The BCL6 transcriptional repressor is required for development of germinal center (GC) B cells and when expressed constitutively causes diffuse large B-cell lymphomas (DLBCLs). We examined genome-wide BCL6 promoter binding in GC B cells versus DLBCLs to better understand its function in these settings. BCL6 bound to both distinct and common sets of functionally related gene in normal GC cells versus DLBCL cells. Certain BCL6 target genes were preferentially repressed in GC B cells, but not DLBCL cells. Several such genes have prominent oncogenic functions, such as BCL2, MYC, BMI1, EIF4E, JUNB, and CCND1. BCL6 and BCL2 expression was negatively correlated in primary DLBCLs except in the presence of BCL2 translocations. The specific BCL6 inhibitor retro-inverso BCL6 peptidomimetic inhibitor-induced expression of BCL2 and other oncogenes, consistent with direct repression effects by BCL6. These data are consistent with a model whereby BCL6 can directly silence oncogenes in GC B cells and counterbalance its own tumorigenic potential. Finally, a BCL6 consensus sequence and binding sites for other physiologically relevant transcription factors were highly enriched among target genes and distributed in a pathway-dependent manner, suggesting that BCL6 forms specific regulatory circuits with other B-cell transcriptional factors.

Introduction

During the humoral response to T-cell antigens, activated B cells migrate to the interior of lymphoid follicles to form germinal centers (GCs) within which they acquire a phenotype uniquely suited to undergo and survive the process of clonal expansion and immunoglobulin affinity maturation.1 Centroblasts, a subset of GC B cells, replicate at extremely rapid rates while simultaneously undergoing somatic hypermutation caused by activation-induced cytosine deaminase. This cellular phenotype is labile and can rapidly change in response to different signals toward apoptosis, terminal differentiation, or additional rounds of proliferation.1 The acquisition of these properties is dependent on transcriptional programming imposed by master regulators of the GC phenotype, among which the BCL6 transcriptional repressor plays a central role. BCL6-null mice fail to form GCs,2,3 and BCL6 loss of function is lethal to primary GC B cells.4 BCL6 repression of a DNA damage sensing and checkpoint pathway, including the ATR, CHEK1, TP53, CDKN1A, and GADD45A genes,4,,,–8 explains at least in part how centroblasts manage to survive the combined pressures of rapid replication and accumulation of DNA damage that is associated with somatic hypermutation. BCL6 repression of the PRDM1, which is a master regulator of plasma cell differentiation, may lock B cells into the GC phenotype until BCL6 is down-regulated by signals that terminate affinity maturation.9,–11

Given their unusual tolerance of simultaneous proliferation and somatic hypermutation, it is perhaps not surprising that a majority of B-cell lymphomas arise from GC B cells, among which the diffuse large B-cell lymphomas (DLBCLs) are the most common subtype.1 Constitutive expression of BCL6 is often observed in DLBCLs, frequently in association with promoter translocations or point mutations.1 The physiologic significance of these lesions is underlined by the fact that mice engineered to express BCL6 constitutively within GC B cells are prone to development of DLBCL similar to the human disease.12,13 Moreover, the sustained expression of BCL6 is required to maintain the malignant phenotype of these cells because specific BCL6 inhibitor drugs have potent antilymphoma effects in vitro and in vivo.14,15 To better understand the biologic function of BCL6, a previous study performed chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP-on-chip) to identify BCL6 target genes in a Burkitt lymphoma cell line, resulting in the identification of 485 target genes. In addition to known BCL6-regulated pathways, such as DNA damage, these studies suggested additional functions for BCL6 in previously unrecognized functions, such as protein ubiquitylation and metabolism.16

It is important to note, however, that Burkitt lymphomas, DLBCLs, and normal GC B cells are biologic distinct entities and can be readily distinguished in transcriptional profiling studies.17 Although some functions of BCL6 appear to be conserved between normal and malignant B cells, such as attenuation of DNA damage sensing and checkpoints, normal and malignant B cells are unquestionably biologically distinct, and we hypothesized that BCL6 transcriptional programming would be altered in DLBCL. We therefore examined the functional and genomic features of BCL6 target genes in human primary centroblasts versus DLBCL cell lines. These data reveal many new functions for BCL6, including previously unknown antioncogene activities, differential target gene binding and repression between GC B cells and DLBCL cells, and the formation of coregulatory units with other transcription factors involving genes with specific biologic functions.

Methods

Mammalian cell culture

OCI-ly1 and OCI-ly7 cells were grown in medium containing 90% Iscove medium (Cellgro, Manassas, VA), 10% fetal bovine serum (Gemini, Irvine, CA), and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The Farage and Toledo cell lines were grown in RPMI with 10% fetal calf serum, penicillin G/streptomycin, glutamine, and N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid. For BCL6 inhibition experiments, cells were cultured in the presence of 15 μM retro-inverso BCL6 peptidomimetic inhibitor (RI-BPI) or the control peptides as reported14 for the indicated time points.

Isolation of GC cells

GC B cells were purified from normal fresh human tonsillectomy specimens by magnetic cell separation based on the expression of phenotypic markers, such as CD38, IgD, CD77, and CD71.18,–20 These human tissues were obtained with the approval of the Institutional Review Boards of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine and Weill Cornell Medical College in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. After Ficoll Histopaque gradient centrifugation was used to isolate tonsilar mononuclear cells followed by antibody-based microbead cell separation (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA). As shown in Figure S1 (available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article), the purity of the isolated cells is normally more than 90%.

ChIP-on-chip

ChIPs were performed as described15,16 with modifications. Briefly, GC B cells, OCI-Ly1, or OCI-Ly7 cells were double cross-linked with 2 mM ethylene glycol-bis (succinimidyl succinate) cross-linker and 1% formaldehyde. After sonication, immunoprecipitations were performed using 10 μg BCL6 (N3; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) or actin control antibody (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) from the chromatin fragments of 20 × 106 cells. After validation of enrichment by quantitative ChIP, BCL6, or actin ChIP products and their respective input genomic fragments were amplified by ligation-mediated polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The products were cohybridized with the respective input samples to NimbleGen promoter arrays (human genome, version 35, May 2004; NimbleGen Systems, Madison, WI). Three replicates were performed with each condition. The microarray data have been uploaded to GEO under accession number GSE15179.21

Quantitative ChIP

ChIPs were performed with 20 × 106 cells incubated with 5 μg BCL6 (N3; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or actin antibody (Sigma-Aldrich). DNA fragments enriched by ChIP were quantified by real-time PCR using the Fast SYBR green kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and an ABI 7900 HT real-time thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems). The HPRT and GAPDH genes, which are not BCL6 targets, were used as negative controls; 2−ΔCT values (antibody-input) were expressed as percentage of input or as fold enrichment (% input BCL6 antibody on test promoter/% input BCL6 antibody on control [GAPDH] promoter).22 Primers are listed in Table S1.

Quantitative PCR

RNA was prepared using Trizol extraction (Invitrogen). cDNA was prepared using high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems) and detected by fast SyberGreen (Applied Biosystems) on 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR System with 384-Well Block Module thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems). We normalized gene expression to GAPDH and expressed values relative to control using the ΔΔCT method. For quantitative PCR primers, see Table S2.

Data analysis algorithm for ChIP-on-chip, pathway analysis by pathway analysis of gene expression (PAGE), motif analysis by Finding Informative Regulatory Element (FIRE), and other computational analyses are given in Supplemental Methods.

Immunohistochemistry and FISH

Paraffinized tissue was obtained from the Department of Pathology, New York Presbyterian Hospital, and from the British Columbia Cancer Agency after necessary informed consent or exemption was obtained in accordance with the Helsinki protocols. The cases were fully anonymous, according to institutional and federal provisions. All lesions were classified in accordance with the 2008 WHO classification system. Tissue microarrays were generated using Beecher Instruments microarrayer (Silver Spring, MD), as previously published.5,23,24 Deparaffinized slides were antigen retrieved in 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, pH.8.0, and indirect immunohistochemistry was performed with antispecies-specific biotinylated secondary antibodies followed by avidin–horseradish peroxidase or avidin-AP, and developed by Vector Blue and/or DAB color substrates (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). After the first staining, slides were briefly boiled in 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid antigen retrieval solution, pH 8, and a second indirect immunohistochemistry stain was applied with non–cross-reacting reagent, and finally developed with a contrasting color. Single staining was performed using the Envision+ staining kit (Dako North America, Carpinteria, CA). The following antibodies were used: anti–bcl6 mouse monoclonal antibody from Dako North America (P6-B6p) 1:20; anti–Pax-5 goat polyclonal antibody from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (C-20) 1:50; anti-bcl2 mouse monoclonal antibody from DAKO (clone124) 1:500. Cases with more than 30% of stained cells for any of the antibodies tested were considered as positive cases and scored as described previously.5 DLBCL cases were analyzed for BCL2 translocation (t14,18) using fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) and routine karyotyping. FISH was performed after deparaffinization of 2-μm sections, using Vysis LSI dual-color BCL2 probe (Abbot Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL) following the manufacturer's instructions with minor modifications. Karyotypes were interpreted following International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature as described previously.25 We analyzed the results by 2-tailed Fisher exact tests. A P value less than .05 was considered significant.

Results

Identification of BCL6 target genes in primary centroblasts and DLBCL cells

To identify BCL6 target genes in normal and malignant B cells, ChIP-on-chip was performed on primary human GC B cells and the DLBCL cell lines OCI-Ly1 and OCI-Ly7 on high-density oligonucleotide promoter microarrays in duplicate. For each gene, a BCL6 binding profile was generated by calculating the log ratio between ChIP and input intensities for each probe. BCL6 binding peaks were then robustly identified using a random permutation analysis and 3-probe sliding window as previously reported.16 We selected a threshold at the 0.993 quantile as a cutoff to call peaks because the ratio of randomly expected “hits” to called “hits” is within a range where the false discovery rate remains less than 10% (Figure S2) and known BCL6 target genes (such as CCND2 and STAT3) are captured (Figure S3A). Using this approach, approximately 1700 genes per array were reproducibly enriched, of which approximately 60% of peaks overlapped among replicates. Out of concern that the nonoverlapping peaks might represent true positives that simply did not meet the high stringency threshold criteria resulting from technical variability, we developed a “peak rescue” algorithm to analyze the location, reproducibility, and relative contribution of individual probes to peaks that were not high enough to pass our threshold. This method calculates the correlation between replicate BCL6 binding profiles for each gene and requires this measure to be more than 0.8 (Figure S3B,C). When we applied this approach to the OCI-Ly1 ChIP-on-chip, the overlap between replicates increased from 63% to 91%. The peak rescue algorithm also yielded 91% overlap in OCI-Ly7 cells and 81% overlap in centroblasts (Table S3). These results were validated by quantitative ChIP in independent primary GC B-cell and cell-line samples (Figure S4).

BCL6 promoter binding varies between normal and malignant B cells

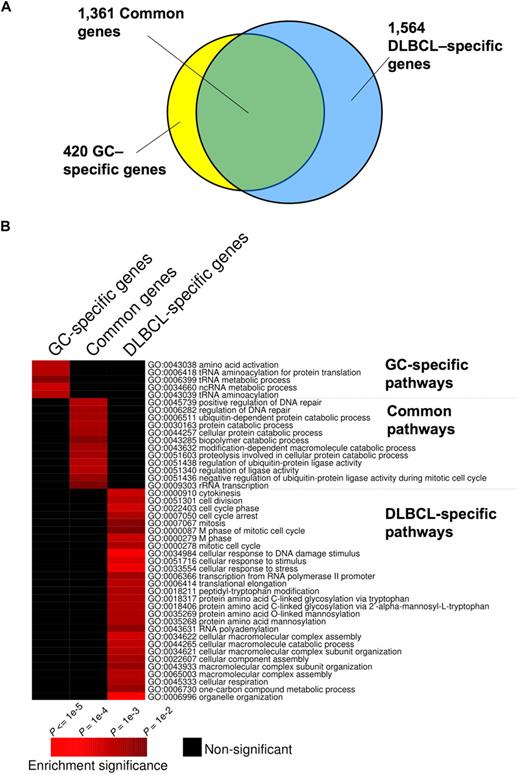

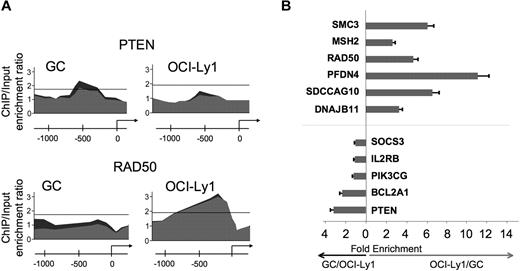

Although BCL6 functions in normal and malignant B cells have generally been considered to be similar,4,6 we found that 1564 genes were bound by BCL6 in DLBCL cells but not in GC B cells, suggesting a possible gain-of-function effect in lymphomas (Figure 1A; Table S4). In contrast, 420 genes were bound exclusively in GC B cells, suggesting that there is also simultaneous loss of BCL6 function in lymphomas (Figure 1A; Table S5). A total of 1361 genes were bound in both lymphomas and GC B cells (Figure 1A; Table S6). To determine whether differential binding associated with specific gene functions, we performed a PAGE analysis on the different overlapping and nonoverlapping gene sets. PAGE is a recently developed pathway analysis approach that uses mutual information to explain genomic variables, such as ChIP binding enrichment, in terms of known pathways, for example, from the Gene Ontology annotations. This analysis indicated that nonoverlapping BCL6 targets in normal and malignant B cells were enriched in functionally distinct sets of genes (Figure 1B; Tables 1 and S4Table S5. Genes preferentially bound in GC B cells (XLS, 83 KB)–S6). Biologic functions more represented in DLBCL than normal GC B cells, including genes involved in the mitotic phase of the cell cycle, response to DNA damage, cellular respiration, and translational elongation. Examples of genes preferentially bound in DLBCLs included RAD50, SMC3, MSH2, and HDAC2 (Figure 1B; Tables 1, S4). Pathways and processes more associated with primary GC B cells than with DLBCLs were largely related to tRNA and translational control. However, a closer look at targets differentially bound in GC cells yielded a number of genes of interest, including the BCL2 homolog BCL2A1, PIM2, SOCS3, and PIK3CG and the tumor suppressor PTEN (Figure 1B; Tables 1 and S5). Using a publicly available expression array dataset,26 we determined that at least BCL2A1 and PIM2 are significantly up-regulated in primary DLBCLs compared with centroblast and centrocytes (1-tailed Wilcoxon test, P = .004 and P = .003, respectively). These data were confirmed by independent quantitative ChIP experiments (Figure 2), and underline that BCL6 transcriptional programming is different in normal GC B cells versus DLBCL cells. Finally, among the shared pathways were known biologic activities of BCL6, such as regulation of DNA repair, as well as previously uncharacterized functions, such as ubiquitin-based protein degradation and rRNA transcription (Figure 1B; Tables 1, S6).

Distinct and overlapping BCL6 target genes in DLBCL and GC B cells. (A) The Venn diagram illustrates the numbers of target genes specific to GC B cells, DLBCL cells, and the number of the common target genes between these cell types. (B) The heatmap represents the combination of GO term enrichment identified by PAGE in GC-specific, DLBCL-specific, and common target genes. Red indicates the intensity of enrichment of GO terms (rows) among these groups of target genes (columns). The statistical significance of the heatmap color code is provided.

Distinct and overlapping BCL6 target genes in DLBCL and GC B cells. (A) The Venn diagram illustrates the numbers of target genes specific to GC B cells, DLBCL cells, and the number of the common target genes between these cell types. (B) The heatmap represents the combination of GO term enrichment identified by PAGE in GC-specific, DLBCL-specific, and common target genes. Red indicates the intensity of enrichment of GO terms (rows) among these groups of target genes (columns). The statistical significance of the heatmap color code is provided.

Differential BCL6 binding to specific promoters in DLBCL and GC B cells. (A) An example of BCL6-binding peaks for genes that were identified as differentially bound in GC versus DLBCL cells. The y-axis indicates enrichment versus input. The x-axis indicates the location of probes within the respective loci relative to the transcriptional start site. The dark gray and light gray tracings correspond to the different replicates. (B) A subset of genes predicted to be differentially bound by ChIP-on-chip were validated by independent quantitative ChIP experiments. The x-axis measures the fold enrichment ratio of promoters in GC cells versus OCI-Ly1 (black arrow) or OCI-Ly1 versus GC cells (red arrow). The data are from 3 independent experiments. Error bars represent the SEM for triplicates.

Differential BCL6 binding to specific promoters in DLBCL and GC B cells. (A) An example of BCL6-binding peaks for genes that were identified as differentially bound in GC versus DLBCL cells. The y-axis indicates enrichment versus input. The x-axis indicates the location of probes within the respective loci relative to the transcriptional start site. The dark gray and light gray tracings correspond to the different replicates. (B) A subset of genes predicted to be differentially bound by ChIP-on-chip were validated by independent quantitative ChIP experiments. The x-axis measures the fold enrichment ratio of promoters in GC cells versus OCI-Ly1 (black arrow) or OCI-Ly1 versus GC cells (red arrow). The data are from 3 independent experiments. Error bars represent the SEM for triplicates.

BCL6 target genes are differentially expressed in GC B cells versus DLBCL cells

To determine the functional impact of BCL6 binding, we compared the transcript abundance of its centroblast target genes in naive B cells (BCL6-negative pre-GC B cells) versus centroblasts using expression microarray data from a recent B-cell gene expression profiling analysis.26 Among the 909 BCL6 target genes represented in this dataset, 19.8% (ie, 180 genes) were significantly repressed in primary human centroblasts (Table S7; Figure S5). This was significantly more than expected by chance (P < 10−9, 2-tailed χ2 test), given that only 12.4% of the 7676 non-BCL6 targets were similarly repressed in that dataset. When the transcript abundance of these 180 genes was examined in primary DLBCL cases (Table S7; Figure S5), only approximately 50% of them were still silenced, suggesting that BCL6 transcriptional programming is disrupted in DLBCL cases. Among BCL6 target genes that were up-regulated in DLBCLs versus centroblasts were BCL2, MYC, JUNB, FAIM3, HSP90AB, and IRF4, which are critical mediators of survival, growth, proliferation, and B-cell differentiation. Of note, many of these genes (Table S3) were still bound by BCL6 in DLBCL cells, suggesting that loss of silencing is not necessarily the result of failure of BCL6 to associate with these loci.

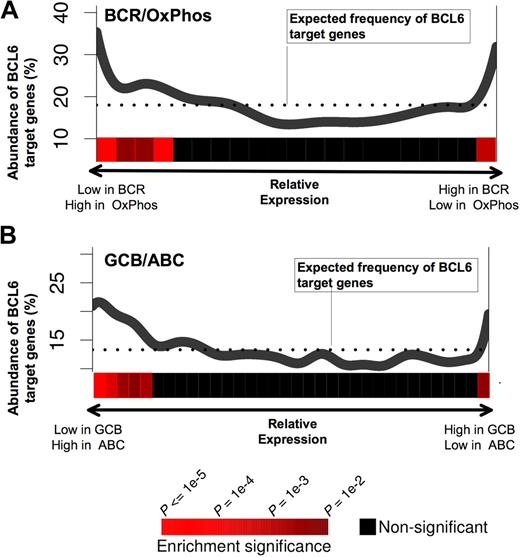

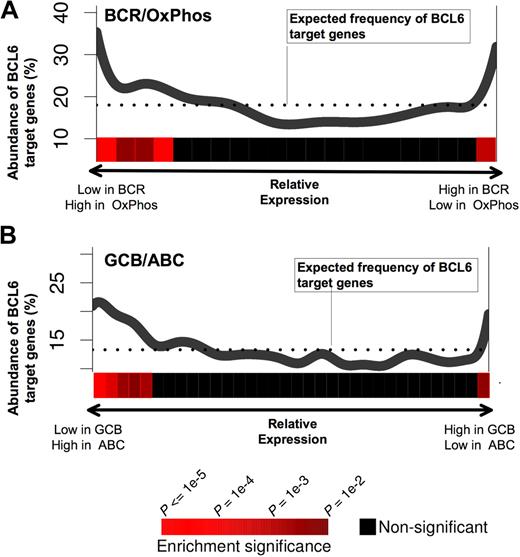

BCL6 target genes are preferentially repressed in BCR-type DLBCL cells

A recent study has identified naturally occurring DLBCL expression profiles associated with B-cell receptor and proliferation-related genes (BCR-DLBCL) or with genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation (OxPhos DLBCL).27 Using the same dataset of DLBCL expression profiles27 and the PAGE program, we found that BCL6 target gene expression levels were nonrandomly distributed with respect to BCR versus OxPhos gene signatures (P < .0001; Figure 3A). In particular, BCL6 target genes were preferentially repressed in BCR-type DLBCLs compared with OxPhos (Figure 3A). This result supports the notion that the BCR-type DLBCLs are biologically dependent on BCL6, consistent with the fact that BCR DLBCL cells are more readily killed with BCL6 inhibitor drugs.14,16 We note, however, that a small but significantly larger than expected fraction of BCL6 targets have higher expression in BCR-DLBCLs compared with OxPhos. This may have obscured previous analyses that did not detect any linear correlation between BCL6 targets and BCR versus OxPhos expression (Our previous study was able only to detect coordinated regulation of BCL6 targets in BCR DLBCLs.16 ) DLBCLs have also been classified into prognostically significant cell of origin distinctions, including activated B cell–like (ABC) and GC B cell–like (GCB) subtypes,28 based on the similarities of their expression profiles to the respective primary B cells. Using the same analysis as described above for OxPhos versus BCR, BCL6 target genes were significantly associated with lower expression in GCB compared with ABC, consistent with the presumed GC origin of GCB DLBCLs (Figure 3B).

BCL6 target genes are preferentially repressed in BCR and GCB-type DLBCLs. The figure shows a graphical representation depicting the abundance of BCL6 targets among genes that are either repressed or up-regulated in (A) BCR versus OxPhos and (B) GCB versus ABC DLBCLs. Each panel contains a plot in which the x-axis represents all of the genes contained in our promoter arrays distributed according to whether they are repressed preferentially in BCR (A left) or OxPhos (A right), or in GCB (B left) or ABC (B right). The y-axis represents the percentage of these genes that were found to be BCL6 targets by ChIP-on-chip. The dotted line represents the percentage of genes that would be expected to be BCL6 targets if the BCL6 targets were uniformly distributed across the range of relative expression values. The statistical significance of the enrichment for BCL6 target genes is indicated by the heatmap that is below each of the plots, as shown in the heatmap color code at the bottom of the figure.

BCL6 target genes are preferentially repressed in BCR and GCB-type DLBCLs. The figure shows a graphical representation depicting the abundance of BCL6 targets among genes that are either repressed or up-regulated in (A) BCR versus OxPhos and (B) GCB versus ABC DLBCLs. Each panel contains a plot in which the x-axis represents all of the genes contained in our promoter arrays distributed according to whether they are repressed preferentially in BCR (A left) or OxPhos (A right), or in GCB (B left) or ABC (B right). The y-axis represents the percentage of these genes that were found to be BCL6 targets by ChIP-on-chip. The dotted line represents the percentage of genes that would be expected to be BCL6 targets if the BCL6 targets were uniformly distributed across the range of relative expression values. The statistical significance of the enrichment for BCL6 target genes is indicated by the heatmap that is below each of the plots, as shown in the heatmap color code at the bottom of the figure.

BCL6 represses critical lymphoma oncogenes in primary GC B cells

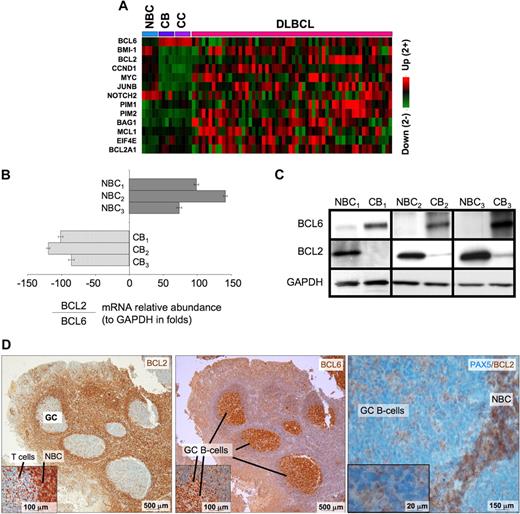

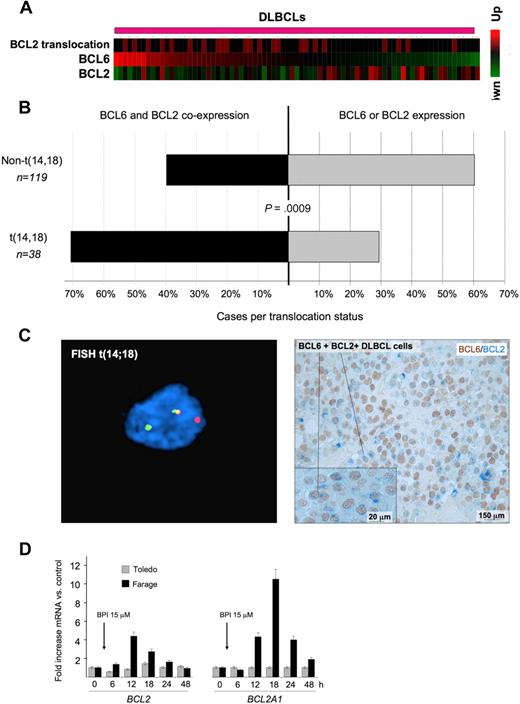

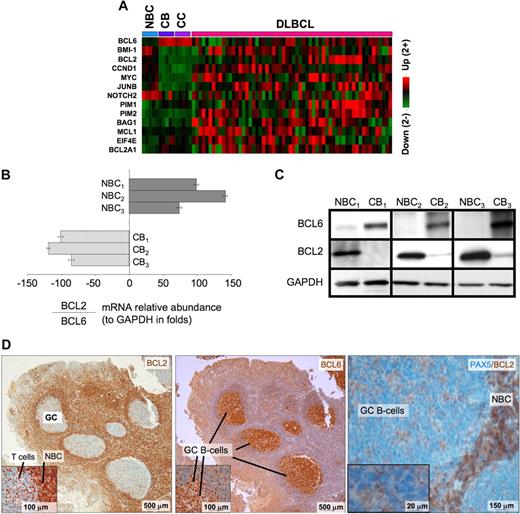

BCL6 repression of tumor suppressor genes is thought to facilitate proliferation and survival in primary centroblasts. However, our data also show that BCL6 also binds to several prominent oncogenes, including several with confirmed roles in lymphomagenesis such as BCL2, MYC, BMI1, and CCND1, as well as other oncogenic proteins, such as JUNB, EIF4E, and PIM1. These genes were preferentially repressed in centroblasts versus naive B cells (Figure 4A), suggesting that they are physiologically relevant BCL6 targets. Consistent repression of these genes was lost in DLBCLs, suggesting that the antioncogene function of BCL6 may be disrupted during malignant transformation. BCL2 and MYC are of particular interest because they are not expressed in normal centroblasts and are frequently translocated or aberrantly expressed in lymphomas. Binding to BCL2 was confirmed by quantitative ChIP (Figure S6). Consistent with previous reports,29,,–32 the mRNA and protein levels of BCL6 and BCL2 were inversely correlated in primary human tonsilar B cells as shown by quantitative PCR, Western blot, and immunohistochemistry (Figure 4B-D). Using a publicly available DLBCL expression microarray dataset,33 we observed that BCL2 and BCL6 mRNA levels were inversely correlated in primary DLBCLs (−0.24, P < .004; Figure 5A). BCL6 can thus repress multiple oncogenes and may have tumor suppressor functions in primary GC B cells that could counterbalance its own pro-oncogenic activities.

BCL6 represses many oncogenes in centroblasts. (A) A heatmap is shown representing the transcript abundance (data from Basso26 ) of oncogenes and related genes that are direct transcriptional targets of BCL6 (NBC indicates naive B cells; CB, centroblasts; and CC, centrocytes). (B) The relative ratio of BCL2 to BCL6 mRNA abundance versus GAPDH was measured in 3 independent sets of human tonsilar NBC and CBs by quantitative PCR (error bars represent the SEM for triplicates), and (C) Western blots. (D) Human tonsil sections were submitted to immunohistochemistry with BCL2 and nuclear counterstain (right panel and inset), BCL6 antibody and counterstain (middle), and with PAX5 and BCL2 costaining. The data show inverse staining patterns of BCL6 and BCL2 in GCs and show that the PAX5-positive GC B cells lack BCL2, indicating the BCL2-positive GC cells are not of the B-cell lineage. Slides were viewed with a light microscope (AxioSkop2; Carl Zeiss Microimaging, Thornwood, NY) using Plan-Neofluar lens at a 10×/0.50 air objective, 40×/0.90 oil objective, 100×/1.30 oil objective. Images were taken using a color camera (AxioCam; Carl Zeiss Microimaging) and were processed using Axiovision software (Carl Zeiss Microimaging).

BCL6 represses many oncogenes in centroblasts. (A) A heatmap is shown representing the transcript abundance (data from Basso26 ) of oncogenes and related genes that are direct transcriptional targets of BCL6 (NBC indicates naive B cells; CB, centroblasts; and CC, centrocytes). (B) The relative ratio of BCL2 to BCL6 mRNA abundance versus GAPDH was measured in 3 independent sets of human tonsilar NBC and CBs by quantitative PCR (error bars represent the SEM for triplicates), and (C) Western blots. (D) Human tonsil sections were submitted to immunohistochemistry with BCL2 and nuclear counterstain (right panel and inset), BCL6 antibody and counterstain (middle), and with PAX5 and BCL2 costaining. The data show inverse staining patterns of BCL6 and BCL2 in GCs and show that the PAX5-positive GC B cells lack BCL2, indicating the BCL2-positive GC cells are not of the B-cell lineage. Slides were viewed with a light microscope (AxioSkop2; Carl Zeiss Microimaging, Thornwood, NY) using Plan-Neofluar lens at a 10×/0.50 air objective, 40×/0.90 oil objective, 100×/1.30 oil objective. Images were taken using a color camera (AxioCam; Carl Zeiss Microimaging) and were processed using Axiovision software (Carl Zeiss Microimaging).

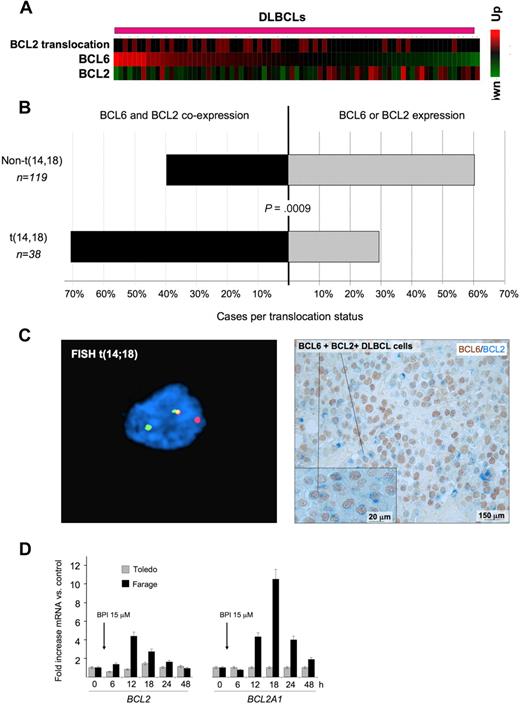

BCL6 and BCL2 inverse correlation is disrupted in patients with BCL2 translocations. (A) A series of DLBCLs (columns) is plotted in a heatmap and distributed according to their abundance of BCL6 transcript (data from Lenz et al33 ). BCL2 mRNA is generally negatively correlated with BCL6. Cases with BCL2 translocations are indicated by the red boxes in the top row. (B) Expression of BCL2 and BCL6 was examined in a series of 157 DLBCL patients by immunohistochemistry. The top bar represents patients without BCL2 translocation; bottom bar, BCL2 translocated cases. In each case, the black bar represents the percentage of patients who express both BCL6 and BCL2, whereas the gray bar represents the percentage of tumors that express either BCL2 or BCL6 exclusively. (C) Immunohistochemistry shows that DLBCL cases with t(14;18) translocations (left panel) typically exhibit malignant cells with dual BCL2 (blue) and BCL6 (brown) protein expression (right panel). FISH results were visualized using a Zeiss LSM510 Multiphoton confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss Microimaging) equipped with 40×/0.75/0.72 and 60×/0.80/0.3 objectives and one 25-mW argon laser exciting at 458, 488, and 514 nm and one 1-mW helium-neon laser exciting at 543 nm; proprietary image acquisition software was used for image analysis. (D) The DLBCL cell lines Farage (which expresses BCL6 and has wild-type BCL2 locus) and Toledo (which is BCL6-negative) were exposed for the indicated times to the specific BCL6 peptidomimetic inhibitor RI-BPI. The y-axis represents the fold increase of mRNA change induced by RI-BPI versus a control peptide. Cells were treated as indicated, and the data were from 3 independent experiments. Error bars represent the SEM for triplicates.

BCL6 and BCL2 inverse correlation is disrupted in patients with BCL2 translocations. (A) A series of DLBCLs (columns) is plotted in a heatmap and distributed according to their abundance of BCL6 transcript (data from Lenz et al33 ). BCL2 mRNA is generally negatively correlated with BCL6. Cases with BCL2 translocations are indicated by the red boxes in the top row. (B) Expression of BCL2 and BCL6 was examined in a series of 157 DLBCL patients by immunohistochemistry. The top bar represents patients without BCL2 translocation; bottom bar, BCL2 translocated cases. In each case, the black bar represents the percentage of patients who express both BCL6 and BCL2, whereas the gray bar represents the percentage of tumors that express either BCL2 or BCL6 exclusively. (C) Immunohistochemistry shows that DLBCL cases with t(14;18) translocations (left panel) typically exhibit malignant cells with dual BCL2 (blue) and BCL6 (brown) protein expression (right panel). FISH results were visualized using a Zeiss LSM510 Multiphoton confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss Microimaging) equipped with 40×/0.75/0.72 and 60×/0.80/0.3 objectives and one 25-mW argon laser exciting at 458, 488, and 514 nm and one 1-mW helium-neon laser exciting at 543 nm; proprietary image acquisition software was used for image analysis. (D) The DLBCL cell lines Farage (which expresses BCL6 and has wild-type BCL2 locus) and Toledo (which is BCL6-negative) were exposed for the indicated times to the specific BCL6 peptidomimetic inhibitor RI-BPI. The y-axis represents the fold increase of mRNA change induced by RI-BPI versus a control peptide. Cells were treated as indicated, and the data were from 3 independent experiments. Error bars represent the SEM for triplicates.

Deregulated expression of BCL6 target oncogenes, such as BCL2, through translocations or other mechanisms might bypass the tumor suppressor effects of BCL6. Indeed, when we removed DLBCL samples with t(14;18) BCL2 translocation from the Lenz et al dataset33 and reestimated the correlation between BCL2 and BCL6 mRNA levels, the inverse correlation between BCL6 and BCL2 expression was even more significant (−0.44, P < .0006). In addition, we observed that BCL2 translocations tended to be associated with higher BCL6 mRNA levels (Wilcoxon rank-sum test, P < .03, Figure 5A), consistent this genomic rearrangement being used to overcome BCL6-mediated repression. An examination of BCL6 and BCL2 expression by immunohistochemistry in tissue microarrays containing 157 DLBCL cases showed a similar relationship between the 2 oncogenes. BCL2 translocations were more frequently observed in DLBCL samples with higher BCL6 staining intensity (P < .025, 1-tailed χ2 test). A total of 71% of DLBCLs with t(14;18) coexpressed any amount of BCL6 and BCL2, whereas only 39.5% of cases lacking BCL2 translocation expressed both proteins (P = .0009, 2-tailed Fisher exact test; Figure 5B). DLBCL cases with t(14;18) translocations typically exhibited malignant cells with dual BCL2 and BCL6 protein expression (Figure 5C). Finally, administration of the specific BCL6 inhibitor RI-BPI14 to DLBCL cells lacking the t(14;18) translocation induced de-repression of both BCL2 and BCL2A1, whereas expression of these 2 genes was not affected by RI-BPI in a BCL6-negative DLBCL cell line (Figure 5D). RI-BPI also induced expression of MYC, IRF4, PIM2, EIF4E, MCL1, BMI-1 and JUNB, confirming that these target genes are directly regulated by BCL6 (Figure S9; and data not shown). RI-BPI did not further induce the expression of CCND1, PIM1, BAG1, or NOTCH2 (data not shown), suggesting that either BCL6 is not able to repress these genes in DLBCL cells or that these oncogene promoters are not dependent for their repression on the BCL6 BTB domain region that is blocked by RI-BPI.

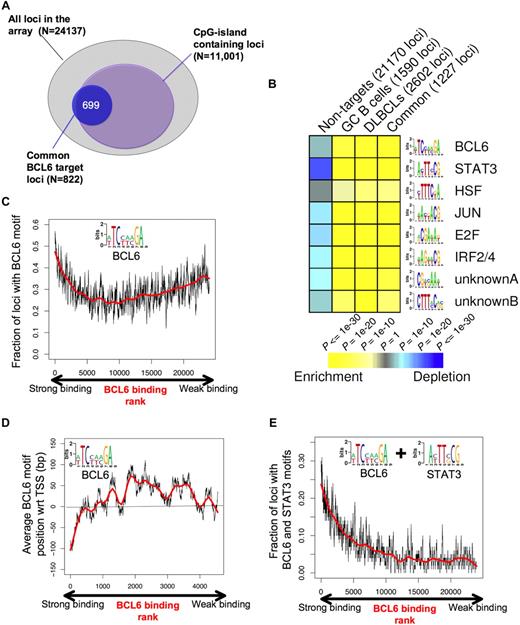

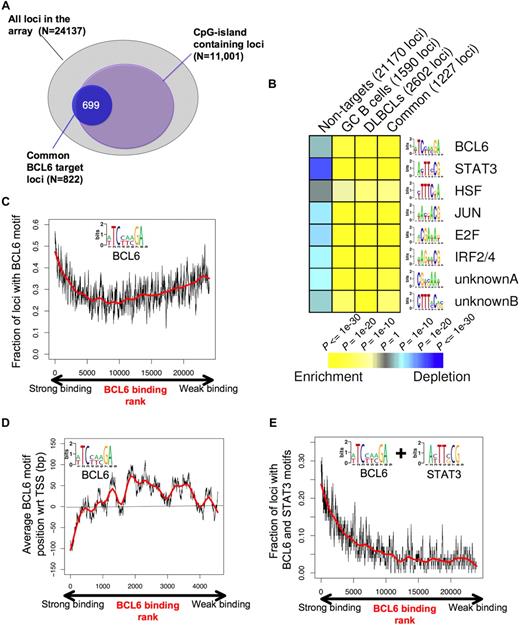

BCL6 target genes contain known cis-regulatory sequences but also putative novel genomic elements

To better understand the genomic context for BCL6-mediated transcriptional repression, we investigated the association between BCL6-targeted promoters and CpG islands. A total of 11 001 of the 24 137 promoters (ie, 45.6%) on the microarray used for this study contain CpG islands. Surprisingly, BCL6 binding was not randomly distributed among these genes because approximately 80% of its target genes contained CpG islands (P < 10−256; Figure 6A). We then used the FIRE motif-finding algorithm to identify genomic elements that might explain how BCL6 binds and regulates its target genes.34 Because FIRE is a de novo motif discovery program, it is not restricted to known/published DNA binding sites. Rather, FIRE performs a comprehensive motif space exploration to discover motifs that can best explain gene expression or transcription factor binding. Remarkably, the BCL6 DNA binding sequence was among the most highly enriched elements within the promoters of BCL6 target genes (P < 10−26) versus the non-BCL6 target promoters (Figure 6B). The BCL6 DNA binding sequence captured by FIRE, (A/T)TC(C/T)(A/T)(A/C)GA, is significantly more degenerate than the published BCL6 consensus. We speculate that this motif is more representative of a physiologic BCL6 consensus binding element as opposed to DNA sequences enriched for in vitro screening assays.35 BCL6 was observed to preferentially localize to this element in tiling ChIP-on-chip experiments (Figure S10). Other DNA elements that were highly overrepresented among BCL6 target genes versus controls were highly similar to the known STAT3 (P < 10−53), HSF1 (P < 10−11), V-JUN (P < 10−32), E2F (P < 10−39), IRF4 (P < 10−35) binding sites, and 2 novel elements CTTT(A/C)C(A/G)(C/G) (P < 10−15) and CG(A/T)(C/G)AA(A/T) (P < 10−21; Figure 6B; Table 2). Significant enrichment for these elements was observed in the GC, DLBCL, and common (overlap between DLBCL and GC) lists of BCL6 targets (Figure 6B; Table 2). The intensity of BCL6 promoter binding was directly correlated with the presence of BCL6 binding elements at these genes (R = 0.766) among the first 5000 genes ranked according to ChIP-on-chip signal intensity, although this correlation was lower when considering the entire cohort of genes (Figure 6C). This suggests that promoters to which BCL6 can bind to DNA directly are better captured by ChIP assay than those in which BCL6 is recruited indirectly through other proteins.7,36 In the context of the promoter arrays used for this study, BCL6 binding was most strongly associated with the presence of BCL6 consensus sequence (vs a scrambled control element, data not shown), when these were located upstream of the annotated transcriptional start site (Figure 6D), although it remains possible that strong binding at other sites might be identified in future studies that use more comprehensive genomic coverage. An even stronger positive correlation was identified between BCL6 binding intensity and the presence of BCL6 plus STAT3 elements (R = 0.797; Figure 6E). Although BCL6 and STAT3 motifs often occurred closer to each other on DNA than expected if they were randomly distributed in the promoters, we did not find that the 2 elements overlap (data not shown).

BCL6 target genes display specific genomic features and DNA elements. (A) The diagram depicts the overlap between the overlapping BCL6 genes between normal and malignant B cells (blue circle) and CpG island-containing loci among the entire pool of 24 137 promoters contained on the array. (B) Analysis of the BCL6 target gene cohort by FIRE identified 8 DNA elements significantly overrepresented among BCL6 target genes identified in GC cells (CB), DLBCL cells, the common target genes, or in the cohort of non-BCL6 targets (columns). Yellow represents highly enriched; and blue, relative depletion. The statistical significance of the heatmap color code is provided. (C) The graph represents the distribution of genes ordered according to the strength of BCL6 binding in ChIP-on-chip on the x-axis and the frequency with which genes contain the BCL6 consensus site identified by FIRE (inset), using a sliding window of 100 genes. (D) Genes are distributed along the x-axis according to BCL6 binding, and the y-axis depicts the position of the FIRE-identified BCL6 motif occurrences relative to the transcriptional start site (set at 0). Negative numbers are upstream and positive numbers downstream of the start site. Similar to panel C, the y-axis corresponds to the average position of BCL6 motif occurrences with respect to the transcription start site using a sliding window of 100 genes. Only genes containing at least one occurrence of the BCL6 motif were considered. (E) Similar to panel C, the graph represents BCL6 binding on the x-axis, but the y-axis shows the frequency at which genes contain both BCL6 and STAT3-binding elements.

BCL6 target genes display specific genomic features and DNA elements. (A) The diagram depicts the overlap between the overlapping BCL6 genes between normal and malignant B cells (blue circle) and CpG island-containing loci among the entire pool of 24 137 promoters contained on the array. (B) Analysis of the BCL6 target gene cohort by FIRE identified 8 DNA elements significantly overrepresented among BCL6 target genes identified in GC cells (CB), DLBCL cells, the common target genes, or in the cohort of non-BCL6 targets (columns). Yellow represents highly enriched; and blue, relative depletion. The statistical significance of the heatmap color code is provided. (C) The graph represents the distribution of genes ordered according to the strength of BCL6 binding in ChIP-on-chip on the x-axis and the frequency with which genes contain the BCL6 consensus site identified by FIRE (inset), using a sliding window of 100 genes. (D) Genes are distributed along the x-axis according to BCL6 binding, and the y-axis depicts the position of the FIRE-identified BCL6 motif occurrences relative to the transcriptional start site (set at 0). Negative numbers are upstream and positive numbers downstream of the start site. Similar to panel C, the y-axis corresponds to the average position of BCL6 motif occurrences with respect to the transcription start site using a sliding window of 100 genes. Only genes containing at least one occurrence of the BCL6 motif were considered. (E) Similar to panel C, the graph represents BCL6 binding on the x-axis, but the y-axis shows the frequency at which genes contain both BCL6 and STAT3-binding elements.

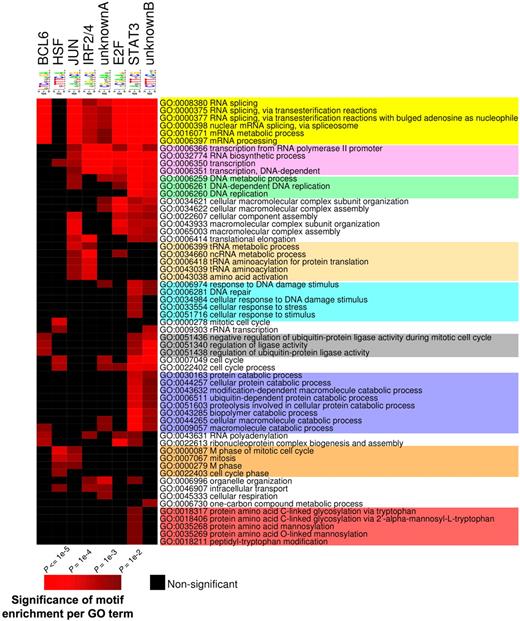

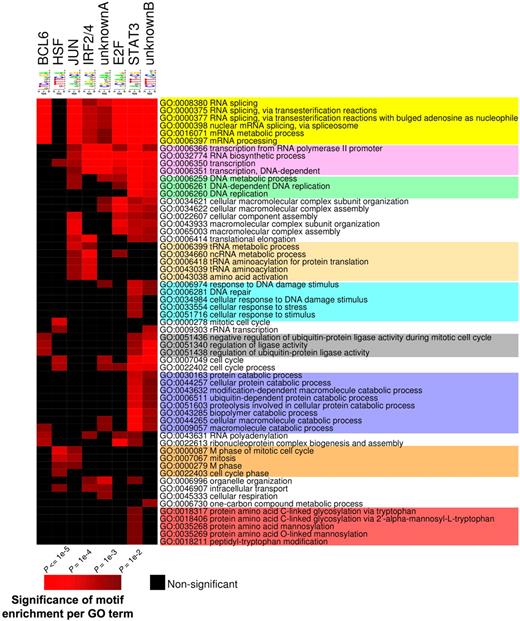

BCL6 codistributes to specific pathways in association with particular DNA binding elements

The presence of a specific set of DNA binding elements at BCL6 target genes is consistent with a model whereby these factors might be important coregulators with BCL6, as has indeed been shown for STATs and IRF4.3,37,–39 We wondered whether these elements are distributed randomly throughout BCL6 targets or conversely associate with specific functionally related cohorts of genes. Therefore, we segregated BCL6 target genes according to the presence of these motifs and performed PAGE, restricting the analysis to the pathways that were significantly associated with BCL6 targets (see Figure 7). The results indicate that different combinations of genomic motifs associated with specific cohorts of BCL6 targets. For example, BCL6 motif was significantly associated with RNA splicing and protein ubiquitylation (Figure 7; Table S8). On the other hand, BCL6 targets involved in cell cycle regulation were more frequently associated with heat shock factor (HSF). Several other functions were preferentially associated with given motifs. Altogether, these data suggest that these different cohorts of BCL6 targets may be regulated through distinct combinations of transcription factors and that BCL6 may be recruited to some of these genes through an indirect mechanism.

Consensus motif identification by FIRE distribute to different GO terms. PAGE was performed to identify GO terms (rows) associated with BCL6 target genes according to the presence of the several DNA elements identified by FIRE (columns). Brighter red color is indicative of enrichment of the respective motifs for the indicated GO terms. The differently colored shading of the GO terms is provided to highlight those that are preferentially associated with different subsets of binding motifs. The statistical significance of the heatmap color code is provided.

Consensus motif identification by FIRE distribute to different GO terms. PAGE was performed to identify GO terms (rows) associated with BCL6 target genes according to the presence of the several DNA elements identified by FIRE (columns). Brighter red color is indicative of enrichment of the respective motifs for the indicated GO terms. The differently colored shading of the GO terms is provided to highlight those that are preferentially associated with different subsets of binding motifs. The statistical significance of the heatmap color code is provided.

Discussion

As a master regulator of GC formation, BCL6 plays a critical role in the humoral immune response. Its ability to facilitate rapid proliferation, survival, attenuated sensing and response to DNA damage, and blockade of terminal differentiation is unusual because most cells do not tolerate such conditions. Indeed, ectopic expression of BCL6 in naive B cells or fibroblasts induces p53 responses and senescence.40 Lymphoma cells are biologically different from primary B cells. Whether disruption of BCL6 functions contributes to these differences between normal and malignant B cells is unknown. To better understand the mechanism of action of BCL6 in health and disease, we identified promoters to which BCL6 binds in normal GC B cells and DLBCL cell lines. BCL6 binds to the promoters of approximately 3000 genes, representing more than 10% of the genes on the microarrays used for these assays. This number of target genes is consistent or even slightly less in number than those identified for other transcription factors, such as MYC, HES, NOTCH1, and several of the E2F isoforms.41,42 These data do not rule out that BCL6 could bind to additional genes through enhancer or intronic elements. For example, BCL6 binds to PRDM1 principally through a site within intron 3 that also serves as the promoter for PRDM1β (short isoform).24 However, our previous work with tiling arrays covering the entire genomic loci of BCL6 target genes4,8,43 (and unpublished data) show that binding occurs generally within promoter regions, so we think that we have generated a reasonably complete representation of BCL6 target genes.

Overall these data indicate that BCL6 regulates a biologically coherent set of pathways. Genes involved in DNA repair, cell cycle, chromatin formation, and regulation, protein stability and transcriptional regulation stand out as being heavily represented in both normal and malignant B cells. Biochemical and biologic exploration of these pathways is warranted to understand the role of these genes in setting up the GC and DLBCL phenotypes. Given the rapidity of the cell cycle in these highly proliferative cells, it is perhaps not surprising that regulatory pathways governing certain aspects of protein and RNA turnover, as well as chromatin structure would need to be highly regulated.

Of particular note was the gain of many target genes in DLBCLs, implying an expansion of the BCL6 regulon that implies a previously unknown gain of function for BCL6 in lymphoma cells. There was also a reciprocal loss of binding to targets that are bound by BCL6 in normal B cells, implying that there is also a partial loss of function of BCL6. The mechanism that leads to differential binding is not known and requires further investigation. It is possible, for example, that the chromatin status of certain genes could impair or facilitate BCL6 binding to different genes in normal and malignant B cells. Alternatively, BCL6 may be recruited indirectly to some of these genes as has been shown previously, for example, in the case of the target gene CDKN1A, to which BCL6 is recruited via the MIZ1 transcription factor.7 Altered expression patterns or functions of factors that could recruit BCL6 to certain genes or stabilize its binding to DNA could also contribute to differential binding. Along these lines, we find that the nonoverlapping BCL6 target genes in GC B cells (P = .52) and DLBCLs (P < 10−5) are relatively depleted in BCL6 DNA consensus elements (data not shown) in contrast to the genes these cells have in common (P < 10−26).

Our data show that BCL6 can bind and repress several oncogenes, including the mitochondrial pathway antiapoptotic genes BCL2, MCL1, and BCL2A1. These data suggest that BCL6 can cause GC B cells to become poised for apoptosis and rapidly undergo cell death if they fail to produce a high affinity antibody or if they accumulate genetic damage during the course of somatic hypermutation. In primary centroblasts, BCL6 represses several prominent B-cell oncogenes in addition to BCL2, including MYC, BMI1, JUNB, CCND1 PIM1, PIM2, EIF4E, BAG1, and NOTCH2. Collectively, these data are indicative of a model whereby BCL6 can counterbalance its own powerful oncogenic actions by suppressing expression of other oncogenes, that if expressed might cause cells to move inexorably toward malignant transformation. BCL6 was shown to down-regulate antiapoptotic proteins, including BCL2 when ectopically expressed in CV1 cells.44 The preferential association of BCL2 translocation with BCL6 expression has been noticed previously,45 and our data provide a mechanism for this observation. Along these lines, deregulated expression of either MYC or BCL2 occurs in approximately 5% and 20% of DLBCL, respectively, in part because of translocation to the immunoglobulin heavy chain locus. The combined overexpression of BCL6 with BCL2 and/or MYC would overturn the carefully balanced activity of BCL6 and provide a powerful stimulus toward lymphomagenesis and potentially more aggressive tumors (so-called double-hit or dual-translocation lymphomas, as suggested, eg, by Kawasaki et al46 ). Further underlining the balance between anti- and pro-oncogenic activities mediated by BCL6, we also show that additional tumor suppressors, such as CDKN1B and PTEN, are also targeted by BCL6.

Another important regulatory circuit revealed by these data is the direct repression by BCL6 of the IRF4 transcription factor. IRF4 is silenced in centroblasts but is induced in cells exiting the GC reaction via CD40 signaling to nuclear factor-κB. IRF4 can directly repress BCL6, leading to terminal differentiation of B cells.39 By keeping IRF4 silenced, BCL6 can maintain the GC phenotype until it becomes overwhelmed by powerful and sustained termination signals emanating from follicular dendritic cells in the GC light zone. IRF4 appears to play an important oncogenic role in multiple myeloma47 and is thus one more example of an oncogene that is suppressed by BCL6. BCL6 repressed several additional modulators of nuclear factor-κB signaling, including TNFAIP3, as well as components of the transforming growth factor-β and tumor necrosis factor signaling pathways.

Our data show that BCL6 target genes are enriched in DNA-binding elements for several transcription factors in addition to BCL6, including STATs, IRFs, HSF, E2F, and JUN, as well as 2 motifs for which binding proteins remain unknown. Previous data show that BCL6 transcriptional programming can be counterregulatory with STAT6, STAT3, and IRF4, and we can now expand these data to a more genomic scale.3,37,48,49 Along these lines, we found that BCL6-STAT3 element-containing target genes tended to be repressed in the GCB-type DLBCL patients compared with the ABC-type DLBCLs (data not shown). Because STAT3 was previously shown to be a BCL6 target48 and was also captured by our ChIP-on-chip assays, these data are again suggestive of a counterregulatory network, whereby BCL6 repression of the STAT3 program is released in cells exiting the GC reaction through cytokine signaling pathways. The intersection of BCL6 with E2F, JUN, and HSF remains to be explored but suggests potential novel coregulatory circuits. Of particular interest is the fact that these elements may segregate with BCL6 to genes involved in specific biologic functions. These data expand on the emerging evidence for biochemical compartmentalization of the BCL6 transcriptional program into functional units. Specifically, it was previously shown that BCL6 uses different corepressors to repress genes involved in different biologic pathways: SMRT, N-CoR, and BCoR corepressors mediate repression of genes in the ATR-CHEK1-TP53-CDKN1A pathway,4,5,8 the MTA3 corepressor is required for BCL6 repression of PRDM1,24,50 and the CtBP corepressor is required for BCL6-negative autoregulation.43 Taken together, the variation in BCL6 repression complex formation and association with different sets of coregulator or counterregulator transcription factors are indicative of the complexity of BCL6 transcriptional programming.

BCL6 is a bona fide therapeutic target in DLBCL that is required for the maintenance of DLBCL cell survival. DLBCLs can be effectively killed in vitro and in vivo using the specific BCL6 inhibitor RI-BPI.14 The rational combination of BCL6 inhibitors with drugs that target downstream pathways, such as p53, can provide additional antilymphoma efficacy.5 The transcriptional programming data described in this study provide a further basis for rational development of combinatorial antilymphoma therapy, for example, by combining BCL6 and BCL2 inhibitor drugs.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Louis Staudt for information pertaining to the t(14;18) status of DLBCL cases in his DLBCL expression dataset, Dr Giorgio Cattoretti for constructing some of the tissue microarrays used in this study, and Drs K. H. Ramesh and Reiner Siebert for performing BCL2 FISH studies.

A.M. is supported by National Cancer Institute (Bethesda, MD; R01 CA104348), the Chemotherapy Foundation (New York, NY), the Sam Waxman Cancer Research Foundation (New York, NY), and the G&P Foundation (New York, NY) and is a Leukemia & Lymphoma Society (White Plains, NY) Scholar. R.D.G. and D.E.H. are supported by the National Cancer Institute of Canada, Terry Fox program (Chilliwack, BC; project grant 016003).

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: W.C. performed the experiments shown in Figures 1 to 6, helped design the experiments, and wrote the first draft; J.M.P. helped design and analyze the chip-on-chip experiments; L.C. and R.S. helped design and perform the experiments shown in Figures 4 and 5; L.W. and S.N.Y. helped to perform the cell- line and tonsil experiments; K.Y. helped develop tool-to-analysis ChIP-on-chip data; P.F. developed tissue microarrays and performed and analyzed immunohistochemistry experiments; R.D.G. developed tissue microarrays, performed and analyzed immunohistochemistry experiments, and edited the manuscript; D.E.H. performed cytogenetic analysis; O.E. provided key intellectual contributions and performed computational biology and statistical analysis, and edited the manuscript; and A.M. designed experiments, interpreted the results, and edited and wrote the final manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Olivier Elemento, Institute for Computational Biomedicine, Weill Cornell Medical College, 1300 York Ave, New York, NY 10065; e-mail: ole2001@med.cornell.edu; or Ari Melnick, Division of Hematology/Oncology, Department of Medicine, Weill Cornell Medical College, 1300 York Ave, New York, NY 10065; e-mail: amm2014@med.cornell.edu.