Ectopic retroviral expression of homeobox B4 (HOXB4) causes an accelerated and enhanced regeneration of murine hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) and is not known to compromise any program of lineage differentiation. However, HOXB4 expression levels for expansion of human stem cells have still to be established. To test the proposed hypothesis that HOXB4 could become a prime tool for in vivo expansion of genetically modified human HSCs, we retrovirally overexpressed HOXB4 in purified cord blood (CB) CD34+ cells together with green fluorescent protein (GFP) as a reporter protein, and evaluated the impact of ectopic HOXB4 expression on proliferation and differentiation in vitro and in vivo. When injected separately into nonobese diabetic–severe combined immunodeficient (NOD/SCID) mice or in competition with control vector–transduced cells, HOXB4-overexpressing cord blood CD34+ cells had a selective growth advantage in vivo, which resulted in a marked enhancement of the primitive CD34+ subpopulation (P = .01). However, high HOXB4 expression substantially impaired the myeloerythroid differentiation program, and this was reflected in a severe reduction of erythroid and myeloid progenitors in vitro (P < .03) and in vivo (P = .01). Furthermore, HOXB4 overexpression also significantly reduced B-cell output (P < .01). These results show for the first time unwanted side effects of ectopic HOXB4 expression and therefore underscore the need to carefully determine the therapeutic window of HOXB4 expression levels before initializing clinical trials.

Introduction

Gene transfer into hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) offers novel alternatives in the treatment of many inherited and acquired disorders.1,2 Considerable progress has been made in defining ex vivo culture conditions that allow efficient gene transfer into long-term repopulating human cells from cord blood and adult bone marrow.3-10 However, particularly in gene therapy of inherited diseases, the low number of transplantable transduced stem cells relative to the noncorrected resident marrow of unconditioned patients represents a challenging hurdle, which needs to be overcome. The use of drug resistance markers to enrich gene-corrected HSCs to clinically relevant levels may be indicated in course of the treatment of cancer patients.11-14 Yet, owing to the inherent high toxicity of the antineoplastic drugs,15 such a strategy is not warranted for the treatment of many other diseases. Also, clinical transplantation settings in which the initial HSC cell dose is the limiting factor would not benefit. Hence, efficient means of selective expansion of genetically modified HSCs, either in vitro prior to transplantation or in vivo, is of key importance for future progress.

Coexpression of a nonselectable therapeutic gene of interest together with a transgene, which gives transduced HSCs a repopulation advantage over nontransduced stem cells, may offer a solution. The homeobox geneHOXB4 is the only gene known so far whose ectopic expression confers a selective growth advantage in vitro and a competitive repopulation advantage in vivo to murine HSCs, without compromising differentiation or homeostatic regulation of the HSC pool size.16-18 These results favor HOXB4 as a candidate gene for ex vivo/in vivo amplification of gene-modified human HSCs. However, imbalanced expression of several other members of theHOXA and HOXB gene cluster has been linked to the development of myeloid leukemias in mice and human patients.19-30 Thus, a therapeutic window for homeobox B4 (HOXB4) expression levels needs to be defined in human stem and progenitor cells before its clinical use can be realized. Owing to the nature of the vector originally used by Humphries and colleagues16 (MSCV-HOXB4-pgk-Neo [MSCV-HOXB4– phosphoglycerate kinase promotor– neomycin resistance gene]), it was not possible for them to draw conclusions on the amount of ectopically expressed HOXB4 necessary for the observed effect of in vivo expansion.

Recently, we have shown that a novel retroviral vector–based coexpression strategy can be used for functional coexpression of HOXB4 together with a fluorescent reporter gene in vivo,31namely the 2A esterase of foot-and-mouth disease virus (FMDV). The self-processing 2A esterase of FMDV modulates translation at the glycyl-prolyl bond at its own C-terminus, leading to the separation of the growing polypeptide chain. The 2A strategy allows a precise quantification of HOXB4 expression levels because the separated proteins green fluorescent protein (GFP) and HOXB4 are produced at constant molar ratios of about 8:1.32 Thus, this approach enables a predictable expression of HOXB4 and of a second gene of interest. Expression levels of HOXB4 can be further adjusted by placing the bicistronic 2A cassette under the transcriptional control of differentially active retroviral long terminal repeats (LTRs) (eg, murine embryonic stem cell virus [MESV] or friend-mink cell focus-forming [FMEV]/MESV hybrid vector).33

In this study, we transduced human cord blood CD34+ cells with a series of 2A-based HOXB4-coexpression vectors, which mediate significantly different HOXB4 expression levels. Our results demonstrate that the precise effects of ectopic HOXB4 expression on proliferation and differentiation of primitive human hematopoietic cells are concentration dependent. Enforced overexpression of HOXB4 conferred a marked in vivo selective growth advantage to transduced human CD34+ cells that resulted in an enhanced regeneration of human CD34+ cells in the marrow of nonobese diabetic–severe combined immunodeficient (NOD/SCID) mice that have received transplants. However, high levels of HOXB4 expression severely impaired the lymphoid and myeloerythroid differentiation of human CD34+ cells in vitro and in vivo.

Materials and methods

Retroviral constructs

For expression of an HOXB4 protein N-terminally tagged with the hemagglutinin (HA) epitope, polymerase chain reaction (PCR)–based modification of the HOXB4 cDNA was performed with the use of MSCV(MESV)–GFP2AHOXB4 as a template31 and the following oligodeoxynucleotides as primers: 5′-CCTACCCATACGACGTCCCAGACTACGCTTTGGCTATGAGTTCTTTTTTGATCAACTCAAAC-3′ and 5′-GTCGACGGATCCATCTTCGCCAAAGCTGAAACG-3′. The amplification product was ligated into the SrfI predigested PCR-Script vector (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). Subsequently, the HOXB4 cDNA in pEGFP2AHOXB4 (Klump et al31) was replaced by inserting theHAHOXB4 cDNA as an NotI (Mung bean blunted)–BamHI fragment into EcoRI (Mung bean blunted)–BamHI cut pEGFP2AHOXB4. From the resulting plasmid pEGFP2AHAHOXB4, the HAHOXB4 cDNA was finally excised withXhoI and BamHI and exchanged with theFLAGHOXB4 cDNA fragment from MSCV-GFP2AHOXB4 cut with the same restriction enzymes. For FMEV-GFP2AHAHOXB4 and FMEV-GFP2AHAHOXB4wPRE (FMEV-GFP2AHAHOXB4–posttranscriptional regulatory element of the woodchuck hepatitis virus), a Klenow polymerase–treated NcoI-BamHI fragment of pGFP2AHAHOXB4 was blunt-end ligated into the vector backbone portion of the previously described plasmids SF91-EGFP and SF91-EGFPwPRE,34 treated before with EcoRI,NotI, and Klenow polymerase. The vector FMEV-RFPwPRE was generated by blunt-end insertion of theNotI-EcoRI fragment from pDsRed1-N1 (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA) into EcoRI (blunted)–NotI (blunted) digested SF91-EGFPwPRE.

For construction of MSCV-HAHOXB4-pgk-Neo, a PCR reaction was carried out with MSCV-HOXB4-pgk-Neo16 as a template and the following desoxyoligonucleotides as primers: 5′-GCCATGGCCTACCCATACGACGTCCCAGACTACGCT-3′ and 5′-GTAATCGCTC-TGTGAATA-3′. The amplification product was subcloned into the SrfI predigested PCR-Script vector. Subsequently, an 80-bp EcoRI-SalI fragment containing the proximalHAHOXB4 sequence was inserted into MSCV-HOXB4-pgk-Neo from which the complete HOXB4-pgk-Neo cassette was released after cutting with the same restriction enzymes. Finally, the SalI fragment carrying the distal part of the HOXB4-pgk-Neo casette was reintroduced into the vector, resulting in MSCV-HAHOXB4-pgk-Neo.

FMEV-HAHOXB4-IRES-GFPwPRE was generated by ligation of the blunted 958-bp NcoI-HindIII fragment of MSCV-HAHOXB4-pgk-Neo into the NotI site of SF91-EMCV-IRES-GFPwPRE (R780; M. Schwieger et al, personal communication, February 2002). An NcoI site containing the ATG initiation codon of HOXB4 was introduced by PCR of the 5′-region of the HOXB4 gene with the use of the oligonucleotides 5′-CCCAGAAATCCATGGCTATGAGTTCTTTTTTG-3′ and 5′-GTAATCGCTCTGTGAATA-3′. Subsequently, the PCR product was digested with NcoI and SalI and exchanged with a 71-bpNcoI-SalI proximal HAHOXB4 fragment, generating FMEV-HOXB4-IRES-GFPwPRE.

Generation of retroviral supernatants

Vector particles pseudotyped with the feline endogenous virus (RD114) envelope protein35 were produced by transient calcium phosphate cotransfection of “phoenix-gp” packaging cells (G. Nolan, Stanford University, School of Medicine, CA) with the use of 5 μg retroviral vector plasmid together with 10 μg of plasmid expressing MLV gag-pol and 5 μg of a third plasmid encoding the RD114 envelope as described previously.31 Cell culture supernatants were harvested 30, 48, 60, and 72 hours after transfection and stored in aliquots at −70°C until use. For titer determination via GFP- or red fluorescent protein (RFP) fluorescence, respectively, serial dilutions of viral supernants were assayed on human HT1080 cells. The apparent titers ranged from 1.0 to more than 10 × 106 infectious particles (IPs) per milliliter.

Collection and immunoselection of CD34+ cells

Cord blood (CB) samples were collected after normal full-term delivery with informed consent of the mothers according to approved institutional guidelines. Mononuclear cells (MNCs) were collected by density centrifugation by means of Ficoll (Biochrom KG, Berlin, Germany). MNCs were immunolabeled by means of the CD34 Multisort Cell Isolation Kit (Miltenyi Biotech, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. CD34+ cells were ennriched to greater than 98% purity by magnetic cell sorting over 2 LS+ separation columns (Miltenyi Biotech) and cyropreserved in liquid nitrogen until further use.

Recombinant human cytokines

Recombinant interleukin 3 (IL-3) and soluble IL-6 receptor (IL-6sR) were obtained from R&D Systems (Wiesbaden, Germany). All other recombinant human growth factors were purchased from Stem Cell Technologies (Vancouver, BC, Canada).

Retroviral transduction of cord blood CD34+cells

Thawed CD34+-selected cells (pool of 10 different CB-donor samples) were plated at 1 × 106/mL in serum-free medium (StemSpan; Stem Cell Technologies) plus 40 μg/mL low-density lipoproteins (LDLs) (Sigma, Taufkirchen, Germany) in the presence of 5 recombinant human cytokines: stem cell factor (SCF) (100 ng/mL); Flt-3 ligand (FL) (100 ng/mL); thrombopoietin (TPO) (20 ng/mL); interleukin-6 (IL-6) (20 ng/mL); and IL-6sR (100 ng/mL). After precultivation for 24 hours, prestimulated cells (5 × 105 cells per well in 1 mL serum-free medium) were transferred into 24-well plates that had been precoated with 10 μg/cm2 RetroNectin (CH-296; Takara Shuzo, Otsu, Japan) and preloaded 3 times with retroviral vector particles. Virus preloading was performed in 3 centrifugation steps (at 1100g) carried out at 4°C for 20 minutes with the use of 1 mL viral supernatant per well each time. Before use, the different viral supernatants were all adjusted to 1 × 106 IPs per milliliter. Over the next 2 days, the CD34+ cells were resuspended in fresh, cytokine-supplemented serum-free medium and transferred to new virus-preloaded 24-well plates, for a total of 3 infections. Cells were harvested 24 hours after the third infection, washed twice in phophate-buffered saline (PBS) (Gibco, Karlsruhe, Germany) and resupended in Iscove modified Dulbecco medium (IMDM) at a concentration of 1 × 106 input CD34+ cells per milliliter of medium.

In vitro culture of hematopoietic cells

For induction of myeloid differentiation, 30 000 transduced or mock-transduced CD34+ cells were cultured in duplicate for 7 days in 1 mL IMDM containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) (Stem Cell Technologies) plus 10 ng/mL of each of the cytokines SCF, IL-3, IL-6, IL-1β, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF). Thereafter, total cell numbers were evaluated, and aliquots were used for flow-cytometric analysis of immunophenotype (CD33, CD14, and CD15) and reporter gene expression.

Clonogenic progenitor assays

Assays for in vitro colony-forming cells (CFCs) were performed by plating samples of transduced and mock-transduced CD34+cells in duplicate at 5 × 102 cells per milliliter of complete methylcellulose medium (Methocult GF, H4434; Stem Cell Technologies), which contains a mixture of recombinant human cytokines (SCF, IL-3, GM-CSF, and erythropoietin). Colonies were counted after 12 to 14 days of incubation at 37°C and classified according to standard criteria. The presence of human CFCs in the marrow of NOD/SCID mice that received transplants was assayed in the same methylcellulose medium at a concentration 5 × 105 cells per milliliter in duplicate. These conditions are selective for human colonies.

Transplantation into NOD/SCID mice

NOD/LtSz-scid/scid (NOD/SCID) mice obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Sulzfeld, Germany) were maintained at the animal facility of the Heinrich-Pette-Institute (Hamburg, Germany). Mice were handled under sterile conditions and kept in microisolators. Prior to transplantation (fewer than 24 hours), female mice that were 6 to 8 weeks of age were conditioned by sublethal irradiation with a total dose of 3 Gy. Irradiated mice received ciprofloxacin at 100 μg/mL in drinking water for the first 2 weeks. Transduced human cells were resuspended in a volume of 300 μL IMDM per mouse and injected through the lateral tail vein.

Analysis of engraftment

At 8 weeks after transplantation, bone marrow (BM) cells were harvested from recipient mice. The presence of human cells was assessed in individual mice by flow cytometry. Nonspecific antibody binding was inhibited by preincubating the cells in staining medium (PBS/4% FCS) containing 10% unconjugated human immunoglobulin G (IgG) (Endobulin; Immuno, Heidelberg, Germany) for 20 minutes at 4°C. Separate cell samples containing 5 to 20 × 105cells were then labeled for 30 minutes at 4°C with a mouse antihuman CD45 antibody conjugated to allophycocyanin (APC) or a mouse isotype–matched control monoclonal antibody (mAb). Lineage analysis of chimeric BM samples from mice receiving transplants of HOXB4- or RFP-transduced CB cells was performed by double staining with antihuman CD45–APC antibody in combination with either antihuman CD34 mAb, antihuman CD33 mAb, or antihuman CD19 mAb. The antihuman lineage-specific mAbs were conjugated to either phycoerythrin (PE) or fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC). All antibodies were purchased from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA). Dead cells were excluded from analysis with the use of propidium iodide (PI) (Sigma) uptake. For each mouse sample, 10 000 to 20 000 viable (PI−) human CD45+ cells were acquired on a FACSCalibur cytometer (BD Biosciences) and analyzed by means of the CellQuest software package (BD Biosciences). BM cells from mice that had not received transplants were used as a negative control, and human blood cells served as a positive control. Human multilineage cell engraftment in BM of mice simultanously injected with HOXB4- and RFP-transduced cells and of mice receiving cotransplants of GFP- and RFP-transduced cells, respectively, was assessed by separate staining with one of the following APC-conjugated, antihuman mAbs: CD45, CD34, CD33, or CD19.

Western blot analysis of HOXB4 expression levels

Human chronic myeloid leukemia K562 cells (ATCC [American Type Culture Collection], Manassas, VA, no. CCL-243) were transduced with RD114-pseudotyped retroviral vectors at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of less than 1 to ensure single-copy vector integration into the target cells. Transduced cells were selected either in medium containing 1 mg/mL G418 or by fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS). For detection of ectopically expressed proteins, crude cell extracts were prepared from K562 or from human CFCs derived from chimeric NOD/SCID mice that had received transplants of human cells. Then, 25 μg total protein per lane was separated via polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and subsequently blotted onto nitrocellulose membranes. Hemagglutinin-tagged HOXB4 was detected after incubation with polyclonal anti-HA antiserum (sc-805) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). Visualization of bound antibodies was performed with the appropriate horseradish peroxidase (HRP)–conjugated secondary antibody with subsequent chemiluminescence reaction (ECL) (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Freiburg, Germany). Films were scanned, and specific HAHOXB4-derived signals were quantified densitometrically by means of Openlab software (Improvision, Heidelberg, Germany). To compare HAHOXB4 protein levels in K562, 2 different underexposed films of each of 2 representative Western blots were evaluated.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± standard error (SE) unless otherwise stated. The Student t test (2-sided) was applied for paired or nonpaired samples, with equal variance assumed. Differences of P < .05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Tuning of HOXB4 expression levels using different retroviral vectors

To determine a therapeutic window for HOXB4 expression levels in human stem and progenitor cells, we constructed a series of HOXB4-coexpression vectors (Figure 1A), based on the novel 2A-strategy, which lead to 7-fold higher, equal, or 4-fold lower amounts of protein compared with those expression levels generated by the vector MSCV-HOXB4-pgk-Neo that was originally used by Humphries and colleagues16 (Figure 1A-B). In the human cell line K562 transduced with the vector FMEV-GFP2AHAHOXB4wPRE, the major fraction of HAHOXB4 protein was detected in form of the nonseparated fusion protein (Figure 1B, lane 5). However, in primary human hematopoietic cells transduced with the same vector, the uncleaved GFP2AHAHOXB4 fusion protein (62 kDa) was almost undetectable (Figure1C, lanes 3 and 5), in accord with the published separation efficiency of greater than 95%.32 Moreover, in vitro tests with primary human CB-CD34+ cells confirmed that the direct GFPHAHOXB4 fusion protein (without 2A) retains the biologic activity of HOXB4.

Retroviral vectors mediating different levels of HOXB4 expression.

(A) Schematic presentation of MSCV- and FMEV-based retroviral vectors used for HOXB4 expression in this study. The cotranslational separation activity of the 2A-sequence of foot-and-mouth disease virus (FMDV) enables concordant expression of GFP and hemagglutinin epitope–tagged (▪) HOXB4 at constant molar ratios. Pgk indicates phosphoglycerate kinase promotor; neo, neomycin resistance gene; wPRE, posttranscriptional regulatory element of the woodchuck hepatitis virus. (B) Quantification of ectopically expressed HOXB4 protein in K562 cells that were transduced with the retroviral vectors presented in panel A with the use of an MOI of less than 1. The vector MSCV-GFP31 was used as negative control (lane 2). Transduced cells were either selected with the use of G418-containing medium (lane 1) or sorted to greater than 90% GFP+ cells (lane 2-5). Crude extracts were separted by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), and HAHOXB4 proteins were detected immunologically by means of an anti-HA antibody. The relative levels of HOXB4 expression presented in panel A for each vector were determined by quantifying HAHOXB4-specific signal intensities by scanning densitometry as described in “Materials and methods.” (C) Detection of ectopic HOXB4 expression in human colony-forming cells. Crude extracts of human CFCs, which were derived from the bone marrow of NOD/SCID mice that had received transplants (experiment 2, Tables 1 and2) were treated as described in panel B. HAHOXB4 protein was detected in CFCs derived from mice that had been injected with human FMEV-HAHOXB4wPRE–transduced CD34+ cells (lane 3 and 5), but not in progenitors obtained from mice that either had received transplants of RFP-transduced CD34+ cells (lane 2) or had simultanously received injections of RFP and GFP control vector–transduced CD34+ cells (lane 4). Lane 1 (+): K562 extract corresponding to lane 5 in panel B as a positive control. Note that the GFP2AHAHOXB4 fusion protein (62 kDa; indicated by arrows) that was observed in transduced K562 cells is almost undectable in these primary human cells.

Retroviral vectors mediating different levels of HOXB4 expression.

(A) Schematic presentation of MSCV- and FMEV-based retroviral vectors used for HOXB4 expression in this study. The cotranslational separation activity of the 2A-sequence of foot-and-mouth disease virus (FMDV) enables concordant expression of GFP and hemagglutinin epitope–tagged (▪) HOXB4 at constant molar ratios. Pgk indicates phosphoglycerate kinase promotor; neo, neomycin resistance gene; wPRE, posttranscriptional regulatory element of the woodchuck hepatitis virus. (B) Quantification of ectopically expressed HOXB4 protein in K562 cells that were transduced with the retroviral vectors presented in panel A with the use of an MOI of less than 1. The vector MSCV-GFP31 was used as negative control (lane 2). Transduced cells were either selected with the use of G418-containing medium (lane 1) or sorted to greater than 90% GFP+ cells (lane 2-5). Crude extracts were separted by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), and HAHOXB4 proteins were detected immunologically by means of an anti-HA antibody. The relative levels of HOXB4 expression presented in panel A for each vector were determined by quantifying HAHOXB4-specific signal intensities by scanning densitometry as described in “Materials and methods.” (C) Detection of ectopic HOXB4 expression in human colony-forming cells. Crude extracts of human CFCs, which were derived from the bone marrow of NOD/SCID mice that had received transplants (experiment 2, Tables 1 and2) were treated as described in panel B. HAHOXB4 protein was detected in CFCs derived from mice that had been injected with human FMEV-HAHOXB4wPRE–transduced CD34+ cells (lane 3 and 5), but not in progenitors obtained from mice that either had received transplants of RFP-transduced CD34+ cells (lane 2) or had simultanously received injections of RFP and GFP control vector–transduced CD34+ cells (lane 4). Lane 1 (+): K562 extract corresponding to lane 5 in panel B as a positive control. Note that the GFP2AHAHOXB4 fusion protein (62 kDa; indicated by arrows) that was observed in transduced K562 cells is almost undectable in these primary human cells.

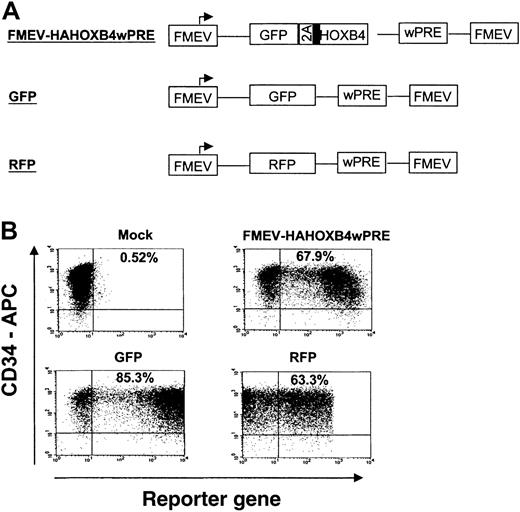

Retroviral transduction of human CB-CD34+cells

In independent experiments, purified CD34+ CB cells of 7 different CB pools were prestimulated, divided into fractions, and then separately transduced either with (1) different retroviral HOXB4-coexpression vectors carrying the GFP2AHAHOXB4 cassette (MSCV-HAHOXB4, FMEV-HAHOXB4 and FMEV-HAHOXB4wPRE, Figure 1A) or with (2) control vectors containing either the GFP or the RFP reporter gene alone (Figure2A). Gene transfer rates were determined 24 hours after transduction by FACS analysis of GFP and RFP fluorescence (examples shown in Figure 2B). A mean transduction efficiency of 57% ± 10%, 70% ± 6%, 47% ± 10%, 23% ± 5.0%, and 29% ± 4.0% was obtained with the GFP, RFP, FMEV-HAHOXB4wPRE, FMEV-HAHOXB4, and MSCV-HAHOXB4 viral supernatants, respectively.

High-efficiency gene transfer into cord blood–derived CD34+ cells.

(A) Schematic diagram of FMEV-based retroviral vectors that carry either the bicistronic 2A cassette for coexpression of GFP and HOXB4 (FMEV-HAHOXB4wPRE vector), the GFP marker alone, or the RFP reporter gene alone. All vectors contain the posttranscriptional regulatory element of the woodchuck hepatitis virus (wPRE), which enhances transgene expression. (B) Flow cytometric analysis of reporter gene expression (GFP, RFP) in human CD34+ cells 24 hours after the last infection with infectious HOXB4-, GFP-, or RFP-vector particles. Target CD34+ cells were prestimulated for 24 hours in cytokine-supplemented, serum-free medium. On 3 consecutive days, the cells were then exposed to RD114-pseudotyped retroviral particles that had been preloaded onto new retronectin-coated plates. The percentage of CD34+ cells expressing GFP or RFP is indicated in each dot-blot diagram.

High-efficiency gene transfer into cord blood–derived CD34+ cells.

(A) Schematic diagram of FMEV-based retroviral vectors that carry either the bicistronic 2A cassette for coexpression of GFP and HOXB4 (FMEV-HAHOXB4wPRE vector), the GFP marker alone, or the RFP reporter gene alone. All vectors contain the posttranscriptional regulatory element of the woodchuck hepatitis virus (wPRE), which enhances transgene expression. (B) Flow cytometric analysis of reporter gene expression (GFP, RFP) in human CD34+ cells 24 hours after the last infection with infectious HOXB4-, GFP-, or RFP-vector particles. Target CD34+ cells were prestimulated for 24 hours in cytokine-supplemented, serum-free medium. On 3 consecutive days, the cells were then exposed to RD114-pseudotyped retroviral particles that had been preloaded onto new retronectin-coated plates. The percentage of CD34+ cells expressing GFP or RFP is indicated in each dot-blot diagram.

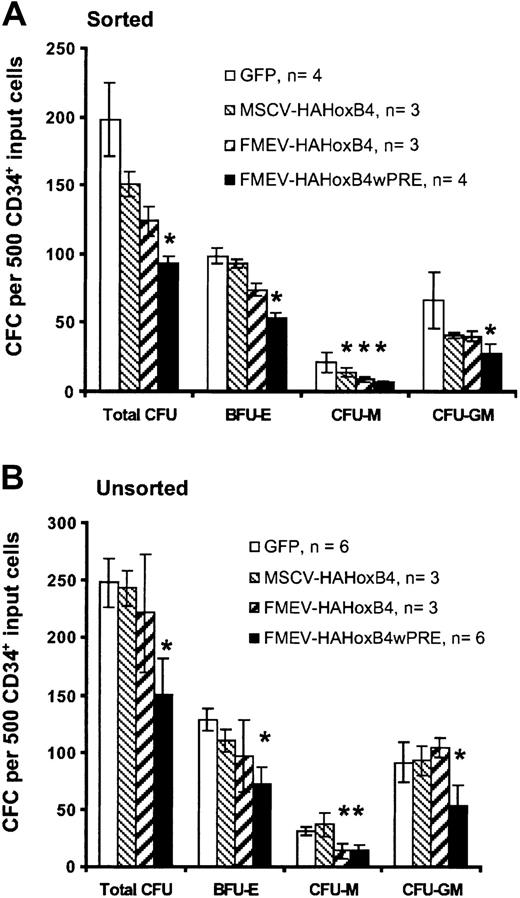

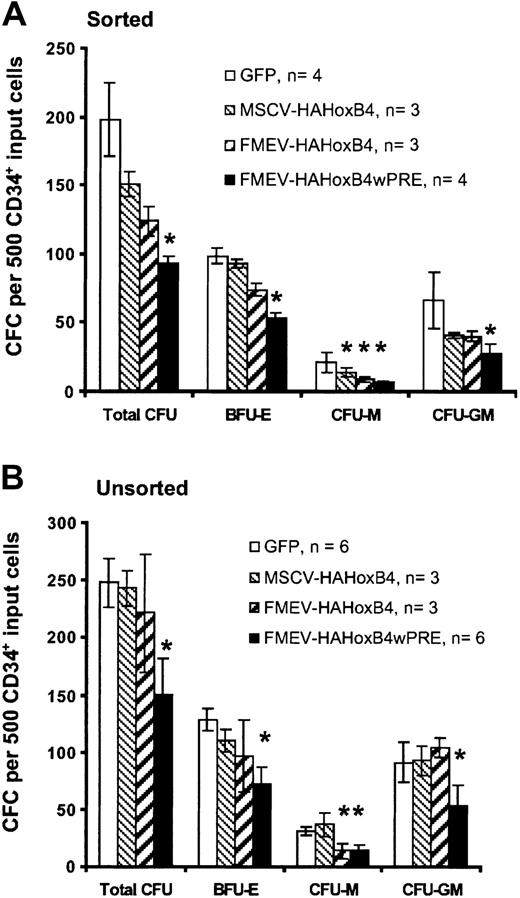

Ectopic HOXB4 expression blocks progenitor cell–derived colony formation in vitro

To determine whether enforced HOXB4 expression affects the formation of human myeloid and erythroid progenitor cells, standard methylcellusose cultures were performed 24 hours after transduction either with purified HOXB4-expressing cells isolated by flow cytometric sorting based on GFP expression (sorted; Figure3A) or without prior selection of HOXB4 and GFP control vector–transduced cells (unsorted; Figure 3B). The 2 assays yielded similar results. In cultures with purified HOXB4-expressing cells, the total number of colony-forming cells declined steadily in a dose-dependent manner compared with cultures with purified cells expressing the control GFP vector: 76% (MSCV-HAHOXB4), 63% (FMEV-HAHOXB4), and 47% (FMEV-HAHOXB4wPRE) of the GFP vector control population. Even at a low level of ectopic HOXB4 (MSCV-HAHOXB4), the number of macrophage colony-forming unit (CFU-M) and granulocyte-macrophage CFU (CFU-GM) colonies was reduced (67% and 62% of control, respectively), whereas the mean number of erythroid burst-forming unit (BFU-E) colonies was not significantly altered. At 4-fold higher (FMEV-HAHOXB4) and 28-fold higher (FMEV-HAHOXB4wPRE) levels of HOXB4, the formation of BFU-E colonies was also inhibited (75% and 54% of control, respectively), and the generation of CFU-M and CFU-GM colonies was further reduced. However, the number of CFU-G and granulocyte-macrophage-erythroid-mixed CFU (CFU-GMEM) colonies was not altered by ectopic HOXB4 expression, irrespective of the vector used (data not shown).

Effect of high levels of ectopic HOXB4 in human CD34+ cells on the number of hematopoietic progenitor cells.

High levels of ectopic HOXB4 in human CD34+ cells reduce the number of hematopoietic progenitor cells in vitro. This figure shows the frequency and distribution of colonies derived from CD34+ cells transduced with different HOXB4 vector contructs and the GFP control vector. Flow cytometrically sorted GFP+ cells (A) and unsorted transduced cells (B) for each vector were cultured in duplicate in methylcellulose-based media. Data are displayed as the mean ± standard error (bar) number of colonies per 500 CD34+ input cells. Statistical analysis was carried out by means of the Student t test (paired; 2-sided): *P < .05.

Effect of high levels of ectopic HOXB4 in human CD34+ cells on the number of hematopoietic progenitor cells.

High levels of ectopic HOXB4 in human CD34+ cells reduce the number of hematopoietic progenitor cells in vitro. This figure shows the frequency and distribution of colonies derived from CD34+ cells transduced with different HOXB4 vector contructs and the GFP control vector. Flow cytometrically sorted GFP+ cells (A) and unsorted transduced cells (B) for each vector were cultured in duplicate in methylcellulose-based media. Data are displayed as the mean ± standard error (bar) number of colonies per 500 CD34+ input cells. Statistical analysis was carried out by means of the Student t test (paired; 2-sided): *P < .05.

To test the impact of the unseparated GFP2AHAHOXB4 fusion protein detected in K562 cells and of the HA tag on the biologic activity of HOXB4, colony assays were performed with purified cells expressing either the direct GFPHAHOXB4 fusion protein (without 2A; FMEV-GFPHAHOXB4wPRE) or a bicistronic cassette encoding unmodified or HA-tagged HOXB4 together with GFP (FMEV-HOXB4-IRES-GFPwPRE, FMEV-HAHOXB4-IRES-GFPwPRE, respectively). The overexpression of the GFPHAHOXB4 fusion protein also led to a significant reduction in BFU-E, CFU-M, and CFU-GM colony numbers (data not shown). Cells expressing either one of the HOXB4-IRES-GFP cassettes showed a nearly complete loss of progenitor-derived colony formation (10% of control) compared with purified cells expressing the GFP control vector (data not shown). These results demonstrate that the HA tag did not alter the biologic activity of HOXB4. In addition, these results are consistent with data showing that, compared with the FMEV-HAHOXB4wPRE vector, both HOXB4-IRES-GFP vector constructs mediate about 3-fold higher levels of HOXB4 expression in K562 cells (data not shown).

Enforced HOXB4 expression in human CD34+ cells leads to impaired proliferation and myeloid differentiation in vitro

To more closely analyze the effect of ectopic HOXB4 on differentiaton of myeloid progenitor cells, liquid in vitro granulomonocytic differentiation cultures were set up, and myeloid differentiation was analyzed by cell surface staining for the expression, 1 week later, of CD33, CD14, and CD15. Cultures started without prior selection of HOXB4 or control GFP vector–transduced cells yielded, on average, similar total numbers of progeny cells (data not shown). However, sorted cells expressing either the vector FMEV-HAHOXB4wPRE or FMEV-HAHOXB4 produced, on average, a 2-fold lower number of progeny cells as purified cells expressing the control GFP vector. In contrast, purified MSCV-HAHOXB4–expressing cells generated a similar number of progeny cells as control cells (Figure4A). Accordingly, a significant reduction (51%) in the proportion of GFP+ (transduced) cells compared with the proportion at initiation of differentiation occurred in cultures with nonpurified FMEV-HAHOXB4wPRE–transduced cells (26.6% ± 4.2% versus 54.1% ± 7.0%; n = 6;P < .01) (Figure 4B). A decline in GFP+ cells (23%) was also observed among FMEV-HAHOXB4–transduced cultures. In contrast, the initial input ratio of transduced to nontransduced cells was maintained throughout induction of myeloid differentiation in cultures with nonpurified GFP vector–transduced cells. An increase in the proportion of GFP+ cells was seen in MSCV-HAHOXB4–transduced cultures, but this was statistically not significant (Figure 4B).

Effect of high ectopic HOXB4 expression in human CD34+ cells on myeloid differentiation.

High ectopic HOXB4 expression in human CD34+ cells impairs myeloid differentiation in vitro. Following transduction with different HOXB4 vector contructs and the GFP control vector, FACS-sorted GFP+ cells (A,C) and unsorted transduced cells (B) for each vector were cultured for 7 days in liquid medium containing a myeloid differentiation–inducing cytokine cocktail. Thereafter, the cells were counted, and reporter gene expression was determined after staining cell samples either with PE-labeled antihuman CD33 antibodies alone or with a combination of antihuman CD14–APC/CD15–PE antibodies. (A) Comparison of the absolute number of hematopoietic cells generated from 30 000 GFP+-sorted input cells. (B) Percentage of GFP+ cells at the day of harvest compared with that at initiation of differentiation (input) in cultures with unsorted transduced cells. (C) Percentage of cells expressing myeloid-specific cell surface markers (CD33, CD14, and CD15) in cultures initiated with FACS-purified GFP+ cells. Results are shown as mean ± standard error (bar) values. The Student t test (paired; 2-sided) was applied for statistical analysis. *P < .05.

Effect of high ectopic HOXB4 expression in human CD34+ cells on myeloid differentiation.

High ectopic HOXB4 expression in human CD34+ cells impairs myeloid differentiation in vitro. Following transduction with different HOXB4 vector contructs and the GFP control vector, FACS-sorted GFP+ cells (A,C) and unsorted transduced cells (B) for each vector were cultured for 7 days in liquid medium containing a myeloid differentiation–inducing cytokine cocktail. Thereafter, the cells were counted, and reporter gene expression was determined after staining cell samples either with PE-labeled antihuman CD33 antibodies alone or with a combination of antihuman CD14–APC/CD15–PE antibodies. (A) Comparison of the absolute number of hematopoietic cells generated from 30 000 GFP+-sorted input cells. (B) Percentage of GFP+ cells at the day of harvest compared with that at initiation of differentiation (input) in cultures with unsorted transduced cells. (C) Percentage of cells expressing myeloid-specific cell surface markers (CD33, CD14, and CD15) in cultures initiated with FACS-purified GFP+ cells. Results are shown as mean ± standard error (bar) values. The Student t test (paired; 2-sided) was applied for statistical analysis. *P < .05.

The percentage of CD33+ cells was significantly increased (6.1- to 6.7-fold) in cultures with sorted cells expressing either one of the different HOXB4 vector constructs as compared with cells expressing the GFP control vector (Figure 4C). Similarly, the percentage of CD15+ cells was on average 3.5- to 5.7-fold higher in HOXB4 cultures than in control cultures. In contrast, no significant difference in the percentage of CD14+ cells was seen between HOXB4 and GFP control vector–transduced cells. Similar data were obtained with cultures initiated without prior preselection of HOXB4 or control GFP vector–transduced cells, by gating on the fraction of GFP+ cells (data not shown). The ratio of CD14+ to CD15+ cells in HOXB4 cultures was thus drastically shifted in favor of CD15+ cells compared with control cultures. (P = .04; Figure 4C), suggesting that even low levels of ectopic HOXB4 drive GM-precursor cells into granulocytic differentiation.

Together, these in vitro results show that enforced HOXB4 overexpression impairs the proliferation and differentiation of human myeloid and erythoid progenitor cells in a dose-dependent manner. Although we observed a signficantly reduced number of CFU-M colonies and an enhanced granulocytic differentiation already at low levels of ectopic HOXB4, a statistically significant further reduction in the formation of CFU-GM and BFU-E colonies and in proliferative activity was seen only in cells expressing the highest level of ectopic HOXB4.

HOXB4 overexpression in primitive human cells confers a selective growth advantage in vivo

To investigate whether ectopic expression of HOXB4 also affects the proliferation and differentiation of primitive CB-CD34+cells, which are able to home to and engraft the marrow of NOD/SCID mice, equal numbers of FMEV-HAHOXB4wPRE (hereafter referred to as HOXB4)–, RFP-, and mock-transduced progeny cells were transplanted into groups of 3 to 5 mice. At 8 weeks later, FACS analysis of the bone marrow cells revealed human lymphomyeloid engraftment in all mice that had received transplants. The results of the NOD/SCID mouse experiments are summarized in Table1. In both independent experiments, the average human cell engraftment (percentage CD45+) was comparable in mice injected individually with either HOXB4-, RFP-, or mock-transduced cord blood cells. In the first experiment, HOXB4- and RFP-recipient mice displayed comparable mean frequencies of transduced CD34+ cells (Table 1). However, the average proportion of transduced CD34+ cells (36.1% ± 12.1%; n = 4) detected in these HOXB4 mice (experiment no. 1) reflected the original frequency of HOXB4-transduced CD34+ cells (33.3%) determined for the initial transplantation cell inoculum; in 2 of 4 mice, the proportion of HOXB4-expressing CD34+cells was increased almost 2-fold (52.7% and 61.1% HOXB4+CD34+cells). In the marrow of HOXB4 mice from the second transplantation experiment, the mean proportion of HOXB4-transduced CD34+ cells (80.2% ± 9.2%; n = 4) was even higher than at the time of transplantation (67.9%). In contrast, the mean proportion of RFP+CD34+ control cells (Table 1) detected in both groups of RFP mice was markedly lower (greater than 40%) than the frequency of RFP+CD34+ cells in the initial transplants.

Moreover, in the GFP+-gated population of mice receiving transplants of HOXB4-transduced cells, the mean frequeny of CD34+ cells was 2-fold higher than the frequency in the GFP− (nontransduced) population of human cells (26.5% ± 5.3% versus 14.6% ± 2.6%; n = 8;P = .01). Yet a similar mean frequency of CD34+ cells was seen in both the RFP+ and the RFP− cell compartments in mice given control vector–transduced cells (16.6% ± 5.3% versus 10.4% ± 2.5%; n = 8; P = .1). Consistent with these findings, HOXB4-recipient mice also showed a 2.7-fold increase in the mean total proportion of CD34+ cells as compared with the control RFP mice (CD34+CD45+: 19.0% ± 4.5% versus 6.9% ± 1.2%; n = 8; P = .02).

Collectively, these results thus show that CD34+ cells overexpressing HOXB4 have a pronounced selective growth advantage in vivo.

Competitive repopulation assays show the selective growth advantage of HOXB4-transduced CD34+ cells

Furthermore, we directly compared HOXB4-transduced and GFP–control vector–transduced cells in their ability to engraft and repopulate the marrow of NOD/SCID mice in competition with RFP-transduced cells (Table 2). Therefore, the equivalent numbers of progenies from 105input CD34+ cells transduced with either HOXB4 or GFP control virus were each mixed with equal numbers of RFP-transduced progeny cells and then injected into mice. This resulted in cell transplants containing a 1:2 (experiment no. 1) or 1:1 (experiment no. 2) ratio of HOXB4- to RFP-transduced cells, and a 1:1 (no. 1) or 1.4:1 (no. 2) ratio in the corresponding GFP versus RFP control groups. In further support of the previous conclusion, the engraftment of HOXB4-expressing (GFP+) cells was clearly superior to RFP-transduced cells in competitive transplantation groups (HOXB4 versus RFP group). Although the number of HOXB4+CD34+ cells was about 2-fold lower than the number of RFP+CD34+ cells initially coinjected in the first experiment, the proportion of CD34+ cells expressing HOXB4 (GFP+) after 8 weeks was on average 8.6-fold (range, 3.6- to 28.5-fold) higher than the proportion of CD34+ cells expressing RFP (45.8% ± 10.7% GFP+CD34+ versus 7.6% ± 2.1% RFP+CD34+; n = 6;P = .01) (Table 2). Representative FACS profiles are shown in Figure 5.

Growth advantage in human CD34+ cells overexpressing HOXB4.

Human CD34+ cells overexpressing HOXB4 have a marked competitive growth advantage in NOD/SCID mice receiving transplants. (A) FACS analysis of human CD34+ cells expressing either GFP (top) or RFP (bottom) in marrow samples from mice that had received transplants with equal initial cell inoculums containing either HOXB4 (FMEV-HAHOXB4wPRE)– and RFP-transduced cells in a 1:2 ratio (HOXB4 versus RFP), or GFP- and RFP-transduced cells in a 1:1 ratio (GFP versus RFP). (B) In all mice receiving competitive transplants of HOXB4 versus RFP, HOXB4+(GFP+)CD34+ cells clearly dominated over RFP+CD34+ cells 8 weeks after transplantation. In contrast, in 3 of 6 mice of the GFP versus the RFP control group, RFP+CD34+cells predominated over GFP+CD34+ cells, whereas in the other 3 mice we observed the reverse.

Growth advantage in human CD34+ cells overexpressing HOXB4.

Human CD34+ cells overexpressing HOXB4 have a marked competitive growth advantage in NOD/SCID mice receiving transplants. (A) FACS analysis of human CD34+ cells expressing either GFP (top) or RFP (bottom) in marrow samples from mice that had received transplants with equal initial cell inoculums containing either HOXB4 (FMEV-HAHOXB4wPRE)– and RFP-transduced cells in a 1:2 ratio (HOXB4 versus RFP), or GFP- and RFP-transduced cells in a 1:1 ratio (GFP versus RFP). (B) In all mice receiving competitive transplants of HOXB4 versus RFP, HOXB4+(GFP+)CD34+ cells clearly dominated over RFP+CD34+ cells 8 weeks after transplantation. In contrast, in 3 of 6 mice of the GFP versus the RFP control group, RFP+CD34+cells predominated over GFP+CD34+ cells, whereas in the other 3 mice we observed the reverse.

In contrast, in the GFP versus the RFP control group, the mean frequencies of GFP+CD34+ cells and of RFP+CD34+ cells were not significantly different (22.8% ± 4.2% GFP+CD34+ versus 35.5% ± 10.0% RFP+CD34+;P = .37). Thus, they reflect the original 1:1 input ratio of GFP- to RFP-transduced cells. These data indicate that the 2 marker genes had either no or similar effects on engraftment, proliferation, and differentiation. Accordingly, in 3 of 6 mice of the GFP versus the RFP control group, GFP+CD34+cells dominated over RFP+CD34+, whereas in the other 3 mice we noted the reverse (Figure 5B). These results were confirmed in a second, independent competitive repopulation experiment (Table 2).

In conclusion, our results—obtained with mice receiving transplants of HOXB4-transduced CD34+ cells either alone or in competition with control vector–transduced cells—provide clear evidence that human CD34+ cells overexpressing HOXB4 display a marked competitive repopulation advantage in vivo, similar to what has been described for murine stem cells that ectopically expressed HOXB4 at lower levels.18

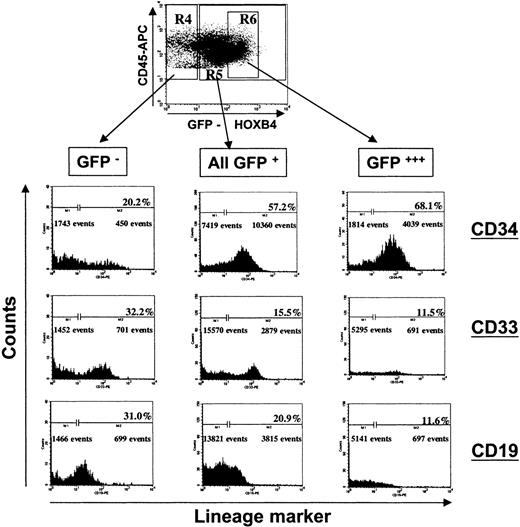

High ectopic HOXB4 expression impairs lymphoid and myeloid differentiation in vivo

Immunophenotyping of chimeric bone marrow samples of mice injected individually either with HOXB4- or RFP-transduced CD34+ cells for human lymphoid (CD45+CD19+) and myeloid (CD45+CD33+) cells, demonstrated that ectopic HOXB4 expression in NOD/SCID repopulating cells impaired B-cell development and myeloid differentiation in vivo. When we combined the proportions of CD19+ and CD33+ cells—the 2 main populations of differentiated human cells in NOD/SCID mice—the mean frequency of differentiated cells in the GFP+ population of all 8 HOXB4 mice was significantly lower compared with the frequency in the GFP− cell compartment (P = .002; Table3). In contrast, in the RFP control group, the proportion of differentiated cells was not significantly different in the RFP+ and the RFP− cell compartment (P = .32; Table 3). In 5 of 8 RFP control mice, the proportion of differentiated cells in the RFP+ compartment was higher than in the RFP− population, whereas we observed the opposite in the other 3 mice. A separate analysis of the lymphoid and myeloid cell populations, as illustrated in Figure6 for one representative mouse, showed that the mean frequency of CD19+ cells in the GFP+ population of HOXB4 mice was significantly reduced relative to the average proportion observed in the nontransduced population (Table 3). In particular, we observed decreased proportions of B-lymphoid cells in the fraction of human leukocytes that expressed HOXB4 at very high levels (Figure 6, right panel), while the frequency of CD34+ cells concurrently increased.

Impaired lymphomyeloid differentiation of human long-term repopulating cells overexpressing HOXB4 in NOD/SCID mice.

The FACS profile of the BM of a representative mouse receiving a transplant of HOXB4 (FMEV-HAHOXB4wPRE)–transduced cells (67.9% GFP+/CD34+ cells) is shown at 8 weeks after cell injection. Forward-scatter/side-scatter properties and propidium iodide staining were used to exclude dead cells from analysis. Human CD45+ cells were gated and analyzed for GFP marker gene expression. Subsequently, the proportion of primitive human cells (CD34+), myeloid cells (CD33+), and B-lymphoid cells (CD19+) were determined in the population of nontransduced human cells (R4: GFP−/CD45+), in the total population of HOXB4-transduced cells (R5: GFP+/CD45+), and in the subpopulation of transduced cells expressing HOXB4 at very high levels (R6: GFP+++/CD45+). The frequency of lymphoid and myeloid differentiated cells was significantly lower in the compartment of HOXB4-transduced cells (all GFP+, central histogram panel) than in the nontransduced cell population (GFP−, left panel), whereas the frequency of primitive CD34+ cells was concurrently increased in the population of HOXB4-expressing cells. In particular, this altered lineage contribution was enhanced in the transduced cells expressing HOXB4 at very high levels (right panel).

Impaired lymphomyeloid differentiation of human long-term repopulating cells overexpressing HOXB4 in NOD/SCID mice.

The FACS profile of the BM of a representative mouse receiving a transplant of HOXB4 (FMEV-HAHOXB4wPRE)–transduced cells (67.9% GFP+/CD34+ cells) is shown at 8 weeks after cell injection. Forward-scatter/side-scatter properties and propidium iodide staining were used to exclude dead cells from analysis. Human CD45+ cells were gated and analyzed for GFP marker gene expression. Subsequently, the proportion of primitive human cells (CD34+), myeloid cells (CD33+), and B-lymphoid cells (CD19+) were determined in the population of nontransduced human cells (R4: GFP−/CD45+), in the total population of HOXB4-transduced cells (R5: GFP+/CD45+), and in the subpopulation of transduced cells expressing HOXB4 at very high levels (R6: GFP+++/CD45+). The frequency of lymphoid and myeloid differentiated cells was significantly lower in the compartment of HOXB4-transduced cells (all GFP+, central histogram panel) than in the nontransduced cell population (GFP−, left panel), whereas the frequency of primitive CD34+ cells was concurrently increased in the population of HOXB4-expressing cells. In particular, this altered lineage contribution was enhanced in the transduced cells expressing HOXB4 at very high levels (right panel).

In line with these results, in half of the HOXB4 mice, the mean frequency of CD33+ cells in the total GFP+population was 2.7-fold lower compared with the frequency in the GFP− compartment (8.3% ± 1.9% versus 22.3% ± 4.5%). In contrast, the mean frequencies of CD19+ cells and of CD33+ cells in the control RFP mice were not significantly different among the corresponding RFP+ and RFP− cell populations (P = .34 and P = .16, respectively; Table 3). In concordance with the greatly diminished proportion of CD33+ cells already described, the frequency of human CFCs was profoundly lower in HOX versus RFP mice (n = 5) in comparison with the mean CFC frequency of 6 mice receiving competitive transplants of GFP+ versus RFP+ cells (86 ± 24 versus 335 ± 68 CFCs per 105 CD45+ cells;P = .01). In particular, the mean frequencies of CFU-GM and of BFU-E progenitor cells were severely reduced compared with the control GFP versus RFP mice (34 ± 11 versus 140 ± 28, and 23 ± 8 versus 101 ± 27 per 105 CD45+cells; P < .01 and P < .03, respectively).

Finally, the levels of HOXB4 expression in the CD45+ and CD19+ cell populations of these competitively engrafted HOXB4 versus RFP mice were significantly lower than in the corresponding populations of primitive CD34+ cells as determined by comparison of the mean fluorescence intensities (MFIs) of the GFP marker gene (69 ± 9 versus 106 ± 13, n = 7,P < .001, and 60 ± 6 versus 106 ± 13, n = 7,P < .01, respectively). Histograms displaying GFP marker gene expression in CD34+ and CD45+ cells from 2 representative HOX versus RFP mice are shown in Figure7. In contrast, the mean GFP fluorescence intensities of CD45+, CD19+, and CD34+ cells were not different in GFP versus RFP control mice (1691 ± 697 versus 1502 ± 485, n = 6, and 1437 ± 463 versus 1502 ± 485, n = 6, respectively).

Differences in the levels of HOXB4 expression between primitive CD34+ and differentiated human cells.

Histograms displaying GFP marker expression in human CD34+and CD45+ cells from 2 of 7 representative HOXB4 versus RFP mice (mice 1 and 2) and from 2 of 6 GFP versus RFP mice (mice 3 and 4) are shown. BM cells were stained with human-specific mAbs against the panleukocyte marker CD45 or the primitive cell marker CD34. Propidium iodide uptake was used for gating viable cells in the first step. Cells positive for human CD34 and CD45 were then gated and analyzed for GFP expression. The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) values for each GFP+ population are indicated in the histograms. In the HOXB4 versus RFP group of mice, differences between primitive CD34+ and either CD45+ or CD19+cells (not shown) in the MFI of GFP were significant (P < .001 and P < .01, respectively).

Differences in the levels of HOXB4 expression between primitive CD34+ and differentiated human cells.

Histograms displaying GFP marker expression in human CD34+and CD45+ cells from 2 of 7 representative HOXB4 versus RFP mice (mice 1 and 2) and from 2 of 6 GFP versus RFP mice (mice 3 and 4) are shown. BM cells were stained with human-specific mAbs against the panleukocyte marker CD45 or the primitive cell marker CD34. Propidium iodide uptake was used for gating viable cells in the first step. Cells positive for human CD34 and CD45 were then gated and analyzed for GFP expression. The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) values for each GFP+ population are indicated in the histograms. In the HOXB4 versus RFP group of mice, differences between primitive CD34+ and either CD45+ or CD19+cells (not shown) in the MFI of GFP were significant (P < .001 and P < .01, respectively).

Taken together, these results argue strongly for the existence of a critical maximal level of HOXB4 expression, above which differentiation into some lineages is blocked.

Discussion

An increasing number of reports indicate HOX homeobox genes as key regulators that control the balance between self-renewal and commitment to differentiation during cell division of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSCs/HPCs). Ectopic expression of HOXB4 has been shown to mediate a rapid amplification of murine HSCs in vivo without perturbation of lymphomyeloid differentiation.16-18

Consistent with the previous reports in the mouse model, we provide clear evidence in the present study that enforced high levels of HOXB4 expression in purified human CD34+ cells confer a profound competitive repopulation advantage on transduced cells and concurrently promote an amplification of the primitive CD34+ cell compartment in vivo. However, our data also show that high levels of HOXB4 overexpression markedly impair the differentiation program of early myeloerythroid and lymphoid progenitor cells. In vitro and in vivo, myeloid and erythroid colony formation of FMEV-HAHOXB4wPRE–transduced cells was significantly reduced. Furthermore, the in vivo generation of B cells was also impaired, suggesting that HOXB4 overexpression may interfere with the normal differentiation program of multipotent progenitor cells. B-lymphoid and myeloid cells, which were recovered from the chimeric marrow of HOXB4 mice, expressed HOXB4 only at low levels, whereas its expression was substantially higher in the CD34+ subpopulation, as determined by comparing the fluorescence intensities of the GFP marker gene. Such an analysis was possible owing to the stringency of the 2A-linkage strategy.31 In contrast, both lymphomyeloid cells and immature CD34+ cells generated in vivo in control mice displayed similar levels of GFP reporter gene expression.

These results suggest a specific and strictly dose-dependent effect of HOXB4 on blood cell differentiation and also argue against either a general, nonspecific effect of high coexpression levels of the GFP reporter gene or an HOXB4-specific down-regulation of viral LTR-mediated transgene expression in differentiated cells. In conformation, adenoviral vector–enforced high levels of unmodified HOXB4 in CB CD34+ cells also lead to reduced formation of myeloid and erythroid progenitor cells in vitro (A. Brun, e-mail communication, June 6, 2002). Consistent with the existence of a threshold level critical for a differentiation block, Humphries and colleagues18 did not observe an impaired differentiation of murine HSCs/HPCs using a retroviral vector that mediates ectopic HOXB4 expression that is significantly lower than the levels mediated by the vector used in our study (Figure 1). Confirming their results, we show that B-lymphoid and myeloid progeny cells of HOXB4-transduced human CD34+ cells express HOXB4 only at low levels. In agreement with these observations, previous studies showed that HOXB4 and numerous other members of theHOXA and HOXB gene cluster are preferentially expressed in primitive human CD34+ cells, while their expression is down-regulated to low or undetectable levels in mature blood cells of all lineages.36 Together, these data demonstrate that HOXB4 acts particularly on primitive multipotent human hematopoietic cells and that down-regulation of its expression below a critical level seems necessary for in vivo differentiation. Ectopic overexpression of most HOX genes(HOXA5, A9, A10, B3, B7, B8) resulted in multiple alterations of normal murine and human hematopoiesis in vitro and in vivo: uncontrolled proliferation of different types of myeloid progenitors, impeded generation of unilineage macrophage and pre-B progenitor cells, blockage of differentiation of certain T-cell subsets, and inhibition of erythropoiesis.19-26Thus, a tight stage-specific regulation of HOXA andHOXB gene expression seems to be critical for normal progenitor development.

Considering the observed in vivo amplification of HOXB4-expressing CD34+ cells in NOD/SCID mice, and the high levels of endogenous HOXB4 expression in the compartment of human CD34+ cells, it is tempting to argue that high levels of HOXB4 may promote stem cell self-renewal by suppressing multiple differentiation pathways while maintaining proliferation in response to early-acting cytokines. Consequently, down-regulation of HOXB4 expression would enable stem cells to differentiate into precursors of various blood cell lineages, but at the expense of a reduced self-renewal capacity. Consistent with this hypothesis, Calvo et al37 recently demonstrated that HOXA9 and MEIS1, another homeobox protein, cooperatively promote self-renewal progenitor cell divisions by blocking complementary, independent differentiation pathways and enhancing the proliferative response to non–lineage-specific cytokines such as SCF.

Intriguingly similar to our results, ectopic overexpession of the transcription factor GATA-2 in primitive mouse hematopoietic cells (SCA-1+Lin− fraction) also markedly blocked the formation of myeloerythroid progenitor cells in vitro and in vivo in a dose-dependent manner.38 Like HOXB4, GATA-2 is highly expressed in the murine stem cell fraction, but is expressed only at very low levels in differentiating and mature cell subsets.39 However, in contrast to the findings of HOXB4 overexpression in murine HSCs and human SCID-repopulating cells, GATA-2 overexpression also blocked the amplification of pluripotent repopulating cells in vivo. GATA-2–expressing murine stem cells were completely outcompeted by nontransduced cells in the multilineage reconstitution of mice that had received transplants.38Thus, GATA-2 seems to act as a negative regulator preventing a pool of quiescent stem cell clones to participate in hematopoiesis, while HOXB4 may guarantee the self-renewal amplification of stem cells once they have become activated.

In summary, our data demonstrate that high levels of HOXB4 expression in human CD34+ cells seem to be a prerequisite for keeping activated stem cells in an undifferentiated state, whereas down-regulation is necessary to permit subsequent differentiation. Furthermore, these results set a paradigm for the need to precisely define a therapeutic expression level of genes introduced into human stem cells to extend their clinical utility.

We thank Carol Stocking and Ursula Just for critically reviewing the manuscript and for helpful suggestions. We also gratefully acknowledge the support of the animal facility team of the Heinrich-Pette-Institute.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, October 24, 2002; DOI 10.1182/blood-2002-03-0767.

Supported by the Deutsche Krebshilfe (W.O.; 10-1763-OS5); by the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (W.O.; BMBF 0312173 via CellTec); and in part by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (E.W.; WI 1995/1-1). The Heinrich-Pette-Institute is financially supported by the Bundesministerium für Gesundheit and by the Freie und Hansestadt Hamburg, Germany.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Wolfram Ostertag, Department of Cell and Virus Genetics, Heinrich-Pette-Institute, Martinistrasse 52, D-20251 Hamburg, Germany; e-mail:ostertag@hpi.uni-hamburg.de.