Abstract

Retention of lipoproteins within the vasculature is a central event in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. However, the signals that mediate this process are only partially understood. Prompted by putative links between inflammation and atherosclerosis, we previously reported that -defensins released by neutrophils are present in human atherosclerotic lesions and promote the binding of lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)] to vascular cells without a concomitant increase in degradation. We have now tested the hypothesis that this accumulation results from the propensity of defensin to form stable complexes with Lp(a) that divert the lipoprotein from its normal cellular degradative pathways to the extracellular matrix (ECM). In accord with this hypothesis, defensin stimulated the binding of Lp(a) to vascular matrices approximately 40-fold and binding of the reactants to the matrix was essentially irreversible. Defensin formed stable, multivalent complexes with Lp(a) and with its components, apoprotein (a) and low-density lipoprotein (LDL), as assessed by optical biosensor analysis, gel filtration, and immunoelectron microscopy. Binding of defensin/Lp(a) complexes to matrix was inhibited (>90%) by heparin and by antibodies to fibronectin (>70%), but not by antibodies to vitronectin or thrombospondin. Defensin increased the binding of Lp(a) (10 nmol/L) to purified fibronectin more than 30-fold. Whereas defensin and Lp(a) readily traversed the endothelial cell membranes individually, defensin/Lp(a) complexes lodged on the cell surface. These studies demonstrate that -defensins released from activated or senescent neutrophils stimulate the binding of an atherogenic lipoprotein to the ECM of endothelial cells, a process that may contribute to lipoprotein accumulation in atherosclerotic lesions.

THE DEVELOPMENT OF atherosclerosis results from an interplay among diverse factors, including endothelial cell denudation and activation, adherence and activation of platelets, hyperlipidemia, oxidation of lipoproteins, infiltration of the vessel wall by macrophages and their conversion to foam cells, and smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration, among others.1Although many prospective and cross-sectional studies demonstrate that elevated plasma levels of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and lipoprotein (a) [Lp(a)]1 are risk factors for atherosclerosis (eg, see Bostom et al2 and Assmann et al3), the overall complexity of the process may help to explain why no single factor correlates with disease incidence or severity in all individuals.4 Indeed, dyslipoproteinemia and other known risk factors have been estimated to account for only approximately half of the interindividual variability in the risk of developing atherosclerosis.5 6

Plasma levels of Lp(a) and other lipoproteins may not correlate with pathogenic events more closely, because additional factors regulate their interaction with the vasculature. The rate of lipoprotein transport into vessel walls exceeds the rate of egress or catabolism.7,8 This suggests that factors contributing to the retention of lipoproteins in vessel walls may contribute to atherogenesis.5,9,10 Vascular retention may be a prerequisite for subsequent injurious events such as monocyte migration,11 lipoprotein oxidation, uptake by scavenger receptors, generation of foam cells, and the induction of smooth muscle cell proliferation. In accord with this concept, reducing vascular retention time of lipoproteins may help to limit oxidant-induced vascular injury.12 Yet, considerable gaps remain in our understanding of how lipoproteins such as Lp(a) accumulate in atherosclerotic vessels13 .

Lp(a) closely resembles LDL in its content of cholesterol, phospholipid, and apolipoprotein B-100, but differs by the presence of an attached glycoprotein, known as apoprotein (a) [apo(a)], which invests the molecule with additional properties. Apo(a) is a modular protein composed of multiple tandem repeats of a sequence that closely resembles plasminogen kringle IV at its amino terminus followed by sequences that closely resemble kringle V and the protease domain of plasminogen.14 All apo(a) isoforms contain 10 distinct classes of kringle IV repeats. The variable number (<10 to >50 copies) of type IV-2 repeats is responsible for the size heterogeneity among Lp(a) isoforms.15 The sequence of kringle IV type 10 (alternately designated KIV-37) resembles that of plasminogen kringle IV most closely, especially with respect to the composition of its lysine-binding site (LBS; see below). Apo(a) binds to apoB initially through noncovalent associations involving kringle IV types 6-816 and subsequently by covalent binding through Cys4057 in kringle IV-9.17

Lp(a) binds to fibrin, fibronectin, proteoglycans, and cell surfaces18-21 through kringle (LBS)-dependent and, perhaps, kringle-independent processes.22 Residues in kringle IV-37 that contribute to binding have been identified through the study of primate homologues,23 recombinant kringles,24natural polymorphisms in the human protein,23,25 and, more recently, the study of transgenic mice expressing apo(a) variants.26,27 Apo(a) contains binding sites for fibrin that are masked in the Lp(a) particle but are exposed by proteolytic digestion.23 Lp(a) competes with plasminogen for binding to fibrin and to cells18,19,28 and inhibits plasmin-dependent fibrinolysis directly.29,30 Inhibition of plasmin formation may contribute to the terminal thrombotic complications associated with plaque rupture and impede the activation of latent transforming growth factor β (TGFβ), a potent inhibitor of smooth muscle cell (SMC) proliferation.31 32

Notwithstanding this knowledge, the mechanism by which the retention of Lp(a) in the vasculature is regulated is only partially understood. One insight in this process comes from the emerging appreciation of the relationship between inflammation and atherosclerosis (see Ridker33 and Tracy et al34 for review). For example, macrophages play a central role in the development of atherosclerosis.1,35 In addition, plasma concentrations of ferritin, interleukin-6, fibrinogen, and C-reactive protein have been identified as independent risk factors in the development of ischemic events and the probability of response to certain forms of therapy.36 A correlation between neutrophil numbers and atherosclerosis has also been observed in numerous studies (eg, Weijemberg et al37 and Zalokar et al38). Neutrophil activation leads to diverse biochemical changes, including the generation of hydrogen peroxide and oxygen radicals and the release of lysosomal enzymes that may alter vascular function.

Activated neutrophils also release α-defensins, a family of closely related peptides that comprise approximately 5% of their total protein content.39 Defensins are incorporated into the cell membranes of prokaryotic organisms within phagolysosomes, disrupting ion fluxes and eventuating in lysis of the organisms.40However, defensins are also released into the circulation during phagocytosis, a result of which plasma concentrations, which are normally less than 15 nmol/L, may approach 50 μmol/L during severe infection.41 42

α-Defensins are small (29 to 35 amino acid) peptides with structural features suggesting that they may regulate the binding of lipoproteins to the vasculature.43,44 One surface of the defensin molecule is hydrophobic, which enables these proteins to polymerize in lipid membranes and, conceivably, in lipoproteins. The other surface is hydrophilic and contains 3 free arginines that may enable defensin to bind to lipoprotein receptors as well as to proteoglycans, analogous to mechanism by which cationic residues contribute to the binding of apoB.45 46

We have previously reported that α-defensins are found in human atherosclerotic lesions.47,48 We also observed that α-defensins bind to cultured human endothelial cells and vascular smooth muscle cells, inhibit tissue type plasminogen activator-mediated fibrinolysis,48-50 and promote binding of Lp(a).48 It is of interest that the enhanced binding of Lp(a) was not accompanied by an increase in lipoprotein degradation. The purpose of this study was to consider 2 nonmutually exclusive hypotheses to explain how defensin promotes the accumulation of Lp(a) by vascular cells, ie, that defensin promotes the binding of Lp(a) to vascular matrices and/or that defensin inhibits the processes by which the lipoprotein is degraded.51 52

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Defensin.

Defensins (human neutrophil peptides 1 and 2) were prepared from human plasma and radiolabeled as described previously40,50; each protein migrated as a single band on sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Rabbit polyclonal and mouse monoclonal anti–HNP-1, which recognize HNP-2 and HNP-3, but not HNP-4 or HD-5, were prepared as described.53

Lipoproteins.

Lipoproteins were isolated from human plasma by ultracentrifugation at 1.21 g/mL. Lp(a) was isolated using lysine-sepharose chromatography. The fraction that binds to lysine-sepharose was brought to 7.5% CsCl (wt/wt) and centrifuged at 50,000 rpm for 27 hours to separate Lp(a) from triglyceride-rich material. LDL was purified from the fraction that did not bind to the lysine sepharose, as described.54All lipoprotein preparations were filtered under sterile conditions, aliquoted into plastic tubes, and stored under N2 at 4°C without exposure to light in 0.01% Na2EDTA, 0.1% NaN3, and 1 mmol/L benzamidine until use. The purity of Lp(a) and the apparent molecular weight (Mr) of the apo(a) was determined by SDS-PAGE (3% to 9% acrylamide gradient gel) stained with Coomassie blue under reduced and nonreduced conditions.54 Most studies were performed using Lp(a) containing apo(a) (Mr ∼500 kD) on SDS-PAGE. Native apo(a) was isolated from Lp(a) as described.55 Lp(a) and apo(a) were radiolabeled with 125I using a modification of the iodine monochloride method54,56 to a specific activity of 3.1 × 105 cpm/pmol. In some experiments, Lp(a) was oxidized as described.57 The oxidation state of the Lp(a) was monitored by measuring thiobarbituric acid reactive substances.58 The migration of oxidized and nonoxidized125I-Lp(a) was analyzed on 0.5% native agarose gels (Paragon Lipoprotein “Lipo” electrophoresis kit; Beckman instruments, Inc, Fullerton, CA) by autoradiography. All preparations studied were free of oxidized Lp(a) (see Fig 4). To measure the effect of defensin on the oxidation state of Lp(a),125I-oxidized or nonoxidized Lp(a) (20 nmol/L) was incubated in the presence or absence of defensin (10 μmol/L) in Tris-buffered saline (TBS)/4 mmol/L calcium, and 0.01% Tween 20 (TBS/Ca/T) buffer containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 1 hour at 37°C. Migration of the labeled proteins under native conditions on 0.5% agarose gel was analyzed using autoradiography. Recombinant apo(a) [r-apo(a)], 17K (kringles; Mr ∼525 kD), was prepared as described.59

Antibodies.

Rabbit polyclonal antisera against human TSP-1 was the kind gift of Dr Jack Lawler (Brigham and Womens Hospital, Boston, MA). The IgG fractions of this antisera and normal rabbit sera were isolated using protein-G agarose (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD; catalogue no. 15920-010). Human plasma fibronectin was purchased from Life Technologies (catalogue no. 33016-023); affinity-purified polyclonal sheep IgG antihuman vitronectin was from Enzyme Research Laboratories, Inc (Indianaoplis, IN; catalogue no. SAVN-AP); affinity-purified rabbit IgG antihuman fibronectin was from Sigma Chemical Co (St Louis, MO; catalogue no. F-3648); and bovine lung heparin was from Sigma (catalogue no. H-9133).

Cell Culture and Isolation of Extracellular Matrix (ECM)

Cultures of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) and umbilical vein smooth muscle cells (HVSMC) were prepared and characterized as described.60 Human SMC from descending abdominal aorta were purchased from Clonetics (San Diego, CA). CHO cells deficient in xylosyl transferase (XT−/−)61 were provided by J. Esko (University of California, San Diego, CA) and K. Williams (Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, PA). ECM was prepared as described.62 Briefly, HUVEC or each source of SMC were seeded onto 96-well Falcon Multiwell tissue culture dishes (Becton Dickinson, Lincoln Park, NJ) at an initial density of 2 to 3 × 104 cells/well. Five to 7 days after the cells reached confluency, the monolayer was washed 3 times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The cells were incubated for 3 minutes at 22°C with PBS/0.5% Triton X-100 and then with NH4OH (25 mmol/L) for an additional 8 minutes at 22°C. Detached cells were removed by washing the plate 4 times with TBS containing calcium (10 mmol/L Tris, 150 mmol/L NaCl, pH 7.5, and 4 mmol/L CaCl2; TBS/Ca2+). The matrices contained no intact cells as judged by light microscopy. Matrix-coated wells were dried and stored at −80°C until use. ECM-coated plates were used within 1 week of preparation, with no change in activity. In other experiments, 96-well plates (Immulon 2; Dynatech Labs Inc, Chantilly, VA) were incubated with purified fibronectin (5 μg/mL in TBS/Ca2+) for 12 hours at 4°C and washed as described above before use.

Binding of Lp(a) to ECM or Coated Fibronectin

To measure the binding of Lp(a), wells were coated with HUVEC- or HVSMC-derived ECM or with purified human fibronectin. Unreactive sites were blocked by adding 0.3% BSA in TBS/Ca2+ containing 0.05% Tween-20 (TBS/Ca/T) for 1 hour at 22°C, and the wells were washed 3 times with binding buffer composed of TBS/Ca/T and 0.1% BSA.125I-Lp(a) or 125I-apo(a) was added alone or in the presence of various concentrations of defensin or defensin plus potential inhibitors (eg, heparin and ε-aminocaproic acid [εACA]) in the same buffer for 1 hour at 37°C. Unbound ligand was removed, the wells were washed 4 times with binding buffer, 2 N NaOH was added, and the matrix-associated radioactivity was counted. To measure the rate of Lp(a) elution, 125I-Lp(a) was incubated with cell matrix alone or in the presence of defensin. The matrix was then washed 4 times, binding buffer was added, and the radioactivity eluting into the buffer at 37°C was measured at various times over the next 72 hours. To identify Lp(a) binding sites, HUVEC- or HVSMC-derived matrices were preincubated with the IgG fraction of antibodies to specific matrix proteins (50 μg/mL) or with the same concentration of control IgG for 30 minutes at 22°C.125I-Lp(a) in the presence or absence of defensin was then added for 1 hour at 37°C, the matrices were washed, and the bound radioactivity was measured as described above.

Binding of Defensin to Lp(a)

Binding of defensin to Lp(a) and its components was measured using gel filtration, surface plasmon resonance, and immunoelectron microscopy.

Gel filtration.

Gel filtration experiments were performed under conditions similar to those used to measure binding of Lp(a)/defensin to cell matrices. Specifically, 125I–HNP-1 (0.019 to 10 μmol/L) was incubated alone or in the presence of 10 nmol/L Lp(a) or BSA in TBS/Ca/T (final volume, 60 μL) for 1 hour at 37°C. The proteins were passed over a Bio-spin 30 column (Bio-Gel P-30 polyacrylamide gel, catalogue no. 732-6006; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and the radioactivity in the excluded volume was measured; small proteins like defensin (3.5 kD) are expected to be retained in the these columns (exclusion limit, ∼40 kD). Binding of 125I–HNP-1 to BSA measured in parallel was minimal and was subtracted from each data point as a control for nonspecific interactions.

Surface plasmon resonance.

Binding kinetics of defensin to Lp(a) and to its components was measured using a B2000 optical biosensor (Biacore AB, Uppsala, Sweden).63 This method detects binding interactions in real time and enables association and dissociation rate constants to be estimated. For these studies, Lp(a), native apo(a), LDL, and recombinant apo(a) were coupled to CM5-research grade sensor chip flow cells (Biacore AB) using standard procedures.64 The sensor surface was activated for 7 minutes with an equimolar mixture of 0.1 mol/L N-hydroxysuccinimide/N-ethyl-N′-[3-(dimethylamino) propyl] carbodiimide hydrochloride (Pierce, Rockford, IL) 1:1 (vol/vol) at a flow rate of 5 μL/min. Protein was then immobilized to the sensor surface at a flow rate of at least 10 μL/min, and the unreacted amine groups were blocked with 1 mol/L ethanolamine, pH 8.5. Sensor surfaces were coated with ligands (15 μg/mL) in 10 mmol/L NaAc buffer, pH 4.0. Newly immobilized ligand surfaces were equilibrated with PBS, pH 7.4, 0.005% Tween-20 (binding and running buffer). Surfaces were regenerated after each binding interaction by short pulses (20 to 30 seconds) of 10 mmol/L NaAc buffer, pH 2.5 to 3.0, or 5 mmol/L HCl, pH 2.5. Binding of 0.019 to 10 μmol/L defensin (HNP-1 or HNP-2) was measured at 25°C at a flow rate of 30 μL/min. The bulk shift due to interaction of defensin with similarly activated/inactivated uncoated chips was subtracted from the binding signal at each concentration to correct for nonspecific interactions. Immobilized BSA was used as an additional control for protein binding.

Binding of defensin to sensor surface-immobilized Lp(a), apo(a), or LDL was detected by a change in the refractive index of the solution in immediate contact with the sensor surface as a function of time.65 Kinetic data were evaluated as described previously.66 The ordinate intercept of the extrapolated linear portion of the derivative of the binding signal that corresponds to the signal at steady state in resonance units (RU) was plotted as a function of concentration of defensin in the inserts to Fig 5. At the lower concentrations of defensin, binding at steady state (Req) was also calculated using the BIAevaluation software (version 3.0, 1997; Biacore AB). Values obtained by each method were in excellent agreement. These values were then used to estimate the equillibrium dissociation constants (kds).

Electron microscopy.

Rotary-shadowed samples were prepared by spraying a dilute solution of protein (final concentration, ∼40 μg/mL) in a volatile buffer (0.05 mol/L ammonium formate at pH 7.4) and 70% glycerol onto freshly cleaved mica and shadowing with tungsten followed by deposition of a carbon film in a vacuum evaporator (Denton Vacuum Co, Cherry Hill, NJ).67 68 Ratios of Lp(a) to defensin were generally 1:10 or 1:22, and samples were incubated for 30 minutes at 22°C. A 10× excess of rabbit anti–HNP-1 sera was incubated for an additional 30 minutes at 22°C. All experiments were repeated several times and many micrographs were taken of randomly selected areas to ensure that the results were reproducible and representative. All of the specimens were examined in a Philips 400 electron microscope (Philips Electronic Instruments Co, Mahwah, NJ), usually operating at 80 kV.

Confocal laser scanning microscopy.

Confocal laser scanning microscopy was used to examine the effect of defensin on the endocytosis of Lp(a). Subconfluent monolayers of HUVEC were grown on fibronectin-coated glass coverslips overnight. The cells were washed 3 times with Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Life Technologies) supplemented with 1% BSA. Defensin (10 μmol/L), Lp(a) (40 nmol/L), or defensin plus Lp(a) was added in the same media for 1 hour either at 4°C or at 37°C for 30 minutes. Cells treated with defensin or defensin/Lp(a) in this manner were greater than 95% viable as judged by exclusion of trypan blue. The cells were rinsed in PBS to remove unbound ligands and fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 10 minutes, followed by cold methanol (−20°C) for 8 minutes. The coverslips were incubated with a mouse monoclonal antidefensin antibody (5 μg/mL) and/or affinity-purified rabbit anti-Lp(a) antibody (5 μg/mL; Cortex Biochem, San Leandro, CA; catalogue no. CR9018RP) for 1 hour. Coverslips incubated with the same concentrations of nonimmune mouse sera or IgG isolated from normal rabbit sera served as the negative controls. The Ig-treated cells were washed and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated donkey antirabbit Ig or rhodamine tetramethyl rhodamine isothiocyanate (TRITC)-conjugated donkey antimouse IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA) was added for 30 minutes. Cell nuclei were stained with 2 μg/mL 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA). Immunolabeled cells were sectioned optically using a computer-interfaced, laser-scanning microscope (Leica TCS 4D confocal microscope; Leica, Exton, PA). This equipment is fitted with both an argon and krypton-argon laser, permitting simultaneous analysis of fluorescein and rhodamine chromophores, with the option of rescanning for UV-excitable fluorochromes. The output, which is up to 1,024 × 1,024 pixels, is linked to an image-processing workstation, permitting pixel by pixel quantification, registration, and averaging of multiple images.

Formation of Foam Cells

J774 murine macrophages were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 2 mmol/L glutamine and 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) in 24 Multiwell dishes (Falcon, Plymouth, UK). The cells were washed free of FCS and the medium was replaced with DMEM containing 200 nmol/L native or oxidized Lp(a) in the presence or absence of 10 μmol/L defensin (HNP-2).3H-oleic acid (OA; New England Nuclear, Boston, MA) was added (100 μmol/L) as an oleate:albumin complex (3:1 molar ratio) for 24 hours at 37°C and the incorporation of 3H-OA was measured. To do so, the medium was collected, the cells were washed 4 times with PBS, and 1 mL absolute ethanol was added for 2 hours. The ethanol extract was separated by thin-layer chromatography on silica gels (Analtech, Inc, Newark, DE). Bands were identified with iodine and isolated, and the radioactivity in the cholesterol ester fraction was counted.

RESULTS

We previously reported that leukocyte defensins promote the binding of Lp(a) to cultured human endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells without a concomitant increase in degradation. We investigated 2 possible mechanisms to explain these findings: ie, that defensin promotes the binding and retention of Lp(a) on vascular matrices and/or that defensin promotes the binding of Lp(a) to cellular receptors but protects it from degradation.

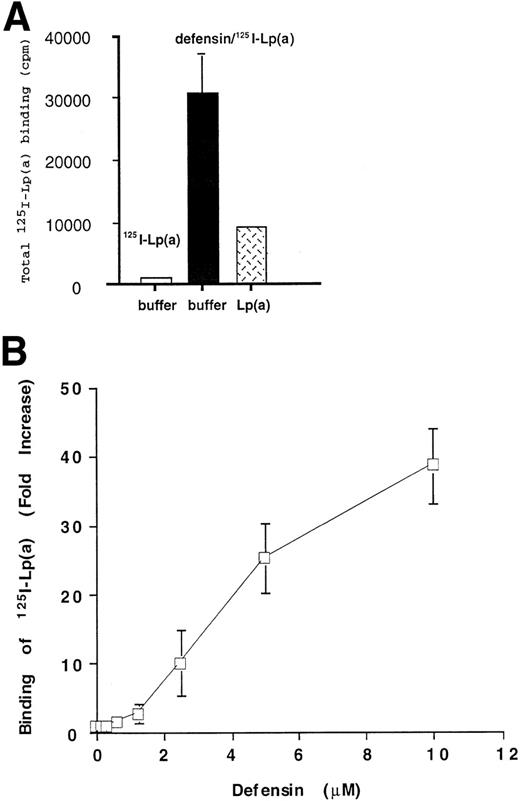

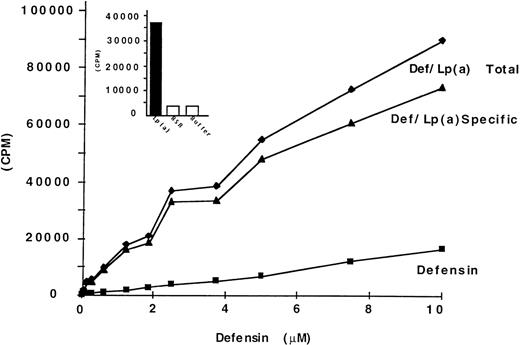

Defensin Promotes Binding of Lp(a) to Endothelial Cell Matrix

We asked first whether defensin promotes the binding and retention of Lp(a) by vascular matrices. Binding of Lp(a) (20 nmol/L) to HUVEC matrix was stimulated approximately 40-fold by 10 μmol/L defensin (Fig 1A). Binding of 125I-Lp(a) in the presence of defensin [defensin/Lp(a)] was inhibited greater than 80% by 20-fold molar excess unlabeled Lp(a) (Fig 1A). Defensin did not stimulate the binding of 125I-Lp(a) in the absence of matrix (not shown). Defensin promoted 125I-Lp(a) binding to HUVEC matrix in a dose-dependent and saturable manner (Fig 1B). Binding of Lp(a) approached saturation at a defensin concentration of 10 μmol/L, consistent with previous results using intact cells.48 50 Identical results were obtained using oxidized125I-Lp(a) or Lp(a) containing the apo(a) isoform (Mr ∼350 kD) and when matrices derived from HVSMC were studied (not shown). The binding of defensin/125I-Lp(a) to matrix was essentially irreversible. Whereas approximately 30% of the bound ligand dissociated from the matrix over the initial 3 hours, there was no further loss over the succeeding 72 hours (Fig 2). Thus, defensin caused a sustained net 40-fold increase in matrix-bound Lp(a).

