Although cyclin-dependent kinase 5 (Cdk5) is widely expressed in human tissues, its activator p35Nck5a is generally considered to be neuron specific. In addition to neuronal cells, active Cdk5 complexes have been reported in developing tissues, such as the embryonic muscle and ocular lens, and in human leukemia HL60 cells induced to differentiate by an exposure to 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3; however, its activator in these cells has not been demonstrated. The results of this study indicate that p35Nck5a is associated with Cdk5 in monocytic differentiation of hematopoietic cells. Specifically, p35Nck5a is expressed in normal human monocytes and in leukemic cells induced to differentiate toward the monocytic lineage, but not in lymphocytes or cells induced to granulocytic differentiation by retinoic acid. It is present in a complex with Cdk5 that has protein kinase activity, and when ectopically expressed together with Cdk5 in undifferentiated HL60 cells, it induces the expression of CD14 and “nonspecific” esterase, markers of monocytic phenotype. These observations not only indicate a functional relationship between Cdk5 and p35Nck5a, but also support a role for this complex in monocytic differentiation.

Introduction

Cyclin-dependent kinase 5 (Cdk5) is a proline-directed serine/threonine kinase that has sequence homology to cyclin-activated kinases, which regulate cell cycle progression.1,2 However, the role of Cdk5 in the control of the cell cycle is not clear. Currently, the best known function of Cdk5 is an involvement in the development of the nervous system, where its demonstrated roles include neurite outgrowth, neuronal migration, and axon patterning.3-5 It has been found in different studies that the extent of Cdk5 kinase activity parallels the degree of neuronal differentiation.6-8

Although Cdk5 has been reported to be associated with some cyclins, such as cyclin D1, cyclin D2, cyclin D3, and cyclin E,9-14there is no evidence that its kinase activity is dependent on binding to cyclins. Instead, brain Cdk5 has been shown to be activated by a 35-kd protein distantly related to cyclins, known as the neuronal Cdk5 activator (Nck5a) or p35, which is autophosphorylated in the complex with Cdk5.15 Unlike Cdk5, which is expressed in numerous tissues, in the adult animal p35Nck5a has so far been demonstrated to be present only in neuronal cells.15-18

We have recently reported14,19 that the expression of Cdk5 increases when human promyeloblastic leukemia cells HL6020are induced to differentiate toward the mature monocytic phenotype by an exposure to 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3(1,25D3). Cdk5-associated kinase activity also increases, but although cyclin D1 levels are higher in the differentiating cells and cyclin D1 is found in association with Cdk5, the presence of cyclin D1 in this complex does not correlate with Cdk5 kinase activity.14 The presence of other cyclins was not detected in this complex.14 The possibility that the neuronal activator of Cdk5, p35Nck5a, is expressed and activates Cdk5 in monocytic cells was therefore investigated here.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and blood cell preparation

The cells used, HL60-G,21 CEM, and Daudi, were grown in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated bovine calf serum and 1% l-glutamine (all from Mediatech, Washington, DC) at 37°C in an environment of 5% CO2. Fresh whole human blood (150 mL) was obtained from normal donors with their written consent, and was diluted 1:1 by volume with 1 × phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The diluted blood was then layered over Ficoll Hypaque (Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ) at 0.5 volume of Ficoll to 1 volume diluted blood and centrifuged at 500gfor 15 minutes. The buffy coat containing the mononuclear cells was then aspirated from the tube and washed twice in PBS. The red cell pellet remaining at the bottom of the Ficoll tube was isolated by aspiration of the plasma, buffy coat, and Ficoll. This pellet, containing the red cells and granulocytes, was diluted in PBS and the red cells lysed in the hypotonic buffer. The tube was then centrifuged at 800g for 15 minutes, the supernatant was discarded, and the granulocytes in the pellet washed twice in 1 × PBS. The monocytic and lymphocytic cells were separated by placing the nucleated cells from the buffy coat in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% fetal calf serum in a tissue culture flask for 3 hours at 37°C. The adherent cells constituted the monocytic fraction, and the suspended cells the lymphocytic fraction, as confirmed by microscopic examination of cells stained with Giemsa-Wright stain.

Cell and mouse brain extract preparation, immunoblot analysis, immunoprecipitation, and kinase reactions

These procedures were described,14,19 except that immunoprecipitations were performed on 200 μg of each cell extract using 3 μg Cdk5 antibody (Ab), or 2 μg p35Nck5a Ab. For depletion assays, the immunoprecipitates obtained with anticyclin D1- or anti-p35Nck5a–coated beads were centrifuged and discarded, and the supernatants were immunoprecipitated again with Cdk5 Ab. For a complementary experiment, the immunoprecipitates obtained with Cdk5 Ab-coated beads were centrifuged and washed 3 times with cold protein lysis buffer. The beads were resuspended with 200 μL protein lysis buffer, incubated with p35Nck5a Ab or cyclin D1 Ab for another 1 hour at 4°C, and the kinase reaction assay was performed using histone H1 or retinoblastoma protein (pRb) 46-kd fusion protein as substrate. Autoradiograms of histone H1 or pRb resolved on 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) gel were scanned by an image quantitator (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA). For “autophosphorylation” assays (phosphorylation of components within Cdk5 complexes), the immunoprecipitated complexes were incubated under kinase reaction conditions, except that no histone H1 or pRb substrate was added. To obtain brain extracts, fresh NZB mouse brain was washed 3 times in cold 1 × PBS containing 1% bovine serum albumin and frozen in liquid nitrogen for 5 minutes. The tissue was crushed with a hammer, then rinsed with 1 × PBS buffer to obtain a single cell suspension. The cells were washed 3 more times with this buffer and suspended in the protein lysis buffer, described previously.14 19

Abs and kinase substrates

p35Nck5a (Ab-1, used for immunoprecipitation [IP]) was from Abvision, Fremont, CA. p35 (C-19), Cdk5 (DC-17, used for immunoblotting [IB]), Cdk5 (C-8, used for IP), hemagglutinin (HA)-probe (F-7), cyclin D1 (C-20), pRb 46-kd fusion protein (no. 769), the p35 blocking peptide (C19), and the Cdk5 blocking peptide (C-8) were all from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA. Phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated CD14-PE (MY4-RD1) and CD15 were obtained from Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA, and calreticulin (Cal), pA3-900, from ABR (Golden, CO), and was used as a loading control for Western blot analysis. The differentiation inducers used were described previously.14 19 Histone H1 (cat no. 13221-015) was obtained from Gibco (Rockville, MD).

Expression plasmids and transient transfection

The plasmids pCMV-p35, pCMV-Cdk5, and pCMV-Cdk5HA were kind gifts of Dr Li-Huei Tsai, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Harvard Medical School. pEGFPN1 was a kind gift of Dr Hua Zhu, UMDNJ–New Jersey Medical School. pEGFPN1-Cdk5 was constructed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of the Cdk5 fragment from pCMV-Cdk5 plasmid, followed by the insertion of this fragment into theSacI/SalI site within the polylinker of the mammalian expression vector pEGFPN1, which is under the control of the CMV promoter. The primers for PCR were as follows: 5′GCGCGGATCCGAGCTCATGCAGGAATACGAGAAACT-3′ and 5′-GCGCGTCGACGGACAGAAGTCGGAGAGT-3′. Transient transfections were performed as described,19 except that 10 μg pCMV-Cdk5-HA (or empty vector), 5 μg pEGFPN1-Cdk5, 2.5 μg pEGFPN1-Cdk5 together with 2.5 μg pCMV-p35, or 2.5 μg pEGFPN1 vector together with 2.5 μg pCMV-p35 were transfected by electroporation as indicated in the figure legends. The cells transfected with pCMV-Cdk5-HA were divided into 2 groups, one of which was treated with 1,25D3as indicated in the legend to Figure 2. Cells transfected with pEGFPN1-Cdk5 and/or p35 expression vectors were grown in the culture for 48 hours, spun down, and stained for CD14 as described.14 The stained cells were examined for the expression of Cdk5 (green color) and the differentiation marker CD14 (red color) under fluorescent microscope using fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) and rhodamine filters. In separate experiments the cells were also examined for the presence of “nonspecific,” monocyte-associated, esterase (NSE) by the cytochemical procedure described previously.19 These, and all other experiments presented here, were repeated for a total of 4 times with similar results, except as noted in the individual experiments.

Results

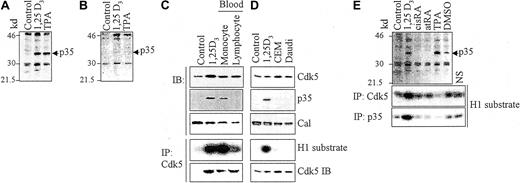

Expression of p35Nck5a in monocytic but not granulocytic or lymphocytic human cells

HL60 cells induced toward monocytic/macrophage differentiation by 1,25D3 or by 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA), an extensively documented system for vitro differentiation,14,19,21 were found to express a 35-kd protein immunoreactive for Nck5a (Figure1A). The specificity of the Ab was shown by the loss of the 35-kd band when the immunoblot was blocked with the immunizing peptide (Figure 1B). When components of blood from healthy volunteers were examined for the presence of Cdk5, p35Nck5a, or for the Cdk5-associated kinase activity, p35Nck5a and the kinase activity were found only in the monocytic fraction (Figure 1C). Normal lymphocytes and lymphocytic cells lines CEM (T-cell line) and Daudi (B-cell line) expressed the Cdk5 protein, but did not express p35Nck5a, and there was no Cdk5-associated kinase activity (Figure 1C,D). Circulating granulocytes from healthy donors also had no detectable p35Nck5a protein (data not shown). When HL60 cells were induced to differentiate toward the granulocytic phenotype by an exposure to all-transretinoic acid (atRA) or 9-cis retinoic acid (cisRA),22 p35Nck5a was not detected (Figure 1E). Similarly, only a trace of p35Nck5a protein and Cdk5a-associated kinase activity were noted in HL60 cells exposed to dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) (Figure 1E), an agent that induces granulocytic differentiation on a morphologic basis.23 This demonstrates that in neoplastic leukocytes p35Nck5a is specifically expressed in cells with features of the monocytic phenotype, that it is expressed in normal monocytes but not in lymphocytes or granulocytes, and that its presence correlates with Cdk5-associated kinase activity.

Demonstration of the presence of p35Nck5a in cells with monocytic phenotype.

(A) Presence of a 35-kd protein immunoreactive with an antibody to Nck5a in HL60 cells induced to monocyte phenotype by exposure to 10−7M 1,25D3, or to macrophage phenotype by 10−8M TPA for 96 hours. The migration of size markers is indicated on the left side of the panel in kilodaltons. (B) An immunoblot (IB) run in parallel to the one shown in panel A, but probed with antibody that was preblocked with the immunizing peptide. Note the absence of the 35-kd band. (C) The 3 upper panels show IBs for the indicated proteins (Cal indicates calreticulin, a loading control) in lysates of monocytes and lymphocytes from blood of healthy volunteers, and from undifferentiated (negative control) and differentiated HL60 cells (10−7M 1,25D3 for 96 hours) as a positive control. The fourth panel shows kinase activity associated with Cdk5 immunoprecipitated (IP) from these lysates using histone H1 (H1) as the substrate and the bottom panel the Cdk5 protein content in these IPs demonstrated by immunoblotting. (D) Similar analysis of lymphocytic cell lines. (E) Absence of p35Nck5a in HL60 induced toward granulocytic phenotype by 96 hours of treatment with 10−6M 9-cis retinoic acid (cisRA) or all-trans retinoic acid (atRA). HL60 cells treated with monocyte/macrophage inducers show strong p35 bands, whereas cells treated with 1.25% DMSO for 96 hours show a faint 35-kd band. The bottom panels demonstrate Cdk5- and p35Nck5a-associated kinase activity showing a strong signal for 1,25D3-treated HL60 cells, a weak signal for DMSO-treated cells, and only background levels in untreated RA-treated or TPA-treated cells. The background level was determined by incubation of the extract with beads that were not coated with the antibody to either Cdk5 or p35Nck5a (marked NS, nonspecific). The data shown illustrate 4 similar experiments.

Demonstration of the presence of p35Nck5a in cells with monocytic phenotype.

