Abstract

The role of urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA) and its receptor (uPAR) in fibrinolysis remains unsettled. The contribution of uPA may depend on the vascular location, the physical properties of the clot, and its impact on tissue function. To study the contribution of urokinase within the pulmonary microvasculature, a model of pulmonary microembolism in the mouse was developed. Iodine 125 (125I)–labeled fibrin microparticles injected intravenously through the tail vein lodged preferentially in the lung, distributing homogeneously throughout the lobes. Clearance of125I-microemboli in wild type mice was rapid and essentially complete by 5 hours. In contrast, uPA−/− and tissue-type plasminogen activator tPA−/− mice, but not uPAR−/− mice, showed a marked impairment in pulmonary fibrinolysis throughout the experimental period. The phenotype in the uPA−/− mouse was rescued completely by infusion of single chain uPA (scuPA). The increment in clot lysis was 4-fold greater in uPA−/− mice infused with the same concentration of scuPA complexed with soluble recombinant uPAR. These data indicate that uPA contributes to endogenous fibrinolysis in the pulmonary vasculature to the same extent as tPA in this model system. Binding of scuPA to its receptor promotes fibrinolytic activity in vivo as well as in vitro. The physical properties of fibrin clots, including size, age, and cellular composition, as well as heterogeneity in endothelial cell function, may modify the participation of uPA in endogenous fibrinolysis.

Introduction

Tissue-type plasminogen activator (tPA) and urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA) are primarily responsible for the activation of plasminogen in vivo.1 Divergent roles for tPA and uPA in fibrinolysis have been postulated.2 tPA has been implicated in fibrin degradation within the vasculature, whereas uPA has been assumed to act primarily in the context of cell surfaces to promote cell adhesion and migration through matrices and lysis of fibrin deposited at extravascular sites.3 It has been reported, for example, that uPA−/− and wild-type (WT) mice show no difference in the rate of resolution of pulmonary emboli formed when human plasma clots are injected through the jugular vein.2 Furthermore, tPA−/− mice exhibited a defect in clot lysis induced by endothelial cell injury, whereas uPA−/− mice showed no impairment of either thrombus formation or clot lysis.4

Yet these observations are difficult to reconcile with those of others suggesting that endogenous uPA does contribute to intravascular fibrinolysis. For example, fibrin deposits have been identified in the intestine, hepatic sinusoid, and ulcerated skin of uPA−/− mice, but not tPA−/−mice.2 Mice with combined tPA and uPA deficiency suffer more extensive intravascular fibrin deposition in these same tissues than do tPA−/− mice.2 The uPA−/− mice injected with endotoxin develop more extensive venous thrombi2 and show more extensive intravascular and extravascular deposition of fibrin in the lungs and other tissues after oxygen deprivation than do WT mice.5Moreover, a strong correlation has been observed between the reduction in uPA messenger RNA (mRNA) and fibrin deposition and/or dissolution in WT mice injected with endotoxin.6 uPA is also required for endothelial cells to activate plasminogen in certain experimental settings.7

This seemingly conflicting evidence as to the role of uPA in fibrinolysis may reflect important differences in the pathophysiology of the events being studied. For example, investigations showing no role for uPA in endogenous fibrinolysis involved either direct vascular injury accompanied by endothelial cell desquemation4 or occlusion of larger vessels,2 whereas fibrin has been detected within the microvasculature of uPA−/− mice after a challenge with endotoxin or hypoxia.5,6 Such occlusive thrombi require a prolonged time to undergo lysis and may cause mechanical injury to the underlying endothelium, induce hypoxia locally, and thereby inhibit the expression of uPA.5 6Inhibition of uPA expression might well negate any potential differences between uPA−/− or UPA receptor-deficient mice (uPAR−/−), and WT mice would, therefore, not preclude involvement of uPA in the clearance of smaller fibrin clots that develop commonly as a result of inflammation, nonlethal trauma, or other procoagulant events in the microvasculature.

Similarly, the role of uPAR in fibrinolysis remains unclear. Several groups reported that uPAR promotes the activity of uPA on cell surfaces and in solution in vitro.8-10 Yet, inactivation of theuPAR gene in mice does not appear to affect endogenous fibrinolysis11,12 or lysis of clots injected through the jugular vein.13 However, the finding of fibrin deposits in hepatic sinusoids of uPAR−/−/tPA−/− mice, but rarely in tPA−/− mice, suggests that the absence of uPAR may predispose to thrombosis in some settings.12,13Moreover, mice transfected with murine uPA clear fibrin deposits from pulmonary alveoli more effectively than those transfected with human uPA, compatible with the species specificity of protease binding to uPAR.14

To examine the role of endogenous uPA and uPAR in fibrinolysis in the absence of overt vascular injury, we developed an experimental model of pulmonary microembolism. This model offers the advantage that the vessel wall is spared mechanical or ischemic injury as oxygen is supplied to the pulmonary microvasculature primarily by ventilation rather than by perfusion. The relatively rapid rate of resolution of the microemboli also limits secondary effects induced by the clot itself on tissue oxygenation and tissue metabolism. The results of this study show for the first time that endogenous uPA is as important as tPA in fibrinolysis in the microvasculature of the lung. The data also indicate that clot lysis is accelerated by providing uPA in association with its receptor.