Defensin promotes the binding of Lp(a) to HUVEC matrix. (A) 125I-Lp(a) (20 nmol/L) or mixtures of defensin (10 μmol/L) plus 125I-Lp(a) (20 nmol/L) were incubated with HUVEC matrix in the presence of buffer (□, ▩) or 20-fold molar excess cold Lp(a) () for 1 hour at 37°C, and the bound radioactivity was measured. The mean ± SD of 3 experiments is shown. This corresponds to an increase in bound Lp(a) from a mean of 2.9 fmol in the absence of defensin to 96 fmol in the presence of defensin. The mean ± SD of 3 experiments is shown. (B)125I-Lp(a) (10 nmol/L) was incubated with HUVEC matrix in the presence of the indicated concentrations of defensin for 1 hour at 37°C, and the bound radioactivity was measured. The data are expressed relative to the binding of 125I-Lp(a) alone. The mean ± SD of 3 experiments is shown.

Defensin promotes the binding of Lp(a) to HUVEC matrix. (A) 125I-Lp(a) (20 nmol/L) or mixtures of defensin (10 μmol/L) plus 125I-Lp(a) (20 nmol/L) were incubated with HUVEC matrix in the presence of buffer (□, ▩) or 20-fold molar excess cold Lp(a) () for 1 hour at 37°C, and the bound radioactivity was measured. The mean ± SD of 3 experiments is shown. This corresponds to an increase in bound Lp(a) from a mean of 2.9 fmol in the absence of defensin to 96 fmol in the presence of defensin. The mean ± SD of 3 experiments is shown. (B)125I-Lp(a) (10 nmol/L) was incubated with HUVEC matrix in the presence of the indicated concentrations of defensin for 1 hour at 37°C, and the bound radioactivity was measured. The data are expressed relative to the binding of 125I-Lp(a) alone. The mean ± SD of 3 experiments is shown.

Defensin and defensin/125I-Lp(a) bind tightly to HUVEC matrix. 125I-Lp(a) (10 nmol/L; □) or 2.5 μmol/L defensin/10 nmol/L 125I-Lp(a) (▪) were incubated with HUVEC matrix as described in the legend to Fig 1 for 1 hour at 37°C. The matrix was washed 4 times with 200 μL binding buffer, 200 μL binding buffer was added for the indicated times, and the bound radioactivity was measured. The mean of 2 experiments performed in triplicate is shown.

Defensin and defensin/125I-Lp(a) bind tightly to HUVEC matrix. 125I-Lp(a) (10 nmol/L; □) or 2.5 μmol/L defensin/10 nmol/L 125I-Lp(a) (▪) were incubated with HUVEC matrix as described in the legend to Fig 1 for 1 hour at 37°C. The matrix was washed 4 times with 200 μL binding buffer, 200 μL binding buffer was added for the indicated times, and the bound radioactivity was measured. The mean of 2 experiments performed in triplicate is shown.

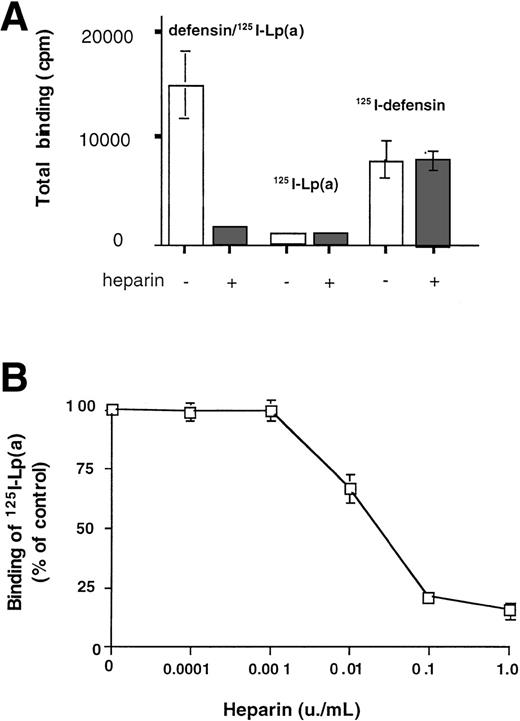

Binding of Lp(a) to matrix in the presence of defensin acquired marked sensitivity to inhibition by heparin (Fig3A; half maximal 0.01 U/mL, Fig 3B). In contrast, the binding to matrix of neither 125I-defensin (2.5 μmol/L) nor125I-Lp(a) (10 nmol/L) added individually was inhibited by heparin at concentrations as high as 6 U/mL. Experiments were then perfomed to evaluate 3 possible explanations for these observations: (1) defensin might form stable complexes with Lp(a) generating heparin-sensitive epitopes that promote binding to matrix; (2) heparin might inhibit the formation of these complexes or block the induced epitope directly; or (3) defensin might neutralize negatively charged residues on the matrix, permitting Lp(a) access to its binding sites.

Binding of defensin/125I-Lp(a) to matrix is heparin sensitive. (A) 125I-Lp(a) (10 nmol/L) or a mixture of defensin (2.5 μmol/L) plus 125I-Lp(a) (10 nmol/L) or125I-defensin (2.5 μmol/L) were incubated with HUVEC matrix in the presence of buffer (□) or heparin (2 U/mL; ▩) for 1 hour at 37°C, and the bound radioactivity was measured. The mean ± SD of 3 experiments is shown. (B) Heparin inhibits the binding of defensin (2.5 μmol/L)/125I-Lp(a) (10 nmol/L) complexes to matrix in a dose-dependent manner. The complexes were incubated with HUVEC matrix in the presence of the indicated concentrations of heparin, and the bound radioactivity was measured. Bound radioactivity is expressed relative to the binding of Lp(a) alone. The mean ± SD of 3 experiments is shown.

Binding of defensin/125I-Lp(a) to matrix is heparin sensitive. (A) 125I-Lp(a) (10 nmol/L) or a mixture of defensin (2.5 μmol/L) plus 125I-Lp(a) (10 nmol/L) or125I-defensin (2.5 μmol/L) were incubated with HUVEC matrix in the presence of buffer (□) or heparin (2 U/mL; ▩) for 1 hour at 37°C, and the bound radioactivity was measured. The mean ± SD of 3 experiments is shown. (B) Heparin inhibits the binding of defensin (2.5 μmol/L)/125I-Lp(a) (10 nmol/L) complexes to matrix in a dose-dependent manner. The complexes were incubated with HUVEC matrix in the presence of the indicated concentrations of heparin, and the bound radioactivity was measured. Bound radioactivity is expressed relative to the binding of Lp(a) alone. The mean ± SD of 3 experiments is shown.

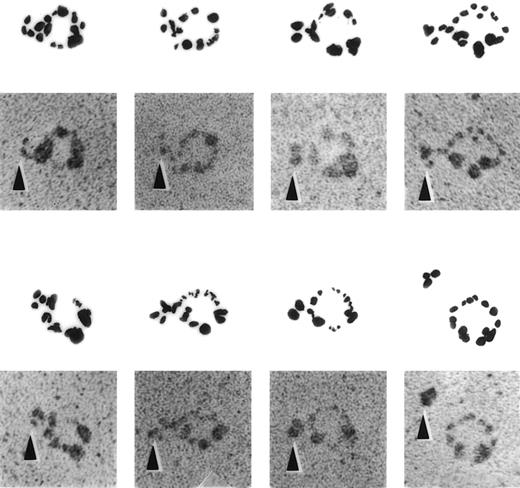

Formation of Stable Complexes Between Defensin and Lp(a)

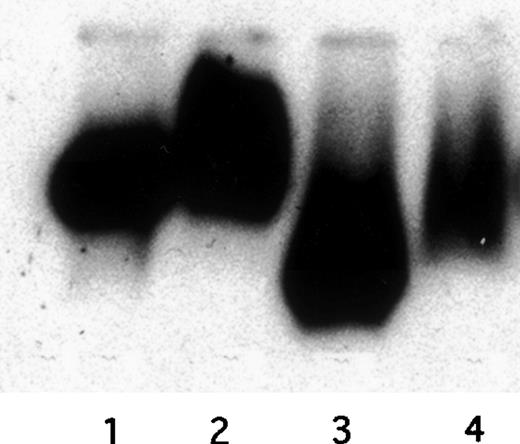

Several approaches were used to determine whether defensin forms complexes with Lp(a), the portion(s) of the lipoprotein involved, and the capacity of such complexes to bind to matrix. Formation of complexes between defensin and Lp(a) was evident by immunoelectron microscopy (Fig 4). Anti-defensin antibody bound to Lp(a) particles preincubated with defensin were readily detected, whereas no binding of the antibodies to Lp(a) alone was seen in this case (Fig 4) or when nonimmune sera was incubated with defensin/Lp(a) mixtures (not shown).

ImmunoEM appearance of defensin/Lp(a) complex. Electron micrographs of defensin/Lp(a) complexes. Lp(a) was incubated alone or in the presence of 1:10 molar ratio of defensin for 30 minutes at 22°C followed by incubation with anti-defensin sera for 30 minutes at 22°C. All specimens were rotary shadowed with tungsten. A gallery of selected examples of individual Lp(a) molecules attached to anti-defensin antibody in the presence and absence (lower panel, far right) of defensin is shown. No binding was seen when nonimmune sera was substituted for anti-defensin sera. The arrows denote the location of the anti-defensin antibodies.

ImmunoEM appearance of defensin/Lp(a) complex. Electron micrographs of defensin/Lp(a) complexes. Lp(a) was incubated alone or in the presence of 1:10 molar ratio of defensin for 30 minutes at 22°C followed by incubation with anti-defensin sera for 30 minutes at 22°C. All specimens were rotary shadowed with tungsten. A gallery of selected examples of individual Lp(a) molecules attached to anti-defensin antibody in the presence and absence (lower panel, far right) of defensin is shown. No binding was seen when nonimmune sera was substituted for anti-defensin sera. The arrows denote the location of the anti-defensin antibodies.

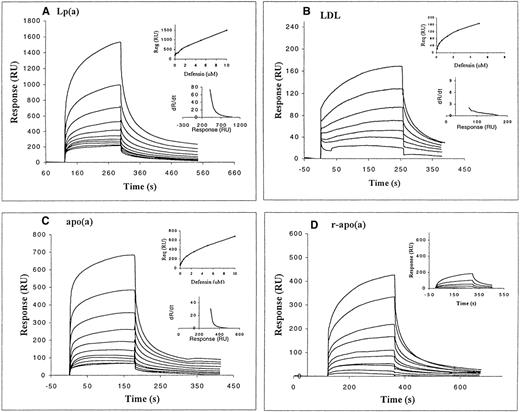

The kinetics of defensin binding to immobilized Lp(a) and its components, LDL and apo(a), was then measured as surface plasmon resonance. Defensin bound to intact Lp(a) in a dose-dependent manner (Fig 5A). Binding to Lp(a) appears to involve higher and lower affinity components. A similar conclusion was evident from the analysis of the dR/dt vs R plots (see inserts to Fig5A through C). Binding of defensin to Lp(a) was readily evident at concentrations well below those at which appreciable binding was observed to blank surfaces. In addition, binding of defensin to immobilized albumin (inset to Fig 5D) and to the amino-terminal fragment of urokinase (not shown) was approximately 10% of the binding to Lp(a) over the same range of concentrations. The first component of binding appeared to reach saturation at a defensin concentration of approximately 600 nmol/L. The apparent stoichiometry of interaction between defensin and Lp(a), estimated from the ratio of immobilized and bound mass proportional to response, exceeded 1 at concentrations of defensin greater than 625 nmol/L. At concentrations of defensin greater than 1.25 μmol/L, binding to an apparently lower affinity site predominated. This signal was not an artifact of coating or self-association of ligand, in that no aggregation of defensin was observed using empty or BSA-coated sensor surfaces. In addition, the same pattern of binding was seen at a lower Lp(a) surface density (400 RU, not shown).

Binding of defensin to Lp(a) and its components assessed using the optical biosensor. Defensin (9 nmol/L to 10 μmol/L) was incubated with immobilized Lp(a) (5,000 RU; A) or its components: LDL (445 RU; B), native apo(a) (1,400 RU; C), and recombinant apo(a) (900 RU; D). The interaction of defensin with a high surface density of immobilized BSA (2,400 RU) is shown in the insert to (D). Both the association and dissociation phases are shown. The inserts in (A) through (C) show both dR/dt × R plots (at 5 μmol/L defensin) and the binding isotherms at equilibrium to each component.

Binding of defensin to Lp(a) and its components assessed using the optical biosensor. Defensin (9 nmol/L to 10 μmol/L) was incubated with immobilized Lp(a) (5,000 RU; A) or its components: LDL (445 RU; B), native apo(a) (1,400 RU; C), and recombinant apo(a) (900 RU; D). The interaction of defensin with a high surface density of immobilized BSA (2,400 RU) is shown in the insert to (D). Both the association and dissociation phases are shown. The inserts in (A) through (C) show both dR/dt × R plots (at 5 μmol/L defensin) and the binding isotherms at equilibrium to each component.

We next asked whether defensin bound to the apo(a) or to the LDL components of Lp(a). The sensorgrams in Fig 5C and D show that defensin bound to both natural and recombinant apo(a) with the high- and low-affinity components seen with intact Lp(a). The maximum binding response was again greater than 1:1. Defensin also bound in a dose-dependent and saturable manner to LDL (Fig 5B). A hyperbolic binding isotherm was obtained, consistent with a single class of binding sites at all concentrations of defensin studied (0 to 5 μmol/L). Binding of defensin to LDL showed a 10-fold lower affinity than binding to isolated apo(a). Analysis of dR/dt versus R plots also suggest that defensin bound to LDL with a simple kinetic. However, the binding capacity of immobilized LDL somewhat exceeded the predicted values for a 1:1 interaction. Dissociation of defensin from the Lp(a) surface was rapid, but the signal did not return to baseline after buffer wash (>450-second-long washes). Defensin dissociated more rapidly from apo(a) (native and recombinant) than from Lp(a), but in each case the dissociation appeared to be biphasic, similar to the dissociation of defensin from Lp(a). Defensin dissociated even more rapidly from immobilized LDL than from either Lp(a) or apo(a) (return to baseline signal ∼300 seconds).

Binding of 125I-defensin to Lp(a) was then assessed under conditions similar to those used to study binding to ECM using gel filtration. A dose-dependent increase in binding of defensin to Lp(a) was observed over the same range of concentrations evident using the optical biosensor approach. Complex formation was again evident at concentrations below those associated with stimulation of matrix binding. At defensin concentrations greater than 1 to 1.5 μmol/L, formation of defensin/Lp(a) complexes (Fig6) closely paralleled matrix binding (Fig 1). Defensin also retarded the migration of unoxidized and oxidized 125I-Lp(a) on native agarose gels (Fig 7). Formation of defensin/Lp(a) complexes was not inhibited by heparin at concentrations as high as 10 U/mL or by 100 mmol/L εACA assessed either by gel filtration or optical biosensor analysis (not shown). This result implies that defensin forms stable soluble complexes with Lp(a) that acquire novel epitopes that enhance their capacity to bind to matrix. Furthermore, the inhibitory effect of heparin occurs after complex formation and before binding to matrix.

Binding of 125I-defensin to Lp(a) assessed by gel filtration. Fixed amounts Lp(a) or BSA (10 nmol/L each) were incubated with the indicated concentrations of125I-defensin (HNP-1) for 1 hour at 37°C. The mixtures were loaded on a Bio-spin 30 columns, and the excluded radioactivity was measured. The amount of 125I-defensin/PBS and the amount of 125I-defensin/BSA in the void volume were identical at each concentration and were taken as measure of nonspecific binding. The insert shows the void volume of columns containing 125I-defensin plus Lp(a), BSA, and buffer.

Binding of 125I-defensin to Lp(a) assessed by gel filtration. Fixed amounts Lp(a) or BSA (10 nmol/L each) were incubated with the indicated concentrations of125I-defensin (HNP-1) for 1 hour at 37°C. The mixtures were loaded on a Bio-spin 30 columns, and the excluded radioactivity was measured. The amount of 125I-defensin/PBS and the amount of 125I-defensin/BSA in the void volume were identical at each concentration and were taken as measure of nonspecific binding. The insert shows the void volume of columns containing 125I-defensin plus Lp(a), BSA, and buffer.

Migration of defensin/125I-Lp(a) complexes on native gels. Unoxidized and oxidized 125I-Lp(a) (20 nmol/L) was incubated with defensin (HNP-1; 10 μmol/L) or buffer for 1 hour at 37°C, and the migration of the labeled lipoproteins towards the positive electrode on 0.5% agarose gels was analyzed using autoradiography. Lane 1, native Lp(a); lane 2, Lp(a)/defensin; lane 3, oxidized Lp(a); lane 4, oxidized Lp(a)/defensin.

Migration of defensin/125I-Lp(a) complexes on native gels. Unoxidized and oxidized 125I-Lp(a) (20 nmol/L) was incubated with defensin (HNP-1; 10 μmol/L) or buffer for 1 hour at 37°C, and the migration of the labeled lipoproteins towards the positive electrode on 0.5% agarose gels was analyzed using autoradiography. Lane 1, native Lp(a); lane 2, Lp(a)/defensin; lane 3, oxidized Lp(a); lane 4, oxidized Lp(a)/defensin.

Characterization of Defensin/Lp(a) Binding to Matrix

Studies were then performed to identify the binding site(s) for defensin/Lp(a) complexes in matrix based on the inhibitory effect of heparin. One set of potential binding domains are proteoglycan components of the matrix. To examine this possibility, we measured the binding of defensin/125I-Lp(a) to matrices derived from a CHO cell line (XT−/−) that does not synthesize heparan or chondroitin suflate-containing proteoglycans. Binding of defensin/125I-Lp(a) to XT−/− matrix was reduced by only 30% compared with matrix from control CHO cells (not shown).

A second set of potential binding sites includes matrix-associated proteins that contain heparin binding domains. In accord with this, binding of defensin/Lp(a) to matrix was inhibited 63.3% ± 3.1% by anti-fibronectin antibodies (P < .0001 v control Ig 15.4% ± 4.7%), whereas binding was little affected by antibodies to 2 other heparin-binding matrix proteins: thrombospondin (24.3%,P > .05 v control Ig) and vitronectin (0% ± 1.5%, P > .05). Anti-fibronectin antibodies also inhibited the binding of defensin/Lp(a) complexes to matrix derived from HVSMC grown in the absence of exogenous fibronectin (not shown).

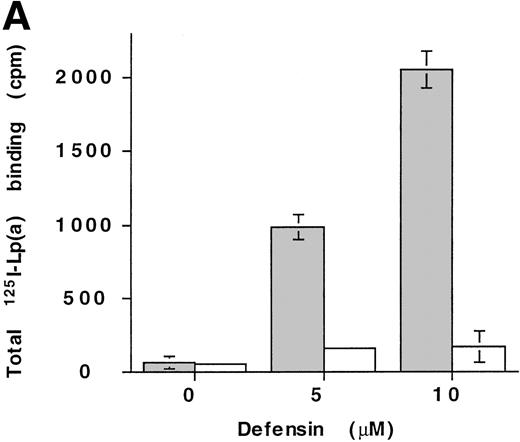

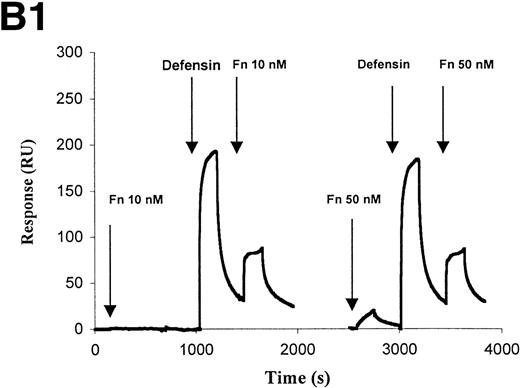

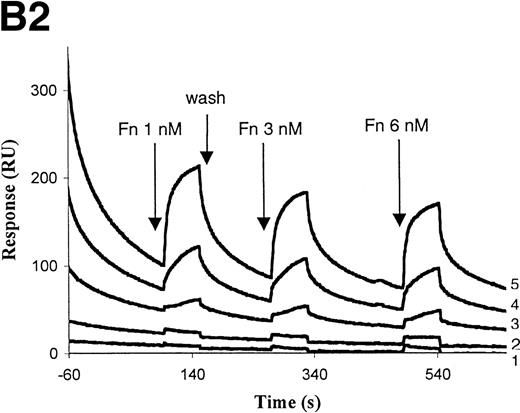

The interaction of defensin/Lp(a) and defensin/apo(a) with fibronectin was then studied in more detail. Defensin (5 to 10 μmol/L) stimulated the binding of 125I-Lp(a) to fibronectin-coated microtiter wells greater than 30-fold, but had minimal effect on binding to albumin-coated wells (Fig8A). Stimulation of apo(a) and Lp(a) binding to fibronectin by defensin was also evident using optical biosensor analysis (Fig 8B). Fibronectin (10 nmol/L) bound to apo(a) only in the presence of defensin (Fig 8B1). Defensin also stimulated the binding of Fn at concentrations (50 nmol/L) at which direct binding to apo(a) could not be detected. Binding of Fn to Lp(a) also depended on the presence of defensin and increased in a dose-dependent manner (Fig 8B2).

Defensin stimulates the binding of Lp(a) to purified fibronectin. (A) Solid-phase radioligand binding. Microtiter wells were coated with 5 μg/mL fibronectin (▩) or BSA (□), unreactive sites were blocked with 0.3% BSA, and the binding of125I-Lp(a) (10 nmol/L) alone or in the presence of the indicated concentrations of defensin was measured. The mean ± SD of 2 experiments performed in triplicate is shown. (B) Surface plasmon resonance. (B1) Immobilized apo(a) (960 RU) was incubated with fibronectin alone (10 and 50 nmol/L) or after preincubation of the chip with 5 μmol/L defensin. The surface was regenerated at 2,000 seconds, ie, between the 2 sets of incubation with fibronectin. (B2) Immobilized Lp(a) was preincubated with defensin (0, 312, 625, 1,250, and 2,500 nmol/L; sensorgrams 1 through 5, respectively), the chip was washed for 3 minutes, and fibronectin was injected at the indicated concentrations with the appropriate wash steps between injections. Binding of fibronectin to Lp(a) was not detected at concentrations of defensin below 0.625 μmol/L.

Defensin stimulates the binding of Lp(a) to purified fibronectin. (A) Solid-phase radioligand binding. Microtiter wells were coated with 5 μg/mL fibronectin (▩) or BSA (□), unreactive sites were blocked with 0.3% BSA, and the binding of125I-Lp(a) (10 nmol/L) alone or in the presence of the indicated concentrations of defensin was measured. The mean ± SD of 2 experiments performed in triplicate is shown. (B) Surface plasmon resonance. (B1) Immobilized apo(a) (960 RU) was incubated with fibronectin alone (10 and 50 nmol/L) or after preincubation of the chip with 5 μmol/L defensin. The surface was regenerated at 2,000 seconds, ie, between the 2 sets of incubation with fibronectin. (B2) Immobilized Lp(a) was preincubated with defensin (0, 312, 625, 1,250, and 2,500 nmol/L; sensorgrams 1 through 5, respectively), the chip was washed for 3 minutes, and fibronectin was injected at the indicated concentrations with the appropriate wash steps between injections. Binding of fibronectin to Lp(a) was not detected at concentrations of defensin below 0.625 μmol/L.

We then asked whether defensin induced the binding of apo(a) to immobilized fibronectin and ECM. Defensin stimulated the binding of125I-apo(a) to fibronectin and to cell matrix greater than 20-fold and approximately 6-fold, respectively (Fig 9A and C), which is less than the stimulation seen with Lp(a). However, binding of both defensin/apo(a) and defensin/Lp(a) to ECM were comparably sensitive to heparin but not to εACA (Fig 9A and B). Binding of defensin/apo(a) and defensin/Lp(a) complexes to fibronectin were somewhat more resistant to heparin than was binding to matrix (Fig 9C and D). However, binding of defensin/Lp(a) to fibronectin was more resistant to εACA than the binding of defensin/apo(a) (Fig 9C and D).

Defensin stimulates the binding of125I-apo(a) to HUVEC matrix and to fibronectin. Complexes composed of 5 μmol/L defensin/20 nmol/L 125I-apo(a) were incubated with HUVEC matrices (A) or well coated with 5 μg/mL fibronectin (C) for 1 hour at 37°C alone or in the presence of 100 mmol/L EACA or 2 U/mL heparin, and the bound radioactivity was determined and expressed as described above. The binding of125I-Lp(a)/defensin complexes to cell matrix (B) and to fibronectin (D) was performed under the same conditions as described above. The mean ± SD of 3 experiments performed in triplicate is shown.

Defensin stimulates the binding of125I-apo(a) to HUVEC matrix and to fibronectin. Complexes composed of 5 μmol/L defensin/20 nmol/L 125I-apo(a) were incubated with HUVEC matrices (A) or well coated with 5 μg/mL fibronectin (C) for 1 hour at 37°C alone or in the presence of 100 mmol/L EACA or 2 U/mL heparin, and the bound radioactivity was determined and expressed as described above. The binding of125I-Lp(a)/defensin complexes to cell matrix (B) and to fibronectin (D) was performed under the same conditions as described above. The mean ± SD of 3 experiments performed in triplicate is shown.

Effect of Defensin on Subcellular Distribution of Lp(a) and Foam Cell Formation

We next asked whether defensin altered the internalization of Lp(a) by cells that express matrix. HUVEC were incubated with defensin and Lp(a), alone or in combination, at 4°C or at 37°C, and the internalization of each ligand was analyzed by confocal microscopy using monospecific antibodies (Fig 10). Cell monolayers were sectioned optically to determine the intracellular distribution of defensin and Lp(a). To do so, the cells were colabeled with the nuclear dye DAPI. The center of the cells in the z-axis was then defined by the optical section containing nuclei with the widest diameters. Defensin localized to cell surface at 4°C (not shown) but was found diffusely throughout the cytoplasm at 37°C (Fig 10C). Under the same conditions, Lp(a) was found primarily in intracellular granules (Fig 10B). In contrast, a significant proportion of defensin and Lp(a) remained associated at the cell periphery when added together (compare Fig 10C and D). In cotreated cultures (Fig 10D), it was evident that defensin was concentrated in diffuse bands at the cell surface in conjunction with clusters of Lp(a), whereas the overall brightness of interacellular defensin/Lp(a) immunoreactivity was diminished. No staining was observed with control IgGs (Fig 10A).

Subcellular distribution of defensin, Lp(a), and Lp(a)/defensin complexes in HUVECs as assessed by confocal microscopy. HUVECs incubated with either Lp(a) (50 nmol/L; B) or defensin (10 μmol/L; C) or coincubated with defensin and Lp(a) (D) for 30 minutes at 37°C and then analyzed by confocal microscopy using polyclonal Lp(a) antibodies followed by FITC-conjugated antirabbit IgG (detected as green) and/or a monoclonal antihuman defensin followed by rhodamine TRITC-conjugated donkey antimouse IgG (detected as red). Normal rabbit IgGs served as control, as shown in (A). Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI (detected as blue). Colocalization of defensin and Lp(a) was assessed by double staining (D) and results in a yellow color (arrows).

Subcellular distribution of defensin, Lp(a), and Lp(a)/defensin complexes in HUVECs as assessed by confocal microscopy. HUVECs incubated with either Lp(a) (50 nmol/L; B) or defensin (10 μmol/L; C) or coincubated with defensin and Lp(a) (D) for 30 minutes at 37°C and then analyzed by confocal microscopy using polyclonal Lp(a) antibodies followed by FITC-conjugated antirabbit IgG (detected as green) and/or a monoclonal antihuman defensin followed by rhodamine TRITC-conjugated donkey antimouse IgG (detected as red). Normal rabbit IgGs served as control, as shown in (A). Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI (detected as blue). Colocalization of defensin and Lp(a) was assessed by double staining (D) and results in a yellow color (arrows).

These studies suggest that defensin promotes the retention of Lp(a) on the extracellular matrix of cells and inhibits endocytosis/degradation. Lp(a) induces a chemotactic factor for monocytes in HUVECs.69 Lp(a) retained on the matrix is also subject to oxidation and uptake by scavenger receptors and, thereby, may promote foam cell formation. To examine the effect of defensin on cholesterol ester formation, J774 rat macrophages were incubated with unoxidized and oxidized Lp(a) in the presence and absence of defensin and the incorporation of 3H-oleic acid was measured. Defensin/oxidized Lp(a) stimulated the incorporation of3H-oleic acid 4- to 5-fold but had minimal effect in the absence of oxidation (not shown). Thus, defensin promotes the incorporation of oleic acid into cellular cholesterol, an important constituent of foam cells.

DISCUSSION

Inflammatory changes within the vessel wall may promote the retention of Lp(a) and the development of atherosclerosis. In accord with this possibility, we have found that α-defensins, most likely released by activated or senescent neutrophils, are present in human atherosclerotic lesions,47,48 bind to cultured endothelial and vascular smooth muscle cells,48,50 and promote the binding of Lp(a).48 However, no concomitant increase in Lp(a) degradation was seen, raising the possibility that defensin diverts the lipoprotein to compartments, such as the matrix, wherein degradation occurs slowly, if at all, or that defensin impedes normal cellular degradative mechanisms. The results of the present study provide support for both possibilities.

Defensin stimulates the binding of Lp(a) to matrices derived from cultured human endothelial cells and vascular smooth muscle cells in a dose-dependent and saturable manner. Binding of Lp(a) to matrix was enhanced approximately 40-fold at optimal concentrations of defensin, an enhancement that is several fold higher than was observed with cell monolayers.48 The enhancement occurred at concentrations of Lp(a) (1 to 30 nmol/L) that are well within the range found in human plasma70 and at concentrations of defensin (10 μmol/L) found in plasma during bacterial infection.41,42 The concentrations of defensin in the vasculature, especially in the vicinity of degranulating neutrophils, are unknown, but may be even higher based on their content in sputum and empyema fluid.71,72 Binding of Lp(a) to vascular matrix in the presence of defensin was essentially irreversible over 72 hours, resulting a marked increase in the total amount of lipoprotein retained. The biochemical changes that prevent the lipoprotein from dissociating from the matrix in the presence of defensin require additional study, but are in accord with a recent finding that covalent linkages develop between Lp(a) and both fibrin and cell surfaces.73

Defensin may promote Lp(a) binding through several interrelated mechanisms. First, defensin may bind directly to both the lipoprotein and to the matrix, providing a bridge between the surfaces. Second, defensin may bind to the matrix, blocking sites that otherwise limit lipoprotein deposition. Third, defensin may bind to Lp(a), generating novel epitopes that are not present in either substituent. Although our studies do not permit any of these possibilities to be excluded, it is evident from 3 independent methods of analysis (immunoelectron microscopy, optical biosensor analysis, and gel filtration chromatography) that defensin binds directly to Lp(a). Defensin/Lp(a) complexes acquire novel characteristics that differ from those of either Lp(a) or defensin alone. The subcellular distribution of defensin/Lp(a) on the surface of HUVECs differs markedly from that of Lp(a). Defensin/Lp(a) complexes also migrate differently from Lp(a) on native gels, suggesting that defensin alters the electrostatic characteristics of the lipoprotein. Binding of the complexes to matrix is also more sensitive to inhibition by heparin than is binding of Lp(a) alone.

Binding of defensin to Lp(a), assessed by surface plasmon resonance, was judged as specific by the fact that little binding to other proteins was observed under the same conditions. Analysis of the sensorgrams demonstrate that binding of defensin to Lp(a) cannot be described by a simple one to one model. Rather, the existence of at least 2 classes of binding sites on Lp(a) is suggested by the dR/dt plots, although other models are possible. The most straightforward explanation for the observed pattern is that at least one class of binding sites is present on apo(a) and another on LDL. In support of this possibility, defensin bound with high affinity to both natural and recombinant apo(a) and with lower affinity to immobilized LDL, although we did not attempt to distinguish between the contribution of apoB and the lipid core in this study. The contribution of LDL to the binding of defensin/Lp(a) to cell matrix was also quite apparent as defensin stimulated the binding of Lp(a) to a considerably greater extent than it did the binding of apo(a). Also, the effect of defensin on the binding of Lp(a) was achieved at concentrations in the range of its affinity for LDL.

The possibility that defensin binds to apo(a) and to LDL is consistent with known features of its structure and binding properties. Binding of defensin to each component may help to explain the intense signal that was generated, which was somewhat surprising in view of its small mass. The optical biosensor and gel filtration experiments indicate that apo(a) can accommodate more than 1 molecule of defensin. Apo(a) is rich in sialic acid and contains multiple kringle-IV repeats, several of which may bind defensin through exposed arginines. Alternatively, the intense biosensor signal may result from formation of homopolymers in the lipid core, analagous to the pores formed by defensin within cell membranes.74 However, the observation that binding to LDL approached saturation makes it more likely that defensin binding to higher affinity sites in apo(a) cause conformational changes in the apoprotein that facilitate its binding to additional, lower affinity sites. Studies are in progress to identify the binding sites for defensin in Lp(a) in greater detail.

Binding of defensin to apo(a) and Lp(a) was also evident by gel filtration performed under the conditions used to measure binding to cell matrix. These experiments confirmed the dose-dependent nature of defensin binding to Lp(a), excluding the possibility that the biosensor findings were artifacts caused by immobilization of Lp(a) on the sensor chip. These experiments also suggest that the enhanced binding to the matrix occurs only when multiple molecules of defensin are bound to Lp(a). Indeed, there appears to be a threshold below which binding of Lp(a) to matrix is unaffected by defensin and above which there is a close correlation between the molar ratio of defensin to Lp(a) and matrix binding. Cationization of Lp(a) by defensin may lead to the formation of stable salt bridges with anionic components of the matrix. An alternative explanation is that defensin induces neodeterminants in Lp(a) that bind directly to matrix and are recognized by heparin. This would explain why binding of defensin/Lp(a) to matrix was inhibited at concentrations at which little or no effect was seen on either substituent alone, why inhibition of defensin/Lp(a) binding was greater than could be explained by a total absence of heparan- or chondroitin sulfate-containing proteoglycans in the matrix, and why antibodies to matrix proteins with heparin binding domains, such as thrombospondin and vitronectin, did not inhibit binding.

Our data indicate that defensin promotes binding of Lp(a) to fibronectin21,75,76: binding of defensin/Lp(a) to cell matrix was inhibited by anti-fibronectin antibody; defensin increased the binding of Lp(a) to purified fibronectin greater than 30-fold; and trimolecular complexes containing Lp(a) [or apo(a)], defensin, and fibronectin were detected using the optical biosensor at concentrations at which little or no binding of Lp(a) alone was seen. The fact that binding of defensin/Lp(a) to soluble fibronectin was reversible, whereas binding to cell matrix was not, is consistent with the conformational changes that occur when the protein is bound to cells or is incorporated into the matrix.77 Additional studies will be required to identify the binding site(s) in fibronectin for defensin and defensin/Lp(a).

Binding of defensin/Lp(a) complexes to fibronectin altered the subcellular trafficking of Lp(a) as viewed by confocal microscopy. Defensin bound to the surface of HUVEC at 4°C but was present diffusely throughout the cytoplasm at 37°C, in accord with functional data reported by others.78 The presence of Lp(a) within endocytic granules was readily evident, also in accord with functional data reported in this cell type.52 In contrast, defensin clearly increased the amount of Lp(a) bound to the cell surface, confirming our previous studies.48 Furthermore, the resultant defensin/Lp(a) complexes were coclustered on the cell periphery and minimal internalization of either component was seen when the incubation was performed at 37°C. This finding helps to explain our previous observation that the increase in Lp(a) binding in the presence of defensin is not accompanied by an increase in degradation.48 This interpretation is also supported by the finding that defensin increased the the incorporation of oleic acid into the cellular pool of cholesterol in macrophages. Retention of Lp(a) in the pericellular matrix induced by defensin may also enhance its antifibrinolytic activity. Defensin may also inhibit the binding of Lp(a) to the very low density lipoprotein receptor52 or other receptors57 that mediate endocytosis of the lipoprotein, or defensin may otherwise interfere with mobility of these receptors in the cell membrane. On the other hand, these experiments can also be viewed as indicating that Lp(a) prevents the internalization of defensin, which is cytotoxic to mammalian cells at high concentrations, thereby limiting the potentially injurious effects of cationic proteins released from activated neutrophils and other cell types during inflammatory reactions.79 Additional investigation will be required to analyze the mechanism by which defensin alters Lp(a) trafficking in greater detail and to determine the biologic importance of this pathway.

Supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grant No. HL5810.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Address reprint requests to Douglas B. Cines, MD, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, 513 A Stellar-Chance, 422 Curie Blvd, Philadelphia, PA 19104; e-mail: dcines@mail.med.upenn.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal