Abstract

The zinc finger transcription factor GATA-2 has been implicated in the regulation of hematopoietic stem cells. Herein, we explored the role of GATA-2 as a candidate regulator of the hematopoietic progenitor cell compartment. We showed that bone marrow from GATA-2 heterozygote (GATA-2+/−) mice displayed attenuated granulocyte-macrophage progenitor function in colony-forming cell (CFC) and serial replating CFC assays. This defect was mapped to the Lin−CD117+Sca-1−CD34+CD16/32high granulocyte-macrophage progenitor (GMP) compartment of GATA-2+/− marrow, which was reduced in size and functionally impaired in CFC assays and competitive transplantation. Similar functional impairments were obtained using a RNA interference approach to stably knockdown GATA-2 in wild-type GMP. Although apoptosis and cell-cycle distribution remained unperturbed in GATA-2+/− GMP, quiescent cells from GATA-2+/− GMP exhibited altered functionality. Gene expression analysis showed attenuated expression of HES-1 mRNA in GATA-2–deficient GMP. Binding of GATA-2 to the HES-1 locus was detected in the myeloid progenitor cell line 32Dcl3, and enforced expression of HES-1 expression in GATA-2+/− GMP rectified the functional defect, suggesting that GATA-2 regulates myeloid progenitor function through HES-1. These data collectively point to GATA-2 as a novel, pivotal determinant of GMP cell fate.

Introduction

Hematopoiesis is the process by which manifold blood and immune cell lineages are generated from hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells.1-3 A rare and relatively quiescent cell type that resides in the bone marrow, stem cells are either fated to self-renew, differentiate, or undergo apoptosis.3 Progenitor cells, on further differentiation, become progressively restricted to particular types of mature blood cells.1 Thus, a hierarchy of stem and progenitor cell compartments sustain hematopoiesis throughout the lifetime of an organism

Flow cytometry has facilitated the identification of the stem and progenitor cell compartments that form the hematopoietic hierarchy.4 This prospective isolation of stem and progenitor cell intermediates has also provided insights into paradigms of hematopoietic lineage commitment.5-7 Until recently, the prevailing model of lineage commitment was that a strict partition occurs between the myeloid and lymphoid lineages after a stem cell becomes a multipotent progenitor (MPP).5,6 In this model, lineage commitment occurs incipiently when a MPP differentiates to produce a common myeloid progenitor (CMP) or a common lymphoid progenitor (CLP). CMPs can make either a granulocyte-macrophage progenitor (GMP) or a megakaryocyte-erythrocyte progenitor (MEP).5 CLPs give rise to T, B, and natural killer cells.6 However, this model was recently challenged. For example, the Lin−Sca-1+CD117+CD135+CD34+ lymphoid-primed multipotent progenitor (LMPP) represents the earliest stage of bona fide commitment from a stem cell and exhibits granulocyte-macrophage and lymphoid potential but lacks megakaryocyte and erythroid potential.7 The Lin-Sca-1+CD117+CD135+VCAM-1+ compartment is akin to the LMPP in that it also displays robust myeloid and lymphoid potential without megakaryocyte or erythroid activity.8 Evidence from other laboratories further supports the contention that alternative pathways exist for myeloid commitment.9,10 Within the lymphoid lineage, apart from the CLP, several different prospectively isolated populations can give rise exclusively to the lymphoid lineages.11-13 Thus, the production of individual blood cell lineages may be perpetuated by multiple, overlapping cellular intermediates.

In addition to lineage commitment, the regulation of other stem cell fate decisions such as self-renewal and cell cycling has been extensively studied.2 However, considerably less attention has been paid to elucidating the operational cell fate decisions within the committed progenitor cell compartment. Knowledge of these mechanisms is important for multiple reasons. First, subtypes of committed progenitor cells are responsible for the generation of specific blood and immune cell types.14 Second, the committed progenitor pool provides immediate radioprotection and short-term reconstitution after bone marrow transplantation in mice, a characteristic that is relatively inefficient in the stem cell pool.15,16 Thus, progenitors may prove useful in obviating cytopenias that develop after bone marrow ablation in clinical bone marrow transplantation.16 Finally, the CMP and GMP compartments were shown to be vulnerable to leukemic transformation in a number of contexts.17-19 Understanding progenitor cell regulation may therefore offer insights into the salient cell fate decisions that are undermined during leukemogenesis.

The GATA family of transcription factors has been implicated in the regulation of progenitor cell fate decisions.1,20 A case in point is GATA-1, which has been acknowledged as a critical determinant of the proliferation, differentiation, and cell survival of the erythroid and megakaryocyte lineages.21-23 We and others have shown that another member of the GATA family, GATA-2, affects the cell fate decisions of both adult and developing stem cells.24-27 The possibility that GATA-2 may exert other functions within the hematopoietic system has been suggested by its expression pattern within myeloid-committed progenitors such as the CMP and GMP and its broad effect on the myeloid lineage using forced expression and loss of function approaches.28-30 Predicated on these studies, we selected GATA-2 as a candidate regulator of cell fate decisions within the myeloid cell compartment. In this report, we used 2 methods to attenuate GATA-2 level and identified a selective defect in the immunophenotypically defined GMP population.

Methods

Generation of GATA-2 heterozygote mice

GATA-2+/− mice in a 129SV background27 were used for all experiments except transplantation experiments in which GATA-2+/− was backcrossed into a CD45.1 background. Mice were housed in a barrier facility and fed ad libitum (Biomedical Services, John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, United Kingdom). Procedures were performed on sex-matched littermates aged 6 to 12 weeks old under conditions ratified by the United Kingdom Home Office in accordance with the Animals Scientific Procedure Act 1986 guidelines.

Colony-forming cell assay

M3434 (StemCell Technologies, London, United Kingdom) was supplemented with 10 μg/mL thrombopoietin where stated. Granulocyte macrophage–specific colony-forming cells (CFC-GMs) and pre–B-cell CFCs were performed in M3534 and M3630, respectively (StemCell Technologies).

Serial replating assay

Progenitors from primary CFC cultures were isolated by pipette and washed with IMDM 10% FCS. Primary colonies were plated in fresh CFC medium (StemCell Technologies) at a density of between 30 000 and 50 000 cells per well. This process was repeated for a total of 3 replatings.

Flow cytometry

Cell sorting of LMPP, CMP, and GMP progenitor populations and Annexin V and Hoechst (Hst) 33342 and Pyronin Y (PY) methods were performed as described previously.5,7,27 Further details are provided in Document S1 (available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

Cloning of short-hairpin RNAi oligonucleotides into lentilox

Short-hairpin RNA (shRNA) interference oligonucleotides (Invitrogen) were designed against mouse GATA-2. The cloning into pLlx3.7 was performed as described (web.mit.edu/ccr/labs/jacks/protocols/pll37cloning.htm).

HES-1 lentiviral vector

HES-1 cDNA was cloned into a dual promoter lentivector as described and validated previously (a gift from Dr Xiaobing Yu, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD).31

Lentivirus production and lentivirus transduction of CMP and GMP

Lentiviruses were pseudotyped with vesicular stomatitis virus G protein by transient transfection of 293T cells. Transduction of GMP and CMP was performed overnight in IMDM containing 10% FCS and 100 ng/mL mouse SCF, 20 ng/mL mouse IL-3, and 20 ng/mL mouse IL-6. After transduction, cells were washed and resuspended in fresh medium containing the same cytokines. GFP+ cells were sorted 40 hours after transduction. GFP+ cells were used in CFC assays and quantitative polymerase chain reaction (Q-PCR) as described.

Competitive transplantation

Competitive transplantation using the congenic CD45.1/45.2 system was used as described previously.32 Further details are provided in Document S1.

Quantitative real-time reverse-transcriptase PCR

RNA and cDNA was synthesized according to the manufacturer's instruction (QIAGEN, Crawley, United Kingdom, and Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, respectively). Template (2 ng) was used per Q-PCR reaction, and each reaction was carried out in duplicate. GATA-2, HES-1, and HPRT TaqMan Assays-On-Demand (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) primer/probe sets were used. Samples were analyzed in comparison to HPRT on an ABI analyzer (Applied Biosystems). Standard curves were run for each gene tested to analyze the efficiency of the PCR.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) experiments were performed as described previously.33 Further details are provided in Document S1.

Statistical analysis

Each experiment was statistically analyzed using a paired, 2-tailed Student t test.

Results

Altered frequency, self-renewal, and cell cycling of granulocyte-macrophage progenitors from GATA-2+/− bone marrow

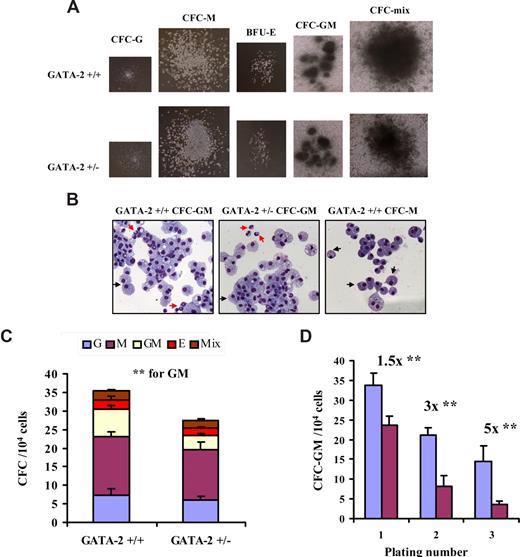

GATA-2+/– mice provide a tractable system to assess the effect of GATA-2 level on adult hematopoiesis. We and others have used the GATA-2+/− animal to examine the effect of GATA-2 on the stem cell compartment.26,27 In addition, a cursory examination of progenitor potential from GATA-2+/− marrow has alluded to a progenitor cell compartment defect in GATA-2+/− bone marrow.27 By using a multipotential colony-forming cell (CFC) assay, we first asked which progenitors within the myeloid series were affected in GATA-2+/− bone marrow. The morphologic characteristics of CFC-G, CFC-M, CFC-GM, erythroid burst-forming unit (BFU-E), and CFC-mix from GATA-2+/− and GATA-2+/+ marrow were comparable (Figure 1A,B). The proportion of CFC-G and CFC-M was unchanged between the GATA-2+/− and GATA-2+/+ genotypes (Figure 1C). In accordance with previous findings,27 the frequency of CFC-GMs was reduced in GATA-2+/−, whereas the abundance of BFU-Es remained unimpaired (Figure 1C). To analyze lymphopoietic progenitor activity in GATA-2+/− animals, pre-B CFC analysis was performed. No significant difference was observed in pre-B CFC potential between the genotypes (Figure S1). These data together show that only CFC-GM potential was reduced in GATA-2+/− marrow. Furthermore, these data suggest that the GM-specific progenitor defect in GATA-2+/− marrow was not merely because of the effect of GATA-2 on the stem cell compartment.

Attenuated formation and self-renewal capacity of granulocyte-macrophage progenitors from GATA-2+/− bone marrow. Bone marrow–nucleated cells from each genotype were plated in colony-forming medium supplemented with myeloid and erythroid growth factors and were assessed for granulocyte (CFC-G), macrophage (CFC-M), granulocyte-macrophage (CFC-GM), erythroid (E), and mixed (CFC-mix) colony formation. Three replicates were used per genotype in each experiment. Individual colony types were tallied on day 10. Representative colony types are depicted (A). May-Grünwald-Giemsa staining was used to confirm the lineage identity of individual colonies; typical morphologies of CFC-M and CFC-GM colonies from each genotype are depicted (B) (magnification ×40). Red arrows show the G lineage, and black arrows depict the M lineage. (A,B) The images were captured by the Axiovert 25 microscope (10× objective lens and a 4× eye piece; Zeiss, Welwyn Garden City, United Kingdom) using Immersol 518N mounting medium (Zeiss), May-Grünwald (Sigma, Dorset, United Kingdom) and Giemsa (Sigma) stains, a QIcam camera (QImaging, Pleasanton, CA), and Open Lab software (version 5.5; Coventry, United Kingdom). The cumulative score of specific lineages is shown (C) (n = 4; P = .01 for CFC-GM; CFC-G, P = .37; CFC-M, P = .08; BFU-E, P = .17; and CFC-mix, P = .43). To test the in vitro self-renewal potential of CFC-GMs from each genotype, marrow from GATA-2+/+ and GATA-2+/− animals was plated in granulocyte-macrophage–specific colony-forming medium. After 10 days, CFC-GM colonies were enumerated and replated into fresh granulocyte-macrophage-specific colony-forming medium. Secondary CFC-GM colonies were scored after 10 days in culture. The replating process was repeated to produce tertiary CFC-GM colonies. Three replicates were used per genotype in each experiment. The CFC-GM sequential replating potential of each genotype is depicted (D) (blue bar indicates GATA-2+/+; purple bar, GATA-2+/−) (1° n = 3, P = .02; 2° n = 3, P = .01; 3° n = 3, P = .04). Three replicates were used per genotype in each experiment. CFC-GM colonies were scored after 10 days in culture. ** indicates statistical significance. Error bars indicate SEM. All statistical analyses were performed using the paired Student t test.

Attenuated formation and self-renewal capacity of granulocyte-macrophage progenitors from GATA-2+/− bone marrow. Bone marrow–nucleated cells from each genotype were plated in colony-forming medium supplemented with myeloid and erythroid growth factors and were assessed for granulocyte (CFC-G), macrophage (CFC-M), granulocyte-macrophage (CFC-GM), erythroid (E), and mixed (CFC-mix) colony formation. Three replicates were used per genotype in each experiment. Individual colony types were tallied on day 10. Representative colony types are depicted (A). May-Grünwald-Giemsa staining was used to confirm the lineage identity of individual colonies; typical morphologies of CFC-M and CFC-GM colonies from each genotype are depicted (B) (magnification ×40). Red arrows show the G lineage, and black arrows depict the M lineage. (A,B) The images were captured by the Axiovert 25 microscope (10× objective lens and a 4× eye piece; Zeiss, Welwyn Garden City, United Kingdom) using Immersol 518N mounting medium (Zeiss), May-Grünwald (Sigma, Dorset, United Kingdom) and Giemsa (Sigma) stains, a QIcam camera (QImaging, Pleasanton, CA), and Open Lab software (version 5.5; Coventry, United Kingdom). The cumulative score of specific lineages is shown (C) (n = 4; P = .01 for CFC-GM; CFC-G, P = .37; CFC-M, P = .08; BFU-E, P = .17; and CFC-mix, P = .43). To test the in vitro self-renewal potential of CFC-GMs from each genotype, marrow from GATA-2+/+ and GATA-2+/− animals was plated in granulocyte-macrophage–specific colony-forming medium. After 10 days, CFC-GM colonies were enumerated and replated into fresh granulocyte-macrophage-specific colony-forming medium. Secondary CFC-GM colonies were scored after 10 days in culture. The replating process was repeated to produce tertiary CFC-GM colonies. Three replicates were used per genotype in each experiment. The CFC-GM sequential replating potential of each genotype is depicted (D) (blue bar indicates GATA-2+/+; purple bar, GATA-2+/−) (1° n = 3, P = .02; 2° n = 3, P = .01; 3° n = 3, P = .04). Three replicates were used per genotype in each experiment. CFC-GM colonies were scored after 10 days in culture. ** indicates statistical significance. Error bars indicate SEM. All statistical analyses were performed using the paired Student t test.

Because the CFC-GM compartment is a bi-potent hematopoietic progenitor, it shares some characteristics with its hematopoietic stem cell ancestors, including limited self-renewal potential. We used a serial replating assay in GM-specific CFC medium containing SCF, IL-3, and IL-6 to define whether self-renewal of CFC-GM from GATA-2+/− and GATA-2+/+ marrow was altered. As predicted, the abundance of primary CFC-GM from GATA-2+/− marrow was reduced by 1.5-fold (Figure 1D). On secondary and tertiary replating, however, the margin of reduction in CFC-GM numbers became progressively larger in the GATA-2+/− group (Figure 1D). These data show the perturbed self-renewal capacity of CFC-GM from GATA-2+/− marrow.

Given that GATA-2 has been implicated in cell cycling in multiple cell contexts,25-27,29,34 we posited that cell cycling may influence CFC-GM formation from GATA-2+/− marrow. To test this, we depleted cycling progenitors in vivo by administering a single 150 mg/kg dose of 5-flurouracil (5-FU) to GATA-2+/− and GATA-2+/+ animals35 and evaluated recovery of CFC-GM potential after 5-FU challenge for both genotypic groups at 4 days after 5-FU treatment (d4 5-FU). Marrow from d4 5-FU GATA-2+/− animals had substantially less CFC-GM than their wild-type counterparts (data not shown). Other types of myeloid CFC from d4 5-FU–challenged animals were comparable in both genotypes (data not shown). These data provide evidence for a functional defect in cell cycling that affects the GATA-2+/− GM compartment.

Immunophenotyping and functional analysis of hematopoietic progenitors from GATA-2+/− animals shows a numerical and functional defect that resides exclusively within the GMP population

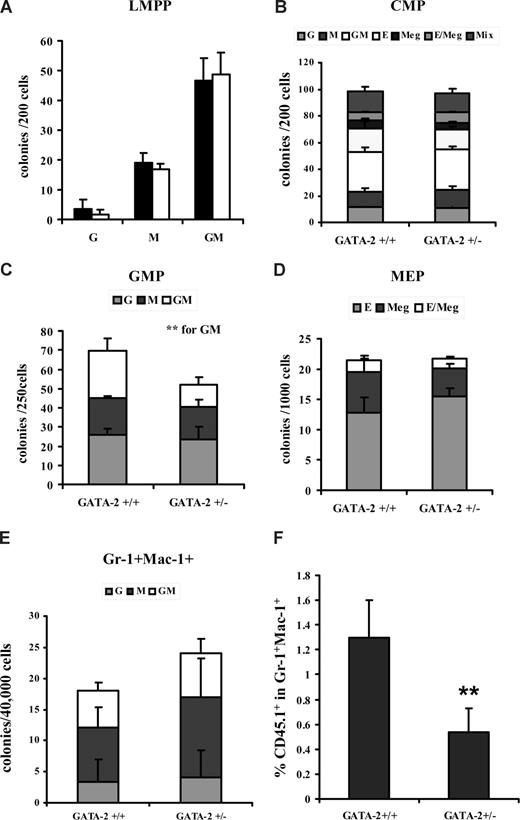

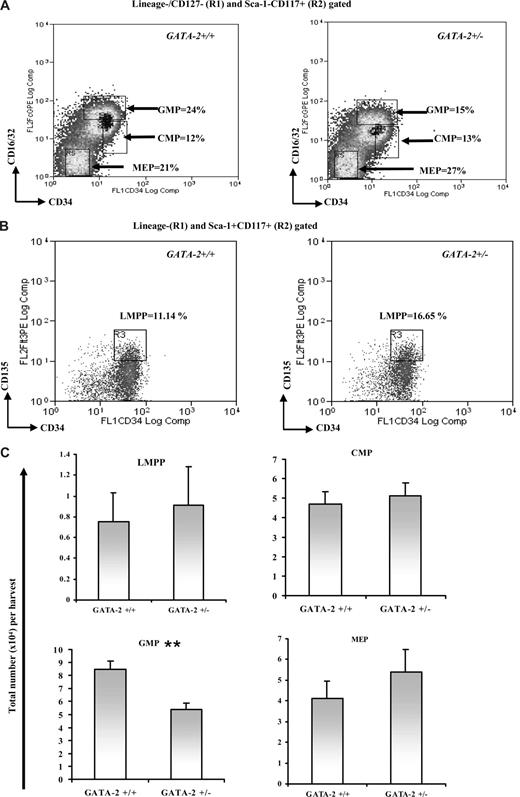

Having shown functional defects in the CFC-GM production from GATA-2+/− bone marrow, we chose to map the provenance of the CFC-GM defect to prospectively isolated myeloid progenitor subsets within the marrow. Q-PCR was first used to determine the level of GATA-2 in the CMP, GMP, and MEP compartments of both genotypes; this analysis showed an attenuated GATA-2 level within each population from the GATA-2+/− genotype (Figure S2). The number of CMPs, GMPs, and MEPs from each genotypic group was also assessed. Although the abundance of the GATA-2+/− CMP population remained unchanged in number, GMPs from GATA-2+/− animals were significantly attenuated (Figure 2A,C; Figure S3). The abundance of MEPs in GATA-2+/− animals tended to increase in the cohort of animals examined, although this pattern was found to be statistically insignificant (Figure 2A,C; Figure S3). We also examined the abundance of lymphoid-myeloid primed progenitors (LMPPs); similar proportions of LMPPs were found in GATA-2+/− and GATA-2+/+ marrow (Figure 2B,C). GM progenitors that appear later in the hematopoietic hierarchy such as Gr-1+Mac-1+, Gr-1+, or Mac-1+ were also enumerated, and no differences were found in these populations in GATA-2+/− and GATA-2+/+ marrow (data not shown). Parenthetically, the abundance of other myeloid and lymphoid lineages was unperturbed in GATA-2+/− marrow (data not shown). These data show that only the GMP compartment was numerically reduced in the GATA-2+/− marrow.

Reduction in the number of immunophenotypically defined GMPs from GATA-2+/− marrow. Bone marrow–nucleated cells from each genotype were lineage depleted using magnetic bead separation and lineage-negative–enriched cells were stained with various cell-surface antibodies to enable isolation of immunophenotypically defined progenitor subsets by flow cytometry. Representative flow cytometry plots for (Lin/CD127−CD117+Sca-1−CD34+CD16/32high) GMP, (Lin/CD127−CD117+Sca-1−CD34+CD16/32lo) CMP, and (Lin/CD127−CD117+Sca-1−CD34−CD16/32−) MEP isolation are shown (A) and for (Lin−CD117+Sca-1+Flt-3+CD34+) LMPP (B). The percentages for each gate are shown. The absolute number of LMPP, CMP, GMP, and MEP progenitors produced per harvest from multiple experiments is depicted (C) (LMPP, n = 4, P = .38; CMP, n = 9, P = .15; GMP, n = 9, P < .001<; and MEP, n = 9, P = .1). ** indicates statistical significance. Error bars indicate SEM. Statistical analysis was performed by using the paired Student t test.

Reduction in the number of immunophenotypically defined GMPs from GATA-2+/− marrow. Bone marrow–nucleated cells from each genotype were lineage depleted using magnetic bead separation and lineage-negative–enriched cells were stained with various cell-surface antibodies to enable isolation of immunophenotypically defined progenitor subsets by flow cytometry. Representative flow cytometry plots for (Lin/CD127−CD117+Sca-1−CD34+CD16/32high) GMP, (Lin/CD127−CD117+Sca-1−CD34+CD16/32lo) CMP, and (Lin/CD127−CD117+Sca-1−CD34−CD16/32−) MEP isolation are shown (A) and for (Lin−CD117+Sca-1+Flt-3+CD34+) LMPP (B). The percentages for each gate are shown. The absolute number of LMPP, CMP, GMP, and MEP progenitors produced per harvest from multiple experiments is depicted (C) (LMPP, n = 4, P = .38; CMP, n = 9, P = .15; GMP, n = 9, P < .001<; and MEP, n = 9, P = .1). ** indicates statistical significance. Error bars indicate SEM. Statistical analysis was performed by using the paired Student t test.

By using a multipotential CFC assay containing myeloid-, erythroid-, and megakaryocyte-specific growth factors, the GM functionality of prospectively isolated progenitors from GATA-2+/− and GATA-2+/+ marrow was assessed. CFC-G, CFC-M, and CFC-GM output was comparable in LMPPs, CMPs, and Gr-1+Mac-1+ from the 2 genotypes (Figure 3A,B,E). Relative parity was also observed in CFC-G and CFC-M output from GMPs (Figure 3C). In striking contrast, a reduction in CFC-GM formation was demonstrable from GATA-2+/− GMPs (Figure 3C). These experiments were repeated under GM-specific CFC conditions, and comparable results were obtained (data not shown). GATA-2+/− and GATA-2+/+ MEPs showed similar megakaryocyte and erythroid potential (Figure 3D). These data indicate an in vitro functional defect in GATA-2+/− animals at the level of the GMP.

GATA-2+/− marrow GMPs display impaired functionality in vitro and in vivo. Bone marrow–nucleated cells from each genotype were lineage depleted by using magnetic bead separation, and lineage-negative–enriched cells were stained with various cell surface antibodies to enable isolation of immunophenotypically defined progenitor subsets by cell sorting. LMPP, CMP, GMP, and MEP populations from each genotypic group were plated in colony-forming medium containing myeloid and erythroid growth factors. Three replicates were used per population per genotype in each experiment. The cumulative data for multiple experiments are shown: LMPP (A) (n = 2; P = not determined), CMP (B) (n = 5; G, P = .87; M, P = .61; GM, P = .93; E, P = .74; Meg, P = .45; E/Meg, P = .13; Mix, P = .49), GMP (C) (n = 5; G, P = .58; M, P = .6; GM, P = .03), MEP (D) (n = 5; E, P = .28; Meg, P = .3; E/Meg, P = .82), and Gr-1+Mac-1+ (E) (n = 3; G, P = .33; M, P = .28; GM, P = .37). In vivo functionality was assessed by using competitive transplantation of 10 000 GATA-2+/− or GATA-2+/+ GMP (B6SJL-CD45.1) and 150 C57BL/6-CD45.2 Lin-Sca-1+CD117+CD34− competitor stem cells into C57BL/6-CD45.2–irradiated recipients. Eight days after transplantation, the peripheral blood of recipient mice were analyzed for the contribution of donor CD45.1 within the Gr-1+Mac-1+ compartment by flow cytometry (F) (n = 5; P = .037). ** indicates statistical significance. Error bars indicate SEM. Statistical analysis was performed by using the paired Student t test.

GATA-2+/− marrow GMPs display impaired functionality in vitro and in vivo. Bone marrow–nucleated cells from each genotype were lineage depleted by using magnetic bead separation, and lineage-negative–enriched cells were stained with various cell surface antibodies to enable isolation of immunophenotypically defined progenitor subsets by cell sorting. LMPP, CMP, GMP, and MEP populations from each genotypic group were plated in colony-forming medium containing myeloid and erythroid growth factors. Three replicates were used per population per genotype in each experiment. The cumulative data for multiple experiments are shown: LMPP (A) (n = 2; P = not determined), CMP (B) (n = 5; G, P = .87; M, P = .61; GM, P = .93; E, P = .74; Meg, P = .45; E/Meg, P = .13; Mix, P = .49), GMP (C) (n = 5; G, P = .58; M, P = .6; GM, P = .03), MEP (D) (n = 5; E, P = .28; Meg, P = .3; E/Meg, P = .82), and Gr-1+Mac-1+ (E) (n = 3; G, P = .33; M, P = .28; GM, P = .37). In vivo functionality was assessed by using competitive transplantation of 10 000 GATA-2+/− or GATA-2+/+ GMP (B6SJL-CD45.1) and 150 C57BL/6-CD45.2 Lin-Sca-1+CD117+CD34− competitor stem cells into C57BL/6-CD45.2–irradiated recipients. Eight days after transplantation, the peripheral blood of recipient mice were analyzed for the contribution of donor CD45.1 within the Gr-1+Mac-1+ compartment by flow cytometry (F) (n = 5; P = .037). ** indicates statistical significance. Error bars indicate SEM. Statistical analysis was performed by using the paired Student t test.

Using the CD45.1/CD45.2 competitive transplantation system,5 we evaluated the in vivo functionality of GATA-2+/− and GATA-2+/+ GMPs. CD45.1 GATA-2+/− or GATA-2+/+ GMPs (104) were admixed with 150 CD45.2 Lin-Sca-1+CD117+CD34− competitor stem cells and intravenously infused into a CD45.2-irradiated recipient. At 8 days after transplantation, the peripheral blood of recipients was sampled, and, using flow cytometry, donor cell contribution (CD45.1) was analyzed in the Gr-1+Mac-1+ myeloid compartment. In comparison to GATA-2+/+ GMP transplant recipients, those recipients receiving GATA-2+/− GMP cells displayed a marked attenuation in the proportion of CD45.1+ within the Gr-1+Mac-1+ compartment (Figure 3F). Transplantation of CMPs from the GATA-2+/− genotype into irradiated recipients did not show altered functionality within this compartment (data not shown). The reduced functionality of GATA-2+/− GMP transplant recipients could not be imputed to homing defects; no difference was observed in the donor GMP content in the marrow of transplant recipients (data not shown). Together with the aforementioned numerical reduction in GMPs from GATA-2+/− animals, these data show that the GATA-2+/− genotype evinces a functional defect that resides solely within the GMP compartment.

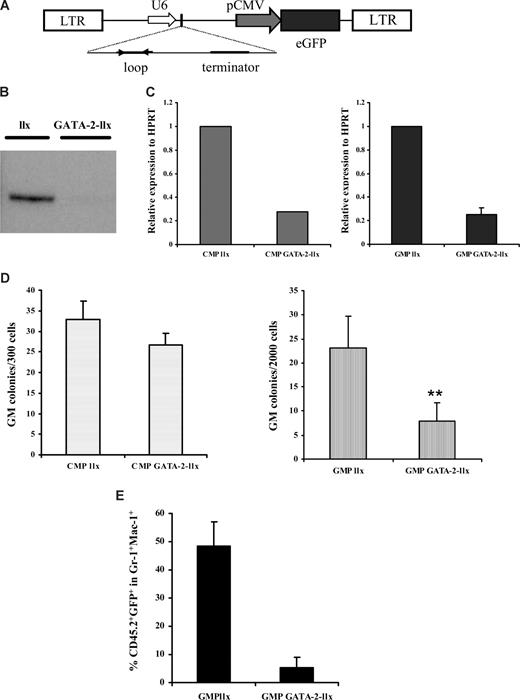

Abrogation of GATA-2 in wild-type GMPs by lentivirus-mediated short-hairpin RNAi impairs functionality

The preceding data unequivocally show that GATA-2+/− mice exhibit a GMP progenitor defect. The lack of a CMP defect in GATA-2+/− animals suggests that the observed phenotype of GATA-2+/− GMPs is independent of the known GATA-2+/− stem cell defect. Whether the GATA-2+/− GMP phenotype arises from a specification defect during hematopoietic differentiation, however, remains an open question. Furthermore, the isolation and characterization of GMPs from GATA-2+/− animals may be affected if GATA-2 target genes include cell-surface receptors used in sorting this population. Bearing these issues in mind, we adopted a complementary strategy to probe GATA-2 function in adult GMPs. To this end, we cloned short-hairpin (sh) RNA oligonucleotides directed against mouse GATA-2 into the lentilox 3.7 lentiviral vector (llx) linked to a GFP reporter (Figure 4A). Sequence alignment verified that these oligonucleotides were specifically directed against GATA-2 and not other GATA factors such as GATA-1 (data not shown). The knockdown virus (GATA-2–llx) displayed reduced GATA-2 protein expression in comparison to the empty vector (llx) in the factor-dependent BAF3 hematopoietic cell line (Figure 4B). Furthermore, wild-type CMPs and GMPs transduced with the GATA-2–llx expressed reduced GATA-2 mRNA (Figure 4C). These data validate the use of GATA-2–llx to achieve knockdown of GATA-2 in myeloid-committed progenitors.

Knockdown of GATA-2 in wild-type GMPs by lentivirus-mediated RNA interference impairs function in vitro and in vivo. A schematic representation of the lentilox (llx) construct used to knock down GATA-2 is shown (A). Western blot analysis of GFP+ BAF-3 cells shows knockdown of GATA-2 (B). Bone marrow–nucleated cells from wild-type animals were sorted for CMP and GMP and transduced with either control vector (llx) or GATA-2–llx. After transduction, CMP and GMP from llx or GATA-2–llx were subjected to a reverse-transcription reaction and Q-PCR to determine the extent of GATA-2 knockdown (C). GFP+ cells from llx or GATA-2-llx–transduced CMPs and GMPs were plated in colony-forming medium containing myeloid, megakaryocyte, and erythroid growth factors. Individual colony types were tallied on day 10, and granulocyte-macrophage progenitors are depicted (D) (CMP, n = 4, P = .28; GMP, n = 4, P = .01). To assess in vivo functionality, irradiated B6SJL-CD45.1 mice were transplanted with C57BL/6-CD45.2 GMPs transduced with either llx or GATA-2–llx along with competing C57BL/6-CD45.1 Lin-Sca-1+CD117+CD34− stem cells. A proportion of transduced cells from each group were cultured for a further 2 days to allow a retrospective analysis of GFP+ cells transplanted initially. Eight days after transplantation, the peripheral blood of recipient mice were analyzed for the contribution of donor CD45.2 and GFP positivity within the Gr-1+Mac-1+ compartment by flow cytometry The cumulative data of multiple recipients (n = 3; P = ND) from 2 separate experiments is shown (E). Error bars indicate SEM. ** indicates statistical significance. Statistical analysis was performed by using the paired Student t test.

Knockdown of GATA-2 in wild-type GMPs by lentivirus-mediated RNA interference impairs function in vitro and in vivo. A schematic representation of the lentilox (llx) construct used to knock down GATA-2 is shown (A). Western blot analysis of GFP+ BAF-3 cells shows knockdown of GATA-2 (B). Bone marrow–nucleated cells from wild-type animals were sorted for CMP and GMP and transduced with either control vector (llx) or GATA-2–llx. After transduction, CMP and GMP from llx or GATA-2–llx were subjected to a reverse-transcription reaction and Q-PCR to determine the extent of GATA-2 knockdown (C). GFP+ cells from llx or GATA-2-llx–transduced CMPs and GMPs were plated in colony-forming medium containing myeloid, megakaryocyte, and erythroid growth factors. Individual colony types were tallied on day 10, and granulocyte-macrophage progenitors are depicted (D) (CMP, n = 4, P = .28; GMP, n = 4, P = .01). To assess in vivo functionality, irradiated B6SJL-CD45.1 mice were transplanted with C57BL/6-CD45.2 GMPs transduced with either llx or GATA-2–llx along with competing C57BL/6-CD45.1 Lin-Sca-1+CD117+CD34− stem cells. A proportion of transduced cells from each group were cultured for a further 2 days to allow a retrospective analysis of GFP+ cells transplanted initially. Eight days after transplantation, the peripheral blood of recipient mice were analyzed for the contribution of donor CD45.2 and GFP positivity within the Gr-1+Mac-1+ compartment by flow cytometry The cumulative data of multiple recipients (n = 3; P = ND) from 2 separate experiments is shown (E). Error bars indicate SEM. ** indicates statistical significance. Statistical analysis was performed by using the paired Student t test.

We tested the functionality of wild-type GMPs transduced with GATA-2–llx or llx in CFC assays. Fitting with the functional data obtained in GATA-2+/− GMPs, wild-type GMPs transduced with GATA-2–llx were reduced in CFC-GM (Figure 4D) but not CFC-G or CFC-M capability (data not shown). Furthermore, wild-type CMPs transduced with GATA-2–llx showed normal distribution of CFC-GMs (Figure 4D) and all other lineages in this assay (data not shown). Competitive transplantation experiments were performed to assess the in vivo functionality of wild-type GMPs transduced with GATA-2–llx or llx. CD45.2 wild-type GMPs transduced with either GATA-2–llx or llx were admixed with CD45.1 Lin-Sca-1+CD117+CD34− competitor stem cells and transplanted into CD45.1-irradiated recipients. Peripheral blood of transplant recipients was sampled at 8 days after transplantation, and donor-cell contribution was analyzed with flow cytometry. In agreement with the results obtained in the CFC assays, the proportion of CD45.2+ GFP+ within the Gr-1+Mac-1+ cell compartment was sharply reduced in recipients that received transplants of wild-type GMPs transduced with GATA-2–llx (Figure 4E). The peripheral blood of recipients that received transplants of wild-type CMPs transduced with either GATA-2–llx or llx exhibited comparable CD45.2+ GFP+ content within the Gr-1+Mac-1+ cell compartment (data not shown). Thus, irrespective of the method used to attenuate GATA-2 in myeloid progenitors, GATA-2 level selectively affects the function of the GMP compartment. Furthermore, our data argue (1) for a specific role for GATA-2 within myeloid cell lineage acting at the level of the GMP compartment and (2) against the requirement for GATA-2 in the specification of GMPs during hematopoiesis.

Unimpaired apoptosis from GATA-2+/− GMPs under homeostasis and during cytokine stimulation

With the GATA-2+/− model, we investigated the mechanisms by which GATA-2 regulates cell fate within the GMP compartment. The diminished size of the immunophenotypically defined GATA-2+/− GMP pool may be caused by augmented cell death; thus, apoptosis was evaluated in GMP cells using the annexin V assay.36 The GMP compartment from GATA-2+/− freshly isolated marrow showed a minimal numerical difference between the annexinhigh/DNA dyelow population compared with GATA-2+/+ marrow, indicating that the GATA-2+/− GMP does not have an increased predilection to undergo apoptosis (Figure S4A,B). The CMP compartment of GATA-2+/− animals was similarly unaffected (Figure S4A,B). These data imply that altered cell survival does not contribute to the reduced size of the GATA-2+/− GMP compartment.

The reduction of CFC-GM in the GATA-2+/− GMP genotype may be ascribable to increased apoptosis under conditions of cytokine stimulation. To model whether GMPs were more susceptible to apoptosis during the culture, GMP cells from each genotype were subjected to liquid culture under GM-specific conditions (SCF, IL-3, and IL-6). After up to 4 days in culture, the annexin V assay was performed on Gr-1 Mac-1+ cells, and no difference was detected between the genotypes in terms of the proportion of annexin Vhigh/DNA dye− fraction within this population (Figure S4C,D). The apoptotic fraction of CMPs from both genotypes also remained unchanged (Figure S4C,D). These data argue that under cytokine stimulation GATA-2+/− GMP retains intact characteristics of cell survival.

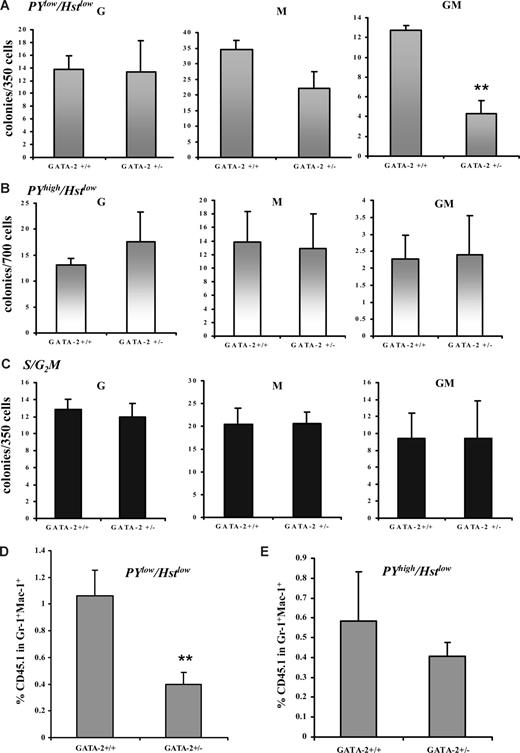

Disruption of self-renewal and alteration in PYlow/Hstlow cell function in GATA-2+/− GMP

To test the self-renewal ability of GATA-2+/− GMPs, serial replating of GMPs was performed. Primary plating of the colonies produced similar results to that in Figure 3C. Secondary plating of the colonies after 10 days, however, exacerbated the decrease in CFC-GM formation from GATA-2+/− animals (Figure 5C). Secondary plating of colonies emanating from LMPPs and CMPs of GATA-2+/− animals, in contrast, showed no significant difference in secondary GM colony formation (Figure 5A,B). Therefore, the self-renewal potential of GATA-2+/− GMPs, as judged by serial replating, was severely disrupted.

Impaired self-renewal of granulocyte-macrophage progenitors derived from GMPs of GATA-2+/− marrow. LMPP, CMP, and GMP populations were sorted from each genotypic group and plated in colony-forming medium containing growth factors that were permissive for granulocyte-macrophage colony formation. After 10 days, CFC-GM colonies were enumerated and replated into fresh colony-forming medium. Secondary CFC-GM colonies were scored after 10 days in culture. The replating process was repeated an additional time to yield tertiary CFC-GM colonies. Three replicates were used per population per genotype in each experiment. The CFC-GM sequential replating potential of LMPP (A) (n = 4; P > .05), CMP (B) (n = 4; P > .05), and GMP (C) (n = 4; P < .05) from each genotype is depicted. ** indicates statistical significance. Error bars indicate SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using the paired Student t test.

Impaired self-renewal of granulocyte-macrophage progenitors derived from GMPs of GATA-2+/− marrow. LMPP, CMP, and GMP populations were sorted from each genotypic group and plated in colony-forming medium containing growth factors that were permissive for granulocyte-macrophage colony formation. After 10 days, CFC-GM colonies were enumerated and replated into fresh colony-forming medium. Secondary CFC-GM colonies were scored after 10 days in culture. The replating process was repeated an additional time to yield tertiary CFC-GM colonies. Three replicates were used per population per genotype in each experiment. The CFC-GM sequential replating potential of LMPP (A) (n = 4; P > .05), CMP (B) (n = 4; P > .05), and GMP (C) (n = 4; P < .05) from each genotype is depicted. ** indicates statistical significance. Error bars indicate SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using the paired Student t test.

The cell-cycle status of GMPs from the 2 genotypes was assessed by isolating GMPs by flow cytometry and staining with the DNA dye Hoechst 33342 (Hst).37 The proportion of cells in G0/G1 and SG2/M from the GMP compartment was unchanged between GATA-2+/− and GATA-2+/+ genotypes (Figure S5). Similar results were obtained with the CMP compartment (data not shown). To specifically discriminate between the proportion of cells in G0 and G1 within the GMP population, the RNA dye, Pyronin Y (PY), was used to measure cell quiescence within Hstlow (G0/G1) cells.27 No significant alteration was observed in the PYlow Hstlow staining of GMP cells from the GATA-2+/− genotype (Figure S5). Furthermore, no significant alteration was observed in the PYlow Hstlow staining of CMP cells from the GATA-2+/− genotype (data not shown). Bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation experiments were also performed in GATA-2+/+ and GATA-2+/− animals. Congruent with the results of Hst and PY/Hst analyses, the incorporation of BrdU into the GMPs or CMPs of GATA-2+/− or GATA-2+/+ was comparable at multiple time points after BrdU administration (data not shown). Therefore, several lines of evidence indicate that the abundance of quiescent cells and cycling cells was unaltered within the GMP compartment of GATA-2+/− mice.

Next, we tested the in vitro function of the various cell-cycle compartments in the GATA-2+/− GMPs. GMPs from each genotype were prospectively isolated by flow cytometry and either stained with Hst dye or with a combination of PY/Hst; the S/G2M, G0 (hereafter PYlow Hstlow) or G1 (hereafter PYhigh Hstlow) compartments were isolated by cell sorting and plated in a multipotential CFC assay. To ensure stringency of G0 compared with G1 gating in functional experiments, progenitors were sorted and analyzed for the presence of the nuclear proliferation marker Ki-67; as expected, putative G0 cells failed to appreciably express Ki-67, whereas it was up-regulated in G1 cells (Figure S5). CFC-G, -M, and -GM production from each genotype was unaltered within the S/G2M fraction (Figure 6C). PYlow Hstlow and PYhigh Hstlow cells from GATA-2+/− and GATA-2+/+ GMPs were not significantly altered in their capacity to form CFC-Gs (Figure 6A,B). PYhigh Hstlow from both genotypes also displayed normal CFC-M frequency (Figure 6B). PYlow Hstlow cells from GATA-2+/− GMPs displayed a slight, insignificant reduction in CFC-M number (Figure 6A). In contrast, a prodigious reduction in CFC-GM number was noted in the PYlow Hstlow fraction of GATA-2+/− GMP (Figure 6A). As predicted, PYlow Hstlow, PYhigh Hstlow, and S/G2M CMPs from GATA-2+/− mice produced all progenitor lineages at a comparable frequency to their wild-type counterparts (Figure S6). Using competitive transplantation, we also evaluated the in vivo function of PY/Hst-defined populations in GMPs from GATA-2+/− and GATA-2+/+ animals. Corresponding to the CFC analysis, donor blood cell contribution (CD45.1) in the Gr-1+Mac-1+ myeloid compartment at 8 days after transplantation was reduced in the PYlow Hstlow compartment of GMPs from GATA-2+/− mice (Figure 6D). Donor blood cell contribution within the Gr-1+Mac-1+ compartment of recipients of transplants of PYhigh Hstlow GMP cells was similar for the 2 genotypes (Figure 6E). Likewise, recipients of transplants of PYlow Hstlow or PYhigh Hstlow CMPs from GATA-2+/− animals displayed normal donor blood cell contribution within the Gr-1+Mac-1+ myeloid lineage (data not shown). Taken together, these data show that only the PYlow Hstlow GMPs from GATA-2+/− animals were functionally impaired in vitro and in vivo.

Impaired in vitro and in vivo functionality of Pyroninlow/Hoechstlow GMPs from GATA-2+/− marrow. GMPs from GATA-2+/+ and GATA-2+/− bone marrow were isolated by cell sorting and were subsequently stained with the RNA dye Pyronin Y (PY) and DNA dye Hoechst 33342 (Hst). Flow cytometry was performed to distinguish the PYlo or PYhigh in the G0/G1 fraction (Hstlow). Cells residing in PYlow/Hstlow or PYhigh/Hstlow were sorted and plated into colony-forming medium containing myeloid, megakaryocyte, and erythroid growth factors. Three replicates were used per genotype in each experiment. Colony formation was scored on day 10 (A) (B) GMPs from GATA-2+/+ and GATA-2+/− bone marrow were isolated by sorting and were subsequently stained with the DNA dye Hoechst 33342 (Hst) to enable discrimination of G0/G1 and S/G2/M populations The S/G2/M population was sorted and plated into colony-forming medium containing myeloid, megakaryocyte, and erythroid growth factors. Three replicates were used per genotype in each experiment. Colony formation was scored on day 10 (C). Data from multiple experiments are displayed (A-C) (PYlow/Hstlow, n = 5; G, P = .92; M, P = .06; GM, P = .002; PYhigh/Hstlow, n = 5; G, P = .47; M, P = .85; GM, P = .83; S/G2/M, n = 6; G, P = .71; M, P = .97; GM, P = .99). In vivo functionality was assessed by competitive transplantation of PYlow/Hstlow or PYhigh/Hstlow GMPs from each genotype (B6SJL-CD45.1) with C57BL/6-CD45.2 Lin-Sca-1+CD117+CD34− competitor stem cells into C57BL/6-CD45.2–irradiated recipients. Eight days after transplantation, the peripheral blood of the recipient mice were analyzed for the contribution of donor CD45.1 within the Gr-1+Mac-1+ compartment by flow cytometry. Data from multiple experiments are displayed for PYlow/Hstlow (D) (n = 3; P = .042) and PYhigh/Hstlow (E) (n = 3; P = .31). ** indicates statistical significance. Error bars indicate SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using the paired Student t test.

Impaired in vitro and in vivo functionality of Pyroninlow/Hoechstlow GMPs from GATA-2+/− marrow. GMPs from GATA-2+/+ and GATA-2+/− bone marrow were isolated by cell sorting and were subsequently stained with the RNA dye Pyronin Y (PY) and DNA dye Hoechst 33342 (Hst). Flow cytometry was performed to distinguish the PYlo or PYhigh in the G0/G1 fraction (Hstlow). Cells residing in PYlow/Hstlow or PYhigh/Hstlow were sorted and plated into colony-forming medium containing myeloid, megakaryocyte, and erythroid growth factors. Three replicates were used per genotype in each experiment. Colony formation was scored on day 10 (A) (B) GMPs from GATA-2+/+ and GATA-2+/− bone marrow were isolated by sorting and were subsequently stained with the DNA dye Hoechst 33342 (Hst) to enable discrimination of G0/G1 and S/G2/M populations The S/G2/M population was sorted and plated into colony-forming medium containing myeloid, megakaryocyte, and erythroid growth factors. Three replicates were used per genotype in each experiment. Colony formation was scored on day 10 (C). Data from multiple experiments are displayed (A-C) (PYlow/Hstlow, n = 5; G, P = .92; M, P = .06; GM, P = .002; PYhigh/Hstlow, n = 5; G, P = .47; M, P = .85; GM, P = .83; S/G2/M, n = 6; G, P = .71; M, P = .97; GM, P = .99). In vivo functionality was assessed by competitive transplantation of PYlow/Hstlow or PYhigh/Hstlow GMPs from each genotype (B6SJL-CD45.1) with C57BL/6-CD45.2 Lin-Sca-1+CD117+CD34− competitor stem cells into C57BL/6-CD45.2–irradiated recipients. Eight days after transplantation, the peripheral blood of the recipient mice were analyzed for the contribution of donor CD45.1 within the Gr-1+Mac-1+ compartment by flow cytometry. Data from multiple experiments are displayed for PYlow/Hstlow (D) (n = 3; P = .042) and PYhigh/Hstlow (E) (n = 3; P = .31). ** indicates statistical significance. Error bars indicate SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using the paired Student t test.

HES-1 contributes to GATA-2–mediated regulation of myeloid progenitor cell function.

To explore the molecular mechanisms that underscore the functional defects in GATA-2+/− GMPs, we surveyed the expression of candidate genes associated in these processes by Q-PCR. Of these genes, p21, p27, cyclin D2, all of which have been associated with granulocyte-macrophage function,38-40 showed no discernible alteration in expression in the GMPs from both genotypes (data not shown). Other components of the cell-cycle machinery expressed in the GMPs,41 such as cyclin A2 and cyclin B2, were also unchanged between the 2 genotypes (data not shown). However, HES-1, a bHLH Notch target gene that affects both hematopoietic cell self-renewal and cell-cycle status,31,42 was decreased in GATA-2+/− GMPs (Figure 7A). In addition, GATA-2-llx–transduced GMP showed reduced expression of HES-1 (Figure 7B). These data raise the possibility that GATA-2 regulates GMP function, in part, through HES-1 signaling.

Hes-1 contributes to GATA-2–mediated regulation of myeloid progenitor cell function. RNA prepared from the GMPs of each genotype was subjected to reverse-transcriptase reaction, and Q-PCR for Hes-1 was performed (A). Results were normalized to HPRT. Triplicates were used for each PCR, and the figures represent 4 experiments ± SEM (P = .005). RNA was prepared from GFP+ cells of GMPs that were transduced with either llx and llx–GATA-2. These RNA samples were subjected to a reverse-transcriptase reaction, and Q-PCR for Hes-1 was performed. Results were normalized to HPRT (B) (n = 2; P = not determined). ChIP experiments in 32Dcl3 cells showed that GATA-2 binds directly to the HES-1 locus. Four putative GATA-binding sites were tested, one of which was preferentially enriched by the anti–GATA-2 antibody (primer set 4). ChIP material was analyzed by SYBRGreen qPCR; data are the mean of 4 experiments read in duplicate. Results are represented as enrichments over nonspecific binding by total rabbit IgG after normalization to a control sequence (exon 4 of HES-1). (C) Bone marrow–nucleated cells from each genotype were sorted for GMPs and transduced with either empty vector or HES-1. GFP+ cells from each genotype were plated in colony-forming medium containing myeloid, megakaryocyte, and erythroid growth factors. Granulocyte-macrophage progenitors were tallied on day 10 and are depicted (D) (n = 3; GATA-2+/+ empty vector vs GATA-2+/− empty vector, P = .047; GATA-2+/− empty vector vs GATA-2+/−HES-1, P = .049). ** indicates statistical significance. Error bars indicate SEM. Statistical analysis was performed by using the paired Student t test.

Hes-1 contributes to GATA-2–mediated regulation of myeloid progenitor cell function. RNA prepared from the GMPs of each genotype was subjected to reverse-transcriptase reaction, and Q-PCR for Hes-1 was performed (A). Results were normalized to HPRT. Triplicates were used for each PCR, and the figures represent 4 experiments ± SEM (P = .005). RNA was prepared from GFP+ cells of GMPs that were transduced with either llx and llx–GATA-2. These RNA samples were subjected to a reverse-transcriptase reaction, and Q-PCR for Hes-1 was performed. Results were normalized to HPRT (B) (n = 2; P = not determined). ChIP experiments in 32Dcl3 cells showed that GATA-2 binds directly to the HES-1 locus. Four putative GATA-binding sites were tested, one of which was preferentially enriched by the anti–GATA-2 antibody (primer set 4). ChIP material was analyzed by SYBRGreen qPCR; data are the mean of 4 experiments read in duplicate. Results are represented as enrichments over nonspecific binding by total rabbit IgG after normalization to a control sequence (exon 4 of HES-1). (C) Bone marrow–nucleated cells from each genotype were sorted for GMPs and transduced with either empty vector or HES-1. GFP+ cells from each genotype were plated in colony-forming medium containing myeloid, megakaryocyte, and erythroid growth factors. Granulocyte-macrophage progenitors were tallied on day 10 and are depicted (D) (n = 3; GATA-2+/+ empty vector vs GATA-2+/− empty vector, P = .047; GATA-2+/− empty vector vs GATA-2+/−HES-1, P = .049). ** indicates statistical significance. Error bars indicate SEM. Statistical analysis was performed by using the paired Student t test.

To determine whether GATA-2 binds to the HES-1 locus in vivo, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) experiments in an IL-3–dependent murine myeloid cell line 32Dcl3. Four putative GATA-binding sites were tested, one of which was preferentially enriched by the anti–GATA-2 antibody (Figure 7C primer set 4). This region lies 2.3 kb downstream of the termination codon of HES-1. This result shows that GATA-2 binds directly to the HES-1 locus in myeloid progenitor cells.

By enforcing expression of HES-1 using a dual-promoter lentiviral vector system,31 we finally evaluated whether HES-1 expression was able to rescue the functional defect in GATA-2+/− GMPs. GATA-2+/− and wild-type GMPs were transduced with either empty vector or HES-1 and tested functionally in CFC-GM assays. Western blot analysis of pooled CFCs derived from empty vector or HES-1–transduced GMPs from both genotypes confirmed expression of HES-1 and the rescue of HES-1 in GATA-2+/− GMPs (data not shown). Empty vector–transduced GATA-2+/− GMPs were significantly reduced in CFC-GM potential compared with wild-type GMPs transduced with empty vector (Figure 7D). In striking contrast, GATA-2+/− GMPs transduced with HES-1 displayed equivalent CFC-GM potential to that from wild-type GMPs transduced with HES-1. Of particular note, enforced expression of HES-1 rescued CFC-GM functionality in GATA-2+/− GMPs to approximately the level produced by wild-type GMPs transduced with empty vector. These data show that reexpression of HES-1 can rectify the functional defect in GATA-2+/− GMPs and suggest a crucial regulatory role for the GATA-2–HES-1 signaling axis in the GMP compartment.

Discussion

In this study, we used GATA-2+/− animals to investigate a potential role for GATA-2 in the regulation of the myeloid cell compartment and found a granulocyte-macrophage–specific defect within the bone marrow of these animals. The provenance of this defect was mapped to the immunophenotypically defined GMP compartment, which was found to be smaller and less able to perform in functional assays. An RNA interference approach against mouse GATA-2 in the wild-type GMP compartment corroborated this effect independently. In stark contrast, other compartments endowed with granulocyte-macrophage potential, such as the CMP and LMPP, were unaffected by GATA-2 deficiency. These data conjointly unveil an important regulatory role for GATA-2 in the GMP compartment. That the defects associated with abrogating GATA-2 level in GMPs were manifest in CFC assays and myeloablative competitive transplantation additionally suggests that GATA-2–mediated regulation of the GMP compartment may be more pertinent to stress hematopoiesis than to steady-state hematopoiesis.

The possibility that the GATA-2+/− granulocyte-macrophage phenotype may simply be a corollary of the GATA-2+/− stem cell deficit is not supported by the data presented here. Incomplete compensation of the GATA-2+/− stem cell deficit may, a priori, be predicted to affect both lymphoid and myeloid progenitor lineages. This was not found to be the case because committed lymphoid progenitors, as assessed by flow cytometry and CFC-B assays, were unimpaired in GATA-2+/− marrow. Although other lymphoid organs and earlier bone marrow lymphoid progenitors such as the CLP were not examined, the data presented in this report argue that GATA-2 specifically affects the myeloid cell compartment. Furthermore, the GATA-2+/− myeloid defect presented itself exclusively within the GMP compartment, whereas other myeloid compartments were unchanged. Predicated on these observations, we propose that GATA-2 is required at differentiation stage–specific levels of the hematopoietic hierarchy, acting separately at the stem cell and GMP level.

GATA-2 heterozygosity compromised functionality with the subversion of GM self-renewal from the GMP compartment. The overt disruption of GATA-2+/− GMP self-renewal contrasts with the intact self-renewal observed within the GATA-2+/− stem cell compartment.27 Likewise, stem cell apoptosis was enhanced in the GATA-2+/− genotype, whereas no such alteration was noted in the GATA-2+/− GMP compartment.27 These data together imply that GATA-2 determines cell fate options in hematopoiesis in a cell context–dependent manner. So why does GATA-2 mediate ostensibly different functions in the stem and progenitor cell compartments? Part of the explanation may sit with the cell types in which GATA-2 is expressed; stem and progenitor cell pools express distinct transcription factors, thus, GATA-2 may interact with different partner proteins in each cellular compartment. Therefore, GATA-2 multiprotein complexes that mediate gene regulation are also likely to differ in each cell pool. A comprehensive inventory of GATA-2 partner proteins and target genes in both the stem and progenitor compartments should shed light on this issue.

With respect to cell cycling, we showed that the PYlow Hstlow of GATA-2+/− GMPs had a pronounced attenuation in CFC-GM output and Gr-1+Mac-1+ output in the blood of transplant recipients. The functional impairment from the PYlow Hstlow GMP fraction of GATA-2+/− marrow was not, however, accompanied by overall changes in the cell-cycle profile or turnover of the GMP population. The mechanism for impaired functional output from GATA-2+/− PYlow Hstlow GMP appears to extend beyond the mere repression of key myeloid cytokine receptors such as SCF, IL-3, and IL-6. (N.P.R. and T.E., unpublished observations). Future investigations will be directed at ascertaining the basis for restrained progenitor output from GATA-2+/− PYlow Hstlow GMPs.

The Notch pathway modulates GATA-2 activity in a number of contexts, including the inhibition of myeloid differentiation in cell lines, the inhibition of myelopoiesis from embryonic stem cells, and the formation of intra-embryonic, definitive hematopoiesis.43-45 Our data uncover a novel action for GATA-2 on a Notch-1 target gene, HES-1, in the GMP compartment. These data imply that HES-1 is a target gene of GATA-2 in the GMP pool. The chromatin immunoprecipitation results suggest that GATA-2 regulation of the HES-1 gene is direct, but additional functional experiments are required to verify this. Interestingly, our data also raise the possibility that the regulatory circuit of Notch-1, GATA-2, and HES-1 is an important determinant of granulocyte-macrophage progenitor function. The precise nature of how HES-1 affects GMP functionality in the setting of GATA-2 deficiency was not investigated here, but altered self-renewal and cell cycling may be involved.31,42 Further work is needed to disentangle whether the effects of HES-1 in the setting of GATA-2 deficiency reflect a perturbation of one or both of these cell fate mechanisms.

Our data may have ramifications for the topical subject of lineage routing and commitment in hematopoiesis.7 We have shown that GATA-2 was less important for the functionality of the CMPs but not the GMPs. Why GATA-2+/− or GATA-2–llx CMPs are able to display normal progenitor function remains unclear, but emerging evidence suggesting that subsets of CMPs are able to transit through multiple, parallel intermediates during myelopoiesis may explain our findings.9,10 In addition, the CMPs may use another heretofore unidentified route, by-passing the GMPs intermediate to reach an end-stage GM-type progenitor. A similar scenario may be true for the GATA-2+/− LMPP compartment, which also displayed normal immunophenotypic abundance and functional output.

Although the dormancy of the stem cell compartment has long been appreciated, it was recently shown that specific progenitor cell compartments are also replete with quiescent cells.41 Although the restriction of cell cycling may be a crucial facet of progenitor cell control,35 its operational and molecular basis may differ from that observed in stem cells.35,41,46 Restriction of cell cycling within progenitors, for example, is likely to be relatively short-lived in comparison to stem cells; this may be a corollary of the shorter longevity of some mature blood cells or the higher responsiveness of progenitors to cytokine stimulation. These considerations notwithstanding, the excessive cell cycling of early lineage–committed progenitors may be restricted for at least 2 reasons. First, these early progenitors may defer cell-cycle entry until they are required for blood cell production. This, in turn, may prevent stem cells from superfluously producing early progenitors. Second, the quiescence of committed progenitors may be protective against the accumulation of mutations that have been shown to cause cancer in the committed progenitor compartment.17,19 Therefore, stringent modulation of proliferation occurs at multiple venues in the hematopoietic hierarchy to maintain the biologic integrity of the stem and progenitor cell compartments.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Anne Atzberger and Kevin Clark for assistance with cell sorting.

This work was supported by the European Science Foundation (N.P.R.), the Elimination of Leukemia Fund (N.P.R. and A.S.B.), the Medical Research Council (MRC) UK (N.P.R. and T.E.), the European Community: Marie Curie RTN Eurythron (C.F.), the Oxford Partnership Comprehensive Biomedical Research Center with funding from the Department of Health's National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Center funding scheme (P.V.), and the Leukemia Research Fund UK (T.E.).

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: N.P.R. designed and performed the research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; A.S.B. performed the research and analyzed data; C.F., G.E.M., and Y.G. performed research; A.J.T. contributed a reagent; and D.T.S., P.V., and T.E. supervised the research.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

A.S.B.'s current address is Sir William Dunn School of Pathology, University of Oxford, South Parks Road, Oxford, OX1 3RE United Kingdom.

Correspondence: Tariq Enver, MRC Hematology Unit, Weatherall Institute for Molecular Medicine, John Radcliffe Hospital, University of Oxford, Oxford, OX3 9DS, United Kingdom; e-mail: tenver@gwmail.jr2.ox.ac.uk.