A single dose of Mpl ligand (Mpl-L) given immediately after lethal DNA-damaging regimens prevents the death of mice. However, the mechanism of this myeloprotection is unknown. The induction of p53-dependent apoptosis in response to DNA damage signals suggests that immediate administration of Mpl-L may inhibit p53-dependent apoptosis. This hypothesis was tested by administering a single injection of pegylated murine Megakaryocyte Growth and Development Factor (PEG-rmMGDF, a truncated recombinant Mpl-L) top53−/−and wild-type mice immediately after carboplatin (80 mg/kg) and 7.5 Gy total body γ-irradiation. PEG-rmMGDF was required to prevent the death of wild-type mice, whereas p53−/−mice survived with or without the exogenous cytokine. The degree of platelet depression and subsequent recovery was comparable in p53−/−mice to wild-type animals given PEG-rmMGDF. Hence, either Mpl-L administration or p53-deficiency protected multipotent hematopoietic progenitors and committed megakaryocyte precursors. The myelosuppressive regimen induced expression of p53 and the p53 target, p21Cipl in wild-type bone marrow, indicating that Mpl-L acts downstream of p53 to prevent apoptosis. Constitutive expression of the proapoptotic protein Bax, was not further increased. Bax−/− mice survived the lethal regimen only when given PEG-rmMGDF; however, these Bax−/−mice showed more rapid hematopoietic recovery than did identically-treated wild-type mice. Therefore, administration of Mpl-L immediately after myelosuppressive chemotherapy or preparatory regimens for autologous bone marrow transplantation should prevent p53-dependent apoptosis, decrease myelosuppression, and reduce the need for platelet transfusions.

Introduction

Recent studies indicate that Mpl ligand (Mpl-L) reduces hematopoietic toxicity much more effectively when administered immediately after a myelosuppressive insult than when given beforehand or at later times.1-5 However, the mechanism of this multilineage myeloprotection has not been defined.

The involvement of Mpl-L (also known as thrombopoietin or TPO) and its receptor Mpl in early hematopoiesis is consistent with the following observations: (1) Mpl is expressed on the AA4+Sca+ subpopulation of murine hematopoietic stem cells6; (2) Mpl-L stimulates the expansion of very immature precursors both in vitro and in vivo; and (3) Mpl and Mpl-L are required for optimal multilineage hematopoietic development, as well as for thrombocytopoietic differentiation. This latter point is evident by marked reductions in granulocyte-macrophage, erythroid, and multipotential progenitor cells in Tpo−/− and c-Mpl−/− mice,7,8 suggesting that Mpl and Mpl-L play significant roles in both megakaryocyte maturation and in the maintenance of multipotential hematopoietic progenitors.9,10 Signaling by Mpl-L, alone or in combination with other early-acting cytokines, also promotes the survival of primitive multipotent progenitor cells by blocking apoptosis.11-13

Recent studies indicate that p53 mediates apoptosis of hematopoietic progenitors exposed to DNA-damaging drugs or γ-irradiation.14,15 In vivo studies have suggested that p53-deficient mice survive a lethal radiation dose due to increased bone marrow resistance.16,17 Furthermore, p53 appears to be a key regulator of the proliferation of hematopoietic progenitors, as p53 status influences both long- and short-term repopulation following bone marrow transplantation. However, p53 does not appear to affect the lineage determination or differentiation of committed progenitor/precursor cells.14

Here we report that administration of a single dose of polyethylene glycol-conjugated recombinant murine Megakaryocyte Growth and Development Factor (PEG-rmMGDF), a truncated form of Mpl-L, is sufficient to prevent p53-dependent apoptosis in a murine model of lethal myelosuppression. These findings suggest that Mpl-L may be clinically useful in reducing neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and anemia caused by myelosuppressive treatments, such as radiation or chemotherapy, and by preparatory regimens for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Materials and methods

Reagents and animals

PEG-rmMGDF is a recombinant form of the amino-terminal half of the native murine Mpl ligand, TPO. Conjugation with polyethylene glycol (pegylation) increases the in vivo potency of this protein approximately 10- to 20-fold, largely by delaying its clearance and thus prolonging its plasma half life. PEG-rmMGDF was kindly provided by Amgen (Thousand Oaks, CA). On the day of administration, the stock solution was diluted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 1% isologous mouse serum.

p53-knockout mice (C57Bl/6) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME), and were studied at 2.5 months of age, prior to the development of tumors. Atm−/−and wild-type littermates (B6/129) were kindly provided by Dr Peter McKinnon of St Jude Children's Research Hospital.34 Breeding stocks ofBax−/−mice (B6/129) were obtained from Dr Stanley Korsmeyer of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA.

Myelosuppressive regimen

Mice were given 80 mg/kg carboplatin (Bristol Laboratories, Princeton, NJ) intravenously followed by 7.5 Gy total body irradiation (TBI) from a 137Cs source (J. L. Shepherd, San Fernando, CA). Mice that had undergone bone marrow transplantation received a reduced TBI dose of 7.0 Gy.

Bone marrow transplantation

Bone marrow was collected from femurs and tibias of appropriate donor mice and suspended in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) with 10% fetal calf serum. Recipients were exposed to 11.25 Gy and given donor cells intravenously within 2 hours after irradiation. Each recipient received the marrow from 1 to 2 bones. Mice were used in experiments 2 to 4 months after transplantation, after blood cell indices had returned to the normal range.

Administration of PEG-rmMGDF

A single dose of PEG-rmMGDF (50 or 65 μg/kg) was injected into a lateral tail vein after vasodilation was induced by warming under an examination lamp. An equivalent volume of PBS with 1% isologous mouse serum (carrier) was injected intravenously into control mice.

Blood cell counts

Blood was collected into ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA)–coated 20-μL microcapillary tubes (CDC Technologies, Oxford, CT) and immediately diluted in buffered diluent. Platelet counts, white blood cell (WBC) counts, and hemoglobin concentration were measured by a MASCOT Automated Hematology System (CDC Technologies).

Bone marrow colony assays

Mice were injected intravenously with 80 mg/kg carboplatin and irradiated with 7.5 Gy. Immediately afterward, half of the animals were injected intravenously with 65 μg/kg PEG-rmMGDF. Bone marrow cells were aseptically harvested from mouse femurs and tibias by flushing the bone marrow cavity with 2 mL α-MEM (minimum essential medium: with Earle salts and with L-glutamine; Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) containing 2% fetal bovine serum (FBS). A cell suspension was prepared by passing the bone marrow through a 25-gauge needle. The concentration of nucleated cells in the bone marrow cell suspension was determined after dilution in 3% acetic acid to lyse erythrocytes. Diluted cell suspensions and recombinant mouse interleukin 3 (rmIL-3) were mixed with methylcellulose (MethoCult M3230; Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada). The cell suspensions were plated in duplicate in 35-mm culture dishes in medium that contained a final concentration of 0.9% methycellulose, 30% FBS, 1% bovine serum albumin, 0.1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, and 2 mM L-glutamine, and were cultured at 37°C with 5% CO2. For day 1 assays, 1 to 2 × 106cells per dish were cultured in 20 U/mL rmIL-3. For day 2 assays, due to the lower bone marrow cellularity at this time after treatment, fewer cells (0.4 × 106 per dish) were plated. Colonies were scored on day 13, and colony sizes were classified as large (> 500 cells/colony), medium (200-400 cells/colony), or small (15-150 cells/colony). Results were expressed as the numbers of colonies per 106 cells plated.

Immunoblot analyses

Bone marrow was collected from mouse femurs and tibias by flushing the bone marrow cavity with 1X DPBS (Dulbecco phosphate-buffered saline, Life Technologies). Bone marrow cells were washed twice in EHS buffer (1 mM Na2EDTA, 10 mM HEPES pH 7.6, and 150 mM NaCl) and were collected by centrifugation at 900g, 4°C for 10 minutes. Cell pellets were suspended in 60 volumes of EHS buffer and cells were lysed by boiling after addition of one-third volume of Laemmli gel sample buffer (125 mM Tris-HCL pH 6.8, 40% glycerol, 8% SDS, 160 mM dithiothreitol, and 0.01% bromphenol blue). Proteins (50-150 μg per lane) were electrophoretically separated in 7.5% to 15% linear polyacrylamide gradients or 12% polyacrylamide gels containing sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Protran; Schleicher & Schuell, Dassel, Germany) and blotted with antibodies specific for p53 (AB-7, Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA), Bax and p21Cip1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), and actin (Boehringer-Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN). Bound immune complexes were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL reagent; Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL, or Supersignal, Pierce, Rockford, IL).

Results

A single dose of Mpl-L or loss of p53 protects mice from lethal myelosuppression

Recent studies using mouse models have established that administration of a single high dose of Mpl-L immediately after a lethal myelosuppressive regimen promotes hematopoietic recovery and prevents death.1-5 The p53 tumor suppressor protein is an important mediator of apoptosis in response to chemotherapeutic DNA-damaging agents and γ-irradiation4 14 and therefore may contribute to the pathogenicity associated with myelosuppression. The rationale and hypothesis of our studies was that if Mpl-L was acting to prevent cell death through a p53-dependent pathway, then Mpl-L administration to p53−/− mice given a myelosuppressive regimen should provide no further hematopoietic protection over carrier-treated p53-null animals subjected to the same DNA damage. Alternatively, if the cytokine blocks cell death via another pathway, p53−/−mice treated with DNA-damaging agents and Mpl-L should display less myelosuppression and faster hematopoietic recovery than p53−/−mice given myelosuppression and carrier alone. In this case, the Mpl-L protective effect should be additive to the loss of p53 function.

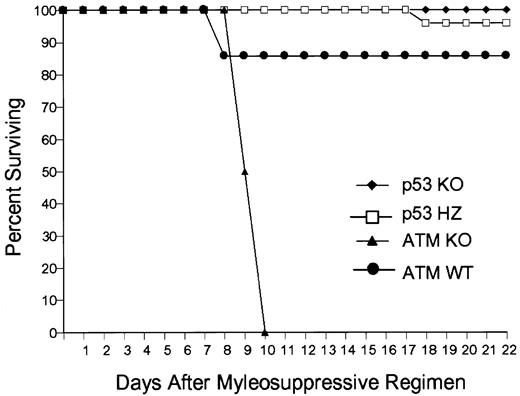

To determine the role of p53 in this response, and whether the protective effect of Mpl-L is due to its ability to inhibit p53-dependent apoptosis, we exposed p53-deficient mice to a myelosuppressive regimen that is lethal to wild-type (WT) mice. The WT and p53−/−groups of mice were subdivided immediately following exposure to the lethal myelosuppressive treatment; half of each group was given a single intravenous (IV) injection of PEG-rmMGDF (50 μg/kg), and half (the control group) received 1% normal mouse serum. In 3 such experiments, all WT mice treated with PEG-rmMGDF survived; however, all control WT mice died (Figure 1). By contrast, almost allp53−/−mice survived, with or without PEG-rmMGDF. Therefore, the primary mechanism of lethal myelosuppression was p53-dependent.

Administration of Mpl ligand or loss of p53 protects mice from lethal myelosuppression.

Survival of p53−/−mice (knockout [KO]; n = 22) and wild-type mice (WT C57BL/6J; n = 15) that were given 50 μg/kg of PEG-rmMGDF immediately after receiving 80 mg/kg carboplatin intravenously and 7.5 Gy TBI. Control groups of the same sizes were given carrier (1% normal mouse serum in PBS) instead of PEG-rmMGDF.

Administration of Mpl ligand or loss of p53 protects mice from lethal myelosuppression.

Survival of p53−/−mice (knockout [KO]; n = 22) and wild-type mice (WT C57BL/6J; n = 15) that were given 50 μg/kg of PEG-rmMGDF immediately after receiving 80 mg/kg carboplatin intravenously and 7.5 Gy TBI. Control groups of the same sizes were given carrier (1% normal mouse serum in PBS) instead of PEG-rmMGDF.

p53 promotes survival of bone marrow–derived progenitor cells exposed to carboplatin and γ-irradiation

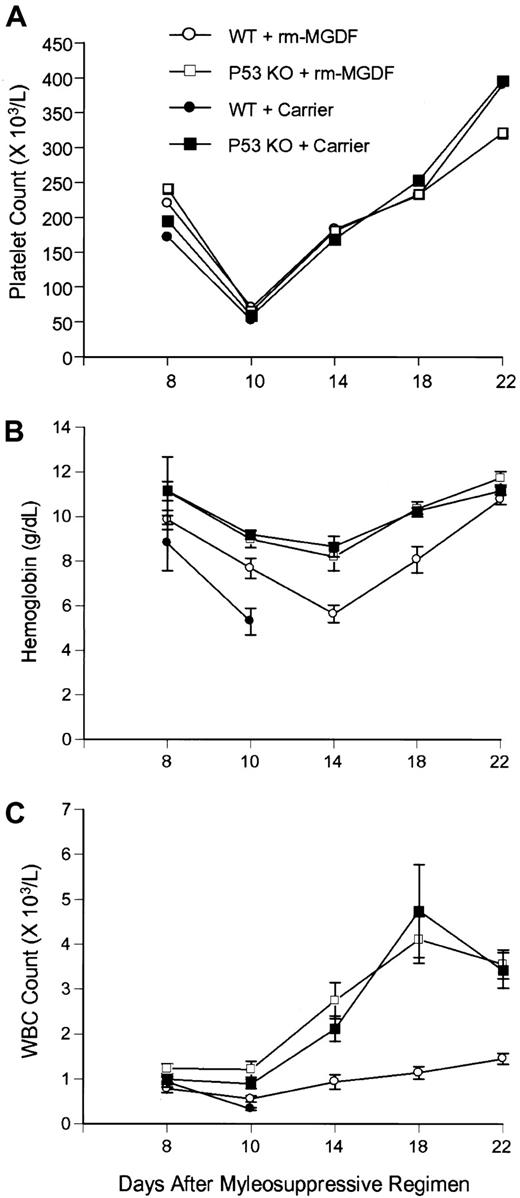

To clarify the mechanism by which p53 loss contributes to survival, we measured the extent of myelosuppression and the rate of subsequent hematopoietic recovery in both WT and p53-deficient mice. WT and p53−/− mice treated with PEG-rmMGDF, as well as p53−/− animals injected with carrier alone, experienced nearly identical courses of platelet suppression and recovery following carboplatin and γ-irradiation (γ-IR), whereas platelet counts of carrier-treated WT mice failed to recover (Figure2A). These results were confirmed in 2 repeat experiments. In contrast, the declines in WBC and hemoglobin values were significantly less severe in p53−/−mice, with or without PEG-rmMGDF treatment, as compared with WT animals given PEG-rmMGDF (Figure 2B-C). Wild-type mice treated with PEG-rmMGDF had appreciably lower WBC counts than did the 2p53−/− groups between days 8 and 22 after treatment (P < .02-.001 in 3 experiments). Similarly, decreases in hemoglobin concentration were significantly greater in WT mice given PEG-rmMGDF than in both groups of p53−/−mice on day 14 (P < .005-.001 in 3 experiments). The hemoglobin levels of WT mice treated with PEG-rmMGDF did recover to a level equal to that of p53−/− mice by day 22 (Figure 2B). By contrast, PEG-rmMGDF administration did not enhance hematopoietic recovery in p53−/− mice. Collectively, these findings suggest that thrombopoiesis is protected to the same extent in PEG-rmMGDF–treated WT mice and inp53−/− mice by conferring survival to c-Mpl–expressing multipotential hematopoietic precursors and committed megakaryocyte progenitors. In contrast, granulopoiesis and erythropoiesis are protected less efficiently by PEG-rmMGDF in WT mice than in p53−/− mice because committed granulocyte and erythroid precursors do not express c-Mpl.

Effect of Mpl ligand on hematopoietic suppression and recovery in wild-type and

p53−/− mice after lethal myelosuppression. The effects of PEG-rmMGDF administered immediately after carboplatin and γ-IR on platelet count (A), hemoglobin concentration (B), and WBC count (C), inp53−/−mice (7 mice) and wild-type C57Bl/6J mice (7 mice). As controls, p53−/−mice and wild-type mice (7 mice per group) were treated with carrier. Each point represents ± SEM. The trends were reproducible in 2 subsequent experiments.

Effect of Mpl ligand on hematopoietic suppression and recovery in wild-type and

p53−/− mice after lethal myelosuppression. The effects of PEG-rmMGDF administered immediately after carboplatin and γ-IR on platelet count (A), hemoglobin concentration (B), and WBC count (C), inp53−/−mice (7 mice) and wild-type C57Bl/6J mice (7 mice). As controls, p53−/−mice and wild-type mice (7 mice per group) were treated with carrier. Each point represents ± SEM. The trends were reproducible in 2 subsequent experiments.

To demonstrate that p53-knockout mice survive the lethal myelosuppression regimen through increased hematopoietic cell survival, we examined WT mice transplanted with p53−/−or p53+/− bone marrow. After the peripheral blood cell counts of the recipient mice had recovered following transplantation, we exposed the animals to a lethal dose of carboplatin (80 mg/kg) and γ-IR (7 Gy TBI). All mice receivingp53−/− bone marrow cell transplants (n = 7) survived, whereas all mice receiving p53+/−bone marrow transplants (n = 4) died within 19 days. Therefore,p53-deficient mice survive the lethal myelosuppressive regimen due to an intrinsic resistance of hematopoietic progenitors to DNA damage.

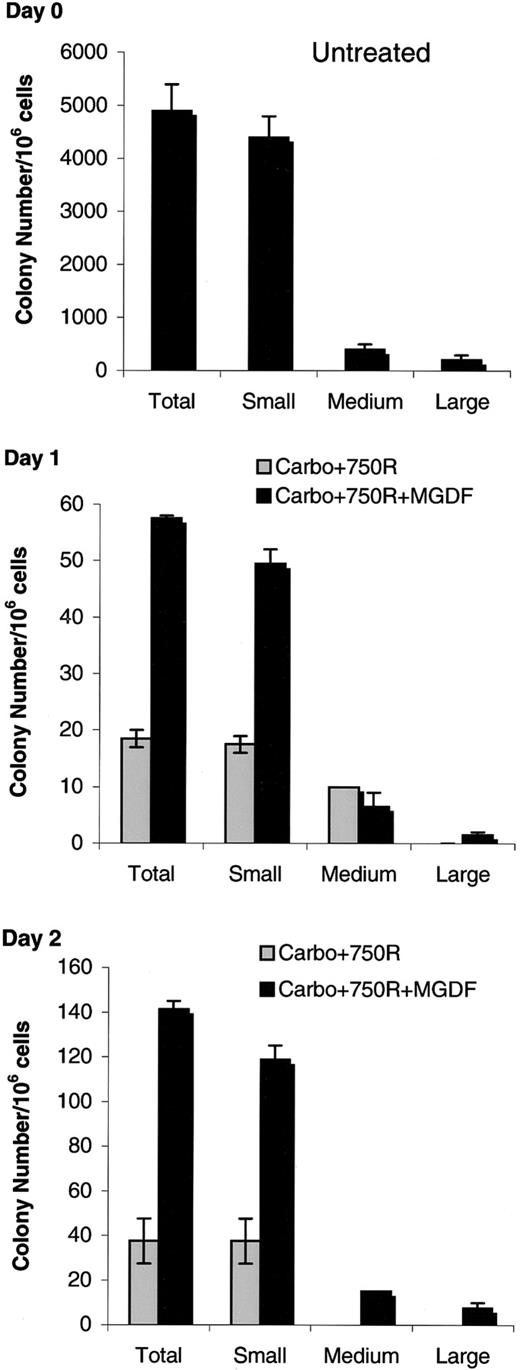

Rescue of bone marrow progenitors by administration of Mpl-L

To determine whether the beneficial effects of PEG-rmMGDF targeted progenitor cells, we compared the in vitro colony-forming ability of bone marrow cells harvested on days 1 and 2 after the myelosuppressive regimen to that of marrow from WT untreated mice. Bone marrow obtained from these mice was plated in methylcellulose containing IL-3, and colony number and size were scored after 13 days. Colony formation from marrow of mice treated with PEG-rmMGDF or carrier and collected on day 1 and day 2 after treatment was markedly decreased compared with that of untreated marrow (Figure 3). However, bone marrow cells collected at 24 and 48 hours generated significantly greater colony numbers and sizes when derived from mice treated with PEG-rmMGDF as compared with carrier-treated mice (P < .05) (Figure 3, middle and bottom panels). Furthermore, bone marrow from mice given the myelosuppression regimen and PEG-rmMGDF yielded a full spectrum of colony sizes, whereas bone marrow from those mice exposed to the myelosuppressive regimen without PEG-rmMGDF formed predominantly small colonies (Figure 3, middle and bottom panels). Therefore, Mpl-L promotes hematopoietic recovery by protecting bone marrow progenitors from DNA-damaging insults. Colony formation by untreated p53−/− marrow cells was not significantly different than that of untreated WT marrow (Figure4, top panel). As in Figure 3, colony formation from WT mice treated with PEG-rmMGDF at day 2 after treatment was significantly higher than that of carrier-treatedp53+/+ mice (P < .005) (Figure 4, middle panel). In contrast, there was no additional protective effect of Mpl-L on the colony formation by bone marrow cells ofp53−/− mice collected at 48 hours after the myelosuppressive regimen as the number of colonies derived from the Mpl-L– and carrier-treated p53−/− mice were not different (Figure 4, bottom panel). This trend was confirmed in a repeat experiment.

Mpl ligand promotes survival of hematopoietic progenitor cells.

Mice were given 80 mg/kg carboplatin intravenously, and 7.5 Gy Cs-137 TBI, then either PEG-rmMGDF or carrier (1-2 mice per group). Bone marrow cells were collected 1 (middle panel) or 2 (bottom panel) days later and plated in methylcellulose-containing medium with IL-3 (2 dishes per bone marrow sample). Colonies were scored on day 13, and colony sizes were classified as large (> 500 cells/colony), medium (200-400 cells/colony), or small (15-150 cells/colony). Untreated (top panel) colonies formed from bone marrow collected from mice that received no carboplatin/TBI. Bars represent means ± SEM.

Mpl ligand promotes survival of hematopoietic progenitor cells.

Mice were given 80 mg/kg carboplatin intravenously, and 7.5 Gy Cs-137 TBI, then either PEG-rmMGDF or carrier (1-2 mice per group). Bone marrow cells were collected 1 (middle panel) or 2 (bottom panel) days later and plated in methylcellulose-containing medium with IL-3 (2 dishes per bone marrow sample). Colonies were scored on day 13, and colony sizes were classified as large (> 500 cells/colony), medium (200-400 cells/colony), or small (15-150 cells/colony). Untreated (top panel) colonies formed from bone marrow collected from mice that received no carboplatin/TBI. Bars represent means ± SEM.

Effect of Mpl ligand on survival of hematopoietic progenitor cells from marrow of myelosuppressed p53

−/− mice compared with carrier-treated p53−/− mice. Mice were given 80 mg/kg carboplatin intravenously, and 7.5 Gy Cs-137 TBI, then either PEG-rmMGDF or carrier (1-2 mice per group). Bone marrow cells were collected 2 days later and plated in methylcellulose-containing medium with IL-3 (2 dishes per bone marrow sample). Colonies were scored on day 13, and colony sizes were classified as large (> 500 cells/colony), medium (200-400 cells/colony), or small (15-150 cells/colony). Untreated (top panel) colonies formed from bone marrow collected from mice that received no carboplatin/TBI. Bars represent mean ± SEM. The trend was reproducible in a repeat experiment.

Effect of Mpl ligand on survival of hematopoietic progenitor cells from marrow of myelosuppressed p53

−/− mice compared with carrier-treated p53−/− mice. Mice were given 80 mg/kg carboplatin intravenously, and 7.5 Gy Cs-137 TBI, then either PEG-rmMGDF or carrier (1-2 mice per group). Bone marrow cells were collected 2 days later and plated in methylcellulose-containing medium with IL-3 (2 dishes per bone marrow sample). Colonies were scored on day 13, and colony sizes were classified as large (> 500 cells/colony), medium (200-400 cells/colony), or small (15-150 cells/colony). Untreated (top panel) colonies formed from bone marrow collected from mice that received no carboplatin/TBI. Bars represent mean ± SEM. The trend was reproducible in a repeat experiment.

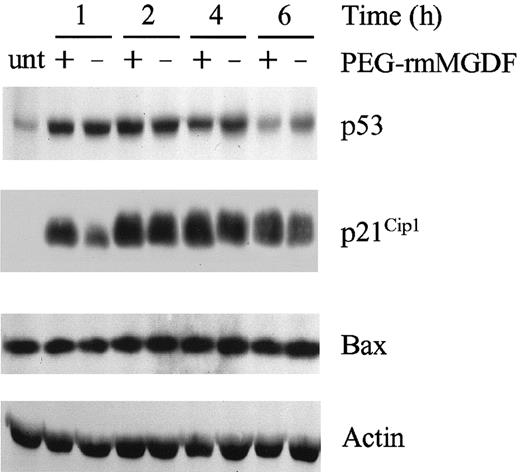

Effect of Mpl-L administration on the p53 pathway in bone marrow cells

p53 is an important regulator of the DNA damage response in mammalian cells. DNA damage is followed by rapid accumulation and activation of p53 that induces the expression of a number of downstream target genes, resulting in cell cycle arrest or apoptosis.18 To assess the function of the p53 pathway in response to our myelosuppression regimen, we analyzed the expression of p53 and 2 of its transcription targets (p21Cip1 and Bax) in bone marrow cells at specific time intervals following carboplatin and γ-IR exposure by immunoblotting (Figure5). In response to this regimen, levels of p53 protein increased rapidly and were sustained for at least 6 hours before declining; PEG-rmMGDF administration did not significantly alter the magnitude or the kinetics of p53 induction (Figure 5, repeated in 5 separate experiments). Bax, a proapoptotic factor that is up-regulated by p53 in some cell types,19-23 was constitutively expressed in bone marrow cells exposed to the DNA-damaging regimen and unaffected by the administration of PEG-rmMGDF. By contrast, expression of p21Cip1,a cyclin kinase inhibitor,24 was markedly induced following carboplatin and γ-IR and this response paralleled the induction of p53 (Figure 5). PEG-rmMGDF had no consistent differential effect on the induction of p21 during DNA damage, indicating that the beneficial effect of Mpl-L on hematopoietic cells is not due to a direct disruption of the p53 response; instead, Mpl-L appears to act downstream of p53 to prevent apoptosis (see “Discussion”).

Treatment with Mpl ligand does not impair the p53 response to carboplatin and radiation.

Bone marrow cells of C57Bl/6J mice (1 mouse per group) were harvested and solubilized at the indicated intervals after treatment with 80 mg/kg carboplatin (administered intravenously) and 7.5 Gy TBI followed immediately by PEG-rmMGDF or carrier. Samples were assessed by immunoblotting for expression of p53, Bax, and p21Cip1. Immunoblotting of actin on the same immunoblot is shown for comparison of protein loading per lane. Unt: untreated (bone marrow cells from C57Bl/6J mice that received no carboplatin/TBI).

Treatment with Mpl ligand does not impair the p53 response to carboplatin and radiation.

Bone marrow cells of C57Bl/6J mice (1 mouse per group) were harvested and solubilized at the indicated intervals after treatment with 80 mg/kg carboplatin (administered intravenously) and 7.5 Gy TBI followed immediately by PEG-rmMGDF or carrier. Samples were assessed by immunoblotting for expression of p53, Bax, and p21Cip1. Immunoblotting of actin on the same immunoblot is shown for comparison of protein loading per lane. Unt: untreated (bone marrow cells from C57Bl/6J mice that received no carboplatin/TBI).

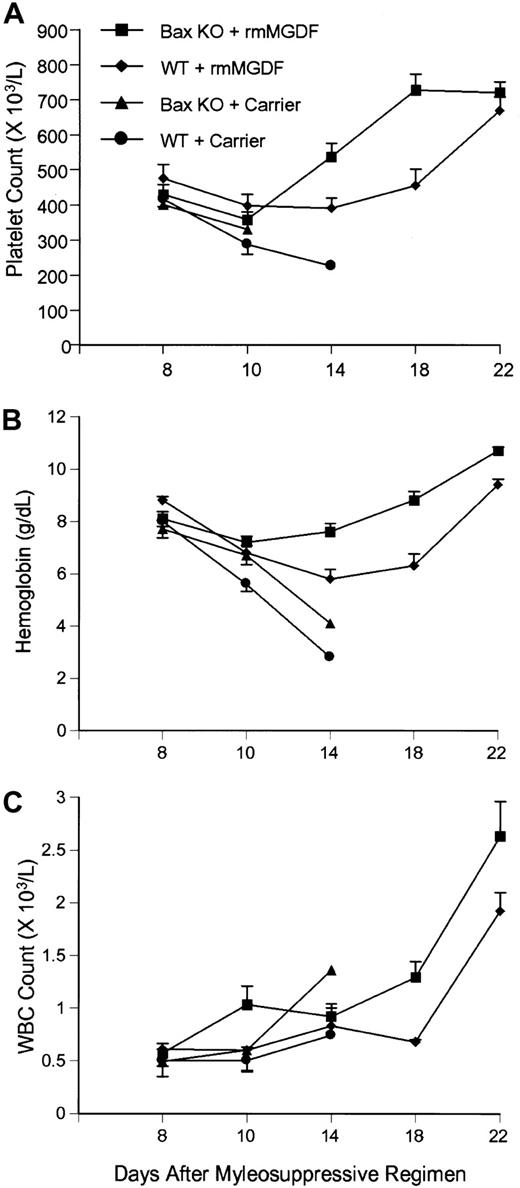

Bax influences hematopoietic recovery following lethal myelosuppression

Previous studies reported that Bax expression is induced in radiosensitive tissues following irradiation.25 By contrast, we observed that carboplatin and γ-IR, with or without administration of PEG-rmMGDF, did not affect the steady-state level of Bax protein in bone marrow cells. These results, however, did not rule out the possibility that small changes in Bax expression and/or posttranslational modifications could significantly regulate the apoptotic response to this myelosuppressive regimen. To assess the role of Bax in p53-mediated apoptosis in our myelosuppression model, we measured the survival and the hematopoietic recovery ofBax−/− mice exposed to carboplatin and γ-IR, and whether PEG-rmMGDF affects this response. Similar to WT littermate animals, Bax−/− mice were highly susceptible to the lethal effects of this DNA-damaging regimen. Assessment of platelet counts, WBC counts, and hemoglobin levels indicated thatBax−/− mice died due to hematopoietic failure (Figure 6A-C) (confirmed in 2 independent experiments). Interestingly, Bax−/− mice treated with PEG-rmMGDF exhibited a more rapid recovery of hemoglobin levels (on day 14, P < .005; days 18 and 22,P < .001), platelet counts (day 14, P < .01 and day 18, P < .001) and WBC counts (day 10,P < .025 and day 18, P < .001) as compared with those of wild-type mice (Figure 6A-C). Thus, although clearly not required, Bax appears to play some role in p53-dependent apoptosis in this myelosuppression model.

Deficiency of Bax enhances Mpl ligand–mediated hematopoietic recovery after the myelosuppressive regimen.

PEG-rmMGDF was immediately administered toBax−/− mice (Bax KO, n = 17) and wild-type (WT, B6/129 mice, usually littermates, n = 17) after lethal myelosuppression. Carrier-treated Bax−/− mice (n = 12) and wild-type mice (n = 10). Each point represents mean ± SEM.

Deficiency of Bax enhances Mpl ligand–mediated hematopoietic recovery after the myelosuppressive regimen.

PEG-rmMGDF was immediately administered toBax−/− mice (Bax KO, n = 17) and wild-type (WT, B6/129 mice, usually littermates, n = 17) after lethal myelosuppression. Carrier-treated Bax−/− mice (n = 12) and wild-type mice (n = 10). Each point represents mean ± SEM.

Loss of Atm compromises Mpl-L rescue from lethal myelosuppression

Atm is a member of the PI-3′ serine/threonine kinase family that phosphorylates and activates p53 in response to certain DNA damage signals.25,26 Loss of Atm in mice and humans is typically associated with attenuated p53 responsiveness and impaired cell cycle arrest. Paradoxically, Atm−/− mice display remarkable susceptibility to DNA-damaging insults,27,28 which appears to be cell-type specific and largely attributable to increased gastrointestinal sensitivity.29 Since p53-null bone marrow progenitors are resistant to DNA damage, we tested whether loss ofAtm would also influence the response of bone marrow–derived progenitors to carboplatin and γ-IR. To this end, we assessed the responses of WT mice receivingAtm−/−, p53−/−, p53+/−, or WT bone marrow transplants to DNA damage. Animals transplanted with Atm−/− marrow and treated with PEG-rmMGDF succumbed earlier to the myelosuppressive regimen than did similarly treated mice transplanted with p53+/− and WT bone marrow, whereas all mice receivingp53−/− transplants survived without PEG-rmMGDF treatment (Figure 7). AllAtm−/−, p53+/−, or WT bone marrow–transplanted mice treated with carrier after exposure to the myelosuppressive regimen died (data not shown). The inability ofAtm−/− bone marrow cells to properly arrest in response to DNA damage presumably overrode the protective effects of Mpl-L, resulting in dramatically earlier hematopoietic death of allAtm−/− mice.

Loss of Atm augments lethal myelosuppression.

The survival of C57Bl/6 mice receiving bone marrow transplants fromAtm−/− (ATM KO, n = 8),p53−/− (p53 KO, n = 7),p53+/− (p53 HZ, n = 6), or wild-type (WT, n = 7) bone marrow. Mice receiving Atm−/−,p53+/−, and wild-type marrow transplants were given PEG-rmMGDF intravenously after exposure to the lethal myelosuppressive regimen.

Loss of Atm augments lethal myelosuppression.

The survival of C57Bl/6 mice receiving bone marrow transplants fromAtm−/− (ATM KO, n = 8),p53−/− (p53 KO, n = 7),p53+/− (p53 HZ, n = 6), or wild-type (WT, n = 7) bone marrow. Mice receiving Atm−/−,p53+/−, and wild-type marrow transplants were given PEG-rmMGDF intravenously after exposure to the lethal myelosuppressive regimen.

Discussion

The mechanism by which Mpl-L protects animals from a lethal myelosuppressive regimen has not been previously established. Myelosuppressive agents such as chemotherapy and γ-IR are known to activate p53-dependent apoptosis.14,15,30 Because Mpl is expressed on multipotential hematopoietic progenitors7-9,31 and its ligand, TPO, prevents apoptosis of these progenitors in vitro,11-13 we hypothesized that Mpl-L protects mice by preventing p53-dependent cell death. If this hypotheses is correct, then Mpl-L administration should not provide greater protection to hematopoiesis in p53−/− mice, as compared with carrier-treated p53-null animals, following a myeloablative regimen. Our findings support this hypothesis: when exposed to the same myelosuppressive insult, p53-deficient mice survived without Mpl-L treatment, whereas WT mice died. Furthermore, p53−/− mice subjected to the myelosuppression regimen and treated with Peg-rmMGDF had the same degree of myelosuppression and hematopoietic recovery profile as the p53−/−mice given the myelosuppressive regimen and carrier alone. These findings indicate that Mpl-L is acting to suppress p53-dependent apoptosis in vivo.

The increased resistance of p53-deficient mice to the carboplatin and γ-IR regimen is consistent with the results of other investigators who have noted that p53−/− mice survive 10 Gy of γ-IR, a dose that is lethal to WT mice.17 Correlative evidence has suggested that the radioresistance of p53-deficient mice is a consequence of reduced apoptosis of bone marrow cells.16 18 The results of our transplantation studies with p53-deficient marrow provide direct proof that the loss of p53 indeed protects mice from lethal myelosuppression; the results also suggest that p53-dependent apoptosis of hematopoietic progenitors leads to hematopoietic failure and death. Nonetheless, carboplatin- and γ-IR–treated p53−/− mice experienced substantial myelosuppression, indicating that hematopoietic cells also die by a p53-independent pathway(s).

We observed interesting differences between the hematopoietic responses of p53-deficient mice given PEG-rmMGDF or carrier versus WT mice given PEG-rmMGDF after the myelosuppressive regimen. Hemoglobin concentration and WBC counts were reduced to a greater extent in WT mice given PEG-rmMGDF than in p53-deficient mice given PEG-rmMGDF or carrier alone. By contrast, the degree of thrombocytopenia in these 3 groups was virtually identical. We speculate that this difference reflects the disparate patterns of Mpl expression on the various hematopoietic progenitors.9 10 In that case, all p53-null multipotential hematopoietic progenitors and committed precursors would be protected from p53-dependent apoptosis, whereas in the normal phenotype, only hematopoietic cells that express Mpl would be protected by Mpl-L. If this view is correct, then concomitant administration of Mpl-L in combination with erythropoietin and granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) immediately after a myelosuppressive insult might optimally reduce the degree of suppression of all 3 committed hematopoietic lineages.

The number of bone marrow–derived colonies generated by cultures with IL-3 was substantially higher in mice that received PEG-rmMGDF after the myelosuppression regimen than carrier-only controls; this finding suggests that Mpl-L protects hematopoietic progenitors. In contrast, the assays of bone marrow–derived colonies generated from myelosuppressed, Mpl-L–treated p53−/− mice compared with carrier-treated p53−/− mice demonstrated no additional protective effect of Mpl-L on colony formation. These results support the conclusion from our in vivo experiments that Mpl-L is acting to suppress p53-dependent apoptosis of hematopoietic cells in vivo.

Our analysis of protein expression provides insight into how Mpl-L prevents p53-dependent apoptosis after the myelosuppressive regimen. The increase in p53 protein levels in bone marrow cells in response to carboplatin and γ-IR was unaffected by Mpl-L administration, indicating that PEG-rmMGDF did not protect hematopoietic cells by directly suppressing p53 expression. Furthermore, the induction ofp21Cip1 expression was not enhanced in carboplatin/radiation-treated WT mice after PEG-rmMGDF injection. These results indicate that Mpl-L does not interfere with the p53 pathway at the level of p53-induction; rather, the cytokine appears to protect bone marrow cells by suppressing p53 function at a downstream step. Furthermore, we have previously demonstrated that cytokines, such as IL-3 and erythropoietin, protect against p53-dependent apoptosis in response to DNA damage by inducing the expression of Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL, both of which are potent suppressors of cell death.32 33 These findings support the hypothesis that cytokines block p53-mediated cell death by antagonizing downstream target genes, such as Bax or other proapoptotic Bcl-2 family members.

Because Bax is directly transactivated by p53 and promotes apoptosis,21 34 we also tested the role of this gene by using Bax-deficient mice in our myelosuppression model. We found that Bax is constitutively expressed in mouse bone marrow cells and that Bax levels are not affected by carboplatin plus γ-IR, or by the administration of PEG-rmMGDF. Consistent with these findings,Bax deficiency did not protect the animals from the lethal dose of carboplatin and γ-IR. However, when PEG-rmMGDF was given, platelet counts, WBC counts, and hemoglobin levels recovered more rapidly in Bax−/− mice than in WT mice, indicating that Bax does play a proapoptotic role in the response of multipotential hematopoietic cells to this myelosuppressive regimen. These findings convincingly demonstrate that loss of Bax is not equivalent to loss of p53 in protecting against lethal myelosuppression and that other downstream factors must mediate p53-dependent apoptosis under these conditions.

The increased radiosensitivity of ATM−/− mice has been attributed to the high level of apoptosis induced in the gastrointestinal tract of these mice29; however, the fact that recipients of Atm−/− bone marrow transplants died at an accelerated rate after the myelosuppressive regimen, and were not protected by PEG-rmMGDF, indicates marrow toxicity plays a major role in the increased sensitivity of these mice to DNA-damaging agents.

In summary, our observations indicate that Mpl-L administered immediately after a lethal myelosuppressive regimen promotes the survival of hematopoietic progenitor cells in vivo by attenuating p53-dependent apoptosis. Myelosuppression is a toxicity-limiting component of chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy, and a major clinical problem in autologous bone marrow transplantation regimens. Administration of Mpl-L during these DNA-damaging treatments should suppress the p53 response, thereby alleviating the severity of neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and anemia and the need for platelet transfusions.

The authors thank Shirley Steward, Nancy Hutson, Jinling Wang, Dr Christine Eischen, Charles M. Strain, and Joseph M. Emmons for outstanding technical assistance; the staff of the St Jude Animal Resources Center for their support; Dr Stanley Korsmeyer for providingBax−/− mice; and Dr Peter McKinnon for providing Atm−/− mice. We thank Sharon Naron for editorial review of this report.

Supported in part by grants CA76379, DK44158 (J.L.C.), CA63230 (G.P.Z.), and CA21765 from National Institutes of Health; by the Assisi Foundation of Memphis; and by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Tamara I. Pestina, Division of Experimental Hematology, St Jude Children's Research Hospital, 332 N. Lauderdale, Memphis, TN 38105-2794; e-mail: tamara.pestina@stjude.org.

![Fig. 1. Administration of Mpl ligand or loss of p53 protects mice from lethal myelosuppression. / Survival of p53−/− mice (knockout [KO]; n = 22) and wild-type mice (WT C57BL/6J; n = 15) that were given 50 μg/kg of PEG-rmMGDF immediately after receiving 80 mg/kg carboplatin intravenously and 7.5 Gy TBI. Control groups of the same sizes were given carrier (1% normal mouse serum in PBS) instead of PEG-rmMGDF.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/98/7/10.1182_blood.v98.7.2084/5/m_h81911609001.jpeg?Expires=1769230819&Signature=h8t~DEyqHgULFA~fxBvYhyql59UaalE7m4FTwhHz-aAIZigaAgh-DJjA517AsLfhOlORTX8b4i7IlStfw-nDXNHXHji88coxNMn7bPWaM21myLl2m7OMpOkoOU0y7n9l597WUHQ9zNo6UJYlu1VNPd0Yr1r~q6qYww-FmEI7~HUVFZpp1GAKcZRi5ZVhEMrKDri331zMv~Ooy2jLxGPJIRhMp-bNDEep5mr1QFNwNp7M6iTS65gRHyGCj58olHIanjpYMm-cF3yENvcnQS7ZmBIywLIInhnALny4nnuZ~pRivJC6Q9nrQS5t1V9XPjp22TUNC7EoRfasW6y48LK7xg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal