHR . | 95% CI . | SHR . | 95% CI . | |

| Age (continuous per increase of 1, y) | 0.99 | 0.98-1.01 | 1.01 | 0.99-1.03 |

| BMI (continuous per increase of 1, kg/m2) | 0.97 | 0.95-1.01 | 0.98 | 0.94-1.02 |

| Hemoglobin (continuous per increase of 1, mg/dL) | 0.88 | 0.79-0.98 | 0.79 | 0.67-0.92 |

| Platelets (continuous per increase of 10, ×109/L) | 1.02 | 1.00-1.03 | 1.01 | 0.98-1.04 |

| Leucocytes (continuous per increase of 1, ×109/L) | 1.03 | 0.98-1.07 | 0.99 | 0.91-1.07 |

| Creatinine (continuous per increase of 1, mg/dL) | 1.09 | 0.92-1.30 | 1.09 | 0.82-1.46 |

| Albumin (continuous per increase of 1, g/L) | 0.95 | 0.92-0.99 | 0.91 | 0.87-0.95 |

| Aspartate transaminase (U/L, per increase of 10) | 1.02 | 1.00-1.04 | 1.03 | 1.00-1.05 |

| Alanine transaminase (U/L, per increase of 10) | 1.02 | 0.99-1.05 | 1.03 | 1.00-1.06 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/L, per increase of 10) | 1.01 | 0.99-1.02 | 1.02 | 1.00-1.03 |

| Stage IV (vs I, II, and III) | 0.53 | 0.35-0.79 | 0.72 | 0.38-1.37 |

| Head and neck vs other cancer type | 2.38 | 1.46-3.88 | 3.16 | 1.65-6.03 |

| GI vs other cancer type | 1.06 | 0.68-1.66 | 1.02 | 0.50-2.07 |

| Luminal GI vs other cancer type | 1.13 | 0.66-1.94 | 0.76 | 0.30-1.93 |

| Pancreas vs other cancer type | 0.76 | 0.33-1.72 | 1.48 | 0.58-3.78 |

| Lung vs other cancer type | 0.98 | 0.62-1.55 | 0.55 | 0.24-1.21 |

| Presence of recurrent/progressive cancer | 1.05 | 0.71-1.57 | 1.63 | 0.89-2.97 |

| First line vs other treatment line | 0.96 | 0.65-1.43 | 0.60 | 0.33-1.11 |

| Palliative therapy vs curative therapy | 1.19 | 0.55-2.56 | 1.32 | 0.41-4.26 |

| History of any bleeding | 1.49 | 0.89-2.49 | 1.09 | 0.49-2.46 |

| . | CRB . | MB . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SHR . | 95% CI . | SHR . | 95% CI . | |

| Age (continuous per increase of 1, y) | 0.99 | 0.98-1.01 | 1.01 | 0.99-1.03 |

| BMI (continuous per increase of 1, kg/m2) | 0.97 | 0.95-1.01 | 0.98 | 0.94-1.02 |

| Hemoglobin (continuous per increase of 1, mg/dL) | 0.88 | 0.79-0.98 | 0.79 | 0.67-0.92 |

| Platelets (continuous per increase of 10, ×109/L) | 1.02 | 1.00-1.03 | 1.01 | 0.98-1.04 |

| Leucocytes (continuous per increase of 1, ×109/L) | 1.03 | 0.98-1.07 | 0.99 | 0.91-1.07 |

| Creatinine (continuous per increase of 1, mg/dL) | 1.09 | 0.92-1.30 | 1.09 | 0.82-1.46 |

| Albumin (continuous per increase of 1, g/L) | 0.95 | 0.92-0.99 | 0.91 | 0.87-0.95 |

| Aspartate transaminase (U/L, per increase of 10) | 1.02 | 1.00-1.04 | 1.03 | 1.00-1.05 |

| Alanine transaminase (U/L, per increase of 10) | 1.02 | 0.99-1.05 | 1.03 | 1.00-1.06 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/L, per increase of 10) | 1.01 | 0.99-1.02 | 1.02 | 1.00-1.03 |