Materials and methods

Preparation of radio-labeled fibrinogen

Plasminogen-depleted human fibrinogen (FIB 1, 1310; Enzyme Research Laboratories, South Bend, IN) was radio-labeled with iodine 125 125I (NEN; Life Sciences, Boston, MA) using IodoGen (Pierce, Rockford, IL) per the manufacturer's instructions. The free iodine was removed using a Bio-Spin 30 column (Bio-Rad Laboratory, Hercules, CA).

Preparation of fibrin microparticles

Whole blood from healthy volunteers was collected in citrate (final concentration, 0.32%). Plasma was isolated by centrifugation at 1200g. Approximately 30 × 106 cpm125I-fibrinogen was added to a solution containing 1.4 mL freshly isolated human plasma supplemented with 0.4 mL unlabeled fibrinogen (final concentration, 10 mg/mL) in a glass tube. Final concentrations of 20 mmol/L calcium chloride (CaCl2) and 0.2 U/mL human thrombin (Sigma Chemical, St Louis, MO) were added for 1 hour at room temperature, and the clots were allowed to mature overnight at 4°C. All subsequent steps were performed at 4°C. The fibrin clots were decanted on a plastic lid and cut into small pieces, which were resuspended in 2 mL Krebs-Ringer bicarbonate buffer (KRB) comprising 119 mmol/L sodium chloride (NaCl), 4.7 mmol/L potassium chloride (KCl), 1.2 mmol/L magnesium sulfate (MgSO4), 1.3 mmol/L CaCl2, 25 mmol/L NaHCO3, and 1.2 mmol/L KH2PO4.

The clots were homogenized at 2600 rpm for 1 minute using a PT-10/35 Polytron homogenizer (Brinkmann Instruments, Westbury, NY). After the first homogenization step, the samples were centrifuged at 2000g for 15 minutes. The supernatant was removed, and the residual particles were pooled and resuspended in KRB. This procedure was repeated two more times. After the final homogenization, the fibrin microparticles were suspended in 8 mL KRB–bovine serum albumin (BSA) (3 mg/mL). The suspension was sedimented at 4°C for 5 minutes to eliminate the largest particles, and 4 mL from the supernatant was used as the final preparation of microparticles. The suspension of125I-microparticles was divided into 200-μL aliquots that were stored at 4°C and used within 48 hours. Random aliquots were selected to characterize the size distribution of the microparticles using a ZM Coulter counter (Coulter Electronics, Hialeah, FL). To study the extent of fibrin cross-linking in the microparticles, the final pellet was solubilized as previously described.15 Briefly, samples were resuspended in 40 mmol/L sodium phosphate in 9 mol/L urea, 3% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), and 3% β-mercaptoethanol and heated at 37°C for 15 minutes to completely dissolve the clots. The samples were boiled for 5 minutes and were subjected to electrophoresis on 10% SDS-PAGE (polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis). Solubilized fibrin (10 μg) or an equal number of counts of radio-labeled clots were loaded into each lane. Unlabeled fibrin clots were stained with Coomassie blue dye, while samples labeled with 125I were exposed to Kodak BioMax ML film (Eastman Kodak Company, Rochester, NY).

Mice

The following mice were used in the study: mice heterozygous for uPAR deficiency (gift of J. Degen and T. Bugge, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH; uPA−/− and tPA−/− mice on a C57/black-6 background, WT C57/black-6 mice, and WT Balb/c mice (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA); and uPA−/− mice on a 25% C57 black-6/75% Swiss background and their littermate controls (gift of P. Carmeliet, Leuven, Belgium). uPAR−/− mice and WT littermate controls were generated and genotyped as previously described.13All mice weighed 20-35 g at the time of the study. No difference in the intrinsic lysis of pulmonary microemboli was observed between WT mice in either genetic background or on a totally unrelated (Balb/c) background or between male and female mice from the same genetic background.

Distribution and lysis of 125I-fibrin microparticles

125I-fibrin microparticles (200 μL aliquots containing 15-30 000 cpm) were resuspended by pipetting several times just prior to extraction into a 27.5-gauge syringe. The mice were injected via the tail vein and returned to their cages until sacrifice. At 10 and 30 minutes and 1, 3, and 5 hours after injection, the mice were anesthetized using metofane, and blood (300-500 μL) was withdrawn by retro-orbital puncture into a heparinized microcapillary tube. The mice were then killed by cervical dislocation. The major organs were harvested immediately, rinsed in saline, and dried on Whatman paper, and the radioactivity in each tissue was measured (EG&G Wallace, Gaithersburg, MD). The exact dose (cpm) injected into each mouse was calculated by subtracting the residual radioactivity remaining in the tube, syringe, and injection site (tail) after administration. The tail counts from each mouse were used to verify the adequacy of injection. In some experiments, the lungs were harvested from treated and untreated mice 10 minutes after injection of microemboli and fixed by immersion overnight at 21°C in 10% neutral buffered formalin. Serial sections were stained exactly as described16 using 5 μg/mL mouse primary monoclonal antibody (mAb) to human fibrin (No. 350, American Diagnostica, Greenwich, CT) or a nonimmune immunoglobulin G1(IgG1) control. In another set of experiments, the lungs were exposed to x-ray film to determine the distribution of radioactivity. In a third series of experiments, the individual lobes from each lung were isolated and counted for radioactivity.

Lung injury by microparticles

Lung injury was assessed by measuring neutrophil infiltration and tissue edema. Neutrophil infiltration in the lungs of mice injected with microparticles was measured as described.17 Briefly, the mice were killed and perfused with approximately 10 mL phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) via the right ventricle until there was no visible blood in the exiting fluid. The lungs were then removed immediately and placed in ice-cold 0.1 mol/L K2HPO4 buffer (pH 7.0). Lung tissues were homogenized using a Teflon homogenizer for 30 seconds in 1 mL ice-cold K2HPO4 buffer and centrifuged at 40 000g for 30 minutes at 4°C. The pellet was resuspended in 1 mL buffer and sonicated for 90 seconds. The slurry was centrifuged for an additional 10 minutes at 12 000g, and the myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity in the supernatant was measured. To do so, 0.1 mL of each sample was added to 0.3 mL Hank buffered salt solution (HBSS) containing 0.25% BSA, 50 μL O-Dianisidine (1.25 mg/mL) (Sigma), and 50 μL hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) (0.05%). The reaction was stopped after 15 minutes by adding 50 μL 1% sodium azide (Sigma), and the absorbance at 460 nm was measured. We defined 1 unit MPO activity as the quantity that converted 1 μmol H2O2 per minute at 25°C. Pulmonary vascular permeability was assessed by measuring the “wet” to “dry” (wet:dry) ratio of the lung. To do so, the lungs were dissected free from the heart, trachea, and main bronchi, blotted, weighed, and dried for 48 hours at 60°C. The ratio of wet lung weight to dry lung weight was calculated.

Lysis of plasma clots by scuPA/suPAR

Recombinant suPAR was generated and characterized as described previously.8,18 We added 25 nmol/L recombinant human scuPA (gift of J. Henkin, Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, IL) or preformed equimolar complexes of suPAR and scuPA (25 nmol/L each) to 200 μL125I-fibrin–labeled human plasma clots placed in 400 μL human, mouse, or rat plasma at 37°C, and the radioactivity in the supernatant was measured at the indicated time points.20Supplementation of plasma clots with 10 mg/mL fibrinogen had no effect on the rate of lysis by urokinase.8 19

Recovery experiments

We anesthetized uPA−/− or WT mice by an intraperitoneal injection of 50 mg/kg pentobarbital sodium. A polyethylene tube (PE 10; Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA) siliconized with Sigmacote (Sigma) and washed with PBS was cannulated into the jugular vein. The mice received an infusion of scuPA alone, scuPA complexed with suPAR, or PBS using a PHD 2000 multisyringe pump (Harvard Apparatus) at a rate of 15 μL/min for 5 minutes.125I-microparticles were then injected into the tail vein as described, and the rate of infusion was continued at a rate of 5 μL/min for an additional 60 minutes. The mice were kept under anesthesia throughout the experiment. At the completion of the infusion, the mice were killed, and the tissues were harvested as described above and counted for radioactivity. The endogenous degradation of 125I-microemboli in WT mice infused with PBS for 1 hour versus 10 minutes was defined as 100% fibrinolysis. The radioactivity in the lungs of uPA−/− and WT mice injected with 125I-microemboli at 10 minutes were identical and defined as baseline. The fibrinolytic activity of PBS, scuPA, or scuPA/suPAR infused into uPA−/− mice for 1 hour was expressed relative to these 2 parameters.

To follow the biodistribution of scuPA, the same experimental format was followed except that the mice were injected with unlabeled fibrin microparticles and infused with either 0.125 mg/kg/h125I-scuPA or 125I-scuPA complexed with equimolar concentrations of suPAR. To follow the concentration of scuPA in the circulation, the mice were injected intravenously with a single dose of 0.1 mg/kg 125I-scuPA or125I-scuPA/suPAR. At 5-, 10-, 15-, and 20-minute intervals, 100 μL blood was withdrawn by retro-orbital puncture into a heparinized microcapillary tube and counted for radioactivity. In other experiments, blood was withdrawn for counting at specified times (15, 30, and 45 minutes) during and at the completion of the 1-hour infusion with 125I-scuPA or 125I-scuPA/suPAR.

Results

Characterization of the pulmonary microembolus model

The purpose of this study was to investigate the involvement of urokinase and the urokinase receptor in intravascular fibrinolysis in vivo. To do so, our first goal was to develop a sensitive and reproducible murine model to analyze endogenous fibrinolytic activity. We reasoned that in previous studies, clot size, vascular location, and vascular injury may have contributed to limiting susceptibility of clots to lysis by uPA. To assess the contribution of these variables, we prepared relatively homogenous preparations of radio-labeled microparticles by adding thrombin to human plasma that had been supplemented with 125I-fibrinogen. The clots were then homogenized, and the larger particles were removed by sedimentation to obtain a homogenous suspension of fibrin microparticles.

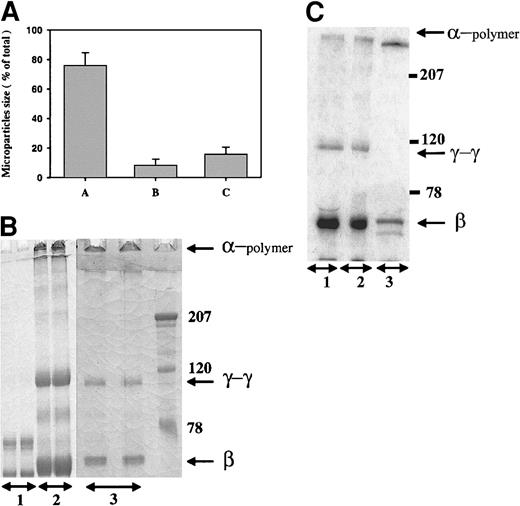

The size distribution of the microparticle preparation is shown in Figure 1A. Approximately 80% of the particles ranged in diameter from 1.5-3.25 μm. The fibrin within these microparticles was extensively cross-linked, as judged by the amount of the α-chain polymer and γ-γ dimers on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel under reduced conditions (Figure 1B). The migration of microparticles made from plasma was identical to that seen with microparticles made from purified fibrinogen (not shown) and was unchanged after homogenization and sedimentation of the parent clot (Figure 1B, compare lanes 2 and 3). Autoradiograms of clots prepared from plasma in the presence of 125I-fibrinogen showed the same pattern of cross-linking (Figure 1C), indicating that the radio-labeled fibrin had been incorporated into the microparticles and could therefore be used to follow clot lysis in subsequent experiments.

Characterization of fibrin microparticles.

(A) Size distribution of fibrin microparticles. Microparticles were prepared from thrombin-cleaved plasma, homogenized, and sedimented as described in “Materials and methods.” The size distribution of the suspended microparticles was analyzed using a ZM Coulter counter; the sizes were 1.5-3.25 μm, 3.25-4.05 μm, and >4.05 μm in columns A, B, and C, respectively. (B) Fibrin cross-linking of microparticles. Fibrinogen (lane 1), parent plasma clots (lane 2), and fibrin microparticles derived by homogenization and sedimentation (lane 3) were solubilized in urea and analyzed under reduced conditions on 10% SDS-PAGE. The gels were stained with Coomassie blue dye. The migration of the α-chain polymers, γ-γ dimers, and β chains is shown. The molecular weight markers are shown to the right. (C) Autoradiogram of 125I-fibrin incorporated into plasma clots. 125I-fibrinogen was added to plasma supplemented with unlabeled fibrinogen and clotted with thrombin, and the microparticles were prepared. The parent clot and the final microparticles were analyzed as in panel B, followed by autoradiography; the microparticles are depicted in lane 1; parent clot, lane 2; fibrinogen control, lane 3.

Characterization of fibrin microparticles.

(A) Size distribution of fibrin microparticles. Microparticles were prepared from thrombin-cleaved plasma, homogenized, and sedimented as described in “Materials and methods.” The size distribution of the suspended microparticles was analyzed using a ZM Coulter counter; the sizes were 1.5-3.25 μm, 3.25-4.05 μm, and >4.05 μm in columns A, B, and C, respectively. (B) Fibrin cross-linking of microparticles. Fibrinogen (lane 1), parent plasma clots (lane 2), and fibrin microparticles derived by homogenization and sedimentation (lane 3) were solubilized in urea and analyzed under reduced conditions on 10% SDS-PAGE. The gels were stained with Coomassie blue dye. The migration of the α-chain polymers, γ-γ dimers, and β chains is shown. The molecular weight markers are shown to the right. (C) Autoradiogram of 125I-fibrin incorporated into plasma clots. 125I-fibrinogen was added to plasma supplemented with unlabeled fibrinogen and clotted with thrombin, and the microparticles were prepared. The parent clot and the final microparticles were analyzed as in panel B, followed by autoradiography; the microparticles are depicted in lane 1; parent clot, lane 2; fibrinogen control, lane 3.

Trace-labeled fibrin microparticles were then injected into the tail veins of WT mice to study their organ distribution and effect on pulmonary function. Approximately 40% of the injected125I-labeled fibrin microparticles, but less than 3% of radio-labeled fibrinogen, were recovered from the lungs of the mice 10 minutes after intravenous injection (Figure2A). The injected microparticles were distributed homogeneously throughout the lobes of the lung, measured both as radioactivity per gram of tissue (not shown) and as judged by autoradiography (Figure 2B). The fibrin clots became lodged in pulmonary capillaries (Figure 3), as none of the occluded vessels were surrounded by smooth muscle cells. The affected vessels ranged in size from 5-32 μm, suggesting that in vivo aggregation of the microemboli had occurred in some of them. Some fibrin clots were found to contain a variable number of erythrocytes and other circulating hematopoetic cells. Mice infused with 8-fold more microparticles than were used in subsequent experiments showed no alteration in the wet:dry ratio or total myeloperoxidase activity in the lungs at 6 hours compared with mice injected with PBS alone (Table1). Thus, microembolization was not accompanied by a significant increase in vascular permeability or leukocyte emigration.

Distribution of 125I-microparticles in WT mice.

(A) 125I-microparticles (▪) or125I-fibrinogen (░) were injected into WT mice via the tail vein. Blood was drawn 10 minutes later, and the major organs were harvested, washed, and counted for radioactivity. The mean plus or minus SD of 3 experiments, each performed in 3 mice, is shown. Data are expressed as the percentage of injected dose per organ. (B) The lungs were removed from WT mice 10 minutes and 1 hour after injection of125I-microparticles and were analyzed by autoradiography.

Distribution of 125I-microparticles in WT mice.

(A) 125I-microparticles (▪) or125I-fibrinogen (░) were injected into WT mice via the tail vein. Blood was drawn 10 minutes later, and the major organs were harvested, washed, and counted for radioactivity. The mean plus or minus SD of 3 experiments, each performed in 3 mice, is shown. Data are expressed as the percentage of injected dose per organ. (B) The lungs were removed from WT mice 10 minutes and 1 hour after injection of125I-microparticles and were analyzed by autoradiography.

Immunohistochemical analysis of pulmonary microemboli.

WT mice were injected with the standard preparation of unlabeled microparticles. The lungs were harvested 10 minutes later, washed, fixed, and incubated with (A-C) a murine antihuman fibrin-specific antibody or (D) a nonimmune IgG1 control and enzyme-conjugated secondary antibody (original magnifications × 200).

Immunohistochemical analysis of pulmonary microemboli.

WT mice were injected with the standard preparation of unlabeled microparticles. The lungs were harvested 10 minutes later, washed, fixed, and incubated with (A-C) a murine antihuman fibrin-specific antibody or (D) a nonimmune IgG1 control and enzyme-conjugated secondary antibody (original magnifications × 200).

Mice infused with 8-fold more microparticles showed no alteration in the wet:dry ratio or total myeloperoxidase activity in the lungs at 6 hours compared with mice injected with PBS alone

| . | Wet:Dry . | Myeloperoxidase . |

|---|---|---|

| Microparticles | 4.46 ± 0.26 | 0.65 ± 0.15 |

| PBS | 4.51 ± 0.12 | 0.59 ± 0.10 |

| . | Wet:Dry . | Myeloperoxidase . |

|---|---|---|

| Microparticles | 4.46 ± 0.26 | 0.65 ± 0.15 |

| PBS | 4.51 ± 0.12 | 0.59 ± 0.10 |

WT and uPA−/− mice were injected with either an 8-fold concentrated suspension of unlabeled fibrin microparticles (relative to 125I-microparticles used in other experiments) or PBS. Six hours later, the animals were sacrificed, and the lungs were isolated and washed. The wet:dry ratio and the myeloperoxidase activity were measured as described in “Materials and methods.” The results shown represent the mean plus or minus SEM of 6 mice injected with fibrin microparticles and 4 mice injected with PBS.

Resolution of pulmonary microemboli in PA-deficient mice

We next examined the clearance of radio-labeled fibrin microparticles from the lungs of WT mice. The animals were killed at various times after intravenous injection, and the radioactivity remaining in the lungs was measured. The data in Figure4A shows the time-dependence of spontaneous clot lysis in WT mice. Within 1 hour, 70% of the radioactivity was cleared from the lungs, and near total resolution was evident by 3 hours. The rapid resolution may reflect activation of human plasminogen incorporated into the microemboli during their preparation.

Clearance of 125I-microemboli from the lungs of WT and PA-deficient mice.

(A) 125I-microparticles were injected via the tail vein into WT mice (●); uPA−/− mice (■); or tPA−/− mice (▴). At the indicated times, the lungs were harvested, washed, and counted for radioactivity. The data are expressed relative to the radioactivity in the lungs 10 minutes after injection. This latter value was the same in all 3 groups. The data represent the mean plus or minus SEM of 3 independent experiments each involving 4-5 mice per time point. Data from the uPA−/−and tPA−/− mice are essentially superimposable when averaged over this many animals and experiments. At some time points, the error bars for WT mice are not apparent because the deviation was too small to appreciate. The triple asterisk refers to time points where the difference between the outcome in the gene deletion and WT mice reaches a statistical significance with P < .001. The insert shows residual radioactivity in tPA−/−, uPA−/−, and WT mice at 30 minutes compared to 10-minute controls (n = 3). (B) Autoradiography of lungs from a WT or uPA−/− mouse 3 hours after injection of125I-microparticles.

Clearance of 125I-microemboli from the lungs of WT and PA-deficient mice.

(A) 125I-microparticles were injected via the tail vein into WT mice (●); uPA−/− mice (■); or tPA−/− mice (▴). At the indicated times, the lungs were harvested, washed, and counted for radioactivity. The data are expressed relative to the radioactivity in the lungs 10 minutes after injection. This latter value was the same in all 3 groups. The data represent the mean plus or minus SEM of 3 independent experiments each involving 4-5 mice per time point. Data from the uPA−/−and tPA−/− mice are essentially superimposable when averaged over this many animals and experiments. At some time points, the error bars for WT mice are not apparent because the deviation was too small to appreciate. The triple asterisk refers to time points where the difference between the outcome in the gene deletion and WT mice reaches a statistical significance with P < .001. The insert shows residual radioactivity in tPA−/−, uPA−/−, and WT mice at 30 minutes compared to 10-minute controls (n = 3). (B) Autoradiography of lungs from a WT or uPA−/− mouse 3 hours after injection of125I-microparticles.

We then compared the rate of clot lysis in tPA−/−, uPA−/−, and uPAR−/− mice with that seen in littermate controls. Spontaneous resolution of pulmonary microemboli in tPA−/− and uPA−/− mice (both on a C57/black-6 background) was delayed significantly compared with WT littermate controls (Figure 4A). Identical results were seen in uPA−/− mice on a mixed genetic background (data not shown). The delay was evident at 0.5, 1, and 3 hours and persisted at 5 hours, the last time point studied. These results were confirmed by autoradiography of the lung tissue 3 hours after the injection of labeled microparticles (Figure 4B). Only at the earliest time point examined (0.5 hours) was there a significant difference between the amount of residual clot in tPA−/− mice (102.2% ± 1.6% mean plus or minus SEM; n = 3) compared with uPA−/− mice (82.4% ± 3.9%; P < .001) (Figure 4A, insert). There were no visible differences in clot lysis between uPAR−/− and control mice at any time point (not shown). These data indicate that uPA−/− mice have a defect in spontaneous lysis of pulmonary microemboli that is comparable in the severity to tPA−/− mice.

scuPA- and scuPA/suPAR-mediated clot lysis

We then asked 2 interrelated questions: First, would scuPA restore clot lysis in uPA−/− mice to normal, excluding an indirect effect of interrupting the gene (eg, on tissue remodeling or vascular responsiveness to a thrombotic stress)? Second, would suPAR promote the PA activity of scuPA in vivo as we previously observed in human plasma in vitro19? We chose uPA−/− mice to test our hypothesis that suPAR would stimulate fibrinolysis because their rate of spontaneous clot lysis was slower.

To address these questions, uPA−/− mice were divided into 4 treatment groups that received a constant infusion of either PBS, scuPA, suPAR, or an equimolar concentration of a scuPA/suPAR complex administered through a cannula placed in the jugular vein. Five minutes later, 125I-labeled microparticles were injected via the tail vein. The infusions were continued for an additional 60 minutes, at which time residual radioactivity in the lungs was measured. As shown in Figure5, infusion of 0.25 mg/kg/h scuPA increased clot lysis in uPA−/− mice from 50.1% ± 7.0% (mean plus or minus SEM) to 76.7% ± 9.2% of that seen in WT controls (P = .036). Clot lysis was normalized when 0.50 mg/kg/h scuPA was infused.

Fibrinolytic activity of scuPA and scuPA/suPAR in uPA

−/−mice in vivo. We infused uPA−/− mice with scuPA (■) or scuPA/suPAR (▩) (0.25 or 0.5 mg scuPA/kg/h) via the jugular vein. Five minutes later,125I-fibrin microparticles were injected, and the infusion of scuPA or scuPA/suPAR was continued for another hour. The lungs were harvested, washed, and counted for radioactivity. The data are expressed relative to fibrinolytic activity in WT mice infused with PBS in the same manner for 1 hour, as defined in “Materials and methods.” The means plus or minus SEM of 2 experiments, each involving data from 3-5 mice in each experimental group, are shown.

Fibrinolytic activity of scuPA and scuPA/suPAR in uPA

−/−mice in vivo. We infused uPA−/− mice with scuPA (■) or scuPA/suPAR (▩) (0.25 or 0.5 mg scuPA/kg/h) via the jugular vein. Five minutes later,125I-fibrin microparticles were injected, and the infusion of scuPA or scuPA/suPAR was continued for another hour. The lungs were harvested, washed, and counted for radioactivity. The data are expressed relative to fibrinolytic activity in WT mice infused with PBS in the same manner for 1 hour, as defined in “Materials and methods.” The means plus or minus SEM of 2 experiments, each involving data from 3-5 mice in each experimental group, are shown.

The extent of clot lysis was greater when uPA−/− mice were infused with equal concentrations of scuPA complexed to suPAR. As shown in Figure 5, infusion of 0.25 mg/kg/h scuPA/suPAR increased lysis from 50.1% ± 7.0% to 150% ± 8.0% of WT control compared with 76.7% ± 9.2% when scuPA alone was infused, a 4-fold increase in the extent of uPA-induced lysis (P < .001). Clot lysis in mice infused with suPAR alone was the same as that seen with PBS (not shown).

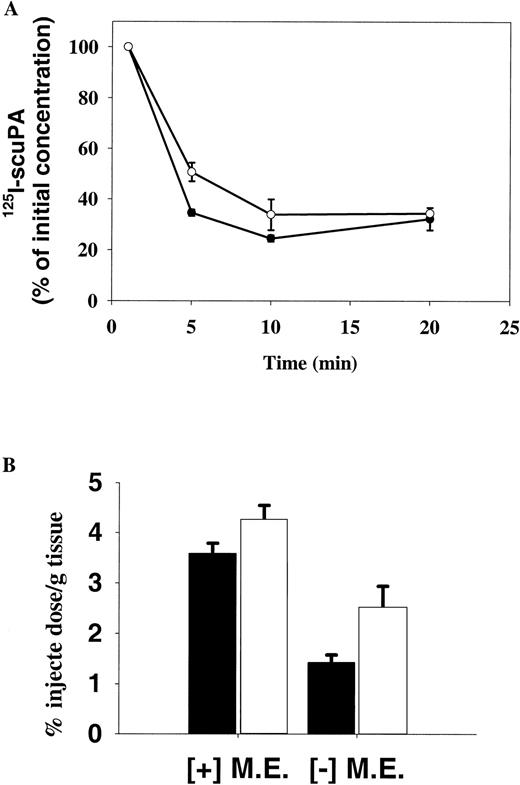

The effect of suPAR on the pharmacokinetic and fibrinolytic parameters of scuPA

We and others have reported that uPAR promotes adhesion of scuPA to vitronectin.20-23 Therefore, we asked whether suPAR enhanced fibrinolysis because more scuPA was present in the circulation during the 1-hour infusion when complexed with suPAR or because the receptor promoted the accumulation of scuPA within the microemboli. The results shown in Figure6A indicate that suPAR accelerated the disappearance of scuPA from the blood when given intravenously as a single dose. Thus, suPAR did not increase the plasma concentration of scuPA by retarding its clearance from the plasma. There were also no statistically significant differences in the steady-state whole blood concentrations of 125I-scuPA given as a constant infusion at 15, 30, 45, and 60 minutes in the presence or absence of suPAR (not shown). More 125I-scuPA accumulated in the lungs of mice bearing microemboli compared to clot-free mice, as expected (Figure6B). The uptake of 125I-scuPA was enhanced by suPAR in pulmonary tissue in mice free of emboli, but it did not cause a statistically significant increase (P = .13) in mice bearing microemboli (Figure 6B). Taken together, these data indicate that suPAR does not promote pulmonary fibrinolysis either by prolonging the half-life of scuPA in the circulation or by causing it to accumulate preferentially within the clots.

Distribution of scuPA and scuPA/suPAR in vivo.

(A) Clearance of 125I-scuPA from mouse blood. uPA−/− mice were injected with 0.1 mg/kg125I-scuPA (○) or 125I-scuPA/suPAR (●), and the radioactivity in the blood of each mouse was measured at the indicated times. The results show the mean plus or minus SD of 3 mice studied serially. (B) Accumulation of 125I-scuPA in pulmonary tissue. We infused uPA−/− mice with 0.125 mg/kg/h 125I-scuPA (■) or 125I-scuPA /suPAR (□) for 1 hour. The isolated lungs were washed, and the radioactivity was measured. The results shown represent the mean plus or minus SEM of 2 experiments, each involving 3 mice. M.E. indicates microemboli.

Distribution of scuPA and scuPA/suPAR in vivo.

(A) Clearance of 125I-scuPA from mouse blood. uPA−/− mice were injected with 0.1 mg/kg125I-scuPA (○) or 125I-scuPA/suPAR (●), and the radioactivity in the blood of each mouse was measured at the indicated times. The results show the mean plus or minus SD of 3 mice studied serially. (B) Accumulation of 125I-scuPA in pulmonary tissue. We infused uPA−/− mice with 0.125 mg/kg/h 125I-scuPA (■) or 125I-scuPA /suPAR (□) for 1 hour. The isolated lungs were washed, and the radioactivity was measured. The results shown represent the mean plus or minus SEM of 2 experiments, each involving 3 mice. M.E. indicates microemboli.

Therefore, we asked whether the increased lysis of125I-microemboli in uPA−/− mice by scuPA/suPAR compared to scuPA alone was attributable to an increase in its specific fibrinolytic activity. To address this possibility, we asked whether human suPAR would promote human scuPA-mediated lysis of human clots placed in murine plasma in vitro, analogous to the clot environment in the in vivo model. The lysis of human clots by 25 nmol/L scuPA was promoted by 25 nmol/L suPAR to the same extent in human and rat plasma (Figure 7); a somewhat greater stimulation of uPA activity was observed in mouse plasma (not shown). Identical stimulation was seen using clots made from rat plasma alone (not shown). These data make it likely that the accelerated lysis of microemboli in the uPA−/− mice by scuPA/suPAR is due to the increased fibrinolytic activity of the complex compared with scuPA alone.

Fibrinolytic activity of scuPA/suPAR complexes in rat plasma in vitro.

Human plasma clots, trace-labeled with 125I-fibrin, were incubated in human or rat plasma supplemented with 25 nmol/L scuPA (human plasma indicated by ▪, rat plasma indicated by ■) or 25 nmol/L scuPA/suPAR (human plasma indicated by ♦, rat plasma indicated by ⋄) at 37°C. The radioactive fibrin degradation products released into the supernatant were measured at the indicated times. At each time point, fibrinolysis was calculated by subtracting the endogenous release of radioactivity and was expressed as the percent of total lysis. The data shown represent the mean plus or minus SD of triplicate determinations from 2 experiments.

Fibrinolytic activity of scuPA/suPAR complexes in rat plasma in vitro.

Human plasma clots, trace-labeled with 125I-fibrin, were incubated in human or rat plasma supplemented with 25 nmol/L scuPA (human plasma indicated by ▪, rat plasma indicated by ■) or 25 nmol/L scuPA/suPAR (human plasma indicated by ♦, rat plasma indicated by ⋄) at 37°C. The radioactive fibrin degradation products released into the supernatant were measured at the indicated times. At each time point, fibrinolysis was calculated by subtracting the endogenous release of radioactivity and was expressed as the percent of total lysis. The data shown represent the mean plus or minus SD of triplicate determinations from 2 experiments.

Discussion

We developed a model to study fibrinolysis in the microvasculature of small laboratory animals using125I-fibrin microparticles that embolize to the lung after tail vein injection. This method enabled us to measure the contribution of uPA, tPA, and uPAR to endogenous fibrinolysis in the pulmonary microvasculature. The results of this study demonstrate that mice lacking uPA have an impaired capacity to lyse pulmonary microemboli. The defect in uPA-deficient mice is comparable in severity to that seen in mice lacking tPA and can be rescued completely by providing urokinase exogenously.

Our finding that endogenous urokinase contributes to fibrinolysis differs from a previous study in which spontaneous lysis of occlusive thrombi was normal in uPA−/− mice but impaired in tPA−/− mice.2 Our finding also differs from a more recent study in which uPA−/− and WT mice subjected to vascular injury showed no difference in clot formation or spontaneous lysis.4 These differences in outcome may be attributable, in part, to the greater sensitivity of the microembolus model employed in the present study, as demonstrated by the more rapid rate with which microemboli were lysed in WT mice compared with the reported rate of resolution of occlusive thrombi.2However, a difference in the sensitivity of the assay systems due to the incorporation of human plasminogen into the fibrin microparticles24 or their increased surface:volume ratio is unlikely to be the sole explanation for the observed differences. If this were the case, the difference between the behavior of the tPA−/− and uPA−/− mice would have been expected to be preserved.

Three other explanations for the involvement of urokinase in the resolution of microemboli as compared with large occlusive thrombi are possible. The first relates to potential structural differences between the 2 types of clots. Microemboli have a higher surface:volume ratio than do large occlusive emboli. This may increase the relative interface between the clot and the endothelium or leukocytes, which may facilitate the contribution of cell-bound uPA. Secretion of uPA by the occluded vasculature or binding of urokinase by vascular cells in proximity to the clot may have a greater opportunity to interact with the surface of the microemboli compared to larger clots. In turn, this makes the larger clots more dependent on fibrin-mediated activation of plasma tPA.

Second, large occlusive clots may induce mechanical trauma or tissue ischemia. Hypoxia down-regulates uPA synthesis while promoting the synthesis of PAI-1.5 Emboli that lodge primarily in the pulmonary microvasculature, which receives its oxygen supply primarily through ventilation rather than perfusion, resolve rapidly in contrast to occlusive thrombi affecting blood supply to other organs. Thus, inhibition of uPA synthesis by vascular occlusion, even in WT mice, might obscure evident differences in the behavior of uPA−/− mice.

A third possibility lies in the relatively unexplored issue of vascular heterogeneity.25 Synthesis of tPA by vascular endothelial cells, for example, is regionally restricted.26 Studies that did not show a phenotype in uPA−/− mice involved the resolution of occlusive thrombi that lodged in large pulmonary vessels.2 Pulmonary microvascular cells produce abundant uPA and less tPA in culture compared with other sources of endothelium.27 Pulmonary macrovascular and microvascular endothelial cells may also differ in their constitutive expression of uPA or their capacity to synthesize uPA in response to mechanical or ischemic damage induced by fibrin clots. The possibility that uPA plays a more important role in certain organs or types of vascular beds is the subject of a current study. Irrespective of the mechanism, to our knowledge this study provides the first direct evidence that urokinase per se plays a rate-limiting step in endogenous intravascular fibrinolysis.

The difference in clot lysis between tPA−/− and uPA−/− mice at 30 minutes is consistent with the proposed concept that the 2 PAs are complementary, sequential, and synergistic in their fibrinolytic action in vitro.28,29 It has been proposed that tPA binds to the clot surface first because of its high affinity, initiating plasminogen activation and plasmin formation. This in turn exposes additional binding sites for plasminogen, which potentiates activation by scuPA and exposes fragment E-2, which is unavailable in intact fibrin.28 29 To our knowledge, this is the first in vivo data in support of this concept. Alternatively, fibrin may be exposed immediately to circulating tPA in uPA−/− mice, but the induction of uPA by fibrin-mediated damage may be somewhat delayed in tPA−/− mice.

The absence of any impairment of fibrinolysis in uPAR−/−mice may indicate that the level of uPAR expression in WT mice is insufficient before or after exposure to fibrin to accelerate uPA-mediated fibrinolysis. In turn, this suggests either that uPA acts within the fibrin clot itself or that clot lysis is accelerated on cell surfaces through uPAR-independent mechanisms.30 31

Another possibility is that the uPA-uPAR complex is not active in vivo. We and others8-10 have reported that the binding of scuPA to its receptor promotes its enzymatic activity and protects the enzyme against inactivation by PA inhibitors in vitro. Stimulation of scuPA activity was demonstrable with certain chromogenic substrates32 as well as when human plasma clots were used as the substrate.20 The suPAR-stimulated scuPA-mediated fibrinolysis in murine plasma in vitro and in vivo (Figure 5) excludes the possibility that the absence of a phenotype in the uPAR−/− mice is attributable to an inability to form enzymatically active complexes in vivo. This outcome is consistent with the results of other recent studies.14 Rather, it is more likely that uPAR expression is limited on vascular cells in healthy mice. Although hypoxia may up-regulate uPAR expression,33inhibition of uPA expression under the same conditions6 may preclude sufficient scuPA/uPAR complexes from being formed to promote intravascular clot lysis.

It has previously been reported that suPAR inhibits and promotes fibrinolysis in vitro depending on the experimental conditions.18 34 This study demonstrates that uPAR, in this case in the form of a soluble receptor, stimulates fibrinolytic activity in vivo. In this study, suPAR did not increase fibrinolysis by scuPA either by prolonging its time in the circulation or by increasing its local concentration in the lung. Indeed, suPAR accelerated initial uptake of scuPA from the circulation and did increase the accumulation of scuPA within the lungs of mice bearing microemboli.

Taken together, the data suggest that uPA mediates endogenous fibrinolysis in the pulmonary microvasculature and that suPAR promotes fibrinolysis by stimulating the specific activity of urokinase. However, the ability of suPAR to promote clot lysis by protecting uPA from inactivation by PAI-135 and other serpins10 or through other mechanisms will require additional study.

Acknowledgment

We wish to thank Christopher Yaen for excellent technical assistance on this project.

Supported in part by grants HL60169 and HL47839 (D.C. and A.H.) from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, and research grant RG-062 (V.R.M.) from the American Lung Association. J.-C.M. is supported by a North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) fellowship, Washington, DC.

K.B. and J.-C.M. contributed equally to this work.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Abd Al-Roof Higazi, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, 513A Stellar-Chance, 422 Curie Blvd, Philadelphia, PA 19104; e-mail: higazi@mail.med.upenn.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal