Abstract

This article describes the isolation of a novel cell population (B220loc-kit+CD19−) in the fetal liver that represents 70% of T-cell precursors in this organ. Interestingly, these precursors showed a bipotent T-cell and natural killer cell (NK)– restricted reconstitution potential but completely lacked B and erythromyeloid differentiation capacity both in vivo and in vitro. Moreover, not only mature T-cell receptor (TCR)αβ+ peripheral T cells but also TCRγδ+ and TCRαβ+CD8αα+ intestinal epithelial cells of extrathymic origin were generated in reconstituted mice. The presence of this population in the fetal liver of athymic embryos indicates its prethymic origin. The comparison of the phenotype and differentiation potential of B220loc-kit+CD19−fetal liver cells with those of thymic T/NK progenitors indicates that this is the most immature common T/NK cell progenitor so far identified. These fetal liver progenitors may represent the immediate developmental step before thymic immigration.

Introduction

Multipotent hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) differentiate into precursors with increasingly restricted differentiation potential. This process, called lineage commitment, leads to the generation of oligopotent progenitors and finally to cells that are irreversibly engaged in a unique pathway of differentiation. The identification of progenitors at intermediate stages of differentiation is a fundamental step in understanding lineage commitment. The characterization of such intermediates within the erythromyeloid lineages has identified, in the bone marrow (BM), a granulocyte-macrophage–restricted precursor and, more recently, a common myeloid precursor and an erythrocyte-megakaryocyte precursor.1

T-cell generation occurs in the thymus from hematopoietic precursors present in fetal liver (FL) and adult BM. Although the pathways of intrathymic T-cell differentiation are relatively well characterized, the role of the thymic microenvironment as a unique site for the induction of commitment to the T-cell lineage remains a matter of debate.2,3 Moreover, the identification of T-cell progenitors before thymic colonization remains incomplete. Cells endowed with a nonrestricted potential of differentiation into T lymphocytes have been phenotypically characterized and isolated from adult BM. Thus, HSCs as well as common lymphoid progenitors (CLPs) were purified.4 5

The existence of committed T-cell precursors (TCPs) in the BM6 and more recently in the FL has been suggested.7,8 However, the identification of surface markers allowing the isolation of these cells has not been achieved. Populations of precursors restricted to the T-cell and natural killer cell (NK) lineages have been reported in fetal thymus, blood, and spleen.9-13 In 2 independent studies, T and NK precursors have been characterized in fetal thymus either as FcγRII/III+9 or as CD90+NK1.1+CD117+,11although the total number of precursors present at these sites was not evaluated.

We and others have previously reported that the FL, the major hematopoietic organ during embryonic life, provides TCPs with restricted potential of differentiation that continuously colonize the fetal thymus.14-16 In an attempt to identify such intermediate precursors, we isolated different fractions of FL cells and analyzed them in a quantitative manner for lymphocyte precursor activity.

Here we identify a novel population corresponding to 0.2% of FL cells that includes the majority (70%) of TCPs in this organ. These cells retained the capacity to differentiate into both T and NK progeny at the single-cell level. When transferred in vivo, they reconstituted the peripheral T and NK compartments and gave rise to intraepithelial T cells of extrathymic origin. This cell population, designated here as common T/NK cell progenitor (C-TNKP), differs both by surface marker and by gene expression analysis from previously described bipotent T/NK precursors present in fetal blood, spleen, and thymus. We propose that these cells represent the immediate developmental step before thymic immigration.

Materials and methods

Mice

C57BL/6-Ly5.1 mice (Centre de Développement des Techniques Advances, Orleans, France), C57BL/6-Ly5.2 mice (Iffa-Credo, L'Arbresle, France), and C57BL/6-Rag2/γc−/− mice were bred in our animal facility (Institut Pasteur, Paris, France). The day of vaginal plug was considered day 0 of gestation. Timed pregnancies ofnu/+ and nu/nu embryos were obtained from CDTA by crossing female nu/+with male nu/nu mice. Homozygosity for thenu genotype was confirmed by the absence of the thymus.

Cell preparation, immunofluorescence staining, and cell sorting

All the fluorescence-labeled antibodies used in this study were from PharMingen (San Diego, CA). FL cells were depleted of erythroid precursors by magnetic bead depletion (Dynal AS, Oslo, Norway) after incubation with biotin–anti-TER119. Cells were subsequently stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate–anti-CD19 (1D3), phycoerythrin–anti-CD45R/B220 (RA3-6B2), and biotin–anti–c-kit (2B8) antibodies. Cells were separated using a FACStar Plus cell sorter (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA). All sorted cell populations were found to be more than 98% pure. Intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes (i-IELs) were isolated by density gradient as described.17 For the flow cytometric analysis, the following antibodies were used: anti–T-cell receptor (TCR)γδ (3A10), anti-TCRαβ (H57), anti-NK1.1 (PK136), anti–Gr-1 (RB6-8C5) and anti-Ly5.1 (A20), anti-CD8α (Ly2, 53-6.7), anti-CD8β (Ly3.2, 53-5.8), anti-CD4 (L3T4), and anti-CD3ε (145-2C11). Four-color analysis was performed on a FACScalibur (Becton Dickinson) and run on the Cell Quest software (version 3.2; Becton Dickinson). Dead cells were eliminated by propidium iodide exclusion.

In vitro assays

TCP potential.

FL cell suspensions were prepared from 15 to 20 embryos (B6-Ly5.1). TCP potential was determined using the fetal thymic organ culture (FTOC) assay,18 with a slight modification.15 Thymic lobes from day-14 fetuses (B6-Ly5.2) were irradiated with 3000 rad using a cesium γ irradiator. For limiting dilution analysis, cells were resuspended at 4 different concentrations in culture medium. Cells were cocultured with at least 12 individual lobes for each dilution in hanging drops. Individual lobes were examined for the presence of αβ+, γδ+, and NK1.1+ cells of donor origin (Ly5.1+cells) at day 16 of culture. No cells were observed in irradiated lobes that were not colonized. The ratio of negative lobes was scored. Frequency and absolute numbers of TCPs were calculated (based on the Poisson probability distribution) as described previously.15

B-cell precursor potential.

The limiting dilution culture conditions for B-cell precursor potential were described previously.19 After 10 to 14 days of culture, developing pre–B-cell colonies were scored on an inverted microscope. Individual representative colonies were further analyzed by flow cytometry. Cells from each well were further stimulated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS; Salmonella typhosa WO901; Difco) at a final concentration of 25 μg/mL, and IgM secretion was detected by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Frequencies of B-cell precursors were determined according to the Poisson distribution.

NK cell precursor potential.

NK cell precursor potential in vitro was determined after culture of varying numbers (range, 20-180) of FL cells on the OP9 stromal cell line12,36 (kindly provided by Dr Kodama, Kyoto University, Yoshida, Japan), supplemented with interleukin-7 (IL-7) and c-kitligand (KL). Half of the medium was removed and changed every 4 to 6 days. IL-2 was added at day 6 of culture. Individual colonies were analyzed by flow cytometry. NK cell differentiation was also assessed when FL cells were cultured in FTOC (see above, TCP potential). IL-7, KL, and IL-2 were obtained from the supernatants of cell lines transfected with the corresponding cDNAs and titrated as described previously.20

Erythroid and myeloid cell precursor potential.

Cells were mixed with OptiMEM, 0.8% methylcellulose (Fluka, Buchs, Switzerland), and 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), supplemented with KL, IL-3, granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (4 ng/mL), and erythropoietin (4 U/mL). Hemoglobinized clusters of fewer than 100 cells were classified as erythroid colony-forming units. Large colonies of red cells (more than 300 cells) were counted as erythroid burst-forming units, whereas colonies containing at least 2 myeloid cell types and erythroid cells were classified as mixed colony-forming units. Numbers of these colonies were counted. Individual colonies were further analyzed by May-Grünwald-Giemsa staining.

In vivo cell transfer

Sorted cells from C57BL/6 (Ly5.1) embryos were injected in the retro-orbital sinus of 400-rad irradiated C57BL/6-Rag2/γc−/− (Ly5.2) mice. After 4 to 6 weeks, cells from the peripheral blood, BM, spleen, thymus, and the small intestine (i-IELs) of the recipient mice were collected and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Purification of NK cells and cytolytic assay

Reconstituted Rag2/γc−/− mice were killed 6 weeks after transfer, and splenocytes were stained with monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) specific for CD3ε and NK1.1. CD3−NK1.1+ NK cells and CD3+NK1.1− T cells were sorted and either tested for their natural cytolytic activity or expanded for 7 days in vitro (105 cells/mL) in complete RPMI medium (RPMI 1640 with 10% FCS, 10−5 M β-mercaptoethanol, 100 mg/mL streptomycin, 100 U/mL penicillin) supplemented with 1000 U recombinant hu–IL-2 (Peprotech). After 7 days, cells were harvested and a standard chromium-release assay was performed. Briefly, YAC-1 (mouse thymoma; H-2a) and P815 (mouse mastocytoma; H-2d) target cells (106) were labeled with 37.105 Bq 51Cr (ICN Pharmaceuticals, Orsay, France) for 45 minutes at 37°C. Cells were extensively washed, plated at 2 × 103 cells/well, and mixed with different numbers of effector cells. Effector cells were NK and T cells either freshly isolated from splenocytes or activated by IL-2. The radioactivity released into the cell-free supernatant was measured after 4 hours at 37°C, and the percentage specific lysis was calculated as follows: 100 × (experimental release − spontaneous release)/(maximum release − spontaneous release).

Reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction

Cells were lysed in TRIzol (GIBCO-BRL, Cergy-Pontoise, France), total RNA was isolated according to the manufacturer's protocol, and cDNA was prepared as described previously.15 Gene-specific primers used for PCR have been described previously. mb-1, RAG-1, λ-5,21 TCF-1,22 Pax-5, GATA-3,7 IL-7Rα,23 universal primer for Ly49, amplifying (Ly49 C, E, F, G1-4),24 pre-TCRα (pTα),15 IL-15Rα: 5′-CCAACATGGCCTCGCCGCAGCT-3′ and 5′-TTGGGAGAGAAAGCTTCTGGCTCT-3′. The amount of cDNA in the samples was carefully standardized by real-time PCR using hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase (HPRT) specific primers: 5′-CCAGCAAGCTTGCAACCTTAACAA-3′, 5′-GACTGAAAGACTTGCTCGAG-3′, and SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Warrington, United Kingdom). Samples were analyzed using a GeneAmp 5700 Sequence Detection System (PE Applied Biosystems). The cDNA samples were amplified for 35 cycles by the GeneAmp PCR System 9600 (Perkin Elmer, Foster City, CA). Fifteen microliters of each PCR product was subjected to electrophoresis through a 2% agarose gel and visualized after ethidium bromide staining.

Immunoscope analysis for the detection of TCRβ rearrangements

DNA was prepared according to the manufacturer's protocol (TRIzol; GIBCO-BRL). For the detection of D-Jβ rearrangements, PCR was performed on the indicated samples using a combination of 2 primers that recognize sequences 5′ of the Dβ2.1 and 3′ of the Jβ2.7.10 The PCR products were then subjected to a runoff reaction using a nested Jβ2.5 fluorescent primer.25 Runoff products were resolved on an automated 373A sequencer (Perkin-Elmer). The size and the intensity of each band were recorded and then analyzed using Immunoscope software.25 26

Results

Characterization of FL cells at 15 days postcoitus based on the expression of B220 and c-kit

The B220 (CD45R) marker is expressed at all stages of B-cell ontogeny. However, it is also expressed in a population of BM cells (fraction A)27,28 endowed with NK potential29and on FL lymphoid progenitors.30 CD19 thus remains the most reliable marker for B-lineage commitment.29 The expression of the receptor tyrosine kinase c-kit correlates with precursor activity and has been used to identify HSCs, CLPs, and pro–T cells.31 FL cells were isolated from 15–days postcoitus (dpc) embryos, and erythroid precursors were depleted using the TER119 mAb. TER119− FL cells were then analyzed for the expression of CD19, c-kit, and B220. The analysis identified 6 distinct populations (Figure1A). The B220+CD19+ population (a) contains pro/pre–B cells that develop in the FL.32 33 The CD19−cells separate into 5 other populations (b-f) according to the level of expression of c-kit and B220. All of the above subpopulations were present at similar ratios in FL cells derived from nude (nu/nu) embryos, showing that they are not generated in the thymus (Figure 1A).

Characterization of 15-dpc FL cells for T-cell progenitor activity: predominance of TCP in the B220lo

c-kit+CD19− fraction. FL cells from 15-dpc C57BL/6 embryos were depleted of erythroid precursors and analyzed for expression of CD19, c-kit, and B220. After flow cytometric sorting of the different subpopulations defined by these 3 markers, wild-type FL cells were tested for TCP activity in an FTOC performed under limiting dilution conditions. (A) Flow cytometric plots are shown for wild-type and nu/nu C57BL/6 FL cells. (B) Reanalysis of sorted cells from populations a and e. Sorted cells were consistently more than 98% pure. (C) The total number of TCPs in 15-dpc FL was previously determined14 and reconfirmed here. From the frequency of TCPs and the fraction that they represent in total FL cells, we calculated the total number of TCPs in each population. The bars show the percentage of the total TCP activity in each fraction. (D) Analysis of surface phenotype of sorted cells from population e after staining with indicated antibodies (solid lines). Data are representative of at least 3 independent experiments.

Characterization of 15-dpc FL cells for T-cell progenitor activity: predominance of TCP in the B220lo

c-kit+CD19− fraction. FL cells from 15-dpc C57BL/6 embryos were depleted of erythroid precursors and analyzed for expression of CD19, c-kit, and B220. After flow cytometric sorting of the different subpopulations defined by these 3 markers, wild-type FL cells were tested for TCP activity in an FTOC performed under limiting dilution conditions. (A) Flow cytometric plots are shown for wild-type and nu/nu C57BL/6 FL cells. (B) Reanalysis of sorted cells from populations a and e. Sorted cells were consistently more than 98% pure. (C) The total number of TCPs in 15-dpc FL was previously determined14 and reconfirmed here. From the frequency of TCPs and the fraction that they represent in total FL cells, we calculated the total number of TCPs in each population. The bars show the percentage of the total TCP activity in each fraction. (D) Analysis of surface phenotype of sorted cells from population e after staining with indicated antibodies (solid lines). Data are representative of at least 3 independent experiments.

The majority of TCPs in the 15-dpc FL are present in fraction e: B220loc-kitsup+CD19−

Unfractionated and sorted cells corresponding to the 6 FL subpopulations (a-f) (Figure 1A) were characterized for their TCP potential by assessing the capacity to reconstitute 14-dpc irradiated thymic lobes.18 Frequencies and total numbers of TCPs were evaluated in FTOCs performed under limiting dilution conditions. Figure1C shows the ratios of TCPs in the different subpopulations (a-f) to TCPs in total FL cells. Strikingly, population e (B220loc-kit+CD19−) represents close to 70% of the TCPs in total FL cells and was thus further characterized. Figure 1D shows surface marker analysis of sorted cells from population e after staining with the indicated antibodies. These precursors were NK1.1−CD90−CD25−CD44+.

In vitro progenitor activity of fraction e

We further evaluated the developmental potential of the cells included in fraction e. Sorted cells were independently analyzed in 3 sensitive in vitro assays supporting T, B, and erythromyeloid differentiation from uncommitted multipotent precursors.34 35

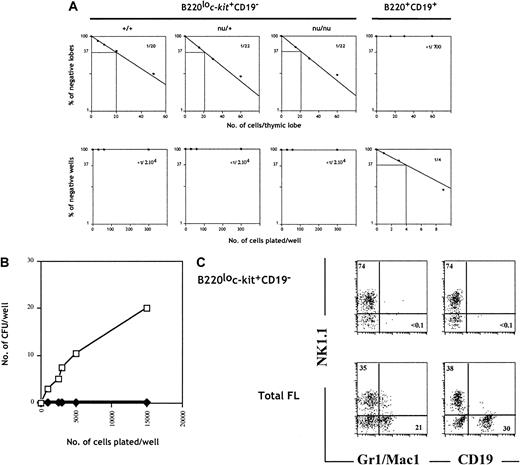

To evaluate the origin of TCPs within fraction e, we cultured sorted cells from wild-type, nu/+, and nu/nuC57BL/6 embryos under limiting dilution conditions in FTOCs. Cells within fraction e generated T cells at a similar frequency (approximately 1 in 20 cells) (Figure2A), whereas fraction a (B220+CD19+), used as negative control, did not generate a detectable T-cell progeny (Figure 2A). This result indicates that the TCPs present in population e are of prethymic origin.

B220lo

c-kit+CD19− progenitors give rise to T and NK cells but fail to generate B and myeloid progeny in vitro. (A) B220+CD19+ (fraction a) FL cells isolated from wild-type embryos and B220loc-kit+CD19− cells (fraction e) isolated from wild-type, nu/+, andnu/nu were set under limiting dilution conditions in FTOC (upper panels) and with S17 stromal cells, KL, and IL-7 (lower panels). Plots of the percentage of negative wells per cell concentration and calculated frequencies are shown. (B) Total FL cells (■) and B220loc-kit+CD19− cells (♦) from wild-type C57BL/6 mice were cultured in methylcellulose, and erythromyeloid colonies were counted on day 7. (C) The same populations as in (B) were cultured on OP9 stromal cells in medium supplemented with IL-7, KL, and IL-2 for B, myeloid, and NK cell development. Cells were stained and analyzed by flow cytometry after 10 days of culture.

B220lo

c-kit+CD19− progenitors give rise to T and NK cells but fail to generate B and myeloid progeny in vitro. (A) B220+CD19+ (fraction a) FL cells isolated from wild-type embryos and B220loc-kit+CD19− cells (fraction e) isolated from wild-type, nu/+, andnu/nu were set under limiting dilution conditions in FTOC (upper panels) and with S17 stromal cells, KL, and IL-7 (lower panels). Plots of the percentage of negative wells per cell concentration and calculated frequencies are shown. (B) Total FL cells (■) and B220loc-kit+CD19− cells (♦) from wild-type C57BL/6 mice were cultured in methylcellulose, and erythromyeloid colonies were counted on day 7. (C) The same populations as in (B) were cultured on OP9 stromal cells in medium supplemented with IL-7, KL, and IL-2 for B, myeloid, and NK cell development. Cells were stained and analyzed by flow cytometry after 10 days of culture.

To evaluate the B-cell differentiation potential, we cultured the same populations under clonal conditions with the stromal cell line S17 in the presence of IL-7 and KL. Sorted cells from fraction a gave rise to B-cell colonies at a frequency of approximately 1 in 4 cells (Figure2A). In contrast, cells from fraction e failed to generate a B-lineage progeny. The absence of B cells in these cultures was confirmed by the absence of IgM-secreting cells after LPS stimulation (data not shown).

The myeloid and erythroid potential of cells from fraction e was addressed by colony formation in methylcellulose. Unfractionated FL cells gave rise to colonies at a frequency of approximately 1 colony-forming unit per 500 plated cells (Figure 2B). Both homogeneous and mixed colonies were identified after May-Grünwald-Giemsa staining of cytospin preparations. Developing colonies included granulocytes and macrophages, and a few colonies also included erythroid cells (data not shown). In contrast, progenitors in fraction e failed to generate colonies in this assay even when up to 15 000 cells were plated (Figure 2B).

An additional characterization of the lymphoid and myeloid differentiation potential was performed in a culture system using the stromal cell line OP912,36 and exogenous interleukins. These conditions permit the development of NK, B, and myeloid cells. Figure 2C shows that both total FL cells and sorted progenitors from fraction e were capable of giving rise to NK cells. Moreover, whereas unfractionated FL cells generated CD19+ B cells and myeloid cells, as indicated by the expression of Gr-1 and Mac-1, precursors in fraction e failed to generate these lineages (Figure 2C), ruling out that this fraction contained the previously identified uncommitted precursors present in FL.7 8

Evidence for a bipotent T/NK progenitor in FL by single-cell analysis

The limiting dilution analysis allowed us to conclude that cells within fraction e contained T and NK precursors, either as a bipotent T/NK or as a mixture of NK and T committed progenitors. To address these possibilities, we investigated the differentiation potential of individual cells in fraction e. Cells were micromanipulated under direct microscopic inspection and allowed to colonize single irradiated fetal thymic lobes. A representative analysis of the cells generated in independent lobes is shown in Figure 3. Expression of T and NK cell markers was examined by gating on Ly5.1+ donor-derived cells. T cells expressing TCRαβ or TCRγδ as well as NK+ cells expressing only NK1.1 were present. NK1.1+TCRαβ cells were also generated.

In vitro generation of T and NK cells from single B220lo

c-kit+CD19− progenitors.Sorted cells were seeded at one cell per well in Terasaki plates. Wells were individually checked under a microscope, and wells containing a single cell were identified. Single cells were then placed in a hanging drop with one irradiated thymic lobe from Ly5 congenic embryos. Flow cytometric analysis of individual lobes was done at day 16 of FTOC.

In vitro generation of T and NK cells from single B220lo

c-kit+CD19− progenitors.Sorted cells were seeded at one cell per well in Terasaki plates. Wells were individually checked under a microscope, and wells containing a single cell were identified. Single cells were then placed in a hanging drop with one irradiated thymic lobe from Ly5 congenic embryos. Flow cytometric analysis of individual lobes was done at day 16 of FTOC.

Under these conditions, the T-cell readout frequency of sorted CD44+CD25+ fetal thymocytes was 1 in 5 cells.15 Using cells from fraction e, we observed thymic reconstitution in 5% (3 of 60) of the individual lobes. Although this efficiency remains low, lobes in which only T or NK cells developed were not observed. Under limiting dilution conditions, where more than one cell from fraction e was used in FTOC, independent NK or T-cell reconstitution was never observed. However, lobes containing only NK progeny were observed when cells from fraction f were seeded in FTOC (data not shown). Together these data indicate that both T and NK potentials in cells from fraction e were present in the same precursor, which we will define as C-TNKP (common T/NK cell progenitor), demonstrating for the first time the existence of such a bipotent cell in FL.

TCRβ chain gene rearrangement and gene expression analysis

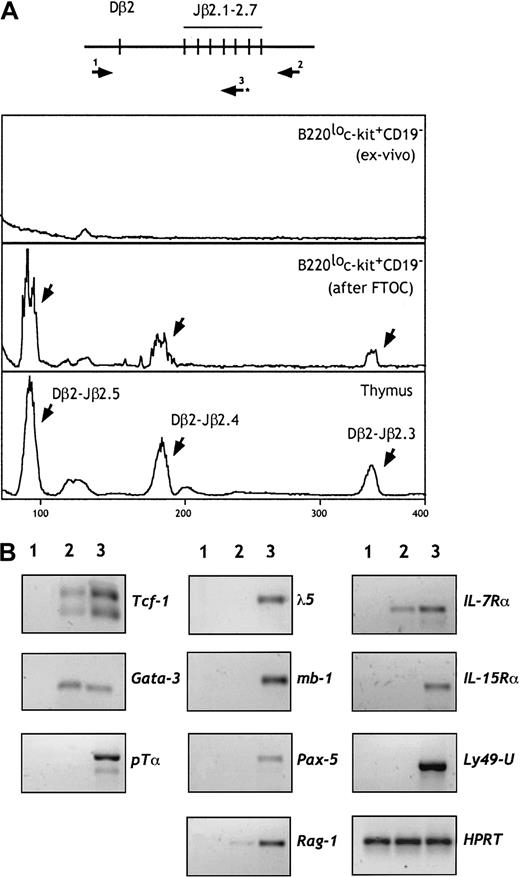

We next investigated whether TCRβ rearrangements have been initiated in these progenitors. DNA was isolated from cells of fraction e before and after FTOC, and rearrangements of the TCRβ genes were examined by PCR. As shown in Figure 4A, D-Jβ rearrangements were not observed in cells from fraction e. In contrast, a diverse pattern of rearrangements was observed when these progenitors were cultured in irradiated fetal thymic lobes. These data suggest that rearrangements in the TCRβ locus occur after thymic seeding and commitment to the T lineage. Recent findings,37 showing that the NK potential is maintained in thymic progenitors until TCRβ gene rearrangements occur, support our conclusion.

B220lo

c-kit+CD19− cells retain their TCRβ locus in a germline configuration but express T-lineage–specific genes. (A) DNA was prepared from 5 × 103 cells from fraction e before and after FTOC. Rearrangement of the TCRβ genes was examined by a sensitive 2-step PCR using pairs of primers (1 and 2) followed by a runoff using the fluorescent primer 3, as shown in the higher panel. TCRβ gene rearrangement was not observed in cells from fraction e. In contrast, diverse Dβ-Jβ rearrangements (indicated by arrows) were observed after FTOC. (B) RT-PCR analysis of cells from population e (line 2) for the indicated genes. Controls (line 3) included 15-dpc fetal thymocytes, CD19+B220+ cells, and NK1.1+CD3− mature NK cells. S17 cells were used as a negative control (line 1). The amount of cDNA was carefully standardized according to HPRT transcripts.

B220lo

c-kit+CD19− cells retain their TCRβ locus in a germline configuration but express T-lineage–specific genes. (A) DNA was prepared from 5 × 103 cells from fraction e before and after FTOC. Rearrangement of the TCRβ genes was examined by a sensitive 2-step PCR using pairs of primers (1 and 2) followed by a runoff using the fluorescent primer 3, as shown in the higher panel. TCRβ gene rearrangement was not observed in cells from fraction e. In contrast, diverse Dβ-Jβ rearrangements (indicated by arrows) were observed after FTOC. (B) RT-PCR analysis of cells from population e (line 2) for the indicated genes. Controls (line 3) included 15-dpc fetal thymocytes, CD19+B220+ cells, and NK1.1+CD3− mature NK cells. S17 cells were used as a negative control (line 1). The amount of cDNA was carefully standardized according to HPRT transcripts.

We analyzed by reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) the expression of genes that play a role in early B, T, or NK cell differentiation. As shown in Figure 4B, sorted cells from fraction e failed to express B-lineage–specific genes (λ-5, mb-1, and Pax-5). They expressed IL-7Rα and, at barely detectable levels, RAG-1 transcripts. Interestingly, these progenitors expressed the T-lineage–specific transcription factor GATA-3 and low levels of TCF-1. Expression of the pTα gene was not detected under the same PCR conditions. We also did not detect expression of genes associated with NK lineage differentiation, such as IL-15Rα and Ly49. Expression of both T- and NK-related genes has been observed in the NK1.1+CD90+ pT/NK progenitors derived from the fetal thymus, blood, and spleen, suggesting that these may represent a more mature stage of differentiation.12 38

B220loc-kit+CD19−FL progenitors reconstitute both the T and NK, but neither the B-cell nor the myeloid, compartments of Rag2/γc−/−mice

To assess the hematopoietic reconstitution potential in vivo of cells in fraction e, we intravenously injected sorted B220loc-kit+CD19− cells into sublethally irradiated mice carrying mutations in both the Rag2 and the common cytokine receptor γc genes.39 The additional absence of NK cells in the Rag2/γc−/− mice40 (Figure5A) compared with Rag2−/− mice makes them ideal hosts to analyze the potential to generate B, T, and NK cells. Rag2/γc−/−mice were intravenously injected with 7 × 104TER119− FL cells or 104 cells from fraction e, both numbers corresponding to 500 TCPs in the respective populations.

In vivo progenitor activity of B220lo

c-kit+CD19− FL cells.Total 15-dpc FL cells and sorted B220loc-kit+CD19− cells (fraction e) were injected into irradiated C57BL/6-Rag2/γc−/− mice at 7 × 104 and 104 cells per mouse, respectively, corresponding to an equivalent number of 500 TCPs. Four weeks after cell transfer, the blood (A), thymus (B), BM (C), and i-IELs (D) were analyzed by flow cytometry. The presence of donor-derived cells was assessed by gating on Ly5.1+ cells. Numbers indicate the relative percentage within the indicated gates. The results are representative of 4 experiments.

In vivo progenitor activity of B220lo

c-kit+CD19− FL cells.Total 15-dpc FL cells and sorted B220loc-kit+CD19− cells (fraction e) were injected into irradiated C57BL/6-Rag2/γc−/− mice at 7 × 104 and 104 cells per mouse, respectively, corresponding to an equivalent number of 500 TCPs. Four weeks after cell transfer, the blood (A), thymus (B), BM (C), and i-IELs (D) were analyzed by flow cytometry. The presence of donor-derived cells was assessed by gating on Ly5.1+ cells. Numbers indicate the relative percentage within the indicated gates. The results are representative of 4 experiments.

The analysis of blood samples from mice injected with total FL cells revealed the presence of TCRαβ+ mature T cells, NK1.1+IL2Rβ+ NK cells, and also B220+IgD+ mature B cells 4 to 6 weeks after cell transfer. In contrast, sorted cells from fraction e, although capable of generating T and NK cells, lacked any detectable B-cell reconstitution potential (Figure 5A). The main hematopoietic sites (BM and thymus) of the recipient mice were analyzed at 4 weeks after transfer for the presence of donor-derived myeloid, B, T, and NK cells. Mice having transplantation with either unfractionated FL cells or sorted cells from fraction e contained T cells in the thymus (Figure5B). At this time point, most progeny derived from fraction e had already progressed to the mature CD4+ or CD8+simple positive stage, and consistently 70% of these thymocytes expressed high levels of TCRαβ. The majority (76%) of the progeny of unfractionated FL cells were at the double positive stage, and only 30% were TCRαβ+. Mice injected with total FL cells showed sustained T-cell lymphopoiesis 8 weeks after injection. In contrast, in recipients of cells from fraction e, T-cell generation was no longer observed (data not shown). These data suggest that progenitors included in fraction e have a limited self-renewal potential and are able to generate only a transient wave of T-cell reconstitution.

The analysis of BM cells showed a striking difference in the B and myeloid repopulation capacity of the 2 sets of reconstituted mice (Figure 5C). In support of the in vitro data, fraction e was devoid of B and myeloid cell precursor activity, as shown by the total absence of B220+IgD+ and Gr-1+ cells, which were generated only from unfractionated 15-dpc FL (Figure 5C). It is interesting to note that a minor B220lo population was detected in mice reconstituted with fraction e; those donor-derived cells were shown to be B220loIgD−NK1.1+.

To exclude the possibility that an early transient wave of B-cell repopulation was generated in the mice receiving B220loc-kit+CD19−transplants, we analyzed the peripheral blood within 2 weeks after cell transfer. Mice reconstituted with unfractionated FL cells contained significant levels of donor-derived B220+IgD+cells in the peripheral blood. In contrast, mice having transplantation with fraction e showed no repopulation in the peripheral blood at this time point (data not shown).

Evidence for the existence of T cells of extrathymic origin within the intestinal epithelium41 led us to ascertain whether the progenitors in fraction e could contain precursors for this T-cell subset. Rag2/γc−/− mice reconstituted with progenitors from fraction e contained αβ and γδ T cells in the i-IEL compartment (Figure 5D). TCRαβ+ cells expressing the CD8αα homodimer, characteristic of extrathymic i-IELs, were also present in these mice.

Population e generates cytolytic NK cells in vivo

The spleens of mice reconstituted with population e contained a subset of cells phenotypically indistinguishable from mature NK cells that we tested for their cytolytic activity. Splenic NK1.1+CD3− but not CD3+NK1.1− cells generated in vivo from population e exhibited low but detectable levels of cytolysis against YAC-1 cells (Figure 6A). IL-2–activated CD3−NK1.1+ cells showed strong cytolytic activity against NK-sensitive YAC-1 thymoma cells (Figure 6A) but not against NK-resistant P815 mastocytoma cells (Figure 6B). The cytolytic activity of NK cells generated in vivo from population e was comparable to that displayed by NK cells isolated from control B6 mice (Figure6B). These data demonstrate that the B220loc-kit+CD19−subpopulation can give rise to functional NK cells in vivo.

Cytolytic activity of NK cells generated in vivo.

CD3−NK1.1+ NK cells (circles) and CD3+NK1.1− T cells (triangles) were purified from splenocytes of mice reconstituted with population e. (A) Freshly sorted cells were tested for cytolytic activity versus YAC-1 thymoma targets. (B) Sorted NK cells (circles) and T cells (triangles) from mice reconstituted with population e (empty symbols) and control B6 mice (filled symbols) were cultured in vitro for 7 days in IL-2 and thereafter tested for cytolytic activity versus sensitive YAC-1 and resistant P815 target cells.

Cytolytic activity of NK cells generated in vivo.

CD3−NK1.1+ NK cells (circles) and CD3+NK1.1− T cells (triangles) were purified from splenocytes of mice reconstituted with population e. (A) Freshly sorted cells were tested for cytolytic activity versus YAC-1 thymoma targets. (B) Sorted NK cells (circles) and T cells (triangles) from mice reconstituted with population e (empty symbols) and control B6 mice (filled symbols) were cultured in vitro for 7 days in IL-2 and thereafter tested for cytolytic activity versus sensitive YAC-1 and resistant P815 target cells.

Discussion

We have quantitatively characterized TCPs in different subsets of FL cells. This analysis allowed us to isolate a novel population of hematopoietic progenitors that represent the majority (70%) of TCPs in 15-dpc FL. Cells within this population lack in vitro and in vivo potential for B and erythromyeloid differentiation. These precursors were shown to differentiate into T and NK cells by single-cell fate analysis. Moreover, precursors uniquely committed to either the T or NK lineage were not detected in single-cell or limiting dilution assays, arguing for the absence of more restricted progenitors among this subset. This conclusion is supported by recent studies indicating that T-lineage restriction from a bipotent p-T/NK occurs in the thymus.11 37 Consistent with this notion, the cell population described here is of prethymic origin. We designate this cell population as common T/NK progenitor (C-TNKP).

We show that the frequency of T-cell generation in vitro in FL-derived C-TNKP cells is approximately 1 in 20 cells. It should be noted that a pure population of TCPs (ie, CD44+CD25+prothymocytes) has a plating efficiency of 1 in 5 cells in this assay. This result indicates that not all cells in FTOC conditions colonize the thymic lobes, and furthermore not all cells will efficiently interact with the thymic stroma to initiate the T-cell differentiation program. Thus, the true frequency of TCPs in the population we describe could be much higher. It should also be pointed out that the frequency of T-cell generation obtained here is comparable to that obtained for CLPs from BM (1:21).5 The cloning efficiency for B-cell precursor detection in vitro is comparable to that found for T cells in FTOCs. Thus, 1 in 4 CD19+ FL cells can generate B-cell colonies in the presence of stromal cells, KL, and IL-7. The fact that we are comparing potentials of differentiation using tests with similar plating efficiencies reinforces our conclusion that B-cell differentiation potential is not retained in B220loc-kit+CD19−FL precursors.

When injected into Rag2/γc−/− mice, FL-derived B220loc-kit+CD19− cells were shown to be effective in the repopulation of the T and NK cell compartment of Rag2/γc-deficient mice, further confirming the restricted differentiation potential of these progenitors assessed in vitro. The limited self-renewal potential of these precursors is shown by a skewed ratio of CD4/CD8 single- to double-positive cells 4 weeks after transfer and by the virtual absence of thymocytes 4 weeks later. The transient reconstitution observed contrasts with a sustained thymopoiesis obtained with total FL cells known to harbor HSCs. Thus, the self-renewing progenitors in the BM that ensure constant generation of TCPs are most likely the stem cells because the common lymphoid precursors (CLPs), the immediate precursors of the C-TNKP, were also shown to have transient reconstitution capacity.5Although the BM of mice reconstituted with fraction e from FL showed no signs of differentiation of B or myeloid cells, a minor population of B220loNK1.1+ donor-derived cells was detected. They most likely correspond to mature NK cells known to express low levels of B220 that differentiated in situ.42

The analysis of i-IELs of the reconstituted mice showed the presence of donor-derived cells that reconstituted this particular environment with ratios of γδ- and αβ-expressing T cells comparable to those found in normal mice. Moreover, TCRαβ and γδ cells expressing the homodimer CD8αα were also generated. Both populations have been shown to undergo extrathymic differentiation.41 We conclude that FL-derived C-TNKPs are able to reconstitute not only the thymic but also the extrathymic T-cell compartments. Precursors for i-IELs have been described in a specialized structure named cryptopatches.43 In addition, putative IEL precursors have been reported to express low levels of B220.44 45 The similarity between this phenotype and that expressed in the population described here raises the possibility of a lineage relationship between these subsets. However, further investigations are required to formally assess this possibility.

Although sharing the common capacity to differentiate into both T and NK cells, the population described here expressed a different set of surface markers compared with the p-T/NK previously identified in the fetal thymus, blood, and spleen but absent from FL, the major hematopoietic organ during embryonic life.12 These were shown to be NK1.1+, CD117lo, and CD90+; in contrast, the FL C-TNKPs described here are NK1.1−, CD117high, and CD90−.

Gene expression analysis revealed additional differences between these populations. NK1.1+CD90+CD117loprecursors expressed the T-cell–specific transcript pTα and genes associated with NK lineage differentiation such as IL-15Rα and NKR-P1 family members. In contrast, the population described here has undetectable levels of pTα and IL-15Rα transcripts. However, 2 transcription factors associated with T-cell development (GATA-3 and TCF-1) were expressed in both populations. All together, this suggests that C-TNKP in FL represents a more immature population than NK1.1+CD90+CD117lo precursors. On the other hand, GATA-3 is expressed at low levels in common lymphoid progenitors (CLPs) while it is up-regulated in thymic pro-T cells. In conclusion, the C-TNKP can be placed in an intermediate developmental stage between the CLP and the p-T/NK identified in fetal blood and thymus (Figure 7).

Model for prethymic T and NK lineage commitment.

The molecular characterization and the analysis of the potential of differentiation of FL-derived B220loc-kit+CD19−progenitors place this population (C-TNKP) in an intermediate developmental stage between the CLP and the p-T/NK identified in fetal blood and thymus (see “Discussion” for further details).

Model for prethymic T and NK lineage commitment.

The molecular characterization and the analysis of the potential of differentiation of FL-derived B220loc-kit+CD19−progenitors place this population (C-TNKP) in an intermediate developmental stage between the CLP and the p-T/NK identified in fetal blood and thymus (see “Discussion” for further details).

A continuous flow of immigrants seems necessary to ensure a constant T-cell generation in the thymus.46 It is conceivable that multiple cell types such as HSCs, CLPs, and p-T/NK are involved in this process. Our own previous results showed that the fetal thymus is seeded by increasing numbers of TCPs.15 The quantitative data presented here indicate the following: (1) During mid-gestation, the major population of FL cells endowed with T-cell differentiation potential are committed to the T/NK lineage; (2) this population can reconstitute both the conventional thymic and the extrathymic T-cell subsets; and (3) both by surface marker and gene expression pattern, they differ from previously described thymic and blood-derived pT/NK cells. We propose that if constant thymic immigration occurs, the population described here likely constitutes a major component of this process.

The isolation of a homogeneous population of prethymic bipotent T/NK precursors will allow the identification of genes involved in early stages of T-cell commitment and differentiation and eventually will allow us to understand the molecular basis for thymic immigration. Moreover, the capacity of a human counterpart of this cell population to reconstitute efficiently the T-cell compartment could be used to prevent lymphopenia following stem cell transplantation and could therefore be of high therapeutic interest.

We thank Mathias Haury, Anne Louise for cell sorting, Pablo Pereira for advice in the i-IEL preparations, and Laurent Boucontet for help with real-time PCR analysis.

The Unité du Développement des Lymphocytes is supported by grants from the ANRS and “Ligue Nationale Contre le Cancer” as a registered laboratory. I.D. is supported by a fellowship from the Ligue Nationale Contre le Cancer.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Iyadh Douagi, Unité du Développement des Lymphocytes, Département d'Immunologie, Institut Pasteur, 25 rue du Dr Roux, 75724 Paris, Cedex 15, France; e-mail: idouagi@pasteur.fr.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal