Key Points

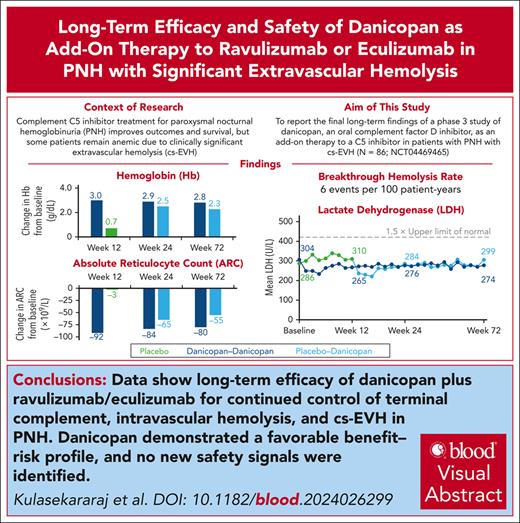

Danicopan + ravulizumab/eculizumab show long-term efficacy for continued control of terminal complement, intravascular hemolysis, and cs-EVH.

Danicopan demonstrated a favorable benefit-risk profile, with a breakthrough hemolysis rate of 6 events per 100 patient-years.

Visual Abstract

Complement C5 inhibitor treatment with ravulizumab or eculizumab for paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) improves outcomes and survival. Some patients remain anemic due to clinically significant extravascular hemolysis (cs-EVH; hemoglobin [Hb] ≤9.5 g/dL and absolute reticulocyte count [ARC] ≥120 × 109/L). In the phase 3 ALPHA trial, participants received oral factor D inhibitor danicopan (150 mg 3 times daily) or placebo plus ravulizumab or eculizumab during the 12-week, double-blind treatment period 1 (TP1); those receiving placebo switched to danicopan during the subsequent 12-week, open-label TP2 and continued during the 2-year long-term extension (LTE). There were 86 participants randomized in the study, of whom 82 entered TP2, and 80 entered LTE. The primary end point was met, with Hb improvements from baseline at week 12 (least squares mean change, 2.8 g/dL) with danicopan. For participants switching from placebo to danicopan at week 12, improvements in mean Hb were observed at week 24. Similar trends were observed for the proportion of participants with ≥2 g/dL Hb increase, ARC, proportion of participants achieving transfusion avoidance, and Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy–Fatigue scale scores. Improvements were maintained up to week 72. No new safety signals were observed. The breakthrough hemolysis rate was 6 events per 100 patient-years. These long-term data demonstrate sustained efficacy and safety of danicopan plus ravulizumab/eculizumab for continued control of terminal complement activity, intravascular hemolysis, and cs-EVH in PNH. This trial was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as #NCT04469465.

Introduction

Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) is a rare, chronic hematologic disorder characterized by uncontrolled terminal complement activation, leading to intravascular hemolysis (IVH), thrombosis, and premature mortality.1 Fatigue is the most commonly reported symptom of PNH1 and may lead to a significant negative impact on quality of life. To date, long-term survival and clinical outcomes have improved with standard-of-care therapies, complement C5 inhibitors ravulizumab or eculizumab, owing to control of terminal complement activity, IVH, and reduced rates of thrombosis.2-5

Clinically significant extravascular hemolysis (EVH; cs-EVH) may occur in patients despite the control of terminal complement activity and IVH with C5 inhibition.6,7 cs-EVH, defined as hemoglobin (Hb) ≤9.5 g/dL with an absolute reticulocyte count (ARC) ≥120 × 109/L, was reported in ∼20% of patients in a clinical trial evaluating ravulizumab and eculizumab in PNH (n = 188; NCT03056040).8 Surviving PNH red blood cells (RBCs) undergo C3 opsonization owing to the continued formation of the alternative pathway (AP) C3 convertase, subsequently leading to phagocytosis in the spleen or liver.9 In patients with PNH receiving C5 inhibitor therapy, C3 binding on RBCs is observed; however, the severity of cs-EVH does not appear to correlate with the actual level of C3 deposition.10 There is no established definition of cs-EVH due to limited sample sizes, inconsistent definitions among studies, and the use of varying C3 deposition detection assays.11-13 EVH is not expected to affect thrombosis risk and survival, but patients may require transfusions for anemia, affecting their quality of life.

In PNH, immediate, complete, and sustained inhibition of terminal complement is required to prevent IVH and maintain reduced risk of thromboembolic events, morbidity, and mortality.14 Missed treatment doses and complement-amplifying conditions may result in subtherapeutic plasma levels and lead to incomplete blockade and breakthrough IVH (BT-IVH), a temporary and sometimes severe loss of disease control.14-16 Although there is no formal definition, BT-IVH presents as the reappearance of clinical PNH symptoms associated with increases in lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) after previously controlled IVH.14,15 Fewer and less severe BT-IVH events have been observed with ravulizumab treatment than with eculizumab,17 owing to improved dosing and pharmacokinetics,18 along with immediate, complete, and sustained C5 inhibition.19

Factor D is the rate-limiting enzyme for the formation of C3 convertase, has the lowest plasma concentration of complement proteins, and has concentrations that remain stable during acute phase reactions, thus providing a strategic therapeutic target for AP pathway regulation.20,21 Danicopan is a first-in-class, oral factor D inhibitor indicated as an add-on therapy to ravulizumab or eculizumab for the treatment of signs and symptoms of EVH in adults with PNH.22 Efficacy and safety of danicopan as an add-on treatment to ravulizumab and eculizumab in patients with PNH and cs-EVH were assessed in the pivotal, phase 3 ALPHA clinical trial. In the primary evaluation period based on a prespecified interim efficacy analysis set of 63 participants (ie, ∼75% of the overall enrollment target), danicopan in combination with ravulizumab or eculizumab demonstrated clinically significant superiority compared with placebo at week 12 in all primary and key secondary end points.23 This report presents long-term efficacy and safety data from the double-blind treatment period 1 (TP1), open-label TP2, and the long-term extension (LTE) treatment period, based on all 86 randomized participants in the ALPHA trial, with 71 participants having >72 weeks of exposure to danicopan.

Methods

Study design

ALPHA (NCT04469465) was a phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial designed as a superiority study to investigate danicopan as an add-on treatment to background ravulizumab or eculizumab in participants with PNH and cs-EVH (the first participant was randomized on 6 January 2021). The trial was conducted internationally in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences International Ethical Guidelines as well as applicable International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use Good Clinical Practice Guidelines.23 The protocol was approved by the investigational review boards or institutional ethics committees of the trial sites. All participants provided written informed consent before participation.

The trial comprised a 45-day screening period followed by a 12-week double-blind TP1, a 12-week open-label TP2, and an LTE period (supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood website). Participants were randomized (2:1) to receive oral danicopan or placebo trice daily in addition to their background ravulizumab or eculizumab therapy during TP1. The initial dose of danicopan was 150 mg trice daily, which could then be escalated to a maximum of 200 mg trice daily based on clinical response, at the investigator’s discretion, after a minimum of 4 weeks at each dose level. At the end of TP1, participants receiving placebo were switched to danicopan treatment during TP2. Participants were offered the opportunity to continue treatment with danicopan at the same dose received at week 24 during the LTE. Upon completion of the first year of LTE (LTE1), participants had the choice to continue to the optional LTE2. Participants initially randomized to and continuing treatment with danicopan are referred to herein as the “danicopan-danicopan” arm, and participants initially randomized to placebo and then switched to danicopan are referred to herein as the “placebo-danicopan” arm.

Participants

Eligible participants included adults (aged ≥18 years) with PNH and cs-EVH (anemia [Hb ≤9.5 g/dL] with ARC ≥120 × 109/L) who were receiving ravulizumab or eculizumab treatment ≥6 months. Full inclusion and exclusion criteria have been published previously23; key inclusion criteria were platelet counts ≥30 × 103/μL without the need for platelet transfusions, absolute neutrophil counts ≥0.5 × 103/μL, and documentation of vaccination for Neisseria meningitidis within 3 years before or at the time of study. Participants were excluded if they had a history of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, had a known or suspected complement deficiency, had known active aplastic anemia, or had received an investigational agent other than C5 inhibitors (ravulizumab or eculizumab) within 30 days or 5 half-lives before study entry, whichever was greater.

Outcomes and assessments

The primary efficacy end point was change from baseline in Hb at 12 weeks of treatment and has been previously reported.23 Secondary end points included Hb over time, ARC, the percentage of C3 fragment deposition on PNH RBCs, LDH, the proportion of participants achieving transfusion avoidance, and Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy–Fatigue scale (FACIT-Fatigue) scores. Additional end points included the proportion of participants achieving ≥2 g/dL increase in Hb in the absence of transfusion, total bilirubin levels, and the number of RBC units transfused. All numeric end points were evaluated as absolute values over time and as changes from baseline; all binary end points were summarized with number and proportion of participants at week 12 (TP1 completion), week 24 (TP2 completion), and over the LTE up to week 72. Safety was evaluated and reported as treatment-emergent adverse events (AEs; TEAEs) and laboratory abnormalities, which were assessed throughout the study. Events of hemolysis, including breakthrough hemolysis (BTH), were reported as AEs based on the clinical judgment of the investigator.

Statistical analysis

Secondary efficacy end points were analyzed in all randomized participants who received ≥1 dose of study treatment. Actual values over the entire treatment period are reported for Hb, ARC, LDH, FACIT-Fatigue scores, and total bilirubin. Least squares mean (LSM) changes from baseline (standard error of the mean [SEM]) to week 12 and week 24 are presented for Hb, ARC, LDH, FACIT-Fatigue scores, and total bilirubin. LSM changes from baseline (SEM) were calculated using a mixed model for repeated measures that included the following observed randomization stratification factors: transfusion history (>2 or ≤2 transfusion episodes within 6 months of screening), screening Hb (<8.5 g/dL or ≥8.5 g/dL), baseline value, and study visit. The proportion of participants achieving transfusion avoidance and the proportion of participants achieving ≥2 g/dL increase in Hb in the absence of transfusion were calculated at week 12, week 24, and over the LTE. The mean (standard deviation [SD]) number of RBC units transfused was calculated before and after the initiation of danicopan treatment. Safety end points were assessed in the safety population (all participants who received ≥1 dose of study treatment) and were analyzed descriptively.

Results

Participant disposition and baseline characteristics

In total, 111 individuals were screened, 25 failed screening (supplemental Table 1), and 86 were randomized 2:1 to receive danicopan (n = 57 [66%]) or placebo (n = 29 [34%]). Of those randomized, 82 participants completed TP1 (danicopan-danicopan, n = 55; placebo-danicopan, n = 27), 80 participants completed TP2 (danicopan-danicopan, n = 54; placebo-danicopan, n = 26), and 71 and 70 participants completed LTE1 and LTE2, respectively (supplemental Figure 2). Baseline demographic and disease characteristics were similar between treatment arms (Table 1).

Baseline characteristics

| Characteristic . | Danicopan-danicopan (n = 57) . | Placebo-danicopan (n = 29) . |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (min-max), y | 52.8 (20-82) | 52.9 (29-77) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Female | 34 (59.6) | 20 (69.0) |

| Male | 23 (40.4) | 9 (31.0) |

| Hb, mean (SD), g/dL | 7.7 (0.9) | 7.9 (1.0) |

| ARC, mean (SD), ×109/L | 247.6 (97.2) | 222.7 (115.4) |

| LDH∗, mean (SD), U/L | 304.0 (123.6) | 286.4 (93.1) |

| FACIT-Fatigue scores, mean (SD) | 34.0 (11.3) | 31.7 (11.0) |

| Participants requiring transfusion instances 6 months before screening, n (%) | 56 (98.2) | 28 (96.6) |

| Number of transfusion instances 6 months before screening, median (range) | 2.0 (0-8) | 3.0 (0-8) |

| C5 inhibitor, n (%) | ||

| Ravulizumab | 36 (63.2) | 15 (51.7) |

| Eculizumab | 21 (36.8) | 14 (48.3) |

| Duration of C5 inhibitor therapy†, mean (SD), y | 5.1 (3.6) | 6.1 (4.2) |

| Duration of disease‡, mean (SD), y | 10.0 (9.7) | 11.0 (9.5) |

| Proportion of type III PNH RBC population§, mean (SD), % | 57.6 (26.1) | 53.7 (28.2) |

| C3 deposition on type III PNH RBCs§, mean (SD), % | 33.4 (18.2) | 30.4 (16.0) |

| Medical history of aplastic anemia||, n (%) | 18 (31.6) | 8 (27.6) |

| Medical history of myelodysplastic syndrome||, n (%) | 2 (3.5) | 3 (10.3) |

| Characteristic . | Danicopan-danicopan (n = 57) . | Placebo-danicopan (n = 29) . |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (min-max), y | 52.8 (20-82) | 52.9 (29-77) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Female | 34 (59.6) | 20 (69.0) |

| Male | 23 (40.4) | 9 (31.0) |

| Hb, mean (SD), g/dL | 7.7 (0.9) | 7.9 (1.0) |

| ARC, mean (SD), ×109/L | 247.6 (97.2) | 222.7 (115.4) |

| LDH∗, mean (SD), U/L | 304.0 (123.6) | 286.4 (93.1) |

| FACIT-Fatigue scores, mean (SD) | 34.0 (11.3) | 31.7 (11.0) |

| Participants requiring transfusion instances 6 months before screening, n (%) | 56 (98.2) | 28 (96.6) |

| Number of transfusion instances 6 months before screening, median (range) | 2.0 (0-8) | 3.0 (0-8) |

| C5 inhibitor, n (%) | ||

| Ravulizumab | 36 (63.2) | 15 (51.7) |

| Eculizumab | 21 (36.8) | 14 (48.3) |

| Duration of C5 inhibitor therapy†, mean (SD), y | 5.1 (3.6) | 6.1 (4.2) |

| Duration of disease‡, mean (SD), y | 10.0 (9.7) | 11.0 (9.5) |

| Proportion of type III PNH RBC population§, mean (SD), % | 57.6 (26.1) | 53.7 (28.2) |

| C3 deposition on type III PNH RBCs§, mean (SD), % | 33.4 (18.2) | 30.4 (16.0) |

| Medical history of aplastic anemia||, n (%) | 18 (31.6) | 8 (27.6) |

| Medical history of myelodysplastic syndrome||, n (%) | 2 (3.5) | 3 (10.3) |

Max, maximum; min, minimum.

LDH reference range, 135 to 330 U/L.

Duration from initial C5 inhibitor therapy to first dose of study drug.

Duration from diagnosis to informed consent.

CD55/CD59–.

Collected as part of participant medical history before enrollment.

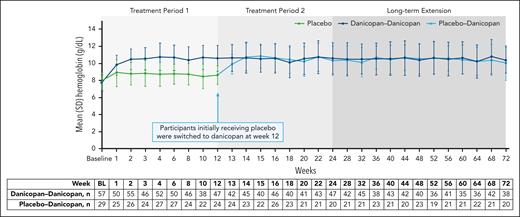

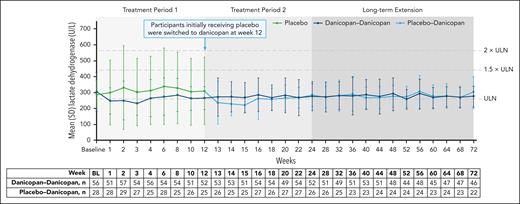

Efficacy

Efficacy was shown for the primary end point of change from baseline in Hb levels in the danicopan arm at week 12 in the current analysis set of all randomized participants (N = 86), which was maintained at week 24 (Table 2). Minimal changes in Hb levels were observed from baseline to week 12 in those receiving placebo but improved by week 24 after switching to danicopan. Absolute Hb values were higher in participants receiving danicopan than those receiving placebo at week 12, and after initiating treatment with danicopan in those receiving placebo, values in both arms became similar by week 14 and were maintained up to week 72 (Figure 1). Importantly, mean LDH levels remained well controlled (<1.5× upper limit of normal [ULN]) in both treatment arms from baseline to week 72 (Figure 2).

Efficacy end points at week 12 and week 24 (MMRM analysis)

| Change from baseline . | Danicopan-danicopan . | Placebo-danicopan∗ . | Treatment difference (danicopan-danicopan and placebo-danicopan) . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week 12 . | Week 24 . | Week 12 . | Week 24 . | Week 12 . | P value . | |

| Hb levels, g/dL,† LSM (SEM) | 2.8 (0.2) | 2.9 (0.3) | 0.5 (0.3) | 2.3 (0.3) | 2.3 (0.4) | <.0001 |

| LDH, U/L,‡ LSM (SEM) | –25.6 (7.9) | –23.6 (11.3) | –16.9 (11.4) | 1.0 (12.4) | –8.7 (13.8) | .5306 |

| ARC, ×109/L,§ LSM (SEM) | –92.5 (8.2) | –87.9 (7.8) | –0.8 (11.8) | –53.6 (11.7) | –91.7 (14.3) | <.0001 |

| Total bilirubin||, μmol/L, LSM (SEM) | –11.6 (1.5) | –11.0 (2.2) | –1.4 (2.2) | –6.3 (2.9) | –10.1 (2.6) | .0002 |

| FACIT-Fatigue scores,¶ LSM (SEM) | 8.1 (0.9) | 6.2 (1.0) | 2.4 (1.3) | 5.6 (1.9) | 5.8 (1.6) | .0004 |

| Change from baseline . | Danicopan-danicopan . | Placebo-danicopan∗ . | Treatment difference (danicopan-danicopan and placebo-danicopan) . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week 12 . | Week 24 . | Week 12 . | Week 24 . | Week 12 . | P value . | |

| Hb levels, g/dL,† LSM (SEM) | 2.8 (0.2) | 2.9 (0.3) | 0.5 (0.3) | 2.3 (0.3) | 2.3 (0.4) | <.0001 |

| LDH, U/L,‡ LSM (SEM) | –25.6 (7.9) | –23.6 (11.3) | –16.9 (11.4) | 1.0 (12.4) | –8.7 (13.8) | .5306 |

| ARC, ×109/L,§ LSM (SEM) | –92.5 (8.2) | –87.9 (7.8) | –0.8 (11.8) | –53.6 (11.7) | –91.7 (14.3) | <.0001 |

| Total bilirubin||, μmol/L, LSM (SEM) | –11.6 (1.5) | –11.0 (2.2) | –1.4 (2.2) | –6.3 (2.9) | –10.1 (2.6) | .0002 |

| FACIT-Fatigue scores,¶ LSM (SEM) | 8.1 (0.9) | 6.2 (1.0) | 2.4 (1.3) | 5.6 (1.9) | 5.8 (1.6) | .0004 |

All measures were significantly improved with danicopan compared with placebo at week 12. Randomization was stratified by transfusion history (>2 or ≤2 transfusions within 6 months of screening), screening Hb (<8.5 g/dL or ≥8.5 g/dL), baseline Hb, and study visit Hb.

MMRM, mixed model for repeated measures.

After week 12, participants receiving placebo were switched to danicopan treatment.

Week 12: danicopan, n = 57; placebo, n = 28 and week 24: danicopan, n = 50; placebo, n = 26.

Week 12: danicopan, n = 56; placebo, n = 28 and week 24: danicopan, n = 54; placebo, n = 26.

Week 12: danicopan, n = 57; placebo, n = 26 and week 24: danicopan, n = 50; placebo, n = 26.

Week 12: danicopan, n = 57; placebo, n = 29 and week 24: danicopan, n = 55; placebo, n = 27.

Week 12: danicopan, n = 56; placebo, n = 28 and week 24: danicopan, n = 52; placebo, n = 27.

Change in Hb across 72 weeks of treatment. Summary of actual Hb values, irrespective of transfusions, over 72 weeks of treatment with danicopan as an add-on therapy. Mean (SD) values of Hb (g/dL) for treatment groups are plotted across each time point, and corresponding n values are shown in the table below. BL, baseline.

Change in Hb across 72 weeks of treatment. Summary of actual Hb values, irrespective of transfusions, over 72 weeks of treatment with danicopan as an add-on therapy. Mean (SD) values of Hb (g/dL) for treatment groups are plotted across each time point, and corresponding n values are shown in the table below. BL, baseline.

Change in LDH across 72 weeks of treatment. Summary of actual values of LDH over 72 weeks of treatment with danicopan as an add-on therapy. Mean (SD) values of LDH (U/L) for treatment groups are plotted across each time point, and corresponding n value are shown in the table below. BL, baseline.

Change in LDH across 72 weeks of treatment. Summary of actual values of LDH over 72 weeks of treatment with danicopan as an add-on therapy. Mean (SD) values of LDH (U/L) for treatment groups are plotted across each time point, and corresponding n value are shown in the table below. BL, baseline.

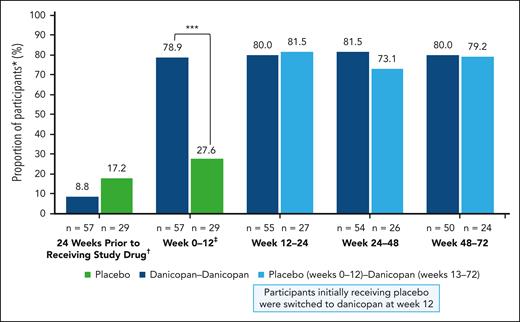

At week 12, 54.4% of participants in the danicopan-danicopan arm exhibited clinically meaningful increases in Hb (≥2 g/dL) in the absence of transfusion, which was maintained at week 72 (53.7%); this was observed in 29.6% and 46.2% of participants in the placebo-danicopan arm at week 24 and week 72, respectively, upon switching to danicopan at week 12. In the 24 weeks before receiving the study drug, 8.8% of participants in the danicopan-danicopan arm and 17.2% of participants in the placebo-danicopan arm had not received a transfusion. In the danicopan-danicopan arm, the proportion of participants achieving transfusion avoidance increased from baseline to week 12 (78.9%) and was maintained at week 24 (80.0%), week 48 (81.5%), and week 72 (80.0%). Although there was no improvement in the proportion of participants achieving transfusion avoidance at week 12 with placebo (27.6%), a greater proportion achieved transfusion avoidance at weeks 24 (81.5%), 48 (73.1%), and 72 (79.2%), after switching to danicopan (Figure 3). Overall, 54 of 84 participants (64.3%) treated with danicopan achieved transfusion avoidance throughout the entire study. The mean number of transfused RBC units decreased with 12 weeks of danicopan treatment in the danicopan-danicopan arm (12 weeks before initiation, 2.0; 12 weeks after initiation, 0.7) and placebo-danicopan arm (12 weeks before danicopan initiation, 2.3; 12 weeks after danicopan initiation, 0.6). In participants initially randomized to danicopan, treatment for 24 weeks was associated with a –2.7 reduction in the mean number of transfused RBC units (24 weeks before initiation, 4.0; 24 weeks after initiation, 1.3).

Proportion of participants avoiding transfusions while receiving danicopan as an add-on therapy. The number of participants achieving transfusion avoidance are expressed as a percent relative to the total participants in the corresponding treatment group. Corresponding n values are shown at the base of each data point. ∗∗∗P ≤ .001. ∗Defined as participants who remain transfusion free and did not require a transfusion per protocol-specified guidelines. †Participants who were RBC transfusion free during the 24 weeks before receiving study drug. ‡P values are only available for week 12 or TP1.

Proportion of participants avoiding transfusions while receiving danicopan as an add-on therapy. The number of participants achieving transfusion avoidance are expressed as a percent relative to the total participants in the corresponding treatment group. Corresponding n values are shown at the base of each data point. ∗∗∗P ≤ .001. ∗Defined as participants who remain transfusion free and did not require a transfusion per protocol-specified guidelines. †Participants who were RBC transfusion free during the 24 weeks before receiving study drug. ‡P values are only available for week 12 or TP1.

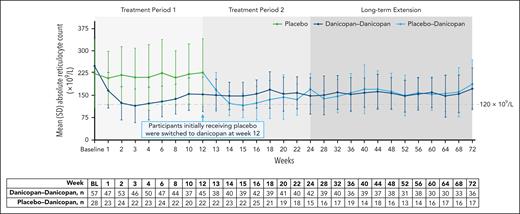

Improvements in ARC were observed from baseline to week 12 and were maintained at week 24 in the danicopan-danicopan arm (Table 2). In the placebo arm, changes from baseline to week 12 in ARC were minimal with placebo; improvements were observed at week 24 after transitioning to treatment with danicopan. Actual ARC values became comparable across treatment arms by week 13 after initiating danicopan treatment in the placebo-danicopan arm and were maintained up to week 72 (Figure 4). The mean (SD) percentage of C3 fragment deposition on PNH type 3 RBCs decreased from baseline to week 12 and was maintained to week 72 in the danicopan-danicopan arm (supplemental Figure 3). In the placebo-danicopan arm, the percentage of C3 fragment deposition was reduced after treatment with danicopan; at week 24, values in the placebo-danicopan arm with danicopan treatment were similar to those observed in the danicopan-danicopan arm, which continued through week 72. Treatment with danicopan was associated with improved total bilirubin levels from baseline to week 12 (LSM change; danicopan-danicopan arm, –11.6 [SEM, 1.5]; placebo-danicopan arm, –1.4 [SEM, 2.2]) and at week 24 (danicopan-danicopan arm, −11.0 [SEM, 2.2]; placebo-danicopan arm, −6.3 [SEM, 2.9]) for the danicopan-danicopan and placebo-danicopan arms, respectively (Table 2). Improvements in total bilirubin levels were maintained up to week 72 for both treatment arms (supplemental Figure 4).

Summary of actual ARCs over 72 weeks of treatment. Mean (SD) values of ARCs (×109/L) for treatment groups are plotted across each time point, and corresponding n values are shown in the table below. BL, baseline.

Summary of actual ARCs over 72 weeks of treatment. Mean (SD) values of ARCs (×109/L) for treatment groups are plotted across each time point, and corresponding n values are shown in the table below. BL, baseline.

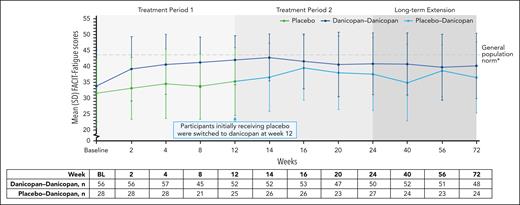

Clinically meaningful improvements in FACIT-Fatigue scores were observed at week 12 in the danicopan-danicopan arm and maintained at week 24 (Table 2). Participants in the placebo arm exhibited minimal changes in FACIT-Fatigue scores from baseline to week 12 with placebo; however, clinically meaningful improvements were seen at week 24 after the initiation of danicopan. Actual scores remained lower in the placebo-danicopan arm than in the danicopan-danicopan arm at week 12 but became similar by week 16 and were maintained up to week 72 (Figure 5).

Summary of FACIT-Fatigue scores over 72 weeks of treatment. Mean (SD) FACIT-Fatigue scores are plotted across each time point, and corresponding n values are shown in the table below. ∗Mean FACIT-Fatigue scores among the general population have been reported to be ∼43.5 to 43.6.24,25 BL, baseline.

Safety

Of the 84 participants exposed to danicopan, the median total treatment duration was 508 days (range, 44-785), and 73.8% of participants reached a maximum dose of 200 mg. The mean study drug adherence of all participants receiving danicopan based on dose was 97.1% (SD, 9.2). Overall, 98.8% of participants experienced ≥1 TEAE with danicopan treatment (Table 3). Serious AEs considered related to danicopan by investigators were reported in 1 participant during TP1 (bilirubin increase, 1 event; pancreatitis, 1 event) and 1 participant during TP2 (headache, 1 event); no treatment-related serious AEs were observed in the LTE. Over the entire study period, withdrawal of danicopan treatment was reported in 6 participants (danicopan-danicopan arm, n = 4; placebo-danicopan arm, n = 2), owing to 8 TEAEs that included pancreatitis (TP1), increased alanine aminotransferase (ALT; TP1), increased aspartate aminotransferase (TP1), increased blood bilirubin (TP1), increased hepatic enzymes (TP1), cholecystitis (TP2), aplastic anemia (LTE), and abnormal hepatic function (LTE; supplemental Table 2). The events of cholecystitis and aplastic anemia were considered unrelated to danicopan treatment. BTH was reported by investigators in 5 participants (7 events) over the entire treatment period (6 events per 100 patient-years; Table 4). All BTH events were considered unrelated to danicopan treatment and were resolved rapidly without trial discontinuation, dose adjustment, or need for transfusion. Of the 4 BTH events with Hb data available at the exact time of the event, all Hb levels were considered low, providing further evidence of the occurrence of BTH.15,17 Only 1 event was associated with LDH ≥2 × ULN (2.2 × ULN) and decreased Hb, which was temporarily associated with COVID-19 infection. Concurrent anemia and fever were each observed with 1 BTH event. In 1 participant who reported 3 BTH events, concurrent AEs observed included skin infection and food poisoning. Over the study period, no meningococcal infections or discontinuations due to hemolysis were reported. One death due to severe acute pneumonia in a participant with aplastic anemia receiving cyclosporin occurred during LTE. No pathogen was identified, and the death was determined to be unrelated to the study treatment by the investigator.

Overview of TEAEs with danicopan treatment over the entire trial (safety population)

| TEAE . | Danicopan-danicopan (n = 57) . | Placebo-danicopan∗ (n = 27) . | Total (N = 84) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any TEAE | 56 (98.2), 503 | 27 (100), 273 | 83 (98.8), 776 |

| Common TEAEs (≥5% of total population) | |||

| COVID-19 | 15 (26.3), 15 | 11 (40.7), 11 | 26 (31.0), 26 |

| Pyrexia | 19 (33.3), 30 | 3 (11.1), 5 | 22 (26.2), 35 |

| Headache | 15 (26.3), 22 | 3 (11.1), 3 | 18 (21.4), 25 |

| Nausea | 10 (17.5), 12 | 3 (11.1), 6 | 13 (15.5), 18 |

| Diarrhea | 8 (14.0), 13 | 4 (14.8), 9 | 12 (14.3), 22 |

| Asthenia | 6 (10.5), 6 | 5 (18.5), 12 | 11 (13.1), 18 |

| Fatigue | 8 (14.0), 11 | 2 (7.4), 2 | 10 (11.9), 13 |

| Arthralgia | 7 (12.3), 8 | 3 (11.1), 4 | 10 (11.9), 12 |

| Urinary tract infection | 7 (12.3), 8 | 3 (11.1), 4 | 10 (11.9), 12 |

| Nasopharyngitis | 7 (12.3), 9 | 1 (3.7), 1 | 8 (9.5), 10 |

| Anemia | 6 (10.5), 7 | 1 (3.7), 3 | 7 (8.3), 10 |

| Vomiting | 6 (10.5), 7 | 1 (3.7), 3 | 7 (8.3), 10 |

| Hemolysis | 4 (7.0), 4 | 3 (11.1), 6 | 7 (8.3), 10 |

| Constipation | 3 (5.3), 3 | 4 (14.8), 5 | 7 (8.3), 8 |

| Back pain | 4 (7.0), 4 | 3 (11.1), 3 | 7 (8.3), 7 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 3 (5.3), 3 | 3 (11.1), 13 | 6 (7.1), 16 |

| Pain in extremity | 6 (10.5), 9 | 0 | 6 (7.1), 9 |

| Abdominal pain | 3 (5.3), 3 | 3 (11.1), 4 | 6 (7.1), 7 |

| Cough | 5 (8.8), 6 | 1 (3.7), 1 | 6 (7.1), 7 |

| Dizziness | 5 (8.8), 5 | 1 (3.7), 1 | 6 (7.1), 6 |

| Insomnia | 3 (5.3), 3 | 3 (11.1), 3 | 6 (7.1), 6 |

| Myalgia | 4 (7.0), 7 | 1 (3.7), 1 | 5 (6.0), 8 |

| BTH | 5 (8.8), 7 | 0 | 5 (6.0), 7 |

| Dyspnea | 3 (5.3), 4 | 2 (7.4), 2 | 5 (6.0), 6 |

| Neutropenia | 4 (7.0), 5 | 1 (3.7), 1 | 5 (6.0), 6 |

| Dark urine | 3 (5.3), 3 | 2 (7.4), 2 | 5 (6.0), 5 |

| Dyspepsia | 1 (1.8), 1 | 4 (14.8), 4 | 5 (6.0), 5 |

| Oropharyngeal pain | 5 (8.8), 5 | 0 | 5 (6.0), 5 |

| TEAEs by relationship | |||

| Related | 13 (22.8), 43 | 9 (33.3), 28 | 22 (26.2), 71 |

| Not related | 55 (96.5), 460 | 26 (96.3), 245 | 81 (96.4), 705 |

| SAEs by relationship | |||

| Related | 1 (1.8), 2 | 1 (3.7), 1 | 2 (2.4), 3 |

| Not related | 11 (19.3), 20 | 9 (33.3), 20 | 20 (23.8), 40 |

| Grade ≥3 TEAEs | 25 (43.9), 53 | 15 (55.6), 43 | 40 (47.6), 96 |

| AESI | |||

| Meningococcal infections | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Liver enzyme elevations | 11 (19.3), 21 | 4 (14.8), 4 | 15 (17.9), 25 |

| TEAE leading to withdrawal of study drug | 4 (7.0), 6 | 2 (7.4), 2 | 6 (7.1), 8 |

| TEAE leading to death | 0 | 1 (3.8), 1 | 1 (3.8), 1 |

| TEAE . | Danicopan-danicopan (n = 57) . | Placebo-danicopan∗ (n = 27) . | Total (N = 84) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any TEAE | 56 (98.2), 503 | 27 (100), 273 | 83 (98.8), 776 |

| Common TEAEs (≥5% of total population) | |||

| COVID-19 | 15 (26.3), 15 | 11 (40.7), 11 | 26 (31.0), 26 |

| Pyrexia | 19 (33.3), 30 | 3 (11.1), 5 | 22 (26.2), 35 |

| Headache | 15 (26.3), 22 | 3 (11.1), 3 | 18 (21.4), 25 |

| Nausea | 10 (17.5), 12 | 3 (11.1), 6 | 13 (15.5), 18 |

| Diarrhea | 8 (14.0), 13 | 4 (14.8), 9 | 12 (14.3), 22 |

| Asthenia | 6 (10.5), 6 | 5 (18.5), 12 | 11 (13.1), 18 |

| Fatigue | 8 (14.0), 11 | 2 (7.4), 2 | 10 (11.9), 13 |

| Arthralgia | 7 (12.3), 8 | 3 (11.1), 4 | 10 (11.9), 12 |

| Urinary tract infection | 7 (12.3), 8 | 3 (11.1), 4 | 10 (11.9), 12 |

| Nasopharyngitis | 7 (12.3), 9 | 1 (3.7), 1 | 8 (9.5), 10 |

| Anemia | 6 (10.5), 7 | 1 (3.7), 3 | 7 (8.3), 10 |

| Vomiting | 6 (10.5), 7 | 1 (3.7), 3 | 7 (8.3), 10 |

| Hemolysis | 4 (7.0), 4 | 3 (11.1), 6 | 7 (8.3), 10 |

| Constipation | 3 (5.3), 3 | 4 (14.8), 5 | 7 (8.3), 8 |

| Back pain | 4 (7.0), 4 | 3 (11.1), 3 | 7 (8.3), 7 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 3 (5.3), 3 | 3 (11.1), 13 | 6 (7.1), 16 |

| Pain in extremity | 6 (10.5), 9 | 0 | 6 (7.1), 9 |

| Abdominal pain | 3 (5.3), 3 | 3 (11.1), 4 | 6 (7.1), 7 |

| Cough | 5 (8.8), 6 | 1 (3.7), 1 | 6 (7.1), 7 |

| Dizziness | 5 (8.8), 5 | 1 (3.7), 1 | 6 (7.1), 6 |

| Insomnia | 3 (5.3), 3 | 3 (11.1), 3 | 6 (7.1), 6 |

| Myalgia | 4 (7.0), 7 | 1 (3.7), 1 | 5 (6.0), 8 |

| BTH | 5 (8.8), 7 | 0 | 5 (6.0), 7 |

| Dyspnea | 3 (5.3), 4 | 2 (7.4), 2 | 5 (6.0), 6 |

| Neutropenia | 4 (7.0), 5 | 1 (3.7), 1 | 5 (6.0), 6 |

| Dark urine | 3 (5.3), 3 | 2 (7.4), 2 | 5 (6.0), 5 |

| Dyspepsia | 1 (1.8), 1 | 4 (14.8), 4 | 5 (6.0), 5 |

| Oropharyngeal pain | 5 (8.8), 5 | 0 | 5 (6.0), 5 |

| TEAEs by relationship | |||

| Related | 13 (22.8), 43 | 9 (33.3), 28 | 22 (26.2), 71 |

| Not related | 55 (96.5), 460 | 26 (96.3), 245 | 81 (96.4), 705 |

| SAEs by relationship | |||

| Related | 1 (1.8), 2 | 1 (3.7), 1 | 2 (2.4), 3 |

| Not related | 11 (19.3), 20 | 9 (33.3), 20 | 20 (23.8), 40 |

| Grade ≥3 TEAEs | 25 (43.9), 53 | 15 (55.6), 43 | 40 (47.6), 96 |

| AESI | |||

| Meningococcal infections | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Liver enzyme elevations | 11 (19.3), 21 | 4 (14.8), 4 | 15 (17.9), 25 |

| TEAE leading to withdrawal of study drug | 4 (7.0), 6 | 2 (7.4), 2 | 6 (7.1), 8 |

| TEAE leading to death | 0 | 1 (3.8), 1 | 1 (3.8), 1 |

Data are presented as the number of patients who had an AE (with the percentage of patients in parentheses) followed by the total number of events.

AESI, AE of special interest; SAE, serious AE.

In the placebo-danicopan arm, only TEAEs that occurred after switching to danicopan were included.

Clinical details on TEAEs of BTH over the entire trial

| Participant . | Reported BTH event . | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase (start day/end day)∗ . | Treatment arm (dose) . | C5 inhibitor (dose) . | Severity grade† . | Hb before BTH event, g/dL . | Hb during BTH event, g/dL . | Hb after BTH event, g/dL . | LDH before BTH event, U/L . | LDH at time of BTH event, U/L . | Related to danicopan . | Outcome . | Need for transfusion . | Concurrent AEs . | |

| Male, 54 y | TP2 (127/156) | Danicopan-danicopan (200 mg) | Ravulizumab (3300 mg) | 3 | 11.0 | 7.3 | 13.6 | 447.0 | 336.0 | No | No dose change, recovered/resolved | No | Anemia |

| Male, 41 y | LTE (192/225) | Danicopan-danicopan (200 mg) | Ravulizumab (3300 mg) | 1 | 12.1 | 9.2 | 10.7 | 307.0 | 632.0‡ | No | No dose change, recovered/resolved | No | COVID-19 infection |

| Male, 58 y | LTE (393/424) | Danicopan-danicopan (200 mg) | Ravulizumab (3300 mg) | 1 | NA§ | 7.4 | NA§ | 234.0 | 310.0 | No | No dose change, recovered/resolved | No | — |

| Female, 82 y | TP2 (113/127) | Danicopan-danicopan (200 mg) | Ravulizumab (3000 mg) | 2 | 9.5 | 8.7 | 9.3 | 289.0 | 639.0 | No | No dose change, recovered/resolved | No | Skin infection |

| LTE (290/291) | 2 | 10.1 | NA§ | 8.6 | 516.0 | NA§ | No | No dose change, recovered/resolved | No | Food poisoning | |||

| LTE (505/505) | 2 | NA§ | NA§ | NA§ | 286.0 | 387.0 | No | No dose change, recovered/resolved | No | — | |||

| Male, 40 y | LTE (218/219) | Danicopan-danicopan (200 mg) | Ravulizumab (3300 mg) | 1 | 14.8 | NA§ | 13.2 | 255.0 | NA§ | No | No dose change, recovered/resolved | No | Fever |

| Participant . | Reported BTH event . | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase (start day/end day)∗ . | Treatment arm (dose) . | C5 inhibitor (dose) . | Severity grade† . | Hb before BTH event, g/dL . | Hb during BTH event, g/dL . | Hb after BTH event, g/dL . | LDH before BTH event, U/L . | LDH at time of BTH event, U/L . | Related to danicopan . | Outcome . | Need for transfusion . | Concurrent AEs . | |

| Male, 54 y | TP2 (127/156) | Danicopan-danicopan (200 mg) | Ravulizumab (3300 mg) | 3 | 11.0 | 7.3 | 13.6 | 447.0 | 336.0 | No | No dose change, recovered/resolved | No | Anemia |

| Male, 41 y | LTE (192/225) | Danicopan-danicopan (200 mg) | Ravulizumab (3300 mg) | 1 | 12.1 | 9.2 | 10.7 | 307.0 | 632.0‡ | No | No dose change, recovered/resolved | No | COVID-19 infection |

| Male, 58 y | LTE (393/424) | Danicopan-danicopan (200 mg) | Ravulizumab (3300 mg) | 1 | NA§ | 7.4 | NA§ | 234.0 | 310.0 | No | No dose change, recovered/resolved | No | — |

| Female, 82 y | TP2 (113/127) | Danicopan-danicopan (200 mg) | Ravulizumab (3000 mg) | 2 | 9.5 | 8.7 | 9.3 | 289.0 | 639.0 | No | No dose change, recovered/resolved | No | Skin infection |

| LTE (290/291) | 2 | 10.1 | NA§ | 8.6 | 516.0 | NA§ | No | No dose change, recovered/resolved | No | Food poisoning | |||

| LTE (505/505) | 2 | NA§ | NA§ | NA§ | 286.0 | 387.0 | No | No dose change, recovered/resolved | No | — | |||

| Male, 40 y | LTE (218/219) | Danicopan-danicopan (200 mg) | Ravulizumab (3300 mg) | 1 | 14.8 | NA§ | 13.2 | 255.0 | NA§ | No | No dose change, recovered/resolved | No | Fever |

TEAEs were determined and assessed by investigators. Data are based on final data cutoff as of 22 March 2024.

NA, not available.

The start day indicates the first report of BTH, and the end day indicates when data of normalization were available. Notably, the end day does not necessarily represent the day data normalized.

Severity grade was based on version 5.0 of the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events.

Participant had an LDH value of 2.2 × ULN. The laboratory threshold for LDH ULN was 281 U/L and 330 U/L for male and female participants, respectively.

No value available at the exact time of the event.

Discussion

The phase 3, randomized, placebo-controlled ALPHA trial evaluated the efficacy and safety of danicopan as an add-on therapy in participants with PNH who have severe cs-EVH while receiving stable background therapy with ravulizumab or eculizumab. This study enrolled a population of patients with PNH and severe cs-EVH who had low Hb, elevated ARC, and fatigue at baseline. Before enrollment, almost all participants required regular RBC transfusions. In addition, ∼30% and 6% of participants had a medical history of aplastic anemia and myelodysplastic syndrome, respectively. However, eligible participants were required to have an ARC ≥120 × 109/L, which would imply that participants with active forms of these conditions were unlikely to be included, because active aplastic anemia or myelodysplastic syndrome typically result in low ARC owing to inadequate blood cell production by the bone marrow.26,27 The primary end point of change from baseline to week 12 in Hb was met, showing statistically significant and clinically relevant efficacy with danicopan vs placebo in this population.23 Danicopan treatment was associated with increased transfusion avoidance, reduction in the number of transfused RBC units, maintenance of IVH blockade, and improved fatigue through week 72. Safety data were consistent with those previously reported for the primary evaluation period23; no new safety signals were observed in TP2 or during the LTE. No meningococcal infections were reported for the entire duration of treatment with danicopan in the trial. The 1 death reported during this study was considered unrelated to study treatment. Results reported herein confirm those of the primary efficacy analysis and show that these improvements are maintained long term in a larger cohort (86 participants vs 63 participants), highlighting the ability of danicopan to address hematologic abnormalities associated with severe cs-EVH. These findings represent, to our knowledge, the first long-term data from a phase 3 trial demonstrating the efficacy of factor D inhibition with danicopan in combination with ravulizumab or eculizumab for addressing IVH and cs-EVH, while maintaining control of terminal complement activity in PNH.

Over the long-term safety period, the incidence of TEAEs associated with hepatic abnormalities decreased over time with danicopan treatment. Most ALT, aspartate aminotransferase, and total bilirubin elevations ranged between >3 × ULN and ≤5 × ULN, with no ALT elevations >10 × ULN or dose adjustments required. In participants with BTH events, most events were mild to moderate in severity, with LDH levels <2 × ULN, and all were resolved without the need for transfusions or a change in regimen. Only 1 BTH event was associated with LDH ≥2 × ULN (2.2 × ULN), concomitant with a COVID-19 infection.

Therapy regimens that can adequately control terminal complement activity and thereby IVH, organ damage, and thrombosis risk, as well as address cs-EVH in the small subset of patients who develop it, are of interest. In patients with PNH, uncontrolled terminal complement activity causes IVH and an increased risk of organ damage and thromboembolic events, including BT-IVH, which can occur with any complement inhibitor and can be due to pharmacokinetic- or pharmacodynamic-related causes.9,14,15 In this context, AP pathway inhibition, such as with a factor D inhibitor in combination with the safety net of ravulizumab or eculizumab, could prevent or reduce terminal complement activity, IVH, and cs-EVH. Data from the present trial provide further support for this hypothesis, because dual treatment with ravulizumab or eculizumab plus danicopan resulted in control of both IVH and cs-EVH.

Recent advances have led to the development of alternative therapeutic agents that target complement-mediated hemolysis and have shown efficacy in terms of normalization of LDH and improvement in Hb and transfusion needs.28-31 However, emerging evidence indicates that BT-IVH may be more of a concern with proximal complement monotherapy. Incomplete C3 inhibition with proximal inhibition catalyzes the cleavage of multiple C5 molecules, resulting in the formation of many membrane attack complexes. One membrane attack complex is formed per molecule of C5 that escapes blockade with terminal inhibition by C5 inhibitors, likely limiting BT-IVH9; this theory is further supported by long-term data from 2 studies of ravulizumab, in which <10% of patients experienced BT-IVH.3 Additionally, increased levels of surviving circulating PNH RBCs have been observed with proximal inhibition compared with terminal inhibition,9 potentially increasing the risk of severe hemolysis events during instances of incomplete complement control, which can have clinically relevant consequences.

In the phase 3 PEGASUS trial, ∼19.5% of participants experienced hemolysis with pegcetacoplan monotherapy over 48 weeks of follow-up.16 BTH events were reported in 7.4% of participants receiving iptacopan monotherapy over the 48-week follow-up period of the phase 3 APPLY-PNH trial (NCT04558918), all of which resolved without adjustment of iptacopan dose.31 In ALPHA, BTH was reported in ∼6.0% of participants receiving danicopan, at an adjusted exposure rate of 6 BTH events per 100 patient-years over the trial duration, including long-term follow-up. All BTH events resolved without dose adjustment or need for transfusions. Findings from the ALPHA trial suggest that controlling the complement AP with danicopan in combination with ravulizumab or eculizumab may reduce both the rate and severity of BT-IVH in those patients with PNH with cs-EVH. Although BT-IVH remains a possibility with dual proximal and terminal inhibition (eg, due to a missed dose or complement-amplifying conditions), its clinical relevance in our trial appears limited compared with observed rates with monotherapy using proximal inhibitors. Similarly, observed low-grade residual EVH, demonstrated by detectable C3 deposition and mild reticulocytosis in some participants, was clinically negligible as significant clinical improvement from baseline in Hb, ARC, transfusion avoidance, and FACIT-Fatigue scores were shown. Long-term and real-world data using consistent definitions of BT-IVH and cs-EVH are needed to corroborate these findings outside the trial setting. Transfusion requirements may differ among patients with PNH; patients with concomitant bone marrow failure may be unable to completely avoid transfusions.32-34 Over the long-term follow-up in PEGASUS, >70% of participants receiving pegcetacoplan remained transfusion free at week 48.16 Transfusion avoidance was achieved in >90% of participants receiving iptacopan at week 48 in APPLY-PNH.31 In ALPHA, ∼80% of participants receiving danicopan achieved transfusion avoidance at week 72. Notably, participants in the ALPHA trial had severe cs-EVH at enrollment, with a mean Hb level of ∼7.8 g/dL at baseline, and >97% required transfusions in the 6 months before screening. Thus, cross-study comparisons must be interpreted with caution due to varying patient populations with differing baseline Hb levels, transfusion needs, and trial methodologies, including differing trial definitions of BT-IVH.15

A clinically important change on the validated FACIT-Fatigue scale for patients with PNH was defined as 5 points.35 Using this criterion, clinically meaningful improvements in FACIT-Fatigue scores were observed with danicopan treatment and were largely maintained through week 72 of this trial. Overall, mean FACIT-Fatigue scores observed with danicopan treatment in the ALPHA trial were comparable with those reported in the general population.24 These results suggest that long-term danicopan treatment can result in clinically meaningful improvements in fatigue.

A potential limitation of this trial was that there was no predefined end point of BTH; investigators reported BTH as a safety event based on their own clinical judgment. Additionally, the trial included a small number of participants and excluded pediatric patients. However, PNH is a rare disorder in which even fewer individuals have cs-EVH on a C5 inhibitor therapy. Moreover, pediatric onset of PNH is also very rare. Further data are needed to determine whether danicopan is similarly effective in this patient population within a real-world setting. In the small subpopulation of patients with PNH with cs-EVH, treatment plans should consider efficacy and safety with the potential burden of combination therapy. Tools are in development to manage treatment regimens for PNH.

Notably, danicopan has been approved in the United States, European Union, and Japan as an add-on therapy to ravulizumab or eculizumab in adults with PNH.22,36,37 These long-term results confirm the efficacy and safety of danicopan as an add-on therapy to ravulizumab or eculizumab for PNH with cs-EVH through 72 weeks of treatment, supporting the findings from the primary ALPHA analysis.23 Danicopan demonstrated a favorable benefit-risk profile, and no new safety signals were identified. Dual inhibition of terminal complement and the AP addresses terminal complement activity, IVH, and cs-EVH in patients with PNH through sustained inhibition, with limited risk of severe or unpredictable BT-IVH.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients who participated in this trial, their families, and the trial investigator teams. The authors and sponsor acknowledge Cynthia Carrillo-Infante for contributions to the trial related to safety and pharmacovigilance. Medical writing support was provided by Nancy Nguyen and Jennifer Fetting from The Curry Rockefeller Group, LLC, a Citrus Health Group, Inc, company (Chicago, Illinois).

This study was funded by Alexion, AstraZeneca Rare Disease. Medical writing was funded by Alexion, AstraZeneca Rare Disease.

Authorship

Contribution: A.K. and M.G. contributed to the study conceptualization and refining of the research idea, data acquisition, data analysis and interpretation, and writing of the original draft, as well as reviewing and editing the manuscript; C. Piatek and J.S. contributed to data acquisition and writing of the original draft, as well as reviewing and editing the manuscript; J.-i.N., C. Patriquin, H.S., W.B., and J.P. contributed to the study conceptualization, data analysis and interpretation, writing of the original draft, as well as reviewing and editing the manuscript; A.G. contributed to the data acquisition and writing of the original draft, as well as reviewing and editing the manuscript; Y.P. contributed to the study conceptualization, refining of the research idea, selection of instruments, measures, and statistical tests/statistical analysis plan (SAP), data acquisition, data analysis and interpretation, and writing of the original draft, as well as reviewing and editing the manuscript; P.L. contributed to refining the research idea, selection of instruments, measures, and statistical tests/SAP, data analysis and interpretation, and writing of the original draft, as well as reviewing and editing the manuscript; G.F. contributed to study conceptualization, refining the research idea, data analysis and interpretation, visualization, and writing of the original draft, as well as reviewing and editing the manuscript; and F.S.d.F., A.R., and J.W.L. contributed to the study conceptualization and refining of the research idea, data acquisition, data analysis and interpretation, and writing of the original draft, as well as reviewing and editing the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: A.K. has received honoraria from Alexion, AstraZeneca Rare Disease, Amgen, Agios, Celgene/Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Samsung, and Sobi; is on the board of directors or is an advisory board member for Alexion, AstraZeneca Rare Disease, Amgen, BioCryst, Celgene/BMS, Novartis, Regeneron, and Roche; and has received consulting fees from Alexion, AstraZeneca Rare Disease, Celgene/BMS, Novo Nordisk, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, Roche, Samsung, Sobi, and Novartis. M.G. has received honoraria from Alexion, AstraZeneca Rare Disease, Sobi, and Pfizer; has served as an advisory board member for Alexion, AstraZeneca Rare Disease, Amgen, BioCryst, Novartis, Pfizer, and Sobi; has served as a consultant for BioCryst and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals; and has received educational grant support from Apellis. C. Piatek has served as a consultant to Alexion, AstraZeneca Rare Disease; has served on board or advisory committees for Annexon Biosciences, Apellis, Alexion, AstraZeneca Rare Disease, Rigel, Sanofi, and Sobi; has served on a speakers bureau for Sobi; and has received research funding from Argenx, Alexion, AstraZeneca Rare Disease, Celgene, Oscotec, Rigel, Sanofi, and Incyte. J.S. has received honoraria and consulting fees from Alexion, AstraZeneca Rare Disease, Apellis, BMS, CTI Bio, GlaxoSmithKline, Incyte, Novartis, and Sanofi. J.-i.N. has received grants from Alexion, AstraZeneca Rare Disease; is an advisory board member for Alexion, AstraZeneca Rare Disease, Chugai, and Roche; and has received honoraria from Alexion, AstraZeneca Rare Disease. C. Patriquin has received honoraria for participation in speaker bureaus and/or consulting from Alexion, AstraZeneca Rare Disease, Apellis, Amgen, BioCryst, Novartis, Roche, Sanofi, Sobi, and Takeda and has served as a clinical site investigator for Alexion, AstraZeneca Rare Disease and Apellis. H.S. has received travel support, honoraria, and research support (to institution) from Alexion, AstraZeneca Rare Disease, Novartis, and Sobi and honoraria (to University of Ulm) from Alexion, AstraZeneca Rare Disease, Apellis, Roche, Sanofi, and Sobi. W.B. has served as a consultant to Alexion, AstraZeneca Rare Disease, Novartis, Roche, Sanofi, and Sobi and received research funding from Alexion. J.P. has received honoraria from and is an advisory board member for Alexion, Amgen, Apellis, AstraZeneca, Blueprint Medicines, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Gilead, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi, and Sobi; has received travel support from Alexion, Blueprint Medicines, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, and Sobi; has served in a leadership or fiduciary role for the Lichterzellen Foundation; and has received other support from Apellis, Blueprint Medicines, Novartis, and Roche. A.G. has received honoraria from Alexion, AstraZeneca Rare Disease, Novartis, Roche, and Sobi and is an advisory board member for Alexion, AstraZeneca Rare Disease, Novartis, Roche, and Sobi. Y.P., P.L., and G.F. are employees of Alexion, AstraZeneca Rare Disease. F.S.d.F. has received honoraria and research support (to Saint-Louis Hospital, Paris, France) from Alexion, AstraZeneca Rare Disease, Novartis, Samsung, and Sobi. A.R. has received consultancy fees and honoraria from Alexion, AstraZeneca Rare Disease, Roche, and Novartis and research funding from Alexion, AstraZeneca Rare Disease and Roche. J.W.L. has received grants from Alexion, AstraZeneca Rare Disease and Achillion; is a member of an advisory board for and has received honoraria from Alexion, AstraZeneca Rare Disease; and is a consultant to Kyowa Kirin, Novartis, and Sanofi.

Correspondence: Jong Wook Lee, Division of Hematology-Oncology, Hanyang University Seoul Hospital, 222-1 Wangsimni-ro, Seongdong-gu, Seoul 04763, Republic of Korea; email: jwlee@hyumc.com.

References

Author notes

Alexion, AstraZeneca Rare Disease will consider requests for disclosure of clinical study participant-level data, provided that participant privacy is assured through methods such as data deidentification, pseudonymization, or anonymization (as required by applicable law), and if such disclosure was included in the relevant study informed consent form or similar documentation. Qualified academic investigators may request participant-level clinical data and supporting documents (statistical analysis plan and protocol) pertaining to Alexion-sponsored studies.

Further details regarding data availability and instructions for requesting information are available in the Alexion Clinical Trials Disclosure and Transparency Policy at https://www.alexionclinicaltrialtransparency.com/data-requests/.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal