Abstract

Between 30% and 50% of patients with advanced-stage anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (ALCL) harbor the balanced chromosomal rearrangement t(2;5)(p23;q35), which results in the generation of the fusion protein nucleophosmin-anaplastic lymphoma kinase (NPM-ALK). To further study survival signaling by NPMALK, we generated Ba/F3 cell lines with either inducible or constitutive expression of NPM-ALK and examined the regulation of the AKT target FOXO3a. We hypothesized that NPM-ALK signaling through phosphoinositol 3-kinase (PI 3-kinase) and AKT would regulate FOXO3a, a member of the forkhead family of transcription factors, thereby stimulating proliferation and blocking programmed cell death in NPM-ALK-transformed cells. In Ba/F3 cells with induced or constitutive expression of NPM-ALK, concomitant AKT activation and phosphorylation of its substrate, FOXO3a, was observed. In addition, transient expression of NPM-ALK in U-20S cells inhibited FOXO3a-mediated transactivation of reporter gene expression. Furthermore, NPM-ALK-induced FOXO3a phosphorylation in Ba/F3 cells resulted in nuclear exclusion of this transcriptional regulator, up-regulation of cyclin D2 expression, and down-regulation of p27kip1 and Bim-1 expression. NPMALK reversal of proliferation arrest and of p27kip1 induction was dependent on the phosphorylation of FOXO3a. Thus, FOXO3a is a barrier to hematopoietic transformation that is overcome by phosphorylation and cytoplasmic relocalization induced by the expression of NPM-ALK. (Blood. 2004;103:4622-4629)

Introduction

Anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (ALCL) is a malignancy of T-cell origin that is typically associated with presentation at an advanced stage of disease (stage III or IV) and with extranodal sites of involvement.1 The search for molecular targets in the pathogenesis of hematopoietic neoplasms can inform the design of novel therapeutic strategies. The clinical success of the ABL tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib mesylate (Gleevec) in the treatment of BCR/ABL-positive chronic myelogenous leukemia has emerged as a paradigm of antineoplastic therapy directed toward a tyrosine kinase.2,3 Thus, a detailed understanding of the molecular pathogenesis of ALCL might guide the development of improved therapies for this lymphoma.

Between 30% and 50% of patients with primary systemic ALCL and 75% of patients with ALK-positive ALCL harbor a balanced chromosomal rearrangement, t(2;5) (p23;q35), which results in generation of the fusion protein nucleophosmin-anaplastic lymphoma kinase (NPM-ALK).1,4-6 The amino-terminal portion of the fusion protein is encoded by the nucleophosmin gene (NPM), the product of which is a highly conserved, ubiquitously expressed RNA-binding nucleolar phosphoprotein that mediates nucleolar-cytoplasmic trafficking of ribonucleoproteins7,8 and centrosome duplication.9 The carboxy-terminal portion of the NPMALK fusion protein is encoded by the anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK), which is a member of the insulin receptor family of protein tyrosine kinases. Expression of the native ALK protein is limited to cells of the central nervous system.6,10 The NPM-ALK fusion protein acts as a constitutively activated tyrosine kinase by means of oligomerization of the NPM domain and autophosphorylation-induced activation of the ALK domain.

Inappropriate expression and activation of the fusion kinase in the lymphoid compartment is responsible for the pathogenesis of some forms of ALCL. Functional consequences of NPM-ALK have been demonstrated in cell culture and murine whole animal models. NPM-ALK has been shown to be capable of transforming rodent fibroblasts11 and primary murine bone marrow cells.12 NPM-ALK expression induces B-cell lymphomas in a murine bone marrow transplantation model13 and induces T-lineage lymphomas and plasma cell neoplasms in transgenic mice expressing NPMALK under the control of the CD4 promoter.14 Expression of the NPM-ALK fusion kinase in the Ba/F3 murine hematopoietic cell line confers interleukin-3 (IL-3)-independent survival and proliferation. Although the mechanisms of NPM-ALK-mediated oncogenesis are incompletely understood, previous reports have demonstrated that NPM-ALK activates phospholipase C-γ (PLC-γ) and the signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) and STAT5 regulators.11,15-17

In addition to activating these signaling regulators, NPM-ALK has been shown to bind and activate phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI 3-kinase), which, in turn activates the downstream target AKT/PKB.12,18 It has been established that activation of the PI 3-kinase/AKT pathway plays a role in survival signaling by phosphorylating, and thus inactivating, the Bcl2 family member BAD and the caspase-9 protease, and both events function to mitigate programmed cell death.19-21 Phosphorylating BAD leads to the prevention of apoptosis through a mechanism that involves the selective association of the phosphorylated forms of BAD with 14-3-3 protein isoforms. The 14-3-3 protein traps BAD in an inactive complex, and Bcl-2 is liberated to promote cell survival. Overexpression of NPM-ALK has been shown to partially block apoptosis induced by overexpression of BAD.12

Although the role of AKT in phosphorylating cytoplasmic signaling targets is now well established, the finding that AKT can translocate to the nucleus indicates that its signaling properties are considerably more complex.22 Nuclear localization provides the opportunity for AKT to directly phosphorylate and regulate targets in this subcellular compartment. Indeed, this is the case with the members of the forkhead family of transcription factors, which have been shown to be direct targets of AKT.23-25 The 3 members of human forkhead family—FOXO1 (FKHR), FOXO3a (FKHRL1), and AFX (FOXO4)—represent mammalian orthologues of a Caenorhabditis elegans transcription factor, DAF-16, which regulates longevity and responses to environmental stress.26 Brunet et al23 showed that in the presence of growth factors (fetal bovine serum, insulin-like growth factor-1 [IGF-1]) or with expression of a constitutively active form of AKT, FOXO3a is hyperphosphorylated, associates with the cytoplasmic scaffolding protein 14-3-3, and is retained in the cytoplasm.27

The FOXO3a protein contains 3 regulatory phosphorylation sites: Thr32, Ser253, and Ser315. Each of these sites has been shown to be phosphorylated by AKT.23 In addition, serum and glucocorticoid-induced kinase (SGK) has been demonstrated to mediate Ser315 and Thr32 phosphorylation.28 A mutant of FOXO3a that contains alanine substitutions at all 3 sites is neither phosphorylated nor relocalized to the cytoplasm under conditions of PI 3-kinase and AKT activation.23 Thus, growth factor-stimulated activation of the PI 3-kinase/AKT pathway induces phosphorylation of FOXO3a, its cytoplasmic sequestration by means of binding to the 14-3-3 protein, and prevention of FOXO3a-dependent transcriptional regulation. Expression of activated AKT has been reported to trigger proteosome-dependent degradation of the FOXO3a protein.29

FOXO3a is known to interface with multiple targets. Nuclear exclusion of FOXO3a prevents it from inducing expression of a series of proapoptotic and cell cycle inhibitory downstream targets, such as Fas ligand,23 Bim-1,30,31 p27kip1,32 and p130.33 Phosphorylation of FOXO3a prevents its transcriptional repression of targets that promote cell proliferation, such as D-type cyclins.34 FOXO3a has been shown to function at the G2-M checkpoint in the cell cycle and to trigger repair of DNA damage in a Gadd45-mediated fashion.35 FOXO3a also protects quiescent cells from oxidative stress by up-regulating manganese superoxide dismutase.36 Phosphorylation of FOXO3a by erythropoietin and stem cell factor prevents its acetylation and its interaction with the coactivator p300 in erythroid progenitor cells.37 Collectively, the modulation of multiple FOXO3a targets provides multiple mechanisms by which FOXO3a can regulate cell survival and proliferation and can coordinate a response to DNA damage.

In the present study, we show that constitutive or inducible expression of NPM-ALK in Ba/F3 leads to the phosphorylation and nuclear exclusion of FOXO3a. Transient expression of NPMALK in U-20S cells inhibited FOXO3a-mediated transactivation of reporter gene expression. Furthermore, NPM-ALK-induced FOXO3a phosphorylation in Ba/F3 cells resulted in the down-regulation of Bim-1 and p27kip1 and the up-regulation of cyclin D2. Moreover, NPM-ALK could reverse proliferation arrest and p27kip1 induction caused by FOXO3a but not by the phosphorylation site mutant FOXO3a-AAA. Thus, we show that the NPM-ALK-mediated regulation of downstream targets of FOXO3a constitutes a novel mechanism in the pathogenesis of ALK-positive ALCL. NPM-ALK-dependent phosphorylation and relocalization of FOXO3a can, therefore, promote cell survival and proliferation by overcoming a barrier imposed by FOXO3a.

Materials and methods

Pharmacologic inhibitors

Hygromycin B (50 mg/mL in phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]) was purchased from Roche (Basel, Switzerland). Doxycycline was purchased from Clontech (Palo Alto, CA) and was resuspended in water (2 mg/mL). LY294002 was purchased from Biomol (Plymouth Meeting, PA) and was resuspended in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (25 mg/mL).

Plasmid constructs

pSRa-tkneo-NPM-ALK was kindly provided by Stephan Morris (St Jude Children's Research Hospital, Memphis, TN). Murine stem cell virus (MSCV)--NPM-ALK-neo was constructed by subcloning a blunted HindIII fragment of NPM-ALK into the Hpa1 site of the MSCV-neo vector. An NPM-ALK HindIII fragment was subcloned into pcDNA3 and pRev-TRE-Hyg vectors at the respective HindIII sites to generate pcDNA-NPM-ALK and pRev-TRE-Hyg-NPM-ALK, respectively. pRev-TRE-Hyg was from Clontech. Cytomegalovirus (CMV)-Renilla was a gift from Rene Bernards (Netherlands Cancer Institute, Amsterdam). Then 3 × insulin-responsive sequence (IRS)-Luc and pcDNA3.1-FLAG-Foxo3a were provided by William Sellers (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA). pEGFP-Foxo3a and pEGFP-Foxo3a.AAA were generated by cloning a FLAG-Foxo3a(AAA) HindIII-XhoI fragment from pcDNA3.1-FLAGFoxo3a(AAA) into a pEGFP-C3 HindIII-SmaI vector site. The pREV-TRE-Hyg-FOXO3a and pREV-TRE-Hyg-FOXO3a-AAA constructs were generated by cloning a HindIII-XhoI fragment from FOXO3a-pcDNA3.1 or FOXO3a-AAA-pcDNA3.1, respectively, into the BamHI-SalI sites of pRev-TRE-Hyg.

Cell culture

Ba/F3 cells were maintained in RPMI medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco-BRL, Carlsbad, CA) and 1 ng/mL IL-3 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). TonBaF.1 cells expressing the reverse tettransactivator (gift from George Daley, Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research, Cambridge, MA)38 were maintained in RPMI medium (Bio-Whittaker, Miami, FL) containing 10% FBS, 1 mg/mL G418 (Gibco-BRL), and 1 ng/mL IL-3. Ba/F3 cells stably expressing NPM-ALK were generated by retroviral transduction of Ba/F3 cells with MSCV-neo-NPM-ALK.39 Transduced cells were selected in the absence of IL-3 and were cultured in RPMI medium containing 10% FBS and 1 mg/mL G418. Doxycycline-inducible NPM-ALK-expressing cell lines were generated by retroviral transduction39 of pRev-TRE-Hyg-NPM-ALK into TonBaF.1 cells. Retrovirally transduced cells were selected in the presence of 800 μg/mL Hygromycin B for 2 weeks. Thereafter these cells were cultured in RPMI medium containing 10% FBS, 1 mg/mL G418, 0.5 ng/mL IL-3, and 250 μg/mL Hygromycin B. Expression of NPM-ALK was induced by adding doxycycline (2 μg/mL) for 6 to 48 hours. U-20S human osteosarcoma cells used in the luciferase assay and Cos-7 monkey kidney cells used in subcellular localization studies were maintained in Dulbecco minimal essential medium (DMEM; Bio-Whittaker, Walkersville, MD) medium containing 10% FBS.

The NPM-ALK-positive human anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) cell lines (Karpas-299, SUDHL-1, and SR-786) were obtained from Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen GmbH. They were maintained in RPMI medium containing 10% FBS. TonBaF.1-FOXO3a and TonBaF.1-FOXO3a-AAA cells stably transformed with NPM-ALK were generated by retroviral transduction of TonBaF.1 cells with the MSCV-NPM-ALK-IRES-GFP vector and selection for IL-3-independent cells. These cells were then transduced with either pREV-TREHyg-FOXO3a or pREV-TRE-Hyg-FOXO3a-AAA vector and selected in Hygromycin B (800 μg/mL). Cells were maintained in RPMI medium containing 10% FBS, 1 mg/mL G418, and 250 μg/mL Hygromycin B.

Immunoblot analysis

Cells were grown to an approximate density of 5 × 105 cells/mL, collected by centrifugation (1200 rpm, 5 minutes, 4°C), washed in ice-cold PBS containing 0.4 mM Na3VO4, and lysed in the appropriate amount of 1% Triton lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 5 mM EDTA [ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid], 1 mM Na3VO4, 10% glycerol, 25 mM NaF, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, 20 μM phenylarsine oxide, 2.5 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 57 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and 1 × Protease Arrest [Geno Technology, St Louis, MO]) for 5 minutes at 4°C. Lysates were then clarified by centrifugation (15 000g, 10 minutes, 4°C) and collected. Protein concentration was determined by Bradford assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Equal amounts of protein (20-50 μg) boiled with sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-sample buffer were fractionated by 10% or 15% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and were electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose (Protran; Schleicher & Schuell BioScience, Dassel, Germany) or polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (Immobilon-P; Millipore, Bedford, MA). Membranes were blocked in 5% instant nonfat dry milk in Western wash buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 0.1% Triton X-100, and 0.9% NaCl) at room temperature for 30 minutes or at 4°C overnight. Membranes were then incubated with primary antibody (1:1000 dilution in milk) at room temperature for 1.5 hours or at 4°C overnight, washed 3 times with Western wash buffer, and incubated with secondary antibody (1:1000 dilution in milk) for 45 minutes at room temperature. After 3 more washes with Western wash buffer, Western blots were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence with Hyperfilm (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Bucking-hamshire, England). In some cases, membranes were stripped at 65°C for 30 minutes in 2% SDS, 64 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, and 0.1 M 2-mercaptoethanol, washed in Western wash buffer, blocked, and reprobed as described above.