| Stage IV (vs I, II, and III) | 0.53 | 0.35-0.79 | 0.72 | 0.38-1.37 |

| Head and neck vs other cancer type | 2.38 | 1.46-3.88 | 3.16 | 1.65-6.03 |

| GI vs other cancer type | 1.06 | 0.68-1.66 | 1.02 | 0.50-2.07 |

| Luminal GI vs other cancer type | 1.13 | 0.66-1.94 | 0.76 | 0.30-1.93 |

| Pancreas vs other cancer type | 0.76 | 0.33-1.72 | 1.48 | 0.58-3.78 |

| Lung vs other cancer type | 0.98 | 0.62-1.55 | 0.55 | 0.24-1.21 |

| Presence of recurrent/progressive cancer | 1.05 | 0.71-1.57 | 1.63 | 0.89-2.97 |

| First line vs other treatment line | 0.96 | 0.65-1.43 | 0.60 | 0.33-1.11 |

| Palliative therapy vs curative therapy | 1.19 | 0.55-2.56 | 1.32 | 0.41-4.26 |

| History of any bleeding | 1.49 | 0.89-2.49 | 1.09 | 0.49-2.46 |

BMI, body mass index.

Cumulative incidence of CRB depending on the albumin and hemoglobin levels within 12 months of follow-up. Patients were grouped according to their hemoglobin and albumin levels. The group with hemoglobin of <10 g/dL and albumin of <35 g/L (n = 46), was compared with those with either hemoglobin of <10 g/dL or albumin of <35 g/L and those with no value below the cutoff within a Fine and Gray subdistribution hazard model within 12 months of follow-up, P < .001.

Cumulative incidence of CRB depending on the albumin and hemoglobin levels within 12 months of follow-up. Patients were grouped according to their hemoglobin and albumin levels. The group with hemoglobin of <10 g/dL and albumin of <35 g/L (n = 46), was compared with those with either hemoglobin of <10 g/dL or albumin of <35 g/L and those with no value below the cutoff within a Fine and Gray subdistribution hazard model within 12 months of follow-up, P < .001.

Bleeding and all-cause mortality

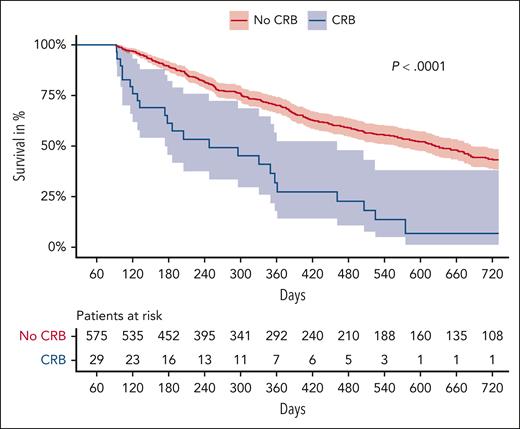

Overall, we observed 7 fatal bleeding events, with a case-fatality rate of CRB events of 5.0% and of MB events of 10.0%. Of 7 fatal bleeding events, 6 occurred in patients receiving no anticoagulation (case fatality rate of CRB, 6.3%; and of MB, 13.9%; respectively). Beyond immediate bleeding-related mortality, the occurrence of CRB was associated with an independent increase in risk of all-cause mortality (multivariable THR for death after CRB adjusted for age, sex, stage, and tumor type: 5.80; 95% CI, 4.53-7.43). Figure 4 depicts a landmark analysis of overall survival according to the occurrence of CRB within 3 months of observation (Mantel Byar: P < .001). Of all patients with a CRB (n = 139), 98 patients died (70%) during observation, compared with 244 (38%) patients without CRB (n = 652).

Landmark analysis of overall survival according to the occurrence of CRB. Overall survival curves are displayed stratified by the occurrence of CRB within 3 months after study inclusion.

Landmark analysis of overall survival according to the occurrence of CRB. Overall survival curves are displayed stratified by the occurrence of CRB within 3 months after study inclusion.

Sensitivity analysis

Because most studies include patients with newly diagnosed cancer, we assessed the cumulative incidence in the subgroup of patients with newly diagnosed cancer in the whole cohort and the subgroup without anticoagulation to evaluate its comparability. The CRB, MB, and CRNMB incidence of newly diagnosed patients was comparable with the whole cohort as well as to that of the subgroup of patients without anticoagulation (supplemental Table 5).

Discussion

In this prospective cohort of patients with cancer initiating systemic anticancer therapies, we observed a high risk of CRB and MB events. The observed characteristics of bleeding events were heterogeneous, with a considerable proportion of events characterized as tumor-related bleedings. We identified several risk factors for bleeding risk in patients without anticoagulation therapy, namely head and neck cancer and decreased hemoglobin and albumin levels. Furthermore, bleeding events had a considerable case fatality rate and were independently associated with higher long-term mortality.

The high risk of bleeding in patients with cancer in our study is only partly in line with bleeding rates previously reported in randomized controlled trials (RCTs), with a 6-month cumulative MB incidence ranging between 1.0% and 2.0% in the placebo groups of primary thromboprophylaxis RCTs with direct oral anticoagulants in patients with cancer,10,11 compared with 5% in the subgroup of patients without anticoagulation in our study. Several factors might explain the discrepancy, such as differences in patient characteristics included in RCTs based on inclusion and exclusion criteria resulting in the selection of patients with a lower baseline bleeding risk based on cancer types, age, comorbidities, and performance status. Furthermore, concomitant medication as well as a longer follow-up period might influence the bleeding risk in clinical practice cohorts.

Bleeding risk represents a dynamic pathophysiologic process, with many factors potentially affecting individual risk during the course of disease in patients with cancer, including comedication, platelet count, kidney function, or local factors concerning the cancer itself, including macrovascular involvement or luminal cancers of GI or genitourinary origin. To better understand this dynamic process, we summarized clinical characteristics of patients at the time of the bleeding event. Furthermore, we were able to identify a unique form of bleeding not previously accounted for in the characterization of bleeding events in clinical research, which we referred to as tumor-related bleeding (ie, bleeding location is the tumor site). Interestingly, tumor bleedings mainly occurred at the oropharyngeal or pulmonary site. This represents a novel category of bleeding, exclusive to patients with cancer, for which no established definition or standardized descriptions currently exist in the literature. The large proportion of those bleedings found in our study might merit efforts to establish a standardized definition. Furthermore, a large proportion of the observed bleedings met the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis criteria for CRNMB or MB, which underlines that those events are highly relevant in the clinical setting.

Currently, limited data are available regarding risk factors for future bleeding specifically in patients with cancer. Of those, risk factors were mostly evaluated in patients receiving therapeutic anticoagulation. Previously reported factors associated with higher bleeding risks include higher age, recent bleeding or anemia, liver dysfunction, kidney disease/failure, severe thrombocytopenia, metastatic/advanced cancer, genitourinary or upper GI cancer, poor performance status, nonresected luminal GI cancer, and presence of intracranial lesions.19-22 To assess risk factors associated with the baseline bleeding risk in patients with cancer, we analyzed those in patients without anticoagulation. In our study, these factors were only partly confirmed in the evaluated subgroup. In detail, metastatic disease was not associated with bleeding risk in our study, contrasting with previous reports.19 This might be explainable by several factors, including the fact that we included disproportionally more patients with higher bleeding risk cancer types that are mostly nonmetastatic in our study. In detail, patients with head and neck cancer receiving no anticoagulation were at an increased bleeding risk in our cohort. These patients often present with locally advanced disease and not metastatic disease when initiating systemic anticancer therapy, which puts them at risk for, for example, tumor bleedings. Their high risk could also be influenced by unmeasured confounders such as, for example, alcohol and smoking exposure. Secondly, the association between higher bleeding risk and metastatic disease was observed in anticoagulation studies, whereas our risk factor exploration was done in the group without anticoagulation. Furthermore, patients with luminal GI cancer were reported as a high-risk population for bleeding events with direct oral anticoagulants therapy.23 However, in our study the presence of luminal GI cancer was not associated with an increased CRB risk in patients without anticoagulation, indicating no increase in baseline bleeding risk in these patients. In this particular patient group, a more cautious approach to dosage, duration, and prescription of anticoagulation might be applied, driven by a perceived heightened risk of bleeding.5,6

Furthermore, neither anticoagulation nor antiplatelet therapy nor platelet counts were significantly associated with bleeding risk in our cohort. This might be attributable to the selective administration of anticoagulation or antiplatelet therapy to patients deemed to have a low bleeding risk from a clinician’s perspective. Moreover, we observed a high baseline bleeding risk in the group without anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy, and the group of patients with those therapies was rather small, which resulted in considerable uncertainty of estimates.

In patients with cancer, risk of thrombotic events has to be carefully balanced against concomitant bleeding risk. Regarding anticoagulation therapy for cancer-associated thrombosis, guidelines recommend that physicians discuss the duration of anticoagulation treatment in patients with cancer after 6 months.5,6 Robust scores for assessing risk of recurrent VTE and bleeding in patients with cancer would aid in clinical decision-making. Previously established bleeding scores were shown to perform poorly in patients with cancer receiving anticoagulation.12 Recently, 2 new bleeding risk scores were presented for this cancer subpopulation.12,24 Although this is a very promising approach as 1 of the risk scores was derived in a noncontrolled cohort,24 an external validation and a thorough assessment of their predictive utility has not been done yet.

Although primary thromboprophylaxis based on VTE-risk stratification using a validated risk model is recommended,5,25 no corresponding tools to stratify bleeding risk in patients with cancer without anticoagulation is currently available, which significantly hampers a balanced risk-benefit evaluation. We found low hemoglobin and low albumin as potential biomarkers for future bleeding risk. Low hemoglobin was previously described as a risk factor for bleeding events in patients with cancer,26,27 whereas albumin was not reported to be associated with an increased risk so far. Hemoglobin and albumin are readily available in nearly all hospitals and are routinely monitored in patients with cancer undergoing anticancer therapies. Thus, these parameters represent promising candidates for the development of specific bleeding risk prediction models, particularly given that their combination yielded an enhanced stratification of risk groups.

Lastly, we observed a higher risk of mortality in patients with bleeding events. In a meta-analysis, the case-fatality rate of MB during anticoagulation was 8.9%.13 We observed 7 (2.3%) fatal bleedings in our study, of which 6 (1.9%) occurred in patients receiving no anticoagulation. The number of deaths in our cohort that were related to hemorrhage might be underestimated, because we only defined bleedings as fatal if the event led to death immediately or shortly after hospitalization (according to the definition of clinical severity 4).28 In the future, greater recognition is necessary to better understand hemorrhage-related deaths in patients with cancer. In comparison, in the placebo groups of the trials evaluating primary thromboprophylaxis in patients with cancer, only 1 study reported 4 fatal bleeding (of 1604 patients, 0.02%).29 Strikingly, the occurrence of a CRB event was associated with poor overall survival in our study, irrespective of immediate bleeding-related mortality. Recently, increased mortality rates after MB or CRNMB were reported in patients with cancer receiving anticoagulation therapy.30 Although the aforementioned study found HRs of 1.4 (CRNMB) and 1.8 (MB) for an increased mortality risk, we observed an even higher impact (THR of 5.80). This emphasizes that these events signify patients who are at high risk for a dismal course of disease.

Our study has several limitations that merit consideration. First, our cohort included patients with and without anticoagulation. The cohort of patients on anticoagulation was relatively small, resulting in considerable uncertainty of estimates and limiting the generalizability of our findings. Moreover, we cannot provide detailed data on prophylactic anticoagulation because VTE risk assessment and primary thromboprophylaxis are not established at our center. However, this enabled us to investigate the true baseline bleeding risk of patients with cancer. Secondly, our study cohort comprised only patients scheduled to initiate systemic antineoplastic therapies from a single center, thereby restricting the broader applicability of our findings to other groups of patients with cancer, such as those exclusively undergoing cancer surgery, radiation therapy, or oral therapy, or patients too frail to receive systemic therapy. Additionally, the majority of subgroup sizes for various cancer types were relatively modest, thereby limiting the ability to make definitive conclusions about subgroups. Especially, the number of patients with hematologic malignancies was low and, therefore, our findings cannot be directly extrapolated to this patient population. Furthermore, longitudinal data on concomitant medications including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or corticosteroids were not available and therefore no dedicated analysis toward their impact on bleeding risk was conducted. Lastly, our risk factor analysis was explorative and does not provide evidence whether they are causally contributing or surrogate markers reflecting patients who are sicker. Future studies should evaluate the independent predictive ability of the proposed risk factors because they are readily available laboratory parameters in clinical routine.

In conclusion, we observed a high risk of bleeding events in patients with cancer. Several putative risk factors for bleeding events in patients without anticoagulation were identified, including a diagnosis of head and neck cancer, and decreased hemoglobin or albumin. Furthermore, CRB events were associated with a considerable increase in short- and long-term mortality.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Lisbeth Eischer and Oliver Königsbrügge for their support in adjudicating the bleeding events. The authors are also grateful to Julia Berger, Lynn Gottmann, Josef Fürst, Martin Korpan, and Markus Kleinberger for helping enroll patients in CAT-BLED.

This project was supported by the City of Vienna Fund for Innovative Interdisciplinary Cancer Research (awarded to C.E.) and by the Society of Thrombosis and Hemostasis (Gesellschaft für Thrombose- und Hämostaseforschung) early career research grant 2021 (awarded to F.M).

Authorship

Contribution: C.E., F.M., and C.A. were responsible for study conceptualization; C.E., F.M., and D.S. were responsible for data curation and formal analysis; C.E., F.M., I.P., and C.A. were responsible for funding acquisition; C.E., F.M., D.S., and A.M.S. performed investigation; C.E., F.M., D.S., and C.A. were responsible for study methodology; A.S.B., M.P., I.P., and C.A. were responsible for project administration; A.S.B., M.P., I.P., and C.A. provided resources; C.E., F.M., and D.S. were responsible for software; A.S.B., M.P., I.P., and C.A. supervised the study; A.S.B., M.P., I.P., and C.A. were responsible for study validation; C.E. was responsible for data visualization; and all authors contributed to writing the original draft manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: F.M. has received travel/congress support from Novartis and honoraria for advisory boards from Servier and Bristol Myers Squibb. A.M.S. has received honoraria for lectures from AstraZeneca, and travel support from PharmaMar, Merck Sharp & Dohme Ges.mbH, and Lilly. A.S.B. has research support from Daiichi Sankyo and Roche; received honoraria for lectures, consultation, or advisory board participation from Roche, Bristol Meyers Squibb, Merck, Daiichi Sankyo, AstraZeneca, CeCaVa, and Seagen;and received travel support from Roche, Amgen, and AbbVie. M.P. has received honoraria for lectures, consultation, or advisory board participation from the following for-profit companies: Bayer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Novartis, Gerson Lehrman Group, CMC Contrast, GlaxoSmithKline, Mundipharma, Roche, BMJ Journals, MedMedia, AstraZeneca, AbbVie, Lilly, Medahead, Daiichi Sankyo, Sanofi, Merck Sharp and Dome, Tocagen, Adastra, Gan and Lee Pharmaceuticals, Janssen, Servier, Miltenyi, Böhringer-Ingelheim, Telix, and Medscape. C.A. has received personal fees for lectures and/or participation in advisory boards from Bayer, Daiichi-Sankyo, Bristol Myers Squibb/Pfizer alliance, and Sanofi. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Cihan Ay, Division of Hematology and Hemostaseology, Department of Medicine I, Medical University of Vienna, Waehringer Guertel 18-20, A-1090 Vienna, Austria; email: cihan.ay@meduniwien.ac.at.

References

Author notes

Data are available on request from the corresponding author, Cihan Ay (cihan.ay@meduniwien.ac.at).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal