Abstract

The shear stress–induced transcription factor Krüppel-like factor 2 (KLF2) confers antiinflammatory properties to endothelial cells through the inhibition of activator protein 1, presumably by interfering with mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascades. To gain insight into the regulation of these cascades by KLF2, we used antibody arrays in combination with time-course mRNA microarray analysis. No gross changes in MAPKs were detected; rather, phosphorylation of actin cytoskeleton-associated proteins, including focal adhesion kinase, was markedly repressed by KLF2. Furthermore, we demonstrate that KLF2-mediated inhibition of Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK) and its downstream targets ATF2/c-Jun is dependent on the cytoskeleton. Specifically, KLF2 directs the formation of typical short basal actin filaments, termed shear fibers by us, which are distinct from thrombin- or tumor necrosis factor-α–induced stress fibers. KLF2 is shown to be essential for shear stress–induced cell alignment, concomitant shear fiber assembly, and inhibition of JNK signaling. These findings link the specific effects of shear-induced KLF2 on endothelial morphology to the suppression of JNK MAPK signaling in vascular homeostasis via novel actin shear fibers.

Introduction

Endothelial cells (ECs) in the arterial tree are chronically exposed to pulsatile blood flow and shear stress. At sites where shear stress is severely reduced or oscillatory, ECs show signs of dysfunction, which is generally regarded as the first event in the development of atherosclerosis.1,2 Shear stress exposure causes endothelial actin cytoskeleton rearrangement both in vivo and in vitro.3,4 The resulting so-called actin stress fibers are assembled in the direction of the flow, and the cells also elongate in the same direction.

The antiinflammatory and antiatherosclerotic effects of prolonged shear stress on ECs have been attributed to an inhibition of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling.5 MAPK signaling consists of 4 distinct linear signaling routes, which comprise the extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2), ERK5, Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK), and p38 pathways, although interconnections between these routes generate a complex network. Shear stress was shown to inhibit tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α)–mediated MAPK signaling through the JNK pathway.6 Cellular structures involved in endothelial MAPK signal propagation include the actin cytoskeleton and focal adhesions (FAs).7,8

In recent years, it has been established that the transcription factor Krüppel-like factor 2 (KLF2), which is induced specifically by shear stress, acts as a central transcriptional regulator that establishes functional quiescent differentiation in endothelium (Table 1).9–29 Most of these studies were performed by the use of a functional genomics approach and therefore not designed to directly identify KLF2-mediated changes at the level of protein activity. Nonetheless, KLF2 was found to inhibit posttranscriptional activation of c-Jun and activating transcription factor 2 (ATF2), both members of the activator protein 1 (AP-1) complex.30 AP-1 is activated through phosphorylation by the MAPKs ERK1/2, JNK, and p38.31

To elucidate how KLF2 regulates the complex MAPK network, we analyzed the phosphorylated proteome (kinome) in the absence and presence of exogenously expressed human KLF2 in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs). We demonstrate that the anti-inflammatory effects of KLF2 arise only after full establishment of the KLF2-mediated changes in actin cytoskeleton. The KLF2-elicited short thick basal actin fibers are shown to be essential for inhibition of the JNK targets ATF2 and c-Jun. Furthermore, KLF2 is attested to be essential for formation of these distinct Rho-dependent, Rho kinase–independent shear fibers and associated shear stress–mediated cell alignment and JNK inhibition.

Methods

Cell culture, tissue isolation, shear stress experiments, and reagents

HUVECs, human microvascular endothelial cells (HMVECs), and human aorta endothelial cells (HAECs) were isolated and cultured as previously described.9,32 Confluent monolayers were cultured from freshly isolated ECs on fibronectin-coated tissue culture plastic or on fibronectin-coated glass microscopy cover slides and used before the fourth passage. Shear stress experiments were performed as described,10 with the following modifications: parallel plate flow chambers (μ-Slide I 0.4 Luer; Ibidi) coated with human fibronectin were used at a calibrated shear stress level of 19 plus or minus 7 dyn/cm2 instead of an artificial capillary system, and shear stress stimulation was performed for 4 days. Thrombin, cytochalasin D, and Y27623 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. TNF-α was from R&D Systems and phalloidin-TRITC from Invitrogen. The isolation of rat renal and femoral arteries and saphenous veins has been described previously.33 This investigation conforms to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication No. 85-23). The ethics committee for animal experiments at the VU University Medical Center approved the procedures.

Lentiviral overexpression, Western blotting, microscopy, and real-time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction

Long-term lentiviral overexpression, microscopy, and Western blotting were performed as previously described.33,34 The RhoA antibody was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology and the P-JNK, P-c-Jun, P-ATF2, and phosphorylated myosin light chain 2 (P-MLC) antibodies were from Cell Signaling Technology. The antibody against human vinculin was from Sigma-Aldrich, and the KLF2 antibody was described previously.34 Real-time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was performed as described.10

Kinex protein array and microarray analysis

For protein array analysis, HUVECs from 2 independent isolates were lysed 7 days after lentiviral transduction following the manufacturer's protocol (Kinexus). These lysates were shipped and analyzed in duplicate by the manufacturer (Kinexus). Results were analyzed by the use of a moderated t test to correct for multiple testing.35 Microarray analysis was performed as described.10 In brief, 3 independent HUVECs isolates were transduced with KLF2 lentivirus or empty control virus. Cells were lysed at 24, 48, and 72 hours after transduction, and RNA was isolated. For each time point and isolate, KLF2-transduced and control RNA were hybridized in duplo (dye-swap). The microarray data discussed in this publication have been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) and are accessible through GEO Series accession number GSE19412 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE19412).

RhoA activity assay

Confluent monolayers of HUVECs were lysed in 50mM Tris-HCl containing 1% NP-40 and protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Active GTP-bound RhoA was isolated by the use of glutathione S-transferase–tagged Rhotekin (Millipore) and glutathione-agarose beads (Sigma-Aldrich). RhoA levels were analyzed by Western blot.

Cell morphology analysis

Differential interference contrast photomicrographs were analyzed by the use of Adobe Photoshop CS3 software. The length and width of approximately 100 HUVECs per condition were measured and the angle of the elongated cells (length/width > 2) was used to calculate the cell angle compared with the flow direction.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed with the use of unpaired Student t tests, when comparing 2 situations, or 1-way analyses of variance with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Probability values less than .05 were considered significant. Protein array data were analyzed by the use of a moderated t test specifically designed for array analysis.35 Microarray data were analyzed as described.10 Error bars depict standard error of the mean.

Results

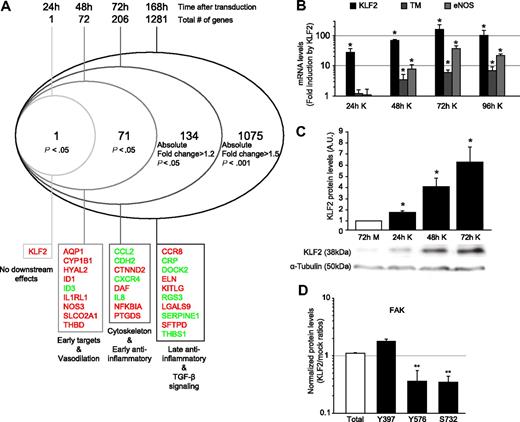

Time-course analysis shows gradual buildup of KLF2 and anti-inflammatory effects

KLF2 confers a quiescent phenotype to ECs by inducing various transcriptional changes through multiple pathways, including the inhibition of the AP-1 pathway, through inhibition of phosphorylation and nuclear localization of c-Jun and ATF2.12,30 Interestingly, inhibition of ATF2 by KLF2 was found to occur only marginally after 24 hours of shear stress, whereas complete abrogation of ATF2 activity was observed only after long-term shear stress exposure (5 days), indicating a delayed response.30 Therefore, we analyzed the transcriptional effects of KLF2 in time after lentiviral transduction by using genome-wide microarray mRNA profiling (Figure 1A; supplemental Table 1, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Methods link at the top of the online article).

Time-course analysis after lentiviral KLF2 overexpression. (A) HUVECs were transduced with mock (M) or KLF2 (K) lentivirus. After 24, 48, or 72 hours or 7 days, RNA was isolated, and microarray expression profiling was performed. A modified Venn analysis of the microarray expression data at 24, 48, 72, and 168 hours after lentiviral KLF2 transduction is displayed. Indicated are the numbers of genes per time point that meet the indicated criteria but do not meet the criteria for an earlier time point. Inflammatory genes, transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) signaling genes and vasodilatation genes were previously published to be KLF2 dependent. HUVECs were transduced with mock or KLF2 lentivirus for 24, 48, and 72 hours, and levels of the indicated genes were measured by the use of real-time RT-PCR (n = 5; B) or Western blot and densitometric quantification (n = 3; C). α-Tubulin was used as a loading control. (D) Summary of levels of the different posttranslationally activated forms of FAK in KLF2-transduced compared with mock-transduced cells, as analyzed with the Kinex antibody microarray. The category axis shows antibody specificity for the indicated phosphorylated amino acid residue. Fold induction by KLF2 is indicated on the y-axis. *P < .05, **P < .01.

Time-course analysis after lentiviral KLF2 overexpression. (A) HUVECs were transduced with mock (M) or KLF2 (K) lentivirus. After 24, 48, or 72 hours or 7 days, RNA was isolated, and microarray expression profiling was performed. A modified Venn analysis of the microarray expression data at 24, 48, 72, and 168 hours after lentiviral KLF2 transduction is displayed. Indicated are the numbers of genes per time point that meet the indicated criteria but do not meet the criteria for an earlier time point. Inflammatory genes, transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) signaling genes and vasodilatation genes were previously published to be KLF2 dependent. HUVECs were transduced with mock or KLF2 lentivirus for 24, 48, and 72 hours, and levels of the indicated genes were measured by the use of real-time RT-PCR (n = 5; B) or Western blot and densitometric quantification (n = 3; C). α-Tubulin was used as a loading control. (D) Summary of levels of the different posttranslationally activated forms of FAK in KLF2-transduced compared with mock-transduced cells, as analyzed with the Kinex antibody microarray. The category axis shows antibody specificity for the indicated phosphorylated amino acid residue. Fold induction by KLF2 is indicated on the y-axis. *P < .05, **P < .01.

Venn analysis of KLF2-induced genes during different stages of KLF2 overexpression indeed demonstrated that of the 1281 genes that are regulated by prolonged KLF2 overexpression (7 days [168 hours]), only 16% (206 genes) was significantly regulated at 72 hours after KLF2 transduction. Of the 206 genes that were significantly regulated at 72 hours of KLF2 overexpression, only 72 genes (35%) are affected at 48 hours. At 24 hours after KLF2 transduction, only the transcript of KLF2 itself is induced. The earliest transcriptional targets of KLF2 comprise the known direct targets endothelial nitric oxide synthase (NOS3, eNOS) and thrombomodulin (THBD, TM), but also some of the most significant10,12,30 KLF2 downstream genes like aquaporin 1, cytochrome P450 1B1, hyaluronidase 2, and the prostaglandin transporter SLCO2A1. We validated the expression of the 2 best-characterized direct transcriptional targets of KLF2 (eNOS and TM)10,36 by real-time RT-PCR (Figure 1B). The optimal induction of these direct target genes tightly follows the slow accumulation of KLF2 protein levels after lentiviral overexpression (Figure 1C). In contrast, the genes that constitute the previously reported antiinflammatory effects of KLF212,30 are affected only after prolonged KLF2 overexpression, indicating an indirect regulation. Most of these genes are known to be induced through MAPK signaling via AP-1, and therefore we next investigated this cascade.

KLF2 regulates the phosphorylation and activity of F-actin cytoskeleton-associated proteins

Because MAPK signaling occurs through posttranslational phosphorylation, a global insight into the KLF2-mediated effects on the endothelial phospho-proteome (kinome) is needed to understand how accumulated KLF2 inhibits MAPK signaling to AP-1.12 Therefore, we analyzed total protein lysates of mock- and KLF2-transduced HUVECs 7 days after transduction by use of the Kinex protein kinase antibody array, simultaneously probing changes in expression and phosphorylation state of more than 600 proteins (Table 2). Interestingly, only a limited number (16 of 623 induced, 18 of 623 repressed) of (phospho)-proteins was significantly changed by KLF2. As positive control of the validity of the Kinex array, inhibition of phosphorylation of c-Jun by KLF2, shown previously by our group,12 could readily be confirmed by this array-based technique (Table 2). The 4 canonical MAPKs, as well as the MAP2Ks MEK1 to 7 and MAP3Ks MEKK1, 2, and 4, were not significantly regulated by KLF2 (supplemental Table 2), with the sole exception of the mild induction of total p38a (Table 2). The most prominent KLF2-mediated effect on the endothelial kinome, however, is the inhibition of several phosphorylation sites of FA kinase (FAK), whereas total FAK protein level did not change (Table 2; Figure 1D). FAK is known to be involved in actin cytoskeleton regulation, as are other proteins regulated by KLF2, such as crystallin αB and heat-shock protein 27.

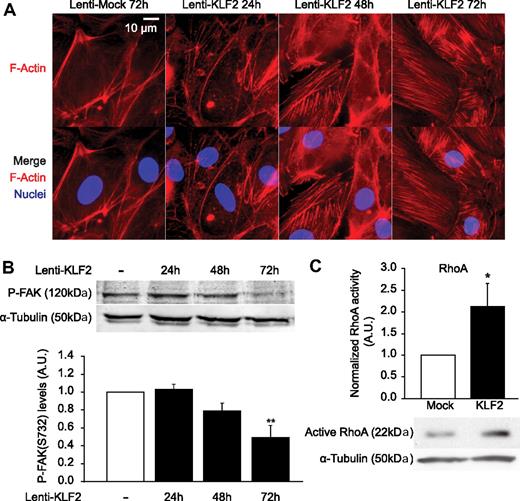

Next, we investigated the effects of KLF2 on the actin cytoskeleton to study the overall impact of the modulated activity of these actin-regulating proteins. At 24, 48, and 72 hours after KLF2 or mock transduction, HUVECs were fixed, and filamentous actin was visualized with phalloidin (Figure 2A). This result confirmed previous reports that KLF2 indeed affects the endothelial cytoskeleton after prolonged expression10 but establishes that this event is an early one after KLF2 overexpression because the first cytoskeletal changes already occur 48 hours after transduction, at the same time when direct targets TM and eNOS are being expressed. These effects of KLF2 on the actin cytoskeleton correlate to the inhibition of phosphorylation of FAK on serine residue 732 (Figure 2B), which is also prominent from 48 hours after transduction onwards. One of the best-characterized proteins involved in the regulation of F-actin filaments is the small GTPase RhoA.37 Therefore, we analyzed the activity of RhoA in HUVECs after prolonged KLF2 overexpression (Figure 2C) and indeed KLF2 robustly induces RhoA activity approximately 2.2-fold.

KLF2 induces early cytoskeleton changes, inhibits FAK S732 phosphorylation, and activates RhoA. (A) HUVECs were cultured on glass coated with fibronectin and fixed after 24, 48, or 72 hours of lentiviral overexpression. Nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 (blue) and actin filaments with Phalloidin-TRITC (red), and fluorescent microscopy was performed. (B) Western blot analysis of levels of FAK phosphorylated on serine residue 732 in mock- (□) and KLF2-transduced HUVECs (■) at 24, 48, and 72 hours after transduction. α-Tubulin was used as a loading control. (Bottom) Densitometric quantification of the Western blot (n = 4). (C) Active RhoA was isolated with glutathione S-transferase–tagged Rhotekin, and a representative subsequent Western blot for RhoA is shown. Three independent experiments were quantified and corrected for α-tubulin. *P < .05, **P < .01.

KLF2 induces early cytoskeleton changes, inhibits FAK S732 phosphorylation, and activates RhoA. (A) HUVECs were cultured on glass coated with fibronectin and fixed after 24, 48, or 72 hours of lentiviral overexpression. Nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 (blue) and actin filaments with Phalloidin-TRITC (red), and fluorescent microscopy was performed. (B) Western blot analysis of levels of FAK phosphorylated on serine residue 732 in mock- (□) and KLF2-transduced HUVECs (■) at 24, 48, and 72 hours after transduction. α-Tubulin was used as a loading control. (Bottom) Densitometric quantification of the Western blot (n = 4). (C) Active RhoA was isolated with glutathione S-transferase–tagged Rhotekin, and a representative subsequent Western blot for RhoA is shown. Three independent experiments were quantified and corrected for α-tubulin. *P < .05, **P < .01.

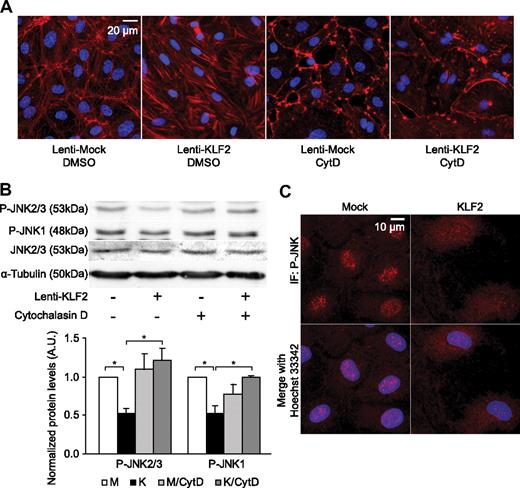

KLF2 inhibits JNK and downstream targets c-Jun and ATF2 in an actin cytoskeleton-dependent manner

In ECs, FAK and actin filaments have been implicated in the phosphorylation of JNK, the upstream kinase activating both AP-1 components c-Jun and ATF2.38,39 Activation of JNK via FAK requires only a small (∼ 140 amino acids) domain of FAK, including serine residue 732, phosphorylation of which is enhanced by atheroprone flow profiles,40 but which we found to be inhibited by KLF2 (Figure 2B). To assess the role of the actin cytoskeleton in the KLF2-mediated inhibition of JNK activity, the actin cytoskeleton in mock- and KLF2-transduced HUVECs was disrupted with cytochalasin D, which specifically binds actin dimers with very high affinity, thereby inhibiting actin polymerization.41 Cytochalasin D treatment disrupted typical short thick actin fibers in KLF2-transduced ECs, whereas some cortical actin filaments were still visible, as assessed by fluorescence microscopy (Figure 3A). Western blot analysis demonstrated that phosphorylation of JNK1 and JNK2/3 is indeed inhibited by KLF2 in unstimulated cells (Figure 3B, left 2 lanes). Further immunofluorescence analysis revealed that KLF2 overexpression also diminishes the amount of nuclear-localized phosphorylated JNK beyond inhibiting the total cellular levels of P-JNK (Figure 3C). Strikingly, the mere disruption of the actin cytoskeleton completely blocked the basal inhibitory effect of KLF2 on phosphorylation of all JNK isoforms (Figure 3B).

KLF2 inhibits phosphorylation and nuclear localization of JNK in an actin-dependent manner. (A) Fluorescent photomicrographs of mock- and KLF2-transduced cells treated with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or 200nmol/L Cytochalasin D (CytD) for 16 hours, demonstrating filamentous actin in red and nuclei in blue. (B) Western blot analysis of P-JNK1, 2, and 3 levels in mock- (□) and KLF2-transduced HUVECs (■) cultured in the presence of dimethyl sulfoxide (control) or cytochalasin D (200nmol/L) for 16 hours. α-Tubulin was used as a loading control. Quantifications are shown for 4 independent experiments. (C) Immunofluorescent photomicrographs of mock- and KLF2-transduced HUVECs, with phosphorylated JNK (P-JNK) shown in red and nuclei in blue. *P < .05.

KLF2 inhibits phosphorylation and nuclear localization of JNK in an actin-dependent manner. (A) Fluorescent photomicrographs of mock- and KLF2-transduced cells treated with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or 200nmol/L Cytochalasin D (CytD) for 16 hours, demonstrating filamentous actin in red and nuclei in blue. (B) Western blot analysis of P-JNK1, 2, and 3 levels in mock- (□) and KLF2-transduced HUVECs (■) cultured in the presence of dimethyl sulfoxide (control) or cytochalasin D (200nmol/L) for 16 hours. α-Tubulin was used as a loading control. Quantifications are shown for 4 independent experiments. (C) Immunofluorescent photomicrographs of mock- and KLF2-transduced HUVECs, with phosphorylated JNK (P-JNK) shown in red and nuclei in blue. *P < .05.

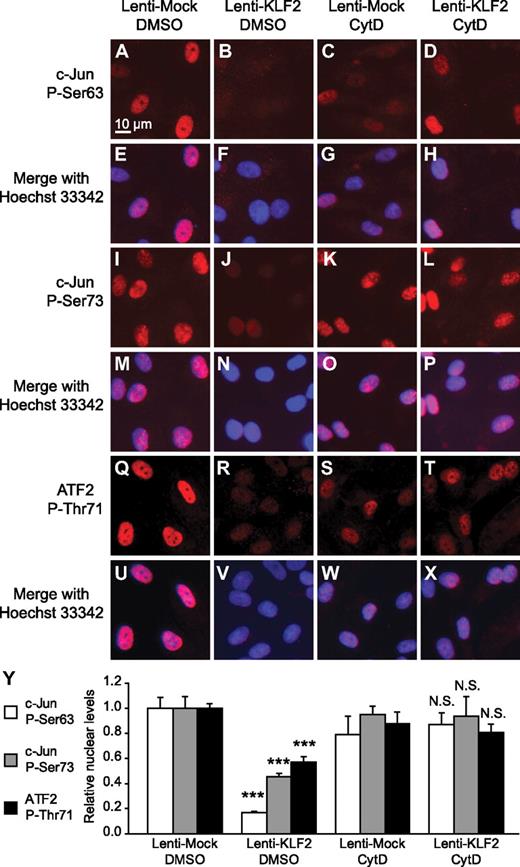

We next tested whether the KLF2-mediated actin cytoskeleton–dependent inhibition of JNK phosphorylation results in a functional inhibition of the JNK downstream targets c-Jun and ATF2 in the absence of inflammatory stimuli or shear stress. To that end, mock- and KLF2-transduced HUVEC were treated with cytochalasin D, and we performed immunofluorescence analysis of phosphorylated c-Jun and phosphorylated ATF2 and quantified the relative nuclear intensities. By using antibodies against 2 different phosphorylated forms of c-Jun (P-Ser63 and P-Ser73) and 1 antibody against phosphorylated ATF2 (P-Thr71), we showed that disruption of the actin cytoskeleton can reverse the basal inhibitory effect of KLF2 on nuclear localization of both of these JNK-activated transcription factors (Figure 4).

KLF2 inhibits nuclear localization of P-c-Jun and P-ATF2 in an actin-dependent manner. Immunofluorescent photomicrographs and quantification thereof of mock- (A, E, I, M, Q, U, C, G, K, O, S, and W) and KLF2-transduced (B, F, J, N, R, V, D, H, L, P, T, and X) HUVECs treated with DMSO (A-B, E-F, I-J, M-N, Q-R, U-V) or cytochalasin D (200nM; C-D, G-H, K-L, O-P, S-T, W-X) for 16 hours. Phosphorylated c-Jun on serine residue 63 (A-H) or serine residue 73 (I-P) or phosphorylated ATF2 on threonine residue 71 (Q-X) are stained red and nuclei are stained blue with Hoechst 33 342 (E-H, M-P, and U-X). (Y) Average nuclear intensity was measured for the indicated fluorescent staining and condition (n = 5). For each staining, 1-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons was performed, comparing KLF2/DMSO vs Mock/DMSO and KLF2/CytD vs Mock/CytD. ***P < .001. N.S. indicates not significant (P > .05).

KLF2 inhibits nuclear localization of P-c-Jun and P-ATF2 in an actin-dependent manner. Immunofluorescent photomicrographs and quantification thereof of mock- (A, E, I, M, Q, U, C, G, K, O, S, and W) and KLF2-transduced (B, F, J, N, R, V, D, H, L, P, T, and X) HUVECs treated with DMSO (A-B, E-F, I-J, M-N, Q-R, U-V) or cytochalasin D (200nM; C-D, G-H, K-L, O-P, S-T, W-X) for 16 hours. Phosphorylated c-Jun on serine residue 63 (A-H) or serine residue 73 (I-P) or phosphorylated ATF2 on threonine residue 71 (Q-X) are stained red and nuclei are stained blue with Hoechst 33 342 (E-H, M-P, and U-X). (Y) Average nuclear intensity was measured for the indicated fluorescent staining and condition (n = 5). For each staining, 1-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons was performed, comparing KLF2/DMSO vs Mock/DMSO and KLF2/CytD vs Mock/CytD. ***P < .001. N.S. indicates not significant (P > .05).

KLF2-induced actin fibers are distinct from stress fibers

In statically cultured HUVECs, actin filaments are normally located in a cortical ring (Figure 5A left), with an occasional stress fiber on the apical side of the cell (arrowhead, bottom left). These stress fibers are formed after integrin activation through interaction with the fibronectin matrix and are transient in nature.42 In contrast, actin filaments rearrange to form relatively short actin fibers that run along the basal membrane of the cell from FA to FA (Figure 5A) after KLF2 overexpression in the absence of flow. To better understand the nature of these actin fibers, we subjected HUVECs to TNF-α or thrombin, which are known to cause actin stress fiber formation in ECs (Figure 5B top left).43 Immunofluorescence analysis confirmed that the stress fibers formed by TNF-α or thrombin mostly span from one side of the cell to another and run along the apical membrane. Notably, thrombin stimulation causes actin filament-mediated cell contraction, resulting in gap formation between the cells, a process we did not observe in KLF2-overexpressing cells. Because KLF2 induces RhoA activity (Figure 2C) and Rho is known to induce actin stress fiber formation through Rho kinase,44 we tested whether KLF2-mediated shear fiber formation is dependent on Rho kinase (Figure 5B). Interestingly, Rho kinase inhibition at the maximal effective concentration to block thrombin-induced stress fiber formation (10μM Y27632)45 had no visible effect on the KLF2-induced actin shear fiber formation.

KLF2 induces distinct actin filament formation in a Rho-kinase–independent manner. (A) Mock-transduced (left) and KLF2-transduced (right) HUVECs were fixed, and immunofluorescence microscopy was performed. Visualized in blue are nuclei (stained with Hoechst 33342), in red F-actin (phalloidin-tetramethyl rhodamine iso-thiocyanate [TRITC]), and in green focal adhesions (vinculin stained with Alexa647). The top images were taken at high-power magnification focused on the basal side of the cell, whereas the middle images were taken at approximately 4 μm higher magnification. The bottom images were also taken with focus on the basal side of the cell. Arrowheads indicate typical actin fibers for the given condition. (B) Mock- or KLF2-transduced HUVECs were stimulated for 24 hours with TNF-α (10 ng/mL, top left), Thrombin (1 U/mL, middle left), Y27632 (10μM, top right), or left unstimulated (bottom). Then, cells were fixed, and immunofluorescence microscopy was performed. Visualized in green are focal adhesions (vinculin), in red actin filaments (phalloidin-TRITC), and in blue nuclei (stained with Hoechst 33342; top 4 images) or P-MLC (bottom 2 images). (C) Mock- (left) and KLF2-transduced (right) HMVECs and HAECs were fixed, and immunofluorescence microscopy was performed. Visualized in blue are nuclei (stained with Hoechst 33342), in red F-actin (phalloidin-TRITC), and in green focal adhesions (vinculin stained with Alexa647).

KLF2 induces distinct actin filament formation in a Rho-kinase–independent manner. (A) Mock-transduced (left) and KLF2-transduced (right) HUVECs were fixed, and immunofluorescence microscopy was performed. Visualized in blue are nuclei (stained with Hoechst 33342), in red F-actin (phalloidin-tetramethyl rhodamine iso-thiocyanate [TRITC]), and in green focal adhesions (vinculin stained with Alexa647). The top images were taken at high-power magnification focused on the basal side of the cell, whereas the middle images were taken at approximately 4 μm higher magnification. The bottom images were also taken with focus on the basal side of the cell. Arrowheads indicate typical actin fibers for the given condition. (B) Mock- or KLF2-transduced HUVECs were stimulated for 24 hours with TNF-α (10 ng/mL, top left), Thrombin (1 U/mL, middle left), Y27632 (10μM, top right), or left unstimulated (bottom). Then, cells were fixed, and immunofluorescence microscopy was performed. Visualized in green are focal adhesions (vinculin), in red actin filaments (phalloidin-TRITC), and in blue nuclei (stained with Hoechst 33342; top 4 images) or P-MLC (bottom 2 images). (C) Mock- (left) and KLF2-transduced (right) HMVECs and HAECs were fixed, and immunofluorescence microscopy was performed. Visualized in blue are nuclei (stained with Hoechst 33342), in red F-actin (phalloidin-TRITC), and in green focal adhesions (vinculin stained with Alexa647).

To identify whether the KLF2-induced actin fibers are in principle capable of generating force, we analyzed whether P-MLC is present on the actin fibers in control and KLF2-transduced cells (Figure 5B bottom). Indeed, P-MLC colocalizes with KLF2-induced actin shear fibers, providing evidence that the KLF2-mediated shear fibers are capable of generating force. These results indicate that the KLF2-induced shear fibers are distinct from stress fibers formed by TNF-α or thrombin. Moreover, the effects of KLF2 on actin stress fiber formation and maturation (Figure 2A) follows a similar time course as the slow accumulation of KLF2 (Figure 1) and precedes the late antiinflammatory effects of KLF2. Because ECs from different vascular beds are inherently different,46 we verified whether KLF2 is also capable of inducing shear fibers in ECs of various origins. As displayed in Figure 5C, ECs from microvascular (HMVECs) and arterial (HAECs) origin that overexpress KLF2 also display typical shear fiber formation.

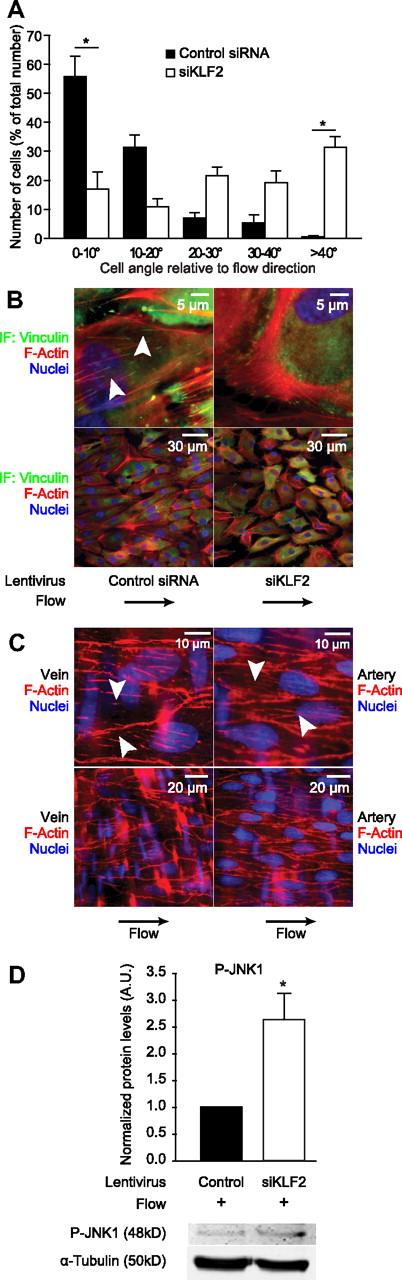

Flow-mediated cell alignment and suppression of JNK are KLF2 dependent

Because KLF2 is normally induced by shear stress, which is known to cause endothelial actin fiber formation,4 we hypothesized that flow-induced KLF2 expression is essential for actin fiber formation caused by shear stress. To test this hypothesis, we subjected HUVECs transduced with a lentiviral siRNA construct designed to silence KLF2 (siKLF2) or with a nonspecific control lentiviral siRNA construct to shear stress for 4 days (19 ± 7 dyn/cm2) by using a parallel-plate flow chamber. Strikingly, we observed that HUVECs exposed to shear stress, which typically elongate and align in the direction of the flow, do not align properly in the flow direction in the absence of KLF2 (siKLF2; Figure 6A-B), indicating that KLF2 is essential for EC alignment to flow. Quantitatively, ECs exposed to flow and control siRNA align in the flow direction, with approximately 90% of the cells lying within an angle of 20° compared with the flow direction, whereas ECs exposed to flow in the absence of KLF2 are positioned in a random angle compared with the flow direction as shown by the even distribution across all measured angle quintiles (Figure 6A). Immunofluorescence microscopy revealed that flow-induced actin fiber formation is highly similar to that induced by KLF2 overexpression in the absence of flow, and indeed silencing of KLF2 completely abrogated the flow-induced formation of these fibers (Figure 6B). The shear fibers that are formed by overexpression of KLF2 or shear stress stimulation in vitro are also highly similar to actin fibers observed in endothelium in situ in intact vessels, with fibers spanning relatively short distances from FA to FA along the basal side of the cell (Figure 6C; supplemental Figure 3).33,47

KLF2 is essential for shear fiber formation, cell alignment, and inhibition of JNK signaling in vitro, and these shear fibers are very similar in endothelium in vivo. (A) HUVECs transduced with either control siRNA lentivirus (filled bars) or KLF2-silencing lentivirus (open bars) were subjected to pulsatile shear stress and fixed. Differential interference contrast microscopy was performed, and approximately 100 cells per condition in 3 independent experiments were analyzed. Cell angle compared with the direction of the flow was measured and visualized in a bar graph. Differences in cell angles in the absence of KLF2 are not significant. (B) HUVECs were treated as in panel A, and immunofluorescence microscopy was performed as for Figure 5B. These images were acquired by merging the green channel (vinculin), the red channel (F-actin), which was acquired at 1 μm higher magnification than the green channel, and the blue channel (nuclei), which was taken at 4 μm higher magnification than the red channel. The flow direction was from left to right. The arrowheads indicate short basal actin filaments similar to those observed after KLF2 overexpression. (C) Intact rat renal arteries and saphenous veins were stained with phalloidin-TRITC (F-Actin, red) and Hoechst 33342 (Nuclei, blue) in situ and visualized by the use of immunofluorescence microscopy and computational deconvolution. The arrowheads show short basal actin filaments, similar to those observed after KLF2 overexpression. (D) Western blot analysis of P-JNK1 in HUVECs treated as in panels A and B. α-Tubulin was used as a loading control. Quantifications are shown for 4 independent experiments. *P < .05.

KLF2 is essential for shear fiber formation, cell alignment, and inhibition of JNK signaling in vitro, and these shear fibers are very similar in endothelium in vivo. (A) HUVECs transduced with either control siRNA lentivirus (filled bars) or KLF2-silencing lentivirus (open bars) were subjected to pulsatile shear stress and fixed. Differential interference contrast microscopy was performed, and approximately 100 cells per condition in 3 independent experiments were analyzed. Cell angle compared with the direction of the flow was measured and visualized in a bar graph. Differences in cell angles in the absence of KLF2 are not significant. (B) HUVECs were treated as in panel A, and immunofluorescence microscopy was performed as for Figure 5B. These images were acquired by merging the green channel (vinculin), the red channel (F-actin), which was acquired at 1 μm higher magnification than the green channel, and the blue channel (nuclei), which was taken at 4 μm higher magnification than the red channel. The flow direction was from left to right. The arrowheads indicate short basal actin filaments similar to those observed after KLF2 overexpression. (C) Intact rat renal arteries and saphenous veins were stained with phalloidin-TRITC (F-Actin, red) and Hoechst 33342 (Nuclei, blue) in situ and visualized by the use of immunofluorescence microscopy and computational deconvolution. The arrowheads show short basal actin filaments, similar to those observed after KLF2 overexpression. (D) Western blot analysis of P-JNK1 in HUVECs treated as in panels A and B. α-Tubulin was used as a loading control. Quantifications are shown for 4 independent experiments. *P < .05.

To identify whether KLF2 would also be indispensible for the shear stress–mediated inhibition of JNK signaling, we subjected HUVECs that were transduced with siKLF2 lentivirus or control lentivirus to shear stress. Analysis of P-JNK levels by Western blot revealed a 2.5-fold induction of P-JNK levels in sheared endothelium in the absence of KLF2 (Figure 6D), indicating a prominent role for KLF2 in repression of JNK signaling. Together, these results signify that KLF2 is essential for shear fiber formation and concomitant cell alignment and inhibition of JNK signaling in vitro and that these shear fibers are present in endothelium in vivo.

Discussion

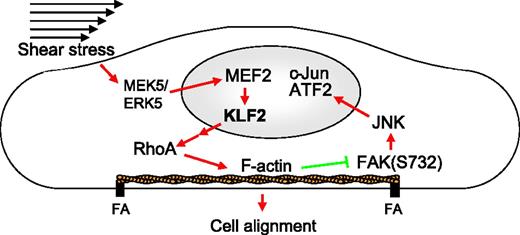

The shear stress–induced transcription factor KLF2 inhibits the proinflammatory activation of ECs. By using array-based phosphoproteome profiling, we now show the concerted effects of KLF2 on the endothelial kinome. We demonstrate that KLF2 attenuates MAPK-mediated posttranslational activation of the AP-1 components c-Jun and ATF2 in an actin cytoskeleton–dependent manner and that antiinflammatory gene expression is displayed only after KLF2-mediated changes in cytoskeleton architecture. Moreover, shear stress–mediated actin cytoskeleton remodeling, which we show to be dependent on KLF2, is very similar, both in vitro and in vivo, resulting in short, thick, basally located actin filaments that run from FA to FA. These KLF2-induced actin fibers, coined shear fibers, are formed independent of Rho kinase and are distinct from the classical Rho kinase–dependent contractile stress fibers, even though these shear fibers contain P-MLC. These results provide an integrated molecular mechanism for the complex indirect effects of KLF2 on the EC transcriptome (Figure 7).10,13

Schematic representation of the proposed mechanism by which KLF2 inhibits JNK signaling and induces cell alignment through the actin cytoskeleton. Shear stress activates the MEK5/ERK5/MEF2 MAPK pathway that transcriptionally induces KLF2, which indirectly activates RhoA, which causes the formation of actin shear fibers. These fibers are both essential for the alignment in the direction of the flow and for inhibition of the FAK-JNK-c-Jun/ATF2 signaling pathway. Red arrows indicate activation; green blunted arrows indicate inhibition.

Schematic representation of the proposed mechanism by which KLF2 inhibits JNK signaling and induces cell alignment through the actin cytoskeleton. Shear stress activates the MEK5/ERK5/MEF2 MAPK pathway that transcriptionally induces KLF2, which indirectly activates RhoA, which causes the formation of actin shear fibers. These fibers are both essential for the alignment in the direction of the flow and for inhibition of the FAK-JNK-c-Jun/ATF2 signaling pathway. Red arrows indicate activation; green blunted arrows indicate inhibition.

The alignment and actin fiber rearrangement of ECs in response to shear flow both in vitro and in vivo is well established.47 Activating stimuli like inflammatory cytokines and thrombin also are known to generate actin fibers, but these so-called stress fibers are transient in nature, mostly consist of thin apically located actin filaments, and result in pathological cell contraction in vitro and edema in vivo.33 Here, we show that KLF2 is essential for cell alignment in the direction of flow via formation of a distinct basolateral, FA-anchored, thick actin shear fiber network, which is quite distinct from classical stress fibers. Although KLF2 increases the activity of RhoA, these KLF2-induced shear fibers are formed independent of Rho kinase, indicating a possible role for other targets of RhoA, like protein kinase N or mammalian diaphanous.48 The specific colocalization of P-MLC with KLF2-induced shear fibers suggests that these fibers are capable of force generation to facilitate cell alignment in the direction of the flow. Furthermore, these fibers and forces could be essential for firm attachment of EC to withstand the mechanical forces, an issue to be addressed in future.

Surprisingly, no gross changes in the MAPK network upstream of AP-1 could be detected (supplemental Table 2). Rather, a widespread effect of KLF2 on actin cytoskeleton–related proteins and kinases was found. We now show that indeed the KLF2-modulated actin cytoskeleton is responsible for the suppression of MAPK signaling, with all isoforms of JNK being affected (Figure 3B). Total P-JNK was not significantly regulated in our kinome screen, but its nuclear level was significantly down-regulated by KLF2, as shown by both Western blotting and immunofluorescence analysis. This prominent effect on nuclear localization of P-JNK nicely complements the inhibitory effects of KLF2 on nuclear localization of c-Jun and ATF2 (Figure 3). Effects of cytochalasin D and time-course analysis showed that suppression JNK signaling by KLF2 occurs only after full maturation of the actin cytoskeleton (Figures 1A and 2A). This finding is consistent with the known effects of actin on the localization of P-JNK, which in its turn raises nuclear c-Jun levels, which are essential for preventing nuclear export of ATF2.49

JNK has long been known as a proinflammatory mediator in many cell types involved in atherosclerosis50 and insulin resistance.51 More recently, JNK was shown to be the central mediator of the inflammatory and atherogenic effects of advanced glycation end products in ECs.52 Our finding that KLF2 uses the actin cytoskeleton to indirectly inhibit JNK signaling and that KLF2 is essential for this process under shear stress stimulation strongly suggests that the KLF2-mediated regulation of the actin cytoskeleton forms an essential part of the anti-inflammatory and antiatherosclerotic effects of shear stress. Shear stress induces remodeling of the actin cytoskeleton and the ECs align in the direction of the flow within 6 hours, and the typical shear-induced actin fibers become visible approximately 24 hours after shear exposure. Thus, KLF2 effects are evident only after prolonged overexpression, correlating with direct downstream target regulation as earliest events (Figure 1) and actin fiber formation and inhibition of JNK signaling as delayed effects (Figures 3–4). In contrast, short-term shear stress exposure (for < 6 hours) or turbulent shear stress are known to activate JNK signaling.53 Although KLF2 mRNA expression is induced in this short time frame, its downstream targets like eNOS and TM (which are indicative of KLF2 protein function) are not induced immediately.34 The role of the actin cytoskeleton in the development of atherosclerosis, typically initiated at sites characterized by absence of laminar shear stress and KLF2,9 recently has been shown directly. Romeo et al54 investigated the role of profilin-1, an essential protein that dynamically regulates actin polymerization, proving that its diminished expression prevented proatherogenic MAPK signaling in ECs and suppressed in vivo atherosclerosis in a mouse model. That study also showed that ATF2 activation was impaired in (atheroprotected) profilin-1+/− mice, which is in accordance with previous data30 and the data presented here that KLF2 inhibits activation of ATF2 in an actin-dependent manner.

In conclusion, the current comprehensive analysis of KLF2 effects on endothelial actin cytoskeleton and MAPK signaling provides mechanistic insights into the suppressive effects of KLF2 on MAPK signaling. The dependency on KLF2 of the formation of distinct actin shear fibers and cell alignment to flow further corroborates the critical role for KLF2 in EC homeostasis. A future, more detailed knowledge of this integrated signaling network might supply specific points of intervention that could mimic the protective effects of shear stress on endothelial function to prevent vascular disease.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Netherlands Heart Foundation grants NHS93.007 and 2008B105 (to A.J.G.H.) and 2003T032 (to G.P.v.N.A.); the NWO-Genomics grant 050-110-1014 (to A.J.G.H.) from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research, The Hague, the Netherlands; and the European Vascular Genomics Network (grant LSHM-CT-2003-503254) from the European Union.

Authorship

Contribution: R.A.B., G.P.v.N.A., and A.J.G.H. designed research; R.A.B., T.A.L., R.D.F., J.O.F., J.M.C.B., and G.P.v.N.A. performed research; R.A.B., T.A.L., R.D.F., J.O.F., J.M.C.B., O.L.V., G.P.v.N.A., and A.J.G.H. analyzed data; and R.A.B. and A.J.G.H. wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation for Dr Boon is the Institute for Cardiovascular Regeneration, Center for Molecular Medicine, Goethe University, Frankfurt, Germany.

Correspondence: Prof Dr Anton J. G. Horrevoets, Department of Molecular Cell Biology and Immunology, VU University Medical Center, van der Boechorststraat 7, 1081 BT Amsterdam, The Netherlands; e-mail: aj.horrevoets@vumc.nl.

References

Author notes

R.A.B. and T.A.L. contributed equally to this work.

![Figure 5. KLF2 induces distinct actin filament formation in a Rho-kinase–independent manner. (A) Mock-transduced (left) and KLF2-transduced (right) HUVECs were fixed, and immunofluorescence microscopy was performed. Visualized in blue are nuclei (stained with Hoechst 33342), in red F-actin (phalloidin-tetramethyl rhodamine iso-thiocyanate [TRITC]), and in green focal adhesions (vinculin stained with Alexa647). The top images were taken at high-power magnification focused on the basal side of the cell, whereas the middle images were taken at approximately 4 μm higher magnification. The bottom images were also taken with focus on the basal side of the cell. Arrowheads indicate typical actin fibers for the given condition. (B) Mock- or KLF2-transduced HUVECs were stimulated for 24 hours with TNF-α (10 ng/mL, top left), Thrombin (1 U/mL, middle left), Y27632 (10μM, top right), or left unstimulated (bottom). Then, cells were fixed, and immunofluorescence microscopy was performed. Visualized in green are focal adhesions (vinculin), in red actin filaments (phalloidin-TRITC), and in blue nuclei (stained with Hoechst 33342; top 4 images) or P-MLC (bottom 2 images). (C) Mock- (left) and KLF2-transduced (right) HMVECs and HAECs were fixed, and immunofluorescence microscopy was performed. Visualized in blue are nuclei (stained with Hoechst 33342), in red F-actin (phalloidin-TRITC), and in green focal adhesions (vinculin stained with Alexa647).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/115/12/10.1182_blood-2009-06-228726/5/m_zh89990948940005.jpeg?Expires=1769907269&Signature=bmGa6OM0JrwfAklSpHbiHKUddblLTFm6T6YLtCJ7GhRzZNTvO7~bwv6wUhoTilnVIQ4bGi4HDdB3clBLt0uf41GnuuCnAPI3USvZfctZKCRYFUdJN~EY3dQhH6-ThBNnQaNPFHQhJBvoqWTbaPRLYvMOtaHQ-CIzi030wc~jf0dxrMXl1iOdMdXGDqB~v1YWg1rtMf7rxQfJOs5WhbB5jp2cLIzb983T0GRH2cj97DWRtd1hJdibu0d4IjfWBqgrKmFGjIy~7B10Bt5th4zC0jjlLKUZ5Kijamt8vS4Y23BtKw4QLMPnfcZLcJt-orb50nRHJ790OFYPC~khzdzLTQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)