(A) Presence of a 35-kd protein immunoreactive with an antibody to Nck5a in HL60 cells induced to monocyte phenotype by exposure to 10−7M 1,25D3, or to macrophage phenotype by 10−8M TPA for 96 hours. The migration of size markers is indicated on the left side of the panel in kilodaltons. (B) An immunoblot (IB) run in parallel to the one shown in panel A, but probed with antibody that was preblocked with the immunizing peptide. Note the absence of the 35-kd band. (C) The 3 upper panels show IBs for the indicated proteins (Cal indicates calreticulin, a loading control) in lysates of monocytes and lymphocytes from blood of healthy volunteers, and from undifferentiated (negative control) and differentiated HL60 cells (10−7M 1,25D3 for 96 hours) as a positive control. The fourth panel shows kinase activity associated with Cdk5 immunoprecipitated (IP) from these lysates using histone H1 (H1) as the substrate and the bottom panel the Cdk5 protein content in these IPs demonstrated by immunoblotting. (D) Similar analysis of lymphocytic cell lines. (E) Absence of p35Nck5a in HL60 induced toward granulocytic phenotype by 96 hours of treatment with 10−6M 9-cis retinoic acid (cisRA) or all-trans retinoic acid (atRA). HL60 cells treated with monocyte/macrophage inducers show strong p35 bands, whereas cells treated with 1.25% DMSO for 96 hours show a faint 35-kd band. The bottom panels demonstrate Cdk5- and p35Nck5a-associated kinase activity showing a strong signal for 1,25D3-treated HL60 cells, a weak signal for DMSO-treated cells, and only background levels in untreated RA-treated or TPA-treated cells. The background level was determined by incubation of the extract with beads that were not coated with the antibody to either Cdk5 or p35Nck5a (marked NS, nonspecific). The data shown illustrate 4 similar experiments.

p35Nck5a forms a complex with Cdk5, which has kinase activity

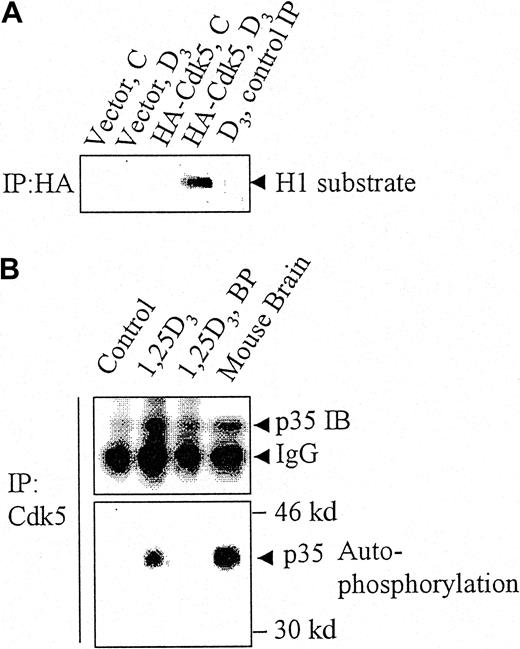

When HA-tagged Cdk5 was transfected into HL60 cells differentiated by an exposure to 1,25D3, and the exogenous Cdk5 complex immunoprecipitated with an HA Ab, this Cdk5 complex had an associated kinase activity (Figure 2A, lane 4). However, exogenous, HA-tagged Cdk5, which was immunoprecipitated from undifferentiated HL60 cells, had no kinase activity (Figure 2A, lane 3). This indicates that differentiated, but not undifferentiated HL60 cells, express an activator of Cdk5.

p35Nck5a associates with and activates Cdk5 in differentiating HL60 cells.

(A) HL60 cells were transfected with an empty pCMV vector (“Vector”) or with a vector expressing hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged Cdk5, and either left untreated (C) or exposed to 10−7M 1,25D3 (D3) for 48 hours. The cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with an HA antibody and the immunoprecipitate incubated with histone H1 (H1) substrate under kinase assay conditions. The panel shows an autoradiogram for 32P-labeled histone H1 and demonstrates that transfected (HA tagged) Cdk5 becomes activated as a kinase in differentiating (1,25D3-treated) but not in undifferentiated HL60 cells. The lane marked “control IP” represents a control where the beads used for immunoprecipitation were not coated with the antibody. (B) Lysates of untreated HL60 cells. HL60 cells treated with 10−7M 1,25D3 for 48 hours and fresh whole mouse brain cell extract were immunoprecipitated (IP) with antibody to Cdk5. The lysates were incubated with γ32P-ATP in kinase assay buffer without an exogenous substrate then subjected to gel electrophoresis. The upper panel shows the immunoreactive p35 protein demonstrated by immunoblotting (IB), the lower panel the phosphorylation of the p35 protein by autoradiography for 32P. Mouse brain was used as a positive control of the previously reported autophosphorylation of p35Nck5a by neural cells. BP indicates a control in which the immunoprecipitating Cdk5 antibody was blocked with the immunizing peptide. The data illustrate 4 similar experiments.

p35Nck5a associates with and activates Cdk5 in differentiating HL60 cells.

(A) HL60 cells were transfected with an empty pCMV vector (“Vector”) or with a vector expressing hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged Cdk5, and either left untreated (C) or exposed to 10−7M 1,25D3 (D3) for 48 hours. The cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with an HA antibody and the immunoprecipitate incubated with histone H1 (H1) substrate under kinase assay conditions. The panel shows an autoradiogram for 32P-labeled histone H1 and demonstrates that transfected (HA tagged) Cdk5 becomes activated as a kinase in differentiating (1,25D3-treated) but not in undifferentiated HL60 cells. The lane marked “control IP” represents a control where the beads used for immunoprecipitation were not coated with the antibody. (B) Lysates of untreated HL60 cells. HL60 cells treated with 10−7M 1,25D3 for 48 hours and fresh whole mouse brain cell extract were immunoprecipitated (IP) with antibody to Cdk5. The lysates were incubated with γ32P-ATP in kinase assay buffer without an exogenous substrate then subjected to gel electrophoresis. The upper panel shows the immunoreactive p35 protein demonstrated by immunoblotting (IB), the lower panel the phosphorylation of the p35 protein by autoradiography for 32P. Mouse brain was used as a positive control of the previously reported autophosphorylation of p35Nck5a by neural cells. BP indicates a control in which the immunoprecipitating Cdk5 antibody was blocked with the immunizing peptide. The data illustrate 4 similar experiments.

To test whether the activator is analogous to the previously extensively studied Nck5a from the murine brain,15-18 we immunoprecipitated Cdk5 from untreated HL60 cells, from HL60 cells that were differentiated with 1,25D3, and from a mouse brain. Figure 2B shows that Cdk5 brings down with it a 35-kd protein immunoreactive for Nck5a, and when incubated with adenosine triphosphate (ATP) this 35-kd protein is autophosphorylated in the complex in a manner analogous to the brain Nck5a protein, as described by Tsai and coworkers.15

Endogenous HL60 Cdk5 requires p35Nck5a, but not cyclin D1, for its kinase activity

Because the levels of both cyclin D1 and p35Nck5a protein increase as HL60 cells differentiate toward monocytes, we performed immunodepletion experiments to determine which of these activators is required for the kinase activity of Cdk5. Figure3, panels A and B, show that removal of immunoprecipitable cyclin D1 had only a modest, statistically insignificant (P > .05), effect on the subsequent assay of Cdk5-associated kinase activity using either histone H1 or pRb protein as the vitro substrate, whereas removal of p35Nck5a dramatically reduced the kinase activity (P < .01).

Immunodepletion of p35Nck5a reduces Cdk5-associated kinase activity.

(A) Cdk5-associated kinase activity on 2 in vitro substrates histone H1 (H1) and the retinoblastoma protein (pRb) is shown for lysates of undifferentiated HL60 cells (lanes 1, 3, and 5), and lysates of HL60 cells treated with 10−7M 1,25D3 for 96 hours (lanes 2, 4, 6, and 7). The first 2 lanes show Cdk5-associated kinase activity of the cell lysates, lanes 3 and 4 the Cdk5-associated kinase activity after immunodepletion of the lysate with an antibody to cyclin D1, and lanes 5 and 6 after immunodepletion of the lysate with an antibody to p35Nck5a. Lane 7 shows a nonspecific signal that was obtained by subjecting the lysates of HL60 cells differentiated with 1,25D3 to the immunoprecipitation procedure but omitting the Cdk5 antibody from the IP protocol. Although the lower panel (pRb substrate) shows no signal in the scanned image, a weak signal was evident on the autograms in lanes 5 and 6. (B) Four autoradiograms from replicate experiments were scanned by a phosphoimager to quantitate Cdk5-associated H1 kinase activity (left panel), and pRb kinase activity (right panel). T indicates 1,25D3-treated cells; C, untreated control cells. The differences between values in lanes 2 versus 4 (the pairs identified by an asterisk) were not statistically significant (P < .05) for both substrates (histone H1 and pRb), whereas the differences between pairs identified with the symbol # (lanes 2 and 6) were highly significant (P > .01). (C) Lane 1, Cdk5-associated kinase activity from untreated HL60 cells using histone H1 as the substrate; lane 2, Cdk5-associated kinase activity from HL60 cells treated with 10−7M 1,25D3 for 48 hours; lane 3, as lane 2, but in the presence of 2 μg Ab to p35Nck5a; lane 4, as lane 2, but in the presence of 2 μg Ab to cyclin D1; lane 5 background, determined as in the last lane of Figure 3A. (D) Quantitation of experiments illustrated in Figure 3C, performed as described for Figure 3B.

Immunodepletion of p35Nck5a reduces Cdk5-associated kinase activity.

(A) Cdk5-associated kinase activity on 2 in vitro substrates histone H1 (H1) and the retinoblastoma protein (pRb) is shown for lysates of undifferentiated HL60 cells (lanes 1, 3, and 5), and lysates of HL60 cells treated with 10−7M 1,25D3 for 96 hours (lanes 2, 4, 6, and 7). The first 2 lanes show Cdk5-associated kinase activity of the cell lysates, lanes 3 and 4 the Cdk5-associated kinase activity after immunodepletion of the lysate with an antibody to cyclin D1, and lanes 5 and 6 after immunodepletion of the lysate with an antibody to p35Nck5a. Lane 7 shows a nonspecific signal that was obtained by subjecting the lysates of HL60 cells differentiated with 1,25D3 to the immunoprecipitation procedure but omitting the Cdk5 antibody from the IP protocol. Although the lower panel (pRb substrate) shows no signal in the scanned image, a weak signal was evident on the autograms in lanes 5 and 6. (B) Four autoradiograms from replicate experiments were scanned by a phosphoimager to quantitate Cdk5-associated H1 kinase activity (left panel), and pRb kinase activity (right panel). T indicates 1,25D3-treated cells; C, untreated control cells. The differences between values in lanes 2 versus 4 (the pairs identified by an asterisk) were not statistically significant (P < .05) for both substrates (histone H1 and pRb), whereas the differences between pairs identified with the symbol # (lanes 2 and 6) were highly significant (P > .01). (C) Lane 1, Cdk5-associated kinase activity from untreated HL60 cells using histone H1 as the substrate; lane 2, Cdk5-associated kinase activity from HL60 cells treated with 10−7M 1,25D3 for 48 hours; lane 3, as lane 2, but in the presence of 2 μg Ab to p35Nck5a; lane 4, as lane 2, but in the presence of 2 μg Ab to cyclin D1; lane 5 background, determined as in the last lane of Figure 3A. (D) Quantitation of experiments illustrated in Figure 3C, performed as described for Figure 3B.

In the complementary experiment, kinase activity of Cdk5 in 1,25D3-treated HL60 cells was assayed in the presence of the antibody to either p35Nck5a or cyclin D1. Panels C and D of Figure3 show that the antibody to p35Nck5a markedly reduced Cdk5 kinase activity, but the antibody to cyclin D1 did not. Together, these data provide strong evidence that p35Nck5a activates Cdk5 in HL60 cells differentiating toward the monocyte.

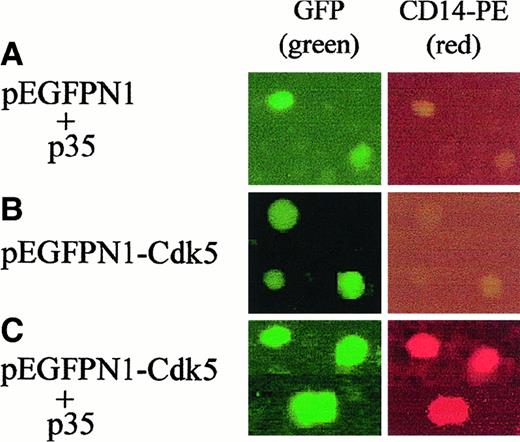

Cdk5 and p35Nck5a are both required for the induction of monocytic phenotype

To further establish the role of the Cdk5-p35Nck5a complex in monocytic differentiation, we prepared a plasmid encoding a fusion protein consisting of the green fluorescent protein and Cdk5, and transfected this fusion protein into undifferentiated HL60 cells, alone or as a cotransfection with p35Nck5a. After 24 hours the cells were stained with PE-labeled antibody to CD14, and the cells were examined under a fluorescent microscope using different filters. Figure4 shows that transfection of Cdk5 and p35Nck5a together resulted in the expression in HL60 cells of the monocytic marker CD14 (Figure 4C), whereas the expression of either p35Nck5a (Figure 4A), or Cdk5 (Figure 4B) alone, did not. Although a high level of expression of the CD14 differentiation antigen is characteristic of monocytes and macrophages,24 it can also be demonstrated following activation of granulocytes by lipopolysaccharide.25,26 Therefore, to confirm the monocytic differentiation of cells cotransfected with Cdk5 and p35Nck5a, we stained the cells for “nonspecific esterase” which identifies the monocytic phenotype.27 Table1 shows that such cotransfection resulted in a highly significant increase in the expression of this monocytic marker, whereas transfection of Cdk5 or p35Nck5a alone did not. The increase in NSE positivity in cotransfected cells is similar in magnitude to the increase seen after 24 hours of exposure to 1,25D3, an inducer of monocytic phenotype,14but atRA, an inducer of granulocytic phenotype,22 did not induce NSE positivity (Table 1). Together, these results confirm that p35Nck5a is an activator of Cdk5, which promotes monocytic differentiation.

Transfection of Cdk5 together with p35NcK5a induces a monocytic phenotype.

(A) Undifferentiated HL60 cells were transfected by electroporation with the pEGFPN1 plasmid, which can express the green fluorescent protein (GFP), together with p35Nck5a, or (B) with a plasmid expressing GFP-Cdk5 fusion protein alone, or (C) cotransfected with pEGFPN1-Cdk5 together with a plasmid expressing p35Nck5a. The transfected cells were incubated for 24 hours, then stained with PE-labeled antibody to CD14, a marker of myeloid monocytic phenotype, and examined under a fluorescent microscope using different filters. The green color (FITC filter 488-509 nm) indicates the expression of the GFP protein, whereas the red color (rhodamine filter 504-534 nm) shows monocytic differentiation. Note that transfection of Cdk5 and p35Nck5a together induces the monocytic marker. These experiments were repeated 4 times. Magnification, × 200.

Transfection of Cdk5 together with p35NcK5a induces a monocytic phenotype.

(A) Undifferentiated HL60 cells were transfected by electroporation with the pEGFPN1 plasmid, which can express the green fluorescent protein (GFP), together with p35Nck5a, or (B) with a plasmid expressing GFP-Cdk5 fusion protein alone, or (C) cotransfected with pEGFPN1-Cdk5 together with a plasmid expressing p35Nck5a. The transfected cells were incubated for 24 hours, then stained with PE-labeled antibody to CD14, a marker of myeloid monocytic phenotype, and examined under a fluorescent microscope using different filters. The green color (FITC filter 488-509 nm) indicates the expression of the GFP protein, whereas the red color (rhodamine filter 504-534 nm) shows monocytic differentiation. Note that transfection of Cdk5 and p35Nck5a together induces the monocytic marker. These experiments were repeated 4 times. Magnification, × 200.

Comparison of the induction of NSE-positive HL60 cells by 1,25D3 or by cotransfection of cyclin-dependent kinase 5 and p35Nck5a

| Treatment* . | NSE-positive cells (%)† . | Significance‡ (P value) . |

|---|---|---|

| None | 4.4 ± 0.8 | — |

| atRA | 2.5 ± 0.8 | .26 |

| 1,25D3 | 27.5 ± 4.2 | .02 |

| pEGFPN1 − Cdk5 | 7.0 ± 0.61-153 | — |

| pEGFPN1 + p35 | 10.0 ± 0.31-153 | .43 |

| pEGFPN1 − Cdk5 + p35 | 31.2 ± 0.81-153 | < .01 |

| Treatment* . | NSE-positive cells (%)† . | Significance‡ (P value) . |

|---|---|---|

| None | 4.4 ± 0.8 | — |

| atRA | 2.5 ± 0.8 | .26 |

| 1,25D3 | 27.5 ± 4.2 | .02 |

| pEGFPN1 − Cdk5 | 7.0 ± 0.61-153 | — |

| pEGFPN1 + p35 | 10.0 ± 0.31-153 | .43 |

| pEGFPN1 − Cdk5 + p35 | 31.2 ± 0.81-153 | < .01 |

NSE indicates nonspecific esterase; atRA, all-trans retinoic acid; Cdk5, cyclin-dependent kinase 5.

Cells examined at 24 hours after initiation of treatment or transfection.

Mean ± SD; n = 4.

Significance was determined by 2-tailed Studentt test, comparing untreated versus treated cells in the top 3 rows, and Cdk5 transfected cells versus p35, or p35 and Cdk5 cotransfected cells, in the bottom 3 rows.

Percentage of transfected cells as determined by green fluorescence.

Discussion

It is currently believed that the Cdk5 activator protein p35Nck5a is exclusively expressed in neuronal cells,28,29 and that Cdk5-associated kinase activity can only be detected in brain lysates.30 Mice with p35 knockout show abnormalities in neuronal development, seizures, and adult lethality,8 but although hematopoietic system defects were not reported, their absence has not been specifically excluded. We demonstrate here that hematopoietic cells that display monocytic phenotype also express p35Nck5a and have Cdk5-associated kinase activity. Further, we show that pRb is an in vitro substrate for Cdk5-associated kinase activity, and that the exogenous Cdk5 and p35Nck5a cotransfected into undifferentiated human leukemia HL60 cells induce markers of monocytic differentiation. Although it is possible that ectopic expression of p35 results in a nonspecific “overexpression” phenotype, our previous finding14 that a partial knockout of Cdk5 in HL60 cells with antisense to Cdk5 reduces monocytic differentiation of these cells argues against this interpretation of the transfection experiments. Taken together, our data provide evidence for a functional link between Cdk5 activity and monocytic differentiation.

Earlier studies of Cdk5 showed that D-type cyclins and cyclin E can bind to Cdk5,8-14 but no evidence was obtained that these cyclins can activate Cdk5. For instance, in HL60 cells induced to differentiate by 1,25D3 there is increased expression of cyclin D1, but not cyclin D3, and cyclin D1 is present in complexes with Cdk5.14 However, cyclin D1 was associated with Cdk5 irrespective of whether these complexes were active as kinases, or inactive,14 making it unlikely that cyclin D1 regulates the activity of Cdk5 in HL60 cells. Immunodepletion experiments presented here support that p35Nck5a, but not cyclin D1, activates Cdk5 in differentiated HL60 cells; depletion of cyclin D1 from cell lysates did not significantly reduce Cdk5-associated kinase activity, but lysates depleted of p35Nck5a were essentially devoid of Cdk5-associated kinase activity (Figure 3A), and the antibody to p35Nck5a blocked Cdk5 kinase activity (Figure 3B). It will be interesting to determine whether there are 2 types of Cdk5 complexes in differentiated HL60 cells—some complexes containing cyclin D1 and other complexes containing p35Nck5a, or if the same Cdk5 molecule associates simultaneously with cyclin D1 and p35Nck5a.

Differentiation therapy is an emerging option for treatment of human leukemia, as illustrated by the success of atRA in inducing remissions in acute promyelocytic leukemia.31-33 Further advances in this field are likely to depend on the identification of key regulators of this process. In this context, we show here that p35Nck5a has a role in monocytic differentiation of promyeloblastic leukemia cells.

We are grateful to Dr Li-Huei Tsai, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Harvard Medical School, for the generous gift of the plasmids pCMV-p35, pCMV-Cdk5, and PCMV-Cdk5HA, and to Dr Hua Zhu, New Jersey Medical School, for pEGFPN1 and for the use of the fluorescent microscope. We also thank Dr Milan Uskokovic, Hoffmann-La Roche, for the gift of 1,25D3 and Dr Jonathan Harrison and Nicholas Megjugorac, NJMS, for help in the separation of normal blood cells.

Supported by National Institutes of Health grant 2R01-44722 from the National Cancer Institute.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

George P. Studzinski, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, UMDNJ–New Jersey Medical School, 185 S Orange Ave, Newark, NJ 07103; e-mail: studzins@umdnj.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal