Key Points

We performed targeted sequencing and copy-number analysis of serial samples from 25 patients with late relapse after allogeneic HCT.

Matched HLA loss provided genetic evidence for leukemic escape from tumor-associated/minor histocompatibility antigen allorecognition.

Abstract

Immune evasion is a hallmark of cancer and a central mechanism underlying acquired resistance to immune therapy. In allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (alloHCT), late relapses can arise after prolonged alloreactive T-cell control, but the molecular mechanisms of immune escape remain unclear. To identify mechanisms of immune evasion, we performed a genetic analysis of serial samples from 25 patients with myeloid malignancies who relapsed ≥1 year after alloHCT. Using targeted sequencing and microarray analysis to determine HLA allele-specific copy number, we identified copy-neutral loss of heterozygosity events and focal deletions spanning class 1 HLA genes in 2 of 12 recipients of matched unrelated-donor HCT and in 1 of 4 recipients of mismatched unrelated-donor HCT. Relapsed clones, although highly related to their antecedent pretransplantation malignancies, frequently acquired additional mutations in transcription factors and mitogenic signaling genes. Previously, the study of relapse after haploidentical HCT established the paradigm of immune evasion via loss of mismatched HLA. Here, in the context of matched unrelated-donor HCT, HLA loss provides genetic evidence that allogeneic immune recognition may be mediated by minor histocompatibility antigens and suggests opportunities for novel immunologic approaches for relapse prevention.

Introduction

The curative effect of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (alloHCT) in patients with myeloid malignancies is dependent on development of durable graft-versus-leukemia (GVL) activity. GVL activity is mediated by allogeneic T and natural killer (NK) cells and can control or eradicate leukemias that would inevitably relapse after chemotherapy alone. However, even patients who experience a period of sustained remission after transplantation have a continued risk of relapse. These late relapses suggest that acquired immune evasion may be a route to transplantation resistance, but the molecular mechanisms and extent to which leukemic escape drives relapse are unclear.

After HCT from a haploidentical related donor sharing 1 of 2 HLA haplotypes, mismatched HLAs are immunodominant targets of alloreactivity whose selective loss can drive GVL evasion and acute myeloid leukemia (AML) relapse.1 However, T-cell allorecognition after HLA-matched HCT targets leukemia-associated antigens such as recipient-specific minor histocompatibility antigens, which are processed and presented in the context of HLA proteins. Minor histocompatibility antigen mismatching has been associated with augmented GVL effect and increased risk of graft-versus-host disease,1,2 raising the possibility that some leukemias may evade GVL effect by impairing presentation of these antigens. Alternatively, leukemic cells may escape GVL selection by acquiring immunoregulatory properties or losing sensitivity to immune cell cytotoxicity, potential mechanisms suggested by genetic alterations in diverse tumors under immune selection.3-7 Indeed, in acquired aplastic anemia, HLA loss and a unique spectrum of somatic mutations define clonal hematopoiesis emerging from autoimmune selection.8,9

Therefore, to identify mechanisms of immune escape after alloHCT, we evaluated genetic characteristics of patients with myeloid malignancies treated with alloHCT who relapsed at least 1 year after transplantation.

Methods

Patient cohort

A total of 1642 adult patients with myeloid malignancies who underwent alloHCT at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute/Brigham and Women’s Hospital (2001-2015) were considered for inclusion in this study. Six hundred five patients (37%) relapsed after transplantation, and 92 of these relapses (15%) occurred at least 1 year after transplantation. Banked specimens from all 3 study time points were available for the 25 patients included in this study. Clinical information is presented in supplemental Table 1. The study was conducted with the approval of the institutional review board at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.

Genetic analysis

We selected 187 genes for targeted sequencing based on their recurrent alteration in myeloid malignancies10 or suspected involvement in cancer immune evasion (supplemental Table 2). We included 2281 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) for copy-number variation and chimerism analysis. DNA library preparation, custom target capture (Agilent SureSelect), paired-end 2 × 100 base-pair sequencing (Illumina HiSeq2500 or HiSeq3000), and data processing were performed as previously described,11 using genome assembly GRCh37 (hg19). The average mean target coverage was 375×. Mutations were identified using MuTect v1.1.4 and SomaticIndelDetector.12,13 Optitype 1.3.1 was used for class 1 HLA typing and somatic mutation analysis.14 Candidate driver mutations in genes implicated in AML and myelodysplastic syndrome were classified using gene-specific criteria10 (supplemental Table 3). Relapse-specific mutations were identified by comparison of serial samples. Comparative genome hybridization plus SNP microarrays (SurePrint G3 2×400K Human Genome or 4×180K Cancer; Agilent) were performed on paired pre- and posttransplantation tumor samples and analyzed using Agilent Cytogenomics 4.0.3.12 software. 11 HLA locus genotyping was performed using the long-range polymerase chain reaction TruSight HLA v2 Sequencing Panel (Illumina; HLA-A, -B, -DRB1/3/4/5, -DQA1, -DQB1, -DPA1, and -DPB1). Paired-end 2 × 150 base-pair sequencing was performed (Illumina MiSeq), and data analysis was performed using TruSight HLA Assign 2.1 software. DNA sequencing has been deposited into the Sequence Read Archive (accession PRJNA521319).

Results and discussion

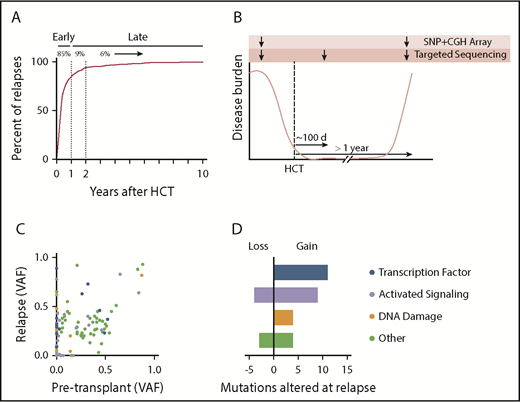

We evaluated the time to relapse for adult patients with myeloid malignancies who underwent alloHCT between 2001 and 2015 at our institution (Figure 1A). Eighty-five percent of all relapses occurred within the first year after transplantation, suggesting that most relapses occur without establishment of sustained antileukemia immunity. To investigate acquired genetic mechanisms of immune evasion after initial achievement of immunonologic equilibrium, we studied patients who relapsed after at least 1 year of clinical remission. For 25 patients, we generated targeted sequencing data from each of 3 time points: (1) before transplantation, with AML or myelodysplastic syndrome involvement; (2) ∼100 days after transplantation, during the period of remission; and (3) at the time of disease relapse (Figure 1B). These patients had received matched related-donor (n = 9), matched unrelated-donor (MUD; n = 12), or mismatched unrelated-donor (MMUD; n = 4) alloHCT.

Late relapse study design and driver mutation analysis. (A) Time to relapse (in years) after alloHCT for AML, myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), or myeloproliferative disease between 2001 and 2015 at our institution. (B) Schematic of trio targeted sequencing and microarray analysis for 25 patients. (C) Scatter plot showing variant allele frequency (VAF) at time of paired pretransplantation and relapse samples. (D) Alterations in myeloid driver mutations at relapse. Mutations were categorized as lost if they were present at ≥0.02 VAF pretransplantation and absent or <0.02 VAF at relapse. Similarly, mutations were categorized as gained if they were absent or <0.02 VAF pretransplantation and present at ≥0.02 VAF at relapse. CGH, comparative genome hybridization.

Late relapse study design and driver mutation analysis. (A) Time to relapse (in years) after alloHCT for AML, myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), or myeloproliferative disease between 2001 and 2015 at our institution. (B) Schematic of trio targeted sequencing and microarray analysis for 25 patients. (C) Scatter plot showing variant allele frequency (VAF) at time of paired pretransplantation and relapse samples. (D) Alterations in myeloid driver mutations at relapse. Mutations were categorized as lost if they were present at ≥0.02 VAF pretransplantation and absent or <0.02 VAF at relapse. Similarly, mutations were categorized as gained if they were absent or <0.02 VAF pretransplantation and present at ≥0.02 VAF at relapse. CGH, comparative genome hybridization.

We compared the spectrum of myeloid driver mutations present in leukemic samples obtained before and after transplantation; 24 of 25 cases retained at least 1 recurrent genetic alteration, confirming the typical clonal relationship between pre- and posttransplantation disease. Relapse-specific gain and/or loss of mutations was identified in 19 cases. A majority of the relapse-specific mutations affected genes encoding signaling proteins (n = 9; 32%) and transcription factors (n = 11; 39%; Figure 1C-D), consistent with patterns of leukemogenic progression in myeloid malignancies,15-17 and were therefore difficult to attribute to transplantation-specific selective pressure. Point mutations and structural variants affecting TP53 were more frequent at relapse (n = 7) than pretransplantation (n = 2; supplemental Figure 1), which may reflect positive selection by cytotoxic therapy, transplantation conditioning, and/or GVL effect.

Immune evasion after transplantation could occur via acquisition of mutations that alter key immunoregulatory pathways. Therefore, we sequenced 88 genes previously implicated in cancer immune evasion, including genes related to extrinsic apoptosis,3 antigen-processing machinery,5 T/NK-cell adhesion and activation,4,18 and oncogenic signaling pathways associated with resistance to immunotherapy6,19 (supplemental Table 2). We did not identify recurrent relapse-specific mutations, suggesting that mutations in these core pathways are not common contributors to relapse.

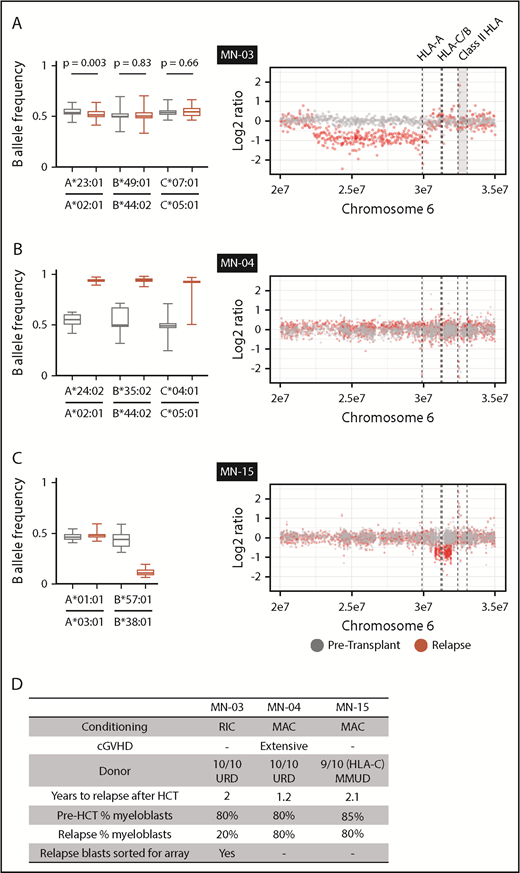

We next evaluated sample trios from each recipient for relapse-specific alterations in HLA. We did not identify any single-nucleotide or short insertion/deletion mutations affecting HLA-A, HLA-B, HLA-C, or B2M. To evaluate for evidence of structural variation at class 1 HLA loci, we first used Optitype HLA typing of pretransplantation and day-100 remission samples to define donor and recipient HLA alleles (supplemental Table 4). Next, we estimated class 1 HLA allele-specific copy number across serial samples using the tool LOHHLA.20 For class 2 and mismatched class 1 HLA alleles not amenable to use of the LOHHLA algorithm, we used comparative genome hybridization plus SNP microarrays. In total, we identified 2 HLA losses among 12 relapses after MUD HCT and 1 additional HLA loss among 4 relapses after MMUD HCT (Figure 2). Two HLA loss events were focal deletions spanning a subset of class 1 HLA alleles (Figure 2A,C), whereas 1 was a copy-neutral loss of heterozygosity event spanning the entire HLA locus (Figure 2B; supplemental Figure 2). In the latter case, we used amplicon sequencing–based HLA typing to confirm that the lost haplotype was fully matched for class 1 and 2 alleles (HLA-A, -B, -C, -DPA1, -DPB1, -DQA1, -DQB1, -DRB1, and -DRB3; supplemental Table 4). HLA loss was not associated with concurrent TP53 alterations or increased copy-number instability (supplemental Figure 3). The 3 HLA loss relapses occurred 1.2 to 2.1 years after alloHCT for AML; chronic graft-versus-host disease was present in only 1 case (Figure 2D). The patient- and disease-related characteristics and clinical outcomes in patients with HLA loss were otherwise similar to those in the total cohort.

HLA loss at posttransplantation relapse. (A-C) B allele frequency of mismatched SNPs for each matched class 1 HLA gene in pretransplantation (gray) or relapse (red) specimens (left) and copy-number analysis of chromosome 6p (right). (A) The relapse specimen with 20% myeloblast percentage harbors a subtle allelic imbalance of HLA-A (left). Analysis of sorted myeloblasts confirms loss of HLA-A in the relapsed leukemic cells (right). (B) The relapse specimen harbors allelic imbalance of all class 1 HLA genes as a result of copy-neutral loss of heterozygosity across chromosome 6p (right; supplemental Figure 2). (C) The relapse specimen harbors allelic imbalance of HLA-B, which was the result of a 1-Mb deletion spanning HLA-B and HLA-C. (D) Clinical and sample characteristics for cases with relapse-specific HLA loss. cGVHD, chronic graft-versus-host disease; MAC, myeloablative conditioning; RIC, reduced-intensity conditioning; URD, unrelated donor.

HLA loss at posttransplantation relapse. (A-C) B allele frequency of mismatched SNPs for each matched class 1 HLA gene in pretransplantation (gray) or relapse (red) specimens (left) and copy-number analysis of chromosome 6p (right). (A) The relapse specimen with 20% myeloblast percentage harbors a subtle allelic imbalance of HLA-A (left). Analysis of sorted myeloblasts confirms loss of HLA-A in the relapsed leukemic cells (right). (B) The relapse specimen harbors allelic imbalance of all class 1 HLA genes as a result of copy-neutral loss of heterozygosity across chromosome 6p (right; supplemental Figure 2). (C) The relapse specimen harbors allelic imbalance of HLA-B, which was the result of a 1-Mb deletion spanning HLA-B and HLA-C. (D) Clinical and sample characteristics for cases with relapse-specific HLA loss. cGVHD, chronic graft-versus-host disease; MAC, myeloablative conditioning; RIC, reduced-intensity conditioning; URD, unrelated donor.

These genetic findings suggest that matched HLA loss may contribute to leukemic escape after alloHCT. HLA loss resulting from copy-neutral loss of heterozygosity has been reported in AML without transplantation, but it is a rare event.21 Although our study does not include a nontransplantation control cohort, the rate of somatic HLA loss in our cohort (12%) is higher than that in nontransplantation AML cohorts (0.2%-1%) assessed by array comparative genomic hybridization22,23 or comprehensive genomic profiling.24 Consistent with the model of immune selection–specific loss, relapses with HLA loss were seen only after MMUD and MUD HCT, not after matched related-donor HCT, which typically have fewer genomic differences between donor and recipient.25 Finally, HLA loss did not cooccur with TP53 loss or elevated copy-number variation, arguing against the possibility that HLA loss is a bystander of underlying genome instability. Although loss of mismatched HLA has been reported,26,27 and transcriptional downregulation of class 2 HLA may contribute to leukemic escape,28-30 genetic HLA loss at relapse after matched alloHCT has only been published in a single case report of extramedullary relapse31 and has not been seen in several other studies.28,32-34 Our findings suggest that loss of even a single matched HLA allele could irreversibly impair the presentation of ≥1 leukemia-associated or minor histocompatibility antigens, contributing to leukemic escape.

In cases with late relapse, HLA loss indicates a prolonged period of immunologic equilibrium, where GVL effect serves as a selective pressure for clonal genetic mechanisms of alloimmune evasion. Most late relapses acquired transcription factor, activated signaling, and/or TP53 mutations, whereas a minority demonstrated HLA loss. Identification of patients with relapsed leukemia harboring irreversible genetic HLA loss may prove clinically relevant and distinct from transcriptional downregulation of HLA.28,35 Efforts to augment GVL effect such as donor lymphocyte infusion might be ineffective if leukemic cells are no longer capable of presenting key alloantigens. Such patients might be logical candidates for NK-cell therapy or second transplantation informed by the remaining leukemic HLA repertoire.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank members of the B.L.E. laboratory for helpful discussions and feedback and the Ted and Eileen Pasquarello Tissue Bank in Hematologic Malignancies for provision of samples.

This work was supported by grant R01HL082945 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, and grants P01CA066996 and P50CA206963 from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health. B.L.E. is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Authorship

Contribution: M.J., R.C.L., and B.L.E. designed the study, reviewed the analysis, and wrote the manuscript; M.J. and M.J.L. analyzed the sequencing data, curated variants, and performed bioinformatics analysis; E.A.M., J.C.W., J.B., and V.T.H. curated clinical data; A.N., S.D.D., B.M.W., M.D.D., and A.R.T. generated sequence data and developed variant calling algorithms and sequence data processing pipelines; S.L. generated microarray data; J.S. and W.J.L. performed and analyzed HLA typing by amplicon sequencing; N.K., V.T.H., J.K., C.S.C., S.N., E.P.A., J.H.A., R.J.S., and J.R. diagnosed patients and prepared samples; and all authors reviewed the manuscript during its preparation.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: J.R. reports research funding from Equillium and Kite Pharma and consulting income from Aleta Biotherapeutics, Avrobio, Celgene, Draper Labs, LifeVault Bio, and TScan Therapeutics. R.J.S. reports participation in the data and safety monitoring board of Juno/Celgene and the board of directors of Kiadis and National Marrow Donor Program/Be The Match and consulting income from Gilead, Merck, and Astellas. J.K. reports consulting income from Amgen, Fortress Biotech, Cugene, and Equilium and research support from Miltenyi Biotec GmbH, Prometheus Labs, and Bristol-Myers Squibb. A.R.T. reports consulting income from AlphaSights. R.C.L. reports consulting income from Takeda and research support from Jazz and MedImmune. B.L.E. reports funding from Celgene and Deerfield. W.J.L. reports income and participation on the scientific advisory board of CareDx. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Benjamin L. Ebert, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, 450 Brookline Ave, D1610A, Boston, MA 02215; e-mail: benjamin_ebert@dfci.harvard.edu; and R. Coleman Lindsley, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, 450 Brookline Ave, Dana 530C, Boston, MA 02115; e-mail: coleman_lindsley@dfci.harvard.edu.