Abstract

We investigated the involvement of the urokinase-type plasminogen-activator receptor (uPAR) in granulocyte–colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF)–induced mobilization of CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) from 16 healthy donors. Analysis of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMNCs) showed an increased uPAR expression after G-CSF treatment in CD33+ myeloid and CD14+ monocytic cells, whereas mobilized CD34+ HSCs remained uPAR negative. G-CSF treatment also induced an increase in serum levels of soluble uPAR (suPAR). Cleaved forms of suPAR (c-suPAR) were released in vitro by PBMNCs and were also detected in the serum of G-CSF–treated donors. c-suPAR was able to chemoattract CD34+ KG1 leukemia cells and CD34+ HSCs, as documented by their in vitro migratory response to a chemotactic suPAR-derived peptide (uPAR84-95). uPAR84-95 induced CD34+ KG1 and CD34+ HSC migration by activating the high-affinity fMet-Leu-Phe (fMLP) receptor (FPR). In addition, uPAR84-95 inhibited CD34+ KG1 and CD34+ HSC in vitro migration toward the stromal-derived factor 1 (SDF1), thus suggesting the heterologous desensitization of its receptor, CXCR4. Finally, uPAR84-95 treatment significantly increased the output of clonogenic progenitors from long-term cultures of CD34+ HSCs. Our findings demonstrate that G-CSF–induced upregulation of uPAR on circulating CD33+ and CD14+ cells is associated with increased uPAR shedding, which leads to the appearance of serum c-suPAR. c-suPAR could contribute to the mobilization of HSCs by promoting their FPR-mediated migration and by inducing CXCR4 desensitization.

Introduction

Granulocyte–colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), as a single agent or in combination with cytotoxic drugs, is widely used in clinical transplantation to induce hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) mobilization into peripheral blood (PB).1-3 Currently, mobilized PB HSCs represent the major source of stem cells for autologous stem cell transplantation (SCT); they are also increasingly used in allogeneic SCT because of the relative ease of collection, the higher yield of stem cells, and the shorter time to engraftment.4 The engraftment of circulating stem cells depends on the capability of mobilized HSCs to home back to the bone marrow (BM). Mobilization and homing are mirror processes that use the same mediators and similar signaling pathways.5,6 Despite the increasing use of mobilized HSCs, the mechanisms governing HSC trafficking from and to BM are not yet well defined. Adhesion molecules, such as β1 and β2 integrins (ie, VLA-4, VLA-5, and LFA-1), L-selectin, and stromal-derived factor 1 (SDF1) chemokine and its receptor, CXCR4, are well recognized key players in the mobilization and homing of HSCs.4-7 HSC release from bone marrow also involves proteolytic enzymes, which are able to cleave SDF1 and its receptor, thus inactivating the SDF1/CXCR4-dependent signaling pathway.8-13 However, how adhesion molecules, chemokines, and proteases act and cross-talk is only partly understood.

Recently, many reports have clearly shown the involvement of the urokinase-mediated plasminogen activation system, particularly of the urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPAR) receptor in cell adhesion and migration.14-16 uPAR has a 3-domain structure and is anchored to the cell membrane through a glycosyl phosphatidylinositol (GPI) tail.17 However, in spite of the lack of a transducing cytoplasmic tail, the receptor is able to activate inner signaling pathways, probably by interaction with other cell surface molecules.18 uPAR binds urokinase (uPA) through its N-terminal domain (D1) and vitronectin (VN), an extracellular matrix (ECM) component.14 uPA proteolytic activity is retained after binding and can be inhibited by 2 specific inhibitors, PAI-1 and PAI-2.19 The receptor also interacts with and regulates the activity of cell-adhesion specialized molecules, such as integrins of the β1 and β2 families, including LFA-1 and VLA-4.20,21 A signaling partnership between uPAR and L-selectin in human polymorphonuclear neutrophils has also been reported.22

In recent years, functional interactions between the uPA-uPAR system and receptors for N-formylated peptides, such as the fMet-Leu-Phe (fMLP), a potent chemoattractant for leukocytes, have been reported.23 Three receptors belong to the fMLP receptor family: the high-affinity fMLP receptor (FPR), the low-affinity fMLP receptor FPR-like 1 (FPRL1), and FPR-like 2 (FPRL2). The latter does not bind fMLP, in spite of its high sequence homology with the other 2 receptors.24 fMLP-dependent monocyte chemotaxis requires uPAR expression,25 and we have recently shown that uPAR functionally interacts with FPR.26 In addition, a cleaved form of soluble uPAR (suPAR), devoid of D1 and exposing the specific SRSRY sequence (residues 88-92) (c-suPAR), or uPAR-derived peptides containing the SRSRY sequence can chemoattract monocytes by activating FPRL1.23,27 Interestingly, activation of both FPR and FPRL1 can lead to the desensitization of other chemokine receptors, such as CXCR4,28,29 strongly involved in HSC mobilization.30-32 Altogether, these observations suggest several links between the uPA-uPAR system and the process of HSC mobilization. Therefore, we investigated whether uPAR plays a role in the regulation of HSC mobilization from bone marrow into the circulation.

Materials and methods

Reagents

Rabbit anti-uPAR polyclonal antibody was purchased from American Diagnostica (Greenwich, CT); mouse anti-uPAR monoclonal antibodies R2, R3, and R433 were kindly provided by Dr G. Hoyer-Hansen (Finsen Laboratory, Copenhagen, Denmark). Cleaved soluble uPAR was purified as previously described.27 Horseradish peroxidase–conjugated anti–mouse and anti–rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) were from Bio-Rad (Richmond, CA); fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–labeled goat anti–rabbit IgG was from Jackson Laboratory (West Grove, PA). Protease inhibitors, Ficoll-Hypaque (specific gravity, 1077), bovine serum albumin (BSA), and hydrocortisone sodium hemisuccinate were from Sigma Chemical (St Louis, MO). The enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) detection kit was from Amersham International (Amersham, England), polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) filters were from Millipore (Windsor, MA), PNGase F and immobilized streptavidin were from Roche (Milan, Italy), and Sulfo-NHS-Biotin was from Pierce (Rockford, IL). RPMI 1640 medium, heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS), TRIzol reagent, and Superscript II (M-MLV reverse transcriptase) were from Life Technologies (Gaithersburg, MD); the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) kit was from Perkin-Elmer (Branchburg, NJ). Chemotaxis PVPF filters were purchased from Corning (NY). Stromal-derived factor 1 (SDF1) was purchased from PeproTech (London, England). FITC-, peridin chlorophyll (PerCP)–, and phycoerythrin (PE)–labeled monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) were purchased from Becton Dickinson (Mountain View, CA). Long-term stem cell medium and methylcellulose were from Stem Cell Technologies (Vancouver, BC, Canada). Interleukin-3 (IL-3), G-CSF, granulocyte macrophage–colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), stem cell factor (SCF), and erythropoietin (EPO) were from Amgen (Thousand Oaks, CA). Recombinant human G-CSF (rhG-CSF, lenograstim) was purchased from Italfarmaco (Milan, Italy). The peptide uPAR84-95 (AVTYSRSRYLEC) and its scrambled version (TLVEYYSRASCR) were prepared by PRIMM (Milan, Italy).

Sample collection

Heparinized blood samples were obtained after written informed consent (according to the procedures outlined by the ethics committee of our institution) before, during, and after the mobilizing procedure from 16 healthy adults (6 men and 10 women, 20 to 45 years old) who served as HLA-matched stem cell donors for their relatives undergoing allogeneic SCT. The donors received glycosylated rhG-CSF administered subcutaneously, at 10 μg/kg per day in 2 divided doses, for 5 days to mobilize and collect PB HSCs.1-3 Heparinized bone marrow specimens were obtained by aspiration from the posterior iliac crest of 4 healthy young donors at the time of allogeneic marrow donation, after informed consent. Plasma samples were prepared by 2 successive centrifugations to achieve complete platelet removal and were stored at -80°C.

CD34+ hematopoietic stem cell separation

PB and BM mononuclear cells (MNCs) were isolated by density gradient centrifugation using Ficoll-Hypaque. After a wash with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) supplemented with 1% BSA, CD34+ cells were highly purified by MiniMacs high-gradient magnetic separation columns (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, MNCs were incubated with a hapten-conjugated anti-CD34+ mAb in the presence of an Fc-receptor blocking reagent. These cells were subsequently incubated with MACS microbeads conjugated to an antihapten antibody and were purified using a high-gradient magnetic separation column (Miltenyi Biotec). Positive cells were discharged from the column after removal from the magnetic field. CD34+ cells were enriched to 95% purity by 2 sequential selections through the magnetic cell separator. Purity of the positively selected CD34+ cells was evaluated by flow cytometry. Purified CD34+ cells were resuspended in RPMI medium supplemented with 1% BSA.

Flow cytometric analysis

Enumeration of CD34+ cells and immunophenotyping of the different PB cell types were performed by 2- and 3-color flow cytometry, respectively, in which CD34+ and other cell populations were gated by a CD45-gating method.34 Briefly, whole blood containing approximately 1 × 106 cells was stained with 20 μL directly conjugated monoclonal antibody for 20 minutes at 4°C. The cells were stained in each combination with PerCP-labeled anti-CD45 antibody and with pairs of antibodies conjugated with FITC or PE; these antibodies were directed to CD3, CD13, CD14, CD19, CD33, CD34, (FITC conjugated), or uPAR (PE conjugated). Cells were washed once with red blood cell lysis buffer (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA) and then with PBS containing 1% human serum albumin and 0.1% sodium azide. Cells were analyzed immediately on a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson). At least 5 to 10 × 105 total cells were acquired in each sample using the CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson). To eliminate from the analysis granulocytes with nonspecific antibody binding and residual red cells and debris, a mononuclear gate was created, based on CD45 expression and side light scatter. The total number of CD34+ cells was calculated on the basis of the relative percentage of CD34+ cells in the total number of nucleated cells. Equivalent gating on isotype-matched negative controls was used for background subtraction in all assays.

Cell cultures

CD34+ KG1 cell line35 and THP-1 monocyte-like cells36 were grown in RPMI supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FCS. For short-term cultures, donor PBMNCs, obtained before and at different times during G-CSF mobilization, were incubated at a concentration of 10 × 106/mL in serum-free RPMI medium; after 24 hours of culture, conditioned media were collected, centrifuged, and stored at -80°C. For long-term cultures (LTCs), highly purified BM CD34+ cells were plated on irradiated (15 Gy of 250-kV rays) allogeneic bone marrow stromal cells (3 × 104/cm2) at a cell density of 1 × 105 per well. Culture medium consisted of long-term stem cell medium supplemented with 1 × 10-6 M hydrocortisone sodium hemisuccinate. LTCs were incubated at 37°C for 3 days and then switched to 33°C for 5 weeks. These cultures were treated with 10-10 M uPAR84-95 peptide or its scrambled version for 2 hours before weekly removal of nonadherent cells. Weekly removed nonadherent cells were washed and used in replating experiments to measure the output of clonogenic progenitors. At the end of 5 weeks, stroma-adherent cells also were harvested by trypsinization, washed 3 times, and assayed for their content of clonogenic progenitors as nonadherent cells. Each experimental procedure was performed in duplicate.

Clonogenic progenitors were measured in methylcellulose, as previously described.37 Briefly, cells were plated in 1 mL medium per dish (35-mm dishes) in the presence of the following growth factor cocktail: 10 ng/mL IL-3, 50 ng/mL G-CSF, 50 ng/mL GM-CSF, 20 ng/mL SCF, and 2 U/mL EPO. Myeloid and erythroid colonies were counted as colony-forming cells (CFCs) after 14-day incubation at 5% CO2.

Western blot analysis

PBMNCs or purified CD34+ cells were lysed in 1% Triton X-100/PBS in the presence of protease inhibitors; the protein content was measured by a colorimetric assay. Fifty micrograms to 100 μg protein was electrophoresed on 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) under nonreducing conditions and were transferred to a PVDF membrane. The membrane was blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk and was probed with 1 μg/mL rabbit anti-uPAR polyclonal antibody. Finally, washed filters were incubated with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated antirabbit antibodies and were detected by ECL.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Serum suPAR analysis

suPAR analysis was performed by immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting, as previously described.40 Serum samples (400-500 μL) were diluted to 1 mL using RIPA buffer (0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 1% deoxycholate, 0.15 M NaCl, and 0.05 M Tris-HCl, pH 7.6) containing a cocktail of protease inhibitors and were immunoprecipitated for 16 hours at 4°C using 1 μg of biotinylated monoclonal antibodies (mAbs R2 and R3),33 previously immobilized on streptavidin-coated beads. Adsorbed proteins were deglycosylated by peptide-N-glycosidase F (PNG-F) and were analyzed by 12% SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions and Western blotting with a rabbit anti-uPAR polyclonal antibody.

Cell migration assay

Cell migration assays were performed in Boyden chambers, using 5-μm pore size PVPF polycarbonate uncoated filters. KG1 cells or CD34+ HSCs (2 × 105) were plated in the upper chamber in serum-free medium, and 10-10 M uPAR-derived peptide (uPAR84-95), 100 ng/mL SDF1, 10-8 M fMLP, 10-6 M fMLP, or serum-free medium was added in the lower chamber. Cells were allowed to migrate for 90 minutes at 37°C, 5% CO2. Cells on the lower surface of the filter were then fixed in ethanol, stained with hematoxylin, and counted at 200 × magnification (10 random fields/filter). In a separate set of experiments, cells were preincubated for 1 hour at 37°C with buffer, 10-7 M uPAR84-95, and 10-7 M or 10-5 M fMLP.

Reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction

Total cellular RNA was isolated by lysing cells in TRIzol solution, according to the supplier's protocol. RNA was precipitated and quantitated by spectroscopy. Total RNA (5 μg) was reverse transcribed with random hexamer primers and 200 U M-MLV reverse transcriptase. One microliter reverse-transcribed DNA was then amplified using FPR-specific 5′ sense (ATG GAG ACA AAT TCC TCT CTC) and 3′ antisense (CAC CTC TGC AGA AGG TAA AGT) primers, FPRL1-specific 5′ sense (CTT GTG ATC TGG GTG GCT GGA) and 3′ antisense (CAT TGC CTG TAA CTC AGT CTC) primers, FPRL2-specific 5′ sense (CTG AAA TGT TTC AGG TGT GGG) and 3′ antisense (TGA ACG CAG GGT AGA AAG AGA), uPAR-specific 5′ sense (CTG CGG TGC ATG CAG TGT AAG) and 3′ antisense (GGT CCA GAG GAG AGT GCC TCC) primers, or glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH)–specific 5′ sense (TTC ACC ACC ATG GAG AAG GCT) and 3′ antisense (ACA GCC TTG GCA GCA CCA GT) primers, as a control. PCR was performed for 40 cycles at 68°C (FPR and FPRL1), 40 cycles at 64°C (FPRL2), and 40 cycles at 62°C (uPAR) in a thermocycler, and the reaction products were analyzed by electrophoresis in 1% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide, followed by photography under ultraviolet illumination.

Results

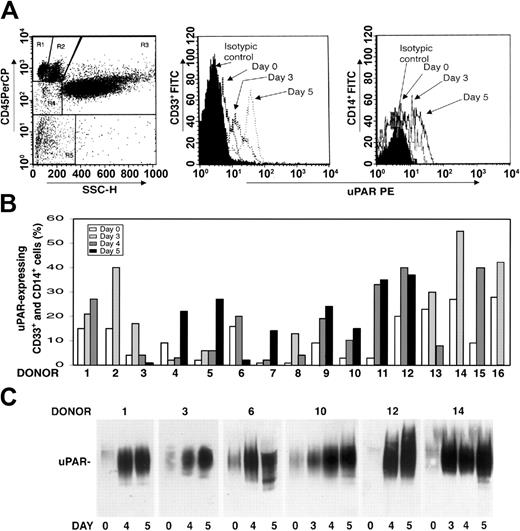

uPAR expression in PBMNCs from G-CSF–treated healthy donors

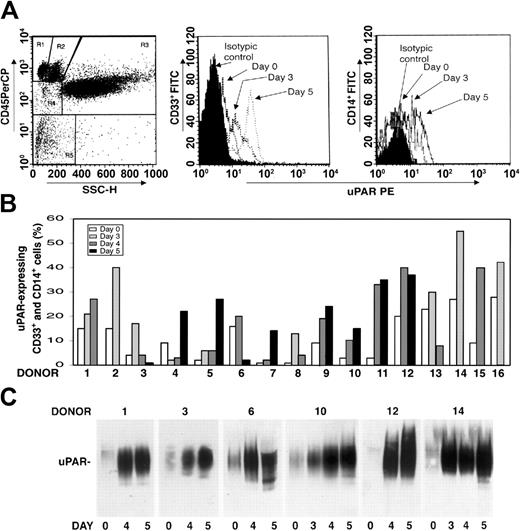

We investigated whether there was modulation of uPAR expression in the PBMNCs of healthy donors after G-CSF administration. PBMNCs were obtained from 16 healthy donors under steady state conditions before G-CSF mobilization (day 0) and at different time points (days 3-5) during G-CSF stimulation, depending on CD34+ stem cell mobilization efficiency. Phenotypic analysis of CD3+ and CD19+ uPAR–expressing cells was determined by 3-color flow cytometry on a mononuclear gate of CD45+ cells for optimal exclusion of granulocytes with nonspecific antibody binding, residual red cells, and debris. Phenotypic analysis of CD14+ monocytic cells and CD33+ immature myeloid cells was performed by a CD45 gating method in the mononuclear and blast gates (Figure 1A, R2 and R4). G-CSF administration increased uPAR expression in CD33+ myeloid precursors and in the CD14+ monocytic population from all the donors (Figure 1B). In almost all cases, the increase in cell surface uPAR expression peaked at the same time CD34+ HSCs peaked in PB (ie, at day 4 or 5 of G-CSF treatment) (Figure 1B). In contrast, CD3+ T lymphocytes and CD19+ B lymphocytes remained uPAR negative, and phenotypic analysis of uPAR expression on CD13+ and CD33+ mature myeloid cells, performed by CD45 gating in the granulocyte gate (Figure 1A, R3), showed that the high baseline level on granulocytes was not modified after G-CSF treatment (data not shown).

uPAR expression increases in PBMNCs from G-CSF–treated donors. (A) Expression of uPAR on CD33+ and CD14+ cells during G-CSF–induced HSC mobilization in a representative case. Immunophenotyping of CD33+ and CD14+ uPAR–expressing cells was performed by 3-color flow cytometry on mononuclear and blast gates (R2 and R4, left), gating for side light scatter (SSC-H) and CD45+, with an anti-uPAR mAb and quantified as mean fluorescence intensity. (B) Percentages of CD33+ and CD14+ uPAR–expressing cells within blast and mononuclear gates in PBMNCs collected from 16 healthy donors before (day 0) or at various time points (days 3-5) of G-CSF administration. (C) Western blot analysis with an anti-uPAR polyclonal antibody of PBMNCs (50 μg total protein) collected from 6 representative donors before (day 0) or at different time points (days 3-5) of G-CSF administration.

uPAR expression increases in PBMNCs from G-CSF–treated donors. (A) Expression of uPAR on CD33+ and CD14+ cells during G-CSF–induced HSC mobilization in a representative case. Immunophenotyping of CD33+ and CD14+ uPAR–expressing cells was performed by 3-color flow cytometry on mononuclear and blast gates (R2 and R4, left), gating for side light scatter (SSC-H) and CD45+, with an anti-uPAR mAb and quantified as mean fluorescence intensity. (B) Percentages of CD33+ and CD14+ uPAR–expressing cells within blast and mononuclear gates in PBMNCs collected from 16 healthy donors before (day 0) or at various time points (days 3-5) of G-CSF administration. (C) Western blot analysis with an anti-uPAR polyclonal antibody of PBMNCs (50 μg total protein) collected from 6 representative donors before (day 0) or at different time points (days 3-5) of G-CSF administration.

uPAR can be expressed on the surfaces of several cell types in a native and in a cleaved form; the latter lacks the N-terminal domain (D1).41-44 Thus, we investigated which form of uPAR was induced in PBMNCs by G-CSF administration. Western blot analysis with an anti-uPAR polyclonal antibody confirmed a progressive increase in uPAR expression in all donors during G-CSF treatment and showed that PBMNCs expressed only the intact form of uPAR (50 kDa) (Figure 1C).

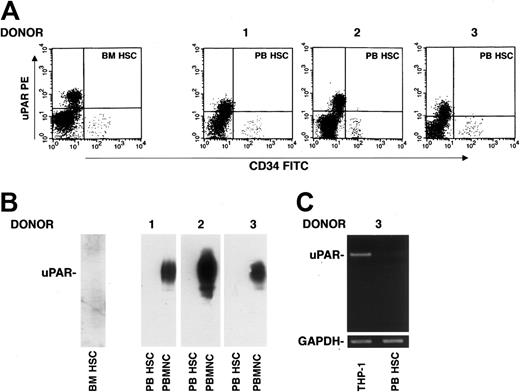

uPAR expression in mobilized CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells

uPAR expression was also investigated on CD34+ HSCs. Phenotypic analysis of CD34+ uPAR–expressing cells, determined by 3-color flow cytometry on a mononuclear gate of CD45+ cells, showed the absence of uPAR expression on CD34+ BM and circulating HSCs after G-CSF treatment (Figure 2A). This result was confirmed by Western blot analysis of highly purified CD34+ HSCs using an anti-uPAR polyclonal antibody; PBMNCs from the same G-CSF–treated donor were used as a positive control (Figure 2B). The absence of uPAR mRNA was also assessed by reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) with specific uPAR primers in G-CSF–mobilized CD34+ HSCs from one donor; RT-PCR analysis of THP-1 monocyte-like cells was used as a positive control (Figure 2C).36 These results indicate that BM CD34+ cells are uPAR negative and that G-CSF administration and transfer into circulation do not induce uPAR expression, either at the protein or at the mRNA level.

G-CSF–mobilized CD34+ HSCs do not express uPAR. (A) Immunophenotyping of CD34+ cells performed by 3-color flow cytometry on a mononuclear gate with anti-uPAR mAb, quantified as mean fluorescence intensity, in BM and in G-CSF–mobilized PB CD34+ HSCs from donors 1 to 3. (B) Western blot analysis with an anti-uPAR polyclonal antibody of BM CD34+ HSCs (BM HSC) and G-CSF–mobilized PB CD34+ HSCs (PB HSC) from donors 1 to 3 (100 μg total protein); PBMNCs from the same G-CSF–treated donors were used as positive controls (50 μg total protein). (C) RT-PCR analysis of uPAR mRNA expression in highly purified G-CSF–mobilized PB HSCs from a representative donor and THP-1 cells, used as a positive control. PCR in the presence of primers for GAPDH was used as a loading control.

G-CSF–mobilized CD34+ HSCs do not express uPAR. (A) Immunophenotyping of CD34+ cells performed by 3-color flow cytometry on a mononuclear gate with anti-uPAR mAb, quantified as mean fluorescence intensity, in BM and in G-CSF–mobilized PB CD34+ HSCs from donors 1 to 3. (B) Western blot analysis with an anti-uPAR polyclonal antibody of BM CD34+ HSCs (BM HSC) and G-CSF–mobilized PB CD34+ HSCs (PB HSC) from donors 1 to 3 (100 μg total protein); PBMNCs from the same G-CSF–treated donors were used as positive controls (50 μg total protein). (C) RT-PCR analysis of uPAR mRNA expression in highly purified G-CSF–mobilized PB HSCs from a representative donor and THP-1 cells, used as a positive control. PCR in the presence of primers for GAPDH was used as a loading control.

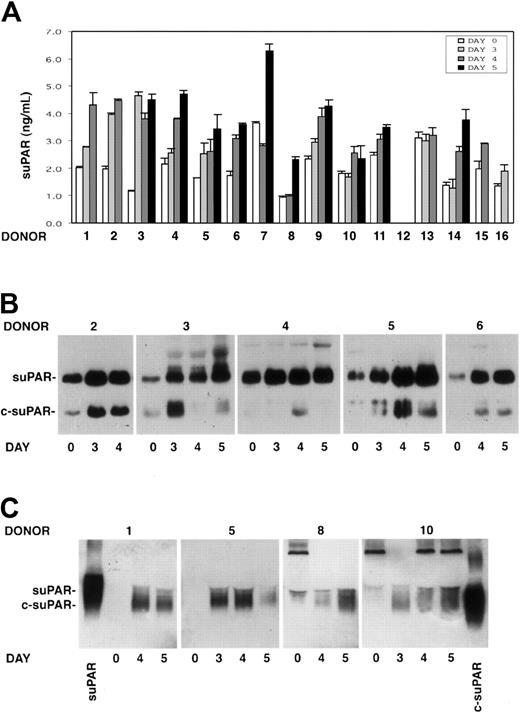

Soluble uPAR in sera of G-CSF–treated healthy donors

Mobilized CD34+ HSCs did not express uPAR, whereas PBMNCs showed a strong increase in uPAR expression after G-CSF treatment. We then investigated whether increased uPAR expression on PBMNCs was associated with increased release of uPAR in serum. In fact, uPAR is a GPI-anchored cell surface protein, but soluble forms have been detected in sera of patients affected by different diseases.39,45-50

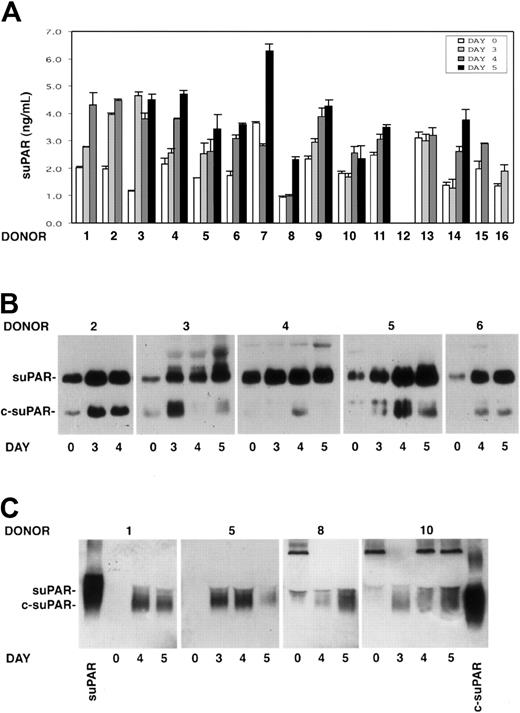

The presence of soluble uPAR (suPAR) was investigated by ELISA in the sera of 15 G-CSF–treated donors previously analyzed for PBMNC uPAR expression. Taking into account variations higher than 30%, suPAR serum levels increased in 14 of 15 donors during HSC mobilization. suPAR levels increased to the maximum extent at days 3 to 5 of G-CSF stimulations, when CD34+ HSCs also peaked in the circulation (Figure 3A).

Intact and cleaved forms of soluble uPAR increase in sera of G-CSF–treated donors. Cleaved forms of soluble uPAR are also released by donor PBMNCs in vitro. (A) ELISA measurement of soluble uPAR (suPAR) in the sera of 15 donors, collected before (day 0) or at different time points (days 3-5) of G-CSF administration. Error bars are not shown when graphically too small. (B) Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting of sera obtained from 5 donors before (day 0) and at different time points (days 3-5) of G-CSF administration. Samples were immunoprecipitated with biotinylated monoclonal antibodies (mAbs R2 and R3), previously immobilized on streptavidin-coated beads, to detect intact (suPAR) and cleaved (c-suPAR) soluble forms of uPAR. Adsorbed proteins were deglycosylated by peptide-N-glycosidase, eluted, and analyzed by immunoblotting with a rabbit anti-uPAR polyclonal antibody. (C) Western blot analysis with an anti-uPAR polyclonal antibody of conditioned media obtained after serum-free short-term cultures of PBMNCs collected before (day 0) or at different time points (days 3-5) of G-CSF stimulation from 4 representative donors. The first and the last lanes of the panel were loaded with a positive control of intact soluble uPAR (suPAR) and a cleaved form of suPAR, devoid of D1 (c-suPAR), respectively.

Intact and cleaved forms of soluble uPAR increase in sera of G-CSF–treated donors. Cleaved forms of soluble uPAR are also released by donor PBMNCs in vitro. (A) ELISA measurement of soluble uPAR (suPAR) in the sera of 15 donors, collected before (day 0) or at different time points (days 3-5) of G-CSF administration. Error bars are not shown when graphically too small. (B) Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting of sera obtained from 5 donors before (day 0) and at different time points (days 3-5) of G-CSF administration. Samples were immunoprecipitated with biotinylated monoclonal antibodies (mAbs R2 and R3), previously immobilized on streptavidin-coated beads, to detect intact (suPAR) and cleaved (c-suPAR) soluble forms of uPAR. Adsorbed proteins were deglycosylated by peptide-N-glycosidase, eluted, and analyzed by immunoblotting with a rabbit anti-uPAR polyclonal antibody. (C) Western blot analysis with an anti-uPAR polyclonal antibody of conditioned media obtained after serum-free short-term cultures of PBMNCs collected before (day 0) or at different time points (days 3-5) of G-CSF stimulation from 4 representative donors. The first and the last lanes of the panel were loaded with a positive control of intact soluble uPAR (suPAR) and a cleaved form of suPAR, devoid of D1 (c-suPAR), respectively.

Analysis of suPAR in donor sera

suPAR detected in the serum of 5 G-CSF–treated donors (donors 2-6) was analyzed by an immunoprecipitation/immunoblotting assay to determine whether the shed receptor was in the intact or in the cleaved form. The analysis showed not only the presence of the intact form of suPAR, which increased during G-CSF treatment, but also the appearance or the strong increase of cleaved forms of suPAR (c-suPAR) in all analyzed sera (Figure 3B). c-suPAR generally increased at day 3 to 4 of cytokine treatment, slightly earlier than the CD34+ HSC peak in PB (days 4-5) (Figure 3B).

In vitro release of suPAR by mobilized PBMNCs

We investigated PBMNC capability to release soluble forms of uPAR in vitro. Conditioned media obtained by short-term culture of PBMNCs from 8 donors (donors 1, 5, 8-10, 14-16) before and at different time points (days 3-5) of G-CSF stimulation were analyzed by Western blot with an anti-uPAR polyclonal antibody. PBMNCs released increasing amounts of suPAR in vitro, which was mostly in the cleaved form (c-suPAR) (Figure 3C). In fact, it comigrated with a control c-suPAR devoid of the D1 domain26 (Figure 3C) and was not recognized by a monoclonal antibody directed to the uPAR D1 domain (not shown).

These results indicate that PBMNCs from G-CSF–treated donors are able to release uPAR from their cell surfaces in vitro and that they could be the source of the increased serum suPAR in vivo. The detection of c-suPAR in donor sera and in PBMNC-conditioned media suggests that released uPAR is rapidly cleaved in vitro and in vivo because PBMNCs express mainly the intact form of uPAR (Figure 1C).

Expression of fMLP receptors in CD34+ KG1 and hematopoietic stem cells

CD34+ HSCs do not express uPAR; therefore, we could exclude a contribution of uPA to their mobilization. However, considerable amounts of cleaved suPAR were detected in donor sera during the mobilization procedure. A cleaved form of suPAR, deprived of D1 and exposing the specific sequence SRSRY (residues 88-92) (c-suPAR), is able to induce monocyte chemotaxis by activating the low-affinity receptor for fMLP (FPRL1).23,27 We investigated whether highly purified G-CSF–mobilized CD34+ HSCs expressed fMLP receptors, thus being potentially responsive to chemotactic stimuli induced by c-suPAR. The human CD34+ KG1 cell line35 was also analyzed for use in functional studies.

CD34+ KG1 cells and highly purified G-CSF–mobilized CD34+ HSCs were analyzed by RT-PCR in the presence of specific primers for FPR, FPRL1, and FPRL2. The analysis of the PCR products showed the presence of FPR and FPRL2 mRNAs, whereas FPRL1 mRNA was not detected (Figure 4).

CD34+ KG1 and HSCs express fMLP receptors. RT-PCR analysis of fMLP receptor expression in CD34+ KG1 cells and highly purified G-CSF–mobilized peripheral blood CD34+ HSCs (PB HSC) from a representative donor. RT-PCR was performed in the presence of specific primers for FPR, FPRL1, and FPRL2. PCR amplification of 50 ng human genomic DNA was added as a positive control.

CD34+ KG1 and HSCs express fMLP receptors. RT-PCR analysis of fMLP receptor expression in CD34+ KG1 cells and highly purified G-CSF–mobilized peripheral blood CD34+ HSCs (PB HSC) from a representative donor. RT-PCR was performed in the presence of specific primers for FPR, FPRL1, and FPRL2. PCR amplification of 50 ng human genomic DNA was added as a positive control.

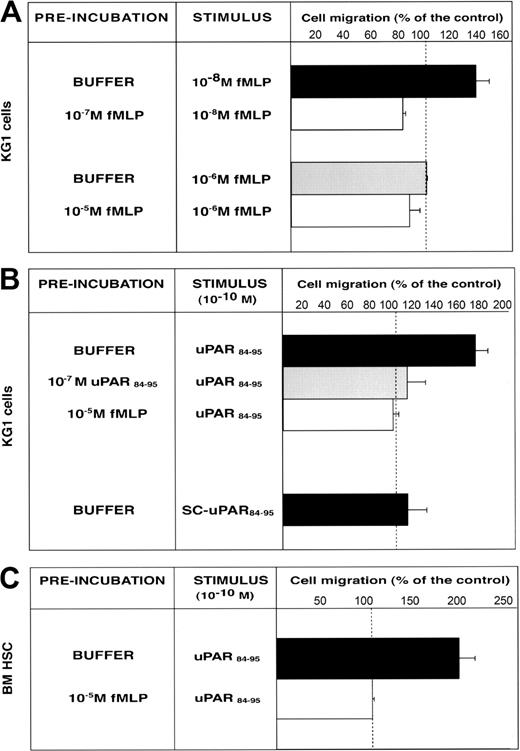

uPAR84-95–dependent migration of CD34+ KG1 and hematopoietic stem cells

We investigated the ability of CD34+ KG1 cells and highly purified BM CD34+ HSCs to migrate toward c-suPAR. First, we examined the functionality of FPR expressed by CD34+ KG1 cells. Cells were allowed to migrate toward low (10-8 M) and high (10-6 M) fMLP concentrations, which activates the high-affinity receptor (FPR) and the low-affinity fMLP receptor (FPRL1), respectively.24 Only the low fMLP dose induced CD34+ KG1 cell migration, by activating FPR; indeed, homologous desensitization of FPR by cell preincubation with 10-7 M fMLP abolished the migration (Figure 5A). CD34+ KG1 cells did not migrate toward 10-6 M fMLP (Figure 5A), most likely because they do not express FPRL1 (Figure 4A). We then investigated whether the functional FPR expressed by CD34+ KG1 cells could mediate the c-suPAR–dependent migration. KG1 cells were allowed to migrate toward the c-suPAR–derived peptide, uPAR84-95, which induces monocyte chemotaxis by FPRL1 activation.23,27 uPAR84-95, and not its scrambled version, stimulated CD34+ KG1 cell chemotaxis at the reported concentration (10-10 M).27 uPAR84-95–dependent cell migration was abolished by cell preincubation with uPAR84-95 peptide or with fMLP, thus indicating the involvement of FPR (Figure 5B). The effect of uPAR84-95 on KG1 cell migration was similar to the effect of c-suPAR (cell migration, 156% ± 9% of the control), as previously reported.27

FMLP and uPAR84-95 induce CD34+ KG1 and HSC migration by FPR activation. (A) KG1 cells, preincubated with buffer, 10-7 M fMLP, or 10-5 M fMLP, were plated in Boyden chambers and allowed to migrate toward 10-8 M fMLP or 10-6 M fMLP. (B) KG1 cells, preincubated with buffer, 10-7 M uPAR84-95, or 10-5 M fMLP, were plated in Boyden chambers and allowed to migrate toward 10-10 M uPAR84-95. Control migration toward 10-10 M scrambled uPAR84-95 (SC-uPAR84-95) was added. (C) Bone marrow CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells (BM HSC), preincubated with buffer or 10-5 M fMLP, were plated in Boyden chambers and allowed to migrate toward 10-10 M uPAR84-95. 100% values represent cell migration in the absence of chemoattractants. Values are the mean ± SD of 3 experiments performed in triplicate.

FMLP and uPAR84-95 induce CD34+ KG1 and HSC migration by FPR activation. (A) KG1 cells, preincubated with buffer, 10-7 M fMLP, or 10-5 M fMLP, were plated in Boyden chambers and allowed to migrate toward 10-8 M fMLP or 10-6 M fMLP. (B) KG1 cells, preincubated with buffer, 10-7 M uPAR84-95, or 10-5 M fMLP, were plated in Boyden chambers and allowed to migrate toward 10-10 M uPAR84-95. Control migration toward 10-10 M scrambled uPAR84-95 (SC-uPAR84-95) was added. (C) Bone marrow CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells (BM HSC), preincubated with buffer or 10-5 M fMLP, were plated in Boyden chambers and allowed to migrate toward 10-10 M uPAR84-95. 100% values represent cell migration in the absence of chemoattractants. Values are the mean ± SD of 3 experiments performed in triplicate.

uPAR84-95 also induced the migration of BM CD34+ HSCs purified from 3 donors. In addition, in these cases, uPAR84-95–dependent HSC migration was mediated by FPR activation because cell preincubation with fMLP completely abolished the migratory response (Figure 5C).

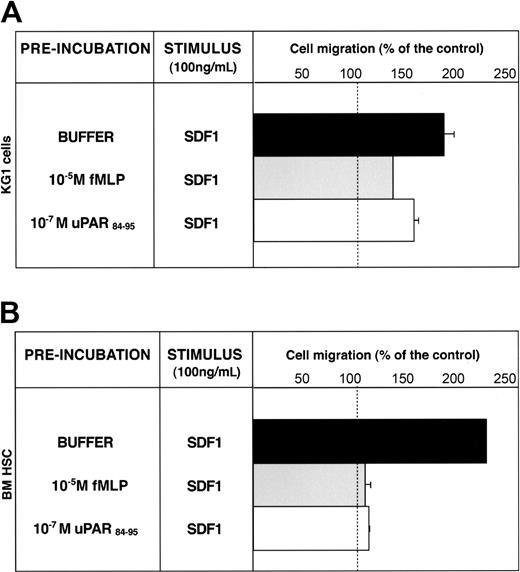

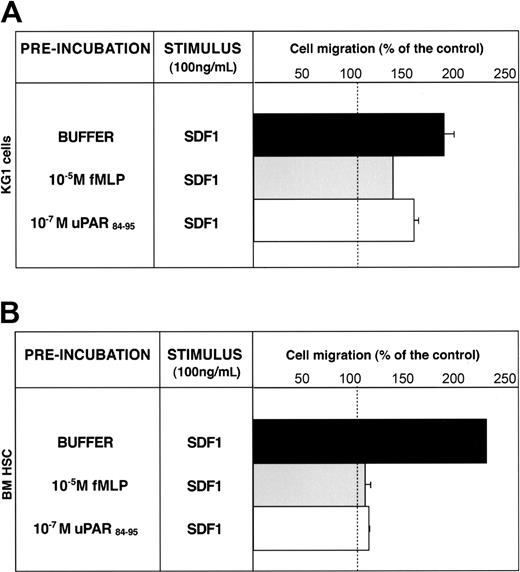

uPAR84-95 effect on SDF-1–dependent migration of CD34+ KG1 and hematopoietic stem cells

SDF1 is a potent chemoattractant for CD34+ HSCs, which express its receptor, CXCR4.30 Down-regulation of the CXCR4/SDF1 signal pathway increases CD34+ HSC mobilization.10,12,13,31 CXCR4 activity can be down-regulated by FPR and FPRL1 activation through heterologous desensitization.28,29 We investigated whether CD34+ KG1 and HSC migratory responses to SDF-1 could be modulated by uPAR84-95–mediated FPR activation. KG1 cells were able to migrate toward SDF1; preincubation with fMLP or uPAR84-95 reduced significantly (65% and 35%, respectively) the SDF1-dependent chemotaxis, likely by heterologous desensitization of CXCR4 (Figure 6A). Preincubation with the scrambled version of uPAR84-95 did not affect SDF1-dependent KG1 cell migration (cell migration, 180% ± 10% of control).

uPAR84-95 inhibits SDF-1–dependent migration of CD34+ KG1 and HSCs. KG1 cells (A) and bone marrow CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells (BM HSCs) (B), preincubated with buffer (▪), 10-5 M fMLP (▦), or 10-7 M uPAR84-95 (□), were plated in Boyden chambers and allowed to migrate toward 100 ng/mL SDF1. 100% values represent cell migration in the absence of chemoattractants. Values are the mean ± SD of 3 experiments performed in triplicate. Error bars are not shown when graphically too small.

uPAR84-95 inhibits SDF-1–dependent migration of CD34+ KG1 and HSCs. KG1 cells (A) and bone marrow CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells (BM HSCs) (B), preincubated with buffer (▪), 10-5 M fMLP (▦), or 10-7 M uPAR84-95 (□), were plated in Boyden chambers and allowed to migrate toward 100 ng/mL SDF1. 100% values represent cell migration in the absence of chemoattractants. Values are the mean ± SD of 3 experiments performed in triplicate. Error bars are not shown when graphically too small.

SDF1 also induced chemotaxis of BM CD34+ HSCs purified from 3 donors; pretreatment with fMLP or uPAR84-95 completely abolished SDF1-dependent migration (Figure 6B). These results suggest that serum c-suPAR in vivo can also regulate CD34+ HSC mobilization by down-modulating CXCR4 activity.

Effect of uPAR84-95 on clonogenic progenitors in long-term cultures

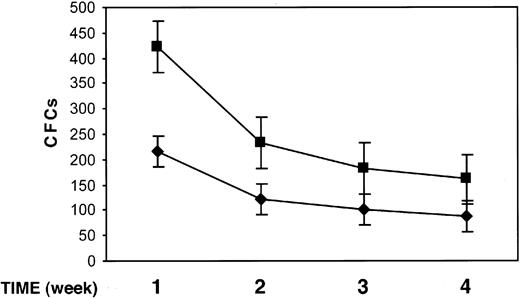

We studied the effect of uPAR84-95 on the output of clonogenic progenitors from LTCs of BM CD34+ cells. At present, LTCs represent the best surrogate in vitro of BM hematopoiesis in vivo because it mimics the complex intercellular interactions between the stromal microenvironment and stem cells concentrated in niches of hematopoietic activity. Highly purified BM CD34+ cells from 3 donors were plated on bone marrow–derived stroma, allowed to adhere, and cultured for 5 weeks. Each week, LTCs were treated with the uPAR84-95 peptide or its scrambled version for 2 hours, and the output of clonogenic progenitors was assayed by replating nonadherent cells in short-term cultures for a period of 5 weeks. Nonadherent cells, weekly harvested from uPAR84-95–treated LTCs, yielded a significantly higher number of clonogenic progenitors than those obtained from nonadherent cells of LTCs treated with the scrambled peptide (mean ± SD output of colony-forming cells [CFCs] after 1, 2, 3, and 4 weeks of LTC: 423 ± 24 compared with 215 ± 49, 233 ± 15 compared with 122 ± 15, 193 ± 12 compared with 112 ± 5, 161 ± 10 compared with 89 ± 7, respectively; P < .05 in all cases) (Figure 7). The number of secondary CFCs obtained after 5 weeks of LTCs, from nonadherent and from stroma-adherent cells, was reduced in LTCs treated with uPAR84-95, as compared to that of LTCs treated with the scrambled peptide, indicating the depletion of progenitor cells in uPAR84-95–treated LTCs (mean ± SD secondary CFCs, 18 ± 7 compared with 36 ± 5; P = .07).

uPAR84-95 increases the output of clonogenic progenitors in LTCs. The output of myeloid and erythroid colony-forming cells (CFCs), generated from LTCs of highly purified BM CD34+ cells, was measured by replating nonadherent cells in methylcellulose. Nonadherent cells were removed weekly after 2-hour LTC treatment with the uPAR84-95 (▪) peptide or its scrambled version ( ). Each value represents the mean ± SD of CFCs obtained from 3 independent experiments performed in duplicate.

). Each value represents the mean ± SD of CFCs obtained from 3 independent experiments performed in duplicate.

uPAR84-95 increases the output of clonogenic progenitors in LTCs. The output of myeloid and erythroid colony-forming cells (CFCs), generated from LTCs of highly purified BM CD34+ cells, was measured by replating nonadherent cells in methylcellulose. Nonadherent cells were removed weekly after 2-hour LTC treatment with the uPAR84-95 (▪) peptide or its scrambled version ( ). Each value represents the mean ± SD of CFCs obtained from 3 independent experiments performed in duplicate.

). Each value represents the mean ± SD of CFCs obtained from 3 independent experiments performed in duplicate.

These results indicate that the uPAR84-95 peptide induces an increased release of clonogenic progenitors from BM stroma in vitro, thus suggesting a similar effect of suPAR-cleaved forms in HSC mobilization in vivo.

Discussion

In the past few years, mobilized PB HSCs have replaced BM as the preferred source for transplantation; this procedure now accounts for up to 95% of all autologous transplantations and approximately 50% of allogeneic HSC transplantations in Europe and the United States.4 The use of a variety of mobilizing agents, including hematopoietic growth factors, myelosuppressive drugs, and chemokines, can dramatically increase the small number of HSCs present in the circulation during steady state hematopoiesis. Clinically, G-CSF is the most common HSC mobilizer in patients and healthy donors because of its potency and safety. Expression of G-CSF receptor on HSC is not required for mobilization, thus indicating that this cytokine acts through secondary pathways.51 G-CSF–induced HSC mobilization is a multistep process, likely involving at the beginning the activation of a subset of more mature hematopoietic cells. This initial step is followed by the generation of secondary signals by these activated cells, which, in turn, modulate HSC detachment from the BM microenvironment, motility, and subsequent migration and intravasation.4,51

Recent findings suggest that uPAR activity is causally involved at multiple steps in the proteolysis of extracellular basement membrane components in the migration and adhesion of normal and malignant cells.14-16 We found that G-CSF induced a significant increase of uPAR expression on CD33+ myeloid precursors and on CD14+ monocytic cells released from the BM into circulation during HSC mobilization, whereas CD34+ cells and T and B lymphocytes remained uPAR negative. In steady state conditions, uPAR expression on granulocytes was high and remained unchanged during G-CSF administration. The up-regulation of cell surface uPAR expression in CD33+ and CD14+ monocytic cells coincided with the increase of the soluble form of the receptor (suPAR) in donor serum, probably shed by PBMNCs. However, we cannot exclude that G-CSF–mobilized granulocytes, which express high levels of uPAR, could shed the receptor and contribute to its increase in serum. suPAR has been found in body fluids, such as urine and plasma of patients with various diseases, and their levels correlate with worsened prognoses.39,44-50 suPAR can be cleaved in the D1-D2 linker region by several proteases, such as metalloproteases, cathepsin G, and elastase, thus releasing the D1 domain and unmasking a region with chemotactic properties (residues 88-92).52,53 In our study, shed uPAR was in the intact and in the cleaved forms (c-suPAR) previously described,40,44,54,55 even if PBMNCs from G-CSF–treated donors expressed mainly the intact form of uPAR; this observation suggests that the cleavage of the receptor occurs after its release from the cell surface. Interestingly, G-CSF administration is associated with an increased release of MMP2 and MMP9 in BM and PB and of neutrophil cathepsin G and elastase in BM.56 Substrates of these proteases include several key molecules involved in HSC mobilization, such as vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1), c-kit receptor (CD117), CXCR4/SDF-1, and vascular endothelial-cadherin.56 Thus, these proteases could also be implicated in the generation of potentially chemotactic cleaved forms of suPAR detected in the serum of G-CSF–treated donors.

c-suPAR and its derived chemotactic peptide uPAR84-95, corresponding to the uPAR chemotactic region unmasked by D1-D2 cleavage,27 can induce monocyte chemotaxis by FPRL1 activation.23 FPRL1 belongs to the family of fMLP receptors; the other 2 members are FPR and FPRL2.24 Highly purified CD34+ cells express FPR and FPRL2 but not FPRL1 (Figure 4); we showed that uPAR84-95 induced BM HSC in vitro migration by the activation of FPR, even though we cannot exclude the involvement of other, as yet unknown, receptors.

We also provided evidence that c-suPAR, besides acting as an agonist for FPR, modulated the activity of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 in vitro. In fact, SDF-1–dependent BM HSC in vitro migration was impaired by uPAR84-95 through the activation of FPR, a chemotaxis receptor able to down-regulate the activity of CXCR4 by cross-desensitization.28,29 CXCR4 and its specific ligand SDF-1 strongly contribute to retain HSCs in BM; therefore, their inactivation seems to be critical for HSC mobilization,10,12,13,31,56 even though the role of active CXCR4 is still controversial.57 Recently, HSC mobilization was induced in healthy donors by a single dose of the pharmacologic antagonist of CXCR4 AMD3100.58

In BM LTCs, which closely mimic hematopoiesis in vivo, we found that the chemotactic peptide uPAR84-95 induced an increased release of erythroid and myeloid clonogenic progenitors from the stroma layer. The greatest increase occurred after 1 week of LTC, likely when stem cell niches have higher proliferative and differentiation capability, but it was still present all over the period of culture.

Our data document that, during G-CSF–induced HSC mobilization, uPAR expression is up-regulated on CD33+ and CD14+ cells, thus leading to increased uPAR shedding in the serum. suPAR could be rapidly cleaved by increased serum proteases, thus generating the chemotactically active form of suPAR. Serum c-suPAR could chemoattract BM CD34+ HSCs, thus inducing their migration into the circulation through a positive gradient. In addition, c-suPAR could also be generated in BM by the proteolytic action of neutrophil cathepsin G and elastase,12,13,56 where it could inactivate CXCR4 by cross-desensitization and promote HSC release from BM. These data suggest a new, unexpected role for c-suPAR in HSC mobilization.

Our results are also in agreement with the hypothesis that the processes of HSC mobilization and homing mirror hematopoietic cancer cell (HCC) trafficking from and to BM.59 In fact, increased levels of suPAR in plasma and of c-suPAR in BM and plasma have been reported in patients with acute myeloid leukemia,54 a disease in which these molecules could play the same role proposed for HSC mobilization.

Our findings suggest a potential usefulness of the cleaved form of suPAR, or its derived chemotactic peptide, in the strategies to optimize HSC mobilization, especially in G-CSF–poor mobilizers.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, October 19, 2004; DOI 10.1182/blood-2004-06-2424.

Supported by grants from the European Union Framework Program 6 (LSHC-CT-2003-503297), from the Ministero dell'Università e della Ricerca Scientifica e Tecnologica (MURST), and from AIL-Salerno.

C.S. and N.M. contributed equally to this work.

An Inside Blood analysis of this article appears in the front of this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

). Each value represents the mean ± SD of CFCs obtained from 3 independent experiments performed in duplicate.

). Each value represents the mean ± SD of CFCs obtained from 3 independent experiments performed in duplicate.