Key Points

Active metabolic checkpoints respond to AK2 deficiency by decreasing anabolic pathways to maintain nutrient homeostasis and proliferation.

When metabolic checkpoints are ineffective, AK2 deficiency leads to ectopic mTOR activation, nucleotide imbalance, and proliferation arrest.

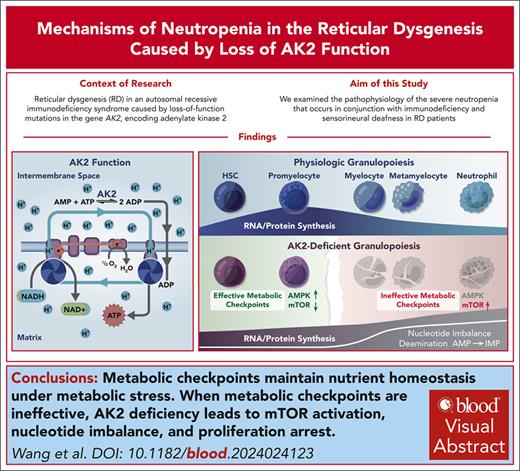

Visual Abstract

Cellular metabolism is highly dynamic during hematopoiesis, yet the regulatory networks that maintain metabolic homeostasis during differentiation are incompletely understood. Herein, we have studied the grave immunodeficiency syndrome reticular dysgenesis caused by loss of mitochondrial adenylate kinase 2 (AK2) function. By coupling single-cell transcriptomics in samples from patients with reticular dysgenesis with a CRISPR model of this disorder in primary human hematopoietic stem cells, we found that the consequences of AK2 deficiency for the hematopoietic system are contingent on the effective engagement of metabolic checkpoints. In hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells, including early granulocyte precursors, AK2 deficiency reduced mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling and anabolic pathway activation. This conserved nutrient homeostasis and maintained cell survival and proliferation. In contrast, during late-stage granulopoiesis, metabolic checkpoints were ineffective, leading to a paradoxical upregulation of mTOR activity and energy-consuming anabolic pathways such as ribonucleoprotein synthesis in AK2-deficient cells. This caused nucleotide imbalance, including highly elevated adenosine monophosphate and inosine monophosphate levels, the depletion of essential substrates such as NAD+ and aspartate, and ultimately resulted in proliferation arrest and demise of the granulocyte lineage. Our findings suggest that even severe metabolic defects can be tolerated with the help of metabolic checkpoints but that the failure of such checkpoints in differentiated cells results in a catastrophic loss of homeostasis.

Introduction

An unresolved question in inborn errors of metabolism is why they lead to severe defects in some cells but not others. One example of this is the primary immunodeficiency syndrome reticular dysgenesis (RD), which presents with severe congenital neutropenia and T-cell lymphopenia, frequently associated with B-cell and natural killer cell lymphopenia,1,2 whereas most hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs), as well as monocytes, are relatively preserved.3 RD is fatal early in life unless hematopoietic reconstitution is achieved by hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) transplantation.4 Compared with other severe combined immunodeficiencies, patients with RD present earlier and with bacterial rather than opportunistic infections, indicating that neutropenia is the primary cause of death.4 Consequently, RD has also been classified as a bone marrow failure syndrome.5 However, unlike typical bone marrow failure syndromes, bone marrow cellularity in RD is often increased rather than decreased, necessitating fully myeloablative transplant regimens for reliable engraftment.4 Therapeutic developments to treat RD with gene therapy/editing have sparked scientific interest but are limited to preclinical studies at this time.6,7

RD is caused by a loss of function in the mitochondrial enzyme adenylate kinase 2 (AK2).1,2 In the largest reported cohort of patients with RD phenotypes to date, deletions, missense, nonsense, and splice-site mutations were detected in AK2.4 Adenylate kinases are a group of at least 9 phosphotransferases that maintain adenine nucleotide homeostasis within defined cellular compartments.8-10 AK2 is localized in the mitochondrial intermembrane space, where it catalyzes the reversible transfer of a phosphate group from adenosine triphosphate (ATP) to adenosine monophosphate (AMP), yielding adenosine diphosphate (ADP) (AMP + ATP 2 ADP). ADP is actively transported to the mitochondrial matrix, where it is phosphorylated to ATP. AK2 is ubiquitously expressed, whereas the expression of its cytosolic counterpart, adenylate kinase 1 (AK1), is restricted to certain tissue and cell types.2 Because relative substrate concentrations in the intermembrane space and cytosol are typically reversed, AK2 and AK1 catalyze the same reaction in opposite directions.8

Although AK2 is ubiquitously expressed, nonhematopoietic tissues, except for a subset of inner ear cells, seem unperturbed by AK2 deficiency.1,2 This suggests that in most cells, AK2 function is dispensable. Notably, AK1 is not expressed in most hematopoietic cells. Therefore, the question has been raised if AK1 expression compensates for the lack of AK2 in nonhematopoietic cells, and if lack of AK1 expression by hematopoietic cells may explain the hematopoietic phenotype in RD.1,2,11,12 However, within the hematopoietic system, immature HSPCs, including those within the myeloid lineage, lack AK1 expression and yet appear unaffected, even increased in frequency in RD. Upon differentiating beyond the promyelocyte stage, AK2-deficient cells exhibit severe defects, leading to neutropenia.1,2,12 These observations suggest that a lack of AK1 is not sufficient to explain the neutropenia phenotype of RD.

Previous studies exploring the disease mechanism of RD have largely focused on linking AK2 deficiency to impaired oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS).12-15 However, cells have a myriad of redundant ADP-producing pathways that can provide substrates for ATP synthesis. Furthermore, the specific cell types that are predominantly affected in RD, that is, neutrophils and T cells, are able to rely on glycolysis for ATP production, both under physiologic conditions and under stress.16-22 These observations indicate more complex metabolic mechanisms underlying the hematopoietic phenotype in RD. Herein, we identify the cellular and metabolic consequences of AK2 deficiency in human hematopoietic cells by combining single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) of primary bone marrow from patients with RD with a CRISPR-based experimental model of AK2 deficiency in human HSPCs.

Materials and methods

scRNA-seq

Bone marrow samples from patients with RD were obtained under Boston Children’s Hospital Institutional Review Board approval (0409113R). CD45+ cells were sorted for scRNA-seq. scRNA-seq libraries were constructed using Chromium Single Cell 3ʹ GEM, Library & Gel Bead Kit v3 (10x Genomics). Libraries were sequenced on Illumina NextSeq 500. scRNA-seq data from bone marrow CD45+ cells of 9 healthy human donors, available through published data sets,23,24 served as a control. Read alignment to the human genome hg19, cell barcode calling, and Unique Molecular Identifier counts were determined using Cell Ranger 3.0.0 (10x Genomics). Cell clustering and differential gene expression analyses were performed using Seurat v3 (Satija Lab).25 Gene ontology enrichment and pathway enrichment analysis were performed using ClusterProfiler.26,27 Additional materials and methods are described in the supplemental Materials, available on the Blood website.

Results

AK2 deficiency causes pervasive changes in ribonucleoprotein metabolism during hematopoiesis

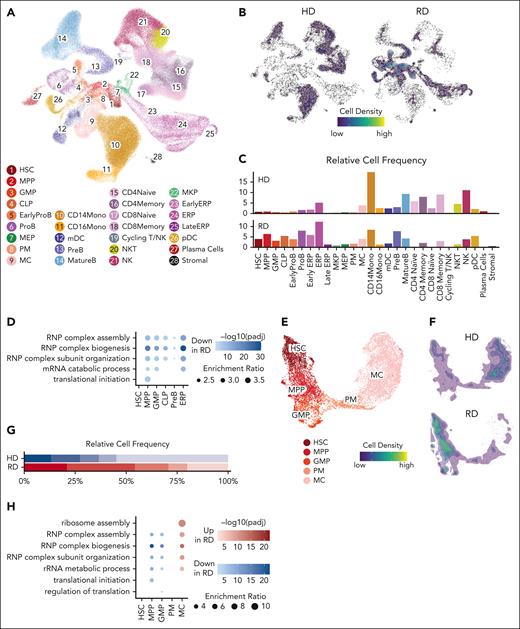

To assess the mechanistic basis of RD, we performed scRNA-seq on bone marrow samples of 2 previously reported patients with biallelic AK2 c.542G>A, p.R175Q missense mutations,4,11,12 and of 9 healthy donor controls.23 Unsupervised clustering identified 22 individual HSPC and mature hematopoietic cell populations (Figure 1A; supplemental Figure 1A). Bone marrow of patients with RD bone marrow had a relatively larger percentage of immature cells, that is, HSCs, multipotent progenitor cells (MPPs), granulocyte-monocyte progenitor cells (GMPs), common lymphoid progenitor cells, pro-B cells, and early erythroid progenitors. Conversely, mature populations across granulocytic and mature T-, B-, and natural killer cell lineages were significantly decreased. In addition, there was a moderate decrease in monocytes among patients with RD (Figure 1B-C; supplemental Figure 1B). AK2 was widely expressed among hematopoietic cells, whereas AK1 was mainly expressed by erythroid lineage cells (supplemental Figure 1C). A gene set enrichment analysis comparing individual HSPC clusters of patients with RD and healthy donors revealed that the most significant differentially expressed pathways were related to ribosome biogenesis and assembly, ribosomal RNA catabolism and translational initiation, all of which were significantly downregulated in HSPCs of patients with RD (Figure 1D).

scRNA-seq analysis of bone marrow of patients with RD reveals pervasive changes in hematopoietic differentiation and defects in ribonucleoprotein metabolism across multiple lineages. (A) Unsupervised clustering of bone marrow cells from 2 patients with RD and 9 healthy donors (HD) identified 28 clusters represented by Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection for Dimension Reduction (UMAP). (B) Density distribution of HD and RD bone marrow cells across all clusters. (C) Relative cell frequencies of HD and RD bone marrow cells across all clusters. (D) Selection of top downregulated enriched gene sets in HSPC clusters of patients with RD relative to controls. Color represents enrichment trend. Dot size represents enrichment ratio. Enrichment ratio = (the number of observed differentially expressed genes from each gene ontology (GO) category/the number of genes from each GO category) divided by (total number of differentially expressed genes/total number of genes). (E) Subclustering of HSCs, multipotent (MPP, GMP) and committed (promyelocytes [PM] and MC) neutrophil progenitors visualized by UMAP. (F) Density distribution of HD and RD bone marrow HSCs and neutrophil progenitors. (G) Relative cell frequencies of HD and RD bone marrow HSCs and neutrophil progenitors. (H) Major RNP metabolism and translational initiation pathways are significantly downregulated in early neutrophil progenitors (MPP and GMP), but upregulated in the more mature MC cluster of patients with RD. (I) Expression levels of major RNP metabolism and translational initiation pathways during granulopoiesis in RD and HD bone marrow samples. Line and ribbon plots represent median, 25th and 75th percentile of gene expression levels. B, B cells; CLP, common lymphoid progenitor cell; CMP, common myeloid progenitor cell; ERP, erythroid progenitor cell; MC, myelocytes/metamyelocytes; mDC, myeloid dendritic cell; MEP, megakaryocyte–erythroid progenitor cell; MKP, megakaryocyte progenitor cell; NK, natural killer cell; NKT, natural killer T cell; pDC, plasmacytoid dendritic cell; RNP, ribonucleoprotein.

scRNA-seq analysis of bone marrow of patients with RD reveals pervasive changes in hematopoietic differentiation and defects in ribonucleoprotein metabolism across multiple lineages. (A) Unsupervised clustering of bone marrow cells from 2 patients with RD and 9 healthy donors (HD) identified 28 clusters represented by Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection for Dimension Reduction (UMAP). (B) Density distribution of HD and RD bone marrow cells across all clusters. (C) Relative cell frequencies of HD and RD bone marrow cells across all clusters. (D) Selection of top downregulated enriched gene sets in HSPC clusters of patients with RD relative to controls. Color represents enrichment trend. Dot size represents enrichment ratio. Enrichment ratio = (the number of observed differentially expressed genes from each gene ontology (GO) category/the number of genes from each GO category) divided by (total number of differentially expressed genes/total number of genes). (E) Subclustering of HSCs, multipotent (MPP, GMP) and committed (promyelocytes [PM] and MC) neutrophil progenitors visualized by UMAP. (F) Density distribution of HD and RD bone marrow HSCs and neutrophil progenitors. (G) Relative cell frequencies of HD and RD bone marrow HSCs and neutrophil progenitors. (H) Major RNP metabolism and translational initiation pathways are significantly downregulated in early neutrophil progenitors (MPP and GMP), but upregulated in the more mature MC cluster of patients with RD. (I) Expression levels of major RNP metabolism and translational initiation pathways during granulopoiesis in RD and HD bone marrow samples. Line and ribbon plots represent median, 25th and 75th percentile of gene expression levels. B, B cells; CLP, common lymphoid progenitor cell; CMP, common myeloid progenitor cell; ERP, erythroid progenitor cell; MC, myelocytes/metamyelocytes; mDC, myeloid dendritic cell; MEP, megakaryocyte–erythroid progenitor cell; MKP, megakaryocyte progenitor cell; NK, natural killer cell; NKT, natural killer T cell; pDC, plasmacytoid dendritic cell; RNP, ribonucleoprotein.

To better understand what causes neutropenia in RD, we subclustered HSCs, MPPs, GMPs, promyelocytes, and myelocytes from patients with RD and controls (Figure 1E; supplemental Figure 1D). Mature neutrophils were not represented in both RD and control samples because high levels of ribonucleases and proteinases interfere with capture on droplet-based scRNA-seq platforms.28 Patients with RD exhibited higher frequencies of HSCs, MPPs, and GMPs, equal frequencies of promyelocytes, and significantly decreased frequencies of myelocytes relative to controls (Figure 1F-G; supplemental Figure 1E). Gene set enrichment analysis of the subclustered granulocyte lineage retrieved a similar set of differentially expressed pathways related to ribosome biogenesis and translation. Although ribonucleoprotein-related gene sets were decreased in HSCs, MPPs, and GMPs, they were paradoxically increased in expression in the myelocytes of patients with RD (Figure 1H-I). To investigate this observation, we developed a disease model that enables differentiation stage–specific dissection of neutropenia in RD.

An AK2 deletion model in human HSPCs

We inactivated AK2 in primary human CD34+ HSPCs using CRISPR/CRISPR-associated protein 9 (Cas9) gene editing to recapitulate the failure of granulopoiesis in RD in culture (supplemental Figure 2A). To ensure comprehensive inactivation of AK2 on both alleles, we combined CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing with adeno-associated viral vector delivery of 2 homologous donors containing different fluorescent reporters (green fluorescent protein [GFP] and blue fluorescent protein [BFP])29,30 that disrupt the AK2 gene at the catalytic LID domain (Figure 2A). This strategy allows selection of biallelically edited cells (GFP+ and BFP+) by flow cytometry (Figure 2B). AK2-edited (AK2–/–) HSPCs showed complete absence of AK2 protein (Figure 2B) and abnormal splicing (supplemental Figure 2B). Primary HSPCs labeled with GFP+ and BFP+ reporters at the safe harbor locus, AAVS1,31 were used as a control (AAVS1–/–).

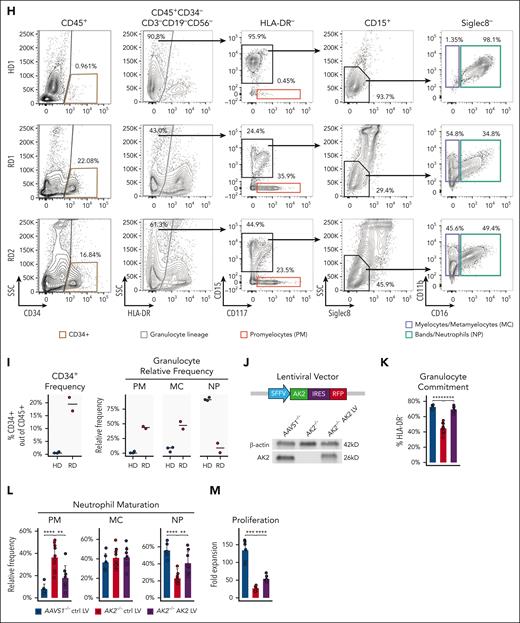

A novel AK2 deletion model in human HSPCs using CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing. (A) Design of biallelic AK2 knockout CRISPR/Cas9 model. AK2 guide RNA (gRNA) targets the LID domain. Two rAAV6 donors, containing left and right homologous arms (LHA and RHA) flanking the GFP and BFP reporters, respectively, are used as repair templates to introduce AK2 loss-of-function mutations following CRISRP/Cas9 DNA cutting at the gRNA targeting site. (B) Representative flow cytometry analysis showing that cells with biallelic AK2 insertions are enriched in the GFP+BFP+ fraction. Western blot analysis confirmed the absence of AK2 protein expression in GFP+BFP+AK2-edited HSPCs. (C) Representative flow cytometry analysis of AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– cells at day 7 of in vitro neutrophil (NP) differentiation. (D) Frequency of granulocyte lineage–committed (HLA-DR–) cells in AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– samples (n = 10 each), at day 7 of in vitro NP differentiation. (E) Relative frequencies of PMs, myelocytes (MCs), and NPs within the granulocyte-committed compartment in AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– cells (n = 10 each), at day 7 of in vitro NP differentiation. (F) Proliferation curves showing the fold expansion rate of AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– cells (n = 6 each) during NP differentiation. (G) Yield of PMs, MCs, and NPs of AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– cells (n = 9 each), at day 7 of in vitro NP differentiation. Here and onward, the yield of each cell type is calculated using the following formula: cell number fold change at day 7 of in vitro NP differentiation compared with day 0, multiplied by percentage of each cell type out of total live cells (determined by flow cytometry). (H) Representative flow cytometry analysis characterizing CD34+ HSPCs and granulocytic lineage in HD and RD bone marrow cells. (I) Frequency of CD34+ HSPCs and relative frequencies of PMs, MCs, and NPs within the granulocyte-committed compartment. Horizontal bars represent medians. HD, n = 3; RD, n = 2. Discrepancies between cell frequencies by scRNA-seq and flow cytometry analysis are due to NP drop-out analyzed on a droplet-based scRNA-seq platform. (J) Design of the AK2 overexpression lentiviral vector that drives the expression of a splice variant of AK2 and an emiRFP670 reporter under an SFFV promoter. AK2 expression level of AK2 LV transduced AK2–/– cells was determined by western blot analysis. (K-M) Frequency of granulocyte lineage–committed cells at day 7 of in vitro culture; PM, MC, and NP frequency; and proliferation rate in AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– HSPCs transduced with control or AK2-overexpressing lentiviral vectors, respectively. AAVS1–/– control (ctrl) LV, n = 6; AK2–/– ctrl LV, n = 10; AK2–/–AK2 LV, n = 8. For panels D-E,G,K-M, bar plots represent means ± standard deviations. For the panel F, line and ribbon plots represent means ± standard deviations. P values were determined by paired 2-tailed Student t test for panels D-G or unpaired 2-tailed Student t test for panel J-L. ∗.01 < P < .05; ∗∗.001 < P < .01; ∗∗∗.0001 < P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001.

A novel AK2 deletion model in human HSPCs using CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing. (A) Design of biallelic AK2 knockout CRISPR/Cas9 model. AK2 guide RNA (gRNA) targets the LID domain. Two rAAV6 donors, containing left and right homologous arms (LHA and RHA) flanking the GFP and BFP reporters, respectively, are used as repair templates to introduce AK2 loss-of-function mutations following CRISRP/Cas9 DNA cutting at the gRNA targeting site. (B) Representative flow cytometry analysis showing that cells with biallelic AK2 insertions are enriched in the GFP+BFP+ fraction. Western blot analysis confirmed the absence of AK2 protein expression in GFP+BFP+AK2-edited HSPCs. (C) Representative flow cytometry analysis of AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– cells at day 7 of in vitro neutrophil (NP) differentiation. (D) Frequency of granulocyte lineage–committed (HLA-DR–) cells in AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– samples (n = 10 each), at day 7 of in vitro NP differentiation. (E) Relative frequencies of PMs, myelocytes (MCs), and NPs within the granulocyte-committed compartment in AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– cells (n = 10 each), at day 7 of in vitro NP differentiation. (F) Proliferation curves showing the fold expansion rate of AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– cells (n = 6 each) during NP differentiation. (G) Yield of PMs, MCs, and NPs of AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– cells (n = 9 each), at day 7 of in vitro NP differentiation. Here and onward, the yield of each cell type is calculated using the following formula: cell number fold change at day 7 of in vitro NP differentiation compared with day 0, multiplied by percentage of each cell type out of total live cells (determined by flow cytometry). (H) Representative flow cytometry analysis characterizing CD34+ HSPCs and granulocytic lineage in HD and RD bone marrow cells. (I) Frequency of CD34+ HSPCs and relative frequencies of PMs, MCs, and NPs within the granulocyte-committed compartment. Horizontal bars represent medians. HD, n = 3; RD, n = 2. Discrepancies between cell frequencies by scRNA-seq and flow cytometry analysis are due to NP drop-out analyzed on a droplet-based scRNA-seq platform. (J) Design of the AK2 overexpression lentiviral vector that drives the expression of a splice variant of AK2 and an emiRFP670 reporter under an SFFV promoter. AK2 expression level of AK2 LV transduced AK2–/– cells was determined by western blot analysis. (K-M) Frequency of granulocyte lineage–committed cells at day 7 of in vitro culture; PM, MC, and NP frequency; and proliferation rate in AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– HSPCs transduced with control or AK2-overexpressing lentiviral vectors, respectively. AAVS1–/– control (ctrl) LV, n = 6; AK2–/– ctrl LV, n = 10; AK2–/–AK2 LV, n = 8. For panels D-E,G,K-M, bar plots represent means ± standard deviations. For the panel F, line and ribbon plots represent means ± standard deviations. P values were determined by paired 2-tailed Student t test for panels D-G or unpaired 2-tailed Student t test for panel J-L. ∗.01 < P < .05; ∗∗.001 < P < .01; ∗∗∗.0001 < P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001.

When AK2–/– and AAVS1–/– HSPCs were differentiated in vitro along the granulocytic lineage (supplemental Figure 2A), AK2–/– HSPCs showed decreased granulocytic (HLA-DR–) commitment, arrested differentiation at the promyelocyte stage (CD15–CD117+), and failure to further mature into myelocytes (CD15+CD11b+CD16–) and neutrophils (CD15+CD11b+CD16+) (Figure 2C-E). The proliferation rate of AK2–/– HSPCs paralleled that of controls for the first 48 hours of differentiation, after which proliferation started to lag in AK2–/– cells (Figure 2F). Cultures of AK2–/– HSPCs gave rise to similar absolute numbers of promyelocytes, but substantially fewer myelocytes and neutrophils compared with controls (Figure 2G).

Flow cytometry analysis revealed a similar defect in granulocyte differentiation in the bone marrow of patients with RD. In the myeloid compartment (CD45+CD34–CD3–CD19–CD56–), RD samples exhibited considerably reduced granulocyte lineage commitment (HLA-DR–), a relative expansion of promyelocytes (CD117+), and decreased frequencies of more mature granulocyte-committed cells (CD15+CD11b+CD16–/+) consistent with the findings from our disease model (Figure 2H-I). These findings suggest that promyelocytes can tolerate AK2 deficiency but that AK2 function is necessary for the maturation into myelocytes and neutrophils.

To validate our model, AK2–/– progenitors were transduced with lentiviral vectors overexpressing AK2,32 split GFP,33 or the disease-causing AK2 c.542G>A mutation as controls (Figure 2J; supplemental Figure 2C). AK2 overexpression significantly rescued granulocytic commitment, neutrophil maturation, and the proliferation of AK2–/– progenitors compared with AK2–/– cells expressing the AK2 c.542G>A mutation or the split GFP control (Figure 2J-M; supplemental Figure 2C). Notably, AK2–/– cells transduced with the wild-type AK2 lentiviral construct exhibited lower levels of AK2 protein than AAVS1–/– control cells (Figure 2J), which may explain the incomplete rescue. The data show that biallelic AK2 deletion in human HSPCs recapitulates the failure of granulopoiesis in RD; as in patients with RD, the defect in granulopoiesis only became evident at later stages of differentiation.

AK2 deficiency leads to unexpected upregulation of anabolic pathways during granulopoiesis

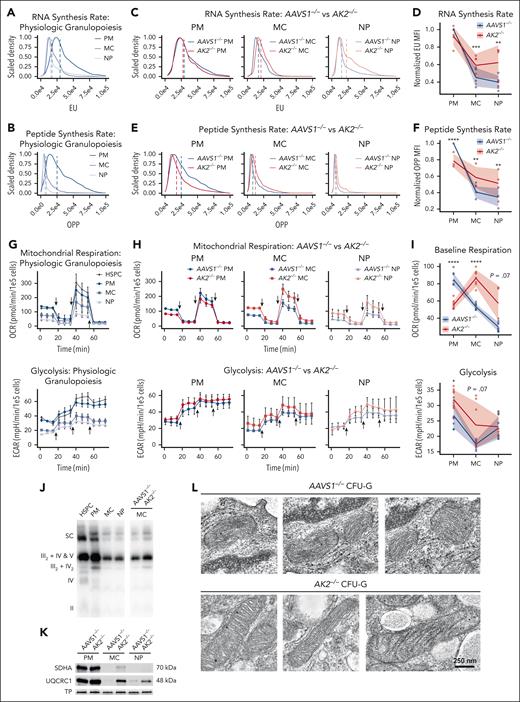

RNA and protein synthesis vary greatly at different stages of development.18 To test the impact of AK2 deficiency on RNA and protein synthesis, we used 5-ethynyl uridine and O-propargyl-puromycin labeling, respectively. In unmanipulated cells, promyelocytes had higher RNA and protein synthesis rates compared with myelocytes and neutrophils (Figure 3A-B). At the promyelocyte stage, AK2–/– cells synthesized less RNA and protein compared with AAVS1–/– cells. Beginning at the myelocyte stage, however, AK2-deficient cells exhibited a stark increase in RNA and protein synthesis relative to AAVS1–/– controls (Figure 3C-F), consistent with our findings in RD bone marrow.

AK2-deficient cells upregulate anabolic pathways and ATP synthesis during late-stage granulopoiesis. (A-B) Representative flow cytometry analysis of 5-ethynyl uridine (A) and OP-puromycin (B) incorporation in AAVS1–/– control PMs, MCs, and NPs. (C) Representative flow cytometry analysis of 5’-ethynyl uridine incorporation in AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– PMs, MCs, and NPs. (D) Line and ribbon plot showing median fluorescence intensity (MFI) of 5-ethynyl uridine of AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– PMs, MCs, and NPs normalized to AAVS1–/– PMs (n = 5 each). (E) Representative flow cytometry analysis of OP-puromycin incorporation in AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– PMs, MCs, and NPs. (F) Line and ribbon plot showing MFI of OP-puromycin of AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– PMs, MCs and NPs normalized to AAVS1–/– PMs (n = 3 each). (G) Oxygen consumption rate (OCR) and extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) of unmanipulated HSPCs, PMs, MCs, and NPs, measured by Seahorse XFe96 extracellular flux analyzer. Arrows indicate injections of oligomycin, FCCP, and rotenone/antimycin A, respectively. HSPC, n = 8; PM, n = 10; MC, n = 10; NP, n = 10. (H) OCR and ECAR of AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– PMs, MCs, and NPs. Arrows indicate injections of oligomycin, FCCP, and rotenone/antimycin A, respectively. AAVS1–/– PM, n = 8; AAVS1–/– MC, n = 10; AAVS1–/– NP, n = 10; AK2–/– PM, n = 10; AK2–/– MC, n = 7; AK2–/– NP, n = 4. (I) Baseline respiration and glycolysis rates of AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– PMs, MCs and NPs. Same experiment and replicate numbers as in panel H. (J) Native gel and blot of ETC supercomplexes of isolated mitochondria from unmanipulated HSPCs, PMs, MCs, and NPs, as well as AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– MCs. (K) Western blot of succinate dehydrogenase complex flavoprotein subunit A (SDHA) (complex II) and ubiquinol-cytochrome C reductase core protein 1 (UQCRC1) (complex III) in AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– PMs, MCs, and NPs, normalized to total protein (TP). (L) Representative electron microscope images of mitochondria from AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– CFU-G colonies. For panels A-C,E, dotted lines indicate MFI. For panels G-H, line plots represent means ± standard deviations of OCR or ECAR measurements. For panels D,F,I, line and ribbon plots represent means ± standard deviations. P values were determined by paired 2-tailed Student t test for panels D,F or unpaired 2-tailed Student t test for panel I. ∗.01 < P < .05; ∗∗.001 < P < .01; ∗∗∗.0001 < P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001.

AK2-deficient cells upregulate anabolic pathways and ATP synthesis during late-stage granulopoiesis. (A-B) Representative flow cytometry analysis of 5-ethynyl uridine (A) and OP-puromycin (B) incorporation in AAVS1–/– control PMs, MCs, and NPs. (C) Representative flow cytometry analysis of 5’-ethynyl uridine incorporation in AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– PMs, MCs, and NPs. (D) Line and ribbon plot showing median fluorescence intensity (MFI) of 5-ethynyl uridine of AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– PMs, MCs, and NPs normalized to AAVS1–/– PMs (n = 5 each). (E) Representative flow cytometry analysis of OP-puromycin incorporation in AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– PMs, MCs, and NPs. (F) Line and ribbon plot showing MFI of OP-puromycin of AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– PMs, MCs and NPs normalized to AAVS1–/– PMs (n = 3 each). (G) Oxygen consumption rate (OCR) and extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) of unmanipulated HSPCs, PMs, MCs, and NPs, measured by Seahorse XFe96 extracellular flux analyzer. Arrows indicate injections of oligomycin, FCCP, and rotenone/antimycin A, respectively. HSPC, n = 8; PM, n = 10; MC, n = 10; NP, n = 10. (H) OCR and ECAR of AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– PMs, MCs, and NPs. Arrows indicate injections of oligomycin, FCCP, and rotenone/antimycin A, respectively. AAVS1–/– PM, n = 8; AAVS1–/– MC, n = 10; AAVS1–/– NP, n = 10; AK2–/– PM, n = 10; AK2–/– MC, n = 7; AK2–/– NP, n = 4. (I) Baseline respiration and glycolysis rates of AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– PMs, MCs and NPs. Same experiment and replicate numbers as in panel H. (J) Native gel and blot of ETC supercomplexes of isolated mitochondria from unmanipulated HSPCs, PMs, MCs, and NPs, as well as AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– MCs. (K) Western blot of succinate dehydrogenase complex flavoprotein subunit A (SDHA) (complex II) and ubiquinol-cytochrome C reductase core protein 1 (UQCRC1) (complex III) in AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– PMs, MCs, and NPs, normalized to total protein (TP). (L) Representative electron microscope images of mitochondria from AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– CFU-G colonies. For panels A-C,E, dotted lines indicate MFI. For panels G-H, line plots represent means ± standard deviations of OCR or ECAR measurements. For panels D,F,I, line and ribbon plots represent means ± standard deviations. P values were determined by paired 2-tailed Student t test for panels D,F or unpaired 2-tailed Student t test for panel I. ∗.01 < P < .05; ∗∗.001 < P < .01; ∗∗∗.0001 < P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001.

During granulopoiesis, mitochondrial activity peaks at the early stages of development and then continuously declines,34,35 paralleling the anabolic demand during differentiation.18 To understand how AK2 deficiency affects mitochondrial function, we quantified mitochondrial respiration and glycolysis using an extracellular flux analyzer. In unmanipulated cells, baseline mitochondrial respiration and glycolysis rates peaked at the promyelocyte stage (Figure 3G; supplemental Figure 3A). Maximal respiration and spare respiratory capacity were highest in HSPCs, and then steadily declined during differentiation (supplemental Figure 3B). AK2–/– promyelocytes showed significantly lower baseline respiration and maximal respiration but slightly higher glycolytic capacity than AAVS1–/– controls (Figure 3H-I; supplemental Figure 3C). Spare respiratory capacity was not significantly altered by AK2 deficiency at the promyelocyte stage (Figure 3H; supplemental Figure 3D). Beginning at the myelocyte stage, however, AK2-deficient cells exhibited a striking increase in basal respiration, maximal respiration, and spare respiratory capacity relative to AAVS1–/– controls (Figure 3H-I; supplemental Figure 3D).

We further assessed electron transport chain (ETC) complex content and supercomplex formation. Following the trend of mitochondrial respiration, unmanipulated promyelocytes exhibited the highest content of ETC complexes and supercomplexes (Figure 3J; supplemental Figure 3E). Beginning at the myelocyte stage, AK2–/– cells, again, exhibited an increase in ETC complex expression and supercomplex formation relative to AAVS1–/– controls (Figure 3J-K). Electron microscopic imaging of AK2–/– HSPCs, differentiated in vitro into colony forming unit–granulocytes (CFU-Gs), revealed elongated mitochondria with tightly folded cristae, typical of cells under increased OXPHOS demand,36-38 whereas AAVS1–/– controls displayed small mitochondria characteristic of healthy neutrophils39,40 (Figure 3L). These studies further suggest that despite the severe metabolic defect, AK2-deficient myelocytes and neutrophils exhibited a paradoxical increase in anabolic pathways that was paralleled by an increase in mitochondrial function at the failing stages of granulopoiesis.

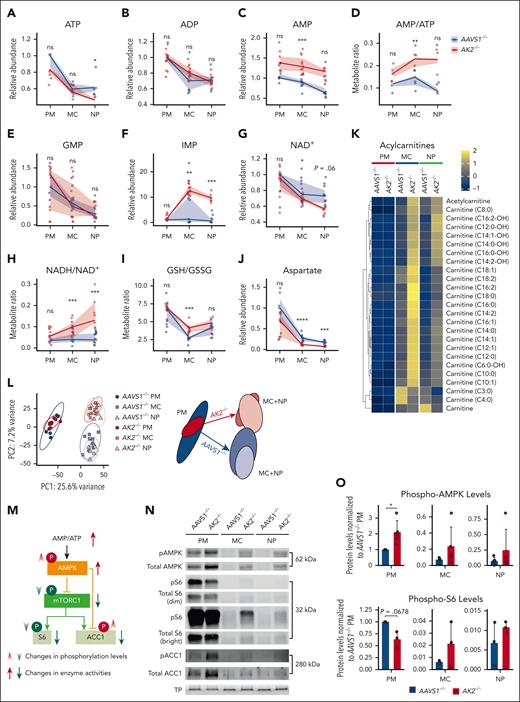

AK2 deficiency disrupts purine homeostasis

To systematically assess the metabolic impact of AK2 deficiency during granulopoiesis, we performed liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS).41,42 Cellular ATP and ADP levels did not significantly differ between AK2–/– and AAVS1–/– at the promyelocyte or myelocyte stages (Figure 4A-B); however, AK2 deficiency increased AMP levels at all stages of granulopoiesis (Figure 4C), resulting in increased AMP-ADP and AMP-ATP ratios (Figure 4D; supplemental Figure 4A). GMP levels did not significantly differ between AK2–/– and AAVS1–/– controls (Figure 4E). However, inosine monophosphate (IMP), a precursor of GMP and AMP, exhibited a >10-fold increase in abundance in AK2–/– myelocytes and neutrophils, whereas IMP was unchanged in AK2–/– promyelocytes relative to controls (Figure 4F). Notably, there was no increase in deoxynucleotides in AK2–/– cells (supplemental Figure 4B). These data show that AK2 deficiency causes a significant buildup of AMP and IMP in myelocytes and neutrophils, revealing a disruption of purine homeostasis at the failing stages of granulopoiesis.

AK2 deficiency disrupts purine homeostasis and causes ectopic mTOR and AMPK activation during late-stage granulopoiesis. (A-J) Relative quantities or ratios of metabolites in 10 000 AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– cells at PM, MC, and NP stages, respectively, measured by LC-MS/MS. Line and ribbon plots represent the median, 25th, and 75th percentiles of relative metabolite levels or metabolite ratios. Statistical analysis was performed using the Omics Data Analyzer. ∗.01 < P < .05; ∗∗.001 < P < .01; ∗∗∗ .0001 < P < .001; ∗∗∗∗ P < .0001. (K) Heatmaps of acylcarnitine levels in 10 000 AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– cells at PM, MC, and NP stages, respectively, measured by LC-MS/MS. (L) Principal component analysis of metabolomics analysis of AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– PMs, MCs, and NPs. The metabolic profiles of AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– PMs largely overlap but diverge in later maturation stages. (M) AK2 loss-of-function increases AMP/ATP ratio, which leads to increased AMPK phosphorylation and activation. Activated AMPK inhibits mTOR and downstream targets, including S6 and ACC1, through dephosphorylation of mTOR and S6 and phosphorylation of ACC1. (N) Representative western blot analysis of phosphorylated (p) and TP expression of AMPK, S6, and ACC1 in AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– PMs, MCs, and NPs. Dim and bright images of pS6 and total S6 blot are shown to enable discrimination between strong and faint bands at different stages of differentiation. Notably, AK2–/– cells contain less pS6 at the PM stage (seen on dim exposure) but more pS6 at the MC stage (seen on bright exposure) relative to the respective AAVS1–/– control stages. AK2–/– cells contain less phosho-AMPK (pAMPK) and total AMPK at the PM stage but more pAMPK and total AMPK at the MC and NP stages relative to the respective AAVS1–/– controls. From each sample, 25 μg of protein (measured by bicinchoninic acid) was diluted to 30 μL and mixed with 10 μL 4× Laemmli sample buffer; 20 μg protein (32 μL of the mixture) was loaded on a Mini-PROTEAN TGX precast AnykD or 10% gel for electrophoresis and blotting; 5 μg protein (8 μL of the same mixture) was loaded in parallel on a separate TGX Stain-Free gel to visualize TP. (O) Quantification of western blot analysis of phosphorylated AMPK and S6 levels in AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– PMs, MCs and NPs, normalized first to TP levels, and second to protein levels in AAVS1–/– PMs. Phospho-AMPK, n = 5 each; Phospho-S6, n = 3 each. Bar plots represent means ± standard deviations. P values were determined by paired 2-tailed Student t test. ns, not significant.

AK2 deficiency disrupts purine homeostasis and causes ectopic mTOR and AMPK activation during late-stage granulopoiesis. (A-J) Relative quantities or ratios of metabolites in 10 000 AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– cells at PM, MC, and NP stages, respectively, measured by LC-MS/MS. Line and ribbon plots represent the median, 25th, and 75th percentiles of relative metabolite levels or metabolite ratios. Statistical analysis was performed using the Omics Data Analyzer. ∗.01 < P < .05; ∗∗.001 < P < .01; ∗∗∗ .0001 < P < .001; ∗∗∗∗ P < .0001. (K) Heatmaps of acylcarnitine levels in 10 000 AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– cells at PM, MC, and NP stages, respectively, measured by LC-MS/MS. (L) Principal component analysis of metabolomics analysis of AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– PMs, MCs, and NPs. The metabolic profiles of AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– PMs largely overlap but diverge in later maturation stages. (M) AK2 loss-of-function increases AMP/ATP ratio, which leads to increased AMPK phosphorylation and activation. Activated AMPK inhibits mTOR and downstream targets, including S6 and ACC1, through dephosphorylation of mTOR and S6 and phosphorylation of ACC1. (N) Representative western blot analysis of phosphorylated (p) and TP expression of AMPK, S6, and ACC1 in AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– PMs, MCs, and NPs. Dim and bright images of pS6 and total S6 blot are shown to enable discrimination between strong and faint bands at different stages of differentiation. Notably, AK2–/– cells contain less pS6 at the PM stage (seen on dim exposure) but more pS6 at the MC stage (seen on bright exposure) relative to the respective AAVS1–/– control stages. AK2–/– cells contain less phosho-AMPK (pAMPK) and total AMPK at the PM stage but more pAMPK and total AMPK at the MC and NP stages relative to the respective AAVS1–/– controls. From each sample, 25 μg of protein (measured by bicinchoninic acid) was diluted to 30 μL and mixed with 10 μL 4× Laemmli sample buffer; 20 μg protein (32 μL of the mixture) was loaded on a Mini-PROTEAN TGX precast AnykD or 10% gel for electrophoresis and blotting; 5 μg protein (8 μL of the same mixture) was loaded in parallel on a separate TGX Stain-Free gel to visualize TP. (O) Quantification of western blot analysis of phosphorylated AMPK and S6 levels in AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– PMs, MCs and NPs, normalized first to TP levels, and second to protein levels in AAVS1–/– PMs. Phospho-AMPK, n = 5 each; Phospho-S6, n = 3 each. Bar plots represent means ± standard deviations. P values were determined by paired 2-tailed Student t test. ns, not significant.

Next, we assessed metabolites involved in redox balance. AK2–/– promyelocytes exhibited normal levels of NAD+ and normal ratios of the reduced form of NAD (NADH) to NAD+ (Figure 4G-H). However, in myelocytes and neutrophils, AK2 deficiency led to decreased NAD+ (Figure 4G) and a trend toward increasing NADH levels (supplemental Figure 4C), resulting in an increased NADH-NAD+ ratio (Figure 4H), suggestive of reductive stress.43-45 This was also reflected in an increased ratio of reduced to oxidized glutathione (GSH/GSSG), a major redox buffer44 in AK2–/– myelocytes (Figure 4I). Aspartate, a tricarboxylic acid cycle metabolite and essential substrate for protein and nucleotide synthesis, was also reduced in AK2–/– myelocytes and neutrophils (Figure 4J; supplemental Figure 4D). Moreover, we observed a striking increase in acylcarnitines in AK2–/– myelocytes and neutrophils, suggesting upregulated fatty acid mobilization that is halted before entry into the mitochondria because of a lack of available NAD+ (Figure 4K). Together, the data show that AK2 deficiency led to changes in purine metabolism, depletion of mitochondrial substrates, and a shift in redox balance toward reductive stress in myelocytes and neutrophils but not promyelocytes. A principal component analysis capturing all queried metabolites highlights this conclusion (Figure 4L).

Lack of effective metabolic checkpoints during AK2-deficient granulopoiesis

These observations raised the question of how promyelocytes maintain metabolic homeostasis despite AK2 deficiency. To answer this question, we assessed metabolic checkpoints during granulopoiesis. AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) are primary regulators of growth control that tune anabolic pathways according to the availability of nutrients and ATP.46 Anabolic pathways (ie, ribonucleoprotein synthesis and fatty acid synthesis) are activated by mTOR and acetyl-CoA carboxylase 1 (ACC1), respectively.47-49 Typically, increased AMP-ATP and AMP-ADP ratios (Figure 4D; supplemental Figure 4A) signal energetic scarcity and activate AMPK to curtail anabolic pathways (eg, mTOR and ACC1) to conserve energy consumption and increase energy production50 (Figure 4M). Therefore, to understand the cellular response to AK2 deficiency, we probed the expression of AMPK, mTOR, and ACC1. At the promyelocyte stage, AK2–/– cells showed an increase in total and phospho-AMPK, a decrease in total and phospho-S6, and an increase in total and phospho-ACC1 relative to AAVS1–/– controls. These findings are consistent with an activation of AMPK, which reduced mTORC1 (mTOR complex 1) signaling (marked by a decrease in phospho-S6) and ACC1 function (marked by an increase in phospho-ACC1) (Figure 4N-O; supplemental Figure 4E). AK2–/– myelocytes and neutrophils also exhibited higher levels of total and phospho-AMPK (Figure 4O), consistent with the AMPK-activating effect of high AMP levels at these stages (Figure 4C). However, AK2–/– myelocytes and neutrophils also showed increased levels of S6 and phospho-S6 relative to AAVS1–/– controls, suggesting a paradoxical increase in mTOR signaling despite AMPK activation (Figure 4N-O; supplemental Figure 4E). AK2–/– myelocytes and neutrophils thus failed to reduce mTOR signaling despite energetic scarcity. These data suggest that metabolic checkpoints effectively adapted to metabolic stress during the early stages of granulopoiesis but not during the later stages of granulopoiesis.

AK2–/– cells thus showed evidence of increased RNA and protein synthesis (Figure 3C-F), disrupted purine homeostasis (Figure 4A-F; supplemental Figures 4A and 5D-O), and mitochondrial substrate depletion (Figure 4G,J) at the failing stages of granulopoiesis. Given these results, we tested if exogenous checkpoint manipulation could rescue AK2-deficient myelopoiesis. Although low doses of the TORC1/2 (mTOR complex 1/2) inhibitor Torin-151 and the direct AMPK activator AICAR (5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleotide)52 promoted a trend toward increased proliferation in AK2–/– cells, neither of these drugs rescued proliferation to wild-type levels. Moreover, all tested mTOR and AMPK modulators inhibited granulopoiesis at moderate to high concentrations (supplemental Figure 4F-K). This suggests that multiple checkpoints are likely defective in AK2–/– myelocytes and neutrophils, and that the pharmacologic manipulation of failing checkpoints does not restore the intricate physiologic mechanisms of metabolic control. Thus, pharmacologic manipulation of checkpoints is unlikely to benefit patients with RD.

AK2 deficiency increases purine synthesis in myelocytes and neutrophils

Prior studies have demonstrated that compromised mitochondrial respiration leads to NAD+ and aspartate depletion, inhibiting the last steps of de novo AMP and GMP synthesis (Figure 5A), and resulting in elevated IMP levels.49,53,54 Our metabolomics data show that AK2 deficiency leads to NAD+ (Figure 4G) and aspartate depletion (Figure 4J; supplemental Figure 4D), and increased IMP levels (Figure 4F). We therefore reasoned that AK2 deficiency may impair de novo purine synthesis. To test this hypothesis, we repleted NAD+ levels through supplementation with nicotinamide riboside, and transduction with Lactobacillus brevis H2O-forming NADH oxidase (LbNOX) and its mitochondrial isoform mitoLbNOX.55 We also repleted aspartate transduced with the glutamate–aspartate transporter (GLAST).56 Although some of these measures partially rescued the differentiation of AK2–/– cells, they had little effect on proliferation (Figure 5B; supplemental Figure 5A). These observations suggest that NAD+ and aspartate depletion are not the primary cause of the proliferative defects observed in our RD model.

AK2 deficiency upregulates purine biosynthesis. (A) Diagram of purine de novo and salvage synthesis pathways. One molecule of aspartate is used to synthesize AMP from IMP, and 1 molecule of NAD+ is used to synthesize GMP from IMP. Aspartate and NAD+ depletion leads to compromised AMP and GMP synthesis, respectively. (B) Frequency of granulocyte lineage–committed (HLA-DR–) cells at day 7 of in vitro NP differentiation, frequency of PMs, MCs, and NPs, and proliferation rate of AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– HSPCs transduced with lentiviral (LV) vectors expressing GLAST, mitoLbNOX, LbNOX, or split GFP (spGFP) control. AAVS1–/– ctrl LV, n = 6; AK2–/– ctrl LV, n = 10; AK2–/– GLAST LV, n = 7; AK2–/– mitoLbNOX LV, n = 5; AK2–/–LbNOX LV, n = 4. (C) Diagram of [amide-15N]-glutamine tracing into purine nucleotides. AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– HSPCs were differentiated in a nucleoside-free medium comprising MEMα without nucleosides, with 10% dialyzed fetal bovine serum, and traced with 2-mM [amide-15N]-glutamine in otherwise glutamine-free, nucleoside-free medium for 6 hours. Up to 2 15N (=m + 2) can be incorporated into AICAR, IMP, AMP, and ATP, and up to 3 15N (=m + 3) can be incorporated into GMP and GTP. (D-G) Relative abundance of AICAR (D), ATP (E), GTP (F), and IMP (G) isotopes in AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– PMs, MCs, and NPs, cultured and traced under conditions described in panel C. n = 6 for each condition. (H) PM, MC, and NP yield of AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– cells differentiated in MEMα medium with or without nucleosides. Bar plots represent means ± standard deviations of yield. n = 3 for each condition. (I) Diagram of [15N4]-hypoxanthine tracing into purine nucleotides. AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– HSCPs were differentiated in MyeloCult medium and traced with 10-mg/mL [15N4]-hypoxanthine in otherwise hypoxanthine-free medium for 6 hours. Up to 4 15N (=m + 4) can be incorporated into IMP, AMP, ATP, GMP, and GTP. (J-M) Relative abundance of AMP (J), ATP (K), GTP (L), and IMP (M) isotopes in AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– PMs, MCs, and NPs, cultured and traced under conditions described in panel I. n = 6 for each condition. (N) Western blot analysis of HPRT1 expression in unmanipulated HSPCs, PMs, MCs, and NPs, normalized to TP. From each sample, 25 μg of protein (measured by bicinchoninic acid) was diluted to 30 μL and mixed with 10 μL 4× Laemmli sample buffer; 20 μg protein (32 μL of the mixture) was loaded on a Mini-PROTEAN TGX precast AnykD or 10% gel for electrophoresis and blotting; 5 μg protein (8 μL of the same mixture) was loaded on a separate TGX Stain-Free gel to visualize TP. (O) HPRT1 enzymatic activity of AAVS1–/– (blue) and AK2–/– (red) MCs (n = 2 each) using the PRECICE HPRT assay kit. HPRT activity was continuously measured spectrophotometrically. Aqua and pink curves represent AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– MC protein samples without added hypoxanthine (n = 2 each). Lines and ribbons represent means ± standard deviations of absorbance at 340 nm at each time point. For panels B,H, bar plots represent means ± standard deviations. P values were determined by unpaired 2-tailed Student t test. For panels D-G,J-M, bar plots represent means ± standard deviations of relative abundance of isotopes. Statistical analysis was performed using the Omics Data Analyzer. ∗.01 < P < .05; ∗∗.001 < P < .01; ∗∗∗.0001 < P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001.

AK2 deficiency upregulates purine biosynthesis. (A) Diagram of purine de novo and salvage synthesis pathways. One molecule of aspartate is used to synthesize AMP from IMP, and 1 molecule of NAD+ is used to synthesize GMP from IMP. Aspartate and NAD+ depletion leads to compromised AMP and GMP synthesis, respectively. (B) Frequency of granulocyte lineage–committed (HLA-DR–) cells at day 7 of in vitro NP differentiation, frequency of PMs, MCs, and NPs, and proliferation rate of AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– HSPCs transduced with lentiviral (LV) vectors expressing GLAST, mitoLbNOX, LbNOX, or split GFP (spGFP) control. AAVS1–/– ctrl LV, n = 6; AK2–/– ctrl LV, n = 10; AK2–/– GLAST LV, n = 7; AK2–/– mitoLbNOX LV, n = 5; AK2–/–LbNOX LV, n = 4. (C) Diagram of [amide-15N]-glutamine tracing into purine nucleotides. AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– HSPCs were differentiated in a nucleoside-free medium comprising MEMα without nucleosides, with 10% dialyzed fetal bovine serum, and traced with 2-mM [amide-15N]-glutamine in otherwise glutamine-free, nucleoside-free medium for 6 hours. Up to 2 15N (=m + 2) can be incorporated into AICAR, IMP, AMP, and ATP, and up to 3 15N (=m + 3) can be incorporated into GMP and GTP. (D-G) Relative abundance of AICAR (D), ATP (E), GTP (F), and IMP (G) isotopes in AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– PMs, MCs, and NPs, cultured and traced under conditions described in panel C. n = 6 for each condition. (H) PM, MC, and NP yield of AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– cells differentiated in MEMα medium with or without nucleosides. Bar plots represent means ± standard deviations of yield. n = 3 for each condition. (I) Diagram of [15N4]-hypoxanthine tracing into purine nucleotides. AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– HSCPs were differentiated in MyeloCult medium and traced with 10-mg/mL [15N4]-hypoxanthine in otherwise hypoxanthine-free medium for 6 hours. Up to 4 15N (=m + 4) can be incorporated into IMP, AMP, ATP, GMP, and GTP. (J-M) Relative abundance of AMP (J), ATP (K), GTP (L), and IMP (M) isotopes in AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– PMs, MCs, and NPs, cultured and traced under conditions described in panel I. n = 6 for each condition. (N) Western blot analysis of HPRT1 expression in unmanipulated HSPCs, PMs, MCs, and NPs, normalized to TP. From each sample, 25 μg of protein (measured by bicinchoninic acid) was diluted to 30 μL and mixed with 10 μL 4× Laemmli sample buffer; 20 μg protein (32 μL of the mixture) was loaded on a Mini-PROTEAN TGX precast AnykD or 10% gel for electrophoresis and blotting; 5 μg protein (8 μL of the same mixture) was loaded on a separate TGX Stain-Free gel to visualize TP. (O) HPRT1 enzymatic activity of AAVS1–/– (blue) and AK2–/– (red) MCs (n = 2 each) using the PRECICE HPRT assay kit. HPRT activity was continuously measured spectrophotometrically. Aqua and pink curves represent AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– MC protein samples without added hypoxanthine (n = 2 each). Lines and ribbons represent means ± standard deviations of absorbance at 340 nm at each time point. For panels B,H, bar plots represent means ± standard deviations. P values were determined by unpaired 2-tailed Student t test. For panels D-G,J-M, bar plots represent means ± standard deviations of relative abundance of isotopes. Statistical analysis was performed using the Omics Data Analyzer. ∗.01 < P < .05; ∗∗.001 < P < .01; ∗∗∗.0001 < P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001.

To precisely understand the impact of AK2 deficiency on purine metabolism and why this leads to increased IMP levels, we conducted isotope tracing of the de novo purine synthesis and purine salvage pathways (conditions summarized in supplemental Figure 5B). To analyze de novo purine synthesis,57-59 in vitro culture and [amide-15N] glutamine tracing was performed in nucleoside-free medium (Figure 5C). In AAVS1–/– controls, the abundance of AICAR (m + 2), ATP (m + 2), and guanosine triphosphate (GTP) (m + 3) peaked at the promyelocyte stage and decreased with maturation (Figure 5D-F). AK2–/– promyelocytes exhibited significantly reduced abundance of de novo synthesized AICAR (m + 2), ATP (m + 2), and GTP (m + 3) relative to controls (Figure 5D-F). In contrast, beginning at the myelocyte stage, AK2–/– cells exhibited an increase in AICAR (m + 2) (Figure 5D) and a trend toward an increase in ADP (m + 2) (supplemental Figure 5C), suggesting increased de novo purine synthesis. De novo GTP (m + 3) synthesis was decreased in AK2–/– neutrophils compared with controls, consistent with the limiting effects of NAD+ depletion in neutrophils (Figure 5F). Again, we noted a striking rise in 15N-labeled and unlabeled IMP in AK2–/– myelocytes and neutrophils (Figure 5G). The rise in IMP made the increase in AICAR (m + 2) even more surprising given that increased IMP levels allosterically inhibit phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate amidotransferase, the rate-limiting enzyme controlling de novo purine synthesis.60 These data show that at the promyelocyte stage, AK2–/– cells downregulate the de novo purine synthesis pathway, whereas de novo purine synthesis (up to AICAR) was increased in AK2–/– myelocytes and neutrophils. AK2–/– neutrophils exhibited a decrease in de novo synthesized GTP.

To test if de novo purine synthesis becomes limiting during AK2-deficient granulopoiesis, we cultured AK2–/– cells in nucleoside-free medium. Nucleoside-free culture conditions did not aggravate the disease phenotype in AK2–/– cells but showed a trend toward improved differentiation of AK2–/– neutrophils (Figure 5H). These findings suggest that purine depletion is not a driver for the disease phenotype in RD.

Next, we interrogated the purine salvage pathway using [15N4]-labeled hypoxanthine (Figure 5I). AK2–/– cells exhibited significantly increased abundance of AMP (m + 4), ADP (m + 4), ATP (m + 4), and GTP (m + 4) relative to AAVS1–/– controls at all stages of differentiation (Figure 5J-L; supplemental Figure 5D), suggesting that purine salvage is upregulated throughout AK2-deficient granulopoiesis. IMP (m + 4) was significantly upregulated in AK2–/– myelocytes and neutrophils (Figure 5M). Because increased IMP levels inhibit hypoxanthine-guanine-phosphoribosyl-transferase 1 (HPRT1), the rate-limiting enzyme of purine salvage,61,62 we probed HPRT1 protein expression and enzymatic activity. In unmanipulated cells, HPRT1 protein expression peaked at the promyelocyte stage (Figure 5N). HPRT1 protein and activity were increased in AK2–/– myelocytes compared with AAVS1–/– myelocytes (Figure 5N-O). These studies showed that AK2 deficiency increases the activity of both de novo (up to AICAR) and salvage purine synthesis pathways during late-stage granulopoiesis despite highly increased IMP and AMP levels.

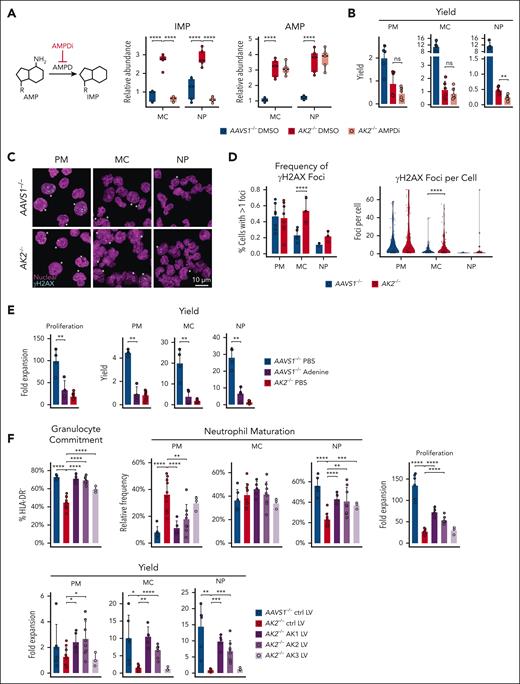

AK2 deficiency causes nucleotide imbalance and replication stress

Our isotope tracing studies revealed that IMP levels in AK2–/– cells were highest when the purine salvage pathway was used (Figure 5M) and correlated with the increasing fractional enrichment of AMP (m + 4) in AK2–/– myelocytes and neutrophils (Figure 5J). This raised the question of whether AK2-deficient cells actively deaminated AMP to IMP. To answer this question, we pharmacologically inhibited the enzyme AMP deaminase (AMPD) (AMPDi; #5336420001; Sigma)60 in AK2–/– cells. AMPDi-treated AK2–/– myelocytes and neutrophils experienced a dramatic drop in IMP levels down to the level of AAVS1–/– controls, whereas AMP levels were not significantly changed (Figure 6A), likely because of the much larger pool size of AMP relative to IMP.63 Notably, AMPD inhibition did not rescue the maturation defects in AK2–/– myelocytes and neutrophils (Figure 6B). This raises the possibility that AMP deamination is a cellular response to increased AMP levels. Recent studies in cell lines have shown that nucleotide imbalance inhibits proliferation as a result of replication stress.64 AK2-deficient cells also exhibited signs of replication stress, as evidenced by a significant increase in γH2AX foci at myelocyte and neutrophil stages compared with controls (Figure 6C-D). In contrast, AK2-deficient and control promyelocytes did not exhibit any difference in γH2AX foci (Figure 6C-D). To test if nucleotide imbalance from excess AMP affected proliferation, we induced conditions of exogenous purine imbalance in our in vitro model. In AAVS1–/– control cells, excess adenosine led to profoundly decreased proliferation and differentiation, resembling the RD phenotype (Figure 6E). These results indicate that nucleotide imbalance decreases proliferation and differentiation during granulopoiesis.

AK2 deficiency causes nucleotide imbalance and can be rescued by cytosolic AK1. (A) Relative abundance of IMP and AMP in 10 000 AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– cells at MC and NP stages, measured by LC-MS/MS. Statistical analysis was performed using the Omics Data Analyzer. ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. AMPD inhibitor treatment normalizes IMP levels in AK2–/– MCs and NPs but does not change AMP levels. (B) PM, MC, and NP yield of AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– cells treated with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or 20-μM AMPD inhibitor (AMPDi). AAVS1–/– DMSO, n = 5; AK2–/– DMSO, n = 6; AK2–/– AMPDi, n = 6. (C) Representative confocal images of nuclear (magenta) and γH2AX (cyan) staining of AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– PMs, MCs, and NPs. Asterisks denote cells with at least 1 γH2AX focus. (D) Quantification of cells with ≥1 γH2AX foci and frequency of γH2AX foci/cell. Number of independent experiments and cells quantified: AAVS1–/– PMs, 7 experiments, 148 cells; AAVS1–/– MCs, 5 experiments, 174 cells; 81 AAVS1–/– NPs, 3 experiments, 81 cells; AK2–/– PMs, 8 experiments, 133 cells; AK2–/– MCs, 4 experiments, 175 cells; AK2–/– NPs, 3 experiments, 116 cells. In the left panel, bar plots represent means ± standard deviations from each independent experiment. P values were determined by Fisher exact test. In the right panel, P values were determined by Wilcoxon test with Bonferroni correction. ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. (E) Proliferation and yield of AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– cells treated with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or 0.2-μM adenine. AAVS1–/– PBS, n = 4; AAVS1–/– adenine, n = 4; AK2–/– PBS, n = 7. (F) Frequency of granulocyte lineage–committed (HLA-DR–) cells at day 7 of in vitro NP differentiation, frequency of PMs, MCs, and NPs, proliferation rates, and yield of AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– HSPCs transduced with lentiviral (LV) vectors expressing AK1, AK2, AK3 or spGFP control. AAVS1–/– ctrl LV, n = 6; AK2–/– ctrl LV, n = 10; AK2–/– AK1 LV, n = 5; AK2–/– AK2 LV, n = 8; AK2–/– AK3 LV, n = 3. For panels B,E-F, bar plots represent means ± standard deviations. P values were determined by unpaired 2-tailed Student t test. ∗.01 < P < .05; ∗∗.001 < P < .01; ∗∗∗.0001 < P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. PRPP, phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate.

AK2 deficiency causes nucleotide imbalance and can be rescued by cytosolic AK1. (A) Relative abundance of IMP and AMP in 10 000 AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– cells at MC and NP stages, measured by LC-MS/MS. Statistical analysis was performed using the Omics Data Analyzer. ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. AMPD inhibitor treatment normalizes IMP levels in AK2–/– MCs and NPs but does not change AMP levels. (B) PM, MC, and NP yield of AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– cells treated with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or 20-μM AMPD inhibitor (AMPDi). AAVS1–/– DMSO, n = 5; AK2–/– DMSO, n = 6; AK2–/– AMPDi, n = 6. (C) Representative confocal images of nuclear (magenta) and γH2AX (cyan) staining of AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– PMs, MCs, and NPs. Asterisks denote cells with at least 1 γH2AX focus. (D) Quantification of cells with ≥1 γH2AX foci and frequency of γH2AX foci/cell. Number of independent experiments and cells quantified: AAVS1–/– PMs, 7 experiments, 148 cells; AAVS1–/– MCs, 5 experiments, 174 cells; 81 AAVS1–/– NPs, 3 experiments, 81 cells; AK2–/– PMs, 8 experiments, 133 cells; AK2–/– MCs, 4 experiments, 175 cells; AK2–/– NPs, 3 experiments, 116 cells. In the left panel, bar plots represent means ± standard deviations from each independent experiment. P values were determined by Fisher exact test. In the right panel, P values were determined by Wilcoxon test with Bonferroni correction. ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. (E) Proliferation and yield of AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– cells treated with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or 0.2-μM adenine. AAVS1–/– PBS, n = 4; AAVS1–/– adenine, n = 4; AK2–/– PBS, n = 7. (F) Frequency of granulocyte lineage–committed (HLA-DR–) cells at day 7 of in vitro NP differentiation, frequency of PMs, MCs, and NPs, proliferation rates, and yield of AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– HSPCs transduced with lentiviral (LV) vectors expressing AK1, AK2, AK3 or spGFP control. AAVS1–/– ctrl LV, n = 6; AK2–/– ctrl LV, n = 10; AK2–/– AK1 LV, n = 5; AK2–/– AK2 LV, n = 8; AK2–/– AK3 LV, n = 3. For panels B,E-F, bar plots represent means ± standard deviations. P values were determined by unpaired 2-tailed Student t test. ∗.01 < P < .05; ∗∗.001 < P < .01; ∗∗∗.0001 < P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. PRPP, phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate.

AK2 deficiency is rescued by cytosolic AK1, not mitochondrial AK3

To test the hypothesis that derangements in cytosolic nucleotide balance contribute to the proliferative defect in RD, we leveraged 2 compartment-specific adenylate kinase isoenzymes, AK1 and AK3, with low expression during granulopoiesis (supplemental Figure 6A). AK1 functions in the cytosol, AK3 functions in the mitochondrial matrix, and AK2 acts at the interface.8,9 To test if restoring adenine nucleotide homeostasis in a compartment-specific (cytosol vs matrix) manner can reverse the RD phenotype, we overexpressed AK1 and AK3 in AK2–/– cells using lentiviral vectors (supplemental Figure 6B-D). AK2–/– cells transfected with AK1 exhibited significantly improved proliferation and differentiation (Figure 6F), surpassing the AK2-rescue construct in efficiency. In contrast, overexpressing mitochondrial AK3 had no impact on proliferation and promoted little improvement in the differentiation of AK2–/– cells compared with AK1 and AK2 (Figure 6F). These findings highlight that derangements in cytosolic adenine nucleotide balance drive the failure of granulopoiesis in RD.

Discussion

Metabolism is tightly regulated during hematopoiesis.65-67 Exposure of quiescent HSCs to supraphysiologic oxygen activates OXPHOS metabolism and promotes proliferation and myeloid-biased differentiation.21 Conversely, defects in myeloid differentiation, such as in the context of Fanconi anemia and Shwachman-Bodian-Diamond syndrome, have been associated with compromised OXPHOS.68-71 The mTOR pathway plays a pivotal role in the regulation of myeloid differentiation. Deletion of the mTORC1 component Raptor results in arrested maturation at the GMP stage,72 making mTOR activity indispensable for myeloid differentiation.

Our study shows that effective metabolic checkpoints are lacking at the later stages of granulopoiesis. As granulocytes enter the path of terminal differentiation, their life span is short; hence, it may be unsurprising that metabolic checkpoints are dispensable under physiologic conditions. However, metabolic checkpoints become essential for survival under metabolic stress. AK2-deficient early granulocyte progenitors (and other HSPCs) demonstrated little transcriptional or metabolomic aberrations and maintained near-normal proliferation rates. This underscores that AK2 deficiency is not catastrophic in all cells, regardless of whether they express AK1. Metabolic checkpoints promote adaptive responses to AK2 deficiency by downregulating anabolic pathways, conserving nutrients and energy essential for cell growth, thus minimizing the detrimental rise of AMP levels. Ineffective checkpoint control permitted mTOR activation in AK2-deficient cells (Figure 4N-O), resulting in a pathologic increase in anabolic pathway activation. This process was paralleled by a rise in AMP and IMP levels, incompatible with cell survival. Interestingly, bone marrow from patients with neutropenia due to other clinical conditions (eg, pharmacologic or viral bone marrow suppression) exhibits the same pathognomonic maturation arrest at the promyelocyte stage.73-75 This raises the possibility that loss of metabolic checkpoint control during late-stage granulopoiesis causes metabolic vulnerabilities that are relevant to other clinical settings.

We and others have previously highlighted a role for oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of RD in other disease models.12,76,77 Reductive and oxidative stress are not mutually exclusive because they can coexist within the same cell but in different subcellular compartments.44,45,78-80 Although we observed increased myeloid maturation in an induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) model for RD after adding glutathione to the culture,12 we did not observe increased neutrophil counts when treating 2 patients with RD with glutathione (unpublished observations). Similarly, a recent study reported that the pyruvate carrier inhibitor, UK5099, improved myeloid maturation in an iPSC model.81 However, when we tested UK5099 and the carnitine palmitoyl-transferase 1 inhibitor, etomoxir, in our model, we did not observe improved proliferation or maturation (supplemental Figure 6E). The hematopoietic differentiation of iPSCs appears to replicate yolk sac–like rather than adult-like hematopoiesis,82 consistent with the general observation that iPSCs produce cells with embryonic or fetal phenotypes. Discrepancies between observations in patients and disease models of varying complexity highlight the importance of mimicking the granulopoiesis in human bone marrow as closely as possible. This is essential for both drug testing and disease modeling, and has revealed the pervasive changes in metabolic control that occur during AK2-deficient granulopoiesis. Once metabolic checkpoint control is lost, the detrimental effects of AK2 deficiency are likely pleiotropic. Although cytosolic nucleotide imbalance appears to be an important driver of replication stress, depletion of essential substrates may also contribute and collectively cause metabolic collapse of the cell.

Acknowledgments

The BioHPC high-performance computing cloud at University of Texas Southwestern was used for data analysis and storage, and metabolomics data analysis software deployment. Cord blood cells were made available by the Binns Program for Cord Blood Research. The Lorry Lokey Flow Cytometry Core was used for all flow cytometry. Graphical design of the visual abstract was provided by Ellen L. Bouchard, Riley Suhar, and Wenqing Wang.

K.G.W. is an Uytengsu-Hamilton endowed faculty scholar at Stanford School of Medicine. S.J.M. is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator, the Mary McDermott Cook Chair in Pediatric Genetics, the Kathryne and Gene Bishop Distinguished Chair in Pediatric Research, the director of the Hamon Laboratory for Stem Cells and Cancer, and a Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas Scholar. A.D. was supported by a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award Fellowship (National Institutes of Health [NIH], National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [NHLBI] grant F32 HL 135975). This work was funded by the NIH, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases grant AI123571, NIH, NHLBI grant HL165489, NIH, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases grant DK118745, and the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF 31003A_179435). The study was also supported by NIH, Office of the Director S10 award 1S10OD028536-01, titled “OneView 4kX4k sCMOS camera for transmission electron microscopy applications” from the Office of Research Infrastructure Programs.

Authorship

Contribution: W.W., M.A., J.A., S.J.M., and K.G.W. designed research; W.W. and M.A. performed the experiments and analyzed the data; T.M., A.D., M.M.-S., and Z.Z. performed metabolomics analysis and isotope tracing; A.M. contributed to single-cell RNA-sequencing analysis; G.B. and L.G. performed electron transport chain supercomplex native gel and blotting; A.A., D.D., Y.N., M.P.-D., and M.H.P. assisted in establishing the AK2 deletion model; W.A.-H. provided primary patient specimens; and W.W., S.J.M., and K.G.W. wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Katja G. Weinacht, Stanford University School of Medicine, 240 Pasteur Dr, Palo Alto, CA 94305; email: kgw1@stanford.edu.

References

Author notes

Single-cell RNA-sequencing data have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus database (accession number GSE179346).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

![scRNA-seq analysis of bone marrow of patients with RD reveals pervasive changes in hematopoietic differentiation and defects in ribonucleoprotein metabolism across multiple lineages. (A) Unsupervised clustering of bone marrow cells from 2 patients with RD and 9 healthy donors (HD) identified 28 clusters represented by Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection for Dimension Reduction (UMAP). (B) Density distribution of HD and RD bone marrow cells across all clusters. (C) Relative cell frequencies of HD and RD bone marrow cells across all clusters. (D) Selection of top downregulated enriched gene sets in HSPC clusters of patients with RD relative to controls. Color represents enrichment trend. Dot size represents enrichment ratio. Enrichment ratio = (the number of observed differentially expressed genes from each gene ontology (GO) category/the number of genes from each GO category) divided by (total number of differentially expressed genes/total number of genes). (E) Subclustering of HSCs, multipotent (MPP, GMP) and committed (promyelocytes [PM] and MC) neutrophil progenitors visualized by UMAP. (F) Density distribution of HD and RD bone marrow HSCs and neutrophil progenitors. (G) Relative cell frequencies of HD and RD bone marrow HSCs and neutrophil progenitors. (H) Major RNP metabolism and translational initiation pathways are significantly downregulated in early neutrophil progenitors (MPP and GMP), but upregulated in the more mature MC cluster of patients with RD. (I) Expression levels of major RNP metabolism and translational initiation pathways during granulopoiesis in RD and HD bone marrow samples. Line and ribbon plots represent median, 25th and 75th percentile of gene expression levels. B, B cells; CLP, common lymphoid progenitor cell; CMP, common myeloid progenitor cell; ERP, erythroid progenitor cell; MC, myelocytes/metamyelocytes; mDC, myeloid dendritic cell; MEP, megakaryocyte–erythroid progenitor cell; MKP, megakaryocyte progenitor cell; NK, natural killer cell; NKT, natural killer T cell; pDC, plasmacytoid dendritic cell; RNP, ribonucleoprotein.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/144/26/10.1182_blood.2024024123/2/m_blood_bld-2024-024123-gr1i.jpeg?Expires=1769792159&Signature=FnT2Bv-pp9VNedeLH4YhsN33kynC41E-DVKfM3KxP~Wqsy54gYsGWDcqLVX7e4wqnGsnDJ9jvNFCNI3ObLgWaN8Ig4ZgP221YyzlCdgezoCE3lAAs6xn-bgeio1JKr8AL9FVizSmeDNQQe7oCURyDlPH3Rik7tUSblS1Cau8fMXZLk6g8JFE5NX7rjHR~HceMxuOw3BZYM-eOizIc9L6EO4LXmSntPxk1Bge151bwnAzH7bmx3bJlPCNqDKtC0TBncgeRGRFlITzR-95dckvaRjUONP-swAqZzMw7SeVDjqi61OxJIRnEfBLsPI1NDW0Nxou16rLp1PbiRTSmRhwIA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![AK2 deficiency upregulates purine biosynthesis. (A) Diagram of purine de novo and salvage synthesis pathways. One molecule of aspartate is used to synthesize AMP from IMP, and 1 molecule of NAD+ is used to synthesize GMP from IMP. Aspartate and NAD+ depletion leads to compromised AMP and GMP synthesis, respectively. (B) Frequency of granulocyte lineage–committed (HLA-DR–) cells at day 7 of in vitro NP differentiation, frequency of PMs, MCs, and NPs, and proliferation rate of AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– HSPCs transduced with lentiviral (LV) vectors expressing GLAST, mitoLbNOX, LbNOX, or split GFP (spGFP) control. AAVS1–/– ctrl LV, n = 6; AK2–/– ctrl LV, n = 10; AK2–/– GLAST LV, n = 7; AK2–/– mitoLbNOX LV, n = 5; AK2–/–LbNOX LV, n = 4. (C) Diagram of [amide-15N]-glutamine tracing into purine nucleotides. AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– HSPCs were differentiated in a nucleoside-free medium comprising MEMα without nucleosides, with 10% dialyzed fetal bovine serum, and traced with 2-mM [amide-15N]-glutamine in otherwise glutamine-free, nucleoside-free medium for 6 hours. Up to 2 15N (=m + 2) can be incorporated into AICAR, IMP, AMP, and ATP, and up to 3 15N (=m + 3) can be incorporated into GMP and GTP. (D-G) Relative abundance of AICAR (D), ATP (E), GTP (F), and IMP (G) isotopes in AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– PMs, MCs, and NPs, cultured and traced under conditions described in panel C. n = 6 for each condition. (H) PM, MC, and NP yield of AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– cells differentiated in MEMα medium with or without nucleosides. Bar plots represent means ± standard deviations of yield. n = 3 for each condition. (I) Diagram of [15N4]-hypoxanthine tracing into purine nucleotides. AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– HSCPs were differentiated in MyeloCult medium and traced with 10-mg/mL [15N4]-hypoxanthine in otherwise hypoxanthine-free medium for 6 hours. Up to 4 15N (=m + 4) can be incorporated into IMP, AMP, ATP, GMP, and GTP. (J-M) Relative abundance of AMP (J), ATP (K), GTP (L), and IMP (M) isotopes in AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– PMs, MCs, and NPs, cultured and traced under conditions described in panel I. n = 6 for each condition. (N) Western blot analysis of HPRT1 expression in unmanipulated HSPCs, PMs, MCs, and NPs, normalized to TP. From each sample, 25 μg of protein (measured by bicinchoninic acid) was diluted to 30 μL and mixed with 10 μL 4× Laemmli sample buffer; 20 μg protein (32 μL of the mixture) was loaded on a Mini-PROTEAN TGX precast AnykD or 10% gel for electrophoresis and blotting; 5 μg protein (8 μL of the same mixture) was loaded on a separate TGX Stain-Free gel to visualize TP. (O) HPRT1 enzymatic activity of AAVS1–/– (blue) and AK2–/– (red) MCs (n = 2 each) using the PRECICE HPRT assay kit. HPRT activity was continuously measured spectrophotometrically. Aqua and pink curves represent AAVS1–/– and AK2–/– MC protein samples without added hypoxanthine (n = 2 each). Lines and ribbons represent means ± standard deviations of absorbance at 340 nm at each time point. For panels B,H, bar plots represent means ± standard deviations. P values were determined by unpaired 2-tailed Student t test. For panels D-G,J-M, bar plots represent means ± standard deviations of relative abundance of isotopes. Statistical analysis was performed using the Omics Data Analyzer. ∗.01 < P < .05; ∗∗.001 < P < .01; ∗∗∗.0001 < P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/144/26/10.1182_blood.2024024123/2/m_blood_bld-2024-024123-gr5.jpeg?Expires=1769792159&Signature=f6Do8DrVSiOtcl9k69qlGHkPY8EpPGm9EN54waFHmrGPZO~DDPChHOHB9GJ8~bOKFNdg1YDDnYZyKOg~dAGJv-D0oFMrQEmm9KhCZQ62FPrCp2KGvcyQQ0bsFjFpa3LQst57Q0J28ez~KIwDECruiLDExDSoP8aGtiZY01P6PGC0jfokwiHgc5HTdpElWLQsZhJkhPQjstMt2rhKerYAfoABKR5LXIlllHV8zE8jTVFK4h3IipAEOvfStXXBBWWUcHIofyLiIQreYPTeTqJp0WwRF7YpUTxAsL-8oN1QpK3jdtojItkI4v9Hpzom9u8r5QTIK8J0yd7Pa2~OZCRl7A__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal