Abstract

Congenital factor XIII (FXIII) deficiency is potentially a severe bleeding disorder, but in some cases, the symptoms may be fairly mild. In this study, we have characterized the molecular mechanism of a mild phenotype of FXIII A-subunit deficiency in a Finnish family with two affected sisters, one of whom has even had two successful pregnancies without regular substitution therapy. In the screening tests for FXIII deficiency, no A-subunit could be detected, but by using more sensitive assays, a minute amount of functional A-subunit was seen. 3H-putrescine incorporation assay showed distinct FXIII activity at the level of 0.35% of controls, and also the fibrin cross-linking pattern in the patients clotted plasma showed partial γ-γ dimerization. In Western blot analysis, a faint band of full-length FXIII A-subunit was detected in the patients' platelets. The patients have previously been identified as heterozygotes for the Arg661 → Stop mutation. Here we report a T → C transition at position +6 of intron C in their other allele. The transition affected splicing of FXIII mRNA resulting in low steady state levels of several variant mRNA transcripts. One transcript contained sequences of intron C, whereas two transcripts resulted from skipping of one or two exons. Additionally, correctly spliced mRNA lacking the Arg661 → Stop mutation of the maternal allele could be detected. These results demonstrate that a mutation in splice donor site of intron C can result in several variant mRNA transcripts and even permit partial correct splicing of FXIII mRNA. Further, even the minute amount of correctly processed mRNA is sufficient for producing protein capable of γ-γ dimerization of fibrin. This is a rare example of an inherited functional human disorder in which a mutation affecting splicing still permits some correct splicing to occur and this has a beneficial effect to the phenotype of the patients.

CONGENITAL FACTOR XIII (FXIII) deficiency is a rare autosomal recessive bleeding disorder that is characterized by defective cross-linking of fibrin and poor resistance to fibrinolysis. The severity of the bleeding tendency varies from benign symptoms like excessive bruising to life threatening bleeding emergencies such as intracranial hemorrhages. Symptoms that are almost pathognomonic for FXIII A-subunit deficiency are umbilical bleeding in the neonatal period and repeated fetal wastage in pregnant females.1-3 Generally, most of the patients require lifelong substitution therapy to prevent serious bleeding complications.

About 200 cases of FXIII deficiency have been reported,3 and the general frequency of FXIII deficiency has been estimated at 1 patient in 2 million.4 The genetic defect is usually in the catalytic A-subunit of FXIII, which circulates in plasma as a heterotetramer with two protective B-subunits. FXIII A-subunit is mainly expressed in megacaryocytes/platelets and monocytes/macrophages.5-7 A small amount is also expressed in the liver.8 Intracellularly, FXIII exists as a dimer consisting exclusively of A-subunits. In some tissues, like placenta, cellular FXIII located in tissue macrophages is present in high concentrations. FXIII A-subunit belongs to the family of transglutaminases. They are calcium-dependent thiol enzymes making γ-glutamyl–ε-lysyl–cross-links between two polypeptide chains, thus enhancing the stability of protein structures.9

To date, approximately 20 mutations have been reported in the gene for FXIII A-subunit.3,10-18 Half of the mutations consist of nonsense mutations, such as stop codons, splicing errors, and frameshift mutations, and the other half consist of missense mutations that lead to the substitutions of single amino acids. Although the crystallization and determination of the 3-dimensional structure of FXIII A-subunit19 has provided new insights in understanding the structural consequences of the different mutations,17 there is little information about the correlation between different genotypes and phenotypes in FXIII deficiency. Here we describe detailed molecular, genetic, and biochemical studies of two patients who demonstrate an untypically mild phenotype of FXIII A-subunit deficiency, one of them having two successful pregnancies without being on regular FXIII substitution therapy. Our aim was to analyze whether the mild phenotype is the result of a mutation that permits the production of some active enzyme, eg, a mild amino acid change, a promotor mutation, or an incomplete splicing defect, or the effect of other genetic or environmental factors. Our results indicate that the molecular mechanism of a mild phenotype here is an incomplete splicing defect in which a minute amount of correctly spliced A-subunit mRNA facilitates production of a small quantity of active enzyme, sufficient for relieving the clinical outcome of the bleeding disorder.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

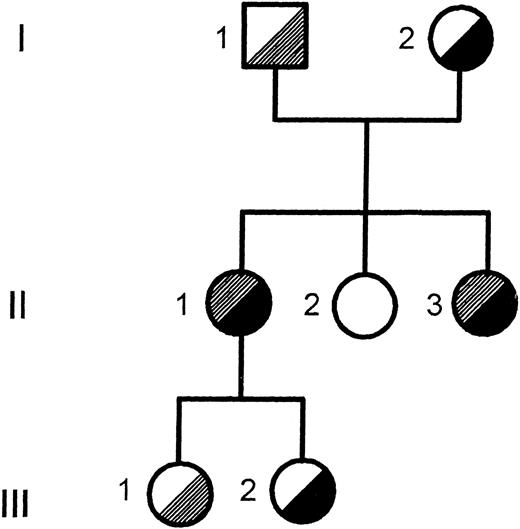

Patients.Two affected patients in a Finnish family were studied. Patient II-1 (Fig 1) was born in 1959. There is no evidence of umbilical bleeding in the neonatal period. She has shown bruising tendency from childhood but usually no severe bleeding symptoms. She was diagnosed with FXIII deficiency by a clot solubility test in 5 mol/L urea, after her sisters' bleeding symptoms led them to search for medical attention in 1978. In Laurell's rocket electrophoresis, no A-subunit antigen was detectable. She had two pregnancies in 1979 and 1985, during which she was not receiving any blood products. The first pregnancy proceeded without complications until the 31st week when ablation of the placenta and massive bleeding occurred. She received one transfusion of fresh frozen plasma to protect the ceasarean section of a healthy baby girl. The other pregnancy proceeded until the 37th week when ablation of placenta occurred necessitating a transfusion of fresh frozen plasma and ceasarean section of a healthy baby girl. There is no evidence of spontaneous abortions. In addition to the two treatments for the obstetric emergencies, she has needed substitution therapy only once for a traumatic intramuscular hemorrhage, and she has not received any blood products in recent years.

Pedigree of the Finnish family. The segregation of the T → C transition in intron C and the Arg661 → Stop mutation in exon XIV is shown. , T → C intron C; , Arg 661 → stop.

Pedigree of the Finnish family. The segregation of the T → C transition in intron C and the Arg661 → Stop mutation in exon XIV is shown. , T → C intron C; , Arg 661 → stop.

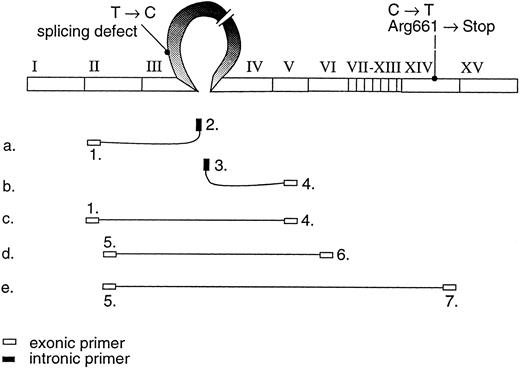

The position of the primers used to study the variant mRNA transcripts shown on the cDNA profile.

The position of the primers used to study the variant mRNA transcripts shown on the cDNA profile.

Patient II-3 was born in 1962. Her bleeding tendency was noticed by medical personnel in 1970 when her pharyngeal tonsils were operated on, resulting in an unusually long bleeding episode. In 1978, she was investigated because of hematuria, continuously bleeding wound in the forehead, and intramuscular hematoma. FXIII deficiency was diagnosed by a clot solubility test, and the intramuscular hematoma was treated by fresh frozen plasma. Thereafter, she has needed substitution treatment irregularly, not more than 3 times a year, mostly because of traumas from sporting activities. In the past years, she has had less bleeding symptoms and no further need for substitution therapy or other blood products. She has not had any pregnancies or spontaneous miscarriages.

Analysis of the FXIII A-subunit gene.The genetic analysis in the patients was performed mainly as described earlier.13 The coding regions and the intron exon boundaries of the A-subunit gene20 were screened for nucleotide sequence changes by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification and single-strand conformation polymorphism (SSCP).21 The PCR fragments demonstrating abnormal mobility in SSCP were sequenced after solid phase purification22 by the Sanger dideoxy-chain termination method. The primers used in the study were mainly the same as described earlier13; thus only the primers used to study the mutation described in this report are shown in Fig 2 and Table 1.

Primer Sequences

| PCR primers |

| 1. GACCTTGTAAAGTCAAAAATGTC |

| 2. bio CTCTCTACAATGCAACCCATG |

| 3. bio CTTGTGAAATCAACCTAACAGAG |

| 4. CTGACCATAGCTCCAGCTTC |

| 5. GAAGATGACCTGCCCACAGTG |

| 6. bio CTCTGCAAAAACAAAAGGTGC |

| 7. bio ACCATCCAGGTGTACCCAGAC |

| Cloning primers |

| 5restr. TTCAAGCTTGAAGATGACCTGCCCACAGTG Hind III |

| 7restr. ATATCTAGAACCATCCAGGTGTACCCAGAC Xba I |

| Minisequencing primers |

| T → C intron C TGGAATACGTCATTGGTGAG |

| Arg661 → Stop (C → T) ATCCTTTAAAAGAAACCCTG |

| PCR primers |

| 1. GACCTTGTAAAGTCAAAAATGTC |

| 2. bio CTCTCTACAATGCAACCCATG |

| 3. bio CTTGTGAAATCAACCTAACAGAG |

| 4. CTGACCATAGCTCCAGCTTC |

| 5. GAAGATGACCTGCCCACAGTG |

| 6. bio CTCTGCAAAAACAAAAGGTGC |

| 7. bio ACCATCCAGGTGTACCCAGAC |

| Cloning primers |

| 5restr. TTCAAGCTTGAAGATGACCTGCCCACAGTG Hind III |

| 7restr. ATATCTAGAACCATCCAGGTGTACCCAGAC Xba I |

| Minisequencing primers |

| T → C intron C TGGAATACGTCATTGGTGAG |

| Arg661 → Stop (C → T) ATCCTTTAAAAGAAACCCTG |

Abbreviation: bio, biotinylated primer; restr, primer with restriction enzyme site.

The segregation of the mutation in the family was verified by solid-phase minisequencing as described earlier.13 23 Two hundred controls in the Finnish population were analyzed for the mutation by solid-phase minisequencing using 20 DNA pools of 10 individuals each.

Analysis of FXIII A-subunit mRNA.RNA was extracted from the buffy-coat fraction of peripheral blood by RNAzol kit (Tel-test, Friendswood, TX). The reverse transciptase (RT) reaction was performed as described earlier12 by using specific primers for FXIII A-subunit cDNA. Primers used to study the different mRNA species are shown in Fig 2 and Table 1. RT-PCR products of the variant mRNA transcripts were purified from 1% low-melting gel (SeaPlaque GTG; FMC-Bio-Products, Rockland, ME) and sequenced directly. A 2-kb fragment containing most of the coding region was amplified by primers containing HindIII and Xba I restriction sites (Table 1) and cloned into SVPoly vector. The clones were analyzed by PCR and minisequencing of the Arg661 → Stop mutation to distinguish between the different allelic transcripts.

Analysis of FXIII activity by 3H-putrescine incorporation.The transglutaminase activity in plasma and platelets was studied by the filter paper assay of Lorand et al24 using 3H-putrescine as a radiolabeled amine substrate. Washed platelets were homogenized in 50 mmol/L HEPES, 100 mmol/L NaCl buffer that contained 1% Triton X-100 and protease inhibitors (5 mmol/L EDTA, 10 μg/mL benzamidine, and 100 U/mL aprotinin). To discriminate between FXIII activity and other transglutaminase or specific activity, control reactions were performed by blocking with FXIII A-subunit specific antibody (Clotimmun, Behringwerke AG, Marburg).

Analysis of cross-linking of fibrin in clotted plasma.FXIII activity was further characterized by analyzing the cross-linking of fibrin in clotted plasma. A total of 100 μL of plasma samples were clotted by the addition of 50 μL CaCl2 (40 mmol/L) and 50 μL thrombin (20 U/mL). In control and patient samples, FXIII activity was parallerly inhibited by the addition of 2 mmol/L iodoacetamide. The fibrin clot formed was collected on a fine nylon filter, associated plasma proteins were washed away, the clot was dissolved in sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) sample buffer and analyzed in 7.5% SDS polyacrylamide gel.

Analysis of FXIII A-subunit antigen by Western blot.FXIII A-subunit antigen in platelets was studied by Western blot analysis essentially as described earlier.25 Washed platelets were homogenized in SDS-PAGE sample buffer. The protein concentration of the samples was determined. The samples were electrophoresed in 7.5% SDS-PAGE and electroblotted to Immobilon P membrane. The membrane was blocked with 5% milk proteins and incubated with polyclonal rabbit anti-FXIII antiserum (Clotimmun) or with nonimmune rabbit serum. The reaction was developed by Vectastain ABC kit (Vectastain ABC; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). The experiment was repeated with alternative blocking procedure by 3% gelatin.

RESULTS

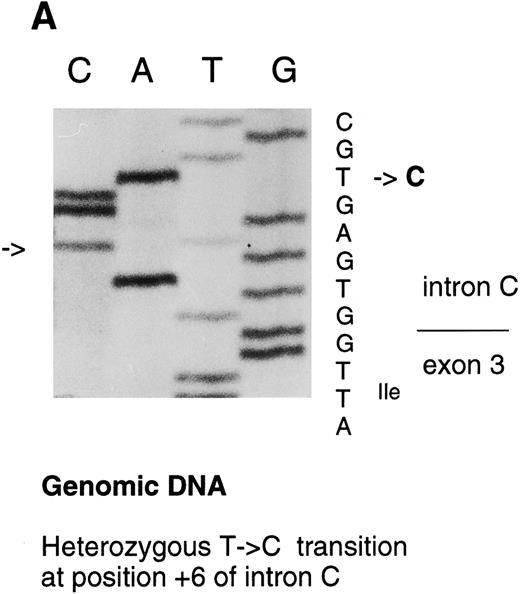

Analysis of the FXIII A-subunit gene.The molecular analysis of two patients with a mild FXIII A-subunit deficiency was performed by complete screening of the coding regions and intron exon boundaries of FXIII A-subunit gene. The C → T transition in exon XIV resulting in Arg661 → Stop mutation in the patients' maternal allele has been reported previously by us.13 In this study, a heterozygous T → C transition was detected at position +6 in intron C by SSCP and consequent direct sequencing (Fig 3A).

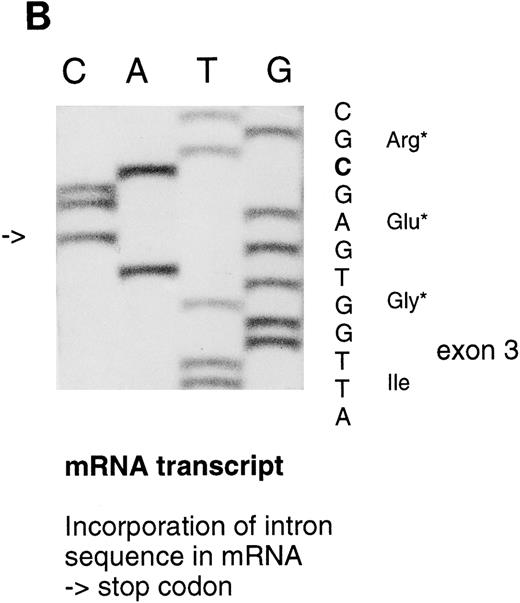

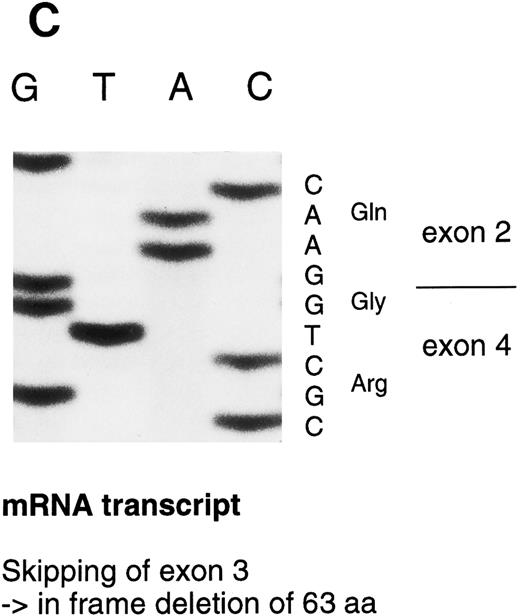

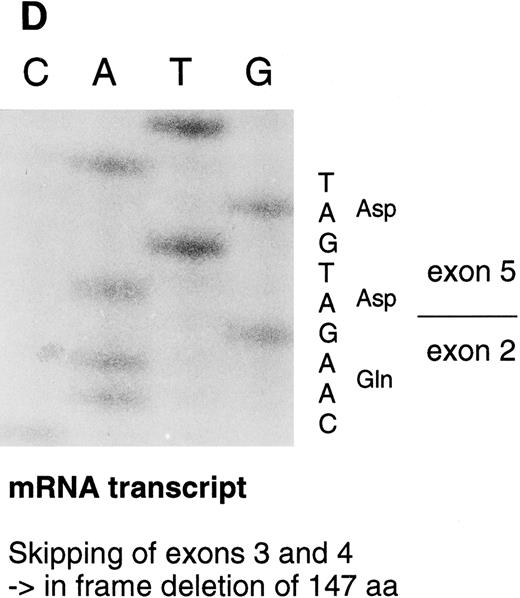

Sequencing gels demonstrating the patients' DNA-mutation and the variant mRNA transcripts. (A) Sequencing of the patients' DNA shows a novel mutation, a heterozygous T → C transition at position +6 of intron C. (B) Sequencing of the RT-PCR product through exon 3/intron C boundary shows the incorporation of intronic sequence into the patients' mRNA and the T → C transition at position +6. * indicates altered amino acid sequence. (C) Sequencing of a truncated RT-PCR product in the antisense direction shows skipping of exon 3 (correct sequence in the boundary exons 2 and 3 is CAAG/AGTTT and exons 3 and 4 is ATTG/GTCGT.20 (D) Sequencing of a truncated RT-PCR-product shows skipping of exons 3 and 4 (correct sequence in the boundary of exons 4 and 5 is GAAG/ATGAG.20

Sequencing gels demonstrating the patients' DNA-mutation and the variant mRNA transcripts. (A) Sequencing of the patients' DNA shows a novel mutation, a heterozygous T → C transition at position +6 of intron C. (B) Sequencing of the RT-PCR product through exon 3/intron C boundary shows the incorporation of intronic sequence into the patients' mRNA and the T → C transition at position +6. * indicates altered amino acid sequence. (C) Sequencing of a truncated RT-PCR product in the antisense direction shows skipping of exon 3 (correct sequence in the boundary exons 2 and 3 is CAAG/AGTTT and exons 3 and 4 is ATTG/GTCGT.20 (D) Sequencing of a truncated RT-PCR-product shows skipping of exons 3 and 4 (correct sequence in the boundary of exons 4 and 5 is GAAG/ATGAG.20

The segregation of the T → C transition in intron C within the family was verified by solid-phase minisequencing. The two patients (II-1 and II-3) and the older daughter (III-1) of patient II-1 inherited the mutation from the father (I-1; Fig 1).

To discriminate between a potential disease mutation and a common polymorphism in the Finnish population, 200 control individuals were screened by solid-phase minisequencing. None of these individuals carried the T → C transition at position +6 in intron C.

Analysis of FXIII A-subunit mRNA.FXIII A-subunit mRNA was studied to elucidate the possible consequences of this intronic mutation. As FXIII A-subunit is expressed in peripheral blood monocytes, and platelets, mutant FXIII mRNA could be analyzed in vivo. At an earlier time, the patients' FXIII mRNA had been quantitated allele-specifically; the steady-state mRNA levels of the transcripts from both the maternal allele with the Arg661 → Stop mutation and the paternal allele with the as yet unidentified mutation were drastically reduced to less than 5% of normal values.13

The RT-PCR primers used to study the different mRNA transcripts are shown in Fig 2 and Table 1. By using 5′ primer from exon 2 and 3′ primer from intron C (primers 1 and 2), an abnormal PCR product was identified from the two patients, whereas, in control individuals, no PCR product could be detected. The sequence analysis of the abnormal PCR product showed the nucleotides through the splice donor site at exon 3/intron C boundary and the T → C transversion at position +6 of intron C (Fig 3B), indicating the incorporation of the intronic sequence into the transcript. Consequently, a stop codon would be created at nucleotide position +48-50 of intron C. The RT-PCR amplification of intron C/exon 4 splice acceptor site (primers 3 and 4) also resulted in PCR product in the patients, which indicates that the 3′ end of the intron C was also integrated into one of the mRNA transcript species. Because of the excessive length of intron C, it was not possible to amplify the complete intron sequence, either from genomic DNA or cDNA template; therefore, it could not be defined whether the intron C was completely integrated in the mRNA.

The RT-PCR amplification of the coding region (primers 1-4, 5-6, and 5-7) resulted in several amplification products that were sequenced. In one PCR product, 189 nucleotides from the mRNA were deleted by skipping of exon 3. This would result in an in frame deletion of 63 amino acids. In a more rare transcript species, 441 nucleotides including both exons 3 and 4, were skipped resulting in an in frame deletion of 147 amino acids (Fig 3D). A precise quantitation of the aberrant transcripts was not possible because of variable amplification efficiency of the different primer pairs.

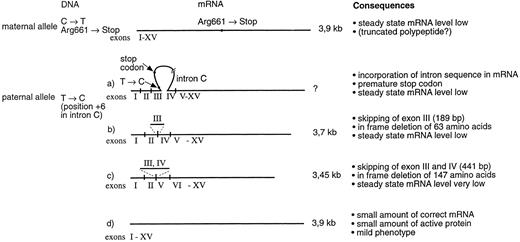

The 2-kb fragment containing most of the coding region was cloned and the clones of the normal size were further analyzed by solid-phase minisequencing to monitor the presence or absence of the Arg661 → Stop mutation, which separates the maternal and paternal alleles. About half of the clones with correctly spliced mRNA result from the maternal allele with the Arg661 → Stop mutation, whereas the other half correspond to correctly spliced mRNA from the paternal allele lacking the Stop codon at Arg661 (Fig 4).

Schematic presentation of the different mRNA transcript species in patients II-1 and II-3. Maternal allele produces reduced amount of a 3.9-kb mRNA that contains the Arg661 → Stop mutation in exon XIV. The paternal allele produces several mRNA variants. One of the transcripts contains sequence from intron C, which creates a premature stop codon in the mRNA. Two of the transcripts show exon skipping. In a more abundant transcript, exon 3 has been skipped and in a more rare transcript, both exons 3 and 4 have been skipped. Most importantly, the paternal allele also produces a minute amount of correctly spliced mRNA, thus facilitating the production of some active enzyme and resulting in a mild disease phenotype.

Schematic presentation of the different mRNA transcript species in patients II-1 and II-3. Maternal allele produces reduced amount of a 3.9-kb mRNA that contains the Arg661 → Stop mutation in exon XIV. The paternal allele produces several mRNA variants. One of the transcripts contains sequence from intron C, which creates a premature stop codon in the mRNA. Two of the transcripts show exon skipping. In a more abundant transcript, exon 3 has been skipped and in a more rare transcript, both exons 3 and 4 have been skipped. Most importantly, the paternal allele also produces a minute amount of correctly spliced mRNA, thus facilitating the production of some active enzyme and resulting in a mild disease phenotype.

Analysis of FXIII activity by 3H-putrescine incorporation.FXIII activity was analyzed from the patients' plasma and platelets by the incorporation of 3H-putrescine into casein. Very low, but distinct, FXIII activity in the patients' plasma and platelets was detected (Tables 2 and 3). The activity was at the level 0.1% to 0.35% of controls in both of the patients. However, the transglutaminase activity was shown to be specific for FXIII, as a clear decrease in the activity could be shown by adding an inhibitory FXIII A-subunit antibody to the reaction mixture (Table 4). The two heterozygotes analyzed (the daughters of patient I-1) had FXIII activity levels between 30% to 69% of control values.

FXIII Activity in Plasma

| . | dpm/μL plasma/min . | % of Control . |

|---|---|---|

| Control | 187.7 | 100 |

| Patient II-1 | 0.6 | 0.3 |

| Patient II-3 | 0.2 | 0.1 |

| Carrier III-1 | 130 | 69 |

| Carrier III-2 | 118 | 63 |

| . | dpm/μL plasma/min . | % of Control . |

|---|---|---|

| Control | 187.7 | 100 |

| Patient II-1 | 0.6 | 0.3 |

| Patient II-3 | 0.2 | 0.1 |

| Carrier III-1 | 130 | 69 |

| Carrier III-2 | 118 | 63 |

FXIII Activity in Platelet Homogenates

| . | dpm/μg/min . | % of Control . |

|---|---|---|

| Control | 263 | 100 |

| Patient II-1 | 0.93 | 0.35 |

| Patient II-3 | 0.92 | 0.35 |

| Carrier III-1 | 78 | 30 |

| Carrier III-2 | 119 | 45 |

| . | dpm/μg/min . | % of Control . |

|---|---|---|

| Control | 263 | 100 |

| Patient II-1 | 0.93 | 0.35 |

| Patient II-3 | 0.92 | 0.35 |

| Carrier III-1 | 78 | 30 |

| Carrier III-2 | 119 | 45 |

Inhibition of FXIIIa Activity in Platelet Homogenates by Anti-FXIIIA Antiserum

| . | dpm/μg/min . | % Inhibition . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| . | Without Anti-FXIIIA . | With Anti-FXIIIA . | . |

| Control | 263 | 25 | 90 |

| Patient II-1 | 0.93 | 0.3 | 68 |

| Patient II-3 | 0.92 | 0.1 | 89 |

| Carrier III-1 | 78 | 10 | 87 |

| Carrier III-2 | 119 | 10 | 91 |

| . | dpm/μg/min . | % Inhibition . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| . | Without Anti-FXIIIA . | With Anti-FXIIIA . | . |

| Control | 263 | 25 | 90 |

| Patient II-1 | 0.93 | 0.3 | 68 |

| Patient II-3 | 0.92 | 0.1 | 89 |

| Carrier III-1 | 78 | 10 | 87 |

| Carrier III-2 | 119 | 10 | 91 |

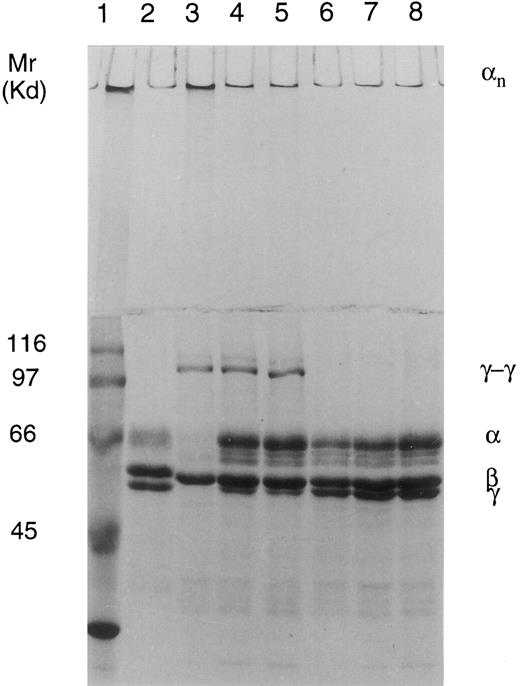

Analysis of cross-linking of fibrin in clotted plasma.In normal plasma, there was a full cross-linking of α- and γ-chains, which was shown by the complete disappearance of both chains and the appearance of γ-γ dimers and high Mr α polymers in SDS-PAGE. In the two FXIII-deficient patients, there is a clear diminution of γ-chains and appearance of γ-γ dimers and probably even some α polymers, which indicates that the patients have some FXIII activity in plasma. The process could be blocked by the addition of transglutaminase inhibitor iodoacetamide, and also the pattern of cross-linking, which consists predominantly of γ-γ dimers, clearly suggests that the cross-linking is caused by activated FXIII (Fig 5).

Cross-linking of fibrin in normal and FXIII-deficient plasma clotted by thrombin and CaCl2 shown on 7.5% SDS-PAGE. Lane 1, Mr marker proteins; lane 2, fibrinogen standard; lane 3, control plasma; lane 4, patient II-3; lane 5, patient II-1; lane 6, control plasma + iodoacetamide acid (IAA); lane 7, patient II-3 + IAA; and lane 8, patient II-1 + IAA. Cross-linking pattern in the control plasma shows disappearance of γ- and α-chains and formation of γ-γ dimers and α polymers. Cross-linking pattern in the patients; plasma shows diminution of the γ-chains and formation of γ-γ dimers and possibly even some α polymers at the top of the stacking gel, indicating the presence of true FXIII activity. The process is inhibited by treatment with transglutaminase inhibitor iodoacetamide acid.

Cross-linking of fibrin in normal and FXIII-deficient plasma clotted by thrombin and CaCl2 shown on 7.5% SDS-PAGE. Lane 1, Mr marker proteins; lane 2, fibrinogen standard; lane 3, control plasma; lane 4, patient II-3; lane 5, patient II-1; lane 6, control plasma + iodoacetamide acid (IAA); lane 7, patient II-3 + IAA; and lane 8, patient II-1 + IAA. Cross-linking pattern in the control plasma shows disappearance of γ- and α-chains and formation of γ-γ dimers and α polymers. Cross-linking pattern in the patients; plasma shows diminution of the γ-chains and formation of γ-γ dimers and possibly even some α polymers at the top of the stacking gel, indicating the presence of true FXIII activity. The process is inhibited by treatment with transglutaminase inhibitor iodoacetamide acid.

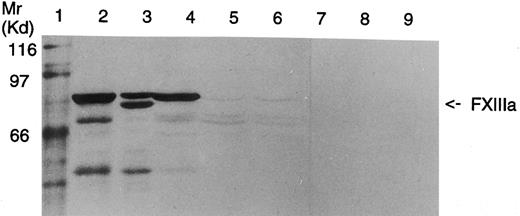

Analysis of FXIII A-subunit antigen in platelets by Western blot.In Western blot analysis, a faint band corresponding to the length of the wild-type FXIII A-subunit was observed in the patients' platelets (Fig 6). This suggests that both patients have a minute amount of full-length FXIII A-subunit in their platelets. Because of the small quantity of the polypeptide chains, it could not be defined whether the slightly shorter fragments observed in the patients' platelets would represent protein breakdown products or translated polypeptides corresponding to FXIII polypeptides truncated either by 63 amino acids from the transcript lacking exon 3 or by 70 amino acids from the transcript with the Arg661 → Stop mutation.

Western blot analysis of platelet homogenates from a healthy donor and FXIII-deficient patients. Lane 1, Mr marker proteins; lane 2, FXIIIA 2.5 μg; lane 3, partially acivated FXIIIA 2.5 μg; lane 4, homogenate of control platelets, 50 μg protein, lanes 5 and 6, homogenates of FXIII-deficient platelets (patients II-1 and II-3, respectively), 125 μg protein; lanes 7 to 9, same as lanes 4 to 6, but incubated with nonimmune rabbit serum. In both the patients a minute amount of full-length FXIII A-subunit can be detected.

Western blot analysis of platelet homogenates from a healthy donor and FXIII-deficient patients. Lane 1, Mr marker proteins; lane 2, FXIIIA 2.5 μg; lane 3, partially acivated FXIIIA 2.5 μg; lane 4, homogenate of control platelets, 50 μg protein, lanes 5 and 6, homogenates of FXIII-deficient platelets (patients II-1 and II-3, respectively), 125 μg protein; lanes 7 to 9, same as lanes 4 to 6, but incubated with nonimmune rabbit serum. In both the patients a minute amount of full-length FXIII A-subunit can be detected.

DISCUSSION

FXIII deficiency is considered a severe bleeding disorder because there is a substantial risk for life threatening bleeding emergencies like intracranial hemorrhages. Still, the severity of the bleeding tendency is not always equal, as there are patients who experience mostly pronounced bruising tendency and manage well without substitution therapy. There is relatively little information about the genotype-phenotype correlation in FXIII deficiency, and because of the small number of patients, this question cannot be evaluated statistically. It is possible that different mutations affect the resulting phenotype, especially because only a minute amount of functional FXIII is sufficient for allowing partial fibrin cross-linking to occur, which aids in maintaining proper hemostasis in the patient. FXIII levels as low as 1% to 2% are considered to be sufficient for rendering the clot chemically insoluble in vitro. No clear-cut relationship between activity levels and the severity of the bleeding tendency has been shown in FXIII deficiency, which may be partly caused by the insensitive methodology used for the determination of FXIII activity in the range below 5% of normal values. Generally, investigators have not detected clear FXIII activity or A-subunit antigen in patients. In contrast, in other inherited bleeding disorders such as hemophilias A and B, the relative level of functional FVIII or FIX activity observed in milder phenotypes is usually significantly higher, at the level of 5% to 30% of normal values.

Some variation in the expression of the bleeding symptoms is very likely to be caused by professions, hobbies, and personal habits, which predispose to physical trauma. Furthermore, certain pathological conditions with wound(s) of relatively large area such as ablatio placenta or inflammatory bowel disease, significantly increase the demand for functionally active FXIII, and in these cases, bleeding symptoms may appear even at a somewhat higher FXIII level. Additionally, other genetic factors, eg, in the hemostatic system, might provoke the bleeding symptoms or protect from them.

There are features that are thought to be universal in FXIII deficiency; eg, women experience habitual fetal wastage in the early stages of pregnancy unless prophylactic therapy is administered. The patient II-1 in this study represents an unusual exception to the rule. She has had two pregnancies without any substitution therapy before the 31st and 37th weeks when ablation of placenta and first bleeding complications occured necessitating transfusions of fresh-frozen plasma and ceasarean sections. Her bleeding symptoms have been mild throughout her life, and she does not need prophylactic substitution therapy. Her sister, patient II-3 in this study, has had slightly more symptomatic disease. She has needed some transfusions of fresh-frozen plasma for intramuscular hematomas caused by traumas sustained in sporting activities, which most likely have affected the occurence of bleeding symptoms at that time. Her bleeding symptoms have decreased in the past years, and there has been no further need for substitution therapy.

There are two reports in the literature of women with FXIII deficiency who have had successful pregnancies without substitution therapy.26,27 However, both of them were classified as type-I deficiencies, in which the genetic defect in the B-subunit results in poor stability of the A-subunit in plasma.28,29 Although there is a secondary A-subunit deficiency in plasma, the level of FXIII A-subunit in these patients is significantly higher than that in the patients with severe primary FXIII A-subunit deficiency; the intracellular FXIII A-subunit is present in a normal amount, and the bleeding diathesis is usually milder. To our knowledge, this is the first report of successful pregnancies in congenital FXIII A-subunit deficiency without regular substitution therapy.

In the two patients described here, the clot solubility test was positive and no A-subunit antigen could be detected by Laurell's rocket electrophoresis. However, we were able to detect distinct FXIII activity at the level of 0.35% of controls by a highly sensitive 3H-putrescine incorporation assay. The transglutaminase activity was proven to be FXIII-specific because the activity was inhibited by using an antibody against FXIII A-subunit that does not block other transglutaminases such as tissue transglutaminase from red blood cells, which might confuse the results (Muszbek et al, unpublished data, March 1994). The fibrin γ-chain dimerization pattern in plasma also proves that both the affected patients have true FXIII activity in circulation. If the fibrin was clotted, eg, by tissue transglutaminase from the red blood cells, the pattern of cross-linking would be different lacking γ-γ dimers.30,31 Other FXIII-deficient patients could not be used in this experiment, because most of them receive regular substitution therapy and, thus, show cross-linking of plasma fibrin because of exogenous FXIII. However, in the literature, the fibrin cross-linking pattern in FXIII deficiency has been characterized with the absence of γ-γ dimerization and α polymerization of fibrin.32 Also in Western blot analysis, a faint polypeptide band of 80 kD corresponding to the correct size of wild-type FXIII monomer was detected in both of the patients' platelets. Because the patients have not received blood products in recent years, the A-subunit antigen and the corresponding activity have to be of endogenous origin. Thus, on the basis of the protein data, our hypothesis was that the patients would carry a mutation that permits the production of some active enzyme.

In hemophilias and in many recessively inherited diseases, mild phenotypes are often associated with missense mutations resulting in mutated proteins that retain some structural stability and functional activity.33 In the case of FXIII in which the relative level of active enzyme required for proper hemostasis is very low, other possible mutations causing milder phenotypes would be, for example, promoter or other regulative element mutations that might reduce the efficiency of transcription or incomplete splicing defects that would permit some correct splicing to occur. The molecular analysis of the patients' DNA showed a compound heterozygosity for two mutations, a premature stop codon in the maternal allele and a splicing defect in the paternal allele. The maternal Arg661 → Stop mutation has been identified in the homozygous form in six Finnish patients, most of whom show a severe phenotype of the disease. It results in the truncation of the polypeptide by 70 amino acids, after which the second β barrel is not able to fold to its natural structure. Additionally, the stop mutation results in a drastic reduction of the steady-state allelic transcript levels.13

The T → C transition at position +6 of intron C results in splicing defect with multiple transcript species (Fig 4). Two transcripts are the result of exon skipping. In the most abundant transcript, the preceding exon 3 is skipped, which results in an in-frame deletion of 63 amino acids. In a more rare transcript, both exons 3 and 4 are missing, resulting in an in-frame deletion of 147 amino acids, which encode most of the β-sandwich domain of FXIII A-subunit. In one of the transcripts, intron sequence becomes incorporated into the mRNA, which would result in a premature stop codon.

In addition to the aberrant transcripts, a small amount of correctly spliced mRNA that lacks the Arg661 → Stop mutation of the maternal allele was detected by RT-PCR and solid-phase minisequencing. Thus, the protein data and the presence of wild-type FXIII mRNA suggests that, despite the mutation at the +6 position in intron C, U1 Sn RNP can occasionally recognize the consensus sequence of the splice donor site. Consequently, minute amounts of active FXIII A-subunit get synthesized that, by inducing partial cross-linking of fibrin, aid in maintaining the hemostasis in these patients (Fig 4).

Splice site mutations, which reduce but do not completely abolish normal processing of pre-mRNA, have been reported in other genes (for review of splicing mutations, see Krawczak et al34 ). In β-thalassemia, Menkes's disease, adenosine deaminase (ADA)-deficiency, and lipoid congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH), these kinds of mutations have been associated with milder phenotypic forms of the disease.35-38 In β-thalassemia, there was a distinct difference in the phenotypes of the patients who had the splicing mutation and positions +1, +5, and +6 of intervening sequence 1. The mutation at position 1 resulted only in aberrant mRNA, whereas the mutation at position +6 facilitated most of the splicing to occur correctly.

The 5′ splice donor site is typically determined by a consensus sequence CAG/GTAAGT. Some variations occur, but usually the nucleotides G and T at positions +1 and +2 are invariable. T was present at 63% frequency in position +6 of the splice donor sites of 13 genes.39 It could be possible that the position of the T → C transition in a not completely invariant nucleotide at the consensus sequence increases the probability for some correct splicing to occur.

In FXIII deficiency, five other mutations have so far been reported to affect correct pre-mRNA splicing. Two mutations have been described at the donor splice site of exon 3, in the immediate vicinity to the mutation site characterized here. A G → T transversion has been detected at the last position of exon 3, and G → A transition at position +5 of intron C. Both of these mutations result in skipping of exon 3.16 The third mutation involving exon skipping was a G → A transversion affecting the last position of exon 14 and resulting in skipping of exon 14.11,16 In two cases, cryptic splice sites were used. An AG deletion at AG/AG sequence at exon 2/intron B boundary destroyed the normal splice donor site, whereas the remaining AG was used as a novel splice site and major mRNA rearrangement in mRNA was avoided. The dinucleotide deletion caused a frameshift and an early stop codon.10 A G → A substitution at the last base of intron E mutated the invariant splice acceptor site, whereas a cryptic splice acceptor site 7 bases downstream was used.14 However, in none of the cases with the previously reported splicing mutations in FXIII deficiency has either detection of correctly spliced FXIII mRNA or relief in the disease phenotype been reported. Thus, the two patients described in this study represent a rare example of genotype-phenotype correlation in a partial splicing defect in an inherited, functional human disorder. Here, a mutation at position +6 at splice donor site permits a minute amount of correct splicing to occur, which could be shown on both the mRNA and protein level in vivo, and even the very low level of proper enzymatic activity was observed to have a beneficial effect on hemostasis in these patients.

Supported by the 350th Year Anniversary Foundation of the University of Helsinki; Finnish Cultural Foundation, Helsinki, Finland; and Hjelt Foundation Helsinki, Finland.

Address reprint requests to Aarno Palotie, MD, PhD, Department of Clinical Chemistry, University of Helsinki, Haartmaninkatu 4, 00290 Helsinki, Finland.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal