Key Points

Pre-HSCT emapalumab is associated with improved long-term donor chimerism and IFS in pediatric patients with HLH.

Emapalumab has the greatest impact on donor chimerism in children aged <12 months undergoing HSCT.

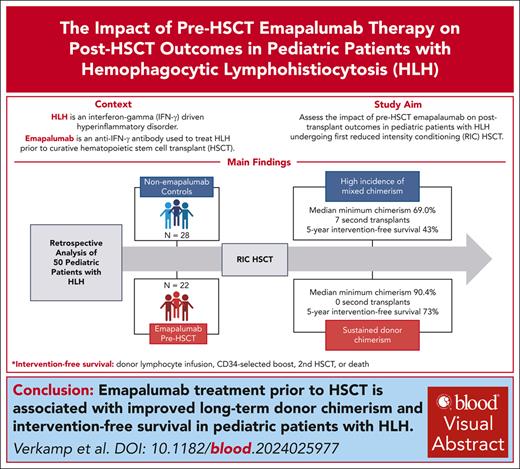

Visual Abstract

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a hyperinflammatory disorder driven by interferon gamma (IFN-γ). Emapalumab, an anti–IFN-γ antibody, is approved for the treatment of patients with primary HLH. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is required for curing HLH. Reduced-intensity conditioning (RIC) HSCT is associated with improved survival but higher incidences of mixed chimerism and secondary graft failure. To understand the potential impact of emapalumab on post-HSCT outcomes, we conducted a retrospective study of pediatric patients with HLH receiving a first RIC-HSCT at our institution between 2014 and 2022 after treatment for HLH, with or without this agent. Mixed chimerism was defined as <95% donor chimerism and severe mixed chimerism as <25% donor chimerism. Intervention-free survival (IFS) included donor lymphocyte infusion, infusion of donor CD34-selected cells, second HSCT, or death within 5 years after HSCT. Fifty patients met the inclusion criteria; 22 received emapalumab within 21 days before the conditioning regimen, and 28 did not. The use of emapalumab was associated with a markedly lower incidence of mixed chimerism (48% vs 77%; P = .03) and severe mixed chimerism (5% vs 38%; P < .01). IFS was significantly higher in patients receiving emapalumab (73% vs 43%; P = .03). Improved IFS was even more striking in infants aged <12 months, a group at the highest risk for mixed chimerism (75% vs 20%; P < .01). Although overall survival was higher with emapalumab, this difference was not significant (82% vs 71%; P = .39). We show that the use of emapalumab for HLH before HSCT mitigates the risk of mixed chimerism and graft failure after RIC-HSCT.

Introduction

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a life-threatening disorder of pathologic immune activation.1 In primary (familial) HLH, defects in cytotoxic function of natural killer and CD8+ T cells lead to uncontrolled T-cell activation and proliferation, along with excessive production of inflammatory cytokines, namely interferon gamma (IFN-γ).1-3 The crucial role of IFN-γ in the pathogenesis of HLH makes it an ideal target for therapeutic intervention.2,4 Emapalumab, an anti–IFN-γ human monoclonal antibody, demonstrated success in an international trial for the treatment of refractory/recurrent familial HLH, leading to its US Food and Drug Administration approval in 2018.5,6 Similar success has been shown in patients with both refractory/recurrent primary7 and secondary HLH.8

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) remains the definitive treatment for primary HLH and select secondary cases. Historically, the use of myeloablative conditioning regimens have been associated with a high rate of transplant-related mortality (overall survival [OS], 45%-66%9-12). Implementation of reduced-intensity conditioning (RIC) regimens has led to improved OS (67%-72%) in most retrospective12-14 and prospective15,16 reports. However, RIC is associated with less-favorable intervention-free survival (IFS; ie, event-free survival; 39%-44%12,15) due to the very high incidence of mixed chimerism (typically defined as donor chimerism <95%17) and secondary graft failure, ranging from 42% to 70% in the aforementioned studies.

Although full donor chimerism is not required to prevent disease, reactivation of HLH is a concern when donor chimerism falls below 20% to 30%.18,19 Interventions for mixed chimerism include rapid wean or discontinuation of immunosuppression (graft-versus-host disease [GVHD] prophylaxis), administration of donor lymphocytes (donor lymphocyte infusion [DLI]), donor CD34-selected cells, and/or second HSCT. Such measures come with inherent risks including GVHD, toxicity of second preparative regimens, and substantial cost. Furthermore, these interventions are not always effective in restoring donor chimerism.20-24

Emapalumab is an important pre-HSCT treatment option for cases of refractory/recurrent HLH. Intriguingly, the pivotal NI-0501-04/05 trials reported a 1-year post-HSCT OS of 90% in 22 patients receiving HSCT. However, a detailed analysis of long-term outcomes after HSCT has not yet been described, nor have the outcomes been compared with those of patients with HLH undergoing HSCT without prior emapalumab therapy. This report provides, to our knowledge, the first detailed description of outcomes after HSCT in patients treated with emapalumab before transplantation, in comparison with nonemapalumab HLH controls at a single center.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective analysis of 50 patients with HLH and EBV-driven related disorders receiving first RIC-HSCT at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center between 1 July 2014 and 31 July 2022. Patients with macrophage activation syndrome (n = 5), history of prior HSCT (n = 7), no prior HLH-directed therapy at any time point before HSCT (n = 3), or those who received an atypical conditioning regimen (n = 1) were excluded (supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood website). Patients receiving emapalumab within 21 days before initiating the preparative regimen for HSCT were compared with a nonemapalumab control group. Data were manually extracted from electronic medical records and are available upon request to the corresponding author. This study was approved by the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Institutional Review Board.

Patients and treatment/transplantation procedures

Patients with pathogenic variants in HLH-associated genes were classified as primary HLH. Patients with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-related disorders without an identified genetic mutation, variants of uncertain significance, and recurrent HLH without an identified trigger are listed separately but were collectively grouped under the category of “other” for statistical analysis (Table 1). Initial HLH therapy with dexamethasone and etoposide (n = 43/50) or dexamethasone alone (n = 7/50) was considered standard therapy. Salvage therapy was defined as the reintensification of etoposide to biweekly or pulses of high-dose corticosteroids after 2 weeks of initial therapy (based on HLH-94 and HLH-2004 protocols25) and/or the use of other novel agents at any time point. Ten included patients were treated on NI-0501-05, 1 on NI-0501-09, and 7 are included in a multi-institutional retrospective review on emapalumab treatment patterns for primary HLH.7

Demographics and transplantation features

| . | No Ema . | Ema . | Total . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (range), mo | 18 (3-204) | 10 (3-214) | 17.5 (3-214) | .42 |

| Underlying cause, n (%) | .44 | |||

| Primary HLH | 23 (82) | 20 (91) | 43 (86) | |

| EBV related | 3 (11) | 2 (9) | 5 (10) | |

| VUS/no identified trigger | 2 (7) | 0 (0) | 2 (4) | |

| HLA match, n (%) | .06 | |||

| MRD | 3 (11) | 4 (19) | 7 (15) | |

| MMRD (haploidentical) | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 1 (2) | |

| MUD | 14 (52) | 10 (48) | 23 (48) | |

| MMUD | 10 (37) | 6 (29) | 16 (33) | |

| 1 allele mismatch | 6 (22) | 3 (14) | 9 (19) | |

| 2 allele mismatches | 4 (15) | 3 (14) | 7 (15) | |

| Conditioning regimen, n (%) | .13 | |||

| Alemtuzumab/Flu/Mel | 25 (89) | 15 (68%) | 40 (80) | |

| Alemtuzumab/Flu/Mel/TT | 2 (7) | 5 (23) | 7 (14) | |

| Alemtuzumab/Flu/Bu | 1 (4) | 1 (5) | 2 (4) | |

| ATG/Flu/Mel/TT | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 1 (2) | |

| Stem cell source, n (%) | .20 | |||

| Bone marrow | 21 (78) | 13 (62) | 34 (71) | |

| Cord blood | 2 (7) | 8 (38) | 10 (21) | |

| PBSC | 4 (15) | 0 (0) | 4 (8) | |

| Graft cell dose, median (IQR) | ||||

| TNC/kg, ×108 | 10 (5.1-12.3) | 10 (4.2-12.2) | 10 (4.5-12.2) | .82 |

| CD34+ cells per kg, ×106 | 8.7 (5.2-11.2) | 10.8 (9.9-15.3) | 9.9 (6.3-13.4) | .02 |

| GVHD prophylaxis, n (%) | ||||

| CSA/Pred | 18 (67) | 10 (48) | 28 (58) | |

| CSA/MMF | 2 (7) | 3 (11) | 5 (10) | |

| Tacro/Pred | 2 (7) | 0 (0) | 2 (4) | |

| Tacro/MMF | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 1 (2) | |

| T-cell–depleted graft | 4 (15) | 5 (24) | 9 (19) | |

| Other | 1 (4) | 2 (10) | 3 (6) |

| . | No Ema . | Ema . | Total . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (range), mo | 18 (3-204) | 10 (3-214) | 17.5 (3-214) | .42 |

| Underlying cause, n (%) | .44 | |||

| Primary HLH | 23 (82) | 20 (91) | 43 (86) | |

| EBV related | 3 (11) | 2 (9) | 5 (10) | |

| VUS/no identified trigger | 2 (7) | 0 (0) | 2 (4) | |

| HLA match, n (%) | .06 | |||

| MRD | 3 (11) | 4 (19) | 7 (15) | |

| MMRD (haploidentical) | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 1 (2) | |

| MUD | 14 (52) | 10 (48) | 23 (48) | |

| MMUD | 10 (37) | 6 (29) | 16 (33) | |

| 1 allele mismatch | 6 (22) | 3 (14) | 9 (19) | |

| 2 allele mismatches | 4 (15) | 3 (14) | 7 (15) | |

| Conditioning regimen, n (%) | .13 | |||

| Alemtuzumab/Flu/Mel | 25 (89) | 15 (68%) | 40 (80) | |

| Alemtuzumab/Flu/Mel/TT | 2 (7) | 5 (23) | 7 (14) | |

| Alemtuzumab/Flu/Bu | 1 (4) | 1 (5) | 2 (4) | |

| ATG/Flu/Mel/TT | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 1 (2) | |

| Stem cell source, n (%) | .20 | |||

| Bone marrow | 21 (78) | 13 (62) | 34 (71) | |

| Cord blood | 2 (7) | 8 (38) | 10 (21) | |

| PBSC | 4 (15) | 0 (0) | 4 (8) | |

| Graft cell dose, median (IQR) | ||||

| TNC/kg, ×108 | 10 (5.1-12.3) | 10 (4.2-12.2) | 10 (4.5-12.2) | .82 |

| CD34+ cells per kg, ×106 | 8.7 (5.2-11.2) | 10.8 (9.9-15.3) | 9.9 (6.3-13.4) | .02 |

| GVHD prophylaxis, n (%) | ||||

| CSA/Pred | 18 (67) | 10 (48) | 28 (58) | |

| CSA/MMF | 2 (7) | 3 (11) | 5 (10) | |

| Tacro/Pred | 2 (7) | 0 (0) | 2 (4) | |

| Tacro/MMF | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 1 (2) | |

| T-cell–depleted graft | 4 (15) | 5 (24) | 9 (19) | |

| Other | 1 (4) | 2 (10) | 3 (6) |

Continuous variables were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical variables with 2 different parameters were compared using the Fisher exact test and variables with >2 groups with the Kruskal-Wallis test. For statistical analysis, underlying cause was categorized as primary HLH vs other, HLA match by matched vs mismatched, and conditioning regimen as 3 different groups (alemtuzumab/flu/mel vs alemtuzumab/flu/mel/TT vs other). Due to the large variability in GVHD prophylaxis, comparison between groups was not feasible. The total N for each analysis varied by parameter due to the 2 deaths during the preparative regimen.

Boldface type signifies statistical significance (P < .05).

Bu, busulfan; CSA, cyclosporine; Ema, emapalumab; Flu, fludarabine; Mel, melphalan; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; MMRD, mismatched related donor; MMUD, mismatched unrelated donor; MRD, matched related donor; MUD, matched unrelated donor; PBSCs, peripheral blood stem cells; Pred, prednisone; TNCs, total nucleated cells; TT, thiotepa; VUS, variant of unclear significance.

Conditioning regimens and graft source varied among patients but were similarly distributed between the groups. Donor HLA match was categorized as matched related donor, mismatched related donor, matched unrelated donor, and mismatched unrelated donor with 1 or 2 allele mismatches; but for analysis, they were compared in 2 groups (matched vs mismatched). Patients received GVHD prophylaxis and additional supportive care according to institutional standards (Table 1).

All patients were prospectively screened and risk stratified for transplant-associated thrombotic microangiopathy (TA-TMA) as part of our standard practice.26,27 Patients with high-risk TA-TMA received eculizumab using pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic-guided dosing as first-line therapy.28,29 TA-TMA after second HSCT was included in this analysis, but pre-HSCT TMA was not. Additional recorded complications included veno-occlusive disease, escalation of care to the intensive care unit, use of renal replacement therapy, mechanical ventilation, or vasopressors, and the presence of viremias and/or significant bacterial or fungal infections requiring admission within 1 year after HSCT. Acute and chronic GVHD were diagnosed and graded via consensus criteria.30,31

Data collection

Pre-HSCT HLH status was assessed based on HLH-2004 criteria,10 obtained within 2 weeks before conditioning. Whole-blood chimerism was used for the identification of mixed chimerism. This was assessed weekly during the early transplant period per institutional standards. Chimerism levels were documented at predefined thresholds (<95% and 25%) and time frames (∼6 and 12 months after HSCT, and the last assessment within the study period). Minimum chimerism in specific cell lineages was noted when available. For patients who did not develop mixed chimerism and consequently did not have sorted cell lineages assessed, the minimum whole-blood chimerism was used for sorted cell analyses. Minimum T-cell chimerism was not assessed until after day 100 for patients who received a T-cell–depleted graft. Additional post-HSCT laboratory markers (sCD25 or soluble interleukin-2 receptor and sC5b9) were obtained within 3 days of the specified time points. CXCL9 data were recorded, but comparison between groups was not feasible due to low sample size.

Definitions and outcomes

Neutrophil recovery was defined as the first of 3 consecutive days with an absolute neutrophil count >0.5 × 106/L and platelet recovery as the first of 3 consecutive days >20 × 106/L without transfusion. Primary graft failure was defined as the failure to achieve neutrophil recovery and/or donor chimerism <5% within 35 days after HSCT. Mixed chimerism was defined as whole-blood donor chimerism <95% on 2 consecutive occasions. Severe mixed chimerism was defined as donor chimerism <25% at any time point. Interventions for mixed chimerism were performed at the providing physician’s discretion and included rapid/premature discontinuation of immunosuppression, DLI, infusion of donor CD34-selected cells (CD34-selected boost), and second HSCT (including a preparative regimen).

IFS was the primary outcome and was defined as the administration of any cellular product(s) for mixed chimerism (DLI, CD34-selected boost, or second HSCT) in alignment with prior publications.12,15,32,33 High-risk IFS was defined as the rapid weaning/discontinuation of immunosuppression, DLI, and/or second HSCT as a secondary outcome, given the known risk of subsequent GVHD or other significant complications with these measures.20-23 The use of virus-specific T cells was recorded but not considered an intervention. Outcomes were recorded up to 5 years after HSCT or until last follow-up if HSCT occurred <5 years before this analysis. When applicable, chimerism data were truncated at the time of second HSCT.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using PRISM version 10.1.1 and Python version 0.28.0. Continuous variables were summarized with median and interquartile range (IQR) and compared using the Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical variables, presented as n (%), were compared using the Fisher Exact or Kruskal-Wallis tests.34,35 Kaplan-Meier curves were generated and compared using the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. Cumulative incidence curves included death as a competing event. Cox proportional hazard model was used for univariate and multivariate analysis.36 A P value of <.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patients and treatment/transplantation features

Fifty patients met the inclusion criteria; 22 (44%) received emapalumab within 21 days before conditioning, and 28 patients (56%) were identified for the nonemapalumab control group. Due to early deaths during the conditioning regimen or within 14 days after HSCT, 3 patients (1 receiving emapalumab and 2 nonemapalumab) were not assessable for chimerism but were included in survival analyses (supplemental Figure 1). One patient in the nonemapalumab cohort received emapalumab >150 days before HSCT.

The first patient who underwent HSCT after receiving emapalumab therapy underwent transplant in 2015; therefore, we selected 2014 as a cutoff for inclusion to account for variations in routine transplant care. As expected, the frequency of emapalumab use increased with time (supplemental Figure 2A). To address the potential confounder that general improvements in HSCT practice over time could contribute to better outcomes in later transplants, mortality rates were analyzed relative to the time of HSCT, irrespective of emapalumab use. This analysis revealed no significant year-by-year variation in mortality rates (supplemental Figure 2B), and the year of transplant was not significant in a multivariate analysis (described below), suggesting that the improvements observed in the emapalumab cohort were not merely due to advances in care over time.

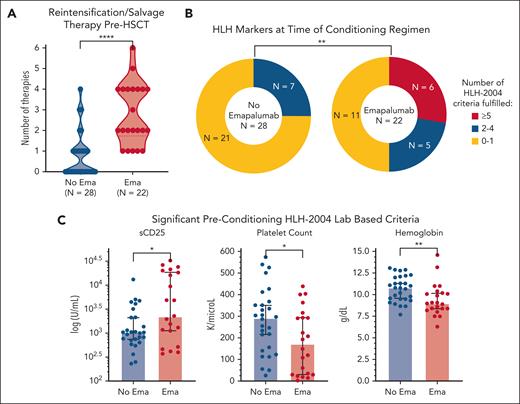

Before HSCT, the emapalumab cohort had more refractory and more active HLH as evidenced by a higher number of salvage therapies and fulfillment of more HLH-2004 criteria within 2 weeks before initiating the preparative regimen (Figure 1). Notably, these factors are often associated with worse outcome after HSCT,10,14,37,38 which could dampen the measured impact of emapalumab in subsequent analyses. Patients received a median of 12.5 total doses of emapalumab (range, 1-34). The first dose was given at a median of 55.5 days before HSCT (range, day –174 to day –1) and the last dose at a median of 16.5 days before HSCT (range, day –28 to day –1). Most patients (20/22 [91%]) received at least 1 dose within 21 days of stem cell infusion, with a median of 2 doses (range, 0-5) and a median cumulative dosing of 7 mg/kg (range, 0-47) during this interval (supplemental Figure 4).

HLH was more refractory and more active at the time of HSCT in patients receiving emapalumab. (A) The number of salvage therapies used before HSCT, including emapalumab as a salvage agent. Use of salvage therapy was significantly higher in the emapalumab cohort (P < .0001). A persistent but less striking difference was noted when emapalumab was not included as a salvage agent (P = .0059). (B) Number of HLH-2004 criteria met including recent imaging with splenomegaly and laboratory-based criteria obtained within 2 weeks before starting the preparative regimen. (C) Significant preconditioning laboratory markers. Salvage therapies were treated as continuous variables based on the number of agents used. Individual laboratory markers were also treated as continuous variables and both analyses were performed with the Mann-Whitney U test. Total HLH-2004 criteria met was grouped as those meeting 0 to 4 criteria vs ≥5 criteria and compared via the Fisher exact test. Additional details on salvage therapies, sCD25 trends, and nonsignificant HLH-2004 markers are shown in supplemental Figure 3. ∗∗∗∗P < .0001; ∗∗P < .01; ∗P < .05.

HLH was more refractory and more active at the time of HSCT in patients receiving emapalumab. (A) The number of salvage therapies used before HSCT, including emapalumab as a salvage agent. Use of salvage therapy was significantly higher in the emapalumab cohort (P < .0001). A persistent but less striking difference was noted when emapalumab was not included as a salvage agent (P = .0059). (B) Number of HLH-2004 criteria met including recent imaging with splenomegaly and laboratory-based criteria obtained within 2 weeks before starting the preparative regimen. (C) Significant preconditioning laboratory markers. Salvage therapies were treated as continuous variables based on the number of agents used. Individual laboratory markers were also treated as continuous variables and both analyses were performed with the Mann-Whitney U test. Total HLH-2004 criteria met was grouped as those meeting 0 to 4 criteria vs ≥5 criteria and compared via the Fisher exact test. Additional details on salvage therapies, sCD25 trends, and nonsignificant HLH-2004 markers are shown in supplemental Figure 3. ∗∗∗∗P < .0001; ∗∗P < .01; ∗P < .05.

After emapalumab, the most common salvage therapy was alemtuzumab (n = 13; 6 emapalumab and 7 nonemapalumab). Seven patients (5 emapalumab and 2 nonemapalumab) received this as additional dosing during the preparative regimen. Given the known risk of increased mixed chimerism with higher peritransplant alemtuzumab levels,39,40 we evaluated cumulative alemtuzumab dose and absolute lymphocyte counts, which were similar between the groups (supplemental Figure 5A-B).

Forty-eight patients (96%) received melphalan-based RIC, and 2 (4%) received reduced toxicity with targeted busulfan-based conditioning (1 emapalumab and 1 nonemapalumab). Alemtuzumab, fludarabine, and melphalan was the most common preparative regimen for both groups (n = 47 [94%]), including 7 patients (14%) who received this regimen with the addition of thiotepa. Across both groups, most patients (44/47 [94%]) received an intermediate (14 day) alemtuzumab dosing regimen, similar to prior publications.15,41 Transplantation features were overall similar between groups (P > .05) and are described in Table 1. Cell dose by total nucleated cells and CD3+ per kilogram (excluding T-cell–depleted grafts) were similar, but the dose by CD34 per kilogram was significantly different (nonemapalumab median, 8.7 × 106/kg [IQR, 5.2-11.2]; emapalumab median, 10.8 × 106/kg [IQR, 9.9-15.3]; P = .02). This was in part due to 2 outliers who received 73.5 × 106/kg and 69.6 × 106/kg in the emapalumab cohort. When cell dose was analyzed irrespective of emapalumab use, there was no association with chimerism (supplemental Figure 6), nor was this significant in a multivariate analysis (described below). Time to count recovery and length of admission from time of transplant was similar between the groups (supplemental Figure 5C-D). No patients experienced primary graft failure.

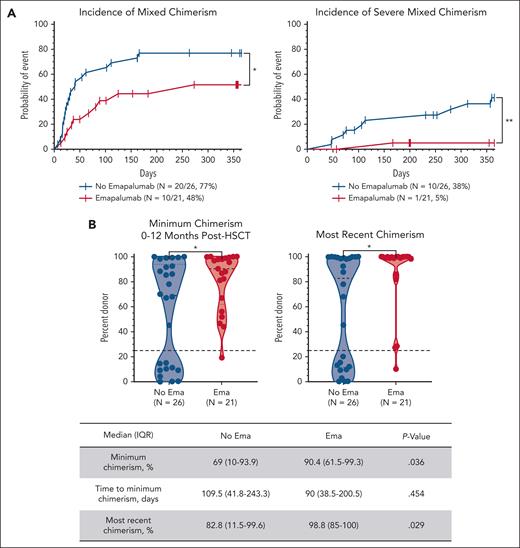

Mixed chimerism and related interventions

Forty-seven patients (94%) were assessable for chimerism. Mixed chimerism (whole-blood donor chimerism <95% on 2 consecutive occasions) occurred in 30 patients (60%). The incidence of mixed chimerism was significantly higher in the nonemapalumab cohort (20/26 [77%]) than the emapalumab cohort (10/21 [48%]; P = .03). More importantly, only 1 emapalumab patient (5%) developed severe mixed chimerism (donor chimerism <25%) compared with 10 nonemapalumab patients (38%; P = .007; Figure 2A). The minimum donor chimerism within 1 year after HSCT was significantly lower in nonemapalumab patients (median, 69% [IQR, 10%-93.9%] vs emapalumab 90.4% [IQR, 61.5-99.3]; P = .04; Figure 2B). The time to minimum chimerism was similar between the groups (P = .45). The lowest T-cell chimerism was significantly different between the groups (median nonemapalumab, 79.0% [IQR, 18.3%-99%] vs emapalumab, 97.7% [IQR, 81.4%-99.7%]; P = .045). Other lineage-specific minimum chimerism levels were similar (supplemental Figure 7A). Despite multiple interventions targeting falling chimerism (described below), nonemapalumab patients continued to have significantly lower donor chimerism at the end of the study period (median, 82.8% [IQR, 11.5%-99.6%] vs emapalumab, 98.8% [IQR 85%-100%]; P = .03; Figure 2B).

Pre-HSCT emapalumab is associated with higher donor chimerism. (A) Cumulative incidence of mixed chimerism (donor chimerism <95% on 2 consecutive occasions) and severe mixed chimerism (donor chimerism <25%). (B) Minimum donor chimerism obtained within 1 year after HSCT and most recent donor chimerism within the study period (up to 5 years after HSCT, truncated at the time of second HSCT or death when applicable). Cumulative incidence was compared via the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test with death included as a competing risk. Chimerism levels were treated as continuous variables and compared via the Mann-Whitney U test. ∗∗P < .01; ∗P < .05.

Pre-HSCT emapalumab is associated with higher donor chimerism. (A) Cumulative incidence of mixed chimerism (donor chimerism <95% on 2 consecutive occasions) and severe mixed chimerism (donor chimerism <25%). (B) Minimum donor chimerism obtained within 1 year after HSCT and most recent donor chimerism within the study period (up to 5 years after HSCT, truncated at the time of second HSCT or death when applicable). Cumulative incidence was compared via the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test with death included as a competing risk. Chimerism levels were treated as continuous variables and compared via the Mann-Whitney U test. ∗∗P < .01; ∗P < .05.

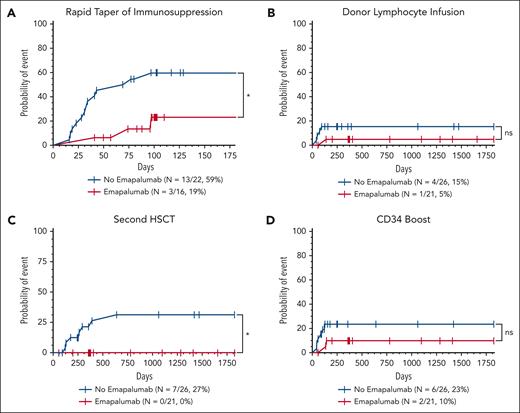

Intervention for mixed chimerism occurred at least once in 19 patients (40%; 15 nonemapalumab and 4 emapalumab). Rapid taper of immunosuppression was the most frequent intervention and was more frequent in the nonemapalumab cohort. A second HSCT was performed in 7 nonemapalumab patients (27%) and 0 emapalumab patients within the study period (P = .01; Figure 3).

Patients who received emapalumab before HSCT required less interventions for mixed chimerism after HSCT. Cumulative incidence of interventions performed for mixed chimerism included rapid taper of immunosuppression (cyclosporine or tacrolimus) (A), DLI (B), CD34-selected boost (C), and second HSCT (D). Death was included as a completing risk; incidence was analyzed using the Mantel-Cox or log-rank test. ∗P < .05. ns, not statistically significant.

Patients who received emapalumab before HSCT required less interventions for mixed chimerism after HSCT. Cumulative incidence of interventions performed for mixed chimerism included rapid taper of immunosuppression (cyclosporine or tacrolimus) (A), DLI (B), CD34-selected boost (C), and second HSCT (D). Death was included as a completing risk; incidence was analyzed using the Mantel-Cox or log-rank test. ∗P < .05. ns, not statistically significant.

OS and IFS

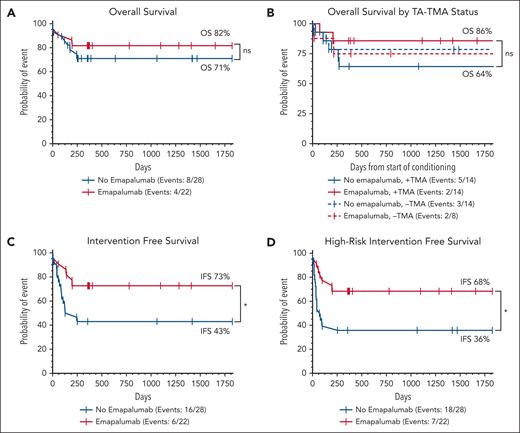

Twelve patients (24%; 8 nonemapalumab and 4 emapalumab) died at a median of 139 days after HSCT (IQR, 24-200). There was a numeric but not statistically significant improvement in 5-year OS (emapalumab OS, 82% [95% confidence interval (CI), 59-93] vs nonemapalumab OS, 71% [95% CI, 51-84]; P = .41; Figure 4A). Of the 8 nonemapalumab deaths, 2 early deaths were related to active HLH, and 2 occurred shortly after undergoing second HSCT for severe mixed chimerism. None of the 4 emapalumab deaths were related to active HLH, and none of these patients had mixed chimerism. Further characterization of post-HSCT mortality is provided in supplemental Table 1. IFS (use of any cellular product or death) and high-risk IFS (rapid taper of immunosuppression, DLI, second HSCT, or death) were both significantly higher in patients receiving emapalumab before HSCT. Five-year IFS was 73% (95% CI, 49-85) in emapalumab vs 43% (95% CI, 25-60; P = .03) in nonemapalumab patients, and 5-year high-risk IFS was 68% (95% CI, 45-83) in emapalumab vs 36% (95% CI, 19-53; P = .01; Figure 4C-D) in nonemapalumab patients.

Pre-HSCT emapalumab is associated with improved IFS and high-risk IFS. Five-year Kaplan-Meier survival estimates based on OS (A), TA-TMA status (moderate and high risk only) (B), IFS (use of any additional cellular product for low chimerism, or death) (C), and high-risk IFS (rapid taper of immunosuppression, DLI, second HSCT, or death) (D). Time for the TA-TMA survival analysis was recorded from the start of conditioning, but for all other analyses, time is relative to the day of stem cell infusion (day 0). Curves were compared using the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. Similar curves for GVHD free survival are shown in supplemental Figure 11. ∗P < .05. ns, not statistically significant.

Pre-HSCT emapalumab is associated with improved IFS and high-risk IFS. Five-year Kaplan-Meier survival estimates based on OS (A), TA-TMA status (moderate and high risk only) (B), IFS (use of any additional cellular product for low chimerism, or death) (C), and high-risk IFS (rapid taper of immunosuppression, DLI, second HSCT, or death) (D). Time for the TA-TMA survival analysis was recorded from the start of conditioning, but for all other analyses, time is relative to the day of stem cell infusion (day 0). Curves were compared using the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. Similar curves for GVHD free survival are shown in supplemental Figure 11. ∗P < .05. ns, not statistically significant.

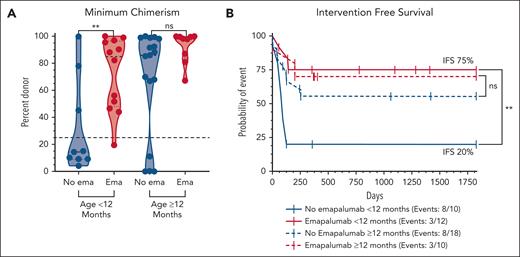

Age and mixed chimerism

Recognizing the higher rate of mixed chimerism in infants after RIC-HSCT regardless of diagnosis,32,42 we next looked at the incidence of mixed chimerism and related outcomes stratified by age above (n = 28; 18 nonemapalumab and 10 emapalumab) and below 12 months (n = 22, 10 nonemapalumab and 12 emapalumab; Figure 5). Remarkably, emapalumab before HSCT appeared to mitigate this risk because the difference in chimerism was even more pronounced in this age group, evidenced by a median minimum chimerism of 14% (IQR, 9%-62%) in nonemapalumab infants vs 85% (IQR, 48%-97%) in emapalumab infants (P = .01; Figure 5A). IFS in nonemapalumab infants was quite poor at 20% (95% CI, 3-47) vs 75% (95% CI, 41-91; P = .003; Figure 5B) in emapalumab infants. The minimum chimerism was not significantly different in patients aged ≥12 months (nonemapalumab median, 86% [IQR, 39%-99%] vs emapalumab median, 98% [IQR, 84%-100%]; P = 8); but at the observed rate of mixed chimerism in these groups, the sample size would need to be at least 2.5 times larger to be adequately powered to detect a difference.43 OS was similar when stratified by age and emapalumab use; however, there was a significant difference in OS between patients aged above and below 12 months when emapalumab use was not accounted for (age <12 months OS, 91% [95% CI, 68-98] vs ≥12 months OS, 64% [95% CI, 43-79]; P = .04; supplemental Figure 8C-D).

Pre-HSCT emapalumab mitigates the risk of mixed chimerism associated with young age at the time of transplantation. (A) Minimum donor chimerism obtained within 1 year after HSCT stratified by age at the time of HSCT. (B) Five-year Kaplan-Meier survival estimates based on IFS (use of any cellular product or death). Chimerism levels were treated as continuous variables and compared via the Mann-Whitney U test. Survival curves were compared using the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. An XY plot by age and mixed chimerism and similar survival curves based on high-risk IFS and OS are shown in supplemental Figure 8. ∗∗P < .01. ns, not statistically significant.

Pre-HSCT emapalumab mitigates the risk of mixed chimerism associated with young age at the time of transplantation. (A) Minimum donor chimerism obtained within 1 year after HSCT stratified by age at the time of HSCT. (B) Five-year Kaplan-Meier survival estimates based on IFS (use of any cellular product or death). Chimerism levels were treated as continuous variables and compared via the Mann-Whitney U test. Survival curves were compared using the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. An XY plot by age and mixed chimerism and similar survival curves based on high-risk IFS and OS are shown in supplemental Figure 8. ∗∗P < .01. ns, not statistically significant.

Post-HSCT complications

The incidence of clinically significant (high-risk and moderate-risk) TA-TMA was high in both cohorts (nonemapalumab, 14/28 [50%]; emapalumab, 14/22 [64%]; P = .11; supplemental Figure 9). Emapalumab patients had the highest rate of high-risk TA-TMA but appeared to be more responsive to complement blockade. The 2 emapalumab patients with TA-TMA who died were both controlled on weekly eculizumab at the time of their death. Of the 5 nonemapalumab patients with TA-TMA who died, 3 died within 1 week of starting eculizumab and 1 with uncontrolled TA-TMA before eculizumab was started. OS was highest in emapalumab patients with TA-TMA (86% [95% CI, 54-96]) compared with an OS of 64% (95% CI, 34-83; P = .21) in nonemapalumab patients with TA-TMA, and the survival between patients without TA-TMA was nearly identical (emapalumab OS, 75%; 95% CI, 32-93; nonemapalumab OS, 79%; 95% CI, 47-92; P = .89; Figure 4B).

There was a similar incidence of the need for escalation of care to the pediatric intensive care unit, use of renal replacement therapy, mechanical ventilation, and vasopressors, which were used as surrogates of organ injury. Most patients with these complications also had a diagnosis of TA-TMA. Rates of infections were similar between the groups (supplemental Figure 10). Only 1 patient (emapalumab) developed veno-occlusive disease after busulfan-based conditioning, which resolved with defibrotide. Incidence of GVHD and GVHD-free survival were similar between the groups (supplemental Figure 11).

Potential confounders and multivariate analysis

Tocilizumab was given during the preparative regimen for some patients per their primary provider’s discretion. This occurred more frequently in the emapalumab cohort. When IFS was analyzed by tocilizumab use alone, there was no significant difference between groups (supplemental Figure 12A-B). The use of thiotepa and/or T-cell–depleted grafts occurred at a similar frequency between groups and had no clear effect on IFS (supplemental Figure 12C-F). OS was similar between groups for all 3 of these parameters.

A univariate and multivariate Cox analysis confirmed the significant impact of emapalumab before HSCT on IFS. Emapalumab use was the only significant parameter in the univariate analysis and remained significant in the multivariate analysis with a hazard ratio of 0.36 (P = .03; Table 2). For OS, age was the only significant parameter in the univariate and multivariate analysis, but the effect was small (hazard ratio, 1.001). Nonsignificant parameters included year of transplant, underlying cause (primary vs other), cumulative alemtuzumab dose, thiotepa, T-cell–depleted grafts, HLA match, total nucleated cells per kg, CD34 count per kg, and TA-TMA.

Emapalumab is the strongest predictor of IFS in a multivariate analysis

| Covariates . | IFS . | OS . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate . | Multivariate . | Univariate . | Multivariate . | |||||

| Hazard ratio . | P value . | Hazard ratio . | P value . | Hazard ratio . | P value . | Hazard ratio . | P value . | |

| Age, mo | 1.00 | .612 | NA | NA | 1.01 | .005 | 1.01 | .005 |

| Emapalumab, Y/N | 0.36 | .034 | 0.36 | .034 | 0.594 | .399 | NA | NA |

| Covariates . | IFS . | OS . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate . | Multivariate . | Univariate . | Multivariate . | |||||

| Hazard ratio . | P value . | Hazard ratio . | P value . | Hazard ratio . | P value . | Hazard ratio . | P value . | |

| Age, mo | 1.00 | .612 | NA | NA | 1.01 | .005 | 1.01 | .005 |

| Emapalumab, Y/N | 0.36 | .034 | 0.36 | .034 | 0.594 | .399 | NA | NA |

The table shows the significant parameters of the univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazard models assessing the impact of various HSCT features on IFS and OS. IFS included the use of any cellular product for falling chimerism or death. Additional parameters that were analyzed but nonsignificant in either analysis included year of HSCT, underlying cause (primary vs other), cumulative alemtuzumab dose (mg/kg preconditioning, periconditioning, and total exposure), use of tocilizumab during the conditioning regimen, addition of thiotepa, T-cell–depleted grafts, HLA match, TNC/kg, CD34 count per kg, and high-risk or moderate-risk TA-TMA. For the thiotepa analysis, only patients receiving alemtuzumab/fludarabine/melphalan ± thiotepa were included. The Cox proportional hazard model was used for these analyses. Significant results (P < .05) are bolded, and numeric P values are shown in the respective columns. NA indicates that the treatment failed the Cox proportional hazards assumptions with P value <.05 and should be excluded from the analysis, likely related to the small sample size.

NA, not a number (failed the proportional hazards assumption); TNC, total nucleated cells; Y/N, yes/no.

Discussion

We provide, to our knowledge, the first detailed report on post-HSCT outcomes in pediatric patients with HLH treated with emapalumab. This study identifies emapalumab as a significant factor in preventing mixed chimerism and secondary graft failure, a prevalent complication in patients with HLH after HSCT. Of the 21 emapalumab patients assessable for chimerism, the median minimum chimerism within 1 year after HSCT was 90.4% (IQR, 61.5-99.3); only 1 (5%) developed severe mixed chimerism (donor chimerism <25%; Figure 2), and none received a second HSCT (Figure 3). IFS with emapalumab was 73%, which was significantly higher than our nonemapalumab controls (43%; P = .03; Figure 4) and prior publications using RIC regimens.12,15

Emapalumab has been an important advancement in treating refractory HLH and potentially improving pre-HSCT outcomes. This study now demonstrates that pre-HSCT emapalumab use has a substantial positive impact on post-HSCT outcomes. Our findings are particularly notable because the majority of the emapalumab patients in this study represent a high-risk population with highly refractory disease that historically leads to poorer outcomes, especially when disease is active at the time of transplantation.10,14,37,38

It is well established that RIC regimens are typically associated with less upfront toxicities and mortality; however, they pose a significant risk for mixed chimerism (commonly defined as donor chimerism <95%17) and subsequently worsened event-free survival or IFS.12,15,44 Development of mixed chimerism and secondary graft failure (due to substantial loss of donor stem cells after initial engraftment) is reliant on numerous recipient and graft factors, but the precise mechanisms behind their development are not known. IFN-γ has been shown to be detrimental to hematopoietic stem cell engraftment and health45-47 and is likely a significant contributor to the pathophysiology of mixed chimerism. The exposure of donor stem cells to recipient IFN-γ likely creates an inhospitable environment for engraftment, dampening the graft’s ability to outcompete residual recipient stem cells that remain after RIC preparative regimens. The larger difference in T-cell chimerism than other cell lineages in this study could indicate that this process is potentially related to T-cell reconstitution/engraftment (supplemental Figure 7A). The overlap of IFN-γ in the pathogenesis of both HLH and in the engraftment process makes it unsurprising that even when myeloablative conditioning is used for patients with HLH, mixed chimerism occurs in 10% to 50% of long-term survivors.9,10,37,38,48 The findings in this study not only offer a potential mechanism behind the development of mixed chimerism but also provide an intervention aimed at its prevention via IFN-γ blockade.

Paradoxically, Geerlinks et al showed that lower day 14 and day 28 CXCL9 level, a surrogate marker for IFN-γ, was associated with increased risk of secondary graft failure in patients enrolled in the BMT CTN 1204 RICHI study15,39; however, this association was directly coupled with high day 0 alemtuzumab levels (>0.32 μg/mL), which likely causes depletion of donor T cells and therefore lower donor-derived IFN-γ. In our cohort, cumulative alemtuzumab dose (mg/kg preconditioning and periconditioning) and absolute lymphocyte counts throughout conditioning were similar between the groups (supplemental Figure 5A-B). Due to minimal data available, we were unable to meaningfully compare CXCL9 levels or alemtuzumab levels; however, of the 6 emapalumab patients with day 0 (±2 days) alemtuzumab levels available, all but 1 were >0.32 μg/mL, yet only 2 of 6 developed mixed chimerism, and none required intervention for mixed chimerism, further emphasizing the benefit of emapalumab in achieving full donor chimerism.

The difference in outcome by age in this study was striking. Similar to prior studies,32,42 infants had a higher rate of mixed chimerism and associated interventions; however, this risk was substantially mitigated by the use of emapalumab before HSCT, and there was an even more pronounced improvement in chimerism and IFS in this age group (Figure 5). Despite this higher rate of mixed chimerism, OS was excellent at 91% (95% CI, 68-98) for all patients aged <12 months. Alternatively, patients aged ≥12 months had less mixed chimerism but significantly worse OS at 64% (95% CI, 42-78; P = .04), and the use of emapalumab did not seem to influence mortality (supplemental Figure 8C-D). This disparity in survival for older patients has previously been reported20,37,49,50 and highlights the need for investigation into age-based risk factors and strategies to optimize outcomes in noninfants with HLH.

The rate of post-HSCT complications was similar between the groups (supplemental Figures 9-11). Notably, the overall incidence of TA-TMA (56%) was much higher in this study than other pediatric HSCT patients (∼16%-30%26,51,52). This discrepancy likely reflects our previous findings of coactivation of both IFN and complement pathways as a culprit in the evolution of TMA in these patients,53 in whom the blockade with both emapalumab and eculizumab appears beneficial for TMA resolution and survival.54 Our current study suggests pre-HSCT emapalumab may be modifying high-risk TA-TMA’s phenotype. Emapalumab patients with TA-TMA had the highest incidence of high-risk TA-TMA but exhibited better response to complement intervention and had better OS (86%) than nonemapalumab TA-TMA patients (64%) and even higher survival than patients without TA-TMA in either cohort (75% and 79%; Figure 4B). Although sample size limited this analysis, these findings underscore the need for further investigation into the relationship between TMA and HLH pathophysiology and the impact of both emapalumab and eculizumab on TA-TMA.

The generalizability of this study’s findings may be hindered by its single-center design. Its retrospective nature leads to additional limitations. The use of emapalumab and timing relative to transplant largely varied between patients. The half-life for emapalumab ranges from 2.5 to 18.9 days.46,55 All patients received their last dose within at least 18 days from the start of conditioning, and 73% (16/22) received this within at least 18 days from stem cell infusion. There was no apparent association with minimum chimerism level and time from the last emapalumab dose. Interventions during the peritransplant period occurred at varying rates among patients, and the cell dose when measured by CD34 cells per kilogram was higher in the emapalumab group; however, these parameters underperformed in the multivariate analysis and were not associated with chimerism or IFS when analyzed alone (Table 2; supplemental Figures 6 and 12). Notable strengths in this study include the frequent chimerism assessment to identify mixed chimerism earlier in the posttransplant course and the inclusion of rapid/premature discontinuation of immunosuppression as a high-risk intervention, which is often the first intervention when mixed chimerism is identified but is not typically assessable in larger, multicenter studies.

In the first detailed analysis on the impact of emapalumab on post-HSCT outcomes, we show that IFN-γ blockade before HSCT is an important tool in decreasing the risk of mixed chimerism for patients with HLH without identified adverse effects. Given the tolerability and significant improvement in donor chimerism and IFS, we recommend strong consideration of incorporating its use in patients with HLH preparing for HSCT, even if not needed for the control of HLH. Future studies are warranted to investigate optimal dosing and fully delineate the role of IFN-γ and its inhibition in establishing full donor chimerism.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Bone Marrow Transplant Tissue Repository team for outstanding technical assistance and their institutional support for making this study possible. BioRender.com was used to create supplemental Figure 1 and the visual abstract.

This project was supported by the Liam’s Lighthouse Foundation, The Angel Adalida Foundation, and the Evan Easley Memorial Foundation.

Authorship

Contribution: S.J. and M.B.J. initiated the project and its initial design; B.V. collected and analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript with essential input and expertise from other authors; P.K., S.J., and M.B.J. assisted with data analysis; and S.J., A.S., R.M., and M.B.J. edited the paper and provided essential inputs.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: B.V. is a consultant for Sobi. S.J. is a consultant for Omeros, Alexion, and Sobi and holds US patents. A.S. receives research support, including study drug, from Sobi and has an honorarium from Eurofins Viracor. R.M. is employed part-time by Pharming Healthcare Inc. M.B.J. receives research support from and is a consultant for Sobi (no research support from Sobi was used for this study). P.K. declares no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Michael B. Jordan, Immunobiology, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, 3333 Burnet Ave, ML-7038, Cincinnati, OH 45229; email: michael.jordan@cchmc.org.

References

Author notes

Data are available on request from the corresponding author, Michael B. Jordan (michael.jordan@cchmc.org).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal