Key Points

Acquisition of TP53 mutations is a key event for transformation of chronic myeloproliferative neoplasms to acute leukemia.

We showed that MDM2 inhibition can directly favor the emergence of TP53-mutated subclones and propose an assay that may predict such events.

Abstract

The mechanisms of transformation of chronic myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPN) to leukemia are largely unknown, but TP53 mutations acquisition is considered a key event in this process. p53 is a main tumor suppressor, but mutations in this protein per se do not confer a proliferative advantage to the cells, and a selection process is needed for the expansion of mutant clones. MDM2 inhibitors may rescue normal p53 from degradation and have been evaluated in a variety of cancers with promising results. However, the impact of these drugs on TP53-mutated cells is underexplored. We report herein evidence of a direct effect of MDM2 inhibition on the selection of MPN patients’ cells harboring TP53 mutations. To decipher whether these mutations can arise in a specific molecular context, we used a DNA single-cell approach to determine the clonal architecture of TP53-mutated cells. We observed that TP53 mutations are late events in MPN, mainly occurring in the driver clone, whereas clonal evolution frequently consists of sequential branching instead of linear consecutive acquisition of mutations in the same clone. At the single-cell level, the presence of additional mutations does not influence the selection of TP53 mutant cells by MDM2 inhibitor treatment. Also, we describe an in vitro test allowing to predict the emergence of TP53 mutated clones. Altogether, this is the first demonstration that a drug treatment can directly favor the emergence of TP53-mutated subclones in MPN.

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) can occur as secondary events following cancer therapy for solid tumors and are then considered as therapy-related AML. The causative role of anticancer treatment has been well established for topoisomerase II inhibitors like etoposide or mitoxantrone in the occurrence of balanced translocations like t(15;17) and acute promyelocytic leukemia development1,2 but also at the 11q23 locus in the MLL gene.3,4 In these particular cases the drugs are directly responsible for the acquisition of molecular alterations leading to the rapid development of therapy-related AML. On the other hand, secondary AML (s-AML) may develop after several years of evolution with various myeloid neoplasms, but key determinants of transformation are poorly understood. In this regard, BCR-ABL1− myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) represent an exquisite model to study. Indeed, MPNs present a chronic phase inconstantly followed by evolution to more aggressive diseases like myelofibrosis or s-AML. During the chronic phase, the majority of MPN patients receive antiproliferative drugs aiming at reducing thrombo-hemorrhagic complications, and such treatments are usually maintained for years. A proleukemogenic role of these treatments, as opposed to spontaneous evolution, has been suspected from clinical studies,5 but definitive demonstration is lacking. The correlation of previous treatments with the development of s-AML is frequently suggested, but providing direct evidence between drug exposure and occurrence of oncogenic molecular alterations is difficult. Indeed, in these cases, the transformation is rarely due to the occurrence of a strong phenotype-driving oncogene like promyelocytic leukemia/retinoic acid receptor alpha in acute promyelocytic leukemia but more frequently to the acquisition of several mutations or chromosomal abnormalities that cooperate to ultimately induce acute transformation. Thus, identifying therapy-related events involved in the secondary leukemic transformation of chronic myeloid neoplasms is challenging.

The phenotype of MPNs is driven by acquired genetic lesions in hematopoietic stem cells, including mutations in the JAK2 (JAK2V617F and exon 12), CALR, and MPL genes. The heterogeneity of MPN clinical evolution has been attributed to the acquisition of various additional mutations during the course of the disease that have been reported to impact the clinical outcome.6-9 It is now suspected that transition from chronic MPN to AML is a process during which additional mutations are acquired, and clones with increasing leukemogenic potential are selected. It is acknowledged that cancer development follows Darwinian principles,10 and clonal selection is driven by forces from the microenvironmental context.11 The mechanisms of clonal selection are still elusive, but several actors may play a role, like cell metabolism, competition for nutriments, clone to clone interactions, cellular microenvironment, and soluble factors like secreted cytokines but also exogenous drugs.

Acquired mutations in TP53 leading to inactive forms of the protein are among the most frequent mutations in all types of cancer. Indeed, the p53 protein is considered to be a main barrier to cancer development because of its multiple antioncogenic functions.12-14 TP53 mutations, identified in 16% of cases of chronic MPN,15 are associated with a poorer prognosis16 and are considered key events in the transformation of chronic MPN to s-AML.17 However, TP53 mutations do not confer a clonal advantage to hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) in the absence of environmental selection pressure while ionizing radiation causes the expansion of TP53-mutated cells in vivo,18,19 underlining the role of the environment in the selection process of TP53-mutated clones. In MPNs, it has been suggested that patients receiving long-term hydroxyurea treatment may be prone to acquire or select TP53 mutations, but this was not confirmed,15 and until now, there is no clue to explain clonal expansion in patients. Recently, we observed the expansion of TP53-mutated clones in some MPN patients treated with an MDM2 inhibitor in a phase 1 trial (clinicaltrials.gov #NCT02407080).20,21 MDM2, an E3 ubiquitin ligase, targets p53 for degradation by the proteasome.22-24 Novel anticancer therapies have been developed to either restore the mutant p53 protein conformation25,26 or reinforce the wild-type p53 functions by inhibiting its degradation using MDM2 inhibitors. Several MDM2 inhibitors have been developed, the best described being nutlins, a family of small molecules blocking the p53-MDM2 interactions leading to stabilization of p53.27 These drugs have been evaluated in patients with solid cancers and hematological malignancies with promising results.

Because selection of cellular clones harboring TP53 mutations is a major path to the development of s-AML, we conducted studies dedicated to answering the following questions: Does MDM2 inhibition exert a direct selective pressure allowing the emergence of TP53-mutated clones? Does the molecular context (additional mutations) of TP53-mutated cells impact the selection potential of these drugs? Is it possible to predict the risk for an individual patient to select TP53-mutated clones before starting MDM2-inhibitor therapy?

Methods

Patients

MPN patients were selected based on the presence of 1 driver mutation and at least 1 TP53 mutation detectable by next-generation sequencing (NGS). Most of these patients also harbored mutations in other genes. Clinical and molecular characteristics are given in Table 1. The study was accepted by the local internal review board (Comité d’Evaluation de l’Ethique des projets de Recherche Biomedicale Paris Nord), and patients have given informed consent for the study.

Patients’ characteristics

| Patient . | Age . | Diagnosis . | Driver mutation . | Karyotype . | Molecular profile . | Treatments received . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MPN1 | 55 | PV | JAK2 | NA | JAK2 p.V617F. ASXL1 p.G646Wfs*12. EZH2 p.N688K. TP53 p.G245S. TP53 p.R175H. TP53 p.R248W. TP53 p.R248Q. TP53 p.Y234H. TP53 p.V172D. | Phlebotomy, interferon, ruxolitinib, idasanutlin |

| MPN2 | 76 | PMF | JAK2 | NA | JAK2 p.V617F. ASXL1 p.G819Efs*5. ASXL1 p.Q512*. DNMT3A p.R882H. TP53 p.Y163C | Ruxolitinib, EPO |

| MPN3 | 78 | PMF | JAK2 | 46.XY.del(13)(q1?2q1?4) [19]/46.XY[3] | JAK2 p.V617F. U2AF1 p.Q157P. TP53 p.C277Y. TP53 p.C242Y. | Hydroxyurea |

| MPN4 | 76 | ET | CALR | NA | CALR p.K385Nfs*47. TP53 p.H179R. TP53 p.R248W. | Hydroxyurea |

| MPN5 | 83 | PV | JAK2 | NA | JAK2 p.V617F. IDH1 p.R132H. DNMT3A p.V563M. TP53 p.C238Y. | Hydroxyurea |

| MPN6 | 82 | ET | JAK2 | NA | JAK2 p.V617F. TET2 p.S1059*. TET2 p.C1396Lfs*5 TET2 p.G1288D. TET2 p.R1216*. TP53 I255F | Hydroxyurea |

| MPN7 | 67 | PV | JAK2 | NA | JAK2 p.V617F. TET2 p.Q1654*. TP53 p.S241P | Pipobroman, interferon, hydroxyurea |

| MPN8 | 61 | Post-PV MF | JAK2 | NA | JAK2 p.V617F. TET2 p.I1873T. TET2 c.4537 + 3A > T. NFE2 p.T239Rfs*9. TP53 p.R175H | Phlebotomy, hydroxyurea, interferon |

| Patient . | Age . | Diagnosis . | Driver mutation . | Karyotype . | Molecular profile . | Treatments received . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MPN1 | 55 | PV | JAK2 | NA | JAK2 p.V617F. ASXL1 p.G646Wfs*12. EZH2 p.N688K. TP53 p.G245S. TP53 p.R175H. TP53 p.R248W. TP53 p.R248Q. TP53 p.Y234H. TP53 p.V172D. | Phlebotomy, interferon, ruxolitinib, idasanutlin |

| MPN2 | 76 | PMF | JAK2 | NA | JAK2 p.V617F. ASXL1 p.G819Efs*5. ASXL1 p.Q512*. DNMT3A p.R882H. TP53 p.Y163C | Ruxolitinib, EPO |

| MPN3 | 78 | PMF | JAK2 | 46.XY.del(13)(q1?2q1?4) [19]/46.XY[3] | JAK2 p.V617F. U2AF1 p.Q157P. TP53 p.C277Y. TP53 p.C242Y. | Hydroxyurea |

| MPN4 | 76 | ET | CALR | NA | CALR p.K385Nfs*47. TP53 p.H179R. TP53 p.R248W. | Hydroxyurea |

| MPN5 | 83 | PV | JAK2 | NA | JAK2 p.V617F. IDH1 p.R132H. DNMT3A p.V563M. TP53 p.C238Y. | Hydroxyurea |

| MPN6 | 82 | ET | JAK2 | NA | JAK2 p.V617F. TET2 p.S1059*. TET2 p.C1396Lfs*5 TET2 p.G1288D. TET2 p.R1216*. TP53 I255F | Hydroxyurea |

| MPN7 | 67 | PV | JAK2 | NA | JAK2 p.V617F. TET2 p.Q1654*. TP53 p.S241P | Pipobroman, interferon, hydroxyurea |

| MPN8 | 61 | Post-PV MF | JAK2 | NA | JAK2 p.V617F. TET2 p.I1873T. TET2 c.4537 + 3A > T. NFE2 p.T239Rfs*9. TP53 p.R175H | Phlebotomy, hydroxyurea, interferon |

EPO, erythropoietin; ET, essential thrombocythemia; MF, myelofibrosis; NA, not available; PMF, primary myelofibrosis; PV, polycythemia vera.

In vitro assay

CD34+ cells from MPN patients after NGS analysis were prospectively cryopreserved. Peripheral mononuclear cells were isolated from whole blood using Ficoll (Eurobio) and CD34+cells sorted using a column-free immunomagnetic approach (EasySep, StemCell). 105 CD34+ cells were cultured in CTSTM StemProTM hematopoietic stem cell expansion medium (Thermo Fisher) in which the following cytokines were added: IL-3 (50 ng/mL), stem cell factor (100 ng/mL), thrombopoietin (20 ng/mL) IL-6 (50 ng/mL), and FLT-3 ligand (100 ng/mL). Idasanutlin (provided by Roche) was added at 20 nM. After 10 days of culture, cells were harvested, DNA extracted, and submitted to NGS analysis. This test is developed under the patent application EP 21 305 499.2.

NGS analysis

We used a capture-based custom NGS panel (Sophia Genetics) targeting 36 myeloid genes (ABL1; ASXL1; BRAF; CALR; CBL; CCND2; CEBPA; CSF3R; CUX1; DNMT3A; ETNK1; ETV6; EZH2; FLT3; HRAS; IDH1; IDH2; IKZF1; JAK2; KIT; KRAS; MPL; NFE2; NPM1; NRAS; PTPN11; RUNX1; SETBP1; SF3B1; SH2B3; SRSF2; TET2; TP53; U2AF1; WT1; ZRSR2). Libraries were prepared on 200 ng extracted from whole-blood DNA (Qiagen), and sequencing was performed on a MiSeq instrument (Illumina). Bioinformatics were performed at Sophia Genetics (Switzerland) using the SOPHIA DDM software. Mean coverage 10% quantile for the 8 samples analyzed was 3004X with a mean coverage heterogeneity at 0.07%. Significant variants were retained with a sensitivity of 1%.

Single-cell DNA analysis

The same sample cultured in vitro was used for single-cell DNA analysis. CD34+ were resuspended in Tapestri cell buffer (Mission Bio) and quantified using an automatic cell counter (Biorad). Single cells (3000-4000 cells per μL, >80% viable) were encapsulated using a Tapestri microfluidics cartridge (Mission Bio), lysed, and barcoded. Barcoded samples were then subjected to targeted polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of a custom 96 amplicons covering 17 genes known to be mutated in MPN (ASXL1; CALR; CBL; DNMT3A; EZH2; IDH1; IDH2, JAK2; KRAS; MPL; NFE2; NRAS; SF3B1; SRSF2; TET2; TP53; U2AF1). PCR products were removed from individual droplets, purified with Ampure XP beads (Beckman Coulter), and used as a template for PCR to incorporate Illumina i5/i7 indices. PCR products were purified a second time, quantified via an Agilent Bioanalyzer, and pooled to be sequenced. Library pools were sequenced on a NextSeq instrument (Illumina). Fastq files were processed using the Tapestri Pipeline for cell calling and using Genome Analysis Toolkit 4/haplotype caller for genotyping. The Tapestri Insights software was used to further filter variants (see details in Supplemental data), and samples were included if they harbored 3 or more protein-encoding, nonsynonymous/insertion/deletion variants and >1000 cells with definitive genotype for all protein-coding variants within the sample. We next sought to define genetic clones, which we identified as cells that possessed identical genotype calls for the protein-encoding variants of interest. Importantly, almost 95% of the panel amplicons in each sample had sufficient coverage to annotate variants. The estimated median allele dropout rate was 8.74% (IQR, 6.5% to 10.6%, Supplementary Table 2). From the variants annotated for each sample, we first removed those with low quality (<0% in the Tapestri Insights software) and low frequency (<0.5% cells) (Supplementary Figure 3). As a result, we detected a total of 37 different variants passing the prefiltering step across the 8 patients (Supplementary Table 1), with a median of 4 variants per patient (IQR, 3.25-4.75). All variants detected in bulk whole-blood NGS analysis below the 0.5% threshold were not considered in the single-cell analysis.

Results

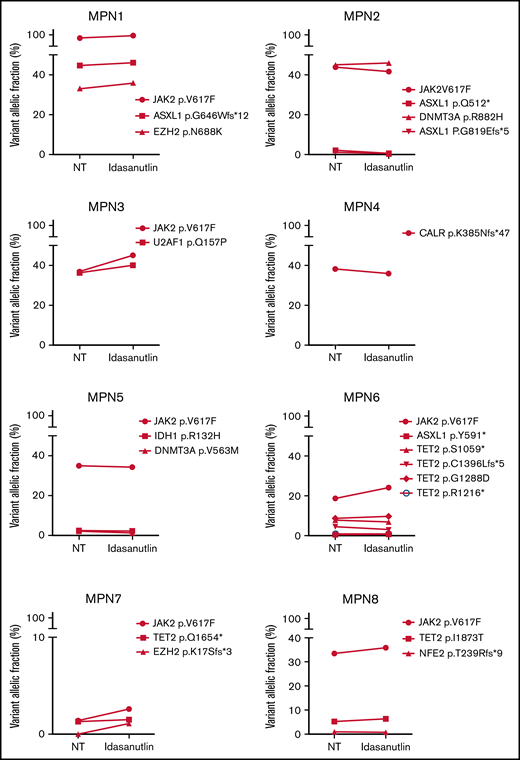

Direct and rapid selection of TP53-mutated clones under MDM2 treatment

After the observation of increased allelic frequencies of TP53 mutations in 5 patients treated in vivo with idasanutlin, an MDM2 inhibitor,21 we addressed the question of a direct effect of this drug on the selection of mutated cells. We aimed at reproducing the clinical observation with a short-term in vitro culture of patient samples using a controlled medium to support the hypothesis of a direct targeted cellular effect of MDM2 inhibition. Eight patients harboring at least 1 driver mutation and 1 TP53 mutation were examined for the impact of idasanutlin on the selection of TP53-mutated subclones. Patient’ clinical and molecular characteristics are depicted in Table 1. We first determined the optimal culture conditions and idasanutlin concentrations that limited cellular proliferation of CD34+ cells from 3 MPN patients (supplemental Figure 1A-B). A dose of 20 nM idasanutlin was identified as optimal and used in the subsequent experiments. CD34+ cells from TP53-mutated patients were cultured with or without idasanutlin. After 10 days, cells were retrieved and NGS sequenced as previously described.28 To validate the culture conditions, we compared the variant allelic frequencies (VAF) of every mutation found after 10 days without treatment to those found in whole-blood DNA. For a total of 37 mutations, we observed an excellent correlation between VAFs measured by NGS after culture of CD34+ cells and VAFs measured in bulk whole-blood DNA (R = 0.979, P < .0001) (supplemental Table 1; Figure 1A), demonstrating that the culture conditions reproduced the in vivo situation without altering the molecular architecture of MPN cells. To estimate the accuracy of this assay for reproducing the in vivo selection of TP53-mutated clones, we analyzed cells taken from a patient (#MPN1) who had experienced an expansion of TP53-mutant clones in vivo during idasanutlin therapy21 and found a similar increase of TP53 mutation VAFs in CD34+ cells in vitro (Figure 2A). We concluded the in vitro culture conditions we defined closely replicated the in vivo process of a clonal selection of TP53-mutated cells. We then tested 7 additional patient samples using this assay and observed an increase of each TP53 mutant VAF after idasanutlin treatment compared with the untreated conditions (Figure 2B). In patients with several TP53 mutations, the VAF of each of these mutations increased independently. Altogether, the mean VAF of TP53 mutations was significantly higher in the presence of the MDM2 inhibitor treatment compared with the untreated condition (7.38% vs 3.34%, respectively; P < .01) (Figure 2C). Importantly, such increase was not observed under in vitro exposure to ruxolitinib (Figure 2C). To evaluate the specificity of the selection for TP53 mutations, we considered in each sample the variants found in all genes. Contrary to TP53 mutations, the VAFs of mutations found in other genes showed no significant variation after culture with idasanutlin (driver mutations, not treated: 38.29% vs idasanutlin: 39.93%, P = .25; additional non-TP53 mutations, not treated: 11.59% vs idasanutlin: 11.98%, P = .30, Figure 3), strongly indicating a specific selection of TP53 mutation-bearing cells by idasanutlin.

Comparison of VAF determined by sequencing using the 3 techniques: whole blood NGS, CD34+ cell culture NGS, and single-cell sequencing. (A) Plot showing VAFs of the indicated mutants in whole-blood (red circle), single-cell (blue square), or CD34+-cultured cells without treatment (green triangle). (B) Correlation between single-cell sequencing and whole blood NGS on 37 variants described in supplemental Table 1. VAF, variant allelic fraction.

Comparison of VAF determined by sequencing using the 3 techniques: whole blood NGS, CD34+ cell culture NGS, and single-cell sequencing. (A) Plot showing VAFs of the indicated mutants in whole-blood (red circle), single-cell (blue square), or CD34+-cultured cells without treatment (green triangle). (B) Correlation between single-cell sequencing and whole blood NGS on 37 variants described in supplemental Table 1. VAF, variant allelic fraction.

Increase of mutant TP53 VAFs in HSPC of TP53-mutated MPN patients upon MDM2 inhibitor treatment. (A) Comparison of various TP53-mutations’ VAFs in CD34+ cells of MPN1 patient after 10 days with or without 20 nM of idasanutlin. (B) Comparison of all TP53-mutations’ VAFs in CD34+ cells of 8 different MPN patients after 10 days in presence or absence of idasanutlin 20 nM. (C) Mean plus or minus SD of VAFs for all TP53 mutants found in 8 MPN patients after 10 days in presence or absence of idasanutlin 20 nM or ruxolitinib 70 nM in 4 other MPN patients. A paired Student t test was used, **P < .01. ns, nonsignificant; SD, standard deviation.

Increase of mutant TP53 VAFs in HSPC of TP53-mutated MPN patients upon MDM2 inhibitor treatment. (A) Comparison of various TP53-mutations’ VAFs in CD34+ cells of MPN1 patient after 10 days with or without 20 nM of idasanutlin. (B) Comparison of all TP53-mutations’ VAFs in CD34+ cells of 8 different MPN patients after 10 days in presence or absence of idasanutlin 20 nM. (C) Mean plus or minus SD of VAFs for all TP53 mutants found in 8 MPN patients after 10 days in presence or absence of idasanutlin 20 nM or ruxolitinib 70 nM in 4 other MPN patients. A paired Student t test was used, **P < .01. ns, nonsignificant; SD, standard deviation.

Absence of variation of non-TP53 mutations in HSPC of TP53-mutated MPN patients upon MDM2 inhibitor treatment. Comparison of VAFs for mutations found in other genes in CD34+ cells of the same MPN patients. **P < .01 using a Student t test for statistical comparison. NT, not treated.

Absence of variation of non-TP53 mutations in HSPC of TP53-mutated MPN patients upon MDM2 inhibitor treatment. Comparison of VAFs for mutations found in other genes in CD34+ cells of the same MPN patients. **P < .01 using a Student t test for statistical comparison. NT, not treated.

In 4 of the 8 patients tested, we identified TP53 mutations in the treated sample that were not detected in the untreated sample or in the whole-blood DNA. We tracked these emerging mutations by carefully checking the raw sequencing data from whole blood using Integrative Genomics Viewer software and identified in each case significant amounts of mutant reads (not shown). For patient #MPN1, who received idasanutlin therapy, the presence of these low-level mutations was further confirmed by their detection in a subsequent blood sample taken 3 months later. In patient #MPN4, treated only with hydroxyurea for 20 years, the mutation (p.Y176C) detected after in vitro culture with idasanutlin was eventually found in a follow-up whole blood sample taken 1 year later. This observation confirmed prior experiments suggesting that idasanutlin is not likely to induce TP53 mutations but rather participates in their selection.21

Altogether, using this new in vitro culture assay with defined and controlled medium combined with NGS analysis after 10 days of culture, we confirmed in 8 different patients and for a total of 16 TP53 mutations a direct and rapid effect of idasanutlin exposure on the selection of TP53-mutated MPN CD34+ cells. Importantly, this test also appears able to uncover TP53-mutated clones that may be selected in vivo before initiating treatment with an MDM2 inhibitor, even when they are undetectable in patients’ blood using NGS analysis.

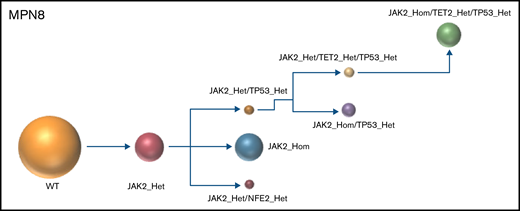

Single-cell–derived clonal architecture and selection of TP53-mutant MPN cells

Both driver and nondriver mutations found in MPN cells target important regulatory pathways such as intracellular signaling, DNA methylation, histone modifications, or splicing processes that could modulate the effects of drugs like MDM2 inhibitors. To better decipher the impact of MDM2 inhibition on clonal selection, we next investigated the cooccurrence and order of mutation acquisition for each of the 8 patients tested in vitro. Clonal architecture was determined using the single-cell high-throughput microfluidic Tapestri platform coupled to the Tapestri Insights bioinformatics software (Mission Bio). As recently reported,29 this approach permitted accurate analysis of thousands of single cells per specimen. From 8 patient samples, a total of 45 443 cells were sequenced, with a median of 4923 cells per sample (interquartile range [IQR], 3820-8172). The panel designed for this study covered 17 of the most frequent MPN mutated genes. The median sequencing coverage was 100 reads per amplicon per cell (IQR, 48.07-127.2). To validate the accuracy of the variant identification in single cells, we compared the allelic frequency of each mutation found with single-cell analysis with the VAFs found with NGS of whole-blood DNA. Among 37 variants identified by whole-blood NGS and covered by the panel, 100% (33 single nucleotide variants and 4 indels) were also detected using the single-cell approach. For each variant, there was an excellent correlation between the proportions of mutant alleles detected at single-cell level and the VAFs measured with whole-blood DNA (Figure 1A). When considering all the variants together, the allelic fractions quantified by single-cell and whole-blood NGS were highly correlated (R = 0.991, P < .0001, Figure 1B).

The results of the single-cell analysis allowed us to infer the order of acquisition of somatic events and hence reconstitute the clonal architecture for each patient (Figure 4). In 5 patients, we observed a major clone harboring 1 to 3 variants and comprising 32% to 75% of the cells associated with 2 to 9 minor subclones with <10% of the cells (#MPN1 to 5, supplemental Table 3). In 3 patients, several clones of comparable sizes were present without 1 dominant clone (#MPN6 to 8) (Figure 4; supplemental Table 3). In most cases, the first molecular event was a driver mutation in JAK2 or CALR. Only in #MPN2 and #MPN3 patients were DNMT3A and U2AF1 mutations, respectively, the initial events (Figure 4). Several striking observations on the clonal architecture of MPN rapidly emerged from this study. First, clonal evolution of MPN was rarely linear with sequential accumulation of mutations in the same clone. To the contrary, we observed branching evolution with several clones evolving simultaneously in the majority of samples (Figure 4). Another important finding was that JAK2V617F homozygous subclones were present in all JAK2V617F-mutated patients evaluated. In #MPN1 patient, homologous recombination giving rise to a homozygous clone occurred early in disease development and was present in almost all the single cells tested. In other patients, homologous recombination occurred as a late event and was present in a minor subclone (#MPN3) or even in several minor subclones (#MPN8). Finally, we observed that TP53 mutations always appeared late during clonal evolution and exclusively in clones harboring a driver mutation (JAK2 or CALR in this study). Although the number of patients tested was limited, it is unlikely that these conclusions can be attributed to chance as this association was observed in 8 out of 8 patients. Furthermore, we tested several patients with multiple TP53 mutations, which all developed in distinct clones, but always in cells carrying the driver mutation. For example, in #MPN1, a major JAK2/ASXL1-mutated clone was present from which emerged 3 subclones, each with a different TP53 mutation (Figure 4). Multiple independent TP53-mutated subclones within the driver clone were also detected in #MPN3 and #MPN4 patients (Figure 4). The absence of JAK2 wild-type/TP53-mutated cells was unexpected because JAK2V617F+ MPN may evolve to JAK2 wild-type/TP53-mutated acute leukemia, whereas genotypic reversion by mitotic recombination or gene deletion has been previously excluded as an explanation for the development of JAK2 wild-type leukemia in JAK2-mutated patients.30

Clonal architecture of TP53-mutated MPN patients. Phylogenetic trees show the order of mutation acquisition during MPN history with maximum likelihood in 8 patients. The mutational history was manually reconstructed from the single-cell data. In the case of MPN3, it was not possible to infer the order of mutation acquisition in JAK2 and U2AF1 because of the absence of cells with wild-type version of these genes. Each circle represents a clone identified in single-cell analysis using Tapestri platform and Tapestry Insights software (Mission Bio). The size of each circle denotes the relative clone size. The nomenclature of each mutation is indicated only when 2 or more mutations were present in the same gene.

Clonal architecture of TP53-mutated MPN patients. Phylogenetic trees show the order of mutation acquisition during MPN history with maximum likelihood in 8 patients. The mutational history was manually reconstructed from the single-cell data. In the case of MPN3, it was not possible to infer the order of mutation acquisition in JAK2 and U2AF1 because of the absence of cells with wild-type version of these genes. Each circle represents a clone identified in single-cell analysis using Tapestri platform and Tapestry Insights software (Mission Bio). The size of each circle denotes the relative clone size. The nomenclature of each mutation is indicated only when 2 or more mutations were present in the same gene.

Interestingly, several patients had additional and independent clones with mutations affecting epigenetic genes (TET2 and DNMT3A) in small numbers of cells (#MPN5, 6, and 7, Figure 4). According to the advanced age of these particular patients, these clones could simply reflect clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP) without oncogenic potential occurring independently of MPN-related clones.

The concomitant analysis on the same samples of MDM2 inhibitor treatment and single-cell DNA clonal architecture allowed us to determine the molecular background in which TP53 mutations are acquired at the single-cell level and whether this background may affect their selection by MDM2 inhibitors. We found that TP53 mutations may be acquired in 3 distinct scenarios: either in a clone mutated for a driver gene and an epigenetic gene (TET2, DNMT3A, ASXL1 or EZH2), which is the most frequent situation (#MPN1, 2, and 6); in a clone mutated for a driver gene and a splicing factor (U2AF1 in #MPN3); or in a clone with a driver mutation only that has undergone homologous recombination (#MPN7) or not (#MPN4, 5, and 8). Thus, TP53 mutations may be acquired in a large array of molecular landscapes without evidence for a specific association with a particular pathway alteration, with the notable exception of the presence of a driver mutation. With idasanutlin treatment in vitro, we observed a significant increase in the VAFs of every TP53-mutated clone. We did not identify any additional mutations that might favor or antagonize idasanutlin-dependent selection of TP53-mutated clones, but the numbers of clones were relatively small, and confirmatory studies would be of interest. Nevertheless, our study shows that the selection by idasanutlin at the single-cell level was due to the presence of TP53 mutation itself, independently of associated mutations.

Discussion

Cancer development is a long and heterogeneous process with several steps leading from preneoplastic lesions to life-threatening tumors. This evolution is usually dependent on a stepwise acquisition of mutations followed by clonal selection,10 but it is more and more recognized that context-specific selection forces must be considered to understand and hopefully prevent clonal selection.11,31 The selection of cells harboring molecular alterations in oncogenes or tumor suppressors is a crucial step of leukemogenesis, and identification of the mechanisms involved has great implications for both comprehension and prevention of transformation. Although mutations are supposed to give self-advantage to cells, a direct selective pressure induced by extracellular parameters from the microenvironment may participate in clonal selection. Chronic myeloid disorders like MPNs represent interesting models as it is possible to follow the clonal selection during the disease evolution, but the definitive identification of environmental agents responsible for clonal selection is lacking.

The TP53 gene encodes the major tumor suppressor p53. p53 functions are regulated by protein-protein interactions, particularly by the MDM2 E3 ubiquitin ligase, which is responsible for addressing p53 to the proteasome and its subsequent degradation. TP53 is the most frequently mutated gene in all cancer subtypes and particularly in post-MPN leukemic transformation. Several genes that may also play a role in disease evolution are found mutated in MPN patients, but the cosegregation of these mutations with TP53 mutations, defining the clonal architecture of TP53 mutations, is rather undescribed. Whether these mutations can arise in a particular, more permissive molecular environment is unknown. Very few studies based on single-cell analyses have reported TP53 mutation clonal architecture evolution during the course of MPNs. Miles and colleagues found only 1 patient with cooccurrence of JAK2V617F with a TP53 mutation that disappeared at the time of transformation.29 Thompson and colleagues reported a single patient harboring a clone with concomitant CALR and TP53 mutations at the time of leukemic transformation.32 Using a recent microfluidic instrument coupled to a panel-based NGS analysis, we performed a single-cell characterization of TP53-mutated MPN patients. This approach revealed novel information on MPN clonal architecture. We observed that clonal evolution was frequently made of sequential branching instead of linear acquisition of mutations in the same clone. We also noted the frequent acquisition of homozygous JAK2V617F mutation in small subclones. Several profiles showed acquisition of small clones carrying mutations in TET2 or DNMT3A, which was reminiscent of clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential, suggesting that MPN patients may develop apparently non–disease-related clones in parallel of clones bearing the driver mutation. Regarding acquisition of TP53 mutations, we found that they were the latest events in most patients tested, suggesting that these mutations arise after a long time of disease evolution. Another striking observation was that they always cooccurred with driver mutations, even in patients with multiple TP53 mutations, which all developed in individual clones but always in cells carrying a driver mutation. This observation was a bit confusing because it has been demonstrated that JAK2V617F+ MPN may transform to JAK2 wild-type/TP53-mutated acute leukemia. The frequency of this genotype is variable with studies, from very rare33 to a significant proportion of patients.34 Thus, and as previously suggested,30 TP53 mutations can occur in a different clone than the JAK2-mutated clone. However, our findings suggest that TP53-mutated/JAK2 wild-type cells are very infrequent in the chronic phase of MPN. Such cells may be selected very late and then rapidly lead to the transformation, possibly due to a higher transforming potential than cells mutated for both JAK2 and TP53. Of note, the hypothesis of a genetic reversion from JAK2V617F to JAK2 wild-type by mitotic recombination or gene deletion has been previously excluded as an explanation for the development of JAK2 wild-type leukemia in MPN patients.30

In the aim of preventing leukemic transformation, understanding which circumstances may favor the selection of cells carrying TP53 mutations is crucial. MPN patients are treated for years with various antiproliferative drugs, and some treatments have been clearly shown to favor the transformation process, such as alkylating agents.5 However, the participation of long-term treatment in MPN patients in the clonal selection of TP53 mutations is still elusive.15 Particularly, hydroxyurea has been suspected, but no definitive correlation has been established. Recent anticancer therapeutic approaches aim at enhancing the p53 tumor suppressor activity, notably using MDM2 inhibitors such as nutlins27 to rescue p53 from degradation.35 This novel class of drugs is now tested in a wide variety of cancers including hematological malignancies. Clinical trials evaluated these drugs in AML,36,37 and based on the selective activity of nutlins on JAK2V617F-mutated PV progenitor cells,38 a phase 1 trial has been launched testing idasanutlin in PV patients.20 We recently reported in 5 patients included in this study the increase of TP53 mutant VAFs21 suggesting a role for MDM2 inhibition in the positive selection of TP53-mutated cells. However, several parameters may influence the clonal evolution in vivo, and to demonstrate a direct effect of idasanutlin in the expansion of TP53-mutated clones, we performed in vitro culture of patient-derived HSPCs in a defined medium. We observed after a short delay (10 days) a selection of TP53-mutated cells at the expense of wild-type cells. Importantly, this was reproducible in 8 out of 8 patients, with 16 different TP53 mutations targeting the DNA-binding domain between exon 5 and 8 (5 mutations in exon 5, 4 mutations in exon 6, 5 in exon 7, and 2 in exon 8). In patients harboring several TP53 mutations, we observed that each individual mutation VAF increased. In the same time, none of the VAF of other mutations present in these patients increased. This demonstrated that MDM2 inhibition directly favors the expansion of cells harboring TP53 mutations, an effect not observed in this study with JAK inhibition using ruxolitinib, and raises the question of the mechanism by which the inhibition of MDM2 acts on clonal selection. One explanation is that idasanutlin treatment activates the p53 pathway and cell death in wild-type p53 cells, which would not occur in p53 mutant cells with loss of wild-type functions. The other explanation is that mutations confer gain-of-function to p53, leading to positive selection of mutated cells. The possibility of gain-of-function mutations in p53 is still debated,39,40 but it would be interesting to test the drug on TP53-mutated or inactivated cells to explore a possible gain of function of the mutated forms in the survival of these cells under treatment. Thus, we developed an in vitro assay using patient’ cells, which has the potential to uncover TP53-mutated clones that were not detected by NGS. Better sensitivity could be obtained using digital PCR, but such strategy is hardly applicable to the screening of unknown mutations as each assay is dedicated to the detection of one particular mutation.

Blastic transformation of MPN to s-AML is a main concern for patients and physicians. Some clinical studies reported significant association between treatments and a higher risk of s-AML, but the molecular mechanisms involved in the transformation process are unknown. Among all the mutations identified as high-risk mutations, only TP53 mutations have been demonstrated to increase the risk of AML when associated to the JAK2V617F mutation.17,41 Therefore, understanding which circumstances may favor the selection of cells carrying TP53 mutations appears relevant for preventing leukemic transformation in MPN. The results presented herein establish for the first time the causality of a given treatment in the selection of MPN subclones associated with leukemic transformation. With the exception of driver mutations, we did not identify any gene or pathway being redundantly mutated and cosegregating with the TP53 mutations, suggesting that only TP53 mutations confer a selective advantage under idasanutlin therapy. Therefore, one can suspect that selection of TP53-mutated cells may occur whatever the tissue and the subtype of cancer.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Robert Durruthy-Durruthy and Gema Fuerte from Mission Bio for their precious help in single-cell data interpretation.

This work was supported by grants from Fondation Saint-Louis, Force Hémato, and INCa (2018-PLBIO-10-APHP-1).

Authorship

Contribution: N.M. performed in vitro culture and single-cell experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; E.V. performed single-cell experiments and analyzed bulk NGS data; M.C. performed in vitro experiments; R.H. and J.M. provided essential patients specimens; S.G. provided essential patients specimens and edited the manuscript; and B.C. and J.-J.K. designed the study, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: J.M. reports research funding to the institution from Incyte, Novartis, Roche, pharmaEssentia, Geron, CTI Bio, and Forbius; and consulting fees from Incyte, Roche, BMS/Celgene, CTI Bio, Geron, Sierra Oncology, Constellation, and Abbvie. J.-J.K. reports advisory boards for Novartis, Incyte, Abbvie, AOP Orphan, and BMS.

Correspondence: Jean-Jacques Kiladjian, Centre d’Investigations Cliniques, Hopital Saint-Louis, 1 Avenue C. Vellefaux, 75010 Paris, France; e-mail: jean-jacques.kiladjian@aphp.fr.

References

Author notes

B.C. and J.-J.K. contributed equally to this study.

B.C. and J.-J.K. are joint senior authors.

Requests for data sharing may be submitted to Jean-Jacques Kiladjian (jean-jacques.kiladjian@aphp.fr).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.