Antibodies

Antibodies to the following targets were used as primary antibodies in our studies: FKHRL1 (H-144), phospho-FKHRL1 (Thr32), p27kip1 (C-19), Rack1(B-3), and cyclin D2 (34B1-3), all from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA); AKT and phospho-AKT (Ser473) from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA); Bim from Affinity Bioreagents (Golden, CO); and NPM-ALK (anti-ALK) from BD PharMingen (Palo Alto, CA). Secondary antibodies used were horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) and HRP-conjugated anti-mouse IgG from Amersham (Buckinghamshire, England) and HRP-conjugated anti-rat IgG from Sigma (Woodlands, TX).

Luciferase assay

Luciferase assay was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System; Promega, Madison, WI). Briefly, U-2OS cells were grown to a density of 1.5 × 105 cells/well in 6-well dishes and were transfected with a total of 2 μg appropriate plasmid DNA (pcDNA-Foxo3a, pcDNA-NPM-ALK, CMV-Renilla, or pcDNA). Two hours after transfection, cells were cultured in serum-free DMEM for 40 hours. Luciferase and Renilla luciferase activities were determined for each sample, as described in the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System instructions.

Immunolocalization

Cos-7 cells were plated onto glass coverslips at a density of 105 cells/well in 12-well dishes. Cells were transfected using SuperFect (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) with 0.3 μg enhanced green fluorescence protein (EGFP)-Foxo3a or EGFP-Foxo3a-AAA plasmid and were cotransfected with 1.2 μg pcDNANPM-ALK or pcDNA empty vector. Two hours after transfection, cells were cultured in serum-free DMEM for 40 hours and then examined using fluorescence microscopy. The pattern of EGFP signal distribution was analyzed for 20 to 50 cells per coverslip.

Assays for cell proliferation

Cells were plated at a density of 5000 cells/200 μL in 96-well plates in RPMI supplemented with 10% FBS, G418 (1.0 mg/mL), and Hygromycin B (250 μg/mL). After 72 hours of culture at 37°C, 1 μCi (0.037 MBq) thymidine [methyl-3H] was added to each well. After 5 hours of incubation at 37°C, samples were harvested and assayed using a Betaplate reader (model 1205; Perkin-Elmer, Boston, MA). In some cases, cell proliferation was assayed using the CellTiter 96 Aqueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay according to the manufacturer's instructions (Promega).

Results

Generation of Ba/F3 cell lines with constitutive or inducible NPM-ALK expression

To study the effect of NPM-ALK expression on the PI 3-kinase/AKT regulatory pathway, we generated Ba/F3 cell lines that expressed NPM-ALK either in a constitutive or an inducible manner. The inducible cell line was generated by retroviral transduction of TonBaF.1 cells, which express the reverse Tettransactivator,38 with the pRev-TRE-Hyg-NPM-ALK vector expressing NPM-ALK from the Tet-response element. In 3 independently transduced cell populations (A, B, C), we observed doxycycline-inducible expression of NPM-ALK at 24 and 48 hours after the addition of doxycycline (Figure 1A).

Expression of NPM-ALK in inducible and constitutive Ba/F3 expression systems. (A) Expression of the fusion protein NPM-ALK (80 kDa) in TonBaF.1-NPMALK cells 24 hours and 48 hours after the addition of 2 μg/mL doxycycline. Lanes A, B, and C correspond to 3 independent retroviral transductions of TonBaF.1 cells with pRev-TRE-Hyg-NPM-ALK. Uninduced samples were harvested from cells starved of IL-3 for 17 hours. +Dox 24-hour and +Dox 48-hour samples were harvested from cells starved of IL-3 for 17 hours and induced with 2 μg/mL doxycycline for 24 hours and 48 hours, respectively. Whole-cell lysates were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with NPM-ALK specific antibody. Cells derived from transduction C were used for subsequent analyses.(B) Expression of the fusion protein NPM-ALK in Ba/F3 cells stably transformed with NPM-ALK. Whole-cell lysates of MSCV and MSCV-NPM-ALK-transduced Ba/F3 cells were harvested, fractionated by SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotted with NPM-ALK-specific antibody.

Expression of NPM-ALK in inducible and constitutive Ba/F3 expression systems. (A) Expression of the fusion protein NPM-ALK (80 kDa) in TonBaF.1-NPMALK cells 24 hours and 48 hours after the addition of 2 μg/mL doxycycline. Lanes A, B, and C correspond to 3 independent retroviral transductions of TonBaF.1 cells with pRev-TRE-Hyg-NPM-ALK. Uninduced samples were harvested from cells starved of IL-3 for 17 hours. +Dox 24-hour and +Dox 48-hour samples were harvested from cells starved of IL-3 for 17 hours and induced with 2 μg/mL doxycycline for 24 hours and 48 hours, respectively. Whole-cell lysates were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with NPM-ALK specific antibody. Cells derived from transduction C were used for subsequent analyses.(B) Expression of the fusion protein NPM-ALK in Ba/F3 cells stably transformed with NPM-ALK. Whole-cell lysates of MSCV and MSCV-NPM-ALK-transduced Ba/F3 cells were harvested, fractionated by SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotted with NPM-ALK-specific antibody.

We also generated a constitutive NPM-ALK-Ba/F3 cell line to confirm results observed in the inducible system. Stable expression of NPM-ALK from the MSCV-LTR enhancer and promoter elements was achieved by means of retroviral transduction of Ba/F3 cells with MSCV-NPM-ALK. Stable expression of the NPM-ALK fusion protein (Figure 1B) conferred IL-3-independent growth and survival to Ba/F3 cells, whereas cells that contained the MSCV empty vector underwent apoptotic cell death in the absence of IL-3 (data not shown).

AKT is phosphorylated in Ba/F3 cells expressing NPM-ALK

We next confirmed previous reports that NPM-ALK activates the serine/threonine kinase AKT/PKB by phosphorylation at Ser473.12 We performed Western blot analysis with phospho-specific AKT (Ser473) or AKT-specific antibodies on whole-cell lysates harvested from cells expressing NPM-ALK after IL-3 deprivation. Doxycycline induction of NPM-ALK in the conditional expression system resulted in a robust activation of AKT, as demonstrated by phosphorylation of the Ser473 residue (Figure 2A). There was a low basal level of phosphorylated AKT species in the uninduced cells (Figure 2A). NPM-ALK-dependent AKT activation in the stable NPM-ALK expression system was confirmed by Western blotting as well. Constitutive phosphorylation of AKT (Ser473) was observed in the cell line expressing NPM-ALK, but there was a reduced level of phosphorylation in the MSCV vector control cell line (Figure 2B). Collectively, these results confirmed that NPMALK expression in Ba/F3 cells results in AKT activation.

AKT is phosphorylated on Ser473 in N/A-Ba/F3 cells in a PI 3-kinase-dependent manner. (A) Time-dependent AKT phosphorylation in TonBaF.1 cells inducibly expressing NPM-ALK 24 hours and 48 hours after the addition of 2 μg/mL doxycycline. Uninduced samples were harvested from cells starved of IL-3 for 17 hours. +Dox 24-hour and +Dox 48-hour samples were harvested from cells starved of IL-3 for 17 hours and induced with 2 μg/mL doxycycline for 24 hours and 48 hours, respectively. Whole-cell lysates were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with phospho-AKT (Ser473)-specific antibody. The membrane was stripped and reblotted with AKT-specific antibody to confirm equal expression. (B) AKT is constitutively phosphorylated in Ba/F3 cells stably transformed with NPM-ALK. Whole-cell lysates of MSCV- and MSCV-NPM-ALK-transduced Ba/F3 cells were harvested after a 17-hour IL-3 starvation, fractionated by SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotted with phospho-AKT (Ser473)-specific antibody. The membrane was stripped and reblotted with AKT-specific antibody to confirm equal expression. (C) NPM-ALK-induced phosphorylation of AKT (Ser473) is PI 3-kinase-dependent. Whole-cell lysates of MSCV- and MSCV-NPM-ALK-transduced Ba/F3 cells were harvested after a 17-hour IL-3 starvation and 1-hour exposure to 0 μM, 20 μM, or 100 μM PI 3-kinase-specific inhibitor LY294002. Equal amounts of protein were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with phospho-AKT (Ser473)-specific antibody. The membrane was stripped and reblotted with AKT-specific antibody to confirm equal expression.

AKT is phosphorylated on Ser473 in N/A-Ba/F3 cells in a PI 3-kinase-dependent manner. (A) Time-dependent AKT phosphorylation in TonBaF.1 cells inducibly expressing NPM-ALK 24 hours and 48 hours after the addition of 2 μg/mL doxycycline. Uninduced samples were harvested from cells starved of IL-3 for 17 hours. +Dox 24-hour and +Dox 48-hour samples were harvested from cells starved of IL-3 for 17 hours and induced with 2 μg/mL doxycycline for 24 hours and 48 hours, respectively. Whole-cell lysates were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with phospho-AKT (Ser473)-specific antibody. The membrane was stripped and reblotted with AKT-specific antibody to confirm equal expression. (B) AKT is constitutively phosphorylated in Ba/F3 cells stably transformed with NPM-ALK. Whole-cell lysates of MSCV- and MSCV-NPM-ALK-transduced Ba/F3 cells were harvested after a 17-hour IL-3 starvation, fractionated by SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotted with phospho-AKT (Ser473)-specific antibody. The membrane was stripped and reblotted with AKT-specific antibody to confirm equal expression. (C) NPM-ALK-induced phosphorylation of AKT (Ser473) is PI 3-kinase-dependent. Whole-cell lysates of MSCV- and MSCV-NPM-ALK-transduced Ba/F3 cells were harvested after a 17-hour IL-3 starvation and 1-hour exposure to 0 μM, 20 μM, or 100 μM PI 3-kinase-specific inhibitor LY294002. Equal amounts of protein were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with phospho-AKT (Ser473)-specific antibody. The membrane was stripped and reblotted with AKT-specific antibody to confirm equal expression.

We next characterized the NPM-ALK-dependent phosphorylation of AKT by inhibiting its upstream regulator, PI 3-kinase, with the PI 3-kinase-specific inhibitor LY294002. As indicated in Figure 2C, 1-hour treatment of Ba/F3 cells stably expressing NPM-ALK with 20 μM or 100 μM LY294002 resulted in the suppression of AKT phosphorylation at Ser473 to basal levels. This finding indicated that PI 3-kinase mediates NPM-ALK-dependent phosphorylation of AKT.

Activated AKT phosphorylates FOXO3a in Ba/F3 cells expressing NPM-ALK and in human NPM-ALK-positive lymphoma cell lines

In some contexts, AKT activation has been reported to phosphorylate members of the human Forkhead transcription factor family, including FOXO3a.23 FOXO3a is a critical regulator of programmed cell death.31 We examined whether NPM-ALK-dependent AKT activation promoted cell survival by phosphorylation of the transcriptional regulator FOXO3a. As shown in Figure 3A, the level of FOXO3a species phosphorylated at the Thr32 residue increased with the induction of NPM-ALK in TonBaF.1 cells when compared with uninduced controls. We confirmed this result in Ba/F3 cells stably expressing NPM-ALK. Cells constitutively expressing NPM-ALK had increased levels of phospho-FOXO3a (Thr32) relative to their empty vector controls (Figure 3B).

FOXO3a is phosphorylated on Thr32 in Ba/F3 cells stably or inducibly expressing NPM-ALK. (A) FOXO3a phosphorylation in TonBaF.1 cells inducibly expressing NPM-ALK 24 hours after the addition of 2 μg/mL doxycycline. Uninduced samples were harvested from cells starved of IL-3 for 17 hours. +Dox 24hr samples were harvested from cells starved of IL-3 for 17 hours and induced with 2 μg/mL doxycycline for 24 hours. Whole-cell lysates were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with phospho-FOXO3a (Thr32)-specific antibody. The membrane was stripped and reblotted with FOXO3a-specific antibody to confirm equal expression. (B) FOXO3a is constitutively phosphorylated in Ba/F3 cells stably transformed with NPM-ALK. Whole-cell lysates of MSCV- and MSCV-NPM-ALK-transduced Ba/F3 cells were harvested after a 17-hour IL-3 starvation, fractionated by SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotted with phospho-FOXO3a (Thr32)-specific antibody. The membrane was stripped and reblotted with FOXO3a-specific antibody to confirm equal expression. (C) NPM-ALK-induced phosphorylation of FOXO3a (Thr32) is dependent on PI 3-kinase activity. Whole-cell lysates of MSCV- and MSCV-NPM-ALK-transduced Ba/F3 cells were harvested after a 17-hour IL-3 starvation and 1-hour exposure to 0 μM, 20 μM, or 100 μM of the PI 3-kinase-specific inhibitor LY294002. Equal amounts of protein were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with phospho-FOXO3a (Thr32)-specific antibody. The membrane was stripped and reblotted with FOXO3a-specific antibody to confirm equal expression. (D) Constitutive phosphorylation of FOXO3a in human NPM-ALK-positive ALCL cell lines. Whole-cell lysates of Karpas-299, SUDHL-1, and SR-786 cells were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with a phospho-FOXO3a (Thr32)-specific antibody. The membrane was stripped and reprobed with a FOXO3a-specific antibody.

FOXO3a is phosphorylated on Thr32 in Ba/F3 cells stably or inducibly expressing NPM-ALK. (A) FOXO3a phosphorylation in TonBaF.1 cells inducibly expressing NPM-ALK 24 hours after the addition of 2 μg/mL doxycycline. Uninduced samples were harvested from cells starved of IL-3 for 17 hours. +Dox 24hr samples were harvested from cells starved of IL-3 for 17 hours and induced with 2 μg/mL doxycycline for 24 hours. Whole-cell lysates were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with phospho-FOXO3a (Thr32)-specific antibody. The membrane was stripped and reblotted with FOXO3a-specific antibody to confirm equal expression. (B) FOXO3a is constitutively phosphorylated in Ba/F3 cells stably transformed with NPM-ALK. Whole-cell lysates of MSCV- and MSCV-NPM-ALK-transduced Ba/F3 cells were harvested after a 17-hour IL-3 starvation, fractionated by SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotted with phospho-FOXO3a (Thr32)-specific antibody. The membrane was stripped and reblotted with FOXO3a-specific antibody to confirm equal expression. (C) NPM-ALK-induced phosphorylation of FOXO3a (Thr32) is dependent on PI 3-kinase activity. Whole-cell lysates of MSCV- and MSCV-NPM-ALK-transduced Ba/F3 cells were harvested after a 17-hour IL-3 starvation and 1-hour exposure to 0 μM, 20 μM, or 100 μM of the PI 3-kinase-specific inhibitor LY294002. Equal amounts of protein were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with phospho-FOXO3a (Thr32)-specific antibody. The membrane was stripped and reblotted with FOXO3a-specific antibody to confirm equal expression. (D) Constitutive phosphorylation of FOXO3a in human NPM-ALK-positive ALCL cell lines. Whole-cell lysates of Karpas-299, SUDHL-1, and SR-786 cells were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with a phospho-FOXO3a (Thr32)-specific antibody. The membrane was stripped and reprobed with a FOXO3a-specific antibody.

To further elucidate the mechanism of FOXO3a phosphorylation, we assessed FOXO3a (Thr32) phosphorylation in the presence of the PI 3-kinase-specific inhibitor LY294002. FOXO3a phosphorylation on Thr32 residue was diminished in Ba/F3 cells stably expressing NPM-ALK that were exposed to 20 μM or 100 μM LY294002 for 1 hour (Figure 3C). There was no change in FOXO3a protein levels during this treatment interval. These findings indicate that NPM-ALK activation of PI 3-kinase and AKT leads to hyperphosphorylation of FOXO3a at a known site of covalent regulation.

To extend these findings to human ALCL lines, we examined the phosphorylation of FOXO3a in Karpas-299, SUDHL1, and SR-786 cells; each of these lymphoma cell lines expresses the NPM-ALK fusion kinase. Turturro et al40 have shown that AKT/PKB, the kinase that is known to phosphorylate FOXO3a in response to survival stimuli, is itself phosphorylated at a site associated with kinase activation in SUDHL-1 and Karpas-299 cells. As shown in Figure 3D, FOXO3a is phosphorylated in all 3 human cell lines examined, and this finding indicates that FOXO3a phosphorylation at this regulatory threonine residue is a common event in human ALCL.

Expression of NPM-ALK inhibits FOXO3a-mediated transactivation of a reporter construct

To assess the functional consequence of FOXO3a phosphorylation in Ba/F3 cells, we tested the effect of NPM-ALK expression on FOXO3a-mediated transactivation in a transient transfection assay. We coexpressed NPM-ALK and FOXO3a in U-20S human osteosarcoma cells and assayed for transactivation of the FOXO3a-responsive promoter element IRS coupled to a luciferase reporter (3 × IRS-luc). As shown in Figure 4, NPM-ALK-induced phosphorylation of FOXO3a resulted in a dose-dependent decrement in IRS-mediated transactivation of the luciferase reporter in U-20S cells cotransfected with pcDNA-NPM-ALK and pcDNA-FOXO3a. We noted a maximal 10-fold decrease in transactivation when 0.1 μg FOXO3a was cotransfected with 0.5 μg NPM-ALK (Figure 4). Western blot analysis of FOXO3a and NPM-ALK protein levels confirmed that the decrement in transactivation was not caused by decreased expression levels of FOXO3a (data not shown). These findings indicate that NPM-ALK-induced phosphorylation of FOXO3a results in the inhibition of FOXO3a transcription factor activity in vivo.

NPM-ALK inhibits 3X IRS promoter activation by FOXO3a. U-2OS cells were transfected with the 3 × IRS reporter plasmid and pCMV-Renilla along with either 0.02, 0.1, or 0.5 μg pcDNA-NPM-ALK in the presence or absence of 0.1 μg pcDNA-FOXO3a. Cell lysates were prepared, and luciferase activity was measured and normalized to Renilla luciferase activity. Results shown are representative of 3 independent experiments, ± SD.

NPM-ALK inhibits 3X IRS promoter activation by FOXO3a. U-2OS cells were transfected with the 3 × IRS reporter plasmid and pCMV-Renilla along with either 0.02, 0.1, or 0.5 μg pcDNA-NPM-ALK in the presence or absence of 0.1 μg pcDNA-FOXO3a. Cell lysates were prepared, and luciferase activity was measured and normalized to Renilla luciferase activity. Results shown are representative of 3 independent experiments, ± SD.

NPM-ALK-induced FOXO3a phosphorylation is associated with its sequestration in the cytoplasm

We next investigated whether NPM-ALK-induced phosphorylation of FOXO3a negatively regulated FOXO3a transcriptional activity by nuclear to cytoplasmic relocalization and sequestration. We transiently transfected Cos-7 monkey kidney cells with expression vectors containing EGFP-tagged FOXO3a and EGFP-tagged FOXO3a.AAA triple mutant, in which each of the known regulatory phosphorylation sites was mutated to alanine. The pattern of EGFP signal distribution indicated the localization of wild-type and mutant FOXO3a. Seventy percent to 80% of cells expressing EGFP-FOXO3a showed a nuclear pattern of EGFP signal distribution, whereas 70% to 80% of cells coexpressing both EGFPFOXO3a and NPM-ALK demonstrated FOXO3a localization primarily to the cytoplasm (Figure 5A-B). The EGFP-tagged triple mutant FOXO3a.AAA was completely resistant to the subcellular relocalization from nucleus to cytoplasm, in the absence and in the presence of NPM-ALK expression (Figure 5A-B). Our data thus indicate that NPM-ALK-induced phosphorylation of FOXO3a results in the inhibition of its transcriptional activity by means of sequestration of phospho-FOXO3a in the cytoplasm, which precludes access to transcriptional targets.

NPM-ALK promotes FOXO3a retention in the cytoplasm in a manner dependent on FOXO3a phosphorylation. Cos-7 cells were transiently transfected with the EGFP-tagged FOXO3a construct (WT or AAA triple mutant) and were cotransfected with or without pcDNA-NPM-ALK. After 40 hours, EGFP signal was detected by fluorescence microscopy. Representative images are shown in panel A, and quantitation of the experiment is shown in panel B.

NPM-ALK promotes FOXO3a retention in the cytoplasm in a manner dependent on FOXO3a phosphorylation. Cos-7 cells were transiently transfected with the EGFP-tagged FOXO3a construct (WT or AAA triple mutant) and were cotransfected with or without pcDNA-NPM-ALK. After 40 hours, EGFP signal was detected by fluorescence microscopy. Representative images are shown in panel A, and quantitation of the experiment is shown in panel B.

Expression of FOXO3a targets Bim-1, p27kip1, and cyclin D2 is modulated in cells that express NPM-ALK

To further define the role of FOXO3a regulation in NPM-ALK-mediated proliferative and survival signaling, we directed our attention to transcriptional targets of FOXO3a. One of the downstream targets of FOXO3a that has been implicated in regulating cell survival is the proapoptotic Bcl-2 family member Bim-1. We hypothesized that NPM-ALK expression might confer a cell survival advantage by down-regulating Bim-1, which is transcriptionally activated by FOXO3a.30 Whole-cell lysates from Ba/F3 cells inducibly expressing NPM-ALK were analyzed by Western blot using a Bim-1-specific antibody. As shown in Figure 6A, we observed a time-dependent decrease in BimS (short isoform of Bim-1) levels after the induction of NPM-ALK expression with doxycycline. We confirmed this finding in Ba/F3 cells stably expressing NPM-ALK (Figure 6B). Overall, our data support the hypothesis that the NPM-ALK-induced decrease in FOXO3a-mediated apoptosis occurs through the down-regulation of Bim-1, particularly the short form of Bim-1.

The FOXO3a target BimS is down-regulated in cells inducibly or constitutively expressing NPM-ALK. (A) Western blot analysis of Bim-1 expression in TonBaF.1 cells inducibly expressing NPM-ALK. Uninduced samples were harvested from cells starved of IL-3 for 17 hours. +Dox 24hr samples were harvested from cells starved of IL-3 for 17 hours and induced with 2 μg/mL doxycycline for 24 hours. Whole-cell lysates were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with Bim-1-specific antibody. The membrane was stripped and reblotted with Rack1-specific antibody to confirm equal loading. (B) Western blot analysis of BimS expression levels in Ba/F3 cells stably transformed with NPM-ALK. Whole-cell lysates of MSCV- and MSCV-NPM-ALK-transduced Ba/F3 cells were harvested after a 17-hour IL-3 starvation, fractionated by SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotted with Bim-1-specific antibody. The membrane was stripped and reblotted with Rack1-specific antibody to confirm equal loading.

The FOXO3a target BimS is down-regulated in cells inducibly or constitutively expressing NPM-ALK. (A) Western blot analysis of Bim-1 expression in TonBaF.1 cells inducibly expressing NPM-ALK. Uninduced samples were harvested from cells starved of IL-3 for 17 hours. +Dox 24hr samples were harvested from cells starved of IL-3 for 17 hours and induced with 2 μg/mL doxycycline for 24 hours. Whole-cell lysates were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with Bim-1-specific antibody. The membrane was stripped and reblotted with Rack1-specific antibody to confirm equal loading. (B) Western blot analysis of BimS expression levels in Ba/F3 cells stably transformed with NPM-ALK. Whole-cell lysates of MSCV- and MSCV-NPM-ALK-transduced Ba/F3 cells were harvested after a 17-hour IL-3 starvation, fractionated by SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotted with Bim-1-specific antibody. The membrane was stripped and reblotted with Rack1-specific antibody to confirm equal loading.

The cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitor p27kip1 has been identified as a target of cytokine-mediated proliferative signaling through PI 3-kinase/AKT-mediated phosphorylation of FOXO3a.32 We hypothesized that NPM-ALK-induced phosphorylation of FOXO3a would inhibit p27kip1 expression, leading to a reversal of cell cycle arrest in the G1 phase and an increased proliferative advantage. We tested this by performing Western blot analysis of Ba/F3 cell lysates with a p27kip1-specific antibody. In the inducible and the constitutively expressing NPM-ALK-Ba/F3 cells, we observed a decrease in p27kip1 protein levels (Figure 7A-B).

FOXO3a target p27kip1 is down-regulated in cells inducibly or constitutively expressing NPM-ALK. (A) Western blot analysis of p27kip1 expression levels in TonBaF.1 cells inducibly expressing NPM-ALK 24 hours after the addition of 2 μg/mL doxycycline. Uninduced samples were harvested from cells starved of IL-3 for 17 hours. +Dox 24hr samples were harvested from cells starved of IL-3 for 17 hours and induced with 2 μg/mL doxycycline for 24 hours. Whole-cell lysates were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with p27kip1-specific antibody. The membrane was stripped and reblotted with Rack1-specific antibody to confirm equal loading. (B) Western blot analysis of p27kip1 expression in Ba/F3 cells stably transformed with NPM-ALK. Whole-cell lysates of MSCV- and MSCV-NPM-ALK-transduced Ba/F3 cells were harvested after a 17-hour IL-3 starvation, fractionated by SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotted with p27kip1-specific antibody. The membrane was stripped and reblotted with Rack1-specific antibody to confirm equal loading.

FOXO3a target p27kip1 is down-regulated in cells inducibly or constitutively expressing NPM-ALK. (A) Western blot analysis of p27kip1 expression levels in TonBaF.1 cells inducibly expressing NPM-ALK 24 hours after the addition of 2 μg/mL doxycycline. Uninduced samples were harvested from cells starved of IL-3 for 17 hours. +Dox 24hr samples were harvested from cells starved of IL-3 for 17 hours and induced with 2 μg/mL doxycycline for 24 hours. Whole-cell lysates were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with p27kip1-specific antibody. The membrane was stripped and reblotted with Rack1-specific antibody to confirm equal loading. (B) Western blot analysis of p27kip1 expression in Ba/F3 cells stably transformed with NPM-ALK. Whole-cell lysates of MSCV- and MSCV-NPM-ALK-transduced Ba/F3 cells were harvested after a 17-hour IL-3 starvation, fractionated by SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotted with p27kip1-specific antibody. The membrane was stripped and reblotted with Rack1-specific antibody to confirm equal loading.

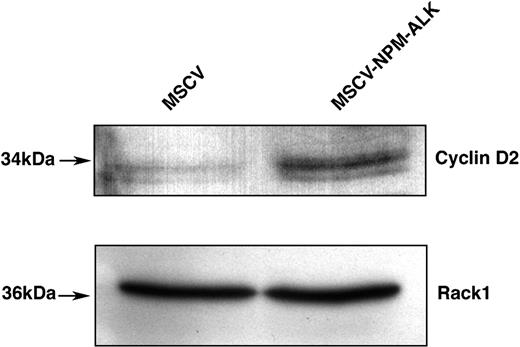

Moreover, FOXO3a has been reported to transcriptionally repress cyclin D1 and D2 expression.34 We found that NPM-ALK expression led to an increased level of cyclin D2, which complexes with CDK4/6 in the promotion of cell cycle progression (Figure 8). Thus, NPM-ALK conferred a proliferative advantage to lymphoid cells as a consequence of the down-regulation of p27kip1 and the increased expression of cyclin D2.

FOXO3a target cyclin D2 is up-regulated in cells stably transformed by NPM-ALK. Western blot analysis of cyclin D2 expression levels in Ba/F3 cells stably transformed with NPM-ALK. Whole-cell lysates of MSCV- and MSCV-NPMALK-transduced Ba/F3 cells were harvested after a 17-hour IL-3 starvation, fractionated by SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotted with cyclin D2-specific antibody. The membrane was stripped and reblotted with Rack1-specific antibody to confirm equal loading.

FOXO3a target cyclin D2 is up-regulated in cells stably transformed by NPM-ALK. Western blot analysis of cyclin D2 expression levels in Ba/F3 cells stably transformed with NPM-ALK. Whole-cell lysates of MSCV- and MSCV-NPMALK-transduced Ba/F3 cells were harvested after a 17-hour IL-3 starvation, fractionated by SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotted with cyclin D2-specific antibody. The membrane was stripped and reblotted with Rack1-specific antibody to confirm equal loading.

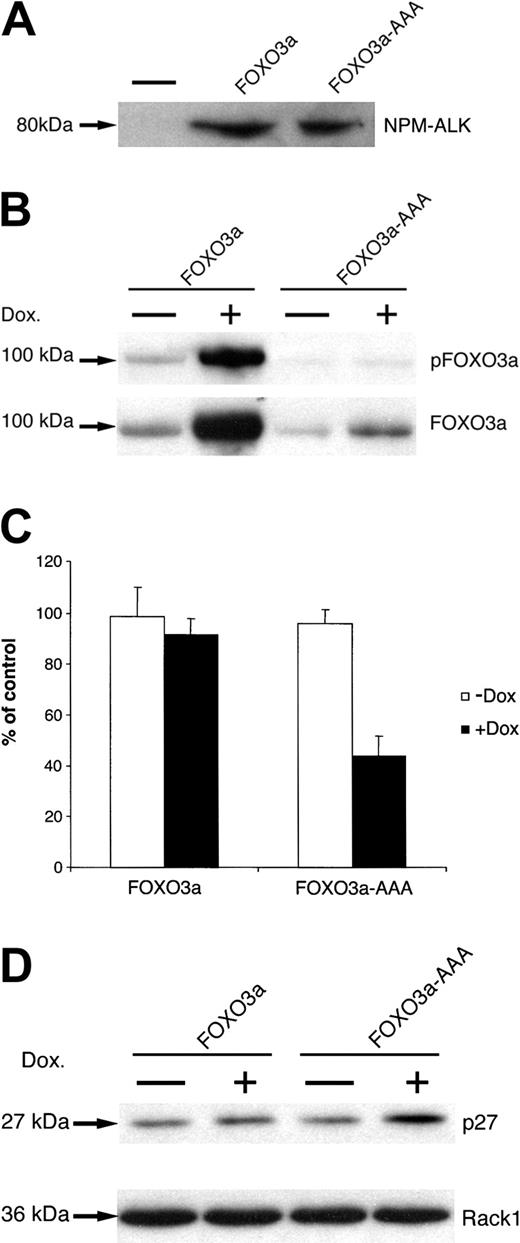

Constitutively active FOXO3a (FOXO3a-AAA) inhibits the proliferation of NPM-ALK-transformed Ba/F3 cells

To investigate the functional role of FOXO3a phosphorylation in response to NPM-ALK lymphoma kinase expression, we generated NPM-ALK-expressing cell lines with inducible expression of FOXO3a or of the phosphorylation mutant FOXO3a-AAA, which contains alanine substitutions at each of the 3 regulatory phosphorylation sites. TonBaF.1 cells were transduced with MSCVNPM-ALK-IRES-GFP vector, and NPM-ALK expression of IL-3-independent cell lines was demonstrated by anti-ALK immunoblot (Figure 9A). These TonBaF.1 cells expressing NPM-ALK were then transduced with either pREV-TRE-Hyg-FOXO3a or pREV-TRE-Hyg-FOXO3a-AAA vector. We observed the inducible expression of FOXO3a or FOXO3a-AAA after adding doxycycline for 72 hours (Figure 9B). Similar results were observed after adding doxycycline for only 48 hours (data not shown).

Constitutively active FOXO3a (FOXO3a-AAA) inhibits the proliferation of NPM-ALK-transformed Ba/F3 cells. (A) Expression of NPM-ALK in TonBaF.1-FOXO3a and TonBaF.1-FOXO3a-AAA cells stably transformed with NPM-ALK. Whole-cell lysates were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with ALK-specific antibody. The minus signs represent parental TonBaF.1 cells. (B) Expression of FOXO3a or FOXO3a-AAA in TonBaF.1-FOXO3a and TonBaF.1-FOXO3a-AAA cells stably transformed with NPM-ALK after 72-hour incubation with 2 μg/mL doxycycline. Whole-cell lysates were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with antiphospho-FOXO3a (Thr32)-specific antibody. The membrane was stripped and reprobed with anti-FOXO3a-specific antibody. (C) Effect of FOXO3a or FOXO3a-AAA expression on the proliferation of NPM-ALK-transformed Ba/F3 cells. Thymidine incorporation assay was performed after 72 hours of culture. Values represent the mean ± SD of triplicate cultures and are expressed as percentages of uninduced control cells. (D) Western blot analysis of p27kip1 expression in TonBaF.1-FOXO3a or TonBaF.1-FOXO3a-AAA cells stably transformed with NPM-ALK. Whole-cell lysates were harvested and fractionated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with p27kip1-specific antibody. The membrane was stripped and reprobed with Rack1-specific antibody to confirm equal loading.

Constitutively active FOXO3a (FOXO3a-AAA) inhibits the proliferation of NPM-ALK-transformed Ba/F3 cells. (A) Expression of NPM-ALK in TonBaF.1-FOXO3a and TonBaF.1-FOXO3a-AAA cells stably transformed with NPM-ALK. Whole-cell lysates were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with ALK-specific antibody. The minus signs represent parental TonBaF.1 cells. (B) Expression of FOXO3a or FOXO3a-AAA in TonBaF.1-FOXO3a and TonBaF.1-FOXO3a-AAA cells stably transformed with NPM-ALK after 72-hour incubation with 2 μg/mL doxycycline. Whole-cell lysates were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with antiphospho-FOXO3a (Thr32)-specific antibody. The membrane was stripped and reprobed with anti-FOXO3a-specific antibody. (C) Effect of FOXO3a or FOXO3a-AAA expression on the proliferation of NPM-ALK-transformed Ba/F3 cells. Thymidine incorporation assay was performed after 72 hours of culture. Values represent the mean ± SD of triplicate cultures and are expressed as percentages of uninduced control cells. (D) Western blot analysis of p27kip1 expression in TonBaF.1-FOXO3a or TonBaF.1-FOXO3a-AAA cells stably transformed with NPM-ALK. Whole-cell lysates were harvested and fractionated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with p27kip1-specific antibody. The membrane was stripped and reprobed with Rack1-specific antibody to confirm equal loading.

Induced expression of FOXO3a-AAA by doxycycline led to inhibited thymidine incorporation into the NPM-ALK-expressing Ba/F3 cells, whereas doxycycline induction of FOXO3a caused little impairment of thymidine incorporation (Figure 9C). Although the expression level of induced FOXO3a was greater than that of induced FOXO3a-AAA after doxycycline was added for 72 hours (Figure 9B), FOXO3a inhibition of cell proliferation was nevertheless reversed by the expression of NPM-ALK in these cell lines. Thus, NPM-ALK inhibition of FOXO3a was dependent on the 3 regulatory phosphorylation sites within FOXO3a. Similar results were observed using a modified MTT colorimetric assay (Promega) (data not shown).

The cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitor p27kip1 has been shown to be transcriptionally activated by FOXO3a,32 and this is one mechanism by which FOXO3a inhibits cell proliferation. After demonstrating that FOXO3a is inhibited by expression of the NPM-ALK lymphoma kinase, we predicted that expression of NPM-ALK might suppress p27kip1 in a manner dependent on the phosphorylation of FOXO3a. As shown in Figure 9D, the expression level of p27kip1 in FOXO3a-AAA transfectant was increased approximately 2-fold after exposure to doxycycline for 72 hours (as quantitated by densitometric evaluation of the immunoblot). These results indicate that NPM-ALK expression leads to hyperphosphorylation of FOXO3a, and this phosphorylation is required for overcoming FOXO3a-dependent induction of the p27kip1 CDK inhibitor and for reversing FOXO3a-dependent cell proliferation arrest.

Discussion

The NPM-ALK fusion kinase of ALCL promotes the proliferation and survival of lymphoid cells through the activation of multiple signaling pathways.1,41 Previous investigations have demonstrated a role for NPM-ALK activation of PLC-γ in the promotion of hematopoietic cell proliferation,11 and the activation of PI 3-kinase and AKT by NPM-ALK is known to promote survival of these cells.12,18 We wanted to further elucidate the consequences of AKT activation in hematopoietic cells that express NPM-ALK, and we now show that the AKT substrate FOXO3a is a locus for regulating cell survival and proliferation in cells that express this fusion kinase. First, we have demonstrated that activating AKT by NPM-ALK expression in a murine hematopoietic cell line results in hyperphosphorylation of FOXO3a; this covalent modification has been demonstrated previously to regulate the nuclear/cytoplasmic trafficking of this transcriptional regulator.23 We also observed phosphorylation of FOXO3a in several human NPMALK-positive ALCL lines, demonstrating the pertinence of this regulatory pathway to human ALCL. Interestingly, although the phosphorylation of the protein kinase AKT/PKB, which itself phosphorylates FOXO3a in response to PI 3-kinase activation, is diminished in Karpas-299 cells compared with SUDHL-1 cells, the AKT kinase activity in each cell line was sufficient to support the phosphorylation and inhibition of FOXO3a. Second, NPM-ALK expression attenuated transcription from a FOXO3a-dependent reporter construct. Third, the regulation of FOXO3a by NPM-ALK occurred through the exclusion of FOXO3a from the nucleus. The sequestration of FOXO3a from the nuclear compartment was mediated by phosphorylation of this molecule because a mutant FOXO3a molecule that lacked known serine/threonine phosphorylation sites remained in the nuclear compartment despite expression of NPM-ALK. FOXO3a comprises a barrier to hematopoietic neoplasia that is overcome by expression of the NPM-ALK fusion protein.

This inhibition of FOXO3a function by NPM-ALK resulted in altered expression of endogenous FOXO3a targets known to regulate survival or cell cycle progression. FOXO3a is known to induce expression of the CDK inhibitor p27kip1, and the suppression of p27kip1 expression by NPM-ALK is one mechanism by which NPM-ALK can promote cell cycle progression.32 Similarly, cyclin D protein expression is inhibited by FOXO3a,34 and the derepression by NPM-ALK of cyclin D2 expression cooperates with the reduction of p27kip1 protein levels to promote cell cycle progression. Cell cycle arrest in G1 and cyclin D repression have also been shown to be mediated by a FOXO1-dependent mechanism.42 The suppression of cell proliferation and induction of p27kip1 by FOXO3a was reversed by NPM-ALK expression, but the phosphorylation-site mutant FOXO3a-AAA was insensitive to NPM-ALK regulation. Thus, inhibition of FOXO3a activity is dependent on the phosphorylation of this transcription factor. FOXO3a also stimulates expression of the cell survival inhibitor Bim-1,31 and NPM-ALK suppression of FOXO3a function and Bim-1 expression can enhance hematopoietic cell survival by promoting mitochondrial integrity.31

These findings indicate that multiple downstream targets of FOXO3a act in a combinatorial manner to promote cell survival and proliferation in ALK-positive lymphomas. Previous reports have shown that NPM-ALK activates PLC-γ,11 and mutation of the NPM-ALK phosphotyrosine binding site for PLC-γ compromises IL-3-independent proliferation of Ba/F3 cells. Interestingly, these cells could be rescued by IL-3 after prolonged starvation of this cytokine, suggesting that impairment of PLC-γ signaling does not irreversibly impair survival signaling by NPM-ALK. We have shown here that NPM-ALK regulates FOXO3a to enhance cyclin D2 expression and to repress the expression of p27kip1. Thus, bipartite signaling through PLC-γ and PI 3-kinase/AKT/FOXO3a provides a dual means of promoting cell proliferation.

Similarly, NPM-ALK signaling through AKT stimulates multiple pathways that promote cell survival. AKT is known to phosphorylate the Bcl-2 inhibitor BAD and to promote its association with 14-3-3 in an inactive complex; this triggered sequestration of BAD liberates Bcl-2 to promote cell survival.19 Apoptosis induced by the overexpression of BAD can be partially impaired by NPM-ALK expression.12 We show here that expression of the FOXO3a transcriptional target Bim-1 is attenuated by expression of the NPM-ALK fusion kinase. Thus, NPM-ALK can promote cell survival through FOXO3a-dependent transcriptional mechanisms (in the case of Bim-1) and through posttranslational modification of apoptosis-promoting proteins (in the case of BAD). These multiple layers of signaling that regulate apoptosis are likely to contribute to the enhanced survival of lymphoid cells in the pathogenesis of ALK-positive ALCL neoplasms.

We have shown that the inhibition of FOXO3a-dependent transcriptional regulation occurs through modulation of this protein's nuclear localization. This finding does not preclude other potential mechanisms for the control of forkhead transcription factor function by the NPM-ALK tyrosine kinase. For example, it has been proposed that the binding of a 14-3-3 isoform to FOXO family members in the nucleus triggers the release of the FOXO protein from DNA.43 Mahmud et al37 have reported that FOXO3a is acetylated and associates with the p300 coactivator in response to growth factor deprivation. Furthermore, FOXO protein phosphorylation may trigger its degradation by a proteosome-dependent mechanism.29

Identifying FOXO3a as a target of NPM-ALK-dependent signaling in mitogenesis and cell survival suggests that this protein might serve as a novel therapeutic target in ALK-positive lymphomas. Moreover, ALK fusions have been described in inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors (IMT) of childhood,1,44 and evidence has been presented to support the role of activated ALK in the pathogenesis of the central nervous system tumor glioblastoma multiformi.45 Whether FOXO family members are modulated by an activated ALK in these nonhematopoietic tumors remains to be determined, but the findings presented here suggest that chemotherapeutic intervention of FOXO-dependent signaling may have broad therapeutic application.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, February 12, 2004; DOI 10.1182/blood-2003-03-0820.

Supported by National Institutes of Health grants CA66996 (J.D.G.), CA66996 and DK50654 (D.G.G.), and CA82261 (D.W.S.). B.S. is supported by a fellowship from the Dutch Cancer Society (KWF/NKB). D.G.G. is supported by a grant from the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society and is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

T.L.-G. and Z.T. contributed equally to this work.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.